Abstract

Maternal social stress during late pregnancy programs hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis hyper-responsiveness to stressors, such that adult prenatally stressed (PNS) offspring display exaggerated HPA axis responses to a physical stressor (systemic interleukin-1β; IL-1β) in adulthood, compared with controls. IL-1β acts via a noradrenergic relay from the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) to corticotropin releasing hormone neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN). Neurosteroids can reduce HPA axis responses, so allopregnanolone and 3β-androstanediol (3β-diol; 5α-reduced metabolites of progesterone and testosterone, respectively) were given subacutely (over 24 h) to PNS rats to seek reversal of the “programmed” hyper-responsive HPA phenotype. Allopregnanolone attenuated ACTH responses to IL-1β (500 ng/kg, i.v.) in PNS females, but not in PNS males. However, 3β-diol normalized HPA axis responses to IL-1β in PNS males. Impaired testosterone and progesterone metabolism or increased secretion in PNS rats was indicated by greater plasma testosterone and progesterone concentrations in male and female PNS rats, respectively. Deficits in central neurosteroid production were indicated by reduced 5α-reductase mRNA levels in both male and female PNS offspring in the NTS, and in the PVN in males. In PNS females, adenovirus-mediated gene transfer was used to upregulate expression of 5α-reductase and 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase mRNAs in the NTS, and this normalized hyperactive HPA axis responses to IL-1β. Thus, downregulation of neurosteroid production in the brain may underlie HPA axis hyper-responsiveness in prenatally programmed offspring, and administration of 5α-reduced steroids acutely to PNS rats overrides programming of hyperactive HPA axis responses to immune challenge in a sex-dependent manner.

Keywords: 5α-reductase; adenoviral vector; allopregnanolone; 3β-androstanediol; estrogen receptor-β, prenatal stress

Introduction

Maternal stress during pregnancy “programs” the offspring's brain, altering physiology and behavior in later life. The hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is particularly sensitive to programming (Harris and Seckl, 2011), which may link fetal programming and increased susceptibility of offspring to adulthood cardiometabolic and neuropsychiatric pathologies (Barker et al., 1993; Seckl, 2004; Entringer et al., 2008; Weinstock, 2008). We have reported enhanced HPA axis responses to acute psychological (restraint) and physical (interleukin-1β; IL-1β) stressors in adult male and female offspring born to rats exposed to repeated social stress during the last week of pregnancy (Brunton and Russell, 2010).

Sex steroids influence HPA axis responses to stress (Handa et al., 1994). Testosterone suppresses, whereas estrogen enhances HPA responses to acute stress, such that females typically display greater stress responses than males (Handa et al., 1994; Viau et al., 2005). Progesterone treatment has little effect on the ACTH response to IL-1β in female rats (Brunton et al., 2009), but the progesterone metabolite, allopregnanolone (AP) suppresses HPA axis responses to stress in both sexes (Patchev et al., 1996; Brunton et al., 2009).

Progesterone and testosterone are metabolized into the neuroactive steroids, AP (5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one) and 3β-androstanediol (5α-androstane-3β,17β-diol; 3β-diol), respectively. Progesterone and testosterone are first converted into dihydroprogesterone (DHP) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), respectively, by 5α-reductase (Mellon and Vaudry, 2001). 3α-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3αHSD) converts DHP into AP (Mellon and Vaudry, 2001), whereas 3β-diol is synthesized from DHT by several enzymes: 3αHSD, 3βHSD, and 17βHSD (Gangloff et al., 2003; Steckelbroeck et al., 2004; Fig. 1). The brain produces both AP and 3β-diol, with the synthesizing enzymes found in astroglia, and 5α-reductase activity found in neurons (Compagnone and Mellon, 2000). Allopregnanolone is an allosteric modulator at postsynaptic GABAA receptors, enhancing effectiveness of GABA inhibition (Lambert et al., 2009), whereas 3β-diol (which has negligible activity at the androgen receptor) acts, particularly on HPA axis activity, via estrogen receptor-β (ERβ; Handa et al., 2009). Accumulating evidence indicates a role for 5α-reduced steroid metabolites (e.g., AP, 3β-diol) in dampening HPA axis responses to stress (Patchev et al., 1994; Lund et al., 2006; Brunton et al., 2009; Handa et al., 2009). Hence, impaired central neurosteroid mechanisms could explain the hyper-responsive HPA phenotype observed in prenatally stressed (PNS) rats.

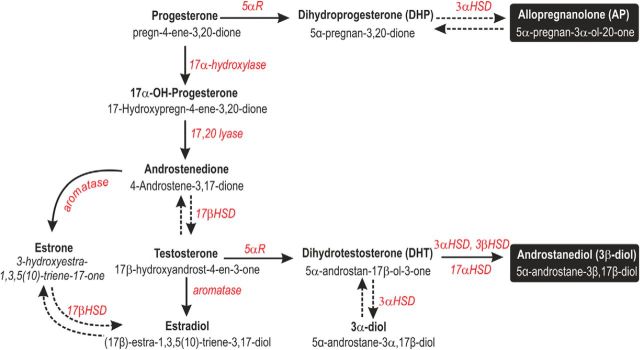

Figure 1.

Neurosteroid biosynthetic pathway. The enzymes and intermediates involved in the synthesis of AP and 3β-diol from steroid precursors. Common names are in bold with chemical names beneath. Enzymes are in italics. Dashed arrows indicate a reversible reaction. Abbreviations: 5αR, 5α-Reductase; 3α-, 3β-, 17α-, 17β-HSD, hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase.

Here, we hypothesized that deficits in central 5α-reduced neurosteroid production in offspring born to mothers exposed to social stress during pregnancy underlie the enhanced HPA axis responses to stress. We used systemic administration of IL-1β as a stressor in the offspring, because it acts via a clearly defined pathway from nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) A2 noradrenergic neurons to the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) neurons (Ericsson et al., 1994; Brunton et al., 2005). We tested in PNS offspring, whether: (1) peripheral administration of 5α-reduced steroids normalizes HPA axis responses to IL-1β, aiming to test actions of female and male neurosteroids according to sex; (2) there are differences in nodes regulating PVN CRH neurones in the central expression of 5α-reductase mRNA (indicator of neurosteroidogenic capacity); and (3) upregulating expression of genes for 5α-reductase and 3αHSD in the NTS in females reverses HPA axis programming.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Female Sprague-Dawley rats weighing between 255 and 305 g on arrival were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. Rats were housed in open-top cages in a specific pathogen-free rodent facility, initially in groups of four to six, under standard conditions of temperature (20−21°C), humidity (50–55%), and lighting (12 h light/dark cycle, lights on at 08:00 h) with food and water ad libitum. Following acclimatization in the animal facility for ≥1 week, female rats were paired overnight with a sexually experienced male (from the in-house colony) and mating was confirmed by the presence of a semen plug in the breeding cage the following morning. This was designated day 1 of pregnancy (where the expected day of parturition was day 22). Pregnant rats were caged individually from gestational day 14. The numbers of rats in each group (range, 5–12) are given in the relevant figure legends. All procedures were performed with approval from the University of Edinburgh Ethical Committee and in accordance with current UK Home Office legislation.

Social stress procedure.

Pregnant rats (n = 24) were placed in the cage of an unfamiliar lactating “resident” rat (between days 2–8 of lactation, where day 1 was the day of parturition) for 10 min on 5 consecutive days (days 16–20 of gestation), between 09:00 and 11:30 h. The pregnant “intruder” rats were paired with a different lactating resident each day (Brunton and Russell, 2010). To defend their young, the lactating residents exhibit aggressive behavior toward intruders, which show defensive behavior and HPA axis responses (Neumann et al., 2001). Following the last social stress exposure (on day 20) pregnant rats were returned to their home cage and left undisturbed, except for routine husbandry, through parturition and lactation until weaning. Pregnant controls (n = 25) remained in their home cage throughout, except for daily weighing and routine husbandry.

On the day of parturition, the litter size, pup birth weights, and male–female ratio were recorded. The litters remained with the dams until weaning on postnatal days 21–22 (litter sizes were not adjusted). Following weaning, the offspring were housed in groups of same-sex littermates until experiments began. To avoid within-litter effects, offspring for subsequent experiments were randomly selected across different litters; i.e., 1 male and 1 female from each litter were used to directly compare differences between control and PNS offspring. In cases where four experimental groups were used, two rats of each sex per litter were selected, with one being assigned to the “treated” group (e.g., drug) and the other assigned to the “nontreated” group (e.g., vehicle).

Jugular vein cannulation and blood sampling.

Four days before the blood sampling experiments, rats were fitted with a silicone (bore, 0.5 mm; wall, 0.25 mm) jugular vein cannula filled with sterile heparinized (50 U/ml) saline (0.9%) under halothane inhalational anesthesia (2–3% in 1200 ml/min oxygen). On the day of blood sampling (between 08:00–09:00 h), each silicone cannula was connected to PVC tubing filled with sterile heparinized 0.9% saline and connected to a 1 ml syringe. Rats were left undisturbed for 90 min before blood sampling commenced. Blood samples (0.3 ml) were collected in syringes containing 20 μl chilled 5% (w/v) EDTA and kept on ice. Plasma was separated by centrifugation and stored at −20°C until subsequent assay. Withdrawn blood was replaced with an equivalent volume of warmed sterile 0.9% saline.

Experiment 1: effect of AP pretreatment on HPA axis responses to IL-1β in control and PNS rats.

