Abstract

The aim of the study was to investigate the molecular genetics of uveal melanoma (UM) metastases and correlate it with disease progression. Twelve pathologically confirmed UM metastases from 11 patients were included. Molecular genetic alterations in chromosomes 3 (including the BAP1 region), 8q, 6p, and 1p were investigated by microsatellite genotyping. Mutations in codon 209 of GNAQ and GNA11 genes were studied by restriction-fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). We identified monosomy of chromosome 3 in tumors from four patients with an average survival of 5 months (range 1–8 months) from time of diagnosis of metastatic disease. In contrast, tumors with either disomy or partial chromosome 3 alterations showed significantly slower metastatic disease progression with an average survival of 69 months (range 40–123 months, p = 0.003). Alterations in chromosomal arms 1p, 6p, and 8q and mutations in either GNAQ or GNA11 showed no association with disease progression. Prominent mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate was observed in tumors from patients with slowly progressive disease. In conclusion, in UM metastases, monosomy 3 is associated with highly aggressive, rapidly progressive disease while disomy or partial change of 3 and prominent mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate in the tumor is associated with better prognosis. These findings should be considered when designing clinical trials testing effectiveness of various therapies of metastatic UM.

Keywords: molecular genetics, eye neoplasms, uveal melanoma

1. Introduction

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most common primary intraocular malignant tumor in adults (Singh and Topham, 2003). Although the vast majority of patients with metastatic UM have short survival, a small subset of patients survive more than four years (Bedikian et al., 1995; Rietschel et al., 2005). It is unknown whether there are characteristics inherent in UM that cause patients to have different clinical outcomes (Rietschel et al., 2005).

Correlation of molecular and cytogenetic profile of primary UM with patient survival is well established. Monosomy 3 is noted in 50–60% of primary tumors and confers a poor clinical prognosis (Damato and Coupland, 2009; Harbour, 2009; Prescher et al., 1996; Shields et al., 2008). It has been suggested that metastasis in the absence of monosomy 3 is quite rare (Prescher et al., 1996). Mutation in the BRCA-1 associated protein-1 (BAP1) gene, located on chromosome 3, has been identified recently with a high frequency in UM primary tumors that metastasize (Harbour et al., 2010). Other chromosomal abnormalities portending a poor prognosis include gain in chromosomal arm 8q and loss of chromosomal arm 1p, while alteration in chromosomal arm 6p is associated with better prognosis (Damato and Coupland, 2009; Harbour, 2009; Shields et al., 2008). Expression-based molecular testing of primary tumors classifies UM into class 1 and class 2 based upon expression of a subset of genes, with class 2 patients having poor prognosis (Harbour, 2009; Onken et al., 2004). Finally, mutations in two G-proteins, GNAQ and GNA11, have also recently been identified in the majority of UM primary tumors and are being considered potential targets for novel therapies (Van Raamsdonk et al., 2009; Van Raamsdonk et al., 2010).

There is very little known about the molecular genetics of UM metastases, in particular the difference between rapidly and slowly progressive tumors. The two studies reporting on the molecular genetics of UM metastases revealed monosomy 3 in the majority of tumors (Singh et al., 2009; Trolet et al., 2009) However, a small subset, 25.6%, showed either disomy of chromosome 3 or partial chromosome 3 alterations (Singh et al., 2009; Trolet et al., 2009). The clinical features such as time to develop metastasis or the rate of progression of the metastatic lesions were not reported in both studies. Although no gene expression-based studies are available for UM metastases, 3/26 patients with class 1 primary tumors (non-aggressive) went on to develop metastatic disease, occurring 131.2, 87.8, and 8.1 months following presentation (Harbour et al., 2010). This suggests that a subset of patients with class 1 gene profiles do develop metastatic disease; albeit with relatively longer time from presentation.

