Abstract

Social defeat stress causes social avoidance and long-lasting cross-sensitization to psychostimulants, both of which are associated with increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression in the ventral tegmental area (VTA). Moreover, social stress upregulates VTA mu-opioid receptor (MOR) mRNA. In the VTA, MOR activation inhibits GABA neurons to disinhibit VTA dopamine neurons, thus providing a role for VTA MORs in the regulation of psychostimulant sensitization. The present study determined the effect of lentivirus-mediated MOR knockdown in the VTA on the consequences of intermittent social defeat stress, a salient and profound stressor in humans and rodents. Social stress exposure induced social avoidance and attenuated weight gain in animals with non-manipulated VTA MORs, but both these effects were prevented by VTA MOR knockdown. Rats with non-manipulated VTA MOR expression exhibited cross-sensitization to amphetamine challenge (1.0 mg/kg, i.p.), evidenced by a significant augmentation of locomotion. By contrast, knockdown of VTA MORs prevented stress-induced cross-sensitization without blunting the locomotor-activating effects of amphetamine. At the time point corresponding to amphetamine challenge, immunohistochemical analysis was performed to examine the effect of stress on VTA BDNF expression. Prior stress exposure increased VTA BDNF expression in rats with non-manipulated VTA MOR expression, while VTA MOR knockdown prevented stress-induced expression of VTA BDNF. Taken together, these results suggest that upregulation of VTA MOR is necessary for the behavioral and biochemical changes induced by social defeat stress. Elucidating VTA MOR regulation of stress effects on the mesolimbic system may provide new therapeutic targets for treating stress-induced vulnerability to substance abuse.

Keywords: mu-opioid receptor, social defeat stress, ventral tegmental area, cross-sensitization, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, amphetamine

1. Introduction

In humans, stress is one variable that influences the transition from recreational drug use to abuse, and it has been correlated with increased risk of substance abuse and relapse (Sinha, 2001, 2008, 2011). Rodent studies have shown that repeated social defeat stress exposure consistently produces social avoidance (Berton et al., 2006; Fanous et al., 2011b; Komatsu et al., 2011; Krishnan et al., 2007; Razzoli et al., 2009) and augments the effect of psychomotor stimulants, a phenomena known as ‘cross-sensitization’ (Covington and Miczek, 2001; Nikulina et al., 2004; Nikulina et al., 2012). Genetic mu-opioid receptor (MOR) knockout mice do not exhibit social avoidance following continuous social defeat (Komatsu et al., 2011), suggesting that MORs play a critical role in stress-induced changes in long-term neuroplasticity. In fact, even acute social defeat stress has been shown to rapidly upregulate MOR mRNA expression in the ventral tegmental area (VTA; Nikulina et al., 1999), while repeated social stress exposure increases VTA MOR mRNA expression for up to 14 days after the last episode (Nikulina et al., 2008). In the VTA MORs are expressed by gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurons (Garzon and Pickel, 2002; Sesack and Pickel, 1995), which are hyperpolarized in response to MOR stimulation, thus disinhibiting local dopamine (DA) transmission and facilitating response to drugs of abuse (Bergevin et al., 2002; Dacher and Nugent, 2011; Johnson and North, 1992; Vargas-Perez et al., 2009). Rats exposed to repeated social defeat stress, then challenged with an intra-VTA infusion of a MOR-specific agonist exhibited sensitized locomotor activity (Nikulina et al., 2008; Nikulina et al., 2005). This VTA opiate-induced sensitized locomotor activity was present at the same time point that social stress-induced cross-sensitization to psychomotor stimulants was observed (Covington and Miczek, 2001; Nikulina et al., 2004; Nikulina et al., 2012). Taken together, these findings indicate that increased VTA MOR expression might play a role in social stress-induced psychostimulant sensitization. Consistent with this view, MOR knockout mice exhibit reduced cocaine self-administration and increased VTA GABA transmission (Mathon et al., 2005). Furthermore, the expression of amphetamine sensitization is associated with persistent VTA MOR upregulation, and can be blocked by a treatment with MOR antagonist (Magendzo and Bustos, 2003; Trigo et al., 2010).

Increased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the VTA is frequently observed as a consequence of psychostimulant administration (Bolanos and Nestler, 2004; Corominas et al., 2007; Grimm et al., 2003; Horger et al., 1999; Thomas et al., 2008). Studies with morphine have shown that an interaction exists between VTA BDNF and MORs (Chu et al., 2007; Koo et al., 2012; Vargas-Perez et al., 2009). Additionally, increased VTA BDNF expression has been implicated as a long-term mediator of social stress-induced cross-sensitization (Nikulina et al., 2012), and in the VTA this increase persists for at least 2 weeks after the last social stress exposure (Berton et al., 2006; Fanous et al., 2010; Nikulina et al., 2012). In particular, overexpression of VTA BDNF was observed to exacerbate social stress-induced cross-sensitization to amphetamine (Wang et al., 2013), while viral deletion of VTA BDNF prevented social stress-induced social avoidance (Berton et al., 2006; Fanous et al., 2011b; Krishnan et al., 2007). Although VTA MOR mRNA expression rapidly increases following social stress exposure (Nikulina et al., 2008; Nikulina et al., 2005), VTA BDNF expression is affected more slowly (Fanous et al., 2010). Based on the modulatory relationship that exists between VTA MORs and BDNF (Chu et al., 2007; Koo et al., 2012; Vargas-Perez et al., 2009), it is possible that intermittent social defeat stress-induced increases of VTA BDNF are related to MOR upregulation in this brain region.

Although research has implicated VTA MORs in drug sensitization and social behaviors (Lutz and Kieffer, 2013a, b; Miczek et al., 2011b; Pitchers et al., 2014; Van Ree et al., 2000), it is unknown whether upregulation of VTA MORs causes the behavioral and biological effects of social defeat stress exposure. To address this question, the present study used lentivirus-mediated gene transfer and RNA interference to knockdown MORs in the VTA, and then assessed social stress-induced cross-sensitization to amphetamine and BDNF expression in the VTA. Given that social avoidance is altered in MOR knockout mice after continuous social stress (Komatsu et al., 2011), we also examined the effect of VTA MOR knockdown on social avoidance after stress exposure. Finally, the effect of VTA MOR knockdown on stress-induced deficits of weight gain was examined.

2. Experimental Methods

2.1 Subjects

Experimental animals were male Sprague-Dawley rats (N = 71; Charles River Laboratories, Hollister, CA) weighing 200–250 g on arrival. Three days before social stress exposure, subjects were individually housed in standard plastic cages (25×50×20 cm3). Twelve additional age-matched Sprague Dawley rats were group-housed 3 per cage and served solely as novel stimulus subjects during the social approach and avoidance test. Male Long-Evans rats (weighing 550–700 g), termed ‘residents’, were pair-housed with a tubal-ligated female in large plastic cages (37×50×20 cm3). All rats were maintained on a 12–12 reverse light-dark cycle (lights out at 0900 h) with free access to food (Purina Rodent Diet, Brentwood, MO) and water. Residents were previously screened for aggressive behavior and were used to induce social defeat stress in experimental “intruder” rats. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the Arizona State University and the University of Arizona. All studies were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 2011), and every effort was made to minimize pain and suffering, as well as the number of animals used.

