Background: UHRF1 is required for the maintenance of DNA methylation.

Results: UHRF1 interacts with topoisomerase II and regulates its localization to pericentric heterochromatin.

Conclusion: Topoisomerase II regulates the maintenance of DNA methylation.

Significance: Our study reveals a novel molecular mechanism of the maintenance of DNA methylation.

Keywords: DNA Demethylation, DNA Enzyme, DNA Methylation, DNA Methyltransferase, DNA Topoisomerase

Abstract

The maintenance of DNA methylation in nascent DNA is a critical event for numerous biological processes. Following DNA replication, DNMT1 is the key enzyme that strictly copies the methylation pattern from the parental strand to the nascent DNA. However, the mechanism underlying this highly specific event is not thoroughly understood. In this study, we identified topoisomerase IIα (TopoIIα) as a novel regulator of the maintenance DNA methylation. UHRF1, a protein important for global DNA methylation, interacts with TopoIIα and regulates its localization to hemimethylated DNA. TopoIIα decatenates the hemimethylated DNA following replication, which might facilitate the methylation of the nascent strand by DNMT1. Inhibiting this activity impairs DNA methylation at multiple genomic loci. We have uncovered a novel mechanism during the maintenance of DNA methylation.

Introduction

DNA methylation is an important epigenetic modification that plays a crucial role in multiple cellular processes, including transcriptional regulation, genomic imprinting, and X chromosome inactivation. Following replication, the nascent DNA strand strictly inherits the methylation pattern from the parental DNA to maintain DNA methylation the nascent DNA. In this cellular process, DNMT1 directly methylates the cytosine of the hemimethylated CpG dinucleotide pairs in the double-stranded DNA. Loss of DNMT1 in mice induces significant reduction of DNA methylation and leads to embryonic lethality (1). However, it is not fully clear how DNMT1 specifically recognizes and methylates hemimethylated DNA following replication. Besides DNMT1, recent studies have shown that UHRF1 is also required for the maintenance of DNA methylation following DNA replication. Similar to DNMT1 deficiency, depleting UHRF1 in mice induces global loss of DNA methylation and causes embryonic lethality (2, 3). Interestingly, DNMT1 fails to localize to heavily methylated pericentric heterochromatin (PCH)3 in Uhrf1 knock-out embryonic stem (ES) cells (2), suggesting that UHRF1 governs the localization and methyltransferase activity of DNMT1 in vivo.

How UHRF1 is recruited to chromatin it is relatively clear. UHRF1 recognizes H3K9me3 through its Tudor domain and plant homeodomain (PHD) (4–11) and binds hemimethylated DNA using its SET- and RING-associated (SRA) domain (12–14). In contrast, it is not clear how UHRF1 promotes the function of DNMT1. It has been proposed that UHRF1 physically interacts with DNMT1 and directly recruits DNMT1 to PCH (2). Recent studies suggests that UHRF1-dependent H3K23 ubiquitination indirectly recruits DNMT1 to PCH (15). However, structural and biochemical analyses have demonstrated that DNMT1 can recognize hemimethylated DNA through its own methyltransferase domain and is sufficient to catalyze DNA methylation independent of UHRF1 in vitro (16, 17), indicating that UHRF1 is not essential for directly facilitating the recognition of hemimethylated DNA by DNMT1. Recent studies have also shown that UHRF1 simulates DNMT1 methyltransferase activity in vitro (18, 19), but these observations could not fully explain the loss of DNMT1 localization at PCH in Uhrf1 knock-out ES cells.

The above studies suggest that UHRF1 might regulate the maintenance of DNA methylation through additional mechanisms. In this study, we report that UHRF1 interacts with topoisomerase IIα (TopoIIα) and regulates its chromatin localization. Inhibiting topoisomerase activities partially affects DNA methylation in vivo, suggesting that UHRF1 might regulates the maintenance of DNA methylation through TopoIIα.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies

The following polyclonal antibodies were raised in rabbit: human UHRF1 (amino acids (aa) 14–159), mouse UHRF1 (aa 1–141), human TopoIIα (aa 1173–1531), and mouse TopoIIα (aa 1170–1528). Anti-UHRF1 monoclonal antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-DNMT1 antibody was from Abcam. Antibodies against 5-methylcytosine, H3K9m2, and H3K9me3 were from Millipore. Anti-actin and anti-FLAG antibodies were from Sigma. Anti-HA antibody was from Covance.

Tandem Affinity Purification of UHRF1-interacting Proteins

Uhrf1 knock-out ES cells stably expressing S-protein/FLAG/streptavidin-binding protein (SFB)-tagged UHRF1 were generated. Cells were harvested from 50 10-cm2 plates and lysed with NTN300 buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mm NaCl, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40). The lysate was combined with the same volume of double-distilled H2O and streptavidin beads. After shaking the mixture at 4 °C for 2 h, the streptavidin beads were washed three times with NTN100 buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mm NaCl, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40). The bound proteins were eluted twice with saturating biotin solutions in NTN100 buffer. The eluents were combined and incubated with S-protein beads. After shaking the mixture at 4 °C for 2 h, the S-protein beads were washed three times and boiled with SDS sample loading buffer. The samples were briefly electrophoresed using 7.5% polyacrylamide gel, and the entire lane were excised and analyzed by mass spectrometry, which was performed by the Taplin Mass Spectrometry Facility at Harvard University.

Immunoprecipitation, Pulldown Assay, Western Blotting, and Dot Blotting

Cells were collected and lysed with NTN300 buffer. The lysate was combined with the same volume of double-distilled H2O. For immunoprecipitation, 1 μg of antibody and 40 μl of protein A beads were added. For pulldown assay, 1 μg of GST-tagged proteins on glutathione beads was added. After shaking the mixture at 4 °C for 2 h, the beads were precipitated and washed three times with NTN100 buffer. The beads were then boiled with SDS sample loading buffer. PAGE and Western blotting was performed according to standard procedures. For dot blotting, 200 ng of genomic DNA was serially diluted in 0.5 m NaOH and dotted on Zeta-Probe GT membranes (Bio-Rad). The membranes were air-dried for 1 h at room temperature, and dot blotting was performed according to standard procedures.

Recombinant Protein Expression

The GST-tagged UHRF1 Tudor domain (aa 109–308), PHD (aa 301–408), and Tudor + PHD domains (aa 109–408) were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells and purified using glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The beads were washed three times with NTN100 buffer and used for pulldown experiments.

