Abstract

Cerebral perfusion was evaluated in 87 subjects prospectively enrolled in three study groups—healthy controls (HC), patients with insulin resistance (IR) but not with diabetes, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Participants received a comprehensive 8-hour clinical evaluation and arterial spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In order of decreasing significance, an association was found between cerebral blood flow (CBF) and sex, waist circumference, diastolic blood pressure (BP), end tidal CO2, and verbal fluency score (R2=0.27, F=5.89, P<0.001). Mean gray-matter CBF in IR was 4.4 mL/100 g per minute lower than in control subjects (P=0.005), with no hypoperfusion in T2DM (P=0.312). Subjects with IR also showed no CO2 relationship (slope=−0.012) in the normocapnic range, in contrast to a strong relationship in healthy brains (slope=0.800) and intermediate response (slope=0.445) in diabetic patients. Since the majority of T2DM but few IR subjects were aggressively treated with blood glucose, cholesterol, and BP lowering medications, our finding could be attributed to the beneficial effect of these drugs.

Keywords: cognitive impairment, diabetes, insulin resistance, obesity, perfusion

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity among American adults is at an astonishing 35.9%, with 15.5% of the population having a body mass index (BMI) of ⩾35 kg/m2.1 Obesity is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), heart disease, sleep apnea, joint damage, and many other negative effects. The prevalence of insulin resistance (IR) and metabolic syndrome also increases with obesity,2 exceeding 50% in those over 60 years of age.3

Cross-sectional and longitudinal epidemiologic studies show that T2DM is linked to an increased risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. Verbal memory and processing speed deficits are the most consistently observed cognitive deficits associated with T2DM.4 Interestingly, non-diabetic elderly with IR, already show similar reductions in cognitive impairment to those with T2DM.5 Even relatively short-term impairments in metabolism observed in adolescents with T2DM give rise to cognitive and structural brain abnormalities.6 Among adolescents with metabolic syndrome brain impairments are driven by the degree of IR, even after accounting for BMI.7

Surprisingly, the annual rate of cognitive decline in T2DM does not differ from age-matched controls,8 in contrast to accelerated decline in Alzheimer's disease (AD).9 Thus, if the key physiologic changes that spur the brain disturbance could be identified, then successful therapeutic reversal of diabetes-related cognitive dysfunction is more likely.

Patients with T2DM show structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) changes (such as brain atrophy10 and white-matter (WM) lesions11) that are correlated with cognitive scores.12 The MRI studies also report specific association between the hippocampal volume and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), a marker of long-term glucose control, and suggest that IR may be responsible for neuronal loss. Even among individuals without diabetes, IR has been associated with reductions in hippocampal volumes.13

We have proposed a model linking IR/T2DM to impairment of brain integrity through endothelial dysfunction.14 The model suggests alterations in cerebral blood flow (CBF) and its regulation. By examining the literature on several markers of microcirculation, Muris et al15 proposed that microvascular impairment is part of the etiology of T2DM. However, there are no CBF studies of individuals with IR but with no diabetes and few publications in diabetic patients. The reports to date are contradictory. In one of the earliest studies, Dandona et al16 measured global CBF by the 133-Xe inhalation method in 59 individuals with diabetes and 28 controls encompassing a wide range of ages. They reported age-related perfusion decline in both groups, with somewhat larger (but not statistically significant) CBF in patients.

However, more recent investigations report cerebral hypoperfusion in patients with T2DM.17, 18, 19 These contradictory findings suggest methodological difficulties in assessment of CBF. As suggested by the large variability in resting global CBF in the control subjects (Table 1), the measurement of cerebral perfusion remains challenging, with current techniques showing poor precision.

Table 1. Large intersubject variability of measured CBF: indication of poor precision.

| Reference | Technique | Age | Brain tissue |

CBF (mL/100 g per minute) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. | s.d. | ||||

| 20Asllani I, JCBF | ASL | 72±7 | GM | 62.4 | 13.0 |

| 21Shin W, MRM | DSC MRI | 48±14 | GM | 47.4 | 16.2 |

| 22Rostrup E, Neuroimage | PET O-15 | 23–29 | GM | 61.0 | 19.1 |

| 17Brundel M, J Diab Compl | PC MRI | 66±6 | WB | 53.3 | 11.3 |

ASL, arterial spin labeling; DSC, dynamic susceptibility contrast; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PC, phase contrast; GM, gray matter; WB, whole brain; Avg., average; s.d., standard deviation.

The purpose of this prospective study was to examine cortical perfusion in subjects with IR and T2DM. Specifically, we wanted to resolve the controversy regarding CBF changes in diabetic patients. A healthy control (HC) group was used as a reference. Since factors related to obesity underlie the pathophysiology of IR, we have designed the study to include a spectrum of obesity in each group. Each subject received an extensive medical and neuropsychological evaluation. Cerebral blood flow was measured with arterial spin labeling (ASL) MRI using cerebral WM as the flow reference region. Perfusion results were systematically compared with clinical metrics of diabetes and IR in addition to measures of cognitive performance, body mass, and blood pressure (BP).

Materials and methods

Ethical Guidelines

All examinations and procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the New York University Langone Medical Center Institutional Review Board under the requirements of the US Department of Health and Human Services regulations at 45 CFR part 46, as well as with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975/1983. Informed written consent was obtained from all volunteers and all components of this study were in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Anonymity of all volunteers was assured by removing the names, addresses, and other identifying information from data analyses.

