Abstract

Enzyme I (EI), the first component of the bacterial phosphotransfer signal transduction system, undergoes one of the largest substrate-induced interdomain rearrangements documented to date. Here, we characterize the perturbations generated by two small molecules, the natural substrate phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and the inhibitor α-ketoglutarate (αKG), on the structure and dynamics of EI using NMR, small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and biochemical techniques. The results indicate unambiguously that the open-to-closed conformational switch of EI is triggered by complete suppression of micro- to millisecond dynamics within the C-terminal domain of EI. Indeed, we show that a ligand-induced transition from a dynamic to a more rigid conformational state of the C-terminal domain stabilizes the interface between the N- and C-terminal domains observed in the structure of the closed state, thereby promoting the resulting conformational switch and autophosphorylation of EI. The mechanisms described here may be common to several other multidomain proteins and allosteric systems.

Large rigid body reorientations of one structural domain relative to another induced by small molecule binding is a key feature of many biological systems, governing diverse processes such as catalysis, the formation of protein assemblies, cellular locomotion and motor translocation.1–3 Although the structural changes underlying domain reorientations have long been recognized,4 the fundamental forces that trigger and drive large conformational rearrangements remain unknown, with the exception of trivial cases in which ligands bind directly to the interface or hinge point between two domains.

Here we investigate the effect of two small molecule ligands, the substrate phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and the competitive inhibitor α-ketoglutarate (αKG), on the structure and dynamics of E. coli Enzyme I (EI). Autophosphorylation of EI by PEP activates the bacterial phosphotransfer signal transduction system (PTS), a phosphorylation cascade involving multiple bimolecular phosphoryl transfer steps that results in eventual active sugar transport across the cell membrane.5, 6 EI is also competitively inhibited by αKG,7, 8 the carbon substrate for ammonia assimilation. If bacteria are cultured under conditions of nitrogen limitation, EI inhibition by αKG is strong enough to abolish active sugar uptake by the PTS, thereby providing a regulatory link between central carbon and nitrogen metabolisms.7, 8

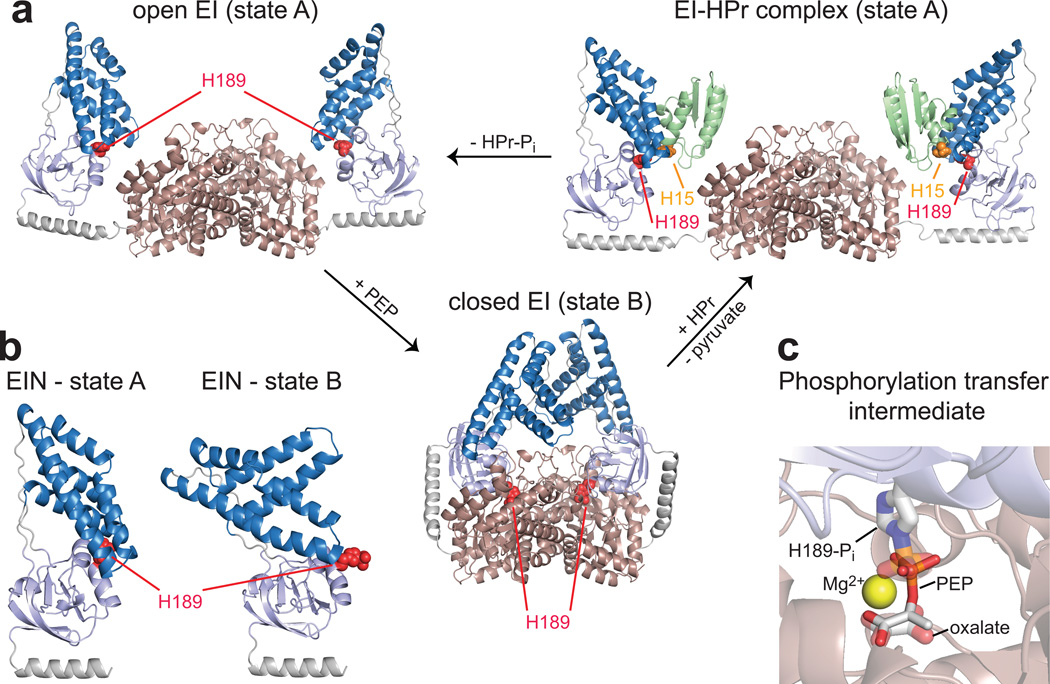

The functional form of EI is a 128-kDa dimer of identical subunits comprising two structurally and functionally distinct domains (Fig. 1a). The N-terminal phosphoryl-transfer domain (EIN, residues 1-249) contains the phosphorylation site (H189) and the binding site for the histidine phosphocarrier protein HPr, located in the α/β and α subdomains, respectively. The C-terminal domain (EIC, residues 261-575) is responsible for dimerization and contains the binding site for PEP. The EIN and EIC domains are connected to one another by a long helical linker. Isolated EIN can transfer a phosphoryl group to HPr but cannot be autophosphorylated by PEP.9 The solution structure of EI in its apo form has been solved by a combination of NMR residual dipolar coupling and X-ray scattering data.10 In the absence of ligands, EI adopts an open conformation (state A) in which the EIN domains of the two monomeric subunits are more than 60 Å apart (Fig. 1a). The holo structure of the enzyme is more elusive and has currently not yet been determined. Addition of PEP to EI results in autophosphorylation of the enzyme at the H189 position and formation of pyruvate as a byproduct of the enzymatic reaction. The X-ray structure, however, of a phosphorylated EI intermediate captured immediately after autophosphorylation by PEP has been solved by crystallizing the protein in the presence of PEP and Mg2+ and quenching the autophosphorylation reaction by addition of the inhibitor oxalate.11 In the phosphorylated intermediate, the enzyme adopts a closed conformation (state B) in which the EIN domains of the two subunits are in direct contact, and the active site H189 is inserted in the PEP binding pocket of the EIC domain (Fig. 1a). The open-to-closed transition involves two coupled, rigid body rotations of the two subdomains of EIN: namely, a ~90° reorientation of the α/β subdomain relative to EIC (Fig. 1a) and a ~70° reorientation of the α subdomain relative to the α/β subdomain (Fig. 1b). Modeling the position of PEP by replacing oxalate and the phosphoryl group indicates that the closed conformation is fully consistent with in-line phosphoryl transfer from PEP bound to the EIC domain to H189 on the α/β subdomain of EIN11 (Fig. 1c). However, it is not clear whether the closed conformation corresponds to the holo form of the enzyme or is only transiently sampled to permit the phosphoryl transfer reaction. Once H189 in the α/β subdomain is phosphorylated, conformational rearrangement rapidly occurs to a structure that resembles the apo form, thereby exposing the phosphoryl group and making it available for in-line phosphoryl transfer to HPr bound to the α subdomain (Fig. 1a).10

Figure 1. EI adopts several conformations during its catalytic cycle.

(a) Experimental structures of full-length E. coli EI.10, 11 The EIC domain is colored pink. The α and α/β subdomains of EIN are colored blue and light blue, respectively. HPr is shown in green. The active site histidines, H189 of EI and H15 of HPr, are shown as red and orange spheres, respectively. (b) Conformations adopted by EIN in the open (state A) and closed (state B) structures. (c) Structural model of PEP bound in the active site of closed EI.8 PEP is shown as solid sticks. The phosphorylated H189 and the oxalate molecule in the X-ray structure of the closed phosphorylated intermediate11 are shown as transparent sticks. The magnesium ion present in the X-ray structure is displayed as a yellow sphere.

