Abstract

Background

The Mental Health–Clergy Partnership Program established partnerships between institutional (Department of Veterans’ Affairs [VA] chaplains, mental health providers) and community (local clergy, parishioners) groups to develop programs to assist rural veterans with mental health needs.

Objectives

Describe the development, challenges, and lessons learned from the Mental Health–Clergy Partnership Program in three Arkansas towns between 2009 and 2012.

Methods

Researchers identified three rural Arkansas sites, established local advisory boards, and obtained quantitative ratings of the extent to which partnerships were participatory.

Results

Partnerships seemed to become more participatory over time. Each site developed distinctive programs with variation in fidelity to original program goals. Challenges included developing trust and maintaining racial diversity in local program leadership.

Conclusions

Academics can partner with local faith communities to create unique programs that benefit the mental health of returning veterans. Research is needed to determine the effectiveness of community based programs, especially relative to typical “top-down” outreach approaches.

Keywords: Community partnerships, rural veterans, clergy, faith communities, South

An estimated 40% of the one in five recent U.S. military veterans who return home with a mental health problem return home to rural areas.1,2 Although a greater percentage of recently returning veterans are using the VA and other sources of care than in previous years,3 and multiple programs exist to support veterans and their families,4 many veterans seem reluctant to seek mental health care, even when need is high.1,5 The recent apparent rise in suicides among veterans,6,7 especially in rural areas,8 dramatically illustrates the gap between need and treatment engagement.

Because mental health problems in rural communities are often considered domains for family and church,9 clergy often serve as informal mental health providers.10–12 Rural residents may prefer clergy because they are more familiar with clergy, clergy do not charge for their services, and there is less stigma involved with visiting a member of the clergy.13,14 However, clergy often state that they feel inadequately prepared to identify and address mental disorders and some are not well-versed in how and where to refer their parishioners should they need formal mental health treatment.15–19

The goal of the Mental Health–Clergy Partnership Program was to develop partnerships between VA mental health researchers and VA chaplains (“institutional partner”) and local clergy and faith communities (“community partner”) to develop local programs to promote mental health treatment of veterans in need. Community-based programs have not been used extensively by the VA. VA-sponsored outreach efforts have typically involved development of a standard training program followed by delivery of the same program in one or more sites in a “top-down” manner. Rarely, if ever, have community members partnered to design or develop local programs that would be appropriate for a specific community. This VA-sponsored, community-based program, although not a true community-based participatory research (CBPR) partnership, relied on some principles of CBPR, including building on community strengths and resources and promoting collaborative planning and partnerships. This paper describes this experience from the point of view of the institutional partners.

Although the partnerships at each site developed distinctive programs, we (the institutional partners) initially asked community partners to concentrate on improving the community’s knowledge about mental illness and promoting access or linkage to mental health resources. We expected the programs formed in this way would be unique to each particular site, and would have a better chance to be sustained over time than more typical “top-down” trainings. What was common across all sites was the partnership building approach. In this paper, we present our approach to partnership building, describe the programs that emerged, and discuss challenges and lessons learned.

METHODS

Setting

The Mental Health–Clergy Partnership Program is a project within the Department of Veterans Affairs’ South Central Veterans Integrated Service Network 16 and is managed by the South Central Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center, a network-wide center focusing on improving mental health care for veterans residing in rural areas in all or part of eight states from the panhandle of Oklahoma to the panhandle of Florida. Veterans in this network score among the lowest in the country on measures of perceived health status.20

Institutional Leadership

The program was initiated with a small grant to support the two leaders of the project—a VA chaplain and a psychiatrist/researcher with the South Central Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center—to develop partnerships at one site. Subsequent funding allowed us to add two additional sites and to involve more institutional participants. The project hinges on chaplain involvement, because in many ways the VA chaplain bridges the cultural divide between the VA researchers and local clergy. In addition to their chaplain credentials, the VA chaplains involved in this program have had additional training or experience in psychology or mental health. Tensions across the religious and mental health communities often exist21,22 and a cornerstone of this project has been the unusually positive relationship between the chaplains and the mental health professionals who form the institutional partnership.

