Background: Currently, it is not clear how osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells (FBGCs) are differentially regulated.

Results: Inflammatory cytokines and infection mimetics activated osteoclastogenesis and inhibited FBGC formation, as indicated by M1/M2 macrophage polarization, in an IRAK4-dependent manner.

Conclusion: Osteoclasts and FBGCs are reciprocally regulated by IRAK4.

Significance: This study provides a basis for understanding regulation of foreign body reactions via IRAK4.

Keywords: Bone, Cell Biology, Differentiation, Gene Expression, Osteoclast

Abstract

Formation of foreign body giant cells (FBGCs) occurs following implantation of medical devices such as artificial joints and is implicated in implant failure associated with inflammation or microbial infection. Two major macrophage subpopulations, M1 and M2, play different roles in inflammation and wound healing, respectively. Therefore, M1/M2 polarization is crucial for the development of various inflammation-related diseases. Here, we show that FBGCs do not resorb bone but rather express M2 macrophage-like wound healing and inflammation-terminating molecules in vitro. We also found that FBGC formation was significantly inhibited by inflammatory cytokines or infection mimetics in vitro. Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-4 (IRAK4) deficiency did not alter osteoclast formation in vitro, and IRAK4-deficient mice showed normal bone mineral density in vivo. However, IRAK4-deficient mice were protected from excessive osteoclastogenesis induced by IL-1β in vitro or by LPS, an infection mimetic of Gram-negative bacteria, in vivo. Furthermore, IRAK4 deficiency restored FBGC formation and expression of M2 macrophage markers inhibited by inflammatory cytokines in vitro or by LPS in vivo. Our results demonstrate that osteoclasts and FBGCs are reciprocally regulated and identify IRAK4 as a potential therapeutic target to inhibit stimulated osteoclastogenesis and rescue inhibited FBGC formation under inflammatory and infectious conditions without altering physiological bone resorption.

Introduction

Biomaterial implants, including pacemakers, artificial joints, prostheses, dental implants, and bone devices, are now necessities of human life. Indeed, it is estimated that 20–25 million people in the United States have some type of implanted medical device (1). Inflammation and infection are primary factors underlying implant failure (2, 3), often with disastrous consequences for device function and the patient. Thus preventing these failures is crucial for patients' well being.

A foreign body response (FBR)3 characterized by foreign body giant cell (FBGC) formation occasionally occurs following implantation of foreign materials (4). FBGC formation emerging from implanted biomaterials is reportedly associated with biomaterial degradation and failure (5–7); thus, controlling FBGC formation is considered critical to prevent implant failure. Nonetheless, we have little understanding of mechanisms underlying the FBR or how FBGC differentiation is regulated.

FBGCs are formed by cell-cell fusion of mononuclear cells (8–10). Various molecules, such as dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP), ATPv0d2, MFR, CD47, CD44, DAP12, and OC-STAMP reportedly function in macrophage fusion (9, 11–17). Osteoclasts are also multinuclear giant cells derived from monocyte/macrophage lineage cells, and their multinucleation is also induced by fusion of mononuclear osteoclasts. Although both FBGC and osteoclast formation are induced by fusion of mononuclear cells in a DC-STAMP-dependent manner, regulation of FBGC and osteoclast differentiation likely differs. Indeed, we have previously reported that transcription of DC-STAMP is regulated differently in osteoclasts than it is in FBGCs (10). Therefore, we hypothesize that FBGCs play a role in FBR different from osteoclasts.

Osteoclasts play a critical role in bone resorption, destruction, and osteolysis. In addition, inhibition of osteoclast differentiation and function is considered crucial to prevent bone loss and osteolysis-induced implant failure (18, 19). However, strong osteoclast inhibition beyond levels required for physiological bone metabolism frequently causes adverse effects such as osteopetrosis, osteonecrosis, or severely suppressed bone turnover (20–23). Thus, specific inhibitors of pathologically activated osteoclast levels resulting from inflammation or infection have been sought.

Macrophages consist of two major subpopulations, M1 and M2 (24, 25). M1 macrophages are activated by various stimuli, including bacterial or viral infections, and express inflammatory cytokines. In contrast, M2 macrophages function in parasitic infections, allergic responses, or wound healing (26). Thus, M1/M2 polarization status is considered crucial for the development of various diseases (27).

Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-4 (IRAK4) is a member of the interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase family of proteins composed of IRAK1–4. Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases transduce inflammatory cytokine and toll-like receptor signals and reportedly function in the activation of natural killer cells, antigen-presenting cells, and T cells (28–31). IRAK4 is reported to play a role in regulating both IL-1 and toll-like receptor signaling (28).

Here, we report two critical findings that strongly suggest that implant failure due to bone loss likely results from activity of osteoclasts rather than FBGCs. First, we show that FBGCs, unlike osteoclasts, cannot resorb bone but rather express wound-healing and inflammation-terminating molecules, such as Ym1 and Alox15. Second, promotion of bone loss and inhibition of FBGC formation by LPS seen in wild-type mice were both completely abrogated in mice deficient in IRAK4. Furthermore, loss of IRAK4 in vitro and in vivo did not inhibit physiological osteoclastogenesis, and IRAK4-deficient mice exhibited normal bone mass. Overall, our findings show that FBGC and osteoclast differentiation are reciprocally regulated by IRAK4 and suggest that targeting IRAK4 could antagonize implant failure by promoting FBGC formation and blocking osteoclastogenesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

IRAK4-deficient mice were provided by the Department of Medical Biophysics, Ontario Cancer Institute. Wild-type mice on a C57BL/6 background were purchased from Sankyo Lab (Tsuchiura, Japan). Animals were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in animal facilities certified by the animal care committee at the Keio University School of Medicine. Animal protocols were approved by the animal care committee at the Keio University School of Medicine.

Reagents

Macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), GM-CSF, IL-4, and IL-1β were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Recombinant soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor κ-B ligand (RANKL) was purchased from PeproTech Ltd. (Rocky Hill, NJ). LPS and zymosan were purchased from Sigma.

In Vitro Osteoclastogenesis Assay

Bone marrow cells were isolated from wild-type or IRAK4-deficient mice and cultured in α-modified Eagle's minimum essential medium (Sigma) containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS (JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS) and GlutaMAX (Invitrogen) supplemented with 50 ng/ml M-CSF for 3 days. M-CSF-dependent adherent cells were then harvested as osteoclast and FBGC common progenitors, and 5 × 104 cells were plated in each well of 96-well culture plates. Cells were cultured with M-CSF (50 ng/ml) or M-CSF (50 ng/ml) plus RANKL (25 ng/ml) with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 2–6 days. Osteoclastogenesis was evaluated by tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) and May-Grünwald Giemsa staining (9, 32). Multinuclear cells containing more than 3 or 10 nuclei were scored as osteoclasts. Total RNAs were isolated from osteoclasts using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

For the pit formation assay, osteoclast progenitors were cultured on dentine slices in the presence of M-CSF plus RANKL for 10–12 days (33). Resorbing lacunae were visualized by toluidine blue staining, and the relative resorbing area was scored under a microscope (BZ-9000, Keyence Co., Tokyo, Japan).

For the osteoclast survival assay, wild-type or IRAK4-deficient osteoclasts induced in the presence of M-CSF plus RANKL with or without IL-1β were stained with TRAP at time 0 or were washed three times with PBS, then cultured in cytokine-free media for 3 more hours, and stained with TRAP. Multinuclear TRAP-positive cells were scored as surviving cells.

