Abstract

Increasing evidence suggests that pre-metastatic niches, consisting mainly of myeloid cells, provide microenvironment critical for cancer cell recruitment and survival to facilitate metastasis. While CD8+ T cells exert immunosurveillance in primary human tumors, whether they can exert similar effects on myeloid cells in the pre-metastatic environment is unknown. Here, we show that CD8+ T cells are capable of constraining pre-metastatic myeloid cell accumulation by inducing myeloid cell apoptosis in C57BL/6 mice. Antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell cytotoxicity against myeloid cells in pre-metastatic lymph nodes is compromised by Stat3. We demonstrate here that Stat3 ablation in myeloid cells leads to CD8+ T-cell activation and increased levels of IFN-γ and granzyme B in the pre-metastatic environment. Furthermore, Stat3 negatively regulates soluble antigen cross-presentation by myeloid cells to CD8+ T cells in the pre-metastatic niche. Importantly, in tumor-free lymph nodes of melanoma patients, infiltration of activated CD8+ T cells inversely correlates with STAT3 activity, which is associated with a decrease in number of myeloid cells. Our study suggested a novel role for CD8+ T cells in constraining myeloid cell activity through direct killing in the pre-metastatic environment, and the therapeutic potential by targeting Stat3 in myeloid cells to improve CD8+ T-cell immunosurveillance against metastasis.

Keywords: Pre-metastatic myeloid cell accumulation, immunosurveillance, CTLs, Stat3

Introduction

Tumor metastasis is a major cause of death in cancer patients. The host immune system has close interactions with cancer cells, leading to both immunosurveillance as well as cancer-promoting inflammatory events [1, 2]. Recently, several studies have implicated the role of myeloid cells in conditioning potential organ sites of metastasis and allowing circulating tumor cells to colonize and form a metastasis [3-11]. Tumor-secreted factors can prime stromal cells in distant organ of the primary tumor, such as tumor-draining lymph nodes (TDLN) and lungs, resulting in the formation of newly induced or adapted pre-metastatic niches [4-8]. CD8+ T cells are important effectors for anti-tumor immunity that function by exerting direct and indirect cytotoxicity against cancer cells, in part by secreting immune regulators, such as interferon (IFN)-γ, and cytotoxic molecules that include granzyme B and perforin-1. Moreover, CD8+ T-cell infiltration in primary and metastatic tumors is associated with a favorable prognosis in multiple types of cancers [12, 13]. However, the role of CD8+ T cells in regulating myeloid cells in the premetastatic environment remains unexplored.

It is well recognized that Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) is a point of convergence for multiple signaling pathways activated by cytokines, growth factors, and many other factors in cancer cells [14, 15]. Persistently activated Stat3, in both primary and metastatic tumors and tumor-associated stromal cells, is crucial for cancer progression [16-20]. The tumor microenvironment can induce myeloid cell-mediated immunosuppression to facilitate immune evasion [21, 22], which is mediated in part by Stat3 activation in both tumor and immune cells [14, 15, 23]. Recently, it was shown that sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1)-Stat3 signaling in both tumor cells and myeloid cells is critical for the development of pre-metastatic niches by regulating the survival and colonization of myeloid cells at distant organ tissues of potential metastasis [8]. However, whether Stat3 in myeloid cells resists CD8+ T-cell-mediated immunosurveillance to allow myeloid cell accumulation in pre-metastatic tissue environments is unknown. In the current study, we investigated whether antigen-specific CD8+ T cells are able to constrain myeloid cell presence in the pre-metastatic tissue environment by direct killing of myeloid cells.

Results

CD8+ T cells constrain myeloid cell accumulation in pre-metastatic tissue, and is countered by Stat3

To locally induce the pre-metastatic environment in TDLNs, tumor conditioned medium (TCM) from B16-S1pr1 or MB49-S1pr1 cell lines [8] was injected daily into footpads of C57BL/6 background mice with or without Stat3 functional alleles in the myeloid compartment (i.e. Stat3flox/flox or Mx1-Cre/Stat3flox/flox).

