Abstract

HIV infection results in a complex immunodeficiency due to loss of CD4+ T cells, impaired type I interferon (IFN) responses, and B cell dysfunctions causing susceptibility to opportunistic infections such as Pneumocystis murina pneumonia and unexplained comorbidities, including bone marrow dysfunctions. Type I IFNs and B cells critically contribute to immunity to Pneumocystis lung infection. We recently also identified B cells as supporters of on-demand hematopoiesis following Pneumocystis infection that would otherwise be hampered due to systemic immune effects initiated in the context of a defective type I IFN system. While studying the role of type I IFNs in immunity to Pneumocystis infection, we discovered that mice lacking both lymphocytes and type I IFN receptor (IFrag−/−) developed progressive bone marrow failure following infection, while lymphocyte-competent type I IFN receptor-deficient mice (IFNAR−/−) showed transient bone marrow depression and extramedullary hematopoiesis. Lymphocyte reconstitution of lymphocyte-deficient IFrag−/− mice pointed to B cells as a key player in bone marrow protection. Here we define how B cells protect on-demand hematopoiesis following Pneumocystis lung infection in our model. We demonstrate that adoptive transfer of B cells into IFrag−/− mice protects early hematopoietic progenitor activity during systemic responses to Pneumocystis infection, thus promoting replenishment of depleted bone marrow cells. This activity is independent of CD4+ T cell help and B cell receptor specificity and does not require B cell migration to bone marrow. Furthermore, we show that B cells protect on-demand hematopoiesis in part by induction of interleukin-10 (IL-10)- and IL-27-mediated mechanisms. Thus, our data demonstrate an important immune modulatory role of B cells during Pneumocystis lung infection that complement the modulatory role of type I IFNs to prevent systemic complications.

INTRODUCTION

Pneumocystis is a ubiquitous extracellular pulmonary fungal pathogen with strict species specificity. It is likely contracted via airborne transmission from often transiently infected individuals and commonly causes few or unspecific symptoms in otherwise healthy individuals leading to immunity (reviewed in references 1 and 2). However, Pneumocystis can cause severe and progressive interstitial pneumonia in patients with impaired acquired immunity with mortality rates up to 60% (3). While the total number of functional CD4+ T cells critically determines increased susceptibility to Pneumocystis lung infection, patients with B cell defects are also at risk. In this regard, Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) is an AIDS-defining condition during HIV disease progression and commonly occurs when CD4+ T cell counts drop below 200 cells/μl (4). Furthermore, immune suppressive and cell ablative therapy following solid-organ transplantation, autoimmunity, or cancer treatment reduce CD4+ T cell and/or B cell numbers and impair functions in non-HIV patients (reviewed in references 5 and 6). Drug regimens that predispose to severe Pneumocystis infections include high-dose glucocorticoid and B cell ablative treatments with rituximab (7–11). In addition, low-grade Pneumocystis infection is found in patients with potentially subtle immune suppressions such as young infants, HIV-positive patients receiving HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy), or patients receiving low-dose and inhaled glucocorticoids (12–14). This can promote bronchial hyperreactivity, is associated with sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and exacerbation of chronic obstructive lung diseases (15–19).

Pneumocystis colonization also intensifies signs of systemic inflammation (20, 21). Thus, Pneumocystis may act as a profound comorbidity factor that may also enhance secondary systemic disease manifestations associated with chronic pulmonary diseases and HIV infection such as osteoporosis or bone marrow dysfunctions (22–28).

Immunity to Pneumocystis requires the presence of functional CD4+ T cells to stimulate antigen-specific immune globulin production by B cells and macrophage-mediated phagocytosis (4, 29–38). In addition, early innate type I interferon (IFN) production modulates this response and accelerates B cell differentiation into plasma cells and thus promotes Pneumocystis murina-specific antibody production (39). However, B cells also provide important T cell- and type I IFN-independent functions critical for the induction of immunity to Pneumocystis. One of these functions is the production of naturally occurring IgM antibodies against common fungal antigens that aid in Pneumocystis clearance (40). In addition, B cell-derived tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) production has been identified as a critical innate and antibody-independent mechanism to facilitate proper CD4+ T cell priming during responses to Pneumocystis lung infection (41, 42). While these B cell-mediated functions pertain to localized pulmonary responses and induction of pathogen clearance, we found that B cells also have important immune modulatory functions relevant to maintaining tissue homeostasis at distant organ sites to prevent immunity-driven tissue damage following systemic responses to Pneumocystis lung infection.

Both lymphocyte functions and type I IFN responses can be impaired as the result of HIV infection and immune suppressive treatment with, e.g., glucocorticoids (43–49). While studying the independent roles of both type I IFNs and lymphocytes in generating immunity to Pneumocystis lung infection, we recently discovered by serendipity that both type I IFN signaling and B cells are critical in regulating not only local but also systemic immune responses to Pneumocystis lung infection, and in this way, they protect on-demand hematopoiesis following the systemic inflammatory stress responses. We found that mice lacking both lymphocytes and type I IFN receptor (IFrag−/−) developed rapidly progressive bone marrow failure following pulmonary infection with Pneumocystis within 16 days, while lymphocyte-competent but type I IFN receptor-deficient mice (IFNAR−/−) show a transient bone marrow crisis with bone marrow depression and extramedullary hematopoiesis. These systemic symptoms occur without evidence for systemic dissemination of the pathogen and at a time when the pathogen lung burden is still low (50, 51). Immune reconstitution studies transferring splenocytes from either wild-type, IFNAR−/−, or B cell-deficient μMT mice into lymphocyte-deficient IFrag−/− mice pointed to B cells as the key player in bone marrow protection (50).

Bone marrow dysfunctions in both lymphocyte-competent and lymphocyte-deficient type I IFN-deficient mice are associated with exuberant inflammasome-mediated immune activation with increased release of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 followed by excessive induction of downstream mediators such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and augmentation of TNF-α responses (51, 52). However, the mechanisms by which B cells modulate these effects and thus protect from bone marrow failure are still unclear.

Here we demonstrate that adoptive transfer of purified B cells into IFrag−/− mice prior to infection protects early hematopoietic progenitor activity during systemic responses to Pneumocystis lung infection, thus promoting replenishment of depleted bone marrow cells. This activity does not require CD4+ T cell help, does not involve Pneumocystis clearance, and is mediated by innate, antigen-independent B cell functions. Transferred B cells predominantly migrate back to the spleen and lung, but not to bone marrow, suggesting a role of soluble factors in the role of B cell-mediated, systemic protection. Furthermore, we show that B cells complement the bone marrow protective activity of type I IFNs at least in part by induction of IL-10- and IL-27-mediated mechanisms possibly via interaction with and stimulation of macrophage/dendritic cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

All mice listed below were bred and maintained at Montana State University (MSU) Animal Resource Center. The mice were housed in ventilator cages and received sterile food and water. C.B17 SCID mice, as a source for Pneumocystis murina (PC) organism, and RAG1−/− mice (C57BL/6 background) were initially purchased from Jackson Laboratory (catalog no. 001803 and 002096, respectively). IFrag−/− mice were generated by crossing IFNARnull/null mice (C57BL/6 background) (kindly provided by E. Schmidt, MSU) with RAG1−/− mice (C57BL/6 background) as previously described (50). Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (catalog no. 027), and IL-10−/− mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (strain B6.129-IL-10Tm/cgn/J). B cell-deficient B6.129P2-Igh-Jtm1Cgn/J mice (μMT mice) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (catalog no. 002438), and mice carrying B cells capable of expressing only a human transgenic B cell receptor specific to hen egg lysozyme (HEL) [C57BL/6-Tg(IghelMD4)4Ccg/J] were crossed with B cell-deficient B6.129P2-Igh-Jtm1Cgn/J mice to generate mice capable of producing only B cells with a B cell receptor (BCR) specific to HEL and kindly provided by F. Lund (53).

Pneumocystis lung infections.

Experimental animals were intratracheally infected with 1 × 107 Pneumocystis murina nuclei (herein referred to as Pneumocystis) in 100 μl of lung homogenate from infected source mice diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer. Pneumocystis lung burden was assessed microscopically by enumeration of trophozoid and cyst nuclei in lung homogenates in 10 to 50 oil immersion fields as previously described (54). The limit of detection for this technique is log10 4.43.

Adoptive cell transfer and other treatments.

Immune reconstitution studies of IFrag−/− mice were performed using either total splenocytes derived from either wild-type C57BL/6 mice, B cell-deficient μMT mice, or B cell transgenic mice expressing a B cell receptor specific to hen egg lysozyme (HELμMT mice). Donor animals were euthanized via CO2 narcosis, and their spleens were removed sterilely. A single-cell suspension of spleen cells was prepared by homogenizing the spleens by forcing them through a mesh screen. The cell suspension was repeatedly filtered through 100-μm Nitex gauze to ensure that there were no clumps of cells. Animals were injected with 2 × 107 to 3 × 107 total cells in 200-μl volume of Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) solution via the tail vein 5 to 7 days prior to infection with Pneumocystis pathogen (50). For B cell transfer experiments, total spleen cells were isolated from wild-type C57BL/6 or IL-10−/− mice. For these experiments, the spleens were sterilely removed from donor mice and minced, and the cells were strained through a 100-μm mesh to make single-cell suspensions. Red blood cells were lysed using ACK lysis buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 10.0 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA [pH 7.2]). Total cell numbers were determined by using a hemocytometer, and B cell isolation was performed via negative selection using a magnetically activated cell sorting (MACS) B-cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) following the manufacturer's protocol. The purity of isolated B cells was consistently >95%. The final cell concentrations were adjusted to 5 × 107 B cells/ml in sterile PBS to be transferred into mice, and the mice received a total of 1 × 107 B cells in 200 μl via tail vein injection.

For in vivo tracking, B cells isolated as described above were labeled with Vybrant CDFA/SE cell tracer following the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes). Following the labeling procedure, 1 × 107 wild-type B cells were injected into IFrag−/− mice, and their spleens, lungs, and bone marrow were assessed for accumulation of transferred cells on days 1, 3, 5, and 7 postinfection. Cells could confidently be monitored to day 5 postinfection by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using an LSR cell analyzer (Becton Dickinson [BD]). In a separate confirmation experiment, B cell migration patterns over the course of infection were monitored in spleen, lung, mediastinal lymph nodes, and bone marrow by detecting the cells using a mouse B cell-specific antibody stained with a marker cocktail as described below.

Some groups of IFrag−/− mice received human recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist (Kineret; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum) at a concentration of 25 mg/kg of body weight/day (55) over the course of infection, while other groups were subcutaneously treated with 0.25 μg of recombinant, carrier-free IL-27 (Biolegend) every other day (56) or 0.4 μg of carrier-free IL-10 (57) over the course of Pneumocystis lung infection.

Collection and differentiation of bone marrow (BM) and lung cells.

BM cells from femurs and tibia were collected as previously described by flushing 2 ml of PBS through the BM canal using a 26.5-gauge needle and preparing a single-cell suspension (58).