To test whether AP treatment could normalize the exaggerated HPA axis responses to interleukin-1β (IL-1β) in PNS rats, blood samples were collected from gonadally intact male and female control and PNS rats (n = 5–8 rats/group) treated with AP (3 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg s.c.; 20 and 2 h before IL-1β, respectively; Steraloids) or vehicle (15% ethanol in corn oil; 0.5 ml/kg). Two basal blood samples were collected 30 min apart from male (aged 11–12 weeks) and female (aged 13–14 weeks; selected at random stages of the estrous cycle) control and PNS offspring. All rats were administered 500 ng/kg human recombinant interleukin-1β intravenously (1 μg/ml dissolved in 0.2% bovine serum albumin in PBS; R&D Systems). Further blood samples were collected 15, 30, 60, and 90 min after treatment. Rats were killed by conscious decapitation 4 h after IL-1β injection and trunk blood was collected in chilled 5% EDTA (0.2 ml/100 g body weight), and plasma separated and stored as above.

Experiment 2: effect of 3β-diol pretreatment on HPA axis responses to IL-1β in control and PNS male rats.

To test whether 3β-diol treatment could normalize the exaggerated HPA axis responses to IL-1β in male PNS rats, blood samples were collected from gonadally intact male control and PNS rats (n = 7–9 rats/group) treated with 3β-diol (1 mg/kg s.c.; 20 and 2 h before IL-1β, respectively; Apin Chemicals) or vehicle (8% ethanol in sesame oil; 0.5 ml/kg). Two basal blood samples were collected 30 min apart from male (∼20 weeks of age) control and PNS offspring. All rats were administered 500 ng/kg IL-1β intravenously, blood sampled, and killed as in Experiment 1. Brains were rapidly removed, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −75°C until sectioning and in situ hybridization (ISH) processing for CRH mRNA.

As 3β-diol can exert its effects on HPA axis stress reactivity via estrogen receptor-β (ER-β) in the PVN, we tested whether mRNA expression for ER-β is downregulated in the PVN of PNS rats. We also quantified ER-β mRNA in the A2 region of the NTS, given this brain area is an important relay in IL-1β-stimulated activation of the HPA axis. Separate groups of six untreated, gonadally intact male (13–14 weeks old) control and PNS rats were killed by conscious decapitation. Brains were removed, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −75°C until sectioning and ISH processing for ER-β mRNA (see In situ hybridization, below).

Experiment 3: 5α-reductase mRNA expression in control and PNS rats.

Directly quantifying neurosteroid concentrations in specific discrete brain regions presents a number of technical challenges (e.g., as a result of high heterogeneity in the brain and low physiological concentrations of the neurosteroids of interest; Taves et al., 2011). The limited sensitivity of current methods dictates a loss of neuroanatomical specificity and precludes measurements in highly localized brain regions, such as the PVN or NTS. As the expression of steroidogenic enzymes determines the steroidal milieu of different brain regions (Do Rego et al., 2009), we quantified mRNA expression in situ for the steroidogenic enzymes of interest (instead of products of these enzymes), as an indication of potential local neurosteroid production. Thus, to establish whether prenatal stress reduces the capacity for central neurosteroid production in PNS rats, we quantified the central expression of 5α-reductase (the rate-limiting enzyme) mRNA. Groups of 7–8 untreated, gonadally intact male and female (18–19 weeks old) control and PNS rats were killed by conscious decapitation. Brains and brainstems were removed, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −75°C until sectioning and ISH processing (see In situ hybridization, below).

Adenoviral vectors.

To evaluate whether by upregulating gene expression for 5α-reductase and 3α-HSD in the NTS (this area was selected as we found a significant reduction in 5α-reductase mRNA expression in both male and female PNS rats, whereas the NTS plays a critical role in mediating the actions of IL-1β on the HPA axis; Ericsson et al., 1994) we could normalize the HPA axis response to IL-1β in PNS rats, two types of adenovirus were generated. One expressing 5α-reductase type 1 (AdV-5αR) and the other expressing 3α-HSD (AdV-3αHSD), both driven by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and coexpressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) to aid visualization of the transfected areas.

Total RNA was extracted from tissues using TRIZOL reagent in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). For cDNA synthesis, 1 μg of rat brain total RNA was reverse transcribed using Invitrogen SuperScript II reverse transcriptase with random primers, as recommended by the manufacturer. The cDNA encoding 5α-reductase-1 was excised from pCMV4 (kindly provided by J. Ian Mason, University of Edinburgh) using restriction enzymes Cla1 and BamH1, and inserted into corresponding restriction sites of the shuttle vector, pacAd5.CMV.IRES.GFP. The cDNA encoding 3α-HSD was amplified using primers: 3α-HSD-forward (5′-GCCTCGAGGCGTAACAAGCGATGGATCC-3′) and 3α-HSD-reverse (5′-CCGATAGAAATGCTGACAAAGTCCACCA-3′). The PCR product was digested with Xho1 and BglII (native sequence) and ligated into compatible sites of adenoviral vector pacAd5.CMV.IRES.GFP (Cell Biolabs). Adenoviral vector pacAd5.CMV.GFP (Cell Biolabs) expressing eGFP was used as a control. The adenoviruses were generated by cotransfection of viral shuttle/backbone in HEK293T cells in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines. The adenoviruses were purified by two rounds of CsCl ultracentrifugation and desalted using Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassettes (Pierce, Thermo Scientific) to the following titers (plaque-forming units; PFU, per ml): Ad-5αR, 1.7 × 1011 PFU/ml and Ad-3αHSD, 1.3 × 1011 PFU/ml. The purified viruses were stored at −80°C until use.

In vivo adenovirus-mediated gene transfer into the NTS.

On day 1, 40 gonadally intact female PNS rats (20–21 weeks old) were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (60 mg/kg) and medetomidine (250 μg/kg) via intramuscular injection, and placed in a stereotaxic frame (Stoelting). A midline skin incision was made over the occipital bone and dorsal neck, the superficial neck muscles were separated, and the dorsal medulla exposed. Two groups of PNS rats were injected. The first received NTS microinjections of AdV-5αR and AdV-3αHSD. We administered both adenoviruses to ensure that there would be sufficient 3αHSD in the NTS to metabolize any DHP produced by action of 5α-reductase into AP. A second group of PNS rats received bilateral microinjections of the control AdV-eGFP only. Midline microinjections (500 nl) of the adenoviruses were made with glass micropipettes into the A2 region of the NTS (0.3–0.5 mm rostral to the calamus scriptorius, depth of 0.3 mm from the dorsal surface of the brainstem). Following the microinjections, the muscles and skin were sutured with 3-0 surgical silk (Ethicon) and anesthesia reversed with a subcutaneous injection of atipamezol (1 mg/kg, i.m.). Rats were then housed singly in cages placed on a heat pad overnight for recovery. Rats were given the equivalent of 0.5 mg/kg buprenorphine (Vetergesic) orally (dissolved in a cube of strawberry flavored jelly) after surgery and again the following day.

Experiment 4: effect of adenovirus-mediated 5α-reductase and 3α-HSD gene transfer into the NTS on basal gene expression.

Sixteen PNS rats that underwent the NTS microinjection surgery (i.e., 8 transfected with AdV-5αR and AdV-3αHSD and 8 transfected with AdV-eGFP) were killed under basal conditions (i.e., no stress) by conscious decapitation 9 d after the NTS surgery to: (1) confirm the adenovirus-mediated gene transfer into the NTS increased 5α-reductase and 3α-HSD mRNA expression in the NTS, and (2) to establish whether adenovirus-mediated gene transfer into the NTS altered basal expression of CRH mRNA in the parvocellular division of the PVN (pPVN). To confirm progesterone treatment alone (used in Experiment 5) does not affect 5α-reductase or 3α-HSD mRNA expression in the NTS or CRH mRNA expression in the pPVN, two other groups were used: one group of eight vehicle-treated age-matched female controls and one group of eight age-matched female controls administered progesterone (dissolved in arachis oil; 5 mg/rat and 1 mg/rat, s.c. ca., 24 and 5 h before killing, respectively). Rats were killed by conscious decapitation, and brains and brainstems were rapidly removed, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −75°C until sectioning and ISH processing. Injection sites were verified by localization of eGFP in the NTS. Rats in which the AdV injection was outside the NTS were excluded from analysis.

Experiment 5: HPA axis responses in PNS rats following adenovirus-mediated upregulation of 5α-reductase and 3α-HSD mRNA levels in the NTS.

On day 8, 24 of the PNS rats (12 that were injected with AdV-5αR and AdV-3αHSD and 12 that were injected with AdV-eGFP) were fitted with a jugular vein cannula (see Jugular vein cannulation, above). To ensure a steady source of AP precursor, PNS rats were administered progesterone (dissolved in arachis oil; 5 mg/rat and 1 mg/rat, s.c., 20 and 2 h before IL-1β, respectively). On day 10, rats were blood sampled before and after IL-1β administration. Two basal blood samples were collected 30 min apart, and then all rats were administered 500 ng/kg of IL-1β intravenously (as in Experiment 1). Further blood samples were collected 15, 30, 60, and 90 min after treatment, as in Experiment 1, for plasma separation. An additional eight age-matched female control rats (that had not undergone stereotaxic surgery, but were fitted with a jugular vein cannula) were blood sampled simultaneously for comparison purposes. Rats were killed by conscious decapitation 4 h after IL-1β injection, and trunk blood was collected and plasma separated and stored as in Experiment 1. Brains and brainstems were rapidly removed, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −75°C until sectioning and ISH processing. Injection sites were verified by localization of eGFP in the NTS. Rats with the AdV injection outside the NTS were excluded from analysis.

