Abstract

TOPIC

Evidence–based CBT skills building intervention – COPE -for depressed and anxious teens in brief 30 minute outpatient visits.

PURPOSE

Based on COPE training workshops, this paper provides an overview of the COPE program, it’s development, theoretical foundation, content of the sessions and lessons learned for best delivery of COPE to individuals and groups in psychiatric settings, primary care settings and schools.

SOURCES

Published literature and clinical examples

CONCLUSION

With the COPE program, the advanced practice nurse in busy outpatient practice can provide timely, evidence-based therapy for adolescents and use the full extent of his/her advanced practice nursing knowledge and skills.

Keywords: adolescents, depression, anxiety, evidence-based practice, COPE intervention, cognitive-behavioral therapy, brief therapy

Adolescents are not receiving the evidence-based mental health services they need (National Research Council {NRC} & Institute of Medicine {IOM}, 2009). A 2010 nationally representative sample of US adolescents (National Co-morbidity Survey, Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) found that approximately one in every four to five youth meets criteria for a mental disorder that will impair their functioning across their lifetime (Merikangas et al., 2010). In adolescents ages 13 to 18 years, the prevalence of mental disorders with distress and/or severe impairment is 22% (11% with mood disorders, 8.3% with anxiety disorders, and 9.6% behavior disorders) (Merikangas et al., 2010). Forty percent of teens who meet criteria for one disorder have co-morbidity which meets criteria for another class of lifetime disorder (Merikangas et al., 2010). Unfortunately, these young people are suffering, but fewer than 25% are getting the treatment they need (Foy, 2010). Because many common mental disorders first emerge in childhood/adolescence and are now being considered neurodevelopmental disorders, prevention, early intervention and timely evidence-based treatment are critical (Merikangas et al., 2010; March, 2009). Advanced Practice Psychiatric Nurses (APPN), along with their family NP and pediatric NP colleagues, strive to provide excellent evidence-based treatment for the many depressed and anxious teens they see in their practice settings. It is a challenge to find developmentally appropriate, evidence-based interventions that are portable and easily used by clinicians who have the time constraints, productivity requirements, and full schedules characteristic of practice settings today (Foy, 2010). Interventions that incorporate the principles of sound, empirically tested psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), into manuals or formats that are well accepted by the teens and their parents are needed. There are time-tested manualized CBT based programs available for anxious and depressed teens: Lewinsohn & Clarke (Adolescent Coping with Depression Course CWD – A (Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops, and Andrews, 1990); Coping with Stress Course, CWS (Clarke et al., 1995); Steady Project (Clarke, Debar, Ludman, Asarnow, and Jaycox, 2002), but these are primarily structured for the 50 minute individual therapy hour characteristic of the traditional psychotherapy model (Whisman, 2008; Rhode, Feeny, & Robins, 2005). In busy clinics today, it is the 20–30 minute medication management visit that frames our practice and challenges us to find new models of effective, evidence based treatment.

The high prevalence of depression and anxiety in young people, in combination with current estimates that the national economic burden of mental disorders on the well being of American youth and their families approaches a quarter of a trillion dollars, underscores the importance of actively addressing emerging mental health needs of American youth (Merikangas et al., 2010). The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended that all young people ages 12 – 18 years old be routinely screened for major depressive disorder in primary care (USPSTF, 2009). The USPSTF recommendation adds the caveat, “when systems are in place to ensure: accurate diagnosis, cognitive-behavioral or interpersonal psychotherapy and follow up” (USPSTF, 2009 p. 1223). Screening for elevated levels of depression and anxiety can be routinely conducted in clinical settings, with such instruments such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) for anxiety, which are both in the public domain and can be used without a fee. Anxiety is often co- morbid with depression. Advanced practice psychiatric nurses have the knowledge and skills to screen, diagnose, perform psychotherapy, and provide follow-up care for adolescents and are in ideal positions to evaluate and provide treatment for teens needing mental health care (Wheeler, 2008). Further, primary care advanced practice nurses also can be instrumental in screening, identifying and providing evidence-based care for adolescents with mild to moderate depressive and anxiety symptoms.

