Abstract

Drug addiction involves long-term behavioral abnormalities and gene expression changes throughout the mesolimbic dopamine system. Epigenetic mechanisms establish/maintain alterations in gene expression in the brain, providing the impetus for investigations characterizing how epigenetic processes mediate the effects of drugs of abuse. This review focuses on evidence that epigenetic events, specifically histone modifications, regulate gene expression changes throughout the reward circuitry. Drugs of abuse induce changes in histone modifications throughout the reward circuitry by altering histone-modifying enzymes, manipulation of which reveals a role for histone modification in addiction-related behaviors. There is a complex interplay between these enzymes, resulting in a histone signature of the addicted phenotype. Insights gained from these studies are key to identifying novel targets for diagnosis and therapy.

Keywords: histone modifications, epigenetics, addiction, acetylation, methylation, chromatin, animal behavior

Introduction

Addiction is often described as maladaptive neural plasticity in response to drugs of abuse, which results in long-term molecular alterations in key brain regions leading to life-long behavioral abnormalities. While there is much evidence supporting a strong genetic component of susceptibility to addiction [1], it is also thought that the addicted phenotype is a result of exposure to “risk factors,” including early life experiences and other environmental stimuli, that “prime” an organism to be more vulnerable to addiction [2]. Because of the strong influence of external risk factors on the development of addiction, it has been proposed that epigenetic mechanisms regulate the long-term changes associated with this phenotypic priming and the subsequent addicted phenotype.

In its broadest definition, epigenetics is described as changes in gene expression that do not arise from changes to the DNA sequence; this generally involves alterations in histone modifications, DNA methylation, and noncoding RNAs (microRNAs and long noncoding RNAs). Each of these mechanisms can be altered in response to internal and external signals and provide a mechanism by which environmental stimuli can interact with an individual’s genome to influence cellular response and function, including neuroplasticity. The differing temporal effects of each mechanism are, in part, a result of their varying levels of stability – e.g., most histone modifications are exceptionally dynamic, whereas DNA methylation is less so. With regards to addiction, epigenetic mechanisms alter gene expression in the following ways: 1) by changing the steady state expression of specific genes; 2) by priming genes for induction (sensitizing) or repression (desensitizing) in response to a stimulus (e.g., drug); or 3) regulating the expression of splice variants of specific genes that are sensitive to drugs of abuse [3].

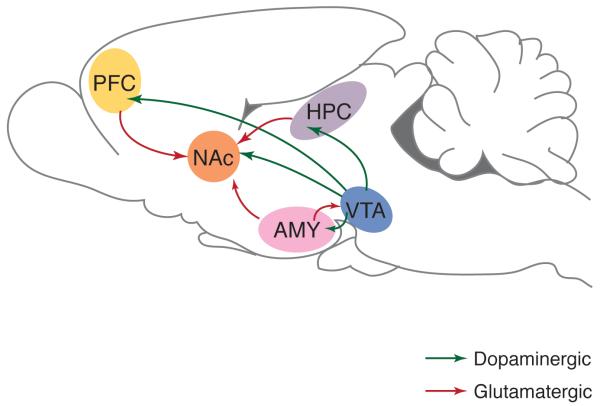

To date, a majority of the work on the epigenetic mechanisms involved in addiction have focused on histone modifications in response to stimulants (e.g., cocaine) and, to a lesser extent, opiates (e.g., morphine) in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), a key brain region involved in reward. Recently, work has expanded to other brain regions in the reward circuitry (Figure 1) including the ventral tegmental area (VTA), prefrontal cortex (PFC), basolateral amygdala (BLA), and hippocampus (HPC), as well as to other drugs of abuse (e.g., ethanol [EtOH]). Therefore, the focus of this review will be on stimulant effects in the NAc but will include information from other brain regions and drugs of abuse where information is available.

Figure 1.

Exposure to drugs of abuse results in epigenetic alterations throughout the brain reward circuitry. The major brain regions involved in mesolimbic reward pathway are depicted in the rodent brain: dopaminergic neurons (green) in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) project to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), prefrontal cortex (PFC), amygdala (AMY) and hippocampus (HPC). The NAc also receives glutamatergic (red) innervation from the PFC, AMY and HPC. While the mechanisms of action are specific for each drug, most drugs of abuse increase dopaminergic signaling from VTA to other regions of the reward circuitry. Many studies investigating epigenetic mechanisms of addiction have focused on the NAc as it is a major region of integration for rewarding stimuli. Modified from [2]with permission.

Histone Modifications

DNA is condensed into the nucleus of the cell in a highly organized and compact manner referred to as chromatin. The functional unit of chromatin, the nucleosome, is composed of ~147 base pairs wrapped around core histone octamers consisting of 2 copies of each of the following proteins: H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 (Figure 2). Each histone protein can undergo numerous post-translational modifications (PTMs) in which different functional groups are covalently added to amino acid residues of their N-terminal tails – e.g., acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation, citullination, and ADP-ribosylation, among others. These modifications not only alter the structure of the nucleosome but also change the interaction of DNA with the associated histones, thus increasing or decreasing the likelihood of transcription at a given locus. Histone modifications are diverse, and we are only beginning to understand how the various combinations of PTMs influence or indicate specific transcriptional states [4]. Additionally, new PTMs and novel modified amino acid residues continue to be discovered [5]. Finally, histone modifications are added or removed by a large family of enzymes referred to as “writers” and “erasers,” respectively, making them reversible and dynamic epigenetic modifications. While it is thought that myriad histone modifications and their interactions are likely involved in the regulation of the acquisition and maintenance of the addicted phenotype, histone acetylation and methylation are currently the most extensively studied PTMs in the addiction field.

