Background: CMP-pseudaminic acid formation and role in Bacillus thuringiensis flagellin glycosylation are unknown.

Results: Seven enzymes are required to convert UDP-N-acetylglucosamine to CMP-pseudaminic acid; UDP-N-acetylglucosamine is converted to UDP-6-deoxy-d-N-acetylglucosamine-5,6-ene and then to UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-N-acetylaltrosamine.

Conclusion: Two previously undescribed enzymes initiate the CMP-pseudaminic acid pathway.

Significance: Identifying a unique CMP-pseudaminic acid pathway in a Gram-positive bacterium may provide new opportunities to control bacterial flagellin glycosylation and pathogenicity.

Keywords: Bacillus, Bacterial Metabolism, Carbohydrate Biosynthesis, Enzyme Catalysis, Glycobiology, CMP-Pseudaminic Acid, UDP-GlcNAc, Aminotransferase, Dehydratase

Abstract

CMP-pseudaminic acid is a precursor required for the O-glycosylation of flagellin in some pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria, a process known to be critical in bacterial motility and infection. However, little is known about flagellin glycosylation in Gram-positive bacteria. Here, we identified and functionally characterized an operon, named Bti_pse, in Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis ATCC 35646, which encodes seven different enzymes that together convert UDP-GlcNAc to CMP-pseudaminic acid. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria complete this reaction with six enzymes. The first enzyme, which we named Pen, converts UDP-d-GlcNAc to an uncommon UDP-sugar, UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene. Pen contains strongly bound NADP+ and has distinct UDP-GlcNAc 4-oxidase, 5,6-dehydratase, and 4-reductase activities. The second enzyme, which we named Pal, converts UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene to UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. Pal is NAD+-dependent and has distinct UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene 4-oxidase, 5,6-reductase, and 5-epimerase activities. We also show here using NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry that in B. thuringiensis, the enzymatic product of Pen and Pal, UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc, is converted to CMP-pseudaminic acid by the sequential activities of a C4″-transaminase (Pam), a 4-N-acetyltransferase (Pdi), a UDP-hydrolase (Phy), an enzyme (Ppa) that adds phosphoenolpyruvate to form pseudaminic acid, and finally a cytidylyltransferase that condenses CTP to generate CMP-pseudaminic acid. Knowledge of the distinct dehydratase-like enzymes Pen and Pal and their role in CMP-pseudaminic acid biosynthesis in Gram-positive bacteria provides a foundation to investigate the role of pseudaminic acid and flagellin glycosylation in Bacillus and their involvement in bacterial motility and pathogenicity.

Introduction

Bacillus thuringiensis is a Gram-positive bacterium that has been isolated from diverse habitats, including soil, water, dust, plants, cadavers, and the intestines of insects (1–5). B. thuringiensis belongs to the Bacillus cereus group, which includes the two most notable pathogens B. cereus and Bacillus anthracis, the causal agents of food poisoning and anthrax, respectively (6). Members of this group have similar genetic backgrounds but are distinguished by their host specificities and their pathogenicity (7). For example, B. thuringiensis is characterized by its ability to form crystalline proteins (Bt toxin) that are lethal to many insects (8). Indeed, B. thuringiensis is used widely to control agricultural pests, including Lepidoptera, Diptera, and Coleoptera sp. (9), and may also have a role in controlling Anopheles gambiae, the principal vector of malaria (10).

B. thuringiensis as well as other Bacillus species are known to exist in the gut microflora of numerous insects (11, 12). In this environment, some of these bacteria lose their flagella and become attached to the intestinal epithelium of insects (13). Recent cell biology studies have identified B. thuringiensis israelensis flagellum structures (7), and genomic analyses revealed that the bacterium has all of the protein components required to make flagellum and promote motility (14–16). Nevertheless, the role of flagellum structures in Bacillus and its involvement in delivering the Bt toxin to the insect gut, or in pathogenicity, remains to be determined.

Flagellin, one of the proteins of the flagellum apparatus, is a globular protein monomer that stacks helically in the form of a hollow cylinder to build the filament of the flagellum (17–19). Studies of Bacillus sp. PS3 flagellin have shown that it is O-glycosylated, although the sugar involved in this modification was not identified (20). The results of preliminary studies in our laboratory2 have indicated that in B. thuringiensis israelensis the flagellin is glycosylated with a sugar residue having a mass consistent with a diacetylaminotetradeoxy-nonulosonic acid.

Several studies have shown that flagella are essential for motility, adhesion, host interactions, and secretion during many of the life stages of Gram-negative bacteria (21, 22). In Campylobacter spp. and Helicobacter pylori, the central domain of flagellin is post-translationally modified by the addition of pseudaminic acid (5,7-diacetamido-3,5,7,9-tetradeoxy-l-glycero-α-l-manno-2-nonulopyranosonic acid, Pse3) (23, 24) that is O-linked to serine or threonine residues (25). Mutants lacking glycosylated flagellin are affected in both their motility and their ability to infect their host (26).

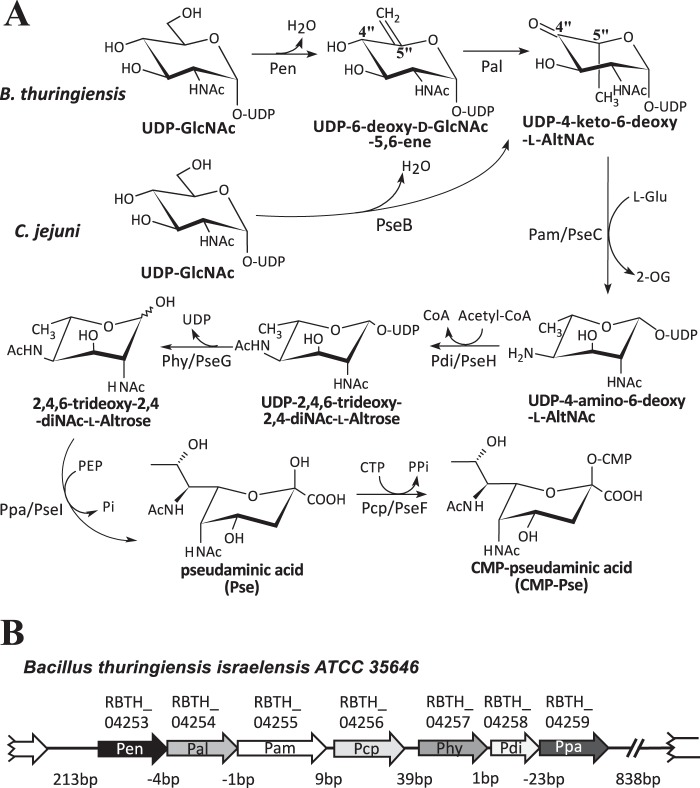

Interest in the function of Pse in Gram-negative bacteria led to the identification of a biosynthetic pathway, named pse, where CMP-pseudaminic acid (CMP-Pse) is formed from UDP-GlcNAc (27–29). This pathway involves six enzymes (Fig. 1A). A single bifunctional 4,6-dehydratase/5-epimerase (PseB) converts UDP-d-GlcNAc to UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc, which is then aminated at C4″ and N-acetylated to form UDP-2,4,6-trideoxy-2,4-NAc-l-altrose. UDP is cleaved from the sugar and pyruvate is added to form Pse. Pse is then activated by the addition of CMP to form CMP-Pse. By contrast, little is known about CMP-Pse formation in Gram-positive bacteria.

FIGURE 1.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway of CMP-Pse in the Gram-positive strain B. thuringiensis israelensis ATCC 35646 (Bti) requires seven proteins, whereas six are needed in Gram-negative C. jejuni. A, in the C. jejuni pathway, a single enzyme PseB converts UDP-2-deoxy-2-acetoamido-d-glucose, UDP-d-GlcNAc, to UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. In the B. thuringiensis pathway, two enzymes are needed. First, Pen converts UDP-GlcNAc with enzyme-bound NAD+ to UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene, and then Pal converts it to UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. From this point, both pathways carry out similar enzymatic reactions (although the amino acid sequence for each specific enzyme is not conserved between species, see Table 1) leading to the final product of CMP-Pse. B, organization of the seven-genes pse operon and flanking regions in B. thuringiensis israelensis ATCC 35646. The locus number for each enzyme-encoding gene in the operon is shown.

Here, we report the identification of the B. thuringiensis pse operon and the functional characterization of the enzyme cluster that converts UDP-GlcNAc to CMP-Pse. Seven enzymes are required for the conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to CMP-Pse in B. thuringiensis (Fig. 1B), unlike Gram-negative bacteria that complete this reaction with six enzymes. Two dehydratase-like activities, which we named Pen and Pal, initiate the Pse pathway in B. thuringiensis. We used a combination of NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry to show that Pen converts UDP-d-GlcNAc to UDP-2-acetamido-6-deoxy-α-d-xylo-hexopyranose-5,6-ene (herein abbreviated UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene) and that Pal converts UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene to UDP-2-acetamido-2,6-dideoxy-β-l-arabino-hex-4-ulose (herein abbreviated UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc). Only one enzyme, PseB, is required to convert UDP-d-GlcNAc to UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc in Gram-negative bacteria. The identification of Pen and Pal and the CMP-Pse biosynthetic pathway in B. thuringiensis provides a basis for determining the biological role of Pse in flagellin glycosylation in Gram-positive bacterium.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and Culture Conditions

The B. thuringiensis israelensis ATCC 35646 used in this study was stored in 16% glycerol at −80 °C, streaked onto agar medium, and grown for 18 h at 30 °C. The media (agar or liquid) used were Luria Bertani (LB) (10 g/liter tryptone, 5 g/liter yeast extract, 10 g/liter NaCl) and LB-Lennox (10 g/liter peptone, 10 g/liter NaCl, 5 g/liter yeast extract). Escherichia coli DH10B cells were used for cloning, and Rosetta2(DE3)pLysS (Novagen) cells were used to express protein.