Subjects

All subjects were recruited and prospectively enrolled in one of the three groups—HC, patients with IR but not diabetes, and patients with type 2 diabetes. Eighty-seven volunteers were included: 37 HC, 27 IR, and 23 T2DM. Within the HC group, the enrollment was driven by the need to recruit at least six obese and six overweight individuals: after recruiting a sufficient number of 'lean controls' (BMI<25 kg/m2), further enrollment was restricted to overweight (25⩽BMI<30) and obese (BMI>30) HC subjects.

Participants had a minimum of a high-school education. Excluded were individuals with significant coronary ischemic disease, Modified Hachinski Ischemia score>4, any focal neurologic signs, current diagnosis or history of stroke, significant head trauma, or evidence of tumor on the structural MR scan. Furthermore, subjects with evidence of significant cognitive impairment (mini-mental state examination score<27 or a Global Deterioration Scale23⩾3) or uncontrolled hypertension (BP>150/90 mm Hg) were also excluded.

Participants received medical, endocrine, psychiatric, neuropsychological, and brain MRI evaluations during a comprehensive 8-hour evaluation completed over two visits within 1 month. Individuals were assigned to one of the three groups as follows:

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Participants were classified in this group if (1) they had a prior diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, (2) they had an HbA1c value of >6.5%, or (c) their 2-hour oral (75 g) glucose tolerance test resulted in the glucose level of 200 mg/dL or higher. The prior diagnosis was confirmed by monitoring HbA1c and glucose tolerance tests in our laboratory. The majority (16 of 23) of diabetic patients took oral medications to lower blood glucose levels: 15 were taking metformin (trade name Glucophage) either alone (N=8) or in combination with other drugs, and one sitagliptin (Januvia). Three diabetic patients were on insulin treatment: two were taking detemir (Levemir) and one insulin aspart (NovoLog).

Insulin resistance

Individuals in the insulin-resistant group did not meet T2DM criteria as determined by HbA1c or glucose tolerance test, but had fasting hyperinsulinemia, leading to quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index (QUICKI)<0.35. The QUICKI incorporates fasting glucose and insulin levels and has been validated against the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic glucose clamp.24 None of IR subjects took glucose lowering medications.

Healthy control

Individuals in the control group had no evidence of T2DM or IR according to HbA1c, glucose tolerance test, and QUICKI. Generally, their fasting glucose levels were <90 mg/dL and fasting insulin levels <9 μU/mL.

The demographic data and participant characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Subjects with diabetes were on average 3 years older than subjects in the HC and IR groups. The groups were well matched on education and IQ. On average, participants in the IR and T2DM participant groups were heavier than those HC group. All participants successfully completed the ASL MR imaging exam.

Table 2. Key characteristics of study subjects.

| Characteristic |

HC |

IR |

T2DM |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N or avg. | % or s.d. | N or avg. | % or s.d. | N or avg. | % or s.d. | |

| N | 37 | 43% | 27 | 31% | 23 | 26% |

| Age (years) | 51.8 | 3.8 | 50.9 | 4.5 | 54.2 | 5.2 |

| Female | 22 | 59% | 14 | 52% | 14 | 61% |

| Education (years) | 15.6 | 2.5 | 15.5 | 2.2 | 15.7 | 2 |

| BMI | 25.2 | 5 | 33.9 | 7.3 | 33.1 | 4.9 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.5 | 0.3 | 5.3 | 1.1 | 7.9 | 1.8 |

| QUICKI | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.30a | 0.04 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 85.9 | 6.1 | 91.4 | 6.8 | 159.4 | 54.7 |

| Insulin (μU/mL) | 4.6 | 1.7 | 12.2 | 4.0 | 16.2 | 7.6 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 114.5 | 11.4 | 124.1 | 13.4 | 125.7 | 10.9 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 72.2 | 7.6 | 79.8 | 7.4 | 77.1 | 10.2 |

| IQ WASI | 111.7 | 11.3 | 109.9 | 10.7 | 110.1 | 10.2 |

BMI, body mass index in kg/m2; BP, blood pressure; IQ WASI, intelligence quotient from Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale test; IR, insulin resistance; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HC, healthy controls; T2DM, type 2 diabetes; QUICKI, quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index. Underlined values indicate significant difference across groups (one-way ANOVA).

β-Cell dysfunction, part of the pathophysiology of diabetes, renders QUICKI values difficult to interpret in subjects with T2DM.

