Summary

Fluoroscopic images for comparison (FICs) can be easily obtained for follow-up on an outpatient basis. This study retrospectively assessed the diagnostic performance of a set of FICs for evaluation of recanalization after stent-assisted coiling, with digital subtraction angiography (DSA) as the reference standard. A total of 124 patients harboring 144 stent-assisted coiled aneurysms were included. At least one month postembolization they underwent follow-up angiograms comprising a routine frontal and lateral DSA and a working-angle DSA. For analysis, FICs should be compared with the mask images of postprocedural DSAs to find recanalization. Instead of FIC acquisition, the mask images of follow-up DSAs were taken as a substitute because of the same view-making processes as FICs, full availability, and perfect coincidence with follow-up DSAs. Two independent readers evaluated a set of 169 FICs and DSA images for the presence of recanalization one month apart. Sensitivity, specificity, and interreader agreement were determined. Recanalization occurred in 24 (14.2%) cases. Of these, nine (5.3%) cases were found to have significant recanalization in need of retreatment. Sensitivity and specificity rates were 79.2% (19 of 24) and 95.9% (139 of 145) respectively for reader 1, and 66.7% (16 of 24) and 97.9% (142 of 145) for reader 2. Minimal recanalization was identified in seven out of all eight false negative cases. Excluding minimally recanalized cases in no need for retreatment from the recanalization group, calculation resulted in high sensitivity and specificity of over 94% for both readers. Interreader agreement between the two readers was excellent (96.4%; κ = 0.84). FICs may be a good imaging modality to detect significant recanalization of stent-assisted coiled aneurysms.

Keywords: intracranial aneurysm, embolization, intracranial stent, follow-up studies, fluoroscopy

Introduction

Since the advent of Guglielmi detachable coils in the mid-1990s, the indications for endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms have widened to encompass some complex aneurysms 1-2. Supercompliant balloon catheters 3-4 and self-expanding stents 5-7 have played a crucial role and other innovative devices and technologies are continuously developing, being added to the armamentarium of the endovascular field. However, the relatively shorter durability of endovascular coiling necessitates regular follow-up imaging studies of coiled patients and, if necessary, retreatment 8,9. Finding significant recanalization after coiling will be an important task for physicians who perform the treatment. They examine the patients for several years using either conventional angiography or noninvasive time-of-flight MRA (TOF-MRA). Most unstented coiled patients are properly indicated for follow-up TOF-MRA. High sensitivity and specificity make it an alluring follow-up tool along with shorter scanning time and noninvasiveness compared to conventional angiography 10,11.

On the other hand, stent-assisted coiled patients are currently reserved for conventional angiography for follow-up because stent metal artifacts prevent a complete evaluation of the stented arteries and aneurysms. However, conventional angiography is not without risk: neurologic complications and permanent neurologic deficits occur in 0.4-12% and 0.5-5% 12-14, respectively. The patients also need to be admitted to hospital and endure a substantial emotional and economic burden. Nevertheless, there is still no non-invasive substitute for conventional angiography to follow stent-assisted coiled patients. Only a few reports have suggested the feasibility of contrast-enhanced MRA or time-resolved imaging of contrast kinetics MRA (TRICKS MRA) for follow-up imaging of stent-assisted coiled aneurysms 15,16.