Cloning Genes of the Pse Operon

A single colony of B. thuringiensis growing on LB-Lennox agar was suspended in 50 μl of sterile water, heated for 5 min at 95 °C, and then centrifuged (10,000 × g, 30 s). A portion of the supernatant (5 μl) was used as the source of DNA to amplify each specific gene by PCR. Each primer was designed to include a 15-nucleotide extension with exact sequence homology to the cloning site of the target plasmid at the 5′ end. This facilitated cloning between the NcoI and HindIII sites of pET28a (Novagen) and pET28_Tev (30) and the BamHI and AflII sites of pCDFDuet-1 (Novagen). The individual genes (rbth_04253, rbth_04254, rbth_04255, rbth_04256, rbth_04257, rbth_04258, and rbth_04259) were PCR-amplified using high fidelity Pyrococcus DNA polymerase (0.4 units of Phusion Hot Start II; ThermoScientific) and included buffer, dNTPs (0.4 μl 10 mm), B. thuringiensis DNA template (5 μl) as well as PCR primer sets (1 μl each of 10 μm) in a 20-μl reaction volume. The PCR conditions were a 98 °C denaturation cycle for 30 s followed by 25× cycles (8 s of denaturation at 98 °C, 25 s of annealing at 54 °C, and 20 s of elongation at 72 °C) at 4 °C. A similar PCR was used to amplify the expression plasmid using specific inverse-PCR primer sets. pET28a was amplified with primer set ZL089 (5′-catggtatatctccttcttaaagttaaac-3′) and ZL090 (5′-aagcttgcggccgcactcgagcaccacc-3′). rbth_04254, rbth_04256, rbth_04257, and rbth_04259 were amplified with the following primer sets: ZL275 (5′-gaaggagatataccatgaaaatattagtaactggtggtgcag-3′) and ZL276 (5′-gtgcggccgcaagcttctctttctccttaggattaatttttaaag-3′); ZL421 (5′-gaaggagatataccatggtgttattaaaattgcaaaaccaaaaattg-3′) and ZL422 (5′-gtgcggccgcaagctttaatatcgtttctctatttaactcatc-3′); ZL418 (5′-gaaggagatataccatgcttgagaaaaaaattgcctttcg-3′) and ZL419 (5′-gtgcggccgcaagctttcctcctaaaatattttttgctatttc-3′); and ZL277 (5′-aggagatataccatgaaggtgaaaaaaatgagtaatgtatatatcg-3′) and ZL278 (5′-gtgcggccgcaagcttaattaaatcccatgaaacaggcg-3′), respectively. pET28b-Tev was amplified with primer sets ZL169 (5′-catggcgccctgaaaatacaggttttcgcc-3′) and ZL170 (5′-tagggatccctagggtaccctagcggccgc-3′). rbth_04255 was amplified with primer sets ZL281 (5′-tttcagggcgccatggtaaggggaatcctcggtatgc-3′) and ZL282 (5′-ccctagggatccctaatttttagcaactctataaaacgaaagaac-3′). pCDFDuet-1 was amplified with primers ZL269 (5′-cggatcctggctgtggtgatgatg-3′) and ZL270 (5′-taatgcttaagtcgaacagaaagtaatcg-3′), and genes rbth_04253 and rbth_04258 were amplified by primer sets ZL271 (5′-cacagccaggatccgttttttaaagataaaaatgttttaattattgg-3′), ZL272 (5′-tcgacttaagcattatattttctcccctcctgttaatagc-3′), and ZL273 (5′-cacagccaggatccgttagatattgaggattttcaattgg-3′), and set ZL274 (5′-tcgacttaagcattactcatttttttcaccttcaagttc-3′), respectively. After PCR, portions (2 μl each) of the amplified vector and insert were mixed and treated for 15 min at 37 °C with 0.5 units of FastDigest DpnI (ThermoScientific) and then transformed into DH10B (Invitrogen)-competent cells. Positive clones were selected on LB agar containing either kanamycin (50 μg/ml, for pET vector) or spectinomycin (50 μg/ml, for pCDF vector). Clones were verified by PCR and DNA sequencing. Plasmids harboring specific genes were sequenced, and the DNA sequences were deposited in GenBankTM (with respective accession numbers KM433664 and KM433665). The resulting recombinant plasmids are as follows: pCDF:His6RBTH_04253 yielding N-terminal His6-tagged Pen; pET28a:RBTH_ 04254His6 yielding C-terminal Pal; pET28b:His6-TevRBTH_04255 yielding N-terminal His6 tag followed by Tev-protease and Pam; pET28a:RBTH_04256His6 yielding C-terminal His6-tagged Pcp; pET28a:RBTH_04257His6 yielding C-terminal His6-tagged Phy; pCDF:His6RBTH_04258 yielding N-terminal His6-tagged Pdi; and pET28a:RBTH_04259His6 yielding C-terminal His6-tagged Ppa. Plasmids were extracted by PureLink quick plasmid miniprep kit (Invitrogen) and transformed into Rosetta2(DE3)pLysS competent cells for recombinant protein expression.

His6-tagged Protein Expression and Purification

Rosetta2(DE3)pLysS strains harboring expression plasmids were grown at 37 °C and 250 rpm in 250 ml of LB supplemented with chloramphenicol (35 μg/ml) and kanamycin (50 μg/ml) for the pET28a and pET28b vectors or with chloramphenicol (35 μg/ml) and spectinomycin (50 μg/ml) for the pCDF vector. Gene expression was induced when cell A600 reached 0.6 by adding 0.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. After induction, cells were grown for 18 h at 18 °C and 250 rpm and then harvested by centrifugation (6,000 × g) for 10 min at 4 °C. The cell pellets were washed with water and then suspended in 10 ml of lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mm EDTA, 2 mm DTT, and 0.5 mm PMSF). Cells were lysed by sonication (31), and after centrifugation (6,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C), the supernatant was supplemented with 1 mm DTT and 0.5 mm PMSF and re-centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. An aliquot (5 ml) of the supernatant was applied to a nickel-Sepharose fast-flow column (GE Healthcare; 2 ml of resin packed in a polypropylene column; inner diameter 1 × 15 cm). Each column was pre-equilibrated with buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 100 mm NaCl). The column was washed with 30 ml of buffer A containing 20 mm imidazole and then with 10 ml of buffer A containing 40 mm imidazole. His-tagged proteins were eluted with 5 ml of buffer A containing 250 mm imidazole. The eluates containing these proteins were divided into small aliquots, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at −80 °C. The concentration of each protein was determined (32) from the A280 nm (with ϵ = 14,200 cm−1 m−1 for His6RBTH_04253, ϵ = 40,120 cm−1 m−1 for RBTH_04254His6). Proteins were separated by SDS-12.5% PAGE and visualized by staining with Coomassie Blue.

Enzyme Reactions

The activity of recombinant His6RBTH_04253 (herein referred to as Pen) was examined by HILIC-HPLC with UV or electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) detection and by time-resolved 1H NMR spectroscopy. For HPLC-based assays, the total reaction volume was 50 μl and included 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 1 mm UDP-GlcNAc, and about 1.5 μg of purified Pen. Reactions proceeded for 1 h at 30 °C, followed by enzyme inactivation (95 °C for 2 min) and extraction with 50 μl of chloroform (30). An aliquot (20 μl) of the upper aqueous layer was removed and mixed with acetonitrile (40 μl) and 0.5 m ammonium acetate, pH 5.3 (2 μl). A portion (20 μl) was analyzed using HILIC coupled to a ESI-MS/MS mass spectrometer or a UV diode array detector. ESI-MS/MS was performed using a Shimadzu LC-MS/MS IT-TOF MS system operating in the negative ion mode with a Nexera UFPLC LC-30AD pump, autosampler (Sil30), and column heater (set to 37 °C). HPLC with UV detection was carried out with an Agilent 1260 pump system equipped with an autosampler, column heater (set at 37 °C), and diode array detector (A261 nm). Enzyme reactions were separated on an Accucore 150-amid HILIC column (150 × 4.6 mm, 2.6 μm particle size, ThermoScientific) using 40 mm ammonium acetate, pH 4.3 (solvent A), and acetonitrile (solvent B). The column was equilibrated at 0.4 ml/min with 25% solvent A and 75% solvent B prior to sample injection (20 μl). Following injection, the HPLC conditions were 0–1 min, 0.4 ml/min with 25% solvent A, 75% solvent B and then a gradient to 50% solvent A and 50% solvent B over 24 min. The flow rate was then increased to 0.6 ml/min with a gradient to 25% solvent A and 75% solvent B over 5 min. The column was then washed for 5 min with 25% solvent A, 75% solvent B before the next injection. HPLC peaks of enzymatic reaction products detected by their A261 nm (maximum for UDP-sugars) were collected, lyophilized, and suspended in D2O (99.9%) for NMR analysis or in H2O for MS/MS analysis.

The activity of recombinant RBTH_04254His6 (herein refer as Pal) was examined by HILIC-HPLC-UV, ESI-MS and time-resolved proton NMR. The 50 μl of HPLC-based assays included 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, about 1 mm of the product (purified by HILIC) formed by Pen and 8.5 μg of purified Pal. The reaction proceeded for 1 h at 30 °C, followed by inactivation (95 °C for 2 min) and chloroform extraction.

NMR-based Pen assays in a total volume of 180 μl were performed in a mixture of 90 μl of D2O and 90 μl of H2O containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 1 mm UDP-GlcNAc, 0.1 mm 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate (DSS) (which served as NMR reference), and ∼3 μg of purified Pen. The reaction mixture was transferred to a 3-mm tube and time-resolved 1H NMR spectra were then obtained for up to 2 h at 30 °C using a Varian DirectDrive 600-MHz spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic probe. Data were acquired before the addition of the enzyme at time 0 (t0). After adding the enzyme, data acquisition was started after ∼5 min to provide sufficient time to optimize magnet shimming. Sequential one-dimensional proton spectra (32 scans each) with presaturation of the water resonance were acquired over the course of the enzymatic reaction. All NMR spectra were referenced to the resonance of DSS set at 0.00 ppm.

NMR-based Pal assays in a total volume of 180 μl were performed in 90 μl of D2O and 90 μl of H2O containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, ∼1 mm of the product formed by Pen, 0.1 mm DSS, and about 17 μg of purified Pal. Time-resolved 1H NMR acquisition was as described above.

Kinetic Studies

The linear dependence of enzyme concentration with respect to initial velocity was established by changing the protein concentration and maintaining the substrates at constant concentration. Km values were determined using regression analysis (nonlinear) with Prism software from plots of initial velocities versus varied substrate concentrations (10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 150, 300, and 500 μm UDP-GlcNAc).

Gel Filtration Assays

Purified Pen or Pal protein (in volume of 300 μl) was mixed with 50 μm UDP-GlcNAc and chromatographed on a Superdex-75 column (1 cm inner diameter × 30 cm, GE Healthcare) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, using 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mm NaCl buffer. Peaks observed at 215 nm were collected and assayed for enzyme activity. The column was calibrated using a molecular mass standard (Bio-Rad).

Determination of Pen and Pal Enzyme-bound Co-factors

Purified Pen (600 μl of 0.63 mg/ml) and purified Pal (1.2 ml of 1.62 mg/ml) were heated for 5 min at 95 °C and then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 1 min. The supernatant was collected and concentrated to 100 μl using a SpeedVac (Savant SC110). A 30-μl aliquot was analyzed by HILIC-ESI-MS/MS for the detection of NAD+ or NADP+. Both positive mode and negative mode were used with 25% collision-induced dissociation energy for MS/MS fragmentation.

