Abstract

Estrogen interacts with estrogen receptors (ERs) to induce vasodilation, but the ER subtype and post-ER relaxation pathways are unclear. We tested if ER subtypes mediate distinct vasodilator and intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) responses via specific relaxation pathways in the endothelium and vascular smooth muscle (VSM). Pressurized mesenteric microvessels from female Sprague-Dawley rats were loaded with fura-2, and the changes in diameter and [Ca2+]i in response to 17β-estradiol (E2) (all ERs), PPT (4,4′,4′′-[4-propyl-(1H)-pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl]-tris-phenol) (ERα), diarylpropionitrile (DPN) (ERβ), and G1 [(±)-1-[(3aR*,4S*,9bS*)-4-(6-bromo-1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-3a,4,5,9b-tetrahydro:3H-cyclopenta(c)quinolin-8-yl]-ethanon] (GPR30) were measured. In microvessels preconstricted with phenylephrine, ER agonists caused relaxation and decrease in [Ca2+]i that were with E2 = PPT > DPN > G1, suggesting that E2-induced vasodilation involves ERα > ERβ > GPR30. Acetylcholine caused vasodilation and decreased [Ca2+]i, which were abolished by endothelium removal or treatment with the nitric oxide synthase blocker Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) and the K+ channel blockers tetraethylammonium (nonspecific) or apamin (small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel) plus TRAM-34 (1-[(2-chlorophenyl)diphenylmethyl]-1H-pyrazole) (intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel), suggesting endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor–dependent activation of KCa channels. E2-, PPT-, DPN-, and G1-induced vasodilation and decreased [Ca2+]i were not blocked by L-NAME, TEA, apamin plus TRAM-34, iberiotoxin (large conductance Ca2+- and voltage-activated K+ channel), 4-aminopyridine (voltage-dependent K+ channel), glibenclamide (ATP-sensitive K+ channel), or endothelium removal, suggesting an endothelium- and K+ channel–independent mechanism. In endothelium-denuded vessels preconstricted with phenylephrine, high KCl, or the Ca2+ channel activator Bay K 8644 (1,4-dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-5-nitro-4-[2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-3-pyridinecarboxylic acid methyl ester), ER agonist–induced relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i were with E2 = PPT > DPN > G1 and not inhibited by the guanylate cyclase inhibitor ODQ [1H-(1,2,4)oxadiazolo(4,3-a)quinoxalin-1-one], and showed a similar relationship between decreased [Ca2+]i and vasorelaxation, supporting direct effects on Ca2+ entry in VSM. Immunohistochemistry revealed ERα, ERβ, and GPR30 mainly in the vessel media and VSM. Thus, in mesenteric microvessels, ER subtypes mediate distinct vasodilation and decreased [Ca2+]i (ERα > ERβ > GPR30) through endothelium- and K+ channel–independent inhibition of Ca2+ entry mechanisms of VSM contraction.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is less common in premenopausal women than age-matched men, and these gender differences disappear after menopause, suggesting cardiovascular protective effects of female sex hormones, such as estrogen [17β-estradiol (E2)] (Yang and Reckelhoff, 2011; Howard and Rossouw, 2013; Khalil, 2013). Also, earlier clinical observations suggested that climacteric women receiving E2 containing menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) to reduce menopausal symptoms have lower rates of CVD, supporting the vascular benefits of E2 (Reslan and Khalil, 2012; Gurney et al., 2014). The beneficial vascular effects of E2 have been ascribed to modification of circulating lipoproteins, inhibition of the vascular accumulation of collagen, and vasodilator effects on the endothelium and vascular smooth muscle (VSM) (Mendelsohn, 2002; Khalil, 2013). In the endothelium, E2 causes genomic stimulation of cell growth and upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS) and cyclooxygenase (COX) (Dubey et al., 2004; Orshal and Khalil, 2004) as well as rapid nongenomic production of NO, prostacyclin (PGI2), and hyperpolarization factor (Herrington et al., 1994; Chakrabarti et al., 2014). These endothelium-derived factors then reduce VSM intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), inhibit Ca2+-dependent mechanisms of VSM contraction, and cause vascular relaxation. E2 could also cause endothelium-independent genomic inhibition of VSM proliferation and downregulation of VSM Ca2+ channels as well as rapid nongenomic inhibition of Ca2+ entry into VSM and Ca2+-dependent VSM contraction (Murphy and Khalil, 1999; Khalil, 2013).

Despite evidence from earlier clinical observations and experimental studies, randomized clinical trials in postmenopausal women with or without CVD have shown no vascular benefits from MHT (Reslan and Khalil, 2012; Gurney et al., 2014). Several factors could have contributed to the lack of vascular benefits of MHT, including preexisting CVD, the subject’s age, and age-related changes in estrogen receptor (ER) amount, distribution, integrity, and post-ER signaling mechanisms (Reslan and Khalil, 2012; Gurney et al., 2014). These observations have made it imperative to thoroughly investigate the vascular ERs, their tissue distribution in the arterial tree, and their downstream post-ER signaling mechanisms.

ERs include two classic subtypes, ERα and ERβ, which could mediate some of the vasodilator effects of E2 (Pare et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2002; Smiley and Khalil, 2009) and a membrane-bound G protein–coupled ER (GPR30, GPER) with potential vasodilator properties (Revankar et al., 2005; Meyer et al., 2010; Lindsey et al., 2011, 2013a; Murata et al., 2013). We have recently shown regional-specific ERα-, ERβ-, and GPR30-mediated vasorelaxation in the aorta, carotid, and main renal and mesenteric artery of the female rat (Reslan et al., 2013). However, the specific ER subtype and post-ER endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent signaling pathways that mediate vasodilation in systemic vessels, in general, and resistance microvessels, in particular, are not clearly understood. For instance, while it is largely believed that VSM [Ca2+]i is a major determinant of vascular contraction (Khalil and van Breemen, 1990), the role of ER subtypes in modulating [Ca2+]i and the Ca2+-dependent mechanisms of vascular contraction have not been directly examined. Dissection of these ER-mediated mechanisms is particularly important in the mesenteric microvascular bed as it contributes substantially to peripheral vascular resistance (Christensen and Mulvany, 1993). The present study aimed to test the hypothesis that ER subtypes mediate distinct changes in microvascular reactivity and [Ca2+]i by promoting specific post-ER relaxation mechanisms in the endothelium and VSM. We used mesenteric microvessels from female rats and specific ER agonists to investigate whether 1) ER subtypes mediate distinct vasodilator responses in mesenteric microvessels; 2) ER-mediated vasodilation involves parallel changes in underlying microvascular [Ca2+]i; 3) ER-mediated vasodilation and changes in [Ca2+]i involve downstream post-ER endothelium-dependent pathways and/or endothelium-independent effects on VSM; and 4) ER-mediated activity reflects specific localization of ER subtypes in the endothelium and/or VSM layer of the vascular wall.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Tissue Preparation.

Female Sprague-Dawley rats (12 weeks of age, 250–300 g) from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) were maintained on ad libitum standard rat chow and tap water in a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Because vascular reactivity can be influenced by sex hormones during the estrous cycle (Dalle Lucca et al., 2000a,b) and to control for endocrine confounders, all experiments were conducted in female rats during estrus. The estrous cycle was determined by taking a vaginal smear with a pasteur pipette, and estrus was verified when the smear contained primarily anucleated cornified squamous cells prior to all experiments (Yener et al., 2007; Mazzuca et al., 2010). Rats were euthanized by inhalation of CO2, the abdominal cavity was opened, and the small intestine, adjacent mesentery, and mesenteric arterial arcade were excised and placed in ice-cold oxygenated Krebs solution. With the aid of a dissection microscope, small third-order mesenteric arteries were carefully isolated and cleaned of surrounding fat and connective tissue and used for microvascular functional studies. Some of the mesenteric vessels were stored at −80°C for immunohistochemical analysis. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the guidelines of the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals.

Microvessel Cannulation and Pressurization.

Segments of small mesenteric microvessels, with an outside diameter of ∼300 μm and length of ∼4–5 mm, were transferred to a temperature-controlled perfusion chamber, mounted between two glass micropipettes (cannulas), and secured with 10–0 ophthalmic nylon monofilament (Living Systems Instrumentation, Burlington, VT) (Chen and Khalil, 2008; Mazzuca et al., 2013). The microvessel in the perfusion chamber was placed on an inverted microscope (TE300; Nikon, Melville, NY). A stopcock distal to the vessel was closed, and the proximal end was connected to a pressure transducer and pressure servo control system (Living Systems Instrumentation). The microvessel was gradually pressurized to 60 mm Hg and maintained at constant pressure with the pressure servo control unit. The microvessel was bathed in 5-ml Krebs solution bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37°C and continuously superfused with fresh Krebs at a rate of 1 ml/min using a peristaltic mini pump (Master-Flex; Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL). Drugs were added abluminally to the bath solution. The vessel was allowed to equilibrate for 60 minutes before testing its functional responsiveness to a high KCl depolarizing solution, phenylephrine (Phe), and acetylcholine (ACh). For endothelium-intact microvessels, extreme care was taken throughout the tissue isolation, dissection, and cannulation procedure to minimize injury to the endothelium. Microvessels were unacceptable if they showed leaks or failed to produce maintained constriction to KCl or at least 80% relaxation to ACh (10−5 M).

Microvessels were continuously monitored using a video camera and monitor, and the microvessel diameter was measured using an automatic edge-detection system (Crescent Electronics, Sandy, UT) (Chen and Khalil, 2008; Mazzuca et al., 2013). Snap pictures of the microvessel were taken at rest (control), during steady-state submaximal constriction to Phe (6 × 10−6 M), and at maximal vasodilation to the ER agonist (10−5 M) using a digital camera (Cool-Snap; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ).

Fura-2 Loading and [Ca2+]i Recording.

For the measurement of [Ca2+]i, microvessels were incubated in Krebs solution containing the cell permeable Ca2+ indicator fura-2/AM (5 µM) and the mild detergent cremophor EL (0.25%) for 1 hour (Chen and Khalil, 2008; Mazzuca et al., 2013). The microvessel was washed three times in Krebs to remove extracellular fura-2/AM and incubated in Krebs for an additional 30 minutes to allow de-esterification of the intracellularly trapped fura-2/AM into the Ca2+-sensitive fura-2. The fura-2–loaded microvessel was excited alternately at 340 and 380 nm, the emitted light was collected at 510 nm every 1 second, and the fluorescence signal was measured using Felix fluorescence data acquisition and analysis software (Photon Technology International, Birmingham, NJ). The 340/380 fluorescence ratio represented the changes in [Ca2+]i, and the signal-to-noise ratio was improved by averaging 10 consecutive 340/380 ratio readings.

Simultaneous Measurement of Microvessel Diameter and [Ca2+]i.

