Introduction

Panel data are collected for a lot of different reasons (see Hsiao, 2003; Baltagi, 2005). In psychological research, most now agree that we do this kind of longitudinal data collection because we want to “measure changes as quickly as possible.” If we are studying individuals these are labelled “within person changes.” If we are studying larger units of aggregations, such as colleges or countries, these are often labelled “within-unit changes.” Nonetheless, the key feature is we examine change within the units we are studying. Many important issues in the measurement of change have been raised in classic treatments of the analysis of change (e.g., Harris, 1963; Cattell, 1966; Horn, 1971), and many of these have not fully been resolved (e.g., Nesselroade & Baltes, 1979; Collins & Sayer, 2001). The purpose of this paper is to highlight some classic issues in the measurement of change and to show how contemporary solutions can be used to deal with some of these issues.

Five classic issues will be raised here: (1) Separating individual changes from group differences; (2) options for incomplete longitudinal data over time, (3) options for nonlinear changes over time; (4) measurement invariance in studies of changes over time; and (5) new opportunities for modeling dynamic changes. For each issue we will describe the problem, and then review some contemporary solutions to these problems using existing panel data. This is not intended as an overly technical treatment, so only a few basic equations are presented, examples will be displayed graphically, and more complete references to the contemporary solutions will be given throughout.

In this paper, we use a common set of data set to illustrate communalities of these issues. Publicly available data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) and the Asset and Health Dynamics of the Oldest Old Study (AHEAD; see Juster & Sussman, 1995; Cagney & Lauderdale, 2002; Freedman, Aykan & Martin, 2002; Rodgers, Ofstedal & Herzog, 2003; McArdle, Fisher & Kadlec, 2007) are combined. The HRS-AHEAD studies have been heralded for their inclusion of cognitive measures in a national telephone-based survey of health and economics (see Herzog & Wallace, 1997). At the same time, the HRS-AHEAD studies have been criticized for lacking key many other issues, and we address these issue here. Prior research using cognitive data from the HRS/AHEAD has examined cohort-level changes in cognition using longitudinal data from the HRS-AHEAD (1993–2000; e.g., Freedman et al., 2001; Rodgers, Ofstedal, & Herzog, 2003). Other studies have examined intra-individual differences in cognition by age (McArdle, Fisher & Kadlec, 2007).

Selected data from the Rodgers et al. (2003) paper are presented in Table 1. In the first part of this table we list summary statistics for adults over age 50 on the overall cognitive scores collected among self-respondents across four waves (1993, 1995, 1998, and 2000) in a nationally representative sample of persons (using sampling weights) over the age of 50. These statistics are based on almost n~3,000 who have participated in all four occasions of measurement, each about 2 years apart. In the second part of this table (1b) we list the same statistics for all the people measures, most of whom were not measured at all occasions. These include data collected on N=10,498 individuals between ages 50–85 (median= 71) and D=25,029 interviews. In this matrix we introduce a new binary variable termed Dropout (0,1), which indicates whether or not the person has dropped out of the study. Of course, the increased sample size emphasizes the fact that we need to consider sampling and attrition. This paper use the same cognitive data as Rodgers et al. (2003) but describe a series of analyses which capitalize on using new structural measurement techniques and all available HRS data (e.g., McArdle, Ferrer-Caja, Hamagami, & Woodcock, 2002; McArdle, 2007).

Table 1.

Descriptive information on longitudinal data for primary participants in the Health and Retirement Survey (using HRS sampling weights; Rodgers, Ofstedal & Herzog, 2003).

| [1a]: Descriptive statistics for the constant HRS sample (n = 2,766) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | Std Dev | Minimum | Maximum | Notes |

| CA[1] | 62.06 | 1416 | 2.9 | 100. | 0–35 rescaled as 0–100 |

| CA[2] | 62.46 | 1408 | 8.6 | 100. | at Testing 2 |

| CA[3] | 60.93 | 1462 | 5.7 | 100. | at Testing 3 |

| CA[4] | 58.33 | 1528 | 2.9 | 100. | at Testung 4 |

| Age[1] | 81.92 | 485 | 65.2 | 100.9 | AHEAD/HRS |

| Pearson Correlations | CA[1] | CA[2] | CA[3] | CA[4] | Age[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA[1] | 1.00 | ||||

| CA[2] | .636 | 1.00 | |||

| CA[3] | .613 | .660 | 1.00 | ||

| CA[4] | .561 | .607 | .655 | 1.00 | |

| Age[1] | −239 | −.263 | −.296 | −.326 | 1.00 |

| [1b]: Descriptive statistics for the entire HRS sample (N = 10,498) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Size | Mean | Std Dev | Minimum | Maximum | Notes |

| CA[1] | 5,423 | 57.37 | 1611 | 0 | 100. | 0–35 rescaled |

| CA[2] | 4,411 | 58.42 | 1619 | 0 | 100. | at Testing 2 |

| CA[3] | 8,392 | 63.13 | 1578 | 0 | 100. | at Testing 3 |

| CA[4] | 6,819 | 62.23 | 1547 | 2.9 | 100. | at Testing 4 |

| Age[1] | 10.504 | 75.84 | 822 | 62 | 107.7 | AHEAD or HRS |

| Dropout (0,1) | 10,504 | 0.737 | 45.1 | 0 | 1 | 0=complete |

| Pearson Correlations | CA[1] | CA[2] | CA[3] | CA[4] | Age[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA[1] | 1.00 (5,423) | ||||

| CA[2] | .695 (4,317) | 1.00 (4,411) | |||

| CA[3] | .637 (3,508) | .692 (3,449) | 1.00 (8,392) | ||

| CA[4] | .565 (2,933) | .610 (2,879) | .677 (6,566) | 1.00 (6,819) | |

| Age[1] | −.258 (5,423) | −.280 (4,411) | −.357 (8,392) | −.350 (6,819) | 1.00 (10,504) |

| Dropout | −.305 (5,423) | −.327 (4,411) | .100 (8,392) | .211 (6,819) | −.453 (10,504) |

1: Separating Individual Changes from Group Differences

An initial concern here is the separation of inferences about (a) differences between people and (b) changes within people (McArdle, 2008). The current issue can be stated as is, “what separation of groups and persons is best for my problem?”

A common solution to this problem simple subtraction of any two scores for any person is termed a “difference score” and these are changes within a person over occasions are formally written for each person as

| [1] |

Although this equation is quite clear, one possible source of confusion is that we often use the formula for “difference” to define a “change.” This equation highlights the key purpose of most longitudinal measurement data---to detect differences in the patterns of individual changes. In addition, now that we have an explicit definition of changes [1] we can consider some key problems in their measurement (see Nesselroade & Baltes, 1979).

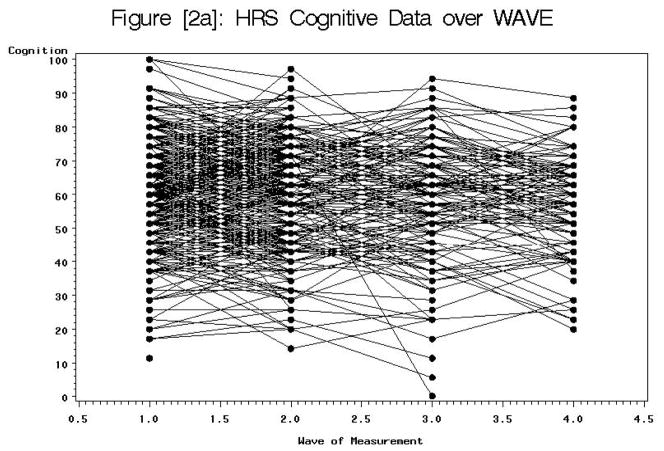

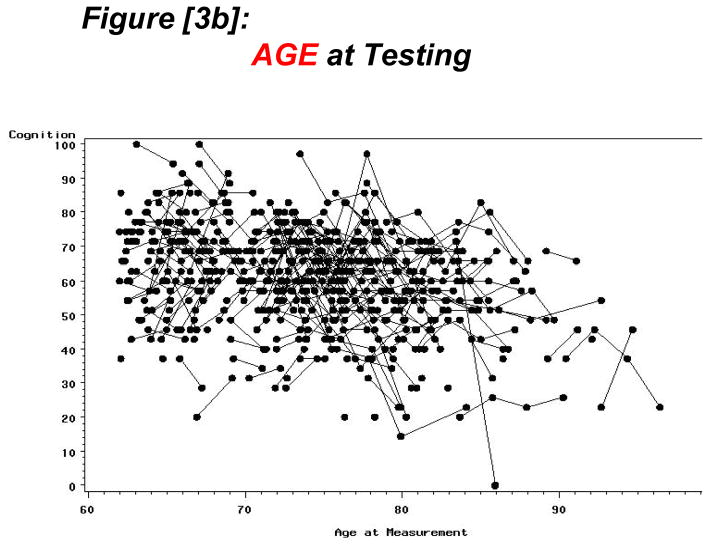

Figure [2] gives a plot of the longitudinal data we use here. These data are raw scores for each person come from four occasions (t=4) of measurement the cognitive abilities of Table 1 (CA[t]). The lines drawn here connect the data from one person over each occasion, so these lines are referred to as “individual trajectories.” In order to be clear, the lines of Figure [1] are only drawn for a random set of 5% of the overall HRS sample (i.e., n~500). However, the summary statistics for the full set of CA[t] data are listed in Table [1]. Among many possible group differences, we study different levels of Age-at-Testing. Although not presented here, if we would display separate plots, it would appear that higher scores are found for persons who are younger (and have higher levels of Education).

