Abstract

Background

California Senate Bill 41 (SB41), effective January 2012, is an HIV prevention measure designed to expand syringe access among injection drug users (IDUs) by allowing pharmacists to sell up to 30 syringes without a prescription.

Objective

We assessed SB41 implementation in two inland California counties where prevalence of injection drug use is among the highest in the nation.

Design

Syringe purchase trial.

Setting

Fresno and Kern counties, California.

Participants

All retail pharmacies (N=248).

Main outcome measure

Successful or unsuccessful syringe purchase attempt.

Results

Only 52 (21.0%) syringe purchase attempts were successful. The proportion of successful attempts did not vary by county or by data collector ethnicity. The most common reasons for unsuccessful syringe purchase attempts were prescription requirements (45.7%), the requested syringe size was not available (10.7%), and the pharmacy did not sell syringes (9.7%). In addition, some syringe purchase attempts (4.1%) were unsuccessful because the data collector was asked to purchase more syringes than allowed by law. Although 80% and 78% of Fresno and Kern residents, respectively, live within a 5-minute drive of a retail pharmacy, less than half live within a 5-minute drive of a pharmacy that sold syringes.

Conclusion

SB41 has not resulted in broad pharmacy-based syringe access in California's inland counties, where a disproportionate number of HIV/AIDS cases are associated with injection drug use. Additional steps by legislative bodies, regulatory agencies, and professional organizations are needed to actively engage pharmacies in expanding nonprescription syringe sales to reduce HIV transmission among IDUs.

Keywords: injection drug use, HIV, syringe access, pharmacies, California

INTRODUCTION

A substantial number of HIV cases in the United States are attributed to injection drug use. In 2011, 11% of individuals newly diagnosed with HIV reported injection drug use[1] and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate there are 244,000 people living in the U.S. whose HIV infection can be attributed to drug injection.[2] Blood borne infections like HIV and Hepatitis C (HCV) are transmitted when shared injection equipment is contaminated by an infected individual. For this reason, federal public health officials recommend injection drug users (IDUs) use a new syringe every time they inject.[3]

In some parts of the U.S. access to sterile syringes is limited for those without a prescription. One source of nonprescription syringes is syringe exchange programs (SEPs). These programs distribute sterile syringes and collect used syringes for proper disposal. As of 2011, there were approximately 197 SEPs operating in the U.S. Many operate on limited schedules and provide services within limited geographic areas[4] due to inadequate funding and/or legal restrictions; as a result, U.S. SEPs distribute an average of only 22 syringes per IDU per year[5]– not nearly enough to provide a new syringe for every injection.

A second source of nonprescription syringes is retail pharmacies. Many states have laws allowing nonprescription syringe sales. Research shows these laws can increase pharmacy-based syringe purchase among IDUs and decrease syringe sharing.[6, 7] However, barriers to purchasing syringes persist even where nonprescription sales are legal. Studies using purchase attempts to establish an objective measure of syringe access in states where nonprescription sales are legal document sales refusal rates of 23-79%.[8-13] Lack of knowledge regarding prevailing syringe sales laws, concerns regarding theft and store security, negative attitudes toward drug use and drug users, and concerns that distributing syringes increases drug use are some reasons why pharmacies that can legally sell nonprescription syringes refrain from doing so. [14-20]

In California, 6% of cumulative HIV cases and 10% of cumulative AIDS cases are attributed to injection drug use[21] and approximately 750,000 people are living with HCV.[22] In an effort to reduce HIV and HCV transmission, California passed the Disease Prevention Demonstration Project (DPDP) (Senate Bill (SB) 1159) in 2004. The DPDP established a two-step “opt in” process whereby local health jurisdictions (LHJ) could authorize the program and then pharmacies in those LHJs could register to participate. Registered pharmacies could sell ≤10 syringes at any one time to a person ≥18 years of age without a prescription. The law required that sales be accompanied by written or verbal counseling on drug treatment, HIV/HCV testing and treatment, and safe syringe disposal. It also decriminalized possession of ≤10 syringes obtained from an authorized source.

By 2007, only 17 of California's 61 LHJs had authorized the DPDP and within those LHJs only 18% of pharmacies registered to participate. Among LHJs that did not authorize the program, 31% cited pharmacy disinterest and 26% cited law enforcement opposition as barriers to authorization.[23] Even among participating LHJs, 24% cited “enlisting pharmacy participation” among their greatest implementation challenges. There were also substantial differences in program participation across LHJs; for example, 81% of pharmacies in San Francisco reported nonprescription syringes sales compared to only 28% in Los Angeles.[24] Three years later, purchase trials found that 63% of DPDP pharmacies in San Francisco sold nonprescription syringes compared to only 21% in Los Angeles.[8] Although more IDUs in DPDP-authorized jurisdictions cited pharmacies as a sterile syringe source after program implementation than before (16% vs. 5%),[25] greater access to sterile syringes could further reduce HIV and HCV transmission in California.