In Vitro Foreign Body Giant Cell Formation Assay

M-CSF-dependent osteoclasts and FBGC common progenitor cells were harvested as above, and 5 × 104 cells were plated in each well of 96-well culture plates. Cells were cultured in α-modified Eagle's minimum essential medium containing 10% FBS in the presence of GM-CSF (50 ng/ml) plus IL-4 (50 ng/ml) with or without the indicated concentrations of IL-1β, LPS, or zymosan for 2–4 days. Cells were then stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa (10) and observed under a microscope (BZ-9000, Keyence Co., Tokyo, Japan). Multinuclear cells containing more than three nuclei were scored as FBGCs. Total RNAs were isolated from FBGCs using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Analysis of Bone Mineral Density (BMD)

Eight-week-old male wild-type or IRAK4-deficient mice were necropsied, and their hindlimbs were removed, fixed with 70% ethanol, and subjected to dual energy x-ray absorptiometric scan analysis to measure BMD (mg/cm2), using a DCS-600R system (Aloka Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

Analysis of Skeletal Morphology

Eight-week-old female wild-type and IRAK4-deficient mice were administered intraperitoneal injections of 10 mg/kg calcein (Dojindo Co.) at 5 days and 1 day before sacrifice to evaluate bone formation rate. Left hindlimbs were removed and fixed with 70% ethanol, and undecalcified bones were embedded in glycol methacrylate. Sections of 3 μm were cut longitudinally in the proximal region of the tibia and stained with toluidine blue O. Histomorphometric measurement was performed in stained sections from the secondary spongiosa area 1.05 mm from the growth plate and 0.4 mm from the end of metaphysis using OsteoMeasure software (OsteoMetrics, Inc. Decatur, GA).

Analysis of Osteolysis in the Murine Calvarium

Wild-type or IRAK4-deficient mice were anesthetized with ketamine. A region of skin overlying the skull was shaved, and 100 μl of PBS containing LPS (50 mg/kg) was injected onto the periosteal surface of calvariae. Five days later, mice were euthanized, and calvariae were harvested for RNA isolation or a micro-computed tomography scan (R_mCT2; Rigaku Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Scanning was conducted at 90 kV and 160 μA. A three-dimensional region of interest was created at the level of the parietal bones. Osteoclast formation in calvariae was evaluated by TRAP staining or immunofluorescence staining for cathepsin K. For TRAP stain, the calvarial bone was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C with gentle shaking. After washing with PBS, sections were stained with TRAP. For cathepsin K staining, calvariae were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, decalcified in 10% EDTA (pH 7.4), embedded in paraffin, and cut into 4-μm sections. After microwave treatment for 10 min in 1 mm EDTA (pH 6.0) for antigen retrieval followed by blocking with 5% BSA/PBS for 60 min, sections were stained with anti-cathepsin K (Ctsk) (ab19027, 1:100 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) or ISO-type control antibody (3900, 1:100 dilution; Cell Signaling) overnight at 4 °C. After washing in PBS, sections were stained with Alexa Fluor 488/goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200 dilution; Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature. DAPI (1:2000; Wako Pure Chemicals Industries, Osaka, Japan) served as a nuclear stain. A fluorescence microscope (Biorevo; Keyence, Osaka, Japan) was used to examine immunostained sections.

In Vivo FBGC Formation Assay

Wild-type or IRAK4-deficient mice were anesthetized with ketamine, and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) sponges (10 × 10 × 0.5 mm) containing either PBS or LPS (25 mg/kg) were implanted into the intraperitoneal space, as described previously (17). Six days later, sponges were harvested, and histological analyses were performed using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Multinuclear cells that contained more than three nuclei and adhered to implants were scored as FBGCs. Total RNAs were isolated from sponges using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen).

Real Time PCR Analysis

Total RNAs were isolated from macrophages, osteoclasts, FBGCs, calvaria or PVA sponges, and single-stranded complementary DNAs (cDNAs) were synthesized with reverse transcriptase (Clontech). Real time PCR was performed using SYBR Premix ExTaq II (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Shiga, Japan) with a DICE Thermal cycler (Takara Bio Inc.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. β-Actin or Gapdh expression served as internal controls for real time PCR. Primers for β-actin, Ctsk, and DC-stamp were described previously (34). Other primer sequences were as follows: TNF-α-forward, 5′-AAGCCTGTAGCCCACGTCGTA-3′, and TNF-α-reverse, 5′-GGCACCACTAGTTGGTTGTCTTTG-3′; Ym1-forward, 5′-TTTGATGGCCTCAACCTGGA-3′, and Ym1-reverse, 5′-AGTGAGTAGCAGCCTTGGAATGTC-3′; Alox15-forward, 5′-TGAAGCGGTCTACTTGTCTCCCTG-3′, and Alox15-reverse, 5′-AAGGAAGAAATCCGCTTCAAACAG-3′; Trap-forward, 5′-TTGCGACCATTGTTAGCCACATA-3′, and Trap-reverse, 5′-TCAGATCCATAGTGAAACCGCAAG-3′; Gapdh-forward, 5′-AGCCTCGTCCCGTAGACAAAAT-3′, and Gapdh-reverse, 5′-ATGGCAACAATCTCCACTTTGC-3′; Fizz1-forward, 5′-GACTATGAACAGATGGGCCTCCT-3′, and Fizz1-reverse, 5′-GTCAACGAGTAAGCACAGGCAGT-3′; CD206-forward, 5′-ACCTGGCAAGTATCCACAGCATT-3′, and CD206-reverse, 5′-AATGTCACTGGGGTTCCATCACT-3′; ariginase1-forward, 5′-TTAGAGATTATCGGAGCGCCTTTC-3′, and ariginase1-reverse, 5′-CCGTGGTCTCTCACGTCATACTCT-3′; Rankl-forward, 5′-CAATGGCTGGCTTGGTTTCATAG-3′, and Rankl-reverse, 5′-CTGAACCAGACATGACAGCAGCTGGA-3′; IL-12-forward, 5′-ACCTGCTGAAGACCACAGATGAC-3′, and IL-12-reverse, 5′-GTCTTCAATGTGCTGGTTTGGTC-3′; Nos2-forward, 5′-AGAAAACCCCTTGTGCTGTTCTC-3′, and Nos2-reverse, 5′-CAGGGATTCTGGAACATTCTGTG-3′.

Western Blot Analysis

Whole cell lysates were prepared from bone marrow cultures using RIPA buffer (1% Tween 20, 0.1% SDS, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.25 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mm Na3VO4, 5 mm NaF (Sigma)). Cell lysates were collected after 10 min of centrifugation at 15,000 rpm at 4 °C. Equivalent amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore Corp.). Proteins were detected using the following antibodies: anti-Ym1 (ab93034, Abcam); anti-Alox15 (ab80221, Abcam); anti-phospho-p38 MAPK (9211, Cell Signaling); anti-p38 MAPK (9212, Cell Signaling); anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK (9106, Cell Signaling); anti-p44/42 MAPK (9102, Cell Signaling); anti-phospho-SAPK/JNK (9255, Cell Signaling); anti-SAPK/JNK (9252, Cell Signaling); anti-actin (A2066, Sigma); and isotype control (ab171870, Abcam). Bands were quantified as described (35).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the unpaired two-tailed Student's t test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; NS, not significant, throughout the paper). All data are expressed as the mean ± S.D.