No matter which devices and techniques have been used during procedures, the authors take every coiled patient to the angiography suite at least once within the first six months postembolization to obtain a set of fluoroscopic images for comparison (FICs), including magnified working-angle fluoroscopic images (WFICs) and routine frontal (FFICs) and lateral fluoroscopic images (LFICs). Thus, a set of FICs are matched and compared with the mask images of completion DSAs of previous procedures to detect any findings of recanalization. Empirically, it is not uncommon to find those findings in practice in case of recanalization, but only one study has tested the potential role of a set of FICs in the diagnosis of recanalization after unstented coiling of cerebral aneurysms 17. The authors herein evaluated the diagnostic performance of FICs for detection of recanalization of stent-assisted coiled aneurysms. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first investigation in the English literature on the potential role of FICs to find recanalized aneurysms in such a specific group.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This study was approved by the local ethics review board and written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Two institutions took part in this study. They retrospectively searched for consecutive stent-assisted coiled cases from their own registry data and included cases when follow-up cerebral angiography was performed at least one month after treatment. Both institutions had a common protocol that follow-up cerebral angiography was composed of routine frontal and lateral DSAs and magnified working-angle DSAs of the involved artery and every DSA run had both a mask image and a series of subtracted images. For data analysis, available FICs should be compared with the mask images of procedural completion DSAs to disclose any changes in coils pertaining to recanalization. Instead of FIC acquisition, the mask images of follow-up DSAs were taken as a substitute because of the same view-making processes as FICs, full availability, and perfect coincidence with follow-up DSAs, the reference standard. Most importantly, the view-making processes did not differ for both follow-up FICs and follow-up DSAs: referring to the mask images of procedural completion DSAs displayed on operating monitors, each view, including working-angle and routine frontal and lateral views, was set by tuning fluoroscopic bony landmarks to those of the procedural mask images regardless of procedural angle values or coil shapes. Apparently, FICs and the mask images of DSAs were the same for image view and quality, so that the results in this study would be applicable to FICs easily obtained on an outpatient basis. Cases of dissecting aneurysms, different views, and lack of either WFICs or both components (frontal and lateral) of routine FICs were excluded. By the above criteria, a total of 124 patients (age range, 21-72 years; mean, 55) with 142 aneurysms (size range, 1.4-28.1 mm; mean, 6.6; median, 5.75) were included, of which two aneurysms had repeat embolization during follow-up, so the number of inclusion cases totaled 144. Another six cases initially underwent repeat embolization for recanalization, so the total number of repeat embolizations was eight out of 144 cases (6%). A hundred and nine cases were incidentally found and 35 other cases presented with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Selecting one of the available self-expanding stents, including Neuroform, Enterprise, and Solitaire, was at the discretion of the practitioner, and Y-configuration stenting by use of two stents was performed in eight (5.6%) cases. During follow-up, a set of 169 FICs and DSA images (range, 2 - 57 months; mean, 14.6±10.4; median, 12) were obtained for 144 cases: only one follow-up in 122 cases, two in 20, three in one, and four in one.

Image Analysis

Two readers (reader 1; BJK with 13 years' experience, reader 2; CKJ with six years' experience in neurointervention) blinded to all clinical information reviewed a set of 169 follow-up FICs independently and in random order, and a set of 169 DSAs one month later. A set of FICs was composed of WFICs and FFICs and/or LFICs at one follow-up, each of which should be compared with the same type of procedural mask images. In every case, all sets of FICs and DSA images were arranged in types (magnified working-angle, routine frontal, and routine lateral views) and consecutive order, if two or more sets existed. When a set of FICs was analyzed, a procedural magnified working-angle DSA image preembolization and postembolization was given to provide anatomic references.

For FICs, the readers determined the presence or absence of recanalization by the findings of compaction, loosening, or both of coil masses. When those findings already existed, any increase in those findings was considered positive at the next follow-up. For DSAs, the grading scale of Raymond et al. 18 was evaluated for all procedures. At follow-up, any changes in intraaneurysmal contrast filling were assessed: new intraaneurysmal contrast filling or any increase in filling was defined as recanalization and any decrease was considered progressive thrombosis. In case of recanalization, the need for retreatment was also evaluated in the light of potential risks of future growth and technical feasibility. DSA results were the reference standard for recanalization and retreatment, so that any discrepancies on both were resolved by consensus of the two readers.

Statistical Analysis

Data collected were analyzed with a statistical software package (SPSS 9.0; SPSS, Chicago, ILL, USA) using descriptive statistical tools and by means of parametric and nonparametric tests, depending on data patterns. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of FICs for detection of recanalization were calculated. Results were considered true-positive when FICs showed compaction, loosening, or both of coil masses and recanalization was confirmed with the reference standard. Results were considered true-negative when neither FICs and nor the reference standard demonstrated any findings or evidence of recanalization. False positive results were considered when the findings of recanalization were present on FICs but were not found with the reference standard. Finally, false negative results were considered when FICs failed to show the findings of recanalization present with the reference standard.

Agreement between the two readers utilizing the k statistic was determined. Strength of agreement was judged to be poor (κ= 0.00-0.20), fair (κ= 0.21-0.40), moderate (κ= 0.41-0.60), good (κ= 0.61-0.80), or excellent (κ= 0.81-1.00).

Results

The two readers disagreed on the initial angiographic grading scale in 48 of 144 aneurysms (33%). Of the agreed 96 cases, complete occlusion, residual neck, and residual aneurysm were demonstrated in 76 (79.1%), 11 (11.5%), and nine (9.4%), respectively. During follow-up, recanalization occurred in 24 (14.2%) cases, while progressive thrombosis was found in 33 cases (19.5%). Of the recanalized cases, nine (5.3%) cases were found to need retreatment (Figure 1).