There is strong evidence to support Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) as an effective first line treatment for depressed and anxious teens (March, 2009; Williams, O’Connor, Eder, and Whitlock, 2009; Watanabe, Hunot, Omori, Churchill, & Farukawa, 2007). There is a need for evidence-based CBT interventions that are portable, have demonstrated ease of use, and can be used in a variety of settings where adolescents are routinely seen. Teens are often placed on long waiting lists for specialty psychiatric care, when they need access to timely, active, evidence-based treatment (Jaycox et al., 2006; Weersing & Weisz, 2002). One cognitive behavioral skills building program for teens that can be presented in the 20 – 30 minute visits characteristic for current advanced practice was developed by Melnyk (2003) and is named COPE, an acronym for “Creating Opportunities for Personal Empowerment.” COPE is a manualized – 7 session, brief, time limited cognitive behavioral skills building therapy (CBSBT) that has been delivered in a variety of settings, including outpatient mental health centers, primary care clinics and schools. The developmentally based intervention is clearly written with teen appropriate illustrations, and has been well accepted by adolescents from 12 years to 18 years of age and their parents (Lusk & Melnyk 2011a). Measured outcomes pre- and post-COPE indicate this CBT based intervention decreases anxiety and depression in teens, and improves self concept (Lusk & Melnyk, 2011a). Because the COPE sessions can be delivered within 20 – 30 minute visits, including the usual medication management visits, the advanced practice NP can practice within the full scope of the advanced role and provide therapy (Wheeler, 2008) as well as medication management and follow up.

Evidence-based psychotherapy can be part of standard care for teens seen in practices where COPE is offered. In many clinical settings, insurance and Medicaid reimburse the APPN for the COPE sessions (CPT Code 90805) as individual psychotherapy & evaluation and management which is often reimbursed at a slightly higher rate than (CPT 90862) medication monitoring. The COPE sessions clearly meet the CPT code 90805 criteria of face to face therapy for more than 50% of the visit (Schmidt, Yowell, & Jaffe, 2004), with time spent assessing the teen for need for medication, response to treatment (medication if applicable), vital signs (pulse, blood pressure) or other evaluation of health status and ongoing management of health concerns.