Our previous observations and preliminary experiments in third-order mesenteric microvessels showed that the Phe concentration-vasoconstriction curve was very steep such that 3 × 10−6 M caused only 30–40% constriction, while 6 × 10−6 M caused ∼70% submaximal contraction (Mazzuca et al., 2010, 2014). In our initial experiments with 30–40% preconstriction to Phe 3 × 10−6 M, we could not detect stepwise relaxing effects of increasing concentrations of ER agonists with accuracy, such that the effects of the ER agonist appeared almost like a slanting slope. This made it extremely difficult to discern the concentration-dependent relaxing effects, maximal response, and EC50 of the different ER agonists. In comparison, when Phe 6 × 10−6 M was used to produce ∼70% submaximal preconstriction, stepwise relaxing effects of increasing concentrations of ER agonists could be observed. Our previous studies on mesenteric microvessels have also shown concentration-dependent constriction to KCI (16–96 mM), and that 51 mM KCI produced ∼70% submaximal constriction (Mazzuca et al., 2014). Therefore, we used the same submaximal Phe and KCl concentrations and preconstriction levels to compare the relaxing effects of ACh and different ER agonists in all experiments.

To test the role of ERs, microvessels were preconstricted with Phe and then stimulated with increasing concentrations (10−9 to 10−5 M) of E2 (activator of all ERs), PPT (4,4′,4′′-[4-propyl-(1H)-pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl]-tris-phenol) (selective ERα agonist) (Sun et al., 1999; Stauffer et al., 2000), diarylpropionitrile (DPN) (selective ERβ agonist) (Harrington et al., 2003), or G1 [(±)-1-[(3aR*,4S*,9bS*)-4-(6-bromo-1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-3a,4,5,9b-tetrahydro-3H cyclopenta(c)quinolin-8-yl]-ethanone] (GPR30 agonist) (Filardo et al., 2000; Kleuser et al., 2008; Reslan et al., 2013), and the simultaneous changes in microvessel diameter and 340/380 ratio, indicative of [Ca2+]i), were recorded. In cell-based assays, the reported EC50 and Ki are 0.3 and 0.13 nM for E2, 200 pM and 0.4 nM for PPT, 0.85 and 0.61 nM for DPN, and 2 and 11 nM for G1 (Stauffer et al., 2000; Bologa et al., 2006; Weiser et al., 2009). PPT binding affinity is 410 times greater for ERα over ERβ (Stauffer et al., 2000). DPN binds to ERβ with a 70-fold higher affinity compared with ERα (Meyers et al., 2001; Harrington et al., 2003). G1 displays no activity for ERα and ERβ at concentrations up to 10 μM and selectively binds to GPR30 (Bologa et al., 2006). For construction of concentration-relaxation response curves, each ER agonist concentration was added, the vascular relaxation was observed until it reached steady state or for 5 minutes, whichever happened first, and then the next concentration was added.

We previously tested the specificity of E2, PPT, DPN, and G1, and found that treating mesenteric vessels with the vehicle ethanol (0.1% for E2) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (0.1% for PPT, DPN, and G1) did not cause any significant changes in Phe contraction, suggesting that the observed effects of E2, PPT, DPN, and G1 were caused by the specific compound and not by the vehicle (Reslan et al., 2013). Also, as we previously reported in the main mesenteric artery (Reslan et al., 2013) and to further assess the specificity of ER agonists, we tested if the effects of PPT, DPN, and G1 on Phe-induced constriction were prevented in mesenteric microvessels pretreated with the ERα antagonist MPP [1,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-methyl-5-[4-(2-piperidinylethoxy)phenol]-1H-pyrazole], ERβ antagonist PHTPP (4-[2-phenyl-5,7-bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazolo(1,5-a)pyrimidin-3-yl]phenol), and the GPR30 antagonist G15 [(3aS*,4R*,9bR*)-4-(6-bromo-1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-3a,4,5,9b-3H-cyclopenta(c)quinolone], respectively.

To test for endothelial function, microvessels were submaximally preconstricted with Phe and then stimulated with increasing concentrations of ACh (10−9 to 10−5 M) added cumulatively at 2-minute intervals, and the simultaneous changes in microvessel diameter and [Ca2+]i (340/380 ratio) were recorded. To elucidate the vasodilator mediator released during stimulation with ACh, E2, PPT, DPN, and G1, vascular relaxation and [Ca2+]i were measured in microvessels treated with the NOS inhibitor Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) (3 × 10−4 M), COX inhibitor indomethacin (INDO) (10−5 M), and TEA (30 mM), a nonselective blocker of K+ channels (Ghatta et al., 2006; Feletou and Vanhoutte, 2009). Because the small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (SKCa) and intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (IKCa) may play a specific role in mesenteric microvessel endothelium-dependent relaxation (Crane et al., 2003), the role of the hyperpolarization pathway in ER-mediated relaxation was further investigated by testing the effects of the SKCa blocker apamin (10−7 M) plus IKCa blocker TRAM-34 (1-[(2-chlorophenyl)diphenylmethyl]-1H-pyrazole) (10−6 M). To further assess if ER-mediated relaxation involves activation of VSM K+ channels, such as the large conductance Ca2+- and voltage-activated K+ channel (BKCa), voltage-dependent K+ channel (KV), and ATP-sensitive K+ channel (KATP), E2, PPT, DPN, and G1-induced relaxation of Phe contraction was examined in microvessels pretreated with the BKCa blocker iberiotoxin (10−8 M), KV blocker 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) (10−3 M), and KATP blocker glibenclamide (10−5 M). The concentrations of K+ channel inhibitors were selected based on previous studies in our laboratory (Raffetto et al., 2007).

To test for endothelium-independent ER-mediated effects on VSM, the endothelium was removed by gently injecting air bubbles (∼0.3 ml) through the microvessel. Endothelium removal was confirmed by the absence of vasodilator response to ACh (10−5 M), and the integrity of VSM function was confirmed by the maintained constrictor response to Phe (10−5 M). The effects of ER agonists were then measured in endothelium-denuded microvessels preconstricted with Phe (6 × 10−6 M). To test if ER-mediated relaxation and changes in [Ca2+]i involve changes in VSM guanylate cyclase activity and cGMP, we tested the effects of the guanylate cyclase inhibitor ODQ [1H-(1,2,4)oxadiazolo(4,3-a)quinoxalin-1-one] (10−5 M) on ER-mediated responses. Also, membrane depolarization by high KCl is known to activate Ca2+ influx into VSM through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Khalil and van Breemen, 1990; Murphy and Khalil, 1999). To test for ER-mediated effects on Ca2+ entry into VSM, the effects of ER agonists were tested on endothelium-denuded microvessels preconstricted with 51 mM KCl. To further assess if ER-mediated vasodilation involves inhibition of Ca2+ entry into VSM, we tested the effects of ER agonists on microvessel constriction and [Ca2+]i induced by the L-type Ca2+ channel activator Bay K 8644 (1,4-dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-5-nitro-4-[2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-3-pyridinecarboxylic acid methyl ester). In these experiments, endothelium-denuded microvessels were first stimulated with 24 mM KCI to induce little membrane depolarization, which we have shown to produce negligible contraction (Mazzuca et al., 2014), and then Bay K 8644 (10−6 M) was added to open L-type Ca2+ channels and cause maintained vasoconstriction (Kanmura et al., 1984; Asano et al., 1986). Microvessels were then treated with the specific ER agonist, and the percentage relaxation and changes in [Ca2+] were measured.

Immunohistochemistry.

To determine the tissue distribution of ERs, mesenteric arteries were cryopreserved in Tissue-Tek 4583 optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) (Sakura Finetek Inc., Torrance, CA) and stored at −80°C. Because of difficulties in embedding small third-order microvessels in OCT and keeping them straight upright and their lumen open to fill with enough OCT, we used first-order mesenteric arterial segments upstream in the mesenteric arterial arcade. Cross-sectional cryosections (6 μm) were prepared from the OCT-embedded mesenteric artery and placed on glass slides (Stennett et al., 2009). Immediately before immunostaining, cryosections were thawed and fixed in ice-cold acetone for 10 minutes and rehydrated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.25% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes at room temperature (22°C). Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 1.5% H2O2 solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in methanol (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 minutes, and nonspecific binding was blocked in 10% horse serum in PBS for 30 minutes. Tissue sections were incubated with polyclonal ERα, ERβ, or GPR30 antibody (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) for 1 hour and then washed with PBS. Tissue sections were then incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG for 30 minutes, rinsed with PBS, and then incubated with avidin-labeled peroxidase (VectaStain Elite ABC Kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 minutes, followed by a rinse in PBS for 5 minutes. Positive labeling was visualized using diaminobenzadine and appeared as brown spots. Negative control slides were run simultaneously with no primary antibody and showed no detectable immunostaining. Sections were counterstained with Gills hematoxylin for 30 seconds and cover slipped with cytoseal 60 mounting medium (Richard-Allen Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI). Stained sections were coded and labeled in a blinded fashion. Images of tissue sections were acquired on a Nikon microscope with digital camera mount using the same magnification, light intensity, exposure time, and camera gain using Nikon NIS Elements software, and then analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Images were analyzed by two independent investigators blinded to the ER subtype. To measure the amount of ER subtype in the intima, media, and adventitia, the number of pixels in the specific vascular layer was first defined and transformed into the area in μm2 using a calibration bar. The number of brown spots (pixels) representing ERα, ERβ, and GPR30 in each vascular layer was then counted and presented as number of pixels/μm2 (Stennett et al., 2009).

Solution and Drugs.

Krebs solution contained (in mM) 120 NaCl, 5.9 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 11.5 dextrose, 2.5 CaCl2, and 1.2 MgCl2 at pH 7.4, and was bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. High KCl (24 or 51 mM) or TEA solution (30 mM) was prepared as normal Krebs but with an equimolar substitution of NaCl with KCl or TEA, respectively. Stock solutions of Phe (10−1 M), ACh (10−1 M), L-NAME (10−1 M), 4-AP (10−1 M), apamin (10−3 M) (Sigma-Aldrich), and iberiotoxin (10−5 M) (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) were prepared in deinoized water. Stock solutions of E2 (10−2 M) (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared in 100% ethanol, and PPT, DPN, G1, the ERα antagonist MPP, ERβ antagonist PHTPP, GPR30 antagonist G15 (10−1 M), Bay K 8644 (10−2 M), TRAM-34 (10−2 M) (Tocris, Ellisville, MO), INDO (10−2 M), glibenclamide (10−1 M) (Sigma-Aldrich), ODQ (10−1) (Calbiochem), and the Ca2+ indicator fura-2/AM (10−3 M) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were prepared in DMSO. The final concentration of ethanol or DMSO in the experimental solution was < 0.1%. All other chemicals were of reagent grade or better.

Statistical Analysis.