Our study was conducted to investigate the molecular genetic changes of metastatic UM lesions and correlate these findings with clinical disease progression.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patient samples

All specimens were collected as per Institutional Review Board approved protocol after obtaining proper informed consents from the patients. A total of 12 metastatic UM from 11 different patients were included, Table 1. Seven of these lesions were from liver, one from a peritoneal mass, two from lung, one from breast and one from bone metastases. All specimens were archival material obtained in the course of conventional clinical therapy of the patients. Five of the hepatic lesions were obtained through True-Cut needle biopsy and two from surgical excision. Of the non-hepatic lesions, 4/5 were obtained through surgical excision and 1/5 through needle biopsy. Matching primary and metastatic lesions were available in four patients. In 9/11 patients, the tumor tissues were obtained prior to commencement of systemic therapy. In patient MM0001 tumor tissue from peritoneal nodule was obtained after, chemoembolization of hepatic tumor, intraperitoneal paxitaxel therapy and systemic therapy with sorafenib and bevacizumab for 6 months. In patient MM0004 tumor tissue was obtained while the patient was on sunitinib therapy and after 2 years of finishing chemotherapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin in combination with sorafenib.

Table 1.

Clinical features of samples included in the study.

| Patient ID | Age at diagnosis of primary | Sex | Primary tumor

|

Metastasisc

|

Survival

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (mm) | Location | Therapy | Number/size (mm) | Location | Therapy | Tmet | Tdeath | |||

| UM6001 | 46 | F | 10 × 7.1 | CH | Enucleation | Multiple largest 130 × 80 mm | Livera | Sunitinib and avastin | 27 | 8 |

| UM8008 | 70 | M | 11 × 10 | CH/CB | Enucleation | Multiple largest 46 × 33 mm | Liver,a lung | Abraxane, sunitinib, | 10 | 5 |

| UM8002 | 69 | M | 10 × 5 | CH | Enucleation | Two 21 × 16 and 14 × 13 mm | Livera | Combined PC, combined CVD | 21 | 11 |

| MM0006 | 63 | M | 10.5 × 3.7 | CH | Brachytherapy | Numerous liver lesions | Liver,a lung | Avastin | 83 | 1 |

| UM4033 | 27 | M | 18 × 7.9 | CH | Enucleation | Multiple largest 19 × 15 mm | Livera | IHP, temozolomide | 25 | 40b |

| MM0001 | 44 | F | 9 × 3.1 | CH | Brachytherapy, Laser photocoagulation | Multiple small liver and peritoneal | Liver, lung, peritoneala | IP paclitaxel; sorafenib plus bevacizumab; sunitinib; IHP; GM-CSF; IL-2 | 177 | 97(a) |

| MM0004 | 46 | F | >18 × 8 | CH | Enucleation | Three liver lesions largest 44 × 42 mm, one adrenal 38 × 30, one bone 18 mm | Liver, bone,a adrenal | Resection, combined PC plus sorafenib; sorafenib; sunitinib | 66 | 49 |

| UM5061 | 70 | M | 6 × 2 | CB/Iris | TTT, enucleation | Single 55 × 50 | Livera | Resection/temozolomide; combined PC; dacarbazine + sorafenib; sorafenib; CVD | 56 | 71 |

| MM0007 | 35 | F | NA | CH | Enucleation | Two, 7 × 5 × 4 (lung), 7 × 5 × 4 (breast) | Breast,a lunga | Resection; sunitinib, TGF-β | 273 | 123 survived 18 month after diffuse disease |

| MM0002 | 49 | M | 10 × 2.2 | CH | Laser photocoagulation, brachytherapy | Single 8 × 7 × 5 | Livera | Resection | 94 | 51(a) |

| MM0005 | 34 | F | NA | CH | Proton beam | Single 38 × 35 × 27 | Lunga | Resection, abraxane; ANA773; sunitinib | 240 | 52(a) |

NA: tumor size not available, CH: choroid, CB: ciliary body. TTT: transpupillary thermal therapy.

Therapy: IHP: isolated hepatic perfusion, combined paclitaxel and carboplatin (PC), combined cisplatin, vinblastine and dacarbazine (CVD), albumin-bound paclitaxel (abraxane), granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), Interleukin 2 (IL-2), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), and ANA773 tosylate (ANA733). Tmet: time to metastasis, Tdeath: time to death.

Denotes metastatic location included in the study.

Cause of death neutropenia/intracranial hemorrhage.

At the time of diagnosis of metastatic disease.

