Abstract

Aims

The activation of immune cells must be tightly regulated to allow an effective immune defense while limiting collateral damage to host tissues. Cellular ATP release and autocrine stimulation of purinergic receptors are recognized as critical regulators of immune cell activation. However, the study of purinergic signaling has been hampered by the short half-life of the released ATP and its breakdown products as well as the lack of real-time imaging methods to study spatiotemporal dynamics of ATP release.

Methods

To overcome these limitations, we optimized imaging methods that allow monitoring of ATP release with conventional microscopy using the recently developed small molecular ATP probes 1-2Zn(II) and 2-2Zn(II) for imaging of ATP in the extracellular space and release at the surface of living cells.

Results

1-2Zn(II) allowed imaging of <1 µM ATP in the extracellular space, while 2-2Zn(II) provided unprecedented insights into the spatiotemporal dynamics of ATP release from neutrophils and T cells. Stimulation of these cells caused virtually instantaneous ATP release, which was followed by a second phase of ATP release that was localized to the immune synapse of T cells and the leading edge of polarized neutrophils. Imaging these ATP signaling processes along with mitochondrial probes provided evidence for a close spatial relationship between mitochondrial activation and localized ATP release in T cells and neutrophils.

Conclusion

We believe that these novel live cell imaging methods can be used to define the roles of purinergic signaling in immune cell activation and in the regulation of other complex physiological processes.

Keywords: ATP release, live cell imaging, fluorescence microscopy, autocrine purinergic signaling, neutrophils, T cells

Introduction

Living cells release adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in response to mechanical and chemical stimulation. Extracellular ATP can act as an autocrine and paracrine signaling molecule that plays an important role in many physiological phenomena including neurotransmission, mucociliary clearance, and the regulation of cellular immune responses (Burnstock 2007, Lazarowski et al. 2009, Junger 2007, 2011). Like all other mammalian cell types studied to date, immune cells such as the polymorphonuclear neutrophils and T lymphocytes (T cells) can respond to extracellular ATP via purinergic receptors on their cell surface. We previously reported that inside-out signaling via ATP release and autocrine stimulation of such purinergic receptors represents a novel mechanism of immune cell regulation (Chen et al. 2006, Yip et al. 2009). A growing body of evidence indicates that purinergic signaling has a central role in regulating neutrophil chemotaxis, T cell activation, NALP inflammasome activation, and IL-1 production in the course of inflammatory responses (Junger 2011, Chen et al. 2006, Yip et al. 2009, Di Virgilio 2007, Trautmann 2009, Bao et al. 2013, Kronlage et al. 2010). While ATP can be released by exocytosis and pannexin 1 (panx1) channels, it seems likely that other transport mechanisms may also be involved.

Extracellular ATP binds to ionotropic P2X or metabotropic P2Y receptors; ATP can also be degraded by ectonucleotidases that are found on the cell surface of virtually all mammalian cells. This results in the formation of adenosine diphosphate (ADP), adenosine monophosphate (AMP), and adenosine, which in turn can bind to several P2Y and P1 adenosine receptor subtypes that belong to the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily (Khakh & North 2006, Corriden & Insel 2010). The nineteen different P1 and P2 purinergic receptor subtypes that have been characterized in mammalian cells can trigger a diverse set of downstream signaling cascades that allow them to regulate complex functional cell responses including cell motility, changes in cell morphology, and gene expression (Junger 2007, Junger 2011, Khakh & North 2006, Corriden & Insel 2010).

Currently available imaging techniques are not suitable for the investigation of the rapid dynamics of ATP release from living cells. Although luciferin/luciferase-based chemiluminescence and high performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) methods can be used to measure ATP released into bulk cell culture supernatants, these methods cannot provide the necessary spatiotemporal information about ATP release that is needed to fully understand the complex roles of purinergic signaling in cell regulation (Loomis et al. 2003). In attempts to overcome these limitations, membrane bound firefly luciferase assays have been developed (Beigi et al. 1999, Praetorius & Leipziger 2009, Okada et al. 2006, Pellegatti et al. 2005). While these methods can provide temporal information about the dynamics of ATP release from stimulated cells, they are unsuitable for conventional light microscopy and thus fail to provide the necessary spatial information to study the location of ATP release at the cell surface.

We previously reported a tandem enzyme system to visualize extracellular ATP release from living cells using fluorescence microscopy. This method has allowed us to estimate local extracellular ATP concentrations in association with cell shape changes and cell activation (Corriden et al. 2007). However, because this method requires ultraviolet illumination and the use of reagents that disrupt purinergic signaling mechanisms, it is impractical for long-term observations of purinergic signaling. Therefore, we sought to develop new imaging methods that are less intrusive and thus more suitable for long-term imaging of purinergic signaling. Because ATP release from living cells occurs within seconds of cell stimulation and the resulting extracellular ATP concentrations are typically in the lower micromolar range, probes that detect ATP with rapid response time and a high signal-to-noise ratio are required for reliable detection of purinergic signaling. Here we report novel methods to monitor purinergic signaling based on recently developed small molecular fluorescent ATP probes, 1-2Zn(II) and 2-2Zn(II) that allow real-time imaging of purinergic signaling with conventional fluorescence microscopy (Ojida et al. 2006, 2008, Kurishita et al. 2010, 2012).

Materials and Methods

Cell preparations

All studies with immune cells from healthy human volunteers were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Human neutrophils were prepared as previously described (Junger et al. 1998, Chen et al. 2006). Briefly, neutrophils were isolated from heparinized venous blood of healthy volunteers using dextran sedimentation followed by Percoll gradient centrifugation. Neutrophils were kept in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS). Cell preparations were kept pyrogen-free and osmotic or excessive mechanical stimulation was carefully avoided. The human T cell line Jurkat (clone E6-1) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Jurkat cells were suspended in RPMI-1640 medium (ATCC) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Gibco) and maintained at 37°C and in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Materials

Carbenoxolone (CBX), carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP), potassium cyanide (KCN), EGTA, N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP), and all other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. Percoll was from Pharmacia (Piscataway, NJ). The soluble ATP probe 1-2Zn(II) and the membrane-targeting ATP probe 2-2Zn(II) were a generous gift of Drs. Kurishita and Hamachi (Kyoto University).

Preparation of beads

Dynabeads (Dynal Inc., Lake Success, NY) were coated with mouse anti-human CD3 and mouse anti-human CD28 antibodies. The manufacturer supplied the beads pre-coated with anti-mouse IgG. These beads were incubated on a shaker at room temperature for 1 h with the anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies mentioned above using 1 µg of each antibody for 4×106 beads. Then the beads were washed twice with HBSS and resuspended at 107 beads/ml. A small aliquot of beads was pipetted into the cell suspension on the microscope stage.