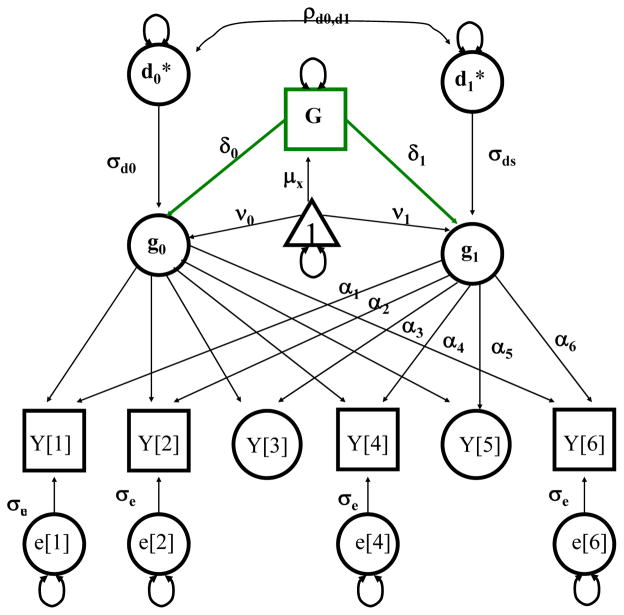

Let us now consider ways to analyze these kinds of longitudinal data. Following the logic of equation [1], we can calculate the change scores for each pair of time points, and then write a regression equation in which this change is the dependent variable regressed on the group differences (i.e., Age, Dropout) between the people. This change-regression is an elementary description of the what is widely known in statistic as a “mixed model,” and this attempts to identify the “between-person differences in within-person changes” (Nesselroade & Baltes 1979). One popular collection of ideas about organizing group and individual differences in changes can be represented as a latent variable path diagram, and one of these is presented in Figure 2. Due to its flexibility, this classic idea about a model for changes has been revived in recent work (see Bayley, 1966; Rogosa, 1985; cf., Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992).

Figure 2.

LCM with an external X variable effecting both the common levels and slopes

A comprehensive version of this mixed-model concept is termed a “latent curve” or “multi-level model” for the analysis of longitudinal data, and this can be written for multiple time points (t) as

| [2] |

where the individual score (Y) at any time point (t) is considered a function of three underlying components: (1) the intercept score g0, which does not change over time – this is the constant part of the scores. (2) The slope score, g1, which does not itself change over time, but whose influence is multiplied through a group basis coefficient, B[t] which can change over time for the whole group – this is the systematic change. (3) A unique or residual score u[t] for the individual, which changes over time but is presumably uncorrelated with any other score – this is the random change. This organization of observations of multiple time points of data into only three underlying components is used to organize the individual differences in changes over time, and it is termed the “level 1 model.”

Assuming we have some measure of group differences, measured and coded as X, it is also typical to propose an additional set of restrictions where we write regression equations

| [3] |

where two latent components from the previous equations (g0, g1) are now thought to be outcomes of the group differences in X with intercepts (ν0, ν1), slopes (γ0, γ1) and residuals (d0, d1). These equations are used to describe the group differences in the components of changes, so this termed the “level 2 model.”

Latent growth curve analyses can be calculated using many available mixed-effects computer packages (e.g., SAS MIXED and NLMIXED; Littell, et al, 1996; Verbeke & Molenberghs, 2000) and structural equation modeling programs (SEM; see Ferrer, Hamagami & McArdle, 2003; Joreskog & Sprbom, 1979; Muthen & Muthen, 2006). Because this can be examined as an SEM, the path diagram of Figure 2 may be a useful representation of this kind latent growth model. The observed variables are drawn as squares, the unobserved variables are drawn as circles, and the required constant is included as a triangle. Model parameters representing “fixed” or “group” coefficients are drawn as one headed arrows while “random” or “individual” features are drawn as two-headed arrows. In this case the initial level and slopes are often assumed to have to be latent random variables with “fixed” means (μ0, μ1) but “random” variances (σ02, σ12) and latent variable correlations (ρ0s). (The standard deviations (σj) are drawn in the picture to permit the direct representation of the covariances as scaled correlations.) The unique terms are assumed to be normally distributed with mean zero and variance (σu2) and are presumably uncorrelated with all other components. In order to deal with incomplete cases we write the first level of variables as “circles within squares” (as in McArdle, 1994; McArdle & Hamagami, 2001; McArdle & Nesselroade, 2003).

Using the available computer programs we can obtain the following numerical results. The first model fitted (2a) is a no-change model and was fitted to the raw data used to form Table 1b with only 3 parameters. The results include the three parameters which are expected to be constant over age: (a) a constant mean (μ0=60.2); (b) a constant covariance (σ02=178), and (c) a constant unique variance (σu2=79). The ratio of the two variance components leads to a high estimate of the intra-class correlation (η2= 0.69), and this indicated the individual scores are widely separated and positively correlated from one occasion to another. This model has a likelihood (fMLE=−10748) that represents a notable statistical improvement (with χ2=11337 on df=1) over the entirely random (i.e., zero correlation) case. A second model, labelled “+Drop” here, adds a single parameter to assess the mean difference due to dropout on the previous results. These results imply the persons who later dropped out (for any reason) scored about 4% points lower at the initial testing (β0=−3.6, with χ2=86 on df=1), and this could be an important consideration.

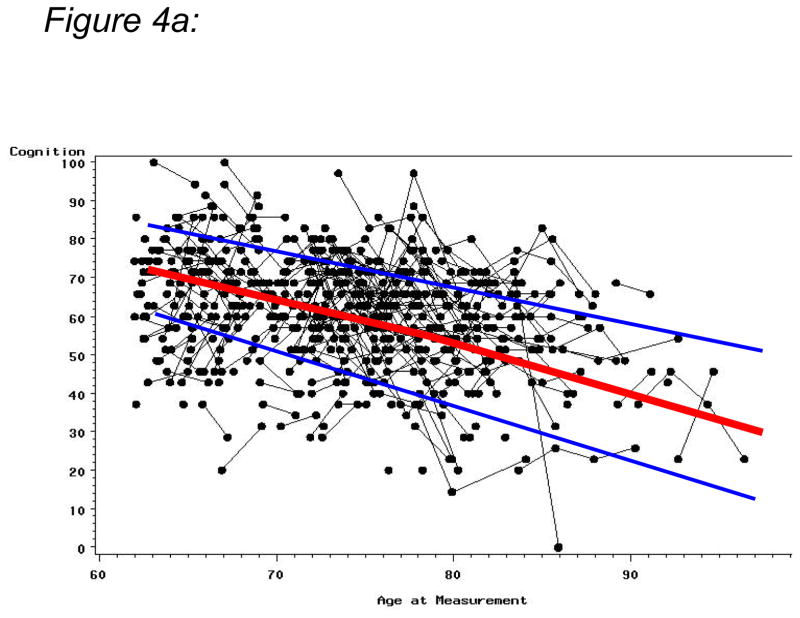

The second model fitted (2b) is a linear mixed-effects model using wave-of-testing as the basis for change – as in Figure 1. The results include three time-constant parameters (μ0=60.5, σ02=199, and σu2=73) plus three time-dependent slope parameters indicating a very small decrease in means (μ1=−.09) over every wave of testing, and increases in variances and covariances over every wave (σ12=1.4, ρ01=−.30). The linear wave model (fMLE=−10404) is a statistical improvement over the entirely random model (with χ2=10494, on df=3) and, more critically, a statistical improvement over the previous no-change level model (χ2=843 on df=3). This improvement in fit appears substantial but, as can be seen in Figure 1, these systematic changes over time represent only a very small average impact compared with the large overall variation in the individual growth curves. The group differences only show the dropouts were lower at the starting point (β0=−5.0) but it was not possible to estimate any differences in slope (β1<.01).

Figure 1.

Plots of individual longitudinal trajectories (5% sample of the HRS primary participants)

2: Options for Incomplete Longitudinal Data Over Time

All longitudinal analyses require the choice of the basis or timing for analysis and, to the surprise of many researchers, this is not a fully restricted aspect of the analysis. Thus, the current challenge can be stated as is, “what basis of timing is best for my problem?”

Part of this challenge comes from the new opportunities for dealing with incomplete data. Obviously there is a great deal of incomplete data in the HRS longitudinal study (see Table 1), but this is a typical problem in longitudinal research. The Rodgers et al. (2003) analysis described the use of a multiple imputation procedure for handling incomplete data. This method accounted for stable and time-varying covariates as well as covariation in the cognitive measures between and across waves (using IVEware). This approach seems reasonable for data missing over time, and it can be used when the incomplete due to attrition and other factors and not missing at random (MAR). The same sets of assumptions form the basis of any SEM analyses which includes “all the data” – not simply the complete cases (e.g., McArdle, 1988, 1990, McArdle & Anderson, 1990). While we do observe non-random attrition, our goal is to include all the longitudinal and cross-sectional data to provide the best estimate of the parameters of change as if everyone had continued to participate (McArdle & Hamagami, 1991; Little, 1995; Diggle, Liang, & Zeger, 1994; McArdle & Bell, 2000).

This mixed-model approach to growth curve analysis offers advanced techniques for dealing with the problem of unbalanced and non-randomly incomplete data. In computational terms, the available information for any subject on any data point (i.e., any variable measured at any occasion) is used to build up maximum likelihood estimates (MLE) using a numerical routine that optimizes the model parameters with respect to any available data. These MLE are based on fitting structural models to the raw score information for each person on each variable at each time (e.g., McArdle et al, 2002). The goodness-of–fit of each model presented here will be assessed using classical statistical principles about the model likelihood (fMLE) In most models to follow, we use the MAR assumption to deal with incomplete longitudinal records, but we test these assumptions whenever possible (e.g., Little, 1995; Cnaan, et al, 1997). This MAR assumption has become an incomplete data design problem (McArdle, 1994) which includes assumptions about age changes in different cohorts (e.g., Meredith & Tisak, 1990; McArdle & Anderson, 1990; Miyayzaki & Raudenbush, 2000).