2.2 Experimental Design

2.2.1 General Procedure

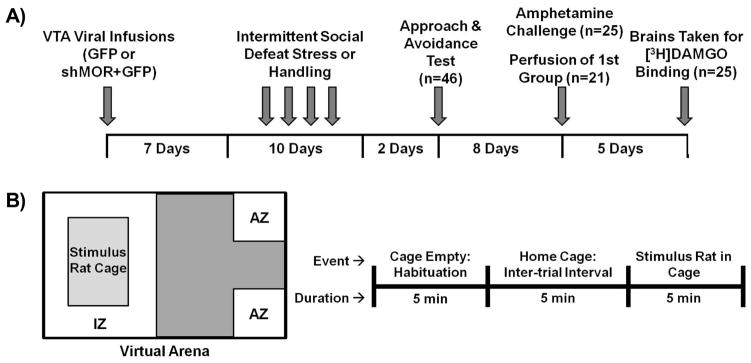

Upon arrival, experimental rats were habituated to laboratory conditions for 7 days before surgery to manipulate regional MOR level. Rats were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions: Non-Manipulated MOR+Handled, Non-Manipulated MOR+Stressed, MOR Knockdown+Handled, MOR Knockdown+Stressed. Three experiments were conducted in parallel (Fig 1A); one group of subjects (n = 25) received an amphetamine challenge 10 days after the last episode of intermittent social stress or handling to study the effects of VTA MOR knockdown on social stress-induced cross-sensitization. Seven days later, VTA tissue from this group of subjects was flash frozen for radioligand binding to verify the efficacy of MOR knockdown. A second group of drug-naïve subjects (n = 21) were perfused at the same time point after stress or handling to quantify VTA BDNF expression. Social approach and avoidance testing was performed two days after termination of social stress or handling procedures in both these groups. The third group of rats (n = 25) were weighed prior to each episode of intermittent social stress and handling, and again 10 days later to investigate the influence of VTA MOR knockdown on social stress-induced deficits in weight gain.

Figure 1.

Timeline of experimental events and schematic of social approach and avoidance test procedure. (A) Rats were given 7 days to recover from surgery, and were then exposed to intermittent (4x in 10 days) social defeat or handling procedures. Two days after the last episode of defeat, all rats were given the social approach and avoidance test. Ten days after the last episode of defeat, one group received amphetamine challenge while a separate group was perfused to examine immunohistochemical changes at the time cross-sensitization is observed. Five days after receiving the amphetamine challenge, brains from the remaining rats were removed and processed for in vitro [3H]DAMGO autoradiography to verify the location and efficacy of MOR knockdown. (B) All experimental subjects were assessed for social approach and avoidance using a procedure adapted from Berton et al. (2006). Left: Virtual arena dividing the chamber into 2 virtual zones: Interaction Zone (IZ), comprising of the 1019.35 cm2 area immediately surrounding the containment cage, and Avoidance Zone (AZ), which comprised the two corners, combined 52.2 cm2, opposite the containment cage. Right: Schematic of the timeline for the social approach and avoidance procedure.

2.2.2 Bilateral VTA infusion of lentiviral constructs

Rats assigned to control viral groups received infusions of lentivirus that expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) and a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) that does not target any known rat gene, while rats assigned to VTA MOR knockdown groups received a lentivirus that expresses GFP and a shRNA that targets MOR (shMOR) for RNA interference. Lentiviral constructs were prepared as previously described (Lasek et al., 2007). The shMOR lentivirus reduces VTA MOR expression by 88–97% (Lasek et al., 2007). Therefore, the viral titre was diluted by 50% with cold sterile saline to reduce the efficacy. After random assignment to GFP or shMOR knockdown conditions, rats were anesthetized using isoflurane and positioned in a stereotaxic frame (Leica Angle Two; Richmond, IL). The appropriate lentiviral construct (1.0 μl each) was infused bilaterally into the VTA (AP −5.15, ML ±2.15, DV −8.7, Tilt 10°; Paxinos and Watson, 2007) at a flow rate of 0.1 μl/min, and allowed to diffuse for 10 min before withdrawal of the syringe (Hamilton; Model 7105 KH; 24 gauge tip; Reno, NV). The accuracy of each infusion was later verified using localization of GFP expression. Subjects were given 7 days to recover before the start of intermittent social stress or handling procedures (Fig. 1A).

2.2.3 Intermittent social defeat stress and handling procedures

Social defeat stress was induced by a short confrontation between an aggressive resident and an experimental intruder rat, as previously described (Nikulina et al., 2004; Nikulina et al., 2012; Tidey and Miczek, 1996). After removing the female from the resident’s home cage, an experimental rat was placed inside the resident’s home cage for 5 min within the confines of a protective metal cage (15×25×15 cm3). The protective cage was then removed, allowing the resident to attack the experimental intruder rat until it displayed supine posture for at least 4 sec. Once submissive posture was exhibited, the experimental rat was placed back in the protective cage and exposed to threat from the resident for an additional 20 min before being returned to its own home cage. Intermittent social stress procedures were administered every third day for 10 days (Fig. 1A). At each corresponding time point, rats in the control groups were handled for approximately 2.5 min and then returned to their home cages.

2.3 Behavioral assessments

2.3.1 Social interaction

The social approach and avoidance test was conducted in a large plastic container (58×38×41 cm3) equipped with a lightweight containment cage. Experimental rats were habituated to the empty test chamber for 5 min, then reintroduced when a novel stimulus rat was within the containment cage (Fig. 1B). The behavior of experimental rat was recorded for 5 min using TopScan (Clever Systems Inc.; Reston, VA). The software divided the chamber into virtual zones: Interaction, which comprised the area surrounding the containment cage, and Avoidance, which comprised the two corners opposite the containment cage (Fig. 1B; arena adapted from Berton et al., 2006). The number of respective entries into the avoidance and interaction zones was recorded, as was the distance (cm) moved in each zone.

2.3.2 Amphetamine challenge

A low dose d-amphetamine challenge was administered to test for social stress-induced cross-sensitization (Nikulina et al., 2004; Nikulina et al., 2012). For two days prior to the challenge, rats were injected with vehicle (0.9% sterile saline; 1.0 ml/kg, i.p.), and were acclimated in their home cage to the procedure room for 1 h. On the day of the challenge, rats were moved in their home cage to the procedure room, and locomotor activity was recorded at 10 min intervals using video tracking software (Videotrack, Viewpoint Life Sciences; Montreal, Canada). Locomotor activity was detected as the number of and distance travelled during movements (>10 cm) across 170 min consisting of 3 phases: Baseline, Saline, and Amphetamine. Baseline data were recorded for 30 min, after which a saline injection (1.0 ml/kg, i.p.) was given and locomotor activity was recorded for 60 min. Finally, rats received an injection of d-amphetamine sulfate (1.0 mg/kg, i.p.; Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO), and locomotor data were recorded for 80 min. Video tracking and data collection were paused during the administration of saline and amphetamine injections. Rather than stereotypical behaviors, this dose of amphetamine has been shown to primarily induce large ambulatory movements (Geyer et al., 1987). In order to quantify amphetamine sensitization, ambulatory movements (> 10 cm) were measured in terms of the number of movements initiated and the distance travelled (cm) during such movements.

2.4 Tissue harvesting

2.4.1 Fresh frozen VTA tissue for radioligand binding

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, and their brains were rapidly removed and frozen in −35°C 2-methylbutane for 15 sec, then stored at −80°C prior to sectioning. On a cryostat, serial 20 μm sections through the VTA were collected (from AP −4.8 to −5.5; Paxinos and Watson, 2007) for radioligand binding and localization of GFP expression. Sections were thaw-mounted onto glass microslides (Superfrost Plus; Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA), dried in a vacuum chamber at 4°C, and stored at −80°C prior to processing. Separate slides were used to verify the accuracy and distribution of lentiviral infusions based on fluorescent detection of GFP expression.

2.4.2 Perfused VTA tissue for BDNF immunohistochemistry

As previously described (Fanous et al., 2010; Fanous et al., 2011a; Fanous et al., 2011b), rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, i.p.; Euthasol, Virbac Co., St. Louis, MO) and perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were then removed, post-fixed for 1.5 hours at 4°C, and placed in graded sucrose solutions. Frozen brain tissue was sectioned on a sliding microtome (20 μm) and serial VTA sections were mounted onto slides from 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4). Adjacent slides from each brain were processed for either BDNF immunohistochemistry or fluorescent localization of GFP expression.

2.5 [3H]DAMGO autoradiography

2.5.1 Radioligand binding

Fresh frozen brain sections were used to verify shMOR knockdown in the VTA using tritiated [D-Ala2,N-MePhe4,Gly-ol5] enkephalin ([3H]DAMGO; NIDA Drug Supply Program; Bethesda, MD), as described by Zhou and Hammer (1995). Briefly, slides were placed in pre-incubation solution (15 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0 mg/ml BSA) for 30 min at 4°C, then were incubated in 10 nM [ 3H]DAMGO solution (50 mM Tris buffer, 3.0 mM Mn acetate, 1.0 mg/ml BSA) with or without the addition of naloxone (10 μM; NIDA Drug Supply Program) for 60 min at 22°C. Sl ides were washed with a 50 mM Tris buffer at 4°C, then dried and exposed on Kodak BIO Max MR X-ray film (Carestream; Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) for 10 weeks at room temperature. Sections incubated in 1000-fold excess unlabeled naloxone were utilized to determine non-specific binding in subsequent autoradiography.