NMR Spectroscopy Used to Characterize Product Structures

The HPLC peak corresponding to the enzymatic product of Pen was collected, lyophilized, dissolved in D2O (99.9%), and analyzed by two-dimensional NMR. Proton chemical shifts were assigned by a correlation spectroscopy (COSY) experiment and verified by a total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) experiment. Protonated carbon chemical shifts as well as multiplicities were determined by a multiplicity-edited heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) experiment. The chemical shift of nonprotonated carbon C5″ was assigned by a heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) experiment.

To characterize the structure of the products formed by Pal, the reaction assay of Pal was extracted with chloroform, and the aqueous phase was chromatographed on a Q15 anion-exchange column as described (33). The peak corresponding to the product was collected, lyophilized, suspended in 99.9% D2O, and analyzed by COSY, TOCSY, HSQC, and HMBC experiments.

LC-MS/MS Analysis

Reaction products were chromatographed on a HILIC column using a Shimadzu CBM-20A HPLC system equipped with an autosampler, coupled to a Shimadzu LCMS-IT-TOF ESI mass spectrometer operated in the negative mode. The HILIC conditions were the same as the HPLC conditions described under “Enzyme Reactions.” Enzyme products were identified based on their retention time, the mass of their parent ion, and their mass spectral fragmentation pattern.

RESULTS

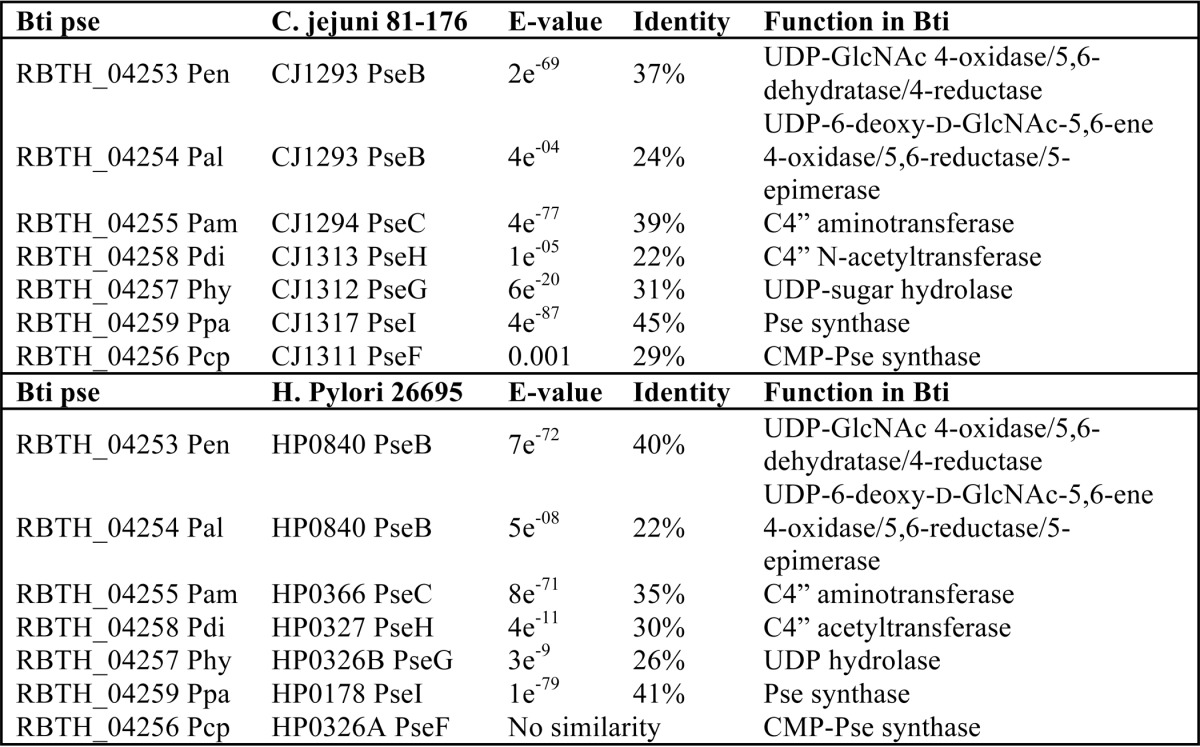

CMP-Pseudaminic Acid Operon in B. thuringiensis Consists of Seven Genes

We first performed a BLAST search using amino acid sequences of known bacterial enzymes involved in CMP-Pse formation to identify B. thuringiensis genes that may have a role in CMP-Pse formation. The BLAST approach, however, identified several misleading gene targets. For example, the first enzyme in the pseudaminic acid pathway in H. pylori is a bi-functional UDP-GlcNAc 4,6-dehydratase/5-epimerase (PseB) that forms UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. PseB has 46% amino acid sequence similarity (e-value 3e−84) to RBTH_05809 of B. thuringiensis israelensis ATCC 35646 and to Bc3750 of B. cereus ATCC 14579. However, Bc3750 was found not to encode a 5-inverting 4,6-dehydratase activity.4 RBTH_04253 (i.e. Pen) has a 40% amino acid sequence similarity to PseB (e-value 7e−72, see Table 1). Adjacent to the Pen is RBTH_04254 (Pal), annotated as a dehydratase (Fig. 1B), and has a low sequence identity to PseB (24%, see Table 1). RBTH_04255 (Pam), which has low (35%; e-value of 8e−71) amino acid identity with the functional aminotransferase PseC from H. pylori, follows the two annotated dehydratases. RBTH_04258 (Pdi) has low amino acid identity (30%; e-value of 4e−11) to the functional N-acetyltransferase PseH, whereas RBTH_04257 (Phy) has only 26% amino acid identity (e-value of 3e−9) to H. pylori PseG; RBTH_04259 (Ppa) shares sequence identity (41%; e-value of 1e−79) to H. pylori pseudaminic acid synthase PseI, and RBTH_04256 (Pcp) protein that shares very low sequence identity (29%; e-value 0.001) to functional pseudaminic acid cytidylyltransferase PseF from Campylobacter jejuni, although no similarity was detected compared with H. pylori PseF (see Table 1). Although the encoded proteins in this B. thuringiensis operon share an overall low amino acid sequence identity to known functional genes involved in CMP-Pse synthesis, we decided to clone and characterize these proteins because sugar (Pse) modification of flagella proteins has not been reported previously in Bacillus. Below, we describe that seven enzymes are required to form CMP-Pse from UDP-GlcNAc in B. thuringiensis (Fig. 1, A and B), unlike Gram-negative bacteria that complete this reaction with six enzymes (27).

TABLE 1.

Amino acid sequence similarity between various proteins involved in the synthesis of CMP-pseudaminic acid

Comparison of pse metabolic proteins between B. thuringiensis (Bti), C. jejuni, and H. pylori.

Biochemical Characterization of CMP-Pseudaminic Acid Operon in B. thuringiensis

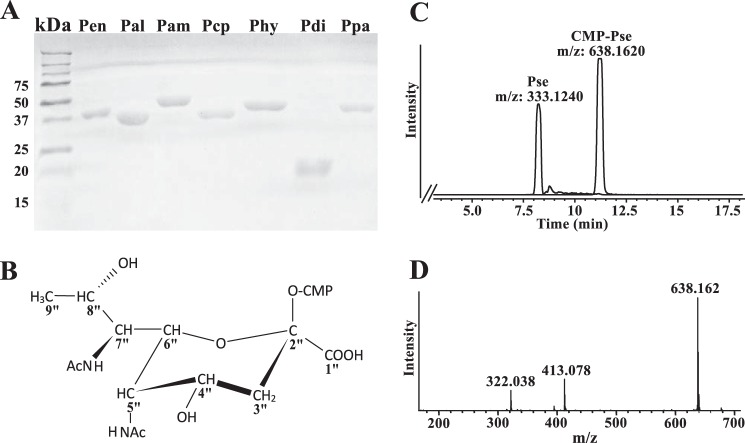

Each of the seven predicted Pse pathway genes were cloned from B. thuringiensis and expressed in E. coli as recombinant His6-tagged proteins. Each protein was purified over a nickel-affinity column. Individual protein bands for recombinant Pen (40 kDa), Pal (37.1 kDa), Pam (47.6 kDa), Pcp (39.5 kDa), Phy (42.8 kDa), Pdi (24 kDa), and Ppa (40.7 kDa) were detected by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2A). The ability of the recombinant enzymes to catalyze the various steps in the formation of CMP-Pse was then tested. As UDP-GlcNAc is the only commercially available substrate, we used the product formed by one enzyme as the substrate for the next enzyme. For example, recombinant Pen and Pal proteins were reacted with UDP-GlcNAc, and the product was then used as the substrate for Pam, the putative l-Glu:C4″-transaminase. The UDP-4-amino-sugar formed together with acetyl-CoA was the substrate for Pdi, an acetyl-CoA:C4″-N-acetyltransferase. The resulting product (UDP-2,4,6-trideoxy-2,4-diNAc-l-altrose) then served as the substrate for the UDP-sugar hydrolase Phy, whose reaction product, along with phosphoenolpyruvate and Ppa, led to Pse. In the final reaction, Pse was reacted with CTP and recombinant Pcp to generate CMP-Pse (structure shown in Fig. 2B). The progression of each reaction was monitored by LC-MS-based assays.

FIGURE 2.

Purification of the seven B. thuringiensis israelensis ATCC 35646 (Bti) recombinant enzymes and their involvement in the biosynthesis of CMP-Pse. A, SDS-PAGE analysis of each of the Bti CMP-Pse biosynthetic enzymes after nickel column purification. Protein standards are shown on the left in kDa. Lane 1, Pen (40 kDa); lane 2, Pal (37.1 kDa); lane 3, Pam (47.6 kDa); lane 4, Pcp (39.5 kDa); lane 5, Phy (42.8 kDa); lane 6, Pdi (24 kDa); and lane 7, Ppa (40.7 kDa). B, 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic analyses of the peak eluted from HILIC column at 11 min gives a product with chemical shift corresponding to CMP-Pse. The structure of CMP-Pse is shown (also see Table 2). C, LC-MS analysis of the final biochemical step converting CTP + Pse to CMP-Pse, as determined after separation of reaction product by HILIC column. The peaks with [M − H]− ions at m/z 638.1 and 333.1, respectively, corresponding to the predicted mass of CMP-Pse and Pse. D, MS/MS analysis at collision energy 25% of parent ion 638 (CMP-Pse) gives predicted ion fragments of Pse-phosphate (m/z 413) and CMP (322). The structure of CMP-Pse is shown.