Here, using solution NMR and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) we show that binding of PEP to the EIC domain induces a dynamic equilibrium in which both the open and closed forms of EI are populated. Interestingly, we observe that no contacts between PEP and the EIN domain are needed to trigger the open-to-closed transition of EI. Although this finding cannot be explained in terms of the available static structures of EI, we show that a transition from a dynamic to a more rigid EIC structure, induced by PEP-binding, is responsible for the large conformational rearrangement. Our results provide direct evidence for large-scale interdomain rearrangements induced by a change in dynamics within one of the protein domains, further supporting the recently emerging idea of protein flexibility as a general mechanism for transmitting signals between distant sites in macromolecules or macromolecular assemblies.12

Results

Effect of PEP and αKG on the open-to-closed conformational equilibrium of EI

The effect of PEP and αKG on the global structure of EI was assessed by means of backbone (1HN/15N) and side chain (1H/13Cmethyl) chemical shift perturbation mapping and SAXS. Experiments were acquired on the wild-type protein (EIWT) and on mutants of EI in which the active site H189 was replaced by Gln (EIQ) or Ala (EIA). The EIQ and EIA mutants allow the PEP-induced structural perturbations to be probed without interference caused by phosphorylation of H189, and have been extensively employed in structural and biochemical studies of EI.13–16

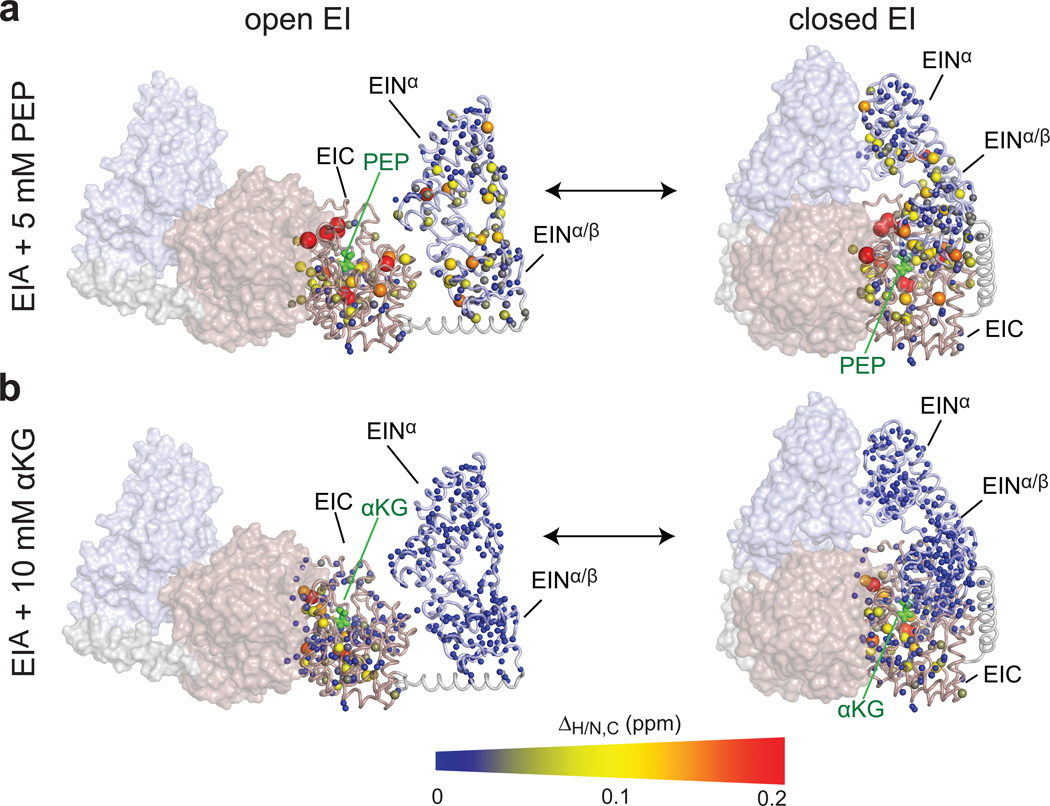

Addition of 5 mM PEP to EIQ and EIA results in substantial changes in the 1H-15N and 1H-13Cmethyl transverse relaxation optimized (TROSY) correlation spectra (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1). As expected, larger chemical shift perturbations (ΔH/N,C) are observed in the EIC domain and involve residues located in the PEP binding site and at the dimer interface (Fig. 2a). These perturbations closely resemble the PEP-induced chemical shift perturbations observed previously for isolated EIC (Supplementary Fig. 2).17 In addition, chemical shift perturbations are also observed in the EIN domain at sites located more than 20 Å away from the PEP binding site in the open EI structure (Fig. 2a). In particular, the largest perturbations on the EIN domain are observed in the linkers connecting the α and α/β subdomains, in the vicinity of the helical linker connecting EIN to EIC, at the interface between the α and α/β subdomains, and at the interfaces between EIN and EIC and between the two EIN subunits in the closed EI structure (Fig. 2a). All these regions are expected to experience chemical shift perturbations upon transition from the open to the closed form of EI. In contrast, addition of 10 mM αKG to EIWT, EIQ or EIA does not result in any significant chemical shift perturbation within the EIN domain (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 1); the only chemical-shift changes observed are located within the EIC domain, and closely resemble the chemical shift perturbations induced by αKG on isolated EIC (Supplementary Fig. 2).8

Figure 2. NMR analysis of the EI-PEP and EI-αKG complexes.

Weighted combined chemical shift perturbations (ΔH/N,C) induced by (a) PEP and (b) αKG on the 1H-15N and 1H-13Cmethyl TROSY correlation spectra of EIA displayed on the structure of EI as spheres with the relationship between size and color of each sphere and chemical shift perturbation depicted by the color bar. ΔH/N,C values are displayed on one subunit of the EI dimer. The second subunit is shown as a transparent surface. The EIN and EIC domains are colored light blue and pink, respectively. PEP and αKG bound to one subunit of EI are shown as green sticks. Plots of of chemical shift perturbations as a function of residue for EIWT, EIQ and EIA are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Overall, the chemical shift perturbation data suggest that only PEP binding to EIC is able to trigger the transition from the open to the closed form of EI, while binding of αKG leaves the overall structure of EI unperturbed in the open state. To test this hypothesis SAXS data were acquired for EIWT, EIQ and EIA in the presence and absence of ligands. SAXS curves are linear time-averaged and ensemble weighted experimental measurements that are highly sensitive to the overall size and shape of a molecule.18, 19 Thus, SAXS is a good reporter of conformational equilibria involving large interdomain rearrangements.

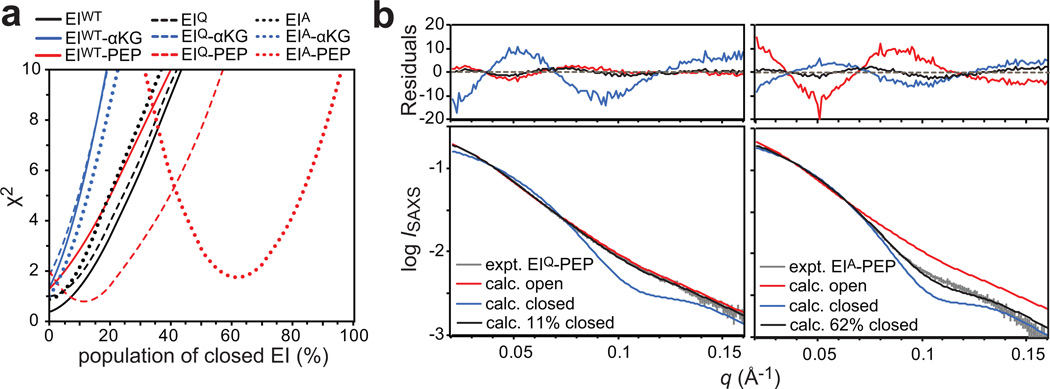

The SAXS data were fit (up to q = 0.16 Å−1) with a helper program distributed with Xplor-NIH20 (see Supplementary Methods) using a grid search (step size = 1%) in which increasing populations of the closed EI conformer were added to the starting system comprising EI in the open configuration. A plot of χ2 versus population of closed state is shown in Fig. 3a. In general, raising the population of the closed EI state results in larger χ2 values for the majority of the scattering curves, indicating that the SAXS data acquired for most of the EI samples are best fit by the open structure of the enzyme. However, exceptions to this trend are observed for the scattering curves obtained for EIQ and EIA in the presence of PEP where the χ2 minimum is reached at closed-state populations of ~11 and ~62% for the EIQ-PEP and the EIA-PEP complexes, respectively (Figs. 3a and b), confirming that only the interaction of PEP with EIC is able to trigger the open-to-closed conformational transition of EI.