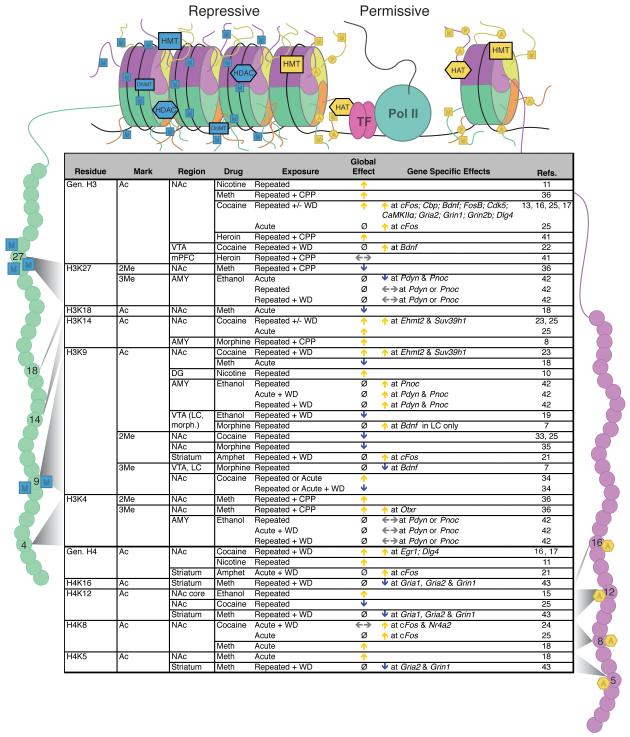

Figure 2/Table 1.

Chromatin modifications regulated by drugs of abuse. The illustration (top) indicates histone octamers in a repressive (left) or permissive (right) state. Enzymes involved in maintaining these states and associated transcription factors are indicated and histone tails with specific residues are highlighted as targets of modification: H3 residues subject to methylation or acetylation are indicated in green on the left and H4 residues subject to acetylation are indicated in purple on the right. Table (bottom) lists histone tail modifications of specific residues that are altered in response to drugs of abuse. Arrows indicate an increase (yellow), decrease (blue) or no effect (gray) in specific modifications, Ø indicates that no information is available. Abbreviations: 2Me – dimethylation; 3Me – trimethylation; Ac – acetylation; Amphet – amphetamine; AMY – amygdala; Bdnf – brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CaMKII – calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II alpha; Cbp – CREB-binding protein; cFos – FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog; CPP – conditioned place preference; DG – dentate gyrus; Egr1 – early growth response protein 1; Ehmt2 – euchromatic histone-lysine N-methyltransferase 2; Gria1 – glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA 1; Gria2 – glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA 2; Grin1 – glutamate receptor, ionotropic, N-methyl D-aspartate 1; Grin2b – glutamate receptor, ionotropic, N-methyl D-aspartate 2B; LC – locus coeruleus; Meth – methamphetamine; mPFC – medial prefrontal cortex; NAc – nucleus accumbens; Nr4a2 – nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2; Otxr – oxytocin receptor; Pdyn – prodynorphin; Pnoc – pronociceptin; Dlg4 – discs, large homolog 4; postsynaptic density protein 95, PSD-95; Suv39h1 – suppressor of variegation 3-9 homolog 1; VTA – ventral tegmental area; WD – withdrawal. Modified from [40] with permission

Histone Acetylation

Histone acetylation is generally associated with a permissive transcriptional state (Figure 2). By negating the positive charge associated with the lysine residues on histone tails, acetylation promotes an “open” chromatin state. Histone acetylation, especially in response to cocaine, is by far the most studied modification in addiction models [6]. While the effects of drugs of abuse are widespread, a picture of how histone acetylation is changing throughout the brain after exposure to drugs of abuse including cocaine [6], morphine [7,8], nicotine [9-11], and others is beginning to emerge (Table 1). In general, acute or repeated exposure to drugs of abuse, including cocaine, ethanol, and morphine, increases global (i.e., total cellular levels of) acetylation at H3 and/or H4 throughout the reward circuitry including the whole striatum [12-14], NAc [11,15-17], dentate gyrus of the hippocampus [10], and BLA [8] (Table 1). Interestingly, acute exposure to methamphetamine results in a time dependent (1hr vs. 24 hr post exposure) decrease in acetylated H3 and increase in acetylated H4 in the NAc of rats [18]. Additionally, EtOH reduces total H3K9ac in VTA 14 hours after last exposure [19], suggesting that, even at the global level, altering histone acetylation in response to drugs of abuse is complex, exhibiting region- and drug-specific regulation. However, it does seem that drugs of abuse modulate histone acetylation to produce a transcriptionally active state in many regions of the reward circuitry.

Global alterations in acetylation provide insight into general changes in transcription in response to drugs of abuse. To further understand the mechanism of action of such changes it is necessary to identify sites of altered histone acetylation at specific genes. Chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP) (Table 2) has been used to identify drug-induced increases in pan-acetylation of histone H3 for a number of genes in specific brain reward regions. A common set of genes with enriched histone acetylation, consisting of immediate early genes and those involved in neuroplasticity, is beginning to emerge in the literature and includes cFos, Fosb, Bdnf, Cdk5, Cbp, and genes that encode several glutamate receptors (although methamphetamine decreases their acetylation) [20] (for specifics see Table 1). Specifically, H4ac is increased at the cFos promoter after acute but not chronic cocaine treatment, consistent with a desensitization of cFos expression only after chronic drug exposure [13,21]. In contrast, Bdnf and Cdk5 promoters display enriched H3ac only after chronic drug exposure [7,13,22], consistent with induction of these genes after chronic exposure to both cocaine [13,22] and morphine [7].