On January 1, 2012, the DPDP was superseded by Senate Bill 41 (SB41), which was designed to expand nonprescription syringe sales further by eliminating requirements for LHJ authorization and pharmacy registration and raising the 10-syringe sales cap. Specifically, SB41 allows all licensed pharmacists in California to sell ≤30 syringes to individuals ≥18 years of age and decriminalizes the possession of ≤30 syringes obtained from an authorized source. Pharmacies are still required to provide information on drug treatment, HIV/HCV, and safe disposal. Notably, nonprescription syringe sales remain voluntary; the law allows, but does not require, pharmacies to sell nonprescription syringes to adult customers.

In this study, we examine SB41 implementation in Fresno and Kern counties, two predominantly rural counties in California's Central Valley. In a study of 96 U.S. metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), the Fresno and Kern MSAs ranked second (2.95%) and fourth (2.40%), respectively, in prevalence of injection drug use.[26] Injection drug use accounts for 22% of cumulative AIDS cases (48% of all female cases) in Fresno[27] and 26% of cumulative HIV/AIDS (32% of all female cases) in Kern.[28] In contrast, only 9% of cumulative HIV/AIDS cases in California are attributed to injection drug use.[21] There is only one SEP in Fresno and Kern counties, which operates limited schedule (2 hours per week) in downtown Fresno, so pharmacy-based syringe access is critical to reduce infections in this area. Yet neither county participated in the DPDP and the extent to which local pharmacies are selling nonprescription syringes under SB41 is unknown.

OBJECTIVE

To assess SB41 implementation with an objective measure of pharmacy-based, nonprescription syringe sales in Fresno and Kern counties, two central California counties that have high rates of injection drug use and limited access to SEPs.

METHODS

Study Design

The study design was a syringe purchase trial that included all retail pharmacies in Fresno and Kern counties.

Retail Pharmacy Identification

We used the California Board of Pharmacy's web-based license verification search (http://www.pharmacy.ca.gov/online/verify_lic.shtml) to generate a list of all pharmacies in Fresno and Kern counties. We eliminated pharmacies without current licenses and pharmacies that did not sell to the general public, as non-retail pharmacies would be inaccessible to most IDUs. In cases where eligibility could not be determined we called the pharmacy to clarify the nature of their operations.

The initial list of pharmacies for data collection included 250 pharmacies. During the course of data collection, we found that two pharmacies had shut down and three were misidentified as retail pharmacies. Following completion of data collection at 245 pharmacies, we generated an updated registration list to identify any pharmacies that were newly licensed and completed data collection at three new pharmacies. Overall, we made purchase attempts at each of the 248 retail pharmacies in Fresno (n=135) and Kern (n=113).

Data Collection – Syringe Purchase Trial

Four data collectors were trained to conduct syringe purchases according to a detailed protocol adapted from the investigators’ prior studies.[29, 30] To examine differences in purchasing success by gender and ethnicity, data collectors were selected to reflect the demographic composition of Fresno and Kern counties (i.e., one Latino male, one Latina female, one Caucasian male, and one Caucasian female). Data collectors wore neutral casual attire, excluding clothing items with rips, tears, logos, or printed messages. Data collectors were prohibited from impersonating or otherwise implying that they were an IDU or diabetic. Each data collector attempted to purchase syringes at an equal number of randomly-assigned pharmacies between April 2013 and July 2013.

For each purchase attempt the data collector approached the pharmacy counter and stated “I’d like to buy a syringe.” Subsequent engagement with pharmacy staff was governed by the study protocol. If asked by pharmacy staff, the data collectors stated truthfully that they were at least 18 years old, provided their driver's license, and/or signed a log book. If asked if they were diabetic they stated truthfully that they were not. If asked what type of syringe they wanted, they requested a 0.5cc, 28-gauge disposable syringe - the syringe most commonly requested by Fresno SEP clients. The protocol also allowed purchase of a single 0.5 cc or 1.0 cc syringe (gauges 27-29) or a 10-pack of these eligible sizes if syringes were not sold individually. If asked what the syringe was for the data collector responded that it was “for personal reasons”; if pressed for more information, they stated only that “I’d just like to buy the syringe(s).” Because SB41 requires that nonprescription syringes be purchased from an authorized source and individuals who carry these syringes have been asked by police to furnish evidence that they come from such a source, data collectors were required to obtain a receipt in order to complete any syringe purchase.

Once a purchase attempt was completed, the data collector left the pharmacy and immediately recorded information about the purchase attempt using a web-based data collection form programmed using PenDragon™ Software[31] on a Google Nexus 7 electronic tablet. At the end of each day, the tablets were synced wirelessly to a centralized server and the data were stored in a Microsoft Access database.

Outcome Variable

Syringe purchase attempt result (successful or unsuccessful) was our binary outcome variable.

Independent Variables

For each purchase attempt the data collector recorded information about the pharmacy (e.g. how many other customers in the store), the staff (e.g., number/type of individuals who waited on him/her), and the syringe purchase attempt (e.g., any requirements imposed on the purchase). For successful purchases the type and number of syringes purchased, the cost, and whether the pharmacy provided him/her with the information required under SB41 (i.e., information on drug treatment, HIV/HCV, syringe disposal) was recorded. For the remaining attempts, data collectors recorded the reason(s) why the syringe could not be purchased.

