This qualitative study explores the factors that hinder sympathetic and frank communication about the terminal nature of advanced cancer and reconstructs how physicians and nurses in oncology perceive their roles in preparing patients for end-of-life decisions. The findings suggest that oncologists recognized a risk of nourishing patients’ overly optimistic views in not talking openly and that it would be better to prepare patients proactively for decisions toward the end of life.

Keywords: Medical oncology, Medical ethics, Communication, Palliative care, End-of-life decisions

Abstract

Background.

Sympathetic and frank communication about the terminal nature of advanced cancer is important to improve patients’ prognostic understanding and, thereby, to allow for adjustment of treatment intensity to realistic goals; however, decisions against aggressive treatments are often made only when death is imminent. This qualitative study explores the factors that hinder such communication and reconstructs how physicians and nurses in oncology perceive their roles in preparing patients for end-of-life (EOL) decisions.

Methods.

Qualitative in-depth interviews were conducted with physicians (n = 12) and nurses (n = 6) working at the Department of Hematology/Oncology at the university hospital in Munich, Germany. The data were analyzed using grounded theory methodology and discussed from a medical ethics perspective.

Results.

Oncologists reported patients with unrealistic expectations to be a challenge for EOL communication that is especially prominent in comprehensive cancer centers. Oncologists responded to this challenge quite differently by either proactively trying to facilitate advanced care planning or passively leaving the initiative to address preferences for care at the EOL to the patient. A major impediment to the proactive approach was uncertainty about the right timing for EOL discussions and about the balancing the medical evidence against the physician’s own subjective emotional involvement and the patient’s wishes.

Conclusion.

These findings provide explanations of why EOL communication is often started rather late with cancer patients. For ethical reasons, a proactive stance should be promoted, and oncologists should take on the task of preparing patients for their last phase of life. To do this, more concrete guidance on when to initiate EOL communication is necessary to improve the quality of decision making for advanced cancer patients.

Implications for Practice:

Our findings suggest that oncologists recognized that they run a risk of nourishing patients’ overly optimistic views in not talking openly with them. It would be better to prepare the patient proactively for decisions toward the end of their disease trajectory and to accept one’s own emotional response not as a detractor from objective clinical reasoning but rather as source of true empathy and an important nonmedical factor in the decision-making process. The findings of this study call for better educational activity regarding communication skills and ethical concerns near the end of life and for dealing with oncologists’ emotional involvement.

Introduction

Communication with patients with incurable cancer about the transition from specific anticancer treatment to best supportive care often triggers ethical challenges around whether or how to address death explicitly [1] and implies talking about valuable goals for the last weeks or months of life. It also means dealing with patients’ feelings of hopelessness and disappointment. Although most physicians think that patients ideally should have a realistic understanding of their prognosis [2], the majority avoids prognosticating in the last phase of life. Studies showed that a “conspiracy of silence” leads to psychological distress [3], early palliative discussions are associated with less aggressive medical care near death, less anxiety and depression, earlier hospice referrals, and even a gain in lifetime [4–7]. In the end, palliative care can lower total health care cost [8]. Although some studies have assessed patient and caregiver preferences for end-of-life (EOL) communication [9, 10] and advanced directives [11], few qualitative studies have been carried out to explore physicians’ perceptions of the EOL decision-making process, as experienced by advanced cancer patients. Most studies focus on physicians’ attitudes and strategies toward truth telling and disclosure of prognosis [12, 13]. Much less is known about how physicians and nurses perceive their roles in preparing the patient and in the decision-making process toward the end of a disease trajectory. Data are also scarce with regard to the reasons for being reticent to address the palliative goals of care with the patient early on. This paper explores the factors that hinder patient involvement in decision making. We reconstruct how physicians and nurses perceive their roles in preparing patients for EOL decisions. Our work is part of a larger mixed-method ethics project on EOL decisions in hematology and oncology and is informed by a previous cohort study showing that patients often were not involved in decisions against aggressive treatment at the EOL [14].