RESULTS

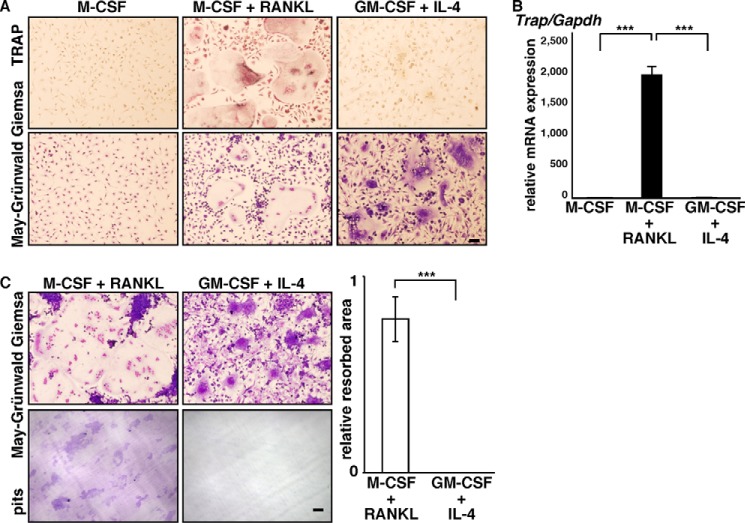

FBGCs Fail to Resorb Bone

Osteoclasts and FBGCs differentiate from common myeloid lineage precursor cells, and both form multinuclear cells by fusion (9, 17). However, we found that FBGCs were negative for TRAP, an osteoclast marker (Fig. 1A). We also found that normalized to Gapdh or β-actin, Trap mRNA expression was significantly lower in FBGCs than in osteoclasts (Fig. 1B and data not shown), as described recently (36). Thus, to assess FBGC function in bone loss, we analyzed FBGC bone resorption activity using a pit formation assay (Fig. 1C). Osteoclast and FBGC common progenitor cells were cultured on dentine slices in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL to promote an osteoclast fate or GM-CSF plus IL-4 to produce FBGCs. Samples were then stained with toluidine blue to visualize resorbing pits on slices, and the resorbing area was quantified. FBGCs completely failed to resorb bone (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

FBGCs fail to resorb bone. A and B, osteoclast and FBGC common progenitor cells were cultured in the presence of M-CSF plus RANKL (for osteoclasts) or GM-CSF plus IL-4 (for FBGCs), and cells were subjected to TRAP and May-Grünwald Giemsa staining (bar = 100 μm) (A), a real time PCR assay for Trap expression relative to Gapdh (B), or May-Grünwald Giemsa staining and a bone resorption assay on dentine slices (bar, 100 μm) (C). Data represent means ± S.D of Trap/Gapdh levels (***, p < 0.001; n = 3). Resorbing lacunae were visualized by toluidine blue staining (C, left panel), and the relative area resorbed was quantified. Data represent means ± S.D of the resorbed area in FBGC relative to osteoclast samples (***, p < 0.001; n = 3) (C, right panel). Shown are representative data of at least three independent experiments.

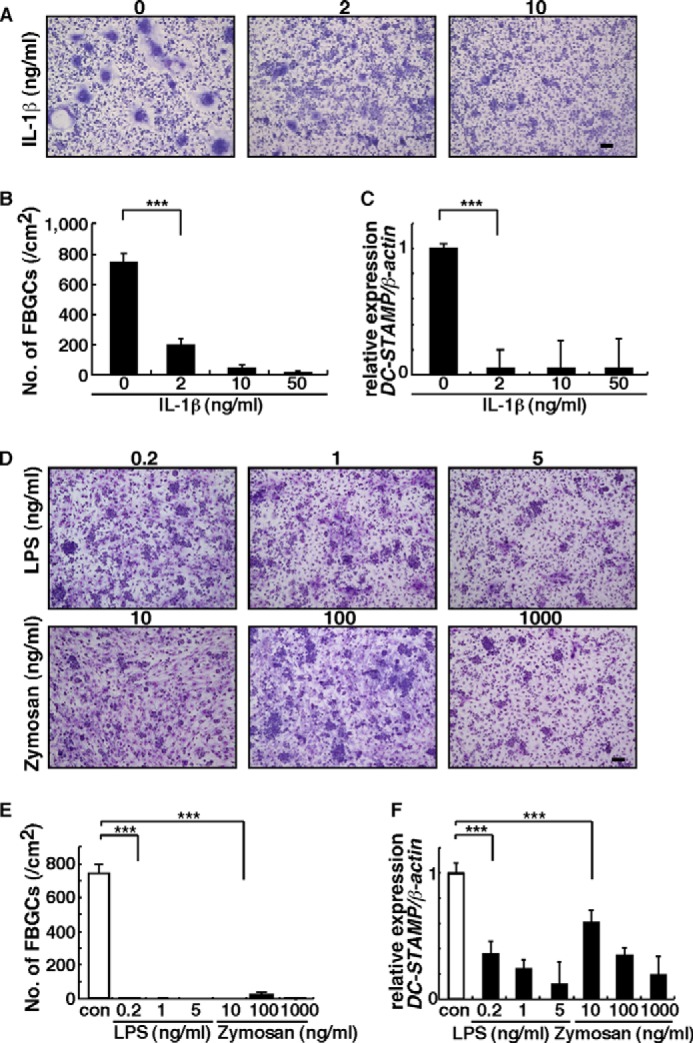

Inflammatory Cytokine, IL-1β, and Infection Mimetics, LPS or Zymosan, Inhibit FBGC Formation in Vitro

Because device failure is frequently associated with inflammation and infection (2, 3, 37), we asked whether FBGC differentiation is stimulated by inflammatory cytokines or infections. To do so, we treated FBGCs grown in culture with the inflammatory cytokine IL-1β, which is reportedly expressed at the FBR site (38), or with components of the bacterial or yeast cell wall, LPS, or zymosan, respectively (Fig. 2). Interestingly, multinuclear FBGC formation was significantly inhibited in the presence of IL-1β dose-dependently (Fig. 2, A and B). Expression of DC-STAMP, a factor essential for cell-cell fusion of either osteoclasts or FBGCs (9), was also significantly inhibited in FBGCs treated with IL-1β (Fig. 2C). Multinuclear FBGC formation and FBGC DC-STAMP expression were also significantly inhibited by LPS or zymosan, dose-dependently (Fig. 2, D–F). These findings strongly suggest that FBGC formation is inhibited under inflammatory or infectious conditions.

FIGURE 2.

Inflammation and infection inhibit FBGC formation. A, B, D, and E, osteoclast and FBGC progenitor cells were cultured in the presence of GM-CSF plus IL-4 with or without indicated concentrations of IL-1β, LPS, or zymosan for 5 days, stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa (bar, 100 μm) (A and D), and scored for the number of multinuclear FBGCs containing more than three nuclei (***, p < 0.001; n = 3) (B and E). Representative data of at least three independent experiments are shown. C and F, total RNAs were prepared from FBGCs treated with or without indicated concentrations of IL-1β, LPS, or zymosan, and DC-STAMP expression relative to β-actin was analyzed by quantitative real time PCR. Data represent means ± S.D. of DC-STAMP/β-actin levels (***, p < 0.001; n = 3). Representative data of at least three independent experiments are shown. con, control.

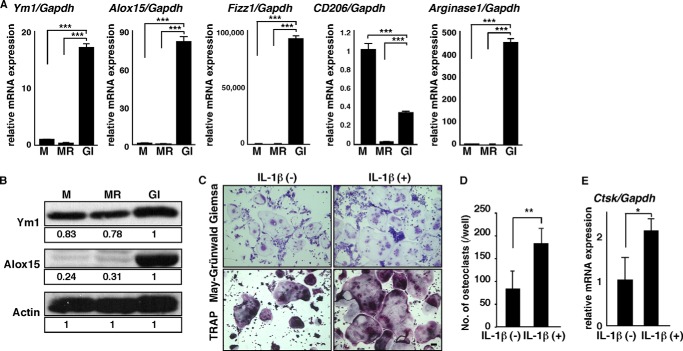

To further assess FBGC function in the FBR, we analyzed expression of chitinase-like 3 (Ym1) and arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase (Alox15) in FBGCs, macrophages, and osteoclasts by real time PCR (Fig. 3A). Ym1 is a known M2 macrophage marker, and ALOX15 encodes an enzyme functioning in wound healing and termination of inflammation (39–43). Interestingly, expression levels of both transcripts in FBGCs were significantly higher than those in macrophages and osteoclasts. Similarly, relative to Gapdh or β-actin, transcript levels of other M2 macrophage markers such as Fizz1, CD206, and ariginase1 were significantly higher in FBGCs than in osteoclasts (Fig. 3A and data not shown). Western blot analysis also indicated high expression of Ym1 and Alox15 proteins in FBGCs relative to osteoclasts; ISO-type control antibody showed no bands the size of Ym1 and Alox15 proteins (Fig. 3B and data not shown). By contrast, osteoclastogenesis shown by multinuclear TRAP-positive cell formation and cathepsin K expression was significantly stimulated by IL-1β (Fig. 3, C–E). Overall, these results suggest that FBGCs function in wound healing and FBR termination and that FBGCs and osteoclasts are reciprocally regulated.