Immunofluorescence Staining and Click Reaction

Immunofluorescence staining was performed according to standard procedures, expect that the fixed cells were incubated with 2 m HCl for 1 h at 37 °C and neutralized with 1 m Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) before staining with anti-5-methylcytosine antibody. To detect 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) by immunofluorescence and the Click reaction, cells were first fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde; permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100; and then incubated with 1× PBS solutions containing 10 mm sodium ascorbate, 2 mm copper sulfate, and 0.1 mm 6-carboxyfluorescein-triethylene glycol azide. The cells were washed 30 min later and stained with DAPI.

Southern Blotting

Genomic DNA was digested with HpaII, electrophoresed on 1% agarose gel, and transferred to Zeta-Probe GT membranes in 0.4 m NaOH. The membranes were neutralized with 2× SSC and hybridized with an oligonucleotide probe for minor satellite DNA in Rapid-hyb buffer (GE Healthcare) at 45 °C for 2 h. The membranes were washed twice with 2× SSC and 0.1% SDS and exposed overnight to a phosphor screen, which was then scanned using Typhoon 9400 (GE Healthcare). The sequence of the probe is 5′-ACTGAAAAACACATTCGTTGGAAACGGGATTTGTAGAACAGTGTATATCAATGAGTTACAATGA-3′.

Purification of Nascent DNA and Methylation Analysis

HeLa cells were synchronized at the G1/S boundary using a double thymidine block. Upon removal of thymidine, fresh medium with or without 2 μm ICRF-193 or 5 μm ICRF-187 was added. One hour later, EdU was added to the medium to a final concentration of 10 μm, and the cells were allowed to grow for another 2 h before they were collected by trypsinization. Genomic DNA was extracted using a ChargeSwitch genomic DNA mini tissue kit (Invitrogen) and biotinylated using the Click reaction by mixing the DNA into 1× PBS solutions containing 10 mm sodium ascorbate, 2 mm copper sulfate, and 0.1 mm biotin-triethylene glycol azide. The DNA was purified again 30 min later and fragmented into 300–800 bp by sonication. To obtain single-stranded DNA, the DNA was heated to 95 °C and quickly chilled on ice for 10 min. Biotinylated single-stranded DNA was purified by overnight incubation with streptavidin beads at 4 °C. The beads were thoroughly washed with NTN500 buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mm NaCl, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40) and washed twice briefly with 150 mm NaOH to remove any non-biotinylated parental strand. The beads was finally washed three times with 1× PBS and directly used for genomic PCR or bisulfite conversion with an EZ DNA Methylation-Gold kit (Zymo Research). Genomic regions for methylation analysis were amplified from bisulfite-converted DNA. For combined bisulfite restriction analysis (COBRA), the PCR fragments were digested with BstUI and electrophoresed on 10% TBE-native PAGE. For sequencing, the PCR fragments were ligated to pGEM-T (Promega) and transformed into E. coli. Fifteen individual colonies containing the insertions were sequenced.

RESULTS

UHRF1 Interacts with TopoIIα

To study the role of UHRF1 in the maintenance of DNA methylation, we generated Uhrf1 knock-out mice using gene-trap ES cell line RRZ054 (Fig. 1a). Consistent with previous reports (2, 3), Uhrf1 knock-out mice were embryonic lethal, and DNA methylation was significantly reduced in the Uhrf1 knock-out ES cells (Fig. 1, b–d), suggesting that UHRF1 is important for DNA methylation during early embryonic development. To examine the function and mechanism of UHRF1 in early embryonic development, we reconstituted Uhrf1 knock-out ES cells with SFB-tagged UHRF1 and performed tandem affinity purifications to search for the functional partner(s) of UHRF1 from the ES cell lysates. Surprisingly, we did not find any previously reported UHRF1 partners, such as DNMT1, DNMT3A/B, G9a, and USP7. Instead, TopoIIα was one of the most abundant proteins other than UHRF1 in our purification and mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. 2a). TopoIIα is an enzyme that resolves intertwined genomic DNA by transiently cutting and ligating double-stranded DNA (20, 21). To confirm the purification results, we performed reciprocal co-immunoprecipitations and observed a clear interaction between these two endogenous proteins (Fig. 2b). Moreover, we found that TopoIIα was significantly enriched at PCH and co-localized with UHRF1 and 5-methylcytosine (Fig. 2c), suggesting that TopoIIα is functionally linked with UHRF1 in the maintenance of DNA methylation. Besides TopoIIα, we also identified TopoIIβ in our purification (Fig. 2a). TopoIIβ is a homolog of TopoIIα that also resolves the intertwined DNA using the same mechanisms. Similar to TopoIIα, TopoIIβ also interacted with UHRF1 (Fig. 2d). TopoI is another important topoisomerase that disentangles DNA using a different mechanism by generating a single cut on the DNA. However, we could not detect an interaction between UHRF1 and TopoI (Fig. 2d). These results suggest that UHRF1 specifically interacts with TopoII.

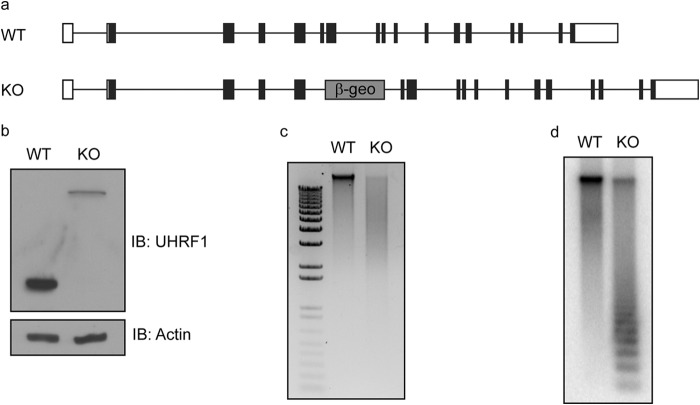

FIGURE 1.

UHRF1 knock-out ES cells have global loss of DNA methylation. a, exon structure of the mouse Uhrf1 gene is shown. β-geo represents the insertion of gene-trap vectors. b, cell lysates from WT and Uhrf1 knock-out (KO) ES cells were immunoblotted (IB) with anti-mouse UHRF1 antibody. The upper band represents the fusion product of the nonfunctional N terminus of UHRF1 and the β-geo cassette in the gene-trap vector. Actin was used as a loading control. c, genomics DNA from WT and Uhrf1 knock-out ES cells were digested with HpaII and separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. d, Southern blotting was performed using the gel in c, and the membrane was blotted using a minor satellite probe.

