Abstract

Resin monomers (RMs) are inflammatory agents and are thought to cause allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). However, mouse models are lacking, possibly because of the weak antigenicities of RMs. We previously reported that inflammatory substances can promote the allergic dermatitis (AD) induced by intradermally injected nickel (Ni-AD) in mice. Here, we examined the effects of RMs on Ni-AD. To sensitize mice to Ni, a mixture containing non-toxic concentrations of NiCl2 and an RM [either methyl methacrylate (MMA) or 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA)] was injected intraperitoneally or into ear-pinnae intradermally. Ten days later, a mixture containing various concentrations of NiCl2 and/or an RM was intradermally injected into ear-pinnae, and ear-swelling was measured. In adoptive transfer experiments, spleen cells from sensitized mice were transferred intravenously into non-sensitized recipients, and 24 h later NiCl2 was challenged to ear-pinnae. Whether injected intraperitoneally or intradermally, RM plus NiCl2 mixtures were effective in sensitizing mice to Ni. AD-inducing Ni concentrations were greatly reduced in the presence of MMA or HEMA (at the sensitization step from 10 mM to 5 or 50 µM, respectively, and at the elicitation step from 10 µM to 10 or 100 nM, respectively). These effects of RMs were weaker in IL-1-knockout mice and in macrophage-depleted mice. Cell-transfer experiments in IL-1-knockout mice indicated that both the sensitization and elicitation steps depended on IL-1. Challenge with an RM alone did not induce allergic ear-swelling in mice given the same RM + NiCl2 10 days before the challenge. These results suggest that RMs act as adjuvants, not as antigens, to promote Ni-AD by reducing the AD-inducing concentration of Ni, and that IL-1 and macrophages are critically important for the adjuvant effects. We speculate that what were previously thought of as “RM-ACD” might include ACD caused by antigens other than RMs that have undergone promotion by the adjuvant effects of RMs.

Keywords: methyl methacrylate, 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate, dental material, macrophage, IL-1, allergy

Introduction

Resins and metals are frequently encountered in modern life, and they have many medical uses. Thus, contact with them can occur through a variety of routes. In dentistry, for example, resins and/or metals are used as dentures, prostheses, restorations, implants in replacement surgery, orthodontic wires, and various other devices. Resin monomers (RMs) are known to be a cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), especially in dental personnel (Aalto-Korte et al., 2007). Indeed, according to one report, 64% of dermatitis in dental personnel was due to ACD induced by RMs (Rustemeyer and Frosch, 1996). Such RM-induced ACD (RM-ACD) also occurs in dental patients (Gonçalves et al., 2006) and in people who use nail make-up (Teik-Jin Goon et al., 2007). Among the metals, nickel (Ni) is the most frequent contact allergen (Garner, 2004).

RMs are known to be inflammatory, toxic materials (Leggat and Kedjarune, 2003; Paranjpe et al., 2005). However, RMs induce ACD in animal models with potencies reportedly much weaker than those of other well-known chemical haptens, such as oxazolone, dinitrochlorobenzene, and formaldehyde (Kimber et al., 2003; Betts et al., 2006). Rustemeyer et al. (1998) succeeded in sensitizing guinea pigs to RMs, but only by the drastic method of intradermally injecting mixtures of 1 M of RMs (10-20%) in water-Freund’s complete adjuvant (1:1). In our experience with mice, 50% Freund’s complete adjuvant alone (Sato et al., 2007) and such concentrations of RMs alone (unpublished observations) cause severe skin injuries. Thus, the above model may not reflect actual environmental situations that result in ACD in humans and suggest that unknown conditions or factors may be necessary for RM-ACD to occur. As yet, no one has succeeded in inducing RM-ACD in mice. We have reported that various bacterial components or ligands of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) act as potent adjuvants of the allergic dermatitis (AD) induced by intradermally injected Ni (Ni-AD) in mice, and this can occur at both the sensitization and elicitation steps (Sato et al., 2007; Kinbara et al., 2011; Takahashi et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2011). However, our attempts using these substances as adjuvants to produce RM-ACD in mice have all failed.

Having previously found that inflammatory chemicals (nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates) can promote Ni-AD in mice (Takahashi et al., 2011), we hypothesized that: (i) RMs might also promote the establishment of the allergies induced by other antigens by acting as adjuvants, rather than as antigens; and (ii) what were previously thought of as “RM-ACD” might include ACD caused by antigens other than RMs that have undergone promotion by the adjuvant effects of RMs. Interestingly, Sandberg et al. (2005) reported that 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) had adjuvant properties in mice, in which it promoted the production of the antibodies to ovalbumin. In the present study, we tested the above hypotheses by evaluating the effects of RMs on Ni-AD in the skin of mice.

Materials & Methods

Animals

BALB/c IL-1- knockout (KO) mice were established from original IL-1α-KO and IL-1β-KO mice (Horai et al., 1998). Female BALB/c mice were bred in our laboratory under conventional conditions. All mice were raised in standard aluminum cages (with a lid made of stainless steel wires) and allowed standard food pellets (LabMR Stock; Nihon Nosan Inc., Yokohama, Japan) and tap water ad libitum (the latter from a plastic bottle through a stainless steel tube) in an air-conditioned room at 23 ± 1°C and 55 ± 5% relative humidity with a standard cycle of 12 h light and 12 h dark (lights on at 07:00 a.m.). All experiments complied with Regulations for Animal Experiments and Related Activities at Tohoku University.

