Abstract

Background and Purpose

Muscle tension dysphonia (MTD), a common voice disorder that is not commonly referred for physical therapy intervention, is characterized by excessive muscle recruitment, resulting in incorrect vibratory patterns of vocal folds and an alteration in voice production. This case series was conducted to determine whether physical therapy including manual therapy, exercise, and stress management education would be beneficial to this population by reducing excess muscle tension.

Case Description

Nine patients with MTD completed a minimum of 9 sessions of the intervention. Patient-reported outcomes of pain, function, and quality of life were assessed at baseline and the conclusion of treatment. The outcome measures were the numeric rating scale (NRS), Patient-Specific Functional Scale (PSFS), and Voice Handicap Index (VHI). Cervical and jaw range of motion also were assessed at baseline and postintervention using standard goniometric measurements.

Outcomes

Eight of the patients had no pain after treatment. All 9 of the patients demonstrated an improvement in PSFS score, with 7 patients exceeding a clinically meaningful improvement at the conclusion of the intervention. Three of the patients also had a clinically meaningful change in VHI scores. All 9 of the patients demonstrated improvement in cervical flexion and lateral flexion and jaw opening, whereas 8 patients improved in cervical extension and rotation postintervention.

Discussion

The findings suggest that physical therapists can feasibly implement an intervention to improve outcomes in patients with MTD. However, a randomized clinical trial is needed to confirm the results of this case series and the efficacy of the intervention. A clinical implication is the expansion of physical therapy to include referrals from voice centers for the treatment of MTD.

The risk of developing a voice disorder is 30%.1 Voice disorders cost approximately $2.5 billion in lost wages, physicians' visits, and treatment expenses.1 Muscle tension dysphonia (MTD) is a common voice disorder characterized by an excess of muscular recruitment during voice production.2 In normal voice production, expiratory airflow sends the small intrinsic muscles of the larynx into vibration; these muscles contract and relax to create vocal fold movement for voice production. Larger extrinsic muscles, such as the suprahyoids and infrahyoids, hold the larynx stable. When MTD occurs, there appears to be an imbalance in the normal tension of the extrinsic and intrinsic laryngeal musculature relationship. Increased tension in the extrinsic muscles causes an improper position of the larynx, which results in tension on the vocal folds and intrinsic muscles. This tension causes difficulty with phonation, swallowing, and breathing.

Muscle tension dysphonia is caused by psychological, social, or physiological problems. The literature recommends inquiring about an individual's emotional status as well as personal stress.2 A recent study by Dietrich and Verdolini Abbott3 showed that infrahyoid muscle activity during the stress phase was significantly correlated with an introverted personality and poor voice-specific quality-of-life (QOL) scores as measured by the Voice Handicap Index (VHI). The intrinsic and extrinsic laryngeal muscles are responsive to emotional triggers and can become hypercontracted easily. Van Houtte et al4 described MTD as a pathological condition in which an excessive tension of the paralaryngeal musculature, caused by a diverse number of etiological factors, leads to a disturbed voice.

Muscle tension dysphonia is typically treated by speech-language pathologists (SLPs). Speech-language pathologists can use different approaches in their treatment but commonly use laryngeal manual therapy and manual circumlaryngeal therapy.5 A review by Mathieson et al6 compared different types of manual therapy delivered by SLPs and found similar vocal outcomes in patients with MTD. This review concluded that, based on limited evidence, laryngeal manual therapy can be a useful primary intervention.

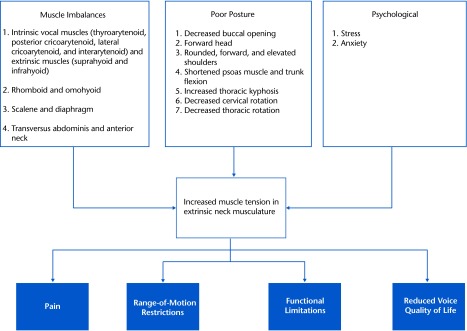

Previous work has suggested that increased muscle tension in the extrinsic neck muscles is the underlying etiology in patients with MTD, which results in restrictions of range of motion (ROM), functional limitations, and reduced voice-specific QOL.1,3,4–6 Three areas can lead to increased muscle tension in the extrinsic neck muscles: muscle imbalances, poor posture, and stress. Lieberman5 recommended that the primary treatment for MTD should be the reduction of tension through a full-body approach over more traditional SLP manual therapy to only the larynx. Lewis et al7 has found that by correcting muscle imbalances, pain decreases and function improves. In people with MTD, the intrinsic and extrinsic muscle imbalances are over the cricothyroid joint. Other muscle imbalances clinically seen in this population are with the rhomboid and omohyoid muscles, the scalene and diaphragm muscles, and the transversus abdominis and anterior neck muscles.

Postural changes in people with MTD include decreased buccal opening; forward head; rounded, forward, or elevated shoulders; shortened psoas muscle and trunk flexion; increased thoracic kyphosis; and decreased cervical or thoracic rotation. Posture has been shown to affect the strength of voice production.4,5 In a study of 18 healthy adults, McLean8 found that simulating normal upright sitting posture had a statistically significant reduction in muscle activity in the posterior neck, sternocleidomastoid, and masseter muscles compared with poor posture (forward head and slouched). Finally, stress and anxiety can lead to muscle tension in the anterior neck.9 Helou et al10 found that the intrinsic laryngeal muscles, which have both sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation, have an elevated level of activation with autonomic nervous system activation.