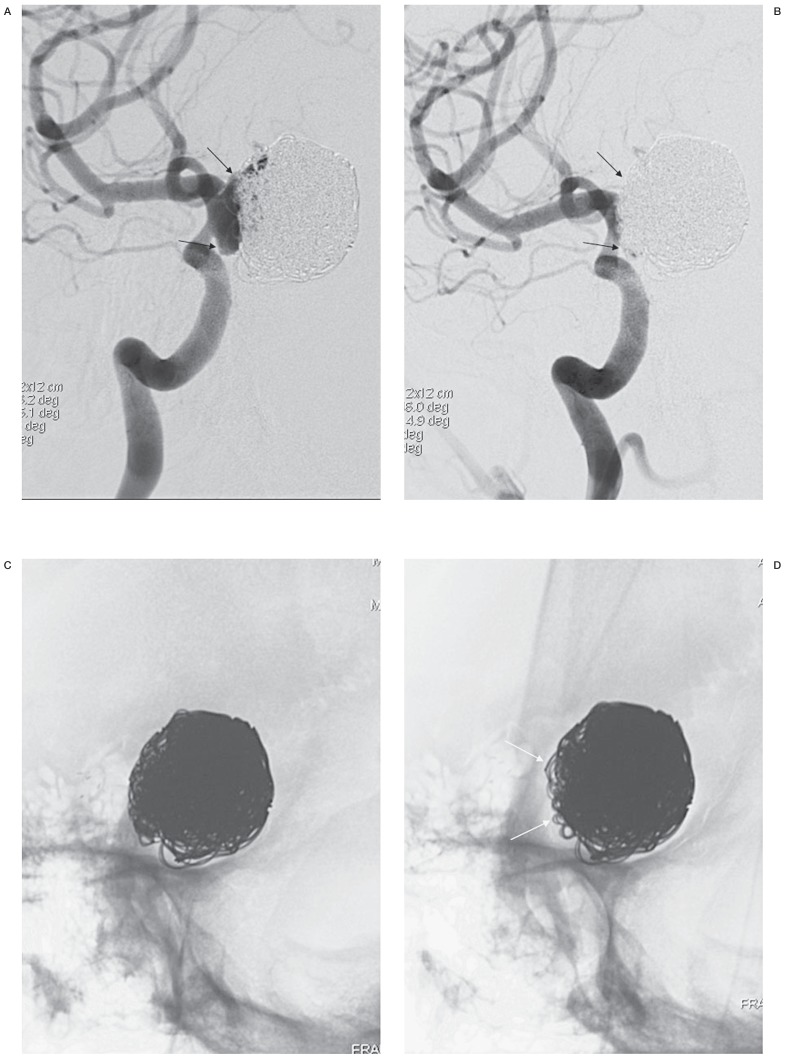

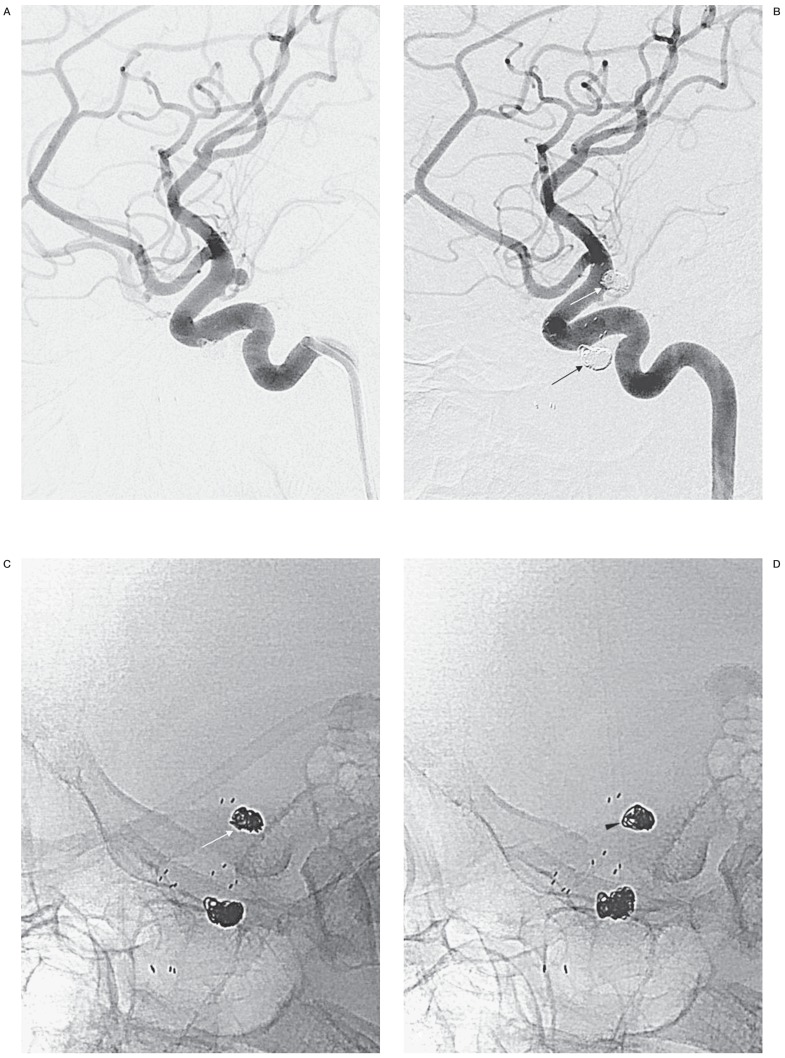

Figure 1.