Development of the COPE intervention

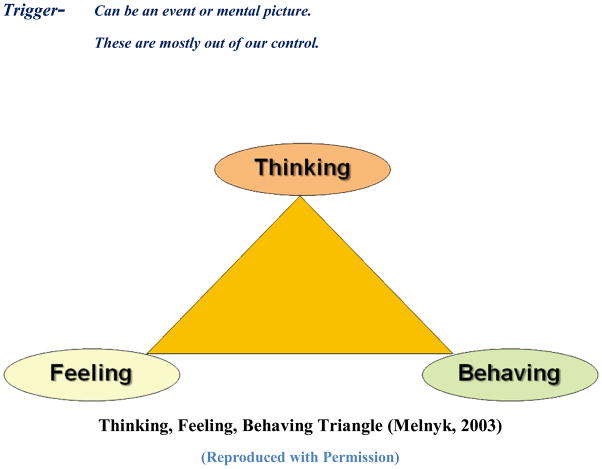

COPE was developed by Bernadette Mazurek Melnyk, a pediatric nurse practitioner and psychiatric/mental health nurse practitioner, first as a health promotion/educational and skills building intervention for adolescents on an inpatient psychiatry unit in order to enhance their ability to cope and deal with stressful challenges and engage in healthy behaviors. The first rendition of the COPE program was a 15 session cognitive behavioral skills building healthy lifestyles intervention, entitled the COPE Healthy Lifestyles TEEN (Thinking, Emotions, Exercise and Nutrition) Program, and tested in 60–75 minute sessions with groups of teens in after school and school-based classroom programs. The first 7 sessions of the 15-session program contain the CBT-based educational content with activities that are delivered in the brief COPE for teen depression and anxiety (Table 1). The other 8 sessions of the COPE TEEN program contain education and skills building activities focused on nutrition, physical activity and healthy lifestyle behavior change. Over a period of years delivering the COPE program, assessing adolescent responses to the program, and incorporating their feedback and preferences, Melnyk fine-tuned the sessions to be developmentally appropriate and engaging for the teens. Findings from pilot studies testing the 15-session COPE program with high school teens indicate: (a) decreases in depressive and anxiety symptoms, (b) increases in self-esteem, healthy lifestyle beliefs, healthy lifestyle behaviors and physical activity, and (c) higher academic retention rates (Melnyk et al., 2007; Melnyk et al., 2009). The 15 session COPE Healthy Lifestyle Program is now currently being tested in a randomized controlled trial with 779 predominantly Hispanic teens in 11 Phoenix area High Schools with funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (1R01NR012171; Melnyk, Principal Investigator). In this trial, the 15 COPE sessions are integrated into the students’ health course and taught by the teachers, who were trained to deliver the program. High Schools in other geographic areas with rural populations have incorporated the COPE program into the 9th grade health course as well (Ritchie & McCrone, 2012). COPE also has been delivered as part of after school group intervention programs in an urban high school and sub-urban high school with adolescent participants who were overweight; Melnyk et al., 2007). The seven session program as discussed here (using Melnyk’s original COPE manual content), has been presented in a brief, 20–30 minute individual therapy format to 12 – 18 yr old depressed adolescents in a rural Southwestern US community mental health center (Lusk, Melnyk, 2011a) and as the standard intervention (individual sessions) at an urban primary care clinic for anxious and depressed teens (Lusk & Melnyk, 2011b). Exclusions for participating in the COPE program have been teens with developmental delays/ low cognitive functioning and youth with active psychosis, as it is thought that the cognitive approach of COPE is not the best treatment approach for these teens. The COPE 7 session individual treatment format is currently being offered to a wide range of teens with mental health and physical concerns in pediatric practices, inner-city outpatient mental health clinics and federally qualified health centers in a variety of geographical areas. COPE participants have represented ethnically diverse groups, and ages have ranged from 12 year old middle school students to 18 yr. old high school seniors. In the authors previous COPE study (Lusk & Melnyk, 2011a), teens that had completed the COPE 7 session program and their parents filled out post – COPE questionnaires. They reported that the sessions were interesting and covered topics of interest. All reported that, in the 20 – 30 minute sessions, they were able to cover the session main idea (content), review the homework practice assignments and still have time to bring up any particular concerns they had at that time. Outcomes monitoring – by administration of the Beck Youth Inventories – for depression, anxiety, and self - concept indicated a significant decrease in depressive and anxiety symptoms, and an increase in self concept pre- to post COPE completion of the BYI questionnaires (statistical analysis previously published, Lusk & Melnyk, 2011). When the young people who have completed the program – provide feedback later, both the young teens and the 18 yr olds all report that COPE addressed their “presenting problem” and provided them with new ways of thinking, and new coping skills that they continue to use in their daily lives. They have provided specific examples of improvement in their school, social and family relationships, “I learned about how to cope with anxiety, because before I didn’t really know how to deal with it in the right ways.” “It made me more confident in myself. I tried out for the school choir, and made it. I have made some good friends there.” “It helped me take a second to think about things before I react ….I am less mean to people”. They also can identify specific COPE session skills, such as deep breathing, imagery, or changing a negative thought to a positive thought that they used to handle difficult situations that they experienced “I was in a car, and there was a drive by shooting, and I just did the deep breathing like we practiced. I was scared, but that got me through it.” From a foster parent, “She will repeat positive statements about herself, instead of the negative ones she repeated frequently when she was placed in my home.” They express that they feel proud of their increased ability to self- regulate their responses to stressful events (triggers) and deal with the problematic situations/ triggers in healthier ways, “I’m bringing out my anger in a healthy way, instead of punching walls and stuff like that.” From parents, “I think it has given him ideas on dealing with anger triggers that may not have occurred to him before”. “He seems to try harder, like when he gets mad; I’ve seen him trying to stop.” When asked what they remembered most about the COPE program, the nearly unanimous response is: the thinking, feeling behaving triangle. Figure 1, “I remember the triangle that shows you how you think is how you feel and behave…because I could see when that actually happened.”

Table 1.

COPE Session Topics

| Introduction: | COPE Program and goals |

|---|---|

| Session 1 | Thinking, Feeling, Behaving Triangle |

| Session 2 | Self-esteem and positive thinking, self-talk |

| Session 3 | Goal Setting and problem-solving |

| Session 4 | Stress and coping |

| Session 5 | Emotional and behavioral regulation |

| Session 6 | Effective communication, personality and communication styles |

| Session 7 | Barriers to goal progression and overcoming barriers Energy balance; ways to increase physical activity and benefits |

| Session 8 | Heart rate; stretching |

| Session 9 | Food groups and a healthy body; stoplight diet (red, yellow, green) |

| Session 10 | Nutrients to build a healthy body: reading labels, media and advertising effects on food choices |

| Session 11 | Portion sizes; “supersize”, influences of feelings on eating |

| Session 12 | Social eating: strategies for eating during parties, holidays, and vacations |

| Session 13 | Snacks and eating out |

| Session 14 | Integrate skills and knowledge to develop a healthy lifestyle plan |

| Session 15 | Putting it all together; review of course content |

Figure 1.