To date, few studies have examined whether physical therapy is effective for decreasing muscle tension in patients with MTD. Rubin et al11 studied 26 patients and found that a physical therapist and surgeon were well correlated in diagnosing muscle tension. This study concluded that physical therapy proved helpful in the evaluation and treatment of patients with voice problems. Furthermore, one case study showed that physical therapy was beneficial in the treatment of poor posture in a patient with vocal disorders.12 The purpose of this case series was to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of the physical therapist–delivered Vanderbilt Manual Intervention (VMI) in patients with MTD. We hypothesize that the VMI program, consisting of manual therapy, exercise, and stress management education, will improve pain, function, voice-specific QOL, and ROM by reducing muscle imbalances, poor posture, and stress and anxiety (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for the Vanderbilt Manual Intervention program.

Case Description

This case series included adults referred to an outpatient rehabilitation center between June 2011 and November 2011 for treatment of vocal dysfunction caused by muscle tension. Patients had to be at least 18 years of age, English speaking, and referred from an outpatient voice center with a diagnosis of MTD. An otolaryngologist provided a diagnosis of MTD, which includes tension and pain in the anterior neck upon palpation of the larynx and a negative laryngeal videoendoscopy with stroboscopy evaluation. Exclusion criteria for this case series included: (1) polyps or nodules (laryngoscope), (2) spasmodic dysphonia, (3) chronic fatigue syndrome, (4) cicatricial pemphigoid (ie, rare chronic autoimmune disorder), and (5) prior thyroid surgery. Patients' goals for physical therapy were to decrease muscle tension and improve vocal quality. This case series was approved by the institutional review board of the participating site. Eleven patients provided informed consent prior to treatment. An intake assessment was completed that gathered data on demographic and health characteristics.

Procedures/Clinical Impressions

A baseline assessment was performed at the physical therapist evaluation before initiation of the VMI program. Participants were asked questions with regard to marital status, education, employment, comorbidities, smoking status, age, sex, race, and symptoms. Questionnaires measured pain, functional status, and voice-specific QOL. Cervical and jaw ROM also were assessed. This assessment was performed by a physical therapist who was not involved in the delivery of the intervention. After the intervention, patients completed the same questionnaires and ROM tests in the clinic. An exit interview was used to determine patient satisfaction with treatment and adherence to a home exercise program.

Examination

The examination completed by a physical therapist consisted of a semistructured interview (20 minutes) and physical examination (20 minutes). Patients answered questions on past medical history, duration of symptoms, prior treatments received, social support, and mental health. The laryngeal videoendoscopy with stroboscopy was reviewed.

The physical examination assessed muscle imbalances and posture. Muscle imbalances were measured through a strength assessment of the scapula, shoulder, and core muscles, which was based on the work of Kendall et al13 and substitution patterns. More specifically, anterior neck substitution for the rhomboid and transversus abdominis muscles was assessed. Patients were asked to lift an arm and stabilize the scapula and contract abdominal core muscles as the anterior neck was palpated. A plumb line assessed forward head; rounded, forward, or elevated shoulders; trunk flexion, and thoracic kyphosis.

Outcome Measures

Pain.

Pain intensity was assessed with a numeric rating scale (NRS). The NRS is a common measure of pain in clinical settings and consists of a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 being “no pain” and 10 the “worst imaginable pain.” The NRS has been shown to be reliable and valid in patients with musculoskeletal disorders.14 The minimal clinically important change for pain has been identified as 4 points in patients with neck pain.15

Functional status.

Functional status was measured with the Patient-Specific Functional Scale (PSFS). The PSFS assesses change in individual patients rather than comparing disability among individuals.16 Each patient identified 3 tasks and rated them on a 0 to 10 scale, with 0 being “not able to perform the task at all” and 10 being “complete performance.” The same tasks are rated again at the end of treatment. Scores on the three 11-point scales are averaged for a total score. The PSFS with 3 tasks has been shown to be reliable and valid in patients with neck pain.17 The minimal clinically important change for the PSFS has been found to be 2 points in patients with neck symptoms.17

Voice-specific QOL.

Voice-specific QOL was measured with the Voice Handicap Index (VHI). The VHI is a self-perception measure that allows for a quantification of handicap as it relates to voice production.18 Patients rate 30 different vocal tasks on the following scale: never, almost never, sometimes, almost always, and always. The VHI has 3 subscales representing physical (P), functional (F), and emotional (E) domains. Eighteen total points is a clinically meaningful change in this measure with the following severity scale: 0–40 points=mild limitations, 40–60 points=moderate limitations, and 60–120 points=severe limitations.18 The VHI has been shown to be reliable and valid for measuring the self-perceived impact of a voice disorder.19

ROM.

Goniometric measurements were used to assess cervical and jaw ROM. Cervical active ROM measurements were recorded using a goniometer in a sitting position in accordance with the Physical Therapist's Clinical Companion.20 This technique has been shown to be both reliable and valid in patients with nonspecific neck pain.21 Cervical ROM with a goniometer also has been found to be moderately correlated with radiograph and three-dimensional kinematic measurements.22 Jaw ROM was assessed using mouth-opening measurements by asking the patients to open their mouth as wide as they can and then measuring from the top of the incisors to the bottom of the top teeth. The therapist would mark the opening amount along a tongue depressor (ie, blade) and then record measurements with a tape measure. This simplified clinical method has been found to be reliable and valid through moderate correlations with mandibular kinesiography.23

Feasibility.