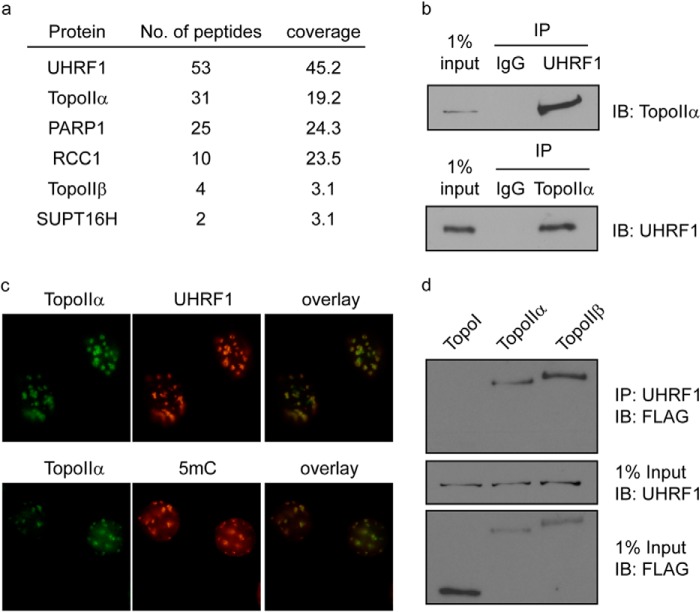

FIGURE 2.

UHRF1 interacts with TopoIIα. a, tandem affinity purification of SFB-tagged UHRF1 in ES cells was performed. Proteins identified by mass spectrometry are listed. b, co-immunoprecipitations (IP) between UHRF1 and TopoIIα in ES cells were performed using the antibodies indicated. Rabbit IgG was used as a control. c, MEF cells were stained with the antibodies indicated. d, 293T cells were transfected with SFB-tagged TopoI, TopoIIα, or TopoIIβ. Co-immunoprecipitations were performed using the antibodies indicated. IB, immunoblot.

UHRF1 Interacts with TopoIIα through its Tudor and PHD Domains

UHRF1 contains multiple domains, including the ubiquitin-like, tandem Tudor, PHD, SRA, and RING domains. To study which domain of UHRF1 is important for its interaction with TopoIIα, we generated several internal deletion mutants of UHRF1 to abolish each domain (Fig. 3a). Deletion of the ubiquitin-like, SRA, or RING domain did not affect the interaction with TopoIIα. However, deletion of either the tandem Tudor domains or the PHD drastically abolished the interaction (Fig. 3b), suggesting that the Tudor and PHD domains might cooperate to bind TopoIIα. To verify the interaction, we mutated key residues in both domains. Based on the domain structure analysis, Phe-165 in the aromatic cage of the first Tudor domain and Asp-347 and Glu-348 in the negatively charged surface groove of the PHD are important for their interactions with other proteins (4, 5). We mutated these residues, and co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed that the F165A mutant significantly impaired the interaction with TopoIIα and that the D347A/E348A double mutant largely abolished the binding to TopoIIα (Fig. 3c). To confirm these findings, we made recombinant proteins of the Tudor and PHD domains of UHRF1 and tested their ability to pull down TopoIIα. Although the Tudor domain alone weakly pulled down TopoIIα, the PHD strongly pulled down TopoIIα (Fig. 3d). When combining both the Tudor and PHD domains, the recombinant protein pulled down TopoIIα more robustly. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the Tudor and PHD domains of UHRF1 cooperatively bind TopoIIα.

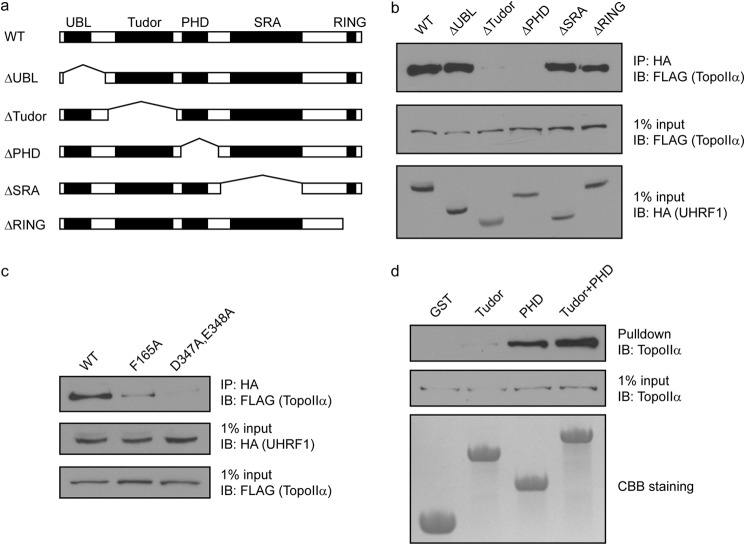

FIGURE 3.

UHRF1 interacts with TopoIIα through its Tudor and PHD domains. a, the domain structures of WT UHRF1 and each deletion mutant are shown. b, HA-tagged WT and deletion mutants of UHRF1 were cotransfected with SFB-TopoIIα into 293T cells. Co-immunoprecipitations (IP) were performed using the antibodies indicated. c, HA-tagged WT and point mutants of UHRF1 were cotransfected with SFB-TopoIIα into 293T cells. Co-immunoprecipitations were performed using the antibodies indicated. d, endogenous TopoIIα in 293T cells was pulled down using recombinant proteins of GST-tagged domains of UHRF1 as indicated and detected. UBL, ubiquitin-like domain; IB, immunoblot.

TopoIIα Interacts with UHRF1 through Two Regions

Next, we examined which region of TopoIIα interacts with UHRF1. TopoIIα is a large protein containing several enzymatic modules at the N terminus and a long stretch of unfolded region at the C terminus. We generated internal deletions of each of these enzymatic modules and the C-terminal unfolded region (Fig. 4a). Deletion of any of the first three enzymatic modules did not affect the binding to UHRF1. However, deletion of either the region containing the catalytic core or the C-terminal unfolded region abolished the interaction with UHRF1 (Fig. 4b). This result was further confirmed by pulldown experiments using recombinant proteins containing the Tudor and PHD domains of UHRF1 (Fig. 4c). Because UHRF1 recognizes TopoIIα through both the Tudor and PHD domains, it is possible that two separate regions in TopoIIα are recognized by the Tudor and PHD domains of UHRF1, respectively. The detailed binding mechanism of the UHRF1-TopoIIα complex could be revealed by future structural analysis.