COPE as an evidence-based intervention

Evidence to support CBT based interventions as effective first line treatment for depressed and anxious teens includes systematic reviews, and several meta-analyses, the strongest level of evidence (Williams et al., 2009; Klein et al., 2007; Weisz & McCarthy, 2007; Watanabe et al., 2007). The meta- analysis by McCarty & Weisz (2007) identified the components of psychotherapy for depressed teens, present in the most effective therapy programs. The 12 components of effective therapy for depressed adolescents according to the Weisz and McCarty review of studies are: Achieving measurable goals/ competency, Adolescent psycho- education, Self-monitoring, Relationship skills/ social interaction, Communication training, Cognitive restructuring, Problem solving, Behavioral activation, Relaxation, Emotional regulation, Parent psycho education, and improving the parent child relationship (McCarty & Weisz, 2007). The COPE program includes all of these 12 components of effective CBT for depressed teens.

Theoretical Framework

Cognitive Behavior Theory largely guided the development of the COPE Healthy Lifestyles TEEN Intervention program (Melnyk et al., 2007; Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979). In Cognitive Behavior Theory, it is contended that how an individual thinks affects his or her feelings or emotions and behaviors (Beck, J., 2011; Beck et al., 2011), otherwise known as the “thinking, feeling, behaving” triangle. Figure 1 (Melnyk, 2003; Melnyk et al., 2007). The cognitive theory of depression and psychotherapy as developed by Aaron Beck (Beck et al., 1979) focuses on identifying and correcting “cognitive distortions” or automatic negative thoughts. From this theoretic perspective, a person who has negative thoughts or beliefs is more likely to have negative emotions (e.g., anxiety and depression) and display negative behaviors (e.g., risk taking and poor school performance). Active components of Cognitive Behavior therapy include reducing negative thoughts (cognitive restructuring), increasing pleasurable activities (behavioral activation) and improving assertiveness and problem solving skills (homework assignments). Melnyk found that incorporating skills building activities, and reinforcing the practice of these skills were a critical element in the teen’s improvement. Lewinsohn & Clarke had stressed with their programs, Adolescent Coping with Depression Course in Depression CWD-A, (Lewinsohn et al., 1990) and Coping with Stress Course CWS, Clarke et al., 1995 ) that lack of positive reinforcement from pleasurable activities leads to negative thought patterns. Behavior theory suggests that individuals are depressed/ anxious not only because of lack of positive reinforcement, but also a lack of skills to elicit positive reinforcement from others or to terminate negative reactions from others. In COPE sessions, these concepts are emphasized and the teen identifies activities (especially physical activities) that are pleasurable for them and they are encouraged to increase time spent with those. Self regulation of behavior is a key coping strategy reinforced throughout the program. COPE is a CBSB program that actively promotes mastery of adolescent developmental tasks by each participant. The message to the teen is “You can do it. You can develop skills to COPE with whatever you are facing. By monitoring your thoughts and beliefs and changing negative thinking to positive thoughts, you can change/regulate your subsequent feelings and behaviors and feel better.” The thinking, feeling, behaving model of CBT “resonates beautifully with recent developments in cognitive, affective and social neuroscience “(March, 2009, p. 173) and is health enhancing from a neurodevelopmental view of emerging mental disorders. We know that in adolescence, there is pruning and growth of new neuronal connections. When the young person learns to think and practices coping in positive ways, myelin lays down new tracks. Psychotherapy interventions during the period of adolescence provide a prime opportunity to establish new healthy neuronal connections and the practice and reinforcement of skills learned in CBT programs such as COPE likely modify developmental trajectories in a positive way (Merikangas et al., 2010; March, 2009).

Delivery of the COPE program

In presenting COPE sessions weekly, lessons have been learned and delivery protocols have been refined. The “how to” deliver COPE sessions is presented here using Beck’s 10 principles of Cognitive Behavior Therapy as the organizing framework (Beck, J., 2011).

