Abstract

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations are hypothesized to play a pathogenic role in aging and age-related neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease (PD). In support of this, high levels of somatic mtDNA mutations in “POLG mutator” mice carrying a proofreading-deficient form of mtDNA polymerase γ (PolgD257A) lead to a premature aging phenotype. However, the relevance of this finding to the normal aging process has been questioned as the number of mutations is greater even in young POLG mutator mice, which show no overt phenotype, than levels achieved during normal aging in mice. Vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) increases with age, and we hypothesized that this may result in part from the accumulation with age of somatic mtDNA mutations. If correct, then levels of mutations in young (2~3 month old) POLG mutator mice should be sufficient to increase vulnerability to MPTP. In contrast, we find that susceptibility to MPTP in both heterozygous and homozygous POLG mutator mice at this young age is not different from that of wild type littermate controls as measured by levels of tyrosine hydroxylase positive (TH+) striatal terminals, striatal dopamine and its metabolites, a marker of oxidative damage, or stereological counts of TH+ and total substantia nigra neurons. These unexpected results do not support the hypothesis that somatic mtDNA mutations contribute to the age-related vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons to MPTP. It remains possible that somatic mtDNA mutations influence vulnerability to other stressors, or require additional time for the deleterious consequences to manifest. Furthermore, the impact of the higher levels of mutations present at older ages in these mice was not assessed in our study, although a prior study also failed to detect an increase in vulnerability to MPTP in older mice. With these caveats, the current data do not provide evidence for a role of somatic mtDNA mutations in determining the vulnerability to MPTP.

Keywords: aging, Parkinson’s disease, mtDNA mutations, oxidative stress, neurodegeneration, tyrosine hydroxylase

1. Introduction

The mitochondrial theory of aging proposes that the accumulation with age of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations is a driving force of the aging process and contributes to age-related neurodegenerative diseases (Linnane et al., 1989). Support for this theory comes from studies of transgenic mice expressing a proofreading deficient mitochondrial polymerase gamma (POLG). Animals homozygous for this mutant POLG (designated POLG mut/mut mice) accumulate somatic mtDNA mutations at an accelerated rate, and develop a premature aging phenotype including weight loss, sarcopenia, reduced subcutaneous fat, kyphosis, osteoporosis, anemia, and decreased lifespan (Trifunovic et al., 2004; Kujoth et al., 2005). This mouse model demonstrates that high levels of somatic mtDNA mutations can contribute to features associated with aging. However, for at least 2 reasons, the relevance of these results to normal aging has been questioned. One reason is that levels of somatic mtDNA mutations associated with the premature aging phenotype in these mice are much higher than levels achieved during normal aging in mice. Homozygous POLG mut/mut mice show a delayed phenotype, with no obvious phenotype at young ages (2~3 month) despite already harboring mutation levels that are higher than seen in normal aged mice. Furthermore, heterozygous mutant POLG mice (designated POLG +/mut mice) show no “overt” phenotype at any age despite also having levels of somatic mtDNA mutations even at young ages that are higher than in normal aged mice (Vermulst et al., 2007). These data have been interpreted as evidence against a role for somatic mtDNA mutations during normal aging, although we recently reported that older POLG +/mut mice do indeed have metabolic deficits and decreased protein levels of mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes and complex IV activity in their brain (Dai et al., 2013). Moreover, POLG mut/mut mice also have decreased levels of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator (PGC-1α) associated with significant mtDNA depletion (Trifunovic et al. 2004; Safdar et al., 2011) and correspondingly show impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics with a profound reduction in expression of gene sets associated with mitochondrial function (Hiona et al., 2010; Safdar et al. 2011). PGC-1α deficient mice show increased vulnerability to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) (St-Pierre et al., 2006), whereas overexpressing PGC-1α in cell lines protects against an oxidative challenge and transgenic mice overexpressing PGC-1α in dopaminergic neurons are reported to have reduced vulnerability to MPTP (St-Pierre et al., 2006; Mudo et al., 2012).

We hypothesized that somatic mtDNA mutations could play a role during normal aging by increasing vulnerability to additional stressors, even if levels of mutations achieved during normal aging are insufficient on their own to cause a more obvious premature aging phenotype. If correct, then levels of mutations in both heterozygous and homozygous POLG mutator mice should be sufficient even at young ages to enhance vulnerability to such stressors.