2.2. DNA extraction and genotyping

Tumor DNA was extracted from 5 to 10 cut sections from each sample. The tumor tissues were microdissected from surrounding non-tumor tissue in order to obtain a minimum of 80% tumor cell population. Microdissection was carried out either by a surgical microscope and scalpel in large tumors or utilizing a Laser Capture Microdissection System (Arcturus Pixcell II, Mountainview, CA) in small needle biopsies. DNA Extraction was carried out utilizing Qiagen QIAamp DNA Microkit (Qiagen, Valenca, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Germline DNA was obtained from peripheral blood leucocytes. The DNA integrity and quality was assessed using minigel electrophoresis and the 260/280 absorbance ratio assessed with an Epoch spectrophotometer plate reader. Extracted DNA was stored at 4 °C until the time of experiments.

Genotyping was carried out utilizing microsatellite markers on chromosomes 1p, 3, 6p and 8q according to our published protocol (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2011). Allelic imbalance factor (AIF) was determined by calculating the ratio of allele heights for both the normal peripheral blood (N) and tumor (T) sample from each patient and then the tumor ratio was divided by the normal ratio: [T1:T2/N1:N2] with N1 as the highest of the two N alleles (Cawkwell et al., 1993; Skotheim et al., 2001). Loss of heterozygosisty (LOH) was considered in samples with total loss of an allele or an allelic imbalance factor of ≥3. This ratio represents total loss, or gain, of an allele observed in at least 2/3 of the tumor cells. Allelic imbalance was defined as a skewed intensity ratio between two alleles at a locus in the tumor compared to the normal DNA (Skotheim et al., 2001). We selected a threshold of allelic imbalance factor of > 1.5 for scoring regions with allelic imbalance. This ratio is equivalent to loss or gain of an allele observed in at least 1/3 of the tumor cells. Deletion of BAP1 was assessed by evaluation of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) using microsatellite markers flanking the BAP1 region on 3p21.

2.3. GNAQ and GNA11 mutation analysis

Mutational screening of codons 183 and 209 of GNAQ and GNA11 genes were carried out by restriction-fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). Primers, enzymatic digestion conditions and enzymes used are listed in Table 1 supplement. All restriction enzymes were obtained from New England Biolab (Ipswich, MA). PCR was performed using a C1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) utilizing the Qiagen Hot Start Taq master mixture with an initial incubation at 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 34 cycles of denaturation (94 °C 30 s), annealing (60 °C 45 s) and elongation (72 °C 45 s). Results were validated in two separate reactions.

2.4. Pathological assessment

Pathological features including cell type, tumor vascularity, necrosis, mononuclear inflammatory cellular infiltration and fibrosis were assessed by a pathologist (MHA) from routinely stained histological preparations. Cellular proliferation was assessed by two independent observers separately (MHA, CMC) in a masked fashion using immunohistochemistry for Ki-67 (Mib-1 clone, Invitrogen). The average staining in 10 different high power fields was calculated. Samples with more than 5% differences were reviewed by both observers to reach a consensus reading.

2.5. Statistical analysis

GB-STAT software was used to conduct the statistical analysis. Fisher’s exact test was conducted to compare long and short survival across molecular genetic, pathological and clinical prognostic markers, Table 3. Rapid progression (short survival) was defined as rapid disease progression with less than one year survival after diagnosis of metastatic disease. Long survival (slow progression) was defined as survival for three or more years after diagnosis of metastatic disease.

Table 3.

Correlation of clinical, pathological and molecular features of metastatic tumors and length of patients’ survival.

| Clinical/molecular genetic feature | Total (%) | Short survival <1 year (%) | Long survival >1 year () | p-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAP1 LOH | 9/11 | 4/4 | 5/7 | 0.49 |