#1 Cognitive therapy is based on an ever-evolving formulation of the patient and his/her problems in cognitive terms

Prior to initiation of any COPE sessions, the new patient adolescent and parent meet with the APPN for a couple of visits. The first visit is an initial psychiatric evaluation (including chief complaint, history of presenting problem, family history, medical problems, environmental stressors, mental status exam). Following the USPSTF recommendations, adolescents 12 yrs to 18 yrs are screened using the Beck Youth Depression Inventory, Beck Youth Anxiety Inventory, and Beck Youth Self-Concept Inventory – self report instruments that generally take about 10 – 15 minutes to fill out (Beck, Beck & Jolly, 2005; Steer, Kumar, Ranieri, & Beck, 1998). Teens also fill out a personal beliefs scale developed by Melnyk, to assess the teen’s perceived belief in influencing their own health (Melnyk et al., 2009). The teens’ identification of personal strengths, accomplishments and goals is a very important part of this initial diagnostic formulation. At the conclusion of the initial evaluation, recommendations are shared with the teen and parent/ or caregiver. The family is invited to share their previous experiences with mental health care, their personal preferences and values and these are incorporated into the treatment plan. In evidence based practice, 1) the best evidence and 2) the personal preferences of the patient and family, as well as 3) the clinical expertise of the provider are all essential components of establishing the treatment plan (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2011). The APPN has the education and expertise to provide the best evidence based interventions for depressed and anxious adolescents as agreed upon with the teen and family.

Confidentiality and safety

Issues about confidentiality/ and times when the APPN needs to involve others for the safety of the teen are directly stated at this first appointment and teens/ parents are asked to voice their understanding of these basic “rules” of treatment. If at any time during the COPE program, the teen or family presents in crisis, the crisis situation (SI or HI) is addressed as a priority. The COPE process can continue once the priority issue is resolved.

#2 Cognitive therapy requires a sound therapeutic alliance

After the initial evaluation, another visit is scheduled and at this second, less structured visit, the APPN again reviews the treatment options for the teen and allows time for listening to the teen and parent’s questions and concerns. This visit sets the stage for the beginning therapeutic relationship. It is critically important that the teen perceive that the therapist is invested in the youth and parent. The therapist has as primary goals: instilling hope, providing information that depression and anxiety are treatable medical conditions, and developing rapport and cognitively connecting with the teen.

#3 CBT emphasizes collaboration and active participation

If the teen is depressed, anxious or both the family is told about the options of cognitive – based therapy, medications, or a combination of the two. The family is advised that there is strong evidence to support CBT as the first line treatment in mild and moderate depression in adolescents (Van Voorhees, Smith, & Ewigmen, 2008; Brimaher & Brent, 2007; Cheung et al., 2007). At our clinic the COPE program is the standard treatment for depression/ anxiety in teens. The very basic premise of CBT is explained, using the COPE manual Thinking Feeling Behaving diagram Figure 1. In addition some written materials (i.e. the article by Van Voorhees et al., 2008 from the Journal of Family Practice) are provided for them to take home and review. In our practice, we often find that families and/or teens feel quite strongly that they want a treatment/ intervention that does not include starting a medication. It is at this point that we show them the COPE for Teens manual and allow time for them to look through it. They are instructed to make an appointment for a follow up visit if they want to begin COPE. If they agree to have outcomes measured long term as part of our study those consents and questionnaires are filled out at this time. Teens are given their own COPE manual with their name on it. Parents are encouraged to become an active participant in the program, attend sessions with their teen, and review the homework for the weekly sessions with their teen.

#4: Cognitive therapy is goal oriented and problem focused

From the initial visit, the teen identifies the problem that they wish to address, and very specific goals are established to work together toward solving their identified problem. We frame their identified chief concern in CBT language – using the thinking, feeling, behaving triangle. The COPE sessions address usual developmental concerns of adolescents. Within the context of the session content, teens are prompted to bring up their version of developmentally based dilemmas such as expressing emotions in ways that get your feelings expressed without hurting others or yourself, setting goals, the steps of problem solving, etc. In the COPE program there is always a strong emphasis on identifying the strengths and special abilities of the teen. Positive self talk is one of the earliest skills introduced. This skill is reinforced throughout the COPE program. This emphasis on the teens’ individual strengths, abilities, and dreams vs. the teens’ problem behaviors has proven to be an important element in improving parent/ child relationships over time.

#5: Cognitive therapy initially emphasizes the present

This approach is very positively received by teens and their parents. When the emphasis is on the present vs. past experiences, parents tend to feel less “blamed” for their teen’s difficulties. The COPE sessions identify current experiences, and set goals that are measurable and proactive for addressing current concerns. The skills learned in relation to the present are applicable to past and future stressful situations.