Radioimmunoassays.

ACTH concentrations were determined in unextracted plasma using a two-site coated tube immunoradiometric kit (Euro-diagnostica and Biosource). Assay sensitivity was 1 pg/ml, and intra-assay variation was 6–9%. Corticosterone was measured using a commercially available radioimmunoassay kit (MP Biomedicals). Assay sensitivity was 25 ng/ml and intra-assay variation was 8–10%. Plasma total testosterone (albumin and sex hormone binding globulin, bound + free) and free testosterone (unbound) concentrations were measured using commercially available radioimmunoassay kits (MP Biomedicals). The assay sensitivity was 0.1 ng/ml for the total testosterone assay and 0.25 pg/ml for the free testosterone assay. Intra-assay variation was 8% and 5% for the total and free testosterone assays, respectively. Plasma progesterone concentrations were determined in unextracted plasma using a commercially available kit (Diagnostics Systems Laboratories). The assay sensitivity was 0.12 ng/ml and intra-assay variation was 7%. In each case, all samples from an individual experiment were assayed together.

In situ hybridization.

Coronal 15 μm brain and brainstem sections were cut on a cryostat, thaw-mounted onto polysine slides, and stored in desiccated boxes at −75°C until ISH processing. 35S-UTP-labeled cRNA probes were used to detect rat CRH, ERβ, 5α-reductase type I (Srd5a1; the predominant isoform expressed in the brain; Compagnone and Mellon, 2000) and 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD; Akr1c9) mRNA. To detect CRH mRNA, 35S-UTP-labeled riboprobes were synthesized from a linearized Bluescript KS vector expressing a 519bp rat CRH cDNA fragment (generously provided by Megan Holmes, University of Edinburgh, UK). The plasmid was linearized with HindIII and XbaI, and sense and antisense riboprobes transcribed with T7 and T3 polymerase (Riboprobe Systems, Promega), respectively. For ERβ mRNA, 35S-UTP-labeled riboprobes were synthesized from the linearized pBluescript KS vector expressing a 400 bp cDNA fragment encoding rat ERβ (generously provided by Megan Holmes, University of Edinburgh, UK). The plasmid was linearized with AccI and EcoRI, and sense and antisense cRNAs incorporating 35S-UTP were transcribed from the T7 and T3 promoters, respectively. To detect rat 5α-reductase type I mRNA (Compagnone and Mellon, 2000), 35S-UTP-labeled cRNA sense and antisense probes were synthesized from the linearized pBluescript SK vector expressing a 344 bp (nucleotides 991–1334) cDNA fragment encoding rat 5α-reductase type I (generously provided by Marcel Karperien, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands). The plasmid was linearized with XhoI and XbaI and sense and antisense cRNAs incorporating 35S-UTP were transcribed from the T3 and T7 promoters (Riboprobe Systems, Promega), respectively. To detect 3α-HSD mRNA, 35S-UTP-labeled sense and antisense riboprobes were generated from the linearized pGEM3 vector expressing a 982 bp (nucleotides −129 to +853) cDNA fragment encoding rat 3α-HSD (generously provided by Trevor Penning, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). The plasmid was linearized with SalI and SspI and transcribed using T7 and SP6 polymerase (Riboprobe Systems, Promega), for the sense and antisense riboprobes, respectively. ISH was performed as previously described in detail (Brunton et al., 2009). For each experiment, all sections were processed together for any given probe. Following hybridization, sections were washed stringently in saline sodium citrate buffer and treated with RNase A as previously described (Brunton et al., 2009).

Sections were dehydrated, dipped in autoradiographic emulsion (Ilford K-5) and exposed at 4°C for: 4 weeks for CRH and ER-β, 7 weeks for 5α-reductase, and 10 weeks for 3α-HSD (Brunton et al., 2009). Slides were next developed (Kodak D-19, Sigma-Aldrich), fixed (Hypam rapid fixer, Ilford), and counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin. In each case, brain sections hybridized with 35S-UTP-labeled cRNA sense probes or unlabeled cRNA antisense probes showed no signal above background.

Autoradiographs were quantified by measuring the area of each region of interest (e.g., PVN) and the silver grain area overlying the region (ImageJ software, v1.46, NIH). Data are presented as grain area/brain area (mm2/mm2). Background measurements were made over areas adjacent to the region-of-interest, converted to mm2/mm2 and subtracted. Measurements were made over 12–20 regions of interest per rat (i.e., bilateral measurements in 6–10 sections/rat). For all ISH measurements, average values for each rat were used to calculate group mean ± SEM.

Statistical analysis.

Sigma plot software (v11.0, Systat Software) was used. The specific statistical tests used are given in the results section and/or appropriate figure legends. Generally, two-way repeated-measures (RM) ANOVA was used to analyze treatment effects across time for plasma hormone data and two-way ANOVA, Student's t test or Mann–Whitney rank sum test was used to analyze ISH data. Specific differences were isolated using Student-Newman–Keuls multiple-comparison post hoc tests. Values shown are group mean ± SEM; p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effect of prenatal stress exposure on maternal weight gain, litter size, and offspring birth weight

Maternal weight gain was not significantly affected by prenatal stress exposure [mean weight gain in 3 cohorts of controls (n = 25 rats) was 11.9 ± 1.7% vs 12.5 ± 0.9% in the stress exposed groups (n = 26 rats); n.s., Student's t test]. Prenatal stress had no significant effect on either litter size or the proportion of male–female pups in any of the litters (Table 1). Birth weight was significantly lower in both PNS males and PNS females than control offspring (Table 1).

Table 1.

Litter characteristics

| Parameter | Status |

|

|---|---|---|

| Control | PNS | |

| Litter size | 13.3 ± 0.5 | 13.8 ± 0.6 |

| ♂ per litter | 6.6 ± 0.4 | 7.2 ± 0.5 |

| ♀ per litter | 6.7 ± 0.4 | 6.6 ± 0.5 |

| Birth weight ♂ (g) | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 6.1 ± 0.1* |

| Birth weight ♀ (g) | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 5.6 ± 0.1** |

| No. of litters | 24 | 24 |

Litter characteristics for male (♂) and female (♀) offspring from control and PNS dams across three separate cohorts;

* p < 0.02,

** p < 0.001 versus control; Student's t test. Data are mean/litter ± SEM.

Effect of AP pretreatment on ACTH and corticosterone responses to IL-1β in control and PNS rats

Females

There was no significant difference in basal plasma ACTH concentrations between female control and PNS rats (Fig. 2a,b). There was a significant effect of treatment (F(3,108) = 2.92; p = 0.047) and time (F(6,108) = 39.7; p < 0.001, two-way RM ANOVA) on plasma ACTH concentrations in female rats following IL-1β administration (Fig. 2a,b). In vehicle-pretreated groups, IL-1β increased ACTH concentrations significantly in both the control (p < 0.001) and PNS female rats (p < 0.001); however, the response was significantly greater in the PNS/vehicle group (p < 0.05; Fig. 2a,b). IL-1β also significantly increased ACTH secretion in both the AP-treated groups (control, p < 0.001; PNS, p = 0.015); however, the response was significantly suppressed by AP treatment in both the control (p = 0.026) and PNS (p < 0.001) groups compared with the vehicle-treated groups (Fig. 2a,b).

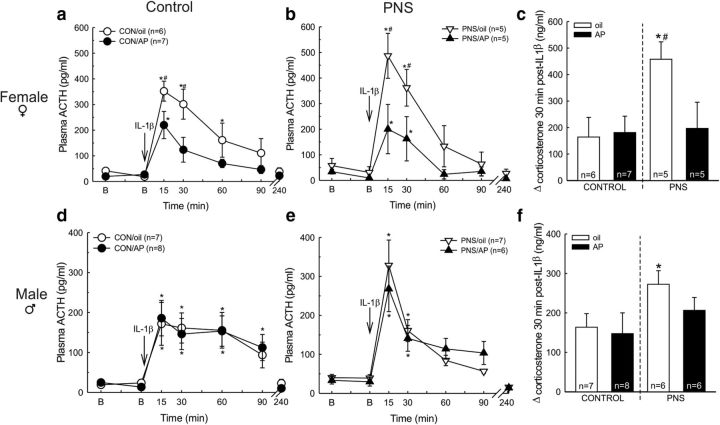

Figure 2.

Effect of AP pretreatment on ACTH and corticosterone responses to IL-1β in control and PNS rats. Rats were pretreated, 20 and 2 h before IL-1β, with either vehicle (oil) or AP (3 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg, s.c.). After two basal (B) blood samples (at t = −31 and −1 min), all rats were administered IL-1β (500 ng/kg, i.v.) at t = 0 min. Further blood samples were taken 15, 30, 60, and 90 min after IL-1β. Trunk blood was collected at t = 240 min; N = 5–8 rats/group (exact numbers are given in parentheses in the relevant key). Plasma ACTH concentrations in: (a) Control females, (b) PNS females, (d) control males, (e) PNS males; *p < 0.04 versus B values in the same group; #p < 0.05 versus all other groups at the same time point (two-way RM ANOVA). The increase in plasma corticosterone 30 min after IL-1β administration in (c) females and (f) males; *p < 0.05 versus control/oil group; #p < 0.05 versus PNS/AP group (two-way ANOVA). In each case values are group mean ±SEM or +SEM.