Imaging Protocol

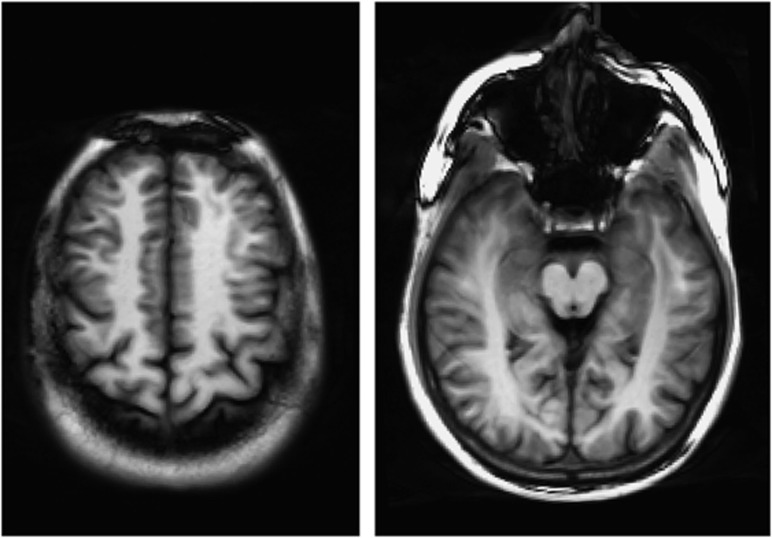

Imaging was performed at 3 T (Tim Trio, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using a 12-element head coil for signal reception and the integrated body coil for radiofrequency transmission. The subject's head was supported using foam pads to reduce motion. Perfusion data were acquired using an balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) ASL technique (described below) in two axial slices (Figure 1), one at the level of the cingulate gyrus and the second passing through the middle temporal gyrus. End-tidal CO2 was monitored and recorded continuously. This was important because arterial CO2 tension is known to be a potent modulator of CBF (increased CO2 causing vasodilation). CO2 monitoring was performed by fitting the subjects with a mouthpiece and sampling the expired air continuously with an infrared capnometer via a 3-m-long cannula attached to the mouthpiece. Heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood oxygen saturation were also monitored continuously during the ASL exam.

Figure 1.

The arterial spin labeling (ASL) signal was acquired at two 8-mm-thick axial locations. Left: upper slice at the level of the cingulate gyrus. Right: lower slice at the level of the middle temporal gyrus. bSSFP images show good gray-/white-matter tissue contrast that aids in segmentation. Note the availability of ample white matter to use as a reference region in the perfusion analysis.

Arterial Spin Labeling Technique

The ASL technique was based on the flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery (FAIR) method with a bSSFP readout.25 A 12-element head coil receiver and a body coil were used. Flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery is a type of pulsed ASL, in which two inversion recovery images are acquired, one with a slice-selective inversion pulse (to generate a ‘labeled image'), and one with a nonselective inversion pulse (to generate the ‘control image'). The slice-selective inversion pulse is applied in a thin slab encompassing the imaging slice, and the inversion time is chosen so that blood proximal to the inversion slab will have time to flow into the imaging slice and perfuse the tissue. When the control image is subtracted from the labeled image, signal from static spins in the tissue will cancel out, leaving only signal from water in the blood that has flowed into the imaging slice and perfused the tissue. The difference image can thus be used to generate a map of tissue perfusion. In our implementation, the spatially selective inversion slab was 2.5 times the thickness of the imaging slice, and the inversion time was 1.2 seconds.

The FAIR ASL method does not have the limitations of variable delay time between the tagged blood and the region of interest (ROI) that affect continuous ASL methods. However, the FAIR technique assumes that the global inversion pulse inverts water in static tissue to the same extent as the slice-selective inversion pulse, which may not be accurate due to imperfect slice profiles or to B0 field inhomogeneity.26 To compensate for this asymmetry, we used the signal in normally appearing WM as a reference in the perfusion analysis (described below).

A bSSFP readout was chosen instead of the more conventional echo planar readout to reduce susceptibility artifacts and allow for higher spatial resolution without image distortion. Data were acquired in a single shot after the inversion pulse, using parallel imaging with an acceleration factor of 2 to reduce the echo train duration. Other parameters included echo time=1.41 ms, flip angle=50°, receiver bandwidth=977 Hz/pixel, slice thickness=8 mm and in-plane spatial resolution=1.2 × 1.2 mm2, which was fine enough to resolve small blood vessels. To improve signal-to-noise ratio, 48 repetitions were performed, alternating between nonselective and slice-selective inversions. The repetition time between successive inversion pulses was 3 seconds. Since this was not long enough to ensure complete recovery of magnetization, the first four repetitions were excluded from the analysis to avoid transient effects. The entire ASL acquisition took 2 minutes 24 seconds per slice.

Image Analysis

A general kinetic model was used to calculate CBF in gray matter (GM) from the signal difference between label and control images. We compensated for imperfect slice profile and B0 field inhomegeneity by using the signal difference in normally appearing WM as a reference.27 This approach assumes that the CBF in normally appearing WM is low and constant, an assumption that is justified by extensive imaging data and by histopathologic evidence of ~2.5 lower microvascular density in cerebral WM compared with GM.28 We have showed that small deviations from this assumption introduce a relatively minor bias on flow measurements in cerebral GM.27 On the basis of prior studies, we used a nominal value of 25 mL/100 g per minute for WM perfusion29 and constrained the equations of our general kinetic model so that the average WM flow would equal this value. To exclude blood vessels, all voxels with CBF exceeding 150 mL/100 g per minute were segmented out from GM region (see below).

