Graphical abstract

Keywords: G. glabra, G. inflata, G. uralensis, Glycyrrhizin, Licorice, ROESY

Abstract

Glycyrrhiza glabra, commonly known as licorice, is a popular herbal supplement used for the treatment of chronic inflammatory conditions and as sweetener in the food industry. This species contains a myriad of phytochemicals including the major saponin glycoside glycyrrhizin (G) of Glycyrrhetinic acid (GA) aglycone. In this study, 2D-ROESY NMR technique was successfully applied for distinguishing 18α and 18β glycyrrhetinic acid (GA). ROESY spectra acquired from G. glabra, Glycyrrhiza uralensis and Glycyrrhiza inflata crude extracts revealed the presence of G in its β-form. Anti-inflammatory activity of four Glycyrrhiza species, G, glabra, G. uralensis, G. inflata, and G. echinata roots was assessed against COX-1 inhibition revealing that phenolics rather than glycyrrhizin are biologically active in this assay. G. inflata exhibits a strong cytotoxic effect against PC3 and HT29 cells lines, whereas other species are inactive. This study presents an effective NMR method for G isomer assignment in licorice extracts that does not require any preliminary chromatography or any other purification step.

Introduction

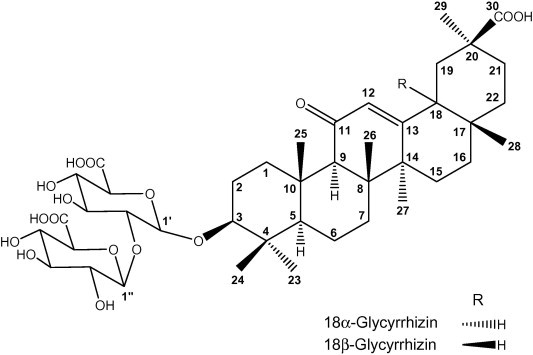

Licorice is the dried root of Glycyrrhiza glabra, Glycyrrhiza inflata or Glycyrrhiza uralensis, a member of legumes endogenous to Asia and southern Europe; widely used as flavoring and sweetening agent and also proposed for various clinical applications. Pharmacological effects of licorice include inhibition of gastric acid secretion, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and anti-atherogenic have been well verified [1,2]. An anti-carcinogenic effect of licorice has also recently been demonstrated [3–5]. These biological effects are attributed to a myriad of biologically active constituents: terpenoids, alkaloids, polysaccharides, polyamines, saponins, and flavonoids [6–8]. The most important constituent of licorice is glycyrrhizin (G, 3-O-(2-O-β-d-glucopyranuronosyl-α-d-glucopyranuronosyl)-3β-hydroxy-11-oxo-18,20-olean-12-en-29-oic acid) present in quantities of 3.6–13.1% in dried roots [9]. G consists of a disaccharide of two glucuronic acid molecules bound to the pentacyclic triterpene glycyrrhetinic acid (GA), which exists in two isomers (C-18 epimers): the trans (α GA) and the cis form (β GA) (Fig. 1). G exhibits potent hydrocortisone-like anti-inflammatory, antiulcer, antiviral, and antihepatotoxic activities [10,11] whereas GA is a potent antibiotic against ulcer causing Helicobacter pylori [12].

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of α- and β-glycyrrhizin. Note the carbon numbering system for each compound is used throughout the manuscript for NMR assignment.

The amount of βGA in licorice root is reported to be in the 0.1–1.6% range, whereas αGA amount is usually lower than 0.7%. Qualitative differences in pharmacological effects between the isomers have been observed: for instance, the antihepatotoxic activity of αGA is higher than that of βGA, while its anti-inflammatory activity is considerably lower [9].

In regard to quality control (QC) analysis of licorice roots, Glycyrrhizin (G) is often considered as the most frequently monitored metabolite via HPLC. Nevertheless, for HPLC, it is rather difficult to resolve the 18α and 18β stereoisomers satisfactorily due to the very similar properties of these epimers. Only a few papers report procedures to distinguish α-GA and β-GA, using chiral separation, HPTLC and gel electrophoresis [13,14], which all require elaborate chromatography for a separation of the isomers. Interest in both G biological activity and improving QC analysis of licorice samples, drives the development of faster, stable and accurate methods for reliable G isomer assignment in licorice extracts.