There was no significant difference in basal corticosterone concentrations between female control and PNS rats (mean ± SEM plasma concentrations were as follows: control/oil group = 94.8 ± 38.9 ng/ml, n = 6; control/AP group = 69.8 ± 18.8 ng/ml, n = 7; PNS/oil group = 42.2 ± 10.4 ng/ml, n = 5; PNS/AP group = 63.6 ± 36.6 ng/ml, n = 5; two-way ANOVA). There was a significant effect of treatment (F(1,19) = 4.48; p = 0.048; two-way ANOVA) on IL-1β-induced corticosterone secretion in females. Thirty minutes after systemic IL-1β, the increase in corticosterone secretion was significantly greater in the vehicle-pretreated PNS females than in the vehicle-pretreated control females (p = 0.01; Fig. 2c). The increase in corticosterone secretion 30 min after IL-1β administration was significantly lower in the AP-pretreated PNS females compared with the vehicle-pretreated PNS females (p = 0.034; Fig. 2c).

Males

There was no significant difference in basal plasma ACTH concentrations between male control and male PNS rats (Fig. 2d,e). There was a significant effect of time (F(6,138) = 37.5; p < 0.001, two-way RM ANOVA) on ACTH secretion in male rats (Fig. 2d,e). In vehicle-pretreated rats, IL-1β significantly increased plasma ACTH concentration in both the control (p = 0.002) and PNS rats (p < 0.001); however, as expected the amplitude of the response was greater in the PNS males (p = 0.005; Fig. 1d,e). Allopregnanolone treatment had no significant effect on the ACTH response to IL-1β in either the control or PNS males (Fig. 2d,e).

There was no significant difference in basal corticosterone concentrations between the vehicle-pretreated control and PNS male rats, however, there was a significant effect of AP treatment on basal corticosterone in the PNS males (mean ± SEM plasma concentrations were as follows: control/oil group = 49.2 ± 11.7 ng/ml, n = 7; control/AP group = 35.5 ± 11.6 ng/ml, n = 8; PNS/oil group = 68.2 ± 12.6 ng/ml, n = 7; PNS/AP group = 28.2 ± 2.2 ng/ml, n = 6; F(1,24) = 6.0, p = 0.022, two-way ANOVA). There was a significant effect of prenatal experience (F(1,19) = 4.7, p = 0.043; two-way ANOVA) on IL-1β-induced corticosterone secretion in males. Thirty minutes after systemic IL-1β, the increase in corticosterone secretion was significantly greater in the vehicle-pretreated PNS males than in the vehicle-pretreated control males (p < 0.05; Fig. 2f). AP treatment had no significant effect on the corticosterone response to IL-1β in either the control or the PNS males (Fig. 2f).

Sex differences

As expected, there was a significant sex difference in the ACTH response to IL-1β in the vehicle-treated control rats (F(1,21) = 4.9, p = 0.038, two-way ANOVA; Fig. 2a,d) with greater peak concentrations in the females than in the males. The peak ACTH response was not significantly different between the vehicle treated male and female PNS rats. No significant sex difference was detected in the corticosterone response to IL-1β.

Effect of 3β-diol pretreatment on HPA axis responses to IL-1β in male control and PNS rats

There was no difference in basal plasma ACTH concentration between any of the groups (Fig. 3a). There was a significant effect of treatment group (F(3,157) = 2.7, p = 0.048; two-way RM ANOVA) and time (F(6,157) = 19.2, p < 0.001; two-way RM ANOVA) on ACTH secretion. As before, the ACTH response to IL-1β was significantly greater in the vehicle-treated male PNS rats compared with the male control rats (3.2-fold greater at 30 min; p < 0.001; Fig. 3a). 3β-Diol had no significant effect on the ACTH response to IL-1β in the male control rats; however, the response was significantly attenuated by 3β-diol in the male PNS group (p < 0.001; Fig. 3a).

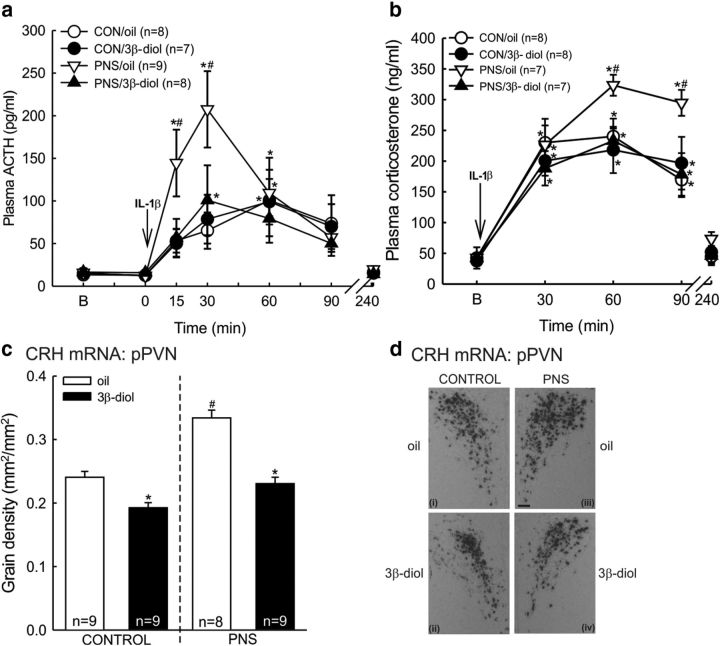

Figure 3.

Effect of 3β-diol pretreatment on HPA axis responses to IL-1β in male control and PNS rats. Control and PNS male rats were treated with either vehicle (oil) or 3β-diol (1 mg/kg, s.c.) 20 and 2 h before IL-1β. After two basal (B) blood samples (at t = −31 and −1 min), all rats were administered IL-1β (500 ng/kg, i.v.) at t = 0 min. Further blood samples were taken 15, 30, 60, and 90 min after IL-1β. Trunk blood was collected at t = 240 min. a, Plasma ACTH concentrations before and after IL-1β challenge: *p < 0.05 versus B values in the same group; #p < 0.005 versus all other groups at the same time point (two-way RM ANOVA). b, Plasma corticosterone concentration before and after IL-1β challenge: *p < 0.003 versus B values in the same group; #p < 0.04 versus all other groups at the same time point (two-way RM ANOVA). Quantification of (c) CRH mRNA expression in the parvocellular division of the PVN (pPVN) 4 h after IL-1β administration. CRH mRNA expression levels are expressed as grain area/PVN area (mm2/mm2); *p < 0.002 versus respective oil group; #p < 0.001 versus control/oil group (two-way ANOVA). In each case values are group mean ± SEM and n = 7–9 rats/group (exact numbers are given in parentheses in the relevant key or within the bars). d, Representative bright-field CRH mRNA ISH autoradiographs of coronal PVN sections from (di) control/oil; (dii) control/3β-diol; (diii) PNS/oil; and (div) PNS/3β-diol groups. Scale bar, 100 μm.

There was a significant effect of treatment group (F(3,97) = 4.2, p = 0.01; two-way RM ANOVA; Fig. 3b) and time (F(4,97) = 66.5, p < 0.001; two-way RM ANOVA; Fig. 3b) on plasma corticosterone concentrations. Consistent with the ACTH data, basal corticosterone secretion was not significantly different between any of the groups (Fig. 3b). IL-1β evoked a significant corticosterone response in all of the groups (p < 0.001); however, the response was significantly greater in the vehicle-pretreated PNS male rats compared with the controls (p = 0.02 at 60 min time point; Fig. 3b). 3β-Diol had no significant effect on the corticosterone response to IL-1β in the male control rats; however, 3β-diol significantly attenuated the corticosterone response to IL-1β in the male PNS rats (p = 0.03; Fig. 3b).

There was a significant effect of prenatal experience (F(1,31) = 44.5, p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA) and 3β-diol treatment (F(1,31) = 59.2, p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA) on CRH mRNA expression in the PVN. Four hours after systemic IL-1β, CRH mRNA expression was significantly greater in the vehicle-pretreated male PNS rats than in the control rats (p < 0.001; Fig. 3c,d). 3β-Diol significantly reduced CRH mRNA expression after IL-1β in both the male control (p = 0.002; Fig. 3c,d) and PNS rats (p < 0.001; Fig. 3c,d) compared with those pretreated with vehicle.

Effect of prenatal stress on ERβ mRNA expression in the PVN

As 3β-diol has been shown to exert its effects on HPA axis stress reactivity via ERβ in the PVN (Handa et al., 2009), we quantified mRNA for ERβ in this region. As IL-1β signals to the CRH neurons in the PVN via the NTS (Ericsson et al., 1994) we also quantified ERβ mRNA in the NTS. ERβ mRNA expression was significantly lower, under basal conditions, in both the parvocellular (t(10) = 3.36, p = 0.007; Student's t test) and the magnocellular (t(10) = 2.23, p = 0.05; Student's t test) divisions of the PVN of male PNS rats compared with controls (Fig. 4a,b). ERβ mRNA expression was also significantly lower in the NTS (t(10) = 2.68, p = 0.02; Student's t test) of male PNS rats compared with controls, under basal conditions (Fig. 4c,d).