| Monosomy 3 | 4/11 | 4/4 | 0/7 | 0.003 |

| Partial chr 3/disomy 3 | 7/11 | 0/4 | 7/7 | 0.003 |

| 1p LOH | 5/10 | 3/4 | 2/6 | 0.52 |

| 8q LOH | 9/11 | 4/4 | 5/7 | 0.49 |

| 6p LOH | 6/10 | 3/4 | 3/6 | 0.57 |

| GNAQ or GNA11 mutation | 8/11 | 4/4 | 4/7 | 0.23 |

| Positive epitheliod cells | 6/11 | 4/4 | 2/7 | 0.06 |

| Strong tumor vasculature | 8/11 | 3/4 | 5/7 | 0.24 |

| Inflammatory infiltrate ≥5% | 7/10 | 0/3 | 7/7 | 0.008 |

| Lung/soft tissue | 2/11 | 0/4 | 2/7 | 0.49 |

| Liver metastasis | 9/11 | 4/4 | 5/7 | 0.49 |

| Female sex | 5/11 | 1/4 | 4/7 | 0.54 |

| Treatment with surgery/IHT | 5/11 | 0/4 | 5/7 | 0.06 |

| Age at metastasis <60 years | 7/11 | 1/4 | 6/7 | 0.088 |

| ≥48 months from initial diagnosis to metastasis | 7/11 | 1/4 | 6/7 | 0.088 |

| Metastasis in >1 organ | 8/11 | 3/4 | 5/7 | 1 |

| Prominent tumor necrosis | 4/11 | 1/4 | 3/7 | 1 |

| Ki-67 ≥ 10% | 8/11 | 4/4 | 4/7 | 0.24 |

| Prominent fibrosis | 4/11 | 1/4 | 3/7 | 1 |

Fisher’s exact test.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics and tumor pathology

A total of 11 patients (6 men and 5 women) were included in our study, with a mean age at diagnosis of 50 years (range 27–70), Table 1. The primary tumors were choroidal in nine patients, ciliochoroidal in one patient and ciliary body/iris melanoma in one patient. Metastatic disease was detected an average of 98 months after treatment of the primary tumor with a considerable range, from 10 months to more than 22 years. Variation of patient survival after detection of metastatic disease was also observed with four patients surviving less than one year (average of 6.3 months, range 1–11 months), and seven patients surviving more than 40 months after diagnosis (average of 68 months, range of 40–123 months).

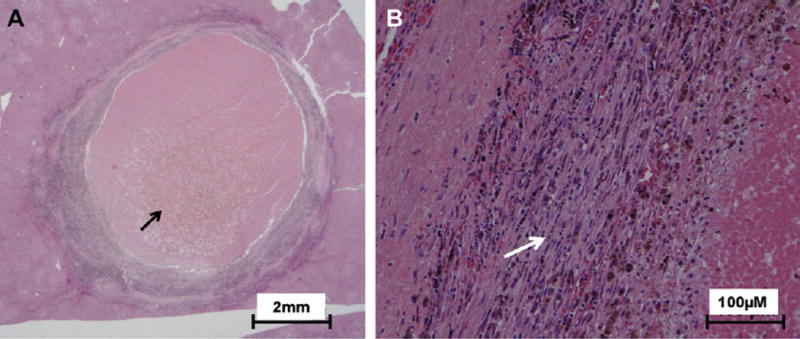

At the time of diagnosis of metastatic disease, eight patients presented with more than one metastatic lesion and three patients presented with one lesion. Table 2, summarizes the major pathological features observed in metastatic lesions. The tumor cells were epithelioid or predominantly epithelioid in 6/11 tumors and spindle or predominantly spindle in 5/11 tumors. Prominent mononuclear inflammatory cellular infiltrate in more than 5% of the tumor area was observed in 7/11 tumors. One tumor (MM0002) showing marked necrosis and significant desmoplastic reaction surrounding the tumor and inflammatory cells, Fig. 1. The presence of mononuclear inflammatory cells was associated with longer survival (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.008). Pathological features including tumor vessel density, tumor necrosis, tumor cell proliferation and prominent fibrosis were not statistically significant between rapidly and slowly progressive tumors, Table 3. The presence of epithelioid cells in association with short survival approached but did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.06). Interestingly, in liver metastases epithelioid cells predominated (5/7 specimens), while in other metastatic locations spindle morphology predominated (4/5 specimens).

Table 2.