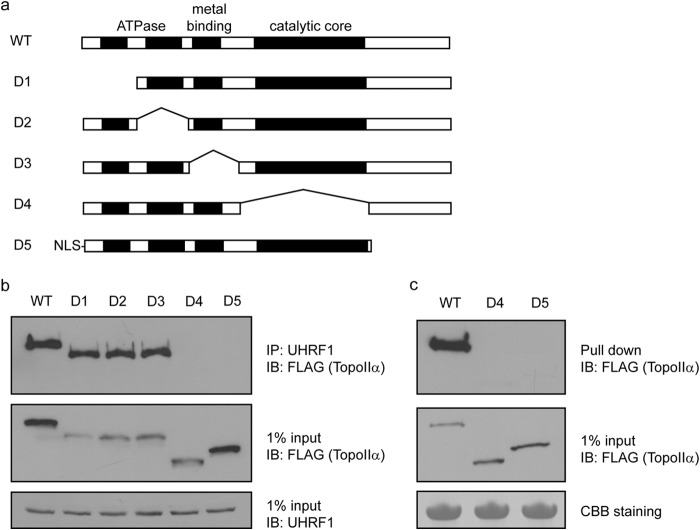

FIGURE 4.

TopoIIα interacts with UHRF1 using two domains. a, the domain structures of WT TopoIIα and each deletion mutant are shown. Nuclear localization sequences (NLS) were added to the D5 mutant because it has a deletion of the original nuclear localization sequence in TopoIIα. b, SFB-tagged WT and deletion mutants of TopoIIα were transfected into 293T cells. Co-immunoprecipitations (IP) were performed using the antibodies indicated. c, SFB-tagged WT and deletion mutants of TopoIIα were transfected into 293T cells. Pulldown assay was performed using recombinant proteins of GST-tagged Tudor and PHD domains of UHRF1. IB, immunoblot; CBB, Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

UHRF1 Regulates TopoIIα Localization at PCH

Because UHRF1 and TopoIIα co-localized at PCH, we examined if their interacting domains are required for their localization at PCH. Although UHRF1 mutants carrying the F165A or D347A/E348A mutation failed to interact with TopoIIα, these mutations did not significantly affect the localization of UHRF1 to PCH (Fig. 5a), suggesting that the interaction with TopoIIα is not essential for the recruitment of UHRF1 to PCH. In contrast, deletion of either the catalytic core (D4 mutant) or the C-terminal unfolded tail (D5 mutant) impaired the localization of TopoIIα at PCH (Fig. 5b), suggesting that the interaction with UHRF1 significantly contributes to TopoIIα localization at PCH. To confirm this observation, we tested whether depletion of UHRF1 has any effect on TopoIIα localization at PCH. In wild-type ES cells, the PCH foci of TopoIIα could be observed in ∼80% of the cells. In Uhrf1 knock-out ES cells, the percentage of TopoIIα-positive cells was reduced to ∼40% (Fig. 5c). To examine whether this phenomenon is specifically due to the absence of UHRF1, we reconstituted Uhrf1 knock-out ES cells with wild-type UHRF1 and the D347A/E348A mutant, which failed to interact with TopoIIα. Although both wild-type UHRF1 and the D347A/E348A mutant localized at PCH, only cells reconstituted with wild-type UHRF1 largely stored the PCH foci of TopoIIα (Fig. 5c). Collectively, these results suggest that UHRF1 is important for the localization of TopoIIα at PCH. Previous studies have shown that the Tudor and PHD domains of UHRF1 cooperatively bind H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 (22, 23). We first verified previous observations (22, 23) that H3K9me3, but not H3K9me2, is enriched at PCH (Fig. 6a). To determine whether H3K9me3 binding is critical for UHRF1 regulation of TopoIIα localization at PCH, we examined the localizations of these proteins in Suv39h1/Suv39h2 double-negative mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Although H3K9me3 was completely lost from PCH in Suv39h1/Suv39h2 double-negative MEFs (Fig. 6a), UHRF1 could be readily observed at PCH (Fig. 6b), which is likely through binding of hemimethylated DNA. Loss of H3K9me3 did not affect the localization of TopoIIα or DNMT1 or DNA methylation at PCH (Fig. 6, b–d), suggesting that UHRF1 regulation of TopoIIα localization is not through H3K9me3.

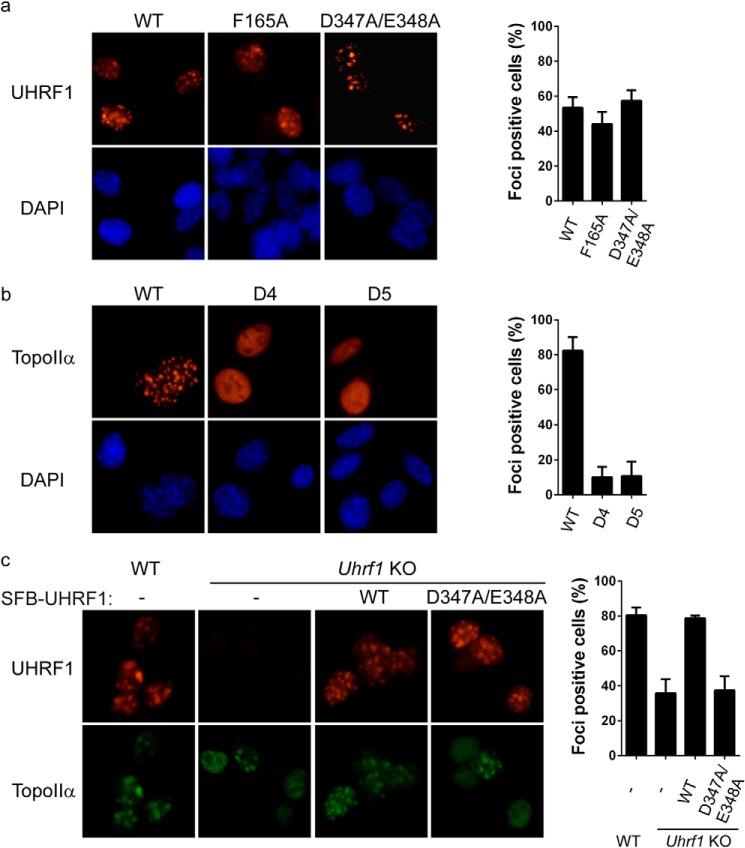

FIGURE 5.

UHRF1 regulates the localization of TopoIIα at PCH. a, SFB-tagged WT and point mutants of UHRF1 were electroporated into MEF cells, and their localizations were visualized by staining with anti-FLAG antibody. b, SFB-tagged WT and deletion mutants of TopoIIα were electroporated into MEF cells, and their localizations were visualized by staining with anti-FLAG antibody. c, the localizations of endogenous TopoIIα in the different ES cells indicated were visualized by staining with anti-TopoIIα antibody. Twenty-five cells were quantified for each experiment in a and b, and 100 cells were quantified for each experiment in c. Error bars represent the mean ± S.D. KO, knock-out.