NMR presents a powerful technology for isolates structural elucidation including conformational NMR experiments based on either 2D nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY) or rotating frame Overhauser effect spectroscopy (ROESY) which provide information about couplings through space and consequently can allow for a configuration (and sometimes even conformation) assignments of isomers [15]. With an increasing interest in utilizing NMR for metabolic fingerprinting and phytomedicines QC analysis, it is now possible to record NMR spectra from crude plant extracts providing the valuable metabolite signature of a complex plant extract [16]. Unlike MS-based analyses, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides a large amount of information regarding molecular structure, and novel software innovations have facilitated the unequivocal identification of compounds within composite samples. However, NMR has a lower sensitivity compared to MS. Additionally, introducing another set of chemical shifts from the proton dimension as in ROESY spectra would also complicate the spectral processing using multivariate data analysis.

In this study, we present an effective NMR method for G isomer assignment in licorice extracts that does not require any preliminary chromatography or any other purification step. A total of 8 extracts representing three different Glycyrrhiza species (G. glabra, G. uralensis and G. inflata) from different localities were analyzed.

Material and methods

Plant materials and chemicals

A total of 8 well-characterized Glycyrrhiza samples representing a broad geographic and genetic sampling of species across the world were analyzed. All information on collected samples and their origin is recorded in (Table 1).

Table 1.

The origin of Glycyrrhiza root samples used in this analysis.

| Accession | Species | Original source | Collected year |

|---|---|---|---|

| GI | G. inflata | China, Xinjiang | 2005 |

| GG1 | G. glabra | Sekem Commercial product, Egypt | 2009 |

| GG2 | G. glabra | Afghanistan | 2008 |

| GG3 | G. glabra | Botanical garden, Cairo University, Egypt | 2009 |

| GG4 | G. glabra | Syria | 2008 |

| GU1 | G. uralensis | China, eastern Inner Mongolia | 2000 |

| GU2 | G. uralensis | China, Gansu | 2002 |

| GU3 | G. uralensis | Commercial, Dongbei-Gancao, Vietnam | 2009 |

Methanol-D4 (99.80% D) was purchased from Deutero GmbH (Kastellaun, Germany). Standards for β-glycyrrhizin (⩾95%), 18α-glycyrrhetinic acid (⩾99%) and 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (⩾99%) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Plant extraction and NMR measurement

Dried and deep frozen Glycyrrhiza root powder (60 mg) was homogenized with 5 ml 100% MeOH using a Turrax mixer (11,000 RPM) for five 20 s periods. Extracts were then vortexed vigorously and centrifuged at 3000g for 30 min to remove plant debris. For each root specimen, three biological replicates were provided and extracted in parallel under identical conditions (a total of 24 samples). For ROESY analysis, 4 ml was aliquoted and the solvent was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen till dryness. Dried extracts were resuspended with 800 μl 100% methanol-D4. After centrifugation (13,000g for 1 min), the supernatant was transferred to a 5 mm NMR tube.

All spectra were recorded on a Varian VNMRS 600 NMR spectrometer operating at a proton NMR frequency of 599.83 MHz using a 5 mm inverse detection cryoprobe. 1H NMR spectra were recorded with the following parameters: digital resolution 0.367 Hz/point (32 K complex data points); pulse width (pw) = 3 μs (45°); relaxation delay = 23.7 s; acquisition time = 2.7 s; number of transients = 160. 2D ROESY spectra was recorded using standard CHEMPACK 4.1 pulse sequences (gROESY) implemented in Varian VNMRJ 2.2C spectrometer software. ROESY experiment was conducted with a mixing time set for 300 ms. ROESY spectra were collected over a bandwidth of 6 ppm using 512 and 1024 complex data points in F1 and F2, respectively. Using a 1.31 s relaxation delay resulted in a total acquisition time of 28 min.

Cytotoxicity assay

Human prostate PC3 cancer cell line was obtained from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen, Braunschweig, (DSMZ ACC# 465) and the HT29 colon cancer cell line was obtained from the medical immunology department at Martin Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg (Prof. Seliger). The cells were grown as monolayers in adherent cell lines and were routinely cultured in RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute) 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% l-glutamine in 75 cm2 polystyrene flasks (Corning Life Sciences, UK) and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cells were plated at a density of 1 × 104/well in 96-well plates. They were allowed to attach to the plate for 24 h. After 24 h, the media were replaced with RPMI media containing resin extracts. Three concentrations were used (5, 10, and 20 μg/ml) from each extract. Dried extracts prepared as in section 3.3 were initially dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 2 mg/ml and further diluted with RPMI medium. The DMSO concentration in the assay did not exceed 0.1% and was not cytotoxic to the tumor cells. After 72 h, the medium was taken out, 100 μl of XTT-solution (2,3-bis (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino) carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide) (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) was added to each well, and plates were incubated at 37 °C for another 4 h at a (final concentration 0.3 mg/ml) . Absorbance was measured at 490 nm against a reference wavelength at 650 nm using a microplate reader (Beckman Coulter, DTX 880 Multimode Reader). The mean of triplicate experiments for each dose was used to calculate the IC50 and repeated in 2 passages for each cancer cell line. Digitonin was used as a positive drug control.