BM cells were diluted 1:10 in PBS. The numbers of cells were determined, and the cells were spun onto glass slides and stained with Diff-Quik solution (Siemens). Cell differentiation was performed based on morphology and staining pattern to distinguish myeloid (including myeloblast-myelocyte and metamyelocyte stage), banded versus segmented neutrophils, eosinophils, and others (including erythroid, megakaryocytic, and lymphoid cells) (58).

FACS analysis was also applied to bone marrow cells as an additional unbiased measure of cell differentiation and for the detection and tracking of transferred B cells. Prior to FACS staining, red blood cell lysis of BM was performed using ACK lysis buffer. The cells were then suspended at 1 × 107/ml in FACS buffer (PBS containing 10% calf serum) containing Fc block (mouse clone 24G2; Pharmingen) at a 1:800 dilution. Sets of 5 × 105 cells were stained with specific antibodies particularly characterizing the myeloid lineage: major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) (peridinin chlorophyll protein [PerCP]–Cy5-5, clone M5/114.15.2, eBioscience), anti-CD11b (Alexa Fluor 700, clone M1/70, BioLegend), anti-Ly-6G/6C (allophycocyanin [APC]-Cy7, clone RB6-8C5, Pharmingen) as previously described (52). Samples were acquired using an LSR BD FACS machine and analyzed using FlowJo software.

FACS analysis was performed from lung, spleen, bone marrow, and mediastinal lymph nodes (MLNs) to track the migration of B cells transferred into IFrag−/− mice over the course of infection. For this analysis, the organs were removed from the mice, and single-cell suspensions were obtained as follows. The left lung lobes were removed, diced with scissors, and placed into 10 ml of PBS containing 1 mg/ml collagenase D (Roche) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The lungs were then placed into a 100-μm mesh filter screen and carefully pushed through into a clean tube. The spleens and MLNs were removed from the mice and homogenized by pushing them through a 100-μm filter screen. Red blood cell lysis was performed as described above using ACK lysis buffer. FACS staining was performed as described above using the following antibody mix: anti-CD19 (phycoerythrin [PE]-Cy7, clone eBio1D3 eBioscience), anti-B220 (PE, clone RA3-6B2, eBioscience), anti-IgM (APC, clone RMM-1, BioLegend), and anti-IgD (eFluor450, clone 11-26c, eBioscience).

Serum samples.

Serum samples were collected throughout the course of infection by harvesting whole-blood samples at each time point, which were spun and buffy coat was separated from the serum. Samples were frozen until further analysis.

Cytokine analysis.

Serum samples were assessed for levels of IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-18, IL-12p70, IL-10, and IL-27 using multiplex cytokine assay plates from either Multiplex or Bio-Rad Life Sciences and measured using a Bioplex (Bio-Rad) analysis system. In some experiments, IL-1β protein concentrations were separately measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reagents from R&D Systems (mouse IFN-γ DuoSet). In addition, IL-1 receptor antagonist concentrations were measured separately using ELISA reagents from R&D Systems (mouse DuoSet IL1ra/IL1F3).

Colony-forming cell assay for mouse bone marrow cells.

Hematopoietic precursor cell activity in BM from IFrag−/− and RAG−/− mice was assessed by hematopoietic colony-forming units (CFU) in methylcellulose medium as previously described (52). For this assay, 1 × 105 BM cells per animal and group at each time point were plated in MethoCult GF M3534 medium (StemCell Technologies) which has been formulated to support the optimal growth of granulocyte and macrophage precursor cells. Cells from each sample were plated in duplicate according to the manufacturer's protocol in 35-mm sterile culture dishes (StemCell Technologies), placed in 100-mm petri dishes in the presence of one 35-mm dish containing sterile water. The cultures were incubated for 7 days in a water-jacketed incubator maintained with 5% CO2. Colony recognition (granulocyte macrophage [GM]-, G-, M-forming colonies) and enumeration was performed according to StemCell Technologies guidelines.

Histology.

Livers and spleens of mice were fixed in a 10% formalin solution for 24 to 48 h and embedded in paraffin, and 5-μm-thick sections were cut on a Leica RM2255 microtome. Sections were hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained using reagents from Richard Allan Scientific.

Microscopy.

Microscopic evaluations of histology and cytospin slides were performed by using a Nikon Eclipse E200 microscope at magnifications of ×200 and ×1,000 and oil immersion. Bone marrow colony count analysis (CFU assays) was performed using a Zeiss Axiovert microscope and ×25 and ×50 magnifications.

Statistical analysis.

Data were plotted using Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.), and statistical analysis was performed using either a one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by a Tukey or Bonferroni posthoc test, respectively. For pairwise comparison, a Student's t test was performed.

RESULTS

B cells provide T cell- and antigen-independent mechanisms to maintain hematopoiesis during systemic responses to Pneumocystis lung infection in type I IFN receptor-deficient mice.

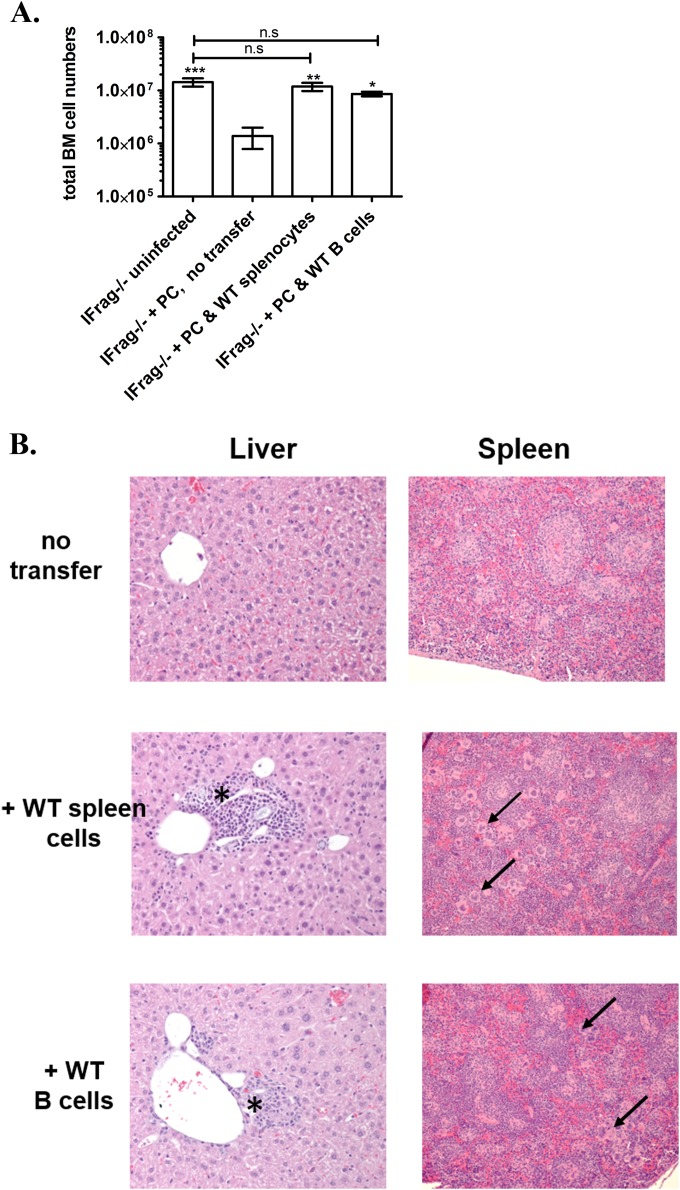

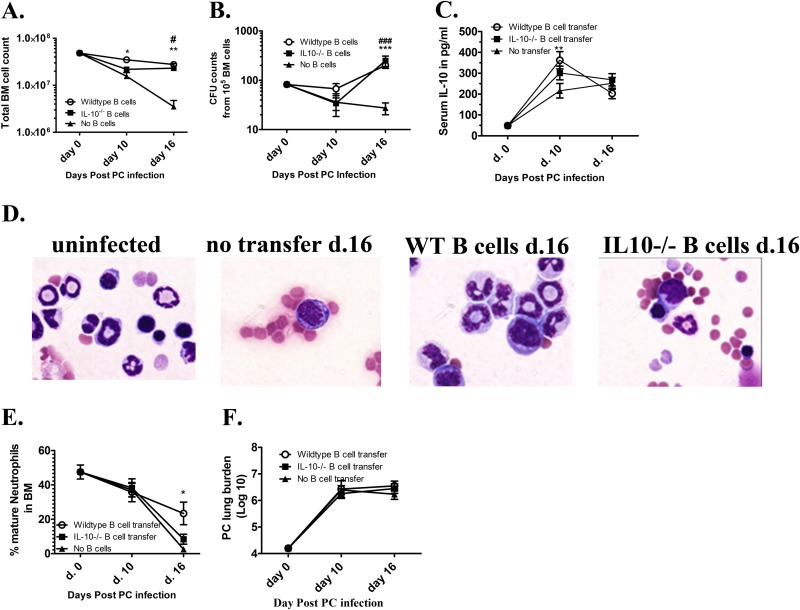

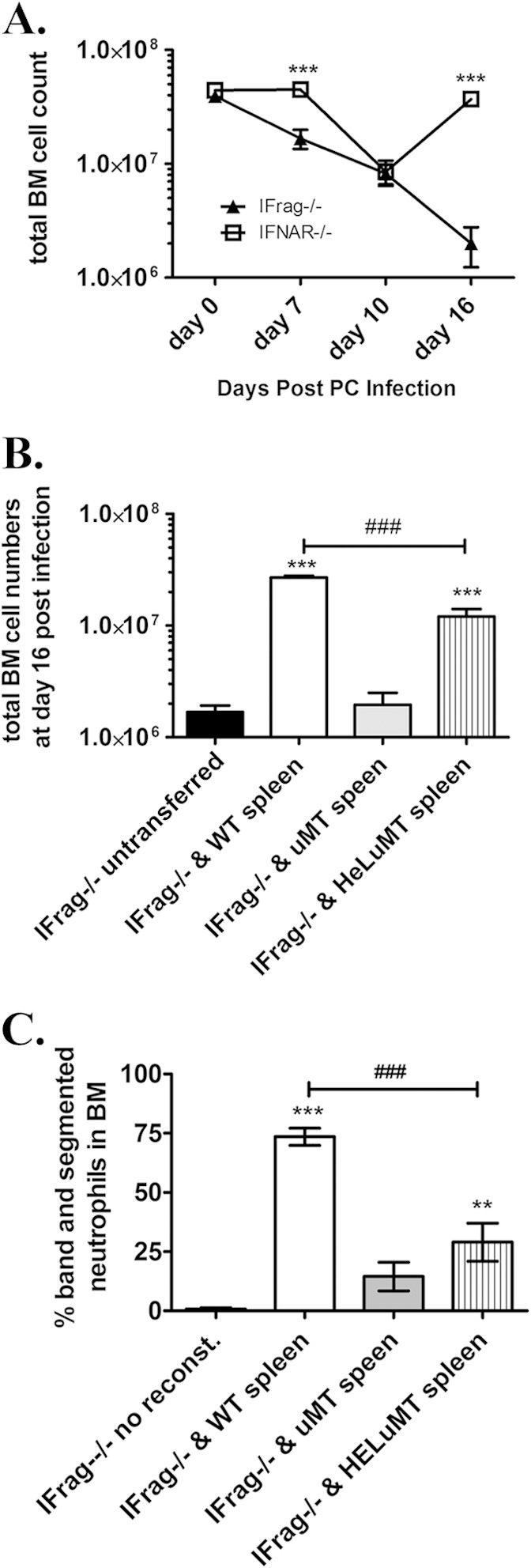

As previously reported and shown in Fig. 1A, Pneumocystis lung infection causes a transient bone marrow depression in lymphocyte-competent IFNAR−/− mice and complete bone marrow failure in lymphocyte-deficient IFrag−/− mice within 16 days postinfection. Splenocyte transfer experiments into IFrag−/− mice suggested a specific bone marrow protective role of B cells in our system (50).