Real-time monitoring of ATP release with the soluble ATP probe 1-2Zn(II)

For imaging of extracellular ATP in medium, cells were placed into 35-mm (MatTek, Ashland, MA) or 8-well glass bottom dishes (Lab-Tek, Rochester, NY) coated for 30 min at room temperature with 40 µg/ml of human fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Since we found that binding of 1-2Zn(II) to polyphosphates was affected by phosphate containing solutions, we carried out our cell experiments in Ringer’s solution (Baxter, Deerfield, IL; Lactated Ringer’s injection grade; composition: 130 mM Na+, 4 mM K+, 2.7 mM Ca2+, 109 mM Cl−, 28 mM lactate; osmolarity, 273 mOsmol/l; pH 7.4). After attachment of cells, the supernatant was exchanged with fresh Ringer’s solution containing 10 µM of the probe 1-2Zn(II). Imaging was done with an inverted Leica DMIRB microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a PSMI-2 stage incubator controlled by a TC-202A temperature controller (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) and a Hamamatsu Orca II camera (Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan) or with a Leica DMI 6000B microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a Spot Boost EMCCD camera (Diagnostic Instruments Inc., Sterling Heights, MI). Fluorescence images were taken through a Leica 100× PL Fluotar oil-immersion objective with a nominal aperture (NA) of 1.30. We used a filter set consisting of a 504-nm band-pass exciter with 12-nm bandwidth, a 550-nm band pass emitter with a 49-nm band width, and a 514-nm dichroic beam splitter (Semrock, Rochester, NY) or a YFP-2427A filter set (exciter 500/24 nm, emitter 542/27 nm, dichroic 520 nm; Semrock, Rochester, NY). In some cases we performed confocal microscopy with a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta live cell confocal system. In order to image 1-2Zn(II) or 2-2Zn(II) fluorescence, a 488-nm laser, a 490-nm dichroic beam splitter, and a 505-nm long-pass emission filter provided adequate results. Openlab software (Improvision, Coventry, UK) or µManager software developed in Ron Vale's laboratory at UCSF with funding from the National Institutes of Health, NIH grant R01-EB007187 was used to control the cameras, stages, and to capture images; ImageJ software (NIH) was used to analyze images. ATP concentrations were estimated by comparison of fluorescence signals obtained with standard solutions containing known concentrations (1–100 µM) of ATP.

Real-time monitoring of ATP release with a membrane-bound ATP probe 2-2Zn(II)

For real-time imaging of ATP release on the cell surface, cells were placed in microscope dishes as described above. After attachment of cells to the glass, cells were washed and the supernatant replaced with fresh HBSS containing 500 nM of the membrane-targeting probe 2-2Zn(II). Cells were incubated with this probe on the microscope stage for 5 min at 37°C and fluorescence live-cell imaging was performed with the inverted microscope systems described above. In contrast to 1-2Zn(II), the membrane targeting probe 2-2Zn(II) tolerated phosphate in HBSS, perhaps because of the unique ionic composition in the microenvironment found near the cell surface. We found that it is not advisable to wash cells after they have been stained with 2-2Zn(II) because the presence of 2-2Zn(II) in the culture medium seems to be necessary to replenish probe that is lost over time, for example as a result of membrane internalization. In some experiments, a chemotactic gradient with fMLP was generated to study neutrophil chemotaxis. For that purpose, an Eppendorf system consisting of a FemptoJet and an InjectMan with micropipettes loaded with 100 nM fMLP was used as described previously (Chen et al. 2006). Imaging was done with the microscope systems described above. For simultaneous monitoring of ATP release and mitochondrial localization or activity, cells were loaded with MitoTracker Red CM-H2XRos (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and stained with 2-2Zn(II) as described above. Red fluorescence images were recorded with a Texas Red filter set (Semrock; Bright Line FF593).

Fluorescence spectroscopy

The fluorescence properties of 1-2Zn(II) and 2-2Zn(II) were measured with a Hitachi F-4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Pleasanton, CA). Three-dimensional (3D) spectral images were generated using Excel software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Useful hints

It is critical to perform all experiments in a manner to minimize mechanical perturbations of cells, which would cause significant ATP release and result in a high background signal that interferes with the detection of cellular ATP release. Similar to mechanical stimulation, drastic or frequent changes in temperature must also be avoided to limit unintended ATP release and cell stress. Imaging of cell cultures with large numbers of apoptotic, dying, or damaged cells poses a particularly difficult problem because of excessive ATP in the culture supernatant. This problem can be best addressed by using freshly isolated or cultured cells whenever possible and by replacing the culture medium with fresh medium just prior to live cell imaging. In order to minimize mechanically induced ATP release, we found it necessary to maintain cells on a vibration isolation table (e.g., 63–500 Series Micro-g® Lab Table; TMC, Peabody, MA) for at least 30 min prior to and during live cell imaging. The importance of devices that reduce vibrations may vary from building to building and from cell type to cell type. However, in our experience, vibration isolation has been an indispensable requirement to accurately assess ATP release from neutrophils and T cells using microscope-based and other methods.

As described in more detail in the discussion section, we found that the ATP binding ability of the sensor structure in 1-2Zn(II) and 2-2Zn(II) was significantly impacted by various conditions and components that can be often found in cell culture media, including but not limited to phosphate, pH values <6, hypertonic conditions (i.e., >20 mM NaCl in excess of isotonicity), and bovine serum albumin. Therefore, the effect of tissue culture media components must be tested. We also observed that 2-2Zn(II) staining of some cell types (Jurkat T cells) increased their sensitivity to phototoxicity during live-cell imaging. Reducing loading concentrations and illumination intensity helped reduce this problem.