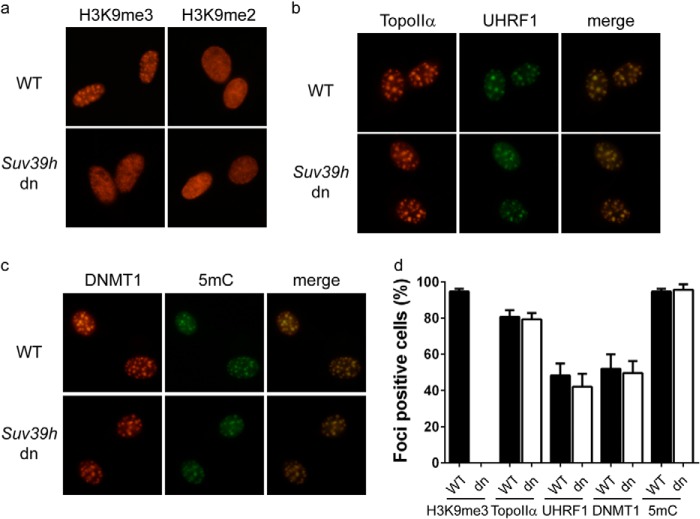

FIGURE 6.

UHRF1 does not regulate the localization of TopoIIα through H3K9me3 binding. a–d, the localizations of H3K9me3, TopoIIα, UHRF1, DNMT1, and 5-methylcytosine (5mC) in wild-type and Suv39h1/Suv39h2 double-negative (dn) MEF cells were visualized by staining with the antibodies indicated. The percentage of cells with PCH-staining foci (foci-positive cells) from three independent experiments is summarized. One-hundred cells were quantified for each experiment. Error bars represent the mean ± S.D.

TopoIIα Decatenation Activity Is Important for DNA Methylation

UHRF1 is critical for the maintenance of DNA methylation. Because UHRF1 interacts with TopoIIα and regulates its localization at PCH, where DNA is heavily methylated, we wondered if TopoIIα is also important for the maintenance of DNA methylation in vivo. We first analyzed the methylation status of Uhrf1 knock-out ES cells reconstituted with wild-type UHRF1 and its mutants F165A and D347A/E348A, which failed to interact with TopoIIα. Interestingly, neither UHRF1 mutant could rescue the DNA methylation in the way that wild-type UHRF1 did (Fig. 7a). Therefore, the interaction between UHRF1 and TopoIIα is important for the maintenance of DNA methylation.

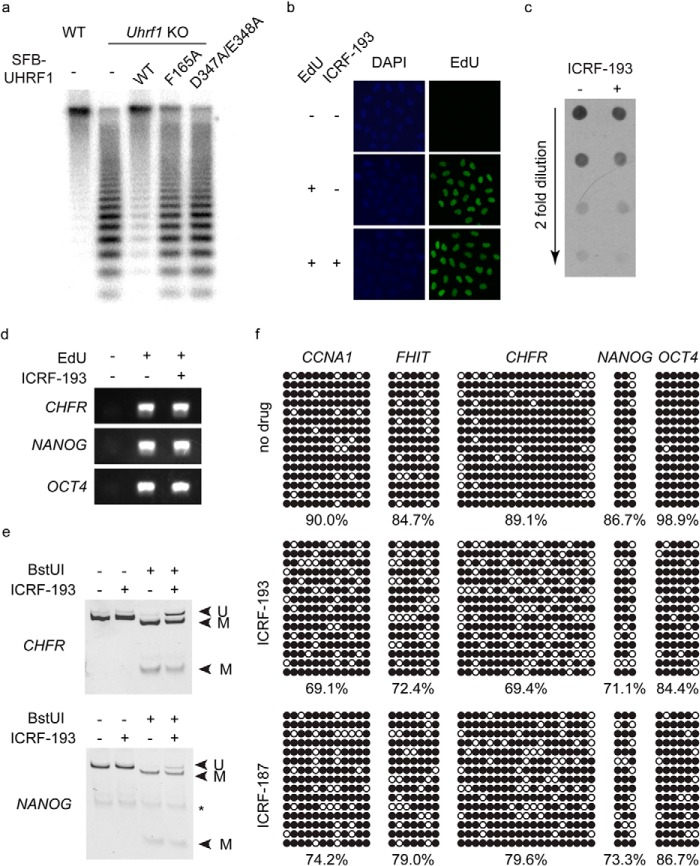

FIGURE 7.

TopoIIα regulates the maintenance of methylation. a, genomic DNAs from wild-type ES cells, Uhrf1 knock-out (KO) ES cells, and Uhrf1 knock-out ES cells reconstituted with SFB-tagged UHRF1 as indicated were digested with HpaII and separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Southern blotting was performed, and the membrane was blotted using a minor satellite probe. b, the Click reaction was used to detect EdU in HeLa cells treated as indicated. c, Dot blotting was performed using genomic DNA extracted from HeLa cells treated as indicated. The antibody against 5-methylated cytosine was used. d, nascent DNA was purified from HeLa cells treated as indicated. PCR was used to amplify three genomic locations as shown. e and f, bisulfite conversion was performed using the purified nascent DNA from HeLa cells treated with ICRF-193 or ICRF-187 as indicated, and PCR was used to amplify genomic loci for COBRA (e) and bisulfite sequencing analysis (f). In e, bands corresponding to methylated (M) and unmethylated (U) DNA are labeled. The asterisk indicates nonspecific PCR bands. In f, methylated and unmethylated cytosines are represented by black and white circles, respectively.

We further tested whether TopoIIα decatenation activity is important for the maintenance of DNA methylation. TopoIIα-null mice die before the 8-cell stage of embryogenesis (24), and no TopoIIα-null cells could be obtained and used for this study. Because TopoIIα is an enzyme known to resolve the precatenanes generated by the progression of replication forks (20, 21), we chose to suppress TopoIIα activity using TopoII inhibitors. Many TopoII inhibitors, such as etoposide and doxorubicin, suppress the DNA-rejoining step after strand passage during TopoII-mediated decatenation. However, prolonged treatment of these inhibitors will lead to massive double-stranded DNA breaks (25). Because the broken DNA is no longer catenated and might be methylated before or during the DNA repair process, these TopoII inhibitors are not ideal for studying the direct effect of TopoIIα inhibition on the maintenance of DNA methylation. Therefore, we used ICRF-193, a potent TopoII inhibitor that blocks the ATPase activity required for the release of TopoII after the DNA-rejoining step and prevents the turnover of TopoII without generating DNA breaks (25).