2.5.2 Autoradiography analysis

Autoradiograpy film was developed and scanned at high resolution. In order to determine whether the shMOR viral construct infected regions outside of the VTA, the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) was chosen as a control region due to its close proximity to the VTA, and because social stress does not affect MOR expression in substantia nigra regions (Nikulina et al., 1999; Nikulina et al., 2005). The SNc, not to be confused with the medial terminal nucleus accessory optic tract (MT), contains a higher density of MOR labeling than either the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) or VTA (Herkenham and Pert, 1982). Using this difference in expression, the SNc could be clearly demarcated on scans of autoradiographs by measuring the area directly above the SNr, lateral to the MT, and ventrolateral to the medial lemniscus. Optical densities for these regions were measured bilaterally in 2–3 sections using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, USA, http://imagej.nih.gov/ij), and then converted to μCi/g using calibrated [3H] radiostandards (ART-123, ARC Inc.; St. Louis, MO) co-exposed with sections. For each subject, bilateral measurements were averaged across sections to yield total ligand binding in the VTA and SNc, respectively.

2.6 BDNF immunohistochemistry and quantification

2.6.1 Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed using BDNF polyclonal antisera as described previously (Fanous et al., 2010). Briefly, blocking solution (10% normal goat serum/0.5M KPBS/0.4% Triton X-100) was applied to sections for 1 h at room temperature, then the primary antibody diluted in blocking solution (1:1000 dilution; SP1779, Millipore/Chemicon; Temecula, CA) was applied for 48 hr at 4°C. Sections were then incubated for 1 h with a biotinylated rabbit secondary antibody, treated with avidin/biotin complex solution for 45 min (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit; Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA), and developed using a diaminobenzidine (DAB) peroxidase substrate kit with nickel intensification (Vector Laboratories).

2.6.2 Modified stereological cell counts

Tissue sections were imaged using a Zeiss Axioskop with a 20x objective, and digitalized using a color digital camera. Immunolabeled cells were quantified using Stereo Investigator software (MBF Biosciences; Williston, VT), and the analysis was conducted using the modified stereology counting procedure described in Fanous et al. (2011a) and Nikulina et al. (2012). Briefly, a grid of 48 squares (0.0075 mm2) was overlaid on each of 2–3 VTA sections from each subject. Immunolabeled cells were counted in half the grid squares, the precise squares being randomly determined. Cells exhibiting a black-blue reaction product indicative of immunolabeling were counted such that cells crossing the bottom or right lines of each square were included, while cells crossing the top or left lines of the square were excluded from analysis. For each subject, estimates of total labeling density (mm2) were calculated by averaging the bilateral counts of labeled cell profiles across sections, and then dividing the total number of cell profiles by the total area assessed (0.18 mm2).

2.7 Statistical analyses

The results of each measure are expressed as mean ± standard error (SEM) and a p value ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant. All statistical analyses were run using SPSS software, version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and Tukey’s HSD was considered the preferred post hoc test across experiments. An exception was made in the case of the amphetamine challenge, where Fisher’s LSD was used because violations of sphericity necessitated our use of a more conservative test of the main effects. Data from subjects were excluded only in the case of error during video tracking or loss of data due to damaged tissue sections: no statistical outliers were excluded. The locomotor and social approach and avoidance assays relied on automated video tracking systems, requiring that the animals be housed in black bedding to block light from reflecting off the cage bottom. However in some instances, rats exposed the cage floor while moving, causing illumination artifacts that necessitated the removal of individual bin data due to inaccurate tracking. In addition, damage to tissue sections during processing sometimes precluded data collection from brain regions. More specifically in the locomotor and social approach and avoidance assays, which relied on automated video tracking systems, individual bin data were removed in those instances where reflection artifacts prevented accurate tracking. For analyses of mounted tissue sections, the sample size of each group was also reduced in cases where tissue was damaged in the course of processing.

2.7.1 Weight gain data

The initial weight obtained at the start of social stress procedures was used to normalize all subsequent data (n = 25) to weight gained from that time onward; no subjects were excluded from the analysis. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess differences in weight at each time point, and all significant main effects were analyzed using Tukey’s test for post hoc comparisons among the means.

2.7.2 Social interaction

Social approach and avoidance data were analyzed in terms of the number of entries to, and the distance travelled (cm) within the interaction and avoidance zones (Fig. 1B). Where illumination artifacts interfered with tracking, data were lost in a zone-specific manner. For example, avoidance zone entry data were analyzed from 40 subjects because illumination artifacts resulted in the exclusion of subjects from the following groups: GFP-Handled: 1; GFP-Stressed: 3; shMOR-Handled: 2. For distance travelled in the avoidance zone, an additional tracking error which occurred after a subject entered the zone further reduced the number of analyzed subjects to 35; subjects were excluded from the following groups: GFP-Handled: 2; GFP-Stressed: 1; shMOR-Handled: 5; shMOR-Stressed: 3. Illumination artifacts and tracking error reduced the number of subjects in the interaction zone to 37; subjects were excluded from the following groups: GFP-Stressed: 3; shMOR-Handled: 4; shMOR-Stressed: 2. A one-way ANOVA was run on data pertaining to each zone and any significant main effects were followed by an analysis of post hoc comparisons with Tukey’s test.

2.7.3 Locomotor activity

Locomotor data were analyzed using separate multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) for the mean number and distance (cm) travelled during ambulatory movements. In order to overcome violations of sphericity in the output of repeated measures ANOVA, MANOVA was used to analyze the number and distance of ambulatory movements exhibited throughout the amphetamine challenge. Significant multivariate effects were followed by univariate analyses to determine which time points produced significant group differences. Significant univariate effects were further analyzed for post hoc comparisons using Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test. Data were analyzed from 21 subjects for both dependent measures of ambulatory movements. Some subjects’ data were excluded from analysis due to the presence of illumination artifacts that interfered with tracking: GFP-Stressed: 2; shMOR-Handled: 1; shMOR-Stressed: 1.

2.7.4 MOR binding and BDNF expression

The results of radioligand binding with [3H]DAMGO in the VTA and SNc, as well as the results of BDNF immunohistochemistry in the VTA were analyzed using separate one-way ANOVAs, and where necessary, significant main effects were followed by post hoc comparisons with Tukey’s test. In the case of VTA [3H]DAMGO results, a violation of homogeneity was corrected for with Welch’s F test. Sample sizes were reduced after the target region was damaged during processing for BDNF immunohistochemistry in 2 subjects from the shMOR-Handled group, and during [3H]DAMGO binding for 1 shMOR treated subject. Consequently, BDNF data were analyzed from 19 subjects, while receptor autoradiography was analyzed from 25 subjects in the VTA and 24 subjects in the SNc.