A true-positive case of recanalization needing retreatment after repeat embolization of a giant aneurysm. Both working-angle angiograms preembolization (A) and postembolization (B) are given to provide anatomic information when FICs are evaluated. A large recanalized sac is well demonstrated and packed with stent-assisted coiling (black arrows). A mask image of working-angle completion DSA (C) is sequentially compared with the mask images of follow-up DSAs, a substitute for FICs. A set of FICs consists of a working-angle FIC and a routine frontal FIC (not shown) and/or a lateral FIC (not shown). D) At 4 months, there is a finding of recanalization, loosening of the coil mass (white arrows), which was agreed by both readers. E) At 8 months, no change in the coil mass is found in this image, but frontal FIC demonstrates aggravated loosening (not shown), which was missed by one reader, leading both readers to disagree on recanalization. Angiograms at 4 months (F) and 8 months (G), the reference standard, confirm recanalization with respective new and increased contrast filling in the aneurysm (open arrows). Each recanalization was thought to need retreatment by both readers.

In eight cases (5.6%), Y-configuration stenting was performed to preserve branches arising from wide-necked bifurcation aneurysms or to rescue coil protrusion. None of these aneurysms was recanalized during follow-up. In-stent significant stenosis of more than 50% was found in only two cases (57% and 82%), which occurred commonly in the ophthalmic ICA segment between the clinoid process and the PcomA. Both were asymptomatic but the case of an 82% in-stent stenosis underwent angioplasty for the prevention of future stroke. At 12 months after angioplasty, the patient still had no in-stent restenosis on follow-up angiograms and no symptoms and signs on neurologic examinations.