Table 2. Methods for Studying Histone Modifications.

| Method | |

|---|---|

| ChIP | Involves lightly fixing tissue to cross-link DNA to associated proteins; followed by fragmenting the fixed chromatin by sonication or micrococcal nuclease digestion; and finally, immunoprecipitating the fragmented chromatin with an antibody specific for a given modification of interest (e.g. acetylated or methylated histone). |

| qChIP | Involves quantifying the amount of immunoprecipitated chromatin at a single genomic region using qPCR analysis. |

| ChIP-chip | Involves quantifying the amount of immunoprecipitated chromatin at thousands of promoter regions using a promoter-specific DNA microarray. |

| ChIP-seq | Involves quantifying the amount of immunoprecipitated chromatin for all genomic regions by high- throughput sequencing. ChIP-seq has the additional advantage over ChIP-chip of providing higher base-pair resolution for each genomic region. |

| RNA-seq | Involves isolating RNA and converting it to cDNA, followed by high-throughput sequencing. RNA-seq has several advantages over older microarray methods, including higher base-pair resolution, detection of non-coding RNAs, and the ability to identify alternative splice variants. |

Detailed descriptions for the methods discussed herein are listed. Abbreviations: ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; qChIP, quantitative ChIP; seq, high throughput sequencing.

Genome-wide studies have been instrumental in identifying candidate genes involved in drug-related behaviors and addiction susceptibility. Using ChIP-Chip (Table 2), an earlier method for analyzing genome-wide changes in chromatin modifications, Renthal et al. (2009) carried out the first genome-wide map of pan-acetylation of histone H3 and H4 in the NAc in response to chronic cocaine. The authors reported increases of H3ac and/or H4ac at 1696 genes in the NAc and reduced levels of acetylation at only 206 genes, consistent with increased acetylation being the predominant modification. Interestingly, there was little overlap of genes displaying alterations of H3ac and H4ac (221 genes), and most genes did not follow the expected expression pattern predicted by altered histone modifications: hypoacetylation correlated with decreased gene expression and hyperacetylation correlated with increased gene expression [16]. These data indicate that additional gene regulatory mechanisms work in concert with histone acetylation to control drug-induced changes in gene expression.

It is likely that drugs of abuse alter histone modifications by affecting the activity or expression levels of histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), the enzymes that add or remove acetylation of lysine residues, respectively [3]. Indeed, several studies have reported that HDACs [21,23,24] and HATs [25] are recruited to promoter regions of specific genes in the NAc and striatum in response to stimulants (cocaine and amphetamine). Regulation of histone acetylation through manipulation of HAT and HDAC expression has yielded valuable information regarding the role of acetylation in drug-elicited behavioral responses [6,20] (Table 3). In general, decreasing histone acetylation in the NAc either through activation/overexpression of HDACs or inhibition/knockdown of HATs blunts the behavioral responses to cocaine and other drugs of abuse including a reduction in cocaine locomotor sensitization and conditioned place preference (CPP) and a reduced break point in cocaine self-administration. On the other hand, increasing histone acetylation in the NAc either through pharmacological inhibition of HDACs or viral-mediated overexpression of HATs initially facilitates the behavioral effects of many drugs of abuse including cocaine [26] (for specifics see Table 3). However, more complex effects are seen with sustained HDAC inhibition in NAc, which can blunt behavioral responses to cocaine by suppressing gene expression through the induction of repressive histone mechanisms (see below) [23]. Studies investigating general HDAC inhibition on behavioral outcomes have produced varying results but it seems that the effects are specific to the timing of exposure (either before, during or after exposure to drugs of abuse) as well as the length of exposure (Table 3).

Table 3. Histone modifying enzymes mediate drug-elicited behaviors.

| Histone Acetylation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histone Acetyl Transfrases (HATs) |

Region | Drug | Expression changes | Time of Exposure | Inhibition / Knockout |

Behavioral Effect of Inhibition |

Activation / Overexpression |

Behavioral Effect of Overexpression |

Refs. |

| CBP | NAc | Cocaine | Pre-treatment | viral mediated |

locomotor sensitization locomotor sensitization CPP acquisition CPP acquisition |

25 |

| Histone Deacetylases (HDACs) |

Region | Drug | Expression changes | Time of Exposure | Inhibition / Knockout |

Behavioral Effect of Inhibition |

Activation / Overexpression |

Behavioral Effect of Overexpression |

Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | |||||||||

| HDAC 1 | NAc | Cocaine | Pre-treatment | viral mediated / pharmacological |

locomotor sensitization locomotor sensitization |

23 | |||

| Meth |

protein protein |

18 | |||||||

| HDAC 2 | NAc | Cocaine | Pre-treatment | viral mediated |

locomotor sensitization locomotor sensitization |

23 | |||

| Meth |

protein protein |

18 | |||||||

| VTA | Ethanol |

protein protein |

19 | ||||||

| HDAC 3 | NAc | Cocaine | Pre-treatment Pre-treatment |

viral mediated viral mediated |

locomotor sensitization locomotor sensitization CPP acquisition CPP acquisition |

23

24 |

|||

| Systemic | Cocaine | Concurrent | pharmacological (1- 4 doses) |

CPP extinction CPP extinction  CPP reinstatement |

29 | ||||

| Class IIA | |||||||||

| HDAC 4 | NAc | Cocaine |

mRNA mRNA |

Pre-treatment | viral mediated |

drug motivation drug motivation CPP acquisition CPP acquisition |

17, 13, 24 |

||

| HDAC 5 | NAc | Cocaine |

mRNA mRNA mRNA mRNA |

Pre-treatment | knockout organism wide |

CPP CPP |

viral mediated |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition |

27, 24 |

| HDAC 9 | NAc | Cocaine | Pre-treatment | viral mediated |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition |

