Abstract

BACKGROUND

While N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) has a strong relationship with incident cardiovascular disease (CVD), few studies have examined whether NT-proBNP adds to risk prediction algorithms, particularly in women.

OBJECTIVES

We sought to evaluate the relationship between NT-proBNP and incident CVD in women.

METHODS

Using a prospective case-cohort within the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study, we selected 1,821 incident cases of CVD (746 myocardial infarctions, 754 ischemic strokes, 160 hemorrhagic strokes, and 161 other cardiovascular [CV] deaths) and a randomly selected reference cohort of 1,992 women without CVD at baseline.

RESULTS

Median (interquartile range) levels of NT-proBNP were higher at study entry among incident cases (120.3 [68.1 to 219.5]) than among controls (100.4 [59.7 to 172.6]; p <0.0001). Women in the highest quartile of NT-proBNP (≥ 140.8 ng/l) were at 53% increased risk of CVD versus those in the lowest quartile after adjusting for traditional risk factors (1.53 [1.21 to 1.94]; p-trend: <0.0001). Similar associations were observed after adjustment for Reynolds Risk Score (RRS) covariables (1.53 [1.20 to 1.95] p-trend <0.0001); the association remained in separate analyses of CV death (2.66 [1.48 to 4.81]; p-trend <0.0001), myocardial infarction (1.39 [1.02 to 1.88] p-trend = 0.008), and stroke (1.60 [1.22 to 2.11), p-trend <0.0001). When added to traditional risk covariables, NT-proBNP improved the c-statistic (0.765 to 0.774; p = 0.0003), categorical net reclassification (0.08; p <0.0001), and integrated discrimination (0.0105; p <0.0001). Similar results were observed when NT-proBNP was added to the RRS.

CONCLUSIONS

In this multiethnic cohort of women with numerous cardiovascular events, NT-proBNP modestly improved measures of CVD risk prediction.

Keywords: biomarkers, multiethnic, prevention, risk prediction

Assays for B-type natriuretic peptides (NPs) have gained widespread acceptance as tools for diagnosis and risk stratification in patients complaining of shortness of breath and chest pain (1–3). NPs also have demonstrated consistent association with adverse cardiovascular outcome in stable patients with and without established cardiovascular disease (CVD) (4). However, few studies conducted in general populations have analyzed the association of NPs with CVD, specifically in women, and only a handful have comprehensively examined whether NPs improve clinical risk prediction in general populations (5–8).

Women have higher levels of NPs than men (5, 9–13) and yet lower absolute risk for CVD than men of similar age and risk factor burden (14). Obesity is also well known to affect NP levels in both whites and blacks (15, 16) and differential patterns of adipose tissue in men and women may alter the relationship between NPs and cardiovascular disease, as has been observed for other CVD risk markers (17). Reportedly, NP concentrations are lower in blacks than whites (18, 19). In fact, while the relationship between NPs and cardiovascular risk appears consistent across several studies including general populations, many studies either include only men (6, 20), report the number of CVD events in women but do not report the association between NPs and CVD in women and men separately (7, 11), or have too few events in women to analyze (13). Data on the relationship between NPs and CVD in women of nonwhite race/ancestry are even scarcer.

To better understand the relationship between NPs and cardiovascular risk in a broad population of women we constructed a prospective, case-cohort study within the multiethnic Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), and measured NT-proBNP concentrations at baseline in 1,821 women who subsequently had a major cardiovascular event (myocardial infarction [MI], stroke, or CV death) and a reference cohort of 1,992 women. We then tested whether the addition of NT-proBNP concentrations to traditional CVD risk markers, such as those included in the Framingham CVD Score (21) or Reynolds Risk Score (RRS) (22), improved our ability to predict cardiovascular risk.

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION

This study includes participants in the WHI Observational Study (WHI-OS) and the WHI extension study. The WHI-OS is a multiethnic cohort of 93,676 post-menopausal women, aged 50 to 79 years at recruitment, who were enrolled between 1994 and 1998 at 40 sites across the United States. The racial/ethnic composition of the WHI-OS is representative of U.S. women in the included age groups. Of the 93,676 women in the WHI-OS, 71,872 had no prior history of MI, stroke, peripheral artery disease, venous thromboembolism, or cancer. Of those, 60,890 had baseline blood samples available for analysis.

Baseline information on medical history, health behaviors, and blood pressure (BP) measurements were collected by the WHI-OS clinical centers. Information on diabetes, smoking, family history of CVD, and medication use were self-reported.

OUTCOMES

The primary endpoint for this study was a composite of major CVD, defined as the occurrence of nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or CV death. Chronic heart failure (HF) was not included as part of the primary cardiovascular endpoint. CVD outcomes were self-reported and physician verified via review of cardiac biomarkers, electrocardiograms, and medical records as previously described (23). Coronary heart disease was defined as nonfatal MI and coronary death, stroke as a fatal or nonfatal persistent neurologic deficit of at least 24 hours duration that was sudden in onset and compatible to obstruction or rupture of a cerebral artery. Strokes were classified as ischemic or hemorrhagic on the basis of brain imaging reports. Deaths were classified on the basis of death certificates, autopsy reports, and medical records.