Figure 3. SAXS analysis of free and bound EI.

(a) Plots of χ2 obtained from fitting the experimental SAXS curves with a linear combination of open and closed EI structures versus the population of closed EI. Solid, dashed and dotted lines refer to data acquired for EIWT, EIQ and EIA, respectively. Black, blue and red lines refer to the data acquired in the absence of ligands, and in the presence of 20 mM αKG and 20 mM PEP, respectively. (b) Best-fits obtained for EIQ (left panel) and EIA (right panel) in the presence of PEP. The experimental SAXS curve is shown in gray. Curves back-calculated from the open and closed experimental structures of EI are colored in red and blue, respectively. The best-fit curve is shown in black. Residuals, given by , are plotted above each panel.

We note that although the SAXS curves in the absence of ligands are fit very well by the open structure of EI (χ2 ≤ 1), small, systematic deviations between the experimental and calculated SAXS curves are observed for the EIA-PEP complex (Fig. 3b), for which the largest population of closed EI was obtained from the fits (Fig. 3a). This suggests that the crystal structure of the phosphorylated intermediate does not fully describe the solution structure of holo EI. Assessment of the small discrepancy between the structures of closed EI in the crystal and solution states is beyond the scope of the present work and will be the subject of future investigations.

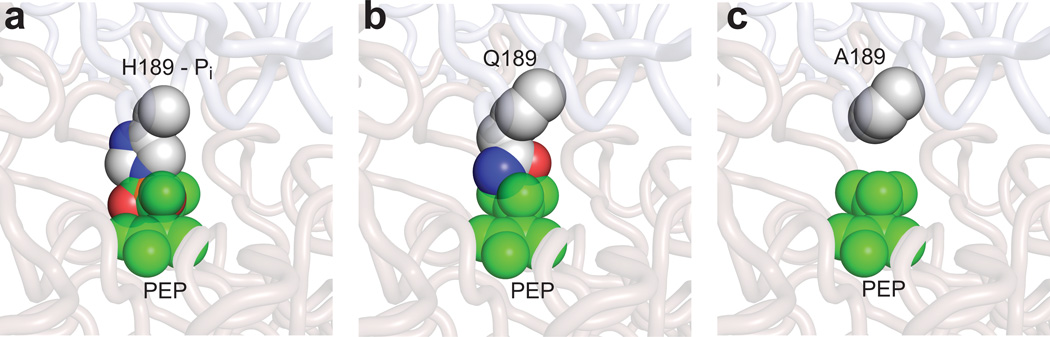

The SAXS data in Figs. 3a and b indicate that PEP binding does not fully stabilize the closed state of EI, resulting in a dynamic equilibrium in which both open and closed forms are populated. This equilibrium is modulated by the nature of the amino acid side chain at position 189 in a manner that can be readily rationalized by simple steric and electrostatic considerations. In particular, addition of PEP to samples of EIWT results in rapid phosphorylation of the active site H189. Steric and electrostatic repulsion between the phosphoryl group of PEP and phosphorylated H189 destabilizes the closed form of EI (Fig. 4a), thereby keeping the enzyme in the open state (Fig. 3a) with the phosphoryl group of H189 exposed and available for in-line phosphoryl transfer to HPr. For the EIQ-PEP complex, Q189 cannot be phosphorylated by PEP, and only minor contacts between PEP and the side chain of Q189 are formed (Fig. 4b). The weaker repulsion between Q189 and PEP results in partial stabilization of the closed state of EI, consistent with the larger population (~11%) of closed state obtained from analysis of the SAXS data for the EIQ-PEP complex (Fig. 3a). When the active site H189 is mutated to Ala, no contacts are formed between PEP and A189 (Fig. 4c) resulting in the largest population of closed state (~62%) derived from analysis of the SAXS data (Fig. 3a). Thus, we conclude that no direct contacts between PEP and the EIN domain are required to trigger the open-to-closed transition of EI.

Figure 4. Effect of mutations at position 189 on the EI-PEP structure.

(a) X-ray structure of the closed, phosphorylated intermediate of EI11 with PEP modeled in place of oxalate. (b) H189 replaced by Gln. (c) H189 mutated to Ala. Mutations were carried out using Pymol (http://www.pymol.org/). PEP is shown as transparent green spheres. The phosphorylated H189, and the Gln and Ala residues are shown as solid spheres (carbon, gray; oxygen, red; nitrogen, blue; phosphorus, orange).

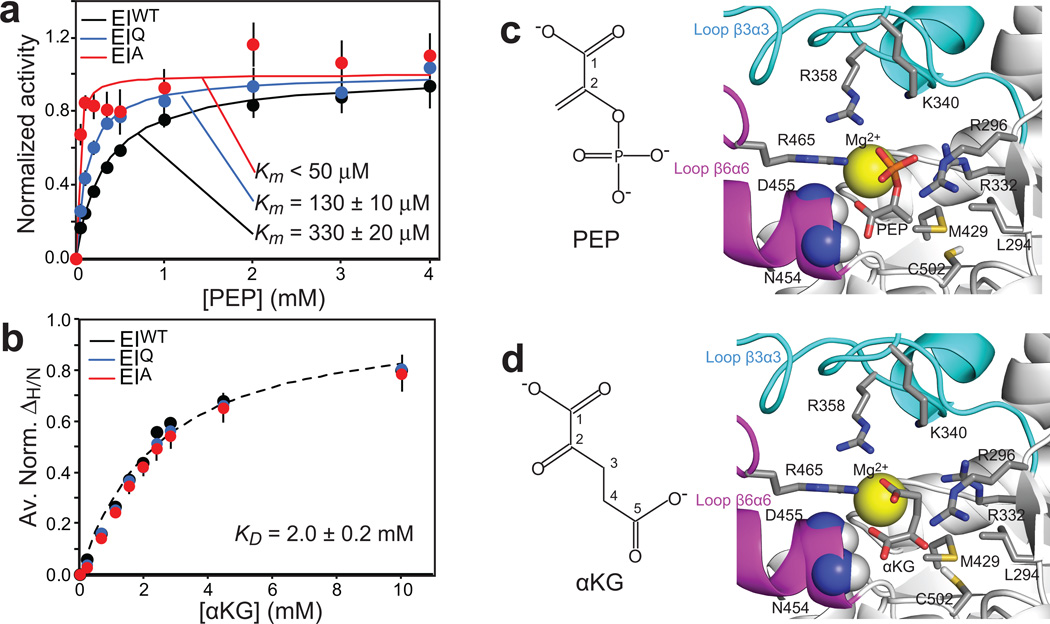

The conclusions drawn from the SAXS analysis correlate well with the affinities of EIWT, EIA and EIQ for PEP and αKG. Enzyme kinetic assays indicate that the affinity of PEP for EIWT (Km ~ 330±20 µM) is two times lower than for EIQ (Km ~ 130±10 µM) and about an order of magnitude lower than for EIA (Km < 50 µM) (Fig. 5a), reflecting the fact that only the open form of EI can release the substrate/product from the binding pocket on the EIC domain. In contrast, NMR titration experiments show that mutations of H189 have no effect on the affinity of the EI for αKG (KD ~ 2.0±0.2 mM, Fig. 5b), confirming that this small molecule inhibitor does not perturb the overall structure of EI. It is also worth noting that the affinities of isolated EIC for PEP (Km ~ 370±30 µM)17 and αKG (KD ~ 2.2±0.2 mM),8 are the same (within experimental error) as the affinities of full-length EIWT for PEP and of EIWT, EIQ and EIA for αKG, in agreement with the conclusion from SAXS analysis that the EIWT-PEP and all the investigated EI complexes with αKG adopt a fully open conformation (Fig. 3a).