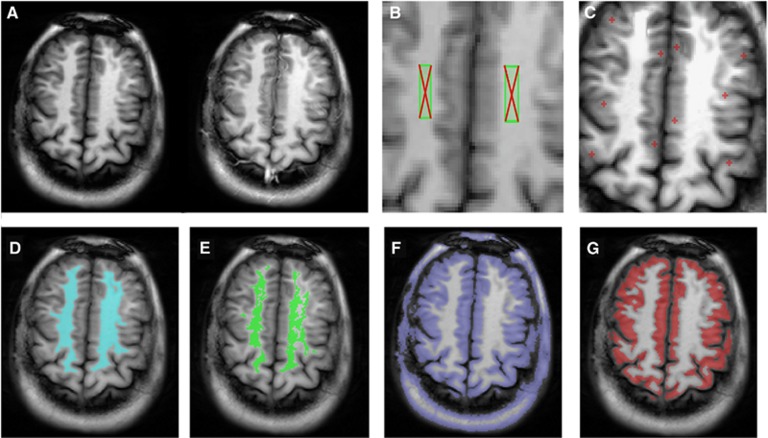

The key steps in the image processing pipeline are shown in Figure 2. The ASL images are loaded onto the workstation to generate ROIs for WM and GM. First, seeds are chosen in WM (Figure 2B) and GM (Figure 2C). An initial WM ROI is constructed from voxels whose signal is within 10% of the WM seed, and restricted to the largest connected components (Figure 2D). It is then refined by removal of outliers from the CBF histogram to eliminate voxels that are contaminated by lesions and partial volume of GM (Figure 2E). The GM ROI is obtained by intensity thresholding (Figure 2F) followed by automatic boundary erosion and removal of nonbrain tissue (Figure 2G). Postprocessing is performed blind to group membership and takes ~5 to 10 minutes per case. A batch process is then run to generate GM CBF.

Figure 2.

Steps to generate white-matter (WM) and gray-matter (GM) regions of interest (ROIs). (A) A control image (left) and labeled image (right) acquired using the flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery-based arterial spin labeling (ASL) sequence with bSSFP readout. (B) Two WM seeds placed by the user. (C) Ten small GM seeds are placed on the cortex. (D) The initial WM ROI in blue is constructed from voxels whose signal is within 10% of the seed, and restricted to the largest connected component. (E) The final WM ROI in green is obtained by removal of outliers from CBF histogram of the initial ROI. The aim is to eliminate voxels contaminated with WM lesions and partial volume of GM. (F) The initial GM ROI is obtained by selecting voxels whose signal is less than a threshold equal to the average of WM ROIs and GM seeds. (G) The final GM ROI in red is obtained by automatic boundary erosion to reduce partial volume effect followed by interactive removal of nonbrain areas (using an ‘electronic eraser'). Similar processing steps are applied to the temporal slice.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). A general linear model was used to identify factors correlated with GM CBF. The independent variables included in the model are listed in Table 3. The influence (i.e., interaction) between group membership (namely HC, IR, and T2DM) and significant continuous predictors of cortical CBF was analyzed using homogeneity of slopes design of general linear model.

Table 3. Measures and characteristics evaluated as predictors of CBF.

| Potential predictor | Abbreviation | R | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | SEX | 0.288 | 0.007 |

| Waist circumference | WAIST | 0.277 | 0.009 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | BP_DIAST | 0.273 | 0.011 |

