Abstract

This review provides an update of education and training in family medicine in Singapore and worldwide. Family medicine has progressed much since 1969 when it was recognised as the 20th medical discipline in the United States. Three salient changes in the local healthcare landscape have been noted over time, which are of defining relevance to family medicine in Singapore, namely the rise of noncommunicable chronic diseases, the care needs of an expanding elderly population, and the care of a larger projected population in 2030. The change in the vision of family medicine into the future refers to a new paradigm of one discipline in many settings, and not limited to the community. Family medicine needs to provide a patient-centred medical home, and the discipline’s education and training need to be realigned. The near-term training objectives are to address the service, training and research needs of a changing and challenging healthcare landscape.

Keywords: chronic disease, many settings, paradigm, paradigm shift, patient-centred medical home

INTRODUCTION

This review explores the history of family medicine in Singapore and worldwide, and the challenges that have shaped these developments over time. The discussion segment of this paper details a proposal for a national family medicine vision for 2030.

BACKGROUND

The development and progress of family medicine as a discipline in Singapore is described against the background of family medicine as a worldwide discipline, and against the changing healthcare landscape.

On the world stage, family medicine was recognised as the 20th medical discipline in the United States in 1969. The American Board of Family Practice (ABFP) was set up in that year to oversee the development and maintenance of competence. The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), which was set up in 1947, was reorganised to serve the academic needs of expert Family Physicians.(1)

In Singapore, family medicine began as a discipline with the formation of the College of General Practitioners Singapore in 1971.(2) Formal training in family medicine leading to the membership of the College of General Practitioners Singapore (MCGP) diplomate examination was started the following year, and in 1974, the Diploma was recognised by the Singapore Medical Council as an additional qualification. Today, Singapore has family medicine programmes in all the three medical schools, and the Graduate Diploma in Family Medicine (GDFM) and postgraduate programmes, leading to the Master of Medicine (Family Medicine) (MMed [FM]) degree. As of December 2013, we have 118 doctors who are Fellows of the College of Family Physicians, Singapore (FCFP), 400 holders of the MMed (FM) degree, and 737 holders of the GDFM – serving a population of 5.3 million Singaporeans. Parallel to the ABFP is the Family Physicians Accreditation Board (FPAB) in Singapore.

METHODOLOGY

A literature search was conducted on PubMed for papers describing education and training of family medicine in Singapore and worldwide. The following were the key words used in the search: ‘education’, ‘training’, ‘family medicine’, ‘Singapore’, and ‘future of family medicine’. Citations retrieved were shortlisted by relevance, based on the titles and full text retrieved. They were read by both the authors. A hand search was also conducted for local papers on education and training, government papers and policy speeches on family medicine. Any disagreement regarding the information that was to be included from the papers was resolved by discussion. The results are organised into three parts – the progress of family medicine worldwide, the progress of family medicine in Singapore, and care of a larger Singapore population in 2030.

RESULTS

1. Progress of family medicine as a worldwide discipline

(a) The driving force of family medicine

Family medicine as a discipline was started by general practitioners on both sides of the Atlantic (the United States and the United Kingdom) in the 1960s as a counterculture to post-war medical specialisation, which had resulted in a narrow biomedical focus and fragmentation of care.(3) Vocational training programmes were set up to train the family doctor to be a practitioner of breadth with a holistic approach. The 1970s and 1980s saw welcome growth in the number of doctors who chose family medicine as a career.(4) Family medicine is now deemed to be the discipline that equips its practitioners for the enlarged roles of chronic disease management, intermediate- and long-term care, and coordination of care.

(b) Definition of family medicine

A succinct definition of family medicine that has stood the test of time is: “Family medicine is a discipline concerned with the provision of personal, primary, preventive, comprehensive, continuing, and coordinated healthcare of the individual in relation to his family, community, and his environment.”(5)

(c) Who is the general practitioner/family physician?

There are a number of descriptions of the general practitioner/family physician that have been created over time, such as the Leeuwenhorst definition (1974), WONCA definition (1991) and Olsen definition (2000). They can be found in the WONCA Europe publication on European definition of general practice/family medicine edition 2011.(6) Being a representative description that gives a good overview of who this person is, the WONCA definition of 1991 is quoted below:

The general practitioner or family physician is the physician who is primarily responsible for providing comprehensive care to every individual seeking medical care and arranging for other health personnel to provide services when necessary. The general practitioner/family physician functions as a generalist who accepts everyone seeking care, whereas other health providers limit access to their services on the basis of age, sex or diagnosis.

