Summary

The advent of flow dynamics and the recent availability of perfusion analysis software have provided new diagnostic tools and management possibilities for cerebrovascular patients. To this end, we provide an example of the use of color-coded angiography and its application in a rare case of a patient with a pure middle cerebral artery (MCA) malformation.

A 42-year-old male chronic smoker was evaluated in the emergency room due to sudden onset of severe headache, nausea, vomiting and left-sided weakness. Head computed tomography revealed a right basal ganglia hemorrhage. Cerebral digital subtraction angiography (DSA) showed a right middle cerebral artery malformation consisting of convoluted and ectatic collateral vessels supplying the distal middle cerebral artery territory-M1 proximally occluded. An associated medial lenticulostriate artery aneurysm was found. Brain single-photon emission computed tomography with and without acetazolamide failed to show problems in vascular reserve that would indicate the need for flow augmentation.

Twelve months after discharge, the patient recovered from the left-sided weakness and did not present any similar events. A follow-up DSA and perfusion study using color-coded perfusion analysis showed perforator aneurysm resolution and adequate, albeit delayed perfusion in the involved vascular territory.

We propose a combined congenital and acquired mechanism involving M1 occlusion with secondary dysplastic changes in collateral supply to the distal MCA territory. Angiographic and cerebral perfusion work-up was used to exclude the need for flow augmentation. Nevertheless, the natural course of this lesion remains unclear and long-term follow-up is warranted.

Keywords: color-coded angiography, arterial malformation, intracerebral hemorrhage

Introduction

The advent of flow dynamics and the recent availability of perfusion analysis software have provided new diagnostic tools and management possibilities for cerebrovascular patients with conditions as diverse as cerebral ischemia, vascular malformations, tumors, and neurodegenerative disorders 1-4. Angiographic and perfusion techniques are able to provide blood flow information that may be important in lesion characterization and improved quality of management. Perfusion imaging techniques and analysis software are under continuous development and refinement. Faster, simpler and more accessible tools are necessary to guide therapy and improve outcomes at the procedure table, as in cases of acute stroke, arteriovenous malformations or fistulae 5,6.

To this end, we provide an example of the use of color-coded perfusion digital subtraction angiography (DSA) and its application in a rare case of a patient with a pure middle cerebral artery (MCA) malformation. To our knowledge, only two similar cases have been reported since the early 1900s 7,8. Through color-coded angiography, a single color-coded parametric perfusion image is calculated from a DSA sequence, resulting in improved visualization of perfusion. Time to peak (TTP) and peak opacification (POp) profiles enable the user with an improved perspective of the characteristics of vascular flow 9. This may become important after arteriovenous malformation (AVM) or fistula embolization procedures 5,6, flow-augmentation procedures 10 or when comparing vascular flow in different anatomical regions of the brain.