Reagents

Methyl methacrylate (MMA) and HEMA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). First-grade NiCl2 (purity > 95%) and all other reagents were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Ind. Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), unless otherwise indicated.

Sensitization to Ni and Elicitation of Ni-allergic Inflammation

Mice were sensitized to Ni by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection, except in the experiment illustrated by Fig. 2B, in which Ni was intradermally (i.d.) injected into ear-pinnae. For injection by either route, a mixture of NiCl2 and an RM was used. Ten days later, ear-pinnae were challenged by i.d. injection of NiCl2 solution or a mixture of NiCl2 and an RM near the root of the ear (20 µL/ear). Ear-swelling was measured at the indicated times by means of a Peacock dial thickness gauge (Ozaki MFG Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), and the induced swelling was calculated as the difference between before and after the challenge. Detailed protocols are described in the text or in the legend to the Fig. relating to each experiment.

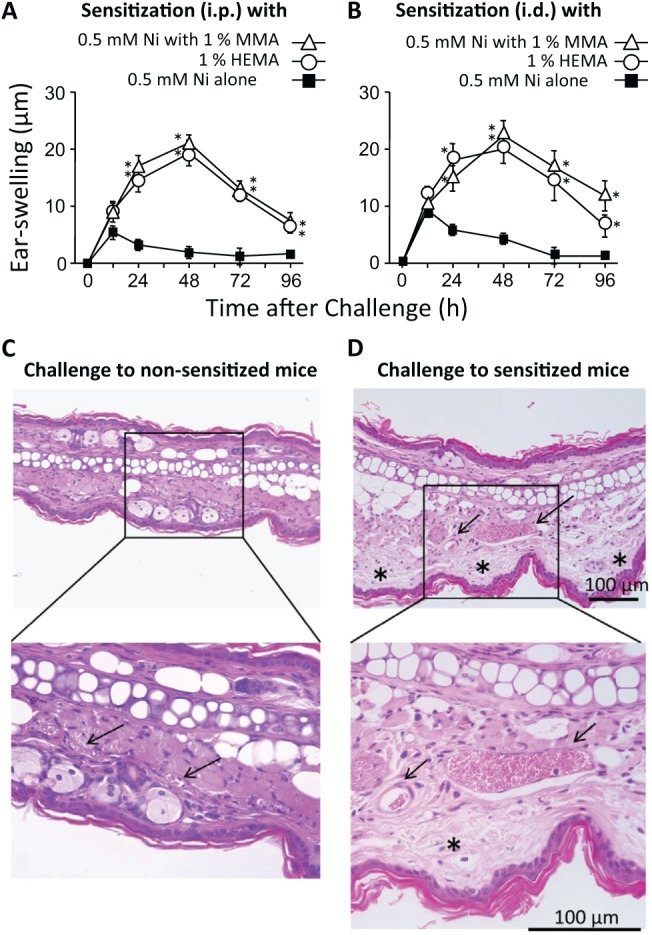

Figure 2.

Adjuvant effects of RMs in the establishment of Ni-AD. (A, B) Effects on allergic ear-swelling. A solution containing 0.5 mM NiCl2 alone or a solution containing 0.5 mM NiCl2 and either 1% MMA or HEMA was injected (20 µL/ear, i.d. or 250 µL/mouse, i.p.), and 10 days later, the ear-pinnae were challenged with 1 mM NiCl2 (20 µL/ear, i.d.). Each value is the mean ± SD from 6 ears (i.e., 3 mice). *p < .01 vs. 0.5 mM Ni alone at the same time point. (C, D) Histological features of ear-pinna skins that had been injected with NiCl2. (C) Non-sensitized mice were i.d.-injected with 1 mM NiCl2 (20 µL/ear). (D) Mice were sensitized to Ni with an i.p. injection of a solution containing 0.5 mM NiCl2 and 1% MMA (250 µL/mouse). Ten days later, their ear-pinnae were challenged with 1 mM NiCl2 (20 µL/ear). Forty-eight h after that challenge, ears were removed, fixed in 10% formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and evaluated microscopically. Arrows and asterisks represent blood vessels and edema, respectively. The results shown for a given experiment were confirmed by at least 1 additional repetition.

Measurement of IL-1 in Ear-pinnae

IL-1α and IL-1β in ear-pinnae were measured as described previously (Deng et al., 2006, 2012) with ELISA kits for IL-1α (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and IL-1β (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Depletion of Phagocytic Macrophages

Clodronate-encapsulated liposomes (Clo-lipo) have been shown to deplete phagocytic macrophages, but not dendritic cells and neutrophils (Van Rooijen and Sanders, 1994). A suspension of Clo-lipo was prepared by the method devised by Van Rooijen and Sanders (1994) as described previously (Yamaguchi et al., 2006). A suspension of original Clo-lipo was diluted 5-fold with sterile saline and injected intravenously (i.v.) via the tail vein at 100 µL/10 g body weight.

Adoptive Transfer of Spleen Cells

Mice were sensitized with a mixture of NiCl2 and MMA, and 10 days later, 1×106 spleen cells from a sensitized mouse were i.v.-transferred into a non-sensitized mouse. One day after the transfer, the recipient’s ears were challenged with NiCl2.