SAMPLE SELECTION

A prospective case-cohort design was employed. Two thousand women with incident CVD were selected for inclusion. We first included all incident cases among black (n = 200), Hispanic (n = 53), and Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 55) women, as well as 55 cases from women of unknown or other race/ethnicity groups. The remaining 1,637 cases were randomly selected from among 2,370 cases of incident CVD in white women. A reference cohort of approximately 2,000 women was selected using the same eligibility criteria and frequency matched by race/ethnicity and age (in 5-year groups). Women who developed CVD during follow-up were eligible to be selected as reference cohort members, but women who had prevalent CVD at enrollment, including transient ischemic attack, HF, or cardiovascular surgery, or who had no valid measurement of NT-proBNP (n = 2), were excluded from both the case and reference groups. After these exclusions, the final sample included 1,821 cases of CVD and a reference cohort of 1,992 women, of whom 132 were also cases.

LABORATORY ANALYSIS

Plasma samples were collected and stored centrally at −70 °C and assayed for NT-proBNP, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), and glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) (the latter only among patients with diabetes) in a core laboratory certified by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Lipid Standardization Program. NT-proBNP was measured using an electrochemiluminescent immunoassay from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We estimated means and proportions in both the cases and the reference cohorts in a crude analysis. Overall population characteristics were estimated using inverse probability weights in PROC SURVEYMEANS and SURVEYFREQ in SAS 9.2 to reflect the sampling in the total WHI cohort. Because the numbers in the full sample were known, our stratified sampling enabled us to mimic or recapture the characteristics of the full WHI cohort using reweighting by sampling frequency. The numbers of women among the cases and reference cohort who were above the age-specific NT-proBNP thresholds for acute HF in patients with dyspnea (>900 ng/l for ages 50 to 75 and >1,800 ng/l for ages >75) were compared using the chi-square test (3). Cox proportional hazards models were used to test the association of NT-proBNP with incident CVD in all women, regardless of race/ethnicity. Previously described methods for proportional hazards regression in case-cohort samples, with appropriate weighting, were used (24–26). Using quartiles derived from all women selected for the reference cohort, the association of NT-proBNP with the composite cardiovascular outcome was tested in a series of adjusted models. The risk per 1 standard deviation (SD) unit in Ln-transformed NT-proBNP (Ln-NT-proBNP) also was calculated. The first model, called the “multivariable model,” was adjusted for age and race/ethnicity as well as underlying conditions and medication use (prior diabetes, angina, statin use, and current and past hormone therapy). We then constructed a “multivariable plus traditional risk factor” model that adjusted for covariables from the multivariable model above, plus the traditional risk markers that are included in the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) III risk model (27), the Framingham CVD risk score (21), and the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2013 Pooled Cohort atherosclerotic CVD risk model (28): current smoking; the natural logs of systolic BP, total and HDL cholesterol; and treatment for high BP. We also constructed a “Reynolds Risk Score” model that adjusted for covariables included in the multivariable model plus the variables in the RRS: current smoking; the natural logs of systolic BP, total and HDL cholesterol and hs-CRP; family history of premature MI; and HbA1c among women with diabetes (22). In sensitivity analyses, body mass index (BMI) was included with the other covariables in the multivariable plus traditional risk factor and RRS models. We repeated the adjusted proportional hazards analysis for CV death, incident fatal/nonfatal MI,incident fatal/nonfatal stroke and in analyses stratified by baseline characteristics. The Bonferroni-corrected p value for evidence of statistically significant interaction in the stratified analysis was p < 0.00278 (p = 0.05/18 tests).

In order to directly compare the performance of the multivariable plus traditional risk factor model and RRS model with and without NT-proBNP, we calculated the c-statistics for each model and the integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) (29). To determine whether NT-proBNP improved our ability to classify women into 10-year CVD risk categories of <5%, 5% to <10%, and 10% to <20%, and >20%, we calculated the net reclassification improvement (NRI) (28). Survival methods were used throughout (30, 31), and measures were reweighted to reflect the distribution in the overall cohort. Statistical tests of discrimination measures were performed using bootstrap samples. We also performed sensitivity analyses by including diabetes, angina, statin use, and current and past hormone therapy with the RRS covariables.

RESULTS

A total of 1,821 women who developed CVD during follow-up met the criteria for inclusion as cases, while 1,992 women met criteria for inclusion in the reference cohort. In total, there were 746 fatal/nonfatal MIs, 754 fatal/nonfatal ischemic strokes, 160 fatal/nonfatal hemorrhagic strokes, and 161 other CV deaths. The median (interquartile range) follow-up time was 9.9 (8.0 to 11.6) years.

The study population’s baseline characteristics presented both as crude analyses and in analyses reweighted to reflect sampling from the WHI population are displayed in Table 1. As anticipated, women who developed CVD during follow-up had higher BMIs, systolic BP, and hsCRP, and lower HDL-C levels. These women were also more likely to be current smokers, use loop diuretics, and have diabetes, a history of angina, or family history of premature MI. In both crude and reweighted analyses, NT-proBNP levels were significantly higher among women who developed incident CVD (each p < 0.0001). In total, there were 8 cases with NT-proBNP concentrations above the age-specific cut points used to diagnose HF in patients with dyspnea (3) compared to only one in the reference cohort (p = 0.004; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparisons of Baseline Characteristics of CVD Cases and Random Cohort, in the Sample and Reweighted to the Total WHI Cohort

| Crude | Reweighted to Population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic* | Cohort (n = 1,992) |