Results

Detection of ATP release from neutrophils with a novel fluorescence probe

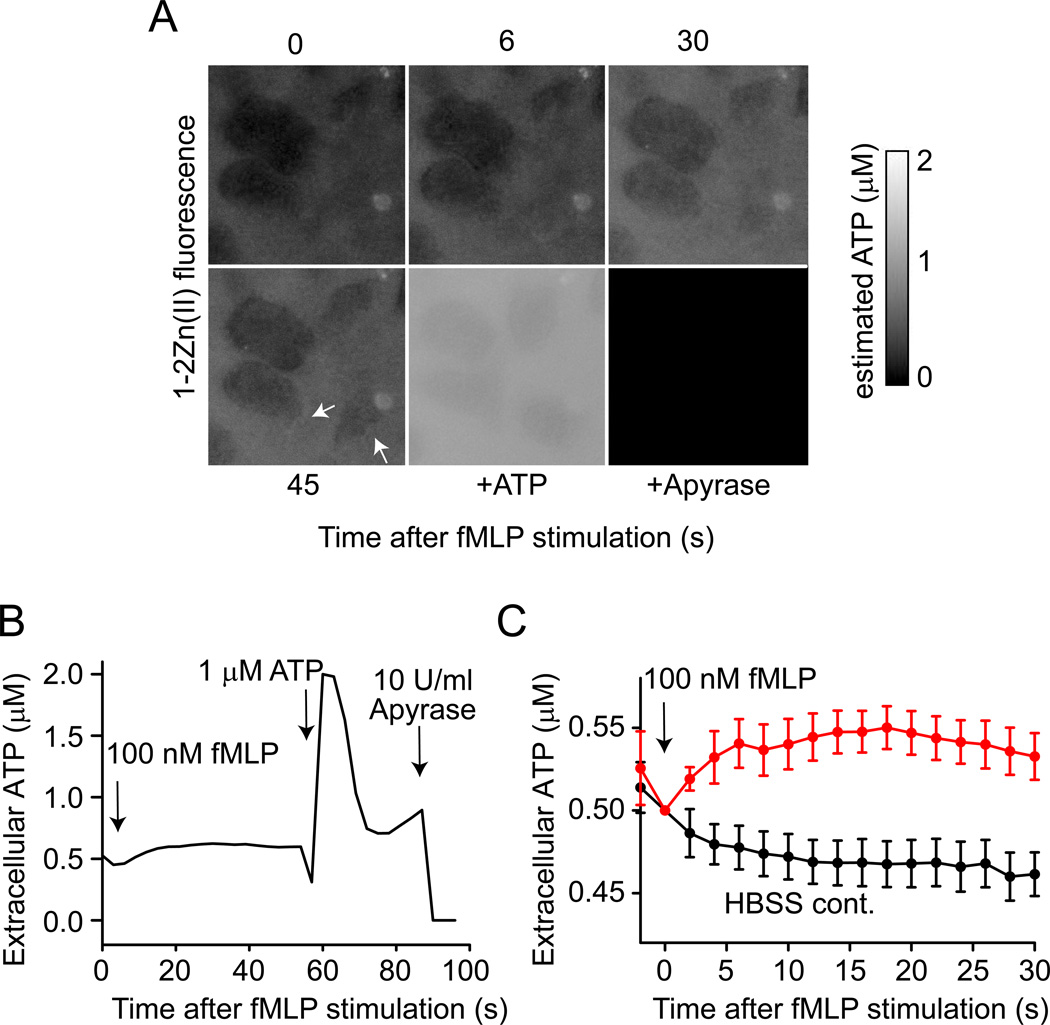

Using a tandem enzyme ATP detection system, we have previously shown that ATP release regulates the polarization and chemotaxis of neutrophils in response to chemotactic stimuli (Chen et al. 2006). However, real-time observation of these purinergic signaling processes was hampered by the intrusive nature and phototoxicity of the tandem enzyme ATP detection system. Therefore, we set out to develop new approaches to detect ATP release using a less intrusive method. For that purpose, Dr. Hamachi from Kyoto University kindly provided us with a novel turn-on type fluorescent probe, designated 1-2Zn(II), that was synthesized in his laboratory (Okada et al. 2006). This probe emits a fluorescence signal when bound to ATP or other nucleotide di- and triphosphate compounds at a peak excitation wavelength of 505 nm and emission wavelength of 535 nm (Fig. 1). The lower detection limit for ATP of this probe is <1 µM, which makes it suitable for monitoring of ATP release from stimulated neutrophils. Live cell imaging using a Leica DMI 6000B microscope with a Semrock YFP-2427A filter set (exciter 500/24 nm, emitter 542/27 nm, dichroic 520 nm) showed that stimulation of purified human neutrophils with the chemotactic peptide fMLP causes a rapid increase in 1-2Zn(II) fluorescence in the extracellular space, reaching highest fluorescence intensity levels ~30 s after cell stimulation (Fig. 2; video 1). As reported before with the tandem enzyme ATP detection method mentioned above (Chen et al. 2006), we found highest levels of 1-2Zn(II) fluorescence near cell surface regions with active membrane deformation (video 1 and arrow in Fig. 2A). This finding suggests that membrane deformation is associated with ATP release and that the released ATP stimulates nearby P2Y2 receptors we have previously shown to contribute to the regulation of cell motility and chemotaxis (Chen et al. 2006, 2010). Fluorescence signals obtained with ATP standard solutions were used to estimate extracellular ATP concentrations. We calculated that baseline ATP concentrations of unstimulated neutrophils were ~0.5 µM and that fMLP stimulation increased these levels by ~50 nM (Fig. 2B&C). However, it is important to consider that the structural design of 1-2Zn(II) interacts with all polyphosphates including ATP, ADP, PPi but also UTP, and UDP. Thus, the actual ATP concentrations in Fig. 2B may be considerably lower than 0.5 µM. In fact, high performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) analysis revealed a baseline ATP concentration of 80 nM in the bulk supernatant of unstimulated purified human neutrophils (Bao et al. 2014). In contrast to the 1-2Zn(II) and 2-2Zn(II) probes described here, HPLC can distinguish between UTP, ATP, and their corresponding breakdown products and analysis of T cell and neutrophil contents with HPLC has shown that both cell types contain negligible amounts of UTP when compared to ATP. Therefore, it is unlikely that UTP or UDP contributed to the signal we observed with the fluorescence probes described in this study. However, possible contributions of UTP, UDP, or other nucleotide polyphosphates should be tested for each cell systems.

Figure 1. Properties of the ATP sensor 1-2Zn(II).

(A) The fluorescence properties in arbitrary units (a.u.) of 1-2Zn(II) (10 µM) in the absence (left) or presence (right) of 100 µM ATP were studied using a fluorescence spectrophotometer. Three-dimensional spectral scanning was used to characterize excitation and emission spectra. (B) ATP concentration dependency. The emission profile of 1-2Zn(II) (10 µM) was assessed in the presence of increasing ATP concentrations (0.01 µM – 100 µM). Excitation was at 505 nm (Ex 505 nm). Inset: fluorescence intensity in the presence of different ATP concentrations; excitation and emission wavelengths were 505 nm and 550 nm, respectively.

Figure 2. Visualization of ATP release into the supernatant using 1-2Zn(II) and fluorescence microscopy.

(A) Freshly isolated human neutrophils were incubated with 1-2Zn(II) probe (10 µM), stimulated with fMLP (100 nM), and fluorescence changes were recorded for 45 s (see also video 1). ATP (1 µM) was added as a positive control, followed by apyrase (10 U/ml) that hydrolyzes extracellular ATP, ADP, and PPi and served as a negative control. The arrows indicate sites of ATP release from actively moving membrane regions. (B) Estimated concentration of the extracellular ATP in (A) based on fluorescence signals obtained with ATP standard solutions. Grey values were analyzed with ImageJ software. (C) fMLP induced extracellular ATP release into medium. Neutrophils were incubated with 1-2Zn(II) probe (10 µM), stimulated with fMLP (100 nM) or HBSS, and fluorescence changes were recorded. Estimated concentration of the extracellular ATP was calculated from 5 independent experiments. Data present mean ± SD.