#6 Cognitive therapy is educative, aims to teach the patient to be his/her own therapist, and emphasizes relapse prevention

The teen and parent are taught the theory of CBT, the background studies that have led to this being the best evidence-based intervention for depressed and anxious teens, (March, 2004) and why and how CBT works. They are shown examples of functional MRI’s that now “prove” that psychotherapy changes the brain. We review neurodevelopment in adolescents, and discuss that this is a stage of development when new neuronal connections are rapidly being made, and how that growth in the brain makes psychotherapy especially effective and health promoting with 12 to 18 yr olds (and actually up to 25 yrs)(Dobbs, 2011; March, 2009). When families understand why a therapy works and the rationale for the session structure (homework, and skills practice) they are more likely to follow through and complete the course of treatment. Homework assignments provide an opportunity between sessions, for the teen to apply the skills and concepts to their everyday life.

#7: Cognitive therapy aims to be time limited (4 – 14 sessions)

In keeping with the Beck approach of time limited therapy, COPE is generally 10 weekly visits. (Psychiatric evaluation at first visit, establishment of alliance, and answering questions at the 2nd visit, then the 7 COPE sessions, and a follow up visit to complete post COPE surveys). With busy family schedules, an occasional week is missed. Generally from initial appointment until completion of the Post COPE surveys is 12 weeks, with an opportunity to schedule “booster” sessions at 3 month intervals post treatment.

#8: Cognitive therapy sessions are structured

The clear, predictable structure of COPE sessions reduces anxiety in young people in our experience. Teens tell us they have been very uncomfortable at times with traditional counseling sessions where they felt pressure to come up with a meaningful narrative account of their past week, and to prioritize issues they need to address in the therapy session. The structure of the COPE session is always the same. Homework from the last session is reviewed, and then the COPE session content is covered word for word from the manual, and just prior to ending the session, the homework assignment for the session is reviewed and weekly goals identified. The manual’s clarity and straightforward approach make it easy to use for teens in brief sessions. To present a COPE session, the clinician reads the content, Word for Word. This assures that each teen receives a “pure dose” – that is - all of the CBT content and then the teen can supply their own examples of the situations / experiences etc described in the sessions. Homework not only provides an opportunity for teens and parents to share and practice new skills, but it also “extends the session”, a clear benefit with a program delivered in brief visits.

#9: Cognitive therapy teaches patients to identify, evaluate, and respond to their dysfunctional thoughts and beliefs

Parents and teens are taught that the principles of CBT apply to everyone. There are difficult events and situations that occur in our everyday lives and these “triggers” are often out of our control, however the good news is, the thoughts we have, (and the subsequent feelings and behaviors) can be identified and changed. This is empowering; we can take control of our responses to difficult events/ situations. This, in Beck’s terms, is positive reappraisal of our negative automatic thoughts. Everyone has negative automatic thoughts; thoughts that are so well practiced, they are almost reflexive. We develop automatic thoughts from our parenting, personal experiences, peer relations, media messages and popular culture. Table 2. These are enduring views of ourselves, people in our world, and the way the world works (Beck, 2011; Creed et al., 2011; Beck et al., 1979). Teens are taught to “catch”, or become attuned to when they have a negative thought. (Younger teens can actually use a catching motion) Table 3. Often it is a mood change or physical sensation that signals an automatic negative thought. The first question we learn to ask is: What was I just thinking? As a detective or personal scientist, we ask more questions- and reappraise the automatic negative thought in order to restructure - to change from a negative thought to a positive thought (cognitive restructuring). Questions we use in COPE for questioning automatic negative thoughts are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Automatic Negative Thoughts as classified in CBT (Beck, 2011)

| Teen examples from COPE sessions © | |

|---|---|

| All or nothing thinking. | “If I don’t get all A’s then I am not keeping up with the smart kids and I am a failure” “Less than an A is not acceptable” |

| Catastrophizing- | “If I get a B- on that test, I will get a B in the course, and I won’t have the grades I need to get into college, and I will end up working at a bad job the rest of my life, no one will marry me and I’ll live life as a pathetic loner” |

| Labeling. | “I’m an idiot”. “I’m a loser”. “I am stupid”. “I am slow”.” I’m ugly”. |

| Mind reading | “I know that group of girls thinks I am stupid, and awkward. I know they would never want to be seen with me” |

| Shoulds | “I should never get angry” “I should be able to give an oral report without feeling all nervous, I’m a junior” |

| Ignoring evidence | “I don’t care if I have an A in the course, this last assignment is 10 pages and I probably will mess it up so bad the teacher won’t even accept it” |

| Expecting the worst | “That school trip is scheduled for Washington DC, but what if the plane crashes, or what if no one will sit by me on the tour bus, or what if the parents that chaperone are annoying” |

| Jumping to conclusions | “I don’t know what cognitive behavior therapy is, but I am sure I’ll be an utter failure at COPE” |

Table 3.