FIG 1.

B cells protect hematopoiesis during responses to Pneumocystis lung infection by B cell receptor-independent mechanisms. (A) Total bone marrow (BM) cell counts obtained from lymphocyte-deficient IFrag−/− and lymphocyte-competent IFNAR−/− mice over a 16-day course of Pneumocystis murina (PC) lung infection. (B) Total bone marrow count from Pneumocystis-infected IFrag−/− mice at day 16 postinfection compared to those IFrag−/− mice in which either splenocytes derived from wild-type (WT) mice, B cell-deficient μMT mice, or splenocytes from mice exclusively expressing a B cell receptor from hen egg lysozyme were adoptively transferred. The results for IFrag−/− mice in which no cells were transferred (untranferred) are also shown. (C) Relative amount of neutrophils expressed as a percentage of total bone marrow cells analyzed by microscopy from the same groups (no reconst., immune system not reconstituted) displayed in panel B. For statistical analysis of the data in panel A, a two-way ANOVA was performed followed by a Bonferroni posthoc test. For statistical analysis of data in panels B and C, a one-way ANOVA was performed followed by a Tukey posthoc test. Values that are significantly different are indicated as follows: **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ###, P < 0.001 when comparing differences between IFrag−/− and WT spleen versus IFrag−/− and HELμMT spleen.

In these new studies, we set out to elucidate the mechanisms by which B cells act to protect from bone marrow failure following systemic immune responses to Pneumocystis lung infection in our model. To evaluate whether antigen-specific B cell receptor-mediated recognition of Pneumocystis is required for this bone marrow protective activity, IFrag−/− mice were immune reconstituted with total splenocytes isolated from either wild-type mice, B cell-deficient μMT mice, or HELμMT mice in which B cells are only capable to express a B cell receptor specific to hen egg lysozyme. The bone marrow responses of these mice were then determined at 16 days following Pneumocystis lung infection and compared to non-immune-reconstituted (unreconstituted) but infected IFrag−/− mice. As demonstrated in Fig. 1B, IFrag−/− mice that had received splenocytes containing B cells from either wild-type or HELμMT mice were protected from rapid bone marrow cell loss, while unreconstituted IFrag−/− mice as well as those receiving splenocytes deficient of B cells (μMT) were not protected. These data suggested that B cell-mediated activity relevant to protecting bone marrow functions are not antigen driven and may comprise as yet undefined innate B cell functions. However, IFrag−/− mice that had received wild-type splenocytes had significantly higher total bone marrow cell counts compared to those mice that had received splenocytes containing B cells with B cell receptor specificity to an irrelevant antigen (HEL). This is also reflected in lower percentages of mature and maturing neutrophil counts in bone marrow of IFrag−/− mice with transferred splenocytes from HELμMT mice, compared to mice with transferred wild-type splenocytes (Fig. 1C). This suggested an advantage of wild-type cells expressing polyclonal B cell receptors.

To further confirm that B cell-specific mechanisms are responsible for the bone marrow protective activity in IFrag−/− and IFNAR−/− mice, we adoptively transferred purified wild-type B cells into groups of IFrag−/− mice and compared their bone marrow responses to animals in which total wild-type splenocytes were transferred or animals in which no cells were transferred (untransferred) over the course of Pneumocystis lung infection. As demonstrated in Fig. 2A, both total-splenocyte-transferred as well as purified-B cell-transferred IFrag−/− mice retained equally high bone marrow cell numbers, while untransferred IFrag−/− mice progressed to bone marrow failure 16 days after Pneumocystis lung infection. These experiments confirmed that B cells alone protect bone marrow functions during systemic responses to Pneumocystis lung infection, and this protective activity does not require cognate help from CD4+ T cells present in the spleen. However, as previously also observed in lymphocyte-competent IFNAR−/− mice, extramedullary hematopoiesis in both liver and spleen was evident histologically in both transferred groups as a reflection of a continued bone marrow stress response (Fig. 2B) which is not present in either lymphocyte-competent wild-type mice or lymphocyte-deficient RAG−/− mice with intact IFN-α/β (alpha/beta interferon) receptor (IFNAR) expression (50). Interestingly, compensatory extramedullary hematopoiesis could not be detected in untransferred but infected IFrag−/− mice that progressed to bone marrow failure. This either suggested a role of B cells in promoting a beneficial niche environment for hematopoietic cell progenitors/hematopoietic stem cells at extramedullary sites or a role of B cells in neutralizing mechanisms that would otherwise harm circulating hematopoietic stem cell/progenitor functions.

FIG 2.

B cells do not require T cell-mediated help to facilitate protection from bone marrow failure as a result of Pneumocystis lung infection, but they promote extramedullary hematopoiesis as evidence for a bone marrow stress response. (A) Total bone marrow cell numbers of uninfected IFrag−/− mice compared to those of IFrag−/− mice infected with Pneumocystis murina on day 16 postinfection that were either left unreconstituted or that had received either total wild-type splenocytes or purified wild-type B cells prior to infection. Five mice per group were assessed. (B) H&E-stained histological sections of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded livers and spleens of mice in the groups compared, demonstrating evidence of extramedullary hematopoiesis in the form of cell nests in the liver (marked by an asterisk) and accumulation of megakaryocytes in the spleen (marked by arrows). For statistical analysis of data, a one-way ANOVA was performed followed by a Tukey posthoc test. Values that are significantly different are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Values that are not significantly different (n.s) are also indicated.

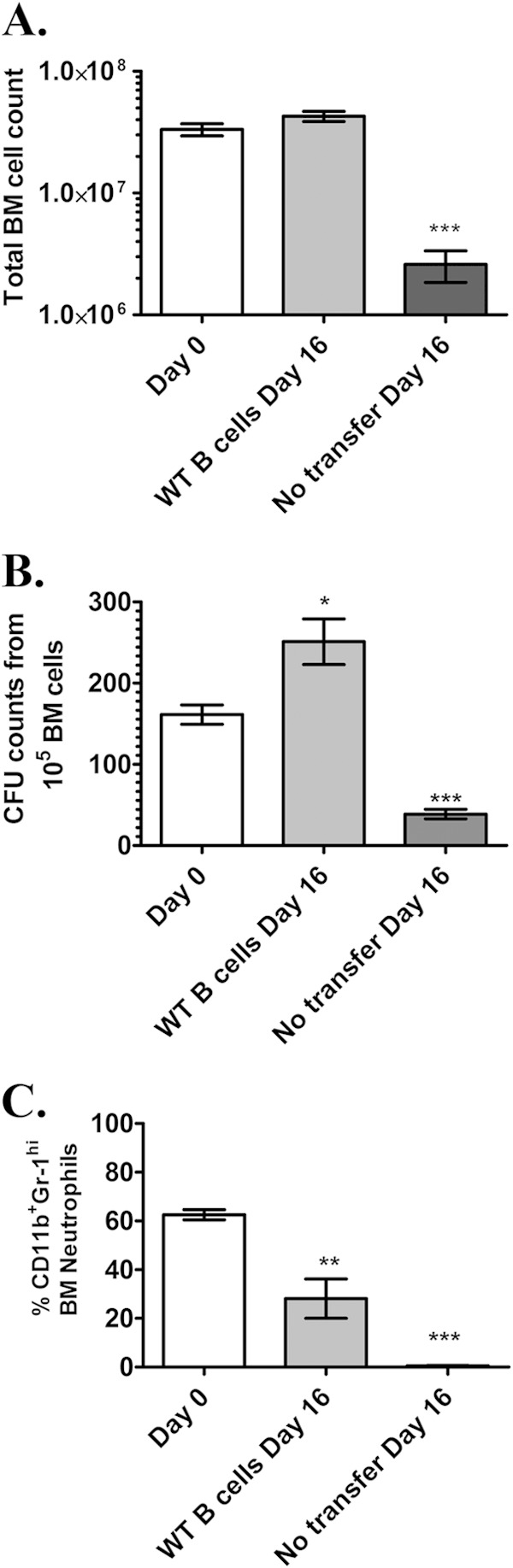

Given the evidence of continued hematopoietic stress, we evaluated whether B cell transfer into IFrag−/− mice was sufficient to maintain robust hematopoietic progenitor activity in bone marrow. Thus, 105 bone marrow cells isolated from either B cell-transferred or untransferred IFrag−/− mice at day 16 after Pneumocystis infection were plated in a hematopoietic colony-forming assay (CFU assay), and the colony-forming activity of granulocytic progenitor cells was compared to bone marrow cells isolated from uninfected IFrag−/− mice. As demonstrated in Fig. 3B, the bone marrow CFU activity remained robust and was commonly elevated than baseline activity in response to a decrease in CD11b+ Gr-1hi neutrophil numbers as a result of the infection (Fig. 3C). These data suggested that B cell transfer protected hematopoietic progenitor functions despite continued increased cellular turnover and accelerate neutrophil loss.

FIG 3.