3. Results

3.1 Verification of MOR Knockdown Using [3H]DAMGO Autoradiography

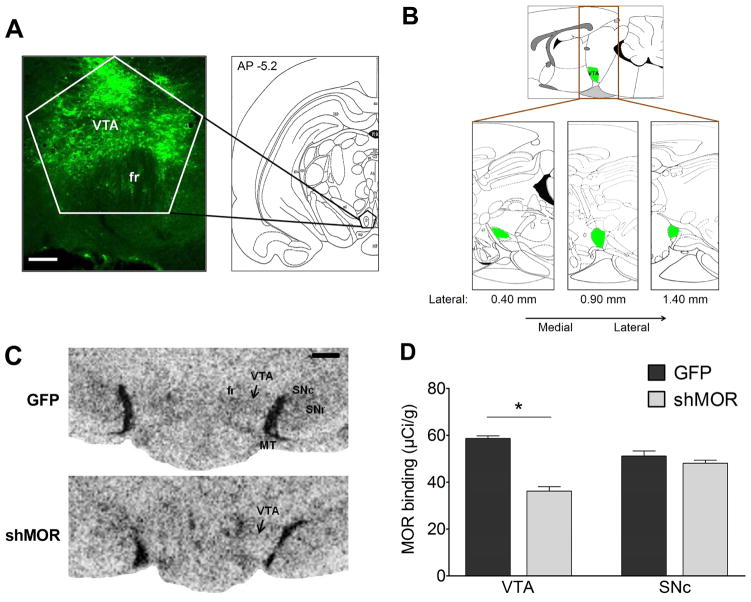

Fluorescent detection of virally expressed GFP revealed that lentiviral infusions were specific to the VTA (Fig. 2A), and GFP was not detected in either SN region (data not shown). While lentiviral constructs were infused at AP −5.15, GFP expression indicated infusions to the target site varied by ±0.1 mm, and that the average spread of GFP was within AP −4.8 to −5.5 and Lateral 0.4 mm to 1.4 mm (Fig. 2B). Quantitative in vitro autoradiography with [3H]DAMGO was used to determine the functionality of VTA MORs after lentivirus-mediated knockdown. Compared to the control GFP lentiviral construct, the subjects infused with the shMOR construct showed reduced [3H]DAMGO binding (Fig. 2C). One-way ANOVA revealed that this effect was significant in the VTA (n = 25, F1,20.13 = 102.46, p < 0.0001), but not the SNc (n = 24, F1,22 = 1.63, p > 0.22; Fig. 2D). Thus, our surgeries were accurate and bilateral shMOR knockdown selectively reduced VTA MOR binding density.

Figure 2.

[3H]DAMGO autoradiography revealed that the shMOR construct, but not the scrambled GFP construct, significantly reduced MOR binding in the VTA, but not the SNc. (A) Left: Representative image of reporter GFP expression in infected VTA cells (fr: fasciculus retroflexus; scale bar = 100 μm). Right: Plate 37, modified from Paxinos and Watson (2007). (B) Parasagittal illustrations showing the extent of GFP expression across the VTA, drawn in green (lateral plates 0.40 – 1.4, modified from Paxinos and Watson, 2007). (C) Representative autoradiographs of [3H]DAMGO binding in the VTA after infusion of either scrambled-GFP or shMOR lentiviral constructs (MT: medial terminal nucleus of the accessory optic system; scale bar = 500 μm). (D) shMOR lentiviral construct (n = 14) significantly (* - p < 0.0001) reduced MOR binding in the VTA compared to the scrambled-GFP construct (n = 11), without affecting MOR binding of either the GFP (n = 11) or shMOR (n = 14) groups in the adjacent SNc (p > 0.22).

3.2 Effect of VTA MOR knockdown on intermittent social stress-induced deficit of weight gain

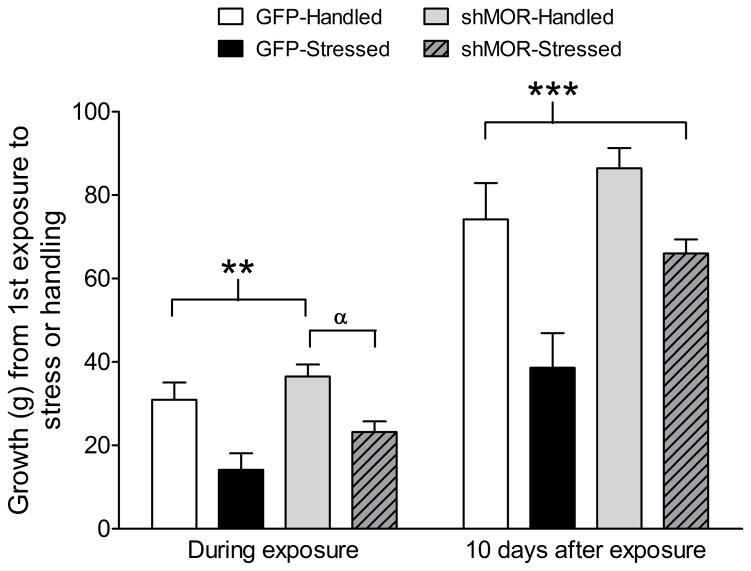

Weight gain data (n = 25) revealed a significant main effect during social stress exposure (F3,21 = 10.15, p < 0.0003; Fig. 3), and 10 days after the last stress episode (F3,21 = 9.46, p < 0.0004). Post hoc comparisons at this time point show that the GFP-Stressed group experienced less weight gain than either the GFP-Handled or shMOR-Handled groups (p < 0.006), while the shMOR-Stressed group only differed from the shMOR-Handled group (p < 0.02). Ten days after the final episode of social stress, the GFP-Stressed group showed significantly lower body weights compared not only to GFP-Handled and shMOR-Handled groups (p ≤ 0.006), but also the shMOR-Stressed group (p < 0.05). These data suggest that social stress significantly reduces body weight, and that while VTA MOR knockdown attenuated this effect during social stress exposure, it rescued this effect 10 days after termination of stress.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of VTA MORs prevents social stress-induced deficit of weight gain. While undergoing social stress or handling, GFP-Stressed rats (n = 5) exhibited significantly (** - p < 0.05) less weight gain than did GFP-Handled (n = 6) or shMOR-Handled (n = 7) rats. By contrast, shMOR-Stressed rats (n = 7) did not differ from GFP-Handled or -Stressed rats, showing significantly (α - p < 0.05) less weight gain than shMOR-Handled rats. Ten days after the last episode of exposure, GFP-Stressed rats had gained significantly (* - p < 0.05) less weight than all other groups.

3.3 Effect of VTA MOR knockdown on intermittent social stress-induced social avoidance

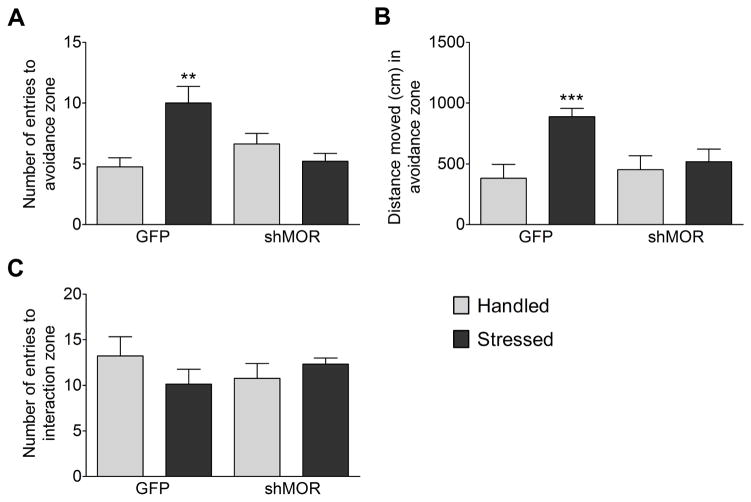

The social approach and avoidance test revealed a main effect of experimental group on number of entries to the avoidance zone (n = 40, F3,36 = 5.89, p = 0.002), with significantly more entries by GFP-Stressed rats compared to both GFP-Handled (p < 0.005) and shMOR-Stressed (p < 0.004) groups (Fig. 4A). Similarly, there was a significant main effect of experimental group on the distance traveled in the avoidance zone (n = 35, F3,31 = 4.77, p = 0.008), with significantly more activity in the GFP-Stressed group than the GFP-Handled (p = 0.011), shMOR-Handled (p < 0.05), or shMOR-Stressed (p < 0.05) groups. There was no main effect of experimental group on the number of entries to the interaction zone (n = 37, F3,26 = 1.14, p = 0.351; Fig. 4C). These data suggest that prior social stress exposure significantly increases social avoidance, and local VTA depletion of MOR prevents social stress-induced social avoidance without significantly altering social interaction.

Figure 4.

Knockdown of VTA MORs prevents social stress-induced social avoidance. (A) GFP-Stressed rats (n = 7) made significantly (* - p < 0.005) more entries to the avoidance zones than did GFP-Handled (n = 7) or shMOR-Stressed rats (n = 14). (B) GFP-Stressed rats (n = 9) were significantly (*** - p < 0.05) more active in the avoidance zones than GFP-Handled (n = 7), shMOR-Handled (n = 8), or shMOR-Stressed (n = 11) rats. (C) GFP-Stressed rats (n = 7) showed a slight tendency to spend less time in the interaction zone, but there was no significant (p > 0.3) main effect compared to GFP-Handled (n = 9), shMOR-Handled (n = 9), or shMOR-Stressed (n = 12) groups.