A novel membrane targeting ATP probe reveals complex dynamics of ATP release

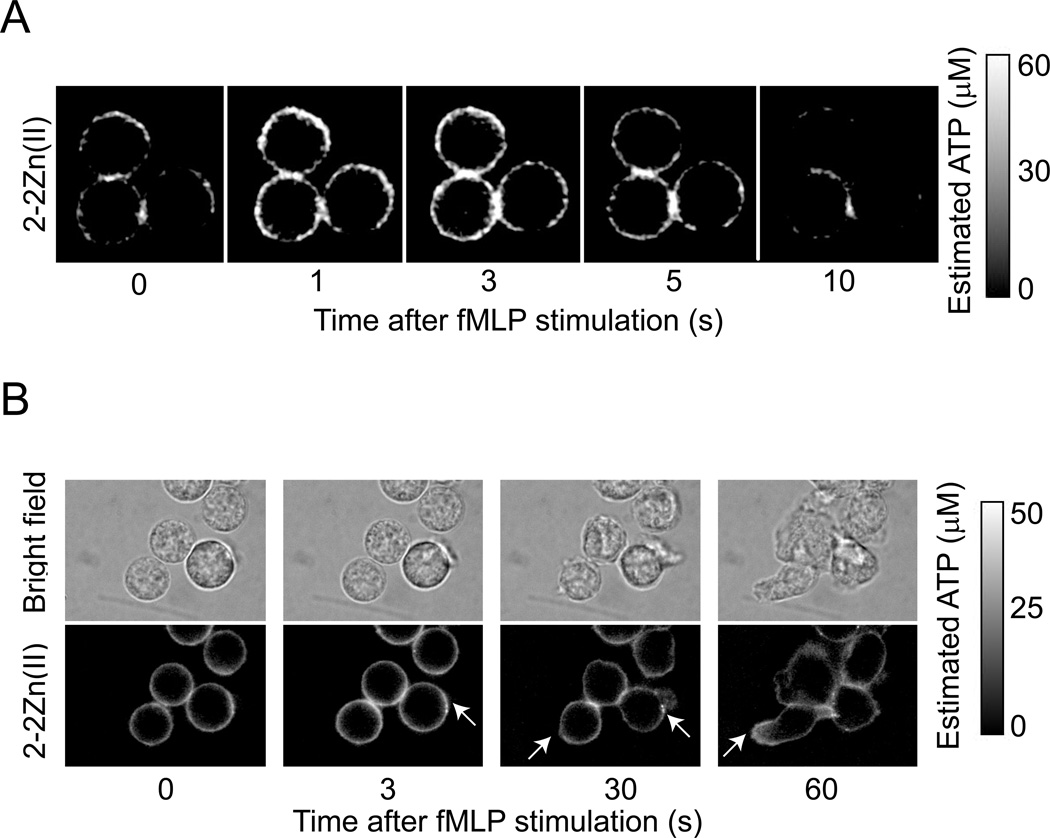

Detection of 1-2Zn(II) fluorescence suggested that activated neutrophils release ATP from specific, localized regions of their cell membrane. However, in order to study the spatiotemporal dynamics of ATP release in more detail, we developed a live cell imaging method based on the membrane targeting ATP probe termed 2-2Zn(II) that was also generated in the laboratory of Dr. Hamachi by his former PhD student Dr. Kurishita. The sensor structure of this probe is identical to that of 1-2Zn(II) but 2-2Zn(II) has a polyethylene glycol linker that covalently connects the senor to a lipid residue, which facilitates binding of 2-2Zn(II) to the cell surface of living cells (Kurishita et al. 2012). Using this probe, we found that stimulation of neutrophils with fMLP induced a rapid burst of ATP release that occurred ≤1 s after the addition of fMLP (Fig. 3A, video 2). In this initial burst of ATP release, we found localized hotspots of ATP release distributed across the entire cell surface, which was followed by a decrease in ATP release to pre-stimulation baseline levels within 10 s after fMLP addition. This phase was followed by cell polarization that involves the protrusion of pseudopods and formation of elongated cell shapes. This phase was characterized by localized 2-2Zn(II) fluorescence associated primarily with regions of active pseudopod protrusion and cell-to-cell interactions (Fig. 3B, video 3).

Figure 3. Visualization of localized ATP release from neutrophils using the membrane-bound ATP probe 2-2Zn(II) and fluorescence microscopy.

(A) Neutrophils were purified, allowed to attach to the cover glass of a microscope dish, and incubated on the microscope stage for 5 min with 500 nM 2-2Zn(II) in HBSS. Cells were stimulated with fMLP (10 nM) and fluorescence changes of 2-2Zn(II) were recorded in 1-s intervals using a fluorescence microscope (see also video 2). (B) Subsequent ATP release during neutrophil polarization and migration was assessed with 2-2Zn(II) as described above, except that imaging was done at slower frame rates. Arrows indicate sites of ATP release during cell polarization and pseudopod protrusion (see also video 3). Data are representative of at least 3 separate experiments with similar results.

Simultaneous monitoring of ATP release and mitochondrial activity in neutrophils

The 2-2Zn(II) imaging method described above in combination with the measurement of intracellular Ca2+ signaling using fluorescent probes such as Fluo-4 has recently allowed us to identify complex interactions of purinergic and Ca2+ signaling networks that regulate neutrophil activation and subsequent functional cell responses (Bao et al. 2014). We found that an initial phase of Ca2+ signaling triggers a burst of ATP release. This is required for the activation of mitochondrial ATP production that drives a secondary round of purinergic signaling and Ca2+ influx that is essential for neutrophil activation. Multichannel fluorescence imaging with 2-2Zn(II) and various fluorescent mitochondrial probes has provided unprecedented insight in these complex activation mechanisms. For example, simultaneous monitoring of 2-2Zn(II) and MitoTracker Red CM-H2XRos, which allows imaging of mitochondrial activity, has revealed that mitochondria contribute to ATP release during polarization and the formation of pseudopods following neutrophil activation with chemotactic mediators (Fig. 4, video 4).

Figure 4. Imaging of ATP release and mitochondrial activity.

(A) To assess mitochondrial activity, human neutrophils were stained with MitoTracker Red CM-H2XRos according to the manufacturer’s instructions and ATP release was assessed with 2-2Zn(II) as described above. Cells were stimulated with fMLP (10 nM) and green and red fluorescence image sets were acquired over time using a confocal laser scanning microscope. (B) Local changes in mitochondrial activation (red) and ATP release (green) were studied with ImageJ software and differences in fluorescence intensity in region of interest (ROI) 1 and 2 were recorded over time (see also video 4). Data are representative of at least 15 cells in 3 separate experiments.