Cases (n = 1,821) |

p value | Cohort | Cases | p value |

| Age, yrs | 67.7 (0.2) | 67.8 (0.2) | 0.11 | 62.7 (0.04) | 67.9 (0.03) | <0.001 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Black race, % | 204 (10.2) | 186 (10.2) | 0.96 | 4207 (7.2) | 186 (7.6) | 0.61 |

| White race, % | 1622 (81.4) | 1489 (81.8) | 0.65 | 49410 (84.7) | 2106 (86.4) | 0.12 |

| Hispanic, % | 57 (2.9) | 50 (2.8) | 0.99 | 2044 (3.5) | 50 (2.1) | 0.02 |

| Asian, % | 54 (2.7) | 50 (2.8) | 0.77 | 1749 (3.0) | 50 (2.1) | 0.05 |

| Other race/unknown race, % | 55 (2.8) | 46 (2.5) | 0.48 | 914 (1.6) | 46 (1.9) | 0.51 |

| Height, cm | 160.9 (0.2) | 160.8 (0.2) | 0.78 | 161.5 (0.3) | 160.9 (0.1) | 0.095 |

| Weight, kg | 70.0 (0.3) | 72.2 (0.4) | <0.0001 | 72.0 (0.6) | 72.1 (0.4) | 0.85 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.9 (0.1) | 27.9 (0.1) | <0.0001 | 27.3 (0.2) | 27.8 (0.1) | 0.057 |

| Current smoking, % | 96 (4.8) | 161 (8.8) | <0.0001 | 3310 (5.7) | 207 (8.5) | 0.009 |

| Hormone therapy, % | ||||||

| Current | 830 (41.7) | 719 (39.6) | 0.12 | 27986 (48.0) | 977 (40.1) | <0.0001 |

| Past | 286 (14.4) | 276 (15.2) | 0.53 | 7051 (12.1) | 375 (15.4) | 0.013 |

| Blood pressure, mm Hg | ||||||

| Systolic | 129.7 (0.4) | 135.5 (0.4) | <0.0001 | 126.3 (0.5) | 135.3 (0.4) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic | 74.3 (0.2) | 75.8 (0.2) | <0.0001 | 74.8 (0.3) | 75.7 (0.2) | 0.012 |

| Anti-hypertensive medication use, % | 529 (26.6) | 658 (37.7) | <0.0001 | 13091 (22.5) | 909 (37.3) | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 230.9 (1.0) | 228.0 (1.0) | 0.047 | 231.0 (1.5) | 228.4 (1.0) | 0.17 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 56.8 (0.4) | 51.1 (0.4) | <0.0001 | 56.6 (0.5) | 51.1 (0.4) | <0.0001 |

| Cholesterol-lowering medication, % | 178 (8.9) | 176 (9.7) | 0.55 | 4359 (7.5) | 236 (9.7) | 0.037 |

| Statin use, % | 161 (8.0) | 134 (7.4) | 0.30 | 3921 (6.7) | 180 (7.4) | 0.54 |

| Loop diuretic use, % | 48 (2.4) | 71 (3.9) | 0.002 | 1188 (2.0) | 92 (3.8) | 0.006 |

| hsCRP, mg/l† | 2.3 (1.0, 5.0) | 3.0 (1.4, 4.9) | <0.0001 | 2.4 (1.0, 5.2) | 3.0 (1.3, 6.0) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes, % | 93 (4.7) | 189 (10.4) | <0.0001 | 2151 (3.7) | 238 (9.8) | <0.0001 |

| HbA1c, % (if diabetic) | 7.4 (0.2) | 7.9 (0.1) | 0.013 | 7.5 (0.2) | 7.9 (0.1) | 0.0099 |

| Angina, % | 55 (2.8) | 83 (4.6) | 0.004 | 1314 (2.3) | 112 (4.6) | 0.0007 |

| Family history of early MI, % | 352 (17.7) | 483 (22.1) | 0.0002 | 11413 (19.6) | 552 (22.7) | 0.042 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/ml † | 100.4 (59.7, 172.6) | 120.3 (68.1, 219.5) | <0.0001 | 82.7 (50.9, 140.8) | 122.4 (69.4, 219.7) | <0.0001 |

| Abnormal NT-proBNP, %§ | 17 (0.9) | 49 (2.7) | <0.0001 | 312 (0.5) | 65 (2.7) | <0.0001 |

Continuous variables are presented as mean (SE) and discrete variables presented as proportions N (%) unless otherwise specified

Median (interquartile ratio). Test is based on natural logs.

NT-proBNP >900 ng/l for ages 50 to 75 and >1,800 ng/l for ages >75

BMI = body mass index; CVD = cardiovascular disease; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c; HDL = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; hsCRP = high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; MI = myocardial infarction; NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; WHI = Women’s Health Initiative.

The relationship between NT-proBNP levels and baseline characteristics of the reference cohort are displayed in Online Supplement Table 1. Increasing levels of NT-proBNP were associated with increasing age, systolic BP, HDL-C; increased antihypertensive and hormone therapy use; and lower levels of BMI and hsCRP. No significant relationship was observed between NT-proBNP levels and total cholesterol, current smoking, diabetes, angina, loop diuretic use, or family history of premature MI. We observed a higher proportion of white women in the higher quartiles of NT-proBNP and the opposite pattern for black women (each p < 0.0001).