Cumulative data in microvessels from 4 to 15 different rats were presented as means ± S.E.M., with the n value representing the number of rats. Microvascular relaxation was measured as [(relaxation diameter – Phe or KCI preconstriction diameter)/(resting diameter – Phe or KCI preconstriction diameter)] × 100. To compare the effects of different vasodilators, concentration-dependent relaxations were expressed as the percentage of maximum relaxation to the specific vasodilator, concentration-relaxation curves were constructed, and sigmoidal nonlinear regression curves were fitted to the data points using the least-squares method with Prism software (v.6.01; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). For primary comparisons of microvessels treated with different concentrations of ACh and different ER agonists, data points were first analyzed using two-way repeated measures analysis of variance. When a significant interaction was observed with analysis of variance, both the maximum response and (−log EC50) drug concentration evoking half-maximal response (pD2 values) were determined and further analyzed using Bonferroni’s post hoc correction for multiple comparisons. To compare the effects of certain concentrations of a specific ER agonist and the immunohistochemistry data, a student’s unpaired t test was used for comparison of two means. Differences were considered statistically significant if P < 0.05.

Results

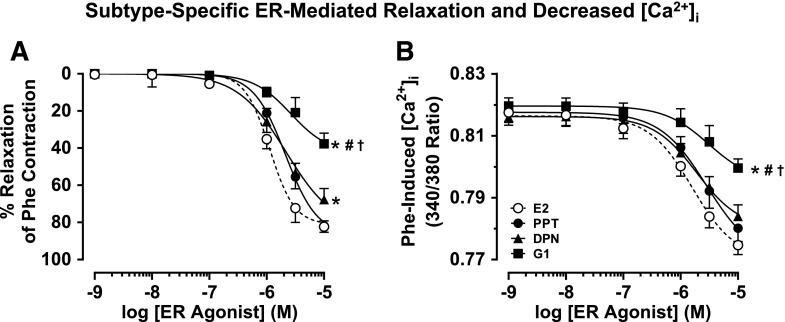

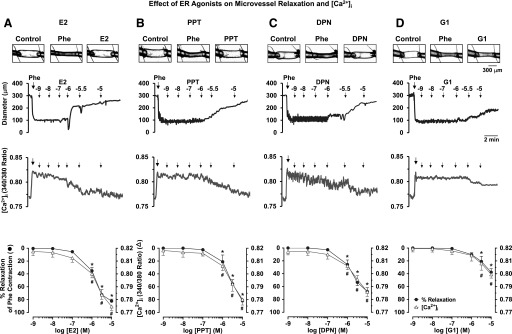

In mesenteric microvessels preconstricted with Phe (6 × 10−6 M), E2 caused a concentration-dependent increase in diameter and simultaneous decrease in the 340/380 fluorescence ratio, indicative of a decrease in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 1A). The ERα agonist PPT (Fig. 1B), ERβ agonist DPN (Fig. 1C), and GPR30 agonist G1 (Fig. 1D) caused a distinct concentration-dependent increase in diameter and decrease in [Ca2+]i. Cumulative data analysis showed that the maximal vasodilation induced by E2 (82.3 ± 3.0%) was not significantly different from that induced by PPT (81.8 ± 2.6%), was significantly greater than that induced by DPN (67.7 ± 6.0%), and was far greater than the small dilation induced by G1 (37.7 ± 5.6%) (Fig. 2A; Table 1). Also, E2 caused the largest decrease in [Ca2+]i followed by PPT, DPN, and G1 (Fig. 2B; Table 1). The concentrations of ER agonists used to elicit relaxation were based on our previous studies on a rat main mesenteric artery, which have shown that a pD2 for E2 is 4.08 ± 0.56, a pD2 for PPT is 5.46 ± 1.08, a pD2 for DPN is 5.77 ± 0.85, and a pD2 for G1 is 8.26 ± 1.16 (Reslan et al., 2013). Consistent with our previous observations (Reslan et al., 2013), lower concentrations of the ER agonists (10−13 to 10−10 M) did not show measureable changes in microvessel diameter or [Ca2+]i and therefore were not shown. Also, in agreement with previous ex vivo studies (Lindsey et al., 2013; Reslan et al., 2013), micromolar concentrations of ER agonists (10−6 to 10−5 M) were needed to elicit maximal microvascular relaxation. In accordance with our observations in the main mesenteric artery (Reslan et al., 2013), the inhibitory effects of PPT, DPN, and G1 on Phe contraction were prevented in microvessels pretreated with the ERα antagonist MPP, ERβ antagonist PHTPP, and GPR30 antagonist G15, respectively (Table 1), supporting specificity of the relaxation effects of ER agonists.

Fig. 1.

Effect of ER agonists on vasodilation and [Ca2+]i in mesenteric microvessels of female rat. Images of microvessels were acquired at rest (control), after steady-state vasoconstriction to Phe (6 × 10−6 M), and then after maximal relaxation to the specific ER agonist (10−5 M). Representative tracings illustrate the simultaneous changes in microvessel diameter and 340/380 ratio (indicative of [Ca2+]i) in response to increasing concentrations (10−9 to 10−5 M) of E2 (activator of all ERs) (A), PPT (ERα agonist) (B), DPN (ERβ agonist) (C), or G1 (GPR30 agonist) (D). Cumulative E2-, PPT-, DPN-, G1-induced relaxation and changes in [Ca2+]i (340/380 ratio) were presented as means ± S.E.M., n = 8–15. *Percentage relaxation at ER agonist specific concentration is significantly different (P < 0.05) from the effect of preceding concentration or 10−9 M concentration. #Effect on [Ca2+]i at ER agonist specific concentration is significantly different (P < 0.05) from the effect of preceding concentration or 10−9 M concentration.

Fig. 2.

Subtype-specific ER-mediated vasodilation and underlying [Ca2+]i in mesenteric microvessels of female rat. Microvessels were preconstricted with Phe (6 × 10−6 M) treated with increasing concentrations (10−9 to 10−5 M) of E2 (all ERs), PPT (ERα agonist), DPN (ERβ agonist), or G1 (GPR30 agonist), and the percentage relaxation of Phe constriction (A) and underlying [Ca2+]i (B) were measured. Data points represent means ± S.E.M., n = 8–15. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) from corresponding measurements in E2-treated microvessels. #Significantly different (P < 0.05) from corresponding measurements in PPT-treated vessels. †Significantly different (P < 0.05) from corresponding measurements in DPN-treated vessels.

TABLE 1.

Maximal ACh and ER agonist-induced relaxation and changes in [Ca2+]i in mesenteric microvessels of female rat

To facilitate comparison with the percentage relaxation effect, the percentage change in microvascular [Ca2+]i was measured as [(Phe or KCI preconstriction [Ca2+]i – maximal relaxation [Ca2+]i)/(Phe or KCI preconstriction [Ca2+]i – basal [Ca2+]i)] × 100. Data represent means ± S.E.M., n = 6–15.

| ACh |

E2 |

PPT |

DPN |

G1 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max relaxation of Phe contraction (%) | |||||

| Control | 93.3 ± 2.6 | 82.3 ± 3.0 | 81.8 ± 2.6 | 67.7 ± 6.0a | 37.7 ± 5.6a–c |

| + L-NAME + INDO | 91.7 ± 3.3 | 81.8 ± 3.1 | 75.4 ± 7.1 | 62.4 ± 5.2a | 39.0 ± 6.7a–c |

| + L-NAME + INDO + TEA | 12.2 ± 4.8d | 75.4 ± 4.1 | 72.0 ± 4.5 | 66.8 ± 6.3a | 34.5 ± 11.2a–c |

| + L-NAME + INDO + apamin + TRAM-34 | 2.1 ± 1.1d | 77.1 ± 4.3 | 75.7 ± 7.4 | 62.1 ± 2.5a | 29.9 ± 8.5a–c |

| + L-NAME + INDO + iberiotoxin | 91.1 ± 5.4 | 82.0 ± 8.3 | 76.2 ± 6.1 | 64.7 ± 4.1a | 36.4 ± 4.3a–c |

| + L-NAME + INDO + 4-AP | 90.1 ± 4.2 | 76.8 ± 5.9 | 77.3 ± 6.7 | 66.9 ± 3.8a | 36.8 ± 8.2a–c |

| + L-NAME + INDO + glibenclamide | 89.0 ± 7.0 | 77.9 ± 8.4 | 73.3 ± 7.8 | 65.6 ± 3.0a | 35.4 ± 8.6a–c |

| −Endo | 1.5 ± 0.4d | 81.7 ± 6.5 | 79.2 ± 7.8 | 66.4 ± 5.0a | 36.3 ± 5.3a–c |

| −Endo + ODQ | 2.1 ± 0.6d | 81.7 ± 1.4 | 79.5 ± 4.3 | 66.7 ± 3.1a | 36.2 ± 5.0a–c |

| +ER antagonist | MPP, 2.4 ± 2.9d | PHTPP, 3.5 ± 2.2d | G15, 2.3 ± 2.0d | ||

| Max change in Phe [Ca2+]i (%) | |||||

| Control | 94.6 ± 5.3 | 89.2 ± 6.1 | 82.2 ± 2.2 | 64.2 ± 8.9a | 35.3 ± 5.2a–c |

| + L-NAME + INDO | 91.4 ± 4.6 | 84.1 ± 3.2 | 76.9 ± 6.4 | 61.7 ± 5.3a | 36.4 ± 6.8a–c |

| + L-NAME + INDO + TEA | 4.3 ± 3.3d | 80.6 ± 4.3 | 77.0 ± 8.0 | 63.1 ± 7.1a | 33.9 ± 9.8a–c |

| + L-NAME + INDO + apamin + TRAM-34 | 2.8 ± 3.0d | 79.2 ± 4.6 | 72.6 ± 4.5 | 62.8 ± 6.5a | 30.7 ± 5.9a–c |

| + L-NAME + INDO + iberiotoxin | 89.0 ± 6.8 | 86.0 ± 5.3 | 79.4 ± 3.1 | 62.9 ± 5.8a | 32.7 ± 8.5a–c |

| + L-NAME + INDO + 4-AP | 90.8 ± 2.6 | 88.7 ± 1.8 | 80.6 ± 4.7 | 61.9 ± 6.2a | 34.9 ± 7.1a–c |

| + L-NAME + INDO + glibenclamide | 93.3 ± 4.3 | 90.1 ± 5.2 | 80.3 ± 5.9 | 63.6 ± 4.9a | 35.8 ± 5.0a–c |

| −Endo | 1.0 ± 0.9d | 82.4 ± 7.2 | 76.9 ± 6.6 | 63.7 ± 5.9a | 34.5 ± 6.0a–c |

| −Endo + ODQ | 1.6 ± 0.8d | 81.7 ± 5.3 | 78.9 ± 7.5 | 67.8 ± 9.1a | 33.2 ± 8.2a–c |

| +ER antagonist | MPP, 2.2 ± 3.2d | PHTPP, 2.3 ± 2.7d | G15, 3.8 ± 2.0d | ||

| pD2 (−log EC50) relaxation of Phe contraction | |||||

| Control | 6.27 ± 0.10 | 5.93 ± 0.06 | 5.75 ± 0.09 | 5.86 ± 0.06 | 5.68 ± 0.07a |