| End tidal CO2 | CO2 | 0.258 | 0.016 |

| Verbal fluency score | COWAT | 0.222 | 0.039 |

| Body mass index | BMI | 0.207 | 0.050 |

| Insulin | INSULIN | 0.163 | NS |

| Education (years completed) | EDUC | 0.152 | NS |

| WIAT composite score | WIAT | 0.149 | NS |

| Quantitative insulin sensitivity | QUICKI | 0.148 | NS |

| Stroop interference score | STROOP | 0.087 | NS |

| Systolic blood pressure | BP_SYS | 0.085 | NS |

| Hispanic | HISP | 0.061 | NS |

| Homeostatic model assessment | HOMA | 0.055 | NS |

| African American | AA | 0.055 | NS |

| HbA1c | HbA1c | 0.042 | NS |

| Age | AGE | 0.038 | NS |

| Wechsler memory score | MEM | 0.022 | NS |

| Glucose | GLUCOSE | 0.020 | NS |

| WAIS IQ score | IQ | 0.011 | NS |

Results

Predictors of Gray-Matter Perfusion

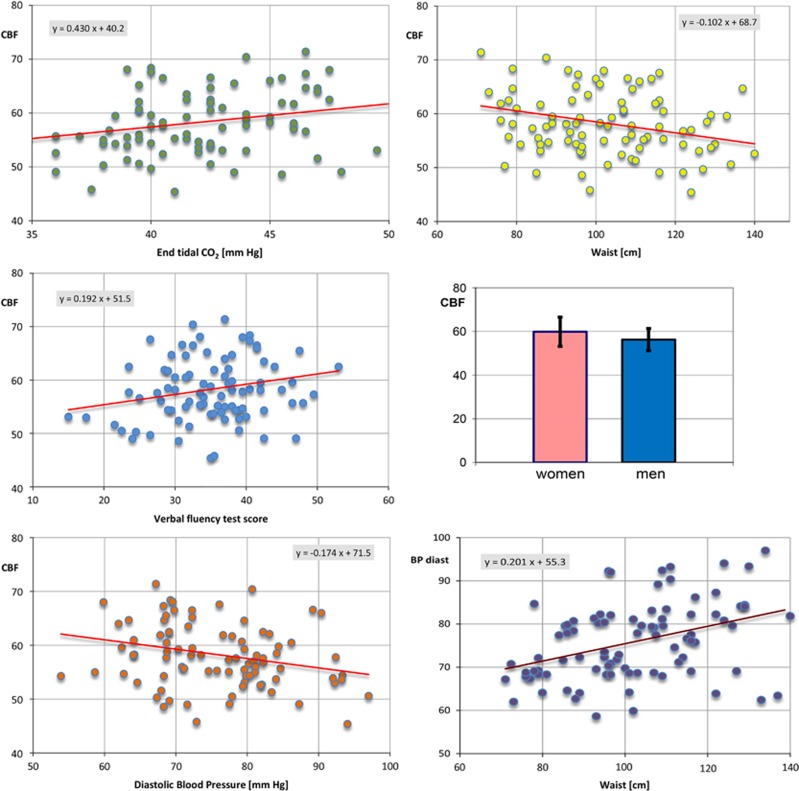

The GM CBF in mL/100 g per minute was normally distributed as shown with Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. The mean value was 58.3, standard deviation 6.3, and range 45.4 to 80.1. Table 3 lists 20 variables tested as potential predictors of CBF (the dependent variable) using simple linear regressions, i.e., regressed one at the time. In order of decreasing significance, an association was found between CBF and: sex, waist circumference, diastolic BP, end tidal CO2, verbal fluency score, and BMI (Table 3). The first five panels of Figure 3 plot the relationship between CBF and some of the variables that were significantly associated with cortical perfusion.

Figure 3.

The relationship between cerebral blood flow (CBF) in mL/100 g per minute and variables: end tidal CO2, waist circumference, verbal fluency test score, sex (mean and standard deviations for women 59.9±6.7 and for men 56.2±5.1), and diastolic blood pressure. Also plotted is the relationship between waist circumference and diastolic blood pressure.

Many of the 20 predictors are strongly correlated. For example, all metabolic variables (HOMA, QUICKI, INSULIN, HbA1c, and GLUCOSE), both obesity measures (WAIST and BMI), and four out of five cognitive variables (IQ, COWAT, MEM, and STROOP) were mutually linearly correlated at P<0.001. Moreover, there were strong linear correlations (P<0.001) between obesity measures (WAIST and BMI) and BP and between obesity measures and metabolic measures. To avoid overfitting and reduce colinearity between independent variables, we tested a multiple regression model with five predictors (SEX, COWAT, CO2, BP_DIAST, and WAIST), yielding R2=0.27, F=5.89, P<0.001. In the five-variable model, BP_DIAST and WAIST are colinear (Figure 3, bottom-right panel).

Interactions with Diagnostic Groups

Cerebral blood flow differed significantly across the three diagnostic groups HC, IR, and T2DM, as shown by one-way ANOVA: F(2, 79)=4.26, P=0.018. Post hoc least squares difference analyses revealed a mean CBF decrease of 4.4 mL/100 g per minute in IR compared with control subjects (P=0.005), with no hypoperfusion in T2DM (P=0.312). These results are summarized as box plots in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The distribution of cerebral blood flow (CBF) in study groups: healthy control (HC), insulin resistance (IR), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The symbol *denotes significant difference in mean CBF according to Tukey's post hoc test, ANOVA. The dark lines in the middle of the boxes are the median values. The bottom (top) of the box indicates the 25th (75th) percentile, 95% of the data lie between the whiskers.