Figure 5. Effect of mutations at position 189 on the affinity of EI for PEP and αKG.

(a) Michaelis-Menten kinetics for EIWT (black), EIQ (blue) and EIA (red) with the substrate PEP. Experimental velocities were normalized to the maximum velocity obtained by the individual fits (solid lines). (b) ΔH/N values for EIWT (black), EIQ (blue) and EIA (red) as a function of αKG concentration. Data for all residues showing ΔH/N > 0.1 ppm at 10 mM αKG were fit simultaneously using a one-site binding model per subunit (see Methods). The 3 datasets can be fit with the same KD value (dashed line). In the figure, the ΔH/N values were normalized respect to the fitted ΔH/N at saturation and averaged out over all the residues used in the fitting procedure. The error bars are set to one standard deviation. (c,d) Structural models of PEP17 and αKG8, respectively, bound to the EIC domain. Ligands and side chains involved in the interactions are shown as sticks (carbon, grey; nitrogen, blue; oxygen, red; phosphorus, orange; sulfur, yellow). Backbone amides of N454 and D455 are shown as sphere (nitrogen, blue; hydrogen, white). The magnesium ion is displayed as a yellow sphere. β3α3 and β6α6 loops are colored cyan and pink, respectively (note that both β3α3 and β6α6 loops contain a short α-helical region). The molecular structures of PEP and αKG are shown on the left. (error bars: 1 s.d.)

Effect of PEP and αKG on µs-ms dynamics of EI

The results presented in the previous section clearly indicate that the open-to-closed transition of EI is induced by PEP-binding to the EIC domain with no requirement for direct interactions between the substrate and EIN domain. On the other hand, αKG, which shares most of the same interactions as PEP with the EIC domain (Figs. 5c and d), does not affect the relative positioning of the EIN domain. Inspection of the various EI X-ray structures shows very little variability in the coordinates of the EIC domain (backbone r.m.s.d. to the mean coordinate positions of 2 Å for residues 261-572, Supplementary Fig. 3), irrespective of the presence of ligands bound to EI. It is therefore not evident how PEP-binding triggers the massive conformational rearrangement from the open to closed state.

Using 15N NMR relaxation dispersion experiments, we recently showed that the PEP binding pocket of isolated EIC undergoes a dynamic conformational equilibrium on the submillisecond time-scale (kex ~ 1,500 s−1) between a major (“expanded”) state (population ~ 97%) and a minor state (population ~ 3%) that is more “compact” (in terms of several loops) and closely resembles the PEP-bound state.17 To investigate whether PEP and αKG affect this conformational equilibrium in full-length EI, we analyzed the µs-ms dynamics of EIWT, EIQ and EIA, in the presence and absence of ligands, using 1H-13C Multiple-Quantum (MQ)21 and 13C Single-Quantum (SQ)22 Carr-Purcell-Meinboom-Gill (CPMG)23 relaxation dispersion spectroscopy. Experiments were acquired at 600, 800 and 900 MHz on the methyl groups of U-[2H,15N]/Ile(δ1)-13CH3-labeled and U-[2H,15N]/Val,Leu-(13CH3/12C2H3)-labeled EI. Like 15N-CPMG relaxation dispersion, the 13Cmethyl relaxation dispersion experiments probe exchange dynamics between species with distinct chemical shifts on a time scale ranging from ~50 µs to ~10 ms. However, due to favorable relaxation properties, the absence of exchange with water and the 3-fold degeneracy of methyl proton chemical shifts, the 13Cmethyl relaxation dispersion experiments yield data of superior quality for large macromolecular systems24 such as the full-length 128 kDa EI.