Case Report

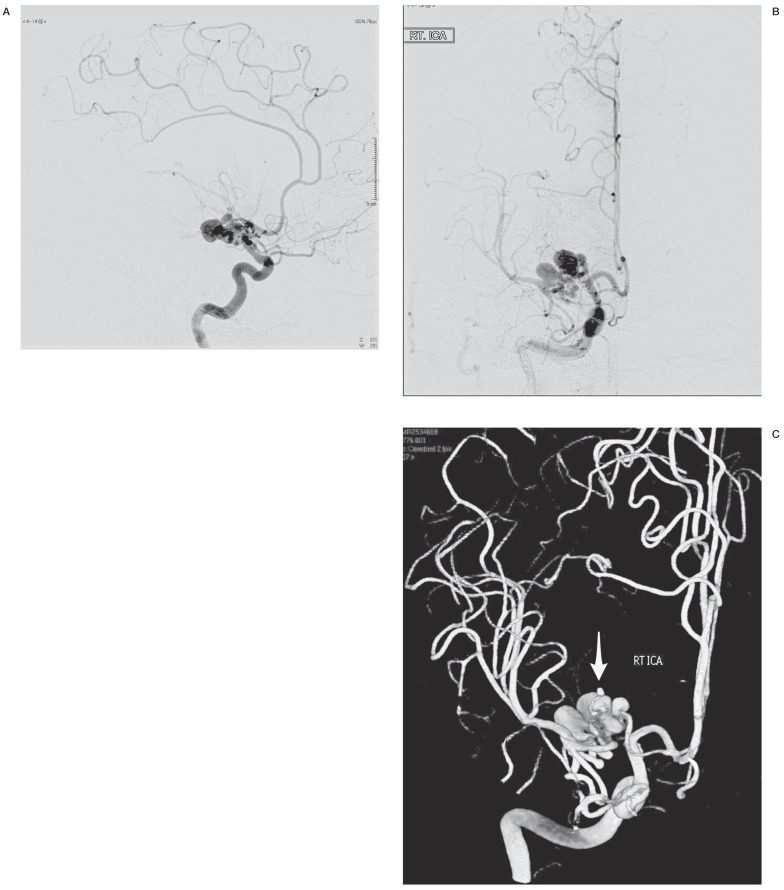

A 42-year-old man presented to the emergency room with a severe and sudden exacerbation of headache of ten days evolution. His medical history included chronic smoking, yet no other systemic or significant familial illnesses. He also referred sudden onset of left-sided weakness and intermittent nausea and vomiting that started the day of evaluation. Non-contrast head computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were consistent with an intracerebral right basal ganglia hemorrhage. Cerebral CT angiogram demonstrated a right MCA vascular lesion associated with the hematoma (Figure 1A,B). Subsequent DSA was performed (Figure 2A,B) showing a right MCA malformation consisting of convoluted and ectatic collateral vessels supplying the distal MCA territory-M1 proximally occluded. In addition, a small medial lenticulostriate artery aneurysm was found corresponding to the hematoma location (Figure 2C). The dysplastic collateral supply originated from the supraclinoid carotid and proximal right anterior cerebral artery circulation-A1, proximal A2, and Heubner artery (Figure 2). There was no noted collateral supply from the intracranial posterior circulation or the external carotid circulation. In addition, no early venous drainage was identified to suggest an arteriovenous malformation or fistula, and the remaining cerebral arterial anatomy was normal.

Figure 1.

A) Cerebral CT angiogram showing right middle cerebral artery malformation consisting of ectatic and aneurysmal arterial collaterals. B) Gadolinium-enhanced T1WI MRI showing an area of acute basal ganglia hemorrhage associated with the arterial malformation.

Figure 2.

A) Cerebral DSA of the right internal carotid, AP view, showing the MCA malformation consisting of convoluted ectatic and aneurysmal arterial collaterals coming from the ipsilateral supraclinoid carotid and anterior cerebral arteries. Note the associated occlusion of M1 segment of the MCA. B) DSA, lateral view. C) 3D reconstruction of the rotational angiographic views, demonstrating the spatial configuration of the arterial malformation. Note the small lenticulostriate artery aneurysm (arrow), likely associated with the basal ganglia hemorrhage.

Given these findings, a cerebral perfusion study was deemed necessary to evaluate for a possible chronic perfusion deficit in the involved territory. Brain single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) with and without acetazolamide was performed showing a fixed defect in the right basal ganglia corresponding to the hematoma location. Acetazolamide administration failed to show deficit in the distal MCA vascular reserve. After excluding the need for flow augmentation, and considering the significant risks aimed at obliterating the perforator aneurysm either surgically or by endovascular means, we decided upon conservative management on a statin-vessel wall stabilizing agent 11,12, blood pressure control, and lifestyle modifications-smoking cessation.