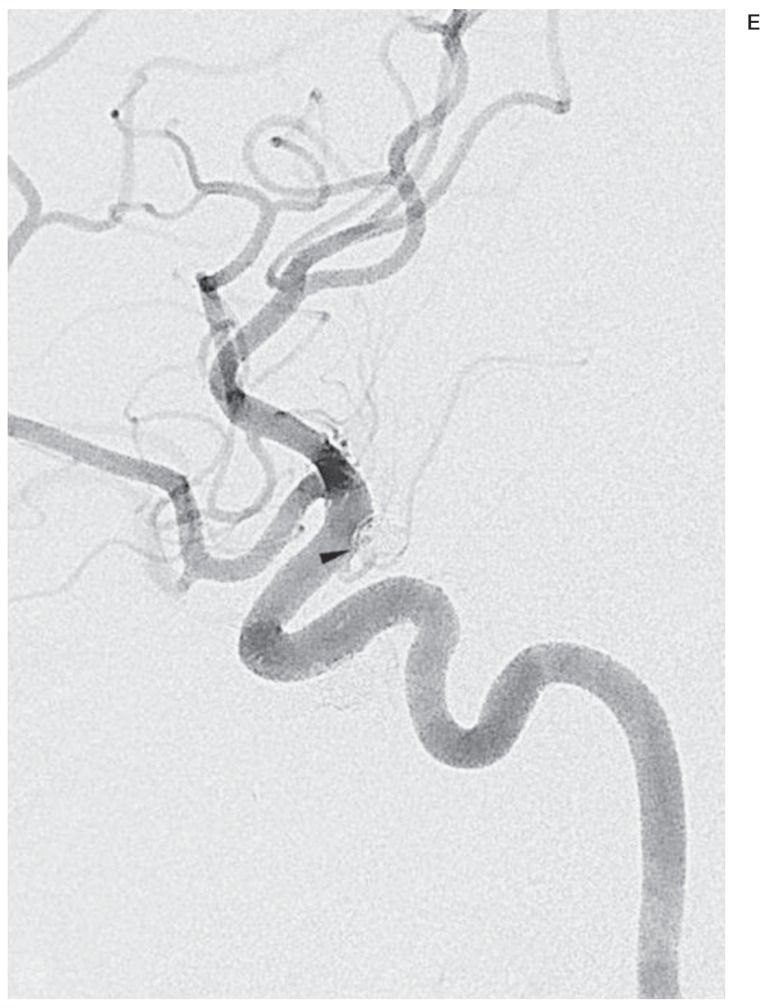

The respective sensitivity and specificity for the presence of recanalization were 79.2% (19 of 24) and 95.9% (139 of 145) for reader 1, and 66.7% (16 of 24) and 97.9% (142 of 145) for reader 2. Five and eight cases were false negative for readers 1 and 2, respectively, and the eight cases comprised the former five and three other cases. Of these eight, seven had new or minimally increased intraaneurysmal contrast filling that did not need retreatment (Figure 2), and the remaining one needed retreatment but was missed by only reader 2 (Figure 1E,G). Six and three cases were false positive for readers 1 and 2, respectively, and the six cases comprised the latter three and three other cases. All three cases pertaining to both readers had loosening of coil masses but no contrast filling on DSA images. In one case, a procedural complication of aneurysm perforation led to coil placement outside and inside the aneurysm to quickly stop bleeding, while the other two had no specific event. Three other cases for only reader 1 were all associated with misreading protruded neck-covering coils put in place over time as recanalization (Figure 3). Respective positive and negative predictive values were 76% (19 of 25) and 96.5% (139 of 144) for reader 1, and 84.2% (16 of 19) and 94.7% (142 of 150) for reader 2. If recanalization was redefined as coil compaction or loosening only in need for retreatment, the seven false negative cases of minimal recanalization should be reclassified so that respective sensitivity and specificity would rise to 100% and 96% for reader 1, and 94.1% and 98% for reader 2. Interreader agreement between the two readers was excellent (96.4%; κ= 0.84).