This realization that we can deal with incomplete data has a fundamentally important impact on the possibilities for data analysis. In the latent growth model of Equation [2] the B[t] represents a set of basis coefficients describing the function of the timing of the observations. Many alternative considerations for the description of these data can be conveniently considered as the specific variations of latent growth model [2] because we write

| [4] |

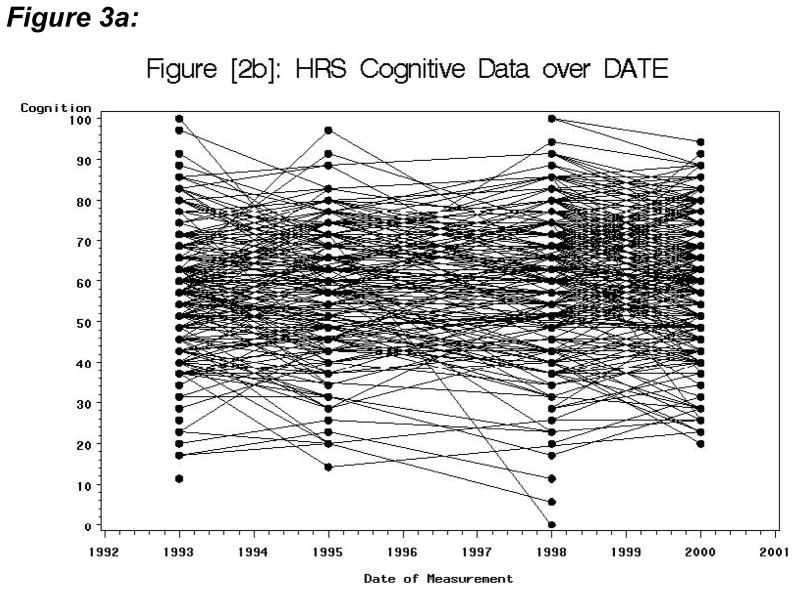

In this equation the first model has no basis, and thus represents the no-change model stated earlier. The other three models have a basis (generally labeled as B[t]), but this basis is defined in a different way for each. These are comparable to fitting models with different X-axes (re-centered, rescaled, etc.) to different forms of the Figure 1. Figure 3a shows the same raw data plotted over Date-of-Testing (with a 3 year time-lag between times 2 and 3). As another alternative, Figure 3b shows the very same data plotted over the Age-at-Testing of the individuals. While this looks dramatically different form of the data, especially the extreme scores, the points plotted on the Y-axis are identical but the X-axis has changed. Since the results of any model depend on the scaling of the predictors, it follows that this choice of a basis for timing is one the most important sources of variance in longitudinal data, and is both an empirical and substantive issue.

Figure 3.

Figure 3a. HRS Cognitive Data over DATE-OF-TESTING

Figure 3b. HRS Cognition Scores over AGE at Testing

These alternative models are nested under the random baseline model, but the three alternatives models are not completely nested under one another, so no direct chi-square comparison can be strictly considered. In previous research where we have been interested in chronological age changes using date where there was no common starting-point of specific interest (t=0), it seemed most natural to use a timing of observation based on the observed or chronological age at the occasion of measurement (i.e., t=Age). Of course, for this age-basis model to be viable, we need to presume the un-testable MAR assumptions apply to this age dimension. This implies the score measured on a person at each age gives us some indication of their likely scores at the ages not measured, and persons measured at specific ages represent the age-based scores for anyone.

The third model fitted (3a) is a linear mixed-effects model using date-of-testing as the basis for change, now considering both the incomplete and complete trajectories of data points. The results include three time-constant parameters (μ0=61.2, σ02=186.0, and σu2=71.2) plus three time-dependent slope parameters indicating decreases in means (μ1=−1.4) over every year of testing, along with increases in variances and covariances over each year (σ12=7.5, ρ01=−.13). Once again, as can be seen in Figure 3a, this is a relatively small average impact compared with the apparent variation in the individual growth curves. The linear date model likelihood (fMLE=−9995) is a statistical improvement over the entirely random model (with χ2=10903, on df=3) and a statistical improvement over the previous no-change level model (with χ2=434, on df=3). The introduction of a contrast describing dropout differences (Drop) adds to these basic results, and suggests dropout impacted both the starting point (i.e., β0=13.5, higher scores in 1993) and the year-to-year slope (β1=−3.5 additional difference per year). This accurately reflects the fact that dropout occurred at later dates, and that the persons who dropped out were on lower trajectories.

The fourth model fitted (3a) is a linear mixed-effects model using age-of-testing as the basis for change. This model was fitted with the chronological age recentered so B[t]= Age[t]−75, so the results include the three time-constant parameters “at age 75” (μ0=59.8, σ02=131.3, and σu2=78.7) plus three time-dependent slope parameters indicating decreases in means (μ1=−.83) over “every year of age,” and increases in variances and covariances (σ12=.23, ρ01=+.27) over each year. Now, looking back to Figure 3b, this is a relatively large average impact compared with the apparent variation in the individual growth curves (i.e., −8.3 points lost per decade). The linear age model likelihood (fMLE=−9995) is an improvement over the entirely random model (with χ2=10903, on df=3) and a statistical improvement over the previous no-change level model (with χ2=434, on df=3). The dropout differences do not alter these basic results, and suggests dropout differences at age 75 (i.e., β0=−6.3 lower scores for dropouts) and an additional year-to-year slope (β1=−.25 more decline per year). This suggests that the previous dropout results were age related, and once age is used as the basis, we see that the persons who dropped out were on much lower trajectories.

In the form of Equation [4] it becomes clear that the use of Wave[t] represents the fitting of a linear growth model through the four waves of data presented in Figure 1 (this seems closest to the regression approach by Rodgers et al. 2003 for cohort changes). The alternative use of Date[t] represents the fitting of a linear growth model through the longitudinal trajectory data presented in Figure 3a. The alternative use of Age[t] represents the fitting of a linear growth model through the longitudinal trajectory data presented in Figure 3b, once again considering both the incomplete and complete trajectories of data points. Even with the large blocks of incomplete data, this picture of decline trajectories appears to be much clearer than in the previous two pictures because in 3b we have substantially stretched out the X-axis to reflect more disparate ages. The changes are both over the wide X-axis (age differences between people) and in the narrow bands represented by the line segments (age changes within people). Given these results, and the MAR assumptions described above, there is evidence of a comparative advantage in using age-at-testing instead of wave or date-of-testing as the major a dimension of group and individual change, so we pursue this approach in the rest of the analyses here.

3: Dealing With Nonlinear Changes Over Time

It is possible to deal with nonlinearity of the changes over age in several ways, but the challenge is “What form of nonlinearity is best for my problem?”

The simplest nonlinear models are based on altering the values of the basis B[t] (as in McArdle & Nesselroade, 2003). The curve basis can be made to reflect specific nonlinear hypothesis, such as an exponential basis (i.e., B[t]=[exp{(−t−1)π}], with growth rate parameter π), and including individual coefficients in rates (πn; McArdle & Hamagami, 1996; McArdle et al, 2002). In another alternative basis we can allow the curve basis to take on a shape based on the empirical data (e.g., Meredith & Tisak, 1990; McArdle, 1986). In this alternative the factor loadings (B[t]) are now estimated from the data as any factor loadings and we obtain what should be an optimal shape for the group curve.

But a far more common way to allow for nonlinear relationships is this is to expand the basic specification equation to include multiple linear bases. We can write

| [5] |

where the B1[t] and B2[t] represent different basis coefficients (i.e., B1[t] ne B2[t]) which are added up to describing the function of the observations at different ages. One less simplistic feature of this model is that there are also an additional set of latent scores (g2).

A wide variety of other options can be explored using Equation [5]. For example, the linear model just used can be considered as the subset of Equation [5] where B2[t]= 0. This can then be compared to the well known used of this model is the quadratic change model where, for example, we use include fixed coefficients B1[t]=Age[t] and B2[t]= ½Age[t]2. This polynomial model can be extended to a cubic change model by introducing yet another set of coefficients (B3[t]= 1/3 Age[t]3) and scores (g3). In all cases the means and variances and correlations among the parameters can be independently estimated using longitudinal growth data.

Another simple and popular variation is a two part spline model fitted by first defining an age of turning or knot-point (e.g., τ=75) and then writing fixed coefficients of B1[t]={Age[t] if Age[t] < τ } and B2[t]={Age[t] if Age[t] > τ}. This simple coding creates the possibilities of two segments of age where the components of change can differ (e.g., before and after age 75). One common statistical problem arising in mixed models of this variety is that the correlation of the two age slopes hits a boundary condition (ρs1,s2=1), so it is not really estimated and can be forced to zero without loss of fit. This lack of empirical identification is often due to few people with longitudinal measurements crossing both age segments, but this does not seriously bias the other estimates (as in Hamagami & McArdle, 2000). If no turning point age is defined substantively, τ can be estimated from the data (e.g., using NLMIXED; see Cudeck & Klebe, 2002; McArdle & Wang, 2007; Wang & McArdle, 2008).

The results of Table 4 include four alternative models of age changes. The first model (4a) is simply a reparameterization of the previous linear age model where we have rescaled B[t]=(Age[t]−75)/10, so the intercepts are centered at age 75 and the slopes represent change per decade of age. The results exhibit the same fit as before, but the parameters of the slopes show the average change is μ1=−8.3 over “every decade of age,” and substantial increases in variances and covariances (σ12=23.4, ρ01=+o.27) over each decade.