Statistical Analysis

Experimental values are given as the mean ± SD. The statistical significance of differences was analyzed by a Bonferroni multiple comparison test after analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the aid of InStat software (InStat, Scottsdale, AZ, USA). A p < .01 was considered to indicate significance.

Results

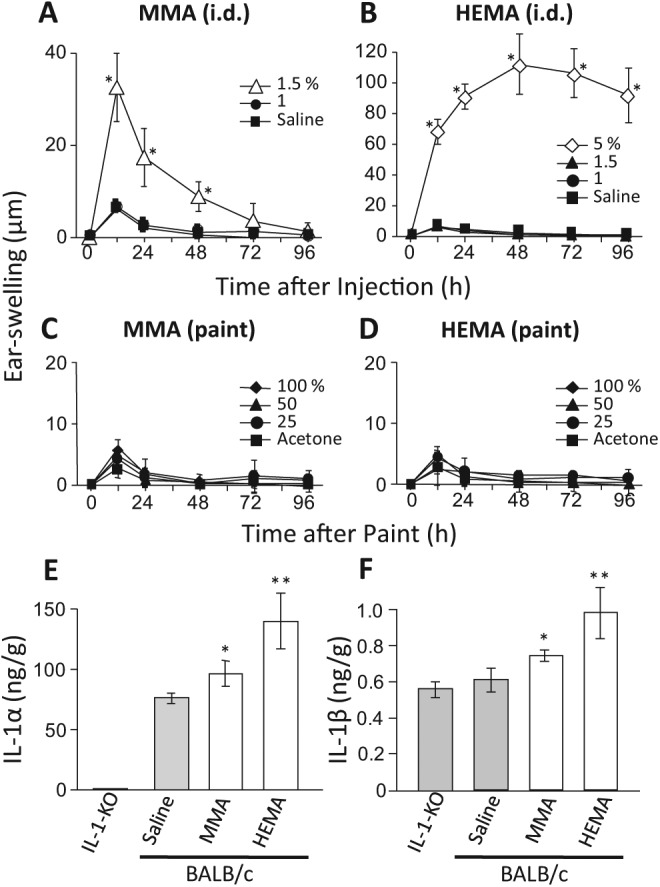

Inflammatory Effects of RMs and RM-induced Production of IL-1

The purpose of the experiments in this section was to search for the optimal concentrations of RMs (i.e., concentrations not causing severe injuries). Incidentally, MMA is less soluble than HEMA; thus, 1% MMA and 5% HEMA are solutions, while 5% MMA is a lyophobic suspension. Intradermal injection of 5% HEMA into ear-pinnae induced ear-swelling at the injection site that was greater and more prolonged than that induced by 1.5% MMA (Figs. 1A, 1B). However, 5% MMA suspension induced a greater and more prolonged ear-swelling than 1% MMA (data not shown). Thus, inflammatory properties may be essentially the same between MMA and HEMA. Painting 100% RMs onto ears was not inflammatory (Figs. 1C, 1D). Although i.p. injection of 5% RMs was very toxic (some mice weakened or died within 30 min of the injection), such toxic effects were not detected for 1% RMs. Because neither MMA nor HEMA at 1% caused any detectable ear-swelling, we used 1% or less of RMs in the following experiments.

Figure 1.

Inflammatory effects of the RMs themselves. (A, B) MMA and HEMA were diluted with saline to the indicated concentrations and injected into ear-pinnae (20 µL/ear, i.d.). (C, D) MMA and HEMA were diluted with acetone to the indicated concentrations and painted onto ear-pinnae (10 µL/each side of the ear). Each value is the mean ± SD from 6 ears (i.e., 3 mice). *p < .01 vs. saline (A, B) or acetone (C, D) at the same time point. (E, F) Effects of RMs on the levels of IL-1α and IL-1β in ear-pinnae. Saline, 1.5% MMA, or 5% HEMA was i.d.-injected into the ear-pinnae of BALB/c wild-type mice (20 µL/ear), and ear-pinnae were taken 24 h later. Values are also shown for non-injected IL-1-KO mice. Each value is the mean ± SD from 4 mice (both ears of a mouse were combined). *p < .05; **p < .01 vs. saline. The results shown for a given experiment were confirmed by at least one additional repetition. Please note that ordinate scales differ between panels A and B, and between panels E and F.

IL-1 reportedly contributes to the development of ACD (Nambu and Nakae, 2010). As shown in Figs. 1E and 1F, either 1.5% MMA or 5% HEMA, when injected into an ear-pinna, significantly increased IL-1α and IL-1β in that ear-pinna. It should also be noted (Figs. 1E, 1F) that: (i) in wild-type mice, IL-1α was constitutively present in ear-pinnae, and its level was much higher than that of IL-1β (ordinate scales differ between Figs.1E and 1F); and (ii) IL-1β levels were similar between IL-1-KO mice and saline-injected wild-type mice. The latter point indicates that ear-pinnae contain a remarkably high level of IL-1β-like unknown protein(s). Thus, an increase in IL-1β, if quite small (e.g., pg level), might be masked by a variation in the level of such protein(s). Indeed, we could not detect a significant elevation of either IL-1α or IL-1β when 1% MMA or 1% HEMA was injected (data not shown). Be all that as it may, however, Figs. 1E and 1F indicate that both MMA and HEMA have the potential to increase IL-1α and IL-1β.