Transfer of B cells into IFrag−/− mice promotes robust hematopoietic progenitor activity in bone marrow during responses to Pneumocystis lung infection. (A) Comparisons of total bone marrow cell numbers of uninfected IFrag−/− mice (day 0) to those of IFrag−/− mice in which B cells from wild-type mice had been transferred and mice in which no B cells were transferred on day 16 after Pneumocystis lung infection. Five mice per group were assessed. (B) Comparative analysis of hematopoietic progenitor activity for the granulocytic/monocytic lineage were performed by plating 1 × 105 total bone marrow cells per mouse in hematopoietic colony-forming assays (CFU assays) using reagents from StemCell Technologies. All samples were plated in duplicate. (C) Bone marrow cell differentiations were performed microscopically and by FACS analysis. The relative amount (percentage) of CD11b+ Gr-1hi-expressing neutrophils in the bone marrow of the comparison groups is shown. For statistical analysis of data, a one-way ANOVA was performed followed by a Tukey posthoc test. Values that are significantly different are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

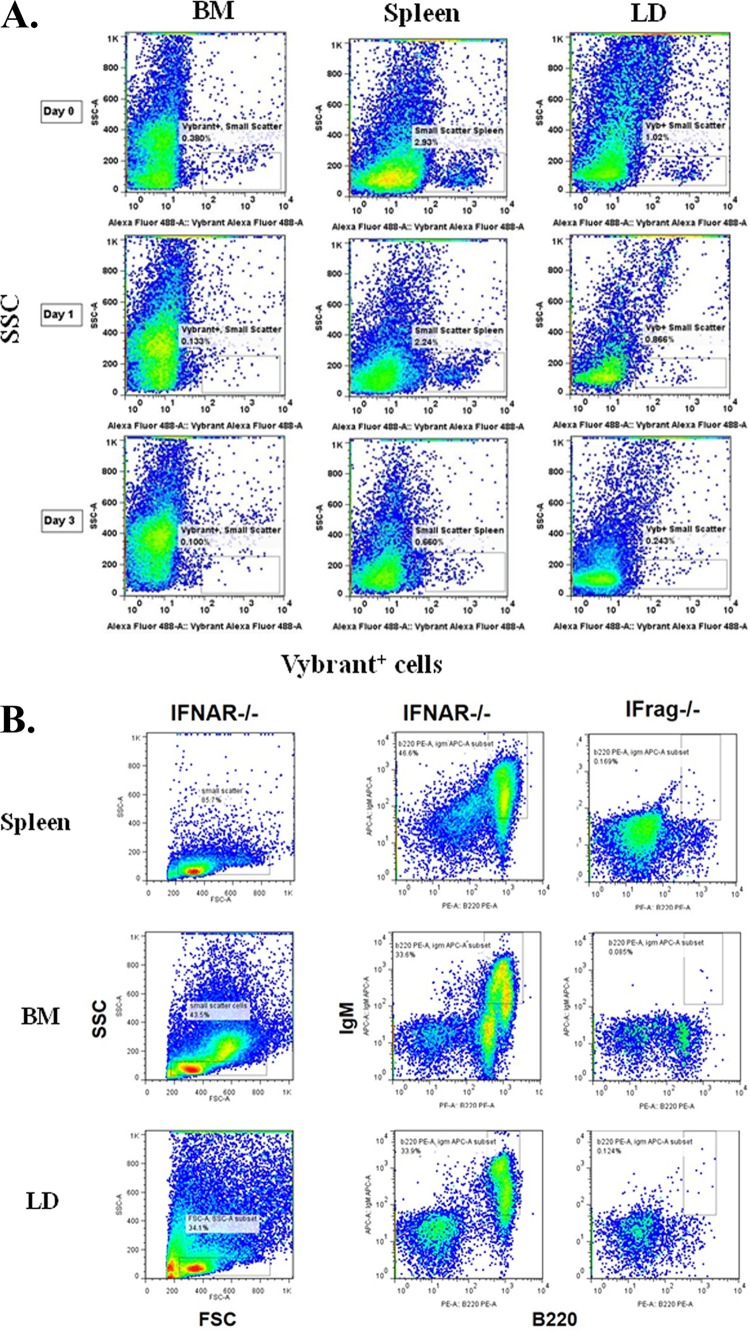

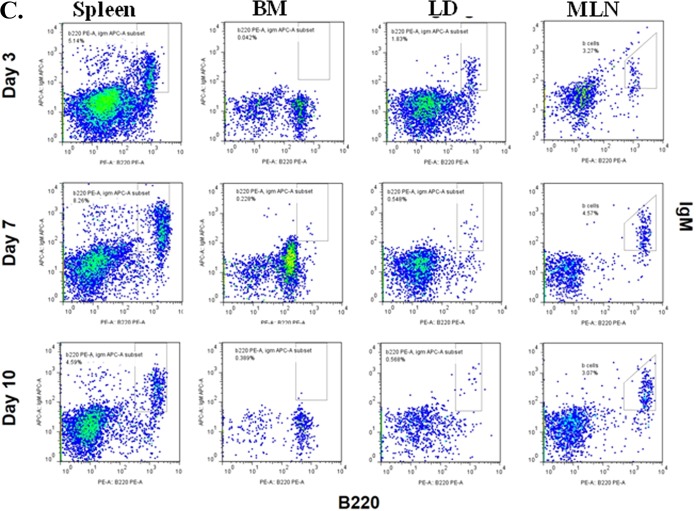

Adoptively transferred B cells protect hematopoiesis during the course of Pneumocystis lung infection without being retained in bone marrow.

To further gain insight into how B cells protect hematopoiesis during systemic responses to Pneumocystis lung infection, we monitored trafficking of transferred B cells in IFrag−/− mice over the course of infection. To do this, two different methodologies were used. We first transferred B cells labeled with a fluorescent membrane dye (Vybrant dye) at day −1 and examined spleen, bone marrow, and lung for accumulation of fluorescently labeled cells using FACS analysis on day 0 (day of infection) and days 1, 3 and 5 postinfection. As demonstrated in Fig. 4A, fluorescently labeled cells could be easily detected in the spleen and lung of B cell-transferred mice on day 0 and day 1, but were less apparent on day 3 postinfection and undetectable on day 5 (data not shown). In contrast, no cells could be convincingly detected in bone marrow past day 0 (day of infection). Using this approach, it was unclear whether cells were quickly undetectable due to a dilution effect of the membrane dye following cell proliferation or whether the cells had died. Thus, we tracked transferred B cells within IFrag−/− mice over the course of Pneumocystis lung infection in independent experiments using B cell-specific antibody staining (anti-B220 and anti-IgM) and detection by FACS analysis. Figure 4B shows the gating strategy based on forward/sideward scatter profile and double staining for IgM and B220 in lymphocyte-competent IFNAR−/− mice as a positive control and applied to lymphocyte-deficient IFrag−/− mice prior to transfer in which no IgM+ B220+ B cells were detected in any tissue tested. In contrast, IgM+ B220+ B cells could be detected in transferred IFrag−/− mice in spleen, lung, and MLNs on day 3, 7, and 10 postinfection but never convincingly in bone marrow, which was consistent with Vybrant dye tracking experiments.

FIG 4.

Transferred B cells predominantly accumulate in spleen, lung, and adjacent lymph nodes but not in bone marrow over the course of Pneumocystis lung infection. (A) Vybrant-dye labeled (Vybrant+) wild-type B cells were transferred into IFrag−/− mice 1 day prior to Pneumocystis lung infection (day −1), and their accumulation in spleen, lung, mediastinal lymph nodes, and bone marrow was tracked using FACS analysis on day 0 (prior to infection) and on day 1 and day 3 postinfection. FACS plots are shown as sideward scatter (SSC) (y axis) versus Vybrant+ (x axis). A gate was placed on Vybrant+ cells with low sideward scatter and applied to all samples. (B) FACS analysis of spleen, bone marrow, and lung cells for the presence of mature B cells by assessing cells for the coexpression of the B cell-specific markers IgM and B220 (CD45R) in lymphocyte-competent IFNAR−/− and lymphocyte-deficient IFrag−/− mice. Tissue-specific gates were placed on IgM+ B220+ cell populations based on the marker expression levels present in lymphocyte-competent mice and applied to IFrag−/− mice. Set gates were then further applied for the analysis of tissue-specific B cell accumulation in B cell-transferred IFrag−/− mice over the course of Pneumocystis lung infection. (C) Accumulation of IgM+ B220+ B cells transferred into IFrag−/− mice into spleen, bone marrow, lung (LD), and mediastinal lymph nodes (MLN) over the course of Pneumocystis lung infection on day 3, 7, and 10 postinfection.

B cell-mediated protection from bone marrow failure is associated with induction of immune modulatory cytokines.

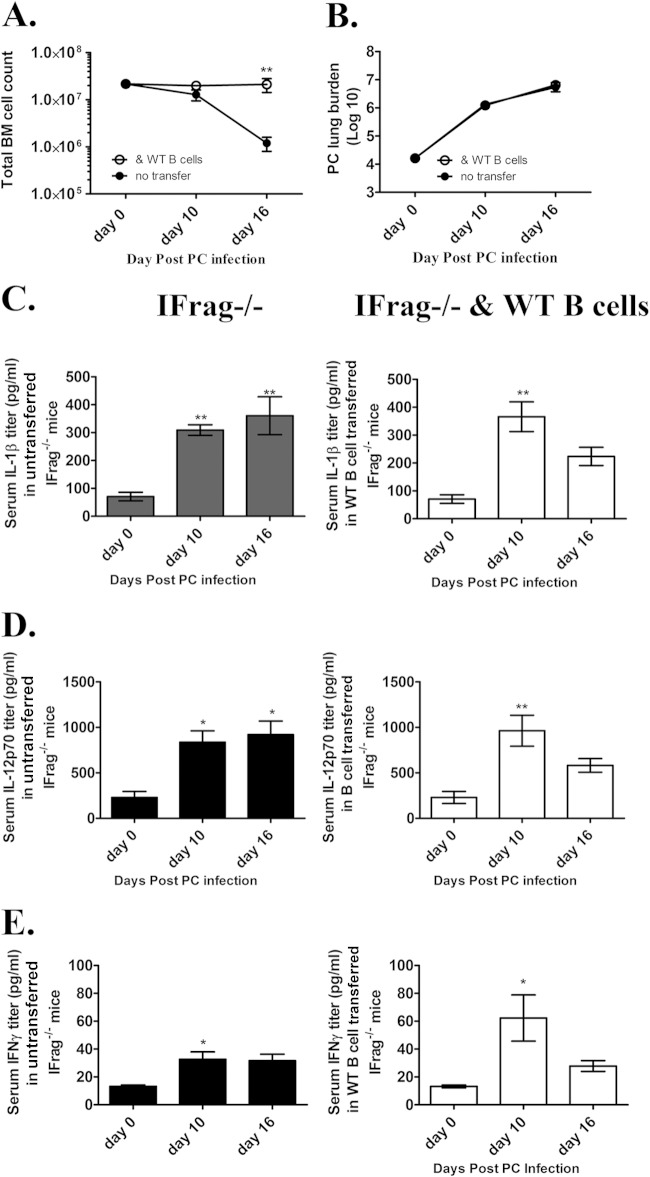

Bone marrow failure in IFrag−/− mice is associated with increased serum levels for the inflammasome-processed cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, but also for IL-12 and IFN-γ starting between day 7 and 10 postinfection. Importantly, this systemic effect is not observed in RAG−/− mice which lack bone marrow stress (51). To define whether the systemic inflammatory cytokine profile is directly modulated by the transfer of B cells into IFrag−/− mice, a comparative analysis of some signature serum cytokines was performed in Pneumocystis-infected untransferred and B cell-transferred IFrag−/− mice. As demonstrated in Fig. 5A to C in both untransferred and B cell-transferred mice with Pneumocystis lung infections, serum levels for IL-1β, IL-12, and IFN-γ were clearly elevated in both groups by day 10 postinfection. However, while cytokine levels continued to rise in untransferred IFrag−/− mice, inflammatory cytokine levels decreased in B cell-transferred mice by day 16 postinfection.

FIG 5.