Site Selection

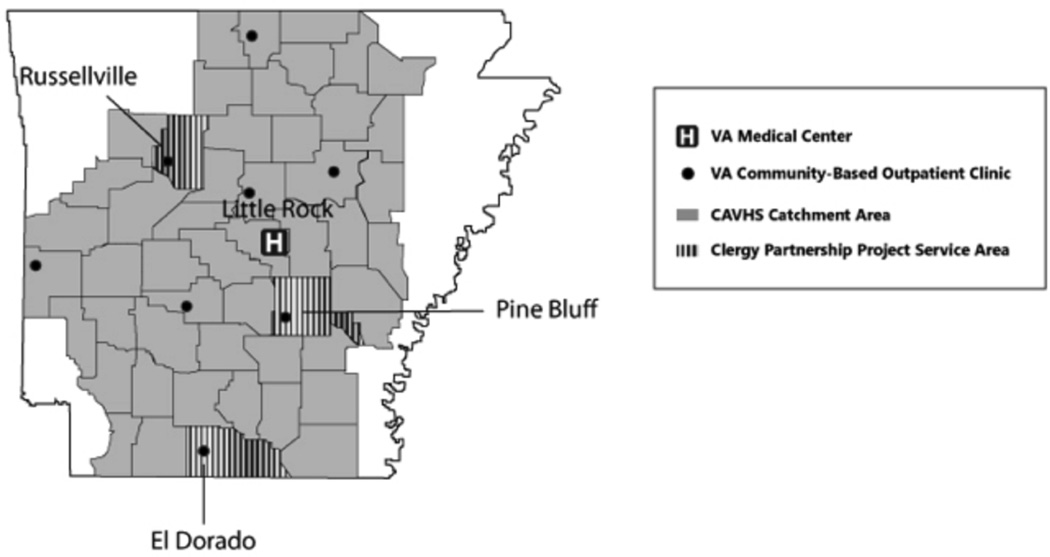

The institutional leaders identified three Arkansas partnership sites according to these criteria: Rural towns (populations less than 50,000) with a high concentration of veterans and a VA, community-based outpatient clinic employing an interested mental health provider; and a set of sites that varied in terms of race. We chose El Dorado, Russellville, and Pine Bluff (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Site Locations for Clergy Partnership Project.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Local Partnership Projects

| El Dorado (Union County) |

Russellville (Pope County) |

Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Town | |||

| Population | 18,884 (decreasing) | 27,920 (growing) | 49,082 (decreasing) |

| Below Poverty Line (%) | 25 | 18 | 41 |

| Racial Makeup | |||

| White | 54 | 83 | 22 |

| African American | 44 | 6 | 76 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 11 | 1 |

| Major Employers | Oil and gas industry | Arkansas Tech University Nuclear One (Arkansas’ only power plant) | University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff Arkansas Department of Corrections |

| Community Advisory Board | |||

| Partnership Began | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

| Local Leader | Clergy member with a master’s degree in Psychology | Local mental health advocate | Clergy member |

| Board Membership | |||

| Clergy | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Veteran | 1 | — | 3 |

| Parent of a Veteran | 1 | — | |

| VA Mental Health Clinician | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| National Guard Family Assistance Employee | 1 | 1 | — |

| Ministerial Candidate | — | 1 | — |

| Local Government Official Who Is Also a Veteran | — | 1 | — |

| National Guard Family Assistance Employee | — | — | — |

| Church Member | — | — | 1 |

| Community Health Outreach Worker | — | — | 1 |

Targeting Rural Clergy

The Mental Health–Clergy Partnership Program aimed to create partnerships with local clergy and community members. Most Arkansans (>97%) identify as Christian, with more than half (53%) identifying as Evangelical Protestant, including Southern Baptist (by far the largest). Ten percent of Arkansans affiliate with Historically Black religious denominations such as African Methodist Episcopal. Only 16% of Arkansas residents identify with a mainline Protestant denomination (i.e., United Methodist Church), which are thought to be more theologically and socially liberal relative to evangelicals.23 Many of the mainline religious organizations have embraced addressing mental health needs as part of their mission. However, more conservative Christian denominations sometimes view mental health problems as originating from a lack of religious faith, or even from demonic possession, rather than from medical or psychological etiologies.24,25 For this reason, we attempted to engage clergy and congregations who were open to a more medically oriented model of mental health rather than those who would likely find a medical model unacceptable.