Data Analysis – Syringe Purchase Trial

Descriptive statistics were used to compare successful and unsuccessful syringe purchase attempts in each county. We identified factors associated with successful syringe purchases in each county using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables and Pearson's chi-square test for categorical variables.

Data Analysis – Geographic Accessibility

Given the rural nature of Fresno and Kern counties we also characterized geographic accessibility to pharmacies that sell nonprescription syringes using driving time estimates. We geocoded and mapped all pharmacies using ArcMap 10.1[32] and categorized each by purchase trial outcome. Within each 2010 US Census block group, we calculated the total number of pharmacies overall and by outcome. Because the geographic landscape influences the distribution of both people and services, neither is evenly distributed across a Census block group. Therefore, to represent population locations more accurately we calculated population-weighted block group centroids using block-level population data from the 2010 Census rather than using geographic block group centroids.[33] Using the Google Maps API™ and a custom-written R code,[34] we calculated the driving time in minutes between each population-weighted block group centroid and each pharmacy. For each block group we then calculated 1) the number of pharmacies within a 5-, 15-, and 30-minute drive of the population-weighted block group centroid, and 2) the number of pharmacies within a 5-, 15-, and 30-minute drive of the population-weighted block group centroid where syringes were successfully purchased.

Finally, we calculated the proportion of Fresno and Kern County residents within a 5-, 15-, and 30-minute drive of a retail pharmacy and of a retail pharmacy where syringes were purchased during the purchase trial. Because the population-weighted block group centroid represents the “average” residential location of those living in that block group, we treated this measure of drive-time accessibility as a constant across those residing in that block group. Using block group population data from the 2010 U.S. Census, we calculated the proportion of Fresno and Kern County residents within a 5-, 15-, and 30-minute drive of 1) at least one pharmacy, and 2) at least one pharmacy that sold syringes in the purchase trial.

Human Subjects

The study was approved by the Pacific Institute of Research and Evaluation's Institutional Review Board (IRB). The IRB granted a waiver of consent for pharmacy personnel on the grounds that the protocol met the requirements of 45 CFR 46.116(d): the research was determined to be of minimal risk to the participants (e.g., involvement was limited to normal sales activities, no personally identifiable data were collected), the waiver would not adversely affect the subjects’ rights or welfare, and the research could not practicably be carried out without the waiver.

RESULTS

Syringe Purchase Trial

Overall, 52 (21.0%) purchase attempts were successful. There was no difference in the proportion of successful purchases across counties (20.7% in Fresno and 21.2% in Kern, P=.924). A majority of successful purchases (90.4%) were for 10-packs and the median cost per 10-pack in both counties was $3.19 (maximum price=$10.00). The median cost for syringes sold individually was $1.00 (maximum price=$2.95). Only four of the 52 pharmacies that sold syringes provided the prevention and referral information required by SB41; all four of these pharmacies were in Kern county and each provided the data collector with a “Patient Information Sheet” available online from the California Department of Public Health.[35]

Data collectors were frequently asked for a prescription (21.4%). They were also asked what the syringe was for (30.2%), whether they were diabetic and/or had proof of diabetes (19.8%), and whether they were a customer on file with the pharmacy (5.2%). In 18 (7.3%) attempts the data collector was asked for personally identifiable information including his/her name (2.8%), phone number or address (3.6%), and/or his/her signature in a log book (5.2%).In addition, 4.4% were asked to show ID and 2.8% had information from their ID recorded. In 10.9% of purchase attempts the data collector was told the minimum purchase quantity was 100 syringes.Table 1 shows correlates of successful purchases in each county. There were no statistically significant differences in outcome by data collector ethnicity. The only difference by county was that significantly more of the successful purchases in Kern County were made by male data collectors (70.8% vs. 29.2%, P=.031). In both counties successful purchases were more likely in stores with over 10 customers present at the time of the purchase attempt.

Table 1.

Factors associated with successful syringe purchase attempts, Fresno and Kern counties

| Fresno County (n=135) | Kern County (n=113) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Successful | Unsuccessful | P-value | Successful | Unsuccessful | P-value | |

