Abstract

Objective

To determine whether adolescents who self-harm are at increased risk of heavy and dependent substance use in adulthood.

Method

Fifteen-year prospective cohort study of a random sample of 1943 adolescents recruited from secondary schools across the state of Victoria, Australia. Data pertaining to self-harm and substance use was obtained at seven waves of follow-up, from mean age 15.9 years to mean age 29.1 years.

Results

Substance use and self-harm were strongly associated during the adolescent years (odds ratio (OR): 3.3, 95% CI 2.1–5.0). Moreover, adolescent self-harmers were at increased risk of substance use and dependence syndromes in young adulthood. Self-harm predicted a four-fold increase in the odds of multiple dependence syndromes (sex- and wave-adjusted OR: 4.2, 95% CI: 2.7–6.6). Adjustment for adolescent anxiety/depression attenuated but did not eliminate most associations. Adolescent substance use confounded all associations, with the exception of multiple dependence syndromes, which remained robustly associated with adolescent self-harm (fully adjusted odds ratio: 2.0, 95% CI: 1.2–3.2).

Conclusion

Adolescent self-harm is an independent risk factor for multiple dependence syndromes in adulthood. This level of substance misuse is likely to contribute substantially to the premature mortality and disease burden experienced by individuals who self-harm.

Keywords: self-harm, substance-related disorders, epidemiology

Significant outcomes

Adolescent self-harm is an independent risk factor for multiple dependence syndromes in adulthood.

The association between adolescent self-harm and adult substance abuse is not fully accounted for by adolescent depression or anxiety.

Adolescents who self-harm may benefit from early interventions targeting substance abuse.

Limitations

We used a broad definition of self-harm that encompassed behaviours with and without suicidal intention.

Non-response may have affected our findings.

All data on self-harm and substance use were based on self-report.

Introduction

Self-harm is an act with a non-fatal outcome in which an individual deliberately initiates behaviour (such as self-cutting), or ingests a substance, an illicit drug or non-ingestible substance or object, with the intention of causing harm to themselves 1. It is one of the strongest predictors of completed suicide 2,1,3. Self-harm is common in adolescence where it often co-occurs with common mental disorder 4. Fortunately, however, for the majority of young people, self-harm appears to be a transitory phenomenon 5. Resolution of self-harm may occur as a result of learning new strategies for dealing with difficult emotions 6. Changes in social and affective processing occurring during adolescence may also play an important role in the resolution of self-harm 7. Yet, evidence is growing that self-harmers have other serious health risks that may persist into adulthood 8. For example, in adolescence, self-harm has been linked to eating disorders 9, reckless driving 10 and substance use 11,12. In young people, substance use is an established correlate of self-harm 13, but it is unknown whether teenagers who self-harm are at increased risk of dependent use of alcohol and drugs in their adult years. The existence of a prospective association between adolescent self-harm and adult substance dependence would add weight to the importance of detecting and intervening with self-harmers during their adolescent years.

Aims of the study

In this study, using a repeated measures cohort of a representative community sample of adolescents, we set out to determine whether there is a prospective association between adolescent self-harming behaviour and substance dependence in adulthood. One of the functions of self-harm is affect regulation. Alcohol and drugs are also commonly used to relieve emotional symptoms, and we therefore specifically hypothesized that adolescent self-harmers would be at increased risk of substance abuse and dependence in adulthood. We also hypothesized that this increased risk would be partially explained, (i) by the presence of adolescent symptoms of common mental disorder and (ii) by previous substance use in adolescence.

