A systematic review to identify articles addressing the clinical, educational, research, and administrative indicators of integration was performed. This review highlighted 38 clinical, educational, research, and administrative indicators that with further refinement may facilitate assessment of the level of integration of oncology and palliative care.

Keywords: Access, Health systems, Indicators, Integration, Neoplasms, Palliative care, Referral

Abstract

Background.

Both the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the European Society for Medical Oncology strongly endorse integrating oncology and palliative care (PC); however, a global consensus on what constitutes integration is currently lacking. To better understand what integration entails, we conducted a systematic review to identify articles addressing the clinical, educational, research, and administrative indicators of integration.

Materials and Methods.

We searched Ovid MEDLINE and Ovid EMBase between 1948 and 2013. Two researchers independently reviewed each citation for inclusion and extracted the indicators related to integration. The inter-rater agreement was high (κ = 0.96, p < .001).

Results.

Of the 431 publications in our initial search, 101 were included. A majority were review articles (58%) published in oncology journals (59%) and in or after 2010 (64%, p < .001). A total of 55 articles (54%), 33 articles (32%), 24 articles (24%), and 14 articles (14%) discussed the role of outpatient clinics, community-based care, PC units, and inpatient consultation teams in integration, respectively. Process indicators of integration include interdisciplinary PC teams (n = 72), simultaneous care approach (n = 71), routine symptom screening (n = 25), PC guidelines (n = 33), care pathways (n = 11), and combined tumor boards (n = 10). A total of 66 articles (65%) mentioned early involvement of PC, 18 (18%) provided a specific timing, and 28 (28%) discussed referral criteria. A total of 45 articles (45%), 20 articles (20%), and 66 articles (65%) discussed 8, 4, and 9 indicators related to the educational, research, and administrative aspects of integration, respectively.

Conclusion.

Integration was a heterogeneously defined concept. Our systematic review highlighted 38 clinical, educational, research, and administrative indicators. With further refinement, these indicators may facilitate assessment of the level of integration of oncology and PC.

Implications for Practice:

This systematic review identified 38 indicators of integration of oncology and palliative care (PC). On further validation, these indicators may facilitate benchmarking, prioritization, quality improvement, and accountability. Specifically, these indicators may facilitate (a) referring physicians, patients, and caregivers to identify the centers that offer a high level of access to PC services; (b) policy makers and administrators to benchmark their level of integration nationally and internationally, standardize their services, and allocate appropriate resources toward quality improvement; (c) organizations to provide special designations based on the level of integration; and (d) researchers to examine how the extent of integration is associated with various health care outcomes.

Introduction

Patients with advanced cancer often experience multiple physical and psychological symptoms, and have significant communication and decision-making needs throughout the disease trajectory [1]. Palliative care (PC) is an interprofessional discipline aimed at addressing the supportive care needs in patients with advanced cancer and their families [2]. Multiple studies have demonstrated improved outcomes associated with PC, such as improvements in physical and psychosocial symptoms, quality of life, quality of end-of-life care, satisfaction, costs of care, and even survival [3–6]. Over the last few years, there has been an increasing call for integration of palliative care and oncology by various organizations, including the Institute of Medicine, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO), and the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer [7–10].

Although many organizations support integration, this remains an abstract and complex concept that is poorly defined. The ESMO has put forth a list of 13 criteria for the incentive program of “EMSO designated centers of integrated oncology and palliative care” [10]. However, a global consensus on indicators of integration is currently lacking. To better understand what integration entails, we conducted a systematic review to identify the clinical, educational, research, and administrative indicators of integration in the published literature. These indicators would help us to better understand the concept of integration and may allow clinicians, patients, researchers, hospital administrators, and policy makers to better assess the level of integration of oncology and palliative care. Specifically, these indicators may facilitate (a) referring physicians, patients, and caregivers to identify the centers that offer a high level of access to palliative care services; (b) policy makers and administrators to benchmark their level of integration nationally and internationally, standardize their services, and allocate appropriate resources toward quality improvement; (c) organizations to provide special designations based on the level of integration; and (d) researchers to examine how the extent of integration is associated with various health care outcomes.