| + L-NAME + INDO | 5.82 ± 0.11d | 5.82 ± 0.05 | 5.68 ± 0.09 | 5.77 ± 0.06 | 5.60 ± 0.07a |

| + L-NAME + INDO + TEA | N.D. | 5.83 ± 0.05 | 5.63 ± 0.09 | 5.71 ± 0.07 | 5.50 ± 0.11a |

| + L-NAME + INDO + apamin + TRAM-34 | N.D. | 5.82 ± 0.05 | 5.66 ± 0.07 | 5.73 ± 0.06 | 5.50 ± 0.09a |

| + L-NAME + INDO + iberiotoxin | 5.86 ± 0.08d | 5.79 ± 0.08 | 5.74 ± 0.10 | 5.72 ± 0.09 | 5.49 ± 0.10a |

| + L-NAME + INDO + 4-AP | 5.88 ± 0.06d | 5.80 ± 0.10 | 5.73 ± 0.08 | 5.72 ± 0.05 | 5.48 ± 0.09a |

| + L-NAME + INDO + glibenclamide | 5.85 ± 0.10d | 5.83 ± 0.15 | 5.68 ± 0.11 | 5.70 ± 0.10 | 5.46 ± 0.12a |

| −Endo | N.D. | 5.81 ± 0.05 | 5.72 ± 0.05 | 5.70 ± 0.06 | 5.60 ± 0.08a |

| −Endo + ODQ | N.D. | 5.80 ± 0.07 | 5.65 ± 0.08 | 5.65 ± 0.06 | 5.60 ± 0.05a |

| pD2 (−log EC50) change in Phe [Ca2+]i | |||||

| Control | 6.50 ± 0.19 | 5.90 ± 0.08 | 5.78 ± 0.10 | 5.86 ± 0.10 | 5.71 ± 0.18 |

| + L-NAME + INDO | 6.01 ± 0.12d | 5.88 ± 0.08 | 5.77 ± 0.14 | 5.86 ± 0.09 | 5.70 ± 0.20 |

| + L-NAME + INDO + TEA | N.D. | 5.87 ± 0.14 | 5.75 ± 0.18 | 5.83 ± 0.23 | 5.70 ± 0.21 |

| + L-NAME + INDO + apamin + TRAM-34 | N.D. | 5.88 ± 0.12 | 5.72 ± 0.18 | 5.80 ± 0.14 | 5.69 ± 0.22 |

| + L-NAME + INDO + iberiotoxin | 6.05 ± 0.18d | 5.84 ± 0.09 | 5.76 ± 0.10 | 5.82 ± 0.16 | 5.58 ± 0.18 |

| + L-NAME + INDO + 4-AP | 6.00 ± 0.13d | 5.85 ± 0.07 | 5.71 ± 0.08 | 5.81 ± 0.13 | 5.61 ± 0.19 |

| + L-NAME + INDO + glibenclamide | 5.99 ± 0.14d | 5.88 ± 0.13 | 5.74 ± 0.05 | 5.79 ± 0.17 | 5.68 ± 0.08 |

| −Endo | N.D. | 5.81 ± 0.07 | 5.75 ± 0.12 | 5.80 ± 0.15 | 5.70 ± 0.15 |

| −Endo + ODQ | N.D. | 5.83 ± 0.11 | 5.67 ± 0.11 | 5.81 ± 0.10 | 5.66 ± 0.10 |

| Effect on KCl responses | |||||

| Max relaxation (%) | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 78.7 ± 3.7 | 77.4 ± 3.6 | 64.3 ± 5.0a | 25.5 ± 10a–c |

| Max change in KCl [Ca2+]i (%) | 2.9 ± 3.3 | 80.3 ± 4.7 | 78.5 ± 6.8 | 65.1 ± 7.2a | 30.5 ± 8.1a–c |

| pD2 relaxation | N.D. | 5.62 ± 0.04 | 5.61 ± 0.03 | 5.53 ± 0.06 | 5.48 ± 0.07a |

| pD2 [Ca2+]i | N.D. | 5.71 ± 0.10 | 5.69 ± 0.14 | 5.65 ± 0.14 | 5.70 ± 0.16 |

N.D., not determined because of inability to generate sigmoidal curves and pD2 values due to negligible relaxation.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) from corresponding measurements in E2-treated microvessels.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) from corresponding measurements in PPT-treated vessels.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) from corresponding measurements in DPN-treated vessels.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) from corresponding control responses in the absence of blockers/antagonists.

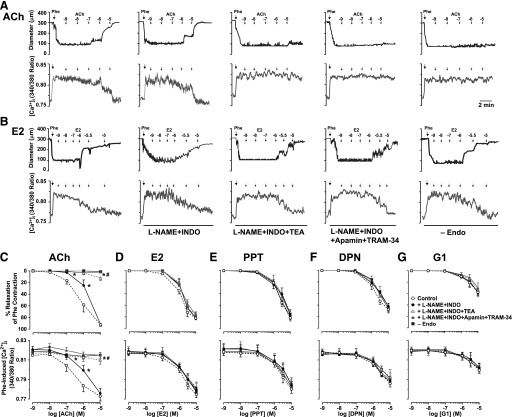

To determine the role of endothelium-derived factors in ER-mediated relaxation, we first examined the response to ACh. In endothelium-intact vessels preconstricted with Phe, ACh caused concentration-dependent relaxation and simultaneous decrease in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3, A and C; Table 1). To test for the contribution of NO, PGI2, and the hyperpolarization factor, ACh concentration-relaxation curves were repeated in the presence of the NOS inhibitor L-NAME, COX inhibitor INDO, and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) and K+ channel blockers (Fig. 3, A and C). When compared with the control ACh response, L-NAME + INDO did not affect the maximal ACh-induced relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3, A and C; Table 1). Further analysis of cumulative ACh data and pD2 values showed a significant shift to the right in both the concentration-relaxation and concentration-decreased [Ca2+]i curves in L-NAME + INDO treated versus control microvessels (Fig. 3, A and C; Table 1). The remaining L-NAME + INDO–resistant and apparently EDHF-mediated component of ACh relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i was almost abolished by the K+ channel blocker TEA (nonselective) and apamin (SKCa) plus TRAM-34 (IKCa) (Fig. 3, A and C; Table 1). In microvessels treated with L-NAME + INDO, blockade of VSM K+ channels with iberiotoxin (BKCa), 4-AP (KV), or glibenclamide (KATP) did not alter ACh sensitivity or maximal relaxation or decrease in [Ca2+]i (Table 1), suggesting little role of BKCa, KV, and KATP in ACh-induced relaxation of mesenteric microvessels. ACh-induced relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i were abolished in endothelium-denuded vessels (Fig. 3, A and C; Table 1), further supporting a role of endothelium-derived relaxing factors.

Fig. 3.

Effect of blocking NO, PGI2, and hyperpolarization factor on ACh and ER-mediated relaxation and underlying [Ca2+]i in mesenteric microvessels of female rat. Representative tracings illustrate simultaneous changes in microvessel diameter and 340/380 ratio (indicative of [Ca2+]i) in microvessels preconstricted with Phe (6 × 10−6 M) and then treated with ACh (A) or E2 (B) in the absence or presence of L-NAME (3 × 10−4 M) plus INDO (10−6 M) and TEA (30 mM), SKCa blocker apamin (10−7 M) plus IKCa blocker TRAM-34 (10−6 M), or in endothelium-denuded vessels. Cumulative concentration-dependent relaxation curves and underlying [Ca2+]i were constructed in response to increasing concentrations (10−9 to 10−5 M) of ACh (C), E2 (all ERs) (D), PPT (ERα agonist) (E), DPN (ERβ agonist) (F), or G1 (GPR30 agonist) (G). Data points represent means ± S.E.M., n = 8–15. −Endo experiments were n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 versus control measurements in the absence of blockers. #P < 0.05 versus measurements in the presence of L-NAME + INDO.

To investigate the role of endothelium-derived factors in ER-mediated responses, the effects of E2 (Fig. 3, B and D), PPT (Fig. 3E), DPN (Fig. 3F), and G1 (Fig. 3G) on microvascular dilation and [Ca2+]i were examined in the presence of blockers of NOS, COX, and EDHF. In the presence of L-NAME + INDO, E2, PPT, DPN, and G1 caused a concentration-dependent relaxation and decrease in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3, B and D–G; Table 1) that were not different from the control ER-mediated responses, suggesting little role of eNOS and COX activation or NO and PGI2 production. Also, in the presence of additional pretreatment with TEA or apamin + TRAM-34, E2, PPT, DPN, and G1 caused concentration-dependent relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3, B and D–G; Table 1) that were not different from the respective control levels, suggesting little role of K+ channels, particularly endothelial SKCa and IKCa. Furthermore, in the presence of additional blockade of smooth muscle K+ channels with iberiotoxin (BKCa), 4-AP (KV), or glibenclamide (KATP), E2, PPT, DPN, and G1 caused concentration-dependent relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i that were not different from the respective control levels (Table 1), suggesting little role of smooth muscle K+ channels BKCa KV or KATP. In endothelium-denuded vessels preconstricted with Phe, E2, PPT, DPN, and G1 caused a concentration-dependent relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i that were similar to the control effects in endothelium-intact vessels (Fig. 3, B and D–G; Table 1), supporting a role of endothelium-independent mechanisms.

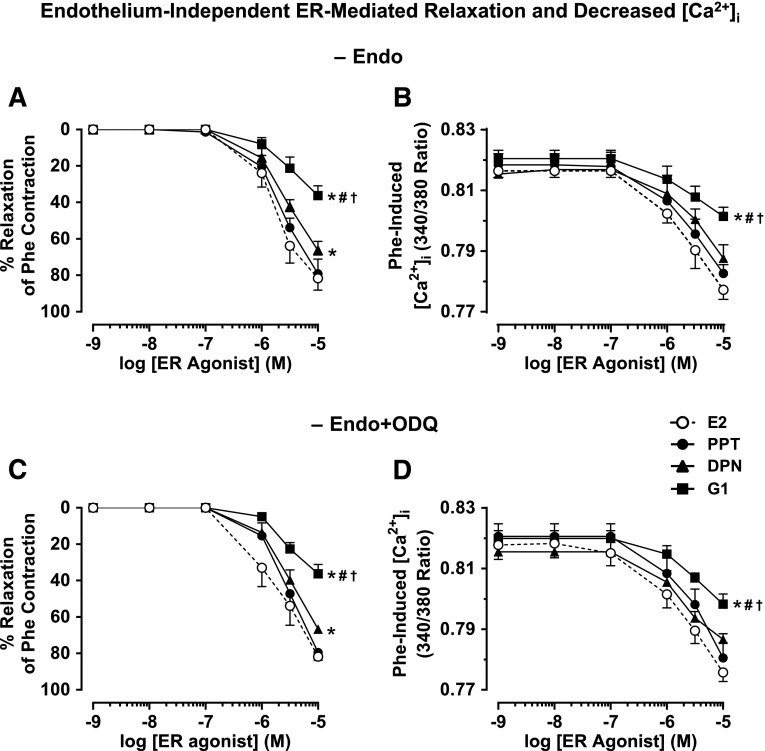

To further compare the endothelium-independent component of ER-mediated responses, in endothelium-denuded microvessels preconstricted with Phe, the ER agonists induced microvascular relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i, where E2 = PPT > DPN > G1 (Fig. 4, A and B; Table 1). To test if the endothelium-independent ER-mediated VSM relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i involve changes in VSM guanylate cyclase activity and cGMP, in endothelium-denuded microvessels pretreated with the guanylate cyclase inhibitor ODQ (10−5 M) and preconstricted with Phe, ER agonists induced relaxation and decrease in [Ca2+]i, where E2 = PPT > DPN > G1 (Fig. 4, C and D; Table 1), and were similar to the control effects of ER agonists in endothelium-denuded vessels without ODQ (Fig. 4, A and B; Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Endothelium-independent ER-mediated relaxation and underlying [Ca2+]i in mesenteric microvessels of female rat. Endothelium-denuded microvessels were preconstricted with Phe (6 × 10−6 M) (A and B) or Phe in the presence of guanylate cyclase inhibitor ODQ (10−5 M) (C and D) and then treated with increasing concentrations (10−9 to 10−5 M) of E2 (all ERs), PPT (ERα agonist), DPN (ERβ agonist), or G1 (GPR30 agonist), and the percentage relaxation of Phe contraction (A and C) and underlying [Ca2+]i (B and D) were measured. Cumulative data represent means ± S.E.M., n = 6–12. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) from corresponding measurements in E2-treated microvessels. #Significantly different (P < 0.05) from corresponding measurements in PPT-treated vessels. †Significantly different (P < 0.05) from corresponding measurements in DPN-treated vessels.