Anti-inflammatory cyclooxygenase-1 (COX) inhibition assay

All reagents and solutions were prepared according to the protocols established by Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) for the COX-1 inhibition assay. MeOH extract prepared as above was dissolved in neat DMSO and diluted in reaction buffer to a final DMSO concentration of 1% (v/v). Extracts were tested at a dose of 100, 150 and 200 μg/ml; 3 replicates for each concentration. Reactions were conducted with COX-1 enzyme in the presence of heme as a co-factor. The enzymes were incubated at 37 °C for 15 min with serial dilutions of the liquorice extract or reaction buffer to determine 100% enzyme activity (positive control), and heat inactivated enzymes were used to as negative controls (0% enzyme activity). Arachidonic acid (100 μM) was added to each well and the fluorescence product of the reaction was measured at 670 nm using microplate reader. Percent inhibition of the COX enzymes was determined by comparing the extract loaded wells with the positive and negative controls. Commercially available COX-1 inhibitor (SC-560) (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) with an IC50 value of 100 μM was used as positive reference for comparison.

Total phenolics (TP) quantification

A spectrophotometric method using Folin–Ciocalteau reagent was adapted for TP assays in Glycyrrhiza roots. Extracts were prepared by cold extraction with shaking over 3 h using 100% MeOH. Plant debris was removed by centrifugation and solvent was removed by evaporation under nitrogen followed by lyophilization. The residue was dissolved in methanol to obtain a solution at a concentration of 10 mg/ml. Folin Ciocalteau reagent (100 μl) was added to a test tube containing 20 μl of extract. Contents were mixed and a saturated sodium carbonate solution (200 μl) was added to the tube. The volume was adjusted to 1 ml by the addition of 0.68 ml of milliQ water and contents were mixed vigorously. Tubes were allowed to stand at room temperature for 25 min and then centrifuged for 5 min at 2435g. Absorbance of the supernatant was read at 760 nm. Blank samples of each extract or fraction were used for background subtraction. Caffeic acid was used as standard for the calibration curve at concentrations of 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 5 mg/ml. The assay was carried out in triplicate.

Results and discussion

We have recently reported on the use of 1H NMR for the metabolic fingerprinting of G. glabra, G. uralensis and G. inflata extracts, targeting its secondary metabolites [17]. G (Fig. 1) was identified in these extracts from its well resolved singlet signals at δ 0.82 (Me-28), 0.85 (Me-24), 1.08 (Me-23), 1.13 (Me-25& 26), 1.16 (Me-29) and 1.41 (Me-27), (Fig. 2C). In the sugar region, signals at δ 4.49 d (7.3 Hz) and 4.67 d (7.7 Hz) were assigned to anomeric protons of glucuronic acid moieties at H-1′ and H-1″ position in glycyrrhizin, respectively [17]. For detailed description on extracts chemical composition and glycyrrhizin concentration, see Farag et al. [17]. NMR signals were assigned using a combination of 2D NMR experiments (1H, 1H COSY, HSQC, and HMBC). Nevertheless, utilizing 1D NMR and these 2D-experiments, G isomer conformational assignment could not be successfully confirmed in most licorice extracts, due to crowded 1H NMR spectra with matrix signals which do not allow detection of signals of 18α- or 18β-G.