Table 4.

Numerical Results for a consecutive sequence of Exactly Identified Common Factor Models to the eight cognitive sub-scales (see Table 5)

| Statistic | F=0 | F=1 | F=2 | F=3 | F=4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | 25868. | 5688. | 474. | 60. | 2. |

| df | 28 | 20 | 13 | 7 | 2 |

| Dχ2 | -- | 20180. | 5214. | 414. | 58. |

| Ddf | -- | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| εa | .245 | .136 | .048 | .022 | .003 |

| −95%(ea) | .242 | .133 | .044 | .017 | .000 |

| +95%(ea) | .247 | .139 | .052 | .027 | .017 |

| rmsr | .287 | .156 | .046 | .009 | .002 |

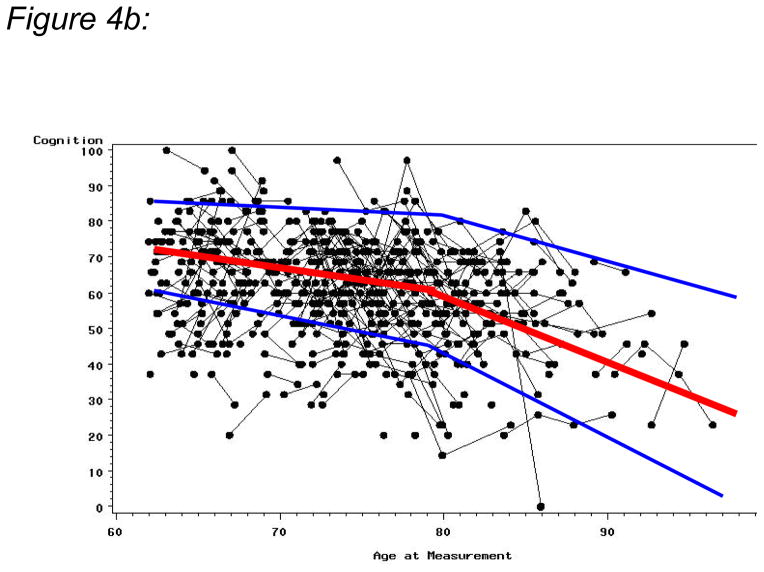

In model (4b) the same rescaled age basis was used in a quadratic change model, and there is a slight improvement in fit from the introduction of the new score (y2) and four new parameters (χ2=47 on df=4). The mean growth curve can be written using the stating slope (μ0=60.4), and two negative parameters, μ1=−8.1 (per decade) and μ1=−1.2 (per half decade squared). Unfortunately, a big problem here is that the additional variance and covariance terms associated with the second slope were “not estimable” within this basis. To explore this problem, a cubic change model (4c) was fitted and, while improving the fit (χ2=11 on df=2), resulted in the same problems for variance estimation. These are not strictly mathematical problems, because the parameters are certainly identified in theory, but these are common statistical problems in these kinds of data.

Finally, we fit a two part spline model (3d) by defining the knot-point at τ=75. A variety of additional knot points were investigated, and an optimal knot point was found at τ=73.2 (using NLMIXED), but age 75 yielded almost as good a fit so it was retained here. The results of table (3d) give the estimates for these two separate age segments: (a) The intercepts at age 75 have a mean and variance (μ0=60.4 with σ02=170.5), (b) the early age slopes, from the youngest ages up to age 75, exhibit a large (negative) mean and variance (μ1=−6.9 with σ12=71.4), (c) the later age slopes, from age 75 to the oldest ages, exhibit an even larger negative mean and positive variance (μ2=−9.5 with σ22=94.7), and (d) the fit is a clear improvement over the linear growth model (χ2=53 on df=3). From this result, it appears a nonlinear age change model should include both variance components of cognitive decline between Age 65 and 75 (−7%) but possibly different components with even more cognitive decline between Age 75 and 85 (−10%). The trajectory plot of Figure 5 shows the informative results of this turning point model.

Figure 5.

Two Cognitive Factors are well measured by the current HRS measures

4: Invariance of Measurement over Time

Another challenge is raised in longitudinal data analysis is the important question of: “Have we measured the same constructs at all occasions?” It is typically assumed that if we measuring exactly the same variables (Y[t]) under exactly the same conditions and use the same scoring system al all occasions we. However, this raises the useful questions of factorial invariance over time (McArdle, 2007). When we can form a test of these question as a measurement hypothesis, we can guide the longitudinal research along a sturdier path.

To start these kinds of measurement analyses we first select a set of data that only represent one occasion of measurement. Under standard assumptions is usually the first occasion or the occasion with the most measures. We typically remove the means and start with deviation scores and consider a measurement model

| [7] |

where each separate variable Y[1] is represented by the same underlying common factor score (f[1]) based on a multiplicative factor loading (λ[1]) plus a unique factor score (u[1]). At this point, this kind of common factor model only needs to apply to the model within each occasion.

The HRS cognitive score is formed from several different sub-scales (for details see McArdle et al., 2007). For illustrative purposes here, we fit these kinds of common factor models to data from eight of these subscales. Table 4 lists the numerical results of goodness-of-fit for different common factor models fitted to the cognitive data sub-scales of the HRS. One of the most obvious results found here is that the one common factor model does not fit these data very well (i.e., RMSEA εa=.136). In contrast, the two common factor model fits much better (εa=.048), and the three common factor model is nearly perfect (εa=.022).

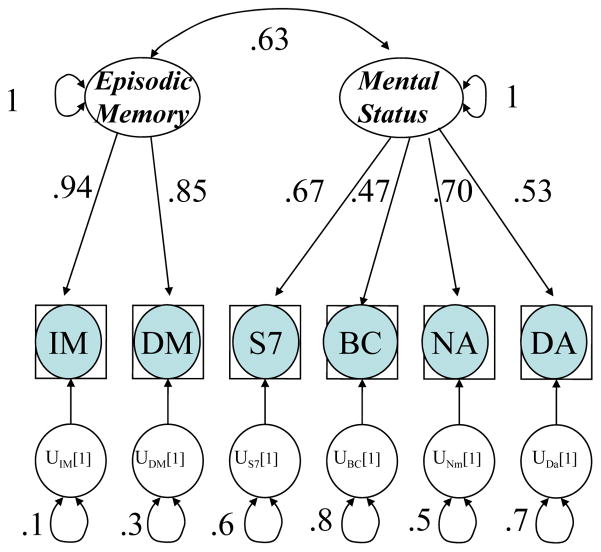

Although we do have prior hypotheses about these cognitive sub-scales (see Horn & McArdle, 2007), we carried an exploratory rotation (using oblique Promax) of the two and three factor solutions, and the resolution of the three common factors is listed in Table 5. These results show strongest loadings for the first two variables, indicating a common factor termed Episodic Memory (EM), a second factor including the next four variables, indicating a different common factor termed Mental Status (MS), and a third common factor indicated by the last two variables and termed Crystallized Knowledge (Gc; for details, see Horn & McArdle, 2007). Since the final two sub-scales (SI and VO) are not measured at all occasion in the HRS, we eliminate these from our consideration and form a final within-occasion model of two common factors drawn as the path diagram in Figure 6.

Table 5.

Results for a three common factor model (MLE with Promax; ρ12=.23, ρ13=.22, ρ23=.50, εa =.022)

| Measure | Factor λ1 | Factor λ2 | Factor λ3 | Unique ψ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR[1] | .80 | .10 | −.01 | .27 |

| DR[1] | .92 | .02 | .02 | .13 |

| S7[1] | −.00 | .61 | .11 | .54 |

| BC[1] | −.06 | .57 | −.04 | .73 |

| NA[1] | .06 | .64 | .05 | .52 |

| DA[1] | .01 | .59 | −.10 | .70 |

| VO[1] | −.00 | .21 | .47 | .63 |

| SI[1] | .01 | .01 | .85 | .26 |

Notes: IR = Immediate Word recall (10 items); DR = Delayed Recall (10 items); S7 = Serial 7s (5 trials); BC = Backward Counting (2 trials); NA = Names (4 items); DA = Dates (3 items); VO = Vocabulary (5 items); SI = Similarities (5 items).

Figure 6.

The HRS Cognitive Measures are Invariant Over Time and Model-of-Testing

From the perspective of longitudinal measurement, this failure of the single factor model is highly informative. Although this is an exploratory analysis, and requires further validation, this implies the cognitive ability score used in the previous figures and latent curve models (CA[t]) is likely to represent an aggregate of at least two or more different cognitive functions operating in different ways over time (see McArdle & Woodcock, 1997; Horn & McArdle, 2007; McArdle, 2007). This is not seen here as a failing of the latent curve models, because this was a measurement assumption that was not testable in the previous latent curve models. Nevertheless, our use of an aggregate that represents different constructs may have been the reason why some of the simpler models could not fit so well. Although many other measurement issues could be considered here (see McArdle et al., 2007) it is possible the use of an over-aggregated and, hence, mislabelled score in a latent curve model – Attempts to fit models of a complex composite can be one of the most vexing aspects of any longitudinal data analysis.

Two occasions of data provide the next opportunity to characterize some of the key longitudinal questions about the measurement of change. These data can come from the first and second occasion, or the first and last occasions, or the two most substantively meaningful occasions. In two-occasion longitudinal data where the same variables (Y[t]) are repeatedly measured at a second occasion (over time, or over age, etc.) we can write

| [8] |

where each matrix now has a bracketed 1 or 2 designating the occasion of measurement. This kind of structural factor model applies to mode within each occasion and between the two occasions (see Meredith, 1964; McArdle & Nesselroade, 1994; Meredith & Horn, 2001).