Due to the novelty of our physical therapist–delivered VMI program for patients with MTD, the feasibility of therapist training and delivery of the intervention was assessed. A physical therapist with 2 years of experience in manual therapy and 15 years of experience as a therapist delivered the intervention. The therapist had no prior training for treating patients with voice issues. Formal training included a 7-hour session with a senior physical therapist who had 4 years of experience treating patients with voice disorders caused by muscle tension. Feasibility of the training was determined through written and skills competency tests (ie, scores >85% on both tests). Feasibility and fidelity of the intervention were monitored through patient exit interviews and a therapist checklist. Patients were asked to rate each exercise and manual therapy technique on a scale of 0 to 100, with 100 being “extremely helpful” and 0 being “not helpful at all.” Direct observation by the senior therapist to assess therapist adherence to the intervention protocol (ie, a checklist) also occurred. Finally, adverse events were monitored and recorded by the treating therapist.

Clinical Impression

All patients who consented to participate in the case series were deemed appropriate for the target intervention based on the patient interview and objective assessment of muscle imbalances and posture during the evaluation. The hypothesis was that patients with MTD would have a reduction in pain and improvement in functional status, voice-specific QOL, and cervical and jaw ROM following the VMI program.

Intervention

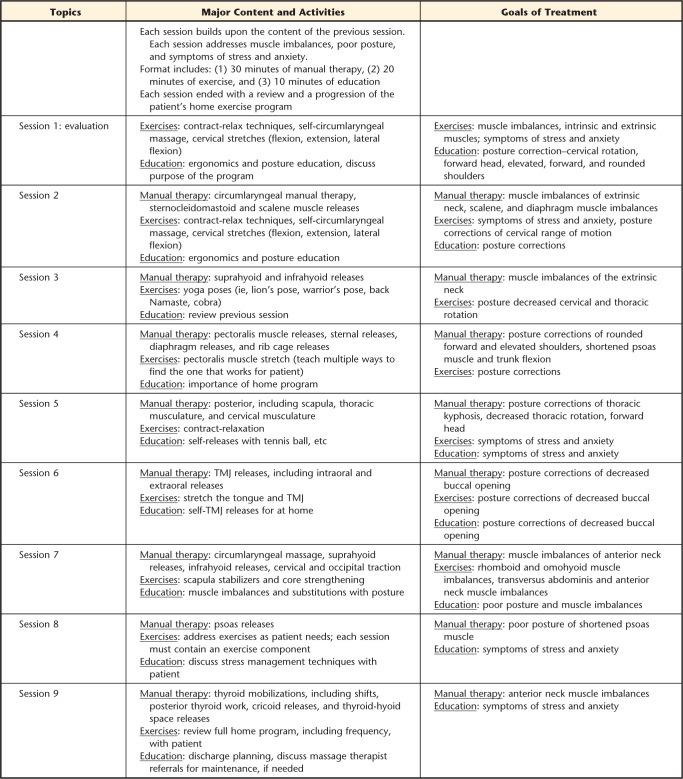

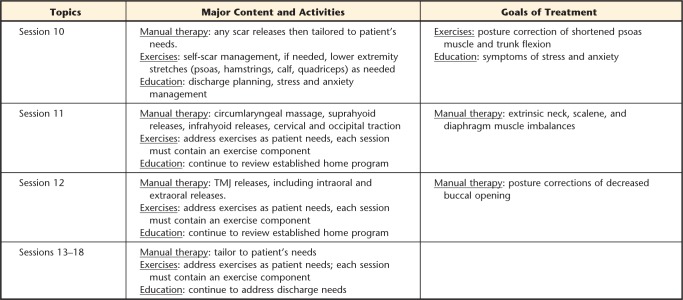

The VMI program is a structured, manual-based intervention that was designed to address muscle imbalances, poor posture, and symptoms of stress in patients with MTD. The program focuses on empirically supported manual therapy techniques, exercises, and education for relaxation and stress management.3–9,24,25 Patients received sessions 2 times a week for 9 weeks with a study therapist. All sessions were 60 minutes in length.

The first session was an evaluation, and patients were instructed in a home exercise program that consisted of contract-relax techniques (ie, progressive relaxation techniques for the full body starting with the legs and progressing to the face), cervical stretches, and self-manual therapy (teaching circumlaryngeal massage as a combination described by Mathieson et al6). Patients also were instructed on ergonomics and proper posture. The remaining sessions included 30 minutes of manual therapy, based on the work of Lieberman5 and Aronson,26 that addressed the laryngeal region, posterior cervical and scapula muscles, jaw and tongue, muscles that attach to the rib cage (ie, diaphragm and latissimus muscle), and hip flexors; 20 minutes of exercise; and 10 minutes of education on relaxation, stress management, ergonomics, or posture for speaking, sleeping, and activities of daily living (see Appendix for content and goals of treatment). Sessions ended with a review and progression of a patient's home exercise program. Patients received a standardized exercise program that consisted of contract-relax exercises; self-circumlaryngeal manual therapy; neck, chest, and jaw stretches; scapula stabilization; core strengthening yoga poses; and therapeutic massager or tennis ball trigger point release (Appendix). Patients were given written and pictorial instructions for each of the home exercises.