Material and methods

Sample

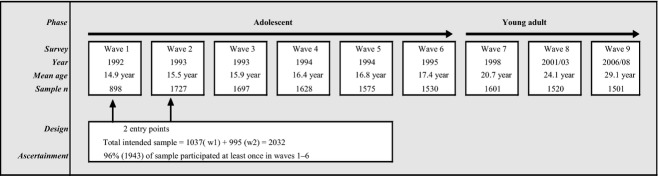

Between August 1992 and January 2008, we conducted a nine-wave cohort study of health in young people living in the state of Victoria, Australia. Data collection protocols were approved by The Royal Children's Hospital's Ethics in Human Research Committee. Informed parental consent was obtained before inclusion in the study. At baseline, a representative sample of the Victorian population of school pupils aged 14–15 years (year 9) was selected. School retention rates to year nine in the year of sampling were 98%. We used a two-stage cluster sampling procedure to define the study population. At stage 1, 45 schools were chosen at random from a stratified frame of government, Catholic and independent schools, with a probability proportional to the number of students aged 14–15 years in the schools in each stratum in the state. One school with 13 students declined continued participation in the cohort study leaving a total study sample of 44 schools. At stage 2, a single intact class was selected at random from each participating school. Thus, one class entered the study in the latter part of the ninth school year (wave 1) and the second class 6 months later (wave 2). Participants were subsequently reviewed at a further four 6-month intervals (waves 3–6) with three follow-up waves in young adulthood aged 20–21 years (wave 7), 24–25 years (wave 8) and 28–29 years (wave 9). Figure1 displays the flow of participants through the study.

Fig 1.

Sampling and ascertainment in the Victorian Adolescent Health Cohort, 1992–2008.

From a total intended sample of 2032 students, 1943 (95.6%) participated at least once during the first six (adolescent) waves. Seventy-six invited participants were either refused consent by their parents or were never available for interview.

In waves 1–6, participants self-administered the questionnaire on laptop computers with telephone follow-up of those absent from school from wave 3. The 7–9 waves were undertaken with computer-assisted telephone interviews. In general, we used the same measures for time-varying outcomes and covariates to ensure comparability across waves. Participants were not asked about self-harm until wave 3, when the cohort was engaged and we judged it reasonable to ask more sensitive questions. In wave nine, 1501 participants were interviewed between May 2006 and January 2008, 1395 of whom completed the telephone interview, including the self-harm component and 106 (who were keen to participate, but had limited time) who completed partial surveys without the self-harm items.

Adolescent measures (waves 3–6)

Self-harm was assessed using the following question: ‘In the last [reference period], have you ever deliberately hurt yourself or done anything that you knew might have harmed you or even killed you?’ The reference period was the past year for wave 3 and 4 and past 6 months for the remaining waves. Participants who responded positively to the main question were then asked to describe the nature and timing of each episode. These detailed responses were then coded into five subtypes of self-harm by GP and confirmed by PM. A dichotomous (yes/no) variable was created for each subtype: cutting or burning, self-poisoning, deliberate non-recreational risk-taking, self-battery, and other (including attempted self-drowning, hanging, intentional electrocution and suffocating). Individuals could have reported more than one category of self-harm within a wave or in different waves. They were classified with ‘any self-harm’ by wave if they were identified to have reported any of these individual categories. A summary measure of any adolescent self-harm was created from wave 3–6, with the response assumed to be ‘no occurrence’ when the wave was missing.

Clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety were assessed using the revised Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R) 14 in waves 3–6. The CIS-R is a branched psychiatric interview designed to assess symptoms of depression and anxiety in non-clinical populations. The total scores on the CIS-R were dichotomized so that scores ≥12 delineated a mixed depression-anxiety state at a lower threshold than syndromes of major depression and anxiety disorder, but where clinical intervention would be appropriate 14.

Cannabis use

At each wave, participants reported their frequency of cannabis use in the past 6 months. We identified those who reported any use in this time period as cannabis users.

Cigarette smoking

Participants who reported that they had smoked cigarettes in the past month were classified as cigarette smokers at each wave.

Alcohol use was assessed using a beverage- and quantity-specific one-week diary. Binge drinking was calculated according to Australian guidelines 15 from the total alcohol consumed on each drinking day during the week prior to survey, and defined as ≥5 standard drinks (one standard drink = 10 gm alcohol) on at least one day.

Measures of depression and anxiety symptoms, cannabis use, cigarette smoking and binge drinking were summarized from waves three to six (with the response assumed to be “no occurrence” when the wave was missing): no symptoms, symptoms at one wave and symptoms at two or more waves.