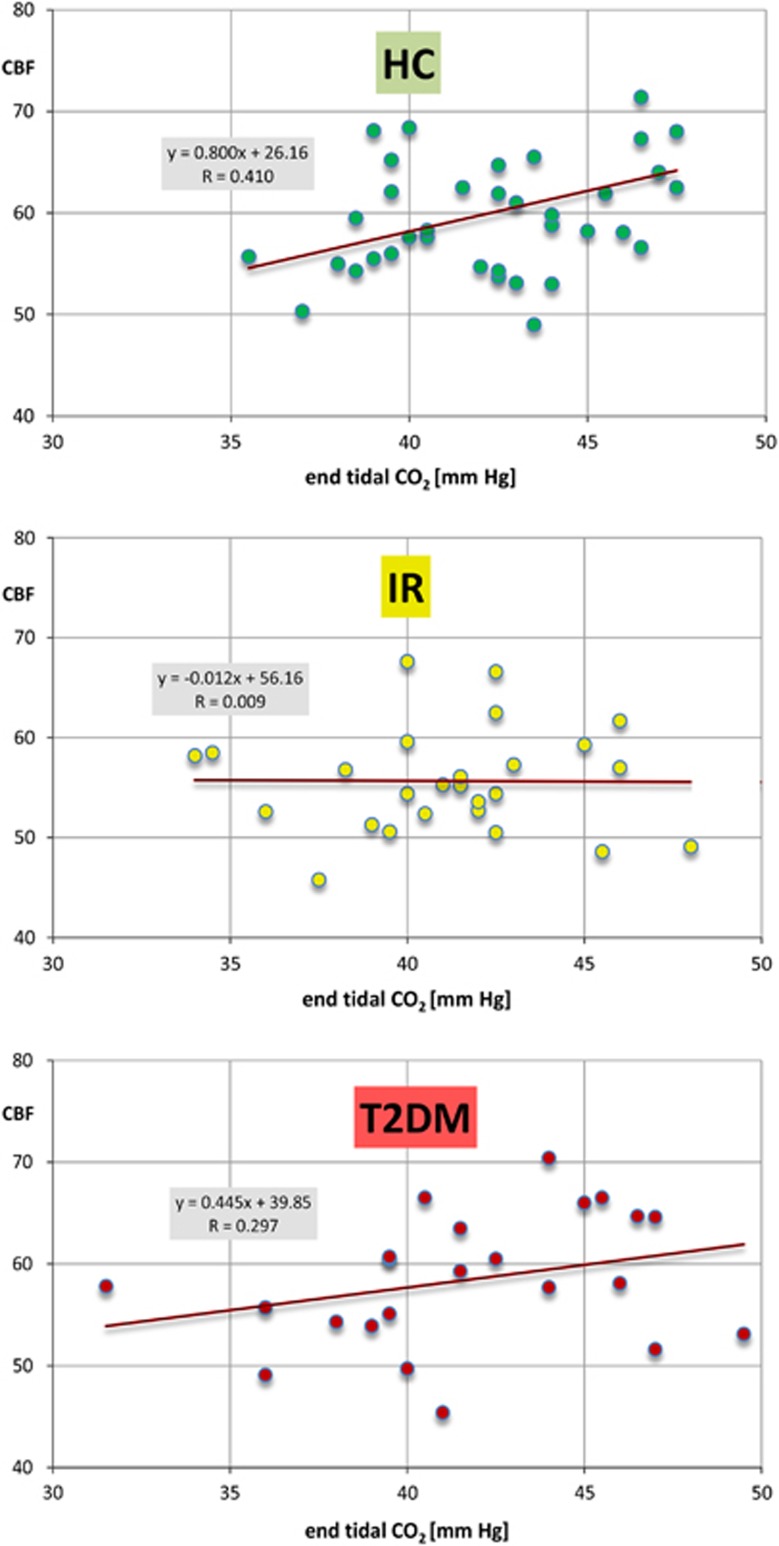

There was a significant interaction between group membership and end tidal CO2, but no group interaction for any other individual predictors of cortical CBF. Plots of GM perfusion versus end-tidal CO2 (Figure 5) support the notion that as a group, subjects with IR show no CO2 relationship (slope=−0.012) in the normocapnic range. This is in constrast to a strong relationship in healthy brains (slope=0.800) and intermediate response (slope=0.445) in diabetic patients.

Figure 5.

Gray-matter perfusion versus end-tidal CO2 in study groups: healthy control (HC) (top), insulin resistance (IR) (middle), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (bottom).

Discussion

When all 87 study subjects are considered together, we observed a significant relationship between resting CBF and end tidal CO2, sex, cognitive scores, obesity measures, and diastolic BP. End tidal CO2 used in our study is a commonly accepted surrogate for arterial CO2.30 It is well accepted that increasing arterial CO2 causes vasodilation and increases CBF. In young healthy adults, the response to changing CO2 concentration is estimated at ~1 to 2 mL/100 g per minute per unit CO2 rise in the 30 to 40 mm Hg range.31 The response is greater under hypercapnic conditions. Our results (Figures 3 and 5) indicate a lower response, with the overall slope equal to 0.43 mL/100 g per minute. It should be noted that our data do not reflect an active modification of subjects CO2 levels. Instead, we measured the effects of small, spontaneous CO2 variations. Spontaneous changes are most likely lower than changes that would be induced by inhalation of CO2. For example, Wise et al32 investigated the effect of spontaneous CO2 variations using trans-cranial Doppler, confirming the smaller effect of spontaneous as compared with induced CO2 changes. Lower response to changing CO2 could also reflect an aging effect: most of physiologic studies report cerebrovascular reactivity in healthy young adults, whereas our subjects were middle-aged.

Although commonly studied, the mechanism behind CO2 response is not completely understood. The effect is most likely due to the increase in perivascular pH and subsequent changes in intracellular calcium levels. There is also evidence that nitric oxide is an important mediator of CO2-related vasodilatation.33

In agreement with the literature34,35 we observed the dependence of resting cortical flow on sex. Cerebral blood flow in women is ~10% larger than in men. This phenomenon could be explained by ~10% lower hemoglobin and heamatocrit levels in women, combined with the hypothesis that CBF is regulated to maintain constant oxygen delivery across different hemoglobin levels.34,35

Our study showed a strong association between resting GM CBF and general cognitive functioning measured by multiple psychometric test scores. This association was not expected and it appears to be reported in only one other study. Takeuchi et al36 examined resting CBF in healthy young subjects and showed a significant direct correlation with psychometric score of intelligence. Such association is somewhat in conflict with the efficiency hypothesis that postulates increased general intelligence to be linked to efficient cognitive processing, i.e., reduced neural activity.37 However, efficiency hypothesis most often refers to neuronal activity while performing cognitive tasks, rather than to resting state.

We have also observed the effect of obesity and diastolic BP on cortical CBF. This effect is hard to interpret, as increased hypertension and obesity are highly correlated. The literature search yielded only one study38 reporting significant CBF reduction with increased BP. Interestingly, our study confirms the detailed findings of Waldstein et al, i.e., larger sensitivity to diastolic (versus systolic) BP and larger effect in men than in women.