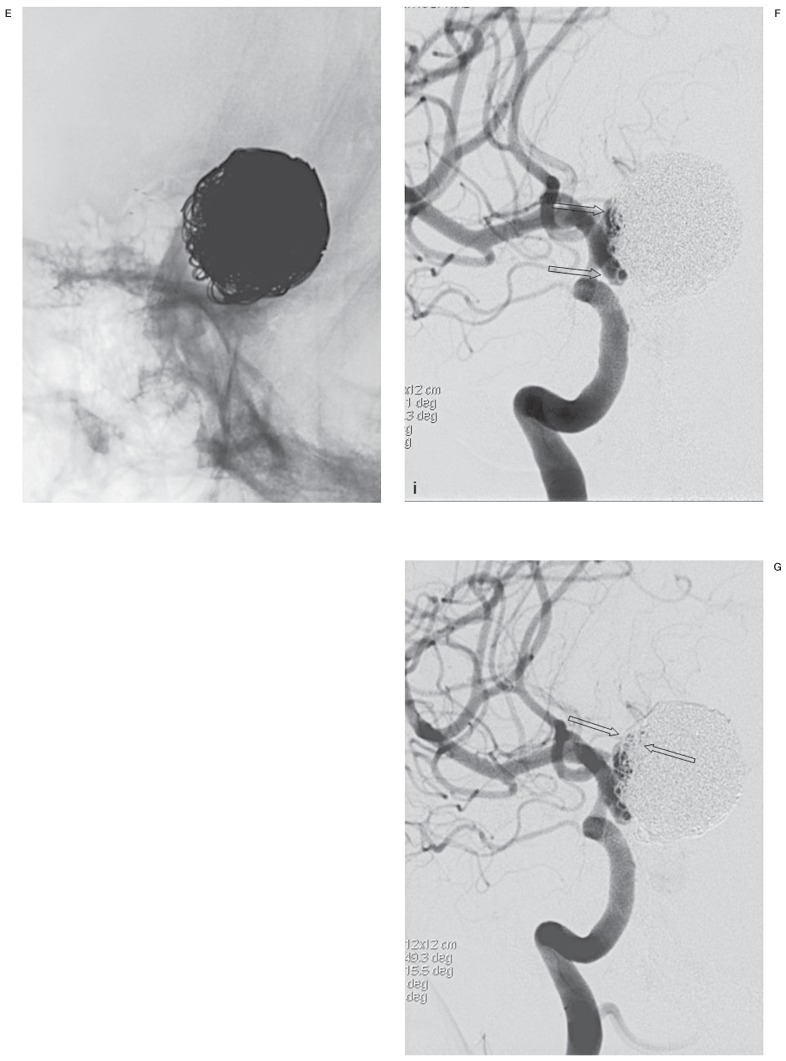

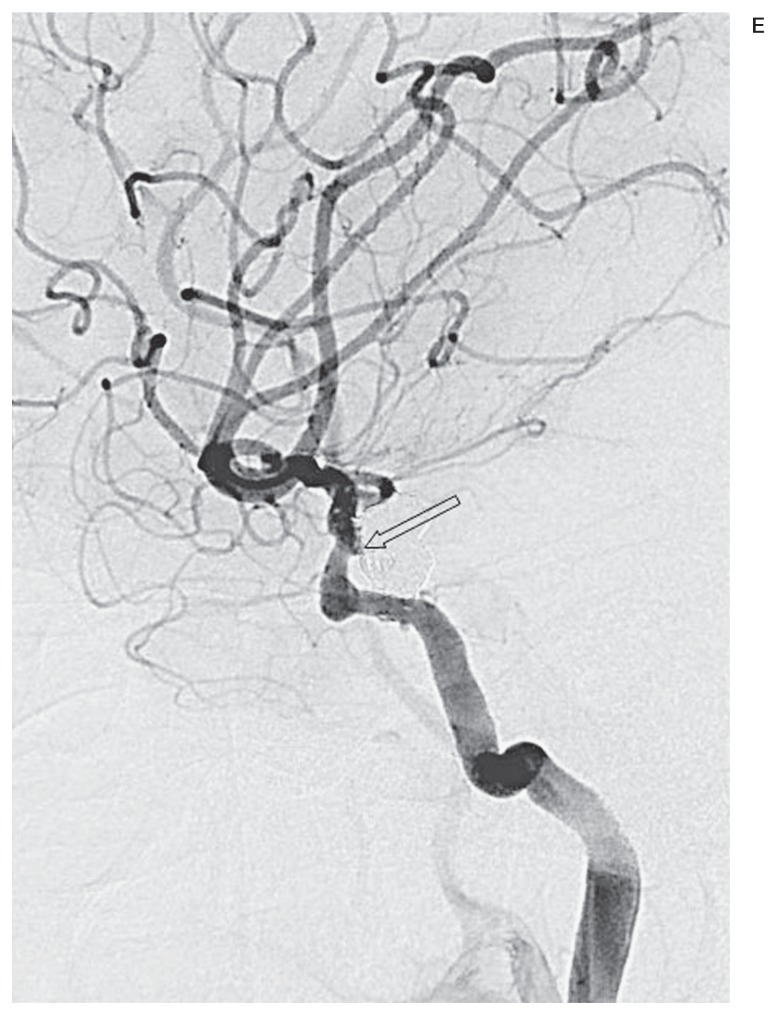

Figure 2.

A false negative case associated with minimal recanalization. Compared with a working-angle angiogram preembolization (A), the same view postembolization (B) clearly shows complete occlusion of the aneurysm. C) A mask image of working-angle completion DSA shows the coil mass and proximal and distal markers of a Neuroform stent (arrowheads). D) A corresponding FIC at 4 months demonstrates no finding of recanalization, but a working-angle angiogram (E) reveals minimal recanalization (open arrow) in no need for retreatment.

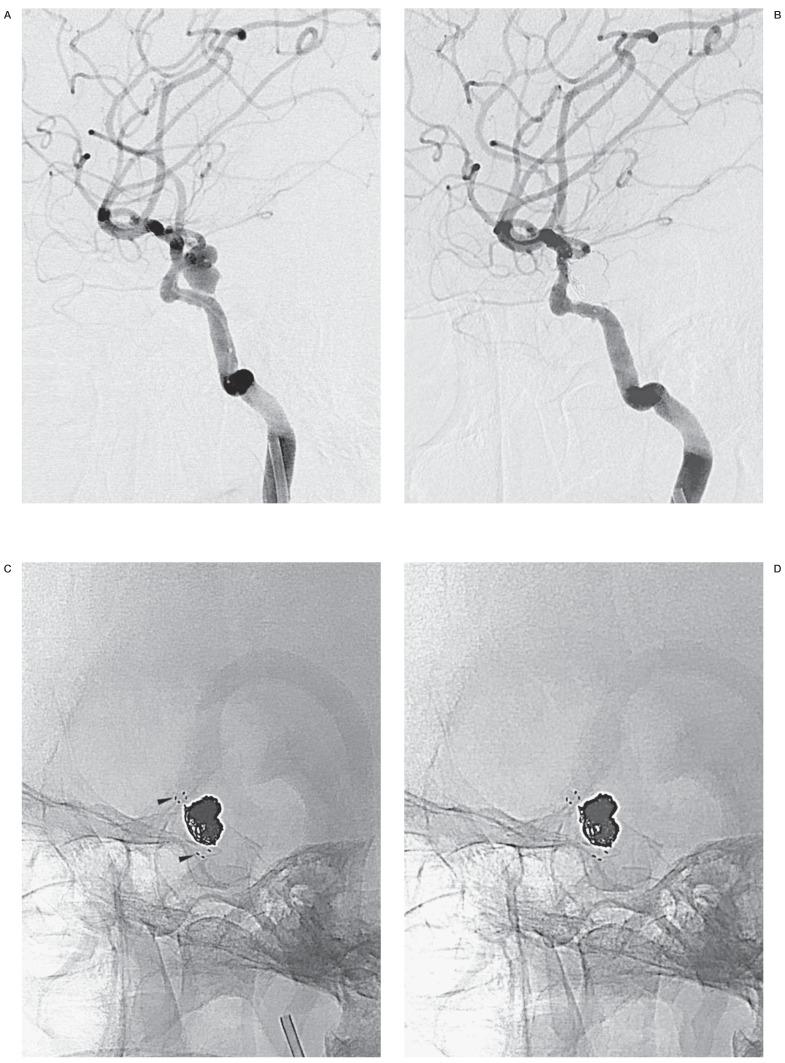

Figure 3.