The general practitioner/family physician cares for the individual in the context of the family, and the family in the context of the community, irrespective of race, religion, culture or social class. He is clinically competent to provide the greater part of their care after taking into account their cultural, socioeconomic and psychological background. In addition, he takes personal responsibility for providing comprehensive and continuing care for his patients.

The general practitioner/family physician exercises his/her professional role by providing care, either directly or through the services of others according to their health needs and resources available within the community he/she serves.

(d) ACGME core competencies

Singapore family medicine, together with other specialties, adopted the American residency system in 2011 (vide infra). As a result, the six generic core competencies of family physicians, as enumerated by the Americans, have been adopted as the framework for training and assessing Singapore’s family physicians. The details of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education-International (ACGME-I, March 2012) can be found in the ACGME-I website (www.acgme-i.org). Briefly, the six competencies are:

Patient care – to be able to provide care that is compassionate, appropriate and effective for the treatment of health problems, and the promotion of health;

Medical knowledge – to be able to demonstrate knowledge and application of patient care;

Practice-based learning and improvement – to be able to investigate and evaluate the care of patients, to appraise and assimilate scientific evidence, and to continuously improve patient care based on continuous self-evaluation and lifelong learning;

Systems-based practice – to demonstrate an awareness of and responsiveness to the larger context of system of healthcare, as well as the ability to effectively call on other resources in the system to provide optimal healthcare;

Interpersonal and communication skills – to demonstrate interpersonal and communication skills that result in the effective exchange of information and collaboration with patients, their families and other health professionals;

Professionalism – to demonstrate a commitment to carrying out professional responsibilities and adherence to ethical principles.

(e) The patient-centred medical home

The recognition by the Americans of the underperformance of their primary care delivery led to the Future of Family Medicine (FFM) Project in 2004(7) and the concept of the patient-centred medical home (PCMH). This is a proposal of what family medicine healthcare delivery should aspire to. This model of care, based on the principles of a personal physician, a physician-directed practice, whole-person orientation, coordinated and integrated care, a focus on quality and safety, enhanced access to care and appropriate payment for care, aims toward good care outcomes. It is a model that seeks to bring the values and principles of family medicine back into focus in an age of subspecialisation and fragmented care.(8) In April 2013, following a two-day symposium, FFM was reviewed and affirmed, and an FFM-version 2 was created with expanded recommendations. It is note-worthy that two tasks were identified for expansion – integrating the patient and family into community in the future healthcare delivery system, and enhancing practice reimbursement.(9)

2. Progress of family medicine as a discipline in Singapore

Parallel to the world stage, family medicine as a discipline has kept pace in Singapore.

(a) Basic medical education

Undergraduate training in family medicine began in 1971 as a one-week attachment to a general practice. In 1987, as a result of a joint memorandum between the College of Family Physicians, Singapore (CFPS) and the National University of Singapore (NUS) Department of Social Medicine and Public Health, family medicine began to be taught in the undergraduate curriculum as a formal discipline. In 1987, the family medicine rotation in the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine in NUS increased from the original one week to two weeks, followed by four weeks in 2001.(10) From 2007, it has been an eight-week rotation incorporating sessions at private GP clinics, polyclinics, rehabilitation and subacute facilities, and palliative care units.

With the establishment of Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School in 2005 and the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine in 2013, family medicine is now an established component of the clinical curricula in all three medical schools. Characteristically, the academic family medicine department in each school is supported by a large base of adjunct family physician faculty from the community.

In light of the great breadth that the discipline encompasses, the undergraduate syllabus focuses on teaching the principles of family medicine and clinical approaches to common problems, and introduces students to practical aspects of consultation, including basic principles of communication and counselling.

(b) Advanced medical training

Vocational training in family medicine began in 1971 with the formation of the College of General Practitioners Singapore. The first College diplomate examinations, the MCGP, were conducted the following year, with the support of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Training was on-the-job, largely driven by self-study and lunchtime talks.(10)

The last diplomate examinations were conducted in 1992, replaced by a new programme instituted in the preceding year, when the first batch of trainees was selected for the MMed (FM) programme. This marked the beginning of a structured Ministry of Health (MOH)-sponsored, hospital-based training programme, marked by a series of clinical specialty rotations relevant to family medicine. In 1993, the batch was presented for the inaugural MMed (FM) examinations, which comprised a theory section, an oral defence of a submitted practice document, and a clinical examination comprising the different clinical fields relevant to family medicine.