Parental divorce or separation in adolescence (by wave 6) was identified either prospectively or retrospectively if adolescent was absent at wave 6.

Highest level of parental education in adolescence: secondary school not completed; seconday school completed or vocational qualification, university degree.

School type: government, Catholic, independent.

Young adult outcomes measures (waves 7–9)

Cigarette smoking

Participants reporting that they had smoked cigarettes on 6 or 7 days in the past week were classified as daily cigarette smokers.

Nicotine dependence was assessed at each wave using the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence. Nicotine dependence was defined at a cut-off point of >3 which corresponds with a cut-off point of >6 on the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire 16.

Illicit substance use

At each wave, participants were asked to report their maximum frequency of use over the last 12 months of cannabis, ecstasy, cocaine and amphetamines. For each substance, we identified participants who reported any use in the last 12 months.

Cannabis dependence was assessed using the computerized Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI 2.1, 12-month version) in participants reporting at least weekly cannabis use in the past 12 months. We applied this filter to minimize responder fatigue as we considered that a diagnosis of cannabis dependence was only consistent with regular cannabis use, given the DSM-IV description of substance dependence as occurring with a ‘pattern of repeated (substance) self-administration’17.

Past week drinking was identified using a beverage- and quantity-specific, four-day diary including all weekend days (Friday to Sunday) and the most recent weekday. Heavy binge drinking was defined as >20 standard drinks (one standard drink = 10 gm alcohol) for males and >11 standard drinks, for females in the past week. This cut-off was based on previous research with young people in Victoria 18.

Alcohol abuse and dependence using DSM-IV criteria was assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI 2.1, 12-month version) 19 and together are referred to as ‘alcohol abuse and dependence’.

Any and multiple illicit substance use measures

The number of illicit substances used was counted at each wave and classified into two measures to identify individuals who were using any and multiple illicit substances at each wave.

Any and multiple substance dependence measures

Any and multiple dependence at each wave was identified from measures of nicotine and cannabis dependence and alcohol abuse and dependence.

Analysis

The analysis dataset was restricted to those participants who had at least one complete wave of data during adolescence and at least one complete wave in young adulthood and complete parental information. First, we examined the associations between summary measure of adolescent self-harm with background demographic factors, summary measures of adolescent substance use and anxiety and depression (Table1). The prevalence of substance use was then estimated for each young adult wave, stratified by the summary measure of adolescent self-harm (Table2). Finally, we estimated the association of any adolescent self-harm with each young adult substance use outcome, using generalized estimating equations with robust standard errors to allow for repeated measures within individuals. We generated a series of predictive models, initially adjusting for wave of observation and sex of the participant and sequentially adding potential confounders (i) school type, parental divorce/separation and highest level of parental education, then (ii) adolescent symptoms of anxiety and depression, then, finally (iii) the three adolescent substance-use summary measures of binge drinking, cigarette smoking and cannabis use. Sequential adjustment allowed for the effect of potential confounders on the association between adolescent self-harm and the adult outcomes to be investigated.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, adolescent substance use and adolescent symptoms of depression and anxiety by adolescent self-harm (waves 3–6) in 1627 participants with observations in both the adolescent and young adult phases

| Background and adolescent measure | No self-harm (n = 1494) | Self-harm (n = 133) |