Methods

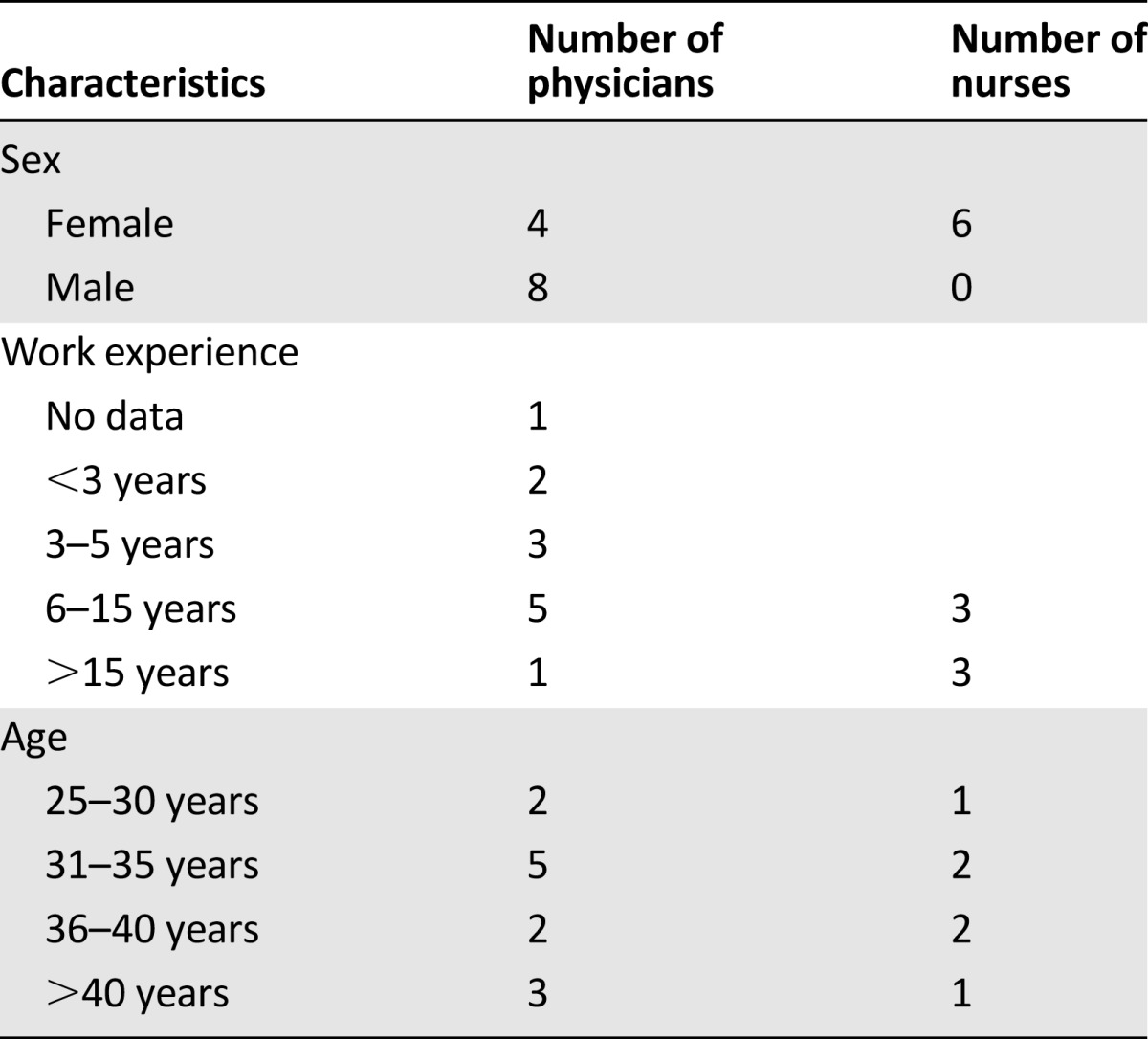

We conducted semistructured interviews with physicians (n = 12) and nurses (n = 6) working at the Department of Internal Medicine, which runs a comprehensive cancer center, at the University of Munich Medical Center in Germany (Table 1). Physicians (4 male and 8 female, aged 30–65 years) varied in work experience from 9 months to 16 years. Nurses were all female (aged 30–50 years) and had work experience of 12–20 years. A semistructured interview guide was developed based on research questions, fieldwork, and researchers’ experiences in addition to the existing literature. The interview guide was tested by an iterative review process with experts in the field of oncology and medical ethics and was approved by the research ethics committee. It included open-ended questions on EOL communication with patients and participants’ roles in influencing the decision-making process. One researcher (S.R.T.) with experience in qualitative research methods conducted all of the interviews. Interviews were audiotaped, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed according to the grounded theory principles using the data analysis software MAXQDA (VERBI GmbH, Berlin, Germany, http://www.maxqda.com). The grounded theory approach was applied because of the explorative nature of the study [15]. This approach entails an iterative process of coding all transcripts for major themes and patterns relevant to the research questions. In the first step of open coding, each line or paragraph of interview data was coded by the first author. Subsequently, the codes were used to generate categories and subcategories through the use of comparison analysis. That means that codes and categories develop through continuous comparison of the material. During axial coding, relationships were drawn among the categories against the entire body of interview data. A code is a meaningful label for the text that expresses the data contents, as understood by the researcher. Regular meetings of the interdisciplinary team, with expertise in oncology, social science, and medical ethics, provided a forum in which to discuss unclear data samples and to increase the discriminatory power for each category through constant comparisons. The analysis was also informed by the insights and normative analysis from a concomitant cohort study on EOL decision making in the same clinical setting [1, 14] and evaluated against the background of the current medical ethics discussion on EOL decision making.

Table 1.

Characteristics of interviewees (n = 18)

Results

Three major themes were identified throughout the interviews that determined communication with cancer patients concerning goals of care and limiting life–prolonging treatment toward the EOL: (a) patients’ unrealistic expectations as a challenge for addressing palliative goals of care, (b) nurses’ understanding of their roles in preparing the patient for EOL decisions, and (c) physicians’ balancing of objective medical evidence against their own subjective emotional involvement.