Methods

Literature Search

The institutional review board at MD Anderson Cancer Center provided approval to proceed without the need for full committee review. On December 18, 2013, our clinical librarian searched all the citations on Ovid MEDLINE PubMed and Ovid EMBase from 1947 to 2013. Our search strategy consisted of Medical Subject Headings and text word or text phrase for (a) “palliative care” or “palliative medicine” or “palliative therapy” or “supportive care”; (b) “neoplas$” or “cancer$” or “tumor$” or “tumour$”; and (c) “integration$” or “integrate” or “integrated” or “integrating.” Original studies, reviews, systematic reviews, guidelines, editorials, commentaries, and letters were all included. Non-English articles, dissertations, and conference abstracts were excluded. Duplicates were removed.

After the initial search, two investigators (D.H., Y.J.K.) independently reviewed the title and abstract of each citation for inclusion. Publications were included for further review if either of the two investigators coded that the article was related to integration of oncology and palliative care. This approach was taken to maximize inclusion. The inter-rater agreement was high (κ = 0.96, p < .001).

Data Collection

We retrieved the full manuscript of articles of interest and excluded any publications not relevant to integration of oncology and palliative care. Subsequently, four oncologists with training in palliative care examined each article in detail and identified themes and concepts related to integration. One investigator reviewed all articles for consistency (D.H.), and the other three investigators (Y.J.K., J.C.P., Y.Z.) each examined one third of the articles. Any disagreements were discussed to arrive at a consensus. The indicators of integration were classified on the basis of predefined categories: clinical, education, research, and administration. Clinical indicators were further divided under structure, process, and outcomes under the Donabedian framework [11]. Although many clinical outcomes were mentioned in the literature (e.g., survival, quality of life, quality of end-of-life care), it could not be determined whether these outcomes were related to the mere presence of a palliative care program, successful integration specifically, or other cointerventions (i.e., cancer treatments). Thus, this systematic review focused only on the structure and processes of integration. This qualitative systematic review follows the PRISMA guideline for reporting where applicable [12].

Statistical Analysis

We used frequencies and percentages to summarize the data. The Statistical Analysis System (SAS version 9.2, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) was used to examine the trends in the number of articles over time using linear regression with square root transformation. A p value of <.05 was considered significant.

Results

Literature Search

Figure 1 outlines the literature search. We initially identified 1,098 citations. After removal of duplicates, non-English articles, and conference abstracts, a total of 431 citations (39%) were available for further review. On examination of the abstracts and subsequently the full article, 101 articles (23%) were included in the final sample.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

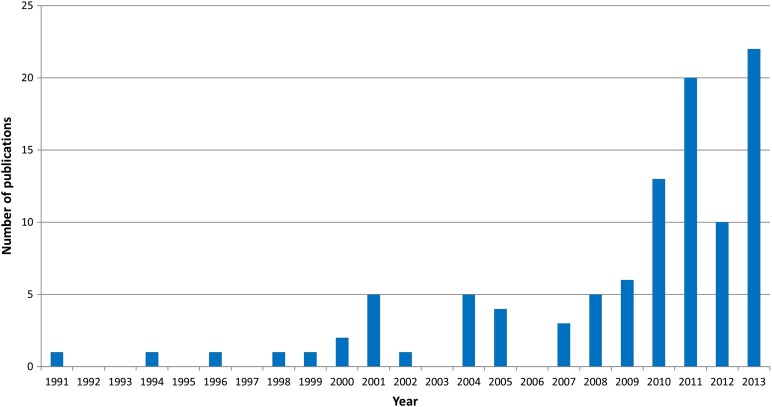

Table 1 shows the study characteristics. A majority of these articles were review articles (n = 59, 58%), published in oncology journals (n = 60, 59%), and from North America (n = 64, 63%). The number of articles on integration increased significantly between 1991 and 2013 (p < .001, linear regression temporal trends) (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Publication characteristics (n = 101)

Figure 2.