Outcome

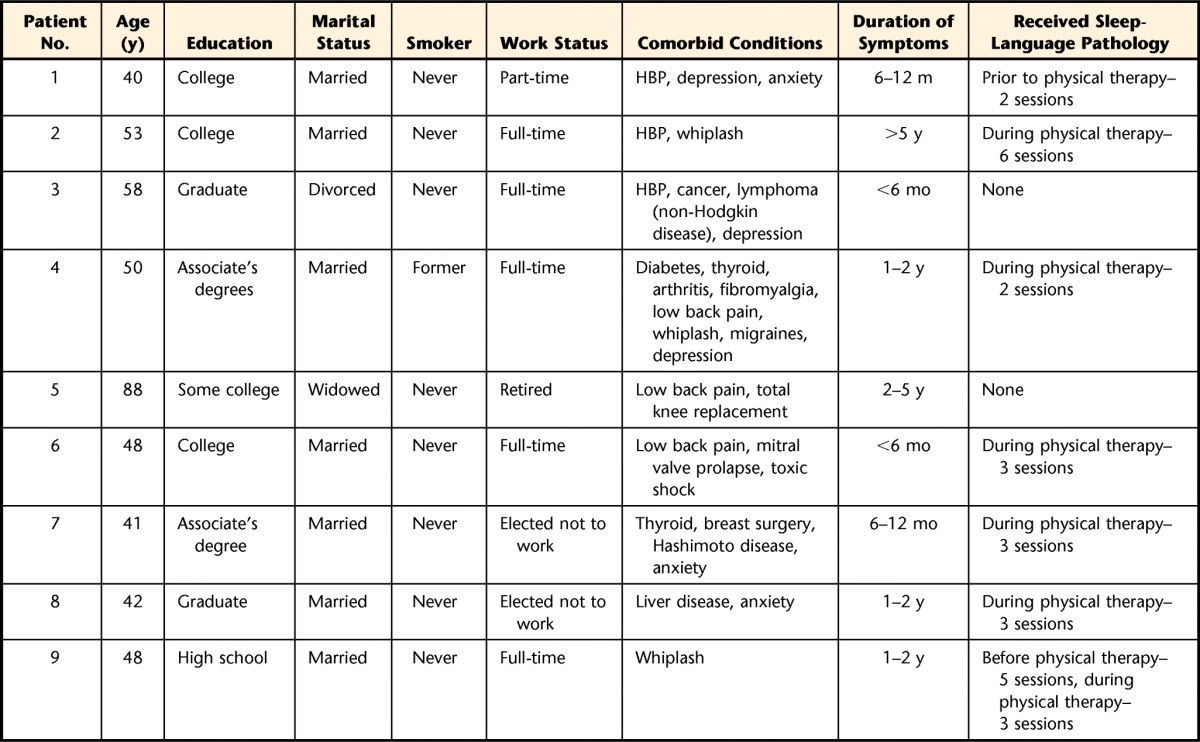

Out of 11 patients who consented to participate in this case series, 9 completed a minimum of 9 sessions. The average number of visits was 13.4 (SD=2.7). There were no adverse events. Two patients did not attend their last scheduled appointment to complete the VHI posttreatment assessment. During the intervention phase, 6 patients also were seen by an SLP. Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Muscle Tension Dysphoniaa

All patients were white, female, and had chief complaints of muscle tension and vocal problems. HBP=high blood pressure.

The therapist passed the written and skills tests with scores greater than 90%. Exit interviews showed that 8 patients were extremely satisfied with the program. Treating therapist and senior therapist checklists demonstrated at least 90% of the VMI manual therapy components were delivered each session. Eight patients received at least 90% of the home program exercise components, and 1 patient received 80%. Patient 5 was consistently late to sessions and had difficulty with home exercise program adherence.

The exit interview showed that all patients rated the manual therapy techniques as 80% helpful or above, with the exception of patient 5, who rated circumlaryngeal and jaw manual therapy as 70% helpful. Exercises were rated as 70% helpful or above except for those focusing on the lower extremities. However, patient 1 rated relaxation as 50% helpful and yoga and stress management education as 20% and 50% helpful, respectively. Patient 2 provided the following comment: “The VMI program made me more aware of my voice issue and that muscle tension, even in my jaw, plays a part. I never realized the full extent of my issues until I tried this therapy.”