Two years later, a separate arm of training was instituted by CFPS (previously the College of General Practitioners Singapore), which allowed doctors in private practice to undergo alternate training leading to the same MMed (FM) examinations. This alternate route became known as Programme B, to distinguish it from Programme A, which was sponsored by MOH.(11)

In 2000, the GDFM was introduced as the entry-level vocational training programme for family medicine. Unlike the MMed FM training, which included hospital rotations, GDFM training is delivered via a combination of distance-learning and small, face-to-face group sessions.(10) Today, the GDFM is the minimum standard required for entry into the Register of Family Physicians.(12) A GDFM graduand may also be presented for the MMed (FM) examination upon completion of an additional period of training.

In 1998, the College inaugurated the Fellowship by Assessment programme. The trainees were MMed (FM) holders who underwent an additional two years of training in clinical practice, pedagogy and research methodology. The first Fellows of the College by Assessment (FCFPS) were presented in 2001.

The postgraduate training landscape saw a sea change in 2011,(13) with the old specialist training system, under which the MMed (FM) Programme A had been run, being replaced by a diametrically different system based on the requirements of the American Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). While the old programme was distinguished by rigorous summative assessment leading to the conferment of the MMed degree, the American-based residency programme is marked by meticulous structure and regular formative assessment leading to a final multiple choice (MCQ) examination and board certification. The first batch of trainees (or residents, as they are now known) will complete their residency in 2014.

In a uniquely Singapore development, residents who successfully complete the residency programme and pass the exit MCQ will have the option of sitting the oral defence and clinical examination components of the MMed (FM) examination, with successful candidates being conferred the MMed (FM) degree in addition to their board certification.(14)

(c) Professional recognition

The Register of Family Physicians, instituted in 2011,(15) serves as a central register of physicians who qualify as such under prescribed rules and is overseen by the FPAB. The prescribed rules cover the scope of the physician’s practice, experience and academic qualifications. As previously mentioned, the minimum standard for entry into the register is the GDFM.

3. Healthcare delivery landscape in Singapore today and in 2030

Three salient changes in the healthcare delivery landscape can be noted over the period 1969–2014. The extrapolation of these changes to 2030 based on available figures is also included here.

(a) Rise of noncommunicable chronic diseases

In 1969, when family medicine was recognised as a discipline in the United States, the world was much younger, and so was Singapore. Noncommunicable chronic diseases were sporadic and acute episodic care was the predominant activity. However, sedentary lifestyles and overconsumption of food have now resulted in increasing obesity and the chronic disease burden.(16)

(b) Care needs of an expanding elderly population

To the rise of noncommunicable chronic diseases must be added medical conditions related to the ageing demographic. Today, 10.5% of Singapore’s population is 65 years and older.(17) By projection, this proportion is expected to hit 18.5% in 2030, which in absolute numbers will amount to 900,000 people aged 65 years and older.(19) Additionally, the proportion of the old-old will double that of the number today. The care needs of the elderly in the years to come were summarised by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong in his National Day Rally Speech in 2009.(18) He said then:

“Government is gearing up our healthcare system for an ageing population…older patients being admitted more frequently. After their acute condition has stabilised, they no longer need intensive treatment but are not well enough to go home.”

“‘More’ itself is not enough. Singapore needs to build up step-down care – community hospitals, nursing homes, general practitioners, and home care…Health Ministry is working on upgrading home care to help caregivers.”

“Another key step is to link up acute hospitals with community hospitals, so that once a patient has stabilised, he can move to the ‘sister’ community hospital and receive ‘slow medicine.’

“The best way to keep healthcare costs down is to maintain healthy lifestyles.”

The elderly demographic faces multiple chronic non-communicable diseases, including dementia, in addition to complex inter-related age-aggravated problems of frailty, deconditioning and falls.

c) Caring for a larger projected population in 2030

The Singapore population in 2030 is projected to be 6.9 million, with a resident population of between 4.2 and 4.4 million, comprising 3.6–3.8 million citizens and 0.5–0.6 million permanent residents.(10) In 2012, the total population was 5.3 million, with a resident population of 3.8 million, requiring the services of 10,225 doctors.(20)

DISCUSSION

1. What has family medicine achieved?

In Singapore, family medicine education and training in 2014 can be considered established. Family medicine is taught in all the three medical schools. The postgraduate family medicine programme consists of the GDFM, the MMed (FM) programme by the ACGME-I Residency and Programme B routes, and advanced training in the Fellowship programme by Assessment conducted by CFPS. Training of trainer courses are also available. Family medicine research is now being established through the scholarly activities required in the ACGME-I MMed (FM) Residency programme, and the Fellowship by Assessment programme.