Increasing number of publications on integration of oncology and palliative care between 1999 and 2013 (p < .001). A total of 65 articles (64%) were published in 2010 or after.

Indicators of Integration Related to the Structures and Processes of Clinical Palliative Care Programs

Among the 101 articles, 55 (54%) discussed the role of outpatient palliative care clinics in integration, 33 (32%) mentioned community-based palliative care, 24 (24%) described the impact of palliative care units, and 14 (14%) included inpatient consultation teams (Table 2; supplemental online Table 1).

Table 2.

Thirty-eight indicators of integration of oncology and palliative care

Almost all articles (n = 96, 95%) addressed various processes for integration (Table 2; supplemental online Table 1). From the palliative care perspective, having interdisciplinary teams (n = 72), acceptance of patients on active cancer treatments (i.e., simultaneous care, n = 71), and a high degree of availability of a palliative care clinic (i.e., days/hours of operation) (n = 10) represent potential indicators.

From the oncology perspective, routine symptom screening (n = 25) may support integration. Although 66 articles (65%) mentioned early involvement of palliative care is important, only 18 (18%) provided specific recommendations for the timing of palliative care referral (Table 3; supplemental online Table 2).

Table 3.

Proposed timing of palliative care referral (n = 18)

Several process indicators are related to increased collaborations between palliative care and oncology teams. These include adoption of supportive and palliative care guidelines (n = 33); presence of criteria for palliative care referral (n = 28); communication, cooperation, and coordination between the two teams (n = 18); use of supportive care pathways (n = 11); involvement of palliative care in multidisciplinary patient care conference (n = 10); having palliative care service embedded in oncology clinics (n = 10); or introduction of a palliative care nurse practitioner (n = 12).

Indicators of Integration Related to Education

A total of 45 articles (45%) addressed educational strategies for integration (Table 2, supplemental online Table 3). Among these articles, 34 (34%) specifically stated that oncologists should have a basic palliative care competence. Of note, 17 articles (17%) discussed that palliative care should be introduced early into the undergraduate curriculum, and 7 articles (7%) emphasized the importance of oncology fellows rotating through palliative care. Continuing medical education for practicing oncology professionals also was discussed (n = 6, 6%).

A total of 22 articles (22%) mentioned the role of lectures and curriculums for oncology professionals on various aspects of palliative care, such as symptom control, communication, prognostication, and end-of-life care. Specific palliative care training programs identified in this systematic review include the ASCO Optimizing Cancer Care: The Importance of Symptom Management, Advocating for Clinical Excellence, the Care for Life-threatening Illnesses program, Disseminating End-of-life Education to Cancer Centers, the End-of-Life-Nursing Education Curriculum, the Education for Physicians on End-of-Life Care (EPEC) curriculum, EPEC-Oncology, the Initiative for Pediatric Palliative Care, Hospice and Palliative Care Evaluation, the Harvard Medical School Palliative Care Education and Practice curriculum, the Palliative Care Emphasis Program on Symptom Management and Assessment for Continuous Medical Education project (PEACE), and the Supportive Care Resource Kit Training Workshop. Conferences on PC also were mentioned as additional education opportunities (n = 6, 6%).

Indicators of Integration Related to Research

A total of 20 articles (20%) endorsed the need for research in integration. As shown in Table 2 and supplemental online Table 3, 15 articles (15%) discussed the presence of research activity and/or publications on supportive oncology issues as a marker of integration. Nine articles (9%) described the need for funding to support PC research.

Aspects of Integration Related to Administration

A total of 66 articles (65%) discussed administrative aspects, and 53 articles (52%) discussed centers of excellence, demonstration projects, and models for integration (Table 2; supplemental online Table 3).