Pathological features of the metastatic tumors included in the study.

| Patient | Specimen | Metastatic tumor

|

Primary tumor

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histology | Inflammation | Ki-67 | Necrosis | Fibrosis | Vascularity | Histology | ||

| UM6001 | Needle biopsy | Epitheliod | <1% | 30% | 20% of biopsy | Minimal | Prominent | Mixed |

| UM8008 | Needle biopsy | Predominant epitheliod, few spindle | <1% | 20% | No | Focal | Prominent | Mixed predominantly spindle |

| UM8002 | Needle biopsy | Epitheliod | NA | 40% | Minimal | NA | NA | Epithelioid |

| MM0006 | Needle biopsy | Epitheliod | <1% | 30% | Minimal | None | Prominent | Unknown |

| UM4033 | Needle biopsy | Spindle | 20% | 20% | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal | Mixed |

| MM0001 | Excision biopsy | Mixed predominantly epitheliod | 10% | 15% | Minimal | Prominent | Moderate | Unknown |

| MM0004 | Resection | Predominantly spindle | 30% | 50% | Moderate | Minimal | Moderate | Mixed |

| UM5061 | Resection | Epitheliod | 20% | 0% | Minimal | Prominent | Minimal | Mixed |

| MM0007 (breast) | Resection | Mixed predominantly spindle | ~5% | <1% | None | Minimal | Moderate | Unknown |

| MM0007 (lung) | Resection | Spindle | ~5% | <1% | None | Minimal | Minimal | Unknown |

| MM0002 | Resection | Spindle | 30% | 5% | Prominent | Prominent | Prominent | Unknown |

| MM0005 | Resection | Spindle | 5% | 10% | Moderate | Minimal | Moderate | Unknown |

Fig. 1.

Pathological feature of metastatic liver lesion with significant inflammatory infiltrate and necrosis. A) Low power (1×) of a solitary hepatic lesion resected from the liver of patient. Marked necrosis of the center of the lesion is prominent (black arrow). B) Higher power (20×) view reveal desmoplastic reaction with severe fibrosis surrounding the malignant cells and prominent mononuclear inflammatory cellular infiltrate (white arrow).

3.2. Molecular genetic analyses

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the molecular genetic alterations observed in the 12 metastatic tumors from 11 patients including two tumors from the same patient MM0007. The two tumors, one from breast and other from lung, showed similar molecular genetic alterations, Table 3 and Table 2 supplement. Of the 11 patients, four had tumors with loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of all informative markers on chromosome 3 (monosomy 3, M3), five patients had partial LOH of chromosome 3, and 2 had retention of heterozygosity (ROH) of all the informative markers (disomy 3). LOH of markers in the 1p, 8q and 6p regions were observed in tumors from 5/10, 9/11 and 6/10 patients respectively. Mutations in codon 209 (Q209L) in either GNAQ or GNA11 were observed in tumors from 8/11 patients. Primary tumors from four patients, UM6001, UM8008, UM8002 and UM4033 were available and showed identical genetic changes to the metastatic tumors.

The time to development of detectable metastatic disease following diagnosis of primary tumor (Tmet) ranged from 10 to 273 months, Table 1. In all except two patients, MM0001 and MM0004, the Tmet were within two weeks of the time of obtaining of tissue samples. The time from diagnosis of metastasis to patient death (Tdeath) varied from 1 to 123 months, with three patients still alive at the time of last follow up. Tmet in the patients with M3 ranged from 10 to 83 months (mean 37), while in patients with partial chromosome 3 or disomy 3 it ranged from 25 to 273 months (mean 136.3). Tdeath ranged from 1 to 8 months (mean 5) in M3 patients as opposed to 40–123 months (mean 69) in those patients without M3. The difference in M3 status between patients who survived more than 36 months after diagnosis of metastatic disease (0/7) and those who died in less than a year after diagnosis of metastasis (4/4) was statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.003). The frequency of molecular genetic alterations in 1p, 6p and 8q, and somatic mutation in either GNAQ or GNA11 genes in metastatic tumor tissue were not statistically different between the rapidly progressive and slowly progressive metastatic lesions, Table 3 and Table 2 supplement.

4. Discussion

In UM there is ample evidence of the association of the primary tumor’s molecular genetics with early development of metastasis, usually within 3 years of diagnosis (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2011; Shields et al., 2011). However, this is the first report linking the molecular genetic alterations of the metastatic lesions with overall tumor progression and patient survival. The results of this study support the existence of biologically different subtypes of meta-static UM. It also suggests that monosomy 3 of the metastatic UM is associated with rapidly progressive metastatic lesions. In contrast, metastases with partial 3 and disomy 3 status were present in patients with long survival. None of the other molecular genetic changes commonly identified in primary UM including alterations in chromosomal arms 1p, 6p and 8q and activating mutations of GNA11 and/or GNAQ genes, were associated with tumor progression in metastatic lesions.