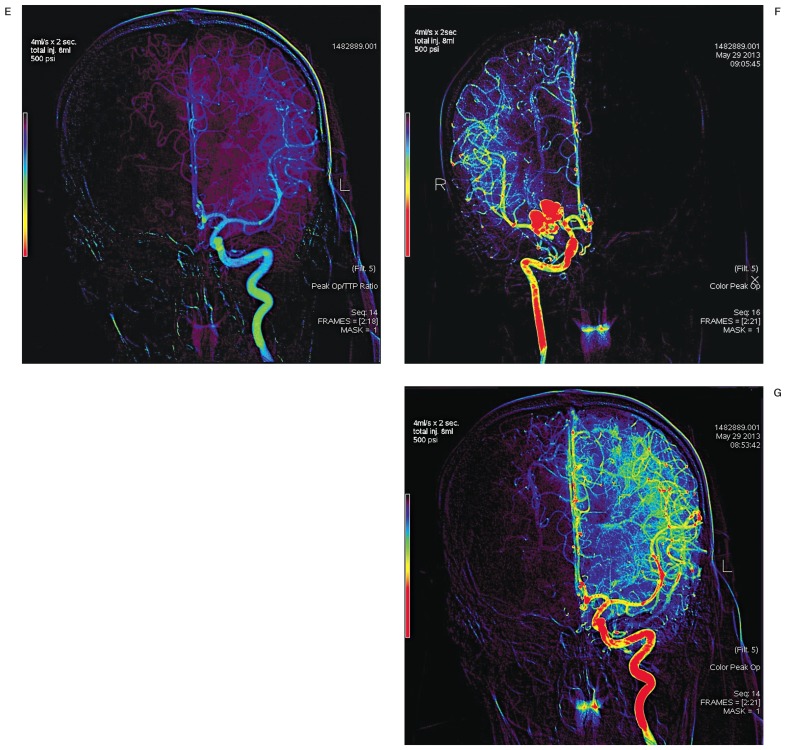

Twelve months after discharge, the patient had recovered from the left-sided weakness and did not present either re-bleeding or ischemic events. A follow-up angiogram and perfusion study using color-coded angiography and perfusion analysis showed perforator aneurysm resolution and preserved perfusion in the involved vascular territory (Figure 3A-G). Further close clinical follow-up as well as yearly evaluations with cerebral perfusion studies-SPECT and/or color-coded angiography are needed to determine if a flow augmentation procedure is warranted in the future.

Figure 3.

A,B) Color-coded perfusion images, AP view, of the right ICA, showing delayed perfusion (TTP) in the distal middle cerebral artery territory. C) DSA perfusion images, AP view, of the left ICA for comparison. Note increased TTP values at the mid-M2 segment in A, corresponding to the blue color range, 3.41s-4.27s. Note the difference in parametric color-coding upon increasing series range in B, yet with a similar TTP value range. D,E) Color-coded perfusion images, AP view, of the left and right ICA using the peak opacification: TTP ratio; and peak opacification (POp) (F,G). Note the similarity in perfusion profile color progression between left and right distal middle cerebral artery territories when evaluating POp.

Technique

DSA and color-coding perfusion analysis were done using a biplane angiography unit (Innova™ IGS 630, GE Medical Systems, France) equipped with an injector pump (ACIST Medical Systems Inc., MN, USA). AngioViz® perfusion software provided with the unit allowed for derivation of the color-coded images 9. A 5Fr diagnostic catheter (Terumo Medical Corporation, NJ, USA) was placed and maintained at the cervical internal carotid in all runs-C2 vertebral level. All perfusion assessment runs were performed using a constant volume of ionic contrast (8 mL), constant infusion rate (4 ml/s) and pressure (500 psi). Perfusion profiles using TTP, POp and the POp:TTP ratio were produced in the workstation after finalizing the procedure, reducing the need for further radiation time and contrast administration.

Discussion

Simmonds first described the concept of a pure cerebral arterial malformation in 1905. He reported the case of a 53-year-old man with a medium-sized pure arterial malformation. This diagnosis was made at autopsy 8. Morphologically, these malformations resemble embryonic vessels and the early anastomotic plexuses formed during the early stages of vascularization of the central nervous system 13.

Each cerebral vascular territory evolves and remains within a distinct and specific tissue compartment, continuously adapting to the growing structural and functional needs of each particular region of the developing brain. At this point, capillary angiogenesis and capillary reabsorption are active processes 8.

Proposed disease mechanism

Relatively few MCA variants have been described 14,15, of which the accessory MCA is the most significant 15. The nomenclature system used by Manelfe describes three types of accessory MCA variants depending on their origin, whether internal carotid artery (ICA), proximal or distal anterior cerebral artery (ACA) 16. Figure 2C shows a collection of enlarged collaterals coming from the ipsilateral ICA and ACA, suggesting that this pure arterial malformation has an embryological substrate. In addition, the presence of multiple aneurysmal ectasias is a characteristic to which an accessory MCA variant has been highly associated 14,17, in addition to collateral supply dysplastic changes in the setting of MCA occlusion 18.