A total of 11 articles (11%) discussed the need for national standards or policy on palliative care, and 5 articles (5%) discussed the need for regional organization. The importance of public awareness and advocacy was raised in 20 articles (20%). Other factors that contribute to integration include recognition of palliative care as a specialty (n = 25, 25%) and opioid availability (n = 7, 7%).

At the institution level, 17 articles (17%) mentioned the importance of adequate funding or reimbursement, 2 articles (2%) mentioned the importance of cancer leadership support, and 1 article (1%) mentioned the importance of PC being in the same department or division as oncology.

Discussion

Our systematic review identified a tremendous growth in the articles on integration of oncology and PC since 2010, suggesting an increased interest in this concept. Our systematic review highlighted 38 clinical, educational, research, and administrative indicators of integration. This study is part of an international effort to further develop refined and widely endorsed criteria for broad application.

Integration is an abstract and complex concept. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines integrate as “to form, coordinate, or blend into a functioning or unified whole” [30]. Leutz et al. [31] proposed three levels of integration: linkage, coordination, and full integration [32]. Linkage is described as the “relationships between systems that serve whole populations without relying on any special attention to the links, but rather a shared understanding of when, for example, to initiate a referral to another agency.” Coordination “requires structures and individuals with specific responsibility to ‘coordinate,’ with the majority of the work undertaken by separate structures within existing systems.” Full integration is achieved when resources from multiple systems are combined. The ESMO has taken the lead in establishing an incentive program recognizing cancer centers as ESMO Designated Centres of Integrated Oncology and Palliative Care. The accreditation process uses 13 criteria that examine the clinical program infrastructure and processes, and mandates an educational and research aspect [10]. This program represents a stimulus for integrating palliative care processes in institutional oncology, with more than 180 Designated Centres worldwide. Some criteria may need to be further refined.

In regard to palliative care infrastructure, outpatient clinics are discussed most often. This is because they allow for early access to palliative care. The key randomized controlled trials supporting the role of early integration of palliative care all have been conducted in the outpatient setting [5,6]. Recently, we reported that outpatient palliative care was associated with significantly improved quality of end-of-life care compared with inpatient palliative care referral [3]. Community-based palliative care also was highlighted by many as being important for provision of care at the end of the cancer trajectory. Although palliative care units and inpatient palliative care teams were discussed less often, they also have a critical role in provision of care for hospitalized patients who are often in the most distress [33]. In a recent survey, we found that a majority of cancer centers in the United States have inpatient facilities; however, few cancer centers have outpatient palliative care and community-based palliative care programs [34]. Thus, further effort is needed to increase the availability of all aspects of palliative care.

Of note, integration goes beyond the mere presence of an outpatient palliative care clinic—the comprehensiveness of the interdisciplinary team, the level of availability, and the degree of collaboration with the oncology team in delivery of patient care, such as patient care rounds, are all important. Furthermore, routine screening for symptoms in the oncology clinic may facilitate identification of patients in distress, enable appropriate supportive care measures according to institutional guidelines, and trigger a palliative care referral via clinical care pathways. Indeed, the level of integration between palliative care and oncology may be assessed on the basis of the proportion and timing of patient referral. Although early was not always defined, 15 of 18 articles recommended an appropriate time for referral as within 3 months of diagnosis of advanced disease (Table 3). Our group and others have documented that patients with cancer have variable and delayed access to palliative care [35, 36]. Further research is needed to overcome the barriers to early referral.

Of note, integration goes beyond the mere presence of an outpatient palliative care clinic—the comprehensiveness of the interdisciplinary team, the level of availability, and the degree of collaboration with the oncology team in delivery of patient care, such as patient care rounds, are all important.

In addition to referral to specialist palliative care programs, there is a heightened expectation that oncologists should be equipped with the core skills to deliver primary palliative care [37, 38]. Many authors proposed early introduction of palliative care training for undergraduates, oncology fellows, and practicing oncology professionals. Clinical rotations, lectures, standardized curriculums, and conferences may facilitate learning. Reciprocally, palliative care fellows should have a good working knowledge of oncology [39].