T cells release ATP primarily at the immune synapse

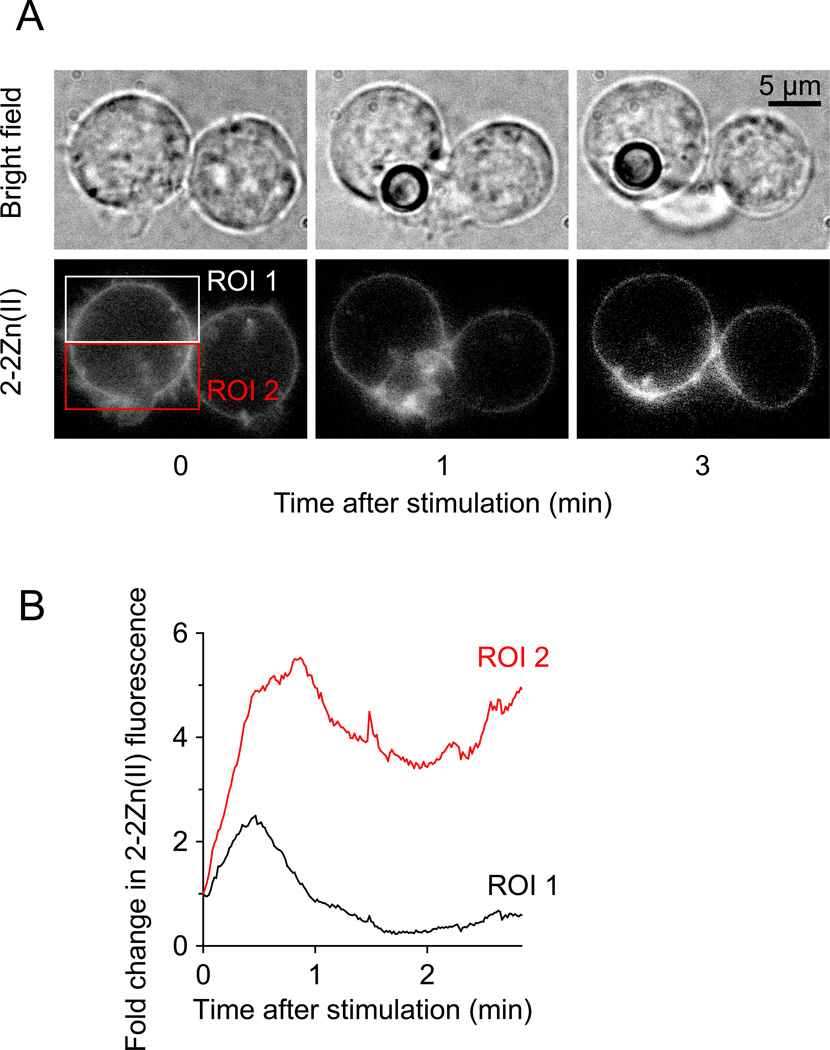

Stimulated T cells form an immune synapse with antigen-presenting cells, which allows T cells to communicate with antigen presenting cells, process antigens, and calibrate subsequent functional responses of T cells based on the information they receive at the immune synapse. ATP release and autocrine purinergic signaling play important roles in T cell activation (Junger 2011, Yip et al. 2009, Yegutkin et al. 2006, Schenk et al. 2008). The membrane anchoring probe 2-2Zn(II) has allowed us to further define the purinergic signaling events that regulate T cell activation (Ledderose et al. 2014). T cells were stained with 2-2Zn(II) and beads carrying antibodies to the T cell receptor (TCR) and CD28 co-receptor were added to mimic T cell interactions with antigen presenting cells. Imaging with 2-2Zn(II) revealed that ATP release from T cells is a highly dynamic process that involves an initial recognition phase that seems to allow cells to recognize and associate with the beads (Fig. 5A–C, videos 5 & 6). During this phase, ATP release from unstimulated T cells occurred randomly across the cell surface, but primarily at hotspots associated with filopodia (video 6). Upon detection of a bead, the randomly distributed hotspots of ATP release reorganized and began to colocalize at the immune synapse (Fig. 5B&C), where ATP release gradually intensified during the formation of stable interactions with the beads (Fig. 6, video 6). This localized increase in fluorescence signal was not seen in control experiments with antibody-free beads that do not induce the formation of an immune synapse (Fig. 5D). Our findings suggest that ATP release from T cells can be separated in two different phases: (1) a first phase that seems to facilitate the initial interaction with antigen resenting cells, and (2) a second phase that seems to be dedicated to autocrine/paracrine purinergic signaling at the synapse (Fig. 6B).

Figure 5. Stimulated T cells release ATP at the immune synapse.

(A) Jurkat T cells were stained with 2-2Zn(II) and uniform 2-2Zn(II) dye distribution across the cell surface was verified by adding 100 µM ATP. (B) Jurkat T cells stained with 2-2Zn(II) were stimulated with beads carrying anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies and ATP release was visualized with fluorescence microscopy before and after the addition of beads, ATP (not depicted), and apyrase (20 U/ml) to remove extracellular ATP (see also video 5). (C) Anti-CD3/CD28 antibody coated beads were added to Jurkat cells stained with 2-2Zn(II) and ATP release and immune synapse formation were monitored with two channel (fluorescence and bright field) imaging. (D) Antibody free control beads were added to Jurkat cells stained with 2-2Zn(II) and ATP release was imaged; scale bars, 5 µm; images are representative of n≥5 separate experiments and n≥20 cells each.

Figure 6. Dual phase of ATP release from T cells.

(A) Jurkat T cells were stained with 2-2Zn(II), stimulated with beads carrying anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies, and ATP release was visualized with fluorescence microscopy (see also video 6). (B) ATP release was analyzed over time in regions of interest (ROIs) associated with the immune synapse (ROI 2) or not (ROI 1). Images are representative of n≥3 separate experiments and n≥10 cells each.

