Abstract

Resistance to the human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER2)–targeted antibody trastuzumab is a major clinical concern in the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Increased expression or signaling from the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) has been reported to be associated with trastuzumab resistance. However, the specific molecular and biologic mechanisms through which IGF-1R promotes resistance or disease progression remain poorly defined. In this study, we found that the major biologic effect promoted by IGF-1R was invasion, which was mediated by both Src-focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling and Forkhead box protein M1 (FoxM1). Cotargeting IGF-1R and HER2 using either IGF-1R antibodies or IGF-1R short hairpin RNA in combination with trastuzumab resulted in significant but modest growth inhibition. Reduced invasion was the most significant biologic effect achieved by cotargeting IGF-1R and HER2 in trastuzumab-resistant cells. Constitutively active Src blocked the anti-invasive effect of IGF-1R/HER2 cotargeted therapy. Furthermore, knockdown of FoxM1 blocked IGF-1–mediated invasion, and dual targeting of IGF-1R and HER2 reduced expression of FoxM1. Re-expression of FoxM1 restored the invasive potential of IGF-1R knockdown cells treated with trastuzumab. Overall, our results strongly indicate that therapeutic combinations that cotarget IGF-1R and HER2 may reduce the invasive potential of cancer cells that are resistant to trastuzumab through mechanisms that depend in part on Src and FoxM1.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among women in the United States (Siegel et al., 2014). Multiple subtypes of breast cancer have been identified through gene profiling studies (Perou et al., 2000). Breast cancers that show amplification and overexpression of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (her2) gene represent approximately 20%–30% of metastatic cases (Slamon et al., 1987). Overexpression of the HER2 receptor tyrosine kinase is associated with poor prognosis, reduced overall survival, and the development of resistance to some types of chemotherapy (Slamon et al., 1987). The specific overexpression of HER2 in breast cancers serves as a selective target for anticancer drugs. Trastuzumab (Herceptin; Genentech, South San Francisco, CA), a humanized monoclonal antibody against an extracellular epitope on domain IV of HER2 (Carter et al., 1992), was the first HER2-targeted therapy approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer (Nahta, 2012). The mechanisms through which trastuzumab promotes antitumor activities include blockade of downstream signaling, reduced cleavage of the extracellular domain, inhibition of angiogenesis, and induction of immune activity, primarily antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) (Nahta et al., 2006). Trastuzumab plus chemotherapy improves overall response rates, time to progression, and the overall survival of patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer beyond that achieved with chemotherapy alone (Slamon et al., 2001). However, clinical trials demonstrate that the median duration of single-agent trastuzumab or trastuzumab-containing chemotherapeutic regimens is less than 1 year (Cobleigh et al., 1999; Seidman et al., 2001; Slamon et al., 2001; Esteva et al., 2002). Furthermore, single-agent trastuzumab achieves moderate response rates among HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancers (Cobleigh et al., 1999). These data indicate that acquired resistance and primary resistance to trastuzumab are clinical concerns in the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer.

Multiple mechanisms of trastuzumab resistance have been described in the literature. Constitutive activation of downstream phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signaling through phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) downregulation or PIK3CA hyperactivating mutations has been reported to significantly abrogate response to trastuzumab (Nagata et al., 2004; Berns et al., 2007). In addition, the lack of an effective ADCC immune response has been shown to result in trastuzumab resistance (Clynes et al., 2000; Arnould et al., 2006; Varchetta et al., 2007). Increased expression or compensatory signaling through other receptor tyrosine kinases, including insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R), epidermal growth factor receptor, or HER3, and/or crosstalk of receptor kinases to HER2 have also been reported as mechanisms of acquired resistance to trastuzumab (Lu et al., 2001; Nahta et al., 2005; Ritter et al., 2007; Junttila et al., 2009; Dua et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2010).

The first study to implicate IGF-1R in trastuzumab resistance showed that stable overexpression of IGF-1R reduces the ability of trastuzumab to induce G1 arrest and growth inhibition of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cell lines (Lu et al., 2001). Furthermore, among cases of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer, high IGF-1R expression or phosphorylation correlates with worse response to preoperative trastuzumab and chemotherapy (Harris et al., 2007) and reduced progression-free survival (Gallardo et al., 2012). We and others have reported that crosstalk from IGF-1R to HER2 results in sustained HER2 phosphorylation in the presence of trastuzumab (Nahta et al., 2005; Chakraborty et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2010). However, the specific mechanisms through which IGF-1R activates HER2 and the major downstream molecular and biologic effects remain poorly defined.

In this study, we found that Src activity maintained HER2 phosphorylation in trastuzumab-resistant cells. Furthermore, we showed that the major biologic effect promoted by IGF-1R was cellular invasion mediated by both Src-focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and HER2-Forkhead box protein M1 (FoxM1) signaling. Cotargeting IGF-1R and HER2 suppressed the invasiveness of trastuzumab-resistant cells and appeared to depend in part on FoxM1 and Src inhibition, because overexpression or activation of these molecules blocked the anti-invasive effect of IGF-1R/HER2 cotargeting. These results suggest that therapeutic combinations that block IGF-1R and HER2 may reduce the invasive potential of cancer cells that are resistant to trastuzumab.

Materials and Methods

Trastuzumab (Genentech) was obtained from the Emory Winship Cancer Institute pharmacy (Atlanta, GA) and dissolved in sterile water to a stock concentration of 20 mg/ml. Lapatinib ditosylate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) to a final concentration of 10 mM. The IGF-1R antibody α-IR3 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) was provided at a stock concentration of 1 mg/ml. The IGF-1R antibody IGF-IR-56-81 was developed by Dr. Pravin Kaumaya (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) (Foy et al., 2014). Briefly, rabbits were immunized with 1 mg of IGF-1R peptide, Ac-LLFRVAGLESLGDLFPNLTVIRGWKL-NH2; antibodies were purified from rabbit sera by affinity chromatography using protein A/G columns. IGF-1 ligand (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in sterile water at a stock concentration of 1 mg/ml. The IGF-1R kinase inhibitor NVPAEW541 (7-[cis-3-(1-azetidinylmethyl)cyclobutyl]-5-[3-(phenylmethoxy)phenyl]-7H-pyrrolo[2, 3-d]pyrimidin-4-amine, dihydrochloride; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) was dissolved in DMSO to a final concentration of 10 mM. In-solution Src kinase inhibitor PP2 [4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(dimethylethyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine; Calbiochem] was provided at a stock concentration of 10 mM in DMSO. FAK Inhibitor II [PF573228 (3,4-dihydro-6-[[4-[[[3-(methylsulfonyl)phenyl]methyl]amino]-5-(trifluoromethyl)-2-pyrimidinyl]amino]-2(1H)-quinolinone); Santa Cruz Biotechnology] was dissolved in DMSO to a stock concentration of 20 mM. The pLKO.1-IGF-1R-α/β short hairpin RNA (shRNA) plasmid and pLKO.1 empty vector plasmid (negative control) were purchased from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL). FoxM1 small interfering RNA (siRNA) (sc-270048) and control siRNA (sc-37007) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were resuspended in RNase-free water. FoxM1 expression plasmid was purchased from OriGene (Rockville, MD).

Cell Culture.

JIMT-1 cells were purchased from DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany); all other cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). HCC1954 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 with glutamine (Corning, Manassas, VA), and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. JIMT-1 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 4.5 g/l glucose, glutamine, and sodium pyruvate (Corning) with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. JIMT-1 and HCC1954 cells have previously been shown to have reduced response to trastuzumab compared with other models of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer and are considered models of primary trastuzumab resistance. All cells were cultured in humidified incubators at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Creation of Stable IGF-1R Knockdown Clones.

HEK-293T cells (1.5 × 106) were seeded in 100-mm dishes for 24 hours and cotransfected with 3 µg shRNA construct (pLKO.1-IGF-1R-α/β shRNA or pLKO.1 empty vector control plasmid), 3 µg pCMV-dR8.2, and 0.3 µg pCMV-VSV-G helper constructs using TransIT-LT-1 Transfection according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Mirus Bio LLC, Madison, WI). Viral stocks were harvested from culture media by centrifugation 48 hours after transfection and were syringe filtered. JIMT-1 cells were seeded at subconfluent densities and infected with lentiviral vectors (1:20 dilution) in fresh culture media. Culture media were replaced with media containing 5 µg/ml puromycin 48 hours after lentiviral infection to select for cells stably expressing the shRNAs. Stable knockdown was confirmed by Western blotting for IGF-1R. The IGF-1R shRNA and control shRNA cells are routinely maintained on 5 µg/ml puromycin in DMEM.

Stimulation Experiments.

Cells were plated and serum starved for 24 hours. During serum starvation, cells were either untreated or were treated with 500 nM PF573228 (FAK inhibitor), 100 nM lapatinib, varying concentrations of NVPAEW541, or vehicle control. Cells were then either lysed for protein or stimulated with vehicle control or 100 ng/ml IGF-1 for varying time points. Experiments were repeated at least three times with reproducible results.

Trypan Blue Exclusion.

For growth inhibition assays, cells were plated in complete DMEM at 2 × 104 cells per well in 12-well plates. The next day, media were aspirated and replaced with media containing control mouse IgG, α-IR3 (0.25 μg/ml), trastuzumab (20 μg/ml), or α-IR3 plus trastuzumab in triplicate. After 72 hours, viable cells were counted under a light microscope by trypan blue exclusion. Assays were repeated at least three times with reproducible results.

Anchorage-Independent Cell Culture Growth.