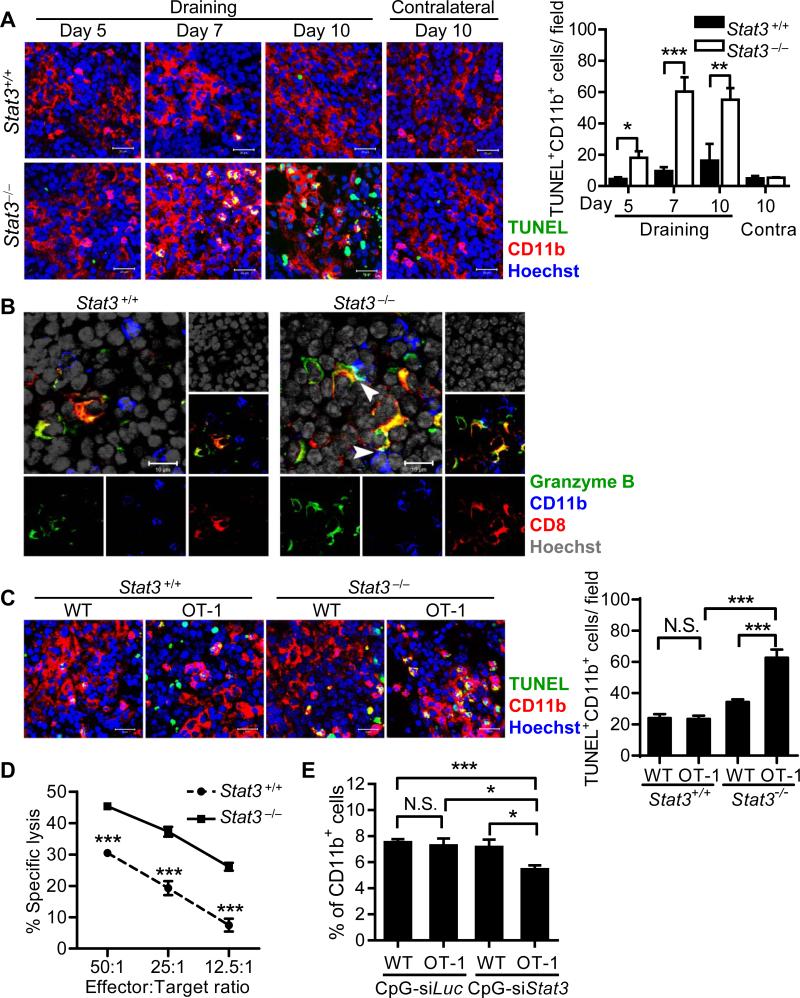

Western blot analysis demonstrated that B16-S1pr1 TCM induced Stat3 activation in CD11b+ myeloid cells in draining lymph nodes (LNs) (Supporting Information Fig. 1A). Injection of B16-S1pr1 tumor cells into footpads of mice following TCM treatment showed reduced TDLN metastasis after Stat3 ablation in the myeloid compartment (Supporting Information Fig. 1B and C), indicating an important role of myeloid cell Stat3 in the pre-metastatic environment of the TDLN and a regulatory role in metastasis. Although the CD11b+ myeloid cells percentage in the TDLNs were initially similar, a significant decrease was observed by flow cytometry in Stat3−/− mice compared with Stat3+/+ mice at day 10, using both the B16-S1pr1 and MB49-S1pr1 TCM models (Supporting Information Fig. 2). Immunofluorescence with a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) double-staining assay demonstrated a significant increase in apoptotic myeloid cells in the TDLNs of myeloid Stat3−/− mice at day 7 and 10 (Fig. 1A). This was not observed in TDLNs from myeloid Stat3+/+ mice. We further observed granzyme B-expressing CD8+ T cells in direct contact with CD11b+ myeloid cells in TDLNs from myeloid Stat3−/− mice at day 7 (Fig. 1B). Granzyme B was also localized within the intracellular regions of myeloid cells adjacent to the CD8+ T cells in contact (Fig. 1B). Importantly, depleting CD8+ T cells with anti-CD8 monoclonal antibodies reduced CD11b+ myeloid cell apoptosis, and restored their overall percentage in the pre-metastatic TDLNs in myeloid Stat3−/− mice (Supporting Information Fig. 3). These results suggested that CD8+ T cells may control the pre-metastatic myeloid cell population by inducing their apoptosis through direct cell cytotoxicity. However, elevated Stat3 activity in LN myeloid cells compromised the immunosurveillance exerted by CD8+ T cells.

Figure 1. CD8+ T cells constrain pre-metastatic myeloid cell accumulations, which is resisted by Stat3 in myeloid cells.

(A) Starting from day 1, 20 μL of concentrated B16-S1pr1 TCM was injected daily for 9 days into the forelimb footpads of C57BL/6 background mice with or without Stat3 ablation in myeloid cells. At the indicated times, draining and contralateral (contra) LNs were harvested and subjected to TUNEL and immunofluorescence double-labeling assay. The number of TUNEL+ CD11b+ cells per field were also quantified and shown as mean ± SEM of 6-10 images under 200× magnification from 4 mice per group from a single experiment representative of 3 independent experiments. Scale bars, 20 μm. (B) Immunofluorescence staining for granzyme B, CD11b and CD8 was performed using draining LNs at day 7 post-daily footpad injection of B16-S1pr1 TCM in the same mice described above. Arrowheads indicate CD8+ T cells and CD11b+ myeloid cells in contact. Note the cyan area located between CD8+ and CD11b+ cells showing overlapping of granzyme B and CD11b. Scale bars, 10 μm. Images are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) C57BL/6 background mice with or without myeloid Stat3 received footpad injection of B16-S1pr1 TCM with 50 μg of OVA protein on days 1 and 2 and then adoptive transfer of 107 of WT or OT-1 CD8+ T cells. Draining LNs were sampled at day 4 and TUNEL and immunofluorescence double-labeling assays were performed to assess myeloid cell apoptosis (n = 16–20 images taken under 200× magnification from 8 mice per group; representative of 2 independent experiments). Scale bars, 20 μm. The number of TUNEL+ CD11b+ cells per field were also quantified and shown as mean ± SEM of 16-20 images under 200× magnification from 8 mice per group from a single experiment representative of 2 independent experiments. (D) CD8+ T cells from OT-1 mice were assessed for specific cytotoxicity against SIINFEKL peptide-pulsed BMDMs with or without Stat3 in vitro by CFSE-based CTL assay. Each symbol shows mean±SEM of 3 samples representative of 3 independent experiments. (E) A CpG-Stat3 siRNA construct or a CpG-Luciferase siRNA control construct were injected into footpads of C57BL/6 mice at 0.39 nmol per dose on days 1 and 3. B16-S1pr1 TCM with 100 μg of OVA protein was injected in the same footpad on days 2 and 4. WT or OT-1 CD8+ T cells were labeled with CFSE and 107 cells were adoptively transferred to the mice at day 4 by i.v. injection. Mice were sacrificed on day 6 and the CD11b+ myeloid cell percentage in brachial LNs was measured by flow cytometry. Gating is shown in Supporting Information Fig. 8. Percentage of CD11b+ cells is shown as mean ± SEM of 12 samples pooled from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (Student's t-test).

Based on these observations, we hypothesized that tumor antigens in TCM, shed from tumor cells, were cross-presented by myeloid cells to CD8+ T cells in the pre-metastatic TDLN, leading to antigen-specific cytotoxicity against the myeloid cells. To test this hypothesis, we used ovalbumin (OVA) as a model antigen and injected TCM containing OVA protein into the footpads of Stat3flox/flox or Mx1-Cre/Stat3flox/flox mice once daily for two days. On the second day, the mice received adoptive transfer of CD8+ T cells from wild type (WT) or OT-1 mice. To avoid interference by cross-primed endogenous CD8+ T cells, we terminated the experiment 72 h after the first exposure to the model antigen. We chose this time point because the amount of cross-primed CD8+ T cells was limited [24], and there was little myeloid cell apoptosis in the TCM injection model (data not shown). Adoptive transfer of OT-1 CD8+ T cells significantly increased myeloid cell apoptosis in draining LNs from myeloid Stat3−/− mice compared with myeloid Stat3+/+ mice (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) without Stat3 exhibited higher sensitivity to antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell cytotoxicity in vitro (Fig. 1D). Notably, SIINFEKL peptide-MHC-I complexes on BMDMs with or without Stat3 were comparable (data not shown). These results suggested that the cytotoxicity against myeloid cells is contributed by antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, which can be inhibited by Stat3 activity in myeloid cells.

To test whether the myeloid cell resistance against cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) can be reversed by Stat3 silencing in vivo, C57BL/6 mice were treated with CpG-Stat3 siRNA or CpG-Luciferase siRNA constructs into the footpad, followed by injection of B16-S1pr1 TCM containing OVA protein every 48 h for 4 days and then followed by adoptive transfer of OT-1 or WT CD8+ T cells. The CpG-siRNA induced specific gene silencing in cells expressing Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9, mainly of myeloid cells and B cells, but not T cells [25]. The LNs were examined 4 days after the model antigen exposure, when Stat3 activity had not affected the percentage of myeloid cells in the TCM injection models (Supporting Information Fig. 2). Western blot analysis demonstrated inhibition of phosphorylated and total Stat3 by CpG-Stat3 siRNA 3 days after the last treatment (Supporting Information Fig. 4). Importantly, CD11b+ cells in the TCM-treated draining LNs were significantly decreased only in mice that received OT-1 CD8+ T cells and were treated with CpG-Stat3 siRNA (Fig. 1E). Collectively, these results suggested that antigen-specific CD8+ T cells can kill myeloid cells in an antigen model of induced pre-metastatic conditioned LNs, and that an effective immunosurveillance against myeloid cells in the pre-metastatic LN environment requires inhibition of Stat3 activity in myeloid cells.