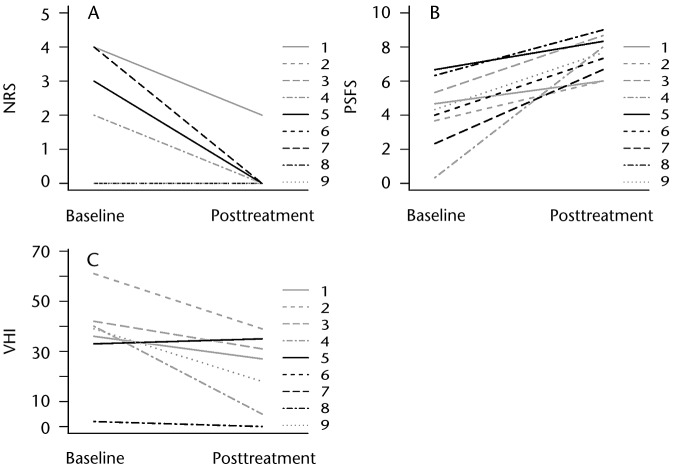

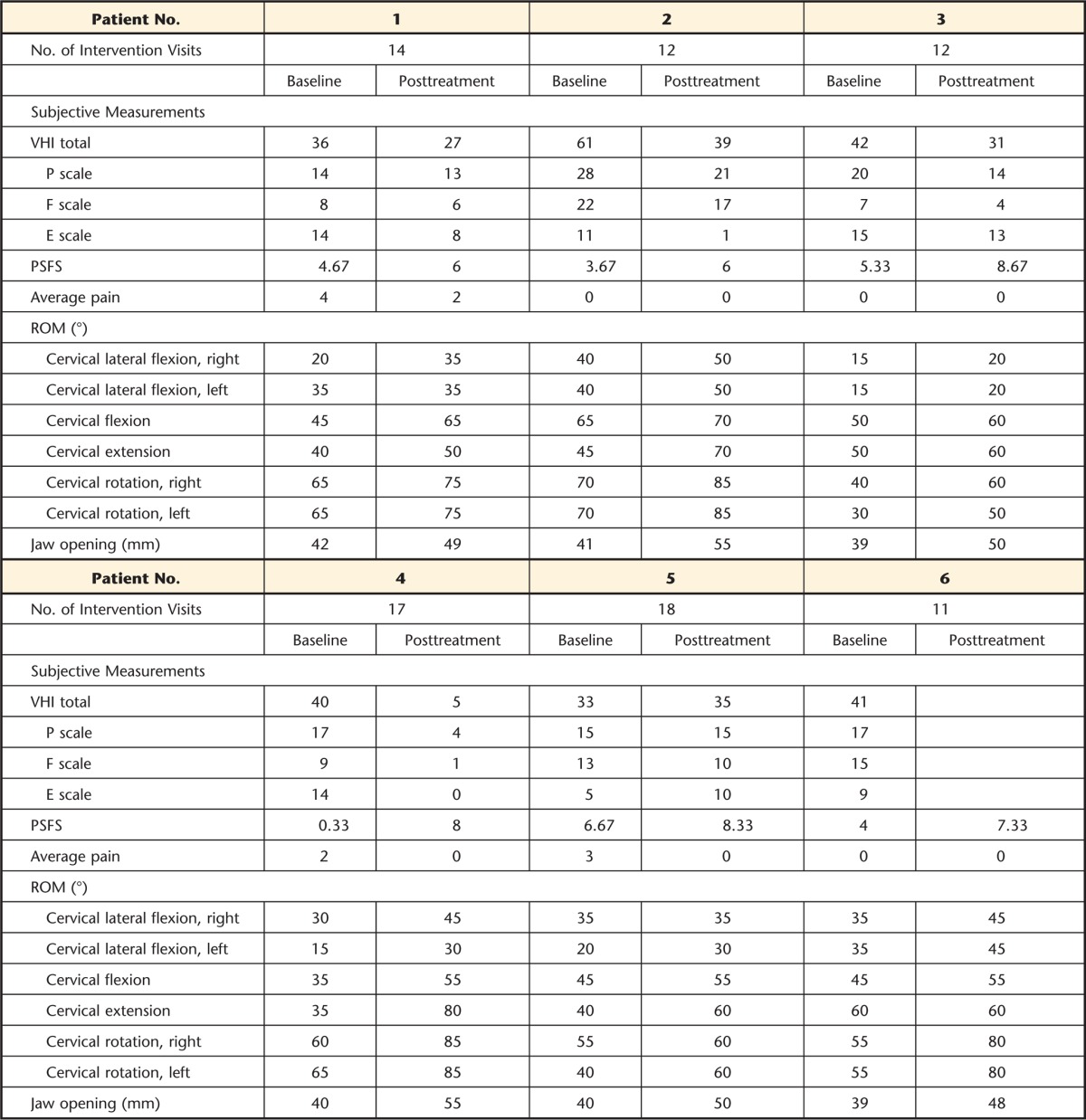

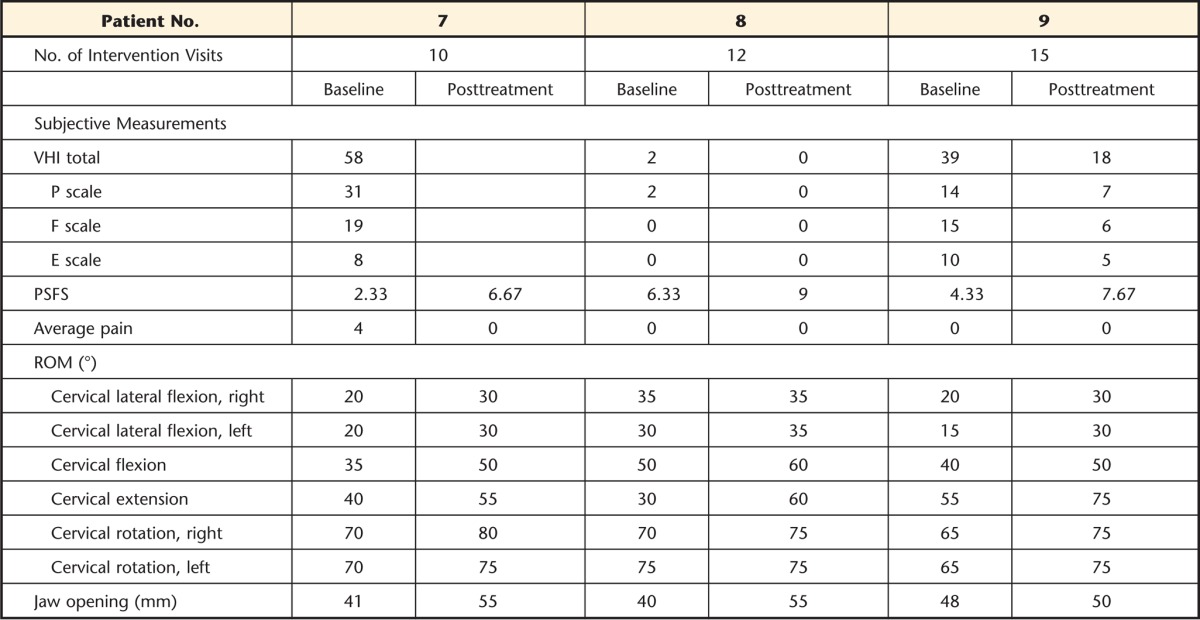

Patients 1, 4, 5, and 7 reported mild pain at baseline, and patients 2, 3, 6, 8, and 9 had no pain at the start of the intervention (Tab. 2). After treatment, all patients except patient 1 reported no pain. Patient 7 had a clinically relevant reduction in pain (Fig. 2A). All patients had an improvement in PSFS score (Tab. 2). Patients 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, and 9 exceeded a clinically meaningful improvement in PSFS at the conclusion of the intervention (Fig. 2B).

Table 2.

Individual Outcomes for Patients at Baseline and Completion of Interventiona

VHI=Voice Handicap Index, PSFS=Patient-Specific Functional Scale, ROM=range of motion.

Figure 2.

Numeric rating scale (NRS) score for pain intensity, Patient-Specific Functional Scale (PSFS) score, and Voice Handicap Index (VHI) score at baseline and completion of intervention.

Patients 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, and 9 had a decrease in VHI, whereas patient 5 had a 2-point increase (Tab. 2). Patients 2, 4, and 9 exceeded a clinical meaningful