Cognitive Reappraisal with Teens

| When my mood changes, and my emotions are going in a negative direction, and I feel body sensations like flutters in my gut, I can “catch” my automatic negative thought by asking: (Beck, 2011; Creed et al., 2011) |

| “What was just going through my mind?” “What was my thought?” |

| COPE COGNITIVE REAPPRAISAL PROCESS © |

| In COPE sessions we encourage the teens to be a detective, a lawyer/ judge, a personal scientist: |

| Questions to ask about that negative automatic thought: |

|

Positive reappraisal and cognitive restructuring are important components of the treatment. As the teen learns the process of using the thinking, feeling, behaving triangle, the parent and APPN can provide examples from their own automatic negative thoughts, and how those thoughts contributed to feeling bad, and behaving in ways that may not lead to positive responses from others. Teens enjoy hearing their parent share about their own automatic negative thoughts and how the parent has learned to cope with stressors and interpersonal problems in their own lives.

#10: Cognitive therapy uses a variety of techniques to change thinking, mood, and behavior

Examples of skills taught in COPE sessions are: staying in the moment, guided imagery, thought stopping, abdominal breathing, and communicating with others in positive ways. The whole set of skills is covered with each teen, and then the individual teen chooses skills that resonate with them as the skill that feels “like me” to address their priority symptoms i.e. thought stopping for obsessive worrying. For example, some thought stopping techniques would include: Visualizing a stop sign, Saying STOP out loud, wearing a rubber band on the wrist and snapping it to stop, Visualize watching the thought on TV and having a remote control and clicking OFF. A guided imagery script to help the teen to visualize a pleasant, peaceful place for them is in the COPE Teen manual.

Conclusions and Implications for Practice

Cognitive Therapy is a straightforward approach for depressed and anxious teens, and COPE sessions present CBT concepts in a clear, concise way using developmentally appropriate illustrations and examples. This “simple” portable intervention approach is powerful and effective for the teens. They learn and practice coping skills, and apply the thinking, feeling, behaving triangle at each session, which allows them to become so comfortable with the skills that when they need them (i.e. deep breathing) they have them readily at their disposal. COPE is an example of a portable intervention, easily used in a variety of settings where teens are usually seen (office practice, inpatient settings, schools, juvenile detention facilities, home visits). COPE training workshops are offered to prepare NPs to offer the program in their particular practice settings. To present a session to a teen, all the NP needs is a COPE TEEN manual (available electronically for printing) and a notation in a progress note about which session the teen completed at the previous visit. Safety assessments and medication management /evaluation if indicated fit nicely within the 20–30 minute COPE sessions. A major advantage for COPE as the standard evidence-based treatment in practice is that teens can get started in active treatment right away.

With COPE, even with our fast paced, busy practice environments, APPNs and other NPs can provide timely, evidence-based therapy for adolescents and practice using the full extent of our skills, educational background and experience.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported, in part, by the NIH/National Institute of Nursing Research (R01#1R01NR012171); PI: Bernadette Mazurek Melnyk.

Contributor Information

Pamela Lusk, Associate Professor, Director, Post Masters to DNP Program, Brandman University.

Bernadette Mazurek Melnyk, Associate Vice President for Health Promotion, University Chief Wellness Officer, Dean and Professor, College of Nursing, Professor of Pediatrics and Psychiatry, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University.