Program Structure

After initiating the program at the first site (El Dorado) in 2009, we expanded to two additional sites, Russellville in 2010 and Pine Bluff in 2011. We structured the program such that each site would work with a specific chaplain over time; the chaplain could draw from a pool of institutional team members who could assist at each site as needed. All of the VA chaplains who participated in the program were White, because we could identify no African-American VA chaplains with time available to participate; there were no Hispanic chaplains on staff. The chaplain for each site has 25% of his time supported by the project. A fourth chaplain, the program resource manager, is responsible for becoming familiar with VA and community veterans’ resources at each site and serving as resource consultant for each site. Other team members include three psychiatrists, one psychologist, one doctoral-level nurse, one academic anthropologist, a project manager, three veterans who have recently served in the Middle East and who are currently working as research assistants, and one part-time administrative assistant. Of the nine members of the institutional project team, four are African American and the rest are White. We actively sought to assemble a racially diverse team. The African Americans are a doctoral-level psychologist, a doctoral-level nurse, the project manager, and a research assistant.

At all three sites, the local advisory boards began their programs by requesting more information about veterans, spirituality, and mental health. Mental health professionals on the team developed presentations and educational materials about mental illness tailored to the local needs, especially posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, traumatic brain injury, and suicide. Chaplains made presentations about active listening, moral and religious issues related to war, and military families. Team members who are veterans delivered presentations about military culture and described their own experiences in combat and reintegration to civilian life. To date, 25 programs have been attended by approximately 960 local community members. The institutional partner project team meets weekly to discuss progress and plan for upcoming programs at each site. We view our activities primarily as building a foundation for future research. We are not collecting outcome data, but are collecting data about how many people attend each of the programs offered at individual sites.

Creating and Working With Local Advisory Boards

The initial challenge was how to form partnerships in rural locations where the VA leaders had few existing relationships and where there were relatively few community organizations. First, we attempted to identify and understand the local community resources related to health and mental health, the military, safety net social services, and education. At each site, we visited local VA community-based clinics, community mental health clinics, and free or low-cost health clinics. We met with personnel at local National Guard armories or military installations and with those heading safety net programs such as the Salvation Army and local veterans’ service organizations. Second, as we were becoming familiar with local communities, we attempted to identify at least one clergy member who was interested in being involved in, and potentially leading, a program related to mental health of military veterans. And third, with the help of this clergy member, we constituted a local advisory board consisting of members of the clergy, veterans, and local service providers, including the mental health provider at the local VA community-based outpatient clinic. We considered these local advisory boards, created through this process, to be our key community partner at each site. We met with each advisory board at least once a month and together decided on a series of local activities. Our initial budget did not include payments for local advisory board members’ time, although we were able to provide a one-time, $1,000 honorarium for the leaders of the local boards. Although we did not create formal memoranda of understanding for local advisory board members, discussion occurred at each site about the advisory board’s role.

Evaluation of Partnerships

Because a central goal of this effort was to build local partnerships, we aimed to understand the nature of the partnerships by using an assessment tool developed by Naylor an colleagues.26 We chose this tool because we were especially interested in ensuring that our partnerships were participatory in nature rather than being dominated by the institutional partner; the Naylor tool is intended to assess the extent to which partnerships are participatory along six dimensions (Table 2). Three local advisory board members and three institutional partners at each site rated each of the six Naylor criteria on a scale from 1 to 4, with 1 being the greatest degree of control by the institutional partners and 4 being the greatest control by community members (Table 3). The scales were administered by an institutional team member face to face or by phone to ensure that the community respondents understood the criteria and scales and could ask questions. No identifying data were collected. The VA Institutional Review Board approved this project.

Table 2.

Rating Scale for Participatory Research Elements

| Quantitative Assessment Rating Scale | Consultation 1 |

Cooperation 2 |

Participation 3 |

Full Control 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert-Driven Research | Participatory Research | |||

| Identification of Need | Experts present predetermined issues, community input sought only once to “sell program” | Community offers advice and ongoing advisory input, but decision making rests with experts | Equal decision making by experts and community | Community controls decision making, experts advise |

| Definition of Research Goals and Activities | Experts present predetermined issues, community input sought only once to “sell” program | Community offers advice and ongoing advisory input, but decision making rests with experts | Equal decision making by experts and community | Community controls decision making, experts advise |

| Mobilization of Resources | Heavy influx of outside resources, local resources | Outside funding with use of local experts and community | Balanced funding and/or provision of in-kind | Seed money stimulates |

| Methodology of the Evaluation | Tests, surveys, interviews designed by researchers and conducted using hypothesis testing and significance of results statistically determined | Test, surveys, interviews designed by researchers, conducted by community, using hypothesis and significance of results statistically determined | Partnership in design and conduct using multiple methods of data collection in natural context | Advice from experts sought on design, 100% conducted by community using multiple methods in natural context |

| Indicators Used to Determine Success | Behavior changes, decrease in morbidity/mortality, risk factors, increase in knowledge and participation in programs | Behavior changes, decrease in morbidity/mortality, risk factors, increase in knowledge and participation in programs plus skill development in planning is facilitated | Findings used in ongoing planning, increase in knowledge of research, high participation in evaluation | Enhanced capabilities, skills, participation so that other issues are tackled with PR design |

| Sustainability of Programs | Program dies at completion of research | Few residual spinoffs from research programs | Programs continue when funding ceases | Initiation of new programs, citizens apply for further research funding |

Adapted from Naylor et al.26

Table 3.