Patients’ Unrealistic Expectations as a Challenge for Addressing Palliative Goals of Care

Generally, physicians referred to the medical indication as a point of reference in the decision about whether to offer treatment to the patient. However, if the patient insisted on active treatment, physicians reported that they offered it, despite a lack of evidence of effectiveness. They explained their preference for active treatment in these cases with the goal of preserving the patient’s hope.

There simply are people for whom treatment always is connected to hope, and they just don’t want to let go. Even if one is not totally convinced there is much sense in it, you give in, just to not rob the patient’s courage to go on living. [Physician 11]

Physicians responded to patient preferences for active treatment although it had no or only marginal benefit, but sometimes severe side effects. This was the most frequent challenge reported by clinicians experiencing this dilemma.

This is difficult to endure, when you know that somebody will die but struggles on and fights because he/she clings to a hope which is probably 99% unrealistic. And to be in this dilemma, is for me the most difficult. [Physician 12]

Physicians explained patients’ unrealistic expectations as being beyond their control, as a “center effect” in which specialized cancer institutions attract patients who actively search for additional treatment.

Patients in continuous denial ... refuse to accept the truth, and they come here and believe in the ‘“name” of the institution, something will be done, a wonder drug will be available. Yes, they make it difficult for us because they still maintain their expectations despite all evidence to the contrary. [Physician 9]

In addition, physicians identified their own omissions that contribute to the unrealistic expectations and unreadiness of patients for advanced care planning. Oncologists admitted that they go along with or nourish patients’ overly optimistic views of the therapeutic options because they are afraid to destroy their patients’ hope. Nurses reported that oncologists’ communication with their patients was ambiguous at best and sometimes misleading because the physicians failed to adequately address the deterioration of the patient’s condition.

He often talks to the patients as if they had a cold. So, if this doesn’t work, we’ll just throw in two aspirins. [Nurse 6]

Physicians’ and Nurses’ Understanding of Their Roles in Preparing the Patient for EOL Decisions

We identified two tendencies for how interviewees understood their roles in preparing patients with advanced cancer for the last phase of their disease trajectory: one more proactive and the other more passive.