While the multiple regression model based on variables SEX, WAIST, BP_DIAST, CO2, and COWAT explains only 27% of variance, our observation of independent detrimental effect of obesity and high BP (Figure 3) on resting cortical perfusion could have important implications.

Our main goal was to determine whether T2DM is associated with changes in cortical perfusion. We have also, for the first time, assessed the perfusion in subjects with IR but not with T2DM. We have observed a significant impairment in cortical flow in IR, with 7.5% lower mean CBF than in HC. There was no significant resting hypoperfusion in T2DM group, in agreement with the results of a large prospective ASL study by Novak et al.19

The majority of T2DM patients, but none of subjects with IR, were treated with blood glucose lowering medications. Moreover, 52.2% took statins compared with 7.4% in IR group, and 56.5% T2DM patients took medications to control their BP, compared with 11.1% among IR. Our finding could therefore be attributed to the beneficial effect of some of the medications, but many other plausible explanations can be offered. For example, our IR group included fewer women (52% females, compared with 61% females in T2DM group and 59% in HC group), and women show ~10% higher GM flow than men. However, adjustment for sex differences translates into <0.8% group effect, which is small compared with observed difference of 7.5%.

Another significant finding is reduced sensitivity to CO2 in IR groups, which again appears to be partially reversed in T2DM group. Cognitive deficits have been in the past described among individuals with normal fasting glucose levels but abnormal glucose tolerance. We have shown that carefully characterized non-diabetic middle-aged individuals with IR also show a CBF dysregulation. Cerebral blood flow changes appear to be reversed when the disease progresses to T2DM stage that is associated with aggressive use of medications.

One limitation of our study is the inclusion of relatively few subjects. The FAIR-based 2D ASL protocol used in this study took ~2.5 minutes per slice, which makes it impractical to examine the entire brain. However, the relatively high precision of the CBF measurements suggests that the acquisition exam may be performed with fewer than 48 repetitions, yielding faster throughput and larger coverage in future studies. Reduced acquisition matrix would be another way to achieve a faster protocol; however, lower-resolution increases partial volume effects and leads to inaccurate delineation of cortical ROI.

A potential limitation is the use of normally appearing WM as a reference tissue whose perfusion is assumed to be constant across subjects. Any departure of cerebral WM flow from its assumed value of 25 mL/100 g per minute will be a source of systematic CBF error. However, there is an attenuated effect of error in assumed value of WM flow on the GM flow.27

Our measurements of the resting cortical CBF in middle-age adults agree well with the cortical CBF distribution previously measured using PET 15O and other techniques (Table 1). However, the variability of our CBF technique (standard deviation ~6 mL/100 g per minute) is approximately two times better than the variability for competing methods. We attribute increased precision to the use of WM as the flow reference region. A prerequisite for accurate ASL measurement is that in the absence of flow, the signal strengths of control (slice-selective) image and labeled (non-selective) image be identical. This requirement is difficult to achieve because of imperfect inversion profiles. Constraining signal in the WM serves to reduce ASL errors.