This organization of the factor model permits a few key questions to be examined using specific model restrictions. The first question we can evaluate is whether or not the same number of factors are present at both occasions – “Is the number of common factors K[1]=K[2]?” Assuming this leads to a reasonable fit, we can then ask questions about the invariance of the factor loadings Λ[t] over time – “Does Λ[1] = Λ[2]?” Another set of questions can be asked about the invariance of the factor score f[t] over time – “For all persons N, is f[1]n = f[2]n ?” This last question is examined through the correlations over time – “Does ρ[1,2]=1?” In a seminal series of papers, Meredith (1964) extended selection theorems to the common factor case (see Meredith & Horn, 2001). As it turns out, these principles of factorial invariance for multiple groups also apply to multiple occasions.

As many researchers have noted, these questions about the stability of the factor pattern and the stability of the factor scores raise both methodological and substantive issues. Most usefully, this use of multiple indicators allows us to clearly separate the stability due to (a) the internal consistency reliability of the factors and (b) the test-retest correlation of the factor scores. Each set of model restrictions of factor invariance deals with a different question about construct equivalence over time. We can examine the evidence for these questions using the SEM and goodness-of-fit techniques (McArdle, 2007).

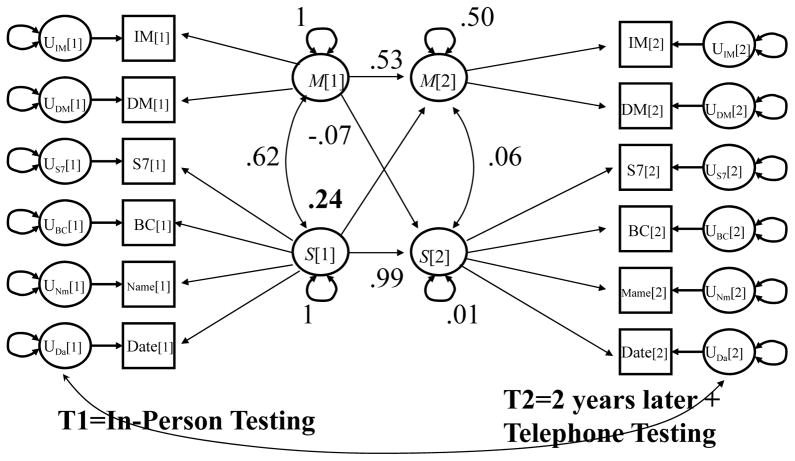

These kinds of two-occasion models are fitted to the HRS data using the general framework of the path diagram of Figure 7. The six sub-scales that are repeated are considered to represent two different common factors (EM[t] and MS[t]) at each of the first two occasions. Of key importance here is that the first occasion is typically carried out “face-to-face” while the second occasion is often done over the “telephone.” This means that the hypothesis of invariance applies to both time and “modality.”

Figure 7.

A Bivariate Latent Difference Score (LDS) Model

The numerical results of the goodness-of-fit of a series of models are listed in Table 6. These models are fit with the most restricted model as a starting point – the one common factor model with factor loadings and uniquenesses constrained to be equal over time. As expected from the prior results, this model does not fit the HRS data very well (L2=8600 on df=69, εa=0.087). The relaxation of the factor loadings, so only the configuration of one factor is required, fits better (L2=8579 on df=64) but is not considered a good fit relative to the increased number of parameters (εa=0.090) or in the change in fit (χ2=21 on df=5). When specific covariances are added to the original metric invariant model, following McArdle & Nesselroade (1994), the fit of the one factor model is still not within the acceptable limits (i.e., εa=0.066 > 0.050). In contrast, the two factor model drawn in Figure 5 represents a good fit to the two occasion data no matter how it is constrained. This is true of the original metric invariant model (εa=0.050) and, especially, the two factor model with specific covariances (εa=0.023). These longitudinal results strongly suggest we redo the prior latent curve analysis with two functions rather than one.

Table 6.

Fit indices for 1 and 2 common factors based on six measures at two longitudinal occasions

| 6a: F=1 models | χ2 | df | Dχ2 /Ddf | ea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invariant Λ, Ψ2 | 8600 | 69 | .087 | |

| Configural Λ | 8579 | 64 | 21 / 5 | .090 |

| MI + Specifics Covariance | 4534 | 63 | 4056 / 6 | .066 |

| 6b: F=2SS models | ||||

| Invariant Λ, Ψ2 | 2579 | 63 | .050 | |

| Configural Λ | 2578 | 59 | 1 / 4 | .051 |

| MI + Specifics Covariance | 423 | 57 | 2156 / 6 | .023 |

Note: Model Comparisons from Likelihood Based Goodness-of-Fit Indices

The path model of Figure 7 can now easily be extended to multiple time points (see McArdle et al., 2007), but it is not the only useful organization of these data. For example, we can rewrite a factor model with a simple set of latent difference scores (Δf = f[2]-f[1]) as depicted in Figure 3. This final model suggests the changes in the observed scores can be assessed in three parts – (a) the differences in the loadings over time (Λ[2]-Λ[1]) multiplied by the initial common factor score (f[1]), (b) the loadings at time 2 multiplied by the differences in the factor scores (Δf), and (c) the differences in the unique factors (Δu). It is most interesting that this difference score form does not alter the interpretation or statistical testing of factor invariance over time. If the factor loadings are invariant over time (Λ[2]=Λ[1]), then the first term in the model drops out and the result is simplified (i.e., ΔY = Λ Δf + Δu). This result is practically useful -- If the loadings are invariant over time, the factor pattern between occasions equals the factor pattern within occasions. When metric invariance is not a required result, the differences in the between and within factor loadings may be meaningful. This basic result for difference scores is consistent with previous multivariate work on this topic (e.g., 1970, Nesselroade & Cable, 1974).

5: Modeling Individual Dynamic Influences

A final challenge is raised here by common questions about longitudinal -- “What is the best change model for my data?” This is related to another challenging question – “Do any of my constucts lead to changes in the other constructs?” This implies we can and should write and fit a set of equations with changes in multiple variables (McArdle, et al., 2001). It is important to consider that these kinds of questions are very common in developmental theory, but answers are not yet very common in empirical practice.

The fundamental idea used here is that all change models have, as their basis, the change score as an outcome, and SEMs allow for some accounting for the errors-of measurement or unique components. Thus, some practical answers to these theoretical questions start with a more basic question -- Is there any reasonable way to relate the change score equation [1] to the multilevel model [2] and [3]? A straightforward answer to this question comes from rewriting the first level equation [2] for two consecutive observations (Y[t] and Y[t+1]) as

| [9] |

so it is clear that the difference between two time points is essentially two parts: (1) the individual slope (g1) multiplied by the group differences in the basis (A[t]-A[t+1]), and (2) the individual changes in the error terms. The greek term (Δ) is used to designate the application of the difference operator to unobserved or latent variables.

This equation also implies that the changes in the latent scores can be written as the prediction of the slopes (as in [3b]). It is worth noting that seminal statements made by some of the most important leaders in quantative methods strongly advocated that we need to avoid change scores (e.g., Cronbach & Furby 1970, Lord 1958). These statements focused primarily on the very real problems of measurement error in the change scores (the second component). In contrast, other researchers who investigated these statistical issues emphasized the benefits of using change scores (i.e., Allison 1990, Nesselroade & Cable 1974; Rogosa & Willett, 1983) because of the first terms. It is not surprising that the appropriate use of change scores remains a conundrum for many researchers, but it may be suprising that the multilevel model avoids this problem by focusing on the slope components (g1).

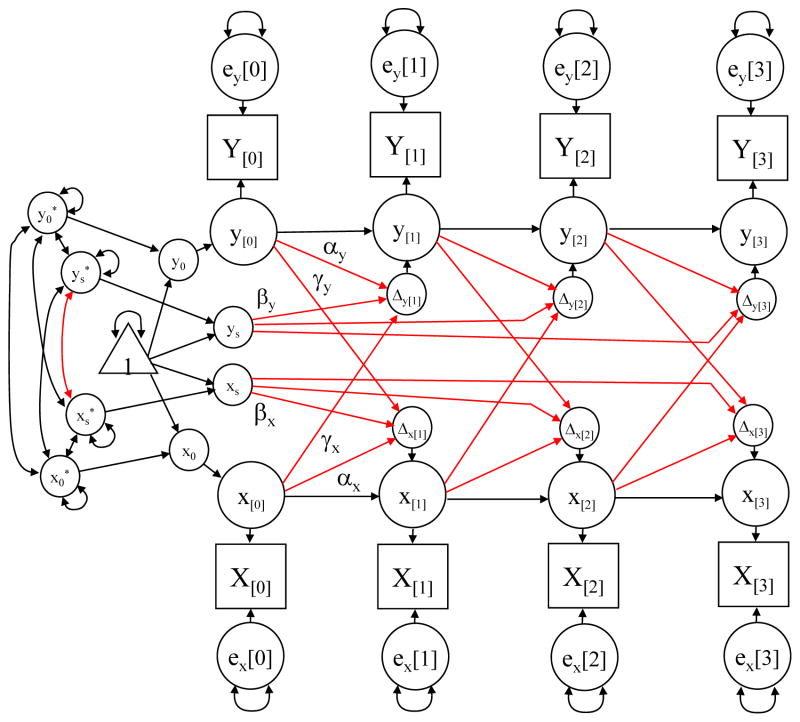

This simple latent variable difference score approach leads to a wide variety of possibilities we can consider under the term dynamic-structural analysis (see McArdle, 1988; 2001). On a formal basis, we first assume we have observed scores Y[t] and Y[t−1] measured over a defined interval of time (Δt), but we assume the latent variables are defined over an equal interval of time (Δt=1). This definition of an equal interval latent time scale is non-trivial because it allows us to eliminate Δt from the rest of the equations. That is, in any model we can write

| [10] |

with latent scores y[t] and y[t−1], residual scores e[t], possibly representing measurement error, and latent difference scores Δy[t]. Even though this difference Δy[t] is a theoretical score and not simply a fixed a linear combination, we can write a structural model for any latent change concept without directly writing the resulting complex trajectory (as in McArdle & Nesselroade, 1994; McArdle, 2001; McArdle & Hamagami, 2001) as

| [11] |

This simple algebraic device [10] allows us to generally define the trajectory equation based on a summation (Σ i=1, t) or accumulation of the latent changes (Δy[t]) up to time t, and these structural expectations are automatically generated using any standard SEM software (e.g., LISREL, Mplus, Mx, etc.).