Participants’ Evaluation of the Level of Collaboration (Mean Values)

| Participant | El Dorado | Russellville | Pine Bluff | Pooled Results Across All Sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Partners | 3.39 | 2.72 | 2.61 | 2.91 |

| Institutional Partners | 2.33 | 1.92 | 1.86 | 1.99 |

| Both Community and Institutional Partners | 2.86 | 2.26 | 2.07 | 2.35 |

Scale: 1 (full control by institutional partners), 2 (cooperation), 3 (participation), 4 (full control by community partners).

LOCAL PROGRAMS

El Dorado, Arkansas (population 18,884), is located in Union County in south central Arkansas, not far from the Louisiana border. As shown in Table 1, the town’s population is almost equally distributed among Whites and African Americans. El Dorado is the smallest of the three towns in the program. We began partnership building in El Dorado in 2009. Almost 12 months after we first began building relationships in El Dorado and holding regular meetings with a local advisory board, a new Southern Baptist clergy member joined the group, took charge, and energized the program. This leader, who also has a master’s degree in psychology and teaches at the local community college, began to engage more individuals and churches and adopted the name “Project SOUTH” (Serving Our Troops at Home). Project SOUTH has provided multiple training sessions for local clergy, served breakfast to troops leaving for predeployment training, hosted a 9/11 banquet, and created a program where volunteers from faith communities are linked to veterans and family members who need help with a variety of issues, such as money management, home maintenance, or help paying utility bills. Each week, the local leader of Project SOUTH sends an email to area churches requesting prayers for veterans and their families and soliciting donations for Project SOUTH activities; information has been provided to local congregations about how to incorporate veterans and veterans’ issues into church services. In 2011, the institutional partners assisted Project SOUTH to successfully apply for local funds to support a project administrator. Table 1 provides further information about the composition of the El Dorado advisory board.

Russellville, Arkansas (population 27,920) is the Pope county seat and relatively economically stable because it is home to Arkansas Tech University and Nuclear One, Arkansas’ only nuclear power plant. The town is 83% White and includes a relatively large Hispanic or Latino population, most of whom are immigrants (Table 2). About one in five live below the poverty level. We started to build the Mental Health–Clergy Partnership in Russellville in 2010 after we were contacted by a local advocate who was concerned about the suicide of a young veteran of the Iraq war who had graduated from high school in Russellville. This advocate assisted us in identifying community members for the local advisory board and linked us with the local ministerial alliance. Although the institutional partners, at the invitation of the community advisory board, have provided numerous educational programs in Russellville over time, the mainstay of the local program is quarterly meetings between local mental health providers and interested members of the faith community. These meetings have led directly to cross-referrals of veterans in need of either mental health or spiritual counseling. Table 1 provides more information about the makeup of the Russellville Advisory Board.

Pine Bluff, Arkansas (population 49,082; Jefferson County), is predominantly African American and is often seen as the gateway to Arkansas’ Mississippi River Delta region. Pine Bluff is the largest of the three towns in this project. Once a very prosperous town with an agricultural economic base, more than 40% of Pine Bluff’s population now lives below the poverty level. Pine Bluff is home to a large, historically black college, the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. Our Pine Bluff Partnership was initiated in 2011. In contrast with our other sites, we assigned two individuals to represent the institutional partner, a VA chaplain and VA psychologist who is African American. To date, the local advisory board has requested several education and discussion activities to learn more about military culture, mental health issues, reintegration problems common among Operation Enduring Freedom/ Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans, and practical ways the faith community can organize to address these problems. The program has adopted the name Very Important Project for Veterans (VIPVets) and conducted a public forum on veteran issues. With additional resources and at the suggestion of the local advisory board, the institutional partners are piloting a “veteran navigator” program in which a veteran peer (who is also a pastor of a local African-American church and has been treated for posttraumatic stress disorder) assists local veterans to connect with a range of VA services, including mental health services. Table 1 provides more information about the composition of the Pine Bluff advisory board.