3.4 Effect of VTA MOR knockdown on intermittent social stress-induced cross-sensitization

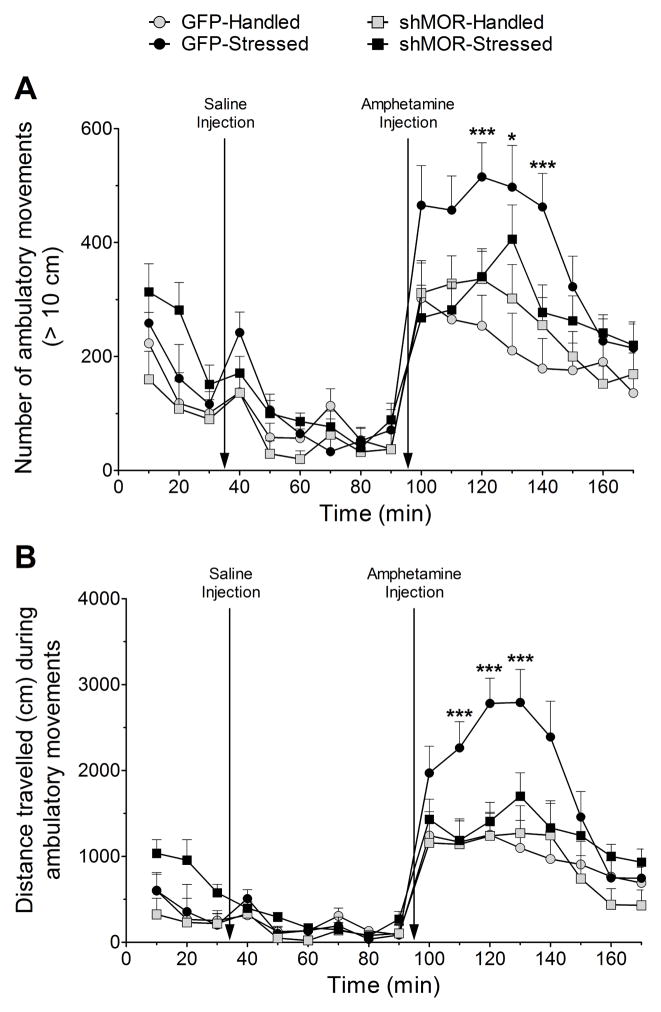

There were significant main effects of experimental group on the number of ambulatory movements (n = 21, Wilks’ λ= 3.78×10−7, F51.0,17 = 10.57, p = 0.019, η2 = 0.993, observed power = 0.87) and distance travelled during ambulatory movements(n = 21, Wilks’ λ= 1.26×10−6, F51.0,17 = 7.03, p = 0.039, η2 = 0.989, observed power = 0.87) across all time points. The number of movements differed significantly only, at 30 (F 3,17 = 3.66, p = 0.034), 40 (F3,17 = 3.36, p = 0.043), and 50 (F3,17 = 4.46, p = 0.017) min after amphetamine injection, but there were no differences across groups before or after saline injection (p > 0.05 at all other time points). Post hoc testing (Fig. 5A) showed that the GFP-Stressed group exhibited significantly greater number of movements compared to GFP-Handled (p < 0.005) and both shMOR-Handled and -Stressed groups (p < 0.05) at 30 min after amphetamine injection, compared to GFP-Handled (p < 0.01) 40 min post-amphetamine, and compared to GFP-Handled (p < 0.002) and both shMOR-Handled and -Stressed groups (p < 0.03) 50 min after amphetamine.

Figure 5.

Knockdown of VTA MORs prevents social stress-induced amphetamine cross-sensitization without affecting baseline activity. Multivariate analyses revealed that the only significant main effects occurred during the amphetamine phase of the assay. Data collection and video tracking were paused to administer saline and amphetamine, vertical arrows denote the time point when injection occurred. (A) GFP-Stressed rats (n = 4) exhibited significantly (*** - p < 0.05) more movements at 120 and 140 min compared to GFP-Handled (n = 5), shMOR-Handled (n = 6), and shMOR-Stressed (n = 6) rats, and differed significantly (* - p < 0.02) from GFP-Handled rats at 130 min. (B) GFP-Stressed rats travelled a significantly (*** - p < 0.03) greater distance at 110, 120, and 130 min compared to all other groups.

Similarly, distance travelled exhibited significant main effects only 20 (F3,17 = 3.51, p = 0.038), 30 (F3,17 = 6.83, p = 0.003), and 40 (F3,17 = 4.86, p = 0.013) min after amphetamine injection. Post hoc analyses (Fig. 5B) showed that the GFP-Stressed group moved a significantly greater distance compared to the GFP-Handled, shMOR-Handled, and shMOR-Stressed groups (p < 0.02) 20 min after amphetamine injection, compared to GFP-Handled and both shMOR groups (p < 0.002) 30 min post-injection, and compared to the GFP-Handled and both shMOR groups (p < 0.03) groups 40 min post-amphetamine. Thus, the GFP-Stressed group showed social stress-induced cross-sensitization following amphetamine challenge, but the shMOR-Stressed group did not.

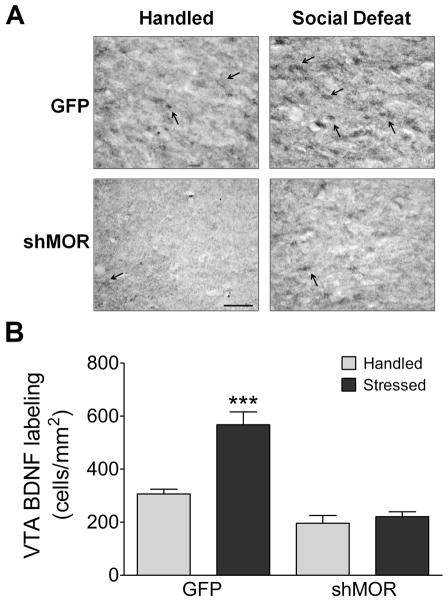

3.5 Effect of VTA MOR knockdown on VTA BDNF after intermittent social stress exposure

There was a significant main effect of experimental group on VTA BDNF expression (n = 19, F3,15 = 30.17, p < 0.0001), such that the GFP-Stressed group had significantly greater VTA BDNF expression compared to GFP-Handled, shMOR-Handled, and shMOR-Stressed groups (p < 0.0001, Fig. 6). There were no significant differences between GFP-Handled and either of the shMOR groups, regardless of stress treatment (p > 0.15). Thus, social stress-induced increase of VTA BDNF expression is blocked by knockdown of MORs in the VTA.

Figure 6.

Knockdown of VTA MORs blocks social stress-induced increase of VTA BDNF expression. (A) Representative images of BDNF labeling in the VTA approximately AP −5.1 from bregma. More BDNF labeled cells (identified by arrows) are visible in the GFP-Stressed group than in any others. (Scale bar = 100 μm) (B) The GFP-Stressed group (n = 5) exhibited significantly (* - p < 0.0001) more VTA BDNF immunolabeling than GFP-Handled (n = 4), shMOR-Handled (n = 4), or shMOR-Stressed (n = 6) groups. Numbers of labelled cells did not significantly differ between GFP-Handled rats and either shMOR group (p > 0.15).

4. Discussion

Our data show that lentivirus-mediated overexpression of shMOR successfully reduced MOR binding activity in the VTA, and that the affected region was limited to the VTA. Furthermore, we show that intermittent social stress induction of VTA MORs is required for various behavioral and biological changes. For example, we observed that lentivirus-mediated knockdown of VTA MORs blocks intermittent social stress-induced social avoidance, cross-sensitization to amphetamine, and deficit of weight gain, as well as the augmented VTA BDNF expression which normally persists 1–4 weeks after stress exposure.