In addition to referral to specialist palliative care programs, there is a heightened expectation that oncologists should be equipped with the core skills to deliver primary palliative care.

The “early” theme also permeates the research aspects of integration. Because palliative care personnel see patients earlier in the disease trajectory, some investigators proposed that more research is also needed to be conducted in this population [40, 41]. Adequate funding dedicated to supportive and palliative oncology research would foster research activity and cultivate clinician scientists, resulting in more publications that can address the many gaps of knowledge [42].

Our study also highlights the need for resources and policies to foster integration at the national, regional, and institutional levels. Incentive programs and models of integration, such as the ESMO recognition program, also have an important role.

Although we mapped out many concepts related to integration, it is interesting to note that some important aspects were not found in our literature review. For instance, in our cohort of 101 articles, the term “integration” was not defined. The outcomes regarding integration of oncology and palliative care were also not clearly outlined.

This study has several limitations. First, our search strategy may not have captured all articles that discussed integration. This is partly because integration is an abstract term. For example, we excluded non-English manuscripts and conference abstracts. Because of the high number of articles and the repetition of concepts, we believe we have identified a comprehensive list of concepts related to integration. Second, a majority of publications identified in this systematic review are from the United States and Europe. Further studies are needed to examine the concept of integration of other health care systems. Third, because integration is not well defined, some of the “aspects” identified in this qualitative systematic review are subject to interpretation. We attempted to minimize bias by having two palliative oncologists review the studies, extract the themes, and arrive at a consensus. Finally, although the frequency was provided, the counts do not reflect the relative importance of each concept. This is because some articles focus solely on education, whereas others only describe an outpatient clinic. Thus, the lack of mention of a particular concept does not mean that it is not important. Instead, this preliminary list of indicators provides us with a conceptual framework of what constitutes integration of oncology and palliative care. Further effort is needed to identify the indicators of a high level of integration. A Delphi study by an international panel is actively under way for this purpose.

Conclusion

Our systematic review highlighted 38 clinical, educational, research, and administrative aspects on integration. These indicators may help us to better understand the concept of integration and may allow clinicians, patients, researchers, hospital administrators, and policy makers to better assess the level of integration of oncology and palliative care.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research is supported in part by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant CA 016672, which provided the funds for data collection at both study sites. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: Please see the related commentary, “Toward Eubiosia: Bridging Oncology and Palliative Care,” by Don S. Dizon, on page 5 of this issue.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: David Hui, Florian Strasser, Nathan Cherny, Stein Kaasa, Mellar P. Davis, Eduardo Bruera

Provision of study material or patients: David Hui

Collection and/or assembly of data: David Hui, Yu Jung Kim, Ji Chan Park, Yi Zhang

Data analysis and interpretation: David Hui, Yu Jung Kim

Manuscript writing: David Hui, Eduardo Bruera

Final approval of manuscript: David Hui, Yu Jung Kim, Ji Chan Park, Yi Zhang, Florian Strasser, Nathan Cherny, Stein Kaasa, Mellar P. Davis, Eduardo Bruera