Cells were plated in matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at a 1:1 dilution (media/matrigel). The matrigel-cell suspension was allowed to solidify, and media containing control mouse IgG, α-IR3 (0.25 μg/ml), trastuzumab (20 μg/ml), or α-IR3 plus trastuzumab were added to cells in triplicate cultures. Media and drugs were renewed twice a week for 3 to 4 weeks. Photographs were taken with an Olympus IX50 inverted microscope at ×4 magnification (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Matrigel was digested using Dispase (BD Biosciences), and viable cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion. The average cell viability of triplicates and the S.D. were calculated. Experiments were performed at least twice with reproducible results.

Transfection.

Cells were plated in antibiotic-free media at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/ml. The next day, cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10 μg/ml of one of the following plasmids (kind gifts from Dr. Sumin Kang, Emory University, Atlanta, GA): constitutively active Src, kinase-dead Src, wild-type Src, or pcDNA3 empty vector control. Media were changed after 6 hours of transfection and replaced with complete media; cells were harvested after 48 hours.

Spheroid Migration Assays.

JIMT-1 (4.0 × 104) cells were untreated or were suspended in complete media containing one of the following treatments: control IgG, 0.25 µg/ml α-IR3, 20 µg/ml trastuzumab, or α-IR3 plus trastuzumab. Cells were seeded on 1% agar-coated 96-well plates and cultured for 24 hours in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. Intact tumor spheroids were carefully transferred to a 96-well plate and cultured in complete media containing respective inhibitors or control vehicle for 48 hours. Spheroids and migrated cells were fixed with 100% methanol, stained with 0.05% crystal violet, and observed using a normal light microscope (×20) and an Olympus DP-30BW digital camera. Experiments were repeated three times with reproducible results; representative images are shown for all groups.

Invasion Chamber Assays.

Cells were plated in serum-free media in BD BioCoat Matrigel Invasion Chambers (BD Biosciences) (1 × 105 cells/ml) with 0.75 ml of chemoattractant (culture media containing 10% FBS) in the wells. Depending on the experiment, cells were pretreated with 500 nM FAK inhibitor or 10 μM PP2 for 24 hours or were transfected with control siRNA, FoxM1 siRNA, empty vector, or FoxM1 expression plasmid overnight prior to placing cells in invasion chambers, at which point they were treated with control or IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) for 24 hours. In other experiments, control mouse IgG, α-IR3 (0.25 μg/ml), IGF-1R-56-81 (400 μg/ml), trastuzumab (20 μg/ml), α-IR3 plus trastuzumab, IGF-1R-56-81 plus trastuzumab, or IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) was added. Treatments were added directly to chambers in all experiments. Noninvading cells were removed from the interior surface of the membrane by scrubbing gently with a dry cotton-tipped swab. Each insert was then transferred into 100% methanol for 10 minutes followed by crystal violet staining for 20 minutes. Membranes were washed in water and allowed to air dry completely before being separated from the chamber. Membranes were mounted on slides with Permount permanent mounting medium (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Multiple photographs of each sample were taken at ×20 magnification, with triplicates performed per treatment group. The number of cells was counted in each field; the sum total of the fields was calculated for each sample. Experiments were performed at least twice with reproducible results.

Cell Cycle Analysis.

Cells were treated with control mouse IgG, α-IR3 (0.25 µg/ml), trastuzumab (20 µg/ml), or α-IR3 plus trastuzumab for 48 hours. Cells were harvested, washed twice with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) plus 10% FBS, fixed in ice-cold 80% ethanol, and stored at −20°C for at least 24 hours. Fixed cells were incubated in 50 μl of propidium iodide (PI) buffer [20 μg/ml PI (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.1% Triton-X 100, and 200 μg/ml RNaseA (Promega) in DPBS] for 30 minutes in the dark. The cells were then resuspended in 400 μl DPBS for flow cytometric analysis. Samples were analyzed using a BD FACS Canto II cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and BD FACS Diva software; experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated twice with reproducible results.

Western Blot Analyses.

Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Total protein extracts were run on SDS-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose. Blots were probed overnight. The following antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology: rabbit anti-phospho-IGF-1Rβ (Tyr1135/1136; no. 3024, 1:200), rabbit anti-phospho-IGF-1Rβ (Tyr1131; no. 3021, 1:200), rabbit anti-IGF-1Rβ (no. 3018, 1:250), rabbit anti-phospho-FAK (Tyr397; no. 8556, 1:250), rabbit anti-FAK (no. 3285), rabbit anti-phospho-p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK; extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 [Erk1/2]) (Thr202/Tyr204; no. 9101, 1:1000), rabbit anti-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2; no. 9102, 1:1000), rabbit anti-phospho-Src (Tyr416; no. 2101, 1:1000), rabbit anti-Src (no. 2123, 1:1000), and rabbit anti-FoxM1 (no. 5436, 1:200). The following antibodies were purchased from AbCam (Cambridge, MA): rabbit anti-phospho-erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 2 (erbB2)ErbB2 (Y877; no. ab47262, 1:200), rabbit anti-phospho-ErbB2 (Y877; no. ab108371, 1:200), and mouse anti-ErbB2 (no. ab16901, 1:200). Mouse anti-β-actin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (AC-15, 1:15,000). All primary antibodies were diluted in 5% bovine serum albumin/Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20. Goat anti-mouse secondary IRDye 800 antibody (no. 926-32210, 1:10,000) was purchased from Li-Cor Biosciences (Lincoln, NE). Goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 680 secondary antibody (no. 1027681, 1:10,000) was purchased from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). Protein bands were detected using the Odyssey Imaging System (Li-Cor Biosciences). All blots were repeated at least three times with reproducible results.

ADCC Assays.

The ADCC assay was performed as previously described (Kaumaya et al., 2009) using effector peripheral blood mononucleated cells, which were obtained from normal human donors and isolated by density-gradient centrifugation in Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The cells were washed twice in RPMI 1640 with 5% fetal calf serum and then serially diluted in 96-well plates to give effector/target ratios of 100:1, 20:1, and 4:1. The following day, 1 × 106 target cells (JIMT-1) were treated with trastuzumab, IGF-1R antibody, combination, normal rabbit IgG (control for IGF-1R antibody), normal human IgG (control for trastuzumab), or a combination of control IgGs. Cells were incubated for 2–4 hours at 37°C, after which cell death was measured with a nonradioactive assay using the aCella-TOX reagent kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical Analyses.

P values were determined for experimental versus control treatments by two-tailed t tests.

Results

IGF-1 Stimulates Crosstalk from IGF-1R to HER2.

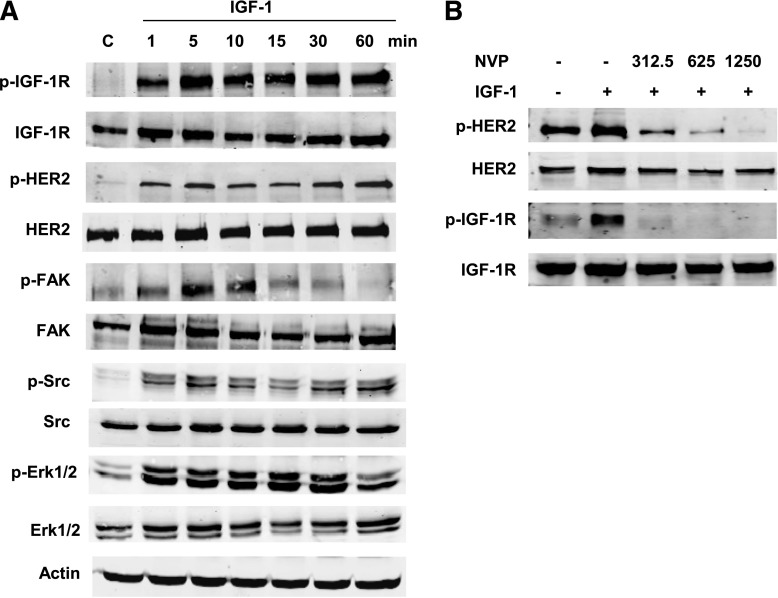

The JIMT-1 cell line represents a model of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer that exhibits intrinsic resistance to trastuzumab (Tanner et al., 2004). Cells were serum starved overnight and stimulated with IGF-1 at intervals ranging from 0 to 60 minutes. IGF-1 not only induced phosphorylation of IGF-1R but also promoted phosphorylation of HER2 (Fig. 1A). Phosphorylation of Src, FAK, and ERK1/2 was also induced by IGF-1 stimulation. Pretreatment of JIMT-1 cells with the IGF-1R tyrosine kinase inhibitor NVPAEW541 abrogated IGF-1–mediated phosphorylation of HER2 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that IGF-1 stimulates phosphorylation of HER2 through IGF-1R kinase activation.

Fig. 1.

IGF-1 stimulates IGF-1R crosstalk to HER2. (A) JIMT-1 cells were serum starved overnight and then treated with IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) for 1, 5, 10, 15, 30, or 60 minutes. Western blots of total protein lysates were performed for p-Tyr1135/1136 IGF-1R, total IGF-1R, p-Tyr877 HER2, total HER2, p-Tyr397 FAK, total FAK, p-Tyr416 Src, total Src, p-Thr202/Tyr204 p42/p44 Erk1/2, total Erk1/2, or actin. Lysates from the serum-starved control are included on the blot. Blots were repeated more than three times, and representative blots are shown. (B) JIMT-1 cells were serum starved overnight; cells were pretreated with the IGF-1R tyrosine kinase inhibitor NVPAEW541 where indicated (312.5, 625.0, or 1250.0 nM). After 24 hours, cells were stimulated with IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) for 5 minutes or left unstimulated; NVPAEW541 remained present in media where indicated. Western blots of total protein lysates were performed for p-Tyr1135/1136 IGF-1R, total IGF-1R, p-Tyr877 HER2, or total HER2; blots were repeated three times, and representative blots are shown. C, control; NVP, NVPAEW541.