27 | |||

| Class IIB | |||||||||

| HDAC 10 | Striatum | Ethanol |

mRNA mRNA |

15 | |||||

| Class III | |||||||||

| Sirtuin 1 | NAc | Cocaine |

mRNA & protein mRNA & protein |

Pre-treatment | viral mediated |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition |

viral mediated |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition& locomotor sentization |

16, 30 |

| Morphine |

mRNA & protein mRNA & protein |

30 | |||||||

| Sirtuin 2 | NAc | Cocaine |

mRNA & protein mRNA & protein |

Pre-treatment | viral mediated |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition |

16, 30 | ||

| Class IV | |||||||||

| HDAC 11 | Striatum | Ethanol |

mRNA mRNA |

15 |

| General HDAC Inhibitors/Agonists |

Region | Drug | Time of Exposure | # of doses HDACi | Behavioral Effect | # of doses agonist | Behavioral Effect | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSA | NAc | Morphine | Pre-treatment | 3 |

hyperactivity hyperactivity |

44 | |||

| Heroin | Concurrent | 5 |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition |

41 | |||||

| NAc shell | Cocaine | Post-Treatment, microinjection |

5 |

dose response curve dose response curve  break point |

17 | ||||

| BLA | Morphine | ~30 |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition CPP extinction CPP extinction CPP reinstatement CPP reinstatement |

8 | |||||

| Systemic | Cocaine | Concurrent | 2 7 |

CPP acuisition CPP acuisition break-point break-point self-administration self-administration |

13

45 |

||||

| VPA | NAc | Amphet | Pre-treatment | 7 |

locomotor sensitization locomotor sensitization |

46 | |||

| Systemic | Amphet | Concurrent | 8 6 |

locomotor sensitization locomotor sensitization locomotor sensitization locomotor sensitization |

14, 12 12 |

||||

| NaB | Systemic | Cocaine | Concurrent | 1 2 10 1 4 7 |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition CPP extinction CPP extinction locomotor sensitization locomotor sensitization locomotor sensitization locomotor sensitization self-administration self-administration CPP extinction CPP extinction CPP reinstatement CPP reinstatement CPP extinction CPP extinction CPP reinstatement CPP reinstatement |

47

13 48 49 47 50 |

|||

| Sirtinol | NAc | Cocaine | Pre-treatment, osmotic mini pump |

~10 |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition self-administration self-administration |

16 | |||

| Resveratrol | Systemic | Cocaine | Concurrent | 4 |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition |

16 |

| Histone Methylation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methyltransferases (HMTs) |

Region | Drug | Expression changes | Time of Exposure | Inhibition / Knockout |

Behavioral Effect | Refs. | ||

| G9a | NAc | Cocaine/ Morphine |

mRNA mRNA |

Pre-treatment | viral mediated / pharmacological |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition |

33, 35 | ||

| GLP | NAc | Cocaine/ Morphine |

mRNA mRNA |

Pre-treatment | viral mediated | 33, 35 | |||

| MLL1 | NAc | Meth |

mRNA in CPP mRNA in CPP mRNA in HC mRNA in HC |

Pre-treatment | viral mediated |

CPP acquisition CPP acquisition |

36 |

| Histone Demethylases (HDMs) |

Region | Drug | Expression changes | Time of Exposure | Inhibition / Knockout |

Behavioral Effect | Refs. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KDM5c | NAc | Meth |

mRNA mRNA |

Pre-treatment | viral mediated |

CPP consolidation CPP consolidation |

36 |

“Writers” and “Erasers” of histone modifications mediate behavioral responses to drugs of abuse. The expression changes, brain region, drug of abuse, timing of exposure, type of manipulation, and behavioral outcome are listed for each enzyme. Only those enzymes with available information are included. Pre-treatment indicates that the manipulation occurred at least 24 hrs before exposure to drug of abuse. Concurrent indicates that the manipulation occurred between 60 and 0 min before exposure to drug. Post-treatment indicates that the manipulation occurred after exposure to drug of abuse. Arrows indicate an increase (yellow), decrease (blue) or no effect (grey). Abbreviations: Amphet – amphetamine; BLA – basolateral amygdala; CBP – CREB-binding protein; CPP – conditioned place preference; G9a – euchromatic histone-lysine N-methyltransferase 2; GLP – G9a-like protein; HC – home cage; KDM5c – lysine (K)-specific demetylase 5C; Meth – methamphetamine; MLL1 – myeloid/lymphoid mixed lineage leukemia I; NAb – sodium butyrate; NAc – nucleus accumbens; TSA – trichostatin A; VPA – valproic acid; VTA – ventral tegmental area.

While further investigation is needed to determine the specific role for each enzyme, recent studies are beginning to identify more selective effects of certain enzymes in drug-induced behaviors (Table 3). For example, overexpression of HDAC4 [13,17] or HDAC5 [27] or inhibition of CBP (a HAT) [25,28] weakens the response to repeated cocaine exposure as measured by locomotor activity [25,28] or CPP acquisition [13,17,27]. Additionally, focal deletion of HDAC1, but not HDAC2 or 3, from NAc mimics the effect of long-term HDAC inhibitor treatment by attenuating locomotor responses to cocaine [23]. Interestingly, focal deletion of HDAC3 in the NAc enhances cocaine CPP [24] as does knockout of HDAC5 [27], an effect not observed with HDAC9 [27]. This opposing effect observed with HDAC3 could be explained by the finding that HDAC3 plays an important role in drug-induced memory consolidation, as pharmacological inhibition of HDAC3 enhances extinction of cocaine-induced memories after CPP [29]. These data highlight the need for further characterization of these enzymes in acquisition and maintenance of addiction. While these manipulations have not been investigated in many other brain regions, there is evidence that CBP enrichment at Bdnf is increased in the VTA after cocaine self-administration followed by 7 days of forced abstinence, which is associated with an increase in H3 acetylation at the Bdnf promoter as well as an increase in Bdnf expression [22]. Finally, the class III HDACs, sirtuins (SIRTs), have been implicated in the actions of cocaine [16,30] and morphine [30]. Viral-mediated overexpression of Sirt1 or 2 in the NAc enhances cocaine and morphine reward whereas focal deletion of Sirt1 in the NAc inhibits acquisition of morphine and cocaine CPP [30]. While it is apparent that differences in histone acetylation state are involved in the behavioral response to acute and prolonged exposure to drugs of abuse, further studies are necessary to identify how these alterations work in concert to produce a temporally specific histone landscape that is indicative of the various stages of addiction.