Increasing levels of NT-proBNP showed a positive relationship with incident CVD (Table 2) that remained significant after adjusting for covariables included in the traditional risk factor or RRS models. For example, relative to the women in the lowest quartile of NT-proBNP, women in the highest quartile were at 53% increased risk of CVD after adjusting for either the traditional risk factor covariables (HR [hazard ratio]: 1.53, 95% CI [confidence interval]:1.21 to 1.94; p-trend < 0.0001) or the RRS covariables (HR: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.20 to 1.95; p-trend < 0.0001). A linear increase in CVD risk was observed for women in the third and fourth quartiles relative to the first quartile, but the second quartile did not clearly fit this pattern (Table 3). Adding BMI or loop diuretic use to the multivariable models presented in Table 2 did not change the relationship between NT-proBNP and incident CVD (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Association of NT-proBNP with Incident CVD

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) by Quartile of NT-proBNP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 |

Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | p for trend |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) per 1- SD* unit increase in Ln-NT-proBNP |

p Value | |

| NT-proBNP range, ng/l | <50.9 | 50.9 to < 82.7 | 82.7 to < 140.8 | ≥ 140.8 | |||

| Age and race/ethnicity adjusted | 1.00 | 0.91 (0.72–1.14) | 1.18 (0.95–1.45) | 1.55 (1.26–1.92) | <0.0001 | 1.36 (1.26–1.48) | <0.0001 |

| MV adjusted† | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.74–1.17) | 1.28 (1.03–1.59) | 1.62 (1.30–2.02) | <0.0001 | 1.39 (1.28–1.51) | <0.0001 |

| MV + traditional risk factor adjusted§ | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.71–1.17) | 1.29 (1.02–1.63) | 1.53 (1.21–1.94) | <0.0001 | 1.37 (1.25–1.49) | <0.0001 |

| MV + RRS adjusted¶ | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.73–1.21) | 1.29 (1.01–1.64) | 1.53 (1.20–1.95) | <0.0001 | 1.36 (1.24–1.49) | <0.0001 |

The standard deviation (SD) of natural logarithm transformed NT-proBNP is 0.838.

Multivariable- (MV−) adjusted model is adjusted for age and race/ethnicity, prior diabetes, angina, statin use, and current and past hormone therapy.

MV + traditional risk factor adjusted is adjusted for the covariables in the MV model, plus current smoking and the natural logs of systolic blood pressure, total and HDL cholesterol, and blood pressure treatment.

MV + Reynolds Risk Score (RRS) adjusted: Adjusted for the covariables in the MV model, plus current smoking, the natural logs of systolic blood pressure, total and HDL cholesterol, hsCRP, family history of premature MI, and HbA1c among women with diabetes.

ATP III = Adult Treatment Panel III; CI = confidence interval; Ln-NT-proBNP = Ln-transformed NT-proBNP; MV = multivariable; RRS = Reynolds Risk Score; SD = standard deviation; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

TABLE 3.

Association of NT-proBNP with Cardiovascular Mortality, Incident Fatal and Nonfatal MI, and Incident Fatal and Nonfatal Stroke

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) by Quartile of NT-proBNP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | p for trend | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) per 1-SD* unit increase in Ln-NT- proBNP |

p Value | |

| NT-proBNP range, ng/l | <50.9 | 50.9 to < 82.7 | 82.7 to < 140.8 | ≥ 140.8 | |||

| Cardiovascular mortality | |||||||

| MV adjusted† | 1.00 | 0.84 (0.42–1.68) | 1.79 (0.99–3.24) | 2.95 (1.67–5.20) | <0.0001 | 1.95 (1.65–2.31) | <0.0001 |

| MV + traditional risk factor adjusted§ | 1.00 | 0.81 (0.40–1.62) | 1.78 (0.98–3.26) | 2.82 (1.57–5.05) | <0.0001 | 1.89 (1.59–2.26) | <0.0001 |

| MV + RRS adjusted¶ | 1.00 | 0.82 (0.41–1.66) | 1.81 (0.99–3.32) | 2.66 (1.48–4.81) | <0.0001 | 1.80 (1.51–2.14) | <0.0001 |

| MI (fatal and nonfatal) | |||||||

| MV adjusted† | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.70–1.27) | 1.25 (0.94–1.65) | 1.48 (1.12–1.96) | <0.0001 | 1.33 (1.21–1.47) | <0.0001 |

| MV + traditional risk factor adjusted§ | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.69–1.28) | 1.25 (0.93–1.67) | 1.41 (1.05–1.89) | 0.004 | 1.28 (1.16–1.42) | <0.0001 |

| MV + RRS adjusted¶ | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.70–1.33) | 1.26 (0.93–1.70) | 1.39 (1.02–1.88) | 0.008 | 1.26 (1.13–1.40) | 0.0002 |

| Stroke (fatal and nonfatal) | |||||||

| MV adjusted† | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.72–1.25) | 1.21 (0.93–1.57) | 1.72 (1.33–2.22) | <0.0001 | 1.40 (1.28–1.53) | <0.0001 |

| MV + traditional risk factor adjusted§ | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.70–1.25) | 1.22 (0.93–1.61) | 1.60 (1.21–2.09) | <0.0001 | 1.35 (1.22–1.48) | <0.0001 |

| MV + RRS adjusted¶ | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.71–1.27) | 1.21 (0.92–1.60) | 1.60 (1.22–2.11) | <0.0001 | 1.34 (1.22–1.48) | <0.0001 |

The SD of natural logarithm transformed NT-proBNP is 0.838.

MV-adjusted model is adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, prior diabetes, angina, statin use, and current and past hormone therapy.

MV + traditional risk factor adjusted: Adjusted for the covariables in the MV model plus current smoking and the natural logs of systolic blood pressure, total and HDL cholesterol, and blood pressure treatment.