| Data collector characteristics | ||||||

| Latino male | 8 (28.6) | 28 (26.2) | .848 | 8 (33.3) | 21 (23.6) | 0.175 |

| Caucasian male | 8 (28.6) | 25 (23.4) | 9 (37.5) | 20 (22.5) | ||

| Latino female | 7 (25.0) | 27 (25.2) | 4 (16.7) | 22 (24.7) | ||

| Caucasian female | 5 (17.9) | 27 (25.2) | 3 (12.5) | 26 (29.2) | ||

| Data collector sex | ||||||

| Male | 16 (57.1) | 53 (49.5) | .473 | 17 (70.8) | 41 (46.1) | .031 |

| Female | 12 (42.9) | 54 (50.5) | 7 (29.2) | 48 (53.9) | ||

| Data collector ethnicity | ||||||

| Latino | 15 (53.6) | 55 (51.4) | .838 | 12 (50.0) | 43 (48.3) | .883 |

| Caucasian | 13 (46.4) | 52 (48.6) | 12 (50.0) | 46 (51.7) | ||

| Clerk 1 sex | ||||||

| Male | 9 (32.1) | 31 (29.0) | .744 | 4 (16.7) | 12 (13.5) | .691 |

| Female | 19 (67.9) | 76 (71.0) | 20 (83.3) | 77 (86.5) | ||

| Clerk 1 was a pharmacist | ||||||

| Yes | 1 (3.6) | 11 (10.3) | .084 | 1 (4.2) | 11 (12.4) | .109 |

| No | 25 (89.3) | 73 (68.2) | 22 (91.7) | 63 (70.8) | ||

| Not sure | 2 (7.1) | 23 (21.5) | 1 (4.2) | 15 (16.9) | ||

| Clerk 2 sex (n=77) | ||||||

| Male | 4 (80.0) | 14 (45.2) | .148 | 3 (50.0) | 21 (60.0) | .646 |

| Female | 1 (20.0) | 17 (54.8) | 3 (50.0) | 14 (40.0) | ||

| Clerk 2 was a pharmacist (n=77) | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (40.0) | 22 (71.0) | .279 | 4 (66.7) | 24 (68.6) | .929 |

| No | 2 (40.0) | 4 (12.9) | 1 (16.7) | 7 (20.0) | ||

| Not sure | 1 (20.0) | 5 (16.1) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (11.4) | ||

| Median number of customers within 10 feet (IQR) | 1 (1-3) | 1 (0-2) | .148 | 1 (1-4) | 1 (0-2) | .056 |

| Total number of customers in store | ||||||

| <5 | 2 (7.1) | 36 (33.6) | .020 | 3 (12.5) | 40 (44.9) | <.001 |

| 5-10 | 9 (32.1) | 27 (25.2) | 3 (12.5) | 20 (22.5) | ||

| >10 | 17 (60.7) | 44 (41.1) | 18 (75.0) | 29 (32.6) | ||

Table 2 presents reasons for unsuccessful syringe purchases by county. The most common reasons for failed purchase attempts were not having a prescription (45.7%), not having the syringe size/type requested (10.7%), being told the pharmacy did not sell syringes (9.7%), and the data collector not providing a specific reason for purchase (8.2%). In 31.6% of failed attempts the data collector was asked about their diabetes status. Reasons for refusal did not differ significantly by county except that pharmacies in Kern were more likely to mention diabetes during failed purchase attempts (40.5% in Kern vs. 24.3% in Fresno, P=.015).

Table 2.

Reasons for failed syringe purchase attempts, Fresno and Kern counties*

| Total (N=196) | Fresno County (n=107) | Kern County (n=89) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prescription required | 90 (45.7) | 55 (50.9) | 35 (39.3) | .104 |

| Pharmacy did not have syringe size/type requested | 21 (10.7) | 9 (8.4) | 12 (13.5) | .253 |

| Pharmacy does not sell syringes | 19 (9.7) | 10 (9.4) | 9 (10.1) | .857 |

| Data collector did not provide specific reason for purchase | 16 (8.2) | 10 (9.4) | 6 (6.7) | .507 |

| Minimum purchase requirement (≥100 syringes) | 8 (4.1) | 4 (3.7) | 4 (4.5) | .790 |

| Data collector was not an established customer/information was not on file | 8 (4.1) | 6 (5.6) | 2 (2.3) | .237 |

| Pharmacy reported no syringes in stock | 6 (3.1) | 4 (3.7) | 2 (2.3) | .546 |

| Direct refusal | 5 (2.6) | 2 (1.9) | 3 (3.4) | .507 |

| Data collector could not get receipt | 1 (2.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | .363 |

| Diabetes mentioned during purchase attempt | 62 (31.6) | 26 (24.3) | 36 (40.5) | .015 |