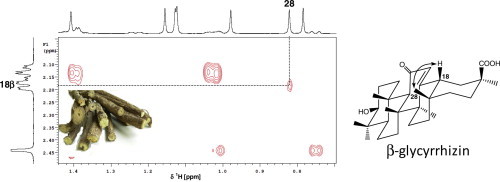

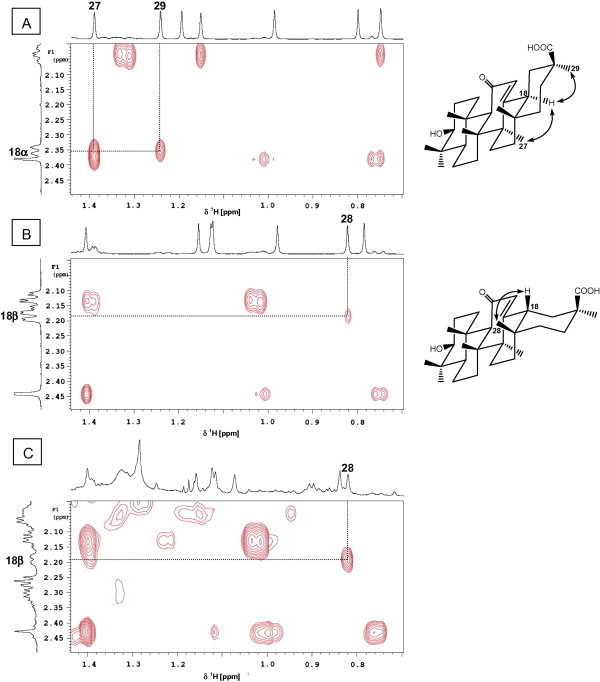

Fig. 2.

Identification of β-glycyrrhizin in G. uralensis crude extract by comparison with the 2D ROESY spectra of α- and β-glycyrrhetic acid. Expansions of 2D ROESY spectra for α-glycyrrhetic acid (A), β-glycyrrhetic acid (B), and G. uralensis extract (C) showing correlations through space between H-18 and CH3-28 in the β-isomers but H-18 and CH3-27 as well as CH3-29 in the α-isomer; arrows point to correlations.

2D (1H–1H) ROESY, a method based on proton-proton dipolar relaxation through space, was considered suitable to distinguish between 18-α and β isomers. ROESY spectra for α- and β-glycyrrhetic acid standard show distinctive crosspeaks between H-18 and its neighboring protons indicative for each isomer configuration. While the α-isomer exhibits 1,3-diaxial interaction between H-18 (δ 2.37) and CH3-27 (δ 1.39) as well as CH3-29 (δ 1.24), the β-isomer shows interaction between H-18 (δ 2.18) and equatorial CH3-28 appearing at δ 0.82 (Fig. 2A and B). ROESY spectra acquired from all licorice samples revealed that the presence of G in its β-form coincides with standard GA β-isomer crosspeak patterns (Fig. 2C). The variance was assessed by analyzing samples from three biological replicas for each specimen. Analytical reproducibility was further assessed by measuring triplicate NMR measurements over 2 days for the biological sample GG1 and showing almost superimposed crosspeak results (data not shown). These results confirm previous reports highlighting that the β-isomer is the natural form of glycyrrhizin in G. glabra and extends to allied species studied in this paper such as G. inflata and G. uralensis. It should be noted that GA was present at trace levels in all extracts as revealed from LC/MS analysis [17] revealing that all signals assigned for GA aglycone by NMR were attributed to its glycoside form G. This result poses NMR as an appropriate tool for G isomer assignment without any chromatography step. The absence of α-glycyrrhizin, a product of the β-isomer under alkaline conditions [18], shows that the samples were not subject to any major chemical isomerization or degradation and suggest that NMR can be applied to identify licorice samples that have undergone partial decomposition.