B cell transfer into IFrag−/− mice does not significantly change the serum expression profile of proinflammatory mediators associated with induction of bone marrow dysfunctions following Pneumocystis lung infection. (A) Changes of total bone marrow cell numbers in IFrag−/− mice in which no cells were transferred (untransferred) and IFrag−/− mice in which B cells were transferred on days 0, 10 and 16 of Pneumocystis lung infection. (B) Comparisons of Pneumocystis lung burdens displayed as nucleus counts in log10 units between untransferred and B cell-transferred IFrag−/− mice over the 16-day course of infection. (C to E) Serum cytokine concentrations for IL-1β (C), IL-12p70 (D), and IFN-γ (E) found in transferred and B cell-transferred groups over the course of infection displayed in parallel. For statistical analysis of data between the two groups over time in panels A and B, a two-way ANOVA was performed followed by a Bonferroni posthoc test. For statistical analysis of data within one group over time in panels C to E, a one-way ANOVA was performed followed by a Tukey posthoc test. Values that are significantly different are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. For panels C to E, the values were compared to the value for day 0.

B cell-mediated induction of IL-10 and IL-27 contribute to protection of hematopoiesis when type I IFN signaling is absent.

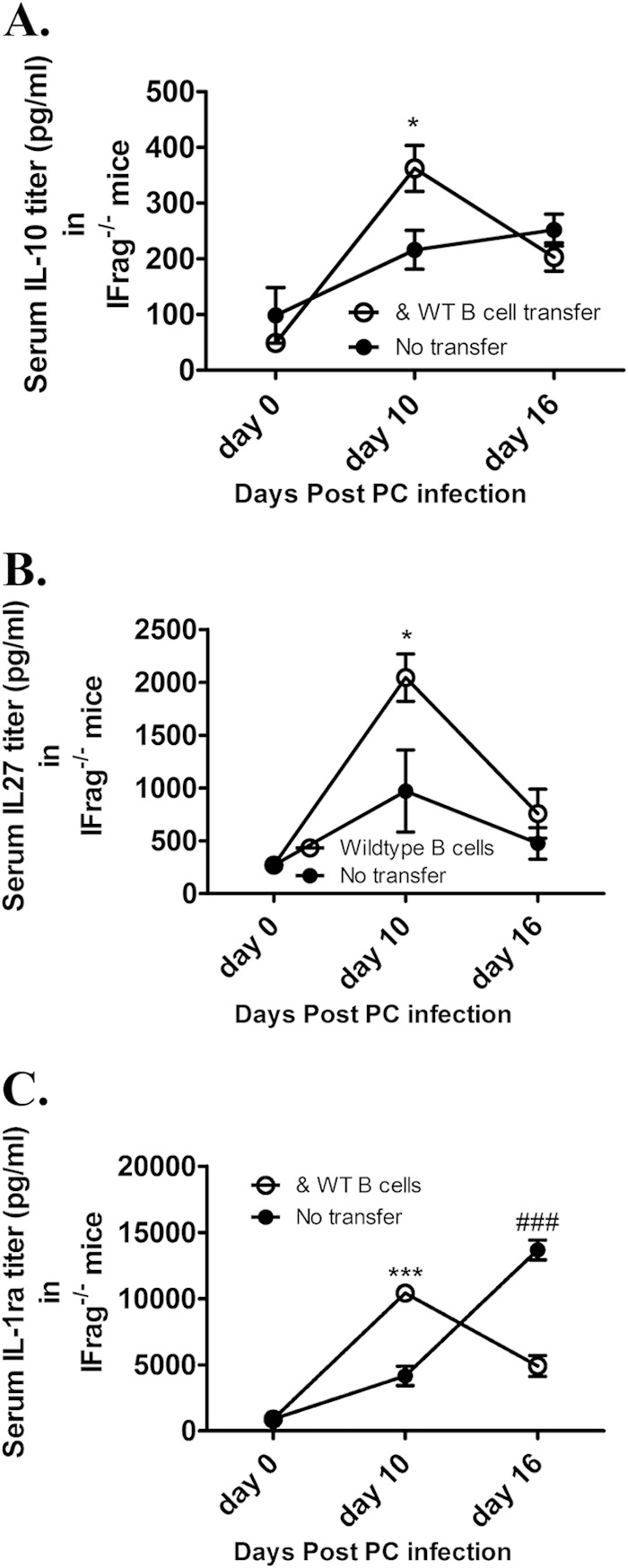

To determine whether B cells provide or induce a regulatory cytokine program in other cell types possibly capable of modulating inflammatory immune activation pathways following their induction, we compared serum levels of IL-10, IL-27 and interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL1Ra). As demonstrated in Fig. 6A to C, these cytokines, although also induced in untransferred mice, were significantly higher in B cell-transferred IFrag−/− mice on day 10 postinfection compared to untransferred IFrag−/− mice.

FIG 6.

B cell transfer into IFrag−/− mice is associated with increased serum levels for immune regulatory cytokines in response to Pneumocystis lung infection. (A to C) Comparative analysis of serum levels for interleukin-10 (A), interleukin-27 (B), and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (C) in untransferred versus B cell-transferred IFrag−/− mice on day 0, 10, and 16 after Pneumocystis lung infection. For statistical analysis of data between the two groups over time, a two-way ANOVA was performed followed by a Bonferroni posthoc test. Values that are significantly different are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ###, significantly higher in untransferred animals. For panels C to E, the values were compared to the value for day 0.

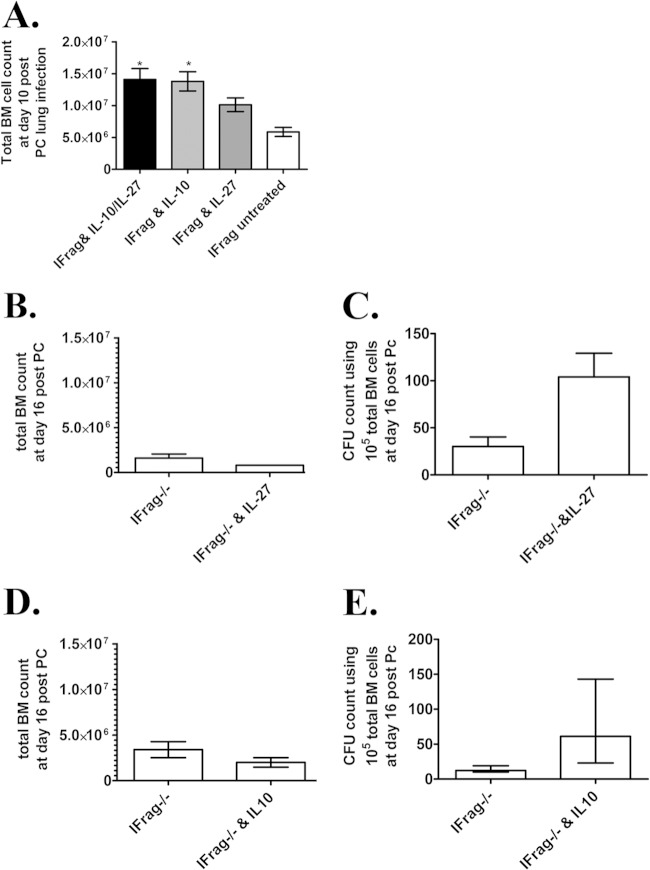

Thus, to investigate the functional contribution of these potentially regulatory cytokines to B cell-mediated protection of on-demand hematopoiesis, we first compared bone marrow responses of IFrag−/− mice in which B cells derived from either wild-type or IL-10−/− donor mice were transferred to those of untransferred mice following Pneumocystis lung infection. As demonstrated in Fig. 7, following an initial drop, total bone marrow count numbers as well as colony-forming activity remained robust in both B cell transfer groups, while these numbers continuously declined in untransferred animals within 16 days (Fig. 7A and B). While this first suggested a minor role of B cell-derived IL-10 to their bone marrow protective activity, we were surprised to find that serum IL-10 levels in both B cell transfer groups continued to be higher on day 10 after Pneumocystis lung infection compared to untransferred mice (Fig. 7C). While these levels were still higher in the mice in which wild-type B cells were transferred compared to those in which IL-10−/− B cells were transferred, it suggested a possible role of B cells in the induction of IL-10 production in other accessory cells during systemic responses to Pneumocystis lung infection. Furthermore, comparative morphological evaluation of bone marrow cells by microscopy revealed that mice that had received IL-10−/− B cells showed a decreased breadth of cellular differentiation stages particularly for neutrophil precursors compared to mice that had received wild-type B cells (Fig. 7D). This was also reflected in a significantly reduced percentage of mature neutrophil numbers compared to wild-type-B cell-transferred mice (Fig. 7E). Despite the differences in bone marrow responses, there were not differences in Pneumocystis lung burden in the groups compared (Fig. 7F). Thus, we concluded that IL-10 produced by B cells and induced in other accessory cells may modulate immunological mechanisms affecting the increased turnover of maturing neutrophils in bone marrow.

FIG 7.

B cell-derived IL-10 in conjunction with B cell-mediated induction of IL-10 in accessory cells protects on-demand hematopoiesis during responses to Pneumocystis lung infection. (A) Total bone marrow cell counts from IFrag−/− mice that were either left untransferred or that had received B cells isolated from wild-type or IL-10−/− donor mice on days 0, 10, and 16 after Pneumocystis lung infection. (B) Comparative analysis of hematopoietic progenitor activity for the granulocytic/monocytic lineage were performed by plating 1 × 105 total bone marrow cells per mouse of each comparison group in hematopoietic colony-forming assays (CFU assays) using reagents from StemCell Technologies. All samples were plated in duplicate. Total CFU numbers were plotted. (C) Serum IL-10 levels were measured in each group in the course of infection (from days 0 to 16 after infection) using ELISA reagents from R&D Systems. (D) Freshly flushed bone marrow cells were spun onto glass slides and evaluated morphologically by light microscopy following Diff-Quik staining. Bone marrow cells from uninfected and untransferred IFrag−/− mice are shown compared to IFrag−/− mice with Pneumocystis lung infections that had received B cells from either wild-type or IL-10−/− mice at 16 days (d.16) or were left untransferred. (E) Shown are the percentage of mature (band and segmented) neutrophils identified via morphological analysis and confirmed by FACS analysis in the comparison groups over the course of Pneumocystis lung infection. (F) Pneumocystis lung burden displayed as the number of nuclei in log10 units between the three groups over the 16-day course of infection. For statistical analysis of data between the two groups over time, a two-way ANOVA was performed followed by a Bonferroni posthoc test. Values that are significantly different are indicated as follows: * or #, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; *** or ###, P < 0.001. Each B cell-transferred group was compared separately to untransferred IFrag−/− group. Values compared to wild-type-B cell-transferred mice are shown as asterisks, and values compared to IL-10−/− B cell-transferred mice are shown as number or pound signs.