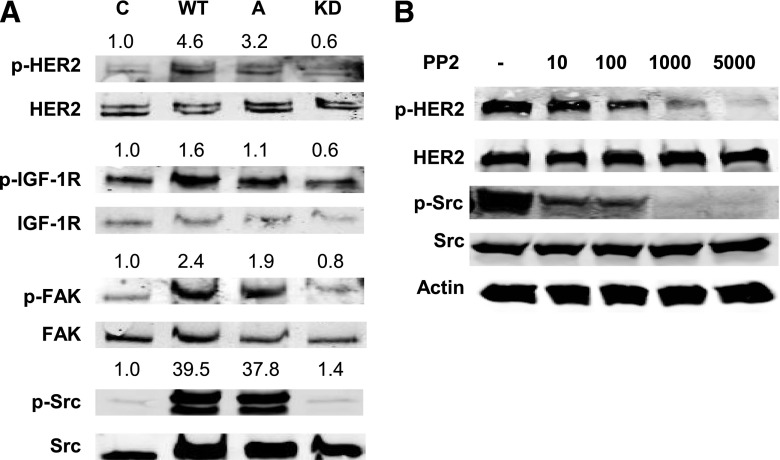

Src Kinase Regulates Phosphorylation of HER2 in Resistant Cells.

Increased Src kinase activity has been linked to trastuzumab resistance; furthermore, Src induces phosphorylation of receptor tyrosine kinases, including epidermal growth factor receptor and HER2 (Zhang et al., 2011). We found that Src phosphorylation was increased in response to IGF-1 stimulation in trastuzumab-resistant cells (Fig. 1). Transfection of wild-type or constitutively active Src constructs resulted in increased levels of phosphorylated HER2 and FAK in JIMT-1 cells, in contrast to transfection of kinase-dead Src (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of Src with the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 showed a dose-dependent decrease in HER2 phosphorylation (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that Src activity regulates HER2 phosphorylation in trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer cells.

Fig. 2.

Src kinase mediates HER2 phosphorylation in trastuzumab-resistant cells. (A) JIMT-1 cells were transfected with empty vector pcDNA3.1 (control), or constructs expressing wild-type Src, constitutively active Src, or kinase-dead Src. Western blots of total protein lysates were performed for p-Tyr1131 IGF-1R, total IGF-1R, p-Tyr877 HER2, total HER2, p-Tyr397 FAK, total FAK, p-Tyr416 Src, and total Src. Individual bands representing phosphorylated proteins were quantified and normalized to the band in the control lane. Quantification was performed directly on the Odyssey imaging machine with LI-COR software, and background was subtracted. (B) JIMT-1 cells were treated with DMSO (−) or the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 at doses ranging from 10 nM to 5000 nM for 24 hours. Western blots of total protein lysates were performed for p-Tyr877 HER2, total HER2, p-Tyr416 Src, total Src, or actin; blots were repeated at least twice, and representative sets of blots are shown. A, constitutively active; C, control; KD, kinase-dead; WT, wild type.

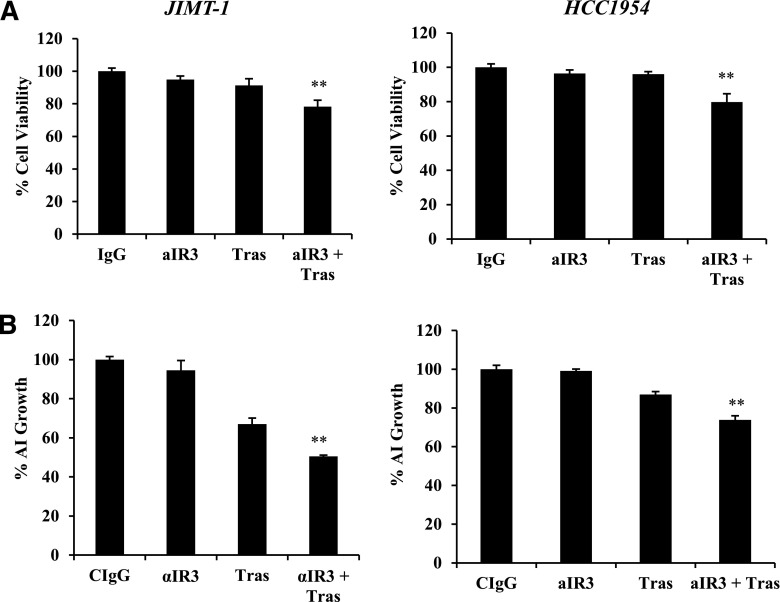

Effects of Pharmacological Inhibition of IGF-1R Plus Trastuzumab on Cell Growth.

Next, we examined the effects of cotargeting IGF-1R and HER2 in trastuzumab-resistant cells. Fluorescent-activated cell sorting analysis of PI-stained cells indicated that combination treatment with the IGF-1R–targeted antibody α-IR3 plus trastuzumab did not have major effects on the cell cycle distribution of JIMT-1 cells after 48 hours (Supplemental Fig. 1). Trypan blue exclusion demonstrated modest, statistically significant reductions in the growth of trastuzumab-resistant JIMT-1 and HCC1954 cells in response to the combination of α-IR3 and trastuzumab when administered for a slightly longer treatment time period than that used in the fluorescent-activated cell sorting assays (Fig. 3A). Approximately 20% fewer cells were present in the treatment groups after 72 hours. Longer-term (2 to 3 weeks), matrigel-based cultures of JIMT-1 cells showed higher levels of growth inhibition in response to the combination treatment, with approximately 50% growth inhibition (Fig. 3B). As a single agent, trastuzumab reduced anchorage-independent growth of JIMT-1 cells by approximately 30% compared with a complete lack of growth inhibition by trastuzumab in anchorage-dependent cultures. This is likely due to prolonged exposure of matrigel cultures to treatment. These results suggest that JIMT-1 cells retain a low level of trastuzumab sensitivity, although they are relatively resistant compared with accepted models of sensitivity, such as BT474 and SKBR3 cells (not shown). In contrast with JIMT-1, long-term, matrigel-based cultures of HCC1954 cells showed a similar level of growth inhibition as that observed in trypan blue exclusion assays, with approximately 20% fewer cells in the combination group compared with controls, and no inhibition by single agents. Overall, these results indicate that the combination of α-IR3 and trastuzumab modestly reduces the growth of intrinsically resistant HER2-positive breast cancer cells to a greater extent than achieved with single-agent α-IR3 or trastuzumab.

Fig. 3.

Cotargeting IGF-1R and HER2 inhibits growth. (A) JIMT-1 or HCC1954 cells were treated with control IgG, IGF-1R monoclonal antibody α-IR3 (0.25 µg/ml), trastuzumab (20 µg/ml), or the combination of α-IR3 and trastuzumab. After 72 hours, cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion. Data are reported as a percentage of the control IgG group; results represent the average of triplicate cultures per group. The experiment was performed three times with reproducible results; S.D.s between replicates are shown (t test, **P ≤ 0.005). (B) JIMT-1 or HCC1954 cells were plated in matrigel and maintained in media containing control IgG, IGF-1R monoclonal antibody α-IR3 (0.25 µg/ml), trastuzumab (20 µg/ml), or the combination of α-IR3 and trastuzumab. Media were changed twice a week for 2 to 3 weeks. Matrigel was dissolved with Dispase, and cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion. Percent change in anchorage-independent cell survival is shown relative to the control IgG group (lower panels). The experiment was repeated three times with reproducible results (t test, **P ≤ 0.005); error bars represent the S.D. AI, anchorage independent; aIR3, α-IR3; CIgG, control IgG; Tras, trastuzumab.

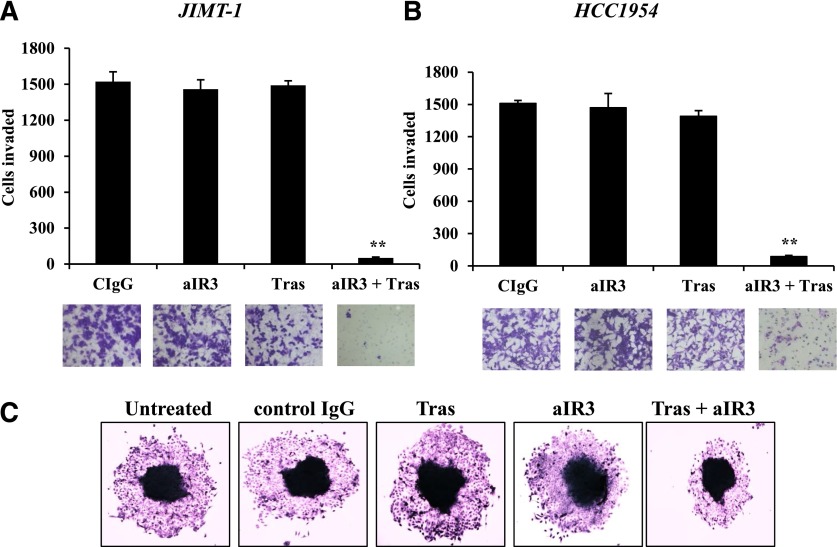

Pharmacological Inhibition of IGF-1R in Combination with Trastuzumab Suppresses Invasion of Resistant Cells.