Stat3 activity in myeloid cells blunts CD8+ T-cell functions in pre-metastatic LNs

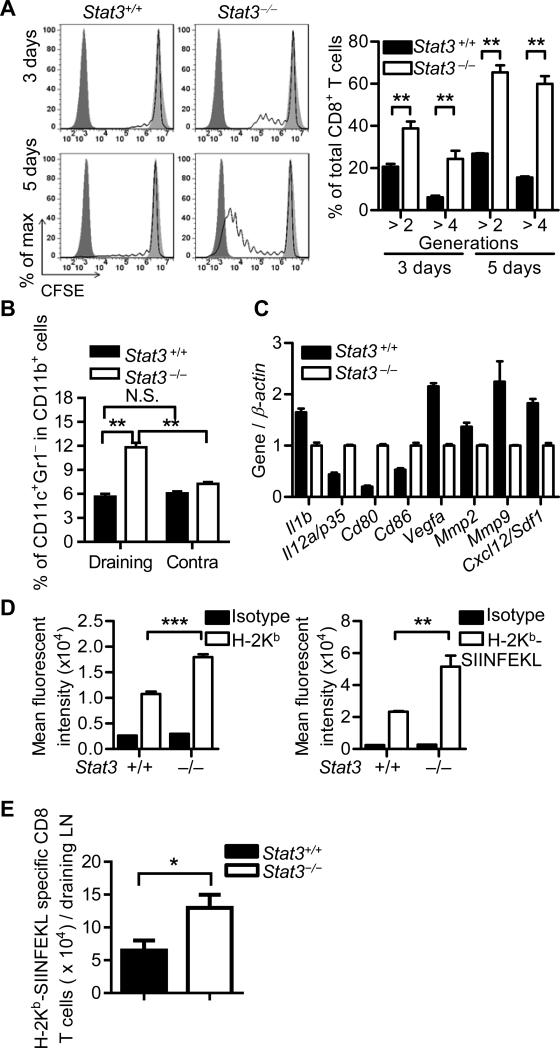

We next investigated whether Stat3 activity in the pre-metastatic LN myeloid cells has an impact on the functions of CD8+ T cells. After 5 days of B16-S1pr1 TCM exposure, CD8+ T cells in myeloid Stat3−/− (Mx1-Cre/Stat3flox/flox) mice showed significantly increased proportion of CD69+ cells (Fig. 2A) and IFN-γ production (Fig. 2B), which was specifically activated in the draining LNs. Similar results were observed in MB49-S1pr1 TCM model (Supporting Information Fig. 5A). Ifng, Gzmb and Pfr1 mRNA expression was significantly elevated in CD8+ T cells in myeloid Stat3−/− LNs compared with their counterparts in myeloid Stat3+/+ LNs (Fig. 2C). The results were confirmed by immunostaining for CD8+ and granzyme B, which showed strong co-localization of both markers in myeloid Stat3−/− LNs (Fig. 2D). There was an increase of overall granzyme B expression in draining LNs (Fig. 2E and Supporting Information Fig. 6).

Figure 2. Stat3 activity in myeloid cells blunts CD8+ T-cell functions in pre-metastatic LNs.

Starting from day 1, 20 μL of concentrated TCM was injected daily for 4 days into the forelimb footpads of C57BL/6 background mice with or without Stat3 ablation in myeloid cells. At day 5, draining and contralateral (contra) LNs were collected and digested. (A, B) Flow cytometry analysis was then performed to examine (A) CD69 (n = 6) and (B) IFN-γ expression in CD8+ lymphocytes (n = 5). Data are shown as mean ± SEM representative of 3 independent experiments. Gating was shown in Supporting Information Fig. 8. (C) Real-time PCR was used to detect differential regulation of functional genes in CD8+ T cells from the above experiment at day 5. Data show mean ± SEM of 3 samples from a single experiment representative of 2 independent experiments. (D) Immunofluorescence microscopy was used to detect expression of granzyme B in CD8+ T cells in draining LNs from the above experiment at day 5. Representative images taken under 200× magnification from 2 independent experiments were shown. Scale bars, 50 μm. (E) Granzyme B expression in draining LNs of mice described in (D) was quantitated and data are shown as mean ± SEM of positive area in 6 images taken under 100× magnification from 6 mice per group in a single experiment representative of 2 independent experiments. (F) A CpG-Stat3 siRNA construct or a CpG-Luciferase siRNA control construct were injected into footpads of C57BL/6 mice at 0.39 nmol per dose on days 1 and 3. B16-S1pr1 TCM with 100 μg of OVA protein was injected in the same footpads on days 2 and 4. WT or OT-1 CD8+ T cells were labeled with CFSE and 107 cells were adoptively transferred to the mice at day 4 by i.v. injection. Mice were sacrificed on day 6 and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD8+ T cells in draining LNs were measured by flow cytometry. Gating is shown in Supporting Information Fig. 8. MFIs are shown as mean ± SEM of 4 mice per group in a single experiment representative of 2 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (Student's t-test).

To confirm these findings, we silenced Stat3 in myeloid cells by CpG-Stat3 siRNA, which led to enhanced expression of IFN-γ in the adoptively transferred OT-1 CD8+ T cells in C57BL/6 mice treated with B16-S1pr1 TCM containing OVA protein (Fig. 2F). These findings demonstrated that Stat3 in myeloid cells can induce the dysfunction of T cells in TDLN prior to tumor metastasis.

Stat3 inhibits cross-presentation of soluble antigen in the pre-metastatic LN milieu

To assess the ability of myeloid cells to cross-present soluble antigens in TCM in vivo, B16-S1pr1 TCM-containing OVA protein was injected into the footpads of Stat3flox/flox or Mx1-Cre/Stat3flox/flox mice on C57BL/6 background. Stat3-ablated CD11b+ cells enriched from the draining LNs induced significantly stronger proliferation of OT-1 CD8+ T cells ex vivo than Stat3+/+ myeloid cells (Fig. 3A). In the B16-S1pr1 TCM injection model, there was an increase of CD11c+Gr-1– dendritic cells in total CD11b+ cells detected at day 5 in draining LNs from myeloid Stat3−/− mice compared with their contralateral LNs and LNs from Stat3+/+ control mice (Fig. 3B. We confirmed this finding using the MB49-S1pr1 TCM model (Supporting Information Fig. 5B). Real-time qPCR analysis of enriched CD11b+ cells from draining LNs indicated that Stat3 ablation improved the expression of co-stimulatory molecules required for efficient antigen presentation and reduced angiogenic and chemotactic factors known to promote tumor metastasis (Fig. 3C). In addition, Stat3 ablation increased the surface expression of MHC-I molecules and the potential to load specific peptide onto MHC-I molecules in peritoneal macrophages conditioned with TCM ex vivo (Fig. 3D). To further verify the effect of Stat3 on the cross presentation capacity of myeloid cells, we employed a mixture of OVA-expressing B16 (B16-OVA) tumor cell lysate and B16 TCM for footpad injection and investigated the cross-presentation of OVA in draining LNs. At day 7, MHC I-SIINFEKL complex-specific tetramer was utilized to detect SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells. We observed that the total number of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells was significantly increased in mice without myeloid Stat3 (Fig. 3E). These results demonstrated that cross-presentation of soluble antigens in the pre-metastatic LN milieu is inhibited by Stat3.