|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 47 (44–50) | 37 (29–45) |

| Female | 53 (50–56) | 63 (55–71) |

| School type | ||

| Government | 51 (48–53) | 51 (43–60) |

| Catholic | 30 (27–32) | 30 (23–39) |

| Independent | 20 (18–22) | 19 (13–26) |

| Parental divorce/separation | ||

| No | 80 (78–82) | 73 (65–80) |

| Yes | 20 (18–22) | 27 (20–35) |

| Highest parental education | ||

| Did not complete high school | 32 (29–34) | 34 (26–42) |

| High school/vocational | 34 (32–37) | 35 (28–44) |

| University degree | 34 (32–36) | 31 (23–39) |

| Substance use | ||

| Cigarette smoking | ||

| None | 61 (59–64) | 28 (21–36) |

| One wave | 11 (10–13) | 11 (6–17) |

| Two or more waves | 28 (25–30) | 62 (53–70) |

| Cannabis use | ||

| None | 73 (70–75) | 44 (36–53) |

| One wave | 10 (8–11) | 10 (6–16) |

| Two or more waves | 18 (16–20) | 46 (37–54) |

| Binge drinking | ||

| None | 66 (63–68) | 47 (38–55) |

| One wave | 19 (17–21) | 20 (14–27) |

| Two or more waves | 16 (14–18) | 34 (26–42) |

| Anxiety depression symptoms | ||

| None | 69 (67–72) | 26 (19–34) |

| One wave | 15 (13–17) | 21 (15–29) |

| Two or more waves | 16 (14–18) | 53 (45–62) |

Table 2.

Young adult substance use outcomes by adolescent self-harm in 1627 cohort participants with observations in both the adolescent and young adult phases

| Young adult measure | Mean age 20.7 years (wave 7) | Mean age 24.1 years (wave 8) | Mean age 29.1 years (wave 9) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No adolescent self-harm (n = 1376) | Adolescent self-harm (n = 128) | No adolescent self-harm (n = 1315) | Adolescent self-harm (n = 121) | No adolescent self-harm (n = 1197) | Adolescent self-harm (n = 111) | |

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Licit substance use | ||||||

| Daily cigarette smoking | 27 (24–29) | 53 (44–62) | 27 (24–29) | 44 (35–53) | 20 (18–23) | 36 (28–46) |

| Alcohol heavy bingeing | 15 (13–17) | 23 (17–32) | 17 (15–19) | 23 (16–32) | 10 (9–12) | 16 (10–24) |

| Illicit drug use | ||||||

| Any cannabis use | 56 (53–58) | 80 (72–86) | 31 (29–34) | 45 (37–55) | 22 (19–24) | 39 (30–48) |

| Any amphetamine use | 6 (5–8) | 17 (12–25) | 10 (9–12) | 16 (10–23) | 10 (9–12) | 20 (13–28) |

| Any cocaine use | 3 (2–4) | 5 (2–10) | 8 (6–9) | 15 (10–23) | 8 (7–10) | 12 (7–19) |

| Any ecstasy use | 7 (5–8) | 17 (12–25) | 18 (16–20) | 28 (21–37) | 13 (11–15) | 28 (20–37) |

| Any Illicit drug use | 56 (53–59) | 80 (72–86) | 36 (33–38) | 53 (44–62) | 27 (24–29) | 46 (37–55) |

| Multiple illicit drug use | 9 (8–11) | 23 (16–31) | 17 (15–19) | 26 (19–35) | 14 (13–17) | 30 (22–39) |

| Dependence Syndrome | ||||||

| Nicotine dependence | 6 (5–7) | 21 (15–29) | 8 (7–10) | 18 (12–26) | 7 (6–9) | 18 (12–26) |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 16 (14–18) | 27 (20–36) | 18 (16–20) | 28 (21–37) | 12 (10–14) | 15 (10–23) |

| Cannabis dependence | 6 (5–8) | 16 (11–24) | 6 (5–7) | 13 (8–21) | 3 (2–4) | 11 (6–18) |

| Any dependence syndrome | 24 (22–26) | 48 (39–56) | 26 (24–29) | 44 (35–53) | 19 (17–21) | 34 (26–44) |

| Multiple dependence syndromes | 4 (3–5) | 16 (10–23) | 5 (4–7) | 15 (10–23) | 3 (2–4) | 9 (5–16) |

Results

The main analysis in this paper is based on data provided by 1627 participants (80% of the intended sample) who had at least one complete wave of data in adolescence and adulthood and complete parental data. Of these participants, in the adolescent phase (waves 3–6), 4%, 6%, 16% and 74% had 1, 2, 3 and 4 complete waves of data, respectively, and in the adult phase (waves 7–9) 10%, 19% and 70% had 1, 2 and 3 waves of complete data.