HILIC-ESI-MS analysis of the products of the final enzymatic step (Fig. 2C) gave two peaks with retention times of 8.2 and 11.2 min and [M − H]− at m/z 333.12 and 638.16, respectively. These two values suggest a mass for a 9-carbon sugar and its nucleotide derivative CMP-diacetylaminotetradeoxy-nonulosonic acid, respectively. NMR analysis (Table 2) established that the peak eluting at 11.2 min is indeed CMP-5,7-diacetamido-3,5,7,9-tetradeoxy-l-glycero-α-l-manno-2-nonulopyranosonic acid (CMP-Pse). The enzymatic product is not CMP-legionaminic acid (CMP-Leg) or other CMP-9-carbon sugars such as CMP-Leg 4- and 8-epimers, as the coupling constant between H5″ and H6″ (1.5 Hz) is small (expected for CMP-Pse) and not large (10.3 Hz) (expected for CMP-Leg). Fragmentation of the ion at m/z 638.16 gave two ions with m/z 322.04 and 413.08, (Fig. 2D) corresponding to CMP and pseudaminic acid 1-phosphate, respectively, and is consistent with the presence of CMP-Pse. Likewise, the peak eluting at 8.2 min (Fig. 2C) with [M − H]− at m/z 333.12 is Pse.

TABLE 2.

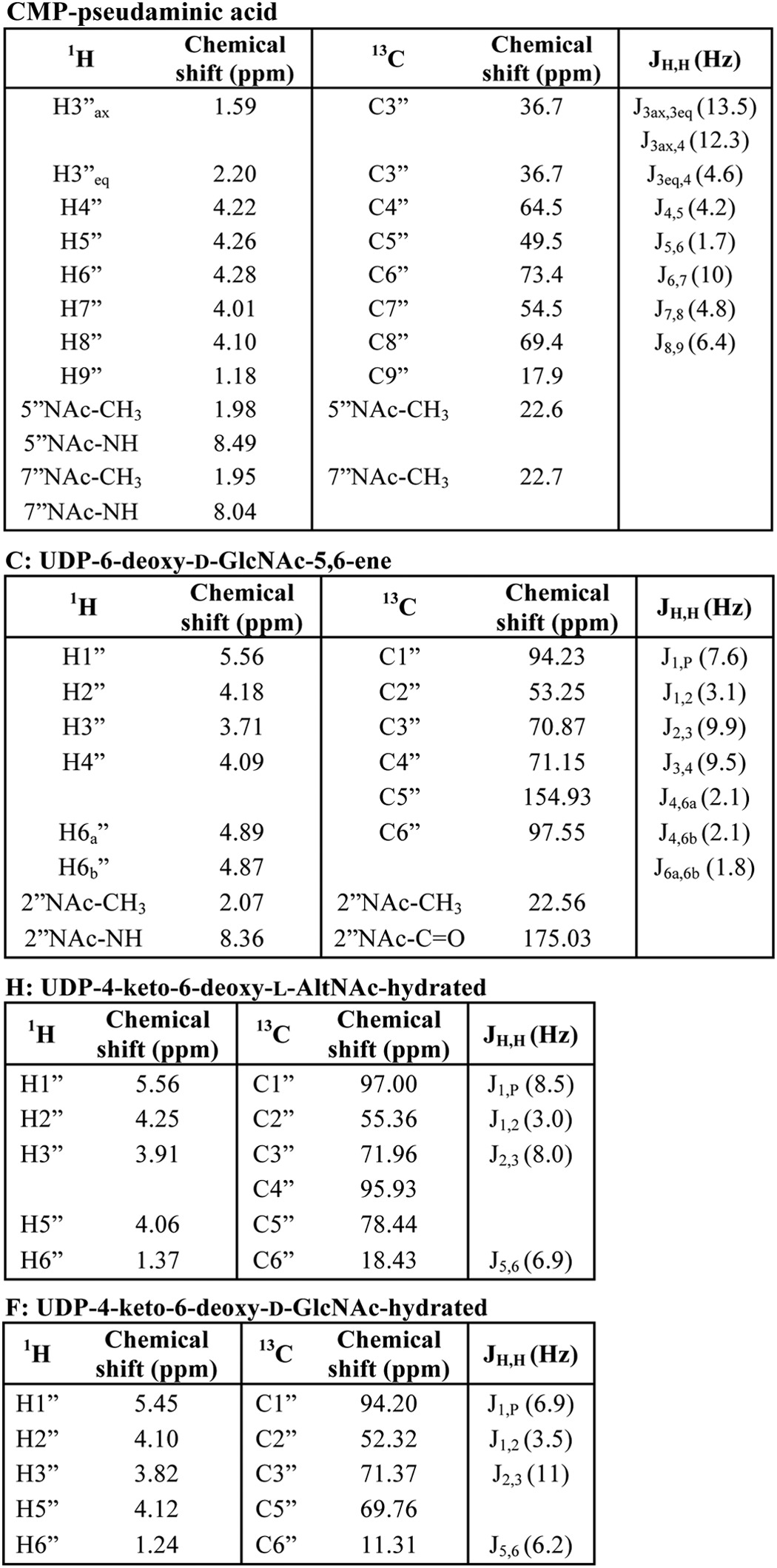

NMR data for the sugar moiety of CMP-Pse, product C, H, and F

We conclude that the seven-gene cluster between RBTH_04253 and 04259 in B. thuringiensis israelensis ATCC 35646 encodes all the enzymes required to convert UDP-GlcNAc to CMP-Pse (see Fig. 1A). Thus, we call this operon the Bti_Pse operon. Because the initial steps of the reaction involve two uncharacterized dehydratase-like enzyme activities, we fully characterized the activities of Pen and Pal.

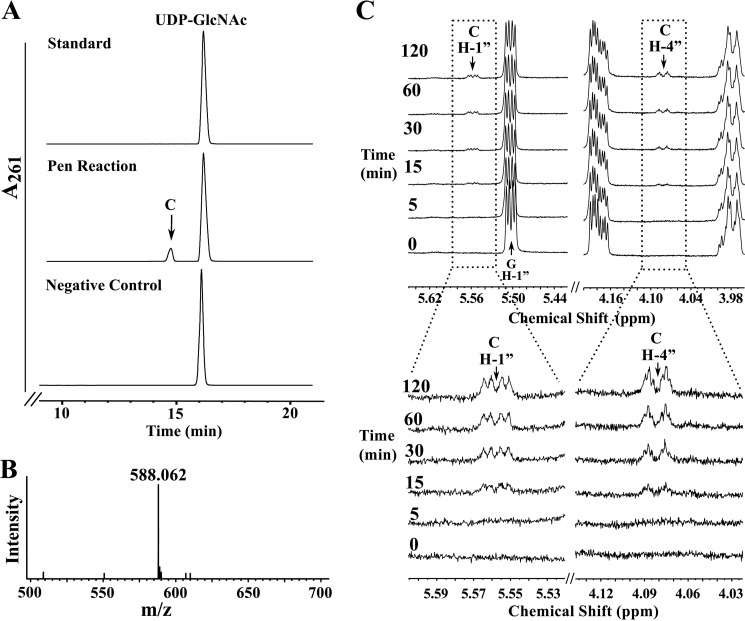

Characterization of a Unique UDP-Sugar, UDP-6-Deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene Formed by Pen, a UDP-GlcNAc 4-Oxidase/5,6-Dehydratase/4-Reductase

Our early analysis indicated that in B. thuringiensis two dehydratase-like proteins are required to initiate conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to a product that can be used for CMP-Pse formation. We therefore studied these two enzymes in more detail. Purified recombinant Pen (His6 RBTH_04253) was reacted with UDP-GlcNAc, and the products formed were analyzed by HILIC HPLC with UV detection. A new peak with a retention time of 14.5 min (Fig. 3A) was detected; a negative control reaction gave no new product. The peak was collected and examined by ESI-MS and MS/MS. The negative ion mode mass spectrum contained an ion [M − H]− at m/z 588.06 (Fig. 3B). MS/MS analysis of this ion gave two fragments at m/z 323 and 403 consistent with UMP and UDP, respectively, suggesting that the product was a UDP-sugar. The neutral loss of 18 atomic mass units suggests the UDP-GlcNAc product lacks the mass of water, implying that Pen is a dehydratase. However, further analysis of the enzyme product demonstrated that the enzyme is not a “regular” 4,6-dehydratase because no UDP-4-keto-sugar product was detected. Time-resolved 1H NMR of the reaction showed the conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to a new product (labeled C) with a quartet of signals at 5.56 ppm (Fig. 3C and see zoom below). We also observed that this product lacks signals for a C6-methyl and a C4-keto sugar. Most known 4,6-dehydratases form a 4-keto sugar with C6-methyl group (i.e. UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-sugar). Moreover, there was a new signal with a chemical shift of 4.09 ppm, which likely arose from the proton linked to C4″ of the UDP-sugar. This suggests that Pen is a 4-oxidase/5,6-dehydratase/4-reductase and forms a product that has a double bond between C5″ and C6″ (i.e. 5,6-ene). A detailed explanation of the elucidation of the structure of this product is provided below.

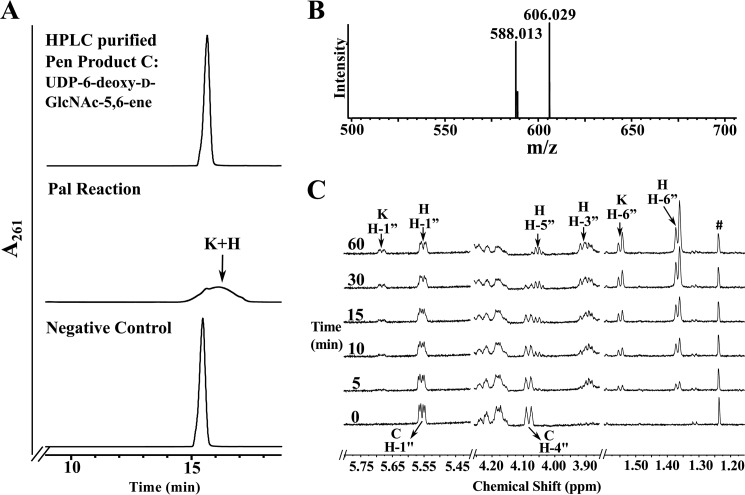

FIGURE 3.

Analyses of UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene, the enzymatic product of Pen by UV-HPLC, mass spectrometry, and time-resolved 1H NMR. A, purified Pen was reacted with UDP-GlcNAc (middle panel) to yield a new UV peak “C,” marked by an arrow. The top UV chromatogram trace in A corresponds to the standard of UDP-GlcNAc, and the lower trace is negative control showing incubation of irrelevant purified protein with UDP-GlcNAc. The peak C (eluting from HILIC-column at 14.6 min) was collected and characterized by NMR (see Fig. 5 and Table 2). B shows that the enzymatic product C gives a [M − H]− ion at m/z 588.1 corresponding to UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene. C, time-resolved 1H NMR showing Pen-enzymatic conversion of UDP-GlcNAc (G) to UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene (C). The selected chemical shift regions of the proton NMR spectrum that are diagnostic for the H-1″ anomeric protons of enzymatic reactant and product are shown between 5.44 and 5.64 ppm, and the diagnostic H-4″ peak of Pen-product C is shown between 4.18 and 3.98 ppm. A 3× zoom of the boxed regions is shown below in C.