Figure 3. Stat3 inhibits soluble antigen cross-presentation in the pre-metastatic milieu.

(A) In C56BL/6 background mice with or without Stat3 ablation in the myeloid compartment, B16-S1pr1 TCM containing 100 μg OVA protein was injected into footpads daily for 3 days. CD11b+ cells were enriched from the draining brachial LNs and co-cultured ex vivo with CFSE-labeled OT-1 CD8+ T cells for 3 or 5 days. Flow cytometry was performed to determine OT-1 CD8+ T-cell proliferation. Gating was shown in Supporting Information Fig. 8. Dark filled line, bright filled line and unfilled line indicate CFSE-free OT-1 CD8+ T cells alone, CFSE-labeled OT-1 CD8+ T cells alone and CFSE-labeled OT-1 CD8+ T cells incubated with enriched CD11b+ cells, respectively. Graph shows mean ± SEM of 3 samples in a single experiment representative of 3 independent experiments. (B, C) 20 μL of concentrated TCM was injected daily for 4 consecutive days into the forelimb footpads of C57BL/6 background mice with or without Stat3 ablation in myeloid cells. At day 5, draining and contralateral (contra) LNs were collected and digested. Flow cytometry (B) was performed to determine percentages of CD11c+Gr-1– dendritic cells in total CD11b+ cells. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of 5 mice representative of 3 independent experiments. Gating strategies were shown in Supporting Information Fig. 8. qPCR (C) was performed to evaluate gene expression in draining LN CD11b+ cells in the B16-S1pr1 TCM model at day 5. Data show mean ± SEM of 3 mice representative of 2 independent experiments. (D) Flow cytometry was used to determine surface expression of MHC-I (left panel) and the ex vivo binding of SIINFEKL peptide to MHC-I (right panel) in peritoneal macrophages with or without Stat3 after TCM treatment. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of 4 mice from a single experiment representative of 3 independent experiments. (E) In C57BL/6 background mice with or without Stat3 ablation in the myeloid compartment, B16-S1pr1 TCM with 60 μg B16-OVA lysate was injected into footpads every day. At day 7, mice were sacrificed and MHC I-SIINFEKL tetramer (H-2Kb-SIINFEKL) was utilized to detect SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells in draining LNs by flow cytometry. Gating was shown in Supporting Information Fig. 8. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of 8 samples from a single experiment representative of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (Student's t-test).

Myeloid cell STAT3 and CD8+ T-cell activity in patient pre-metastatic LNs

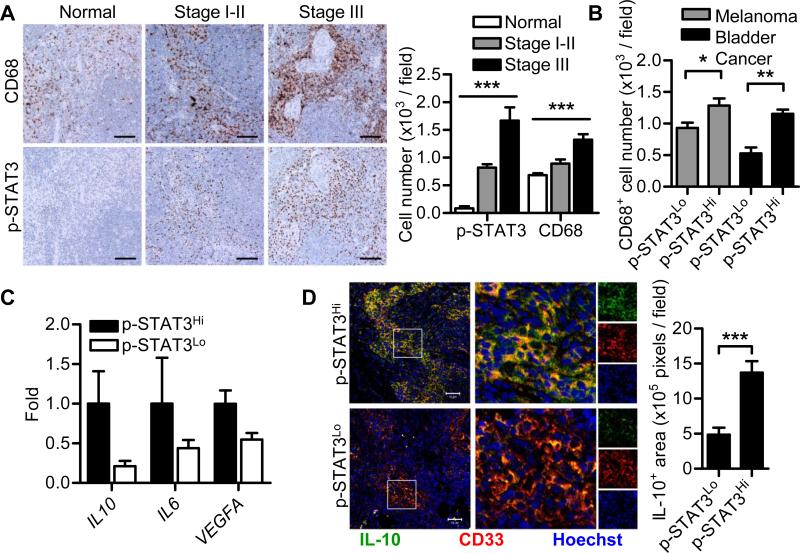

To validate our mouse studies in human cancers, uninvolved (histopathology metastasis negative) draining sentinel LNs of primary melanoma from melanoma patients and uninvolved draining pelvic LNs from bladder cancer patients were assessed. In melanoma patients, a sentinel LN is the first lymph node draining the site of a primary melanoma [26]. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining showed a dramatic increase in STAT3 activity and a significant increase in CD68+ myeloid cells in histopathology metastasis negative sentinel LNs in melanoma patients compared with normal human LNs (Fig. 4A). PSTAT3+ cells and CD68+ cells both increased with disease progression (Fig. 4A). Immunofluorescence staining showed that elevated STAT3 activity was detected in the myeloid cells (Supporting Information Fig. 7). In non-metastatic TDLN from both melanoma and bladder cancer patients, a positive correlation between STAT3 activity and CD68+ myeloid cell accumulation was observed (Fig. 4B). Elevated STAT3 activity was associated with an immunosuppressive microenvironment in the melanoma draining tumor-free sentinel LNs as determined by qPCR analysis (Fig. 4C). Immunostaining of melanoma tumor-free sentinel LNs revealed that high STAT3 activity was associated with increased IL-10 expression by myeloid cells (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. STAT3 activity correlates with myeloid cell abundance and immunosuppression in patient pre-metastatic LNs.

(A) Immunohistochemical staining was used to assess STAT3 activity and numbers of CD68+ myeloid cells in LNs from individuals without malignancy (n = 4) and uninvolved sentinel LNs from melanoma patients with AJCC stage I-III (n = 7 for each group, pooled from 2 independent experiments). Scale bars, 100 μm. Data in graph show cell number expressed as mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA) (B) Pre-metastatic LNs from melanoma patients and bladder cancer patients (n = 7 for each group, pooled from 2 independent experiments) were assessed for correlation between STAT3 activity and numbers of CD68+ myeloid cells by IHC. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. (C) qPCR was used to assess STAT3 regulation of several immunosuppressive genes in melanoma sentinel LNs. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of 5 samples from a single experiment representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) Immunofluorescent staining was used to assess IL-10 expression in myeloid cells in melanoma-uninvolved LNs. Inset boxes show magnified merged image, boxes on right show signal in each single channel. Scale bars, 50 μm. Graph shows mean ± SEM of 12 images from 4 patients per group, from a single experiment representative of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (Student's t-test).