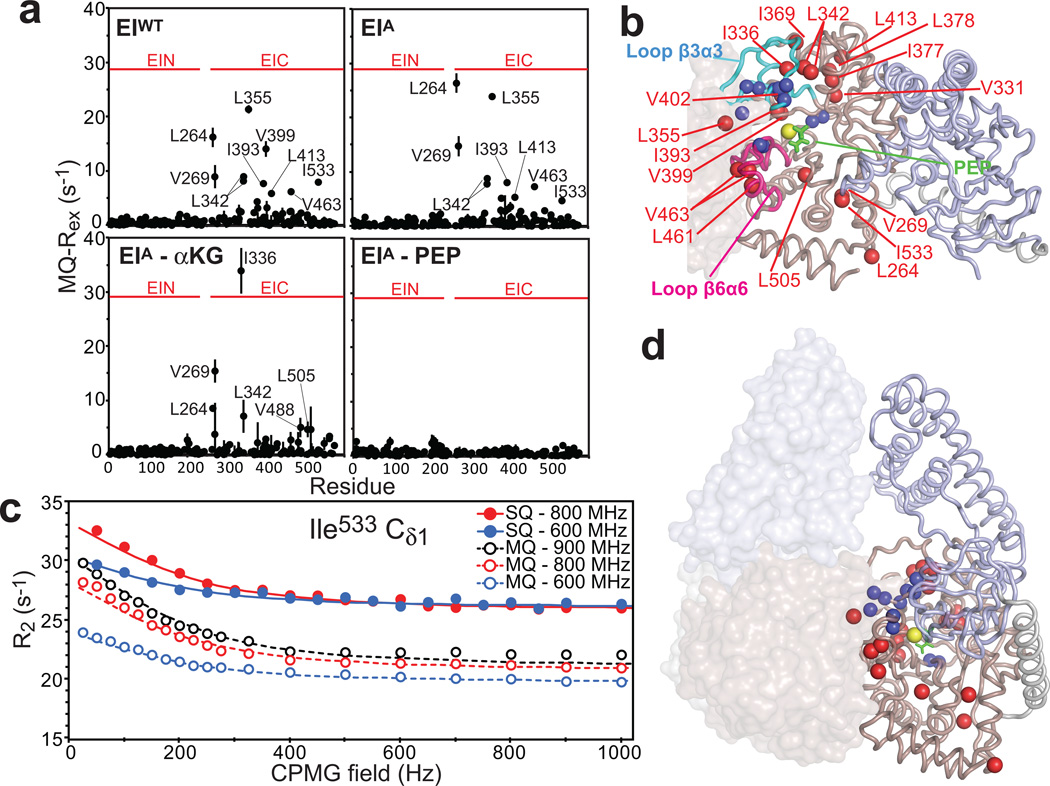

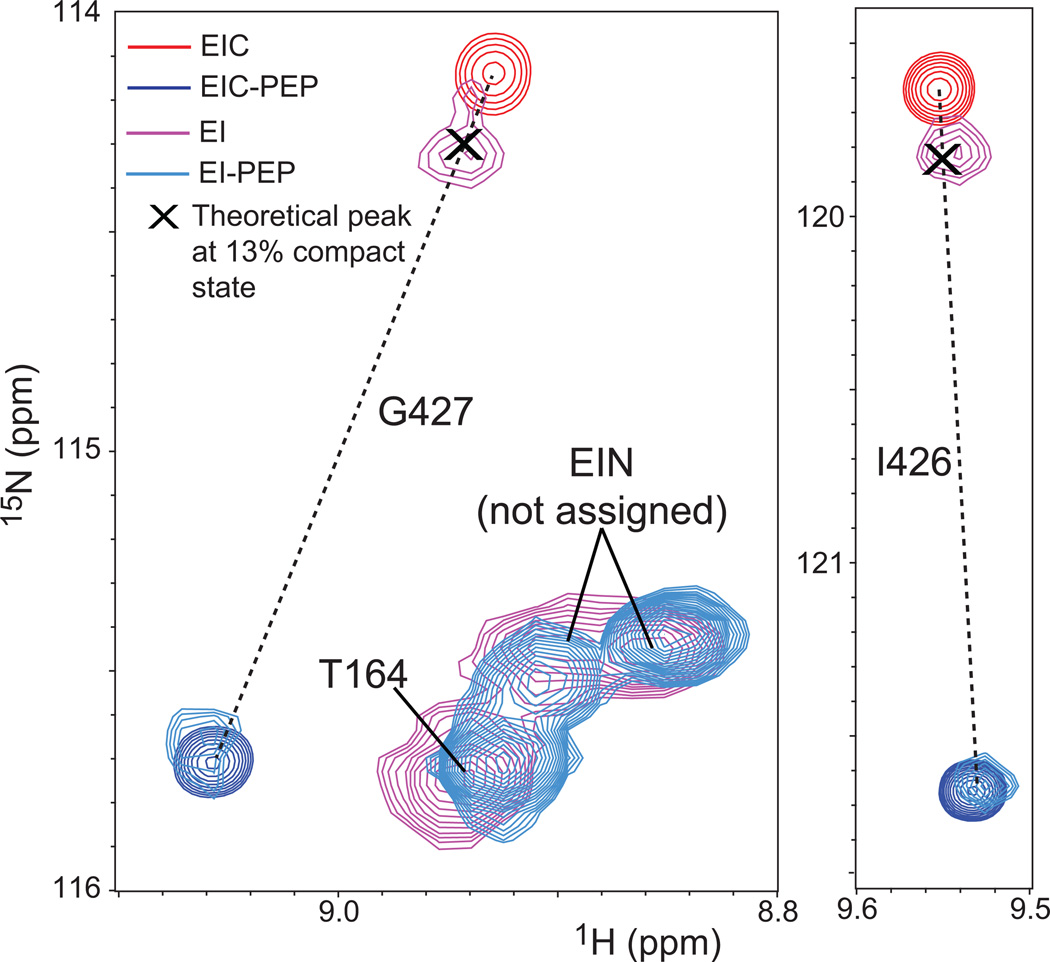

In the absence of ligands, large exchange contributions to the transverse MQ-relaxation rates (MQ-Rex) were detected for several Ile, Val and Leu side chains in EIC domain (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 4). The majority of methyl groups experiencing conformational exchange are located within or in the vicinity of the β3α3 (residues 333–366) and β6α6 (residues 453–477) loops that were shown to be dynamic in isolated EIC (Fig. 6b).17 In addition, large MQ-Rex values were observed for L264, V269 and I533 located in the vicinity of the long helical linker connecting the EIC and EIN domains (Figs. 6a and b). All the MQ and SQ relaxation dispersion curves of the 19 methyl groups exhibiting MQ-Rex values > 3 s−1 at 800 MHz were fit simultaneously to a model describing the interconversion of two conformational states (see Supplementary Methods). In the global fitting procedure, the exchange rate (kex) and the fractional population of the minor state (pB) were optimized as global parameters, while the 13C chemical shift differences between the two conformational states (ΔωC) were treated as methyl-specific parameters. MQ relaxation dispersion curves also depend upon the 1H chemical shift differences between the two conformational states (ΔωH, see Supplementary Methods). However, an initial residue-based fitting (in which kex, pB, ΔωC, and ΔωH were all optimized as methyl-specific parameters) indicated that the contribution of ΔωH to the observed dispersions is negligible for all analyzed methyl groups (Supplementary Fig. 5). Therefore, to improve convergence of the calculation, the methyl-specific ΔωH values were set to zero in the subsequent global fit of the relaxation dispersion curves. An example of the global fit is provided in Fig. 4c. Curves for all the 19 methyl groups as well as the optimized ΔωC values are provided in Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 1, respectively. The overall exchange rate (sum of forward and backward rate constants) is 1,200 ± 50 s−1, and agrees within experimental error with the kex value obtained for the isolated EIC domain (1,500 ± 350 s−1).17 The population of the minor species, however, is 13±5 %, which is considerably larger than the value of 3±1 % obtained from fitting the 15N-CPMG data for isolated EIC.17 Consistent with this latter finding, an overlay of the NMR spectra acquired for full-length EI and the isolated EIC domain shows that, in the absence of ligands, the NMR signals of EIC domain are more shifted towards the bound conformation in the full-length EI protein than in the isolated EIC domain (Fig. 7), indicating that the presence of the EIN domain promotes sampling by the EIC domain of the more compact conformational state that resembles the substrate-bound form.

Figure 6. µs-ms dynamics in full-length EI.

(a) Exchange contribution to the transverse MQ-relaxation rates (MQ-Rex) at 800 MHz measured for samples of EIWT, EIA, EIA-αKG (in the presence of 50 mM αKG) and EIA-PEP (in the presence of 50 mM PEP). Boundaries of the EIN and EIC domains in the full-length EI sequence are highlighted by red horizontal lines. Similar plots are provided for all the analyzed samples in Supplementary Fig. 4. (error bars: 1 s.d.) (b) The 19 methyl groups showing MQ-Rex values > 3 s−1 in free EI are plotted as red spheres on the structure of EI in the open state.10 The EIN and EIC domains are shown as light blue and pink cartoons, respectively. The second subunit of the EI dimer is shown as a transparent surface. Backbone amides showing 15N relaxation dispersions in the isolated EIC domain17 are shown as blue spheres. The β3α3 and β6α6 loops are colored cyan and purple, respectively. PEP is shown as green sticks, and the magnesium ion as a yellow sphere. (c) Examples of typical MQ and SQ relaxation dispersion data at 600 (blue), 800 (red) and 900 (black) MHz. Data are shown for the Ile533-δ methyl group, with the experimental data represented by filled-in (SQ) and open (MQ) circles, and the best-fit curves for a two-site exchange model as solid (SQ) and dashed (MQ) lines. Similar plots for all the analyzed methyl groups are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. (d) Summary of relaxation dispersion data plotted on the structure of the closed state of EI.11 Color coding is the same as in b.

Figure 7. Comparison of the NMR spectra of EI and EIC in the free and bound forms.

Overlay of the 1H-15N TROSY correlation spectra for isolated EIC in the absence (red) and presence (blue) of 50 mM PEP, and for full-length EI in absence (pink) and presence (cyan) of 50 mM PEP. Close-up views of the cross peaks for residues I426 and G427 are provided. The amide groups of I426 and G427 show very large 15N relaxation dispersion in isolated EIC, and experience large PEP-induced chemical shift perturbations.17 Interestingly, I426 and G427 are located more than 15 Å away from the PEP binding site in the structure of the EI-PEP complex, and the changes in chemical shift for these two residues are exclusively dependent upon the change in the populations of the expanded and compact conformational states of EIC induced by PEP-binding.17 Considering that (i) for the isolated EIC in the absence of PEP the population of compact conformer is ~3%,17 (ii) at saturating concentrations of PEP the population of compact EIC is ~100%,17 and (iii) the observed chemical shift is a population weighted average of the chemical shifts of the expanded and compact states, the theoretical position of the cross-peaks for I426 and G427 in the presence of 13% compact state can easily be calculated from the position of the peaks in the spectra of isolated EIC (~3% compact state) and of the isolated EIC-PEP complex (~100% compact state). The positions of the calculated cross-peaks are reported as black crosses, and agree very well with the position of the cross peaks in the spectra of the full-length enzyme in the absence of ligand. These results provide an independent validation of the accuracy of the global fit of the MQ and SQ relaxation dispersion curves.