Our data indicate that molecular genetics, in particular monosomy 3 status, of metastatic UM could provide important insight into disease progression. Such information may also be crucial for designing therapeutic clinical trials because the relatively long survival of patients with partial change of chromosome 3 or disomy 3 could bias the outcome of any clinical trial that includes a significant number of these patients.

Variation in the survival of metastatic UM has been reported by Rietschel and colleagues, who identified a small subset, 22%, of metastatic UM with rather long survival of more than 48 months (Rietschel et al., 2005). Such long survival contrasted the short survival of less than one year in the rest of the patients (Rietschel et al., 2005). The frequency of highly aggressive metastatic lesions with M3 was relatively low in our study but that likely a selection bias toward inclusion of slowly progressing metastatic UM due to the availability of tumor tissues. Slowly progressive tumors are more frequently biopsied and treated by surgical resection. On the contrary, many of the rapidly progressive tumors are either not biopsied or biopsied using a fine needle aspiration that did not yield enough tissue for molecular genetic analysis. Of note, the frequency of metastatic UM with M3 in the largest report of patients with long survival is closely matching the frequency of tumors with no M3 reported in the largest study to date, 66 patients, of the molecular genetics of metastatic UM (Trolet et al., 2009). However, the latter study didn’t evaluate the survival association of different molecular genetic changes.

The association between monosomy 3, but not disomy or partial chromosome 3 alteration, with aggressive UM, lack of inflammatory cellular infiltration and rapidly progressive metastatic tumors suggests that combined disruption of more than one gene in different locations on chromosome 3 is important for tumor aggressiveness. Several genetic studies of the smallest regions of deletion in UM have found multiple regions in chromosome 3 on both the p and q arms; however, these regions don’t generally overlap between different studies(Abdel-Rahman et al., 2011; Hausler et al., 2005; Parrella et al., 2003; Tschentscher et al., 2001).

With the exception of the degree of mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate in the tumor, other pathological features such as degree of tumor cell proliferation, tumor vascularity, fibrosis and necrosis were not associated with prognostic significance. The observed association between mononuclear inflammatory cellular infiltrate in the tumor and tumor progression will need further studies to identify the type of inflammatory cells and association between such finding and monosomy 3 status. However, given the limited amount of tissue samples available in the majority of our patients we couldn’t carry out such assessments. These findings highlight the importance of host factors in the development and progression of metastatic disease and imply that immunologic therapies to treat metastatic uveal melanoma may have the potential to impact patient survival.

The association between increased mononuclear inflammatory cellular infiltrate and long survival in our study is rather contrary to what has been reported in primary tumors from UMs (Maat et al., 2008). One potential explanation is the difference in the type of inflammatory cellular infiltrate between primary and metastatic tumors. In primary tumors the inflammatory cells are mostly macrophages (Maat et al., 2008). However, in metastatic tumors the inflammatory cells are likely NK and lymphocytes (Niederkorn, 2009; Verbik et al., 1997). It has been reported that significant differences exists between the degree of inhibition of T-cell proliferation between metastatic and primary UM cell lines obtained from the same patient (Verbik et al., 1997). In addition, the association between monosomy 3 and increased HLA class I expression on tumor cells could explain the immune escape mechanism of monosomy 3 tumors which would be more resistant to NK cell lysis in extra-ocular locations (Maat et al., 2008; Niederkorn, 2009). However, the molecular mechanism of increase of HLA class I expression in monosomy 3 tumors is still not clear. Several genes on different locations on chromosome 3 modulate the inflammatory response and have been linked to increased predisposition to inflammatory bowl disease. These genes include CCR5, CCR9, hMLH1 and IL-12A (Ahmad et al., 2001). Also, it has been suggested that loss of activity of PPARγ could result in inflammatory phenotype in primary UM tumors (Maat et al., 2008). However, the role of disruption of these genes in primary and metastatic UM tumors needs to be further elucidated.