IL-27 is a pleiotropic cytokine which was also elevated in B cell-transferred IFrag−/− mice than in untransferred IFrag−/− mice and serves as an upstream regulator of IL-10 production (reviewed in references 56, 59, and 60). To further evaluate the combined and individual contributions of IL-10 and IL-27 to the B cell-mediated protection of on-demand hematopoiesis during systemic responses to Pneumocystis lung infection, we compared the bone marrow responses of infected IFrag−/− mice that had either received combined or individual treatment with IL-10 and IL-27 to those of untreated but infected IFrag−/− mice on day 10 postinfection. The early time point was initially chosen, as we expected only partial protection most likely evident early but not at later time points. Indeed, as demonstrated in Fig. 8A, total bone marrow cell counts of those mice that had received combined or individual treatments containing IL-10 had significantly higher total bone marrow cell counts than those mice that were left untreated as a result of greater numbers of mature and maturing neutrophils. Furthermore, although not always significant, those mice that had received IL-27 alone consistently demonstrated higher total cell numbers compared to untreated mice but lower total cell numbers than those that had received IL-10. To determine whether IL-10 and IL-27 may modulate separate aspects of the pathways responsible for the progression of bone marrow failure in our model, we then treated Pneumocystis-infected IFrag−/− mice with IL-10 or IL-27 separately and evaluated the effect on bone marrow failure progression compared to untreated mice at day 16 postinfection. While neither treatment could ultimately prevent the progressive loss of mature bone marrow cells in response to infection (Fig. 8B and D), only treatment with IL-27 was able to significantly improve hematopoietic progenitor activity for 16 days postinfection as reflected in increased colony-forming activity of bone marrow cells compared to untreated mice, while those mice that had received IL-10 consistently showed greater variability which did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 8C and E).

FIG 8.

Administration of recombinant IL-10 and IL-27 provide separate and partial protection from bone marrow failure in IFrag−/− mice. (A) Total bone marrow cell numbers of groups of IFrag−/− mice on day 10 postinfection that received combined treatment with recombinant IL-10 and IL-27 or received IL-10 or IL-27 alone or were left untreated. All cytokines were administered subcutaneously at a concentration of 400 ng/day for IL-10 and 250 ng/day for IL-27. (B to E) In two separate experiments, individual treatment with either IL-27 (B and C) and IL-10 (D and E) were continued throughout day 16 postinfection, and total bone marrow cell numbers were compared to untreated but infected mice (B and D) and hematopoietic progenitor activity was evaluated in colony assays (C and E). For statistical analysis, all comparisons were made to untreated mice and either a one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey posthoc test or a Student's t test for pairwise comparisons was performed. Values that are significantly different are indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

B cells are instrumental to the clearance of Pneumocystis lung infection (31, 32, 40, 41, 61). In addition, we were able to implicate B cells as supporters of on-demand hematopoiesis following Pneumocystis lung infection that would otherwise be hampered as the result of systemic immune deviations initiated in the context of a defective type I IFN system. These B cell-mediated mechanisms appeared independent of those required for Pneumocystis clearance (50, 51). This is of interest, as bone marrow dysfunctions resulting in pancytopenia-related comorbidities are common not only in patients with AIDS but also in patients treated for autoimmune diseases. Both patient groups have increased susceptibility to even low-grade Pneumocystis lung infection which might promote deviated systemic innate immune responses that may also hamper hematopoiesis (4, 62–65).

Although Pneumocystis is considered a strictly pulmonary fungal pathogen, rare cases of extrapulmonary manifestations have been reported in humans. This includes three independent cases reported by Rossi and colleagues that demonstrated disseminated Pneumocystosis with bone marrow involvement in patients with malignant lymphoma or HIV infection (66). However, although circulating fungal β-glucan levels can be detected at times early in the course of infection, we have yet been unable to prove dissemination of the pathogen itself to bone marrow of IFrag−/− mice. Therefore, on the basis of our current and previously published findings, it appears that bone marrow dysfunctions in our model are rather the result of deviated innate functions with profound systemic effects than due to pathogen propagation in bone marrow (50, 51).

Here we set out to define the mechanism by which B cells contribute to the protection of hematopoiesis following Pneumocystis lung infection in our model. We found that when B cells are transferred into IFrag−/− mice, they provide bone marrow protection by mechanisms that maintain hematopoietic progenitor activity which allows the replenishment of depleted cells. They do this independently of their antigen receptor specificity and in a T cell-independent manner. These data suggested that B cells convey their protective effect on bone marrow by mechanisms that require neither formation of an immunological synapsis between B and CD4+ T cells nor secretion of antigen-specific antibodies (67). Cell tracking studies of transferred B cells into IFrag−/− mice showed no indication of their accumulation in bone marrow but showed that they predominantly home to the spleen and to a lesser degree to the lung and adjacent lymph nodes. These data strongly suggested that B cells may influence the outcome of the systemic inflammatory effects of Pneumocystis lung infection by either directly modulating the innate immune pathways initiated in the lung or by providing regulatory functions that interfere downstream of specific inflammatory pathways. Although hematopoiesis is stimulated by inflammatory signals intended to promote cellular maturation and mobilize inflammatory cells to the site of infection (reviewed in references 68 and 69), exuberant inflammatory stimuli can be harmful to hematopoietic stem cell functions in part by the induction of functional senescence as a result of proliferative exhaustion (63, 70). However, the mechanisms that balance these effects on hematopoiesis are still poorly defined, and our model demonstrates a critical role of B cells in protecting hematopoiesis during early innate responses to Pneumocystis lung infection.

Consistent with this observation, B cells with regulatory, immune suppressive activity (Breg) have been defined within both follicular and marginal zone cell populations (reviewed in references 71 and 72). Breg of follicular origin are regulators of adaptive immunity and facilitate this activity in an antigen-specific and B cell receptor-dependent manner. In contrast, marginal zone B cells act as gatekeepers of innate immunity that modulate maturation and function of innate immune cells, including dendritic cells (DCs), resulting in profound immune suppression. Communication between these “innate-like” B cells and DCs is at least in part facilitated via secretion of IL-10 and CD40-CD40 ligand (CD40L) interaction (73, 74). Although both follicular and marginal zone B cells are capable of producing substantial amounts of IL-10, innate-like B cells are able to produce IL-10 independent of B-cell receptor-mediated stimulation but as the result of innate immune activation (75).

Similarly, type I IFNs can be immune regulatory and promote IL-10 and IL-27 production in innate immune cells such as dendritic cells and suppress inflammasome-mediated immune activation (56, 76–78). This is of interest, as previous work in our model of Pneumocystis lung infection-induced bone marrow dysfunctions found that these systemic effects may be due to exuberant Toll-like receptor (TLR) and especially inflammasome-mediated immune activation pathways likely due to the absence of type I IFN-induced immune regulation (51, 52). Surprisingly, we found that B cell transfer into IFrag−/− mice did not change the profile of the indicator serum cytokines IL-12, IL-1β, and IFN-γ following Pneumocystis lung infection compared to untransferred mice. However, serum IL-10 levels in conjunction with IL-27 and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL1Ra) were significantly higher in B cell-transferred IFrag−/− mice compared to untransferred mice. B cells can produce IL-10; however, IL-27 and IL1Ra are primarily monocytic/dendritic cell-derived mediators with immune modulatory activity. Specifically, IL-27 functions as an upstream regulator of IL-10 production in innate and adaptive immune cells, while IL1Ra is IL-10 induced and modulates IL-1-mediated activity (79–82). This suggested a modulatory role of B cells on DC/macrophage responses in our system.

Work by other investigators had already demonstrated an immune modulatory role of IL-10 on pulmonary response to Pneumocystis infection. Qureshi et al. have shown that IL-10−/− mice demonstrate enhanced clearance kinetics in CD4+ T cell-competent mice but increased lung damage in CD4+ T cell-depleted models (83). Furthermore, Ruan et al. have demonstrated that local delivery of viral IL-10 in a gene therapy-like approach in a mouse model is able to suppress the pulmonary damage caused by the hyperinflammatory response that commonly follows immune reconstitution as the result of low-grade Pneumocystis lung infection (84). Thus, we first evaluated to what extent B cell-derived IL-10 contributes to protection from bone marrow failure in our system by comparing the efficiency of B cells unable to produce IL-10 (IL-10−/− B cells) to those of wild-type B cells to protect from bone marrow failure when transferred into IFrag−/− mice. While we were surprised to see that B cells transferred from IL-10−/− mice were as capable of maintaining hematopoietic progenitor activity in bone marrow as wild-type B cells over the course of Pneumocystis lung infection, the number of mature neutrophils was clearly reduced compared to wild-type-B cell-transferred mice on day 16 postinfection. This suggested that IL-10 may be important in protection from mechanisms that accelerate increased cellular turnover of maturing bone marrow cells but that it is irrelevant for protection of progenitor functions. Although this observation is consistent with our impression of a two-pronged mechanism in the pathogenesis of bone marrow failure in our model (51), serum cytokine analysis revealed that IL-10 serum levels of IL-10−/− B cell-transferred mice were still above those of untransferred mice and nearly as high as those from mice in which wild-type B cells were transferred. Thus, transferred B cells may indeed modulate the functions of innate immune cells in lung and spleen to also promote regulatory dendritic cells or macrophages capable of producing IL-10 and other innate immune regulators (reviewed in references 85 and 86). This finding would be consistent with the concomitant upregulation of IL-10, IL-27, and also IL1Ra observed in B cell-transferred IFrag−/− mice (80, 87, 88). In support of this, we found in preliminary experiments that coculture of B cells with pulmonary CD11b+ MHC+ CD11c+ or CD11c− cells (macrophage/DCs) isolated from IFNAR-deficient mice on day 10 after Pneumocystis lung infection greatly enhanced secretion of the immune modulatory cytokine IL-27 following phorbol ester stimulation compared to cultures from pulmonary CD11b+ CD11c+ or CD11c− macrophage/DCs alone (data not shown).

Because IL-27 is both directly immune modulatory and is also an upstream regulator of IL-10 (56, 60, 89), we next treated IFrag−/− mice with IL-10 and IL-27 either alone or combined over the course of Pneumocystis lung infection to evaluate the outcome on bone marrow failure in our model. These experiments revealed that IL-10 and to a lesser degree IL-27 ameliorated the loss of mature bone marrow cells normally visible on day 10 postinfection, and IL-27 was particularly capable of improving progenitor activity for 16 days postinfection. While these treatments were not as effective as B cell transfer itself, it did support a role for both cytokines in the bone marrow protective ability of B cells. One aspect likely contributing to decreased efficiency of the cytokine treatments may be the inability to maintain continuous cytokine levels sufficient to convey optimal protection. Furthermore, additional factors not yet defined and/or tested may amplify the B cell-mediated effects. Given that we predict a significant role of exuberant inflammasome-mediated immune effects to be at least partially responsible for the observed systemic complications in our model, the increased serum levels of IL1Ra seen following B cell transfer may also play a significant role in the B cell-mediated protective effects. Preliminary experiments using daily administration of a lower dose of human recombinant IL1Ra (Kineret, 25 mg/kg/day) (55) have not resulted in satisfactory effects, and serum levels of the human recombinant protein were barely detectable. Therefore, we will continue to evaluate this pathway using increasing dosages and combined treatments with other immune modulators to clearly define the role of IL1Ra in modulating the extent of bone marrow dysfunctions following Pneumocystis lung infection in our model. An additional candidate highly produced by B cells and not yet pursued is the immune modulator osteoprotegrin. Osteoprotegrin acts as a decoy receptor for the proapoptotic factor TRAIL (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) as well as the osteoclast differentiation factor RANKL (receptor activator of NF-κB ligand) (90, 91). Both TRAIL and RANKL are uniquely upregulated in the bone marrow of both lymphocyte-competent and -deficient IFNAR-deficient mouse strains compared to IFNAR-intact mice and as the result of Pneumocystis lung infection. We know that an imbalance between these players does exist at least in IFrag−/− mice (92).