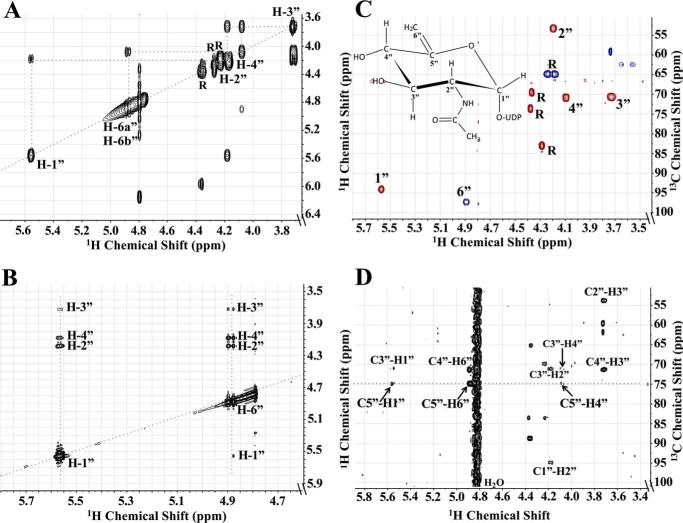

NMR Characterization of UDP-6-Deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene

Because the structure of the product from the Pen reaction could not be determined from the MS or time-resolved NMR experiments, the peak that eluted from the HILIC column at 14.5 min was collected and fully characterized by one- and two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. The one-dimensional proton NMR spectrum (Fig. 4) indicated that the product was UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene. Proton and carbon chemical shifts and proton coupling constants of the sugar moiety are listed in Table 2. The coupling constant between H1″ and H2″ was small (3.1 Hz), indicating an α-linkage to the phosphate of UDP. The coupling constant between H1″ and the phosphorus of the diphosphate was 7.6 Hz, which is consistent with a d-sugar. The coupling constants between H2″ and H3″ (9.9 Hz), along with H3″ and H4″ (9.5 Hz), confirmed that the sugar had the gluco configuration. The H2″ chemical shift at 4.18 ppm and the methyl proton resonance of the N-acetyl group (2″NAc) at 1.96 ppm are consistent with an acetamido moiety at the C2″. Two very diagnostic signal peaks for the C6″-methylene protons of product UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene were identified at 4.87 and 4.89 ppm. These peaks were assigned to H6a″ and H6b″ of the 5,6-ene moiety of the product. A COSY experiment showed the correlation of protons that were two and three bonds apart (Fig. 5A). Surprisingly connectivity between H4″ and H6″ was also observed in this experiment, even though a correlation between protons that are four bonds apart is typically not observed (34). Proton chemical shifts were assigned and verified by a TOCSY experiment (Fig. 5B). Protonated carbon chemical shifts, as well as multiplicities, were established by an HSQC experiment (Fig. 5C). The signal of C6″ gave reverse phase from C1″, C2″, C3″, and C4″. This suggests that protons at the 6″ position are methylene protons (-CH2-), whereas other protons in the sugar moiety are methine protons (-CH-). The chemical shift of nonprotonated carbon C5″ was assigned by an HMBC experiment (Fig. 5D), and the connectivities of C5″ to H1″, H4″, and H6″ were observed in the spectrum. These results, when taken together, provide evidence that Pen is a UDP-GlcNAc 4-oxidase/5,6-dehydratase/4-reductase that converts UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene.

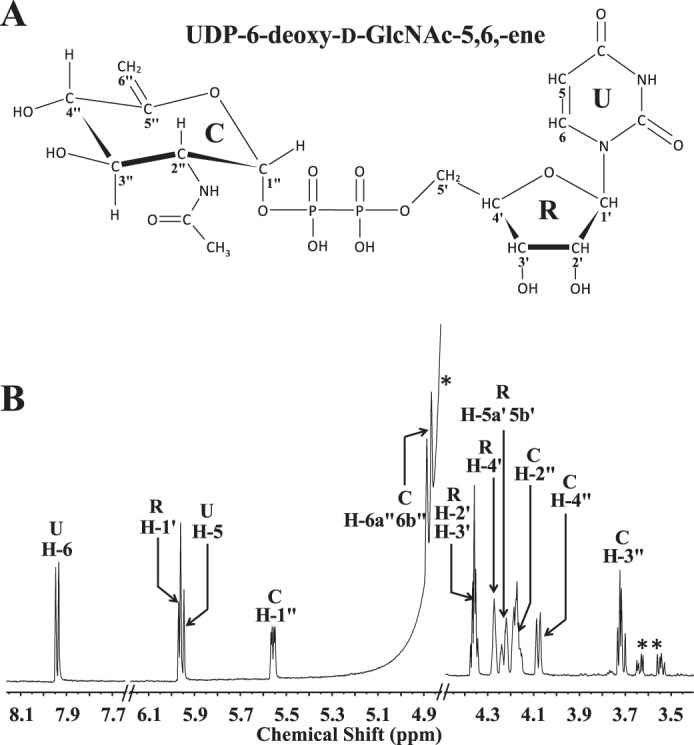

FIGURE 4.

One-dimensional proton NMR spectrum of Pen-enzymatic product UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene. This provides evidence that the dehydratase is a UDP-GlcNAc 4-oxidase/5,6-dehydratase/4-reductase. A, illustration of UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene. The protons (H) and carbons (C) are labeled with a number where the sugar pyranose ring is labeled as “C”; ribose is labeled as “R”; and uracil is labeled as “U.” B, 1H NMR spectrum of UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene (selective signals are labeled). Spectrum was cropped to fit the window. Contaminant signals are labeled for H2O signal (*) and glycerol (**).

FIGURE 5.

Two-dimensional NMR characterization of UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene derived by enzymatic reaction of Pen with UDP-GlcNAc. A, COSY experiment showing the connectivity between protons in the sugar ring moiety that are two to three bonds apart. Specifically note the connection between protons H4″ and H6″. B, TOCSY experiment showing the connectivity of H1″ and H6″ to all the other protons in the sugar ring. Note the connection of H6″ to all the other four protons: H1″, H2″, H3″, and H4″. C, HSQC experiment showing the 13C and 1H chemical shift of all protonated carbons in the sugar moiety. Note the phase (blue) of each CH group indicating 6″ belongs to CH2 group, although others (red) belong to CH group. D, HMBC experiment showing the connectivity of carbon to protons that are two to three bonds away, specifically the connection of C5″ to H1″, H4″, and H6″. Note the signal of C5″ was aliased so the actual chemical shift is 154.93 ppm.

Pal is a UDP-6-Deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene 4-Oxidase/5,6-Reductase/5-Epimerase That Converts UDP-6-Deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene to UDP-4-Keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc

We have provided evidence that Pen is a UDP-GlcNAc 4-oxidase/5,6-dehydratase/4-reductase. We now describe the function of Pal, the second enzyme encoded by the pse operon of B. thuringiensis. The UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene formed by recombinant Pen was purified by HPLC and used as a substrate for recombinant Pal. Two products (labeled K and H in Fig. 6A) eluted from the HILIC column as a broad UV261 peak between 15 and 17 min and a retention time of ∼16.5 min. A negative enzymatic reaction containing unrelated His6-tagged purified enzyme yielded no product. For initial characterization of the products (K and H), the broad peak was collected and analyzed by ESI-MS and MS/MS. Two ions at m/z 588.01 and 606.03 (Fig. 6B) were detected. Interestingly, the new UDP-sugar product (K) has a mass identical to UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene. Their different elution times (16.5 versus 15.5 min, respectively) suggest that the product and substrate are chemically different. MS/MS analysis of each parent ion gave two ion fragments having m/z 323 and 403 values that are consistent with UMP and UDP, respectively. This indicated that the products were UDP-sugars.

FIGURE 6.

Analyses of UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc, the enzymatic product of Pal by UV-HPLC, mass spectrometry, and time-resolved 1H NMR. A, purified Pal was reacted with UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene (“C,” the purified enzymatic product of Pen) to yield at least two new UV-broad HPLC peaks labeled “K,” “H,” and marked by arrows. The top HPLC trace in A corresponds to purified product C standard, and the bottom trace is the negative control. an assay of purified irrelevant protein with C. The K and H peaks (eluted from HILIC column at 16 min) were collected and characterized by NMR (see Table 2). B, MS analysis in negative mode gives two [M − H]− ions at m/z 588.1 and 606.0 corresponding to two forms of UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc, 4-keto and its hydrated forms, respectively. C, time-resolved 1H NMR showing Pal enzymatic conversion of UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene (C) to UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. As the reaction proceeds, two molecular species are produced, a 4-keto form and a 4-keto-hydrated form of UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. The selected chemical shift region of the proton NMR spectrum that corresponds to the H-1″ anomeric proton of enzymatic reactant and product is shown between 5.80 and 5.40 ppm. Note the H-4″ peak of the substrate (“C”) shown at 4.09 ppm is converted to new product K and H (the 4-keto and its hydrated form). The far right panel (between 1.60 and 1.30 ppm) shows the methyl groups (H-6″) belonging to the hydrated (H) and the keto (K) forms of the product UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc.

To gain further insight into Pal-enzyme activity, we monitored the reaction by time-resolved 1H NMR (Fig. 6C). Two products with a quartet of signals at 5.74 and 5.555 ppm in the anomeric region of the NMR spectrum appeared over the reaction time. The anomeric signal at 5.555 ppm (see 60-min time point) was clear but overlapped at early reaction time points (5–30 min) with the anomeric signal of the substrate, UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene (labeled C, H-1″), at 5.56 ppm. The H-4″ proton signal of the substrate (labeled C, H-4″) decreased over time while the amounts of product depicted by other proton signals (labeled H and K) increased. Two signals appeared at the 6-deoxy region around 1.55 and 1.37 ppm. These signals correspond to C6-methyl protons (H-6″) of product K (UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc) and H (hydrated form of K) sugar moiety, respectively. Proton and carbon chemical shifts and proton coupling constants of H are listed in Table 2.