A Proactive Role and Strategies for Preparing Patients for Their Last Months of Life

Interviewees who described their roles in active terms aimed to facilitate the discussion with the patient about the right treatment choices at the EOL. This was stated to be a prerequisite for honest disclosure, minimizing unrealistic expectations and empowering patients for advance care planning.

One physician commented:

Finally, one must tell the patient the truth as soon as possible, and this has always been my opinion, so that they can plan accordingly. [Physician 10]

The interviewees described how they were able to structure the decision-making process in favor of sharing information and toward enhancing well-informed patient preferences for EOL care. Physicians and nurses with a more proactive approach described the various ways in which they supported their patients: by initiating the conversation about the worst case scenario early on, by promoting the coping process of the patient and his or her family, and by responding to the emotional needs of the patient.

A Passive Role and Dealing With EOL Situations

Interviewees who did not adopt the task of preparing patients described EOL discussions from a more passive standpoint.

I do not see myself as somebody who goes to the room and actively starts speaking of death; if the patient wants this, I would take this up. [Physician 4]

The passive attitude also became apparent in dealing with patients’ unrealistic expectations. Several physicians were unsatisfied with patients’ unrealistic expectations and unpreparedness for EOL decision making.

Certainly, with some patients, I would have wished that their facing death would have happened much earlier. This is what I identify as a deficit in our current situation. [Physician 5]

They did not consider themselves to be obliged to prepare the patient for the last phase of life. These interviewees reported that they waited until the patients themselves initiated a discussion about their prognosis or until a patient’s condition deteriorated further.

Sometimes … when people vigorously insist on being treated or getting everything, … then 2 days pass and naturally it is getting worse, … Then, the decision is being made by the patient’s family members or the patient. [Physician 4]

Several reasons could be identified for not discussing patients’ EOL preferences early on. As long as the patient feels quite well, despite poor prognosis, advanced care planning at that point is considered a “rather abstract problem.” Some physicians preferred that somebody else discuss EOL issues with the patient; they themselves did not feel well prepared to do it.

The physicians’ own understanding of their mandate in patient care influenced their attitudes. Two interviewees who defined their mandate in terms of curative rather than palliative care stated that something changed in their relationship with the patient when there were no therapeutic options left. At that point, they tended to avoid contact with these patients.

At this moment, when I have to tell the patient they will soon die …this is, in a way, already my closure of the relationship with this patient. From this moment on, the patient is basically already dead. [Physician 8]

In contrast, nurses tended to take a proactive role in such situations and preferred to be near the dying patient.

Well, it’s easiest for me when I am there. When I then say, umm, that went well. I think he died in peace and the family is able to get along with the situation, then it is easier for me, too. It is much harder to find out someone has died and I wasn’t there. [Nurse 3]

Balancing Medical Evidence Against the Physician’s Own Subjective Emotional Involvement

Physicians and nurses also differed in how they described emotions in the process of EOL care and decision making. Nurses described emotions as an important resource in caring for advanced cancer patients.

Somehow I feel drawn to these patients and I realize, I … well, yes, invest more time, if the patients are dying. [Nurse 2]

In contrast, physicians reported that they found themselves in an ambivalent situation. On the one hand, they said, medical evidence shaped the framework of their decision making; a positive benefit-harm ratio in the medical evaluation was often mentioned to be the key factor in the entire decision-making process. If the treatment preferred by the patient did not have sufficient prospects of success or was associated with strong side effects, several oncologists referred to their conscience to justify not following the patient’s preference for active treatment. On the other hand, one physician felt subjectively influenced by patients and their respective situations.

Often, because much is based on emotions, one needs to be careful not to get carried away with subjective thinking. But we do try as much as possible to decide on this objectively. [Physician 5]

Physicians described their difficulty in reconciling the need for objective or evidence-based decision-making criteria with their own emotional involvement. Consequently, decision making within a team was viewed as fundamental for reaching emotional distance, especially when making a decision against life-prolonging treatment.