In the analysis dataset, 876 (54%) were female, 826 (51%) attended a government school, 484 (30%) a Catholic school and 317 (19%) an independent school. By completion of the adolescent follow-up, 338 (21%) had parents who were divorced or separated, 519 (32%) had parents who had not completed high school, 561 (34%) had parents who had completed high school or a vocational qualification and 547 (34%) had parents who had a university degree.

During adolescence, 101 (6%) reported multiple substance use (i.e. cigarette smoking, cannabis use and binge drinking) at two or more waves of follow-up, 123 (8%) reported multiple substance use at one wave and 1404 (86%) did not report multiple substance use at any wave. One hundred and thirty-three (8%) reported self-harm during adolescence (waves 3–6), of whom 84 (63%) were female. In adolescence, 705 (43%) participants did not report substance use (cigarettes, cannabis or binge drinking), with 27 (4%) of these reporting self-harm. In contrast, 922 (57%) reported substance use during adolescence, of whom 106 (11%) also reported self-harm (odds ratio (OR) for the association between substance use and self-harm in adolescence: 3.3, 95% CI 2.1–5.0). Seventy-three (69%) of the adolescent self-harmers who reported substance use were female. Table1 summarizes demographic characteristic and summary adolescent substance use and anxiety and depression symptoms by adolescent self-harm.

The proportion of adolescents using substances (cigarette smoking, cannabis use and binge drinking) over two or more waves of follow-up was greater amongst those reporting self-harm compared with those not reporting self-harm. In addition, compared with those not reporting self-harm, a greater proportion of adolescent self-harmers reported experiencing symptoms of anxiety and depression over two or more waves of follow-up.

The proportion of participants reporting substance use in each young adult wave by adolescent self-harm status is shown in Table2. Across all three adult waves, compared with non-self-harmers, adolescent self-harmers reported significantly increased prevalence of daily cigarette smoking, nicotine dependence, cannabis use, cannabis dependence, ecstasy use, any illicit substance use, any substance dependence and multiple dependence syndromes.

Predictive associations between adolescent self-harm and young adult substance use are displayed in Table3. After adjusting for the effects of wave, sex, school type, parental divorce/separation and level of parental education, adolescent self-harm was associated with an elevated risk of licit and illicit substance use/dependence for every category of substance. Adjustment for adolescent anxiety/depression attenuated but did not fully account for these associations, with the exception of cocaine use. Further adjustment for the number of waves of adolescent cigarette, cannabis use and binge drinking substantially reduced all associations. Nevertheless, after adjustment for all measured confounders, including adolescent substance use, the association between adolescent self-harm and the occurrence of multiple dependence syndromes in adulthood remained (full adjusted OR: 2.0; 95% CI: 1.2–3.2).

Table 3.

A series of predictive models examining the association between adolescent self-harm and different adult substance use outcomes with progressive adjustment for possible adolescent confounders or mediators in 1627 cohort participants with observations in both the adolescent and young adult phases

| Young adult outcome (waves 7–9) | Adolescent self-harm exposure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted for wave and sex | Adjusted further for school type, parental divorce and level of education | Further adjusted for adolescent symptoms of anxiety or depression | Further adjusted for adolescent substance use | |

| OR* (95% CI) | OR† (95% CI) | OR‡ (95%CI) | OR§ (95%CI) | |

| Licit substance use | ||||

| Daily cigarette smoking | 2.4 (1.8–3.4) | 2.4 (1.7–3.3) | 1.9 (1.4–2.7) | 1.1 (0.76–1.6) |

| Alcohol heavy bingeing | 1.6 (1.2–2.3) | 1.6 (1.2–2.3) | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 1.2 (0.87–1.7) |

| Illicit drug use | ||||

| Any cannabis use | 2.4 (1.8–3.3) | 2.3 (1.7–3.2) | 2.1 (1.5–2.9) | 1.2 (0.88–1.7) |

| Any amphetamine use | 2.3 (1.6–3.3) | 2.2 (1.5–3.3) | 1.9 (1.2–2.8) | 1.1 (0.76–1.7) |