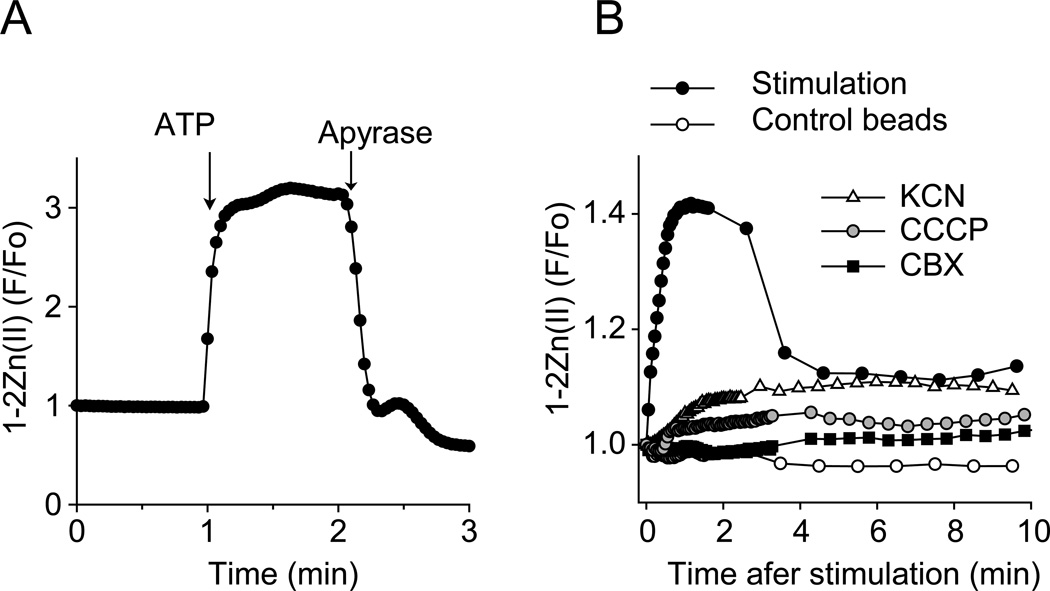

ATP release at the immune synapse requires mitochondrial ATP production

The imaging approaches described above in combination with fluorescent mitochondrial markers have shown that mitochondria are the primary source of the ATP that is released from stimulated T cells (Ledderose et al. 2014). Results obtained with the soluble 1-2Zn(II) probe provided additional critical information that points to the central role of mitochondrial ATP production in T cell activation. With a live cell imaging approach using 1-2Zn(II) to assess ATP released into bulk media, we found that inhibitors of mitochondrial ATP production (CCCP and KCN; Hanstein 1976, Terada 1981) blocked ATP release to an extent similar to that achieved by the pannexin-1 channel inhibitor carbenoxolone (CBX; Fig. 7). These findings indicated that mitochondria have a central role in triggering the autocrine purinergic signaling events that initiate T cell activation.

Figure 7. ATP release from stimulated T cells requires mitochondrial ATP production.

Jurkat cells were incubated with 10 µM of 1-2Zn(II) for 15 min on the microscope stage and ATP release into the supernatant was detected by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy. (A) After imaging for 1 min, exogenous ATP (10 µM) was added to unstimulated cells, followed by apyrase (20 U/ml) after another minute of imaging. (B) Jurkat cells were treated with KCN (500 µM), CCCP (10 µM), CBX (50 µM), or with vehicle control for 10 min prior to stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 coated or antibody-free control beads. Fluorescence time-lapse images were recorded with a 63× oil objective (NA 1.4) and analyzed by ImageJ software. Data points represent mean values of n=10 cell-free regions of interest and are representative of at least 3 separate experiments with similar results.

Mitochondria and ATP release sites colocalize at the immune synapse

Because of the involvement of mitochondria in T cell activation, we studied whether the intracellular distribution of mitochondria changes during T cell activation. Multichannel live cell imaging with 2-2Zn(II) and MitoTracker dyes such as MitoTracker Red CM-H2XRos revealed that mitochondria are rapidly activated and translocate to the immune synapse in response to T cell stimulation (Fig. 8). At the synapse, mitochondria colocalize with pannexin-1 channels and P2X1 and P2X4 receptors to allow localized ATP release and to facilitate autocrine purinergic signaling that promotes Ca2+ influx and T cell activation (Woehrle et al. 2010, Ledderose et al. 2014). Taken together, these findings support the concept that mitochondria and pannexin-1 channels trigger T cell activation by driving localized autocrine purinergic signaling at the immune synapse.

Figure 8. Mitochondria accumulate at regions of increased ATP release.

Active mitochondria in Jurkat cells were stained with MitoTracker Red CM-H2XRos as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. Then cells were loaded with 2-2Zn(II) and fluorescence microscope images were recorded before (top row) and after stimulation of cells with anti-CD3/CD28 antibody coated beads (bottom row). Colocalization of activated mitochondria and regions of activated ATP release were analyzed by ImageJ software (100× oil objective, NA 1.3; scale bar, 5 µm). Representative images of at least 5 separate experiments are shown.

Discussion

In order to observe ATP release from living cells, we have previously developed a microscope based method that has allowed us to visualize localized ATP release from the leading edge of neutrophils during chemotaxis (Chen et al. 2006, Corriden et al. 2007). This method was based on a tandem enzymatic reaction that results in NADPH formation when ATP is present in the extracellular space. Since NADPH is a highly fluorescent molecule, it can be visualized under a fluorescence microscope using an excitation wavelength of 340 nm. Although this method is highly sensitive and selective for ATP, it has significant drawbacks that include its limited dynamic range, the phototoxicity caused by ultraviolet illumination (Morys & Berger 1993, Wiedenmann et al. 2009), the need for exogenous NADP that may itself affect cell responses (Ying 2008), and the irreversible depletion of extracellular ATP for NADPH synthesis.

In this report, we describe novel methods that overcome these problems. These methods are based on a turn-on type ATP sensor, 1-2Zn(II), that can be used for ATP imaging in the extracellular space and a related probe, 2-2Zn(II), that can be used to monitor ATP release at the cell surface of living cells. These fluorescent probes can be used with excitation and emission wavelengths near 505 nm and 550 nm, respectively, limiting phototoxicity and allowing the use of conventional optics and filter sets widely available in confocal and wide field fluorescence microscope systems. A detection limit in the nanomolar range ATP makes the membrane targeting probe 2-2Zn(II) particularly practical for live cell imaging of ATP release. Binding of 1-2Zn(II) and 2-2Zn(II) to ATP is reversible and, unlike in the enzymatic method described above, it does not result in the depletion of extracellular ATP, which we found to impair normal cell function (Chen et al. 2006, Corriden et al. 2007). The fast imaging speed and good signal-to-noise ratio provide the necessary spatiotemporal resolution that has allowed us to gain unprecedented insights into the role of ATP signaling in immune cell activation (Bao et al. 2014, Ledderose et al. 2014). We believe that the imaging approaches described above can be adopted and will be useful to explore the role of purinergic signaling in many other physiological systems.

However, 1-2Zn(II) and 2-2Zn(II) also bind to polyphosphate species besides ATP (Ojida et al. 2008, Kurishita et al. 2012). Therefore, it is impossible to distinguish ATP, ADP, and PPi with these probes and it cannot be ruled out that the signal that is observed with these probes is caused by these polyphosphate compounds or by other nucleotide species such as UTP. Although this lack of specificity is a clear drawback, it may also be useful in some situations, for instance to gain insights into physiological processes of purinergic signaling that involve the ATP products ADP and PPi, which cannot be detected with the luciferase- or NADPH-based methods described above (Yegutkin 2008, Corriden et al. 2007).

A significant limitation of 1-2Zn(II) and 2-2Zn(II) is that they are prone to interference by compounds that affect the molecular confirmation and ATP binding properties of the polyphosphate sensor structure. We noted that high concentrations of EDTA (50 mM) and CaCl2 (100 mM) and moderate levels of hypertonicity (20 mM above isotonicity) induced by the addition of NaCl could markedly affect the fluorescence properties of the ATP sensor structure in 1-2Zn(II) and 2-2Zn(II). In addition, we found that the levels of phosphate present in cell culture media can have a profound inhibitory effect on the ATP binding property of the senor structure of 1-2Zn(II) and, to a lesser degree, of membrane bound 2-2Zn(II). To minimize the latter limitation required the use of buffers that do not contain phosphate. Compared to 1-2Zn(II), which was particularly sensitive to interference by phosphate, the membrane targeting 2-2Zn(II) probe was less affected by phosphate and we were able to employ conventional media such as HBSS for live cell imagining with 2-2Zn(II).