FIGURE 3.

FBGCs express wound-healing molecules, and IL-1β stimulates osteoclastogenesis. A and B, osteoclast and FBGC common progenitor cells were cultured in the presence of M-CSF alone (M) to induce macrophages, M-CSF plus RANKL (MR) to induce osteoclasts, or GM-CSF plus IL-4 (GI) to induce FBGCs. Expression of Ym1, Alox15, Fizz1, CD206, or ariginase1 transcripts relative to Gapdh and expression of Ym1 and Alox15 protein were analyzed by quantitative real time PCR (A) and Western blotting (B), respectively. Data represent means ± S.D. of Ym1/Gapdh, Alox15/Gapdh, Fizz1/Gapdh, CD206/Gapdh, or arginase1/Gapdh levels (***, p < 0.001; n = 3). Actin protein expression served as an internal control. Relative Ym1 or Alox15 protein levels determined by immunoblot were quantified by densitometry and are shown as values relative to levels in FBGCs (GI). Representative data of at least three independent experiments are shown. C and D, osteoclast and FBGC common progenitor cells were cultured in the presence of M-CSF plus RANKL with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 5 days and then subjected to May-Grünwald Giemsa and TRAP staining (bar, 100 μm) (C). The number of multinuclear osteoclasts containing more than three nuclei was then scored (**, p < 0.01, n = 3) (D). E, total RNAs were prepared from osteoclasts treated with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 3 days, and Ctsk expression relative to Gapdh was analyzed by quantitative real time PCR. Data represent means ± S.D, of Ctsk/Gapdh levels (*, p < 0.05; n = 3). Representative data from at least three independent experiments are shown.

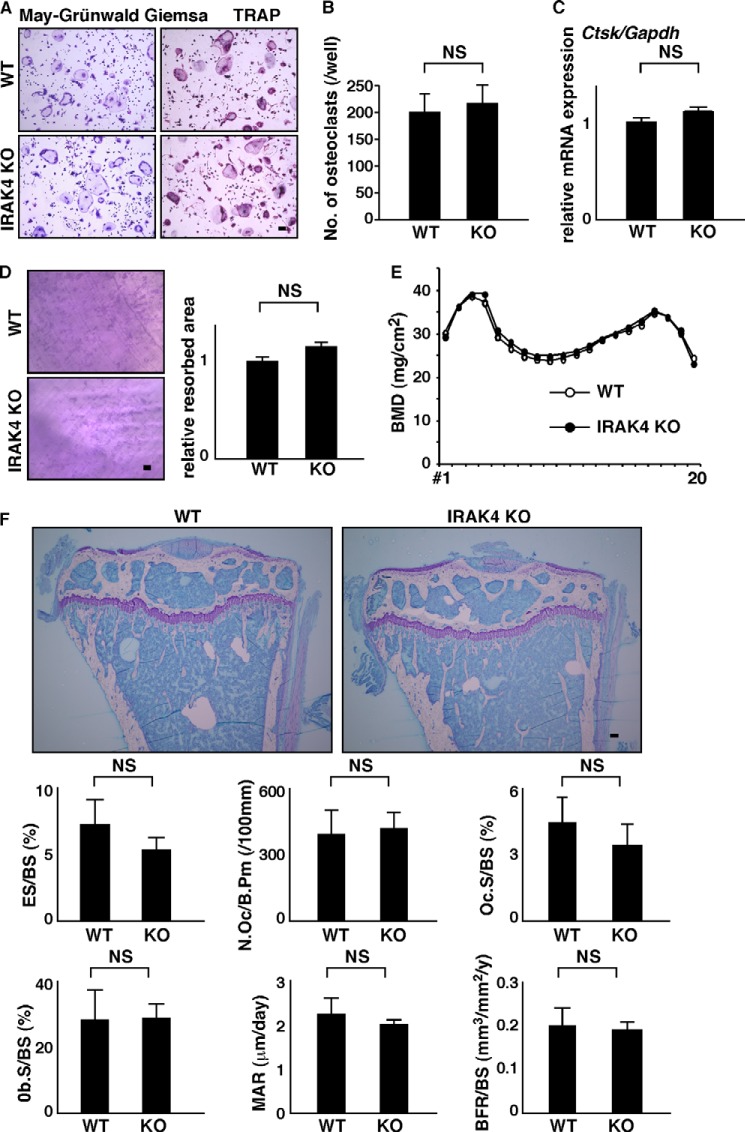

IRAK4 Is a Reciprocal Switch for FBGC and Osteoclast Differentiation

We next asked what factor(s) might stimulate FBGCs while inhibiting excessive osteoclastogenesis. Although inflammatory cytokine or LPS stimulation activates various downstream factors (44, 45), we focused on IRAK4, because it is reportedly critical for both IL-1 and toll-like receptor signaling (28). To assess IRAK4 function, we isolated FBGCs and osteoclast common progenitor cells from IRAK4-deficient or wild-type mice and cultured them in the presence of M-CSF plus RANKL (Fig. 4). Multinuclear TRAP-positive osteoclast formation and cathepsin K (Ctsk) expression did not differ between IRAK4-deficient and wild-type cells in vitro (Fig. 4, A–C). Bone-resorbing activity, as determined by a pit formation assay, was comparable in IRAK4-deficient and wild-type osteoclasts in vitro (Fig. 4D). BMD, as analyzed by a dual energy x-ray absorptiometric scan, was also equivalent between IRAK4-deficient and wild-type mice in vivo (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, bone morphometric analysis and toluidine blue O staining of tibial bones in knock-out and wild-type mice indicated that IRAK4 loss did not alter osteoclastic and osteoblastic parameters such as eroded surface/bone surface (BS), number of osteoclasts per bone perimeter, Oc surface/BS, osteoblast surface/BS, mineral apposition rate, or bone formation rate/BS in vivo (Fig. 4F). Thus, we conclude that IRAK4 does not regulate physiological osteoclast differentiation or bone mass.

FIGURE 4.

Normal osteoclastogenesis and bone mass in IRAK4-deficient mice. A–C, osteoclast and FBGC common progenitor cells were isolated from wild-type or IRAK4-deficient mice and cultured in the presence of M-CSF plus RANKL for 4 days. Cells were then stained with TRAP (bar, 100 μm) (A), scored for the number of multinuclear osteoclasts containing more than three nuclei (NS, not significant; n = 3) (B), and analyzed for Ctsk expression relative to Gapdh by quantitative real time PCR (C). Resorption pits appearing on dentine slices were visualized by toluidine blue staining (D, left panel), and the relative resorbed area was quantified (NS, not significant; n = 3) (D, right panel) (bar, 200 μm). Representative data from at least three independent experiments are shown. E, BMD of femurs divided equally longitudinally from wild-type and IRAK4-deficient mice. Representative data of two independent experiments are shown (n = 5). F, representative toluidine blue O staining images and bone morphometric analysis of 8-week-old female wild-type or IRAK4-deficient mice. Shown are toluidine blue O staining, eroded surface per bone surface (ES/BS), the number of osteoclasts per bone perimeter (N.Oc/B.Pm), osteoclast surface per bone surface (OcS/BS), osteoblast surface per bone surface (ObS/BS), mineral apposition rate (MAR), and bone formation rate per bone surface (BFR/BS). Data are quantified as means ± S.D. NS, not significant, n = 4 (WT) and 5 (KO).