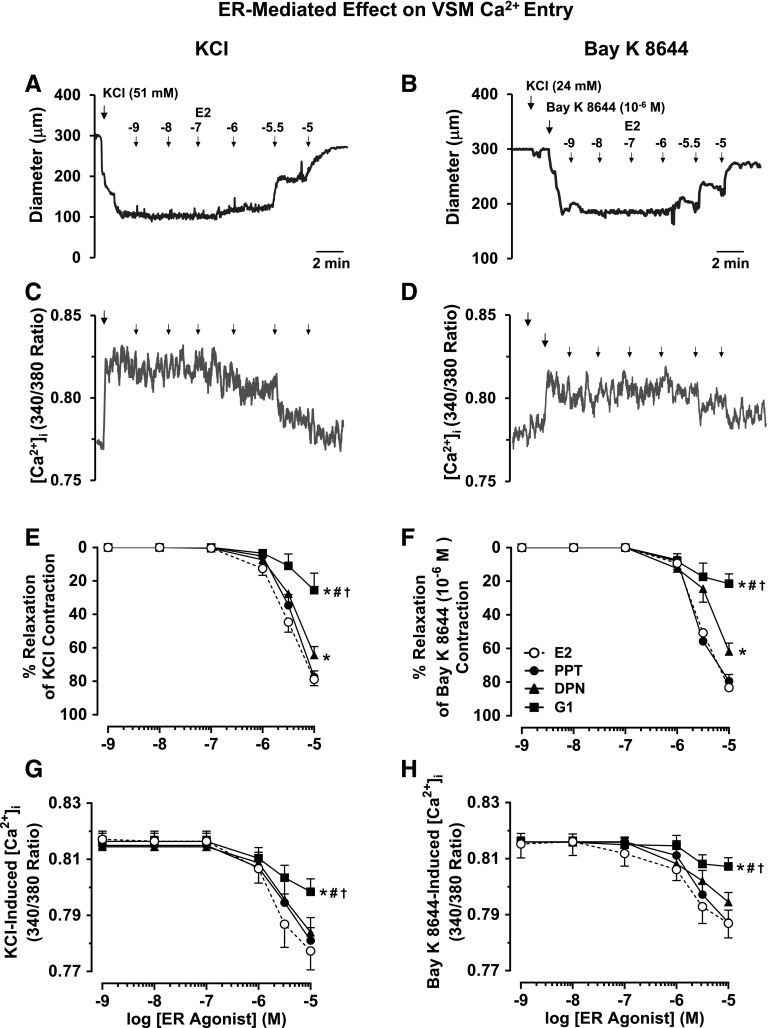

Membrane depolarization by high KCl is known to mainly stimulate Ca2+ entry into VSM through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Khalil and van Breemen, 1990; Murphy and Khalil, 1999). To investigate if ER-mediated vasodilation involves inhibition of Ca2+ entry into VSM, in endothelium-denuded vessels preconstricted with 51 mM KCl, E2, PPT, DPN, and G1 caused concentration-dependent relaxation and decrease in [Ca2+]i, where E2 = PPT > DPN > G1 (Fig. 5, A, C, E, and G; Table 1). E2, PPT, DPN, and G1 also caused concentration-dependent decrease of Bay K 8644–induced vasoconstriction and [Ca2+]i, where E2 = PPT > DPN > G1 (Fig. 5, B, D, F, and H), supporting that the ER-mediated vasorelaxation effects are due to inhibition of VSM Ca2+ entry via Ca2+ channels.

Fig. 5.

ER-mediated relaxation and decreased VSM Ca2+ entry. Representative tracings illustrate simultaneous changes in microvessel diameter and 340/380 ratio (indicative of [Ca2+]i) in endothelium-denuded vessels preconstricted with KCI (51 mM) alone (A and C) or with 24 mM KCI followed by Bay K 8644 (10−6 M) to open L-type Ca2+ channels and cause maintained vasoconstriction (B and D), and then treated with E2. Cumulative concentration-dependent relaxation curves and underlying [Ca2+]i were constructed in response to increasing concentrations (10−9 to 10−5 M) of E2 (all ERs), PPT (ERα agonist), DPN (ERβ agonist), or G1 (GPR30 agonist) in microvessels pretreated with KCI (51 mM) alone (E and G) or KCI (24 mM) plus Bay K 8644 (F and H). Data points represent means ± S.E.M., n = 4–12. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) from corresponding measurements in E2-treated microvessels. #Significantly different (P < 0.05) from corresponding measurements in PPT-treated vessels. †Significantly different (P < 0.05) from corresponding measurements in DPN-treated vessels.

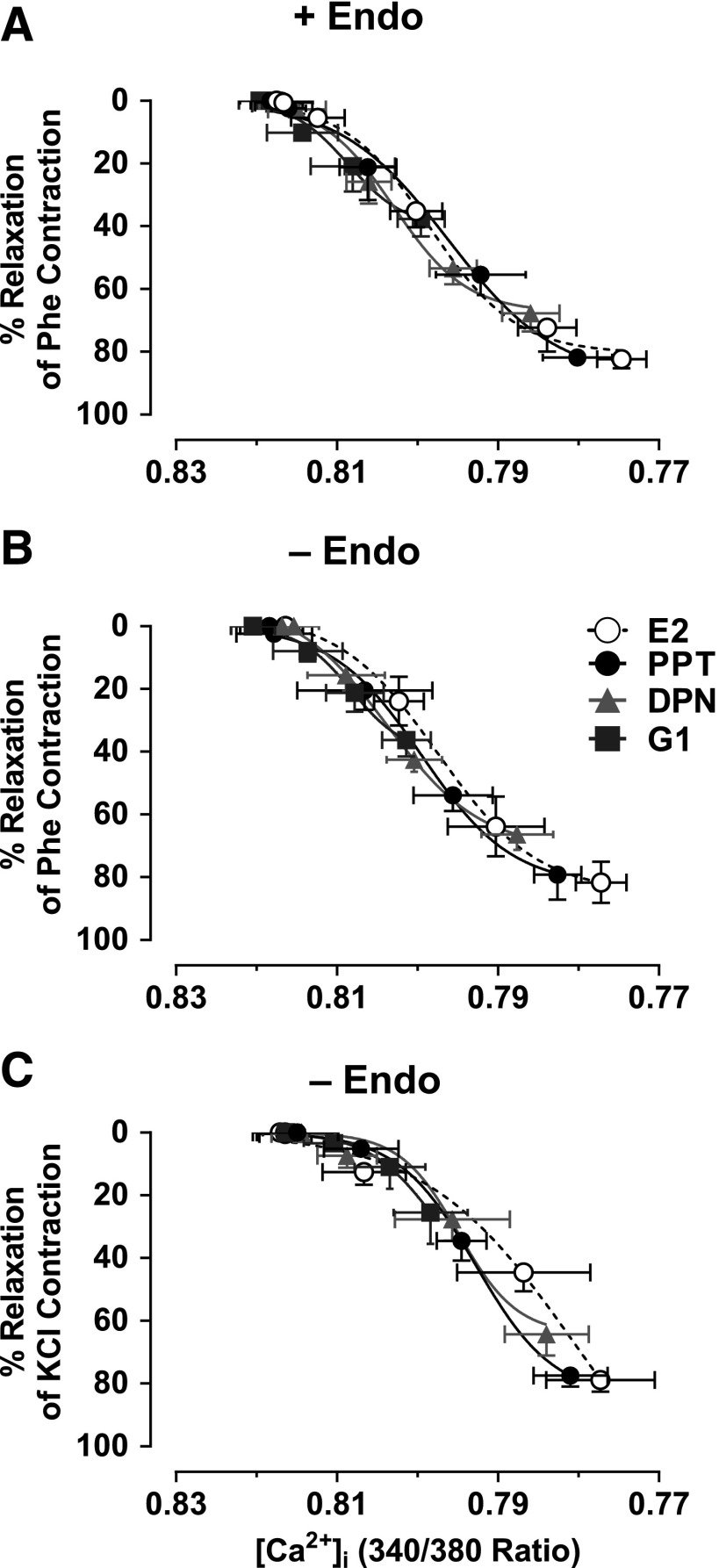

To further examine if ER-mediated responses are largely dependent on changes in vascular [Ca2+]i or involve changes in other [Ca2+]i-sensitization mechanisms, the E2, PPT, DPN, and G1-induced microvascular relaxation and underlying [Ca2+]i observed in endothelium-intact microvessels preconstricted with Phe (Fig. 2) and in endothelium-denuded microvessels preconstricted with Phe or KCl (Figs. 4 and 5) were used to construct and compare the relationship between decreased [Ca2+]i and microvascular relaxation (Fig. 6). In endothelium-intact vessels preconstricted with Phe, E2, PPT, DPN, and G1 caused decreases in [Ca2+]i associated with stepwise microvascular relaxation (Fig. 6A). E2, PPT, DPN, and G1 induced similar effects and almost superimposed the relationship between decreased [Ca2+]i and microvascular relaxation, suggesting an inhibition of similar [Ca2+]i-dependent mechanisms. In endothelium-denuded vessels preconstricted with Phe (Fig. 6B) or KCI (Fig. 6C), E2, PPT, DPN, or G1 caused a similar decreased [Ca2+]i-relaxation relationship, further suggesting inhibition of similar [Ca2+]i-dependent mechanisms in VSM.

Fig. 6.