A false positive case with protruded coils put back to the aneurysm orifice over time. Compared with a working-angle angiogram preembolization (A), the same view postembolization (B) demonstrates protruded coils (white arrow) towards the arterial lumen through or beneath stent struts. A stent-assisted coiled contralateral Pcom aneurysm is also shown (black arrow). A mask image of working-angle DSA on procedural completion (C) shows the coil mass (white arrow). The same view at 9 months (D) reveals coil loosening and compaction (arrowhead), but both readers made different decisions on recanalization. A working-angle angiogram at 9 months (E) shows complete occlusion of the aneurysm with the protruded coils put back to the aneurysm orifice (arrowhead).

Discussion

The evaluation of FICs for recanalization of stent-assisted coiled aneurysms yielded a high specificity of over 95% in this study. Respective sensitivities of 67% and 79% by two readers may not be the best performance for a screening tool but seven of all eight false negative cases did not need retreatment due to minimal recanalization or minimal contrast filling. As any occurrence or increase in intraaneurysmal contrast filling was considered recanalization, FICs seemed to be unable to find such minimal recanalization. When FICs were targeted to finding only significant recanalization in need of retreatment, they had a high sensitivity of over 94% leading to excellent diagnostic performance for recanalization. FICs even have substantial advantages over conventional angiography or TOF-MRA, including a very low cost, short acquisition time taking just a few minutes, negligible inconvenience to patients, and no risk of complications.

In this respect, we suggest that the first line follow-up tool for stent-assisted coiled aneurysms be FICs. In FIC-positive cases, the next step can be either contrast-enhanced MRA/TRICS MRA or conventional angiography depending on the degree of compaction or loosening of coil masses 15,16,19. TOF-MRA is not a possible option because of considerable in-stent signal loss, though its severity varies according to the type of stents 20. If the degree of compaction or loosening is low, contrast-used MRA sequences may be a possible option. However, obvious compaction or loosening leaving a sizable space in aneurysms would prompt conventional angiography. In the case of aneurysm compaction, there is reasonable doubt on the diagnostic performance of MRA sequences. Contrary to TOF-MRA that has high sensitivity and specificity for recanalization of unstented coiled aneurysms, there is still no scientific evidence that contrast-enhanced MRA or TRICS MRA has appropriate diagnostic performance for recanalization of stented coiled aneurysms, just suggesting feasibility 16 or better in-stent visualization of TRICS MRA over TOF-MRA 15. In our personal experience, contrast-enhanced MRA or TRICS MRA may be complementary to FICs in detecting recanalization of stented coiled aneurysms. However, it should be tested before clinical application.

Half of the false positive cases were associated with protruded intraluminal coils put in place over time, so careful comparison of working-angle angiograms before and after embolization is required to avoid misreading protruded coils that have returned to normal as coil compaction. If aneurysm perforation complicated the procedure, the final coil mass following coil placement in and out of the aneurysm would have a bizarre shape different from the aneurysm contour. The coil mass can then be easily deformed or loosened during follow-up regardless of recanalization. One of three false positive cases by both readers corresponded to this explanation.

There were several limitations to this study. The main limitation was the retrospective nature, which lacks the high scientific quality of well designed prospective studies. The second limitation was that only two institutions participated in this study. That might have caused biased results from a few hospitals, such as a propensity for overpacking or coil protrusion. In this study, half the false positive cases were misregarded as recanalization due to protruded coils put in place over time. Meanwhile, the follow-up DSAs were taken at the same view as the initial one but could have some differences in a small range of angles. However, the authors excluded inappropriate cases in views that could not be compared to minimize erroneous assessment. Lastly, FIC acquisition was not without radiation exposure. Although it was not measured during FIC acquisition, exposure was expected to be minimal as a set of FICs consisted of three or four views and each view only needed a few X-ray activations for angle correction for one or two seconds per activation. No need for prolonged X-ray activation was associated with the use of the fluoroscopic last image-hold function, a dose-saving function that exploits the benefits of image storage on a monitor.

Conclusions

After embolization of cerebral aneurysms, follow-up imaging studies are mandatory to disclose recanalization and avoid future bleeding. For stent-assisted coiled aneurysms, invasive cerebral angiography has been the choice of follow-up imaging modalities, because MRA does not provide adequate image quality for assessment unlike for unstented cases. However in this study, simple and safe FIC examinations were found to have a high diagnostic performance for significant recanalization, so that FICs may be suggested as a screening tool. The findings of this study should be tested in larger scale studies before being generalized.