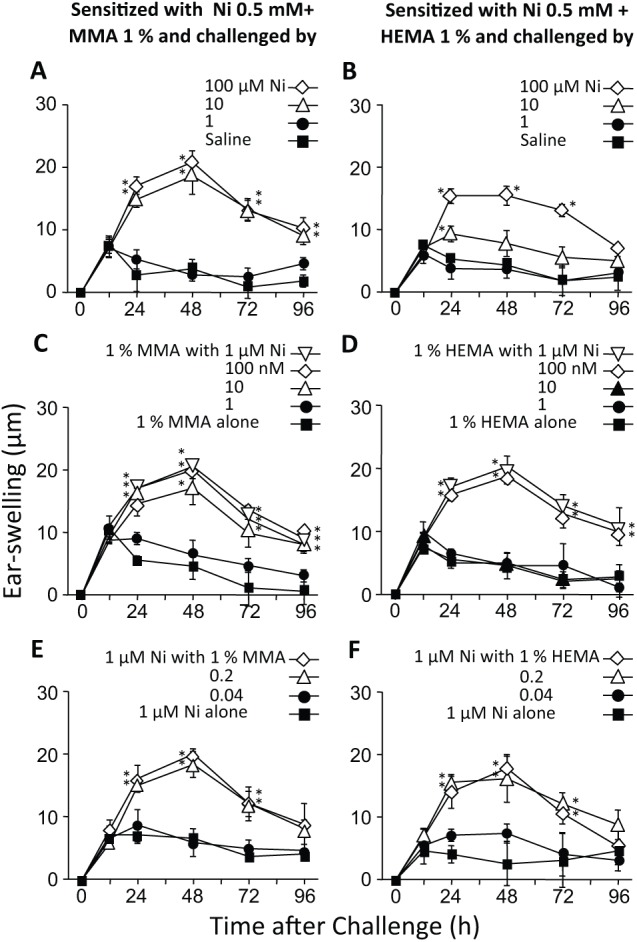

Effects of RMs on the Establishment of Ni-AD

Next, we examined whether RMs have adjuvant effects on Ni-AD. Mice were sensitized to Ni by the injection of a solution containing 0.5 mM NiCl2 and 1% of an RM (250 µL/mouse, i.p., or 20 µL/ear, i.d.), and 10 days later, their ear-pinnae were challenged with 1 mM NiCl2 (20 µL/ear). Mice sensitized with NiCl2 plus an RM by either i.p. or i.d. injection exhibited significant allergic responses, with the peak at 24 to 48 h (Figs. 2A, 2B), while NiCl2 alone was ineffective. Histologically, when compared with non-sensitized mice, sensitized mice showed skin edema and vasodilation, but little infiltration of inflammatory cells (Figs. 2C, 2D). These results indicate that both MMA and HEMA can promote Ni-AD as an adjuvant, but not as an antigen. It is important to note that challenge with an RM (1% ) alone did not induce allergic ear-swelling in mice given the same RM + NiCl2 by i.p. injection at 10 days before the challenge, indicating that, in mice, RMs cannot by themselves induce AD at these concentrations (i.e., RMs cannot be antigens) (Figs. 4C, 4D).

Figure 4.

Effects of RMs on the AD-inducing concentration of Ni at the elicitation step. All mice were sensitized to Ni by i.p. injection of a solution containing 0.5 mM NiCl2 and either 1% MMA or HEMA, and 10 days later, their ear-pinnae were challenged i.d. with NiCl2 alone or with NiCl2 plus an RM. (A, B) Challenge with saline or various concentrations of Ni. (C, D) Challenge with 1% of an RM plus various concentrations of Ni. (E, F) Challenge with 1 µM Ni plus various concentrations of an RM. Each value is the mean ± SD from 6 ears (i.e., 3 mice). *p < .01 vs. saline (A, B), 1% MMA or HEMA alone (C, D), or 1 µM NiCl2 alone (E, F) at the same time point. The results shown for a given experiment were confirmed by at least one additional repetition.

