Abstract

Hemopericardium is a common finding at autopsy, but it may represent a challenge for the forensic pathologist when the etiopathological relationship in causing death is requested. Hemopericardium and cardiac tamponade can be evaluated in living people using radiological techniques, in particular computer tomography (CT). Only a few studies are reported in literature involving post-mortem (PM) cases, where PMCT imaging has been used in order to investigate acute hemopericardium, and they have shown a good accuracy of this technique. Here we report a case involving a 70-year-old white male found dead on the beach, with a medical history of hepatitis C and chronic hypertension with a poor pharmacological response. A PMCT was performed about 3 h after the discovery of the body. The PMCT examination showed an intrapericardial aortic dissection associated to a periaortic hematoma, a sickle-shaped intramural hematoma, a false lumen, and a hemopericardium consisting in fluid and clotted blood. In this case, the PMCT was able to identify the cause of death, even though a traditional autopsy was required to confirm the radiological findings. PMCT is a reliable technique, which in chosen cases, can be performed without the need for a traditional autopsy to be carried out.

Keywords: Hemopericardium, Cardiac tamponade, Aortic dissection, Computer tomography

1. Introduction

Hemopericardium is an effusion of blood into the pericardial sac and it is due to heart disease (heart rupture as a consequence of necrosis or traumas) or to an intrapericardial aortic rupture. In both cases, death may occur as a result of cardiac tamponade due to the accumulation of blood in the pericardium, which leads to an obstructive shock. As the external pressure on the heart increases, the distending or transmural pressure (external-intracavitary pressure) decreases and consequently the intracavitary pressure rises for compensation, leading to an impaired venous return and an elevation of the venous pressure. If the external pressure is so high to exceed the ventricular pressure during diastole, diastolic ventricular collapse and a cardiac arrest may occur. The obstructive shock results in a moderate/severe cyanosis of the face and neck.[1]–[3]

During the last few years, with the introduction of post-mortem computer tomography (PMCT), a valuable contribute has been given to forensic investigations in making, contributing and supporting the diagnosis of several violent and natural causes of death, leading to the introduction of this technique in some offices of forensic sciences as a standard procedure before the traditional autopsy and in sporadic cases even to substitute it. In this paper, a case of death due to cardiac tamponade as a consequence of hemopericardium is reported, in which PMCT was useful in order to understand the dynamic and cause of death, before the post-mortem examination.

2. Case Report

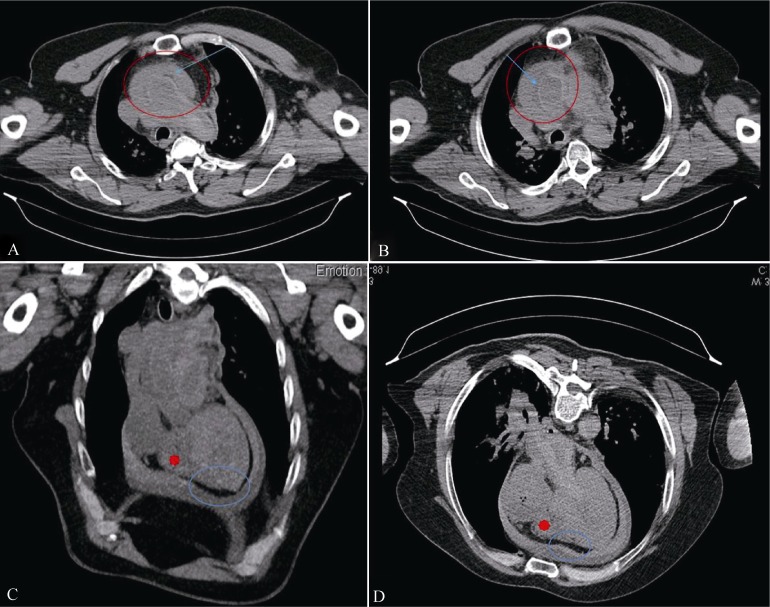

A 70-year-old white male was found dead on the beach. The body was still warm and no signs of trauma or other injuries were found. He had a medical history of hepatitis C and hypertension with a poor pharmacological response. Before the autopsy a PMCT examination was performed about 3 h after the discovery of the corpse. The reconstruction interval was 1 mm. Multi-slice CT scanning took roughly 10 min. The obtained DICOM scans were rendered in 2D and 3D images using the open source software OsiriX on a MaxOSX® computer. A board certified radiologist interpreted all radiological images. The PMCT report was available before the autopsy examination and showed an intrapericardial aortic dissection together with a periaortic hematoma, a sickle-shaped intramural hematoma and a false lumen. A hemopericardium was also shown, consisting in fluid and clotted blood, which differentiated to each other because of their densities (Figure 1). Even before the traditional postmortem examination, we were able to declare death due to a cardiac tamponade as a consequence of hemopericardium in a type-A aortic dissection according to Stanford classification.