Taken together, these data support the conclusion that cocaine is a potent regulator of histone acetylation in the NAc [16,27]. However, histone lysine acetylation is not the only modification contributing to expression changes and the “histone code” regulating these alterations is exceptionally complex [31], including acetylation of additional residues as well as numerous other types of histone modifications. Further investigations, which focus on additional histone modifications are necessary to develop a complete understanding of how each modification (or combination of modifications) regulates gene expression in response to drugs of abuse.

Histone Methylation

Histone methylation, another well-characterized histone modification, is associated with either activation or repression of gene expression depending on which residues are methylated and the number of methyl groups added. Indeed, translating the role of histone methylation and its responses to drugs of abuse is much more complex than histone acetylation. To date, most of the work on drugs of abuse has focused on the role of repressive histone methylation in addiction [26]. However, a recent study in NAc using ChIP-seq coupled with RNA-seq (Table 2) investigated how combinations of methylation marks (H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3k36me3 - activating marks; and H3K9me2, H3k9me3, H3K27me3 - repressive marks) correlate with altered transcript levels after exposure to repeated cocaine. While global changes across the genome were not observed, enrichment of H3K4me1 or H3K4me3 at specific gene regions was correlated positively with increased transcription levels, whereas enrichment of H3K9me2, H3K9me3 or H3K27me3 was negatively correlated with transcription [32]. Other studies have found that repeated exposure to cocaine decreases global levels of H3K9me2 [33] and H3K9me3 [34] in NAc, whereas repeated opiate exposure [35] decreases only H3K9me2 in this brain region. In contrast, methamphetamine treatment decreases H3K27me2 and increases H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 globally in NAc when exposure is coupled with CPP but not in the animals’ home cage [36], again suggesting that regulation of histone methylation in response to drugs of abuse is complex and likely drug-, region-, and context-specific.

As mentioned above, an emerging theme developing in the field suggests that inhibition of repressive histone modifying enzymes (e.g., HDACs, and histone methyltransferases [HMTs]) in the NAc enhances drug-associated behaviors. Studies manipulating these HMTs and associated histone demethylases (HDMs) support this.

A recent study investigating mixed lineage leukemia 1 (MLL1) and histone lysine (K)-specific demethylase 5C (KDM5c), which catalyze the methylation and demethylation of H3K4me3, a permissive mark, respectively, implicates H3K4me3 in drug-elicited behaviors. Methamphetamine administration increases expression of Mll1 mRNA in NAc when paired with a novel context, however, when exposure occurs in the home cage, expression is decreased. NAc-specific knockdown of MLL1 reduces global H3K4me3 levels and inhibits methamphetamine-induced CPP. Interestingly, NAc-specific knockdown of KDM5c increases global H3K4me3 but it also inhibits amphetamine CPP if the knockdown occurs after consolidation (between test days 1 and 2) [36]. This suggests that the methylation state of H3K4 in NAc plays a complex role in the temporal- and context-specific neuroplasticity required for development and expression of methamphetamine-induced behavioral adaptations.

Another histone lysine residue whose methylation state has proved to be critical in regulating drug-induced behavioral responses is H3K9. G9a and GLP (G9a-like protein), both of which are HMTs for H3K9me2, are down-regulated in the NAc by chronic cocaine [33,34] or opiates (G9a only) [35] – an effect that was not observed for other H3K9/K27 HMTs [33,35]. For both drugs, this down-regulation of G9a and/or GLP is associated with global decreases in levels of H3K9me2. Pharmacological inhibition or viral-mediated knockdown of G9a facilitates cocaine- or opiate-mediated CPP, whereas overexpression opposes drug-induced effects [33,35]. Indeed, the paradoxical suppression of cocaine-elicited behaviors after prolonged HDAC inhibition in NAc, or local knockout of HDAC1 (see above), appears to be mediated via the induction of G9a and its consequent repression of gene expression [23](Table 3). There are important cell-type specific effects of H3K9me2 in response to cocaine. Overexpression of G9a in dopamine receptor (Drd)2, but not Drd1, cells in the NAc reduced cocaine CPP. On the other hand, Drd1- or Drd2-specific knockout of G9a showed differing regulation of cocaine CPP, with Drd1 KO resulting in decreased CPP and Drd2 specific knockout increasing cocaine CPP [37]. However, these latter actions appear to be mediated via developmental consequences of an early knockout of G9a, particularly in Drd2 type neurons, emphasizing the important of using inducible manipulations in the study of epigenetic mechanisms involved in adult addiction. There is additional evidence that cell-type specific effects are tightly temporally regulated with acute and repeated cocaine exposure having different cell-type specific actions [38]. Taken together, these data suggest that histone methylation plays an important and complex role in drug-induced behaviors.