Effects of RMs at the Sensitization Step

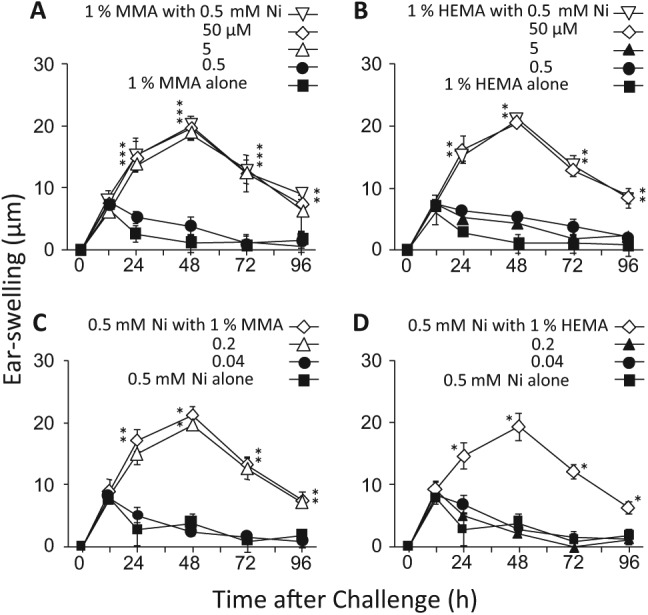

In the following experiments, RMs were i.p.-injected together with NiCl2 at the sensitization step. We previously reported that: (i) mice could be sensitized to Ni by NiCl2 alone at 10 mM (250 µL/mouse, i.p.); and (ii) LPS, given in combination with NiCl2, markedly reduced the AD-inducing concentration of Ni to as little as 10 µM (Kinbara et al., 2011). So, we examined whether RMs might alter the AD-inducing concentration of NiCl2 at the sensitization step. Mice were sensitized with (i) a solution containing 1% MMA or HEMA and one of several concentrations of NiCl2 or (ii) a solution containing 0.5 mM NiCl2 and one of several concentrations of MMA or HEMA (each, 250 µL/mouse, i.p). Ten days later, their ear-pinnae were challenged i.d. with 1 mM NiCl2 (20 µL/ear). As shown in Figs. 3A and 3B, when NiCl2 was given with 1% MMA or HEMA, allergic swelling was induced at 5 µM or 50 µM NiCl2, respectively, indicating that MMA and HEMA reduced the AD-inducing concentration of Ni by factors of 2,000 and 200, respectively, at the sensitization step. As shown in Figs. 3C and 3D, when MMA or HEMA was combined with 0.5 mM NiCl2, allergic swelling was induced by 0.2% MMA or 1% HEMA.

Figure 3.

Effects of RMs on the AD-inducing concentration of Ni at the sensitization step. Solutions containing NiCl2 and either MMA or HEMA at the concentrations indicated in the panels were i.p.-injected into mice, and 10 days later, their ear-pinnae were challenged i.d. with 1 mM NiCl2. In (A) and (B), the concentration of MMA or HEMA was fixed at 1%. In (C) and (D), the concentration of NiCl2 was fixed at 0.5 mM. Each value is the mean ± SD from 6 ears (i.e., 3 mice). *p < .01 vs. 1% MMA or HEMA alone (A, B) or 0.5 mM NiCl2 alone (C, D) at the same time point. The results shown for a given experiment were confirmed by at least 1 additional repetition.

Effects of RMs at the Elicitation Step

Next, we examined whether RMs might alter the AD-inducing concentration of Ni at the elicitation step. In this experiment, mice were sensitized to Ni with a solution of 0.5 mM NiCl2 plus 1% MMA or HEMA (250 µL/mouse, i.p.), and 10 days later, their ear-pinnae were challenged i.d. with (i) NiCl2 alone or saline, (ii) a solution containing 1% MMA or HEMA and one of several concentrations of NiCl2, or (iii) a solution containing 1 µM NiCl2 and one of several concentrations of MMA or HEMA (each, 20 µL/ear). As shown in Figs. 4A and 4B, allergic swelling was induced by NiCl2 at 10 µM, but not at 1 µM, without RMs. However, when combined with 1% MMA or HEMA, allergic swelling was induced at 10 or 100 nM NiCl2, respectively (Figs. 4C, 4D), indicating that MMA and HEMA reduced the AD-inducing concentration of Ni by factors of 1,000 and 100, respectively, at the elicitation step. It should also be noted that when an RM was combined with 1 µM NiCl2, allergic swelling was induced by 0.2% MMA or HEMA (Figs. 4E, 4F).