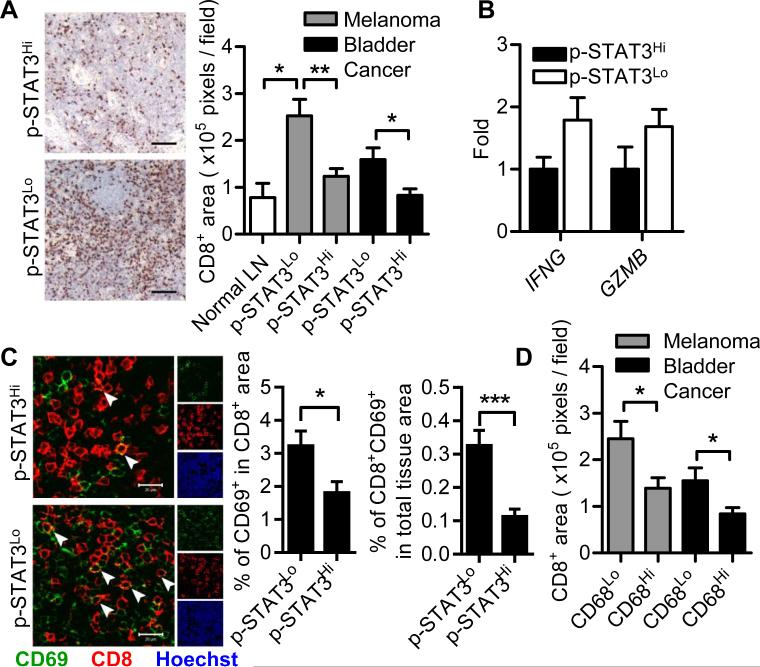

We next evaluated CD8+ T cells in these non-metastatic TDLNs. In both types of cancer patients, elevated STAT3 activity was associated with decreased CD8+ T-cell infiltration (Fig. 5A), as assessed by IHC. The expression of Th1-related genes, IFN-γ and granzyme B, was down-regulated in melanoma sentinel LNs with high STAT3 activity, indicating reduced Th1 immune responses (Fig. 5B). This was confirmed by the detection of impaired CD8+ T-cell activation using immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 5C). Importantly, CD8+ T-cell infiltration inversely correlated with CD68+ myeloid cells in these pre-metastatic LNs (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5. STAT3 activity inhibits CD8+ T-cell activities in patient pre-metastatic LNs.

(A) Immunohistochemical staining was used to assess numbers of CD8+ T cells in normal LNs (n = 4) and uninvolved tumor-draining LNs from melanoma patients and bladder cancer patients (n = 7 for each group). Representative images were from melanoma sentinel LNs. Scale bars, 100 μm. Graph shows mean ± SEM and data were representative of 2 independent experiments. (B) qPCR was performed to assess the regulation of Th1-related genes by STAT3 in melanoma sentinel LNs. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of 5 samples per group from a single experiment representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Immunofluorescence staining for CD69 and CD8α was used to visualize CD8+ T-cell activation in melanoma pre-metastatic LNs (n = 24 images from 6 patients per group). Arrowheads indicate CD69+CD8+ T cells. Boxes on right show percentages of activated CD8+ T cells in total CD8+ T cells and in whole tissue. Scale bars, 20 μm. Graph shows mean ± SEM and data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) The correlation between CD68+ myeloid cells and CD8+ T-cell infiltrates in pre-metastatic LNs was assessed by IHC. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of 7 samples per group representative of 2 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (Student's t-test).

Discussion

CD8+ T-cell infiltration at primary tumor sites correlates with favorable clinical outcomes in multiple types of cancer [12, 13, 27, 28]. Our results demonstrate an unrecognized role of CD8+ T cells in the pre-metastatic TDLNs: the T cells are capable of killing myeloid cells important for the successful colonization of metastatic tumor cells. Although a prior study showed that CD8+ T cells can be primed by DNA vaccine to kill tumor-associated macrophages at the primary tumor sites [29], our findings identify the importance of CD8+ T cells in pre-metastatic sites by controlling expansion of the myeloid population/clusters. Vα24-invariant natural killer T cells are also capable of killing tumor-associated macrophages, but in a CD1d-dependent manner [30]. In a non-tumor LN environment, CD8+ T cell-mediated elimination of antigen-presenting dendritic cells has been reported [31, 32]. In addition, it has been documented that Stat3 activity in antigen-presenting cells inhibits antigen-presentation and T-cell functions in the tumor microenvironment [19, 33, 34]. However, these earlier studies do not address whether CD8+ T cells can also constrain the accumulation of myeloid cells in the pre-metastatic environment by direct antigen-specific cytotoxicity against the myeloid cells.

One potential weakness in our study is the lack of a negative medium control – the effects of concentrated empty medium. Nevertheless, our prior experiments, including published data, suggest that concentrated empty media are not likely to affect draining LN in terms of CD8+ T-cell activation and myeloid cell accumulation [8]. Furthermore, since all the molecules in empty media are smaller than 3 kDa - the molecular weight cut-off for the column used for concentration, “concentrated” empty media should in theory be identical with un-concentrated empty media.

Priming of CD8+ T cells specific for soluble antigens requires cross-presentation, which is also necessary for the development of cellular immunity against tumors [35]. Cross-presentation of soluble antigens is maximal in TDLNs [36]. However, immune responses are often suppressed in TDLNs, limiting anti-tumor immunity, due to the powerful influence by tumor-derived factors [37]. Our data indicates that Stat3 activity inhibits cross-presentation of soluble antigens in the pre-metastatic LN milieu in vivo; this includes tumor-associated antigens shed from primary tumors through the tumor draining lymphatic vessels, impairing cross-priming of CTLs and reducing tumor cell immunosurveillance.

Recent studies from our group show an increase in myeloid cells and p-STAT3 level in pre-metastatic LNs from patients with melanoma, prostate cancer or non-small cell lung cancer compared with normal LNs [8, 38]. However, these studies did not address whether CD8+ T cells can constrain myeloid cells in pre-metastatic environment. Results from the current study using specimens from melanoma patients and bladder cancer patients suggest that CD8+ T-cell infiltration and activity are inversely correlated with p-STAT3. Furthermore, STAT3 activity in LN myeloid cells increased with melanoma disease progression. It is therefore plausible that as disease progresses, myeloid cells with highly activated STAT3 may serve as a checkpoint to suppress T-cell mediated immunosurveillance. This would suggest that the presence of these myeloid cells may promote successful colonization by metastatic tumor cells in TDLN. However, the current studies using human tumor tissues do not directly show CD8+ T cells can kill myeloid cells when myeloid cell STAT3 activity is low. In addition, our current study does not address whether CD11b+/Ly6C/Ly6G myeloid cells, which have been previously shown to be important for pre-metastatic niche [5, 11], are affected by CD8+ T cells. Studies to characterize in more details the myeloid cell population such as CD11b+/Ly6C/Ly6G in LN pre-metastatic niche formation are highly desirable. Nevertheless, our study demonstrates that in vivo silencing of Stat3 in CD11b+ myeloid cells using CpG-Stat3 siRNA combined with adoptive transfer of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells reduces myeloid cells in pre-metastatic LNs. Our study suggests the therapeutic potential by targeting Stat3 in myeloid cells in the pre-metastatic LN sites to improve CD8+ T-cell immunosurveillance against metastasis.