Other Histone Marks

Few studies have investigated the role of other histone modifications in response to drugs of abuse, however, a recent study suggests that polyADP-ribosylation of histones, a permissive mark, plays a role in cocaine induced neuronal plasticity. Expression of PARP1 (polyADP-ribosytransferase-1), a “writer” of histone polyADP-ribosylation, is increased in the NAc after repeated cocaine exposure leading to an increase in histone polyADP-ribosylation. Furthermore, overexpression of PARP1 in NAc enhances cocaine locomotor sensitivity and cocaine-induced CPP, and also increases cocaine self-administration, while infusion of a PARP1 inhibitor or overexpression of PARG (polyADP-ribosylglycohydrolase), an “eraser” of histone polyADP-ribosylation, yields opposing results. After repeated cocaine, there is a genome-wide increase of PARP1 binding across genes as determined by ChIP-seq (Table 2), and a significant correlation of greater PARP1 enrichment with increased gene expression [39]. These results are consistent with a permissive transcriptional environment following repeated cocaine exposure identified in previous studies. Further investigation of this and other histone modifications is under way, but in the future it will be necessary to integrate genome-wide alterations in a multitude of histone modifications in order to identify the complex code that is indicative of an addicted phenotype.

Conclusions

It is clear that epigenetic mechanisms play an important and complex role in the neuroplastic changes associated with addiction. Currently, histone acetylation and methylation are by far the most comprehensively studied histone modifications in the field of addiction. A comprehensive review of the data, which includes numerous drugs of abuse and brain regions, reveals several emergent properties with regards to histone modifications (Tables 1 and 3): 1) drugs of abuse generally increase the likelihood of transcription in NAc by increasing histone modifications associated with an “active” chromatin state and reducing those associated with a repressive chromatin state; 2) these activating marks are associated with immediate early genes and many others that have been implicated generally in neuroplasticity; 3) drugs of abuse likely affect the expression or activation of the “writers” and “erasers” of histone modifications, and manipulation of these enzymes in NAc and certain other brain regions alters the behavioral response to drugs of abuse. These enzymes are thus potential targets for therapeutic intervention, however, this must be viewed with caution since most chromatin regulatory proteins are expressed ubiquitously and their manipulation is likely to produce unacceptable side effects. These data are far from complete and future studies must focus on the myriad other histone marks as well as map these alterations genome-wide throughout the brain reward circuitry in response to drugs of abuse. Finally, as recent data suggest that these modifications interact to produce different chromatin states [23], a comprehensive analysis of how these marks interact on a genome-wide scale to produce the addicted phenotype is necessary. By developing a complete understanding of how histone modifications are altered in response to drugs of abuse, including studies focusing on genome-wide temporal changes involved in the acquisition, maintenance, and potential extinction of the addictive phenotype, we hope to develop effective treatments and interventions for the human population. To that end, more studies focusing on how genome-wide histone modifications are altered in self-administration paradigms are necessary to develop a more complete understanding of the behavioral effects associated with altered histone modifications. Such studies would allow for the identification of conserved and divergent mechanisms involved in contingent and non-contingent behavioral responses to drugs of abuse.

While we focus here on histone modifications, there are promising data for the involvement of DNA methylation and non-coding RNAs as well [26]. Further studies are necessary to identify genome-wide, including promoter and gene body, changes in several forms of DNA methylation within the NAc and other brain reward regions in response to drugs in order to develop a comprehensive understanding of how DNA methylation contributes to the addiction process. Likewise, advanced sequencing methods should be used to obtain a comprehensive appreciation of the many types of non-coding RNAs (micro-RNAs and long non-coding RNAs) that are altered in the brain’s reward circuitry in addiction. Because each of these types of epigenetic mechanisms acts in concert with one another, studies integrating this vast array of drug-induced alterations in DNA methylation and non-coding RNAs with histone modifications would be exceptionally informative. Overlaid on top of such analyses would then be exploration of how early life experiences modify the epigenetic state of brain regions rewards to help determine an individual’s vulnerability for addiction. Taken together, these studies would provide a comprehensive analysis of the epigenetic mechanisms underlying addiction and would offer considerable progress toward the development of improved biomarkers for vulnerability to and treatment of addiction.

Highlights.

We highlight evidence that histone modifications play a key role in drug addiction.

Drugs of abuse increase active histone marks and decrease repressive histone marks.

Drugs of abuse alter expression of “writers” and “erasers” of histone modifications.

Manipulating “writers” and “erasers” alters drug-induced behaviors.

Future studies must focus on other histone modifications and their interactions.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this review was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

* - of special interest

** - of exceptional interest

- 1.Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. Neural mechanisms of addiction: The role of reward-related learning and memory. Annual review of neuroscience. 2006;29:565–598. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pena CJ, Bagot RC, Labonte B, Nestler EJ. Epigenetic signaling in psychiatric disorders. Journal of molecular biology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaenisch R, Bird A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: How the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nature genetics. 2003;33(Suppl):245–254. doi: 10.1038/ng1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maze I, Noh KM, Soshnev AA, Allis CD. Every amino acid matters: Essential contributions of histone variants to mammalian development and disease. Nature reviews Genetics. 2014;15(4):259–271. doi: 10.1038/nrg3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *5.Dai L, Peng C, Montellier E, Lu Z, Chen Y, Ishii H, Debernardi A, Buchou T, Rousseaux S, Jin F, Sabari BR, et al. Lysine 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation is a widely distributed active histone mark. Nature chemical biology. 2014;10(5):365–370. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1497. This study identifies a novel histone modification, as well as 27 new lysine residues that can be modified.