Categories are not mutually exclusive

Geographic Access to Nonprescription Syringes

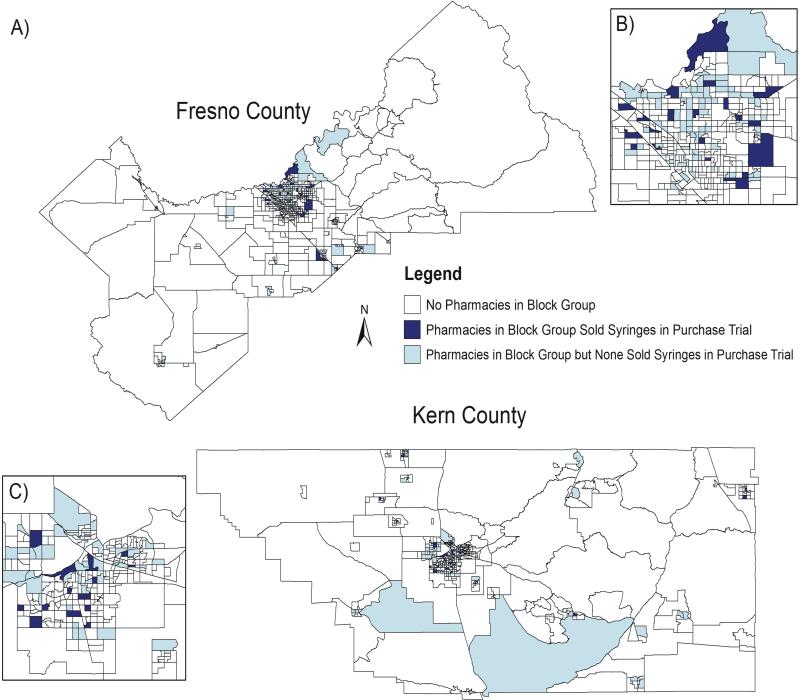

Figure 1 displays Fresno and Kern County block groups where pharmacies were a) absent, b) present but did not sell syringes, and c) present and sold syringes. Figure 1A shows both counties and Figures 1B and 1C display the most urban region of each county (the cities of Fresno and Bakersfield, respectively). Because large portions of both counties are comprised of sparsely populated areas dominated by mountains, desert, and/or large-scale agriculture, there are sizeable geographic areas with no pharmacies present. Most pharmacies, particularly those that sold syringes, were located in the more urban areas of each county.

Figure 1. Geographic distribution of pharmacies in Kern and Fresno counties by block group, 2013.

Block groups without pharmacies are in white, block groups with pharmacies who did not sell syringes in the syringe purchase trial are in light blue and block groups with pharmacies who sold syringes in the syringe purchase trial are in navy blue. In Figure 1A which displays both Fresno and Kern counties, 1 inch = 24 miles. In Figures 1B (Fresno City) and 1C (Bakersfield City), one inch = 7 miles.

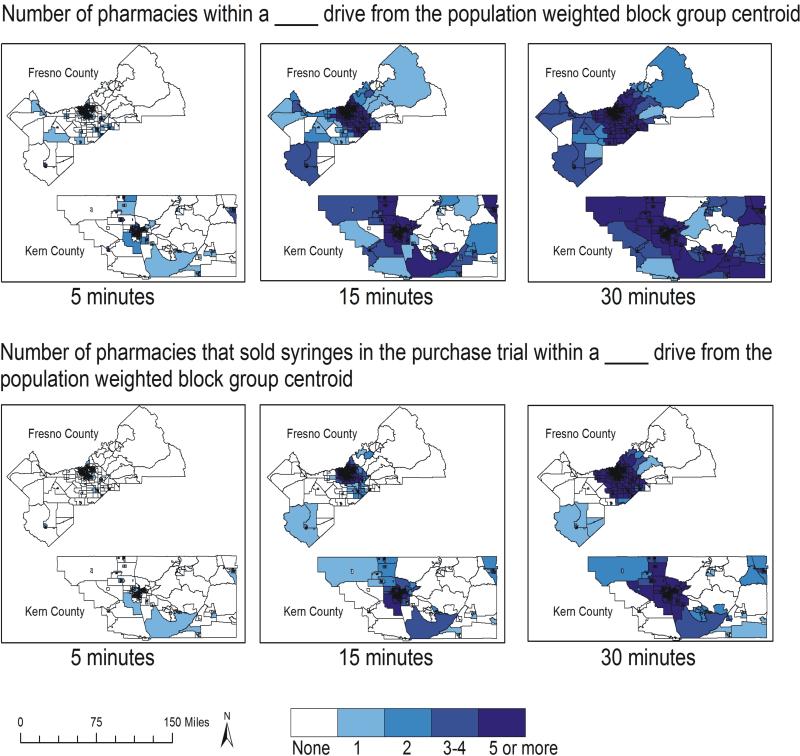

Figure 2 compares accessibility to retail pharmacies overall to those that sold syringes in our purchase trial, based on driving times. The figure shows that pharmacy accessibility increases with driving time and that accessibility of pharmacies that sold syringes in the purchase trial is much more restricted than accessibility of pharmacies overall. Table 3 shows that although 80% of Fresno County residents and 78% of Kern County residents live within a 5-minute drive of a retail pharmacy only half live within a 5-minute drive of a pharmacy that sold syringes. A 15-minute drive increases the proportion of the population with access to at least one syringe-selling pharmacy to more than three quarters in both counties.

Figure 2. Driving accessibility in minutes to pharmacies in Fresno and Kern counties, CA (2013).

The top panel displays driving accessibility to pharmacies in minutes and the lower panel displays driving accessibility in minutes to pharmacies who sold syringes in the purchase trial. Darker shades indicate an increasing number of pharmacies (overall or who sold syringes in the purchase trial, respectively) within a range of driving distances of each population-weighted block group centroid.

Table 3.

Percentage of Kern and Fresno Residents within a 5-, 15-, 30-minute drive to a pharmacy and to a pharmacy where syringes were sold during the purchase trial

| Kern % | Fresno % | |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacy within a 5 minute drive | 78.41 | 79.89 |

| Pharmacy that sold a syringe in the purchase trial within a 5 minute drive | 48.39 | 47.25 |

| Pharmacy within 15 minute drive | 96.42 | 97.85 |

| Pharmacy that sold a syringe in the purchase trial within 15 minute drive | 83.24 | 85.22 |

| Pharmacy within 30 minute drive | 99.59 | 99.59 |

| Pharmacy that sold a syringe in the purchase trial within 30 minute drive | 91.90 | 93.95 |

Our calculations show that if every retail pharmacy sold nonprescription syringes, as allowed by law, the average drive time to the nearest pharmacy-based syringe source would be 5.52 minutes in Fresno and 4.38 minutes in Kern. Based on the results of our purchase trial, the average drive time to the nearest pharmacy that sells nonprescription syringes is about 10 minutes in both Fresno (9.41 minutes) and Kern (10.26 minutes).