| Any cocaine use | 1.8 (1.2–2.8) | 1.8 (1.2–2.8) | 1.5 (0.96–2.5) | 0.93 (0.57–1.5) |

| Any ecstasy use | 2.4 (1.7–3.3) | 2.4 (1.7–3.4) | 2.1 (1.4–3.0) | 1.3 (0.90–1.9) |

| Any Illicit drug use | 2.5 (1.8–3.5) | 2.5 (1.8–3.4) | 2.2 (1.6–3.1) | 1.3 (0.91–1.8) |

| Multiple illicit drug use | 2.4 (1.7–3.4) | 2.4 (1.7–3.4) | 2.0 (1.4–3.0) | 1.2 (0.85–1.8) |

| Syndrome | ||||

| Nicotine dependence | 3.3 (2.2–4.9) | 3.2 (2.1–4.7) | 2.2 (1.4–3.4) | 1.4 (0.91–2.3) |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 1.9 (1.4–2.6) | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 1.2 (0.86–1.7) |

| Cannabis dependence | 3.3 (2.2–5.1) | 3.2 (2.1–4.9) | 2.5 (1.5–4.0) | 1.5 (0.95–2.4) |

| Any syndrome | 2.7 (2.0–3.6) | 2.6 (1.9–3.5) | 2.0 (1.4–2.7) | 1.3 (0.98–1.8) |

| Multiple syndromes | 4.2 (2.7–6.6) | 4.1 (2.6–6.3) | 3.0 (1.9–4.8) | 2.0 (1.2–3.2) |

Odds ratios from generalized estimating equations with robust standard errors to allow for repeated measures within id and adjusted for wave of observation and sex

Odds ratios from generalized estimating equations with robust standard errors to allow for repeated measures within id and adjusted for wave of observation, sex, school type, parental divorce or separation and highest level of education

Odds ratios from generalized estimating equations with robust standard errors to allow for repeated measures within id and adjusted for wave of observation, sex, school type, parental divorce or separation and highest level of education, and symptoms of anxiety or depression on three levels (none, one wave, 2+ waves) in adolescence

Odds ratios from generalized estimating equations with robust standard errors to allow for repeated measures within id and adjusted for wave of observation, sex, school type, parental divorce or separation and highest level of education, any symptoms of anxiety or depression and binge drinking, smoking and cannabis use (all on three levels: none, one wave, 2+ waves) in adolescence.

Discussion

In this representative cohort of young people, all forms of substance use and dependence were more common through young adulthood in those with an adolescent history of self-harm. By wave 7 (mean age 20.7 years), just under half of those who had engaged in adolescent self-harm met criteria for a dependence syndrome and 1-in-6 met criteria for multiple dependence syndromes. By comparison, only 1-in-25 of adolescents not reporting self-harm, met criteria for multiple dependence syndromes at wave 7. Although a reduction in the prevalence of substance use occurred between waves 7 and 9, the increased risk of substance use associated with adolescent self-harm was maintained throughout the participants' third decade of life. Adjustment for the presence of adolescent symptoms of anxiety or depression attenuated, but did not eliminate the associations between adolescent self-harm and illicit drug use and dependence in adulthood. The majority of associations were heavily confounded by adolescent substance use, confirming that an intimate link between self-harm and substance use had already been established in adolescence. Notwithstanding, adolescent self-harm was independently associated with multiple forms of dependence syndrome.

We have recently shown that a substantial reduction in reported self-harm occurs as teenagers age 5. Yet, these additional findings suggest that cessation of self-harming behaviour in late adolescence may be accompanied by a continuing use of multiple substances, possibly to regulate the intense emotions associated with this phase of life 7. Adolescents who self-harm are more likely to employ avoidant coping strategies and are less able to solve problems effectively 20, thus increasing the risk of an on-going reliance on substances as they grow older 21. To understand this link, the presence of common underlying biopsychosocial risk factors predisposing individuals to both teenage self-harm and later substance use needs to be considered. Such factors may operate at the level of the individual (e.g. impulsive personality traits), household (e.g. family conflict), or community level (e.g. the social transmission of behavioural problems amongst peers). Substance use and self-harm both often commonly occur in response to negative affect 22,23. One possibility is that the endogenous opioid system, also implicated in addiction, may be activated by self-harm 24. It is therefore also possible that adolescent self-harm and substance abuse share an underlying biological pathway. However, the causal pathway responsible for these findings falls outside the scope of our study and requires further research.