4.1 VTA MOR upregulation is necessary for intermittent social stress-induced weight gain deficits

Exposure to social stress attenuated weight gain both during and 10 days after social stress exposure, which is consistent with previous findings (Fanous et al., 2011b; Meerlo et al., 1996; Pulliam et al., 2010; Venzala et al., 2012). VTA MOR knockdown rescued the deficit of weight gain 10 days after the last episode of stress, but not during stress exposure. That knockdown of VTA MORs attenuated and promoted recovery from social stress-induced weight gain deficit is consistent with a report of increased body weight in MOR knockout mice (Han et al., 2006). Another study using the same lentiviral construct in the VTA (Lasek et al., 2007) also showed no significant effect on weight, indicating that VTA MOR knockdown is not sufficient to alter weight gain in the absence of social stress.

The role of MORs in the regulation of food intake and weight gain is complex, making it difficult to separate MOR effects on food palatability, food intake, and a more general increase of hedonic value. Pharmacological stimulation of MORs has frequently been associated with increased hedonic value of food and drug stimuli (Badiani et al., 1995; Nathan and Bullmore, 2009), while MOR antagonism has been associated with decreased consumption of highly palatable food (Segall and Margules, 1989), as well as decreased sensitivity to natural reward (Pitchers et al., 2014). Stimulation of VTA MORs has been found to facilitate food consumption in a dopamine D1 receptor-dependent manner (Badiani et al., 1995; MacDonald et al., 2004), while antagonism reduced consumption of palatable foods (Segall and Margules, 1989). Based on this, one might expect that VTA MOR knockdown would further reduce weight gain by altering feeding behaviors. By contrast, our data show that VTA MOR knockdown rescues the stress-induced deficit in weight gain without affecting normal weight gain.

If knockdown of VTA MORs rescued the stress-induced reduction of weight gain by attenuating the psychological effects of stress, one might expect to see signs of increased reward or hedonic value in the amphetamine challenge or social approach and avoidance test. However, compared to GFP-Handled rats, subjects in the shMOR-Handled group did not show increased, or impaired response to amphetamine, or differ in social interaction. That subjects with VTA MOR knockdown, regardless of stress treatment, did not exhibit significant differences in weight gain compared to control GFP-Handled subjects, suggests that the rescue of weight gain is likely due to the prevention of downstream stress-induced changes in the mesolimbic circuit. In support of this idea, stress-induced increase of VTA BDNF expression was prevented by VTA MOR knockdown, and BDNF expression in the VTA is necessary for the stress-induced deficit of weight gain (Fanous et al., 2011).

The current study did not measure food consumption, so we cannot ascertain whether altered food intake contributed to the weight gained after stress with or without VTA MOR knockdown. However, if the stress-induced deficit of weight gain were related to VTA MOR-mediated changes in food intake, one would expect both Handled-and Stressed-shMOR knockdown groups to show significant differences in weight gain compared to GFP-Handled rats, which was not the case. There is some evidence to suggest that that MOR activity can alter weight gain without producing deficits in food consumption. In particular, daily morphine injection for 8 days had no effect on weight gain or food intake, while a parallel group of subjects that received escalating doses of morphine exhibited reduced weight gain without significant any significant effect on food consumption (Ren et al., 2013). In the same study, injections of escalating doses of morphine led to activation of cAMP responsive binding element protein (pCREB) in the VTA, implicating this region in MOR-mediated reduction of weight gain, but not food intake. Based on this, it is possible that escalating endogenous mu-opioid activity in the VTA underlies the weight gain deficit seen after social stress.

4.2 Upregulation of VTA MORs is necessary for intermittent social stress-induced social avoidance

Rodents with non-manipulated VTA MORs and a history of social stress engaged in significantly more social avoidance (Berton et al., 2006; Fanous et al., 2010; Komatsu et al., 2011). However, MOR knockout mice do not show social avoidance after continuous social stress (Komatsu et al., 2011), just as our knockdown of VTA MORs prevented intermittent social stress-induced social avoidance. MORs have been implicated in the rewarding components of social behavior, while MOR antagonists are associated with reduced social play (Vanderschuren et al., 1997) and experience-induced facilitation of sexual behavior (Pitchers et al., 2014), allowing for the possibility that VTA MOR knockdown might alter normal social interaction. However, our data reveal that VTA MOR knockdown in handled rats did not alter any measures of social interaction, suggesting that VTA MORs affect social behavior only upon the impact of stress exposure.

Previous research has also indicated that social history alone (isolation vs. social housing) or in conjunction with a social interaction test has a profound effect on MOR expression (Vanderschuren et al., 1995). Specifically, long-term social isolation increased MOR binding density in the VTA, while an acute social interaction reduced VTA MOR binding. Taken together, it is possible that positive and negative social situations alter VTA MOR expression, respectively decreasing or increasing VTA MOR activity.

4.3 Knockdown of VTA MORs prevents intermittent social stress-induced cross-sensitization

Stressed rats with non-manipulated VTA MORs exhibited significantly greater locomotor activity after a low dose amphetamine challenge, confirming prior reports that intermittent social stress induces amphetamine cross-sensitization 10 days after the last stress episode (Covington and Miczek, 2001; Nikulina et al., 2012). By contrast, knockdown of VTA MORs prevented social stress-induced cross-sensitization without blocking amphetamine-induced locomotion. VTA MORs are presynaptically expressed by GABA neurons (Garzon and Pickel, 2002; Sesack and Pickel, 1995), and when activated, reduce GABAergic inhibition of VTA DA neurons (Bergevin et al., 2002; Dacher and Nugent, 2011; Johnson and North, 1992; Trigo et al., 2010; Vargas-Perez et al., 2009) and facilitate response to psychomotor stimulants. Thus, if stimulation of MORs in the VTA indirectly increases VTA DA activity by reducing GABA transmission, then it is likely that knockdown of VTA MORs increases GABA release. In fact, MOR knockout mice showed enhanced VTA GABA release onto local DA neurons, resulting in reduced cocaine self-administration (Mathon et al., 2005).

We observed that knockdown of VTA MORs did not block psychomotor activation following amphetamine challenge, even though treatment with a MOR antagonist has been shown to abolish amphetamine responses (Magendzo and Bustos, 2003). This suggests that knockdown of VTA MORs does not produce unnatural alterations of mesolimbic tone. Our results reveal that VTA MOR upregulation is necessary for intermittent social stress-induced cross-sensitization to amphetamine. As such, in the VTA social stressors may function to increase endogenous MOR activity on GABA neurons, thus reducing the GABAergic inhibition of local DA neurons and facilitating behavioral sensitization to psychostimulant drugs.

4.4 VTA MORs are necessary for induction of VTA BDNF by intermittent social stress

The two-fold increase of VTA BDNF expression which we observed in the VTA is consistent with previous reports (Berton et al., 2006; Fanous et al., 2010; Nikulina et al., 2012). More importantly, we found that knockdown of VTA MORs prevents induction of VTA BDNF by social stress exposure. That knockdown of VTA MORs blocks social stress-induced increase of BDNF labeling suggests that VTA BDNF induction after social stress exposure is dependent on local MOR upregulation. In fact, increased MOR activity in hippocampus also induces local BDNF mRNA (Zhang et al., 2006). While others have suggested that VTA BDNF modulates the function of local MORs (Koo et al., 2012; Vargas-Perez et al., 2009), we show herein that VTA MORs can regulate the local expression of BDNF. These reciprocal findings may be attributed to differences between exogenous opiate and endogenous opioid functions, as well by differences in the VTA input systems recruited by exposure to morphine and social stress.

Although VTA BDNF is predominantly thought to be found in DA neurons (Gall et al., 1992; Seroogy et al., 1994), it is possible that MORs may control the transmission of VTA GABA neurons to indirectly produce subsequent changes in local DA neurons. Specifically, if MOR activity on GABA neurons increases the excitability of local DA neurons (Mathon et al., 2005), then the subsequent reduction in VTA GABAergic tone allows for MORs to affect BDNF expression in VTA DA neurons, potentially by altering the intracellular signaling that regulates BDNF expression in DA, for example mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK) or cAMP responsive binding element protein (CREB; Covington et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2006; Russo and Nestler, 2013; Shieh and Ghosh, 1999).