To test this hypothesis, we assessed vulnerability to a mitochondrial toxin in heterozygous and homozygous POLG mutator mice at 2~3 months of age when mutation levels already are higher than those reached during normal aging (Vermulst et al. 2007). MPTP was selected as the toxin because vulnerability to this neurotoxin increases dramatically with age in mice (Ohashi et al., 2006). As a specific complex I inhibitor, MPTP treatment results in many deleterious consequences, including increased generation of free radical, exacerbated oxidative stress, and depletion in ATP production, which in turn leads to increased intracellular calcium concentration, excitotoxicity as well as nitric oxide related cellular damage. Moreover, MPTP causes enhanced dopamine release, which leads to further oxidative damage (Fiskum et al., 2003; Abou-Sleiman et al., 2006). MPTP also is of interest because it selectively damages dopaminergic neurons, and accidental human exposure to MPTP can cause clinical features similar to Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Langston et al., 1983; Langston 1996). We recently reported that substantia nigra (SN) neurons accumulate very high levels of somatic mtDNA mutations during early stages of PD, similar in some neurons to levels demonstrated to cause functional impairment in the POLG mut/mut mice (Lin et al., 2012). At older ages, POLG mut/mut mice demonstrate significant reductions in striatal dopaminergic terminals as well as deficits in motor function compared to wild type (WT) littermates (Dai et al. 2013). Thus, in addition to contributing to neuronal vulnerability to environmental stressors, somatic mtDNA mutations also may play a role in age-related neurodegenerative diseases such as PD.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals and MPTP injections

Transgenic mice (on C57BL/6J background) expressing a proofreading-deficient version of POLG were provided by Dr. Tomas A. Prolla (University of Wisconsin, Madison). The breeders, heterozygous mice (+/mut), were backcrossed 10~14 generations to C57BL/6J wild-type mice prior to sending to The Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). MPTP (purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.) was dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline (Hospia) to a final concentration of 3.3 mg/ml (calculated as free base). Mice injected subcutaneously with MPTP (20mg/kg) injection every other day for 9 days (5 injections) as previously reported (Clark et al., 2012). Mice were sacrificed by anesthetic overdose (Ketamine/Xylazine 200/20 mg/kg) seven days after the final MPTP or saline injection. All animal research was conducted in accordance with the regulatory policies of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of BIDMC.

2.2. Immunohistochemisty

Cryoprotected brains were cut on a freezing microtome and immunostained as previously described (Dai et al. 2013). Briefly, striatal sections were cut at 30 mm thickness and then immunostained with a primary mouse antibody against TH (1:1000; Sigma, Cat. T1299) and a Mouse on Mouse (M.O.M) Biotinylated Anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:250; Vector Labs). Digital images were quantitated using Axioskop microscope (Zeiss) with fixed exposure settings. Quantitative tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunohistochemistry was performed to determine levels of striatal TH depletion in POLG mice as previously reported (Dai et al. 2013). The density of striatal TH staining was determined from the mean pixel density (MPD) of digital images of stained sections. Images are digitally inverted so that higher MPDs correspond to higher staining intensities. The mean MPD of adjacent cortex in the same section was subtracted to control for background staining and unintended variation in section thickness. Analyses were conducted in a blinded manner.

2.3. Stereological neuronal counts

The midbrain sections were obtained using a freezing microtome and stained with an anti-TH antibody (1:1000; Sigma) for stereological cell counts in the SN. For the total SN neuronal counts, a subset of sections were counterstained with thionin. After mounting, each section was observed using a 2.5 × objective lens and an outline was drawn around each SN and overlaid with a 50×50 counting frame using Stereo Investigator software (MBF Biosciences). Thionin-stained neurons are identified by morphological criteria as well as presence of a visible nucleolus. The nuclei of each TH+ and thionin+/TH− neuron within the boundaries of the optical fractionator (X 120, Y 120, height 10 μm; with 2 μm guard zones) was counted. The total numbers of TH+ and TH− neurons per SN were then calculated by the optical fractionator software. This analysis was conducted in a blinded manner.