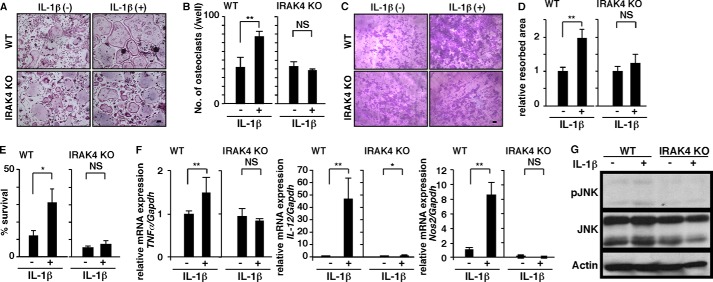

By contrast, we found that increased osteoclastogenesis and osteolysis induced by IL-1β in wild-type cells was significantly inhibited in IRAK4-deficient cells in vitro (Fig. 5, A–D). IL-1β promoted osteoclast survival in wild-type but not in IRAK4-deficient osteoclasts in vitro (Fig. 5E). Osteoclastogenesis activated by IL-1β is considered a phenotypic indicator of M1 polarization. Accordingly, we observed significantly up-regulated expression of M1 markers such as TNFα, IL-12, and nitric oxide synthase 2 (Nos2) in wild-type osteoclasts (Fig. 5F), an activity blocked in IRAK4-deficient osteoclasts (Fig. 5F), suggesting that M1 polarization in osteoclasts promoted by IL-1β treatment is IRAK4-dependent. MAPK activation is known to promote osteoclast formation and survival. We found that, although p38 and ERK activation was unchanged (data not shown), JNK was activated by IL-1β in wild-type cells but not in IRAK4-deficient cells in vitro (Fig. 5G). These results suggest that IRAK4 transduces activating signals underlying osteoclast formation and survival through JNK activation.

FIGURE 5.

IRAK4 transduces an osteoclast-activating signal by IL-1β. A–D, osteoclast and FBGC common progenitor cells were isolated from wild-type or IRAK4-deficient mice and cultured in the presence of M-CSF plus RANKL with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 4 days. Cells were then stained with TRAP (bar, 100 μm) (A), and the number of multinuclear osteoclasts containing more than 10 nuclei was scored (**, p < 0.01; NS, not significant; n = 3) (B). A bone resorption assay on dentine slices was visualized by toluidine blue staining (C) (bar, 100 μm), and the relative resorbed area was quantified (**, p < 0.01; NS, not significant, n = 3) (D). E, osteoclasts formed in wild-type and IRAK4-deficient cells in the presence of M-CSF plus RANKL with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml). Cells were then stained with TRAP at time 0, or cultured without cytokines for 3 h and then stained with TRAP. The number of surviving cells was scored at time 0 and 3 h. Osteoclast survival rate is represented as the percentage of living osteoclasts present after 3 h of incubation relative to the number at time zero. Data represent mean number of surviving cells ± S.D. (*, p < 0.05; NS, not significant; n = 3). F, total RNAs were prepared from wild-type or IRAK4-deficient osteoclasts treated with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 2 days, and TNFα, IL-12 or Nos2 expression relative to Gapdh was analyzed by quantitative real time PCR. Data represent means ± S.D. of TNFα, IL-12, or Nos2 relative to Gapdh (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, n = 3). G, osteoclast and FBGC common progenitor cells were isolated from wild-type or IRAK4-deficient mice, starved in serum-free media for 2 h, and stimulated with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. JNK activation was then analyzed by Western blot. Representative data of at least three independent experiments are shown.

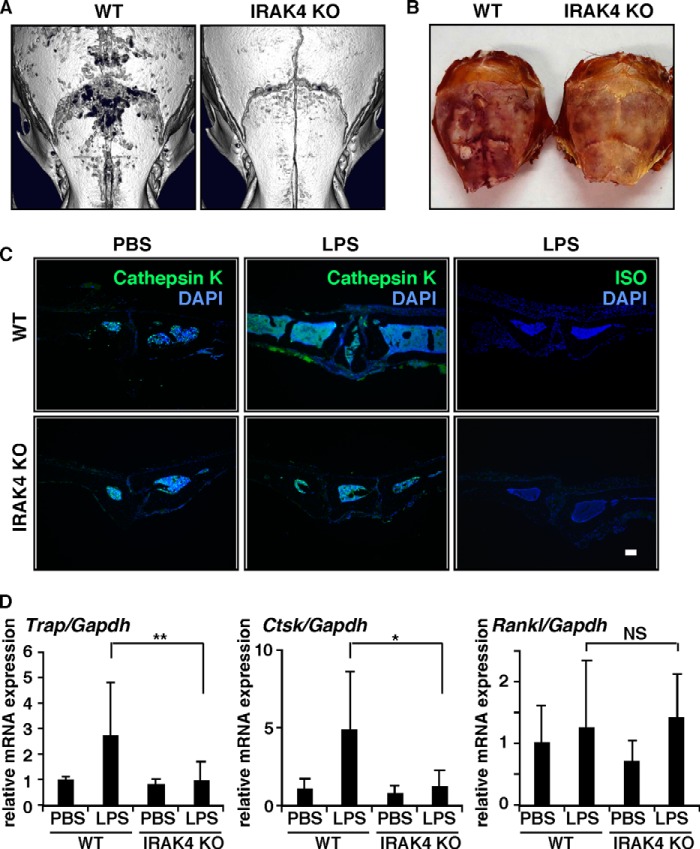

In vivo, we found that calvarial osteolysis induced by LPS administration in wild-type mice was abrogated in IRAK4-deficient mice (Fig. 6A). Increased TRAP- or cathepsin K-positive osteoclast formation and cellular migration into calvarial bones induced by LPS in wild-type mice were absent in IRAK4-deficient mice in vivo (Fig. 6, B–D). Because cathepsin K expression is significantly higher in osteoclasts than in osteoblasts (data not shown), we conclude that LPS-stimulated cathepsin K expression in wild-type calvarial bones is due to activated osteoclast formation. Receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (Rankl), a cytokine essential for osteoclastogenesis, is reportedly induced by LPS (46). In our model, Rankl expression was induced to similar levels by LPS in both wild-type and IRAK4-deficient mice in vivo (Fig. 6D).

FIGURE 6.

IRAK4 is a specific target for pathological osteolysis. A–D, PBS or LPS (50 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously to the skull of wild-type or IRAK4-deficient mice. Five days later, osteolysis in calvariae was evaluated by micro-computed tomography (A), and osteoclast formation in calvariae was examined by TRAP staining (B) and immunohistochemical staining for cathepsin K or ISO-type control antibody (C) (bar, 100 μm; n = 3–5). Expression of Trap, Ctsk, and Rankl was also analyzed by real time PCR (D). Data represent means ± S.D. of Trap/Gapdh, Ctsk/Gapdh, or Rankl/Gapdh levels (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; NS, not significant; n = 4–11).

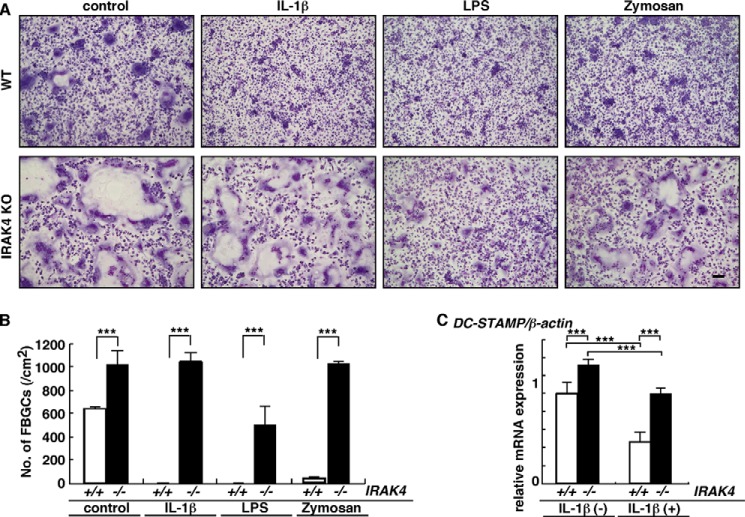

FBGC formation in IRAK4-deficient cells not treated with exogenous factors was significantly elevated compared with wild-type cells, and inhibition of FBGC formation by IL-1β, LPS, or zymosan was significantly rescued in IRAK4-deficient cells in vitro (Fig. 7, A and B). Although DC-STAMP expression was significantly inhibited in IRAK4-deficient cells by IL-1β treatment, that inhibition was less significant in IRAK4-deficient compared with wild-type cells (Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 7.