2. What paradigm shift in education and training is needed?

The vision of family medicine into the future is that of one discipline across many settings, and not simply within the community. To realise this, a mindset shift away from current conventions and constructs is needed in both planning and education, all the while keeping in mind the need for a patient-centric healthcare model. Refinement, elaboration and mainstreaming of this paradigm is an urgent development task. Another imperative is a systematic health literacy programme for every citizen to enable understanding and application of self care principles and optimal use of health resources. Societal recognition of the enlarging role of family physicians in the integration of care needs to be part of health literacy development, as is the need to courageously relook the funding framework of healthcare, whether in the primary, transitional, secondary or other settings. Training of trainers in the art and craft of clinical teaching and leadership is another important item on the agenda. Family medicine leaders need to work with the public, press, policy makers, and fellow professionals to co-create the health delivery system that will optimally serve society in 2030.

(a) Training vision, mission, and objectives

Beyond the near term, given the changing healthcare landscape of Singapore and progress of family medicine education and training, the vision, mission and objectives from a national perspective for Singapore are proposed below.

Vision

The training vision of family medicine to work toward, today and into the future, will be that of family medicine as one discipline across many settings.(21) The trained family physicians of today deals with complex patient problems that require them to be familiar with the care needed in the diverse settings of primary, acute interface, intermediate and long-term care. They need to respond to the healthcare needs of the patients they encounter with the appropriate level of medical expertise, while being mindful that one should seek advice from colleagues where indicated.

The core value of family medicine is person-centredness. This is the driving force that resulted in the formation of the family medicine discipline, which took the world by storm post-World War II. We need a person-centred approach in order to deal with the bio-psycho-social components of ill health and wellness in every person. In this context, a central paradigm of family medicine that has emerged in recent years is the PCMH. This gives a form and structure to the discipline as a counter-culture to the increasing fragmentation and specialisation of medical care into body parts. Family medicine is no longer episodic care; it seeks to create a medical home where continuity of whole-person care takes place.

The paradigm notwithstanding, the peculiarities of family medicine as it is practised in Singapore mean that systemic changes will be necessary before truly continuous care of the whole person can be effected on a national scale. Public and professional perception and expectation, policy decisions, and perhaps most importantly, healthcare financing and subsidy will need to be aligned to create such a person-centred paradigm.

Additionally, there is a need to include in the family medicine vision the development of health literacy in every citizen in order to align all stakeholders (physicians, patients, policy makers and the public) to what needs to be done for the optimisation of health and well-being, and for the appropriate use of healthcare services.

Mission

The training mission of family medicine has been defined by the American Board of Family Medicine, and includes certification, setting of training standards, research, leadership development and collaboration.(22) This is an appropriate framework for the mission of family medicine in Singapore as well, which should be to: (i) improve the quality of medical care available to the public; (ii) establish and maintain standards of excellence in the discipline of family medicine; (iii) improve the standards of medical education for training in family medicine; and (iv) determine by evaluation the fitness of specialists in family medicine who apply for and hold certificates.

Likewise, the individual family physician can apply this framework in his/her personal professional context, by determinedly delivering consistent quality care, committing to continuing advancement and improvement, and subjecting his/her practice to self-audit of standards.

Objectives

The ultimate objective of being a family medicine expert has actually been enunciated by Hippocrates in 600 BC: “Life is short, art is long; the crisis fleeting; experience perilous, and decision difficult. The physician must not only be prepared to do what is right himself, but also to make the patient, the attendants, and externals cooperate.”

In today’s context, this ultimate objective can be broken down into the following five personal training and practice sub-objectives, which are to be tirelessly honed along the journey of becoming expert family physicians: (i) to be an expert diagnostician; (ii) to make appropriate, informed judgement calls; (iii) to organise time to take care of consultation tasks; (iv) to secure the cooperation or partnership of the patient and others in the implementation of clinical management decisions; and (v) to maintain personal well-being, morality and professional integrity.