Secondary vascular dysplasia and dolichoectatic changes may have developed in a way similar to that of moyamoya syndrome 7. The vascular network in patients with this disease is considered to represent collateral channels formed as a result of progressive ischemic changes occurring in the brain tissue 19. In our patient, collaterals from the ICA and ACA, including the artery of Heubner, supplied the distal and proximal MCA circulation (Figure 2A-C). The recurrent artery of Heubner, also known as the medial distal striate artery, arises most commonly from the proximal A2. As this artery supplies the head of the caudate, septal nucleus, globus pallidus and putamen, the patient maintained an adequate deep basal ganglia collateral supply 20.

In 1986, Hanakita et al. 7 described the case of a 43-year-old woman with multiple cerebral arterial ectasias associated with MCA stenosis and moyamoya syndrome. In this case, the notion of chronic ischemia as the causative factor of arterial changes was strengthened by the fact that the patient improved after external carotid-internal carotid bypass.

Other reports have pointed to a relationship between MCA stenosis and a post-stenotic dilatation pattern 21, moyamoya with its attendant changes in the anterior choroidal and posterior communicating arteries and the risk of hemorrhage 22, as well as the presence of arterial ectasias and aneurysms 23, suggesting a flow-related or shear stress-related pathophysiologic mechanism. In our case, the need for flow augmentation was excluded (though not discarded in the future) after evaluation of perfusion studies. In addition, considering the risks aimed at obliterating the perforator aneurysm either surgically or by endovascular means, we decided upon conservative management with a statin-vessel wall stabilizing agent 11,12, blood pressure control, and lifestyle modifications-smoking cessation.

Color-coded angiography

There are several imaging techniques available to assess cerebral perfusion. These provide similar information on cerebral hemodynamics in the form of parameters such as cerebral blood flow (CBF), cerebral blood volume (CBV), TTP flow, and mean transit time (MTT) 24. Perfusion imaging may be able to distinguish infarcted from salvageable ischemic tissue as a guide to treatment. Color-coding DSA gives the opportunity to evaluate perfusion in the same procedure while performing controlled angiographic injections in the vascular territory of interest, avoiding the need for further radiation and contrast exposure. Parameters like TTP and POp provide qualitative or semi-quantitative perfusion information. The one-year follow-up study in our patient using color-coded DSA showed relatively prolonged TTP values in the right MCA area. Figure 3A shows the increased TTP values at the mid-M2 segment, corresponding to the blue color range, 3.41 s-4.27 s. A TTP value of more than six seconds has been estimated as the threshold for clinically significant hypoperfusion 25 though there is a tendency to overestimate tissue at risk. Subsequent evaluation of POp:TTP and POp profiles, related to CBF and CBV respectively, showed there was qualitative perfusion similarity (color profiles and progression) between both hemispheres (Figure 3F,G), albeit delayed. These findings are subject to inter-observer variability. The perception of color profiles and progression without quantification is a significant limitation of the AngioViz® perfusion software that deserves improvement.

Limitations

As with any new technique or post-processing analysis software, clinical and statistical validation is needed. Currently there are only few cases in the literature for validation. It remains as a qualitative or semi-quantitative assessment tool until available mathematical algorithms that correct for hemodynamic factors, like proximal stenosis, pump issues or contrast dispersion, are included.

Conclusion

We describe a rare case of a patient with a pure cerebral arterial malformation associated with MCA occlusion. Available literature suggests that if vascular physiologic studies are adequate, conservative management may be feasible. The use of perfusion studies - brain SPECT and more recently, DSA with color-coded perfusion assay - was determinant upon choosing therapy. Nevertheless, the treatment of these lesions remains unclear. We advocate treating these and similar vascular anomalies on a case-by-case basis, and after a careful assessment of the risks and benefits of available alternatives.