In contrast with effects on cell growth, the combination of α-IR3 and trastuzumab showed dramatic effects on the invasive potential of JIMT-1 and HCC1954 cells. Although neither of the antibodies reduced invasion when administered as single agents, the combination of IGF-1R and HER2 antibodies almost completely suppressed the abilities of JIMT-1 (Fig. 4A) and HCC1954 (Fig. 4B) to invade across matrigel-coated Boyden chambers. In contrast, the combination of α-IR3 and trastuzumab did not reduce the invasiveness of IGF-1R–expressing MDA231 breast cancer cells (Supplemental Fig. 2), which lack overexpression of HER2. These results reduce the likelihood that off-target effects mediate the anti-invasive effect of this antibody combination and suggest that endogenous HER2 overexpression may be required to elicit this effect. Similar to the Boyden assays, the combination of α-IR3 and trastuzumab reduced the migration of JIMT-1 cells in spheroid assays (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that the suppression of invasion is a major effect of cotargeting IGF-1R and HER2 in trastuzumab-resistant cells.

Fig. 4.

Cotargeting IGF-1R and HER2 suppresses invasiveness of trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer cells. (A and B) JIMT-1 cells (A) and HCC1954 cells (B) were pretreated for 48 hours with control IgG, 0.25 µg/ml α-IR3, 20 µg/ml trastuzumab, or α-IR3 plus trastuzumab. Cells were then seeded into Boyden chambers in the presence of 10% FBS and respective drugs. After 24 hours of invasion, photos were taken, and the number of invaded cells was counted in 10 random fields and added together; results represent the average of triplicate cultures per group. Representative photos are shown. The experiment was performed twice with reproducible results (t test, **P ≤ 0.005); error bars represent the S.D. (C) Spheroid migration assay of untreated JIMT-1 cells untreated or JIMT-1 cells treated with control IgG, 0.25 µg/ml α-IR3, 20 µg/ml trastuzumab, or α-IR3 plus trastuzumab. Representative images of spheroids are shown. aIR3, α-IR3; CIgG, control IgG; Tras, trastuzumab. Original magnification, ×4 in C.

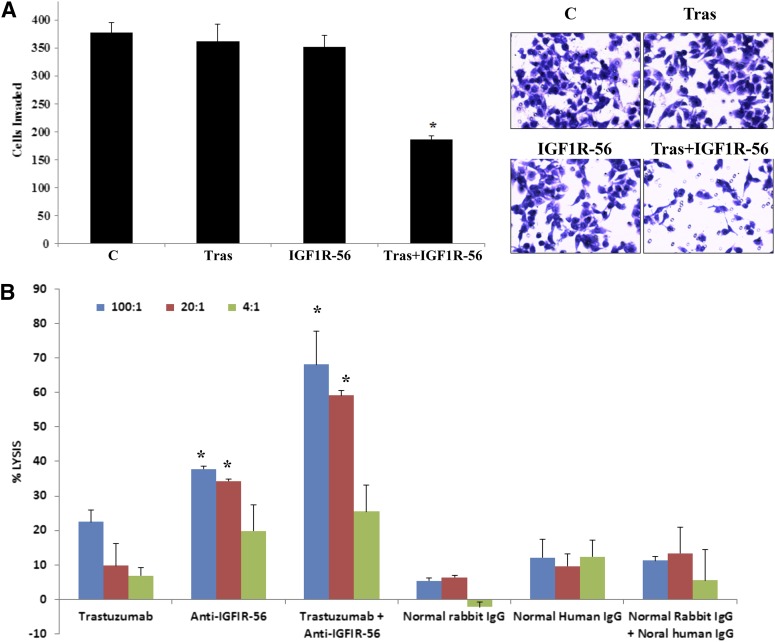

To gain additional evidence that cotargeting IGF-1R and HER2 suppresses invasion, we treated JIMT-1 cells with a different IGF-1R antibody, IGF-IR-56-81 (Foy et al., 2014); this antibody is directed against a different epitope of IGF-1R than α-IR3. Similar to α-IR3 plus trastuzumab, the combination of IGF-IR-56-81 plus trastuzumab significantly reduced JIMT-1 cell invasion, whereas neither antibody alone affected invasion (Fig. 5A). In addition, the combination of IGF-1R and HER2 antibodies induced significant ADCC of JIMT-1 cells compared with controls and compared with either of the single agents (Fig. 5B). These data provide further evidence that targeting IGF-1R improves response to trastuzumab. Furthermore, these data suggest that blockade of invasion and induction of ADCC are two major biologic effects of cotargeting IGF-1R and HER2 with selective antibodies.

Fig. 5.

IGF-1R peptide mimic-induced antibody plus trastuzumab suppresses invasion and induces ADCC of trastuzumab-resistant cells. (A) JIMT-1 cells were seeded in serum-free media in Boyden chambers in the presence of the following treatments: control, rabbit antibody generated against IGF-1R-56-81 peptide (400 μg/ml), 20 µg/ml trastuzumab, and 400 µg/ml IGF-IR antibody IGF-1R-56-81 plus trastuzumab. Media containing 10% FBS were used in the well as the chemoattractant. After 24 hours of invasion, photos were taken, and the number of invaded cells was counted in 12 random fields and added together; results represent the average of triplicate cultures per group. Representative photos are shown. The experiment was performed twice with reproducible results (t test, *P ≤ 0.05); error bars represent the S.D. (B) ADCC assays were performed using 100:1, 20:1, or 4:1 PBMC/JIMT-1 cell ratios. Treatment groups included 20 µg/ml trastuzumab, 400 µg/ml IGF-IR antibody IGF-1R-56-81, combination, normal rabbit IgG (control for IGF-1R antibody), normal human IgG (control for trastuzumab), or combination of control IgGs. Cells were incubated for 2–4 hours at 37°C, after which cell death was measured with a nonradioactive assay using the aCella-TOX reagent kit. The percentage of JIMT-1 cell lysis is shown; experiments were performed in triplicate (t test, *P ≤ 0.05 for combination versus trastuzumab alone, anti-IGF-1R-56-81 alone, or controls; *P ≤ 0.05 for anti-IGF-1R-56-81 versus control); error bars represent the S.D. C, control; IGF-1R-56, IGF-1R-56-81 peptide; PBMC, peripheral blood mononucleated cell; Tras, trastuzumab.

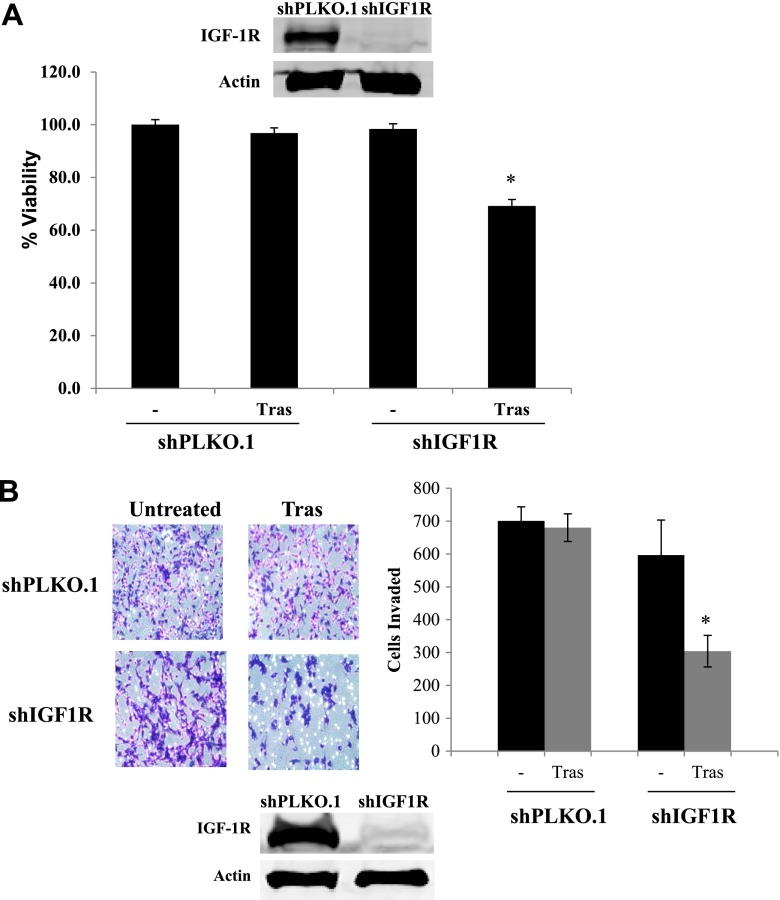

Combination Knockdown of IGF-1R Plus Trastuzumab Reduces Growth and Invasion.

In addition to pharmacological inhibition of IGF-1R, we examined effects of knocking down IGF-1R by stably infecting JIMT-1 cells with lentiviral shRNA against IGF-1R versus control shRNA. Knockdown of IGF-1R improved the sensitivity of cells to trastuzumab, as demonstrated by reduced cell counts in a trypan blue exclusion assay (Fig. 6A). Similar to pharmacological targeting with the IGF-1R antibodies, IGF-1R knockdown in combination with trastuzumab showed an even more significant reduction in cellular invasion (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

IGF-1R knockdown combined with trastuzumab treatment reduces growth and invasion. (A) JIMT-1 shPLKO.1 or shIGF-1R cells were treated with trastuzumab (20 μg/ml) or vehicle control. After 72 hours, cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion. Data are reported as a percentage of the control group. Results represent the average of triplicate cultures per group (t test, *P < 0.05); error bars represent the S.D. Western blots of total protein lysates were performed on the remaining cells for total IGF-1R to confirm knockdown; experiments were repeated at least three times. (B) JIMT-1 control shRNA stables (shPLKO.1) or IGF-1R shRNA stables (shIGF1R) were seeded and treated with control or 20 µg/ml trastuzumab in Boyden chambers in serum-free media. Media containing 10% FBS were placed in the well as the chemoattractant. After 24 hours of invasion, photos were taken, and the number of invaded cells was counted in 12 random fields and added together; results represent the average of triplicate cultures per group. Representative photos are shown. The experiment was performed at least twice with reproducible results (t test, *P < 0.05); error bars represent the S.D. Western blots of total protein lysates were performed on the remaining cells for total IGF-1R to confirm knockdown. Tras, trastuzumab.