References

- Beck A, Rush A, Shaw B, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beck J. Cognitive therapy: Basics and beyond. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beck J, Beck A, Jolly J. Beck youth inventories for children and adolescents: Manual. 2. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Brent D. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(11):1503–1526. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318145ae1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung A, Zuckerbrot R, Jensen P, Ghalib K, Laraque D, Stein R. Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):131. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke G, DeBar L, Ludman E, Asarnow J, Jaycox L., producer STEADY PROJECT Intervention Manual: Collaborative care, cognitive-behavioral program for depressed youth in a primary care setting 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Clarke G, Hawkins W, Murphy M, Sheeber L, Lewinsohn P, Seely J. Targeted prevention of unipolar depressive disorder in an at-risk sample of high school adolescents: A randomized trial of a group cognitive intervention. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:312–321. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199503000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark G, Rohde P, Lewinsohn P, Hops H, Seely J. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of adolescent depression: Efficacy of acute group treatment and booster sessions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(3):272–279. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199903000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creed T, Reisweber J, Beck A. Cognitive therapy for adolescents in school settings. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs D. Beautiful brains: The new science of the teenage brain. National Geographic. 2011;220(4):37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Foy J, editor. Enhancing pediatric mental health care: Report from the American Academy of Pediatrics task force on mental health. Pediatrics. 2010;125(Supplement 3):s69–s160. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0788C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox L, Asarnow J, Sherbourne C, Rea M, LaBorde A, Wells K. Adolescent primary care patients’ preferences for depression treatment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health Services and Mental Health Services Research. 2006;33:198–207. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein J, Jacobs B, Reinecke M. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent depression: A meta-analytic investigation of changes in effect-size estimates. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(11):1403–1413. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180592aaa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn P, Clarke G, Hops H, Andrews J. Cognitive-behavioral group treatment of depression in adolescents. Behavior Therapy. 1990;21:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Lusk P, Melnyk BM. The brief cognitive-behavioral COPE intervention for depressed adolescents: Outcomes and feasibility of delivery in 30 minute outpatient visits. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2011a;17(3):226–236. doi: 10.1177/1078390311404067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusk P, Melnyk BM. COPE for the treatment of depressed adolescents: Lessons learned from implementing an evidence-based practice change. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2011b;17(4):297–309. doi: 10.1177/1078390311416117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March J, Hilgenberg D, Silva S TADS team. The treatment of adolescents with depression study (TADS), Long term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1132–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March J. The future of psychotherapy for mentally ill children and adolescents. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry. 2009;50:1–2. 170–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty C, Weisz J. Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: what we can (and can’t) learn from meta-analysis and component profiling. Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46 (7):879–886. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31805467b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk BM. COPE (Creating Opportunities for Personal Empowerment) for Teens: A 7-Session Cognitive Behavioral Skills Building Program 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. A guide to best practice. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2011. Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare. [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk BM, Jacobson D, Kelly S, O’Haver J, Small L, Mays MZ. Improving the mental health, healthy lifestyle choices and physical health of Hispanic adolescents: A randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of School Health. 2009;79(12):575–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk BM, Small L, Morrison-Beedy D, Strasser A, Spath L, Kreipe R, Crean H, Jacobson D, Kelly S, O’Haver J. The COPE healthy lifestyles TEEN program: Feasibility, preliminary, efficacy, & lessons learned from an after school group intervention with overweight adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2007;21(5):315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson S, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendesen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the national co morbidity survey replication – Adolescent supplement (NCS-A) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council & Institute of Medicine. Adolescent health services: Missing opportunities. The National Research Council and The Institute of Medicine; Washington, D.C: National Academy of Science Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie T, McCrone S. Evaluation of the impact of the COPE Healthy Lifestyles TEEN Program in a rural high school health class. Poster session presented at the 14th Annual Conference of the International Society of Psychiatric Nurses; Atlanta, GA. 2012. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Rhode P, Feeny N, Robins M. Characteristics and components of the TADS CBT approach. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2005;12(2):186–197. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.12-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt C, Yowell R, Jaffe E. CPT handbook for psychiatrists. 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Steer R, Kumar G, Ranieri W, Beck A. Use of the Beck Depression Inventory – II with adolescent psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1998;20(2):127–137. [Google Scholar]

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and treatment for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):1223–1228. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees B, Smith S, Ewigmen B. Treat depressed teens with medication and psychotherapy: Combining SSRI’s and cognitive behavioral therapy boosts recovery rates. The Journal of Family Practice. 2008;57(11):735–739. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Hunot V, Omori I, Churchill R, Farukawa T. Psychotherapy for depression among children and adolescents: a Systematic Review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2007;116:84–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weersing VR, Weisz JR. Community clinic treatment of depressed youth: Benchmarking usual care against CBT trials. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(2):299–310. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler K. Psychotherapy for the advanced practice psychiatric nurse. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MP, editor. Adapting cognitive therapy for depression: Managing complexity and co morbidity. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Williams S, O’Connor E, Eder M, Whitlock E. Screening for child and adolescent depression in primary care settings: A systematic evidence review for the U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics. 2009;123 (4):716–734. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COPE/Healthy Lifestyles for Teens: A School-Based RCT (Principal Investigator) Funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research 1R01NR012171-01) September 30, 2009-June 30 2013