Loss of IRAK4 rescues FBGC formation inhibited by IL-1β, LPS, or zymosan. A and B, osteoclast and FBGC common progenitor cells were isolated from wild-type or IRAK4-deficient mice and cultured as FBGCs in the presence of GM-CSF plus IL-4 with or without IL-1β (2 ng/ml), LPS (0.2 ng/ml), or zymosan (100 ng/ml). Cells were stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa (bar, 100 μm) (A), and the number of multinuclear FBGCs containing more than three nuclei was scored (B). (***, p < 0.001; n = 3.) C, total RNAs were prepared from FBGCs treated with (+) or without (−) IL-1β, and DC-STAMP expression relative to β-actin was analyzed by quantitative real time PCR. Data represent means ± S.D. of DC-STAMP/β-actin levels (***, p < 0.001, n = 3). Representative data of at least three independent experiments are shown.

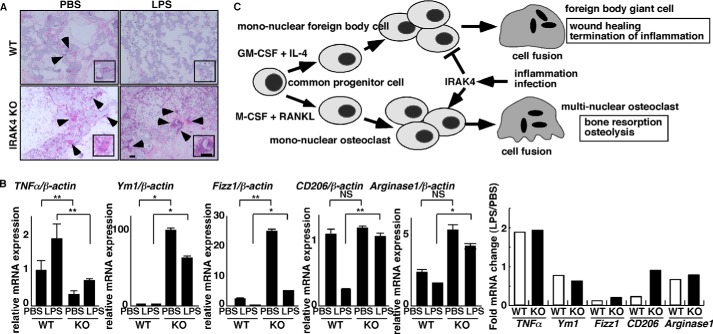

Finally, we asked whether blocking IRAK4 regulates the FBR in vivo. To do so, we implanted PVA sponges either with or without LPS into the peritoneal cavity of IRAK4-deficient or wild-type mice to represent foreign bodies, and we then analyzed FBGC formation in sponges and expression of wound-healing factors in cells infiltrating those bodies by real time PCR (Fig. 8). FBGCs formed in sponges lacking LPS in both knock-out and wild-type mice, but FBGC formation was more robust in IRAK4-deficient mice (Fig. 8A). Also, in the absence of LPS, expression of TNFα, an inflammatory cytokine and an M1 macrophage marker, was significantly lower IRAK4-deficient relative to wild-type mice, whereas expression of Ym1 and Fizz1, both M2 markers, was significantly higher (Fig. 8B), suggesting that cells infiltrating sponges in IRAK4-deficient mice were significantly M2-polarized compared with those in wild-type mice. Furthermore, in wild-type mice FBGC formation was inhibited by inclusion of LPS in the sponge, but that activity was blocked in IRAK4-deficient mice (Fig. 8A). Also in the presence of LPS, TNFα expression was significantly lower in IRAK4-deficient compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 8B). In contrast, Ym1, Alox15, Fizz1, CD206, and arginase1 expression was significantly higher in cells from sponges implanted in IRAK4-deficient compared with wild-type mice in the presence of LPS in vivo (Fig. 8B). Differences in expression of mRNAs encoding M2 markers, such as Fizz1, CD206, and arginase1, seen following LPS treatment of wild-type mice, were less apparent in IRAK4-deficient mice (Fig. 8B). Taken together, these results suggest that IRAK4 functions as a differentiation switch in reciprocal regulation of FBGCs and osteoclasts (Fig. 8C).

FIGURE 8.

IRAK4 is a potential therapeutic target regulating the FBR in vivo. A and B, foreign bodies (PVA sponges soaked with PBS or LPS (25 mg/kg)) were implanted into peritoneal spaces in wild-type or IRAK4-deficient mice. After 6 days, foreign bodies were dissected, and tissue sections were stained with H&E (A) (bar, 100 μm). Alternatively, total RNAs were prepared from cells contained in foreign bodies and TNFα, Ym1, Fizz1, CD206; and arginase1 expression relative to β-actin was analyzed by quantitative real time PCR (B, left panels). Data represent means ± S.D. of TNFα/β-actin, Ym1/β-actin, Fizz1/β-actin, CD206/β-actin, or arginase1/β-actin levels (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; NS, not significant; n = 5–12) (B, right panel). Fold changes in mRNA expression between LPS-induced versus PBS-treated samples, shown as LPS/PBS. Representative data of at least three independent experiments are shown. C, schematic model of FBGC and osteoclast formation regulated by IRAK4 under inflammatory or infectious conditions. FBGC or osteoclast formation is induced in the presence of GM-CSF plus IL-4 or M-CSF plus RANKL, respectively, from common progenitor cells. Both FBGCs and osteoclasts form multinuclear cells by fusion of mononuclear cells. Inflammation or infection activates IRAK4 and inhibits FBGC formation while stimulating osteoclastogenesis, an event underlying implant failure. Multinucleation of FBGCs likely elevates wound healing efficiency, although osteoclasts mediate bone-resorbing activity.

DISCUSSION

Failure of biomedical implants severely limits activities of daily living and increases health care expenses. Biomaterial implant into tissues promotes FBR development, a condition associated with implant failure (2, 3, 37). The FBR develops in response to implantation of almost all biomaterials; this can occur throughout the body and is detrimental to device function (47, 48). Thus, controlling FBR is crucial to protect implants from failures and for human lives. We show that FBGCs do not resorb bones, but rather they express wound healing and inflammation-terminating molecules. Our study also demonstrates that targeting IRAK4 could inhibit elevation of pathologically activated osteoclasts and enable normal FBGC formation, thereby preventing osteolysis (Fig. 8C).

Some investigators have concluded that repressing FBGCs may prevent implant failure in part because FBGCs express enzymes such as MMP9, which can degrade biomaterials or tissues (7). Interestingly, however, MMP9 also reportedly functions in tissue or extracellular matrix protein remodeling (49, 50). Khan et al. (36) reported a lower expression of MMP9 and Trap in FBGCs than in osteoclasts and that FBGCs did not degrade gelatin. We also found that FBGCs expressed significantly lower Trap levels than did osteoclasts and failed to resorb bone. Instead, FBGCs expressed factors characteristic of M2 macrophages such as Ym1 and Alox15 (27).

A caveat of our study is that we did not assess implanted bones or evaluate the relationship of osteoclast and FBGC formation in implanted materials in bones. Thus, further studies are needed to examine IRAK4 function in the FBR in those contexts. Furthermore, M1/M2 polarization is considered microenvironment-dependent, and although FBGCs express wound-healing factors, it remains to be tested whether FBGCs themselves would have beneficial effects on implant device longevity.

A balance in M1 and M2 macrophage polarization likewise determines the balance between inflammation and anti-inflammatory/wound healing status. Recently, studies of tissues harvested from revised joint replacements reported that pro-inflammatory M1 factors were predominant over M2 anti-inflammatory molecules (51–54). Moreover, Rao et al. (55) reported that IL-4, an M2 macrophage activator, mitigated polyethylene particle-induced osteolysis through macrophage polarization. Our data indicate that osteoclasts excessively activated by pro-inflammatory cytokines or TLR ligands such as IL-1β and LPS are phenotypically M1 macrophages and are required for osteolysis. By contrast, activity of FBGCs, which are considered M2 macrophages and are induced by IL-4, could terminate the FBR and prevent osteolysis.

A major finding of this study is that FBGC and osteoclast differentiation is reciprocally regulated. IRAK4 is a key molecule required for M1/M2 polarization. Antagonizing IRAK4 activity could potentially stimulate FBGC formation and inhibit osteoclastogenesis under inflammatory conditions. A recent report shows that LPS induces multinuclear cell formation by Raw264.7 pre-osteoclastic macrophage cells in vitro (46). Although M2 marker expression was not addressed in that study, TNFα expression was induced in those multinuclear cells, suggesting that LPS likely promotes their M1 polarization.