This approach makes it possible to consider any change model, including one where

| [12] |

where the g1 is (as in equation [2]) a latent slope score which is constant over time, and the α and β are coefficients describe the change. This dual change model combines an additive change parameter (α) with a multiplicative change parameter (β; see McArdle, 2001).

In general these dynamic coefficients (α and β) are not all required to be invariant over time, and a family of more complex curves can result from fitting non-invariant coefficients (α[t] and/or β[t]) or adding stochastic disturbance terms (z[t]). However, if the residual components of the latent change are not included, the expectations describe a more restricted set of latent curves which are required to be deterministic and smooth over time. This deterministic approach will be used to compare groups in the analyses presented here. The latent difference score approach is most useful when we start to examine time-dependent inter-relationships among multiple growth processes. As a final alternative model we use an expansion of our previous latent difference scores logic to write a bivariate dynamic change score model as

| [13] |

| [14] |

In this model each change is represented by dual changes (parameters α and β) but also include coupling parameters (γ). The coupling parameter (γyx) represents the time-dependent effect of latent x[t] on y[t], and the other coupling parameter (γxy) represents the time-dependent effect of latent y[t] on x[t].

This bivariate dynamic model is described in the path diagram of Figure 8. The key features of this model include the used of fixed unit values (unlabeled arrows) to define Δy[t] and Δx[t], and equality constraints within a variable (for the α, β, and γ parameters) to simplify estimation and identification. These latent difference score models can lead to more complex nonlinear trajectory equations (e.g., non-homogeneous equations). These trajectories can be described by writing the implied basis coefficients (Aj[t]) as the linear accumulation of first differences for each variable (Σ Δy[j], j=0 to t). Additional unique covariances within occasions (uy[t] ux[t]) are possible, but these will be identifiable only when there are multiple (M>2) measured variables within each occasion.

Figure 8.

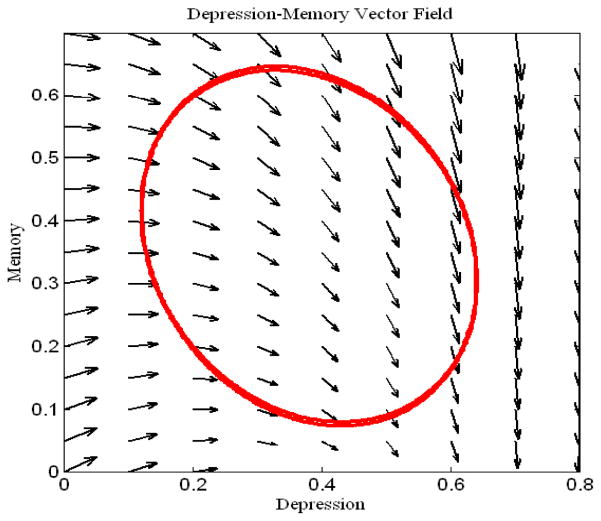

Bivariate change expectations (vector field) for directional dynamic where Depression→Memory (from McArdle, Hamagami, Fisher & Kadlec, 2009)

There are now numerous practical examples of this kind of bivariate dynamic model (e.g., McArdle et al, 2004; Ferrer & McArdle, 2004; Ghisletta & Lindenberger, 2005; Orth et al., 2008). In this HRS example lets us consider testing some hypotheses about the joint impacts of memory loss and increases in depression in the elderly in the HRS (Note: Depression in the HRS is measured by an abbreviated from of the CES-D, with higher scores indicateing more depression; see McArdle, Hamagami, Kadlec & Fisher, 2009). In this specific case of the HRS data, we fit a model and we estimate the change equations of Table 7a. Of most interest here is the episodic memory factor (EM[t]) where the resulting equations are

Table 7.

Results from Alternative Dynamic Models applied to HRS data

| 7a: Selected HRS Bivariate dynamic results | |

|---|---|

| Dynamic equations for Memory-Status coupling

| |

| Dynamic equations for Status-Depression coupling

| |

| Dynamic equations for Memory-Depression coupling

|

| 7b: Alternative Model Fits | Likelihood (Deviance) L2 | Number of Parameters | Difference dL2~ χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full BDCS Model | −35831 | 20 | -- |

| Remove Coupling from Depression →Status | −35786 | 19 | 45 |

| Remove Coupling from Status → Depression | −35832 | 19 | 1 |

| No Coupling | −35764 | 18 | 67 |

| [15] |

| [16] |

From a cursory look at these parameters it is clear that the coefficient of depression → Δ memory (−1.54) is large and negative while the coefficent of memory→Δ depression is small (0.13). However, these parameters are highly dependent upon one another, as well as the different scales of measurement, so the appropriate way to check on the need for a dynamic influence is to try to eliminate it and check the loss in fit (as in McArdle et al., 2001). The results of this approach are listed in detail in Table 7b. Basically, when we fit a model without the influence of memory on depression, the model fits fairly well (χ2=1 on df=1). But when we use the same procedure but eliminate the influence of depression on memory the model does not fit well (χ2=45 on df=1). The net result of this dynamic analysis is that we find that increases or decreases in depression[t−1]→Δ memory[1] and not the other way around.

The results of these models ([15] and [16]) cannot be expressed in terms of a simple set of univarate trajectories (as in Figure 1) but it can be expressed as a set of bivariate expectations, or a vector field (Boker & McArdle, 2005), and the expected values from these parameters are these are displayed in Figure 8 (from Equations [15] and [16]). This plot is useful because it shows the expected direction of any pair of coordinates from any starting point (y[t], x[t]), and the ellipse gives the symmetric 95% confidence boundary around the actual data (at t=0). The directional arrows are a way to display the expected pair of Δt=1 visit changes (Δy, Δx) from this point. This figure shows an interesting dynamic property --- the change expectations of a dynamic model depend on the starting point. From this perspective, we can also interpret the high level-level correlation, which describes the placement of the individuals in the vector field, and the negative slope-slope correlation, which describes the location of the subsequent change scores for individuals in the vector field. The resulting “flow surface” for the shows the state of depression abilities has a tendency to impact score changes on the memory scores Needless to say, these dynamic impacts are not easy to see in the typical comparison of changes in the means over time.

Future Steps

This chapter has dealt with some contemporary issues for longitudinal data analysis. In all cases discussed here the hope is that these issues will be raised rather than ignored because there is a great deal of potential to learn from our longitudinal data. For example, in terms of the HRS longitudinal data we have learned: (1) The mixed-effects multi-level latent curve model is a clear way to separate individual changes from group differences. (2) The use of an age-basis rather than a time-basis may be useful with cognitive measures. (3) The age-based curve is probably nonlinear, with more decline in cognition after age 75. (4) The cognitive measures do not represent a single function, and at least two factors of cognition may be needed to measure the individual changes. (5) The dynamic influences of variables such as depression have strong impacts on the decline of memory abilities. These fundamental observations about the longitudinal HRS data could not have been made before these specific issues were considered. Of course, not all issues have yet been met, but at least the basic issues are now clearer.

We have not fully focused on several basic measurement assumptions of all latent curve models -- longitudinal measurement equivalence – i.e., the same unidimensional attribute is measured on the same persons using exactly the same scale of measurement at every occasion. One key question of: “Is the scale of measurement the same at all levels of Y?” Cattell (1966) nicely illustrated this problem in his tour-de-force on scaling issues in multivariate analysis. “This diagram shows the transformation between raw scores values in the upper row to what is known to be the true scale scores in the lower row. (A slight difference in the lower raw score means a lot, while equivalent differences at the top do not correspond to much real increase.) It will be seen that the rank order of three people in difference scores calculated in raw scores is exactly the opposite to that from scaled scores. Such complete reversal is, of course, an extreme instance.” (Cattell, 1966, p.366). Of course, since the definition of true scores can not be made without some manifest observations, it is not actually known how much these kinds of extreme difference scores do exist. A great deal of work in the history of psychometrics has been used to help develop improved scales to avoid these problems in an objective/empirical fashion. One outstanding and successful effort made about this problem comes from the work of Rasch (see McArdle et al., 2009).

Factorial invariance, especially factor-loading invariance, was considered as a major requirement for any longitudinal analysis. As presented here, the goal of measurement invariance needs to be achieved before we can consider any SEMs of latent changes. Although only scale-level data are considered here, practical problems with measurement invariance at the scale level may indicate more basic measurement problems at the item level (McDonald 1985). Using incomplete data principles, item invariance is possible even if the items are originally used in the context of different scales (McArdle et al., 2002; McArdle & Nesselroade, 2003; Grimm & McArdle, 2007). There are many techniques for linkage across measurement scales with sparse longitudinal data, and invariant item-response models may be very useful for these purposes (McArdle, Grimm, Hamagami, Bowles & Meredith, 2009).