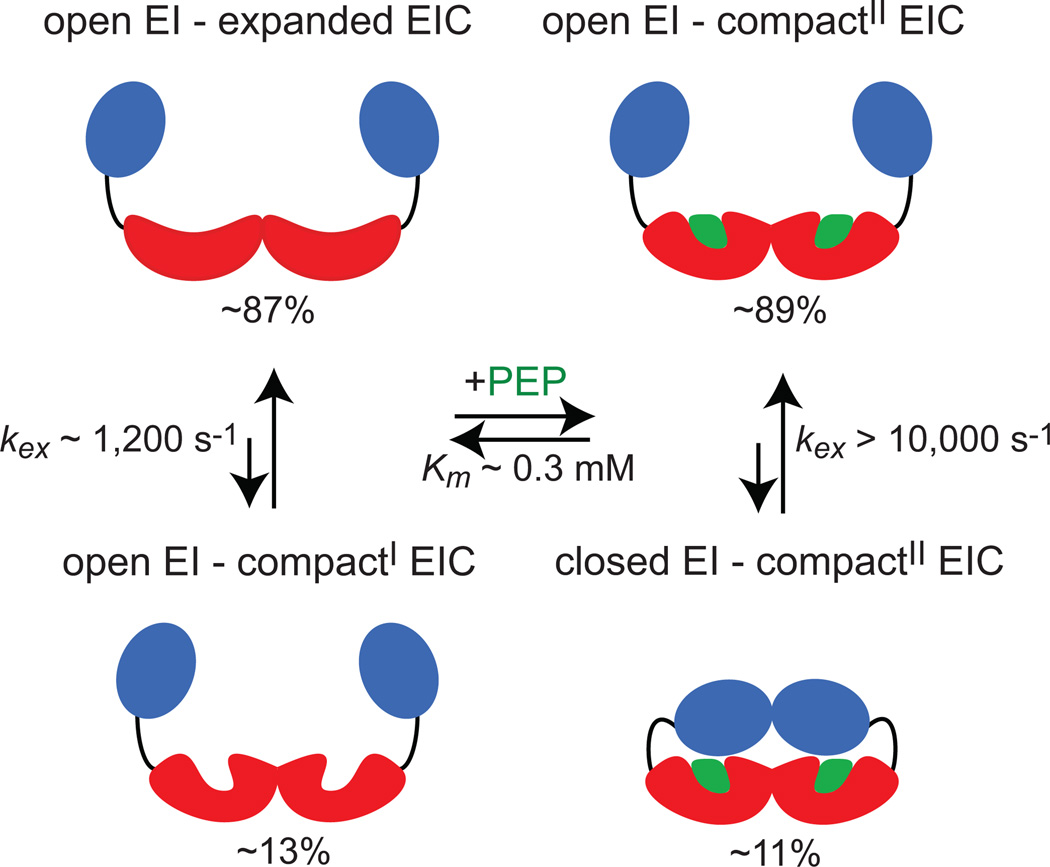

Thus, the 13Cmethyl-CPMG relaxation dispersion data presented above for free EI describe the same conformational equilibrium previously detected in the PEP-binding site of the isolated EIC domain by 15N backbone CPMG relaxation dispersion experiments.17 The 1H-13Cmethyl MQ CPMG relaxation dispersion experiments acquired on EI in the presence of ligands indicate that PEP and αKG affect the conformational equilibrium differently. In particular, analysis of the MQ-Rex data obtained at 800 MHz for the EIQ-PEP and EIA-PEP complexes shows that PEP-binding completely suppresses µs-ms dynamics within the EIC domain (Fig. 6A, and Supplementary Fig. 4). In this regard, the closed form of EI is stabilized by contacts between the α/β subdomain of EIN and the β3α3 and β6α6 loops of EIC, which have been observed to undergo dynamics in the free enzyme (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 7). Structural stabilization of the β3α3 and β6α6 loops in the compact PEP-bound form allows optimal docking of the EIN domain onto the EIC domain, and is therefore responsible for triggering the open-to-closed transition of EI.

We also noticed that, although the chemical shift perturbations induced by PEP on the backbone 15N resonances of isolated EIC closely match the residue specific ΔωN parameters obtained from the fit of the 15N relaxation dispersion data acquired on the C-terminal domain of the enzyme,17 and a moderate correlation is observed between the methyl-specific ΔωC parameters derived from relaxation dispersion data on wild type EI versus the chemical shift perturbations induced by PEP on the 13Cmethyl resonances of full-length EIQ and EIA (ΔC, Supplementary Fig. 8), the measured ΔC values for several methyl groups located within or in the proximity of the β3α3 loop are considerably larger than the corresponding ΔωC values (Supplementary Fig. 8). Taken together, these observations suggest that the compact state transiently sampled by the EIC domain in the absence of PEP while overall is similar to the PEP-bound state, differs from the PEP-bound structure in terms of side-chain packing within and in the proximity of the β3α3 loop (Supplementary Fig. 8). Interestingly, contacts between the α/β subdomain of EIN and the β3α3 loop of EIC account for ~20 % of the interdomain interface in closed EI (Supplementary Fig. 7). The different conformations adopted by the β3α3 loop in the compact states sampled by EIC in the absence (compactI) and presence (compactII) of PEP are consistent with our SAXS analysis indicating that the closed state of EI is significantly populated only in the presence of PEP (Fig. 3a).

αKG, on the other hand, is not able to provide full stabilization of the EIC domain, as evidenced by the fact that several methyl groups with MQ-Rex values > 3s−1 are still observed for the αKG complexes with EIWT, EIA and EIQ (Fig. 6c, and Supplementary Fig. 4). Specifically, large MQ-Rex values for the αKG complexes are observed for residues 331, 336, 342, 355 and 378 within or in the proximity of the β3α3 loop (Fig. 6b, and Supplementary Fig. 9) which does not make contacts with αKG but does interact with PEP (Figs. 5c and d, and Supplementary Fig. 9); likewise large MQ-Rex values are also observed for residues 482, 488 and 505 that are located close to the active site Cys502, which forms hydrophobic contacts with PEP and is involved in one hydrogen bond with the C2 carbonyl group of αKG (Figs. 5c and d, and Supplementary Fig. 9). Other MQ-Rex values > 3 s−1 are detected for residues 264 and 269 that are spatially close to the linker helix. Thus, in the case of the complexes with αKG, the more dynamic state of the long β3α3 loop hampers effective docking of EIN over EIC, thereby destabilizing the closed EI configuration.

As a final note, although the EIN domain of EIA experiences significant PEP-induced chemical shift perturbations (Fig. 2a), and the SAXS data reveal that the closed EI form is highly populated in the presence of PEP (population > 50% for the EIA-PEP complex, Fig. 3), no relaxation dispersions are observed in the EIN domain (Figs. 6a and d), and a single set of cross-peaks is observed in the NMR spectra of all the investigated EI-PEP complexes. These observations indicate that the interdomain rearrangement in EI is too fast (>10,000 s−1) to be detected by CPMG-type relaxation dispersion measurements. The intricate coupling between the open-to-closed dynamics for EI and the expanded-to-compact conformational exchange within the EIC domain revealed by the present work is summarized in Fig. 8.

Figure 8. Coupling between open-to-closed and expanded-to-compact conformational equilibria of EI.

The EIN and EIC domains are colored blue and red, respectively. The PEP molecule is colored green. kex is the exchange rate constant for the conformational equilibrium, and Km the Michaelis constant for the EI-PEP complex. The compact state of EIC exists in two different conformations (compactI and compactII) that differ in side chain packing within and in the proximity of the β3α3 loop (see main text). Populations of the different conformational states are indicated. Populations on the left side of the free/bound equilibrium correspond to the populations obtained from the fit of the relaxation dispersion data acquired on EIWT; populations on the right side correspond to the populations obtained from the fit of the SAXS curves acquired for the EIQ-PEP complex.