Because TopoIIα functions at multiple stages during the cell cycle and is particularly important for chromatin condensation and chromatid separation in G2 phase, inhibiting TopoIIα in vivo will lead to G2 arrest (20, 21). Thus, it is impossible to observe the long-term effect of ICRF-193 treatment. To observe the short-term effect of ICRF-193 on the maintenance of DNA methylation following partial DNA replication, cells were treated with ICRF-193 to suppress TopoIIα from the start of the synchronized DNA replication and harvested before G2 arrest. EdU was also added to the cell culture medium to label the nascent DNA. Although the G2 arrest caused by ICRF-193 treatment will lead to suppression of replication at highly methylated late replication regions (26), EdU could still be incorporated into the DNA when cells were harvested (Fig. 7b), suggesting that at least some early DNA replication was completed.

Dot blot analysis of genomic DNA revealed a mild decrease in global DNA methylation after ICRF-193 treatment (Fig. 7c). To accurately quantify the percentage decrease in DNA methylation, EdU-labeled nascent DNA was subsequently separated from the parental DNA (Fig. 7d) and subjected to DNA methylation analyses. Because the replication of highly methylated repetitive regions was suppressed due to ICRF-193 induced G2 arrest, we could not analyze the methylation status of these highly methylated repetitive regions. Instead, with early replicated nascent DNA, COBRA and bisulfite sequencing were used to analyze the methylation status of several genomic loci, including CCNA1, FHIT, CHFR, NANOG, and OCT4, which are known to be methylated in HeLa cells. Purified nascent DNA was amplified following bisulfite conversion, and COBRA showed that DNA methylation at the promoter regions of CHFR and NANOG was reduced by 15–20% (Fig. 7e). Bisulfite sequencing confirmed this result and revealed a similar reduction in DNA methylation at the promoter regions of CCNA1, FHIT, and distal enhancers of OCT4 (Fig. 7f). Similar results were obtained using another TopoII inhibitor, ICRF-187 (Fig. 7f). Because ICRF-193 and ICRF-187 block only the turnover of TopoIIα, it is likely that endogenous TopoIIα could still perform one round of decatenation before it is trapped and allow DNMT1-mediated DNA methylation at certain regions. This might be the reason that only a modest reduction in DNA methylation was observed in cells treated with ICRF-193 or ICRF-187. Nonetheless, these results suggest that TopoIIα decatenation activity is indeed important for proper maintenance of DNA methylation in vivo.

DISCUSSION

UHRF1 is required for the maintenance of DNA methylation globally. In mice, PCH could be clearly visualized as DAPI-dense regions, which are enriched for many repressive epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation (27). In Uhrf1 knock-out ES cells, DNMT1 localization at PCH was abolished, which clearly demonstrates that UHRF1 regulates DNA methylation through targeting DNMT1 to hemimethylated DNA. Several models have been proposed to explain how UHRF1 regulates DNMT1 localization. Based on the interaction between UHRF1 and DNMT1, it is believed that UHRF1 physically brings DNMT1 to hemimethylated DNA and passes the hemimethylated DNA by its SRA domain to DNMT1 (2, 3). However, this step seems unnecessary given the intrinsic hemimethylated DNA-binding ability of DNMT1 (16, 17). On the other hand, recent biochemical studies propose that the interaction stimulates DNMT1 activity through interacting and removing the block of the DNMT1 replication focus targeting sequence domain on its catalytic site (18, 19), but this interesting model could not fully account for the loss of DNMT1 from PCH in Uhrf1 knock-out cells. It is noteworthy that only a weak interaction between UHRF1 and DNMT1 could be detected in vivo (28). We did not identify DNMT1 as a major partner of UHRF1 in our unbiased purification. Therefore, it remains in question whether UHRF1 and DNMT1 work as a complex in vivo. An interaction-independent model has also been proposed. It has been shown that UHRF1 is important for ubiquitination of H3K23, which recruits DNMT1 through its replication focus targeting sequence domain (15). H3K23 ubiquitination is new modification that is not well characterized. Because methylated cytosine accounts for ∼5% of all cytosines, it remains to be determined whether the UHRF1-dependent H3K23 ubiquitination is abundant enough to cover all the methylated cytosines.

In this study, we reported a new mechanism by which UHRF1 regulates the maintenance of DNA methylation. We identified TopoIIα as a novel functional partner of UHRF1. UHRF1 regulates the PCH localization of TopoIIα, whose activity is important for the maintenance of DNA methylation. Precatenanes are formed after DNA replication fork progression, and TopoIIα is known to resolve DNA catenation (20, 21). Our results suggest that decatenation of hemimethylated DNA after DNA replication is required for efficient localization of DNMT1. DNMT1 is a processive enzyme (29). It is possible that hemimethylated catenated DNA is an unfavorable substrate of DNMT1 due to its impact on the processivity of DNMT1. Most studies of DNMT1 activities in vitro use short flexible hemimethylated DNA fragments as substrates, which cannot fully reflect the DNA topology in vivo. Further studies of DNMT1 activity are needed to determine whether this enzyme is sensitive to DNA topology.

The observation that UHRF1 regulates the PCH localization of TopoIIα is surprising because TopoIIα itself can resolve decatenated DNA in vitro without UHRF1. Coincident with our results, it has been shown that DNA methylation decreases the decatenation activity of TopoIIα (30), suggesting that TopoIIα might have difficulty in accessing heavily methylated regions, such as PCH. Because the SRA domain of UHRF1 recognizes hemimethylated DNA, its interaction with TopoIIα might facilitate the loading of TopoIIα to PCH and promotes its decatenation activity at PCH. It is noteworthy that UHRF1 is not absolutely required for TopoIIα localization at PCH, probably because other mechanisms also contribute to chromatin retention of TopoIIα (31).