Methods

Cell culture

Generation of S1pr1-overexpressing B16 murine melanoma and MB49 murine bladder cancer cell lines was reported previously [8]. Murine primary peritoneal macrophages were isolated by lavage of peritoneum followed by adhesion to petri dishes and washing with HBSS−/−. BMDMs were generated by differentiation of bone marrow cells with 10% conditioned medium of L929 murine fibroblasts (American Type Culture Collection) for 6 days with medium replaced every 2-3 days. B16-S1pr1 cells, murine primary peritoneal macrophages and BMDMs were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). MB49-S1pr1 cells and L929 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS.

Preparation of tumor conditioned medium (TCM)

B16-S1pr1 or MB49-S1pr1 cells were grown to approximately 80% confluency and cultured in serum-free medium for an additional 24 h. TCM was collected and filtered through 0.22 μm surfactant-free cellulose acetate filter unit (Corning). Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (Millipore) with molecular weight cut-off at 3 kDa were used to concentrate the TCM about 15-fold for footpad injections. Concentrated TCM was only used for in vivo experiments, while original unconcentrated TCM was used for ex vivo and in vitro experiments.

Mice and footpad injection model

Mouse care and experimental procedures were performed under specific pathogen-free conditions in accordance with established institutional guidance and approved protocols from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Beckman Research Institute at City of Hope Medical Center. Generation of mice with Stat3 ablation in hematopoietic cells by inducible Mx1-Cre recombinase system has been reported [19]. Poly (I:C) was injected into Mx1-Cre/Stat3flox/flox mice to induce Stat3 deletion in the myeloid compartment. OT-1 mice were used as donors of CD8+ T cells with TCR specific for H-2Kb-restricted OVA epitope, SIINFEKL. The footpad injection model was adopted to assess the impact of tumor secreted factors in TCM on the draining LNs. Up to 20 μl of concentrated TCM was injected into the forelimb footpads every day. At indicated times, brachial LNs were harvested for further investigation.

In vivo depletion of CD8+ T cells

Anti-mouse CD8α monoclonal antibody (clone 53-6.72) and isotype control rat IgG2a (BioXcell) were used in the study. Three days before TCM injection, mice were given CD8α antibody (0.1 mg / mouse) or rat IgG2a control (0.1 mg / mouse) via i.p. injection for 3 consecutive days. Antibody or IgG2a injection was repeated at day 5 after initiation of TCM treatment. The in vivo depletion of CD8+ T cells was confirmed as ≥ 98% by determining the percentage of CD8+ T cells in TDLNs by flow cytometry.

Tissue digestion and cell enrichment

LNs and spleens were digested with Collagenase D and DNase I followed by mechanical dispersion. Cell suspension was used for either flow cytometry or specific cell subset enrichment. For adoptive transfer, CD8+ T cells from spleens of OT-1 or WT mice were enriched with MACS separation columns and anti-FITC microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). For other purposes, cell enrichment was performed with an EasySep isolation kit (StemCell Technologies).

Immunostaining and TUNEL assay

For immunohistochemistry, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections were deparaffinized, followed by antigen-retrieval with high-pH antigen retrieval solution (Vector Labs) and stained with antibodies against phospho-STAT3 (p-STAT3, Tyr705, Cell Signaling), human CD68 (AbD Serotec) or human CD8 (Spring Bioscience). ABC elite kit and 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (Vector Labs) were used according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantification was performed by acquiring images of 8 random fields per sample under 100 × magnifications with Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U microscope, followed by analysis with Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics). For immunofluorescence, frozen sections or FFPE sections after antigen retrieval were stained with antibodies for p-STAT3 (Tyr705, Cell Signaling), green fluorescent protein (GFP, Santa Cruz), mouse CD11b (BD Pharmingen), mouse CD8 (Biolegend), mouse granzyme B (Santa Cruz), human CD33 (Leica), human interleukin (IL)-10 (AbD Serotec), human CD8 (Spring Bioscience) or human CD69 (Leica), followed by incubation with Alexa555-labeled goat anti-rat IgG, Alexa647-labeled goat anti-rat IgG, Alexa488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG, Alexa555-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG and/or Alexa555-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) with Hoechest 33342. Immunofluorescent staining for p-STAT3 and IL-10 were amplified with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG and biotinylated goat anti-rat IgG (Vector Labs) after primary antibodies, respectively, followed by DyLight488-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch). For TUNEL and immunofluorescence double-labeling assay, frozen sections were stained for CD11b and followed by staining with DeadEnd fluorometric TUNEL system (Promega) to visualize apoptotic cells. Images were captured with a Zeiss LSM510 upright or inverted confocal microscope. Quantification was performed with LSM510 software (Zeiss) and Image-Pro Plus software.

Western blotting

Equal amounts of lysate proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted with antibodies to p-STAT3 (Tyr705, Cell Signaling), total STAT3 (Santa Cruz) and β-actin (Sigma) and detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce).

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with combinations of fluorophore-conjugated antibodies against CD11b, CD11c, CD69, CD8, H-2Kb, H-2Kb-SIINFEKL complex (Biolegend), Gr-1 and IFN-γ (BD). For intracellular staining of IFN-γ, cells were incubated for 4 h at the presence of Leukocyte Activation Cocktail (BD), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with BD Perm/Wash buffer, followed by IFN-γ antibody staining. For H-2Kb-SIINFEKL Tetramer staining, cells were incubated at 4°C for 1 h. Alexa 488-labeled H-2Kb - SIINFEKL Tetramer was kindly provided by the NIH Tetramer Core at Emory University (Atlanta, GA, USA). Data were collected with a CyAn flow cytometer (Dako) or an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star). Gating strategies were shown in Supporting Information Fig. 8.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

RNA was isolated from viable mouse cells or FFPE sections of patient LNs with RNAqueous-Micro kit or RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation kit (Invitrogen), respectively, and reverse transcribed with iScript cDNA sythesis kit (Bio-Rad). Primers for mouse cDNA detection were purchased from SABiosciences. Primer pairs for detection of human cDNA from FFPE sections were designed as follows to ensure small amplicons around 80 bases [39]: IFNG: 5’-GAGATGACTTCGAAAAGCTGAC-3’ (forward) and 5’-CACTTGGATGAGTTCATGTATTGC-3’ (reverse); IL10: 5’-TGCCTAACATGCTTCGAGATC-3’ (forward) and 5’-GTTGTCCAGCTGATCCTTCA-3’ (reverse); IL6: 5’-GTACATCCTCGACGGCATC-3’ (forward) and 5’-CCTCTTTGCTGCTTTCACAC-3’ (reverse); VEGFA: 5’-AGGGCAGAATCATCACGAAG-3’ (forward) and 5’-GGTCTCGATTGGATGGCAG-3’ (reverse); GZMB: 5’-GTGGCTTCCTGATACGAGAC-3’ (forward) and 5’-CCCCAAGGTGACATTTATGGAG-3’ (reverse); ACTB: 5’-GCGAGAAGATGACCCAGATC-3’ (forward) and 5’-GATAGCACAGCCTGGATAGC-3’ (reverse); GAPDH: 5’-GGAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAG-3’ (forward) and 5’-ACCAGAGTTAAAAGCAGCCC-3’ (reverse); 18SrRNA: 5’-CCGCAGCTAGGAATAATGGA-3’ (forward) and 5’-CCCTCTTAATCATGGCCTCA-3’ (reverse). Gene expression data from FFPE human tissues were normalized to geometric mean of ACTB, GAPDH and 18SrRNA [40].