In conclusion, we were able to define a new and expanded role of B cells in modulating the outcome of innate immune responses to the strictly pulmonary pathogen Pneumocystis which can otherwise have profound systemic effects. Findings with our mouse model may reflect scenarios relevant to humans under conditions when the type I IFNs can be suppressed and therefore promote inflammasome-mediated immune activation (51). In addition to the loss of CD4+ T cells, impaired type I IFN and B cell functions exist in HIV-infected individuals, and the same functions can be impaired in patients treated with glucocorticoids (44–46, 48, 49, 93, 94). Specifically, although B cell hyperactivity is present during earlier stages of HIV infection, increased B cell turnover, functional exhaustion, and loss of memory function accompany HIV-related disease progression (95, 96). Furthermore, glucocorticoid treatment not only suppresses type I IFN responses, it also induces apoptosis in a variety of immune cells, including B cells (97). Type I IFN responses and B cell functions also decline during aging (98–101), resulting in a latent stage of immune suppression and susceptibility to even low-grade Pneumocystis infection (102). Under any of these conditions, systemic inflammation is common, and bone marrow dysfunctions are reported often without a clear pathogenic link (63, 64, 103–110).

While Pneumocystis lung infection is certainly not the main driver of all bone marrow dysfunctions, our model exemplifies the interconnectivity of organ systems during inflammation and the expanded role that Pneumocystis may play, not only as a pulmonary opportunistic pathogen but also as a trigger of significant systemic comorbidities. This work stresses the critical role that type I IFNs play in modulating local responses to this ubiquitous, often underappreciated, pathogen and the broader functions that B cells have in promoting successful immune responses during Pneumocystis infection. They do this by also regulating induction of early innate immune pathways independent from their role in pathogen clearance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the following funding sources: NIH RO1 HL90488 and COBRE 2P20RR020185.