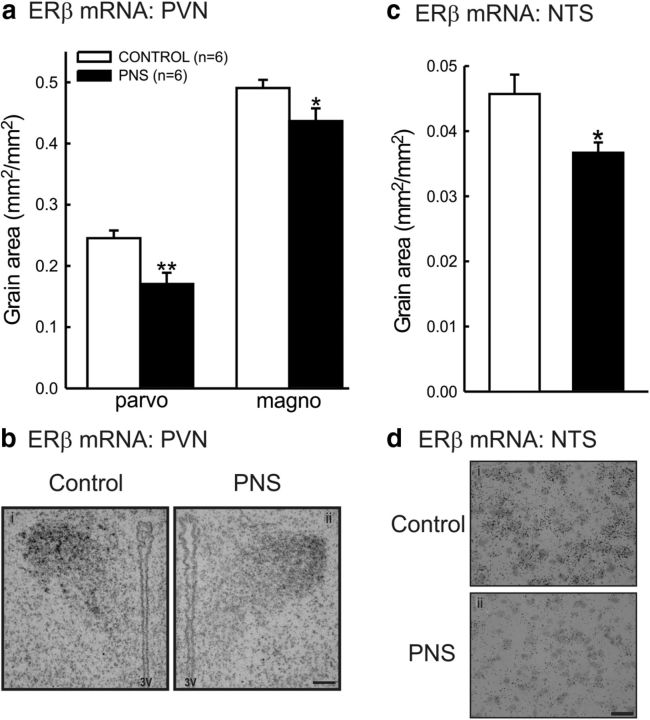

Figure 4.

Estrogen receptor-β mRNA expression in male control and PNS rats. Quantification of ERβ mRNA expression in (a) the medial parvocellular (parvo) and magnocellular (magno) subdivisions of the PVN, and (c) the NTS under basal conditions. In each case, values are group mean ± SEM and n = 6 rats/group; **p < 0.01 and *p ≤ 0.05 versus control group (Student's t test). Representative bright-field autoradiographs of (b) coronal PVN sections. Scale bar, 100 μm. 3V, third ventricle. d, Coronal NTS sections from a (di) control and (dii) PNS rat. Scale bar, 20 μm.

Effect of prenatal stress on plasma testosterone and progesterone concentrations

Total plasma testosterone concentrations were significantly greater in PNS males compared with control males (t(28) = −1.87, p = 0.036; Student's t test; Table 2). A weak tendency for increased circulating free testosterone in PNS males (Table 2) was not statistically significant (t(25) = −1.38, p = 0.09). Plasma progesterone concentrations were significantly greater in PNS females compared with control females (t(29) = −2.26, p = 0.016; Student's t test; Table 2).

Table 2.

Plasma testosterone and progesterone concentrations

| Control | PNS | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total testosterone (ng/ml) | 1.33 ± 0.19 | 2.04 ± 0.31* | 0.036 |

| Free testosterone (pg/ml) | 6.63 ± 0.88 | 9.49 ± 1.79 | 0.092 |

| Free testosterone (% total) | 0.58 ± 0.07 | 0.50 ± 0.04 | 0.34 |

| Progesterone (ng/ml) | 44.9 ± 9.1 | 75.8 ± 7.4* | 0.016 |

Plasma testosterone in control (n = 14) and PNS ( n = 16) male rats. Plasma progesterone in control (n = 8) and PNS (n = 23) female rats. Data are mean ± SEM.

* indicates a significant difference versus controls (Student's t test). p values are given in the table.

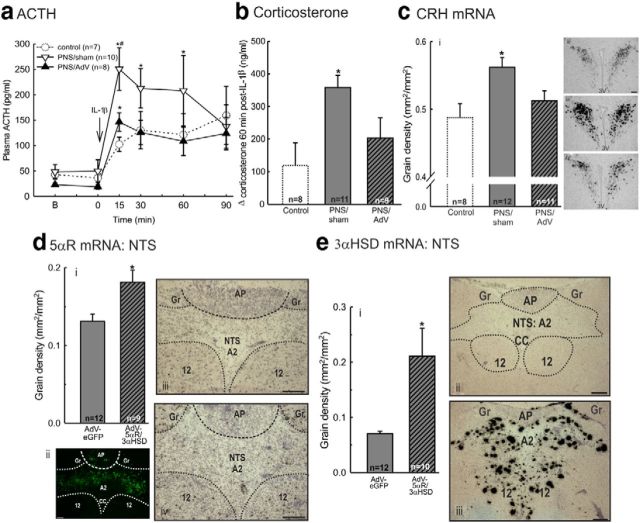

Effect of prenatal stress on central 5α-reductase mRNA expression

Males

Prenatal stress was associated with reduced expression of 5α-reductase mRNA in the PVN (t(12) = 2.8, p = 0.008; Student's t test; Fig. 5a) and NTS (t(12) = 3.6, p = 0.002; Fig. 5a), and in contrast, increased 5α-reductase mRNA expression in the medial prefrontal cortex (t(12) = 3.2, p = 0.004; Fig. 5a), Islands of Calleja (ICj; t(12) = 2.3, p = 0.02; Fig. 5a), and dorsal part of the lateral septum (t(12) = 3.3, p = 0.006; Fig. 5a).

Figure 5.

Brain 5α-reductase mRNA expression in control and PNS rats. Quantification of 5α-reductase mRNA expression in the mPFC, nucleus accumbens core (NAc), ICj, dorsal part of the lateral septum (LSd), ventral part of the lateral septum (LSv), parvocellular division of the PVN, central amygdala (CeA), basolateral (BLA), basomedial (BMA), CA1, CA2, and CA3 hippocampal subfields, and the A2 region of the NTS from (a) male and (b) female control and PNS rats under basal conditions. In each case values are group mean ± SEM and rat numbers are 7–8/group (exact numbers are given in parentheses in the relevant key); **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05 versus control group (Student's t test).

Females

Fewer brain regions showed changes in 5α-reductase mRNA expression in PNS females. PNS was associated with a significant decrease only in the NTS (t(12) = 1.9, p = 0.04; Fig. 5b), and with an increase only in the ICj (t(12) = −2.8, p = 0.008; Fig. 5b).

There was no significant difference in 3α-HSD mRNA expression in the NTS between control and PNS rats in either males or females (data not shown). Other brain regions were not examined.

Effect of adenovirus-mediated gene transfer into the NTS on basal gene expression in female PNS rats

5α-Reductase mRNA

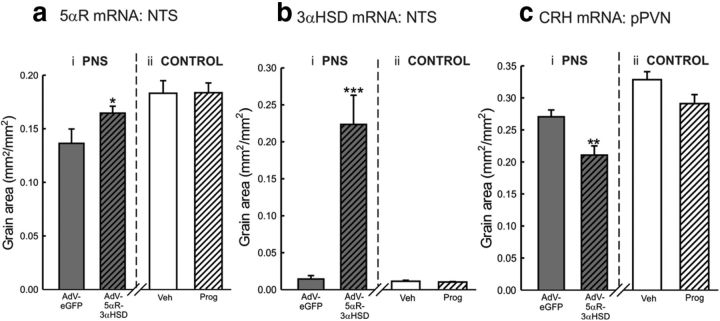

5α-Reductase mRNA expression in the NTS under basal conditions was significantly greater in the PNS rats treated with AdV-5αR/3α-HSD compared with the rats given the AdV-eGFP (t(10) = −1.9, p = 0.04, Student's t test; Fig. 6ai).

Figure 6.

Effect of 5α-reductase and 3α-HSD adenovirus injection into the NTS on gene expression under basal conditions in PNS female rats. Female PNS rats were injected with either Ad-eGFP or Ad-5αR and Ad-3αHSD. Nine days later, rats were killed by conscious decapitation and brains/brainstems removed for subsequent ISH to confirm the AdV treatment upregulated 5αR and 3α-HSD gene expression as planned. Two other groups were also included (but analyzed separately) to confirm progesterone treatment alone does not alter basal gene expression: a group of eight vehicle-treated female controls and a group of female controls administered progesterone, as given to the AdV-injected rats (dissolved in arachis oil; 5 mg/rat and 1 mg/rat s.c., ca., 24 and 5 h before killing, respectively). Quantification of (a) 5α-reductase (5αR) and (b) 3αHSD mRNA expression in the NTS, and (c) CRH mRNA expression in the parvocellular division of the PVN, in (ai, bi, ci) PNS females injected with either AdV-eGFP or AdV-5αR/3αHSD, and (aii, bii, cii) control females treated with either vehicle or progesterone (as above). In each case, values are group mean ± SEM and rat numbers are 6–8/group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus PNS/AdV-eGFP group (Student's t test/Mann–Whitney rank sum test).

3α-HSD mRNA

Basal expression of 3αHSD mRNA in the NTS was significantly greater in the PNS group administered the 5αR/3αHSD adenoviruses, compared with the PNS group given the control adenovirus (mean ranks of the AdV-eGFP group and the AdV-5αR/3αHSD group were 3.5 and 10, respectively; U = 0, Z = 2.93, p = 0.003, Mann–Whitney rank sum test; Fig. 6bi).

CRH mRNA

CRH mRNA expression in the pPVN was significantly lower under basal conditions in the PNS group administered the 5αR/3αHSD adenoviruses, compared with the PNS group given the control adenovirus (t(13) = 3.2, p = 0.006 Student's t test; Fig. 6ci).