- 6.Rogge GA, Wood MA. The role of histone acetylation in cocaine-induced neural plasticity and behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):94–110. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mashayekhi FJ, Rasti M, Rahvar M, Mokarram P, Namavar MR, Owji AA. Expression levels of the Bdnf gene and histone modifications around its promoters in the ventral tegmental area and locus ceruleus of rats during forced abstinence from morphine. Neurochemical research. 2012;37(7):1517–1523. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0746-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Lai J, Cui H, Zhu Y, Zhao B, Wang W, Wei S. Inhibition of histone deacetylase in the basolateral amygdala facilitates morphine context-associated memory formation in rats. Journal of molecular neuroscience: MN. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s12031-014-0317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang YY, Kandel DB, Kandel ER, Levine A. Nicotine primes the effect of cocaine on the induction of LTP in the amygdala. Neuropharmacology. 2013;74:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang YY, Levine A, Kandel DB, Yin D, Colnaghi L, Drisaldi B, Kandel ER. D1/D5 receptors and histone deacetylation mediate the gateway effect of LTP in hippocampal dentate gyrus. Learn Mem. 2014;21(3):153–160. doi: 10.1101/lm.032292.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine A, Huang Y, Drisaldi B, Griffin EA, Jr., Pollak DD, Xu S, Yin D, Schaffran C, Kandel DB, Kandel ER. Molecular mechanism for a gateway drug: Epigenetic changes initiated by nicotine prime gene expression by cocaine. Science translational medicine. 2011;3(107):107ra109. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalda A, Heidmets LT, Shen HY, Zharkovsky A, Chen JF. Histone deacetylase inhibitors modulates the induction and expression of amphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization partially through an associated learning of the environment in mice. Behavioural brain research. 2007;181(1):76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar A, Choi KH, Renthal W, Tsankova NM, Theobald DE, Truong HT, Russo SJ, Laplant Q, Sasaki TS, Whistler KN, Neve RL, et al. Chromatin remodeling is a key mechanism underlying cocaine-induced plasticity in striatum. Neuron. 2005;48(2):303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen HY, Kalda A, Yu L, Ferrara J, Zhu J, Chen JF. Additive effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors and amphetamine on histone H4 acetylation, cAMP responsive element binding protein phosphorylation and ΔFosB expression in the striatum and locomotor sensitization in mice. Neuroscience. 2008;157(3):644–655. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Botia B, Legastelois R, Alaux-Cantin S, Naassila M. Expression of ethanol-induced behavioral sensitization is associated with alteration of chromatin remodeling in mice. PloS one. 2012;7(10):e47527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renthal W, Kumar A, Xiao G, Wilkinson M, Covington HE, 3rd, Maze I, Sikder D, Robison AJ, LaPlant Q, Dietz DM, Russo SJ, et al. Genome-wide analysis of chromatin regulation by cocaine reveals a role for sirtuins. Neuron. 2009;62(3):335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L, Lv Z, Hu Z, Sheng J, Hui B, Sun J, Ma L. Chronic cocaine-induced H3 acetylation and transcriptional activation of CaMKII-α in the nucleus accumbens is critical for motivation for drug reinforcement. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(4):913–928. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin TA, Jayanthi S, McCoy MT, Brannock C, Ladenheim B, Garrett T, Lehrmann E, Becker KG, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine causes differential alterations in gene expression and patterns of histone acetylation/hypoacetylation in the rat nucleus accumbens. PloS one. 2012;7(3):e34236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arora DS, Nimitvilai S, Teppen TL, McElvain MA, Sakharkar AJ, You C, Pandey SC, Brodie MS. Hyposensitivity to gamma-aminobutyric acid in the ventral tegmental area during alcohol withdrawal: Reversal by histone deacetylase inhibitors. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(9):1674–1684. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng J, Nestler EJ. Epigenetic mechanisms of drug addiction. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2013;23(4):521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Renthal W, Carle TL, Maze I, Covington HE, 3rd, Truong HT, Alibhai I, Kumar A, Montgomery RL, Olson EN, Nestler EJ. ΔFosB mediates epigenetic desensitization of the c-Fos gene after chronic amphetamine exposure. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28(29):7344–7349. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1043-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt HD, Sangrey GR, Darnell SB, Schassburger RL, Cha JH, Pierce RC, Sadri-Vakili G. Increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Bdnf) expression in the ventral tegmental area during cocaine abstinence is associated with increased histone acetylation at Bdnf exon I-containing promoters. Journal of neurochemistry. 2012;120(2):202–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07571.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **23.Kennedy PJ, Feng J, Robison AJ, Maze I, Badimon A, Mouzon E, Chaudhury D, Damez-Werno DM, Haggarty SJ, Han MH, Bassel-Duby R, et al. Class I HDAC inhibition blocks cocaine-induced plasticity by targeted changes in histone methylation. Nature neuroscience. 2013;16(4):434–440. doi: 10.1038/nn.3354. This study was the first to show that sustained inhibition of HDAC1 leads to the induction of repressive histone modifications through the activation of the histone methyltransferase, G9a.

- 24.Rogge GA, Singh H, Dang R, Wood MA. HDAC3 is a negative regulator of cocaine-context-associated memory formation. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33(15):6623–6632. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4472-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malvaez M, Mhillaj E, Matheos DP, Palmery M, Wood MA. Cbp in the nucleus accumbens regulates cocaine-induced histone acetylation and is critical for cocaine-associated behaviors. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31(47):16941–16948. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2747-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nestler EJ. Epigenetic mechanisms of drug addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76(Pt B):259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renthal W, Maze I, Krishnan V, Covington HE, 3rd, Xiao G, Kumar A, Russo SJ, Graham A, Tsankova N, Kippin TE, Kerstetter KA, et al. Histone deacetylase 5 epigenetically controls behavioral adaptations to chronic emotional stimuli. Neuron. 2007;56(3):517–529. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levine AA, Guan Z, Barco A, Xu S, Kandel ER, Schwartz JH. Creb-binding protein controls response to cocaine by acetylating histones at the Fosb promoter in the mouse striatum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(52):19186–19191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509735102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **29.Malvaez M, McQuown SC, Rogge GA, Astarabadi M, Jacques V, Carreiro S, Rusche JR, Wood MA. HDAC3-selective inhibitor enhances extinction of cocaine-seeking behavior in a persistent manner. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(7):2647–2652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213364110. This study was the first to identify a role for HDAC3 in extinction of drug-seeking memories as systemic pharmacological inhibition of HDAC3 enhances extinction of cocaine-induced CPP.