Figure 1. PMCT scans results.

(A): A hypodense area compared with the lumen (blue arrow in the red circle); (B): a false lumen together with an intramural hematoma displayed as a hyperdense area (blue arrow in the red circle); and (C & D): a hemopericardium consisting in fluid blood (blue circle) and clotted blood (red asterisk). PMCT: post-mortem computer tomography.

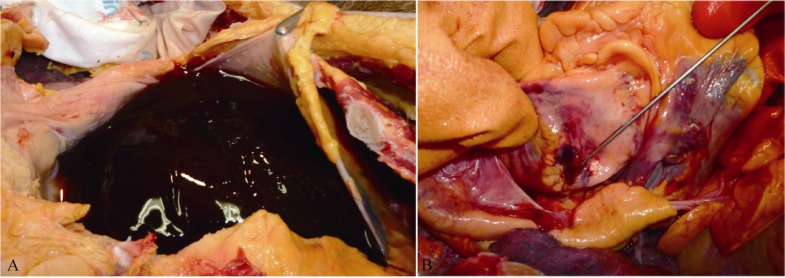

At the external examination of the body, no signs of trauma were observed. At the autopsy examination, the features observed by the PMCT scans were totally confirmed. On opening the pericardial sac, a cardiac tamponade was present, consisting in a large size hematoma of clotted blood (800 g) and fluid blood (500 g) (Figure 2A). After a block dissection of the heart together with the ascendant aorta, and a careful dissection of the soft tissues of these anatomical structures, an intrapericardial aortic dissection was found (Figure 2B). All the other organs were unremarkable. The histological examination confirmed the presence of aortic dissection and the site of rupture. Toxicological analysis was negative for drugs of abuse, alcohol and other medications.

Figure 2. Autopsy examination.

(A): The presence of the hemopericardium confirmed the PMCT findings when the pericardial sac was opened; (B): site of aortic dissection (indicated by the probe) involving the ascending aorta in its intrapericardial tract. PMCT: post-mortem computer tomography.

3. Discussion

Aortic dissection is by far the most common and serious condition affecting the aorta. Among these pathologies, the ascendant aortic dissection is the most severe condition that may lead to death in a large number of cases, due to the rapidity of the pathological process. The dissection seems to be strictly related to the cystic medial necrosis, a disorder of large arteries, in particular the aorta, characterized by an accumulation of basophilic ground substance in the media with cyst-like lesions. It usually results from chronic hypertension or from rare conditions (such as Marfan's syndrome, aortic coarctation and bicuspid aortic valve). Whatever the mechanism, it is often brought about by degenerative changes in the aortic wall. Since dissection can involve any aortic segment, the disease can manifest itself through a variety of clinical presentations. In fact, when aortic dissection occurs, aortic branches occlusion may happen. In case of dissections of the ascending aorta, the major aortic branches are occluded, resulting in rapidly fatal complications such as cardiac tamponade, major stroke, or massive myocardial infarction.[4]–[6]

If the fluid occurs rapidly (as may occur after trauma or myocardial rupture), as little as 100 mL can cause tamponade.[7] However, the data reported in literature about the amount of blood able to cause death in acute cases are discordant. Frequently, a quantity of 300–400 mL of blood is found in bodies, even if other reports show a greater volume.[8]–[10]