Effect of progesterone treatment on basal gene expression in female rats

Progesterone treatment alone had no significant effect on the expression of 5α-reductase (t(14) = −0.04, p = 0.971, Student's t test; Fig. 6aii) or 3α-HSD (mean ranks of the vehicle group and the progesterone group were 9.4 and 7.6, respectively; U = 25, Z = 0.68, p = 0.497, Mann–Whitney rank sum test; Fig. 6bii) mRNA expression in the NTS, nor CRH mRNA expression in the pPVN (t(14) = 2.0, p = 0.07, Student's t test; Fig. 6cii) in control females.

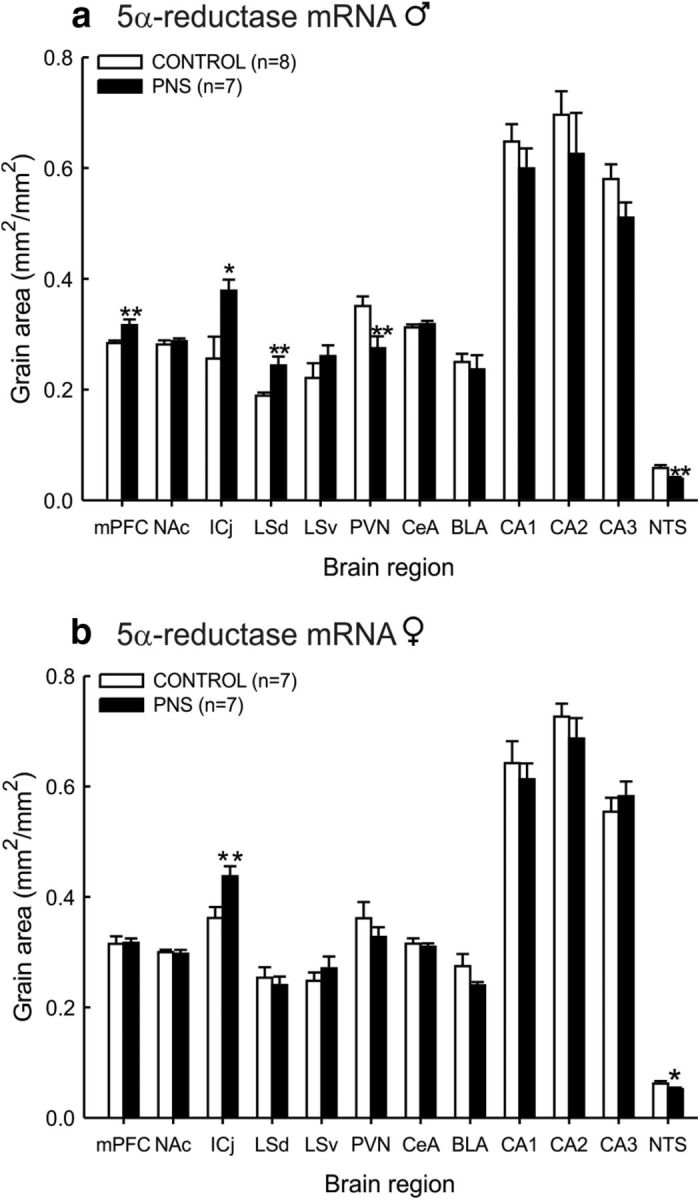

Effect of upregulating 5α-reductase and 3α-HSD expression in the NTS on HPA axis responses to IL-1β in female PNS rats

There was no difference in basal plasma ACTH concentration between the groups (Fig. 7a). There was a significant effect of treatment (F(1,40) = 4.7, p = 0.048; two-way RM ANOVA) and time (F(3,40) = 9.9, p < 0.001; two-way RM ANOVA) on ACTH secretion. The ACTH response to IL-1β was significantly attenuated in the PNS group transfected with AdV-5αR/3αHSD into the NTS compared with the PNS rats that received the control adenovirus (AdV-eGFP; p < 0.05; Fig. 7a).

Figure 7.

Effect of upregulating 5α-reductase and 3α-HSD mRNA expression in the NTS using adenoviruses on HPA axis responses to IL-1β in PNS rats. Female PNS rats were injected with either AdV-eGFP (the control enhanced green fluorescent protein, eGFP-expressing adenovirus) or AdV-5αR and AdV-3α-HSD (AdV-5αR/3αHSD) into the NTS. Both groups of PNS rats were administered progesterone (5 mg/rat and 1 mg/rat, s.c.; 20 and 2 h before IL-1β, respectively). On day 10, rats were blood sampled before and after IL-1β administration. A group of age-matched control females (that did not undergo NTS surgery) were blood sampled simultaneously and are included for comparison. Data from these control females are depicted by a dotted line. After two basal (B) blood samples (at t = −31 and −1 min), all rats were administered IL-1β (500 ng/kg, i.v.) at t = 0 min. Further blood samples were taken 15, 30, 60, and 90 min after IL-1β. (a) Plasma ACTH concentrations;*p < 0.05 versus mean B values in the same group; #p < 0.05 versus AdV-5αR/3αHSD group at the same time point (two-way RM ANOVA). b, Increase in plasma corticosterone concentrations 30 min after IL-1β administration; *p < 0.02 versus AdV-5αR/3αHSD group (Mann–Whitney rank sum test). ci, Quantification of CRH mRNA expression in the parvocellular division of the PVN (pPVN) 4 h after IL-1β administration, expressed as grain area/pPVN area (mm2/mm2); *p < 0.02 versus AdV-5αR/3αHSD group (Student's t test). cii–civ, Representative bright-field CRH mRNA ISH autoradiographs of coronal PVN sections from: (ci) control, (ciii) PNS/AdV-eGFP, and (civ) PNS/AdV-5αR/3αHSD rats. Scale bar, 100 μm. 3V, Third ventricle. In each case values are group means ± SEM. Group numbers are given in parentheses in the relevant key or within the data bars. Quantification of (di) 5α-reductase (5αR) and (ei) 3α-HSD mRNA expression in the NTS; *p < 0.005 versus AdV-eGFP group (Student's t test/Mann–Whitney rank sum test). d, Representative coronal sections through the medulla showing (dii) the extent of transfection within the NTS as indicated by eGFP distribution from a AdV-5αR/3αHSD transfected rat. Scale bar, 50 μm. diii, div, 5αR mRNA expression in the NTS from a (diii) PNS/AdV-eGFP and (div) PNS/AdV-5αR/3αHSD rat. e, Representative coronal sections through the medulla showing (eii, eiii) 3α-HSD mRNA expression in the NTS from a (eii) PNS/AdV-eGFP and (eiii) PNS/AdV-5αR/3αHSD rat. Scale bars,100 μm. 12, Hypoglossal nucleus; A2, A2 cell region of the NTS; AP, area postrema; CC, central canal; Gr, Gracile nucleus.

There was no significant difference in basal plasma corticosterone secretion. The increase in corticosterone secretion 30 min after IL-1β administration was significantly reduced in the AdV-5αR/3αHSD transfected PNS rats compared with AdV-eGFP transfected PNS rats (mean ranks of the AdV-eGFP group and the AdV-5αR/3αHSD group were 13.4 and 7, respectively; U = 18, Z = 2.36, p = 0.018, Mann–Whitney rank sum test; Fig. 7b).

Four hours after systemic IL-1β, CRH mRNA expression was significantly lower in the PNS rats injected with AdV-5αR/3αHSD into the NTS than in the AdV-eGFP transfected rats (t(21) = 2.39, p = 0.013, Student's t test; Fig. 7c). As expected, both 5αR (t(19) = −2.98, p = 0.004, Student's t test) and 3αHSD (mean ranks of the AdV-eGFP group and the AdV-5αR/3αHSD group were 7.67 and 15.44, respectively; U = 14, Z = −2.81, p = 0.005, Mann–Whitney rank sum test) mRNA expression in the NTS was significantly greater in the PNS rats transfected with AdV-5αR/3αHSD into the NTS than in the AdV-eGFP-transfected rats (Fig. 7d,e).

Discussion

This study has shown that the hyper-responsiveness of the HPA axis to IL-1β, in offspring of mothers exposed to social stress in late pregnancy is likely attributable to deficient neuroactive steroid production in specific discrete regions in the brain; however there are distinct sex differences in the mechanisms involved. Overall the data indicate multistage reduced inhibitory actions and production of 3β-diol on HPA axis stress responses in PNS males, and reduced actions and production of AP on HPA stress responses, localized to the NTS, in PNS females.

The well established sex difference in HPA axis responsivity to stress was evident: the ACTH response to IL-1β was greater in control females compared with control males. Given that the rats were gonadally intact, this is likely a consequence of the opposing actions of male and female gonadal steroids on HPA activity (Viau and Meaney, 1996; Figueiredo et al., 2007). The sex difference was not evident in the PNS rats, which may reflect changes in the sex steroid milieu in these rats. The effect of testosterone in reducing HPA axis responses to stress in males is mediated via DHT and is not a result of aromatization of testosterone to estradiol (Lund et al., 2004). However, the increased HPA axis responses to stress in PNS males could result from increased aromatization of testosterone, or a failure of testosterone to be converted into sufficient DHT in PNS males, as indicated by reduced 5αR gene expression.