Relationships between decreased [Ca2+]i and relaxation in response to ER agonists in mesenteric microvessels of female rat. The microvascular relaxation and underlying [Ca2+]i data observed in endothelium-intact microvessels preconstricted with Phe (6 × 10−6 M) (Fig. 2) and endothelium-denuded microvessels preconstricted with Phe or KCl (51 mM) (Figs. 4 and 5) were used to construct the relationship between decreased [Ca2+]i and microvascular relaxation in response to E2 (all ERs), PPT (ERα agonist), DPN (ERβ agonist), and G1 (GPR30 agonist) in endothelium-intact microvessels preconstricted with Phe (A) and endothelium-denuded microvessels preconstricted with Phe (B) or KCI (51 mM) (C). To facilitate comparison, data points were best fitted using a nonlinear regression and least-squares method.

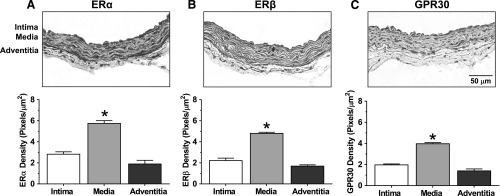

To determine the tissue distribution of ERs, immunohistochemical analysis revealed ERα, ERβ, and GPR30 brown immunostaining in the intima, media, and adventitia of the mesenteric artery (Fig. 7). ERα (Fig. 7A), ERβ (Fig. 7B), and GPR30 immunostaining (Fig. 7C) was significantly greater in the media and VSM layer compared with the endothelium and intima layer or the adventitia.

Fig. 7.

ER subtype distribution in mesenteric artery of female rat. Cryosections (6 μm) of mesenteric artery were labeled with ERα, ERβ, or GPR30 antibodies (1:1000) and the ABC Elite Kit and counterstained with hematoxylin. Positive ER labeling was visualized as brown immunostaining. For quantification of ERα (A), ERβ (B), or GPR30 (C) in the specific vascular layer (intima, media, and adventitia), the number of pixels in each layer was first defined and transformed into the area in μm2 using a calibration bar. The number of brown spots (pixels) representing ERα, ERβ, and GPR30 in each vascular layer was then counted and presented as number of pixels/μm2. Bar graphs represent means ± S.E.M., n = 4–6. *P < 0.05 versus intima or adventitia.

Discussion

The present study shows that 1) in mesenteric microvessels of the female rat, ERs mediate subtype-specific vasodilation and a parallel decrease in [Ca2+]i, with the response to E2 (all ERs) > PPT (ERα) > DPN (ERβ) > G1 (GPR30); 2) the ER-mediated vasodilation and decreased [Ca2+]i are endothelium independent as they are not inhibited by blockers of NOS, COX, and EDHF or endothelium removal; 3) ER-mediated responses are not blocked by the guanylate cyclase inhibitor and appear to involve direct inhibition of Ca2+ entry in VSM; and 4) prominent ERα, ERβ, and GPR30 distribution is observed in the mesenteric arterial media and VSM layer.

E2 induces vasodilation in multiple vascular beds through various genomic and nongenomic endothelium-dependent and -independent pathways (Mendelsohn, 2002; Reslan et al., 2013). Therefore, the lack of vascular benefits of E2 in clinical MHT trials has made it important to examine the vascular ERs and downstream post-ER signaling mechanisms. We have shown that ER-mediated vasodilation exhibits regional differences in cephalic, thoracic, and abdominal arteries (Reslan et al., 2013). In the present study, we assessed the effects of the ER agonists PPT (ERα), DPN (ERβ), and G1 (GPR30) in small mesenteric microvessels because they contribute to vascular resistance (Christensen and Mulvany, 1993).

E2 and PPT caused a similar relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i, suggesting that E2-mediated vasodilation largely involves ERα. DPN caused measurable relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i, suggesting a possible role of ERβ in E2-mediated microvascular relaxation. This is consistent with reports that ERα and ERβ mediate many of the genomic effects of E2 and that surface membrane ERα and ERβ could mediate rapid vasodilator effects of E2 (Pare et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2002; Smiley and Khalil, 2009). In comparison, G1 caused less relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i, suggesting a lesser role of GPR30 in E2-induced microvascular dilation. These observations are consistent with reports that in the female rat main mesenteric artery, E2 causes relaxation largely through ERα, PPT produces greater relaxation than DPN or G1, and G1 causes little relaxation of the female Sprague-Dawley rat aorta (Ma et al., 2010; Reslan et al., 2013). Other studies have shown that G1 produces vasodilation similar to E2 in the carotid artery of a Sprague-Dawley rat of both genders (Broughton et al., 2010) and the mesenteric artery of a male Sprague-Dawley rat (Haas et al., 2009) and female mRen2.Lewis rat (Lindsey et al., 2011). These differences may be related to the rat strain, regional differences in ER distribution along the arterial tree (D’Angelo and Osol, 1993; van Drongelen et al., 2012), and hormonal changes during the estrous cycle, which could influence vascular function, and some of the studies in female rats did not report the stage of the estrous cycle or technique used to measure microvascular function, i.e., wire myography versus pressurized microvessels.

In search for the mechanism of ER-mediated vasodilation, ER agonists caused a concentration-dependent decrease in [Ca2+]i that paralleled the vasodilation profile, i.e., E2 = PPT > DPN > G1, suggesting that ER-mediated vasodilation is due to decreased [Ca2+]i. To test if ER-mediated vasodilation and decreased [Ca2+]i involve endothelium-derived NO, PGI2, or EDHF, we first showed that ACh-induced relaxation and decrease in [Ca2+]i were abolished by endothelium removal. Although the NOS inhibitor L-NAME did not inhibit maximal ACh relaxation or decreased [Ca2+]i, it reduced the sensitivity to ACh, suggesting a role of NO in modulating the sensitivity to ACh. The remaining L-NAME + INDO–resistant component of ACh-induced relaxation is likely due to an EDHF. In the classic EDHF pathway, ACh-induced transient increase in [Ca2+]i activates Ca2+-dependent SKCa and IKCa in endothelial cells. Endothelial cell hyperpolarization is transferred to VSM via microdomains or myoendothelial gap junctions (Sandow et al., 2012), leading to VSM hyperpolarization, inhibition of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, and vascular relaxation (Busse et al., 2002). We found that the L-NAME + INDO–resistant ACh relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i were inhibited by the K+ channel blocker TEA (nonselective) or apamin (SKCa) plus TRAM-34 (IKCa), supporting a role of SKCa and IKCa in decreasing [Ca2+]i and promoting microvascular relaxation.

In comparison with ACh, ER-mediated relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i do not appear to involve endothelium-derived vasodilators because 1) ER agonist-induced relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i were not blocked by L-NAME + INDO, suggesting little role of eNOS and COX or NO and PGI2. 2) In the presence of K+ channel blockers TEA or apamin + TRAM-34, ER agonists still caused relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i, suggesting that EDHF, SKCa, and IKCa channels are not involved. Also, ER agonist-induced relaxation was not inhibited by iberiotoxin, 4-AP, or glibenclamide, suggesting little role of VSM BKCa, KV, or KATP channels. 3) Endothelium removal did not affect ER agonist-induced vasodilation and decreased [Ca2+]i. 4) Immunohistochemistry revealed a greater amount of ERα, ERβ, and GPR30 in the mesenteric arterial media and VSM layer than the intima and endothelial cell layer or the adventitia. These observations support that in mesenteric vessels, ER-mediated relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i involve an endothelium-independent mechanism in VSM.

VSM contraction is triggered by increases in [Ca2+]i (Khalil and van Breemen, 1990; Berridge, 2008). The observation that ER agonists decreased Phe-induced maintained vasoconstriction and [Ca2+]i suggests inhibition of Ca2+ entry into VSM. Also, in endothelium-denuded microvessels, ER agonists inhibited the maintained constriction and [Ca2+]i induced by high KCl, supporting inhibition of Ca2+ entry into VSM through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. This is consistent with reports that E2 decreased KCl-induced Ca2+ influx in an endothelium-denuded rat aorta and coronary artery and rat aortic VSM cells (Freay et al., 1997; Crews and Khalil, 1999; Murphy and Khalil, 2000) and reduced capacitative Ca2+ influx through inhibition of L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Castillo et al., 2006). The present study provides the first evidence that in mesenteric microvessels, ERα and ERβ cause vasodilation by reducing VSM [Ca2+]i and could mediate most of the decreased microvascular [Ca2+]i induced by E2.

An important question is how ER agonists decrease VSM [Ca2+]i. Some studies suggest indirect mechanisms involving activation of VSM K+ channels and VSM hyperpolarization. For example, E2-induced relaxation of a spontaneously hypertensive rat aorta is inhibited by KV or KATP blockers (Unemoto et al., 2003). Also, E2 increases BKCa open probability in uterine artery myocytes and E2-induced uterine artery dilation is attenuated by the K+ channel blocker TEA (Rosenfeld et al., 2000). In porcine coronary myocytes, E2 more than doubled outward K+ currents and stimulated the gating of the BKCa channel (White et al., 1995). Also, in human coronary myocytes, E2 increased whole-cell K+ currents via BKCa, and these stimulatory effects were abolished by the ERα antisense plasmid (Han et al., 2006). With regard to selective ER agonists, in an endothelium-denuded rat aorta, PPT-induced vasorelaxation was blocked by TEA (Reslan et al., 2013), iberiotoxin, TRAM-34, and 4-AP, suggesting a role of BKCa, IKCa, and KV in ERα-mediated relaxation of rat aortic VSM (Alda et al., 2009). Also, G1 stimulated BKCa activity in intact porcine or human coronary VSM cells, and G1-induced relaxation of endothelium-denuded porcine coronary artery was attenuated by iberiotoxin (Yu et al., 2011). However, E2- and ER-mediated hyperpolarization and activation of VSM K+ channels appear to be unlikely mechanisms for ER-mediated decrease in [Ca2+]i in female mesenteric microvessels because the K+ gradient in high KCl and blockers of BKCa, KV, and the KATP channel did not prevent ER agonist-induced vasodilation and decreased [Ca2+]i.

Other potential mechanisms of ER-mediated decrease in VSM [Ca2+]i could involve the adenylate cyclase/cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) or guanylate cyclase/cGMP/protein kinase G (PKG) pathway, which could decrease VSM [Ca2+]i (Lincoln et al., 1990). E2 may stimulate cAMP/PKA or cGMP/PKG in the endothelium-denuded porcine coronary artery (White et al., 1995; Darkow et al., 1997; Teoh and Man, 2000; Keung et al., 2005) and rat mesenteric artery (Keung et al., 2011). Endothelial NO and VSM guanylate cyclase and adenylate cyclase/cAMP/PKA signaling could also mediate G1-induced relaxation of the mesenteric artery of a female Lewis rat (Lindsey et al., 2014) and porcine coronary artery (Yu et al., 2014). Also, ERα stimulation in the rat aortic VSM may evoke an endothelium-independent cGMP/PKG signaling pathway that could cause relaxation by opening BKCa and IKCa channels (Alda et al., 2009). In the present study, the guanylate cyclase inhibitor ODQ did not reverse ER agonist-induced relaxation or decreased [Ca2+]i, suggesting little role of guanylate cyclase/cGMP/PKG in mediating ER responses in mesenteric microvessels. These findings are consistent with the observations that the reported effect of ODQ or the cGMP inhibitor Rp-8-cGMP on E2-mediated relaxation appeared to be small in the porcine coronary and superior mesenteric artery (Keung et al., 2005, 2011) and negligible in the canine basilar and internal carotid artery (Ramirez-Rosas et al., 2014). The differences in sensitivity of ER-mediated responses to modulators of cGMP or cAMP could be related to different signaling mechanisms in different species and vascular beds and in large versus resistance microvessels.