Aortic dissections can be classified by the location of the tear. According to the Stanford classification,[4]–[6] there are two types of aortic dissections: (1) type A aortic dissections involve the ascending aorta and frequently needs emergency surgery. These types of dissections are often found in subjects with a history of high blood pressure, an ascending aortic aneurysm, connective tissue disorder (e.g., Marfan Syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve, or a family history of aortic dissections). (2) Type B aortic dissections do not involve the ascending aorta (involvement of aortic arch without involvement of the ascending aorta is considered type B or simply called arch dissection but is not a type A dissection). These types of dissections may be managed conservatively with blood pressure and heart rate control. Therefore, the case here reported can be classified as a type A aortic dissection. The evaluation in living subjects of cardiac tamponade due to a hemopericardium, using diagnostic imaging techniques with special regard to the CT, allows a good interpretation of the anatomy and the pathology of the pericardium.[11],[12]

In post-mortem investigations, few studies have used PMCT imaging to investigate cardiac tamponade in the last decade[9],[13]–[16] (Table 1) and the results obtained show the feasibility of using the PMCT technique to diagnose haemopericardium and cardiac tamponade in cadavers.

Table 1. Studies reported in literature during the last decade, in which PMCT imaging was used to investigate cardiac tamponade.

| Study | Cases number | Age/Sex | Causes | PMCT findings | Autopsy findings |

| Filograna, et al[13] (2014) | 1 | 49 yrs / M | Non-operable aortic aneurysm dissection (Stanford type A) | Dissected aneurysm of the ascending aorta | No autopsy |

| Filograna, et al[14] (2013) | 1 | 65 yrs / M | Hypertension | Aneurysm of the ascending aortaPericardial effusion | No autopsy |

| Huang, et al[15] (2012) | 1 | 30 yrs / M | Car accidentChest trauma | Haemopericardium | No autopsy |

| Ebert, et al[9] (2012) | 15 | Mean age: 46 yrs / (10 M, 5 F) | Lethal trauma (8) Rupture after myocardial infarction (6) Sepsis (1) |

Pericardial effusion | Autopsy confirmation |

| Shiotani, et al[16] (2004) | 30 | From 40 to 101 yrs / (15 M, 15 F) | Natural causes | Pericardial effusion Large pericardial Effusion |

No autopsy |

F: female; M: male; PMCT: post-mortem computer tomography.

It must also be considered that since in in-vivo imaging of aortic dissections the contrast-enhancement of the lumen is essential to detect critical radiological features, it is possible that these findings can be missed during a standard PMCT without contrast. To overcome this problem, a PMCT-angiography can be carried out, even if the use of this technique is currently limited. Regarding this topic,

Bello, et al.[17] have recently reported a case involving a 72 year-old man, in which multi-phase PMCT angiography was helpful in defining the diagnosis, detecting a hemopericardium and the ruptured wall situated in the posterior part of the left ventricle. The autopsy was then performed, totally confirming the CT Angiography findings.

In the present case, the subject had a medical history of chronic hypertension with a poor pharmacological response. This pathology was the trigger for the development of the ascendant aortic dissection resulting in a rapid cardiac tamponade, causing the man's death. According to the Italian jurisdiction, when a subject (even a foreigner) dies in Italy and questions concerning the cause and the manner of death arise, the Prosecutor requires the forensic pathologist to perform a full postmortem examination, consisting in external and internal examination. The family of the deceased cannot refuse the autopsy.

Because the deceased was Jewish, his family objected to the autopsy in observance of their religion, however, the Prosecutor ordered that the autopsy had to be carried out, notwithstanding the fact that the PMCT was able to demonstrate the cause of death, because it was not considered a technique reliable and accurate enough to determine the cause of death. According to this conclusion, the autopsy was performed, confirming the CT findings.

According to us, a PMCT examination in always necessary in all cases of violent deaths, such as gunshot wounds, asphyxia, sharp force injuries, etc.[18],[19] In such cases, the PMCT must be considered as a support to the traditional postmortem examination that must always to be carried out. In case of natural deaths, a PCMT should always be performed whenever possible, because it sometimes can give a clue regarding the cause of death, making the autopsy virtually not mandatory (in the Countries where it is allowed). For example, regarding to sudden natural deaths in the absence of traumas or in deaths due to infectious diseases, the real effectiveness of a full autopsy should be evaluated taking into account the potential risks for the pathologist during the autopsies. In these cases, a full PMCT examination, together with an accurate clinical history of the deceased, exhaustive investigative reports concerning the circumstances surrounding the death and toxicological analyses from biological samples collected at the external examination, is a valuable tool that can alone led to determine the cause of death. The forensic pathologist, on the basis of the available information, to his own experience and also to the specific Justice issues concerning the case, should be able to decide when and why the PMCT alone is enough to clarify the cause of death or if a full postmortem examination is required.