Previous studies have indicated that VTA BDNF is crucial for social stress-induced social avoidance (Berton et al., 2006; Fanous et al., 2011b) and cross-sensitization to amphetamine (Wang et al., 2013), and have shown that VTA MOR upregulation occurs early in the cross-sensitization process (Nikulina et al., 2008; Nikulina et al., 1999; Nikulina et al., 2005), prior to a persistent increase of VTA BDNF expression (Fanous et al., 2010). Thus it is likely that our VTA MOR knockdown prevented social stress-induced alterations of behavior by preventing increased BDNF expression as a consequence of MOR-dependent increases in VTA GABAergic tone. In support of this, and consistent with the preventative behavioral effects of our VTA MOR knockdown, is the study by Mathon et al. (2005), in which genetic MOR knockout mice showed increased GABAergic input onto local VTA DA neurons and decreased cocaine reinforcement. Thus it is likely that social stress upregulates MOR expression on VTA GABA neurons to facilitate BDNF expression in local DA neurons, while VTA MOR knockdown may increase VTA GABAergic tone, preventing subsequent social stressor-induced changes in the region.

4.5 Concluding remarks

In summary, knockdown of MORs in the VTA prevents intermittent social stress-induced cross-sensitization to amphetamine, social avoidance, deficit of weight gain, and increase of VTA BDNF expression. In rats, continuous social stress suppresses cocaine reward and decreases VTA BDNF expression (Miczek et al., 2011), however it is unknown whether continuous social stress alters VTA MOR expression. It is possible that continuous social stress reduces cocaine reward and VTA BDNF expression as a function of downregulated VTA MOR expression, which would suggest that VTA MORs may mediate a switch between the sensitizing effects seen with intermittent social stress and the suppressed cocaine reward observed after continuous social stress.

The nucleus accumbens (NAc), with reciprocal projections to the VTA, has also been identified as a brain region crucial for the effects of stress, drugs of abuse, and food intake/palatability. Since VTA MOR knockdown likely functioned in the present study to block stress-induced increase of dopaminergic tone, this manipulation also might prevent stress-induced changes in the NAc. Future studies are needed to determine whether VTA MOR knockdown alters stress-induced changes in the NAc, and the importance of NAc neurotransmission for stress-induced effects associated with the VTA.

In conclusion, our results indicate that social stress exposure increases VTA MOR activity, potentially disinhibiting VTA dopaminergic tone to facilitate response to drugs of abuse. The present data suggest that upregulation of VTA MORs following social stress exposure may underlie vulnerability to psychostimulant drugs in some individuals, thereby providing a potential target for therapeutic intervention during abuse of these drugs.

Highlights.

VTA MORs are necessary for social stress-induced weight gain and behavior deficits

VTA MOR knockdown prevented cross-sensitization to amphetamine after social defeat

VTA MOR knockdown prevented social stress-induced increase of VTA BDNF

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by USPHS awards DA026451 (EMN), MH073930 (RPH), and AA016654 (AWL). The authors would like to thank the NIDA Drug Supply Program for providing [3H]DAMGO and naloxone, and we declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- [3H]DAMGO