Severe inhibition of osteoclast activity beyond physiological levels by osteoclast-inhibiting agents such as bisphosphonate frequently promotes osteonecrosis of the jaws and severely suppressed bone turnover (21–23, 56, 57). The inability of bone to heal microcracks due to low bone turnover is considered a cause of atypical fracture (58). However, our findings demonstrate that IRAK4 loss did not alter physiological osteoclast differentiation/function required for bone turnover but rather inhibited pathologically activated osteoclasts. Taken together, IRAK4 could serve as a therapeutic target to antagonize inflammatory osteolysis and implant failure without adversely affecting physiological bone metabolism.

Acknowledgment

We thank Prof. Takami (School of Dentistry, Showa University) for technical support.

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for scientific research.

- FBR

- foreign body response

- FBGC

- foreign body giant cell

- DC-STAMP

- dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein

- RANKL

- nuclear factor κ-B ligand

- TRAP

- tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

- BS

- bone surface

- OC

- osteoclast surface

- PVA

- polyvinyl alcohol

- BMD

- bone mineral density.

REFERENCES

- 1. Marwick C. (2000) Implant recommendations. JAMA 283, 869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tang L., Eaton J. W. (1995) Inflammatory responses to biomaterials. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 103, 466–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tang L., Eaton J. W. (1999) Natural responses to unnatural materials: a molecular mechanism for foreign body reactions. Mol. Med. 5, 351–358 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson J. M. (1988) Inflammatory response to implants. Am. Soc. Artif. Intern. Organs 34, 101–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao Q., Topham N., Anderson J. M., Hiltner A., Lodoen G., Payet C. R. (1991) Foreign-body giant cells and polyurethane biostability: in vivo correlation of cell adhesion and surface cracking. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 25, 177–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anderson J. M., Rodriguez A., Chang D. T. (2008) Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin. Immunol. 20, 86–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. MacLauchlan S., Skokos E. A., Meznarich N., Zhu D. H., Raoof S., Shipley J. M., Senior R. M., Bornstein P., Kyriakides T. R. (2009) Macrophage fusion, giant cell formation, and the foreign body response require matrix metalloproteinase 9. J. Leukocyte Biol. 85, 617–626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aronson M., Elberg S. S. (1962) Fusion of peritoneal histocytes with formation of giant cells. Nature 193, 399–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yagi M., Miyamoto T., Sawatani Y., Iwamoto K., Hosogane N., Fujita N., Morita K., Ninomiya K., Suzuki T., Miyamoto K., Oike Y., Takeya M., Toyama Y., Suda T. (2005) DC-STAMP is essential for cell-cell fusion in osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J. Exp. Med. 202, 345–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yagi M., Ninomiya K., Fujita N., Suzuki T., Iwasaki R., Morita K., Hosogane N., Matsuo K., Toyama Y., Suda T., Miyamoto T. (2007) Induction of DC-STAMP by alternative activation and downstream signaling mechanisms. J. Bone Miner. Res. 22, 992–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee S. H., Rho J., Jeong D., Sul J. Y., Kim T., Kim N., Kang J. S., Miyamoto T., Suda T., Lee S. K., Pignolo R. J., Koczon-Jaremko B., Lorenzo J., Choi Y. (2006) v-ATPase V0 subunit d2-deficient mice exhibit impaired osteoclast fusion and increased bone formation. Nat. Med. 12, 1403–1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saginario C., Sterling H., Beckers C., Kobayashi R., Solimena M., Ullu E., Vignery A. (1998) MFR, a putative receptor mediating the fusion of macrophages. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 6213–6223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Han X., Sterling H., Chen Y., Saginario C., Brown E. J., Frazier W. A., Lindberg F. P., Vignery A. (2000) CD47, a ligand for the macrophage fusion receptor, participates in macrophage multinucleation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 37984–37992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sterling H., Saginario C., Vignery A. (1998) CD44 occupancy prevents macrophage multinucleation. J. Cell Biol. 143, 837–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cui W., Ke J. Z., Zhang Q., Ke H. Z., Chalouni C., Vignery A. (2006) The intracellular domain of CD44 promotes the fusion of macrophages. Blood 107, 796–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Helming L., Gordon S. (2009) Molecular mediators of macrophage fusion. Trends Cell Biol. 19, 514–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miyamoto H., Suzuki T., Miyauchi Y., Iwasaki R., Kobayashi T., Sato Y., Miyamoto K., Hoshi H., Hashimoto K., Yoshida S., Hao W., Mori T., Kanagawa H., Katsuyama E., Fujie A., Morioka H., Matsumoto M., Chiba K., Takeya M., Toyama Y., Miyamoto T. (2012) Osteoclast stimulatory transmembrane protein and dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein cooperatively modulate cell-cell fusion to form osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 1289–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Suratwala S. J., Cho S. K., van Raalte J. J., Park S. H., Seo S. W., Chang S. S., Gardner T. R., Lee F. Y. (2008) Enhancement of periprosthetic bone quality with topical hydroxyapatite-bisphosphonate composite. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 90, 2189–2196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin T., Yan S. G., Cai X. Z., Ying Z. M. (2012) Bisphosphonates for periprosthetic bone loss after joint arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of 14 randomized controlled trials. Osteoporos. Int. 23, 1823–1834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whyte M. P., McAlister W. H., Novack D. V., Clements K. L., Schoenecker P. L., Wenkert D. (2008) Bisphosphonate-induced osteopetrosis: novel bone modeling defects, metaphyseal osteopenia, and osteosclerosis fractures after drug exposure ceases. J. Bone Miner. Res. 23, 1698–1707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Edwards B. J., Bunta A. D., Lane J., Odvina C., Rao D. S., Raisch D. W., McKoy J. M., Omar I., Belknap S. M., Garg V., Hahr A. J., Samaras A. T., Fisher M. J., West D. P., Langman C. B., Stern P. H. (2013) Bisphosphonates and nonhealing femoral fractures: analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) and international safety efforts: a systematic review from the Research on Adverse Drug Events And Reports (RADAR) project. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 95, 297–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gedmintas L., Solomon D. H., Kim S. C. (2013) Bisphosphonates and risk of subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and atypical femur fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 28, 1729–1737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Visekruna M., Wilson D., McKiernan F. E. (2008) Severely suppressed bone turnover and atypical skeletal fragility. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93, 2948–2952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mantovani A., Sica A., Locati M. (2005) Macrophage polarization comes of age. Immunity 23, 344–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lawrence T., Natoli G. (2011) Transcriptional regulation of macrophage polarization: enabling diversity with identity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 750–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sica A., Mantovani A. (2012) Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 787–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Biswas S. K., Chittezhath M., Shalova I. N., Lim J. Y. (2012) Macrophage polarization and plasticity in health and disease. Immunol. Res. 53, 11–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Suzuki N., Suzuki S., Duncan G. S., Millar D. G., Wada T., Mirtsos C., Takada H., Wakeham A., Itie A., Li S., Penninger J. M., Wesche H., Ohashi P. S., Mak T. W., Yeh W. C. (2002) Severe impairment of interleukin-1 and Toll-like receptor signalling in mice lacking IRAK-4. Nature 416, 750–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Suzuki N., Chen N. J., Millar D. G., Suzuki S., Horacek T., Hara H., Bouchard D., Nakanishi K., Penninger J. M., Ohashi P. S., Yeh W. C. (2003) IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 is essential for IL-18-mediated NK and Th1 cell responses. J. Immunol. 