- 30.Ferguson D, Koo JW, Feng J, Heller E, Rabkin J, Heshmati M, Renthal W, Neve R, Liu X, Shao N, Sartorelli V, et al. Essential role of Sirt1 signaling in the nucleus accumbens in cocaine and morphine action. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33(41):16088–16098. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1284-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293(5532):1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *32.Feng J, Wilkinson M, Liu X, Purushothaman I, Ferguson D, Vialou V, Maze I, Shao N, Kennedy P, Koo J, Dias C, et al. Chronic cocaine-regulated epigenomic changes in mouse nucleus accumbens. Genome biology. 2014;15(4):R65. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-4-r65. This study is the first to characterize genome-wide changes in H3 methylation of multiple lysine residues in response to repeated cocaine exposure. It also correlates these changes with altered transcription.

- **33.Maze I, Covington HE, 3rd, Dietz DM, LaPlant Q, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Mechanic M, Mouzon E, Neve RL, Haggarty SJ, Ren Y, et al. Essential role of the histone methyltransferase G9a in cocaine-induced plasticity. Science. 2010;327(5962):213–216. doi: 10.1126/science.1179438. This study reports for the first time the regulatory role of repressive histone methylation in drug addiction. It also highlights a feedback loop between a histone methyltransferase and the transcription factor ΔFosB.

- 34.Maze I, Feng J, Wilkinson MB, Sun H, Shen L, Nestler EJ. Cocaine dynamically regulates heterochromatin and repetitive element unsilencing in nucleus accumbens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(7):3035–3040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015483108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun H, Maze I, Dietz DM, Scobie KN, Kennedy PJ, Damez-Werno D, Neve RL, Zachariou V, Shen L, Nestler EJ. Morphine epigenomically regulates behavior through alterations in histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylation in the nucleus accumbens. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32(48):17454–17464. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aguilar-Valles A, Vaissiere T, Griggs EM, Mikaelsson MA, Takacs IF, Young EJ, Rumbaugh G, Miller CA. Methamphetamine-associated memory is regulated by a writer and an eraser of permissive histone methylation. Biological psychiatry. 2014;76(1):57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maze I, Chaudhury D, Dietz DM, Von Schimmelmann M, Kennedy PJ, Lobo MK, Sillivan SE, Miller ML, Bagot RC, Sun H, Turecki G, et al. G9a influences neuronal subtype specification in striatum. Nature neuroscience. 2014;17(4):533–539. doi: 10.1038/nn.3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jordi E, Heiman M, Marion-Poll L, Guermonprez P, Cheng SK, Nairn AC, Greengard P, Girault JA. Differential effects of cocaine on histone posttranslational modifications in identified populations of striatal neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(23):9511–9516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307116110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scobie KN, Damez-Werno D, Sun H, Shao N, Gancarz A, Panganiban CH, Dias C, Koo J, Caiafa P, Kaufman L, Neve RL, et al. Essential role of poly(adp-ribosyl)ation in cocaine action. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(5):2005–2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319703111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vialou V, Feng J, Robison AJ, Nestler EJ. Epigenetic mechanisms of depression and antidepressant action. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2013;53:59–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheng J, Lv Z, Wang L, Zhou Y, Hui B. Histone H3 phosphoacetylation is critical for heroin-induced place preference. Neuroreport. 2011;22(12):575–580. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328348e6aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.D’Addario C, Caputi FF, Ekstrom TJ, Di Benedetto M, Maccarrone M, Romualdi P, Candeletti S. Ethanol induces epigenetic modulation of prodynorphin and pronociceptin gene expression in the rat amygdala complex. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2013;49(2):312–319. doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9829-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jayanthi S, McCoy MT, Chen B, Britt JP, Kourrich S, Yau HJ, Ladenheim B, Krasnova IN, Bonci A, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine Downregulates Striatal Glutamate Receptors via Diverse Epigenetic Mechanisms. Biological Psychiatry. 2014;76(1):47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jing L, Luo J, Zhang M, Qin YT, Lawrence AJ, Liang JH. Effect of the histone deacetylase inhibitors on behavioural sensitization to a single morphine exposure in mice. Neuroscience Letters. 2011;494(2):169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romieu P, Host L, Gobaille S, Sandner G, Aunis D, Zwiller J. Histone deacetylase inhibitors decrease cocaine but not sucrose self-administration in rats. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28(38):9342–9348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0379-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim WY, Kim S, Kim JH. Chronic microinjection of valproic acid into the nucleus accumbens attenuates amphetamine-induced locomotor activity. Neuroscience Letters. 2008;432(1):54–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Itzhak Y, Liddie S, Anderson KL. Sodium butyrate-induced histone acetylation strengthens the expression of cocaine-associated contextual memory. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2013;102:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schroeder FA, Penta KL, Matevossian A, Jones SR, Konradi C, Tapper AR, Akbarian S. Drug-induced activation of dopamine D(1) receptor signaling and inhibition of class I/II histone deacetylase induce chromatin remodeling in reward circuitry and modulate cocaine-related behaviors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(12):2981–2992. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun J, Wang L, Jiang B, Hui B, Lv Z, Ma L. The effects of sodium butyrate, an inhibitor of histone deacetylase, on the cocaine- and sucrose-maintained self-administration in rats. Neuroscience Letters. 2008;441(1):72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malvaez M, Sanchis-Segura C, Vo D, Lattal KM, Wood MA. Modulation of chromatin modification facilitates extinction of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]