2.4. Measurements of dopamine and its metabolites

Levels of striatal dopamine and dopamine metabolites, homovanillic acid (HVA) and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), were measured in frozen striatal tissue via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) through the Neurochemistry Core Facility at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (https://medschool.vanderbilt.edu/vbi-core-labs/). Briefly, brain tissue was homogenized, using a tissue dismembrator, in 0.1M trichloroacetic acid, containing 10 mM sodium acetate, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5ng/ml isoproterenol (as internal standard) and 10.5 % methanol (pH 3.8). After centrifugation, the supernatant was analyzed by HPLC (Waters 515 pump with Waters 2707 autosampler, Waters Corp., Milford, MA USA) with electrochemical detection (Antec Decade II, Boston, MA USA). The HPLC was equipped with a Phenomenex Kinetex C18 HPLC column (100 × 4.60 mm, 2.6μm) and biogenic amines were eluted with a mobile phase consisting of 89.5% 0.1M TCA, 10 mM sodium acetate, 0.1 mM EDTA and 10.5% methanol (pH 3.8). Solvent is delivered at 0.6 ml/min.

2.5. Measurement of oxidative stress

Immunoblot detection of carbonyl groups that serve as a marker of oxidative damage to striatal proteins was performed using the OxyBlot Protein Oxidation Detection Kit (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For this assay, the carbonyl groups in the protein side chains are derivatized to 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone (DNP-hydrazone) by reaction with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH), and then the DNP-derivatized proteins are detected by Western blotting using a DNP-detecting primary antibody followed by a horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody. The amounts of oxidatively damaged proteins are determined by quantification of the signal intensity normalized to background using Image J. Lipid oxidative stress was assessed by measuring the levels of striatal malondialdehyde (MDA) using the Lipid Peroxidation Assay Kit (Abcam) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 200 μl tissue homogenates were reacted with 600 μl of Thiobarbituric Acid (TBA) solution at 95°C for 60 min and then cooled in an ice bath for 10 min. Next, the 200 μl reaction mixture was pipetted into a 96-well plate and absorbance was read on an Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer at 532 nm. This method was validated by a standard curve of varying concentrations of MDA demonstrating a linear regression with an R-square value of 0.96.

2.6. Expression analysis of dopamine active transporter (DAT) and monoamine oxidase b (MAOb)

RNA was extracted from the striatum using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). After DNase treatment and purification using the RNeasy MinElute Clean-up kit (Qiagen), the RNA was used as a template for cDNA synthesis with High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). The final cDNA product was used in SYBR-Green (Applied Biosystems) PCR reactions with primers specific to the target genes. Cycle numbers were normalized to hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) from a parallel reaction using the ΔΔCt method as described previously (Clark et al. 2012).

2.7. Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed by one-way ANOVA (DAT and MAOb mRNA levels) or two-way ANOVA (striatal TH densitometry, stereological neuronal counts, dopamine and its metabolites, oxidative stress) followed by Bonferroni’s Post hoc tests. GraphPad Prism 4.0 was used for all statistical analyses. A probability level of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant for all statistical tests.