Anti-inflammatory effect in relation to total phenolics (TP) content

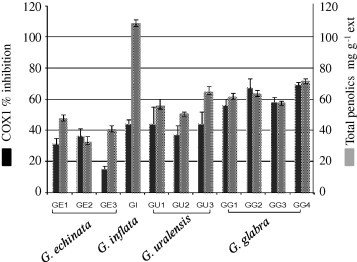

To address the issue of potential variation of the anti-inflammatory activity different species and accessions, we measured the ability of methanol extracts from 11 samples to inhibit cyclooxygenase-1 (COX1), an enzyme involved in inflammation processes (Fig. 3). G. glabra shows inhibitory effect on COX and LOX products [19]. In this study, extracts prepared from G. glabra and G. uralensis, were among the most effective ones, whereas extracts from G. echinata were the least effective ones tested at doses of 100, 150, and 200 μg/ml. Previous investigations concluded that G is an anti-inflammatory compound in licorice, acting by inhibiting the release of inflammatory mediators [20]. Nevertheless, both β-G and β-GA were found inactive on COX1 in our assay setup up at a dose of 500 μg/ml. In contrast to these results, liquiritin, a major flavonoid in Glycyrrhiza sp. [17] was active in the COX1 assay with an IC50 value of 96 ± 8 μg/ml. In addition to triterpene saponins, numerous pharmacologically active polyphenols in quantities of 1–5% have been isolated from Glycyrrhiza sp. and might be accountable for its potent anti-inflammatory effect [21]. These findings suggest that with regard to COX1 inhibition enzyme assay, phenylpropanoids constitute an indispensible part of licorice anti-inflammatory efficacy, arguing for a possible (synergistic or at least additive) effect of several secondary metabolites in targeting different enzymes involved in inflammation. A positive relationship appears to exist between the total polyphenols (TP) content and the anti-inflammatory activity for most species, with a potential correlation to phenolic antioxidant activity. Accessions demonstrating the most potent anti-inflammatory effect were enriched in TP, i.e. G. glabra and G. uralensis showed the best effect. A similar trend to the opposite side was observed for species with low TP, i.e. G. echinata (Fig. 3). Thus, total COX1-inhibitor activity of crude methanol extracts appeared to be dominantly correlated to the (TP) content, which differs across species. It should be noted that no significant difference in TP or anti-inflammatory effect was observed for samples belonging to the same species but coming from different geographical origin. These data support the observation that licorice is an effective COX 1 inhibitor, and provide more insight into the nature of the compounds mediating for such an effect.

Fig. 3.

Anti-inflammatory activity against COX1 and total phenolics (TP) content of Glycyrrhiza sp. extract tested at a dose of 100 μg ml−1 (n = 3). Results are expressed for anti-inflammatory activity as % inhibition to control on the Y1 axis and for polyphenol content as mg g−1 as displayed on the Y2 axis. Glycyrrhiza samples include: (GE1, GE2, GE3; G. echinata), (GU1, GU2, GU3; G. uralensis), (GG1, GG2, GG3, GG4; G. glabra) and (GI; G. inflata), for sample codes, see Table 1.

Cytotoxic effect of G. inflata in relation to licochalcone A

Increasing evidence in the literature point toward the marked cytotoxic effect found for licorice flavonoids including isoliquiritigenin [22]. Our objective was also to investigate cytotoxicity potential of licorice extracts with different flavonoid composition as revealed from our chemical analysis [17]. All samples were tested for growth inhibition of (mutated androgen dependent) prostate (PC3) and (androgen independent) colon (HT-29) cancer cell lines at doses of 5, 10 and 20 μg/ml. All extracts show only weak inhibition in this assay setup, except for G. inflata with an IC50 value of 13 and 17 μg/ml for HT29 and PC3, respectively. The high content of moderately cytotoxic compounds such as polyphenols and chalcones in G. inflata [17] probably is responsible for the growth inhibition effect. Relevant amounts of licochalcone A, the major isoprenylated retrochalcone in G. inflata, are absent in the other species samples as revealed by 1H NMR analysis [17]. Thus pure licochalcone A was tested separately and exhibited significant activity at lower IC50 values (PC3, 9.6 μg/ml; HT29, 8.0 μg/ml) suggesting that it likely is the main mediator of cytotoxicity in G. inflata extract. Indeed, several laboratories evidenced the marked cytotoxic effect for licochalcone A against various cancer cell lines including lung, colon, prostate and skin cancer cell lines [23]. Several other retrochalcones such as licochalcone C and D were present in G. inflata extract and may act additively or even synergistically with licochalcone A. Our results provide more insight for metabolites mediating licorice biological effect and concur previous scientific evidence that polyphenols contribute to a large extent for licorice medicinal use as in case of deglycyrrhizinated licorice (DGL).

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

Authors declare that this study does not include work on patients or animals and does not need the approval by the appropriate Ethics Committee or IRB.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