170, 4031–4035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Suzuki N., Suzuki S., Eriksson U., Hara H., Mirtosis C., Chen N. J., Wada T., Bouchard D., Hwang I., Takeda K., Fujita T., Der S., Penninger J. M., Akira S., Saito T., Yeh W. C. (2003) IL-1R-associated kinase 4 is required for lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of APC. J. Immunol. 171, 6065–6071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Suzuki N., Suzuki S., Millar D. G., Unno M., Hara H., Calzascia T., Yamasaki S., Yokosuka T., Chen N. J., Elford A. R., Suzuki J., Takeuchi A., Mirtsos C., Bouchard D., Ohashi P. S., Yeh W. C., Saito T. (2006) A critical role for the innate immune signaling molecule IRAK-4 in T cell activation. Science 311, 1927–1932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nawroth P. P., Bank I., Handley D., Cassimeris J., Chess L., Stern D. (1986) Tumor necrosis factor/cachectin interacts with endothelial cell receptors to induce release of interleukin 1. J. Exp. Med. 163, 1363–1375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Miyamoto T., Arai F., Ohneda O., Takagi K., Anderson D. M., Suda T. (2000) An adherent condition is required for formation of multinuclear osteoclasts in the presence of macrophage colony-stimulating factor and receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand. Blood 96, 4335–4343 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miyauchi Y., Miyamoto H., Yoshida S., Mori T., Kanagawa H., Katsuyama E., Fujie A., Hao W., Hoshi H., Miyamoto K., Sato Y., Kobayashi T., Akiyama H., Morioka H., Matsumoto M., Toyama Y., Miyamoto T. (2012) Conditional inactivation of Blimp1 in adult mice promotes increased bone mass. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 28508–28517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hoshi H., Hao W., Fujita Y., Funayama A., Miyauchi Y., Hashimoto K., Miyamoto K., Iwasaki R., Sato Y., Kobayashi T., Miyamoto H., Yoshida S., Mori T., Kanagawa H., Katsuyama E., Fujie A., Kitagawa K., Nakayama K. I., Kawamoto T., Sano M., Fukuda K., Ohsawa I., Ohta S., Morioka H., Matsumoto M., Chiba K., Toyama Y., Miyamoto T. (2012) Aldehyde-stress resulting from Aldh2 mutation promotes osteoporosis due to impaired osteoblastogenesis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 2015–2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Khan U. A., Hashimi S. M., Khan S., Quan J., Bakr M. M., Forwood M. R., Morrison N. M. (2014) Differential expression of chemokines, chemokine receptors and proteinases by foreign body giant cells (FBGCs) and osteoclasts. J. Cell. Biochem. 115, 1290–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mikos A. G., McIntire L. V., Anderson J. M., Babensee J. E. (1998) Host response to tissue engineered devices. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 33, 111–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jones J. A., Chang D. T., Meyerson H., Colton E., Kwon I. K., Matsuda T., Anderson J. M. (2007) Proteomic analysis and quantification of cytokines and chemokines from biomaterial surface-adherent macrophages and foreign body giant cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 83, 585–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Raes G., Noël W., Beschin A., Brys L., de Baetselier P., Hassanzadeh G. H. (2002) FIZZ1 and Ym as tools to discriminate between differentially activated macrophages. Dev. Immunol. 9, 151–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gronert K., Maheshwari N., Khan N., Hassan I. R., Dunn M., Laniado Schwartzman M. (2005) A role for the mouse 12/15-lipoxygenase pathway in promoting epithelial wound healing and host defense. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 15267–15278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Biteman B., Hassan I. R., Walker E., Leedom A. J., Dunn M., Seta F., Laniado-Schwartzman M., Gronert K. (2007) Interdependence of lipoxin A4 and heme-oxygenase in counter-regulating inflammation during corneal wound healing. FASEB J. 21, 2257–2266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mosser D. M., Edwards J. P. (2008) Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 958–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Uderhardt S., Krönke G. (2012) 12/15-Lipoxygenase during the regulation of inflammation, immunity, and self-tolerance. J. Mol. Med. 90, 1247–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lomaga M. A., Yeh W. C., Sarosi I., Duncan G. S., Furlonger C., Ho A., Morony S., Capparelli C., Van G., Kaufman S., van der Heiden A., Itie A., Wakeham A., Khoo W., Sasaki T., Cao Z., Penninger J. M., Paige C. J., Lacey D. L., Dunstan C. R., Boyle W. J., Goeddel D. V., Mak T. W. (1999) TRAF6 deficiency results in osteopetrosis and defective interleukin-1, CD40, and LPS signaling. Genes Dev. 13, 1015–1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kim T. W., Staschke K., Bulek K., Yao J., Peters K., Oh K. H., Vandenburg Y., Xiao H., Qian W., Hamilton T., Min B., Sen G., Gilmour R., Li X. (2007) A critical role for IRAK4 kinase activity in Toll-like receptor-mediated innate immunity. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1025–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nakanishi-Matsui M., Yano S., Futai M. (2013) Lipopolysaccharide-induced multinuclear cells: increased internalization of polystyrene beads and possible signals for cell fusion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 440, 611–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kyriakides T. R., Foster M. J., Keeney G. E., Tsai A., Giachelli C. M., Clark-Lewis I., Rollins B. J., Bornstein P. (2004) The CC chemokine ligand, CCL2/MCP1, participates in macrophage fusion and foreign body giant cell formation. Am. J. Pathol. 165, 2157–2166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Luttikhuizen D. T., Harmsen M. C., Van Luyn M. J. (2006) Cellular and molecular dynamics in the foreign body reaction. Tissue Eng. 12, 1955–1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Amano S., Naganuma K., Kawata Y., Kawakami K., Kitano S., Hanazawa S. (1996) Prostaglandin E, stimulates osteoclast formation via endogenous IL-1β expressed through protein kinase A. J. Immunol. 156, 1931–1936 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Okada Y., Lorenzo J. A., Freeman A. M., Tomita M., Morham S. G., Raisz L. G., Pilbeam C. C. (2000) Prostaglandin G/H synthase-2 is required for maximal formation of osteoclast-like cells in culture. J. Clin. Invest. 105, 823–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ingham E., Fisher J. (2005) The role of macrophages in osteolysis of total joint replacement. Biomaterials 26, 1271–1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang S. Y., Yu H., Gong W., Wu B., Mayton L., Costello R., Wooley P. H. (2007) Murine model of prosthesis failure for the long-term study of aseptic loosening. J. Orthop. Res. 25, 603–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rao A. J., Gibon E., Ma T., Yao Z., Smith R. L., Goodman S. B. (2012) Revision joint replacement, wear particles, and macrophage polarization. Acta Biomater. 8, 2815–2823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nich C., Takakubo Y., Pajarinen J., Ainola M., Salem A., Sillat T., Rao A. J., Raska M., Tamaki Y., Takagi M., Konttinen Y. T., Goodman S. B., Gallo J. (2013) Macrophages–key cells in the response to wear debris from joint replacements. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 101, 3033–3045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rao A. J., Nich C., Dhulipala L. S., Gibon E., Valladares R., Zwingenberger S., Smith R. L., Goodman S. B. (2013) Local effect of IL-4 delivery on polyethylene particle induced osteolysis in the murine calvarium. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 101, 1926–1934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Khan A. A., Sándor G. K., Dore E., Morrison A. D., Alsahli M., Amin F., Peters E., Hanley D. A., Chaudry S. R., Lentle B., Dempster D. W., Glorieux F. H., Neville A. J., Talwar R. M., Clokie C. M., Mardini M. A., Paul T., Khosla S., Josse R. G., Sutherland S., Lam D. K., Carmichael R. P., Blanas N., Kendler D., Petak S., Ste-Marie L. G., Brown J., Evans A. W., Rios L., Compston J. E., Canadian Taskforce on Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (2009) Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Rheumatol. 36, 478–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Borromeo G. L., Brand C., Clement J. G., McCullough M., Crighton L., Hepworth G., Wark J. D. (2014) A large case-control study reveals a positive association between bisphosphonate use and delayed dental healing and osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Bone Miner. Res. 29, 1363–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Iglesias J. E., Salum F. G., Figueiredo M. A., Cherubini K. (2013) Important aspects concerning alendronate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: a literature review. Gerodontology (2013) 10.1111/ger.12093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]