3. Results

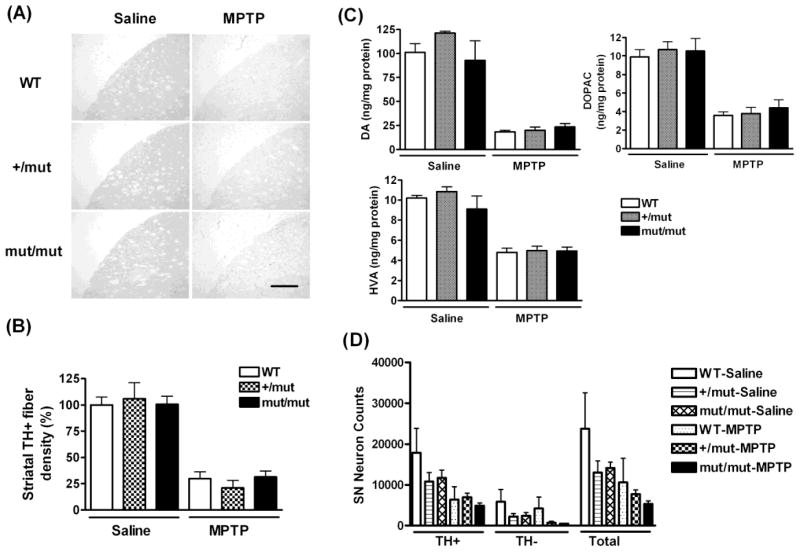

Subcutaneous injections of MPTP (20 mg/kg) performed every other day for a period of 9 days (5 injections in total) resulted in a significant reduction (approximately 70%~80%) in the density of striatal TH staining in all mice regardless of genotype (Fig. 1A and B). The magnitude of this loss of TH immunoreactivity was not significantly different in either POLG mut/mut or +/mut mice compared to WT littermate controls. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test indicated a significant effect of MPTP treatment (F =116.9; p<0.0001), but no significant effect of genotype or interaction between treatment and genotype. Levels of striatal dopamine (DA) and its metabolites, 3–4 dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and homovanillic acid (HVA), were measured by HPLC (Fig. 1C). Consistent with the results for TH immunoreactivity, there was a significant reduction in striatal DA and its metabolites in MPTP-treated mice, but there were no significant differences between genotypes in the magnitude of MPTP-induced loss of these striatal monoamines. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test indicated a significant effect of MPTP treatment (DA: F=120.4, p<0.0001; DOPAC: F=82.0, p<0.0001; HVA: F=96.5, p<0.0001), but the effect of genotype and the interaction between treatment and genotype were not significant. Consistent with the lack of significant genotype effects on susceptibility to MPTP based on TH staining or on levels of striatal monoamines, we also found no significant differences between genotypes in stereological counts of TH+, TH−, or total SN neurons, although there is a significant effect of MPTP treatment on TH+ and total SN neurons (Fig. 1D). Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test indicates a significant effect of MPTP treatment on TH+ and total SN neuronal numbers (TH+ neurons: F=11.0, p=0.005; total neurons: F=7.5, p=0.02), but the effect of genotype and the interaction between treatment and genotype were not significant.

Fig. 1.

Young (2~3 month old) POLG mutator mice do not exhibit increased susceptibility to MPTP-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration. (A) Representative images of TH immunostaining of the striatum from mice treated with either saline or MPTP (n= 3~5 per group). Scale bar= 300 μm. (B) Densitometric quantification indicating that the densities of TH-positive fibers in the striatum are similar across genotypes at baseline and after MPTP treatment. (C) HPLC measurements of striatal levels of DA, DOPAC and HVA in mice treated with saline or MPTP (n= 8 per group). (D) Stereological counts of TH+, TH− and total neurons in SN (n= 3~4 per group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test indicates a significant effect of MPTP treatment in (B), (C) and TH+ and total SN neurons in (D), but the effect of genotype and interaction between treatment and genotype are not significant.

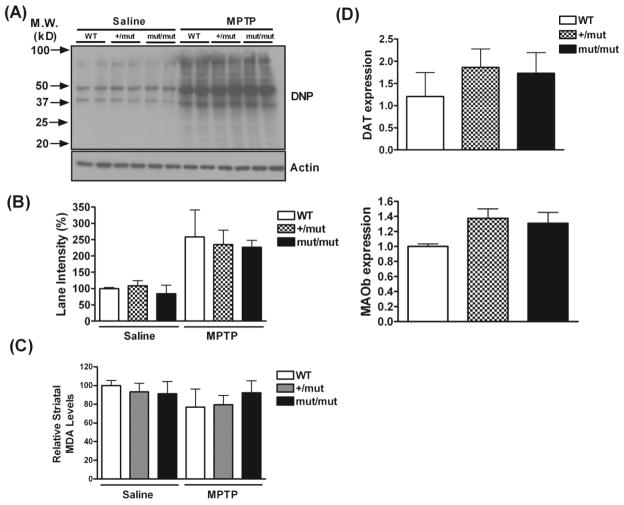

Next, we tested if expression of mutant POLG increased neuronal susceptibility to MPTP-induced oxidative stress. Carbonyl groups are major products of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated oxidation reactions with proteins. Therefore, carbonyl derivatives of striatal proteins were measured by OxyBlot as an index of MPTP-induced oxidative stress (Fig. 2A and B). We found a dramatic increase in the formation of protein carbonyl derivatives in response to MPTP across all genotypes. However, the levels of this marker of oxidative stress after MPTP remained comparable among the three genotypes. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test indicated a significant effect of MPTP treatment (F=17.8; p=0.0005), but no significant effect of genotype or interaction between treatment and genotype. Additionally, we measured striatal levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) as an index of lipid oxidative stress (Fig. 2C). We did not detect an increase in lipid oxidative damage in response to MPTP treatment in mice of any genotype. The lack of effect of MPTP on lipid peroxidation may be due to the fact that MDA may have undergone degradation during long-term storage at −80°C.

Fig. 2.