Discussion

Addressing the mechanisms whereby small molecule ligands modulate the interactions between protein domains is of paramount importance for understanding fundamental phenomena in biology such as protein switches and allostery. In this Communication, we have investigated the effect of two small molecules on the interaction between the EIN and EIC domains of EI, the first component of the bacterial phosphotransferase system. The open-to-closed conformational change induced by substrate binding to EI (Fig. 1a) is one of the largest ligand-induced interdomain rearrangements reported in the literature so far. Although there is now a wealth of structural studies on EI and its complexes,8, 10, 11, 17, 25–29 the fundamental forces driving this conformational rearrangement were not evident. Here, we have shown that binding of the substrate PEP to the EIC domain of EI results in structural stabilization of the otherwise dynamic loops of EIC that form a large portion of the interface between the EIC and EIN domains in the structure of the closed state of EI. This finding provides a direct link between ligand binding and the open-to-closed conformational transition, and is a clear example of how conformational dynamics and small-molecule binding have co-evolved to confer the proper biological function upon this enzyme. Ligand-induced stabilization (or destabilization) of the interface between protein domains may be a common mechanism by which small-molecule binding propagates into large interdomain rearrangements, and may serve as the basis for interdomain communication in a recently discovered class of allosteric proteins where disorder-to-order transitions induced by ligand-binding within one domain were shown to be associated with changes in the spectral and thermodynamic properties of adjacent structural motifs.30–33

Methods

Protein expression and purification

Mutants of E. coli EI (H189Q and H189A) were made using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). EI (wild type and mutants) was expressed and purified as described previously.17 U-[2H,15N]/Val,Leu-(13CH3/12C2H3)-labeled and U-[2H,15N]/Ile(δ1)-13CH3-labeled EI samples were prepared following standard protocols for specific isotopic labeling of the methyl groups of Ile, Leu and Val side chains.34

Small-Angle X-ray scattering

SAXS data were collected on samples of EI (6 mg/mL corresponding to ~48 µM dimer) in 20 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 tablet of cOmplete, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Ligands were added to a final concentration of 20 mM immediately before data acquisition. SAXS data were acquired at Beamline 12-IDC at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL) at protein concentrations ranging from 1.5 to 6 mg/mL. Data collection was done using a Gold CCD detector positioned at 2 m from the sample capillary. Incident radiation with an energy of 18 keV was used, resulting in observable q-ranges of 0.014−0.24 Å−1. Q-axis mapping was done using scattering from a silver behenate standard sample. A total of 20 sequential data frames with exposure times of 1.5 s was recorded with the samples kept at 25°C throughout the measurement. To prevent radiation damage, volumes of 100 µL of samples and buffers were oscillated during data collection using a flow-though setup. Individual data frames were masked, corrected for the detector sensitivity, radially integrated and normalized by the corresponding transmitted beam intensities. The final 1D scattering profiles and their uncertainties were calculated as means and standard deviations over the 20 individual frames.

Subtraction of the buffer data and analysis of the scattering profiles was carried out using the Xplor-NIH calcSAXS-bufSub helper program (see Supplementary Methods).19 The SAXS data were fit using a linear combination of the experimental 3D structures of E. coli EI in the open (PDB code: 2KX9)9 and closed (PDB code: 2HWG)10 conformational states. Fits were performed for q values in the range 0.02-0.16 Å−1. In this range, SAXS data are characterized by very high signal-to-noise ratio and are mainly dependent on the overall shape of the molecule (i.e. contributions from small rearrangements within the domains are negligible).17

NMR spectroscopy

NMR samples were prepared in 20 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, and either 90% H2O/10% D2O (for NMR experiments acquired on the backbone amides) or 100% D2O (for experiments acquired on methyl groups). The protein concentration (in subunits) was 0.3 and 1.0 mM for experiments run in the presence and in the absence of PEP, respectively. The concentrations of PEP and αKG used in the relaxation dispersion experiments were 50 mM.

NMR spectra were recorded at 37°C on Bruker 900, 800 and 600 MHz spectrometers equipped with z-shielded gradient triple resonance cryoprobes. Spectra were processed using NMRPipe35 and analyzed using the program SPARKY. 1H-15N TROSY36 and 1H-13Cmethyl TROSY24 experiments were acquired using previously described pulse schemes. Resonance assignments of the 1H-15N and 1H-13Cmethyl TROSY spectra of free EI were achieved by transferring the assignments obtained for the isolated EIN37, 38 and EIC17, 39 domains on the spectra of full-length EI (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). Only non-stereospecific assignments were available for the methyl groups of the Leu and Val residues in the EIC domain. Therefore, methyl-TROSY correlations for such resonances were arbitrarily assigned as δA and δB (for Leu), and γA and γB (for Val). A total of 256 1H-15N and 227 1H-13Cmethyl correlations were assigned. Assignments of the NMR correlations for the EI-PEP and EI-αKG complexes were performed by titration experiments, following the change in cross-peak positions as a function of added ligand. Weighted combined 1HN/15N (ΔH/N) and 1H/13C (ΔH/C) chemical shift perturbations resulting from the addition of 5 mM PEP and 10 mM αKG were calculated using the following equation:40 ΔH/N,C = ((ΔδH WH)2 + (ΔδN,C WN,C)2)1/2, where WH, WN, and WC are weighing factors for the 1H, 15N and 13C shifts, respectively (WH = |γH/γH| = 1, WN = |γN/γH| = 0.101, WC = |γC/γH| = 0.251); ΔδH, ΔδN and ΔδC are the 1H, 15N and 13C chemical shift differences in ppm, respectively, between free and bound states; and γH, γN and γC are the 1H, 15N and 13C gyromagnetic ratios, respectively.

Pulse schemes for acquisition of 1H-13C Multiple Quantum (MQ)21 and 13C Single Quantum (SQ)22 CPMG relaxation dispersion experiments have been described by Kay and coworkers. Experiments were performed at 600, 800 and 900 MHz with a fixed relaxation delay but a changing number of refocusing pulses to achieve different effective CPMG fields.41 The transverse relaxation periods were set to 30 and 40 ms for experiments run on U[2H,15N]/Val,Leu-(13CH3/12C2H3)-labeled EI and on U-[2H,15N]/Ile(δ1)-13CH3-labeled EI, respectively. The resulting MQ and SQ relaxation dispersion curves were fit to a two-state exchange model using the Carver-Richards equation42 (see Supporting Methods).

Binding assays

The enzymatic activity of EI for the hydrolysis of PEP to inorganic phosphate and pyruvate was assayed spectrophotometrically at 37°C using the EnzChek Phosphate Assay Kit (Invitrogen) and a nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer, as described previously.17 Michaelis constants (Km) for the PEP complexes with EIWT, EIA and EIQ were obtained by fitting the enzymatic velocities to the Michaelis-Menten equation.

The affinity of αKG for EIWT, EIA and EIQ was measured at 37°C by means of NMR titration experiments. Equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) were obtained by fitting the changes in the weighted combined 1HN/15N chemical shifts (ΔH/N, see NMR Spectroscopy) with increasing concentration of αKG using the equation:43

| (1) |

where Δ0 is the weighted combined 1HN/15N chemical shift at saturation, and P and L are the protein and ligand concentrations, respectively. The chemical shift perturbation curves for residues with ΔH/N values > 0.1 ppm in the presence of 10 mM αKG were fit simultaneously using the same KD value.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Seifert and X. Zuo for assistance with SAXS data collection and gratefully acknowledge use of the Advanced Photon Source, supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, contract No. W-31-109-ENG-38, and the shared scattering beamline resource allocated under the PUP-77 agreement between NCI, NIH, and the Argonne National Laboratory. This work was supported by funds from the NIH Intramural Programs of NIDDK (to G.M.C.) and CIT (to C.S.D.) and from the Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program of the Office of the Director of the NIH (to G.M.C.).

Footnotes

Author contributions

V.V. and G.M.C. designed research; V.V., V.T. and A.G. performed research; V.V., C.D.S. and G.M.C. analyzed data; and V.V. and G.M.C. wrote the paper.