Using 2-2Zn(II), we were able to observe hotspots of ATP release at the cell surface of neutrophils and T cells. We observed distinct and dynamically changing foci of ATP release across the cell surface that seemed to mirror the highly dynamic processes of translocation and activation of mitochondria within T cells and neutrophils. In support of this notion, we recently showed that mitochondria are a primary source of the ATP released from stimulated immune cells (Bao et al. 2014, Ledderose et al. 2014). We also found evidence of different phases of ATP release in these cell types, which may be associated with different mechanisms of ATP release, for example via pannexin-1 channels or exocytosis as previously proposed (Fitz 2007, Chen et al. 2010, Tokunaga et al. 2010). Using 1-2Zn(II) and 2-2Zn(II) imaging, we noted that dead and dying cells generated particularly bright fluorescence signals, which supports a previously proposed role for ATP release as a find-me signal that leads to the clearance of apoptotic cells by phagocytes (Elliott et al. 2009).

Previously, we reported ATP release from different types of stimulated immune cells (Chen et al. 2006, Corriden et al. 2007, Yip et al. 2009, Chen et al. 2010). The use of the novel fluorescence methods described here has allowed us to confirm these findings, but we also observed that these cell types can release ATP in their non-stimulated resting states. Basal release of ATP is thought to control various physiological functions and complex organs such as the liver, lungs, and the kidney (Corriden & Insel 2010). We think that the fluorescence methods described in this report could provide the necessary information to define the role of purinergic signaling in such complex organs.

Supplementary Material

Visualization of fMLP-induced ATP release from neutrophils with 1-2Zn(II) (related to Fig. 2). Freshly purified human neutrophils were incubated with 10 µM of 1-2Zn(II), stimulated with fMLP (100 nM; added at t=0 s), and imaged with fluorescence microscopy for 54 s. Then exogenous ATP (1 µM) and apyrase (10 U/ml) were added as indicated. Objective: 100× oil, NA 1.30; frame rate: 20 frames min−1.

Visualization of rapid fMLP-induced bursts of ATP release (related to Fig. 3A). Freshly purified human neutrophils were incubated with 500 nM of 2-2Zn(II), stimulated with fMLP (10 nM; added at t=0 s), and imaged with fluorescence microscopy. Data were analyzed by ImageJ software and a surface plot video inserted on the right with the signal height (y-axis) indicating estimated ATP concentrations at the cell surface. Objective: 100× oil, NA 1.30; frame rate: 60 frames min−1.

Visualization of ATP release during cell polarization and pseudopod protrusion (related to Fig. 3B). Human neutrophils were stained with 2-2Zn(II) as described above and imaged following the addition of fMLP (1 nM; added at frame t=0 s). Objective: 100× oil, NA 1.30; frame rate: 20 frames min−1.

Imaging of active mitochondria and ATP release (related to Fig. 4). Human neutrophils were loaded with MitoTracker Red CM-H2XRos (100 nM, red), stained with 2-2Zn(II) as described above (green), stimulated with fMLP (1 nM; added at t=0 s), and time-lapse images were acquired with laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Image pairs were merged with ImageJ software. Objective: 630× oil, NA 1.40; frame rate: 15 frames min−1.

Localized ATP release at the immune synapse (related to Figs. 5 & 6). Jurkat cells were incubated with 500 nM of 2-2Zn(II), stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibody coated beads, and ATP release was imaged with fluorescence microscopy. ATP (100 µM) and apyrase (20 U/ml) were added at the indicated time frames as positive and negative controls, respectively. Objective: 63× oil, NA 1.40; frame rate: 20 frames min−1.

Dual phases of ATP release from T cells (related to Fig. 6). Jurkat cells were loaded with the membrane-bound ATP probe 2-2Zn(II) (500 nM) and fluorescence and bright field imaging was done as described above before and after addition of anti-CD3/CD28 coated beads. Frame rate: 20 frames min−1. ATP (100 µM) was added as a positive control at t=3:06 min. Objective: 100× oil, NA 1.30.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, GM-51477, GM-60475, AI-072287, AI-080582, T32 GM103702, a grant from the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program PR043034 (W.G.J.) and a grant from the German Research foundation (LE-3209/1-1; C.L.). We thank Prof. Itaru Hamachi and Dr. Yasutaka Kurishita for designing and kindly providing 1-2Zn(II) and 2-2Zn(II) and Dr. Masayuki Sato for valuable assistance with the experiments using 1-2Zn(II).

Footnotes

Contributions: C.L. and Y.B. optimized live cell imaging methods and generated results. J.Z. provided technical support. W.G.J. conceived the overall study concept, guided the study design, and drafted and finalized the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Bao Y, Chen Y, Ledderose C, Li L, Junger WG. Pannexin 1 channels link chemoattractant receptor signaling to local excitation and global inhibition responses at the front and back of polarized neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:22650–22657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.476283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Ledderose C, Seier T, Graf AF, Brix B, Chong E, Junger WG. Mitochondria regulate neutrophil activation by generating ATP for autocrine purinergic signaling. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:26794–26803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.572495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beigi R, Kobatake E, Aizawa M, Dubyak GR. Detection of local ATP release from activated platelets using cell surface-attached firefly luciferase. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:C267–C278. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.1.C267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Physiology and pathophysiology of purinergic neurotransmission. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:659–797. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, Yip L, Hashiguchi N, Zinkernagel A, Nizet V, Insel PA, Junger WG. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006;314:1792–1795. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Yao Y, Sumi Y, Li A, To UK, Elkha lA, Inoue Y, Woehrle T, Zhang Q, Hauser C, Junger WG. Purinergic signaling: a fundamental mechanism in neutrophil activation. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra45. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corriden R, Insel PA, Junger WG. A novel method using fluorescence microscopy for real-time assessment of ATP release from individual cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1420–C1425. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00271.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corriden R, Insel PA. Basal release of ATP: an autocrine-paracrine mechanism for cell regulation. Sci. Signal. 2010;3:re1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3104re1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Virgilio F. Purinergic signalling in the immune system. A brief update. Purinergic Signal. 2007;3:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9048-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MR, Chekeni FB, Trampont PC, Lazarowski ER, Kadl A, Walk SF, Park D, Woodson RI, Ostankovich M, Sharma P, Lysiak JJ, Harden TK, Leitinger N, Ravichandran KS. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature. 2009;461:282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature08296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitz JG. Regulation of cellular ATP release. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2007;118:199–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanstein WG. Uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;456:129–148. doi: 10.1016/0304-4173(76)90010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junger WG, Hoyt DB, Davis RE, Herdon-Remelius C, Namiki S, Junger H, Loomis W, Altman A. Hypertonicity regulates the function of human neutrophils by modulating chemoattractant receptor signaling and activating mitogen-activated protein kinase p38. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2768–2779. doi: 10.1172/JCI1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junger WG. Purinergic regulation of neutrophil chemotaxis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;65:2528–2540. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8095-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junger WG. Immune cell regulation by autocrine purinergic signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:201–212. doi: 10.1038/nri2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS, North RA. P2X receptors as cell-surface ATP sensors in health and disease. Nature. 2006;442:527–532. doi: 10.1038/nature04886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronlage M, Song J, Sorokin L, Isfort K, Schwerdtle T, Leipziger J, Robaye B, Conley PB, Kim HC, Sargin S, Schön P, Schwab A, Hanley PJ. Autocrine purinergic receptor signaling is essential for macrophage chemotaxis. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra55. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurishita Y, Kohira T, Ojida A, Hamachi I. Rational design of FRET-based ratiometric chemosensors for in vitro and in cell fluorescence analyses of nucleoside polyphosphates. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13290–13299. doi: 10.1021/ja103615z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurishita Y, Kohira T, Ojida A, Hamachi I. Organelle-localizable fluorescent chemosensors for site-specific multicolor imaging of nucleoside polyphosphate dynamics in living cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:18779–18789. doi: 10.1021/ja308754g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC Purinergic receptors in airway epithelia. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledderose C, Bao Y, Lidicky M, Zipperle J, Li L, Strasser K, Shapiro NI, Junger WG. Mitochondria are gate-keepers of T cell function by producing the ATP that drives purinergic signaling. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:25936–25945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.575308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis WH, Namiki S, Ostrom RS, Insel PA, Junger WG. Hypertonic stress increases T cell interleukin-2 expression through a mechanism that involves ATP release, P2 receptor, and p38 MAPK activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4590–4596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207868200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morys M, Berger D. The accurate measurements of biologically effective ultraviolet radiation. Proc SPIE. 1993;2049:152–161. [Google Scholar]