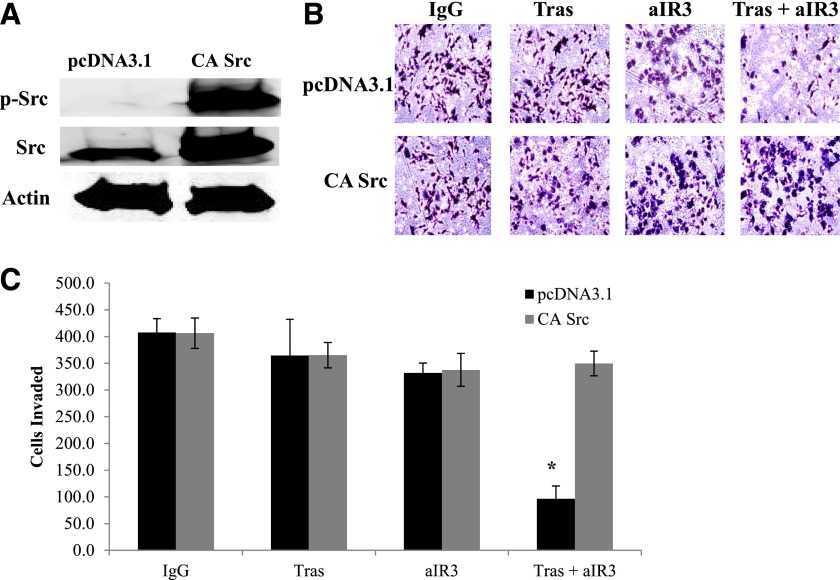

Src Activity Regulates IGF-1–Mediated Invasive Effects in Resistant Cells.

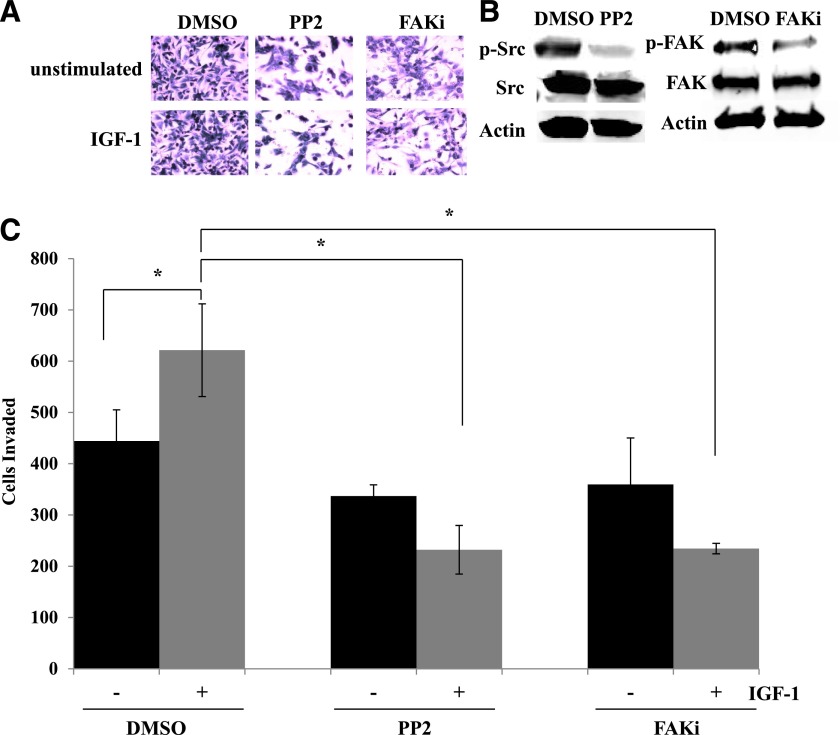

Based on our data suggesting that Src regulates HER2 phosphorylation in trastuzumab-resistant cells (Fig. 2), we examined the role of Src as a regulator of the invasive phenotype of resistant cells. Transfection of constitutively active Src into JIMT-1 cells completely abrogated the significant anti-invasive effect of α-IR3 plus trastuzumab cotreatment (Fig. 7). Furthermore, Src inhibition with the PP2 compound blocked IGF-1–mediated invasion in resistant cells, similar to FAK inhibition (Fig. 8). These results suggest that IGF-1–mediated invasion in trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer cells depends in part on Src-FAK signaling. Furthermore, these data indicate that Src inhibition may be essential to achieve an anti-invasive effect with a combination approach that cotargets IGF-1R and HER2.

Fig. 7.

Constitutively active Src blocks the anti-invasive effect of IGF-1R/HER2 cotargeting. JIMT-1 cells were transfected for 24 hours with empty vector pcDNA3.1 or constitutively active Src. (A) Western blots of total protein lysates were performed for p-Tyr416 Src, total Src, or actin. (B and C) Transfected cells were seeded in Boyden chambers in serum-free media with 10% FBS in the chamber as the chemoattractant plus indicated treatments with control IgG, 20 µg/ml trastuzumab, 0.25 µg/ml α-IR3, or α-IR3 plus trastuzumab. After another 24 hours, photos were taken; representative photos are shown in (B). (C) The number of invaded cells was counted in 10 random fields and added together; results represent the average of triplicate cultures per group. The experiment was performed twice with similar results (t test, *P ≤ 0.05); error bars represent the S.D. aIR3, α-IR3; CA, constitutively active; Tras, trastuzumab.

Fig. 8.

Inhibition of Src or FAK suppresses IGF-1–stimulated invasion of resistant cells. JIMT-1 cells were pretreated for 24 hours with DMSO, 10 µM PP2, or 500 nM FAK Inhibitor II (PF573228) in serum-free media. Cells were then seeded in Boyden chambers in serum-free media with 10% FBS in the chamber as the chemoattractant. Drug treatment was continued, and IGF-1 ligand was added to the chambers of treatment groups where indicated. (A) After 24 hours of invasion, photos were taken; representative photos are shown. (B) Western blots of total protein lysates were performed for p-Tyr416 Src, total Src, p-Tyr397 FAK, or total FAK to ensure inhibition of the target; representative blots are shown. (C) The number of invaded cells was counted in 12 random fields and added together; results represent the average of triplicate cultures per group. The experiment was performed twice with reproducible results (t test, *P ≤ 0.05); error bars represent the S.D. FAKi, FAK inhibitor.

FoxM1 Contributes to IGF-1–Stimulated Invasion of Trastuzumab-Resistant Cells.

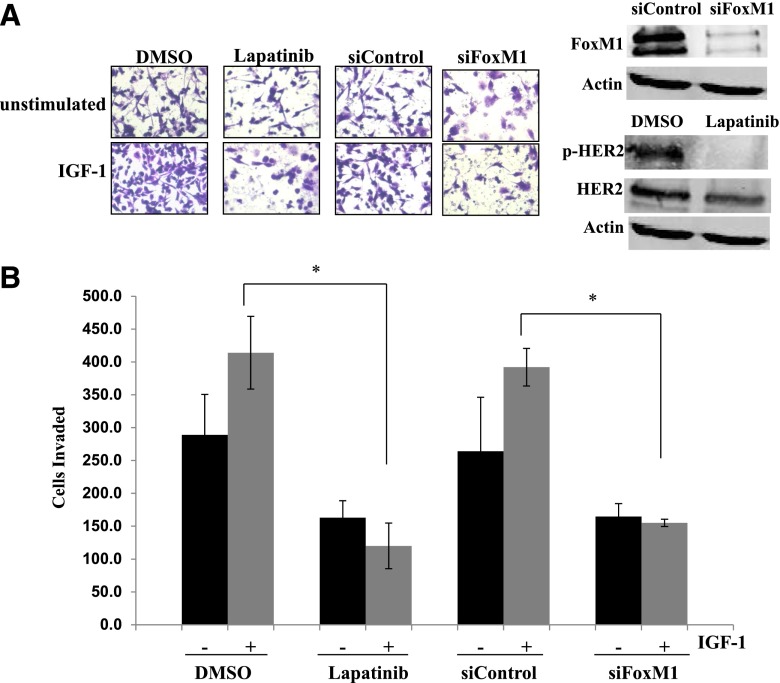

To determine whether HER2 signaling is required for IGF-1–stimulated phosphorylation of Src and FAK, we treated cells with the HER2 kinase inhibitor lapatinib. Lapatinib blocked HER2 phosphorylation in JIMT-1 cells but did not reduce IGF-1 signaling to Src or FAK (Supplemental Fig. 3), suggesting that crosstalk to HER2 may not be necessary for IGF-1–stimulated Src-FAK signaling. However, lapatinib blocked IGF-1–mediated invasion (Fig. 9), indicating that HER2 kinase activity was required for IGF-1–stimulated invasion in JIMT-1 cells.

Fig. 9.