DISCUSSION

Despite efforts under SB41 to reduce HIV/HCV transmission by expanding sterile syringe access, nonprescription syringe sales at retail pharmacies in Fresno and Kern counties remain extremely limited. Our study found that only 21% of pharmacies sold nonprescription syringes, a level among the lowest ever documented in a U.S. syringe purchase trial.

Under SB41, any individual ≥18 years old should be able to enter a retail pharmacy and purchase ≥30 syringes without a prescription or any documentation except proof of age. Yet not having a prescription was the most common reason for failed purchase attempts and data collectors were frequently asked about their diabetes status. In addition, even where syringes were successfully purchased data collectors were asked why they wanted the syringe and for other personal information (e.g., name, phone number, address, signature) even though there is no legal or regulatory basis for doing so. Such questions and requirements may serve as a powerful disincentive for IDUs to attempt purchases at pharmacies where nonprescription syringes are sold. It is unclear from our study whether requests for prescriptions and sensitive personal information are attributable to lack of knowledge regarding SB41 or a decision not to participate in nonprescription syringe sales; regardless, we conclude that SB41 is not having the desired effect of providing broad pharmacy-based syringe access in this region where injection drug use is a significant contributor to the HIV epidemic.

Some purchase attempts failed because the pharmacy did not have the requested syringe size/gauge (0.5-1.0cc/27-29 gauge) in stock. Our criteria for type/gauge of the purchase were informed by the activities of Fresno's SEP, which is well-versed in the types of syringes commonly used by IDUs in the area. Stocking the type/gauge of syringes most commonly used by local IDUs is important to effectively reduce HIV/HCV transmission among local IDUs under SB41. The state health department, local SEPs, and other local organizations focused on preventing HIV/HCV transmission among IDUs can provide pharmacies with this information.

Other purchase attempts failed because the data collector was asked to purchase >10 syringes; specifically, six pharmacies required a minimum purchase of 100 syringes. SB41 caps the number of nonprescription syringes that can be purchased at 30; therefore, selling 100 syringes to a customer without a prescription is illegal. It is unclear whether this indicates a lack of knowledge regarding prevailing laws or an effort to thwart nonprescription sales without directly refusing a sale.

Where syringe purchases were successful, only a few pharmacies provided the SB41-requred information on drug treatment, HIV/HCV, and safe syringe disposal. This information is easily accessible to pharmacies via an on-line “Patient Information Sheet” provided by the California Department of Public Health.[35] While provision of this information is required by law, it is also good community health practice. Nonprescription syringe sales present an invaluable opportunity to engage IDUs in conversation and information exchange regarding individual and community health. Linking IDUs to drug treatment can facilitate reductions in and/or cessation of drug use; information about where to receive testing and treatment is critical to “seek, test, and treat” efforts that aim to promote individual health and reduce the community's HIV viral load; and proper syringe disposal is necessary to ensure the health and safety of the surrounding community. Pharmacies that engage in nonprescription syringe sales further their role as community health advocates by providing this information - an opportunity missed by pharmacies that do not sell nonprescription syringes.

Our study found few factors associated with successful syringe purchase outcomes. Pharmacies with more customers present were more likely to sell syringes. This suggests that larger stores, like chain pharmacies and pharmacies situated within mass market retailers, may be more likely to sell syringes but the reasons underlying this association could not be ascertained by our study. Notably, the proportion of successful purchases for Fresno and Kern counties was identical (21%) and there were few differences in the factors associated with successful purchases across the two counties. This suggests that the issues influencing pharmacy participation in nonprescription syringe sales may be the same for both counties and possible even across California's Central Valley, which is relatively homogeneous sociodemographically, politically, and geographically.

Our study is just one of a handful to examine pharmacy-based syringe access in predominantly rural communities.[9, 36, 37] Syringe accessibility is also a function of distance and we found that only half of Fresno and Kern residents live within a 5-minute drive of a pharmacy that sells syringes. On average, the inability to purchase syringes at most pharmacies doubles the driving time required to reach the nearest pharmacy that sells syringes. This presumes that the individual who seeks to purchase a syringe knows a priori which pharmacies sell nonprescription syringes; in reality, they may have to attempt purchases at a number of pharmacies before finding one that will sell.

LIMITATIONS

This study has limitations. First, our data collectors did not impersonate IDUs in their clothing or behaviors. Some studies have found that purchaser appearance is important because pharmacy staff may be less likely to sell syringes to someone they perceive as an IDU;[38-40] therefore, our study may overestimate the likelihood of purchasing a syringe among IDUs. Second, the willingness of our data collectors to provide identifying information during the purchase trial is likely not representative of IDUs, who are engaging in illegal activity and in many cases may not have photo ID. This would also inflate our estimates of nonprescription syringe availability. Third, we did not attempt purchases in bordering counties that may be geographically convenient for Fresno and Kern residents; accordingly, our driving time estimates may overestimate the time required to reach a pharmacy that sells syringes. Fourth, our calculations assume that everyone in the population has access to a motor vehicle. For individuals who do not have access to a car, and for those in the more urban areas of Fresno and Kern County who walk or take public transportation rather than drive, our measures will overestimate nonprescription syringe accessibility. Finally, our driving time estimates apply to the population overall and not specifically to IDUs. As pharmacies are more accessible to residents in some regions of Fresno and Kern counties than others, and IDUs are not equally likely to live in each region, our measures of accessibility may overestimate or underestimate drive times among IDUs depending on their geographic distribution relative to the overall population.