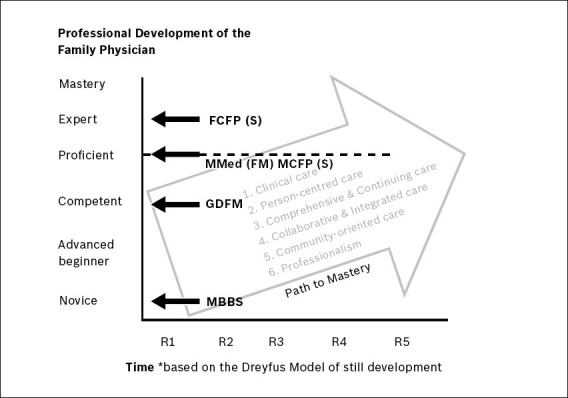

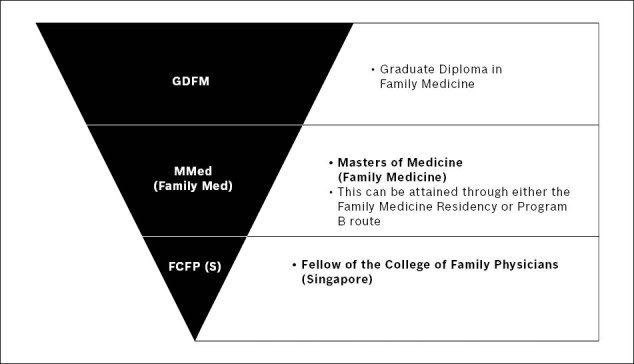

Continuing development of the family physician in Singapore can be envisaged to be at three levels (see Figs. 1 & 2) each with its own objectives:

Fig. 1.

Levels of mastery of family medicine [Source: CFPS, 2013].

Fig. 2.

Levels of mastery in family medicine [Source: CFPS, 2013].

GDFM level – to be competent family physicians who can practice safely in the community setting, with the ability to make right judgement calls;

MMed (FM) level – to be able to proficiently practise family medicine in various settings, as counterparts to their hospital-based specialist colleagues;

Fellowship level – to be able to advise, mentor, supervise and train peers and younger colleagues.

Near-term training objectives

For the near term, we propose that the national service delivery training agenda should include the following: (i) making the patient-centred medical home a reality; (ii) focusing on prevention and on continuity in chronic disease care; and (iii) focusing on prevention, transition and integration of care in the care of the elderly. In tandem with the national service delivery training agenda, the undergraduate education programme needs to be: (i) competency-based; (ii) aligned with the service delivery needs of 2030; and (iii) health literacy-oriented. For postgraduate education, three levels of development provide a systematic framework for meeting current and future family medicine manpower requirements: (i) GDFM; (ii) MMed (FM) by the Residency and Programme B routes; and (iii) Fellowship by Assessment as advanced training.

(b) Training of trainers

The educational and training requirements for family medicine manpower development are vast, and a systematic and integrated plan to address these requirements needs to be urgently devised. These requirements include the following areas: (i) clinical teaching; (ii) preceptorship; (iii) assessment; and (iv) leadership training.

Finally, a training agenda to develop the knowledge and skills required for family medicine scholarly activities needs to be mainstreamed for undergraduates, postgraduates and trainers. The following are vital skills: (i) review and appraisal of evidence-based medical literature; (ii) conduct of case studies, evidence-based topic reviews and original research; and (iii) medical writing.

3. Pausing and taking stock

With a projected increase of 1.6 million people between 2012 and 2030,(19) and using the 2012 figures of 1.9 doctors per 1,000 population, we will need 3,040 more doctors.(20) If we follow the norm of 60% being non-hospital-based doctors, another 1,824 family doctors in addition to the existing numbers, not counting attrition from retirement, will be needed. We will need to train 100 doctors to be family doctors per year till 2030.

This is a good point in our family medicine journey to pause and take stock. There is anecdotal sentiment that the Singapore family doctor, as we have known him for five decades, is bowing out. There are anecdotes of disenfranchised physicians within and without the established system. There is much coffee-shop talk of work load, work-life balance of doctors and changes in the practice landscape. There is an east wind coming, it appears. It is thus vital to build a framework that will support a cleaner, better, and stronger structure in the sunshine when the storm has cleared.(23)

4. Limitation of this paper

This paper is limited by a paucity of published information with regard to the recent changes in family medicine postgraduate education and assessment, the decentralisation of training under different sponsoring institutions, and the recent addition of two new medical schools in Singapore.