New forms of multiple group and incomplete data approaches can be used with the dynamic models described here. By using a multilevel approach, we can also effectively analyze cases in which each person has different amounts of longitudinal data (i.e., unbalanced data or incomplete data), and some of the new SEM programs make this an easy task. These possibilities lead directly to the revival of practical experimental options based on incomplete data (e.g., McArdle & Woodcock 1997). Incomplete data models have also been used to describe the potential benefits of a mixture of age-based and time-based models using only two time points of data collection---an accelerated longitudinal design (Duncan et al. 2006, McArdle & Bell 2000).

There are also many other elegant statistical models for longitudinal data. Several important breakthroughs in work on dynamic modeling of continuous time data have been made using SEM software (e.g., Boker 2001; Chow et al. 2007; Montfort et al. 2007; Oud & Jansen 2000). These differential equations models offer many more dynamic possibilities, and this is increasingly important when large amounts of time points of data are collected (T > N). Other repeated-measures SEMs are based on the logic of partitioning variance components across multiple modalities (Kenny & Zautra 2001, Steyer et al. 2001). These models decompose factorial influences into orthogonal common and specific components, with an emphasis on separating trait factors from state factors. These models have interesting interpretations, and they may be useful when combined with other SEMs described here.

We have also not examined classic issues from other the problems of scaling, group differences, lack of measurement the invariance of constructs, and the appropriate selection of an optimal time-lag between changing longitudinal measurements. There are also many newer techniques that explore similar issues (Hedecker & Gibbons 2006, Muller & Stewart 2006, Singer & Willett 2003, Verbeke & Molenberghs 2000, Walls & Schafer 2006). The many good general references to the structural equation modeling approach (SEM; e.g., Kline 2005, McDonald 1985; Muthen & Muthern, 2006) include several new books specifically about SEM for repeated measures (e.g., Bollen & Curran 2006, Duncan et al. 2006). The general longitudinal approach has gained popularity, and for the most part, it nicely matches the scientific goals of longitudinal research (Nesselroade & Baltes 1979).

So there is much to be learned from these and other issues of longitudinal data analysis. Researchers who dig in and attack any of these issues are likely to come to different conclusions about their own longitudinal data, and this is as it should be. It is also certain that solving one of these problems is likely to create other problems, and more work will be inevitable. Neither longitudinal panel collection or longitudinal panel analysis should be thought of as simple or easy. However, there is simply no reason to do the very hard work of collecting panel data if the subsequent panel analyses does not attempt to match these efforts. The real challenge for aspiring panel researchers is to try to deal these classic problems in measurement of change so we can move on to newer and hopefully more informative issues.

Figure 4.

Figure 4a: Expected HRS Cognition Scores over AGE at Testing

Figure 4b. Nonlinear Changes in HRS Cognition Scores over AGE of Measurement

Table 2.

Alternative mixed-effect linear latent growth models for the longitudinal HRS Cognition Scores (individual N=10,498 with data points Nd=25,029)

| Estimates from Alternative Latent Growth Models | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Parameters & Fits | 2a: No Change Baseline (NCS) | 2b: Linear Change based on Wave (LCW) | 2c: Linear Change based on Date (LCD) | 2d: Linear Change based on Age (LCA) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Base | +Drop | Base | +Drop | Base | +Drop | Base | +Drop | |

|

| ||||||||

| Fixed (Group) Parameters | ||||||||

| Age 75 Mean μ0 | 60.2 | 60.8 | 60.5 | 62.1 | 61.2 | 61.8 | 59.8 | 60.7 |

| 1-year Slope Mean μs | -- | -- | −.09 | −1.6 | −1.4 | −1.5 | −.83 | −.81 |

|

| ||||||||

| Dropout on Intercept βo | -- | +3.6 | -- | −5.0 | -- | −13.4 | -- | −6.3 |

|

| ||||||||

| Dropout on Slope βs | -- | -- | -- | ne | -- | +3.5 | -- | −.25 |

| Random Parameters | ||||||||

| Age 75 Variance σ02 | 177.7 | 176.4 | 199.3 | 182.0 | 186.0 | 182.6 | 131.3 | 127.2 |

| 1-year Slope Variance σs2 | -- | -- | 1.4 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 1.2 | 0.23 | 0.24 |

| Level-Slope Correlation ρ0s | -- | -- | −.30 | −.11 | −.13 | −.22 | .27 | .25 |

| Error Variance σe2 | 79.3 | 79.2 | 72.5 | 67.3 | 71.2 | 67.9 | 78.7 | 74.2 |

|

| ||||||||

| Goodness-of-Fit | ||||||||

| Overall Likelihood / parms | 10748 / 3 | 10662 / 5 | 10404 / 6 | 9844/ 8 | 9995 / 6 | 9804 / 8 | 7879/ 6 | 7707 / 8 |

| Random as Baseline χ2 / df | 11337 / 1 | 10494 / 4 | 10903 / 2 | 12919 / 5 | ||||

| No Change as Baseline χ2 / df | 0 / 0 | −843 / 3 | −434 / 1 | 1582 / 4 | ||||

Notes: (1) The number of participants N=10,498 and the number of data points Nd=25,029; (2) The parameters for Wave are centered at Wave[t]=1, those for Date are centered at Date[t]==1993, and Age is centered at Age[t]=75; (3) Parameters are maximum likelihood estimates from minimizing the likelihood function f=−2ll of the raw data using the SAS PROC MIXED program with HRS survey weights for the individuals; (4) The random baseline likelihood for the HRS PerCog variable is f=210898 with μ0=60.8 and σe2=257.4, so likelihoods are listed as −2ll-190000; (5) All parameters are significant at the α=.001 level unless there is an “ns” indicator, the ‘=‘ indicates a fixed parameter, the ‘ne’ indicates a parameter that could not be estimated.

Table 3.

Alternative LINEAR and NON-LINEAR mixed-effect /latent growth models for the longitudinal HRS Cognition Scores (individual N=10,498 with data points Nd=25,029)

| Estimates from Alternative Latent Curve Models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Parameters & Fits | 3a: Linear Change Based on Age per Decade (LCA) | 3b: Quadratic Change Based on Age (QCA) | 3c: Cubic Change Based on Age (CCA) | 3d: Two Part Spline Change Based on Age (SCA) |

| Fixed Parameters | ||||

| Age 75 Mean μ0 | 59.8 | 60.4 | 60.3 | 60.6 |

| Slope 1 Mean μ1 | −8.3 | −8.1 | −7.5 | −6.9 |

| Slope 2 Mean μ2 | -- | −1.2 | −0.91 | −9.5 |

| Slope 3 Mean μ3 | -- | -- | −0.49 | -- |

|

| ||||

| Random Parameters | ||||

| Age 75 Var. σ02 | 131.3 | 130.9 | 130.9 | 170.5 |

| Slope 1 Var. σ12 | 23.4 | 24.3 | 25.1 | 71.4 |

| Slope 2 Var. σ22 | -- | ne | ne | 94.7 |

| Slope 3 Var. σ32 | -- | -- | ne | -- |

| Correlation ρ0,s1 | .27 | .26 | .26 | .58 |

| Correlation ρ0,s2 | -- | ne | ne | −.26 |

| Correlation ρs1,s2 | -- | ne | ne | 1.00b |

| Error Variance σe2 | 78.7 | 78.4 | 78.2 | 74.6 |

|

| ||||

| Goodness-of-Fit | ||||

| Overall Likelihood / parms | 7879 / 7 | 7926 / 10 | 7915 / 12 | 7826 / 10 |

| Random as Baseline χ2 / df | 13019 /2 | 12972 /8 | 12983 /10 | 13072 / 6 |

| No Change as Baseline χ2 / df | 1682 /3 | 1635 / 7 | 1646 / 9 | 1735 / 7 |

| Sequential as Baseline χ2 / df | -- | vs. linear 47 / 4 | vs. Quadratic 11/ 2 | vs. Linear 53 / 3 |

Notes:

(1) The number of subjects N=10,498 and the number of data points Nd=25,029; (2) The parameters for Age are centered at Age[t]=75 and scaled by Δt=10 years – i.e., per decade change – and the two part spline is centered at Age[t]=75 as well; (3) Parameters are maximum likelihood estimates from minimizing the likelihood function f=−2ll of the raw data using the SAS PROC MIXED program with HRS survey weights for the individuals; (4) The random baseline likelihood for the HRS cognitive ability (CA[t]) variable is f=210898 with μ0=60.8 and σe2=257.4; (5) All parameters are significant at the α=.001 level unless there is an “ns” indicator, the ‘=‘ indicates a fixed parameter, the ‘ne’ indicates a parameter that could not be estimated; (6) Boundary indicated by “b”.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a MERIT award from the National Institute on Aging; Number AG07137).