HER2 kinase and FoxM1 contribute to IGF-1–stimulated invasion. (A) JIMT-1 cells were pretreated for 24 hours with DMSO or 100 nM lapatinib in serum-free media or were transfected with 100 nM control siRNA or FoxM1 siRNA. Cells were then seeded in Boyden chambers in serum-free media with 10% FBS in the well as the chemoattractant. Drug treatment was continued, and IGF-1 ligand was added to the chambers of treatment groups where indicated. Western blots of total protein lysates were performed for FoxM1, p-Tyr877 HER2, and total HER2 to ensure inhibition of the target; representative blots are shown. After 24 hours of invasion, photos were taken; representative photos are shown. (B) The number of invaded cells was counted in 12 random fields and added together; results represent the average of triplicate cultures per group. Black bars, no IGF-1 stimulation; gray bars, plus IGF-1 stimulation. The experiment was performed twice with reproducible results (t test, *P ≤ 0.05); error bars represent the S.D. siFoxM1, FoxM1 siRNA.

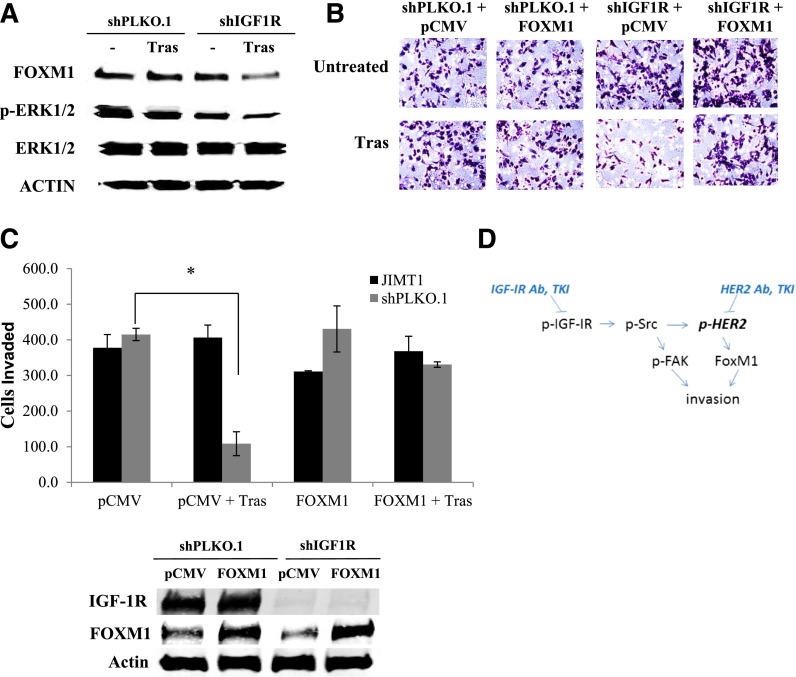

We previously showed that the transcription factor FoxM1 promotes resistance to lapatinib via mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) signaling in JIMT-1 cells, whereas knockdown of FoxM1 improves lapatinib sensitivity (Gayle et al., 2013). Because FoxM1 functions are known to promote cancer cell invasion, we examined the role of FoxM1 in IGF-1–mediated invasion of JIMT-1. Importantly, knockdown of FoxM1 blocked the ability of IGF-1 to promote cellular invasion (Fig. 9). Furthermore, stable IGF-1R knockdown plus trastuzumab treatment downregulated FoxM1 expression and reduced Erk1/2 phosphorylation, whereas IGF-1R knockdown alone did not (Fig. 10A). These results suggest that IGF-1R and HER2 may cooperatively regulate the expression of FoxM1 in JIMT-1 cells. Importantly, re-expression of FoxM1 restored invasion to stable IGF-1R knockdown cells treated with trastuzumab (Fig. 10, B and C). Thus, FoxM1 expression blocked the anti-invasive effect of combination IGF-1R knockdown plus trastuzumab. Together with the FoxM1 knockdown results (Fig. 9), these data suggest that FoxM1 expression affects the anti-invasive effect of IGF-1R/HER2 cotargeting, such that FoxM1 suppression may be necessary for this approach to be effective.

Fig. 10.

FoxM1 expression overcomes the anti-invasive effect of IGF-1R knockdown plus trastuzumab. (A) JIMT-1 shPLKO.1 or shIGF-1R cells were treated with trastuzumab (20 μg/ml) or vehicle control. After 72 hours, protein lysates were blotted for FoxM1, p42/p44 Erk1/2, total Erk1/2, or actin; blots were repeated at least three times, and representative sets of blots are shown. (B) JIMT-1 shPLKO.1 or shIGF-1R cells were transfected for 24 hours with 10 μg/ml of empty vector pCMV control plasmid or FoxM1-overexpressing plasmid. Cells were then seeded in Boyden chambers in serum-free media with 10% FBS in the well as the chemoattractant. Trastuzumab (20 μg/ml) was added to the chambers of treatment groups where indicated. Western blots of total protein lysates were performed for FoxM1 to ensure overexpression of the target; representative blots are shown. After 24 hours of invasion, photos were taken; representative photos are shown. (C) The number of invaded cells was counted in 12 random fields and added together; results represent the average of triplicate cultures per group. The experiment was performed twice with reproducible results (t test, *P ≤ 0.05); error bars represent the S.D. (D) Overall model: IGF-1 stimulates Src-mediated crosstalk from IGF-1R to HER2, resulting in the activation of FAK downstream of Src and FoxM1 downstream of HER2. Coinhibition of IGF-1R and HER2 is required to overcome the proinvasive effects of Src-FAK signaling and FoxM1 in trastuzumab-resistant cells. Ab, antibody; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; Tras, trastuzumab.

Discussion

Trastuzumab remains the primary first-line treatment administered for HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. Primary resistance and acquired resistance to trastuzumab occur in many patients; thus, a clear understanding of molecular mechanisms that drive resistance are required to improve therapeutic approaches for resistant tumors. We previously demonstrated that IGF-1R and HER2 form a unique receptor complex and demonstrate crosstalk in models of acquired resistance (Nahta et al., 2005). This finding was further corroborated by another study showing that IGF-1R and HER2 form a larger complex that includes HER3, with crosstalk occurring among all three receptors (Huang et al., 2010). Despite these findings, the mechanisms facilitating crosstalk and the downstream molecular and biologic effects mediated by IGF-1R in HER2-overexpressing breast cancers remain poorly defined.

In this study, we found that IGF-1 stimulated phosphorylation of HER2 in trastuzumab-resistant cells. Src phosphorylation was also activated by IGF-1 and appeared to be critical for maintaining HER2 phosphorylation, because a small-molecule Src kinase inhibitor achieved dose-dependent inhibition of HER2 phosphorylation in the HER2-overexpressing JIMT-1 cell line, which exhibits primary resistance to trastuzumab. Furthermore, wild-type and constitutively active Src induced phosphorylation of HER2 and FAK, indicating that Src regulates baseline phosphorylation of HER2 and FAK in resistant cells. In addition to regulating HER2 phosphorylation status, Src proved to be an important mediator of invasion in resistant cells. Src kinase inhibition blocked IGF-1–mediated invasion, and constitutively active Src overcame the anti-invasive effect of the trastuzumab/α-IR3 combination.

Src has previously been shown to have multiple important roles in the development of resistance. For example, although Src is inhibited by trastuzumab in sensitive cells (Nagata et al., 2004), resistant cells show increased activation of Src (Zhang et al., 2011). Inhibition of Src normally results in PTEN dephosphorylation with subsequent membrane relocalization and phosphatase activation of PTEN (Nagata et al., 2004); in contrast, Src activity in resistant cells blocks PTEN activity and increases phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling (Zhang et al., 2011). Src activation has been reported to occur downstream of multiple mechanisms of trastuzumab resistance, including increased signaling from growth factors and receptors, such as transforming growth factor-β (Wang et al., 2009), ephrin type-A receptor 2 (Zhuang et al., 2010), and growth differentiation factor-15 (Joshi et al., 2011). As a result, Src inhibition has been shown to improve trastuzumab response in multiple models (Zhang et al., 2011; Han et al., 2014; Peiró et al., 2014). Thus, our data that Src contributes to the regulation of HER2 phosphorylation and the invasive potential of resistant cells are consistent with previous reports supporting a central role for Src in trastuzumab resistance.

The contribution of Src to the invasive potential of resistant cells may be partially due to the activation of FAK, because Src kinase activation increased FAK phosphorylation, and small-molecule inhibitors of both Src and FAK reduced IGF-1–stimulated invasion. The role of FAK in the invasiveness of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer and trastuzumab resistance is supported by previous studies. Recruitment of FAK to HER2 has been reported to occur in response to heregulin stimulation (Vadlamudi et al., 2003); furthermore, phosphorylation levels of Src, FAK, and HER2 correlate in clinical breast cancer samples (Schmitz et al., 2005). Similar to our results with IGF-1 stimulation, transforming growth factor-β has been shown to induce FAK phosphorylation downstream of Src (Wang et al., 2009). In addition, a phase I investigation of the Src kinase inhibitor, saracatinib, in patients with advanced solid tumors, including 13 metastatic breast cancers, showed that FAK phosphorylation is a useful surrogate marker for Src activity (Baselga et al., 2010). FAK inhibitors, including a dual IGF-1R/FAK inhibitor, have been shown to induce apoptosis in models of HER2-overexpressing breast cancers. Our data suggest that these agents may have additional utility in the setting of IGF-1–driven trastuzumab resistance.