A recent report has indicated high frequency of somatic BAP1 mutation in primary UM tumors that metastasize (Harbour et al., 2010). We tested for somatic deletions in BAP1 using genotyping of markers spanning the gene and identified LOH of markers in close proximity to BAP1 in 8/11 patients, including four with long survival. LOH of BAP1 region was not associated with survival in our analysis. However, our data don’t exclude the possibility of a biallelic inactivation of BAP1, through mutation and deletion, being associated with rapidly progressive tumors. We were unable to sequence the BAP1 gene in our samples to test for biallelic inactivation due to the limited amount and quality of DNA obtained from small archival biopsy material. Alternately, other genes besides BAP1 may influence survival with metastatic disease. Further studies will be needed to address such possibilities.

Several clinical features of patients with metastatic disease have been suggested to correlate with better prognosis (Rietschel et al., 2005). These include lung/soft tissue as the site of first metastasis, treatment with surgery or intrahepatic therapy, female sex, age younger than 60, and a longer interval from initial diagnosis to metastatic disease (Rietschel et al., 2005). In our series, similar factors were more common in long survivors, including longer interval from initial diagnosis to metastasis (p = 0.088), treatment of the metastatic tumor with surgery or intrahepatic chemotherapy (p = 0.06), and age of diagnosis younger than 60 years (p = 0.088), but the difference was not statistically significant, possibly due to the small sample size, Table 3. Also, more females were among the long survivors (4/7). Five out of the seven long survivors had liver metastasis, three of them presenting with more than one nodule and two with single nodule. A multivariate analysis of different clinical and molecular prognostic markers was not possible due to small sample size and further studies of the relative significance of each prognostic marker in comparison with tumor molecular genetics will be required.

Seven of the metastatic UM included in our study developed metastatic disease more than four years after treatment of their primary tumors with three patients presenting after more than 10 years (14.8, 20, and 22.8 years), Table 1. This indicates that these tumors remained dormant or had very slow growth rate for considerable period of time after initial spread from the eye. In support of the dormancy/slow growth of a subset of metastatic UM, two patients with multiple liver metastasis (UM4033 and UM0004) showed very slow growth of their metastatic lesions during follow up.

Somatic GNAQ and GNA11 mutations are unique for UM, (Van Raamsdonk et al., 2009; Van Raamsdonk et al., 2010) and have not been reported in other types of melanomas. GNAQ or GNA11 mutations were present in the majority of the metastatic tumors in our study, including the three tumors with a disease free interval greater than 10 years between primary and metastatic disease. These data are consistent with the uveal melanoma origin of the metastases.

One of the limitations of our study is the small number of patients included and further larger studies, preferably involving multiple centers, will be needed to confirm our results. Another potential limitation of the study is the possibility that the small biopsy material obtained from the rapidly growing tumors may not represent the pathology in the remainder of the tumor. Although such sampling variation could have some effect on the pathological features, it is unlikely to effect the molecular genetic findings due to the monoclonality of the tumor. Further studies of post-mortem samples collected from the rapidly growing tumors will be necessary to validate our initial pathological findings.

In conclusion, our results suggest the existence of biologically and molecularly different subtypes of metastatic UM. It also suggests that in metastatic UM monosomy 3 is associated with highly aggressive, rapidly progressive disease while prominent mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate in the tumor is associated with better prognosis. These findings should be considered when designing clinical trials testing effectiveness of various therapies of metastatic UM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by the Patti Blow Research fund in Ophthalmology.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.exer.2012.04.010.