MV + Reynolds Risk Score (RRS) adjusted: Adjusted for the covariables in the MV model, plus current smoking, the natural logs of systolic blood pressure, total and HDL cholesterol, hsCRP, family history of premature MI, and HbA1c among women with diabetes.

When CV deaths and coronary and cerebrovascular events were considered separately, NT-proBNP was associated with both any cardiovascular death and fatal/nonfatal MI and fatal/nonfatal stroke (Table 3). The risk of CV death was more than two-and-a-half times higher for those in the highest quartile of NT-proBNP relative to those in the lowest quartile, even after adjusting for the RRS covariables (HR: 2.66, 95% CI: 1.48 to 4.81; p-trend < 0.0001). Relative to those in the lowest quartile, these women were also at increased risk of fatal/nonfatal MI in models adjusted for traditional risk factor covariables (HR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.05 to 1.89; p-trend = 0.004) and RRS covariables (HR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.88; p-trend = 0.008). The risk of fatal/nonfatal stroke was also increased with a HR of 1.60 (95% CI: 1.21 to 2.09; p trend < 0.0001) after adjustment for traditional risk factor covariables and a HR of 1.60 (95% CI: 1.22 to 2.11; p-trend < 0.0001) after adjusting for RRS covariables. Further adjustment for BMI did not alter these risk estimates substantially (data not shown).

Associations between NT-proBNP concentrations and incident CVD stratified by a number of subgroups are displayed in Online Supplement Table 2. In general, the adjusted association between Ln-NT-proBNP and incident CVD was consistent across subgroups. The increase in the risk of incident CVD per 1 SD unit of Ln-NT-proBNP among past hormone therapy users (HR: 1.71, 95% CI: 1.00 to 2.91; p = 0.049) appeared to be larger than among current (HR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.17 to 1.70; p = 0.0003) or never users (HR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.09 to 1.50; p = 0.003), but these apparent differences did not reach statistical significance (p-interaction = 0.03) after correcting for the number of comparisons (Bonferroni-corrected p < 0.00278).

When NT-proBNP was added to the multivariable plus traditional risk factor CVD prediction algorithm, we observed a small but statistically significant improvement in the c-index, with a difference (95% CI) in c-statistics of 0.009 (0.009 to 0.010; p = 0.0004) and improved classification of women into 10-year CVD risk categories of <5%, 5% to <10%, 10% to <20%, and >20% (NRI 95% CI 0.059 [0.030 to 0.089], p < 0.0001; Table 4). Statistically significant improvements in the category-less NRI and IDI were also observed (Table 4). When NT-proBNP was added to an algorithm including the RRS covariates, we observed a small but statistically significant improvement in the c-index (difference 0.009, 95% CI: 0.005 to 0.013; p = 0.0001) and improved classification of women into the same 10-year CVD risk categories (NRI 95% CI 0.033 [0.002 to 0.062], p = 0.03) (Table 6). Both the category-less NRI and IDI showed statistically significant improvements after adding NT-proBNP to the RRS covariates (Table 4). Reclassification tables, weighted by cohort sampling, are displayed in Online Supplement Table 3 (for the multivariable plus traditional risk factor model) and Online Supplement Table 4 (for the RRS). When reweighted to reflect the sampling of the WHI-OS, the addition of NT-proBNP to the traditional risk factor covariables would reclassify 7,036 women, 4,246 (60%) correctly, of a possible 58,216 women. The addition of NT-proBNP to the RRS would reclassify 6,283 women (out of 58,216), 5,209 (82.9%) correctly.

TABLE 4.

Changes to 10-year CVD Risk Prediction Statistics after Adding NT-proBNP to Existing Risk Prediction Models

| MV + Traditional Risk Factor Covariables |

Reynolds Risk Score (RRS) Covariables |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MV + Traditional Risk Factor |

MV + Traditional Risk Factor + NT- proBNP |

p Value* |

RRS | RRS + NT- proBNP |

p Value † |

|

| C-statistic (95% CI) | 0.770 (0.760–0.779) | 0.779 (0.769–0.789) | 0.0004 | 0.768 (0.757–0.776) | 0.776 (0.765–0.785) | 0.0001 |

| Net reclassification improvement (95% CI) | - | 0.059 (0.030, 0.089) | <0.0001 | - | 0.033 (0.002–0.062) | 0.03 |

| Category-less net reclassification improvement (95% CI) | - | 0.103 (0.020, 0.183) | 0.02 | - | 0.097 (0.013–0.19) | 0.03 |

| Integrated discrimination improvement (95% CI) | - | 0.0102 (0.0055, 0.016) | 0.0001 | - | 0.0080 (0.0039–0.012) | 0.0002 |

Comparison of the performance of MV plus traditional risk factor covariables plus NT-proBNP concentrations versus multivariable plus traditional risk factor covariables without NT-proBNP concentrations. The multivariable and traditional risk factor covariables were age, race/ethnicity, prior diabetes, angina, statin use, current or past hormone therapy, current smoking and the natural logs of systolic blood pressure, total and HDL cholesterol, and blood pressure treatment.

Comparison of the performance of Reynolds Risk Score (RRS) covariables plus NT-proBNP concentrations to RRS performance without NT-proBNP concentrations. The RRS covariables were age, race/ethnicity, current smoking, the natural logs of systolic blood pressure, total and HDL cholesterol, hsCRP, family history of premature MI, and HbA1c among women with diabetes.

In sensitivity analyses that added prior diabetes, angina, statin use, and current and past hormone therapy to the RRS covariables used in the primary reclassification analysis, these results did not differ substantially (Online Supplement Table 5).