In conclusion, our findings suggest significant CBF and vascular reactivity impairments in patients with IR short of T2DM. These impairments are to a large degree absent in the T2DM group. Further support for this finding will have to come from prospective longitudinal studies. It will be important to investigate whether improvements in CBF occur within individuals as they progress from IR to T2DM, and whether they are associated with improvements in cognitive functioning. Also of great interest would be to investigate the mechanism for this improvement, including the role of specific medications. By ascertaining that functional brain deficits are associated with obesity and high BP and that the deficits can be reversed, patients could be provided with great motivation to institute meaningful lifestyle changes.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This study was supported by grant DK064087 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307:491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozumdar A, Liguori G. Persistent increase of prevalence of metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults: NHANES III to NHANES 1999-2006. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:216–219. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ervin RB. National Health Statistics Reports. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Maryland, USA; 2009. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adults 20 years of age and over, by sex, age, race and ethnicity, and body mass index: United States, 2003-2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad N, Gagnon M, Messier C. The relationship between Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes, and cognitive function. J Clin Exper Neuropsych. 2004;26:1044–1080. doi: 10.1080/13803390490514875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl H, Sweat V, Hassenstab J, Polyakov V, Convit A. Cognitive impairment in nondiabetic middle-aged and older adults is associated with insulin resistance. J Clin Exper Neuropsych. 2010;32:487–493. doi: 10.1080/13803390903224928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau PL, Javier DC, Ryan CM, Tsui WH, Ardekani BA, Ten S, et al. Preliminary evidence for brain complications in obese adolescents with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2010;53:2298–2306. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1857-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau PL, Castro MG, Tagani A, Tsui WH, Convit A. Obesity and metabolic syndrome and functional and structural brain impairments in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e856–e864. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg E, Reijmer YD, de Bresser J, Kessels RP, Kappelle LJ, Biessels GJ, et al. A 4 year follow-up study of cognitive functioning in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2010;53:58–65. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1571-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusinek H, Endo Y, De Santi S, Frid D, Tsui W-H, Segal S, et al. Atrophy rate in medial temporal lobe during progression of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2004;63:2354–2359. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000148602.30175.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manschot SM, Brands AM, van der Grond J, Kessels RP, Algra A, Kappelle LJ, et al. Brain magnetic resonance imaging correlates of impaired cognition in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55:1106–1113. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Harten B, Oosterman J, van Loon BJ, Scheltens P, Weinstein HC. Brain lesions on MRI in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur Neurol. 2007;57:70–74. doi: 10.1159/000098054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl H, Wolf OT, Sweat V, Tirsi A, Richardson S, Convit A. Modifiers of cognitive function and brain structure in middle-aged and elderly individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Brain Res. 2009;1280:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convit A, Wolf OT, Tarshish C, de Leon MJ. Reduced glucose tolerance is associated with poor memory performance and hippocampal atrophy among normal elderly. PNAS. 2003;100:2019–2022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336073100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convit A. Links between cognitive impairment in insulin resistance: An explanatory model. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris DM, Houben AJ, Schram MT, Stehouwer CDA. Microvascular dysfunction is associated with a higher incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:3082–3094. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandona P, James IM, Newbury PA, Woolard ML, Beckett AG. Cerebral blood flow in diabetes mellitus: evidence of abnormal cerebrovascular reactivity. Br Med J. 1978;2:325–326. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6133.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brundel M, van den Berg E, Reijmer YD, de Bresser J, Kappelle LJ, Biessels GJ. Cerebral haemodynamics, cognition and brain volumes in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak V, Last D, Alsop DC, Abduljalil AM, Hu K, Lepicovsky L, et al. Cerebral blood flow velocity and periventricular white matter hyperintensities in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1529–1534. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak V, Zhao P, Manor B, Sejdic E, Alsop D, Abduljalil A. Adhesion molecules, altered vasoreactivity, and brain atrophy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2438–2441. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asllani I, Habeck C, Scarmeas N, Borogovac A, Brown TR, Stern Y. Multivariate and univariate analysis of continuous arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI in Alzheimer's disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:725–736. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin W, Horowitz S, Ragin A, Chen Y, Walker M, Carroll TJ. Quantitative cerebral perfusion using dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI: evaluation of reproducibility and age- and gender-dependence with fully automatic image postprocessing algorithm. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:1232–1241. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostrup E, Knudsen GM, Law I, Holm S, Larsson HBW, Paulson OB. The relationship between cerebral blood flow and volume in humans. Neuroimage. 2005;24:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1136–1139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Sullivan G, Quon MJ. Assessing the predictive accuracy of QUICKI as a surrogate index for insulin sensitivity using a calibration model. Diabetes. 2005;54:1914–1925. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss A, Martirosian P, Klose U, Nagele T, Claussen CD, Schick F. FAIR-TrueFISP imaging of cerebral perfusion in areas of high magnetic susceptibility differences at 1.5 and 3 Tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25:924–931. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JS, Siowa B, Lythgoe MF, Thomas DL. The importance of RF bandwidth for effective tagging in pulsed arterial spin labeling MRI at 9.4T. NMR Biomed. 2012;25:1139–1143. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusinek H, Brys M, Glodzik L, Switalski R, Tsui W-H, Haas F, et al. Hippocampal blood flow in normal aging measured with ASL at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65:128–137. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody DM, Thore CR, Anstrom JA, Challa VR, Langefeld CD, Brown WR. Quantification of afferent vessels shows reduced brain vascular density in subjects with leukoaraiosis. Radiology. 2004;233:883–890. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2333020981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law I, Iida H, Holm S, Nour S, Rostrup E, Svarer C, et al. Quantitation of regional cerebral blood flow corrected for partial volume effect using O-15 water and PET: II. Normal values and gray matter blood flow response to visual activation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:1252–1263. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200008000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSwain SD, Hamel DS, Smith B, Gentile MA, Srinivasan S, Meliones JN, et al. End-tidal and arterial carbon dioxide measurements correlate across all levels of physiologic dead space. Respir Care. 2010;55:288–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peebles KC, Richards AM, Celi M, McGrattan K, Murrell CJ, Anslie PN. Human cerebral arteriovenous vasoactive exchange during alterations in arterial blood gases. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1060–1068. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90613.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RG, Ide K, Poulin MJ, Tracey I. Resting fluctuations in arterial carbon dioxide induce significant low frequency variations in BOLD signal. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1652–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavi S, Egbarya R, Lavi R, Jacob G. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of cerebral blood flow in humans: chemoregulation versus mechanoregulation. Circulation. 2003;107:1901–1905. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000057973.99140.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen OM, Kruuse C, Olesen J, Jensen LT, Larsson HB, Birk S, et al. Sources of variability of resting cerebral blood flow in healthy subjects: a study using ¹33Xe SPECT measurements. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:787–792. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhu X, Feinberg D, Guenther M, Gregori J, Weiner MW, et al. Arterial spin labeling MRI study of age and gender effects on brain perfusion hemodynamics. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68:912–922. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi H, Taki Y, Hashizume H, Sassa Y, Nagase T, Nouchi R, et al. Cerebral blood flow during rest associates with general intelligence and creativity. PLoS ONE. 2001;6:e25532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer AC, Fink A, Schrausser DG. Intelligence and neural efficiency: the influence of task content and sex on the brain-IQ relationship. Intelligence. 2002;30:515–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldstein SR, Lefkowitz DM, Siegel EL, Rosenberger WF, Spencer RJ, Tankard CF, et al. Reduced cerebral blood flow in older men with higher levels of blood pressure. J Hypertension. 2010;28:993–998. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e328335c34f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]