- Ojida A, Miyahara Y, Wongkongkatep J, Tamaru S, Sada K, Hamachi I. Design of dual-emission chemosensors for ratiometric detection of ATP derivatives. Chem Asian J. 2006;1:555–563. doi: 10.1002/asia.200600137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojida A, Takashima I, Kohira T, Nonaka H, Hamachi I. Turn-on fluorescence sensing of nucleoside polyphosphates using a xanthene-based Zn(II) complex chemosensor. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12095–12101. doi: 10.1021/ja803262w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada SF, Nicholas RA, Kreda SM, Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC. Physiological regulation of ATP release at the apical surface of human airway epithelia. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22992–23002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603019200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegatti P, Falzoni S, Pinton P, Rizzuto R, Di Virgilio F. A novel recombinant plasma membrane-targeted luciferase reveals a new pathway for ATP secretion. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3659–3665. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praetorius HA, Leipziger J. ATP release from non-excitable cells. Purinergic Signal. 2009;5:433–446. doi: 10.1007/s11302-009-9146-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk U, Westendorf AM, Radaelli E, Casati A, Ferro M, Fumagalli M, Verderio C, Buer J, Scanziani E, Grassi F. Purinergic control of T cell activation by ATP released through pannexin-1 hemichannels. Sci Signal. 2008;1:ra6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1160583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada H. The interaction of highly active uncouplers with mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;639:225–242. doi: 10.1016/0304-4173(81)90011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga A, Tsukimoto M, Harada H, Moriyama Y, Kojima S. Involvement of SLC17A9-dependent vesicular exocytosis in the mechanism of ATP release during T cell activation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:17406–17416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.112417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautmann A. Extracellular ATP in the immune system: more than just a"danger signal". Sci Signal. 2009;2:pe6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.256pe6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenmann J, Oswald F, Nienhaus GU. Fluorescent proteins for live cell imaging: opportunities, limitations, and challenges. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:1029–1042. doi: 10.1002/iub.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woehrle T, Yip L, Elkhal A, Sumi Y, Chen Y, Yao Y, Insel PA, Junger WG. Pannexin-1 hemichannel-mediated ATP release together with P2X1 and P2X4 receptors regulate T-cell activation at the immune synapse. Blood. 2010;116:3475–3484. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-277707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yegutkin GG, Mikhailov A, Samburski SS, Jalkanen S. The detection of micromolar pericellular ATP pool on lymphocyte surface by using lymphoid ecto-adenylate kinase as intrinsic ATP sensor. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:3378–3385. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-10-0993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yegutkin GG. Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: Important modulators of purinergic signalling cascade. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:673–694. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying W. NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH in cellular functions and cell death: regulation and biological consequences. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:179–206. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip L, Woehrle T, Corriden R, Hirsh M, Chen Y, Inoue Y, Ferrari V, Insel PA, Junger WG. Autocrine regulation of T-cell activation by ATP release and P2X7 receptors. FASEB J. 2009;23:1685–1693. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-126458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Visualization of fMLP-induced ATP release from neutrophils with 1-2Zn(II) (related to Fig. 2). Freshly purified human neutrophils were incubated with 10 µM of 1-2Zn(II), stimulated with fMLP (100 nM; added at t=0 s), and imaged with fluorescence microscopy for 54 s. Then exogenous ATP (1 µM) and apyrase (10 U/ml) were added as indicated. Objective: 100× oil, NA 1.30; frame rate: 20 frames min−1.

Visualization of rapid fMLP-induced bursts of ATP release (related to Fig. 3A). Freshly purified human neutrophils were incubated with 500 nM of 2-2Zn(II), stimulated with fMLP (10 nM; added at t=0 s), and imaged with fluorescence microscopy. Data were analyzed by ImageJ software and a surface plot video inserted on the right with the signal height (y-axis) indicating estimated ATP concentrations at the cell surface. Objective: 100× oil, NA 1.30; frame rate: 60 frames min−1.

Visualization of ATP release during cell polarization and pseudopod protrusion (related to Fig. 3B). Human neutrophils were stained with 2-2Zn(II) as described above and imaged following the addition of fMLP (1 nM; added at frame t=0 s). Objective: 100× oil, NA 1.30; frame rate: 20 frames min−1.

Imaging of active mitochondria and ATP release (related to Fig. 4). Human neutrophils were loaded with MitoTracker Red CM-H2XRos (100 nM, red), stained with 2-2Zn(II) as described above (green), stimulated with fMLP (1 nM; added at t=0 s), and time-lapse images were acquired with laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Image pairs were merged with ImageJ software. Objective: 630× oil, NA 1.40; frame rate: 15 frames min−1.

Localized ATP release at the immune synapse (related to Figs. 5 & 6). Jurkat cells were incubated with 500 nM of 2-2Zn(II), stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibody coated beads, and ATP release was imaged with fluorescence microscopy. ATP (100 µM) and apyrase (20 U/ml) were added at the indicated time frames as positive and negative controls, respectively. Objective: 63× oil, NA 1.40; frame rate: 20 frames min−1.

Dual phases of ATP release from T cells (related to Fig. 6). Jurkat cells were loaded with the membrane-bound ATP probe 2-2Zn(II) (500 nM) and fluorescence and bright field imaging was done as described above before and after addition of anti-CD3/CD28 coated beads. Frame rate: 20 frames min−1. ATP (100 µM) was added as a positive control at t=3:06 min. Objective: 100× oil, NA 1.30.