change on the VHI (Fig. 2C). Patients 6 and 7 did not attend their last scheduled appointment to obtain discharge VHI. Both patients reported their voice was improving. Patients 1, 3, and 4 had a decrease in the emotional scale (E scale) of the VHI, with patients 1, 3, 4, 7, and 8 reporting emotional and psychological risk factors at the start of the intervention.

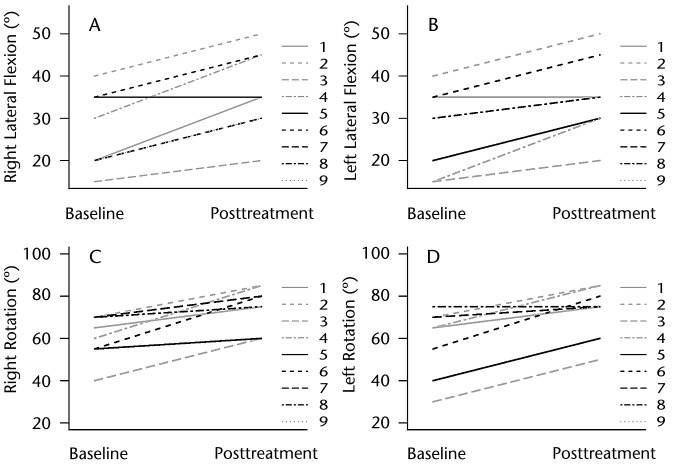

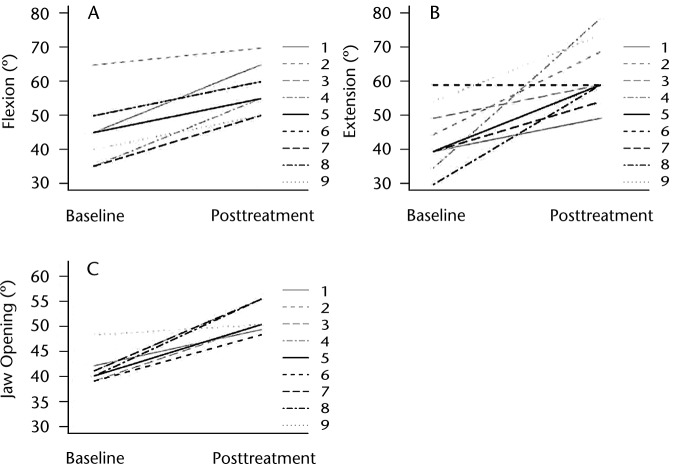

Patients 2, 3, 4, 6, and 7 had at least 5 degrees of improvement in lateral flexion in both directions (Figs. 3A and 3B). Patients 1, 5, and 8 showed at least 5 degrees of improvement in one direction. All patients improved in cervical rotation by at least 5 degrees in both directions, except patient 8, who remained at 75 degrees posttreatment with left cervical rotation (Fig. 3C and 3D). Patients improved in cervical flexion by at least 10 degrees (Fig. 4A). Patient 6 demonstrated no improvement in cervical extension, whereas the remaining 8 patients improved by at least 10 degrees (Fig. 4B). All patients had improvement in jaw opening, with patients 4 and 8 having the largest improvement in jaw opening at 15 mm (Fig. 4C).