DISCUSSION

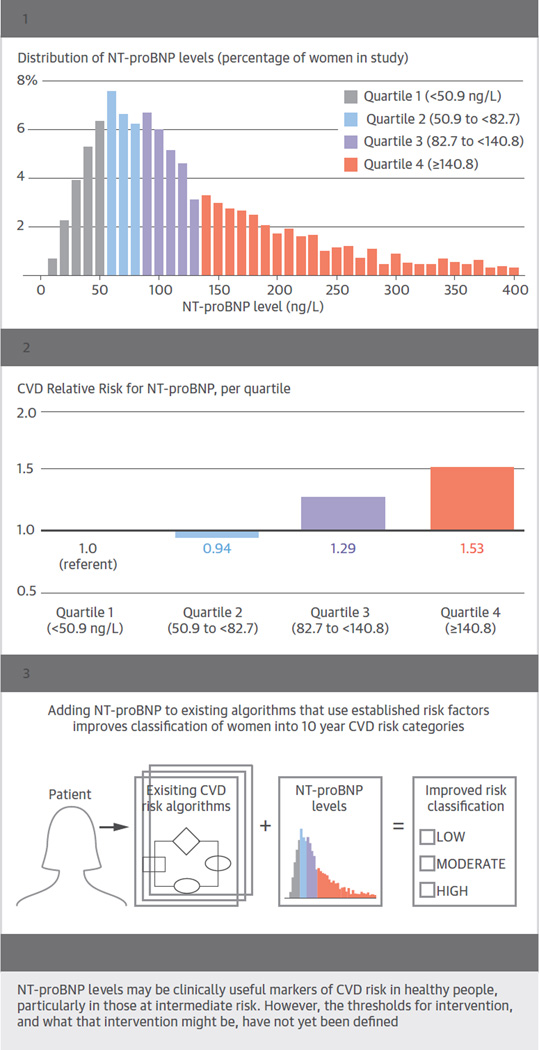

In this prospective case-cohort study, including more than 1,800 cases of incident CVD in women, we observed a positive association between baseline NT-proBNP concentrations and the occurrence of a first major CV event, defined as an MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death (Central Illustration). While a number of studies have reported this relationship in primary prevention or general populations, this study is the first to conduct a detailed evaluation of this relationship in women. This association was evident for CV mortality, fatal/nonfatal MI, and fatal/nonfatal stroke, and was consistent across a number of high- and low-risk subgroups. Finally, we observed that NT-proBNP concentrations, when added to the covariables included in either the traditional risk factor or Reynolds Risk Score risk prediction algorithms, significantly improved our ability to identify women at increased risk of developing CVD in this multiethnic population (Central Illustration).

We believe these results are of scientific and clinical relevance for various reasons. First, the approximately 1,800 CV events included in this study represent the largest number of events used to evaluate NPs in a primary prevention population, regardless of the participants’ sex. By comparison, a 2009 meta-analysis of NPs and CVD gathered approximately 1,000 events in primary prevention populations (4). Second, while there is consistent epidemiologic evidence that NP levels associate with future CV events in general populations, most of the published studies include few events in women (11–13), or women were not included in the study population (6, 20). Women are known to have higher baseline concentrations of NPs than men (5, 11–13) and yet have a lower risk of CVD at a given age and risk factor burden, as well as a lower lifetime risk of CVD (14, 32). In spite of these differences, women in our study who had NT-proBNP concentrations in the highest quartile (≥140.0 ng/l) were at more than 50% increased risk for the composite CV outcome when compared to those in the lowest quartile, even after adjusting for race and other important covariables included in established risk models.

These results are also consistent with prior work that has examined the association of NPs and cardiovascular endpoints that exclude HF and/or atrial fibrillation (4). Indeed, we observed significant associations between NT-proBNP and CV death from any cause, as well as MI and stroke, an observation that again is consistent with prior work in other cohorts (4, 11–13, 33). The mechanism of the association between NPs and incident CVD is not known, although it seems likely that natriuretic peptides are measuring a component of cardiovascular risk that is either different from or incompletely accounted for by traditional CVD risk markers. Higher NT-proBNP concentrations may be evidence of subclinical myocardial ischemia (34, 35), ventricular wall stress, neurohormonal activation, hypertension, or other conditions. The consistency of the association with NT-proBNP and incident stroke raises the possibility that elevated concentrations may identify individuals with unrecognized and/or silent atrial fibrillation, who might then be at high risk of cardioembolic stroke, as was hypothesized in a recently published study from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort (33). We also note that the vast majority of women in the WHI had NT-proBNP concentrations well below the threshold that would prompt consideration of HF in patients with dyspnea (3).

Finally, we observed that adding NT-proBNP to traditional risk factors and the RRS improves CVD risk prediction in this multiethnic cohort of women. Only a handful of studies have tested the ability of NPs to improve CV risk prediction in primary prevention cohorts. The results have been mixed, with some reporting improvements alone or in combination with other markers (5, 6, 8, 36), and others reporting no improvement (7). Because women have a lower prevalence of CVD for a given age distribution, and because traditional risk factors have superior risk prediction performance for women than men, even biomarkers with an independent association with CVD (such as NT-proBNP) may not improve upon the performance of existing risk prediction algorithms (37). In spite of these challenges, in our study NT-proBNP offered small but statistically significant improvements in the c-statistic, the categorical NRI, the continuous NRI, and the IDI when added to the traditional risk factor and RRS covariables. While it is difficult to compare improvements in model performance across populations, we observed improvements in the c-statistic for major cardiovascular events that are similar in magnitude to those seen for cardiac troponin in the ARIC study (38), and close but somewhat smaller than those achieved with a multimarker score in a European cohort and in the Framingham Heart Study (8, 36). The improvements are smaller than those seen with coronary calcium scans in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (39).