AP administration significantly reduced the ACTH response to IL-1β in both control and PNS females, consistent with our previous finding that AP reduces stress responses in female rats (Brunton et al., 2009). AP acts as a positive allosteric modulator at GABAA receptors (Herd et al., 2007). As GABA neurons provide a major inhibitory input to CRH neurons in the PVN (Cullinan et al., 2008), AP may act upon GABAA receptors, within the PVN/peri-PVN to increase GABAergic tone to the CRH neurons and/or within limbic, forebrain, or brainstem regions to influence their output, and hence attenuate HPA axis responses. The sensitivity of GABAA receptors to modulation by AP depends upon several factors, including receptor subunit composition (Belelli and Lambert, 2005). Whether PNS alters GABAA receptor expression or subunit composition in females in such a way as to alter AP sensitivity is not known, though this has been described in males for other prenatal stress paradigms (Laloux et al., 2012) and in offspring exposed to excess corticosterone prenatally (Stone et al., 2001). AP may prevent stimulation of CRH neurons in the PVN by noradrenaline, because ascending noradrenergic inputs to the PVN from the NTS play a critical role in mediating the effects of IL-1β on HPA axis activity (Ericsson et al., 1994) and AP has been shown to attenuate noradrenergic stimulation of CRH release in vitro (Patchev et al., 1994). Alternatively, AP can activate an inhibitory endogenous opioid mechanism in the NTS (Brunton et al., 2009).

In contrast to females, AP had no effect on the ACTH response to IL-1β in males. Allopregnanolone was previously shown to reduce the ACTH and corticosterone response to air-puff stress in males (Patchev et al., 1996). The reason for the discrepancy could be the different doses of AP and/or different treatment regimens and/or different stress paradigms i.e., a transient emotional stressor, processed by rostral circuitry (Emmert and Herman, 1999), by contrast with the prolonged IL-1β stressor used here, which acts via the NTS (Ericsson et al., 1994). As the response to IL-1β in males was not affected by AP, the NTS is evidently not a site of AP action in males.

3β-Diol did however normalize the HPA axis response to IL-1β in PNS males. Unlike AP, 3β-diol evidently exerts its effects on HPA axis activity via ERβ (Lund et al., 2006). ERβ mRNA and ERβ immunoreactivity are expressed at high levels in PVN neurons, including those that synthesize CRH (Laflamme et al., 1998; Miller et al., 2004), providing a basis for direct modulation by 3β-diol of the activity of these neurons (Lund et al., 2006). ERβ is also expressed in the NTS (Shughrue et al., 1997). Given this region is critical in IL-1β signaling to the PVN, ERβ in the NTS could potentially permit indirect modulation of the HPA axis response to IL-1β by 3β-diol. Indeed, selective ERβ agonists reduce the stress-induced response of noradrenergic biosynthetic enzymes in the NTS (Serova et al., 2010) and HPA axis responses to stress (Weiser et al., 2009). Despite our finding that ERβ mRNA expression was downregulated in the PVN and NTS in PNS males, treatment with 3β-diol had central effects because it reduced pPVN CRH mRNA expression following systemic IL-1β. Notably, ERβ mRNA expression was also reduced in the magnocellular PVN in PNS male rats, where it is expressed in oxytocin neurons and is regulated by glucocorticoids (Somponpun et al., 2004). ERβ mediates stimulation of oxytocin gene expression by 3β-diol, leading to the suggestion that increased oxytocin release in the PVN mediates the inhibition of CRH responses to stress by 3β-diol (Sharma et al., 2012).

Exogenously administered 3β-diol was sufficient to overcome reduced expression of ERβ mRNA. However, under normal conditions reduced ERβ expression in the PVN and/or NTS may contribute to enhanced HPA axis responses to stress in PNS male rats. Confirmation is needed that 3β-diol production in the hypothalamus of PNS males is reduced as a consequence of the reduced 5α-reductase mRNA level measured in the PVN.

In males, PNS was associated with reduced expression of 5αR mRNA in the PVN and NTS, brain regions that provide excitatory drive to the HPA axis (Ericsson et al., 1994). Conversely, 5αR mRNA expression was significantly increased in PNS males in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the dorsal part of the lateral septum, limbic areas that exert an inhibitory influence over HPA axis activity (Herman et al., 2005; Radley et al., 2006). Locally produced 5α-reduced steroids may act to suppress IL-1β-stimulated HPA axis activity either by directly enhancing GABA inhibition within the PVN itself, inhibiting excitatory inputs to the PVN (e.g., the NTS A2 neurons) and/or by inhibiting PVN-projecting inhibitory GABA neurons upstream of the PVN (e.g., in the mPFC), thus reducing GABAergic tone to the CRH neurons. Because 5α-reductase is also involved in corticosterone metabolism, altered 5α-reductase expression, and hence altered glucocorticoid metabolism, may influence local glucocorticoid concentrations in the brain and potentially affect glucocorticoid feedback regulation of the HPA axis (Nixon et al., 2012).

In PNS females, 5αR mRNA expression was significantly reduced compared with control females only in the NTS. Thus, there is a distinct sex difference in the extent to which 5α-reductase gene expression is affected by prenatal stress, with more regions affected in the brains of PNS males. Nevertheless, downregulation of 5α-reductase mRNA expression in the NTS in the PNS females was associated with enhanced HPA axis responses to IL-1β. The mechanism underlying the sex difference in the effect of PNS on central 5α-reductase mRNA expression is not known, but this may result from differences in circulating androgens. Here we found increased plasma testosterone levels in PNS males suggesting increased secretion or impaired testosterone metabolism. Testosterone levels during postnatal development have been shown to critically influence 5α-reductase expression in the brain in adult males (Purves-Tyson et al., 2012; Sanchez et al., 2012), whereas DHT appears to play a more important role in females (Torres and Ortega, 2006). Moreover, hepatic 5α-reductase expression is programmed in early life by androgens, such that castration increases, whereas testosterone administration reduces hepatic 5α-reductase activity (Gustafsson and Stenberg, 1974). Consistent with this, hepatic 5α-reductase expression is also reduced in PNS adult males (Brunton et al., 2013). Thus, elevated circulating testosterone levels in PNS males (either during postnatal development or in adulthood) may contribute to reduced 5α-reductase expression in the liver and/or brain. To date there is no evidence for a role for progesterone or estrogen in regulating central 5α-reductase expression. Indeed we did not find any effect of progesterone administration on either 5α-reductase or 3α-HSD mRNA expression in the NTS in control females. Hence, we consider it unlikely that the elevated levels of circulating progesterone in the PNS females underlie the lower levels of 5α-reductase mRNA in the NTS of PNS females; however, we cannot rule this out. Intriguingly, human studies have highlighted reduced 5α-reductase activity as a key contributor to the programmed phenotype seen in individuals exposed to early life stress. Survivors of the World War II Holocaust display markedly reduced 5α-reductase type 1 activity, with the greatest reductions observed in those individuals who were youngest at exposure to the Holocaust (Yehuda et al., 2009) indicating a potential early life programming window.

The importance of reduced capacity for 5α-reduced neurosteroid production in the NTS was critically tested in PNS females by adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to upregulate expression of 5α-reductase and 3α-HSD in the NTS. Such treatment reduced basal CRH mRNA in the pPVN and normalized HPA axis responses to IL-1β challenge. Because we performed a double transfection it was not possible to assess the individual contribution of 5α-reductase and 3α-HSD in modulating the HPA axis response to IL-1β administration, however we interpret the effects of the combined AdV transfection as primarily due to upregulating 5αR expression, given that this is the rate-limiting enzyme (Russell and Wilson, 1994). Although we could not directly measure neurosteroid concentrations in the NTS following adenoviral transfection (as discussed in Materials and Methods), we assume increased synthesizing enzyme gene expression will result in increased neurosteroid production for local action on neurons. Hence, in PNS female rats, reduced 5α-reduced neurosteroid production in the NTS is a sufficient explanation for the hyper-responsiveness of the HPA axis in these rats to IL-1β.

In conclusion, 5α-reduced steroids can overwrite programming of hyperactive HPA axis responses to immune challenge in PNS male and female rats, but there are distinct sex differences in the central mechanisms involved. We propose that downregulation of neurosteroid production by programmed reduction of synthesizing enzyme gene expression in the brain underlies, at least in part, HPA axis hyper-responsiveness to a physical stressor in PNS offspring. However, further studies are required to test this inference by directly measuring neurosteroid production in discrete brain regions, and exposing the mechanisms underlying the altered gene expression. The findings here may be important in developing new rational treatments for human stress-related conditions designed to have sex-specific effects, either potentially based on using neurosteroid-based therapy or at least using measurement of impact of other treatments on sex-specific neurosteroid mechanisms to better understand how treatments work.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the BBSRC, UK: BB/C518957/1 (P.J.B., J.A.R.), BB/J004332/1 (P.J.B.), BB/G006156/1 (M.G., S.T.Y., D.M.); CAPES, Brazil (M.V.D.); British Heart Foundation (M.G., S.T.Y., D.M.); and The University of Malaya (HIR Award H-20001-E000086, D.M.). We thank Helen Cameron for technical assistance; undergraduate students, Robert Browning and Carly Schott assisted in some experiments; Megan Holmes (University of Edinburgh, UK) for providing the plasmids containing the rat CRH and ER-β cDNA; Marcel Karperien and Dr Jakomijn Hoogendam (University of Leiden, The Netherlands) for providing the plasmid containing 5α-reductase-1 cDNA; Trevor Penning (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) for providing the plasmid containing 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase cDNA; and J. Ian Mason (University of Edinburgh, UK) for providing cDNA encoding 5α-reductase-1.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided that the original work is properly attributed.