References

- Abdel-Rahman MH, Christopher BN, Faramawi MF, Said-Ahmed K, Cole C, McFaddin A, Ray-Chaudhury A, Heerema N, Davidorf FH. Frequency, molecular pathology and potential clinical significance of partial chromosome 3 aberrations in uveal melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:954–962. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad T, Satsangi J, McGovern D, Bunce M, Jewell DP. Review article: the genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:731–748. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedikian AY, Legha SS, Mavligit G, Carrasco CH, Khorana S, Plager C, Papadopoulos N, Benjamin RS. Treatment of uveal melanoma meta-static to the liver: a review of the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience and prognostic factors. Cancer. 1995;76:1665–1670. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951101)76:9<1665::aid-cncr2820760925>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawkwell L, Bell SM, Lewis FA, Dixon MF, Taylor GR, Quirke P. Rapid detection of allele loss in colorectal tumours using microsatellites and fluorescent DNA technology. Br J Cancer. 1993;67:1262–1267. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damato B, Coupland SE. Translating uveal melanoma cytogenetics into clinical care. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:423–429. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbour JW. Molecular prognostic testing and individualized patient care in uveal melanoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:823–829. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbour JW, Onken MD, Roberson ED, Duan S, Cao L, Worley LA, Council ML, Matatall KA, Helms C, Bowcock AM. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science. 2010;330:1410–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.1194472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausler T, Stang A, Anastassiou G, Jockel KH, Mrzyk S, Horsthemke B, Lohmann DR, Zeschnigk M. Loss of heterozygosity of 1p in uveal melanomas with monosomy 3. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:909–913. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maat W, Ly LV, Jordanova ES, de Wolff-Rouendaal D, Schalij-Delfos NE, Jager MJ. Monosomy of chromosome 3 and an inflammatory phenotype occur together in uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:505–510. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederkorn JY. Immune escape mechanisms of intraocular tumors. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:329–347. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken MD, Worley LA, Ehlers JP, Harbour JW. Gene expression profiling in uveal melanoma reveals two molecular classes and predicts metastatic death. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7205–7209. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrella P, Fazio VM, Gallo AP, Sidransky D, Merbs SL. Fine mapping of chromosome 3 in uveal melanoma: identification of a minimal region of deletion on chromosomal arm 3p25.1–p25.2. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8507–8510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescher G, Bornfeld N, Hirche H, Horsthemke B, Jockel KH, Becher R. Prognostic implications of monosomy 3 in uveal melanoma. Lancet. 1996;347:1222–1225. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90736-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietschel P, Panageas KS, Hanlon C, Patel A, Abramson DH, Chapman PB. Variates of survival in metastatic uveal melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8076–8080. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.6534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CL, Ganguly A, Bianciotto CG, Turaka K, Tavallali A, Shields JA. Prognosis of uveal melanoma in 500 cases using genetic testing of fine-needle aspiration biopsy specimens. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields JA, Shields CL, Materin M, Sato T, Ganguly A. Role of cyto-genetics in management of uveal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:416–419. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AD, Topham A. Incidence of uveal melanoma in the United States: 1973–1997. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:956–961. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AD, Tubbs R, Biscotti C, Schoenfield L, Trizzoi P. Chromosomal 3 and 8 status within hepatic metastasis of uveal melanoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1223–1227. doi: 10.5858/133.8.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skotheim RI, Diep CB, Kraggerud SM, Jakobsen KS, Lothe RA. Evaluation of loss of heterozygosity/allelic imbalance scoring in tumor DNA. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2001;127:64–70. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(00)00433-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trolet J, Hupe P, Huon I, Lebigot I, Decraene C, Delattre O, Sastre-Garau X, Saule S, Thiery JP, Plancher C, Asselain B, Desjardins L, Mariani P, Piperno-Neumann S, Barillot E, Couturier J. Genomic profiling and identification of high-risk uveal melanoma by array CGH analysis of primary tumors and liver metastases. Invest. Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2572–2580. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschentscher F, Prescher G, Horsman DE, White VA, Rieder H, Anastassiou G, Schilling H, Bornfeld N, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Horsthemke B, Lohmann DR, Zeschnigk M. Partial deletions of the long and short arm of chromosome 3 point to two tumor suppressor genes in uveal melanoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3439–3442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Raamsdonk CD, Bezrookove V, Green G, Bauer J, Gaugler L, O’Brien JM, Simpson EM, Barsh GS, Bastian BC. Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and blue naevi. Nature. 2009;457:599–602. doi: 10.1038/nature07586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Raamsdonk CD, Griewank KG, Crosby MB, Garrido MC, Vemula S, Wiesner T, Obenauf AC, Wackernagel W, Green G, Bouvier N, Sozen MM, Baimukanova G, Roy R, Heguy A, Dolgalev I, Khanin R, Busam K, Speicher MR, O’Brien J, Bastian BC. Mutations in GNA11 in uveal melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2191–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbik DJ, Murray TG, Tran JM, Ksander BR. Melanomas that develop within the eye inhibit lymphocyte proliferation. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:470–478. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19971114)73:4<470::aid-ijc3>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.