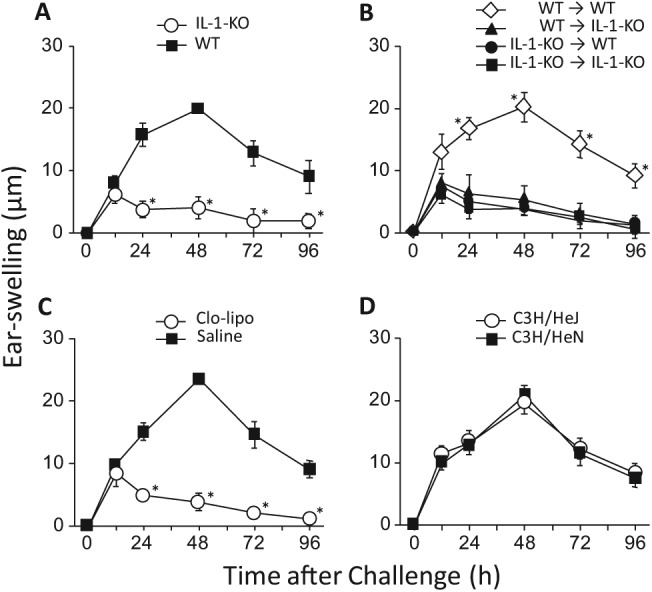

Involvement of IL-1 and Macrophages in the Adjuvant Effects of RMs

We previously suggested that the adjuvant effects of LPS and inflammatory substances on Ni-AD in mice depended on IL-1 and macrophages (Sato et al., 2007; Takahashi et al., 2011). So, here we examined the possible contributions made by IL-1 and macrophages to the adjuvant effects of RMs. In the first experiment, sensitization to Ni was achieved by i.p. injection of a solution containing 0.5 mM NiCl2 plus 1% MMA, and 10 days later, the ear-pinnae were challenged i.d. with 1 mM NiCl2. As shown in Fig. 5A, allergic swelling was marginal in IL-1-KO mice. Similar results were obtained in the second experiment, which differed only in that mice were sensitized with a solution containing 0.5 mM NiCl2 plus 1% HEMA, rather than 1% MMA (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Involvement of IL-1, macrophages, and TLR4 in the adjuvant effects of RMs. All mice were sensitized to Ni by i.p. injection of a solution containing 0.5 mM NiCl2 and 1% MMA, and 10 days later, their ear-pinnae were challenged i.d. with 1 mM NiCl2. (A) Induction of allergic ear-swelling in IL-1-KO and control wild-type (WT) BALB/c mice. *p < .01 vs. WT at the same time point. (B) Cell-transfer between IL-1-KO and WT mice. Ten days after the sensitizing injection to IL-1-KO or WT mice, 1×106 spleen cells from a given mouse were i.v.-transferred into non-sensitized IL-1-KO or WT mice, as indicated in the panel. Then, 24 h after the cell-transfer, the ear-pinnae of the recipients were challenged i.d. with 1 mM NiCl2. *p < .01 vs. the other 3 groups indicated at the same time point. (C) Induction of allergic ear-swelling in macrophage-depleted mice. Clo-lipo or saline was i.v.-injected into WT BALB/c mice (see “Methods”), and 24 h later they were sensitized and challenged as described above. *p < .01 vs. saline at the same time point. (D) Induction of allergic ear-swelling in C3H/HeJ mice (with mutated, non-functional TLR4) vs. control C3H/HeN mice. Each value is the mean ± SD from 6 ears (i.e., 3 mice). The results shown for a given experiment were confirmed by at least 1 additional repetition.

Next, to determine at which step IL-1 is involved, we performed cell-transfer experiments. Ten days after the sensitizing injection had been given to IL-1-KO or wild-type (WT) mice, 1×106 spleen cells were intravenously transferred into non-sensitized IL-1-KO or WT mice. Then, 24 h later, the ear-pinnae of those mice were challenged with 1 mM NiCl2. As shown in Fig. 5B, only cell-transfer from sensitized WT to non-sensitized WT mice induced allergic swelling. In macrophage-depleted mice, no clear allergic swelling was detected (Fig. 5C). Although C3H/HeJ mice lack the functional LPS receptor Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), due to a mutation, their allergic swelling was essentially the same as that seen in control C3H/HeN mice (Fig. 5D). Similar results were obtained in mice sensitized with a solution containing 0.5 mM NiCl2 plus 1% HEMA (data not shown). These results indicate that, for the adjuvant effects of RMs: (i) IL-1 is necessary at both the sensitization and elicitation steps; and (ii) macrophages, but not TLR4, are required. Moreover, analysis of the above data indicated that the adjuvant effects we attributed to RMs are not due to contaminating LPS in the RM preparations.

Discussion

In this study, we confirmed that RMs have inflammatory and cytotoxic effects, and we found that RMs have the potential to increase IL-1α and IL-1β. Inflammatory substances, including chemicals and microbial substances, reportedly exert adjuvant effects in the establishment of the ACD induced by organic haptens (Grabbe et al., 1996) and metallic haptens (Sato et al., 2007; Takahashi et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2011). Here, we found that both MMA and HEMA have an adjuvant effect, in which IL-1 and macrophages are critically important, suggesting that the adjuvant effects of MMA and HEMA are essentially of the same nature. Incidentally, comparison of the present findings with previously reported data (Sato et al., 2007) indicates that 1% RMs are better adjuvants than H2O2 and Complete Freund’s Adjuvant in terms of low toxicity, reproducibility of their adjuvant effects, and ability to reduce the AD-inducing concentration of Ni.

Concerning the mechanism underlying the adjuvant effects of inflammatory substances in Ni-AD, we postulated elsewhere that IL-1 or its related signaling pathways might play an important role (Sato et al., 2007; Takahashi et al., 2011). Indeed, it has been suggested that IL-1 contributes to the development of ACD (Nambu and Nakae, 2010). Recent studies suggested that the adjuvant effects of exogenous substances may be associated with danger signals generated by damage to cells, and the definition of an adjuvant could, in principle, be extended to include preparations capable of inducing a “danger” signal leading to direct/indirect tissue damage (Batista-Duharte et al., 2011; Marichal et al., 2011). Intracellular danger- or pathogen-associated events trigger the formation of inflammasomes within macrophages, leading to activation of caspase-1 and the subsequent release of IL-1β (Contassot et al., 2012). Stimulation of TLRs is known to produce IL-1 (Gabay et al., 2010; Dinarello et al., 2012), and we have shown that various TRRs, as well as TLR4, are involved in adjuvant effects promoting Ni-induced AD (Takahashi et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2011). Here, we found that RMs stimulate the production of both IL-1α and IL-1β in ear-pinnae. Thus, IL-1 may be critically involved in the adjuvant effects of RMs. Interestingly, Ni by itself is known to activate TLR4 in humans, but not in mice (Schmidt et al., 2010), suggesting that even if Ni-ACD in humans involves a mechanism different from that present in mice, stimulation of innate immunity may indeed be involved in promoting Ni-ACD in both species.