While statistically significant, the improvements in measures of risk prediction we observed with NT-proBNP were relatively modest. Natriuretic peptides may merit consideration as useful markers of CVD risk in those for whom a decision to begin preventive statin therapy is otherwise unclear, much like other adjunctive measures of cardiovascular risk (40). However, the therapeutic response to an elevated NP level in an otherwise healthy individual is not clear. While using natriuretic peptides as a tool to identify those who might benefit from statins would be one possible clinical strategy, no trial has tested this approach. Indeed, elevated NP levels may identify abnormalities in other biological pathways that are best addressed with other classes of agents, rather than statins. For example, a recent trial of aggressive renin angiotensin and beta blockade as compared to standard care in patients with type 2 diabetes and an elevated NT-proBNP (>125 ng/l) suggested a benefit for aggressive care (41).

Strengths of our study include its prospective nature, inclusion of a large number of women from a multiethnic cohort, and a large number of CV events. Limitations include the fact that the generalizability of our findings may be limited to women and the absence of any measures of renal function in the WHI. While renal function is likely to be a confounder of the relationship between NT-proBNP and incident CVD, we note that measures of renal function are not included as risk predictors in either ATP III, the Framingham CVD risk score, the 2013 ACC/AHA pooled cohort model, or in the RRS, in spite of having been considered for inclusion in the latter (21, 22, 27, 28).

In summary, NT-proBNP showed positive association with MI, stroke, and CV death in this large, prospective case-cohort study with more than 1,800 first cardiovascular events. This association was observed for both fatal and nonfatal coronary and cerebrovascular events, when considered separately, and was consistent across several subgroups. Finally, when we added NT-proBNP to risk prediction models using traditional risk factors or the Reynolds Risk Score covariables, we saw consistent, statistically significant improvements in the models’ ability to correctly classify women into 10-year categories of CV risk.

Supplementary Material

FIGURE. Central Illustration. Improving Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Risk Prediction in Women by Adding NT-proBNP Levels to Existing Algorithms.

NT-proBNP concentrations were measured in 1821 women with incident cardiovascular disease (746 myocardial infarction, 754 ischemic stroke, 160 hemorrhagic stroke, 161 cardiovascular death) and a randomly selected reference subcohort of 1992 women without cardiovascular disease at baseline. Panel 1 depicts the distribution of NT-proBNP concentrations in the reference subcohort. Panel 2 shows the risk of the combined cardiovascular endpoint (myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death) according to increasing quartiles of NT-proBNP. Panel 3 depicts the addition of NT-proBNP to traditional risk factors in risk prediction algorithms, which leads to modest but statistically significant improvements in the ability to predict 10-year cardiovascular disease risk.

PERSPECTIVES.

Competency in Medical Knowledge

Measurement of plasma natriuretic peptide levels can help identify heart failure among patients with dyspnea. In healthy men and women, natriuretic peptide levels correlate with risks of future myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death.

Translational Outlook

Additional work is needed to define the risk prediction thresholds for blood levels of specific natriuretic peptides, and to identify preventive interventions that improve cardiovascular outcomes for those with natriuretic peptide levels above those thresholds.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This project was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Broad Agency Announcement contract number HHSN268200960011C. The Women’s Health Initiative program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, and the US Department of Health and Human Services through contracts N01WH22110, 24152, 32100-2, 32105-6, 32108-9, 32111-13, 32115, 32118-9, 32122, 42107-26, 42129-32, and 44221.

Dr. Everett has received investigator-initiated grants from Roche Diagnostics. Dr. Berger has received investigator-initiated grant support from the NIH, the American Heart Association and the Doris Duke Clinical Scientist Award. Dr. Ridker has received research support from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Amgen, and NHLBI and has served as a consultant to Genzyme, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Aegerion, ISIS Pharmaceuticals, Vascular Biogenics, Boeringer, Pfizer, and Merck. Dr. Ridker is listed as a co-inventor on patents held by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital that relate to the use of inflammatory biomarkers in cardiovascular disease that have been licensed to AstraZeneca and Siemens.