Oxidative stress caused by MPTP neurotoxicity, mRNA levels of DAT and MAOb in the SN of MPTP-treated mice. (A) Representative images of OxyBlots demonstrate a significant increase in the formation of protein carbonyl derivatives in mice following MPTP treatment (n= 4 per group). (B) Densitometric quantification of OxyBlot. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni test, indicating a significant effect of MPTP treatment, but the effect of genotype and interaction between treatment and genotype are not significant. (C) Levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) in the striatum were assessed for lipid oxidative damage. Data are normalized to the saline-treated WT group. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test indicates no significant effect of treatment, genotype or interaction between treatment and genotype (n= 4~5 per group). (D)There are no significant differences in mRNA levels of DAT or MAOb (normalized to HPRT) between POLG mutator mice and WT mice after MPTP treatment (n= 3~4 per group). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test.

The conversion of MPTP to its active metabolite, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), by monoamine oxidase B (MAOb), and the entry of MPP+ into dopaminergic neurons via dopamine transporter (DAT) are essential for the appearance of MPTP neurotoxicity. Although unlikely, the lack of significant differences in susceptibility to MPTP in the POLG mut/mut and +/mut mice compared to WT controls in theory could result from a decrease in MPP+ uptake (due to reduced DAT expression) and/or conversion to MPP+ (due to reduced MAOb expression) in the POLG mutator mice that are just sufficient to mask what otherwise would be an enhanced vulnerability to this toxin, but not enough to cause a decrease in vulnerability. Therefore we measured the expression of DAT and MAOb in the SN after MPTP injections by SYBR-green qPCR (Fig. 2D). There were no significant differences in DAT or MAOb expression levels across genotypes, with nonsignificant trends towards increased expression in POLG mut/mut and +/mut mice. Thus, it is unlikely that reduced uptake or conversion to MPP+ could account for the lack of an enhanced neuronal vulnerability to MPTP in the POLG mutator mice.

4. Discussion

The mitochondrial theory of aging is supported by transgenic mice carrying a proofreading-deficient form of POLG. The homozygous POLG mice accumulate mtDNA mutations and display multiple features of premature aging including weight loss, reduced subcutaneous fat, alopecia, kyphosis, osteoporosis, and early death (Trifunovic et al., 2004; Kujoth et al., 2005). Despite harboring mtDNA mutation levels that were higher than those reached during normal aging in WT mice, heterozygous POLG mice initially were reported to have no “overt” phenotype (Vermulst et al, 2007). This was interpreted as evidence against a role for somatic mtDNA mutations during normal aging. However, further metabolic and biochemical assessments revealed that both homozygous and heterozygous mice have deficits in resting oxygen consumption, heat production, mtDNA content and mitochondrial electron transport chain activities at 12~14 months of age (Dai et al., 2013). Furthermore, we hypothesized that even if a spontaneous phenotype was mild or lacking in the heterozygous POLG mice, somatic mtDNA mutations could play a role during normal aging by increasing vulnerability to additional stressors. However, our results demonstrate that susceptibility to MPTP in both heterozygous and homozygous POLG mice at 2 ~3 months of age is not significantly different from that of WT littermate controls. This is contrary to our prediction that the elevated levels of somatic mtDNA mutations at this age in the POLG mutator mice would increase neuronal vulnerability to MPTP, and instead argues that somatic mtDNA mutations do not increase susceptibility to environmental stressors. However, there are alternative possible explanations for these surprising results:

Somatic mtDNA mutations accumulate over time in the POLG mutator mice. It therefore remains possible that mutation levels at this young age have not yet reached high enough levels even in the homozygous mice to enhance vulnerability to MPTP. Furthermore, the consequences of somatic mtDNA mutations may require additional time to manifest, for example through the accumulation of oxidative damage. Although the initial characterization of POLG mutator mice failed to identify elevated oxidative stress in these mice (Kujoth et al. 2005), more recent studies provide evidence of a role for oxidative stress (Dai et al., 2010; Kong et al., 2011). Significantly depressed myocardial function and increased protein oxidative damage have been reported in older (13~14 months) but not in younger (4~6 months) POLG mut/mut mice. Overexpression of catalase, an antioxidant enzyme normally localized in the peroxisome, targeted to mitochondria can partially rescue the cardiac phenotype, indicating that the pathogenesis of this age-dependent cardiomyopathy is partly mediated by the increased mitochondrial oxidative stress seen in the older mice (Dai et al. 2010).