The recruitment and activation of intracellular kinases, such as FAK, by IGF-1R have been shown to occur through integrins in some cell systems (Desgrosellier and Cheresh, 2010). Thus, the possibility that IGF-1 promotes Src-FAK signaling and invasion through integrins in the context of trastuzumab resistance should be considered in future studies. For example, HER2 function and resistance to HER2-targeted therapies were previously associated with integrin-mediated adhesion to the extracellular protein laminin-5 in association with increased FAK signaling (Yang et al., 2010). Overexpression of β1 integrin has also been shown to mediate trastuzumab resistance (Lesniak et al., 2009). Furthermore, the erbB growth factor heregulin has been shown to regulate αvβ3 integrin levels in invasive breast cancers to affect downstream MAPK signaling (Vellon et al., 2005). The potential importance of integrins to resistance is further reflected by the finding that cancer cells that overexpress both HER2 and the integrin receptor α6β4 exhibit a highly aggressive and malignant phenotype (Falcioni et al., 1997). Thus, there is a clear body of literature supporting a link between integrins, HER2 signaling, and resistance. The role of IGF-1R in this context is supported by the finding that IGF-1 stimulation disrupts the αv integrin/E-cadherin/IGF-1R ternary complex, leading to integrin redistribution to focal contact sites and increased invasion (Canonici et al., 2008). Thus, future studies should examine the role that integrins play in IGF-1–mediated trastuzumab resistance and the effect of integrin signaling on the efficacy of IGF-1R/HER2 combination approaches, particularly as they relate to invasion. Another important mediator of invasion activated downstream of HER2 is the FoxM1 transcription factor; expression of FoxM1 correlates with poor prognosis and HER2 overexpression in breast cancer (Bektas et al., 2008; Francis et al., 2009; Carr et al., 2010). We previously reported that FoxM1 expression levels and cellular localization are heavily regulated by MEK signaling in trastuzumab-resistant cells, including JIMT1 cells (Gayle et al., 2013). Coinhibition of HER2 and MEK downregulated FoxM1 expression and blocked the growth of trastuzumab-resistant cancer cell xenografts (Gayle et al., 2013). In addition to our previous results showing that HER2-MEK signaling regulates FoxM1 expression, the results of this study indicate that FoxM1 expression is codependent on IGF-1R and HER2 in resistant cells. Stable knockdown of IGF-1R alone did not alter FoxM1 expression; however, IGF-1R knockdown plus trastuzumab reduced Erk1/2 phosphorylation, downregulated FoxM1 expression, and reduced the invasive potential of resistant cells. This is likely due to the codependence of these cells on IGF-1R and HER2, such that both receptors must be inhibited to achieve meaningful downstream signaling blockade. Re-expression of FoxM1 restored the invasive ability of resistant cells in the context of IGF-1R knockdown plus trastuzumab treatment. Furthermore, we found that FoxM1 was an important mediator of the invasive potential of resistant cells, such that knockdown of FoxM1 blocked IGF-1–mediated invasion. IGF-1R and HER2 signaling coregulated FoxM1 expression in resistant cells, such that coinhibition of both receptor kinases was required to reduce FoxM1 expression. These results support an important function for FoxM1 in IGF-1–mediated resistance, and suggest that reduced expression of FoxM1 may be necessary to achieve the anti-invasive effect of cotargeted IGF-1R/HER2 therapy.

Past studies have shown somewhat conflicting results regarding the association between overall IGF-1R expression levels and response to trastuzumab (Smith et al., 2004; Köstler et al., 2006; Harris et al., 2007; Gallardo et al., 2012; Yerushalmi et al., 2012). However, there is strong evidence to suggest that cotargeting IGF-1R and HER2 has increased benefit against HER2-positive breast cancers. Blockade of IGF-1R signaling with antibodies (Nahta et al., 2005), tyrosine kinase inhibitors (Nahta et al., 2005; Chakraborty et al., 2008; Esparís-Ogando et al., 2008), genetic knockdown (Huang et al., 2010), or expression of IGF-1–sequestering proteins (Lu et al., 2001; Jerome et al., 2006) has been shown to improve sensitivity to trastuzumab in multiple models of trastuzumab resistance; sensitivity was primarily assessed by proliferation, apoptosis, and xenograft tumor growth in these reports. An important finding of our study was that cotargeting IGF-1R and HER2 had modest, although significant, effects on the growth inhibition of cells with primary trastuzumab resistance, but almost completely suppressed cellular invasion. FoxM1 downregulation appeared to be an essential downstream mediator of the anti-invasive effect of cotargeting IGF-1R and HER2. In addition to blocking invasion, coinhibition of IGF-1R and HER2 induced ADCC of resistant cells, which is believed to be a major mechanism through which antibody-based therapies promote tumor regression. These results support strategies to simultaneously block both signaling pathways and support FoxM1 as a fundamental regulator of cellular invasion in trastuzumab-resistant cancers.

Overall, our results indicate that the invasiveness of resistant cells is codependent on IGF-1R and HER2 signaling, such that coinhibition of both receptors is required to suppress invasion and overcome downstream signaling (Fig. 10D). Constitutively active Src and FoxM1 overexpression overcame the anti-invasive effects of dual IGF-1R/HER2 inhibition. These results lend additional support to the growing concept that Src represents a potential therapeutic target in trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer, and demonstrate that FoxM1 is an important target worthy of further investigation, particularly in the context of cancers that coexpress IGF-1R and HER2. Future experiments will investigate the effects of cotargeting IGF-1R and HER2 on the local invasion and metastasis of resistant tumors in vivo, and the overall contributions of Src-FAK and FoxM1 to the in vivo progression of HER2-positive breast cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Winship Cancer Institute Cell Imaging and Microscopy Center for assistance with microscopy.

Abbreviations

- ADCC

antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- DPBS

Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline

- Erk1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor-1

- IGF-1R

insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor

- IR3

IGF-1R monoclonal antibody clone IR3

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEK

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- NVPAEW541

7-[cis-3-(1-azetidinylmethyl)cyclobutyl]-5-[3-(phenylmethoxy)phenyl]-7H-pyrrolo[2, 3-d]pyrimidin-4-amine, dihydrochloride

- PF573228

3,4-dihydro-6-[[4-[[[3-(methylsulfonyl)phenyl]methyl]amino]-5-(trifluoromethyl)-2-pyrimidinyl]amino]-2(1H)-quinolinone

- PI

propidium iodide

- PP2

4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(dimethylethyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Sanabria-Figueroa, Donnelly, Kaumaya, Nahta.

Conducted experiments: Sanabria-Figueroa, Donnelly, Foy, Buss, Paplomata, Taliaferro-Smith.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Castellino, Taliaferro-Smith, Kaumaya.

Performed data analysis: Sanabria-Figueroa, Donnelly, Foy, Castellino, Nahta.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Sanabria-Figueroa, Donnelly, Foy, Buss, Castellino, Paplomata, Taliaferro-Smith, Kaumaya, Nahta.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute [Grant R01CA157754 (R.N.)] and the Glenn Family Breast Cancer Scholars Program (R.N.) at the Winship Cancer Institute. The Winship Cancer Institute is also supported by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute [Grant P30CA138292].