An alternative mechanism is that ER-mediated decrease in [Ca2+]i likely involves direct effects on VSM Ca2+ channels. We found that in the presence of high KCl (51 mM) or the L-type Ca2+ channel agonist Bay K 8644, ER agonists caused microvascular relaxation and decreased [Ca2+]i, where E2 = PPT > DPN > G1, supporting that ER-mediated vasorelaxation effects involve inhibition of VSM Ca2+ entry via Ca2+ channels. This is consistent with reports that E2 caused relaxation in endothelium-denuded aortic rings contracted with Bay K 8644 or high KCl, and the E2 relaxant effects were not modified by BKCa, KV, and KATP blockers (Cairrao et al., 2012). Also, E2, PPT, DPN, and G1 caused relaxation in the endothelium-denuded carotid artery, aorta, and main renal, and mesenteric artery precontracted with high KCl (Reslan et al., 2013), and E2 decreased [Ca2+]i in the isolated porcine coronary artery and rat aortic VSM cells (Murphy and Khalil, 1999, 2000). Also, in rat aortic A7r5 cells, E2 inhibited the voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ current (Zhang et al., 1994) and basal and Bay K 8644–stimulated L-type Ca2+ current and had no effect on the basal K+ current (Cairrao et al., 2012). Thus, the mechanisms of E2-mediated decrease in VSM [Ca2+]i could vary depending on the blood vessel, vascular region, and animal species studied.

While Ca2+ is a major determinant of VSM contraction, additional mechanisms, such as Rho-kinase and PKC, may increase the myofilament force sensitivity to [Ca2+]i (Dallas and Khalil, 2003; Schubert et al., 2008). E2 inhibits Rho-kinase activity in the female rat basilar artery (Chrissobolis et al., 2004), Rho-kinase mRNA expression in coronary VSM cells (Hiroki et al., 2005), and contraction and RhoA activity in the rat aorta (Yang et al., 2009). Also, we have reported gender-related effects of E2 on PKC activity in the rat aortic VSM (Kanashiro and Khalil, 2001). The present study showed a similar relationship between decreased [Ca2+]i and relaxation in response to ER agonists, suggesting that the mesenteric microvessel relaxation is largely due to decreased VSM [Ca2+]i rather than changes in [Ca2+]i-sensitization pathways.

One limitation is that maximal effects of E2 were observed at micromolar concentrations, which are higher than the physiologic nanomolar plasma E2 levels. E2 is lipophilic, and its plasma levels may not reflect its vascular tissue level. Prolonged exposure to nanomolar E2 concentrations in vivo could lead to gradual tissue accumulation reaching levels similar to those used in the present acute studies. In this respect, ex vivo studies may require higher concentrations of ER agonists as they may bind to both the plasma membrane and specific ERs. High levels of E2 may also be needed to bind both physiologically active and other ER variants.

In conclusion, in mesenteric microvessels, ER subtypes mediate distinct vasodilation and decrease in [Ca2+]i largely due to endothelium-independent inhibition of Ca2+ entry into VSM. ER-mediated VSM relaxation does not appear to involve the K+ channels SKCa, IKCa, BKCa, KV, or KATP or the guanylate cyclase/cGMP pathway. Targeting ER subtypes and post-ER regulatory mechanisms of [Ca2+]i could represent novel approaches to maximize the vascular effects of E2 and the vascular benefits of MHT in CVD.

Perspective.

The present study showed ER-mediated vasodilation and decreased [Ca2+]i in microvessels of the female rat in estrus. Vascular function could be influenced by the stage of estrous and menstrual cycle and fluctuations in endogenous E2 levels (Dalle Lucca et al., 2000b; Lahm et al., 2007). For instance, Phe- and KCl-induced vasoconstriction is attenuated in the pulmonary artery from proestrus female rats having the highest endogenous E2 levels compared with estrus and diestrus females having lower E2 levels (Lahm et al., 2007). Also, in the uterine artery of diestrous day 1 female rats, ACh activates only EDHF-mediated relaxation, while in estrous, diestrous, day 2, and proestrous rats, ACh releases both EDHF and NO (Dalle Lucca et al., 2000b). The effects of variability in endogenous E2 levels on vascular function are important as spastic disorders, such as migraine headaches (MacGregor et al., 2006), Raynaud’s phenomenon (Greenstein et al., 1996), and angina (Rosano et al., 1995), may be influenced by the menstrual cycle. Also, the greater incidence, yet less severity, of pulmonary hypertension in females suggest a complex interaction of E2 and ERs in the pulmonary circulation (Christou and Khalil, 2010). Studying ER subtypes and post-ER relaxation mechanisms at different stages of the estrous and menstrual cycles could help elucidate the pathogenesis of female vasospastic disorders. Also, E2 metabolites and ER agonists may be beneficial in pulmonary hypertension (Tofovic et al., 2010) and occlusive artery diseases.

ER distribution and ER-mediated responses may also change with age and in E2 deficiency states associated with surgical menopause. We have shown that ER-mediated relaxation is reduced in the aorta of an aging female rat (Wynne et al., 2004) and that aortic contraction is enhanced in ovariectomized versus intact female rats (Murphy and Khalil, 2000; Kanashiro and Khalil, 2001). Studying ER activity in blood vessels of young versus old and intact versus ovariectomized females could provide further information on the potential usefulness of ER agonists in the treatment of age- and menopause-related vascular disease. The direct actions of E2 on VSM could be particularly important in aging women because of the increasingly dysfunctional endothelium with age (Wynne et al., 2004; Smiley and Khalil, 2009). Targeting specific ERs and post-ER signaling pathways in VSM may counter age-related endothelial cell damage and loss of endothelial ERs in postmenopausal women. Also, by virtue of their VSM [Ca2+]i lowering effect, ER agonists may provide a more natural treatment modality to reduce blood pressure in Ca2+ antagonist-sensitive forms of hypertension. Specific ER agonists could also target the VSM Ca2+-dependent contraction mechanisms without causing other adverse effects associated with the use of E2, such as breast or uterine cancer, inflammation, or changes in the plasma lipid profile. In the present study, we investigated the direct nongenomic effects of ER agonists and ER subtypes on microvessels from a normal female rat. Future studies should investigate the long-term genomic effects of ER agonists and assess the effects of administering different doses of ER agonists in vivo on the hemodynamics, heart rate, blood pressure, and vascular tone. Future studies should also evaluate the potential protective effects of ER agonists in preclinical animal models of vascular disease, such as hypertension.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Matthew Finn and Chris Angle for assistance with the data analysis.

Abbreviations

- 4-AP

4-aminopyridine

- ACh

acetylcholine

- Bay K 8644

1,4-dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-5-nitro-4-[2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-3-pyridinecarboxylic acid methyl ester

- BKCa

large conductance Ca2+- and voltage-activated K+ channel

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular free Ca2+ concentration

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DPN

diarylpropionitrile

- E2

17β-estradiol

- EDHF

endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ER

estrogen receptor

- G1

(±)-1-[(3aR*,4S*,9bS*)-4-(6-bromo-1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-3a,4,5,9b-tetrahydro:3H-cyclopenta(c)quinolin-8-yl]-ethanon

- G15

(3aS*,4R*,9bR*)-4-(6-bromo-1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-3a,4,5,9b-3H-cyclopenta(c)quinoline

- IKCa

intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel

- INDO

indomethacin

- KATP

ATP-sensitive K+ channel

- KV

voltage-dependent K+ channel

- L-NAME

Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester

- MHT

menopausal hormone therapy

- MPP

1,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-methyl-5-[4-(2-piperidinylethoxy)phenol]-1H-pyrazole

- NO

nitric oxide

- OCT

optimum cutting temperature

- ODQ

1H-(1,2,4)oxadiazolo(4,3-a)quinoxalin-1-one

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PGI2

prostacyclin

- Phe

phenylephrine

- PHTPP

4-[2-phenyl-5,7-bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl]phenol

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKG

protein kinase G

- PPT

4,4′,4′′-[4-propyl-(1H)-pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl]-tris-phenol

- SKCa

small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel

- TRAM-34

1-[(2-chlorophenyl)diphenylmethyl]-1H-pyrazole

- VSM

vascular smooth muscle

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Mazzuca, Khalil.

Conducted experiments: Mazzuca, Mata, Li.

Performed data analysis: Mazzuca, Mata, Rangan.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Mazzuca, Khalil.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grants HL65998, HL98724, and HL111775]; and the National Institutes of Health Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [Grant HD60702]. M.Q.M. is a recipient of American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (Founders Affiliate). K.M.M. is a recipient of a fellowship from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), São Paulo Research Foundation, São Paulo, Brazil. W.L. is a recipient of scholarship from the China Scholarship Council.