However, arguing against these possibilities is a prior study in 1-year old homozygous POLG mutator mice indicating reduced vulnerability to MPTP, suggesting that somatic mtDNA mutations may trigger compensatory protective mechanisms, including increased in mtDNA copy number, enhancement of mitochondrial cristae and decreased production of mitochondrial-derived ROS, at older ages (Perier et al., 2013). We did not find evidence for such protective mechanisms in the younger POLG mice, as they did not show reduced vulnerability to MPTP at young ages. Nevertheless, Perier et al. reported that despite the overall high levels of mtDNA deletions observed in various brain regions in POLG mice, cytochrome c oxidase (COX)-negative SN neurons exhibited even higher levels of mtDNA deletions than COX-positive neurons (60.38% vs 45.18%, p< 0.05), although the majority of SN dopaminergic neurons did not exhibit evidence of respiratory chain deficiency (Perier et al. 2013). These results indicated that the compensatory protective effects in these mice may be sufficient only when mtDNA deletions are lower than a certain threshold, as cells with mtDNA deletions exceeding 60% of total mtDNA showed mitochondrial biochemical defects, including reduced COX pathway activity. Therefore, it remains possible that at an older age, when the time-dependent accumulation of mtDNA mutations reaches a higher level, POLG mice may exhibit increased neuronal vulnerability to mitochondrial neurotoxins, such as MPTP. However, this will be difficult to test in the POLG mutator mice the mean life span of homozygous POLG mice is approximately 14 months, while POLG mice at 9~13 months of age are more resistant to MPTP-induced dopaminergic cell loss (Perier et al. 2013).

Although data on mtDNA copy number in POLG mutator mice vary across studies, alterations in mtDNA copy number could in part explain the lack of enhanced susceptibility to MPTP. A depletion of mtDNA content has been detected in POLG mutator mice in skeletal muscle, heart, liver (Safdar et al. 2011), and striatum (Dai et al. 2013), whereas Perier et al. reported significantly increased mtDNA copy number in the ventral midbrain of POLG mut/mut mice compared with their wild-type counterparts (Perier et al. 2013). PGC-1α deficient mice show increased vulnerability to MPTP, whereas overexpressing PGC-1α protects neural cells in culture from oxidative stressors (St-Pierre et al., 2006). Regional differences in levels of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α), a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, may contribute to these differences, as PGC-1α levels are decreased in skeletal muscle of POLG mut/mut mice and although PGC-1α levels are reported to be normal in brain, the specific brain area that was analyzed was not reported (Safdar et al. 2011). It is possible that upregulation of PGC-1α and higher mtDNA content in some brain areas represents a compensatory strategy that prevent these mice from being more vulnerable to MPTP toxicity.

The MPTP dose used in this study, resulting in 70–80% loss of striatal TH immunostaining intensity, might cause a floor effect that would diminish the ability to detect a difference in MPTP sensitivity across genotypes, and thus we cannot exclude the possibility that differences in vulnerability might have been detected with lower doses of MPTP that result in milder toxicity. The vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons to MPTP increases with age (Ohashi et al. 2006); (McCormack et al., 2004), and levels of somatic mtDNA mutations also increase with age in these neurons (Bender et al., 2006; Kraytsberg et al., 2006). However, contrary to our prediction, young POLG mutator mice with an accelerated accumulation of somatic mtDNA mutations show no difference in susceptibility to MPTP compared to wild-type controls. These results are consistent with and extend results from a prior study regarding older homozygous POLG mutator mice suggesting that somatic mtDNA mutations, below a certain threshold, may trigger compensatory protective mechanisms (Perier et al. 2013), which may mask the otherwise deleterious effects of somatic mtDNA mutations. Although these data do not directly support the hypothesis that somatic mtDNA mutations contribute to the age-related vulnerability to MPTP, it is important to recognize the limitations of this study as noted above, and the fact that the impact of mtDNA mutations on susceptibility to other stressors has not been tested. Thus, questions remain regarding the role of somatic mtDNA mutations in aging and in neurodegenerative diseases.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

POLG mice do not exhibit increased dopaminergic neuronal vulnerability to MPTP.

MPTP-induced protein oxidation is not exacerbated in POLG mice.

Expression levels of DAT and MAOb are similar in POLG and WT mice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (1R03AG035223-01; DKS).