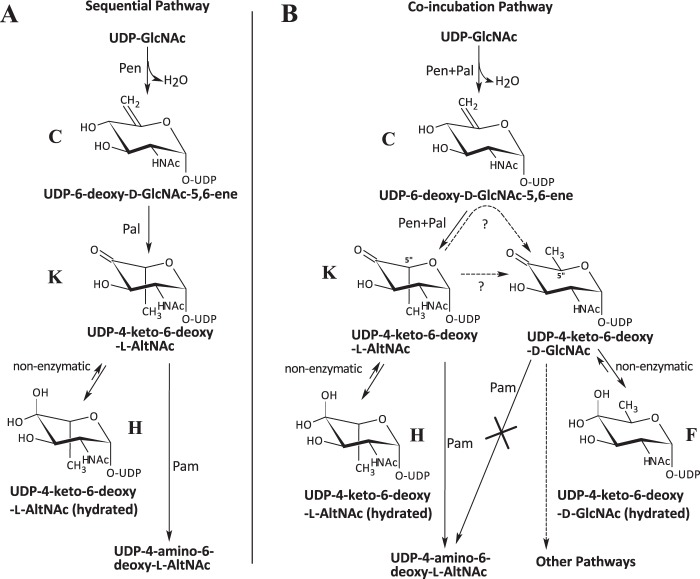

Pen and Pal Together Produce UDP-4-Keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc and UDP-4-Keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc

Another interesting aspect of these two Bacillus enzymes was the formation of an additional product when the enzymes were incubated together rather than in a sequential manner (see illustration in Fig. 8). When Pen and Pal were combined and incubated with UDP-GlcNAc, an additional product was formed besides K and H. We used 1H NMR spectroscopy to monitor the reaction of recombinant enzymes with the substrate, UDP-GlcNAc, over 8 h to determine the nature of this new product (Fig. 7A, labeled F). Two signals at 5.74 and 5.555 ppm corresponding to the anomeric protons of K and H appeared within 1 h and started to disappear after 3 h. Similarly, two signals at 1.55 and 1.37 ppm corresponding to the 6-deoxy protons of K and H also disappeared after 3 h. A new signal at 5.47 ppm developed gradually over the 8-h period as did a signal at 1.24 ppm. We have assigned these signals to the anomeric proton and H6″ of the sugar moiety of UDP-2-acetamido-2,6-dideoxy-α-d-xylo-hex-4-ulose (UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc, product F), which is the 5-epimer of UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc was formed only when both Pen and Pal were added to the reaction; it was not detected when the two enzymes were added sequentially (Fig. 7B). To verify that UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc was produced enzymatically, we reacted UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene with Pal for 8 h. No UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc was formed. Thus, UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc is likely formed by an enzymatic reaction. The chemical shift (Table 2) suggests that product F is the 4-keto-hydrated form of UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc. A biosynthetic pathway for the Pen and Pal reactions is proposed (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Two proposed biosynthesis pathways involving Pen and Pal. In a sequential reaction pathway, Pen was incubated with UDP-GlcNAc, and Pal was then added. In the co-incubation pathway, both enzymes Pen and Pal were incubated together with UDP-GlcNAc. In the sequential reaction, UDP-GlcNAc was converted to UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene (labeled as “C”) by Pen, followed by Pal converting C to keto and hydrated forms of l-configured UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc (labeled as “K” and “H”). Note that products K and H were able to undergo C4″ transamination reaction by Pam leading to product A, UDP-4-amino-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. In the co-incubation pathway, UDP-GlcNAc was converted to a mixture of four products, including C, K, H, and a novel product F, a d-configured UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc. After a long period of incubation, the product would be predominantly F, as the other products, including C, K, and H, would be consumed. Note that product F, UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc, was not a substrate for Pam; hence Pam was unable to C4″ transaminate this d-configured UDP-sugar.

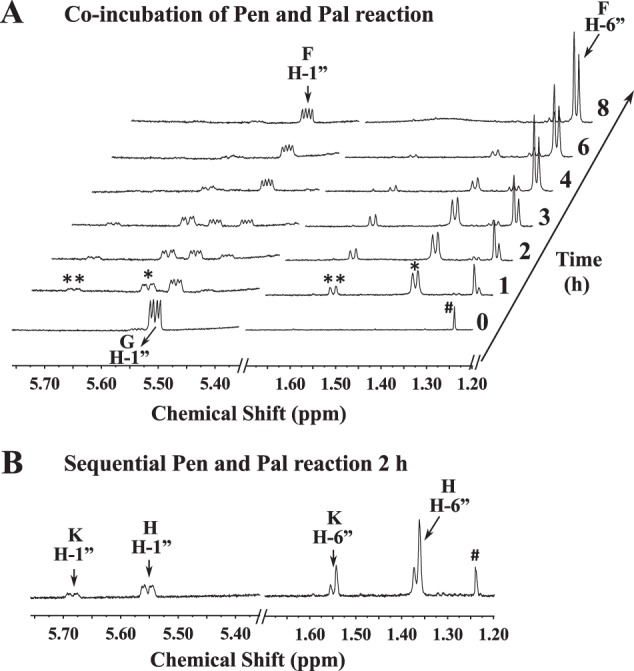

FIGURE 7.

Co-incubation of Pen and Pal with the UDP-GlcNAc (G) yields four molecular species as determined by time-resolved 1H NMR. A, when co-incubation reaction was carried out up to 8 h, in addition to the keto and hydrated forms of UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc, another predominant hydrated form of UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc was observed. The selected chemical shift region for the anomeric protons of reactant and product is shown between 5.75 and 5.35 ppm, and the diagnostic H-6″ peak of the dual enzyme final products “F” is shown between 1.70 and 1.20 ppm. The peaks annotated * belong to a signal of Pal's hydrated product (“H”) as an intermediate, and the peaks annotated ** belong to signal peaks of Pal's keto product (“K”). B, 2-h reaction of the single enzyme Pal incubated with UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene, showing only UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc was produced but no UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc. The peak labeled with # belongs to a contaminant.

UDP-4-Keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc Is a Substrate for the Pse Metabolic Enzyme UDP-4-Keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc Is not a Substrate

The sequential activity of Pen and Pal results in the formation of UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc, which is a substrate for the next enzyme Pam in the Glu:C4″-aminotransferase reaction. However, the UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc formed when the two enzymes are combined is not a substrate for the transaminase. Thus, the 4-aminotransferase (Pam) is specific for the 5-epimer-4-keto-sugar, UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc.

Enzymatic Properties of Pen and Pal

The pH- and temperature-dependent activity of Pen and Pal and kinetic data for these enzymes are summarized in Table 3. Pen has its highest activity in phosphate buffer at pH 7.64; however, high activity was also observed in MOPS-NaOH, pH 7.6, Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and with the slight acidic condition in MES buffer at pH 6.85. The optimal temperature for Pen activity was at 37 °C; however, the activities of Pen ranging from 30 to 50 °C were similar and varied by no more than 10%. As for Pal, we were unable to separate the products from the substrates through the HILIC column. Consequently, we only measured the optimal pH and temperature for Pal by comparing the peak reduction of the substrates.

TABLE 3.

Pen and Pal enzyme properties

ND means not determined.

| Pen | Pal | pseB (C. jejuni)a | pseB (H. pylori)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal pHc | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Optimal temperature (°C)d | 37 | 30 | 42 | 37 |

| Km (mm)e | 0.143 ± 0.006 | ND | 0.050 | 0.159 |

| Vmax (nm s−1) | 15.01 ± 0.29 | ND | ||

| kcat (min−1) | 30.02 ± 0.58 | ND | 1.51 | 5.7 |

| kcat/Km (mm−1 min−1) | 209.9 ± 12.9 | ND | 30.6 | 35.9 |

| Protein monomer (kDa)f | 40 | 37.1 | 37.4 | 37.4 |

a Kinetic data of pseB in C. jejuni was from Ref. 35.

b Kinetic data of pseB in H. pylori was from Ref. 36.

c For Pen, optimal pH assays were determined using phosphate buffer in which Pen yielded the highest activity compared with MOPS-NaOH, Tris-HCl, and MES buffer. For Pal, optimal pH assays were determined using Tris-HCl buffer.

d Optimal temperature assays were determined using Tris-HCl for both Pen and Pal.

e The reaction was determined by HPLC-UV after a 5-min 30 °C incubation for Pen.

f The active forms of proteins eluted from the size-exclusion column were 192.8 kDa for Pen and 87.6 kDa for Pal, presumably suspected to be a tetramer and a dimer, respectively.

Comparative analyses of the kinetics between PseB from C. jejuni and H. pylori (35, 36) with Pen from B. thuringiensis showed that Pen Km for UDP-GlcNAc has a similar affinity for the substrate (Table 3). However, Pen turnover (kcat/Km) was 209, which is much higher than PseB, suggesting that the B. thuringiensis Pen converts UDP-GlcNAc into a product more efficiently.

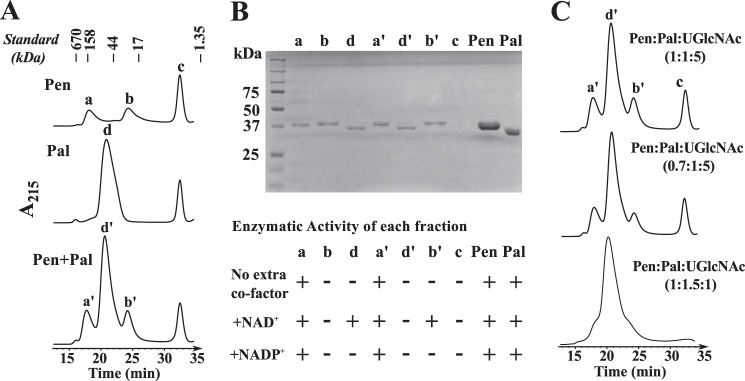

To determine whether the 4-oxidase activities of Pen and Pal require NAD+ or NADP+, and to address whether Pen enzyme functions as a dimer or forms a functional complex with Pal, we performed a series of experiments (Fig. 9) using size-exclusion chromatography on Superdex-75. The proteins were preincubated with and without substrate (UDP-GlcNAc). The proteins were either loaded on the column individually or were loaded in a mix together. Protein peaks were then collected and tested for activity and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Pen eluted from the column in two peaks (peak a and b, Fig. 9A). One peak migrated as a protein of 31.9 kDa (presumably a monomer), and the second peak eluted in the region for a protein with a mass of about 192.8 kDa. The earlier peak (presumably a pentamer, tetramer, or dimer of dimers) but not the latter peak had enzymatic activity when supplied with UDP-GlcNAc (Fig. 9B). Conversely, Pal eluted from the column as a single peak (peak d, Fig. 9A), migrating 87.6 kDa presumably as a dimer. This peak was only enzymatically active when supplemented with NAD+ (Fig. 9B). No Pal activity was obtained by adding NADP+. Taken together, we propose that Pal activity involves the co-factor NAD+ for oxidation/reduction cycle of the enzyme product. The nature of the oligomeric state of Pen and Pal, however, is speculative, and the chromatographic mobility could be influenced by the shape of the protein.

FIGURE 9.