References

- 1.Borghammer P. Perfusion and metabolism imaging studies in Parkinson's disease. Dan Med J. 2012;59:B4466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochberg AR, Young GS. Cerebral perfusion imaging. Semin Neurol. 2012;32:454–465. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1331815. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1331815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim DJ, Krings T. Whole-brain perfusion CT patterns of brain arteriovenous malformations: a pilot study in 18 patients. Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:2061–2066. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2659. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peet AC, Arvanitis TN, Leach MO, et al. Functional imaging in adult and paediatric brain tumours. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.187. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golitz P, Struffert T, Lucking H, et al. Parametric color coding of digital subtraction angiography in the evaluation of carotid cavernous fistulas. Clin Neuroradiol. 2013;23:113–120. doi: 10.1007/s00062-012-0184-8. doi: 10.1007/s00062-012-0184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin CJ, Luo CB, Hung SC, et al. Application of color-coded digital subtraction angiography in treatment of indirect carotid-cavernous fistulas: initial experience. J Chin Med Assoc. 2013;76:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2012.12.009. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanakita J, Miyake H, Nagayasu S, et al. Surgically treated cerebral arterial ectasia with so-called moyamoya vessels. Neurosurgery. 1986;19:271–273. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198608000-00017. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198608000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasargil MG, editor. AVM of the brain, history, embryology, pathological considerations, hemodynamics, diagnostic studies, microsurgical anatomy. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 9.2013 http://www3.gehealthcare.com.sg/~/media/Downloads/us/Product/Product-Categories/Advanced-Visualization/AngioViz/GEHC-Datasheet_AW-AngioViz.pdf?Parent=%7B55184DBF-95FD-4C8B-9473-43963E062DF4%7D". Accessed August 1, 2013/2013.

- 10.Lin CJ, Hung SC, Guo WY, et al. Monitoring peri-therapeutic cerebral circulation time: a feasibility study using color-coded quantitative DSA in patients with steno-occlusive arterial disease. Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33:1685–1690. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3049. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valenca MM. "Sit back, observe, and wait. Or is there a pharmacologic preventive treatment for cerebral aneurysms? Neurosurg Rev. 2013;36:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10143-012-0429-7. discussion 9-10. doi: 10.1007/s10143-012-0429-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshimura Y, Murakami Y, Saitoh M, et al. Statin Use and Risk of Cerebral Aneurysm Rupture: A Hospital-Based Case-Control Study in Japan. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23(2):343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.04.022. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bautch VL, James JM. Neurovascular development: The beginning of a beautiful friendship. Cell Adh Migr. 2009;3:199–204. doi: 10.4161/cam.3.2.8397. doi: 10.4161/cam.3.2.8397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harnsberger HR OA, MacDonald A, Ross J, et al. Diagnostic and surgical imaging anatomy: Brain, Head and Neck, Spine. Salt Lake City: Amirsys; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komiyama M, Nakajima H, Nishikawa M, et al. Middle cerebral artery variations: duplicated and accessory arteries. Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:45–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abanou A, Lasjaunias P, Manelfe C, et al. The accessory middle cerebral artery (AMCA). Diagnostic and therapeutic consequences. Anat Clin. 1984;6:305–309. doi: 10.1007/BF01654463. doi: 10.1007/BF01654463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koulouris S, Rizzoli HV. Coexisting intracranial aneurysm and arteriovenous malformation: case report. Neurosurgery. 1981;8:219–222. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198102000-00012. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198102000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komiyama M, Nishikawa M, Yasui T. The accessory middle cerebral artery as a collateral blood supply. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:587–590. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takagi Y, Kikuta K, Sadamasa N, et al. Caspase-3-dependent apoptosis in middle cerebral arteries in patients with moyamoya disease. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:894–900. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000232771.80339.15. discussion 900-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomes F, Dujovny M, Umansky F, et al. Microsurgical anatomy of the recurrent artery of Heubner. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:130–139. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.1.0130. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.1.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi JW, Kim JK, Choi BS, et al. Angiographic pattern of symptomatic severe M1 stenosis: comparison with presenting symptoms, infarct patterns, perfusion status, and outcome after recanalization. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;29:297–303. doi: 10.1159/000275508. doi: 10.1159/000275508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morioka M, Hamada J, Kawano T, et al. Angiographic dilatation and branch extension of the anterior choroidal and posterior communicating arteries are predictors of hemorrhage in adult moyamoya patients. Stroke. 2003;34:90–95. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000047120.67507.0d. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000047120.67507.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voros E, Kiss M, Hanko J, et al. Moyamoya with arterial anomalies: relevance to pathogenesis. Neuroradiology. 1997;39:852–856. doi: 10.1007/s002340050519. doi: 10.1007/s002340050519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wintermark M, Sesay M, Barbier E, et al. Comparative overview of brain perfusion imaging techniques. J Neuroradiol. 2005;32:294–314. doi: 10.1016/s0150-9861(05)83159-1. doi: 10.1016/S0150-9861(05)83159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell BC, Christensen S, Levi CR, et al. Comparison of computed tomography perfusion and magnetic resonance imaging perfusion-diffusion mismatch in ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:2648–2653. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.660548. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.660548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]