References

- 1.Fiore C., Eisenhut M., Krausse R., Ragazzi E., Pellati D., Armanini D. Antiviral effects of Glycyrrhiza species. Phytother Res. 2008;22:141–148. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka A., Horiuchi M., Umano K., Shibamoto T. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of water distillate and its dichloromethane extract from licorice root (Glycyrrhiza uralensis) and chemical composition of dichloromethane extract. J Sci Food Agric. 2008;88:1158–1165. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee C.K., Park K.K., Lim S.S., Park J.H.Y., Chung W.Y. Effects of the licorice extract against tumor growth and cisplatin-induced toxicity in a mouse xenograft model of colon cancer. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:2191–2195. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi M., Fujita K., Katakura T., Utsunomiya T., Pollard R.B., Suzuki F. Inhibitory effect of glycyrrhizin on experimental pulmonary metastasis in mice inoculated with B16 melanoma. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:4053–4058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Csuk R., Schwarz S., Kluge R., Stroehl D. Synthesis and biological activity of some antitumor active derivatives from glycyrrhetinic acid. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45:5718–5723. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simons R., Vincken J.P., Bakx E.J., Verbruggen M.A., Gruppen H. A rapid screening method for prenylated flavonoids with ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry in licorice root extracts. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2009;23:3083–3093. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fenwick G.R., Lutomski J., Nieman C. Licorice, Glycyrrhiza-Glabra – composition, uses and analysis. Food Chem. 1990;38:119–143. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Q., Ye M. Chemical analysis of the Chinese herbal medicine Gan-Cao (licorice) J Chromatogr A. 2009;1216:1954–1969. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabbioni C., Mandrioli R., Ferranti A., Bugamelli F., Saracino M.A., Forti G.C. Separation and analysis of glycyrrhizin, 18 beta-glycyrrhetic acid and 18 alpha-glycyrrhetic acid in liquorice roots by means of capillary zone electrophoresis. J. Chromatogr A. 2005;1081:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasaki H., Takei M., Kobayashi M., Pollard R.B., Suzuki F. Effect of glycyrrhizin, an active component of licorice roots, on HIV replication in cultures of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from HIV-seropositive patients. Pathobiology. 2002;70:229–236. doi: 10.1159/000069334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cinatl J., Morgenstern B., Bauer G., Chandra P., Rabenau H., Doerr H.W. Glycyrrhizin, an active component of liquorice roots, and replication of SARS-associated coronavirus. Lancet. 2003;361:2045–2046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13615-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krausse R., Bielenberg J., Blaschek W., Ullmann U. In vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of Extractum liquiritiae, glycyrrhizin and its metabolites. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:243–246. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y.C., Yang Y.S. Simultaneous quantification of flavonoids and triterpenoids in licorice using HPLC. J Chromatogr B. 2007;850:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabbioni C., Mandrioli R., Ferranti A., Bugamelli F., Saracino M.A., Forti G.C. Separation and analysis of glycyrrhizin, 18 beta-glycyrrhetic acid and 18 alpha-glycyrrhetic acid in liquorice roots by means of capillary zone electrophoresis. J Chromatogr A. 2005;1081:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenreich W., Bacher A. Advances of high-resolution NMR techniques in the structural and metabolic analysis of plant biochemistry. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:2799–2815. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Kooy F., Maltese F., Choi Y.H., Kim H.K., Verpoorte R. Quality control of herbal material and phytopharmaceuticals with MS and NMR based metabolic fingerprinting. Planta Med. 2009;75:763–775. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farag M.A., Porzel A., Wessjohann L.A. Comparative metabolite profiling and fingerprinting of medicinal licorice roots using multiplex approach of GC-MS, LC-MS and 1D-NMR techniques. Phytochemistry. 2012;76:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ha Y.M., Cheung A.P., Lim P. Chiral separation of glycyrrhetinic acid by high-performance liquid-chromatography. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1991;9:805–809. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(91)80005-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandrasekaran C., Deepak H., Thiyagarajan P., Kathiresan S., Sangli G.K., Deepak M. Dual inhibitory effect of Glycyrrhiza glabra (GutGard (TM)) on COX and LOX products. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ni Y.F., Kuai J.K., Lu Z.F., Yang G.D., Fu H.Y., Wang J.A. Glycyrrhizin treatment is associated with attenuation of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by inhibiting cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression. J Surg Res. 2011;165:E29–E35. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaya J., Belinky P.A., Aviram M. Antioxidant constituents from licorice roots: isolation, structure elucidation and antioxidative capacity toward LDL oxidation. Free Radical Biol Med. 1997;23:302–313. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X.Y., Yeung E.D., Wang J.Y., Panzhinskiy E.E., Tong C., Li W.G. Isoliquiritigenin, a natural anti-oxidant, selectively inhibits the proliferation of prostate cancer cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2010;37:841–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2010.05395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yo Y., Shieh G., Hsu K., Wu C., Shiau A. Licorice and licochalcone-A induce autophagy in LNCaP prostate cancer cells by suppression of Bcl-2 expression and the mTOR pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:8266–8273. doi: 10.1021/jf901054c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]