Abbreviations

- ATP

Adult Treatment Panel

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- hsCRP

high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- IDI

integrated discrimination improvement

- NP

natriuretic peptide

- NRI

net reclassification improvement

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

- RRS

Reynolds Risk Score

- WHI

Women’s Health Initiative

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

Drs. Manson and Cook have no relevant conflicts to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maisel AS, Krishnaswamy P, Nowak RM, et al. Rapid measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:161–167. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Januzzi JL, Jr, Camargo CA, Anwaruddin S, et al. The N-terminal Pro-BNP investigation of dyspnea in the emergency department (PRIDE) study. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:948–954. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thygesen K, Mair J, Mueller C, et al. Recommendations for the use of natriuretic peptides in acute cardiac care: a position statement from the Study Group on Biomarkers in Cardiology of the ESC Working Group on Acute Cardiac Care. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2001–2006. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Angelantonio E, Chowdhury R, Sarwar N, et al. B-type natriuretic peptides and cardiovascular risk: systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 prospective studies. Circulation. 2009;120:2177–2187. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.884866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsen MH, Hansen TW, Christensen MK, et al. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, but not high sensitivity C-reactive protein, improves cardiovascular risk prediction in the general population. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1374–1381. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zethelius B, Berglund L, Sundström J, et al. Use of multiple biomarkers to improve the prediction of death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2107–2116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melander O, Newton-Cheh C, Almgren P, et al. Novel and conventional biomarkers for prediction of incident cardiovascular events in the community. JAMA. 2009;302:49–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blankenberg S, Zeller T, Saarela O, et al. Contribution of 30 biomarkers to 10-year cardiovascular risk estimation in 2 population cohorts: the MONICA, risk, genetics, archiving, and monograph (MORGAM) biomarker project. Circulation. 2010;121:2388–2397. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.901413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redfield MM, Rodeheffer RJ, Jacobsen SJ, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Burnett JC., Jr Plasma brain natriuretic peptide concentration: impact of age and gender. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:976–982. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Impact of age and sex on plasma natriuretic peptide levels in healthy adults. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:254–258. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02464-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Plasma natriuretic peptide levels and the risk of cardiovascular events and death. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:655–663. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kistorp C, Raymond I, Pedersen F, Gustafsson F, Faber J, Hildebrandt P. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, C-reactive protein, and urinary albumin levels as predictors of mortality and cardiovascular events in older adults. JAMA. 2005;293:1609–1616. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi T, Nakamura M, Onoda T, et al. Predictive value of plasma B-type natriuretic peptide for ischemic stroke: a community-based longitudinal study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207:298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Incidence and prevalence: 2006 chart book on cardiovascular and lung diseases. [Accessed August 14, 2013]; Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/06_ip_chtbk.pdf.

- 15.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Impact of obesity on plasma natriuretic peptide levels. Circulation. 2004;109:594–600. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112582.16683.EA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox ER, Musani SK, Bidulescu A, et al. Relation of obesity to circulating B-type natriuretic peptide concentrations in blacks: the Jackson Heart Study. Circulation. 2011;124:1021–1027. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.991943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta NK, de Lemos JA, Ayers CR, Abdullah SM, McGuire DK, Khera A. The relationship between C-reactive protein and atherosclerosis differs on the basis of body mass index: the Dallas Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1148–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das SR, Drazner MH, Dries DL, et al. Impact of body mass and body composition on circulating levels of natriuretic peptides: results from the Dallas Heart Study. Circulation. 2005;112:2163–2168. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.555573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krauser DG, Chen AA, Tung R, Anwaruddin S, Baggish AL, Januzzi JL., Jr Neither race nor gender influences the usefulness of amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide testing in dyspneic subjects: a ProBNP Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency Department (PRIDE) substudy. J Card Fail. 2006;12:452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laukkanen JA, Kurl S, Ala-Kopsala M, et al. Plasma N-terminal fragments of natriuretic propeptides predict the risk of cardiovascular events and mortality in middle-aged men. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1230–1237. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ridker PM, Buring JE, Rifai N, Cook NR. Development and validation of improved algorithms for the assessment of global cardiovascular risk in women: the Reynolds Risk Score. JAMA. 2007;297:611–619. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.6.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curb JD, McTiernan A, Heckbert SR, et al. Outcomes ascertainment and adjudication methods in the Women's Health Initiative. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:S122–S128. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barlow WE. Robust variance estimation for the case-cohort design. Biometrics. 1994;50:1064–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Therneau TM, Li H. Computing the Cox model for case cohort designs. Lifetime Data Anal. 1999;5:99–112. doi: 10.1023/a:1009691327335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langholz B, Jiao J. Computational methods for case-cohort studies. Comp Stats Data Analysis. 2007;51:3737–3748. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–239. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goff DC, Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2935–2959. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr, D'Agostino RB, Jr, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157–172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. discussion 207-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chambless LE, Cummiskey CP, Cui G. Several methods to assess improvement in risk prediction models: extension to survival analysis. Stat med. 2011;30:22–38. doi: 10.1002/sim.4026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med. 2011;30:11–21. doi: 10.1002/sim.4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berry JD, Dyer A, Cai X, et al. Lifetime risks of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:321–329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Folsom AR, Nambi V, Bell EJ, et al. Troponin T, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, and incidence of stroke: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Stroke. 2013;44:961–967. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadanandan S, Cannon CP, Chekuri K, et al. Association of elevated B-type natriuretic peptide levels with angiographic findings among patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:564–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kragelund C, Gronning B, Kober L, Hildebrandt P, Steffensen R. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and long-term mortality in stable coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:666–675. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang TJ, Wollert KC, Larson MG, et al. Prognostic utility of novel biomarkers of cardiovascular stress: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2012;126:1596–1604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.129437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paynter NP, Everett BM, Cook NR. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction in Women: Is There a Role for Novel Biomarkers? Clin Chem. 2014;60:88–97. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.202796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saunders JT, Nambi V, de Lemos JA, et al. Cardiac troponin T measured by a highly sensitive assay predicts coronary heart disease, heart failure, and mortality in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Circulation. 2011;123:1367–1376. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.005264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeboah J, McClelland RL, Polonsky TS, et al. Comparison of novel risk markers for improvement in cardiovascular risk assessment in intermediate-risk individuals. JAMA. 2012;308:788–795. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014:2889–2934. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huelsmann M, Neuhold S, Resl M, et al. PONTIAC (NT-proBNP Selected PreventiOn of cardiac eveNts in a populaTion of dIabetic patients without A history of Cardiac disease): A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1365–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.