Figure 3.

Cervical range of motion (left and right lateral flexion and rotation) at baseline and completion of intervention.

Figure 4.

Cervical (flexion and extension) and jaw range of motion at baseline and completion of intervention.

Discussion

The findings of this case series demonstrate that a physical therapy program consisting of manual therapy, exercise, and stress management is feasible in patients with MTD. Furthermore, preliminary findings suggest that the VMI intervention improves patient outcomes related to pain, functional status, voice-specific QOL, and ROM. Based on insurance limitations and time limitations of SLPs, physical therapy can be a discipline to help address muscle tension in people with voice disorders.

Four of the 9 patients had mild pain at baseline. Pain does not appear to be a primary complaint of MTD, which is consistent with previous studies1–6,11,12 and not surprising based on the underlying etiology (ie, increased muscle tension) of this condition. Patient 1 was the only one with pain at the conclusion of treatment, which the patient reported was related to a “grinding” sensation.

Improvement in functional status appeared clinically meaningful in 7 of the 9 patients, exceeding published values of 2 points on the PSFS at treatment completion.17 This finding may have been due to the VMI program's focus on reduction of muscle tension in the neck and jaw as well as the shoulder, chest, rib cage, and psoas muscle; strengthening and endurance exercises such as yoga; and scapula and core stabilization exercises. Previous work has suggested that excess muscle tension results in significant disability and functional limitations in patients with MTD.1–6 Lieberman5 recommended that the primary focus of treatment for MTD should be the reduction of tension of the vocal folds through a full-body approach.

This broad approach combines anterior neck manual therapy with manual therapy to the posterior neck muscles (ie, upper trapezius and spinalis capitis and cervicis), thoracic musculature (ie, paraspinals, quadratus lumborum, and serratus), temporomandibular joint (ie, pterygoid and masseter), rib cage intercostal muscles, and diaphragm release in addition to exercises including posture and relaxation. This case series suggests that a broader manual therapy and exercise approach than just treatment to the anterior neck has the potential to improve outcomes in people with MTD. This conclusion is consistent with the findings of a case study by Staes et al12 that included abdominal muscles stabilization, scapula strengthening, postural alignment, and cervical mobility exercises as well as masseter massage to improve voice parameters in a 26-year-old female opera singer.12 Rubin et al11 also found that a broad physical therapy approach proved helpful in the management of 26 patients with voice problems.

Patients had larger gains than expected in voice-specific QOL following the VMI treatment, with 3 patients demonstrating a clinically meaningful change of 18 points on the VHI. The E scale of the VHI had the least amount of change among the patients. Although this program briefly educates the patient on stress management, it does not focus on emotional aspects of the voice. Research has discussed the connection between MTD and personality, anxiety, and psychological disorders.3,4 A stronger “psychologically informed” rehabilitation approach may be needed in the VMI program to address stress and anxiety in this patient population.27

Johnson and Skinner28 suggested that full cervical ROM, as seen in good posture alignment, is beneficial for vocal sound, especially movement of the upper cervical vertebra. In our case series, all patients improved in cervical flexion and at least one direction of lateral flexion and rotation. One patient remained at 60 degrees of cervical extension; all other patients had at least 10 degrees of improvement in cervical extension. Lack of jaw opening has been correlated with hoarseness in teachers, although specific measurements of what correlates “good” jaw opening have not been shown.29 When the jaw is relaxed, it is assumed that vocal output is easier and, therefore, causes less tension in the neck. All patients showed moderate improvement in jaw opening with VMI.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, we used a case series design. A control group was not used, and statistical testing was not performed. Thus, the findings may be attributed to chance. Second, we are unable to determine whether improvement in outcomes was a direct result of the VMI intervention or due to other patient factors, such as emotional, psychosocial, and SLP treatment. A next step would be to compare the efficacy of the VMI intervention with a control group through a randomized clinical trial design. Third, patient assessment occurred at the completion of the VMI intervention, and longer follow-up is needed to assess maintenance of treatment gains. Finally, all patients were female and white, which limits the generalizability of our findings.

Implications for Practice and Future Research

This case series suggests that physical therapists can implement the manual therapy skills, exercise, and education necessary to effect improvement in outcomes for patients with MTD.

A broad manual therapy and exercise approach has the potential to address the underlying etiology of MTD (ie, muscle tension), which may lead to a decrease in pain and improvement in ROM, physical functioning, and voice-specific QOL. However, a randomized clinical trial is needed to confirm the findings of this case series and the efficacy of the VMI intervention. Clinical implications of this study include broadening the availability of physical therapy techniques to patients with MTD and the scope of physical therapy to encompass patient referral from outpatient voice centers. Screening for emotional and psychosocial risk factors and incorporating stress management into rehabilitation also are encouraged in order to improve outcomes in patients with MTD.