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Arnould L, Gelly M, Penault-Llorca F, Benoit L, Bonnetain F, Migeon C, Cabaret V, Fermeaux V, Bertheau P, Garnier J, et al. (2006) Trastuzumab-based treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer: an antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity mechanism? Br J Cancer 94:259–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baselga J, Cervantes A, Martinelli E, Chirivella I, Hoekman K, Hurwitz HI, Jodrell DI, Hamberg P, Casado E, Elvin P, et al. (2010) Phase I safety, pharmacokinetics, and inhibition of SRC activity study of saracatinib in patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 16:4876–4883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bektas N, Haaf At, Veeck J, Wild PJ, Lüscher-Firzlaff J, Hartmann A, Knüchel R, Dahl E. (2008) Tight correlation between expression of the Forkhead transcription factor FOXM1 and HER2 in human breast cancer. BMC Cancer 8:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berns K, Horlings HM, Hennessy BT, Madiredjo M, Hijmans EM, Beelen K, Linn SC, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Stemke-Hale K, Hauptmann M, et al. (2007) A functional genetic approach identifies the PI3K pathway as a major determinant of trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Cell 12:395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canonici A, Steelant W, Rigot V, Khomitch-Baud A, Boutaghou-Cherid H, Bruyneel E, Van Roy F, Garrouste F, Pommier G, André F. (2008) Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor, E-cadherin and alpha v integrin form a dynamic complex under the control of alpha-catenin. Int J Cancer 122:572–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr JR, Park HJ, Wang Z, Kiefer MM, Raychaudhuri P. (2010) FoxM1 mediates resistance to herceptin and paclitaxel. Cancer Res 70:5054–5063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter P, Presta L, Gorman CM, Ridgway JB, Henner D, Wong WL, Rowland AM, Kotts C, Carver ME, Shepard HM. (1992) Humanization of an anti-p185HER2 antibody for human cancer therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:4285–4289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty AK, Liang K, DiGiovanna MP. (2008) Co-targeting insulin-like growth factor I receptor and HER2: dramatic effects of HER2 inhibitors on nonoverexpressing breast cancer. Cancer Res 68:1538–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clynes RA, Towers TL, Presta LG, Ravetch JV. (2000) Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytotoxicity against tumor targets. Nat Med 6:443–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobleigh MA, Vogel CL, Tripathy D, Robert NJ, Scholl S, Fehrenbacher L, Wolter JM, Paton V, Shak S, Lieberman G, et al. (1999) Multinational study of the efficacy and safety of humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody in women who have HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer that has progressed after chemotherapy for metastatic disease. J Clin Oncol 17:2639–2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desgrosellier JS, Cheresh DA. (2010) Integrins in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer 10:9–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dua R, Zhang J, Nhonthachit P, Penuel E, Petropoulos C, Parry G. (2010) EGFR over-expression and activation in high HER2, ER negative breast cancer cell line induces trastuzumab resistance. Breast Cancer Res Treat 122:685–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esparís-Ogando A, Ocaña A, Rodríguez-Barrueco R, Ferreira L, Borges J, Pandiella A. (2008) Synergic antitumoral effect of an IGF-IR inhibitor and trastuzumab on HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Ann Oncol 19:1860–1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteva FJ, Valero V, Booser D, Guerra LT, Murray JL, Pusztai L, Cristofanilli M, Arun B, Esmaeli B, Fritsche HA, et al. (2002) Phase II study of weekly docetaxel and trastuzumab for patients with HER-2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 20:1800–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcioni R, Antonini A, Nisticò P, Di Stefano S, Crescenzi M, Natali PG, Sacchi A. (1997) Alpha 6 beta 4 and alpha 6 beta 1 integrins associate with ErbB-2 in human carcinoma cell lines. Exp Cell Res 236:76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy KC, Miller MJ, Overholser J, Donnelly SM, Nahta R, Kaumaya PTP. (2014) IGF-1R peptide vaccines/mimics inhibit the growth of BxPC3 and JIMT-1 cancer cells in vitro and in vivo and combined therapy with HER-1 and HER-2 peptides induces effective anti-tumor effects. Oncoimmunology DOI: 10.4161/21624011.2014.956005 [published ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis RE, Myatt SS, Krol J, Hartman J, Peck B, McGovern UB, Wang J, Guest SK, Filipovic A, Gojis O, et al. (2009) FoxM1 is a downstream target and marker of HER2 overexpression in breast cancer. Int J Oncol 35:57–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo A, Lerma E, Escuin D, Tibau A, Muñoz J, Ojeda B, Barnadas A, Adrover E, Sánchez-Tejada L, Giner D, et al. (2012) Increased signalling of EGFR and IGF1R, and deregulation of PTEN/PI3K/Akt pathway are related with trastuzumab resistance in HER2 breast carcinomas. Br J Cancer 106:1367–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayle SS, Castellino RC, Buss MC, Nahta R. (2013) MEK inhibition increases lapatinib sensitivity via modulation of FOXM1. Curr Med Chem 20:2486–2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Meng Y, Tong Q, Li G, Zhang X, Chen Y, Hu S, Zheng L, Tan W, Li H, et al. (2014) The ErbB2-targeting antibody trastuzumab and the small-molecule SRC inhibitor saracatinib synergistically inhibit ErbB2-overexpressing gastric cancer. MAbs 6:403–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LN, You F, Schnitt SJ, Witkiewicz A, Lu X, Sgroi D, Ryan PD, Come SE, Burstein HJ, Lesnikoski BA, et al. (2007) Predictors of resistance to preoperative trastuzumab and vinorelbine for HER2-positive early breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13:1198–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Gao L, Wang S, McManaman JL, Thor AD, Yang X, Esteva FJ, Liu B. (2010) Heterotrimerization of the growth factor receptors erbB2, erbB3, and insulin-like growth factor-i receptor in breast cancer cells resistant to herceptin. Cancer Res 70:1204–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerome L, Alami N, Belanger S, Page V, Yu Q, Paterson J, Shiry L, Pegram M, Leyland-Jones B. (2006) Recombinant human insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 inhibits growth of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2-overexpressing breast tumors and potentiates herceptin activity in vivo. Cancer Res 66:7245–7252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi JP, Brown NE, Griner SE, Nahta R. (2011) Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15)-mediated HER2 phosphorylation reduces trastuzumab sensitivity of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol 82:1090–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junttila TT, Akita RW, Parsons K, Fields C, Lewis Phillips GD, Friedman LS, Sampath D, Sliwkowski MX. (2009) Ligand-independent HER2/HER3/PI3K complex is disrupted by trastuzumab and is effectively inhibited by the PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941. Cancer Cell 15:429–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumaya PT, Foy KC, Garrett J, Rawale SV, Vicari D, Thurmond JM, Lamb T, Mani A, Kane Y, Balint CR, et al. (2009) Phase I active immunotherapy with combination of two chimeric, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, B-cell epitopes fused to a promiscuous T-cell epitope in patients with metastatic and/or recurrent solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 27:5270–5277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köstler WJ, Hudelist G, Rabitsch W, Czerwenka K, Müller R, Singer CF, Zielinski CC. (2006) Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) expression does not predict for resistance to trastuzumab-based treatment in patients with Her-2/neu overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 132:9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesniak D, Xu Y, Deschenes J, Lai R, Thoms J, Murray D, Gosh S, Mackey JR, Sabri S, Abdulkarim B. (2009) Beta1-integrin circumvents the antiproliferative effects of trastuzumab in human epidermal growth factor receptor-2-positive breast cancer. Cancer Res 69:8620–8628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Zi X, Zhao Y, Mascarenhas D, Pollak M. (2001) Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling and resistance to trastuzumab (Herceptin). J Natl Cancer Inst 93:1852–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata Y, Lan KH, Zhou X, Tan M, Esteva FJ, Sahin AA, Klos KS, Li P, Monia BP, Nguyen NT, et al. (2004) PTEN activation contributes to tumor inhibition by trastuzumab, and loss of PTEN predicts trastuzumab resistance in patients. Cancer Cell 6:117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahta R. (2012) Molecular mechanisms of trastuzumab-based treatment in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. ISRN Oncol 2012:428062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahta R, Yu D, Hung MC, Hortobagyi GN, Esteva FJ. (2006) Mechanisms of disease: understanding resistance to HER2-targeted therapy in human breast cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 3:269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahta R, Yuan LX, Zhang B, Kobayashi R, Esteva FJ. (2005) Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterodimerization contributes to trastuzumab resistance of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 65:11118–11128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PeiróOrtiz-Martínez G, Gallardo F, Pérez-Balaguer A, Sánchez-Payá A, Ponce J, Tibau JJ, L Aópez-Vilaro L, Escuin D, Adrover E, et al. (2014) Src, a potential target for overcoming trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive breast carcinoma. Br J Cancer 111:689–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, et al. (2000) Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 406:747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter CA, Perez-Torres M, Rinehart C, Guix M, Dugger T, Engelman JA, Arteaga CL. (2007) Human breast cancer cells selected for resistance to trastuzumab in vivo overexpress epidermal growth factor receptor and ErbB ligands and remain dependent on the ErbB receptor network. Clin Cancer Res 13:4909–4919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz KJ, Grabellus F, Callies R, Otterbach F, Wohlschlaeger J, Levkau B, Kimmig R, Schmid KW, Baba HA. (2005) High expression of focal adhesion kinase (p125FAK) in node-negative breast cancer is related to overexpression of HER-2/neu and activated Akt kinase but does not predict outcome. Breast Cancer Res 7:R194–R203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman AD, Fornier MN, Esteva FJ, Tan L, Kaptain S, Bach A, Panageas KS, Arroyo C, Valero V, Currie V, et al. (2001) Weekly trastuzumab and paclitaxel therapy for metastatic breast cancer with analysis of efficacy by HER2 immunophenotype and gene amplification. J Clin Oncol 19:2587–2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. (2014) Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 64:9–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. (1987) Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science 235:177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, Fleming T, Eiermann W, Wolter J, Pegram M, et al. (2001) Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med 344:783–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BL, Chin D, Maltzman W, Crosby K, Hortobagyi GN, Bacus SS. (2004) The efficacy of Herceptin therapies is influenced by the expression of other erbB receptors, their ligands and the activation of downstream signalling proteins. Br J Cancer 91:1190–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner M, Kapanen AI, Junttila T, Raheem O, Grenman S, Elo J, Elenius K, Isola J. (2004) Characterization of a novel cell line established from a patient with Herceptin-resistant breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 3:1585–1592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadlamudi RK, Sahin AA, Adam L, Wang RA, Kumar R. (2003) Heregulin and HER2 signaling selectively activates c-Src phosphorylation at tyrosine 215. FEBS Lett 543:76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varchetta S, Gibelli N, Oliviero B, Nardini E, Gennari R, Gatti G, Silva LS, Villani L, Tagliabue E, Ménard S, et al. (2007) Elements related to heterogeneity of antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity in patients under trastuzumab therapy for primary operable breast cancer overexpressing Her2. Cancer Res 67:11991–11999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellon L, Menendez JA, Lupu R. (2005) AlphaVbeta3 integrin regulates heregulin (HRG)-induced cell proliferation and survival in breast cancer. Oncogene 24:3759–3773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SE, Xiang B, Zent R, Quaranta V, Pozzi A, Arteaga CL. (2009) Transforming growth factor beta induces clustering of HER2 and integrins by activating Src-focal adhesion kinase and receptor association to the cytoskeleton. Cancer Res 69:475–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XH, Flores LM, Li Q, Zhou P, Xu F, Krop IE, Hemler ME. (2010) Disruption of laminin-integrin-CD151-focal adhesion kinase axis sensitizes breast cancer cells to ErbB2 antagonists. Cancer Res 70:2256–2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerushalmi R, Gelmon KA, Leung S, Gao D, Cheang M, Pollak M, Turashvili G, Gilks BC, Kennecke H. (2012) Insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-1R) in breast cancer subtypes. Breast Cancer Res Treat 132:131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Huang WC, Li P, Guo H, Poh SB, Brady SW, Xiong Y, Tseng LM, Li SH, Ding Z, et al. (2011) Combating trastuzumab resistance by targeting SRC, a common node downstream of multiple resistance pathways. Nat Med 17:461–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang G, Brantley-Sieders DM, Vaught D, Yu J, Xie L, Wells S, Jackson D, Muraoka-Cook R, Arteaga C, Chen J. (2010) Elevation of receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2 mediates resistance to trastuzumab therapy. Cancer Res 70:299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.