Nature of the oligomeric state of Pen and Pal as estimated by size exclusion chromatography. A, individual proteins (Pen or Pal) or combined proteins (Pen plus Pal) were incubated with UDP-GlcNAc on ice prior to chromatography on Superdex-75 column. The UV215 chromatogram trace in the top panel is showing that Pen migrates on Superdex-75 in two molecular species, peaks a and b. Only the peak a is enzymatically active. Peak c is UDP-GlcNAc. The middle panel is showing that Pal migrated as single peak d. The bottom panel shows no apparent interaction between Pen and Pal during co-incubation with UDP-GlcNAc. The migration of standard molecular weight proteins on the Superdex-75 column is indicated on top. B, each eluted protein fraction (a, b, and d and a′, b′, and d′) and peak c was visualized by SDS-PAGE. The last two lanes labeled as “Pen″ and “Pal″ are controls, i.e. purified proteins before size-exclusion chromatography. The detailed enzymatic activity of each eluted protein shown below the SDS-polyacrylamide gel was tested in the presence of NAD+ and/or NADP+. The “+” sign indicates activity. It is not suggesting enhanced activity. C, different ratios of Pen and Pal enzymes and substrate UDP-GlcNAc were mixed prior to chromatography on Superdex-75 column. No obvious Pen-Pal complex was formed.

We tested whether Pen and Pal interacted with each other; however, gel filtration assays showed when both enzymes were mixed together and chromatographed (Fig. 9A, bottom panel), each enzyme had the same elution pattern as the individual protein. Each peak was collected from the column and resolved on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 9B). A single peptide band was observed, (compare lanes a, b, and d with a′, b′, and d′). No difference in elution profiles was obtained by adding UDP-GlcNAc or with UDP-GlcNAc + NAD+ to the combined enzymes. In addition, when different ratios of Pen, Pal, and UDP-GlcNAc were chromatographed (Fig. 9C), the peak signal increased proportionally. Taking together, the results suggest that Pen and Pal do not form a complex under this experimental setup.

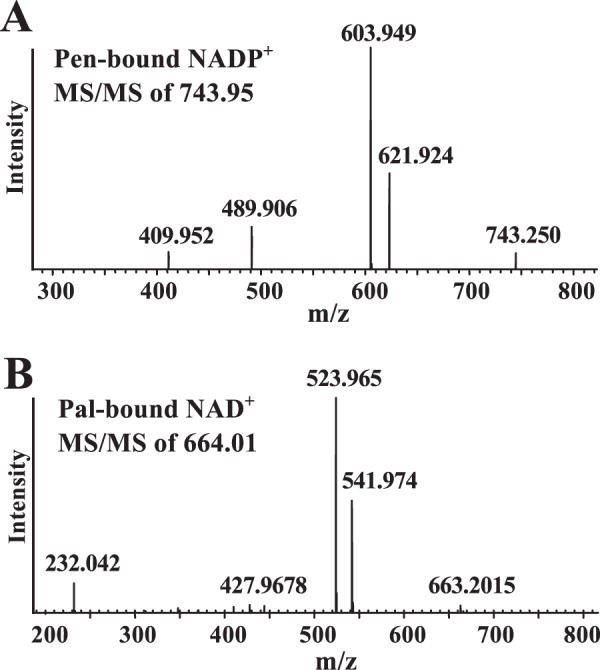

No data indicating that Pen requires a cofactor for activity was obtained by size-exclusion chromatography (Fig. 9B). Nevertheless, we suspected that this protein binds NAD+ or NADP+ so tightly that it would only be released when denatured. Therefore, we heat-inactivated purified Pen as well as Pal and examined the products released by LC-ESI-MS/MS. NADP+ with [M + H]+ ion m/z at 743.9, and diagnostic MS/MS ion fragments (603.9, 621.9, 489.9, and 409.9) were detected when Pen was denatured (Fig. 10A), whereas NAD+ with m/z at 664.0 (MS/MS 523.9, 541.9, 232.0, and 427.9) was detected when Pal was denatured (Fig. 10B). The inability of the size-exclusion column to separate bound-NADP+ from Pen suggests a strong interaction between the protein and its co-factor. By comparison with Pal, it is likely that within the Pen protein more amino acid residues are involved in the hydrogen bond connection between the co-factor and the enzyme. Together, these experiments provide evidence that NAD+ is a co-factor required for the oxidase/reductase activity of the Pal enzyme.

FIGURE 10.

Pen has an NAD+-bound co-factor, and Pal is bound to NADP+ as determined after heat inactivation and mass spectrometry analyses. An aliquot of purified Pen or purified Pal was heat-treated, centrifuged, and concentrated and a portion was chromatographed through a HILIC column using LC-ESI-MS/MS. A major positive ion at m/z 743.9 was eluted from a HILIC column at 10.4 min for the denatured Pen sample. This m/z value corresponding to parent ion NADP+ and the diagnostic MS/MS ion fragment's of NADP+ is shown in A. A major positive ion at m/z 664.01 was eluted from a HILIC column at 8.4 min for the denatured Pal sample. The latter m/z values corresponding to NAD+ and the MS/MS fragmentation is shown in B. Standard NAD+ and NADP+ were separately chromatographed and analyzed by LC-ESI-MS/MS.

DISCUSSION

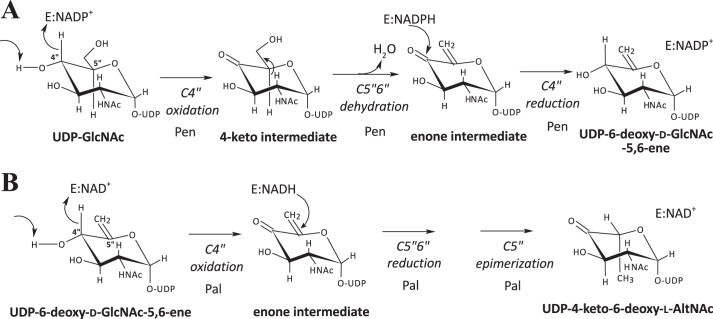

We have identified an operon in B. thuringiensis israelensis ATCC 35646 (Fig. 1, A and B) containing seven genes that encode enzymes involved in the conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to CMP-Pse. The product of each enzymatic reaction, UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene, UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc, UDP-4-amino-4,6-dideoxy-N-acetyl-β-l-altrosamine (UDP-4-amino-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc), UDP-2,4-diacetamido-2,4,6-trideoxy-β-l-altropyranose (UDP-2,4,6-trideoxy-2,4-diNAc-l-altrose), 2,4-diacetamido-2,4,6-trideoxy-β-l-altropyranose (2,4,6-trideoxy-2,4-diNAc-l-altrose), Pse, and CMP-Pse were characterized by LC-MS/MS and NMR spectroscopy. B. thuringiensis is unusual as it uses two dehydratase-like enzymes to initiate the conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. The known functional PseB from the Gram-negative bacteria uses only one enzyme to catalyze this reaction (27, 37).

H. pylori and C. jejuni both have a single bi-functional 5-epimerase/4,6-dehydratase (PseB) that converts UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. C. jejuni PseB complexed with NADP+ has been proposed to mediate the C4″ oxidation of UDP-GlcNAc, which is followed by a series of enzyme-bound intermediates that include 4-keto, dehydration, NADPH-mediated reduction of the ene group, and a C5″-epimerization to yield UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc (37). The two separate B. thuringiensis dehydratase-like activities produce the same end product as PseB (Fig. 1A), but carry out this reaction differently. We propose that Pen oxidizes C4″ of UDP-GlcNAc via E:NADP+ to form the C4″-keto intermediate (Fig. 11A). The same enzyme then carries out a 5,6-dehydratase reaction to form the 5,6-ene moiety. E:NADPH then performs a stereospecific C4″-keto reduction to give UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene. What elicits the Pen E:NADPH-mediated C4″ reduction rather than the C5″-C6″ reduction as is the case in the “classical 4,6-dehydratase activity” is not known. Amino acid sequence comparison shows that, interestingly, Pen has “11 extra” amino acids (aa 242–252) when compared with PseB. We postulate that the extra sequence forms a secondary structure that exists to either push away the 5,6-ene moiety or transiently bind the 5,6-ene moiety to protect it from the NADPH reduction step. Another possibility is that the extra 11-amino acid-long peptide structure of Pen may exist to facilitate a C4″-specific reduction and maintain the same gluco-sugar ring configuration. Taken together, we propose that Pen is a UDP-GlcNAc 4-oxidase/5,6-dehydratase/4-reductase.

FIGURE 11.

Proposed enzyme reaction intermediates involved in the conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene and the proposed intermediates in the conversion to UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. A, Pen is predicted to first carry out a NADP+-dependent C4″-oxidation to form a 4-keto-intermediate. Subsequently, dehydration at C5″-C6″ forms an enone intermediate (5,6-ene moiety). This is followed by NADPH-mediated specific reduction at C4″ to form a product of the same gluco-configuration and the release of a product with a double bond along C5″=C6″, UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene. Hence, we abbreviated the Pen activities as UDP-GlcNAc 4-oxidase/5,6-dehydratase/4-reductase. B, Pal is predicted to first carry out a NAD+-dependent C4″-oxidation forming an UDP-4-keto-intermediate. Subsequently, we assume that C5″=C6″ undergoes reduction followed by C5″ epimerization leading to the production of UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. In solution, the product UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc is found predominantly in its hydrated form. We abbreviated the Pal-activities as UDP-GlcNAc 4-oxidase/5,6-reductase/5-epimerase.

We postulate that Pal catalyzes a NAD+-mediated C4″-oxidation to generate a UDP-4-keto-GlcNAc-5,6-ene intermediate (Fig. 11B). Following this reaction, the hydride from E:NADH is transferred to the C5″-C6″-ene moiety via the opposite face of the double bond leading to C5″ reduction and C5″ epimerization to give UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. Hence, Pal is a UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene 4-oxidase/5,6-reductase/5-epimerase. Interestingly, a long co-incubation of Pen and Pal leads to the production of UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc (Figs. 7 and 8). Thus, it is possible that Pal could mediate 5″-epimerization between UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc and UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc.

Pal shares low amino acid sequence identity to the dTDP-Glc 4,6-dehydratase from B. anthracis strain Ames. However, Pal is not acting on various NDP-sugars that were tested, including UDP-GlcNAc, UDP-GalNAc, and UDP-Glc. Pal shares even lower amino acid sequence identity to PseB and is unable to act on UDP-GlcNAc. Insight into the amino acid residues involved in the catalytic activities of Pen and Pal will require the use of site-directed mutagenesis in combination with a description of the three-dimensional structures of the enzymes.

In B. thuringiensis, two enzymes are required to generate the UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. This reaction also generates UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene. It is not known whether the UDP-GlcNAc derivative participates in other metabolic pathways. Interestingly, UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene is an intermediate formed by TunA during the synthesis of tunicamycin by Streptomyces species (38). Whether or not the pathway of an analogue exists in B. thuringiensis remains unknown. Although the TunA enzyme structure was solved (38), very low amino acid sequence similarity (24% and e-value 0.004) exists between the Pen and the TunA protein, suggesting these genes are evolutionarily not related and perhaps arose from different ancestral genes. With regard to Pal, we are currently unaware of another single activity identical to this enzyme.