Polymethylmethacrylate particles reportedly induce a release of IL-1β in human monocytes and mouse macrophages via inflammasome activation (Burton et al., 2013). In contrast to our finding, earlier findings indicate that HEMA does not stimulate the production of IL-1β in vitro in THP-1 macrophages, human gingival fibroblasts, and keratinocytes (Rakich et al., 1999; Moharamzadeh et al., 2007). On the contrary, RMs evidently inhibit the LPS-induced production of IL-1β by macrophages in vitro (Bolling et al., 2013). Thus, the responses to RMs may differ between the in vivo and in vitro situations. Interestingly, we found that IL-1α is constitutively present in ear-pinnae at a much higher level than IL-1β (Figs. 1E, 1F). Thus, future studies should examine whether RMs can induce IL-1α release and stimulate IL-1β production, as suggested by Gabay et al. (2010) and Dinarello et al. (2012).

Here, we have shown that RMs can markedly reduce the AD-inducing concentration of Ni at both the sensitization and elicitation steps. At the sensitization step, 10 mM NiCl2 was required without RMs. However, 1% of MMA or HEMA reduced this to 5 µM and 50 µM, respectively. At the elicitation step, 10 µM NiCl2 was required without RMs, but 1% of MMA or HEMA reduced this to 10 nM and 100 nM, respectively. In humans, it has been reported that, for Ni, the threshold (amount/cm2 skin) is 10-1,000 times higher at sensitization than at elicitation (Menne, 1994). Our data (here and in Kinbara et al., 2011) are consistent with that conclusion. Many people are thought to be already sensitized to Ni (Fischer et al., 2005), and it has been reported that the concentrations of Ni in sweat, saliva, and blood in humans who have had contact with metals containing Ni are 0.1 to 1 mM, 10 nM to 1 µM, and 1 µM, respectively (Eliades et al., 2003; Liden et al., 2008; Matos de Souza and Macedo de Menezes, 2008; Petoumenou et al., 2009). If our findings in the present mouse model are applicable to humans, the levels of Ni listed above are likely to be sufficient to elicit allergic responses when the individual is exposed to an adequate concentration of an RM.

The present study also indicates that, in the presence of 1 µM NiCl2, even 0.2% RMs can elicit allergic swelling, suggesting that RMs at concentrations below those that are directly inflammatory may promote allergic responses to Ni. In this context, it should be noted that various acrylic resins contain residual RMs (Pfeiffer and Rosenbauer, 2004, and its references).

In conclusion, the present results suggest that: (i) RMs can exert adjuvant effects at either the sensitization or elicitation step in the induction of Ni-AD; (ii) RMs markedly reduce the AD-inducing concentration of Ni; (iii) in the induction of such adjuvant effects, IL-1 is involved at both the sensitization and elicitation steps; and (iv) macrophages are necessary for the adjuvant effects of RMs. Our findings may inform the correct diagnosis of, and appropriate therapeutic strategies against, Ni-ACD. What were previously thought of as “RM-ACD” may need to be viewed instead as ACD caused by Ni or other dental materials that have undergone promotion by the adjuvant effects of RMs.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. R. Timms for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows Grant Number 2410432 (to K.B.) and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 24659835 (to Y.E.).