T-cell proliferation assay

B16-S1pr1 TCM with 100 μg of OVA protein (Sigma) was injected into the forelimb footpad daily for 3 consecutive days. CD11b+ cells were enriched from the draining brachial LNs and co-cultured with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled (Invitrogen) OT-1 CD8+ T cells at a ratio of 1:3 for 72 h or 120 h. CFSE signal was detected by flow cytometry to assess the proliferation of CFSE+ SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells.

SIINFEKL peptide binding assay

Murine primary peritoneal macrophages or BMDMs were conditioned with 10% B16-S1pr1 TCM for 24 h and incubated with 2 μg/ml SIINFEKL peptide (InvivoGen) for 1.5 h at 37 °C. Cells were stained with an antibody specific for H-2Kb-SIINFEKL complex or an isotype control and analyzed using a flow cytometer.

Tumor lysate preparation

OVA expressing B16 (B16-OVA) cells were used for tumor lysate preparation. Upon 100% confluency, tumor cells were treated with 10 mM EDTA for 30 minutes. All cells were collected and subjected to 6 cycles of frozen-thaw in liquid nitrogen and 37°C water bath. After centrifuge at 400× g for 5 minutes, all the insoluble cell parts were discarded. Protein content in the supernatant was determined using the Bradford reagent.

In vivo cross-presentation assay

For the in vivo cross-presentation assay, a mixture of B16-S1pr1 TCM and 60 μg OVA-expressing B16 (B16-OVA) tumor cell lysate were injected into mouse footpad for 7 consecutive days. MHC I-SIINFEKL complex-specific tetramer (H-2Kb-SIINFEKL Tetramer) was used to detect SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells in draining LN as the readout for OVA cross-presentation.

In vitro CTL assay

BMDMs were incubated overnight in 10% B16-S1pr1 TCM and pulsed with SIINFEKL peptide as described above. Same numbers of peptide-pulsed and non-pulsed BMDMs were labeled with 0.5 μM and 0.05 μM CFSE, respectively, and mixed. The mixed target cells were incubated with CD8+ T cells from OT-1 mice at indicated ratios for 6 h at the presence of 10% B16-S1pr1 TCM. Flow cytometry was performed to evaluate specific cytotoxicity of target cells.

Adoptive transfer and in vivo CTL assay

For the in vivo CTL assay in mice with Stat3 ablation in the myeloid compartment, B16-S1pr1 TCM with 50 μg of OVA protein was injected into footpads on days 1 and 2. Ten millions of WT or OT-1 CD8+ T cells were adoptively transferred to the mice on day 2 by i.v. injection. Mice were sacrificed at day 4 and frozen sections of brachial LNs were prepared. For the in vivo CTL assay with CpG-siRNA treatment, CpG-Stat3 siRNA construct or CpG-Luciferase siRNA control construct were injected into footpads of C57BL/6 mice at 0.39 nmol per dose on days 1 and 3. B16-S1pr1 TCM with 100 μg of OVA protein was injected in the same footpad on days 2 and 4. WT or OT-1 CD8+ T cells were labeled with CFSE and 107 cells were adoptively transferred to the mice at day 4 by i.v. injection. Mice were sacrificed on day 6 and the CD11b+ myeloid cell percentage in brachial LNs was measured by flow cytometry.

Human LN tissue samples

Uninvolved melanoma sentinel LN specimens from Stage I, II and Stage III patients were kindly provided by John Wayne Cancer Institute, with approval from Western Institutional Review Board and patient consent. AJCC stage III melanoma patients have at least one involved LN but only uninvolved LNs were used for investigations in current study. Sentinel LN specimens with no histopathology metastatic disease from Stage I, II and III patients were used in the study. Uninvolved bladder cancer-draining pelvic LN specimens were obtained from City of Hope Biospecimen Repository with approval from City of Hope Institutional Review Board and patient consent. FFPE specimens were prepared as 4 μm sections for subsequent analysis. Human normal LN sections from four individuals without cancer were purchased from Abcam, GeneTex and Imgenex. The tissue sections were examined and diagnosed by a certified pathologist.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between two groups were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. The impact of disease stage on myeloid cells and p-STAT3 was estimated with Oneway ANOVA. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Brian Armstrong, Ph.D., Lucy Brown, M.S. and other staff members of Light Microscopy Imaging Core, Analytical Flow Cytometry Core, Pathology Core and Animal Facility Core at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center for their technical assistance. We also acknowledge Kelly Chong, B.Sc. from Department of Molecular Oncology at John Wayne Cancer Institute for assisting patient specimen transfer. We also thank Billy and L. Audrey Wilder Endowment to HY. Research reported in this publication is funded in part by R01CA122976, R01CA146092 and P50CA107399, as well as by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P30CA033572. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- BMDM