CONCLUSION

Legislative efforts to promote nonprescription syringe sales have not led to broad pharmacy-based syringe access for IDUs in the California's Central Valley, where a disproportionate number of HIV/AIDS are attributable to injection drug use. Our study demonstrates that in California, as in some other states where nonprescription syringe sales are legal but voluntary, legislative changes alone may not be enough to substantially expand syringe for IDUs. Additional efforts by legislative bodies, regulatory agencies, professional organizations, and retail pharmacy chains may also be required to reach the full potential of these legislative initiatives. These efforts might include interventions that promote pharmacists’ understanding of the laws allowing nonprescription syringe sales, the importance of expanding syringe access to HIV/HCV prevention efforts, and types of syringes preferred by local IDUs. Legislation and/or regulations that go beyond voluntary nonprescription syringe sales to require such sales should also be considered.

Article Relevance and Contribution to Literature.

This study examines implementation of California Senate Bill 41 (SB41), which since 2012 has allowed pharmacies to voluntarily sell nonprescription syringes as a means to prevent HIV and Hepatitis C (HCV) transmission among injection drug users (IDUs). We conducted a syringe purchase trial in two inland California counties with a high prevalence of injection drug use and limited access to syringe exchange programs. We found that only 21% of retail pharmacies sold nonprescription syringes – a level among the lowest ever documented in a U.S. syringe purchase trial. Our findings demonstrate low levels of pharmacy participation, which limit the potential for SB41 to expand syringe access in California. This represents a missed opportunity for California pharmacies to play a key role in HIV/HCV prevention. Interventions by professional organizations and retail pharmacy corporations are needed to promote pharmacists’ understanding of SB41 and the importance of expanding syringe access to HIV/HCV prevention efforts. Legislation and/or regulations that go beyond voluntary nonprescription syringe sales to require such sales should also be considered.

Acknowledgement

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA035098). Dr. Rudolph's efforts were funded under a NIDA Mentored Research Scientist Award (DA033879). The authors wish to thank Dallas Blanchard, Dennis Hendrix, Derrik Watson, Robert Aikins, Marco Ayard, Afton Larson, and Sonia Jimenez-Watson for their valuable contributions to this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epidemiology of HIV infection through. 2011 Accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_surveillance_Epi-HIV-infection.pdf.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 US dependent areas—2010. HIV AIDS Surveill Rep. 2012;17(3) [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Public Health Service . HIV prevention bulletin: medical advice for persons who inject illicit drugs. Rockville; MD: May 9, 1997. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Des Jarlais DC, Guardino V, Nugent A, et al. National Survey of Syringe Exchange Programs: Summary of Results. 2011 Accessed at http://www.nasen.org/news/2012/nov/29/2011-beth-israel-survey-results-summary/

- 5.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Ali H, et al. HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: A systematic review of global, regional, and national coverage. Lancet. 2010;375(9719):1014–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cotton-Oldenburg NU, Carr P, DeBoer JM. Impact of pharmacy-based syringe access on injection practices among injection drug users in Minnesota, 1998 to 1999. JAIDS. 2001:27183–92. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200106010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groseclose SL, Weinstein B, Jones TS, et al. Impact of increased legal access to needles and syringes on practices of injecting-drug users and police officers — Connecticut, 1992-1993. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;10(1):82–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lutnick A, Cooper E, Dodson C, et al. Pharmacy Syringe Purchase Test of Nonprescription Syringe Sales in San Francisco and Los Angeles in 2010. J Urban Health. 2013;90(2):276–83. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9713-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Compton WM, Horton JC, Cottler LB, et al. A multistate trial of pharmacy syringe purchase. J Urban Health. 2004;81(4):661–70. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deibert RJ, Goldbaum G, Parker TR, et al. Increased access to pharmacy sales of syringes in Seattle-King County, Washington: Structural and individual-level changes, 1996 versus 2003. Am J Public Health. 2006:96134. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.032698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelstein R, Tiger R, Greenwald R, et al. Pharmacy syringe sale practices during the first year of expanded syringe availability in New York City (2001-2002). J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2002;42(6 Suppl 2):S83–S87. doi: 10.1331/1086-5802.42.0.s83.finkelstein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koester SK, Bush TW, Lewis BA. Limited access to syringes for injection drug users in pharmacies in Denver, Colorado. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2002;42(suppl 2):S88–S91. doi: 10.1331/1086-5802.42.0.s88.koester. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trubatch BN, Fisher DG, Cagle HH, et al. Nonprescription pharmacy sales of needles and syringes. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(10):1639–40. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.10.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blumenthal WJ, Springer KW, Jones TS, et al. Pharmacy student knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about selling syringes to injection drug users. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2002;42(Suppl 2):SS34–39. doi: 10.1331/1086-5802.42.0.s34.blumenthal. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singer M, Baer HA, Scott G, et al. Pharmacy access to syringes among injecting drug users: follow-up findings from Hartford,Connecticut. Public Health Rep. 1998;133(Suppl 1):81–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farley TA, Niccolai LM, Billeter M, et al. Attitudes and practices of pharmacy managers regarding needle sales to injection drug users. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 1999;39(Jan-Feb):23–26. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)30411-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marks RW, Hanrahan M, Williams DH, et al. Encouraging pharmacy sale and safe disposal of syringes in Seattle, Washington. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2002;42(suppl 2):S26–S27. doi: 10.1331/1086-5802.42.0.s26.marks. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright-De Aguero L, Weinstein B, Jones TS, et al. Impact of the change in Connecticut syringe prescription laws on pharmacy sales and pharmacy managers' practices. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;18(Suppl 1):S102–S10. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199802001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taussig J, Junge B, Burris S, et al. Individual and structural influences in shaping pharmacists’ decisions to sell syringes to injection drug users in Atlanta, Georgia. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2002;42(Suppl 2):S40–45. doi: 10.1331/1086-5802.42.0.s40.taussig. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis BA, Koester SK, Bush TW. Pharmacists' attitudes and concerns regarding syringe sales to injection drug users in Denver, Colorado. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2002;42(6 Suppl 2):S46–S51. doi: 10.1331/1086-5802.42.0.s46.lewis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.California Department of Public Health Office of AIDS HIV/AIDS surveillance in California. Accessed at http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/aids/Documents/June_2013_Semi%20Annual%20Report.pdf.