Problematic substance use is a well-established correlate of both self-harm 12 and suicide 25, but the longitudinal relationship between adolescent self-harm and later heavy and dependent substance use has not been previously described. A study of a New Zealand birth-cohort failed to detect an association between suicide attempts prior to age 18 years and substance and alcohol dependence between 18 and 25 years 8. However, suicide attempts only represent a small proportion of the full range of self-harming behaviour 26. Our representative sample, high rates of participation and multiple waves of follow-up over a time period spanning from middle adolescence to the late 20s, are strengths of this study. Indeed, the changes in levels of substance use which occurred between waves 7 and wave 9 are consistent with other epidemiological data on illicit drug use in Australia 27,28. However, the findings need to be considered in the light of certain methodological issues. Non-response in longitudinal studies tends to be associated with drug use and this may have affected our findings. We used a broad definition of self-harm that encompassed behaviours with and without suicidal intention. We adopted this definition, because there is a substantial overlap between suicidal and non-suicidal self-harm 29 and behavioural intention with respect to suicide is changeable 30. Finally, all data on self-harm and substance use were based on self-report measures, with no external validation of these measures. However, other research indicates that individuals' self-reports of drug use and self-harm in surveys of this type are both reliable and valid 13,31.

The public health focus of self-harm research has until recently been on the association with suicide 32. Whilst this focus is clearly important, it has perhaps overshadowed the need to address other health risks in young people who self-harm. Although most adolescent self-harming behaviour appears to resolve spontaneously 5, our findings indicate that young people who self-harm are at substantial risk of heavy and dependent substance use in their third decade of life. This level of substance misuse is likely to contribute substantially to the premature mortality and disease burden experienced by individuals who self-harm 33. Adolescents who self-harm may benefit from ongoing clinical and social support as they make the transition to adulthood. Dialectical Behaviour Therapy 34, Mentalization-based Therapy 35 and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy 36 are all promising interventions for adolescents who self-harm, although more evidence is needed around their longer term effectiveness. Further interventions targeting substance use, seem warranted 37, even when a young person's self-harm has started to resolve.

Authors contributions

GP and PM conceived the study and developed the analysis plan with CC and HR. Data were analysed by CC and HR. PM led the writing of the paper and CC, HR, LD, RB and GP contributed to drafts of the paper. PM guarantees the paper and is the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Professor Keith Hawton for helpful comments made on an earlier draft of this paper. PM is part-funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Declaration of interest

PM runs an NHS service for adults who self-harm and is also the grant holder on a self-harm intervention study funded by Guys' & St Thomas' Charity (grant number: MAJ120701). The other authors have no conflict of interests to declare, either in relation to this study, or more generally. Data collection for this study was supported by NHMRC Australia.