Furthermore, ethical and religious issues should be taken into consideration in such cases, when the traditional autopsy is not really necessary. A PMCT approach in these cases can be useful to reduce the manipulation of the bodies, allowing families to observe their own religions.

However, despite the rapid growth of forensic radiology, we must underline that a multidisciplinary approach in suspicious cases is always required. On the one hand, the PMCT should become a standard in forensic practice in order to be performed whenever possible. On the other hand, if that happens, it must be avoided that the PMCT led the pathologist to focus his attention only on the main radiological findings, giving less importance to other features, hence missing possible secondary diseases. Specifically, a PMCT-guided postmortem examination must always to be carried out as fully as possible.

In conclusion, PMCT should be considered as an essential support to the traditional autopsy of violent deaths (and not its replacement), becoming as important as histopathological and toxicological analyses, in order to allow the forensic pathologist to have an overall view of all the features concerning the case. In natural deaths, conversely, when no specific issues arise, the PMCT alone should be virtually considered as a valuable technique to clarify the cause of death, to reduce potential risks for the pathologist and also to overcome ethical and religious issues.

References

- 1.Spodick DH. Acute cardiac tamponade. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:684–690. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy PS, Curtiss EI, Uretsky BF. Spectrum of hemodynamic changes in cardiac tamponade. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:1487–1491. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90540-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beloucif S, Takata M, Shimada M, et al. Influence of pericardial constraint on atrioventricular interactions. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:125–134. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.1.H125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleischmann D, Mitchell RS, Miller DC. Acute aortic syndromes: New insights from electrocardiographically gated computed tomography. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;20:340–347. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease: executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1509–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagan PG, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA. 2000;283:897–903. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.7.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forauer AR, Dasika NL, Gemmete JJ, et al. Pericardial tamponade complicating central venous interventions. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:255–259. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000058329.82956.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karger B, Niemeyer J, Brinkmann B. Physical activity following fatal injury from sharps pointed weapons. Int J Legal Med. 1999;112:188–191. doi: 10.1007/s004140050230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebert LC, Ampanozi G, Ruder TD, et al. CT based volume measurement and estimation in cases of pericardial effusion. J Forensic Leg Med. 2012;19:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aghayev E, Christe A, Sonnenschein M, et al. Postmortem imaging of blunt chest trauma using CT and MRI: comparison with autopsy. J Thorac Imaging. 2008;23:20–27. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e31815c85d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oyama N, Oyama N, Komuro K, et al. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the pericardium: anatomy and pathology. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2004;3:145–152. doi: 10.2463/mrms.3.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Restrepo CS1, Lemos DF, Lemos JA, et al. Imaging findings in cardiac tamponade with emphasis on CT. Radiographics. 2007;27:1595–1610. doi: 10.1148/rg.276065002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Filograna L, Flach PM, Bolliger SA, et al. The role of post-mortem CT (PMCT) imaging in the diagnosis of pericardial tamponade due to hemopericardium: A case report. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2014;16:150–153. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filograna L, Hatch G, Ruder T, et al. The role of post-mortem imaging in a case of sudden death due to ascending aorta aneurysm rupture. Forensic Sci Int. 2013;228:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang P, Wan L, Qin Z, et al. Post-mortem MSCT diagnosis of acute pericardial tamponade caused by blunt trauma to the chest in a motor-vehicle collision. Rom J Leg Med. 2012;20:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiotani S, Watanabe K, Kohno M, et al. Postmortem computed tomographic (PMCT) findings of pericardial effusion due to acute aortic dissection. Radiat Med. 2004;22:405–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bello S, Neri M, Grilli G, et al. Multi-Phase Post-Mortem CT-Angiography (MPMCTA) is a very significant tool to explain cardiovascular pathologies. A sudden cardiac death case. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2014;20:1419–1430. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maiese A, Gitto L, De Matteis A, et al. Post mortem computed tomography: Useful or unnecessary in gunshot wounds deaths? Two case reports. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2014;16:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maiese A, Gitto L, dell'Aquila, et al. When the hidden features become evident: The usefulness of PMCT in a strangulation-related death. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2014;16:364–366. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]