I think one should not be guided by subjective feelings at all, but should anyhow try to decide objectively and … that we, when it affects the therapy limitation, should decide as a team. [Physician 10]

Discussion

This study identified patients with unrealistic expectations and hopes for cure as a major challenge for oncologists when introducing palliative goals of care. This finding is supported by the results of a antecedent cohort study on EOL decisions that showed that patients in denial were involved significantly less often than patients with an appropriate perception of their situation in decisions against life-prolonging treatment [14]. The results of this study provide insight about the reasons for and reactions toward unrealistic patient expectations on the part of physicians and nurses. Several studies report the physicians’ discomfort discussing prognosis [13, 16] for the same reasons that were given by our interviewees: feeling ill prepared for EOL communication, uncertainty about the definite prognosis, and fear of destroying patients’ hopes. It might well be that the old doctrine established by 19th century physician-teachers like von Hufeland still continues to influence decision making. He posited that a physician should never talk with a patient about death to maintain hope [17]. However, our results support the view that it is ethically critical to elicit patient preferences and, at the same time, tell the truth about the patient’s prognosis. Prerequisites for achieving this goal are communication skills and an active stance: communications skills are not necessarily acquired over time and with more clinical experience, but they can be trained successfully [3, 18, 19]. The right attitude is more a result of ethical training in weighing patients’ values and treatment options as part of professional development, and its impact needs more attention.

Patients’ misunderstanding of their terminal illness and prognosis is not unique to cancer centers [20, 21]. Still, the emphasis on patients’ unrealistic expectations as the major challenge for communication proved especially strong in our study. Interviewees explained this phenomenon as the effect of a comprehensive cancer center that attracts patients who had been told elsewhere that all standard treatments were exhausted. Hence, the patients’ initial selection of the center most likely was brought about by their unrealistic expectations. This study found that these unrealistic expectations are a challenge creating a prominent ethical dilemma that has not been described before in the literature for specialized centers.

Although all oncologists seemed equally confronted by the unrealistic expectations of their patients, they responded to it quite differently. About one-third of the physicians adopted the task of proactively preparing their patients for EOL decisions and fostering their coping process. Recent research has demonstrated that the majority of patients and their family members prefer to get the opportunity to be informed early on about the anticipated course of the disease to evaluate the situation, assign priorities and preferences, and possibly use palliative support earlier [22, 23]. Knowledge about the last phase of life is not associated with more anxiety but rather with better orchestration of care at the EOL [24]. Moreover, early palliative care with communication about goals of care facilitates an accurate prognostic understanding of the disease [7]. Such an understanding can allow patients to forgo aggressive therapy toward the EOL, not only improving patients’ quality of life but also resulting in longer survival by sparing patients toxic therapy [6]. Consequently, the proactive attitude favored by a number of physicians and nurses is supported by clinical and patient-oriented evidence. From an ethical perspective, the evidence supports patients’ being able to make better decisions regarding their preferences. That, in turn, accounts for respecting patients’ autonomy and preventing harm through interventions that may not be consistent with patients’ authentic values. However, not all physicians preferred pursuing a proactive approach. This finding is in line with data showing that oncologists are overwhelmingly reluctant to provide patients with prognostic information and are hesitant to prepare patients for dying and death [24, 25]. These physicians wait until patients or their relatives initiate discussions about prognosis or until the situation of the patient worsens and no more therapeutic options are left [4, 26]. This attitude used to be accepted as ethically justified by the Corpus Hippocraticum, in which the physician is told not to go and see dying patients [27]. Today, honesty and empathy, especially at the EOL, should prevail in the therapeutic relationship. As a result of the “honesty deficit” at the EOL, increasing numbers of patients with advanced cancer receive chemotherapy close to death [28] and are referred too late to palliative care settings [29]. As indicated by our interviewees and in the literature, reasons for being reluctant include uncertainty about accurate prognostication in the individual patient and fear of negative emotions or destroying hope prematurely. Additional reasons identified by our study were the uncertainty about defining the right point in time to initiate EOL discussion and uncertainty about who is responsible for initiating it. This uncertainty indicates a need for more concrete recommendations for oncologists about their role in integrating palliative care communication and about the optimal time to initiate and address such discussions. The roles of nurses, psycho-oncologists, and clinical ethicists should be considered because oncologists are reluctant to accept responsibility for EOL conversations [30]. Furthermore, clinical ethics consultation often can be helpful in structuring and balancing medical, ethical, and psychosocial factors and generating consensus about the right way to make decisions. It is significant that nurses seemed to have less difficulty taking a proactive stance and reported positive emotions when being close to the patient in the last phase of life.