bone marrow derived macrophage

- CFSE

carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FFPE

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- IFN

interferon

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- LN

lymph node

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- NIH

National Institute of Health

- OVA

ovalbumin

- S1PR1

sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1

- Stat3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- TCM

tumor conditioned medium

- TDLN

tumor draining lymph node

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors disclose no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Trinchieri G. Cancer and inflammation: an old intuition with rapidly evolving new concepts. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:677–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331:1565–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hiratsuka S, Watanabe A, Aburatani H, Maru Y. Tumour-mediated upregulation of chemoattractants and recruitment of myeloid cells predetermines lung metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1369–1375. doi: 10.1038/ncb1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, Bramley AH, Vincent L, Costa C, MacDonald DD, Jin DK, Shido K, Kerns SA, Zhu Z, Hicklin D, Wu Y, Port JL, Altorki N, Port ER, Ruggero D, Shmelkov SV, Jensen KK, Rafii S, Lyden D. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820–827. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kowanetz M, Wu X, Lee J, Tan M, Hagenbeek T, Qu X, Yu L, Ross J, Korsisaari N, Cao T, Bou-Reslan H, Kallop D, Weimer R, Ludlam MJ, Kaminker JS, Modrusan Z, van Bruggen N, Peale FV, Carano R, Meng YG, Ferrara N. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor promotes lung metastasis through mobilization of Ly6G+Ly6C+ granulocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21248–21255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015855107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim S, Takahashi H, Lin WW, Descargues P, Grivennikov S, Kim Y, Luo JL, Karin M. Carcinoma-produced factors activate myeloid cells through TLR2 to stimulate metastasis. Nature. 2009;457:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature07623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Cox TR, Lang G, Bird D, Koong A, Le QT, Giaccia AJ. Hypoxia-induced lysyl oxidase is a critical mediator of bone marrow cell recruitment to form the premetastatic niche. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng J, Liu Y, Lee H, Herrmann A, Zhang W, Zhang C, Shen S, Priceman SJ, Kujawski M, Pal SK, Raubitschek A, Hoon DS, Forman S, Figlin RA, Liu J, Jove R, Yu H. S1PR1-STAT3 signaling is crucial for myeloid cell colonization at future metastatic sites. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:642–654. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Psaila B, Lyden D. The metastatic niche: adapting the foreign soil. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:285–293. doi: 10.1038/nrc2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sceneay J, Smyth MJ, Moller A. The pre-metastatic niche: finding common ground. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10555-013-9420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sceneay J, Chow MT, Chen A, Halse HM, Wong CS, Andrews DM, Sloan EK, Parker BS, Bowtell DD, Smyth MJ, Moller A. Primary tumor hypoxia recruits CD11b+/Ly6Cmed/Ly6G+ immune suppressor cells and compromises NK cell cytotoxicity in the premetastatic niche. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3906–3911. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pages C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, Zinzindohoue F, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Pages F. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fridman WH, Pages F, Sautes-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nrc3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu H, Kortylewski M, Pardoll D. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:41–51. doi: 10.1038/nri1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:798–809. doi: 10.1038/nrc2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kujawski M, Kortylewski M, Lee H, Herrmann A, Kay H, Yu H. Stat3 mediates myeloid cell-dependent tumor angiogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3367–3377. doi: 10.1172/JCI35213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bromberg JF, Wrzeszczynska MH, Devgan G, Zhao Y, Pestell RG, Albanese C, Darnell JE., Jr. Stat3 as an oncogene. Cell. 1999;98:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee H, Deng J, Kujawski M, Yang C, Liu Y, Herrmann A, Kortylewski M, Horne D, Somlo G, Forman S, Jove R, Yu H. STAT3-induced S1PR1 expression is crucial for persistent STAT3 activation in tumors. Nat Med. 2010;16:1421–1428. doi: 10.1038/nm.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kortylewski M, Kujawski M, Wang T, Wei S, Zhang S, Pilon-Thomas S, Niu G, Kay H, Mule J, Kerr WG, Jove R, Pardoll D, Yu H. Inhibiting Stat3 signaling in the hematopoietic system elicits multicomponent antitumor immunity. Nat Med. 2005;11:1314–1321. doi: 10.1038/nm1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng F, Wang H, Horna P, Wang Z, Shah B, Sahakian E, Woan KV, Villagra A, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Sebti S, Smith M, Tao J, Sotomayor EM. Stat3 inhibition augments the immunogenicity of B-cell lymphoma cells, leading to effective antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4440–4448. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blankenstein T, Coulie PG, Gilboa E, Jaffee EM. The determinants of tumour immunogenicity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:307–313. doi: 10.1038/nrc3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:253–268. doi: 10.1038/nri3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murali-Krishna K, Altman JD, Suresh M, Sourdive DJ, Zajac AJ, Miller JD, Slansky J, Ahmed R. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity. 1998;8:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kortylewski M, Swiderski P, Herrmann A, Wang L, Kowolik C, Kujawski M, Lee H, Scuto A, Liu Y, Yang C, Deng J, Soifer HS, Raubitschek A, Forman S, Rossi JJ, Pardoll DM, Jove R, Yu H. In vivo delivery of siRNA to immune cells by conjugation to a TLR9 agonist enhances antitumor immune responses. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:925–932. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrell MI, Iritani BM, Ruddell A. Tumor-induced sentinel lymph node lymphangiogenesis and increased lymph flow precede melanoma metastasis. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:774–786. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma P, Shen Y, Wen S, Yamada S, Jungbluth AA, Gnjatic S, Bajorin DF, Reuter VE, Herr H, Old LJ, Sato E. CD8 tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are predictive of survival in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3967–3972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611618104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piras F, Colombari R, Minerba L, Murtas D, Floris C, Maxia C, Corbu A, Perra MT, Sirigu P. The predictive value of CD8, CD4, CD68, and human leukocyte antigen-D-related cells in the prognosis of cutaneous malignant melanoma with vertical growth phase. Cancer. 2005;104:1246–1254. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo Y, Zhou H, Krueger J, Kaplan C, Lee SH, Dolman C, Markowitz D, Wu W, Liu C, Reisfeld RA, Xiang R. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages as a novel strategy against breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2132–2141. doi: 10.1172/JCI27648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song L, Asgharzadeh S, Salo J, Engell K, Wu HW, Sposto R, Ara T, Silverman AM, DeClerck YA, Seeger RC, Metelitsa LS. Valpha24-invariant NKT cells mediate antitumor activity via killing of tumor-associated macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1524–1536. doi: 10.1172/JCI37869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hermans IF, Ritchie DS, Yang J, Roberts JM, Ronchese F. CD8+ T cell-dependent elimination of dendritic cells in vivo limits the induction of antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2000;164:3095–3101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guarda G, Hons M, Soriano SF, Huang AY, Polley R, Martin-Fontecha A, Stein JV, Germain RN, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. L-selectin-negative CCR7-effector and memory CD8+ T cells enter reactive lymph nodes and kill dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:743–752. doi: 10.1038/ni1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herrmann A, Kortylewski M, Kujawski M, Zhang C, Reckamp K, Armstrong B, Wang L, Kowolik C, Deng J, Figlin R, Yu H. Targeting Stat3 in the myeloid compartment drastically improves the in vivo antitumor functions of adoptively transferred T cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7455–7464. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brayer J, Cheng F, Wang H, Horna P, Vicente-Suarez I, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Sotomayor EM. Enhanced CD8 T cell cross-presentation by macrophages with targeted disruption of STAT3. Immunol Lett. 2010;131:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurts C, Robinson BW, Knolle PA. Cross-priming in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:403–414. doi: 10.1038/nri2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson D, Bundell C, Robinson B. In vivo cross-presentation of a soluble protein antigen: kinetics, distribution, and generation of effector CTL recognizing dominant and subdominant epitopes. J Immunol. 2000;165:6123–6132. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cochran AJ, Huang RR, Lee J, Itakura E, Leong SP, Essner R. Tumour-induced immune modulation of sentinel lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:659–670. doi: 10.1038/nri1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang W, Pal SK, Liu X, Yang C, Allahabadi S, Bhanji S, Figlin RA, Yu H, Reckamp KL. Myeloid clusters are associated with a prometastatic environment and poor prognosis in smoking-related early stage non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cronin M, Pho M, Dutta D, Stephans JC, Shak S, Kiefer MC, Esteban JM, Baker JB. Measurement of gene expression in archival paraffin-embedded tissues: development and performance of a 92-gene reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:35–42. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63093-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0034. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.