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aalto-Korte K, Alanko K, Kuuliala O, Jolanki R. (2007). Methacrylate and acrylate allergy in dental personnel. Contact Dermatitis 57:324-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista-Duharte A, Lindblad EB, Oviedo-Orta E. (2011). Progress in understanding adjuvant immunotoxicity mechanisms. Toxicol Lett 203:97-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts CJ, Dearman RJ, Heylings JR, Kimber I, Basketter DA. (2006). Skin sensitization potency of methyl methacrylate in the local lymph node assay: comparisons with guinea-pig data and human experience. Contact Dermatitis 55:140-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolling AK, Samuelsen JT, Morisbak E, Ansteinsson V, Becher R, Dahl JE, et al. (2013). Dental monomers inhibit LPS-induced cytokine release from macrophage cell line Raw264.7. Toxicol Lett 216:130-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton L, Paget D, Binder NB, Bohnert K, Nestor BJ, Sculco TP, et al. (2013). Orthopedic wear debris mediated inflammatory osteolysis is mediated in part by NALP3 inflammasome activation. J Orthop Res 31:73-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contassot E, Beer HD, French LE. (2012). Interleukin-1, inflammasomes, autoinflammation and the skin. Swiss Med Wkly 142:w13590 (e-journal). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Yu Z, Funayama H, Shoji N, Sasano T, Iwakura Y, et al. (2006). Mutual augmentation of the induction of the histamine-forming enzyme, histidine decarboxylase, between alendronate and immuno-stimulants (IL-1, TNF, and LPS), and its prevention by clodronate. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 213:64-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Oguri S, Funayama H, Ohtaki Y, Ohsako M, Yu Z, et al. (2012). Prime role of bone IL-1 in mice may lie in emergency Ca2+-supply to soft tissues, not in bone-remodeling. Int Immunopharmacol 14:658-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA, Simon A, van der Meer JW. (2012). Treating inflammation by blocking IL-1 in a broad spectrum of diseases. Nat Rev 11:633-652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliades T, Trapalis C, Eliades G, Katsavrias E. (2003). Salivary metal levels of orthodontic patients: a novel methodological and analytical approach. Eur J Orthod 25:103-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer LA, Menne T, Johansen JD. (2005). Experimental nickel elicitation thresholds—a review focusing on occluded nickel exposure. Contact Dermatitis 52:57-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay C, Lamacchia C, Palmer G. (2010). IL-1 pathways in inflammation and human diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 6:232-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner LA. (2004). Contact dermatitis to metals. Dermatol Ther 17:321-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves TS, Morganti MA, Campos LC, Rizzatto SM, Menezes LM. (2006). Allergy to auto-polymerized acrylic resin in an orthodontic patient. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 129:431-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabbe S, Steinert M, Mahnke K, Schwartz A, Luger TA, Schwarz T. (1996). Dissection of antigenic and irritative effects of epicutaneously applied haptens in mice. Evidence that not the antigenic component but nonspecific proinflammatory effects of haptens determine the concentration-dependent elicitation of allergic contact dermatitis. J Clin Invest 98:1158-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horai R, Asano M, Sudo K, Kanuka H, Suzuki M, Nishihara M, et al. (1998). Production of mice deficient in genes for interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β, IL-1α/β, and IL-1 receptor antagonist shows that IL-1β is crucial in turpentine-induced fever development and glucocorticoid secretion. J Exp Med 187:1463-1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Kinbara M, Funayama H, Takada H, Sugawara S, Endo Y. (2011). The elicitation step of nickel allergy is promoted in mice by microbe-related substances, including some from oral bacteria. Int Immunopharmacol 11:1916-1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber I, Basketter DA, Butler M, Gamer A, Garrigue JL, Gerberick GF, et al. (2003). Classification of contact allergens according to potency: proposals. Food Chem Toxicol 41:1799-1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinbara M, Sato N, Kuroishi T, Takano-Yamamoto T, Sugawara S, Endo Y. (2011). Allergy-inducing nickel concentration is lowered by lipopolysaccharide at both the sensitization and elicitation steps in a murine model. Br J Dermatol 164:356-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggat PA, Kedjarune U. (2003). Toxicology of methyl methacrylate in dentistry. Int Dent J 53:126-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidén C, Skare L, Vahter M. (2008). Release of nickel from coins and deposition onto skin from coin handling—comparing Euro coins and SEK. Contact Dermatitis 59:31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marichal T, Ohata K, Bedoret D, Mesnil C, Sabatel C, Kobiyama K, et al. (2011). DNA released from dying host cells mediates aluminum adjuvant activity. Nat Med 17:996-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos de Souza R, Macedo de Menezes L. (2008). Nickel, chromium and iron levels in the saliva of patients with simulated fixed orthodontic appliances. Angle Orthod 78:345-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menne T. (1994). Quantitative aspects of nickel dermatitis. Sensitization and eliciting threshold concentrations. Sci Total Environ 148:275-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moharamzadeh K, Van Noort R, Brook IM, Scutt AM. (2007). Cytotoxicity of resin monomers on human gingival fibroblasts and HaCaT keratinocytes. Dent Mater 23:40-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambu A, Nakae S. (2010). IL-1 and allergy. Allergol Int 59:125-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranjpe A, Bordador LC, Wang MY, Hume WR, Jewett A. (2005). Resin monomer 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) is a potent inducer of apoptotic cell death in human and mouse cells. J Dent Res 84:172-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petoumenou E, Arndt M, Keilig L, Reimann S, Hoederath H, Eliades T, et al. (2009). Nickel concentration in the saliva of patients with nickel-titanium orthodontic appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 135:59-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer P, Rosenbauer EU. (2004). Residual methyl methacrylate monomer, water sorption, and water solubility of hypoallergenic denture base materials. J Prosthet Dent 92:72-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakich DR, Wataha JC, Lefebvre CA, Weller RN. (1999). Effect of dentin bonding agents on the secretion of inflammatory mediators from macrophages. J Endod 25:114-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustemeyer T, Frosch PJ. (1996). Occupational skin diseases in dental laboratory technicians. (I). Clinical picture and causative factors. Contact Dermatitis 34:125-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustemeyer T, de Groot J, von Blomberg BM, Frosch PJ, Scheper RJ. (1998). Cross-reactivity patterns of contact-sensitizing methacrylates. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 148:83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg E, Kahu H, Dahlgren UI. (2005). Inflammatogenic and adjuvant properties of HEMA in mice. Eur J Oral Sci 113:410-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N, Kinbara M, Kuroishi T, Kimura K, Iwakura Y, Ohtsu H, et al. (2007). Lipopolysaccharide promotes and augments metal allergies in mice, dependent on innate immunity and histidine decarboxylase. Clin Exp Allergy 37:743-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R, Raghavan B, Müller V, Vogl T, Fejer G, Tchaptchet S, et al. (2010). Crucial role for human Toll-like receptor 4 in the development of contact allergy to nickel. Nat Immunol 11:814-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Kinbara M, Sato N, Sasaki K, Sugawara S, Endo Y. (2011). Nickel allergy-promoting effects of microbial or inflammatory substances at the sensitization step in mice. Int Immunopharmacol 11:1534-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teik-Jin Goon A, Bruze M, Zimerson E, Goh CL, Isaksson M. (2007). Contact allergy to acrylates/methacrylates in the acrylate and nail acrylics series in southern Sweden: simultaneous positive patch test reaction patterns and possible screening allergens. Contact Dermatitis 57:21-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooijen N, Sanders A. (1994). Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods 174:83-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K, Yu Z, Kumamoto H, Sugawara Y, Kawamura H, Takada H, et al. (2006). Involvement of Kupffer cells in lipopolysaccharide-induced rapid accumulation of platelets in the liver and the ensuing anaphylaxis-like shock in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta 1762:269-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]