Our kinetics data (kcat/Km) for Pen suggest that it converts UDP-GlcNAc into product more efficiently (Table 3) compared with TunA and PseB (27, 38). However, the product itself inhibited the Pen forward reaction. This resulted in a maximum ∼10% conversion of substrate to product. Pal, however, rapidly converts the 5,6-ene to the 4-keto derivative and thereby facilitates almost full conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc. The formation of UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc when Pen and Pal were combined together and reacted with UDP-GlcNAc suggests that Pal can be a stand-alone C5″-epimerase, albeit of low efficiency. Incubating C. jejuni PseB with UDP-GlcNAc for periods up to 15 h also resulted in the C5″ epimerization UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc to UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc (37); the exact mechanism to explain this remains unknown.

Our characterization of the first two enzymes (Pen and Pal) in the Bti-pse operon provides insight into the metabolic pathway leading to the formation of Pse in B. thuringiensis. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the products formed by these enzymes also participate in other metabolic pathways. Additional studies are now required to determine whether other members of the Bacillaceae also have these enzymes. Understanding the molecular factors that control the flux of UDP-GlcNAc to different metabolic pathways in bacteria is important, as this nucleotide-sugar is a precursor used for the formation of wall polysaccharides and peptidoglycan as well as other glycans.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Malcolm O'Neill of the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center for constructive comments on the manuscript and Dr. John Glushka for help with NMR spectroscopy.

This work was supported by BioEnergy Science Center Grant DE-PS02-06ER64304, which is supported by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research in the Department of Energy Office of Science.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) KM433664 and KM433665.

A glycoprotein screen in our laboratory (Z. Li and M. Bar-Peled, unpublished data) in B. thuringiensis israelensis has identified flagellin to be modified by sugar residue (with a mass of m/z 317.1).

Preliminary data of Bc3750-encoded recombinant enzyme activity in our laboratory (S. Hwang and M. Bar-Peled, unpublished data) showed that enzymatic product was not UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc.

- Pse

- pseudaminic acid

- CMP-Pse

- CMP-pseudaminic acid

- PEP

- phosphoenolpyruvate

- ESI-MS

- electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry

- COSY

- correlation spectroscopy

- TOCSY

- total correlation spectroscopy

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- HMBC

- heteronuclear multiple bond correlation

- DSS

- 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate

- UDP-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc-5,6-ene

- UDP-2-acetamido-6-deoxy-α-d-xylo-hexopyranose-5,6-ene

- UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-l-AltNAc

- UDP-2-acetamido-2,6-dideoxy-β-l-arabino-hex-4-ulose

- UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-d-GlcNAc

- UDP-2-acetamido-2,6-dideoxy-α-d-xylo-hex-4-ulose

- HILIC

- hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography.

REFERENCES

- 1. Assaeedi A. S., Osman G. E., Abulreesh H. H. (2011) The occurrence and insecticidal activity of Bacillus thuringiensis in the arid environments. Aust. J. Crop. Sci. 5, 1185–1190 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sanahuja G., Banakar R., Twyman R. M., Capell T., Christou P. (2011) Bacillus thuringiensis: a century of research, development and commercial applications. Plant Biotechnol. J. 9, 283–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ichimatsu T., Mizuki E., Nishimura K., Akao T., Saitoh H., Higuchi K., Ohba M. (2000) Occurrence of Bacillus thuringiensis in fresh waters of Japan. Curr. Microbiol. 40, 217–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aly C., Mulla M. S., Federici B. A. (1985) Sporulation and toxin production by Bacillus thuringiensis var Israelensis in cadavers of mosquito larvae (Diptera, Culicidae). J. Invertebrate Pathol. 46, 251–258 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mizuki E., Ichimatsu T., Hwang S. H., Park Y. S., Saitoh H., Higuchi K., Ohba M. (1999) Ubiquity of Bacillus thuringiensis on phylloplanes of arboreous and herbaceous plants in Japan. J. Appl. Microbiol. 86, 979–984 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jensen G. B., Hansen B. M., Eilenberg J., Mahillon J. (2003) The hidden lifestyles of Bacillus cereus and relatives. Environ. Microbiol. 5, 631–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gillis A., Dupres V., Delestrait G., Mahillon J., Dufrêne Y. F. (2012) Nanoscale imaging of Bacillus thuringiensis flagella using atomic force microscopy. Nanoscale 4, 1585–1591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schnepf E., Crickmore N., Van Rie J., Lereclus D., Baum J., Feitelson J., Zeigler D. R., Dean D. H. (1998) Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 775–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schünemann R., Knaak N., Fiuza L. M. (2014) Mode of action and specificity of Bacillus thuringiensis toxins in the control of caterpillars and stink bugs in soybean culture. ISRN Microbiol. 2014, 135675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ibrahim M. A., Griko N. B., Bulla L. A., Jr. (2013) The Cry4B toxin of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis kills permethrin-resistant Anopheles gambiae, the principal vector of malaria. Exp. Biol. Med. 238, 350–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Broderick N. A., Raffa K. F., Handelsman J. (2006) Midgut bacteria required for Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 15196–15199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Swiecicka I., Mahillon J. (2006) Diversity of commensal Bacillus cereus sensu lato isolated from the common sow bug (Porcellio scaber, Isopoda). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 56, 132–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Margulis L., Jorgensen J. Z., Dolan S., Kolchinsky R., Rainey F. A., Lo S. C. (1998) The Arthromitus stage of Bacillus cereus: intestinal symbionts of animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 1236–1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lövgren A., Zhang M. Y., Engström A., Landén R. (1993) Identification of two expressed flagellin genes in the insect pathogen Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. alesti. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139, 21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shen A., Higgins D. E. (2006) The MogR transcriptional repressor regulates nonhierarchal expression of flagellar motility genes and virulence in Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS Pathog. 2, e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Soufiane B., Xu D., Côté J. C. (2007) Flagellin (fliC) protein sequence diversity among Bacillus thuringiensis does not correlate with H serotype diversity. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 92, 449–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maki-Yonekura S., Yonekura K., Namba K. (2003) Domain movements of HAP2 in the cap-filament complex formation and growth process of the bacterial flagellum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 15528–15533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Namba K., Yamashita I., Vonderviszt F. (1989) Structure of the core and central channel of bacterial flagella. Nature 342, 648–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kotiranta A., Lounatmaa K., Haapasalo M. (2000) Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Bacillus cereus infections. Microbes Infect. 2, 189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hayakawa J., Kondoh Y., Ishizuka M. (2009) Cloning and characterization of flagellin genes and identification of flagellin glycosylation from thermophilic Bacillus species. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 73, 1450–1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Young G. M., Schmiel D. H., Miller V. L. (1999) A new pathway for the secretion of virulence factors by bacteria: the flagellar export apparatus functions as a protein-secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 6456–6461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ottemann K. M., Miller J. F. (1997) Roles for motility in bacterial-host interactions. Mol. Microbiol. 24, 1109–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schirm M., Schoenhofen I. C., Logan S. M., Waldron K. C., Thibault P. (2005) Identification of unusual bacterial glycosylation by tandem mass spectrometry analyses of intact proteins. Anal. Chem. 77, 7774–7782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thibault P., Logan S. M., Kelly J. F., Brisson J. R., Ewing C. P., Trust T. J., Guerry P. (2001) Identification of the carbohydrate moieties and glycosylation motifs in Campylobacter jejuni flagellin. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 34862–34870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schirm M., Arora S. K., Verma A., Vinogradov E., Thibault P., Ramphal R., Logan S. M. (2004) Structural and genetic characterization of glycosylation of type a flagellin in Pseudomonas aemginosa. J. Bacteriol. 186, 2523–2531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Parker J. L., Day-Williams M. J., Tomas J. M., Stafford G. P., Shaw J. G. (2012) Identification of a putative glycosyltransferase responsible for the transfer of pseudaminic acid onto the polar flagellin of Aeromonas caviae Sch3N. Microbiology Open 1, 149–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schoenhofen I. C., McNally D. J., Brisson J. R., Logan S. M. (2006) Elucidation of the CMP-pseudaminic acid pathway in Helicobacter pylori: synthesis from UDP-N-acetylglucosamine by a single enzymatic reaction. Glycobiology 16, 8C–14C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guerry P., Ewing C. P., Schirm M., Lorenzo M., Kelly J., Pattarini D., Majam G., Thibault P., Logan S. (2006) Changes in flagellin glycosylation affect Campylobacter autoagglutination and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 60, 299–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schirm M., Soo E. C., Aubry A. J., Austin J., Thibault P., Logan S. M. (2003) Structural, genetic and functional characterization of the flagellin glycosylation process in Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 1579–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yang T., Bar-Peled L., Gebhart L., Lee S. G., Bar-Peled M. (2009) Identification of galacturonic acid-1-phosphate kinase, a new member of the GHMP kinase superfamily in plants, and comparison with galactose-1-phosphate kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 21526–21535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gu X., Glushka J., Yin Y., Xu Y., Denny T., Smith J., Jiang Y., Bar-Peled M. (2010) Identification of a bifunctional UDP-4-keto-pentose/UDP-xylose synthase in the plant pathogenic bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum strain GMI1000, a distinct member of the 4,6-dehydratase and decarboxylase family. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9030–9040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gill S. C., von Hippel P. H. (1989) Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino-acid sequence data. Anal. Biochem. 182, 319–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gu X., Glushka J., Lee S. G., Bar-Peled M. (2010) Biosynthesis of a new UDP-sugar, UDP-2-acetamido-2-deoxyxylose, in the human pathogen Bacillus cereus subspecies cytotoxis NVH 391–98. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24825–24833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gunther H., Jikeli G. (1977) H-1 Nuclear magnetic-resonance spectra of cyclic monoenes- hydrocarbons, ketones, heterocycles, and benzo derivatives. Chem. Rev. 77, 599–637 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Creuzenet C. (2004) Characterization of CJ1293, a new UDP-GlcNAc C6 dehydratase from Campylobacter jejuni. FEBS Lett. 559, 136–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Creuzenet C., Schur M. J., Li J., Wakarchuk W. W., Lam J. S. (2000) FlaA1, a new bifunctional UDP-GlcNAc C6 dehydratase/ C4 reductase from Helicobacter pylori. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 34873–34880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Morrison J. P., Schoenhofen I. C., Tanner M. E. (2008) Mechanistic studies on PseB of pseudaminic acid biosynthesis: a UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 5-inverting 4,6-dehydratase. Bioorg. Chem. 36, 312–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wyszynski F. J., Lee S. S., Yabe T., Wang H., Gomez-Escribano J. P., Bibb M. J., Lee S. J., Davies G. J., Davis B. G. (2012) Biosynthesis of the tunicamycin antibiotics proceeds via unique exo-glycal intermediates. Nat. Chem. 4, 539–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]