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Bennett WS, Huber R. Structural and functional aspects of domain motions in proteins. CRC Crit Rev Biochem. 1984;15:291–384. doi: 10.3109/10409238409117796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulz GE. Domain motions in proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1991;1:883–888. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berendsen HJ, Hayward S. Collective protein dynamics in relation to function. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:165–169. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerstein M, Lesk AM, Chothia C. Structural mechanisms for domain movements in proteins. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6739–6749. doi: 10.1021/bi00188a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meadow ND, Fox DK, Roseman S. The bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate: glycose phosphotransferase system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:497–542. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.002433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clore GM, Venditti V. Structure, dynamics and biophysics of the cytoplasmic protein-protein complexes of the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate: sugar phosphotransferase system. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38:515–530. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doucette CD, Schwab DJ, Wingreen NS, Rabinowitz JD. α-Ketoglutarate coordinates carbon and nitrogen utilization via enzyme I inhibition. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:894–901. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venditti V, Ghirlando R, Clore GM. Structural basis for enzyme I inhibition by alpha-ketoglutarate. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:1232–1240. doi: 10.1021/cb400027q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chauvin F, Fomenkov A, Johnson CR, Roseman S. The N-terminal domain of Escherichia coli enzyme I of the phosphoenolpyruvate/glycose phosphotransferase system: molecular cloning and characterization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7028–7031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwieters CD, Suh JY, Grishaev A, Ghirlando R, Takayama Y, Clore GM. Solution structure of the 128 kDa enzyme I dimer from Escherichia coli and its 146 kDa complex with HPr using residual dipolar couplings and small- and wide-angle X-ray scattering. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13026–13045. doi: 10.1021/ja105485b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teplyakov A, et al. Structure of phosphorylated enzyme I, the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system sugar translocation signal protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16218–16223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607587103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motlagh HN, Wrabl JO, Li J, Hilser VJ. The ensemble nature of allostery. Nature. 2014;508:331–339. doi: 10.1038/nature13001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takayama Y, Schwieters CD, Grishaev A, Ghirlando R, Clore GM. Combined use of residual dipolar couplings and solution X-ray scattering to rapidly probe rigid-body conformational transitions in a non-phosphorylatable active-site mutant of the 128 kDa enzyme I dimer. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:424–427. doi: 10.1021/ja109866w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel HV, Vyas KA, Savtchenko R, Roseman S. The monomer/dimer transition of enzyme I of the Escherichia coli phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17570–17578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508965200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yun YJ, Choi BS, Kim EH, Suh JY. Thermodynamic dissection of large-scale domain motions coupled with ligand binding of enzyme I. Protein Sci. 2013;22:1602–1611. doi: 10.1002/pro.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimitrova MN, Szczepanowski RH, Ruvinov SB, Peterkofsky A, Ginsburg A. Interdomain interaction and substrate coupling effects on dimerization and conformational stability of enzyme I of the Escherichia coli phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. Biochemistry. 2002;41:906–913. doi: 10.1021/bi011801x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venditti V, Clore GM. Conformational selection and substrate binding regulate the monomer/dimer equilibrium of the C-terminal domain of Escherichia coli enzyme I. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:26989–26998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.382291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch MH, Vachette P, Svergun DI. Small-angle scattering: a view on the properties, structures and structural changes of biological macromolecules in solution. Q Rev Biophys. 2003;36:147–227. doi: 10.1017/s0033583503003871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hura GL, et al. Robust, high-throughput solution structural analyses by small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) Nat Methods. 2009;6:606–612. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwieters CD, Clore GM. Using small angle solution scattering data in Xplor-NIH structure calculations. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2014;80:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korzhnev DM, Kloiber K, Kanelis V, Tugarinov V, Kay LE. Probing slow dynamics in high molecular weight proteins by methyl-TROSY NMR spectroscopy: application to a 723-residue enzyme. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3964–3973. doi: 10.1021/ja039587i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundstrom P, Vallurupalli P, Religa TL, Dahlquist FW, Kay LE. A single-quantum methyl 13C-relaxation dispersion experiment with improved sensitivity. J Biomol NMR. 2007;38:79–88. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loria JP, Rance M, Palmer AG. A relaxation-compensated Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill sequence for characterizing chemical exchange by NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:2331–2332. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tugarinov V, Hwang PM, Ollerenshaw JE, Kay LE. Cross-correlated relaxation enhanced 1H-13C NMR spectroscopy of methyl groups in very high molecular weight proteins and protein complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10420–10428. doi: 10.1021/ja030153x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suh JY, Cai M, Clore GM. Impact of phosphorylation on structure and thermodynamics of the interaction between the N-terminal domain of enzyme I and the histidine phosphocarrier protein of the bacterial phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18980–18989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802211200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marquez J, Reinelt S, Koch B, Engelmann R, Hengstenberg W, Scheffzek K. Structure of the full-length enzyme I of the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar phosphotransferase system. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32508–32515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oberholzer AE, Schneider P, Siebold C, Baumann U, Erni B. Crystal structure of enzyme I of the phosphoenolpyruvate sugar phosphotransferase system in the dephosphorylated state. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33169–33176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.057612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oberholzer AE, et al. Crystal structure of the phosphoenolpyruvate-binding enzyme I-domain from the Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis PEP: sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS) J Mol Biol. 2005;346:521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navdaeva V, et al. Phosphoenolpyruvate: sugar phosphotransferase system from the hyperthermophilic Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis. Biochemistry. 2011;50:1184–1193. doi: 10.1021/bi101721f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keramisanou D, et al. Disorder-order folding transitions underlie catalysis in the helicase motor of SecA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:594–602. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freiburger LA, Baettig OM, Sprules T, Berghuis AM, Auclair K, Mittermaier AK. Competing allosteric mechanisms modulate substrate binding in a dimeric enzyme. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:288–294. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reichheld SE, Yu Z, Davidson AR. The induction of folding cooperativity by ligand binding drives the allosteric response of tetracycline repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:22263–22268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911566106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhuravleva A, Clerico EM, Gierasch LM. An interdomain energetic tug-of-war creates the allosterically active state in Hsp70 molecular chaperones. Cell. 2012;151:1296–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tugarinov V, Kanelis V, Kay LE. Isotope labeling strategies for the study of high-molecular-weight proteins by solution NMR spectroscopy. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:749–754. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pervushin K, Riek R, Wider G, Wuthrich K. Attenuated T2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole-dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12366–12371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garrett DS, Seok YJ, Liao DI, Peterkofsky A, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. Solution structure of the 30 kDa N-terminal domain of enzyme I of the Escherichia coli phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system by multidimensional NMR. Biochemistry. 1997;36:2517–2530. doi: 10.1021/bi962924y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Venditti V, Fawzi NL, Clore GM. Automated sequence- and stereo-specific assignment of methyl-labeled proteins by paramagnetic relaxation and methyl-methyl nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy. J Biomol NMR. 2011;51:319–328. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9559-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tugarinov V, Venditti V, Marius Clore G. A NMR experiment for simultaneous correlations of valine and leucine/isoleucine methyls with carbonyl chemical shifts in proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2014;58:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9803-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mulder FA, Schipper D, Bott R, Boelens R. Altered flexibility in the substrate-binding site of related native and engineered high-alkaline Bacillus subtilisins. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:111–123. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulder FA, Skrynnikov NR, Hon B, Dahlquist FW, Kay LE. Measurement of slow (micros-ms) time scale dynamics in protein side chains by 15N relaxation dispersion NMR spectroscopy: application to Asn and Gln residues in a cavity mutant of T4 lysozyme. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:967–975. doi: 10.1021/ja003447g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carver JP, Richards RE. A general two-site solution for the chemical exchange produced dependence of T2 upon the Carr-Purcell pulse separation. J Magn Reson. 1972;6:89–105. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Granot J. Determination of dissociation constants of 1:1 complexes from NMR data. Optimization of the experimental setup by statistical analysis of simulated experiments. J Magn Reson. 1983;55:216–224. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.