CONCLUSION

In Singapore, family medicine as a discipline has progressed much since 1971, but much more needs to be done. The training vision of family medicine is to work toward one discipline across many settings. The near-term training objectives need to address the service, training and research needs of a changing and challenging healthcare landscape.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The views expressed in this article are purely that of the authors’.

REFERENCES

- 1.ABFM [online]; [Accessed January 26 2014]. American Board of Family Medicine. History of the Specialty. Available at: https: //www.theabfm.org/about/history.aspx . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goh LG. From counterculture to integration: The Family Medicine story. Singapore Fam Physician. 2001;27:11–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephen GG. Family medicine as counterculture. 1979. Fam Med. 1998;30:629–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor RB. The promise of family medicine: history, leadership and the Age of Aquarius. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19:183–90. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Primary health care: Main terminology [online]; 2004. [Accessed March 10 2014]. World Health Organization Regional office for Europe. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Health-systems/primary-health-care/main-terminology. [Google Scholar]

- 6.WONCA Europe. The European Definition of General Practice / Family Medicine – Edition. 2011. [Accessed January 26 2014]. Available at: http://www.woncaeurope.org/sites/default/files/documents/Definition_3rd_ed_2011_with_revised_wonca_tree.pdf .

- 7.Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, et al. The Future of Family Medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(Suppl 1):S3–32. doi: 10.1370/afm.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Paediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association. Joint Principles of the Patient-Centred Medical Home March. 2007. [Accessed January 29 2014]. Available at: http://www.acponline.org/running_practice/delivery_and_payment_models/pcmh/demonstrations/jointprinc_05_17.pdf.

- 9.Doohan NC, Duane M, Harrison B, Lesko S, DeVoe JE. The Future of Family Medicine version 2.0: reflections from Pisacano scholars. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27:142–50. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.01.130219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong TY, Cheong SK, Koh GCh, Goh LG. Translating the family medicine vision into educational programme in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:421–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong TY, Koh GCh, Lee EH, Cheong SK, Goh LG. Family medicine education in Singapore: a long-standing collaboration between specialists and family physicians. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:132–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Family Physicians Accreditation Board, Ministry of Health. Becoming a Family Physician. Entry Criteria for Family Physician Accreditation [online] [Accessed March 10 2014]. Available at: http://www.healthprofessionals.gov.sg/content/hprof/fpab/en/leftnav/becoming_a_family_physician/criteria_for_family_physician_accreditation/routes_of_entry.html .

- 13.Wong TY, Chong PN, Chng SK, Tay EG. Postgraduate family medicine training in Singapore--a new way forward. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2012;41:221–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Family Medicine Examination Committee. Family Medicine Examination Committee Communication 2013. [Personal communication] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singapore Medical Council. Registration for Family Physicians [online] [Accessed March 10 2014]. Available at: http://www.healthprofessionals.gov.sg/content/hprof/smc/en/leftnav/announcement/registration_forfamilyphysicians.html .

- 16.Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health. National Health Survey 2010, Singapore. [Accessed March 10, 2014]. Available at: http://www.moh.gov.sg/content/dam/moh_web/Publications/Reports/2011/NHS2010%20-%20low%20res.pdf .

- 17.Department of Statistics Singapore. Population Trends 2013. [Accessed March 10 2014]. Available at: http://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/publications_and_papers/population_and_population_structure/population2013.pdf .

- 18.The Prime Minister's Office, Singapore. Transcript of National Day Rally Speech 2009 [online] [Accessed January 26 2014]. Available at: http://www.news.gov.sg/public/sgpc/en/media_releases/agencies/pmo/transcript/T-20090819-1.html .

- 19.National Population and Talent Division, The Prime Minister's Office, Singapore. A Sustainable Population for a Dynamic Singapore. Population White Paper. [Accessed January 28, 2014]. Available at: http://population.sg/whitepaper/resource-files/population-white-paper.pdf .

- 20.Singapore Health Facts 2012 [online]; [Accessed January 25, 2014]. Ministry of Health Singapore. Available at: http://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/statistics/Health_Facts_Singapore.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheong PY. Family Medicine - One Discipline, Many Settings. The College Mirror. 2013;39:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 22.About ABFM [online]; [Accessed March 10, 2014]. American Board of Family Medicine. Available at: https: //www.theabfm.org/about/index.aspx . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conan Doyle A. United Kingdom: John Murray; 1917. His Last Bow: Some Reminiscences of Sherlock Holmes. [Google Scholar]