Because nurses tend to have more open and unforced communication with patients, they could play an important role in understanding patients’ preferences. Although we acknowledge the role of nurses as facilitators for preparing EOL discussions, we also have to take into account that this communication is at the core of the physician-patient relationship and should not be outsourced. Physicians had more reservations toward emotions mainly because they view emotions as a detractor from objective clinical reasoning or because of their clinical distance or stance of professional detachment [31]. Such detachment has long been propagated as a necessary condition for medical practice [32]; however, others have shown that cognitive expertise and emotional response complement each other [33]. In the era of evidence-based medicine, which emphasizes data and objective reasoning, we might need to focus more on how to bring together clinical reasoning and an emotional, empathic response to patient needs. With respect to limitations, this study reflects the attitudes and perceptions of physicians and nurses working at one German university hospital in an urban setting. In order to generalize these findings further, broad, quantitative, and complementary qualitative research involving other hospitals and geographic settings is required.

Conclusion

Oncologists respond to the challenge of preparing patients for the last phase of life quite differently: some adopt a proactively approach, whereas others take a passive stance. Three major impediments to the proactive approach were identified: uncertainty about the right timing for initiating EOL discussions; uncertainty about who is responsible for initiating discussions; and uncertainty about balancing objective evidence, patient wishes, and one’s subjective judgment. Our findings indicate that oncologists could prepare patients more appropriately and ethically for the last phase of life if they recognize that they run the risk of nourishing patients’ overly optimistic views in not talking openly with them rather than taking on the task of proactively preparing the patient . Such oncologists should accept their empathic response, their own emotional response, not as an detractor from objective clinical reasoning but rather as an obligatory ethical response for appropriate end-of-life decision making. With more research, concrete recommendations for the optimal time to initiate and address such discussions would be helpful, as indicated by our findings.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by German Research Foundation Grants HI 701/6-1, HI 701/6-2, RE 701/4-1, RE 701/4-2, and RE701/4-3.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: Please see the related commentary, “Toward Eubiosia: Bridging Oncology and Palliative Care,” by Don S. Dizon, on page 5 of this issue.

For Further Reading: David Hui, Sun-Hyun Kim, Jung Hye Kwon et al. Access to Palliative Care Among Patients Treated at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. The Oncologist 2012;17:1574–1580.

Abstract:

Background. Palliative care (PC) is a critical component of comprehensive cancer care. Previous studies on PC access have mostly examined the timing of PC referral. The proportion of patients who actually receive PC is unclear. We determined the proportion of cancer patients who received PC at our comprehensive cancer center and the predictors of PC referral.

Methods. We reviewed the charts of consecutive patients with advanced cancer from the Houston region seen at MD Anderson Cancer Center who died between September 2009 and February 2010. We compared patients who received PC services with those who did not receive PC services before death.

Results. In total, 366 of 816 (45%) decedents had a PC consultation. The median interval between PC consultation and death was 1.4 months (interquartile range, 0.5–4.2 months) and the median number of medical team encounters before PC was 20 (interquartile range, 6–45). On multivariate analysis, older age, being married, and specific cancer types (gynecologic, lung, and head and neck) were significantly associated with a PC referral. Patients with hematologic malignancies had significantly fewer PC referrals (33%), the longest interval between an advanced cancer diagnosis and PC consultation (median, 16 months), the shortest interval between PC consultation and death (median, 0.4 months), and one of the largest numbers of medical team encounters (median, 38) before PC.