References

- 1.Kwon BJ, Seo DH, Ha YS, et al. Endovascular treatment of wide-necked cerebral aneurysms with an acute angle branch incorporated into the sac: novel methods of branch access in 8 aneurysms. Neurointervention. 2012;7(2):93–101. doi: 10.5469/neuroint.2012.7.2.93. doi: 10.5469/neuroint.2012.7.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim BM, Park SI, Kim DJ, et al. Endovascular coil embolization of aneurysms with a branch incorporated into the sac. Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(1):145–151. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1785. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moret JC, Weill A. The "remodelling technique" in the treatment of wide neck intracranial aneurysms. angiographic results and clinical follow-up in 56 cases. Interv Neuroradiol. 1997;3(1):21–35. doi: 10.1177/159101999700300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierot L, Cognard C, Spelle L, et al. Safety and efficacy of balloon remodeling technique during endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms: critical review of the literature. Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33(1):12–15. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2403. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henkes H, Bose A, Felber S, et al. Endovascular coil occlusion of intracranial aneurysms assisted by a novel self-expandable nitinol microstent (neuroform) Interv Neuroradiol. 2002;8(2):107–119. doi: 10.1177/159101990200800202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiorella D, Albuquerque FC, Han P, et al. Preliminary experience using the Neuroform stent for the treatment of cerebral aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2004;54(1):6–16. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000097194.35781.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLaughlin N, McArthur DL, Martin NA. Use of stent-assisted coil embolization for the treatment of wide-necked aneurysms: A systematic review. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4:43. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.109810. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.109810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Yu LM, et al. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebleeding, subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet. 2005;366(9488):809–817. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67214-5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murayama Y, Nien YL, Duckwiler G, et al. Guglielmi detachable coil embolization of cerebral aneurysms: 11 years' experience. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(5):959–966. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.5.0959. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.5.0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwee TC, Kwee RM. MR angiography in the follow-up of intracranial aneurysms treated with Guglielmi detachable coils: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroradiology. 2007;49(9):703–713. doi: 10.1007/s00234-007-0266-5. doi: 10.1007/s00234-007-0266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anzalone N, Scomazzoni F, Cirillo M, et al. Follow-up of coiled cerebral aneurysms at 3T: comparison of 3D time-of-flight MR angiography and contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29(8):1530–1536. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1166. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willinsky RA, Taylor SM, TerBrugge K, et al. Neurologic complications of cerebral angiography: prospective analysis of 2,899 procedures and review of the literature. Radiology. 2003;227(2):522–528. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272012071. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272012071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waugh JR, Sacharias N. Arteriographic complications in the DSA era. Radiology. 1992;182(1):243–246. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.1.1727290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heiserman JE, Dean BL, Hodak JA, et al. Neurologic complications of cerebral angiography. Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15(8):1401–1407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi JW, Roh HG, Moon WJ, et al. Time-resolved 3D contrast-enhanced MRA on 3.T: a non-invasive follow-up technique after stent-assisted coil embolization of the intracranial aneurysm. Korean J Radiol. 2011;12(6):662–670. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2011.12.6.662. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2011.12.6.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agid R, Schaaf M, Farb R. CE-MRA for follow-up of aneurysms post stent-assisted coiling. Interv Neuroradiol. 2012;18(3):275–283. doi: 10.1177/159101991201800305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cottier JP, Bleuzen-Couthon A, Gallas S, et al. Follow-up of intracranial aneurysms treated with detachable coils: comparison of plain radiographs, 3D time-of-flight MRA and digital subtraction angiography. Neuroradiology. 2003;45(1):818–824. doi: 10.1007/s00234-003-1109-7. doi: : 10.1007/s00234-003-1109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy D, Milot G, Raymond J. Endovascular treatment of unruptured aneurysms. Stroke. 2001;32(9):1998–2004. doi: 10.1161/hs0901.095600. doi: 10.1161/hs0901.095600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seok JH, Choi HS, Jung SL, et al. Artificial luminal narrowing on contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiograms on an occasion of stent-assisted coiling of intracranial aneurysm: in vitro comparison using two different stents with variable imaging parameters. Korean J Radiol. 2012;13(5):550–556. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2012.13.5.550. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2012.13.5.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi JW, Roh HG, Moon WJ, et al. Optimization of MR Parameters of 3D TOF-MRA for Various Intracranial Stents at 3.T MRI. Neurointervention. 2011;6(2):71–77. doi: 10.5469/neuroint.2011.6.2.71. doi: 10.5469/neuroint.2011.6.2.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]