Footnotes

Presented at: The ZiF Scientific Meeting, Bielefeld, April 2010

References

- Allison PD. Change scores as dependent variables in regression analysis. In: Clogg CC, editor. Sociological Methodology 1990. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1990. pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Baltagi B. Econometric Analysis of Panel Data. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Learning in adulthood: The role of intelligence. In: Klausmeier HJ, Harris CW, editors. Analyses of concept learning. New York: Academic Press; 1966. pp. 117–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K, Curran PJ. Latent curve models: A structural equation perspective. NY: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boker SM. Differential structural equation modeling of intra-individual variability. In: Collins L, Sayer A, editors. New Methods for the Analysis of Change. Washington, DC: APA Press; 2001. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Boker S, McArdle JJ. Vector field plots. In: Armitage P, Colton P, editors. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. 2. 8. Chichester, England: John Wiley; 2005. pp. 5700–5704. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cagney KA, Lauderdale DS. Education, wealth and cognitive function in later life. Journal of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57B:P163–P172. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.2.p163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattell RB. The Handbook of Multivariate Experimental Psychology. New York: Macmillian; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Chow S-M, Ferrer E, Nesselroade JR. An unscented Kalman filter approach for the estimation of nonlinear dynamic systems models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42(2):283–321. doi: 10.1080/00273170701360423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnaan A, Laird NM, Slasor P. Using the general linear mixed model to analyze unbalanced repeated measures and longitudinal data. Statistics in Medicine. 1997;16:2349–2380. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971030)16:20<2349::aid-sim667>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudeck R, Klebe KJ. Multiphase mixed-effects models for repeated measures data. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):41–62. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ, Furby L. How we should measure change—or should we? Psychological Bulletin. 1970;74:68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Collins L, Sayer A, editors. New Methods for the Analysis of Change. Washington, DC: APA Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cudeck R, Harring JR. Analysis of nonlinear patterns of change with random coefficient models. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:615–637. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggle PJ, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. New York: Oxford Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA, Li F. An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer E, Hamagami F, McArdle JJ. Modeling latent growth curves with incomplete data using different types of structural equation modeling and multilevel software. Structural Equation Modeling. 2004;11(3):452–483. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer E, McArdle JJ. An experimental analysis of dynamic hypotheses about cognitive abilities and achievement from childhood to early adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:935–952. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman VA, Aykan H, Martin LG. Another look at aggregate changes in severe cognitive impairment: Cumulative effects of three survey design issues. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57B:S126–S131. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.2.s126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghisletta P, Lindenberger U. Exploring the structural dynamics of the link between sensory and cognitive functioning in old age: Longitudinal evidence from the Berlin Aging Study. Intelligence. 2005;33:555–587. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm KJ, Hamagami F, McArdle JJ. Nonlinear growth models in research on cognitive aging. In: Montfort Kv, Oud H, Satorra A., editors. Longitudinal models in the behavioural and related sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 267–294. [Google Scholar]

- Hamagami F, McArdle JJ. Advanced studies of individual differences linear dynamic models for longitudinal data analysis. In: Marcoulides G, Schumacker R, editors. New developments and techniques in structural equations modeling. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 203–246. [Google Scholar]

- Hamagami F, McArdle JJ. Dynamic extensions of latent difference score models. In: Boker SM, Wegner ML, editors. Quantitative Methods in Contemporary Psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 47–85. [Google Scholar]

- Harris CW, editor. Problems in measuring change. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hedecker D, Gibbons R. Longitudinal data analysis. NY: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog AR, Wallace RB. Measures of cognitive functioning in the AHEAD study [Special Issue] Journal of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1997;52B:37–48. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.special_issue.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn JL. State, trait, and change dimensions of intelligence. The British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 1972;42(2):159–185. [Google Scholar]

- Horn JL, McArdle JJ. Understanding human intelligence since Spearman. In: Cudeck R, MacCallum R, editors. Factor Analysis at 100 years. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2007. pp. 205–247. [Google Scholar]

- Horn JL, McArdle JJ. Perspectives on Mathematical and Statistical Model Building (MASMOB) in Research on Aging. In: Poon L, editor. Aging in the 1980’s: Psychological Issues. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1980. pp. 503–541. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao C. Analysis of Panel Data. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. Advances in factor analysis and structural equation models. Cambridge, MA: Abt Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Juster FT, Suzman R. An overview of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Human Resources. 1995;30(Suppl 1995):S7–S56. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Zautra A. The trait-state model for longitudinal data. In: Collins L, Sayer A, editors. New Methods for the Analysis of Change. Washington, DC: APA Press; 2001. pp. 241–264. [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. Principles and Practices in Structural Equation Modeling. NY: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD, Schabenberger O. SAS system for mixed models. 2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA. Modeling the dropout mechanism in repeated-measures studies. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995;90:1112–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Lord F. Further problems in the measurement of growth. Educational & Psychological Measurement. 1958;18:437–454. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. Latent variable growth within behavior genetic models. Behavior Genetics. 1986;16(1):163–200. doi: 10.1007/BF01065485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. Structural factor analysis experiments with incomplete data. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1994;29(4):409–454. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2904_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. A latent difference score approach to longitudinal dynamic structural analyses. In: Cudeck R, du Toit S, Sorbom D, editors. Structural Equation Modeling: Present and future. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2001. pp. 342–380. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. Five Steps in the Structural Factor Analysis of Longitudinal Data. In: Cudeck R, MacCallum R, editors. Factor Analysis at 100 years. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2007. pp. 99–130. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. Latent variable modeling of differences and changes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;60 doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Anderson E. Latent variable growth models for research on aging. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. The handbook of the psychology of aging. New York: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Bell RQ. An introduction to latent growth curve models for developmental data analysis. In: Little TD, Schnabel KU, Baumert J, editors. Modeling longitudinal and multiple-group data: practical issues, applied approaches, and scientific examples. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 69–107. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Ferrer-Caja E, Hamagami F, Woodcock RW. Comparative longitudinal multilevel structural analyses of the growth and decline of multiple intellectual abilities over the life-span. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(1):115–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Fisher GG, Kadlec KM. Latent Variable Analysis of Age Trends in Tests of Cognitive Ability in the Health and Retirement Survey, 1992–2004. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22(3):525–545. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Hamagami F. Linear dynamic analyses of incomplete longitudinal data. In: Collins L, Sayer A, editors. Methods for the Analysis of Change. Washington, DC: APA Press; 2001. pp. 137–176. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Hamagami F. Multilevel models from a multiple group structural equation perspective. In: Marcoulides G, Schumacker R, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 89–124. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Hamagami F, Jones K, Jolesz F, Kikinis R, Spiro A, Albert MS. Structural modeling of dynamic changes in memory and brain structure using longitudinal data from the normative aging study. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2004;59B(6):P294–P304. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.6.p294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Hamagami F, Meredith W, Bradway KP. Modeling the dynamic hypotheses of Gf-Gc theory using longitudinal life-span data. Learning and Individual Differences. 2001;12(2000):53–79. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Hamagami F, Kadlec K, Fisher G. Unpublished Manuscript. Department of Psychology, University of Southern California; 2009. A dynamic structural analysis of dyadic cycles of depression in the Health and Retirement Study data. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Grimm K, Hamagami F, Bowles R, Meredith W. A dynamic structural equation analysis of vocabulary abilities over the life-span. Psychological Methods. 2009 doi: 10.1037/a0015857. in Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Nesselroade JR. Growth curve analyses in contemporary psychological research. In: Schinka J, Velicer W, editors. Comprehensive Handbook of Psychology, Volume Two: Research Methods in Psychology. New York: Pergamon Press; 2003. pp. 447–480. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Nesselroade JR. Structuring data to study development and change. In: Cohen SH, Reese HW, editors. Life-Span Developmental Psychology: Methodological Innovations. Hillsdale, N.J: Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 223–267. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Small BJ, Backman L, Fratiglioni L. Longitudinal models of growth and survival applied to the early detection of Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2005;18(4):234–241. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Wang L. Modeling Age-Based Turning Points in Longitudinal Life-Span Growth Curves of Cognition. In: Cudeck R, Cohen P, editors. Turning Points Research. Mahwah, Erlbaum: In press. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Woodcock JR. Expanding test-rest designs to include developmental time-lag components. Psychological Methods. 1997;2(4):403–435. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP. Factor Analysis and Related Methods. Hillsdale, N.J: Erlbaum; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W, Horn JL. The role of factorial invariance in measuring growth and change. In: Collins L, Sayer A, editors. New Methods for the Analysis of Change. Washington, DC: APA; 2001. pp. 201–240. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W, Tisak J. Latent curve analysis. Psychometrika. 1990;55:107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki Y, Raudenbush SW. Tests for linkage of multiple cohorts in an accelerated longitudinal design. Psychological Methods. 2000;5(1):24–63. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.5.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montfort K, Oud H, Satorra A, editors. Longitudinal models in the behavioural and related sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Muller KE, Stewart PW. Linear model theory. NY: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus, the comprehensive modeling program for applied researchers: 4thEdition user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nesselroade JR, Baltes PB, editors. Longitudinal research in the study of behavior and development. New York: Academic Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Nesselroade JR, Cable DG. Sometimes it’s okay to factor difference scores - The separation of state and trait anxiety. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1974;9:273–282. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr0903_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Berking M, Walker N, Meier LL, Znoj H. Forgiveness and psychological adjustment following interpersonal transgressions: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008;42:365–385. [Google Scholar]

- Oud JHL, Jansen RARG. Continuous time state space modeling of panel data by means of SEM. Psychometrika. 2000;65:199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers WL, Ofstedal MB, Herzog AR. Trends in scores on tests of cognitive ability in the elderly U.S. population, 1993–2000. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003;58B:S338–S346. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.s338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogosa D. Causal models in longitudinal research: Rationale, formulation, and interpretation. In: Nesselroade JR, Baltes PB, editors. Longitudinal research in the study of behavior and development. New York: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 263–302. [Google Scholar]

- Rogosa D, Willett Demonstrating the reliability of the difference score in the measurement of change. Journal of Educational Measurement. 1983;20(4):335–343. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett J. Applied longitudinal data analysis. NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Steyer R, Partchev I, Shanahan MJ. Modeling true intraindividual change in structural equation models: The case of poverty and children’s psychological adjustment. In: Little TD, Schnabel KU, Baumert J, editors. Modeling longitudinal and multiple-group data: practical issues, applied approaches, and scientific examples. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Walls TA, Schafer JL. Models of intensive longitudinal data. NY: Oxford U. Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, McArdle JJ. Structural Equation Modeling 2008 [Google Scholar]