References

- Alda JO, Valero MS, Pereboom D, Gros P, Garay RP. (2009) Endothelium-independent vasorelaxation by the selective alpha estrogen receptor agonist propyl pyrazole triol in rat aortic smooth muscle. J Pharm Pharmacol 61:641–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano M, Aoki K, Matsuda T. (1986) Contractile effects of Bay K 8644, a dihydropyridine calcium agonist, on isolated femoral arteries from spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 239:198–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. (2008) Smooth muscle cell calcium activation mechanisms. J Physiol 586:5047–5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bologa CG, Revankar CM, Young SM, Edwards BS, Arterburn JB, Kiselyov AS, Parker MA, Tkachenko SE, Savchuck NP, Sklar LA, et al. (2006) Virtual and biomolecular screening converge on a selective agonist for GPR30. Nat Chem Biol 2:207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton BR, Miller AA, Sobey CG. (2010) Endothelium-dependent relaxation by G protein-coupled receptor 30 agonists in rat carotid arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298:H1055–H1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse R, Edwards G, Félétou M, Fleming I, Vanhoutte PM, Weston AH. (2002) EDHF: bringing the concepts together. Trends Pharmacol Sci 23:374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairrão E, Alvarez E, Carvas JM, Santos-Silva AJ, Verde I. (2012) Non-genomic vasorelaxant effects of 17β-estradiol and progesterone in rat aorta are mediated by L-type Ca2+ current inhibition. Acta Pharmacol Sin 33:615–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo C, Ceballos G, Rodríguez D, Villanueva C, Medina R, López J, Méndez E, Castillo EF. (2006) Effects of estradiol on phenylephrine contractility associated with intracellular calcium release in rat aorta. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291:C1388–C1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti S, Morton JS, Davidge ST. (2014) Mechanisms of estrogen effects on the endothelium: an overview. Can J Cardiol 30:705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Khalil RA. (2008) Differential [Ca2+]i signaling of vasoconstriction in mesenteric microvessels of normal and reduced uterine perfusion pregnant rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295:R1962–R1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrissobolis S, Budzyn K, Marley PD, Sobey CG. (2004) Evidence that estrogen suppresses rho-kinase function in the cerebral circulation in vivo. Stroke 35:2200–2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen KL, Mulvany MJ. (1993) Mesenteric arcade arteries contribute substantially to vascular resistance in conscious rats. J Vasc Res 30:73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christou HA, Khalil RA. (2010) Sex hormones and vascular protection in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 56:471–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane GJ, Gallagher N, Dora KA, Garland CJ. (2003) Small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated K+ channels provide different facets of endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization in rat mesenteric artery. J Physiol 553:183–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews JK, Khalil RA. (1999) Antagonistic effects of 17 beta-estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone on Ca2+ entry mechanisms of coronary vasoconstriction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 19:1034–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo G, Osol G. (1993) Regional variation in resistance artery diameter responses to alpha-adrenergic stimulation during pregnancy. Am J Physiol 264:H78–H85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas A, Khalil RA. (2003) Ca2+ antagonist-insensitive coronary smooth muscle contraction involves activation of epsilon-protein kinase C-dependent pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 285:C1454–C1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalle Lucca JJ, Adeagbo AS, Alsip NL. (2000a) Influence of oestrous cycle and pregnancy on the reactivity of the rat mesenteric vascular bed. Hum Reprod 15:961–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalle Lucca JJ, Adeagbo AS, Alsip NL. (2000b) Oestrous cycle and pregnancy alter the reactivity of the rat uterine vasculature. Hum Reprod 15:2496–2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkow DJ, Lu L, White RE. (1997) Estrogen relaxation of coronary artery smooth muscle is mediated by nitric oxide and cGMP. Am J Physiol 272:H2765–H2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey RK, Imthurn B, Zacharia LC, Jackson EK. (2004) Hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease: what went wrong and where do we go from here? Hypertension 44:789–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Félétou M, Vanhoutte PM. (2009) EDHF: an update. Clin Sci (Lond) 117:139–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Bland KI, Frackelton AR., Jr (2000) Estrogen-induced activation of Erk-1 and Erk-2 requires the G protein-coupled receptor homolog, GPR30, and occurs via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor through release of HB-EGF. Mol Endocrinol 14:1649–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freay AD, Curtis SW, Korach KS, Rubanyi GM. (1997) Mechanism of vascular smooth muscle relaxation by estrogen in depolarized rat and mouse aorta. Role of nuclear estrogen receptor and Ca2+ uptake. Circ Res 81:242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatta S, Nimmagadda D, Xu X, O’Rourke ST. (2006) Large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels: structural and functional implications. Pharmacol Ther 110:103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein D, Jeffcote N, Ilsley D, Kester RC. (1996) The menstrual cycle and Raynaud’s phenomenon. Angiology 47:427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney EP, Nachtigall MJ, Nachtigall LE, Naftolin F. (2014) The Women’s Health Initiative trial and related studies: 10 years later: a clinician’s view. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 142:4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas E, Bhattacharya I, Brailoiu E, Damjanović M, Brailoiu GC, Gao X, Mueller-Guerre L, Marjon NA, Gut A, Minotti R, et al. (2009) Regulatory role of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor for vascular function and obesity. Circ Res 104:288–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han G, Yu X, Lu L, Li S, Ma H, Zhu S, Cui X, White RE. (2006) Estrogen receptor alpha mediates acute potassium channel stimulation in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 316:1025–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington WR, Sheng S, Barnett DH, Petz LN, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. (2003) Activities of estrogen receptor alpha- and beta-selective ligands at diverse estrogen responsive gene sites mediating transactivation or transrepression. Mol Cell Endocrinol 206:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrington DM, Braden GA, Williams JK, Morgan TM. (1994) Endothelial-dependent coronary vasomotor responsiveness in postmenopausal women with and without estrogen replacement therapy. Am J Cardiol 73:951–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroki J, Shimokawa H, Mukai Y, Ichiki T, Takeshita A. (2005) Divergent effects of estrogen and nicotine on Rho-kinase expression in human coronary vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 326:154–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard BV, Rossouw JE. (2013) Estrogens and cardiovascular disease risk revisited: the Women’s Health Initiative. Curr Opin Lipidol 24:493–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanashiro CA, Khalil RA. (2001) Gender-related distinctions in protein kinase C activity in rat vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 280:C34–C45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanmura Y, Itoh T, Kuriyama H. (1984) Agonist actions of Bay K 8644, a dihydropyridine derivative, on the voltage-dependent calcium influx in smooth muscle cells of the rabbit mesenteric artery. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 231:717–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keung W, Chan ML, Ho EY, Vanhoutte PM, Man RY. (2011) Non-genomic activation of adenylyl cyclase and protein kinase G by 17β-estradiol in vascular smooth muscle of the rat superior mesenteric artery. Pharmacol Res 64:509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keung W, Vanhoutte PM, Man RY. (2005) Acute impairment of contractile responses by 17beta-estradiol is cAMP and protein kinase G dependent in vascular smooth muscle cells of the porcine coronary arteries. Br J Pharmacol 144:71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil RA. (2013) Estrogen, vascular estrogen receptor and hormone therapy in postmenopausal vascular disease. Biochem Pharmacol 86:1627–1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil RA, van Breemen C. (1990) Intracellular free calcium concentration/force relationship in rabbit inferior vena cava activated by norepinephrine and high K+. Pflugers Arch 416:727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleuser B, Malek D, Gust R, Pertz HH, Potteck H. (2008) 17-Beta-estradiol inhibits transforming growth factor-beta signaling and function in breast cancer cells via activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase through the G protein-coupled receptor 30. Mol Pharmacol 74:1533–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahm T, Patel KM, Crisostomo PR, Markel TA, Wang M, Herring C, Meldrum DR. (2007) Endogenous estrogen attenuates pulmonary artery vasoreactivity and acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: the effects of sex and menstrual cycle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293:E865–E871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln TM, Cornwell TL, Taylor AE. (1990) cGMP-dependent protein kinase mediates the reduction of Ca2+ by cAMP in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol 258:C399–C407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey SH, Carver KA, Prossnitz ER, Chappell MC. (2011) Vasodilation in response to the GPR30 agonist G-1 is not different from estradiol in the mRen2.Lewis female rat. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 57:598–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey SH, da Silva AS, Silva MS, Chappell MC. (2013) Reduced vasorelaxation to estradiol and G-1 in aged female and adult male rats is associated with GPR30 downregulation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 305:E113–E118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey SH, Liu L, Chappell MC. (2014) Vasodilation by GPER in mesenteric arteries involves both endothelial nitric oxide and smooth muscle cAMP signaling. Steroids 81:99–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Qiao X, Falone AE, Reslan OM, Sheppard SJ, Khalil RA. (2010) Gender-specific reduction in contraction is associated with increased estrogen receptor expression in single vascular smooth muscle cells of female rat. Cell Physiol Biochem 26:457–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor EA, Frith A, Ellis J, Aspinall L, Hackshaw A. (2006) Incidence of migraine relative to menstrual cycle phases of rising and falling estrogen. Neurology 67:2154–2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzuca MQ, Dang Y, Khalil RA. (2013) Enhanced endothelin receptor type B-mediated vasodilation and underlying [Ca²+]i in mesenteric microvessels of pregnant rats. Br J Pharmacol 169:1335–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzuca MQ, Li W, Reslan OM, Yu P, Mata KM, Khalil RA. (2014) Downregulation of microvascular endothelial type B endothelin receptor is a central vascular mechanism in hypertensive pregnancy. Hypertension 64:632–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzuca MQ, Wlodek ME, Dragomir NM, Parkington HC, Tare M. (2010) Uteroplacental insufficiency programs regional vascular dysfunction and alters arterial stiffness in female offspring. J Physiol 588:1997–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn ME. (2002) Genomic and nongenomic effects of estrogen in the vasculature. Am J Cardiol 90:3F–6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MR, Baretella O, Prossnitz ER, Barton M. (2010) Dilation of epicardial coronary arteries by the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor agonists G-1 and ICI 182,780. Pharmacology 86:58–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers MJ, Sun J, Carlson KE, Marriner GA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. (2001) Estrogen receptor-beta potency-selective ligands: structure-activity relationship studies of diarylpropionitriles and their acetylene and polar analogues. J Med Chem 44:4230–4251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T, Dietrich HH, Xiang C, Dacey RG., Jr (2013) G protein-coupled estrogen receptor agonist improves cerebral microvascular function after hypoxia/reoxygenation injury in male and female rats. Stroke 44:779–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Khalil RA. (1999) Decreased [Ca(2+)](i) during inhibition of coronary smooth muscle contraction by 17beta-estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 291:44–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Khalil RA. (2000) Gender-specific reduction in contractility and [Ca(2+)](i) in vascular smooth muscle cells of female rat. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 278:C834–C844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orshal JM, Khalil RA. (2004) Gender, sex hormones, and vascular tone. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286:R233–R249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare G, Krust A, Karas RH, Dupont S, Aronovitz M, Chambon P, Mendelsohn ME. (2002) Estrogen receptor-alpha mediates the protective effects of estrogen against vascular injury. Circ Res 90:1087–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffetto JD, Ross RL, Khalil RA. (2007) Matrix metalloproteinase 2-induced venous dilation via hyperpolarization and activation of K+ channels: relevance to varicose vein formation. J Vasc Surg 45:373–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Rosas MB, Cobos-Puc LE, Sánchez-López A, Gutiérrez-Lara EJ, Centurión D. (2014) Pharmacological characterization of the mechanisms involved in the vasorelaxation induced by progesterone and 17β-estradiol on isolated canine basilar and internal carotid arteries. Steroids 89:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reslan OM, Khalil RA. (2012) Vascular effects of estrogenic menopausal hormone therapy. Rev Recent Clin Trials 7:47–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reslan OM, Yin Z, do Nascimento GR, Khalil RA. (2013) Subtype-specific estrogen receptor-mediated vasodilator activity in the cephalic, thoracic, and abdominal vasculature of female rat. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 62:26–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revankar CM, Cimino DF, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER. (2005) A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science 307:1625–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosano GM, Collins P, Kaski JC, Lindsay DC, Sarrel PM, Poole-Wilson PA. (1995) Syndrome X in women is associated with oestrogen deficiency. Eur Heart J 16:610–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld CR, White RE, Roy T, Cox BE. (2000) Calcium-activated potassium channels and nitric oxide coregulate estrogen-induced vasodilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279:H319–H328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandow SL, Senadheera S, Bertrand PP, Murphy TV, Tare M. (2012) Myoendothelial contacts, gap junctions, and microdomains: anatomical links to function? Microcirculation 19:403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]