Appendix.

Appendix.

Intervention and Treatment Goals by Sessiona

a TMJ=temporomandibular joint.

Footnotes

Both authors provided concept/idea/project design and writing. Ms Tomlinson provided data collection, project management, participants, and facilities/equipment. Dr Archer provided data analysis. The authors thank the director and physical therapists at the Vanderbilt Dayani Center and the Vanderbilt Voice Center physicians, speech-language pathologists, and singing voice specialists, especially Jennifer Craig, MS, CCC-SLP.

This case report appeared as a poster presentation at the Combined Sections Meeting of the American Physical Therapy Association; January 21–24, 2013; San Diego, California; and at the Fall Voice Conference; October 24–25, 2014; San Antonio, Texas.

This case series used REDCap as the secure database, which was supported by CTSA award no. UL1TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1. Roy N, Merrill RM, Gray SD, Smith EM. Voice disorders in the general population: prevalence, risk factors, and occupational impact. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1988–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roy N, Bless DM, Heisey D, Ford CN. Manual circumlaryngeal therapy for functional dysphonia: an evaluation of short- and long-term treatment outcomes. J Voice. 1997;11:321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dietrich M, Verdolini Abbott K. Vocal function in introverts and extraverts during a psychological stress reactivity protocol. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2012;55:973–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Van Houtte E, Van Lierde K, Claeys S. Pathophysiology and treatment of muscle tension dysphonia: a review of the current knowledge. J Voice. 2011;25:202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lieberman J. Principles and techniques of manual therapy: application in the management of dysphonia. In: Harris T, Harris S, Rubin JS, Howard DM, eds. The Voice Clinic Handbook. New York, NY: Whurr Publishers; 2002:91–138. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mathieson L, Hirani SP, Epstein R, et al. Laryngeal manual therapy: a preliminary study to examine its treatment effects in the management of muscle tension dysphonia. J Voice. 2009;23:353–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lewis CL, Sahrmann SA, Moran DW. Effect of position and alteration in synergist muscle force contribution on hip forces when performing hip strengthening exercises. Clin Biomech. 2009;24:35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McLean L. The effect of postural correction on muscle activation amplitudes recorded from the cervicobrachial region. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2005;15:527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ng JH, Lo S, Lim F, et al. Association between anxiety, type A personality, and treatment outcome of dysphonia due to benign causes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;1:96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Helou LB, Wang W, Ashmore RC, et al. Intrinsic laryngeal muscle activity in response to autonomic nervous system activation. Laryngoscope. 2013;11:2756–2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rubin JS, Blake E, Mathieson L. Musculoskeletal patterns in patients with voice disorders. J Voice. 2007;21:477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Staes FF, Jansen L, Vilette A, et al. Physical therapy as a means to optimize posture and voice parameters in student classical singers: a case report. J Voice. 2011;25:e91–e101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG. Muscles, Testing and Function, With Posture and Pain. 4th ed Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cleland JA, Childs JD, Whitman JM. Psychometric properties of the Neck Disability Index and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in patients with mechanical neck pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kovacs FM, Abraira V, Royuela A, et al. Minimum detectable and minimal clinically important changes for pain in patients with nonspecific neck pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Donnelly C, Carswell A. Individualized outcome measures: a review of the literature. Can J Occup Ther. 2002;69:84–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cleland JA, Fritz JM, Whitman JM, et al. The reliability and construct validity of the Neck Disability Index and Patient Specific Functional Scale in patients with cervical radiculopathy. Spine. 2006;31:598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jacobson BH, Johnson A, Grywalski C, et al. The Voice Handicap Index (VHI): development and validation. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1997;6:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bogaardt HC, Hakkesteegt MM, Grolman W, et al. Validation of the Voice Handicap Index using Rasch analysis. J Voice. 2007;21:337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Physical Therapist's Clinical Companion. Vol 3 Springhouse, PA: Springhouse Corporation; 2000. Springhouse Clinical Companion Series. [Google Scholar]

- 21. de Koning CH, van den Heuvel SP, Staal JB, et al. Clinimetric evaluation of methods to measure muscle functioning in patients with non-specific neck pain: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Antonaci F, Ghirmai S, Bono G, et al. Current methods for cervical spine movement evaluation: a review. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18(2 suppl 19):S45–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rivera-Morales WC, Goldman BM, Jackson RS. Simplified technique to measure mandibular range of motion. J Prosthet Dent. 1996;75:56–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Emerich KA. Nontraditional tools helpful in the treatment of certain types of voice disturbances. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;11:149–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marszalek S, Niebudek-Bogusz E, Woznicka E, et al. Assessment of the influence of osteopathic myofascial techniques on normalization of the vocal tract functions in patients with occupational dysphonia. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2012;25:225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aronson AE. Clinical Voice Disorders. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Main CJ, George SZ. Psychologically informed practice for management of low back pain: future directions in practice and research. Phys Ther. 2011;91:820–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johnson G, Skinner M. The demands of professional opera singing on cranio-cervical posture. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:562–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ferreira LP, de Oliveira Latorre Mdo R, Pinto Giannini SP, et al. Influence of abusive vocal habits, hydration, mastication, and sleep in the occurrence of vocal symptoms in teachers. J Voice. 2010;24:86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]