UHRF1 interacts with TopoIIα through the Tudor and PHD regions, which have been shown to cooperatively bind H3K9me3 as well (4–11). This raises the concern that the functional interaction between UHRF1 and TopoIIα is mediated by H3K9me3. However, our data using Suv39h1/Suv39h2 double-negative MEFs show that depletion of H3K9me3 at PCH does not affect UHRF1 or TopoIIα localization there. Indeed, mutation of H3K9me3 and TopoIIα binding ability does not affect the localization of UHRF1 to PCH. This is likely because UHRF1 has an SRA domain that can recognize hemimethylated DNA in the absence of H3K9me3 and maintains DNA methylation at PCH. In agreement with these observations, it has been demonstrated that Suv39h1/Suv39h2 double-negative cells have only minor decreases in methylation of pericentric major satellite repeats, but have no impact on pericentric minor satellite repeats (32–34). Indeed, no significant change was observed for DNMT1 or 5-methylcytosine staining at PCH in Suv39h1/Suv39h2 double-negative MEFs. Therefore, UHRF1 regulates DNA methylation through TopoIIα, but not through H3K9me3. In addition, because histones are evicted from the DNA during the replication and are likely to be deposited after the completion of the nascent strand methylation (35), they are unlikely to regulate key events during the maintenance of DNA methylation.

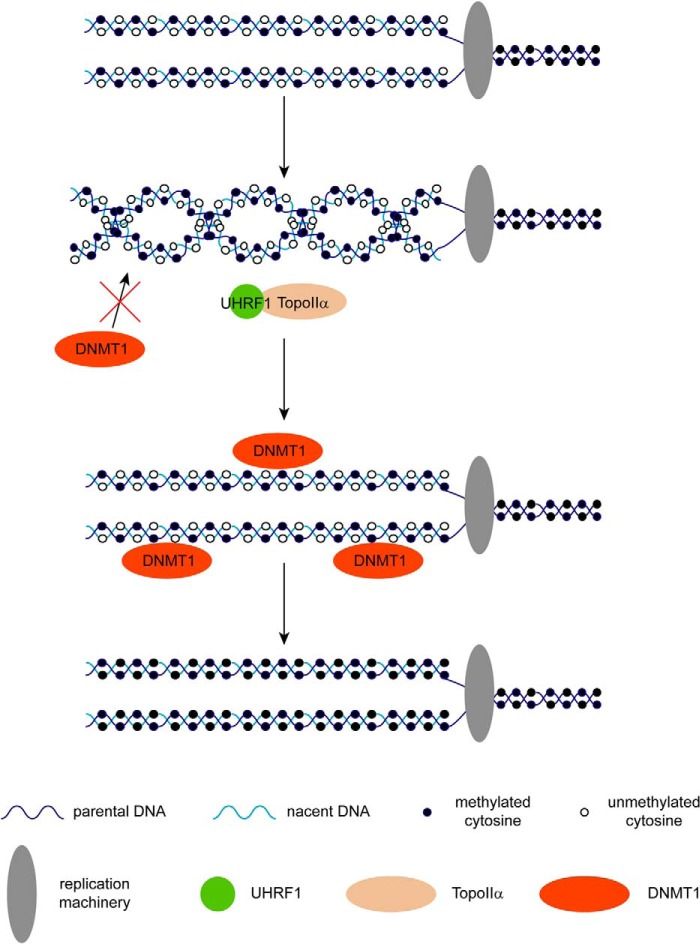

We propose a model in which UHRF1 facilitates TopoIIα to decatenate hemimethylated precatenanes following replication, which is likely to change the chromatin topology and promote DNMT1-dependent DNA methylation on the nascent DNA (Fig. 8). These findings not only provide a novel molecular mechanism for the maintenance of DNA methylation, but also uncover drug targets for diseases induced by abnormal DNMT1-dependent DNA methylation.

FIGURE 8.

Models of the UHRF1-TopoIIα complex for regulating the maintenance of DNA methylation. Precatenanes are formed after DNA replication fork progression, which impairs the access of DNMT1 to hemimethylated DNA. UHRF1 facilitates the access of TopoIIα to hemimethylated precatenanes. After decatenation of the precatenanes, DNMT1 can access the hemimethylated DNA and methylate the unmethylated cytosine.

Acknowledgment

We thank the University of Michigan Transgenic Core for blastocyst injection of ES cells.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA132755 and CA130899 (to X. Y.). This work was also supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Project 81471494 (to L.-Y. L.).

- PCH

- pericentric heterochromatin

- ES

- embryonic stem

- PHD

- plant homeodomain

- SRA

- SET- and RING-associated

- TopoIIα

- topoisomerase IIα

- aa

- amino acids

- SFB

- S-protein/FLAG/streptavidin-binding protein

- EdU

- 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine

- COBRA

- combined bisulfite restriction analysis

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast.