Footnotes

5. Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abou-Sleiman PM, Muqit MM, Wood NW. Expanding insights of mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2006;7:207–19. doi: 10.1038/nrn1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender A, Krishnan KJ, Morris CM, Taylor GA, Reeve AK, Perry RH, et al. High levels of mitochondrial DNA deletions in substantia nigra neurons in aging and Parkinson disease. Nat Genet. 2006;38:515–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J, Silvaggi JM, Kiselak T, Zheng K, Clore EL, Dai Y, et al. Pgc-1alpha Overexpression Downregulates Pitx3 and Increases Susceptibility to MPTP Toxicity Associated with Decreased Bdnf. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai DF, Chen T, Wanagat J, Laflamme M, Marcinek DJ, Emond MJ, et al. Age-dependent cardiomyopathy in mitochondrial mutator mice is attenuated by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Aging Cell. 2010;9:536–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Kiselak T, Clark J, Clore E, Zheng K, Cheng A, et al. Behavioral and metabolic characterization of heterozygous and homozygous POLG mutator mice. Mitochondrion. 2013;13:282–91. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiskum G, Starkov A, Polster BM, Chinopoulos C. Mitochondrial mechanisms of neural cell death and neuroprotective interventions in Parkinson’s disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;991:111–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiona A, Sanz A, Kujoth GC, Pamplona R, Seo AY, Hofer T, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations induce mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptosis and sarcopenia in skeletal muscle of mitochondrial DNA mutator mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong YX, Van Bergen N, Trounce IA, Bui BV, Chrysostomou V, Waugh H, et al. Increase in mitochondrial DNA mutations impairs retinal function and renders the retina vulnerable to injury. Aging Cell. 2011;10:572–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraytsberg Y, Kudryavtseva E, McKee AC, Geula C, Kowall NW, Khrapko K. Mitochondrial DNA deletions are abundant and cause functional impairment in aged human substantia nigra neurons. Nat Genet. 2006;38:518–20. doi: 10.1038/ng1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujoth GC, Hiona A, Pugh TD, Someya S, Panzer K, Wohlgemuth SE, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mammalian aging. Science. 2005;309:481–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1112125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston JW. The etiology of Parkinson’s disease with emphasis on the MPTP story. Neurology. 1996;47:S153–60. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.6_suppl_3.153s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston JW, Ballard P, Tetrud JW, Irwin I. Chronic Parkinsonism in humans due to a product of meperidine-analog synthesis. Science. 1983;219:979–80. doi: 10.1126/science.6823561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MT, Cantuti-Castelvetri I, Zheng K, Jackson KE, Tan YB, Arzberger T, et al. Somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in early parkinson and incidental lewy body disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:850–4. doi: 10.1002/ana.23568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnane AW, Marzuki S, Ozawa T, Tanaka M. Mitochondrial DNA mutations as an important contributor to ageing and degenerative diseases. Lancet. 1989;1:642–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack AL, Di Monte DA, Delfani K, Irwin I, DeLanney LE, Langston WJ, et al. Aging of the nigrostriatal system in the squirrel monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2004;471:387–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudo G, Makela J, Di Liberto V, Tselykh TV, Olivieri M, Piepponen P, et al. Transgenic expression and activation of PGC-1alpha protect dopaminergic neurons in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:1153–65. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0850-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi S, Mori A, Kurihara N, Mitsumoto Y, Nakai M. Age-related severity of dopaminergic neurodegeneration to MPTP neurotoxicity causes motor dysfunction in C57BL/6 mice. Neurosci Lett. 2006;401:183–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perier C, Bender A, Garcia-Arumi E, Melia MJ, Bove J, Laub C, et al. Accumulation of mitochondrial DNA deletions within dopaminergic neurons triggers neuroprotective mechanisms. Brain. 2013;136:2369–78. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safdar A, Bourgeois JM, Ogborn DI, Little JP, Hettinga BP, Akhtar M, et al. Endurance exercise rescues progeroid aging and induces systemic mitochondrial rejuvenation in mtDNA mutator mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4135–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019581108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Pierre J, Drori S, Uldry M, Silvaggi JM, Rhee J, Jager S, et al. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell. 2006;127:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifunovic A, Wredenberg A, Falkenberg M, Spelbrink JN, Rovio AT, Bruder CE, et al. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature. 2004;429:417–23. doi: 10.1038/nature02517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermulst M, Bielas JH, Kujoth GC, Ladiges WC, Rabinovitch PS, Prolla TA, et al. Mitochondrial point mutations do not limit the natural lifespan of mice. Nat Genet. 2007;39:540–3. doi: 10.1038/ng1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.