Conclusions. We found that a majority of cancer patients at our cancer center did not access PC before they died. PC referral occurs late in the disease process with many missed opportunities for referral.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Stella Reiter-Theil, Wolfgang Hiddemann, Eva C. Winkler

Provision of study material or patients: Wolfgang Hiddemann

Collection and/or assembly of data: Timo A. Pfeil, Stella Reiter-Theil

Data analysis and interpretation: Timo A. Pfeil, Katsiaryna Laryionava, Stella Reiter-Theil, Eva C. Winkler

Manuscript writing: Timo A. Pfeil, Katsiaryna Laryionava, Stella Reiter-Theil, Eva C. Winkler

Final approval of manuscript: Timo A. Pfeil, Katsiaryna Laryionava, Stella Reiter-Theil, Wolfgang Hiddemann, Eva C. Winkler

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Reiter-Theil S. What does empirical research contribute to medical ethics? A methodological discussion using exemplary studies. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2012;21:425–435. doi: 10.1017/S0963180112000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, et al. Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2007;21:507–517. doi: 10.1177/0269216307080823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA, Beveridge HA. Truth may hurt but deceit hurts more: Communication in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2002;16:297–303. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm575oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319–2326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: A randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:180–190. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogg L, Aasland OG, Graugaard PK, et al. Direct communication, the unquestionable ideal? Oncologists’ accounts of communication of bleak prognoses. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1221–1228. doi: 10.1002/pon.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, et al. Communicating with realism and hope: Incurable cancer patients’ views on the disclosure of prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1278–1288. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrison RS, Morrison EW, Glickman DF. Physician reluctance to discuss advance directives. An empiric investigation of potential barriers. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2311–2318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH. When and how to initiate discussion about prognosis and end-of-life issues with terminally ill patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:132–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon EJ, Daugherty CK. ‘Hitting you over the head’: Oncologists’ disclosure of prognosis to advanced cancer patients. Bioethics. 2003;17:142–168. doi: 10.1111/1467-8519.00330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winkler EC, Reiter-Theil S, Lange-Riess D, et al. Patient involvement in decisions to limit treatment: The crucial role of agreement between physician and patient. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2225–2230. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.9515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Grounded Theory in Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenherr G, Meyer-Zehnder B, Kressig RW, et al. To speak, or not to speak — do clinicians speak about dying and death with geriatric patients at the end of life? Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13563. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Hufeland CW. Die Verhältnisse des Arztes. Journal der practischen Arzneykunde und Wundarzneykunst. 1806:5–36. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, et al. Efficacy of a Cancer Research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:650–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07810-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balaban RB. A physician’s guide to talking about end-of-life care. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:195–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.07228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gattellari M, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, et al. Misunderstanding in cancer patients: Why shoot the messenger? Ann Oncol. 1999;10:39–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1008336415362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279:1709–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Preparing for the end of life: Preferences of patients, families, physicians, and other care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:727–737. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parikh RB, Kirch RA, Smith TJ, et al. Early specialty palliative care—translating data in oncology into practice. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2347–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1305469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundquist G, Rasmussen BH, Axelsson B. Information of imminent death or not: Does it make a difference? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3927–3931. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.6247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Prognostic disclosure to patients with cancer near the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1096–1105. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-12-200106190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers SO, Jr, et al. Physician factors associated with discussions about end-of-life care. Cancer. 2010;116:998–1006. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones WHS, Withington ET. Hippocrates. Vol 2. London, U.K.: Heinemann, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baszanger I. One more chemo or one too many? Defining the limits of treatment and innovation in medical oncology. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:864–872. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaertner J, Wolf J, Voltz R. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:357–362. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328352ea20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD, et al. Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1166–1172. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coulehan JL. Tenderness and steadiness: Emotions in medical practice. Lit Med. 1995;14:222–236. doi: 10.1353/lm.1995.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blumgart HL. Caring for the patient. N Engl J Med. 1964;270:449–456. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196402272700906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Freitas J, Haque OS, Gopal AA, et al. Response: Clinical wisdom and evidence-based medicine are complementary. J Clin Ethics. 2012;23:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]