- 22.California Department of Public Health Chronic Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C infections in California: cases newly reported through. 2011 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garfein RS, Stopka TJ, Pavlinac PB, et al. Three years after legalization of nonprescription pharmacy syringe sales in California: Where are we now? J Urban Health. 2010;87(4):576–85. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9463-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper EN, Dodson C, Stopka TJ, et al. Pharmacy participation in non-prescription syringe sales in Los Angeles and San Francisco counties, 2007. J Urban Health. 2010;87(4):543–52. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9483-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stopka TJ, Garfein R, Riley E, et al. SB 1159 Report: An Evaluation of Over-the-Counter Sale of Sterile Syringes in California. Sacramento. CA2010:96. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brady JE, Friedman SR, Cooper HL, et al. Estimating the prevalence of injection drug users in the US and in large US metropolitan areas from 1992 to 2002. J Urban Health. 2008;85(3):323–51. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9248-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.California Department of Public Health Cumulative Reported AIDS February 1, 1983 - December 31, 2013. Accessed at http://www.co.fresno.ca.us/uploadedFiles/Departments/Public_Health/Divisions/CH/content/CD/content/Epidemiology/2013/AIDS%204th%20QTR%202013.pdf.

- 28.Kern County Public Health Services Department . HIV/AIDS service delivery plan. Bakersfield; CA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollini RA, Rosen PC, Gallardo M, et al. Not sold here: limited access to legally available syringes at pharmacies in Tijuana, Mexico. Harm Reduct J. 2011;8(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fedorova EV, Skochilov RV, Heimer R, et al. Access to syringes for HIV prevention for injection drug users in St. Petersburg, Russia: syringe purchase test study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pendragon Software Corporation Pendragon Forms VI, editor. Pendragon Software Corporation; Buffalo Grove, IL: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32.ESRI North America Detailed Streets. Redlands, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang D-H, Goerge R, Mullner R. Comparing GIS-based methods of measuring spatial accessibility to health services. J Med Syst. 2006;30(1):23–32. doi: 10.1007/s10916-006-7400-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delamater PL, Messina JP, Shortridge AM, et al. Measuring geographic access to health care: raster and network-based methods. Int J Health Geogr. 2012;11(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-11-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.California Department of Public Health Materials for Pharmacists and Health Departments – Nonprescription Sale of Syringes. Accessed at http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/aids/Pages/OASAMaterials.aspx.

- 36.Case P, Beckett GA, Jones TS. Access to sterile syringes in Maine: Pharmacy practice after the 1993 repeal of the syringe prescription law. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;18(Suppl 1):S94–S101. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199802001-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reich W, Compton WM, Horton JC, et al. Injection drug users report good access to pharmacy sale of syringes. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2002;42(6 Suppl 2):S68–S72. doi: 10.1331/1086-5802.42.0.s68.reich. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davidson PJ, Lozada R, Rosen PC, et al. Negotiating access: social barriers to purchasing syringes at pharmacies in Tijuana, Mexico. Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23(4):286–94. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaller ND, Yokell MA, Apeakorang N, et al. Reported Experiences During Syringe Purchases in Providence, Rhode Island: Implications for HIV Prevention. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(3):1310–26. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollini RA, Lozada R, Gallardo M, et al. Barriers to pharmacy-based syringe purchase among injection drug users in Tijuana, Mexico: a mixed methods study. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):679–87. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9674-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]