tritiated [D-Ala2,N-MePhe4,Gly-ol5] enkephalin

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CREB

cAMP responsive binding element protein

- DA

dopamine

- fr

fasciculus retroflexus

- GABA

gamma-aminobutyric acid

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- MOR

mu-opioid receptor

- ml

medial lemniscus

- MT

medial terminal nucleus of the accessory optic system

- pCREB

phosphorylated cAMP responsive binding element protein

- shMOR

short hairpin mu-opioid receptor lentiviral construct

- SNc

substantia nigra pars compacta

- SNr

substantia nigra pars reticulata

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Badiani A, Leone P, Noel MB, Stewart J. Ventral tegmental area opioid mechanisms and modulation of ingestive behavior. Brain Res. 1995;670:264–276. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01281-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergevin A, Girardot D, Bourque MJ, Trudeau LE. Presynaptic mu-opioid receptors regulate a late step of the secretory process in rat ventral tegmental area GABAergic neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42:1065–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berton O, McClung CA, Dileone RJ, Krishnan V, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Graham D, Tsankova NM, Bolanos CA, Rios M, Monteggia LM, Self DW, Nestler EJ. Essential role of BDNF in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in social defeat stress. Science. 2006;311:864–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1120972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolanos CA, Nestler EJ. Neurotrophic mechanisms in drug addiction. Neuromolecular Med. 2004;5:69–83. doi: 10.1385/NMM:5:1:069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu NN, Zuo YF, Meng L, Lee DY, Han JS, Cui CL. Peripheral electrical stimulation reversed the cell size reduction and increased BDNF level in the ventral tegmental area in chronic morphine-treated rats. Brain Res. 2007;1182:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corominas M, Roncero C, Ribases M, Castells X, Casas M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its intracellular signaling pathways in cocaine addiction. Neuropsychobiology. 2007;55:2–13. doi: 10.1159/000103570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council NR. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8. The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington HE, 3rd, Maze I, Sun H, Bomze Howard M, DeMaio Kristine D, Wu Emma Y, Dietz David M, Lobo Mary K, Ghose S, Mouzon E, Neve Rachael L, Tamminga Carol A, Nestler Eric J. A role for repressive histone methylation in cocaine-induced vulnerability to stress. Neuron. 2011;71:656–670. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington HE, 3rd, Miczek KA. Repeated social-defeat stress, cocaine or morphine. Effects on behavioral sensitization and intravenous cocaine self-administration “binges”. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:388–398. doi: 10.1007/s002130100858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacher M, Nugent FS. Opiates and plasticity. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:1088–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanous S, Hammer RP, Jr, Nikulina EM. Short-and long-term effects of intermittent social defeat stress on brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in mesocorticolimbic brain regions. Neuroscience. 2010;167:598–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanous S, Lacagnina MJ, Nikulina EM, Hammer RP., Jr Sensitized activation of Fos and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the medial prefrontal cortex and ventral tegmental area accompanies behavioral sensitization to amphetamine. Neuropharmacology. 2011a;61:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanous S, Terwilliger EF, Hammer RP, Jr, Nikulina EM. Viral depletion of VTA BDNF in rats modulates social behavior, consequences of intermittent social defeat stress, and long-term weight regulation. Neurosci Lett. 2011b;502:192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall CM, Gold SJ, Isackson PJ, Seroogy KB. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3 mRNAs are expressed in ventral midbrain regions containing dopaminergic neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1992;3:56–63. doi: 10.1016/1044-7431(92)90009-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon M, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural localization of enkephalin and mu-opioid receptors in the rat ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience. 2002;114:461–474. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00249-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Russo PV, Segal DS, Kuczenski R. Effects of apomorphine and amphetamine on patterns of locomotor and investigatory behavior in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1987;28:393–399. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(87)90460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm JW, Lu L, Hayashi T, Hope BT, Su TP, Shaham Y. Time-dependent increases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein levels within the mesolimbic dopamine system after withdrawal from cocaine: Implications for incubation of cocaine craving. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:742–747. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00742.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W, Hata H, Imbe H, Liu QR, Takamatsu Y, Koizumi M, Murphy NP, Senba E, Uhl GR, Sora I, Ikeda K. Increased body weight in mice lacking mu-opioid receptors. NeuroReport. 2006;17:941–944. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000221829.87974.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Pert C. Light microscopic localization of brain opiate receptors: a general autoradiographic method which preserves tissue quality. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1982;2:1129–1149. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-08-01129.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horger BA, Iyasere CA, Berhow MT, Messer CJ, Nestler EJ, Taylor JR. Enhancement of locomotor activity and conditioned reward to cocaine by brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4110–4122. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-04110.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SW, North RA. Opioids excite dopamine neurons by hyperpolarization of local interneurons. J Neurosci. 1992;12:483–488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00483.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu H, Ohara A, Sasaki K, Abe H, Hattori H, Hall FS, Uhl GR, Sora I. Decreased response to social defeat stress in mu-opioid-receptor knockout mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99:676–682. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo JW, Mazei-Robison MS, Chaudhury D, Juarez B, LaPlant Q, Ferguson D, Feng J, Sun H, Scobie KN, Damez-Werno D, Crumiller M, Ohnishi YN, Ohnishi YH, Mouzon E, Dietz DM, Lobo MK, Neve RL, Russo SJ, Han MH, Nestler EJ. BDNF Is a Negative Modulator of Morphine Action. Science. 2012;338:124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.1222265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan V, Han MH, Graham DL, Berton O, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Laplant Q, Graham A, Lutter M, Lagace DC, Ghose S, Reister R, Tannous P, Green TA, Neve RL, Chakravarty S, Kumar A, Eisch AJ, Self DW, Lee FS, Tamminga CA, Cooper DC, Gershenfeld HK, Nestler EJ. Molecular adaptations underlying susceptibility and resistance to social defeat in brain reward regions. Cell. 2007;131:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasek AW, Janak PH, He L, Whistler JL, Heberlein U. Downregulation of mu opioid receptor by RNA interference in the ventral tegmental area reduces ethanol consumption in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:728–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Koya E, Zhai H, Hope BT, Shaham Y. Role of ERK in cocaine addiction. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:695–703. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz PE, Kieffer BL. The multiple facets of opioid receptor function: implications for addiction. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013a;23:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz PE, Kieffer BL. Opioid receptors: distinct roles in mood disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2013b;36:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald AF, Billington CJ, Levine AS. Alterations in food intake by opioid and dopamine signaling pathways between the ventral tegmental area and the shell of the nucleus accumbens. Brain Res. 2004;1018:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magendzo K, Bustos G. Expression of amphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization after short-and long-term withdrawal periods: participation of mu-and delta-opioid receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:468–477. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathon DS, Lesscher HM, Gerrits MA, Kamal A, Pintar JE, Schuller AG, Spruijt BM, Burbach JP, Smidt MP, van Ree JM, Ramakers GM. Increased gabaergic input to ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons associated with decreased cocaine reinforcement in mu-opioid receptor knockout mice. Neuroscience. 2005;130:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerlo P, Overkamp GJ, Daan S, Van Den Hoofdakker RH, Koolhaas JM. Changes in behaviour and body weight following a single or double social defeat in rats. Stress. 1996;1:21–32. doi: 10.3109/10253899609001093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, Nikulina EM, Shimamoto A, Covington HE., 3rd Escalated or suppressed cocaine reward, tegmental BDNF, and accumbal dopamine caused by episodic versus continuous social stress in rats. J Neurosci. 2011a;31:9848–9857. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0637-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miczek KA, Nikulina EM, Takahashi A, Covington HE, 3rd, Yap JJ, Boyson CO, Shimamoto A, de Almeida RM. Gene expression in aminergic and peptidergic cells during aggression and defeat: relevance to violence, depression and drug abuse. Behav Genet. 2011b;41:787–802. doi: 10.1007/s10519-011-9462-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan PJ, Bullmore ET. From taste hedonics to motivational drive: central mu-opioid receptors and binge-eating behaviour. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:995–1008. doi: 10.1017/S146114570900039X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikulina EM, Arrillaga-Romany I, Miczek KA, Hammer RP., Jr Long-lasting alteration in mesocorticolimbic structures after repeated social defeat stress in rats: time course of mu-opioid receptor mRNA and FosB/DeltaFosB immunoreactivity. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:2272–2284. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikulina EM, Covington HE, 3rd, Ganschow L, Hammer RP, Jr, Miczek KA. Long-term behavioral and neuronal cross-sensitization to amphetamine induced by repeated brief social defeat stress: Fos in the ventral tegmental area and amygdala. Neuroscience. 2004;123:857–865. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikulina EM, Hammer RP, Jr, Miczek KA, Kream RM. Social defeat stress increases expression of mu-opioid receptor mRNA in rat ventral tegmental area. NeuroReport. 1999;10:3015–3019. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199909290-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikulina EM, Lacagnina MJ, Fanous S, Wang J, Hammer RP., Jr Intermittent social defeat stress enhances mesocorticolimbic DeltaFosB/BDNF co-expression and persistently activates corticotegmental neurons: implication for vulnerability to psychostimulants. Neuroscience. 2012;212:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikulina EM, Miczek KA, Hammer RP., Jr Prolonged effects of repeated social defeat stress on mRNA expression and function of mu-opioid receptors in the ventral tegmental area of rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Elsevier Science; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pitchers KK, Coppens CM, Beloate LN, Fuller J, Van S, Frohmader KS, Laviolette SR, Lehman MN, Coolen LM. Endogenous opioid-induced neuroplasticity of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area influences natural and opiate reward. J Neurosci. 2014;34:8825–8836. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0133-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulliam JV, Dawaghreh AM, Alema-Mensah E, Plotsky PM. Social defeat stress produces prolonged alterations in acoustic startle and body weight gain in male Long Evans rats. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzoli M, Carboni L, Arban R. Alterations of behavioral and endocrinological reactivity induced by 3 brief social defeats in rats: relevance to human psychopathology. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1405–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X, Lutfy K, Mangubat M, Ferrini MG, Lee ML, Liu Y, Friedman TC. Alterations in phosphorylated CREB expression in different brain regions following short-and long-term morphine exposure: relationship to food intake. J Obes. 2013;2013:764742. doi: 10.1155/2013/764742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo SJ, Nestler EJ. The brain reward circuitry in mood disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:609–625. doi: 10.1038/nrn3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segall MA, Margules DL. Central mediation of naloxone-induced anorexia in the ventral tegmental area. Behav Neurosci. 1989;103:857–864. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.103.4.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seroogy KB, Lundgren KH, Tran TM, Guthrie KM, Isackson PJ, Gall CM. Dopaminergic neurons in rat ventral midbrain express brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3 mRNAs. J Comp Neurol. 1994;342:321–334. doi: 10.1002/cne.903420302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural relationships between terminals immunoreactive for enkephalin, GABA, or both transmitters in the rat ventral tegmental area. Brain Res. 1995;672:261–275. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01391-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh PB, Ghosh A. Molecular mechanisms underlying activity-dependent regulation of BDNF expression. Journal of Neurobiology. 1999;41:127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:343–359. doi: 10.1007/s002130100917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1141:105–130. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. New findings on biological factors predicting addiction relapse vulnerability. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2011;13:398–405. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0224-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MJ, Kalivas PW, Shaham Y. Neuroplasticity in the mesolimbic dopamine system and cocaine addiction. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:327–342. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidey JW, Miczek KA. Social defeat stress selectively alters mesocorticolimbic dopamine release: an in vivo microdialysis study. Brain Res. 1996;721:140–149. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trigo JM, Martin-Garcia E, Berrendero F, Robledo P, Maldonado R. The endogenous opioid system: a common substrate in drug addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ree JM, Niesink RJ, Van Wolfswinkel L, Ramsey NF, Kornet MM, Van Furth WR, Vanderschuren LJ, Gerrits MA, Van den Berg CL. Endogenous opioids and reward. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;405:89–101. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00544-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJ, Niesink RJ, Van Ree JM. The neurobiology of social play behavior in rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1997;21:309–326. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJ, Stein EA, Wiegant VM, Van Ree JM. Social isolation and social interaction alter regional brain opioid receptor binding in rats. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1995;5:119–127. doi: 10.1016/0924-977X(95)00010-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Perez H, Ting AKR, Walton CH, Hansen DM, Razavi R, Clarke L, Bufalino MR, Allison DW, Steffensen SC, van der Kooy D. Ventral tegmental area BDNF induces an opiate-dependent-like reward state in naive rats. Science. 2009;324:1732–1734. doi: 10.1126/science.1168501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venzala E, García-García AL, Elizalde N, Delagrange P, Tordera RM. Chronic social defeat stress model: behavioral features, antidepressant action, and interaction with biological risk factors. Psychopharmacology. 2012;224:313–325. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2754-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Fanous S, Terwilliger EF, Bass CE, Hammer RP, Jr, Nikulina EM. BDNF overexpression in the ventral tegmental area prolongs social defeat stress-induced cross-sensitization to amphetamine and increases deltaFosB expression in mesocorticolimbic regions of rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:2286–2296. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Torregrossa MM, Jutkiewicz EM, Shi YG, Rice KC, Woods JH, Watson SJ, Ko MC. Endogenous opioids upregulate brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA through delta-and mu-opioid receptors independent of antidepressant-like effects. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:984–994. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Hammer RP., Jr Gonadal steroid hormones upregulate medial preoptic μ-opioid receptors in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;278:271–274. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00175-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]