REFERENCES

- 1. Li E., Bestor T. H., Jaenisch R. (1992) Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell 69, 915–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bostick M., Kim J. K., Estève P. O., Clark A., Pradhan S., Jacobsen S. E. (2007) UHRF1 plays a role in maintaining DNA methylation in mammalian cells. Science 317, 1760–1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sharif J., Muto M., Takebayashi S., Suetake I., Iwamatsu A., Endo T. A., Shinga J., Mizutani-Koseki Y., Toyoda T., Okamura K., Tajima S., Mitsuya K., Okano M., Koseki H. (2007) The SRA protein Np95 mediates epigenetic inheritance by recruiting Dnmt1 to methylated DNA. Nature 450, 908–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nady N., Lemak A., Walker J. R., Avvakumov G. V., Kareta M. S., Achour M., Xue S., Duan S., Allali-Hassani A., Zuo X., Wang Y. X., Bronner C., Chédin F., Arrowsmith C. H., Dhe-Paganon S. (2011) Recognition of multivalent histone states associated with heterochromatin by UHRF1 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 24300–24311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rajakumara E., Wang Z., Ma H., Hu L., Chen H., Lin Y., Guo R., Wu F., Li H., Lan F., Shi Y. G., Xu Y., Patel D. J., Shi Y. (2011) PHD finger recognition of unmodified histone H3R2 links UHRF1 to regulation of euchromatic gene expression. Mol. Cell 43, 275–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang C., Shen J., Yang Z., Chen P., Zhao B., Hu W., Lan W., Tong X., Wu H., Li G., Cao C. (2011) Structural basis for site-specific reading of unmodified R2 of histone H3 tail by UHRF1 PHD finger. Cell Res. 21, 1379–1382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hu L., Li Z., Wang P., Lin Y., Xu Y. (2011) Crystal structure of PHD domain of UHRF1 and insights into recognition of unmodified histone H3 arginine residue 2. Cell Res. 21, 1374–1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xie S., Jakoncic J., Qian C. (2012) UHRF1 double Tudor domain and the adjacent PHD finger act together to recognize K9me3-containing histone H3 tail. J. Mol. Biol. 415, 318–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arita K., Isogai S., Oda T., Unoki M., Sugita K., Sekiyama N., Kuwata K., Hamamoto R., Tochio H., Sato M., Ariyoshi M., Shirakawa M. (2012) Recognition of modification status on a histone H3 tail by linked histone reader modules of the epigenetic regulator UHRF1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 12950–12955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheng J., Yang Y., Fang J., Xiao J., Zhu T., Chen F., Wang P., Li Z., Yang H., Xu Y. (2013) Structural insight into coordinated recognition of trimethylated histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3) by the plant homeodomain (PHD) and tandem Tudor domain (TTD) of UHRF1 (ubiquitin-like, containing PHD and RING finger domains, 1) protein. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 1329–1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rothbart S. B., Dickson B. M., Ong M. S., Krajewski K., Houliston S., Kireev D. B., Arrowsmith C. H., Strahl B. D. (2013) Multivalent histone engagement by the linked tandem Tudor and PHD domains of UHRF1 is required for the epigenetic inheritance of DNA methylation. Genes Dev. 27, 1288–1298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hashimoto H., Horton J. R., Zhang X., Bostick M., Jacobsen S. E., Cheng X. (2008) The SRA domain of UHRF1 flips 5-methylcytosine out of the DNA helix. Nature 455, 826–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Avvakumov G. V., Walker J. R., Xue S., Li Y., Duan S., Bronner C., Arrowsmith C. H., Dhe-Paganon S. (2008) Structural basis for recognition of hemi-methylated DNA by the SRA domain of human UHRF1. Nature 455, 822–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arita K., Ariyoshi M., Tochio H., Nakamura Y., Shirakawa M. (2008) Recognition of hemi-methylated DNA by the SRA protein UHRF1 by a base-flipping mechanism. Nature 455, 818–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nishiyama A., Yamaguchi L., Sharif J., Johmura Y., Kawamura T., Nakanishi K., Shimamura S., Arita K., Kodama T., Ishikawa F., Koseki H., Nakanishi M. (2013) Uhrf1-dependent H3K23 ubiquitylation couples maintenance DNA methylation and replication. Nature 502, 249–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bashtrykov P., Jankevicius G., Smarandache A., Jurkowska R. Z., Ragozin S., Jeltsch A. (2012) Specificity of Dnmt1 for methylation of hemimethylated CpG sites resides in its catalytic domain. Chem. Biol. 19, 572–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Song J., Teplova M., Ishibe-Murakami S., Patel D. J. (2012) Structure-based mechanistic insights into DNMT1-mediated maintenance DNA methylation. Science 335, 709–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berkyurek A. C., Suetake I., Arita K., Takeshita K., Nakagawa A., Shirakawa M., Tajima S. (2014) The DNA methyltransferase Dnmt1 directly interacts with the SET and RING finger-associated (SRA) domain of the multifunctional protein Uhrf1 to facilitate accession of the catalytic center to hemi-methylated DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 379–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bashtrykov P., Jankevicius G., Jurkowska R. Z., Ragozin S., Jeltsch A. (2014) The UHRF1 protein stimulates the activity and specificity of the maintenance DNA methyltransferase DNMT1 by an allosteric mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 4106–4115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nitiss J. L. (2009) DNA topoisomerase II and its growing repertoire of biological functions. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 327–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vos S. M., Tretter E. M., Schmidt B. H., Berger J. M. (2011) All tangled up: how cells direct, manage and exploit topoisomerase function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 827–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tachibana M., Sugimoto K., Nozaki M., Ueda J., Ohta T., Ohki M., Fukuda M., Takeda N., Niida H., Kato H., Shinkai Y. (2002) G9a histone methyltransferase plays a dominant role in euchromatic histone H3 lysine 9 methylation and is essential for early embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 16, 1779–1791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rice J. C., Briggs S. D., Ueberheide B., Barber C. M., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Shinkai Y., Allis C. D. (2003) Histone methyltransferases direct different degrees of methylation to define distinct chromatin domains. Mol. Cell 12, 1591–1598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Akimitsu N., Adachi N., Hirai H., Hossain M. S., Hamamoto H., Kobayashi M., Aratani Y., Koyama H., Sekimizu K. (2003) Enforced cytokinesis without complete nuclear division in embryonic cells depleting the activity of DNA topoisomerase IIα. Genes Cells 8, 393–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pommier Y., Leo E., Zhang H., Marchand C. (2010) DNA topoisomerases and their poisoning by anticancer and antibacterial drugs. Chem. Biol. 17, 421–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hiratani I., Takebayashi S., Lu J., Gilbert D. M. (2009) Replication timing and transcriptional control: beyond cause and effect–part II. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19, 142–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Almouzni G., Probst A. V. (2011) Heterochromatin maintenance and establishment: lessons from the mouse pericentromere. Nucleus 2, 332–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meilinger D., Fellinger K., Bultmann S., Rothbauer U., Bonapace I. M., Klinkert W. E., Spada F., Leonhardt H. (2009) Np95 interacts with de novo DNA methyltransferases, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b, and mediates epigenetic silencing of the viral CMV promoter in embryonic stem cells. EMBO Rep. 10, 1259–1264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vilkaitis G., Suetake I., Klimasauskas S., Tajima S. (2005) Processive methylation of hemimethylated CpG sites by mouse Dnmt1 DNA methyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 64–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boos G., Stopper H. (2001) DNA methylation influences the decatenation activity of topoisomerase II. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 28, 103–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lane A. B., Giménez-Abián J. F., Clarke D. J. (2013) A novel chromatin tether domain controls topoisomerase IIα dynamics and mitotic chromosome formation. J. Cell Biol. 203, 471–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lehnertz B., Ueda Y., Derijck A. A., Braunschweig U., Perez-Burgos L., Kubicek S., Chen T., Li E., Jenuwein T., Peters A. H. (2003) Suv39h-mediated histone H3 lysine 9 methylation directs DNA methylation to major satellite repeats at pericentric heterochromatin. Curr. Biol. 13, 1192–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Arand J., Spieler D., Karius T., Branco M. R., Meilinger D., Meissner A., Jenuwein T., Xu G., Leonhardt H., Wolf V., Walter J. (2012) In vivo control of CpG and non-CpG DNA methylation by DNA methyltransferases. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bulut-Karslioglu A., De La Rosa-Velázquez I. A., Ramirez F., Barenboim M., Onishi-Seebacher M., Arand J., Galán C., Winter G. E., Engist B., Gerle B., O'Sullivan R. J., Martens J. H., Walter J., Manke T., Lachner M., Jenuwein T. (2014) Suv39h-dependent H3K9me3 marks intact retrotransposons and silences LINE elements in mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell 55, 277–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Groth A., Rocha W., Verreault A., Almouzni G. (2007) Chromatin challenges during DNA replication and repair. Cell 128, 721–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]