References

- Madge N, Hewitt A, Hawton K, et al. Deliberate self-harm within an international community sample of young people: comparative findings from the Child & Adolescent Self-harm in Europe (CASE) Study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:667–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J, Kapur N, Webb R, et al. Suicide after deliberate self-harm: a 4-year cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:297–303. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large M, Smith G, Sharma S, Nielssen O, Singh SP. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical factors associated with the suicide of psychiatric in-patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:18–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner R, Parzer P, Haffner J, et al. Prevalence and psychological correlates of occasional and repetitive deliberate self-harm in adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:641–649. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran P, Coffey C, Romaniuk H, et al. The natural history of self-harm from adolescence to young adulthood: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2012;379:236–243. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldershaw A, Grima E, Jollant F, et al. Decision making and problem solving in adolescents who deliberately self-harm. Psychol Med. 2009;39:95–104. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone EA, Dahl RE. Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:636–650. doi: 10.1038/nrn3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM, Beautrais AL. Suicidal behaviour in adolescence and subsequent mental health outcomes in young adulthood. Psychol Med. 2005;35:983–993. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704004167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohm FA, Striegel-Moore RH, Wilfley DE, Pike KM, Hook J, Fairburn CG. Self-harm and substance use in a community sample of Black and White women with binge eating disorder or bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32:389–400. doi: 10.1002/eat.10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiniuk AL, Ivers RQ, Glozier N, et al. Self-harm and risk of motor vehicle crashes among young drivers: findings from the DRIVE Study. CMAJ. 2009;181:807–812. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossow I, Hawton K, Ystgaard M. Cannabis use and deliberate self-harm in adolescence: a comparative analysis of associations in England and Norway. Arch Suicide Res. 2009;13:340–348. doi: 10.1080/13811110903266475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossow I, Ystgaard M, Hawton K, et al. Cross-national comparisons of the association between alcohol consumption and deliberate self-harm in adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37:605–615. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.6.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Rodham K, Evans E, Weatherall R. Deliberate self harm in adolescents: self report survey in schools in England. BMJ. 2002;325:1207–1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya R, Dunn G. Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: a standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med. 1992;22:465–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian alcohol guidelines: health risk and benefits. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom KO, Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT. Nicotine addiction and its assessment. Ear Nose Throat J. 1990;69:763–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston M, Laslett AM, Dietze P. Individual and community correlates of young people's high-risk drinking in Victoria, Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;98:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Composite international diagnostic interview CIDI-Auto 2.1 administrator's guide and reference. Geneva: WHO; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe C, Corcoran P, Keeley HS, et al. Problem-solving ability and repetition of deliberate self-harm: a multicentre study. Psychol Med. 2006;36:45–55. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee WB, D'zurilla TJ. Personality, problem solving, and adolescent substance use. Behav Ther. 2009;40:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boys A, Marsden J, Strang J. Understanding reasons for drug use amongst young people: a functional perspective. Health Educ Res. 2001;16:457–469. doi: 10.1093/her/16.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED. The functions of deliberate self-injury: a review of the evidence. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:226–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresin K, Gordon KH. Endogenous opioids and nonsuicidal self-injury: a mechanism of affect regulation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:374–383. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Fagg J, Platt S, Hawkins M. Factors associated with suicide after parasuicide in young people. BMJ. 1993;306:1641–1644. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6893.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Saunders KE, O'connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012;379:2373–2382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teesson M, Hall W, Lynskey M, Degenhardt L. Alcohol- and drug-use disorders in Australia: implications of the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34:206–213. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teesson M, Hall W, Slade T, et al. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in Australia: findings of the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Addiction. 2010;105:2085–2094. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur N, Cooper J, O'connor RC, Hawton K. Non-suicidal self-injury v. attempted suicide: new diagnosis or false dichotomy? Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:326–328. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.116111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter D, Platt S. Suicidal intent, hopelessness and depression in a parasuicide population: the influence of social desirability and elapsed time. Br J Clin Psychol. 1990;29(Pt 4):361–371. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1990.tb00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S. Self-report among injecting drug users: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahl DL, Hawton K. Repetition of deliberate self-harm and subsequent suicide risk: long-term follow-up study of 11,583 patients. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:70–75. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen H, Hawton K, Waters K, et al. Premature death after self-harm: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:1568–1574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathus JH, Miller AL. Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32:146–157. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.2.146.24399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw TI, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment for self-harm in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:1304–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Greenhill LL, Compton S, et al. The Treatment of Adolescent Suicide Attempters study (TASA): predictors of suicidal events in an open treatment trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:987–996. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5dbe4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley MD, Godley SH, Dennis ML, Funk RR, Passetti LL, Petry NM. A randomized trial of assertive continuing care and contingency management for adolescents with substance use disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:40–51. doi: 10.1037/a0035264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]