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Hui D, Bruera E. Supportive and palliative oncology: A new paradigm for comprehensive cancer care. Oncol Hematol Rev. 2013;9:68–74. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hui D, De La Cruz M, Mori M, et al. Concepts and definitions for “supportive care,” “best supportive care,” “palliative care,” and “hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:659–685. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1564-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120:1743–1749. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yennurajalingam S, Urbauer DL, Casper KL, et al. Impact of a palliative care consultation team on cancer-related symptoms in advanced cancer patients referred to an outpatient supportive care clinic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Board IOMNCP. Improving Palliative Care for Cancer. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: Accomplishments, the need, next steps--from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3052–3058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherny N, Catane R, Schrijvers D, et al. European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Program for the integration of oncology and Palliative Care: A 5-year review of the Designated Centers’ incentive program. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:362–369. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44(suppl):166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandieri E, Sichetti D, Romero M, et al. Impact of early access to a palliative/supportive care intervention on pain management in patients with cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2016–2020. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalberg T, Jacob-Files E, Carney PA, et al. Pediatric oncology providers’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to early integration of pediatric palliative care. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1875–1881. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Temel JS, Jackson VA, Billings JA, et al. Phase II study: Integrated palliative care in newly diagnosed advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2377–2382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobsen J, Jackson V, Dahlin C, et al. Components of early outpatient palliative care consultation in patients with metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:459–464. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston B, Buchanan D, Papadopoulou C, et al. Integrating palliative care in lung cancer: An early feasibility study. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2013;19:433–437. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2013.19.9.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferguson A, Makin W, Walker B, et al. Regional implementation of a national cancer policy: Taking forward multiprofessional, collaborative cancer care. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 1998;7:162–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.1998.00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaertner J, Wolf J, Ostgathe C, et al. Specifying WHO recommendation: Moving toward disease-specific guidelines. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:1273–1276. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaertner J, Wolf J, Hallek M, et al. Standardizing integration of palliative care into comprehensive cancer therapy—a disease specific approach. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1037–1043. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1131-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaertner J, Wuerstlein R, Ostgathe C, et al. Facilitating early integration of palliative care into breast cancer therapy. Promoting disease-specific guidelines. Breast Care (Basel) 2011;6:240–244. doi: 10.1159/000329007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hauser J, Sileo M, Araneta N, et al. Navigation and palliative care. Cancer. 2011;117(suppl):3585–3591. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Payne S, Chan N, Davies A, et al. Supportive, palliative, and end-of-life care for patients with cancer in Asia: Resource-stratified guidelines from the Asian Oncology Summit 2012. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e492–e500. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaertner J, Weingärtner V, Wolf J, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: How to make it work? Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:342–352. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283622c5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaertner J, Wolf J, Frechen S, et al. Recommending early integration of palliative care - does it work? Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:507–513. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy MH, Adolph MD, Back A, et al. Palliative care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:1284–1309. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutradhar R, Seow H, Earle C, et al. Modeling the longitudinal transitions of performance status in cancer outpatients: Time to discuss palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:726–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyers FJ, Linder J, Beckett L, et al. Simultaneous care: A model approach to the perceived conflict between investigational therapy and palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:548–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Definition of integrate. Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary 2014. Available at http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/integrate. Accessed October 20, 2014.

- 31.Leutz WN. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: Lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. Milbank Q. 1999;77:77–110, iv–v. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masso M, Owen A. Linkage, coordination and integration: Evidence from rural palliative care. Aust J Rural Health. 2009;17:263–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2009.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruera E, Hui D. Palliative care units: The best option for the most distressed. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1601–; author reply 1601–1602. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303:1054–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hui D, Kim SH, Kwon JH, et al. Access to palliative care among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. The Oncologist. 2012;17:1574–1580. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hui D, Parsons H, Nguyen L, et al. Timing of palliative care referral and symptom burden in phase 1 cancer patients: A retrospective cohort study. Cancer. 2010;116:4402–4409. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abrahm JL. Integrating palliative care into comprehensive cancer care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:1192–1198. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Payne R. The integration of palliative care and oncology: The evidence. Oncology (Williston Park) 2011;25:1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kiely MT, Alison DL. Palliative care activity in a medical oncology unit: The implications for oncology training. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2000;12:179–181. doi: 10.1053/clon.2000.9146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ida RC, Adelaide PM, Stefania B. Supportive care in cancer unit at the National Cancer Institute of Milan: A new integrated model of medicine in oncology. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:391–396. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328352eabc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Von Roenn JH, Temel J. The integration of palliative care and oncology: The evidence. Oncology (Williston Park) 2011;25:1258–1260, 1262, 1264–1265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hui D, Parsons HA, Damani S, et al. Quantity, design, and scope of the palliative oncology literature. The Oncologist. 2011;16:694–703. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.