References

- Barker DJ, Hales CN, Fall CH, Osmond C, Phipps K, Clark PM. Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia (syndrome X): relation to reduced fetal growth. Diabetologia. 1993;36:62–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00399095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABA(A) receptor. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunton PJ, Russell JA. Prenatal social stress in the rat programmes neuroendocrine and behavioural responses to stress in the adult offspring: sex specific effects. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22:258–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunton PJ, Meddle SL, Ma S, Ochedalski T, Douglas AJ, Russell JA. Endogenous opioids and attenuated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis responses to immune challenge in pregnant rats. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5117–5126. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0866-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunton PJ, McKay AJ, Ochedalski T, Piastowska A, Rebas E, Lachowicz A, Russell JA. Central opioid inhibition of neuroendocrine stress responses in pregnancy in the rat is induced by the neurosteroid allopregnanolone. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6449–6460. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0708-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunton PJ, Sullivan KM, Kerrigan D, Russell JA, Seckl JR, Drake AJ. Sex-specific effects of prenatal stress on glucose homoeostasis and peripheral metabolism in rats. J Endocrinol. 2013;217:161–173. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagnone NA, Mellon SH. Neurosteroids: biosynthesis and function of these novel neuromodulators. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2000;21:1–56. doi: 10.1006/frne.1999.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan WE, Ziegler DR, Herman JP. Functional role of local GABAergic influences on the HPA axis. Brain Struct Funct. 2008;213:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do Rego JL, Seong JY, Burel D, Leprince J, Luu-The V, Tsutsui K, Tonon MC, Pelletier G, Vaudry H. Neurosteroid biosynthesis: enzymatic pathways and neuroendocrine regulation by neurotransmitters and neuropeptides. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:259–301. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmert MH, Herman JP. Differential forebrain c-fos mRNA induction by ether inhalation and novelty: evidence for distinctive stress pathways. Brain Res. 1999;845:60–67. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01931-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entringer S, Wüst S, Kumsta R, Layes IM, Nelson EL, Hellhammer DH, Wadhwa PD. Prenatal psychosocial stress exposure is associated with insulin resistance in young adults. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:498.e491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson A, Kovács KJ, Sawchenko PE. A functional anatomical analysis of central pathways subserving the effects of interleukin-1 on stress-related neuroendocrine neurons. J Neurosci. 1994;14:897–913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-02-00897.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo HF, Ulrich-Lai YM, Choi DC, Herman JP. Estrogen potentiates adrenocortical responses to stress in female rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1173–1182. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00102.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangloff A, Shi R, Nahoum V, Lin SX. Pseudo-symmetry of C19 steroids, alternative binding orientations, and multispecificity in human estrogenic 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. FASEB J. 2003;17:274–276. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0397fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson JA, Stenberg A. Irreversible androgenic programming at birth of microsomal and soluble rat liver enzymes active on androstene-3,17-dione and 5alpha-androstane-3alpha,17beta-diol. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:711–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa RJ, Burgess LH, Kerr JE, O'Keefe JA. Gonadal steroid hormone receptors and sex differences in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Horm Behav. 1994;28:464–476. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa RJ, Weiser MJ, Zuloaga DG. A role for the androgen metabolite, 5alpha-androstane-3beta,17beta-diol, in modulating oestrogen receptor beta-mediated regulation of hormonal stress reactivity. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21:351–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01840.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Seckl J. Glucocorticoids, prenatal stress and the programming of disease. Horm Behav. 2011;59:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd MB, Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Neurosteroid modulation of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;116:20–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP, Ostrander MM, Mueller NK, Figueiredo H. Limbic system mechanisms of stress regulation: hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laflamme N, Nappi RE, Drolet G, Labrie C, Rivest S. Expression and neuropeptidergic characterization of estrogen receptors (ERalpha and ERbeta) throughout the rat brain: anatomical evidence of distinct roles of each subtype. J Neurobiol. 1998;36:357–378. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(19980905)36:3<357::AID-NEU5>3.0.CO%3B2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laloux C, Mairesse J, Van Camp G, Giovine A, Branchi I, Bouret S, Morley-Fletcher S, Bergonzelli G, Malagodi M, Gradini R, Nicoletti F, Darnaudéry M, Maccari S. Anxiety-like behaviour and associated neurochemical and endocrinological alterations in male pups exposed to prenatal stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:1646–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JJ, Cooper MA, Simmons RD, Weir CJ, Belelli D. Neurosteroids: endogenous allosteric modulators of GABA(A) receptors. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:S48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund TD, Munson DJ, Haldy ME, Handa RJ. Androgen inhibits, while oestrogen enhances, restraint-induced activation of neuropeptide neurones in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:272–278. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-8194.2004.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund TD, Hinds LR, Handa RJ. The androgen 5alpha-dihydrotestosterone and its metabolite 5alpha-androstan-3beta, 17beta-diol inhibit the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal response to stress by acting through estrogen receptor beta-expressing neurons in the hypothalamus. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1448–1456. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3777-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellon SH, Vaudry H. Biosynthesis of neurosteroids and regulation of their synthesis. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2001;46:33–78. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(01)46058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WJ, Suzuki S, Miller LK, Handa R, Uht RM. Estrogen receptor (ER)beta isoforms rather than ERalpha regulate corticotropin-releasing hormone promoter activity through an alternate pathway. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10628–10635. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5540-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann ID, Toschi N, Ohl F, Torner L, Krömer SA. Maternal defence as an emotional stressor in female rats: correlation of neuroendocrine and behavioural parameters and involvement of brain oxytocin. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1016–1024. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon M, Upreti R, Andrew R. 5alpha-reduced glucocorticoids: a story of natural selection. J Endocrinol. 2012;212:111–127. doi: 10.1530/JOE-11-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patchev VK, Shoaib M, Holsboer F, Almeida OF. The neurosteroid tetrahydroprogesterone counteracts corticotropin-releasing hormone-induced anxiety and alters the release and gene expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the rat hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 1994;62:265–271. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patchev VK, Hassan AH, Holsboer DF, Almeida OF. The neurosteroid tetrahydroprogesterone attenuates the endocrine response to stress and exerts glucocorticoid-like effects on vasopressin gene transcription in the rat hypothalamus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15:533–540. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves-Tyson TD, Handelsman DJ, Double KL, Owens SJ, Bustamante S, Weickert CS. Testosterone regulation of sex steroid-related mRNAs and dopamine-related mRNAs in adolescent male rat substantia nigra. BMC Neurosci. 2012;13:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-13-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley JJ, Arias CM, Sawchenko PE. Regional differentiation of the medial prefrontal cortex in regulating adaptive responses to acute emotional stress. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12967–12976. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4297-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW, Wilson JD. Steroid 5α-reductase: two genes/two enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:25–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez P, Torres JM, del Moral RG, de Dios Luna J, Ortega E. Steroid 5alpha-reductase in adult rat brain after neonatal testosterone administration. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:81–86. doi: 10.1002/iub.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seckl JR. Prenatal glucocorticoids and long-term programming. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:U49–U62. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.151U049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serova LI, Harris HA, Maharjan S, Sabban EL. Modulation of responses to stress by estradiol benzoate and selective estrogen receptor agonists. J Endocrinol. 2010;205:253–262. doi: 10.1677/JOE-10-0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D, Handa RJ, Uht RM. The ERbeta ligand 5alpha-androstane, 3beta,17beta-diol (3beta-diol) regulates hypothalamic oxytocin (Oxt) gene expression. Endocrinology. 2012;153:2353–2361. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shughrue PJ, Lane MV, Merchenthaler I. Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta mRNA in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:507–525. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19971201)388:4<507::AID-CNE1>3.0.CO%3B2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somponpun SJ, Holmes MC, Seckl JR, Russell JA. Modulation of oestrogen receptor-beta mRNA expression in rat paraventricular and supraoptic nucleus neurones following adrenal steroid manipulation and hyperosmotic stimulation. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:472–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckelbroeck S, Jin Y, Gopishetty S, Oyesanmi B, Penning TM. Human cytosolic 3alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily display significant 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity: implications for steroid hormone metabolism and action. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10784–10795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone DJ, Walsh JP, Sebro R, Stevens R, Pantazopolous H, Benes FM. Effects of pre- and postnatal corticosterone exposure on the rat hippocampal GABA system. Hippocampus. 2001;11:492–507. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taves MD, Ma C, Heimovics SA, Saldanha CJ, Soma KK. Measurement of steroid concentrations in brain tissue: methodological considerations. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2011;2:39. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2011.00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres JM, Ortega E. Steroid 5alpha-reductase isozymes in the adult female rat brain: central role of dihydrotestosterone. J Mol Endocrinol. 2006;36:239–245. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viau V, Meaney MJ. The inhibitory effect of testosterone on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress is mediated by the medial preoptic area. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1866–1876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01866.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viau V, Bingham B, Davis J, Lee P, Wong M. Gender and puberty interact on the stress-induced activation of parvocellular neurosecretory neurons and corticotropin-releasing hormone messenger ribonucleic acid expression in the rat. Endocrinology. 2005;146:137–146. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock M. The long-term behavioural consequences of prenatal stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1073–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser MJ, Wu TJ, Handa RJ. Estrogen receptor-beta agonist diarylpropionitrile: biological activities of R- and S-enantiomers on behavior and hormonal response to stress. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1817–1825. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, Bierer LM, Andrew R, Schmeidler J, Seckl JR. Enduring effects of severe developmental adversity, including nutritional deprivation, on cortisol metabolism in aging holocaust survivors. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:877–883. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]