We thank A. G. Harmsen for generously providing us with HELμMT mice that he had previously received from Francis Lund.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cushion MT, Stringer JR. 2010. Stealth and opportunism: alternative lifestyles of species in the fungal genus Pneumocystis. Annu Rev Microbiol 64:431–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas CF Jr, Limper AH. 2007. Current insights into the biology and pathogenesis of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Nat Rev Microbiol 5:298–308. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boonsarngsuk V, Sirilak S, Kiatboonsri S. 2009. Acute respiratory failure due to Pneumocystis pneumonia: outcome and prognostic factors. Int J Infect Dis 13:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sepkowitz KA. 2002. Opportunistic infections in patients with and patients without acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 34:1098–1107. doi: 10.1086/339548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gigliotti F, Wright TW. 2005. Immunopathogenesis of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Expert Rev Mol Med 7(26):1–16. doi: 10.1017/S1462399405010203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Avignon LC, Schofield CM, Hospenthal DR. 2008. Pneumocystis pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 29:132–140. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1063852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin-Garrido I, Carmona EM, Specks U, Limper AH. 2013. Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients treated with rituximab. Chest 144:258–265. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tasaka S, Tokuda H. 2012. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in non-HIV-infected patients in the era of novel immunosuppressive therapies. J Infect Chemother 18:793–806. doi: 10.1007/s10156-012-0453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonilla-Abadia F, Betancurt JF, Pineda JC, Velez JD, Tobon GJ, Canas CA. 2014. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in two patients with systemic lupus erythematosus after rituximab therapy. Clin Rheumatol 33:415–418. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang H, Yeh HC, Su YC, Lee MH. 2008. Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma receiving chemotherapy containing rituximab. J Chin Med Assoc 71:579–582. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(08)70173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katsuyama T, Saito K, Kubo S, Nawata M, Tanaka Y. 2014. Prophylaxis for Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologics, based on risk factors found in a retrospective study. Arthritis Res Ther 16:R43. doi: 10.1186/ar4472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maskell NA, Waine DJ, Lindley A, Pepperell JC, Wakefield AE, Miller RF, Davies RJ. 2003. Asymptomatic carriage of Pneumocystis jiroveci in subjects undergoing bronchoscopy: a prospective study. Thorax 58:594–597. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.7.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris A, Norris KA. 2012. Colonization by Pneumocystis jirovecii and its role in disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 25:297–317. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00013-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vargas SL, Hughes WT, Santolaya ME, Ulloa AV, Ponce CA, Cabrera CE, Cumsille F, Gigliotti F. 2001. Search for primary infection by Pneumocystis carinii in a cohort of normal, healthy infants. Clin Infect Dis 32:855–861. doi: 10.1086/319340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris A, Alexander T, Radhi S, Lucht L, Sciurba FC, Kolls JK, Srivastava R, Steele C, Norris KA. 2009. Airway obstruction is increased in pneumocystis-colonized human immunodeficiency virus-infected outpatients. J Clin Microbiol 47:3773–3776. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01712-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris A, Sciurba FC, Lebedeva IP, Githaiga A, Elliott WM, Hogg JC, Huang L, Norris KA. 2004. Association of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity and pneumocystis colonization. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 170:408–413. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200401-094OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vargas SL, Ponce CA, Hughes WT, Wakefield AE, Weitz JC, Donoso S, Ulloa AV, Madrid P, Gould S, Latorre JJ, Avila R, Benveniste S, Gallo M, Belletti J, Lopez R. 1999. Association of primary Pneumocystis carinii infection and sudden infant death syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 29:1489–1493. doi: 10.1086/313521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Contini C, Romani R, Cultrera R, Angelici E, Villa MP, Ronchetti R. 1997. Carriage of Pneumocystis carinii in children with chronic lung diseases. J Eukaryot Microbiol 44:15S. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1997.tb05743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Contini C, Villa MP, Romani R, Merolla R, Delia S, Ronchetti R. 1998. Detection of Pneumocystis carinii among children with chronic respiratory disorders in the absence of HIV infection and immunodeficiency. J Med Microbiol 47:329–333. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-4-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calderon EJ, Rivero L, Respaldiza N, Morilla R, Montes-Cano MA, Friaza V, Munoz-Lobato F, Varela JM, Medrano FJ, de la Horra C. 2007. Systemic inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who are colonized with Pneumocystis jiroveci. Clin Infect Dis 45:e17–e19. doi: 10.1086/518989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matos O, Costa MC, Correia I, Monteiro P, Vieira JR, Soares J, Bonnet M, Esteves F, Antunes F. 2006. Pneumocystis jiroveci infection in immunocompetent patients with pulmonary disorders, in Portugal. Acta Med Port 19:121–126. (In Portuguese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huertas A, Palange P. 2011. COPD: a multifactorial systemic disease. Ther Adv Respir Dis 5:217–224. doi: 10.1177/1753465811400490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huertas A, Testa U, Riccioni R, Petrucci E, Riti V, Savi D, Serra P, Bonsignore MR, Palange P. 2010. Bone marrow-derived progenitors are greatly reduced in patients with severe COPD and low-BMI. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 170:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caplan-Shaw CE, Arcasoy SM, Shane E, Lederer DJ, Wilt JS, O'Shea MK, Addesso V, Sonett JR, Kawut SM. 2006. Osteoporosis in diffuse parenchymal lung disease. Chest 129:140–146. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Womack JA, Goulet JL, Gibert C, Brandt C, Chang CC, Gulanski B, Fraenkel L, Mattocks K, Rimland D, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Tate J, Yin MT, Justice AC, Veterans Aging Cohort Study Project Team . 2011. Increased risk of fragility fractures among HIV infected compared to uninfected male veterans. PLoS One 6:e17217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown TT, Qaqish RB. 2006. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis: a meta-analytic review. AIDS 20:2165–2174. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801022eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isgro A, Leti W, De Santis W, Marziali M, Esposito A, Fimiani C, Luzi G, Pinti M, Cossarizza A, Aiuti F, Mezzaroma I. 2008. Altered clonogenic capability and stromal cell function characterize bone marrow of HIV-infected subjects with low CD4+ T cell counts despite viral suppression during HAART. Clin Infect Dis 46:1902–1910. doi: 10.1086/588480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sloand E. 2005. Hematologic complications of HIV infection. AIDS Rev 7:187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harmsen AG, Stankiewicz M. 1990. Requirement for CD4+ cells in resistance to Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in mice. J Exp Med 172:937–945. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shellito J, Suzara VV, Blumenfeld W, Beck JM, Steger HJ, Ermak TH. 1990. A new model of Pneumocystis carinii infection in mice selectively depleted of helper T lymphocytes. J Clin Invest 85:1686–1693. doi: 10.1172/JCI114621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garvy BA, Wiley JA, Gigliotti F, Harmsen AG. 1997. Protection against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia by antibodies generated from either T helper 1 or T helper 2 responses. Infect Immun 65:5052–5056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lund FE, Schuer K, Hollifield M, Randall TD, Garvy BA. 2003. Clearance of Pneumocystis carinii in mice is dependent on B cells but not on P. carinii-specific antibody. J Immunol 171:1423–1430. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson MP, Christmann BS, Dunaway CW, Morris A, Steele C. 2012. Experimental Pneumocystis lung infection promotes M2a alveolar macrophage-derived MMP12 production. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303:L469–L475. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00158.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson MP, Christmann BS, Werner JL, Metz AE, Trevor JL, Lowell CA, Steele C. 2011. IL-33 and M2a alveolar macrophages promote lung defense against the atypical fungal pathogen Pneumocystis murina. J Immunol 186:2372–2381. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steele C, Marrero L, Swain S, Harmsen AG, Zheng M, Brown GD, Gordon S, Shellito JE, Kolls JK. 2003. Alveolar macrophage-mediated killing of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. muris involves molecular recognition by the dectin-1 beta-glucan receptor. J Exp Med 198:1677–1688. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Limper AH, Hoyte JS, Standing JE. 1997. The role of alveolar macrophages in Pneumocystis carinii degradation and clearance from the lung. J Clin Invest 99:2110–2117. doi: 10.1172/JCI119384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gigliotti F, Haidaris CG, Wright TW, Harmsen AG. 2002. Passive intranasal monoclonal antibody prophylaxis against murine Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Infect Immun 70:1069–1074. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.3.1069-1074.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J, Gigliotti F, Bhagwat SP, George TC, Wright TW. 2010. Immune modulation with sulfasalazine attenuates immunopathogenesis but enhances macrophage-mediated fungal clearance during Pneumocystis pneumonia. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001058. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meissner NN, Swain S, Tighe M, Harmsen A. 2005. Role of type I IFNs in pulmonary complications of Pneumocystis murina infection. J Immunol 174:5462–5471. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rapaka RR, Ricks DM, Alcorn JF, Chen K, Khader SA, Zheng M, Plevy S, Bengten E, Kolls JK. 2010. Conserved natural IgM antibodies mediate innate and adaptive immunity against the opportunistic fungus Pneumocystis murina. J Exp Med 207:2907–2919. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lund FE, Hollifield M, Schuer K, Lines JL, Randall TD, Garvy BA. 2006. B cells are required for generation of protective effector and memory CD4 cells in response to Pneumocystis lung infection. J Immunol 176:6147–6154. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Opata MM, Ye Z, Hollifield M, Garvy BA. 2013. B cell production of tumor necrosis factor in response to Pneumocystis murina infection in mice. Infect Immun 81:4252–4260. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00744-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mogensen TH, Melchjorsen J, Larsen CS, Paludan SR. 2010. Innate immune recognition and activation during HIV infection. Retrovirology 7:54. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harman AN, Lai J, Turville S, Samarajiwa S, Gray L, Marsden V, Mercier SK, Jones K, Nasr N, Rustagi A, Cumming H, Donaghy H, Mak J, Gale M Jr, Churchill M, Hertzog P, Cunningham AL. 2011. HIV infection of dendritic cells subverts the IFN induction pathway via IRF-1 and inhibits type 1 IFN production. Blood 118:298–308. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-297721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamga I, Kahi S, Develioglu L, Lichtner M, Maranon C, Deveau C, Meyer L, Goujard C, Lebon P, Sinet M, Hosmalin A. 2005. Type I interferon production is profoundly and transiently impaired in primary HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis 192:303–310. doi: 10.1086/430931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soumelis V, Scott I, Gheyas F, Bouhour D, Cozon G, Cotte L, Huang L, Levy JA, Liu YJ. 2001. Depletion of circulating natural type 1 interferon-producing cells in HIV-infected AIDS patients. Blood 98:906–912. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.4.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chinenov Y, Gupte R, Dobrovolna J, Flammer JR, Liu B, Michelassi FE, Rogatsky I. 2012. Role of transcriptional coregulator GRIP1 in the anti-inflammatory actions of glucocorticoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:11776–11781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206059109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flammer JR, Dobrovolna J, Kennedy MA, Chinenov Y, Glass CK, Ivashkiv LB, Rogatsky I. 2010. The type I interferon signaling pathway is a target for glucocorticoid inhibition. Mol Cell Biol 30:4564–4574. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00146-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coutinho AE, Chapman KE. 2011. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights. Mol Cell Endocrinol 335:2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meissner N, Rutkowski M, Harmsen AL, Han S, Harmsen AG. 2007. Type I interferon signaling and B cells maintain hemopoiesis during Pneumocystis infection of the lung. J Immunol 178:6604–6615. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Searles S, Gauss K, Wilkison M, Hoyt TR, Dobrinen E, Meissner N. 2013. Modulation of inflammasome-mediated pulmonary immune activation by type I IFNs protects bone marrow homeostasis during systemic responses to Pneumocystis lung infection. J Immunol 191:3884–3895. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor D, Wilkison M, Voyich J, Meissner N. 2011. Prevention of bone marrow cell apoptosis and regulation of hematopoiesis by type I IFNs during systemic responses to pneumocystis lung infection. J Immunol 186:5956–5967. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris DP, Goodrich S, Mohrs K, Mohrs M, Lund FE. 2005. Cutting edge: the development of IL-4-producing B cells (B effector 2 cells) is controlled by IL-4, IL-4 receptor α, and Th2 cells. J Immunol 175:7103–7107. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swain SD, Lee SJ, Nussenzweig MC, Harmsen AG. 2003. Absence of the macrophage mannose receptor in mice does not increase susceptibility to Pneumocystis carinii infection in vivo. Infect Immun 71:6213–6221. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6213-6221.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petrasek J, Bala S, Csak T, Lippai D, Kodys K, Menashy V, Barrieau M, Min SY, Kurt-Jones EA, Szabo G. 2012. IL-1 receptor antagonist ameliorates inflammasome-dependent alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. J Clin Invest 122:3476–3489. doi: 10.1172/JCI60777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guo B, Chang EY, Cheng G. 2008. The type I IFN induction pathway constrains Th17-mediated autoimmune inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest 118:1680–1690. doi: 10.1172/JCI33342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Puliti M, Von Hunolstein C, Verwaerde C, Bistoni F, Orefici G, Tissi L. 2002. Regulatory role of interleukin-10 in experimental group B streptococcal arthritis. Infect Immun 70:2862–2868. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.2862-2868.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bolliger AP. 2004. Cytologic evaluation of bone marrow in rats: indications, methods, and normal morphology. Vet Clin Pathol 33:58–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-165X.2004.tb00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bosmann M, Ward PA. 2013. Modulation of inflammation by interleukin-27. J Leukoc Biol 94:1159–1165. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0213107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iyer SS, Ghaffari AA, Cheng G. 2010. Lipopolysaccharide-mediated IL-10 transcriptional regulation requires sequential induction of type I IFNs and IL-27 in macrophages. J Immunol 185:6599–6607. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Theus SA, Smulian AG, Steele P, Linke MJ, Walzer PD. 1998. Immunization with the major surface glycoprotein of Pneumocystis carinii elicits a protective response. Vaccine 16:1149–1157. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(98)80113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paiardini M, Muller-Trutwin M. 2013. HIV-associated chronic immune activation. Immunol Rev 254:78–101. doi: 10.1111/imr.12079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen C, Liu Y, Liu Y, Zheng P. 2010. Mammalian target of rapamycin activation underlies HSC defects in autoimmune disease and inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest 120:4091–4101. doi: 10.1172/JCI43873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. 2004. Stem cell aging and autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Trends Mol Med 10:426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sowden E, Carmichael AJ. 2004. Autoimmune inflammatory disorders, systemic corticosteroids and pneumocystis pneumonia: a strategy for prevention. BMC Infect Dis 4:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-4-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rossi JF, Eledjam JJ, Delage A, Bengler C, Schved JF, Bonnafoux J. 1990. Pneumocystis carinii infection of bone marrow in patients with malignant lymphoma and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Original report of three cases. Arch Intern Med 150:450–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bromley SK, Burack WR, Johnson KG, Somersalo K, Sims TN, Sumen C, Davis MM, Shaw AS, Allen PM, Dustin ML. 2001. The immunological synapse. Annu Rev Immunol 19:375–396. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.King KY, Goodell MA. 2011. Inflammatory modulation of HSCs: viewing the HSC as a foundation for the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol 11:685–692. doi: 10.1038/nri3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Glatman Zaretsky A, Engiles JB, Hunter CA. 2014. Infection-induced changes in hematopoiesis. J Immunol 192:27–33. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rodriguez S, Chora A, Goumnerov B, Mumaw C, Goebel WS, Fernandez L, Baydoun H, HogenEsch H, Dombkowski DM, Karlewicz CA, Rice S, Rahme LG, Carlesso N. 2009. Dysfunctional expansion of hematopoietic stem cells and block of myeloid differentiation in lethal sepsis. Blood 114:4064–4076. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-214916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mauri C, Bosma A. 2012. Immune regulatory function of B cells. Annu Rev Immunol 30:221–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mauri C, Ehrenstein MR. 2008. The ‘short' history of regulatory B cells. Trends Immunol 29:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zouali M, Richard Y. 2011. Marginal zone B-cells, a gatekeeper of innate immunity. Front Immunol 2:63. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Morva A, Lemoine S, Achour A, Pers JO, Youinou P, Jamin C. 2012. Maturation and function of human dendritic cells are regulated by B lymphocytes. Blood 119:106–114. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-360768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang X. 2013. Regulatory functions of innate-like B cells. Cell Mol Immunol 10:113–121. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang L, Yuan S, Cheng G, Guo B. 2011. Type I IFN promotes IL-10 production from T cells to suppress Th17 cells and Th17-associated autoimmune inflammation. PLoS One 6:e28432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chang EY, Guo B, Doyle SE, Cheng G. 2007. Involvement of the type I IFN production and signaling pathway in lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-10 production. J Immunol 178:6705–6709. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Guarda G, Braun M, Staehli F, Tardivel A, Mattmann C, Forster I, Farlik M, Decker T, Du Pasquier RA, Romero P, Tschopp J. 2011. Type I interferon inhibits interleukin-1 production and inflammasome activation. Immunity 34:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Murugaiyan G, Mittal A, Lopez-Diego R, Maier LM, Anderson DE, Weiner HL. 2009. IL-27 is a key regulator of IL-10 and IL-17 production by human CD4+ T cells. J Immunol 183:2435–2443. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Murugaiyan G, Mittal A, Weiner HL. 2010. Identification of an IL-27/osteopontin axis in dendritic cells and its modulation by IFN-gamma limits IL-17-mediated autoimmune inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:11495–11500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002099107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dinarello CA. 2009. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol 27:519–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Garlanda C, Dinarello CA, Mantovani A. 2013. The interleukin-1 family: back to the future. Immunity 39:1003–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Qureshi MH, Harmsen AG, Garvy BA. 2003. IL-10 modulates host responses and lung damage induced by Pneumocystis carinii infection. J Immunol 170:1002–1009. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ruan S, Tate C, Lee JJ, Ritter T, Kolls JK, Shellito JE. 2002. Local delivery of the viral interleukin-10 gene suppresses tissue inflammation in murine Pneumocystis carinii infection. Infect Immun 70:6107–6113. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6107-6113.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gordon S, Martinez FO. 2010. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity 32:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schmidt SV, Nino-Castro AC, Schultze JL. 2012. Regulatory dendritic cells: there is more than just immune activation. Front Immunol 3:274. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lamacchia C, Palmer G, Bischoff L, Rodriguez E, Talabot-Ayer D, Gabay C. 2010. Distinct roles of hepatocyte- and myeloid cell-derived IL-1 receptor antagonist during endotoxemia and sterile inflammation in mice. J Immunol 185:2516–2524. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Carl VS, Gautam JK, Comeau LD, Smith MF Jr. 2004. Role of endogenous IL-10 in LPS-induced STAT3 activation and IL-1 receptor antagonist gene expression. J Leukoc Biol 76:735–742. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1003526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moon SJ, Park JS, Heo YJ, Kang CM, Kim EK, Lim MA, Ryu JG, Park SJ, Park KS, Sung YC, Park SH, Kim HY, Min JK, Cho ML. 2013. In vivo action of IL-27: reciprocal regulation of Th17 and Treg cells in collagen-induced arthritis. Exp Mol Med 45:e46. doi: 10.1038/emm.2013.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Kelley M, Chang MS, Luthy R, Nguyen HQ, Wooden S, Bennett L, Boone T, Shimamoto G, DeRose M, Elliott R, Colombero A, Tan HL, Trail G, Sullivan J, Davy E, Bucay N, Renshaw-Gegg L, Hughes TM, Hill D, Pattison W, Campbell P, Sander S, Van G, Tarpley J, Derby P, Lee R, Boyle WJ. 1997. Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell 89:309–319. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]