EVALUATION OF PARTNERSHIPS

Because of the small sample size, we present herein only the overall scores at each site as rated by the community members and the institutional partners. Results are descriptive; no statistical analyses were conducted. Community members generally viewed the partnerships as involving more equal participation across the community and institutional partners than the institutional partners did (Table 3). Institutional partners saw themselves as being more powerful and thought that the community partners should take more ownership. This pattern appeared in all three sites. In addition, the scores seem to indicate that the longer the partnership had been in place, the greater the extent to which community members were perceived by both institutional and community partners as being in control of the program.

CHALLENGES AND LESSONS LEARNED

A number of challenges presented themselves in this program. First, there was the tension between “outsiders” and local residents. Outsiders may have some notion of the local history, but they are ignorant of the complex relationships that have been shaping these small communities over many years.27,28 Many community-based programs are initiated by forming a partnership with a specific community-based organization. In this case, we first chose the site (town) rather than the community partner. Coming in as an outsider to find appropriate community partners in an unknown town is a challenge; we found that we typically had to prove ourselves over many months before we could establish relationships. Within our own institutional group, we aimed to model positive relationships between mental health professionals and faith leaders. Regarding race, wherever possible we matched the races of the institutional site leadership with the local leadership; and we included veterans themselves in planning and programs.

Although a great deal of change has occurred in the South since the Civil Rights movement, many towns are still socially divided along racial lines. This became especially apparent to us in the challenges we faced in forming programs that functioned across faith communities of differing races. In each site, we invited persons with a range of racial or ethnic backgrounds to early community meetings and advisory boards, but fairly quickly each board came to consist of members of one race only. Because we did not initiate this program with funding to pay community partners, we had less control over who volunteered to serve on local advisory boards than we might have had if we had paid advisory board members from the outset. Even when we later were able to pay Pine Bluff advisory board members, that advisory board made the decision to focus exclusively on African Americans. This experience illustrated to us that the high value that we as the institutional partners placed on racial diversity was not necessarily shared by local community members. Although we are working to better understand how the situation might be altered, at the same time we appreciate that we are not in a position to heal years of mistrust.

As noted, we initiated this program without funds to pay local advisory board members, although we were able to pay local advisory board leaders a modest honorarium. We assisted the El Dorado advisory board to obtain their own funds. By 2011, we had obtained funds to pay local advisory board members in Pine Bluff. Because there is a great deal of concern for and support of military veterans in this area of the country, finding volunteers was not especially challenging. Paying board members in our first two sites might have resulted in less turnover in advisory board membership and more rapid progress. Even though advisory board members were not paid, they still perceived, to a greater extent than institutional partners, that there was equal participation and power sharing.

Another issue was what the institutional partners perceived as “mission drift,” especially in El Dorado. We initially defined assistance with mental health problems narrowly, hoping that programs would be developed to link veterans with mental health problems to appropriate resources. However, the El Dorado advisory board saw the mission more broadly. They viewed providing support to families and other community activities as preventing the development of mental health problems and promoting positive mental health. So as to not dampen local enthusiasm and energy, we made a strategic decision to support that broader mission and to later revisit this issue and attempt to create more effective linkage activities, which we have now begun in El Dorado. Likewise, in Pine Bluff we also noted that our navigator received requests to assist with a range of needs related to the VA, not only mental health. Again, we decided to support the navigator’s addressing the broader range of needs rather than focusing on mental health only. In contrast with the other two sites, the Russellville program began immediately to address linkage issues and experienced little drift from our original mission. In retrospect, we believe that spending more time initially defining and agreeing on a mission could have been helpful.

DISCUSSION

The Mental Health–Clergy Partnership Program adopted an approach that is novel in the VA; that is, we involved community members in planning interventions and tailoring them to local communities. Although not purely CBPR, our approach utilizes some principals of CBPR and represents an important step in that direction. Partnership development progressed at a different pace in each site, yet our evaluation suggests that at each site significant partnerships were formed. We were able to launch programs intended to benefit veterans and families that were unique to each site. Intrinsic differences across sites and a range of issues and tensions likely contributed to the programmatic variation. Paying local advisory board members for their time may have made the process more equitable and more efficient, and may have allowed us to maintain racial diversity on advisory boards. Had we not been promoting a compelling cause—assisting returning veterans—the partnerships may have been more challenging to form.

Those attempting a community partnership approach need to appreciate the amount of effort and resources needed over time to develop a foundation of trusting relationships. Much less effort is required to deliver educational programs to multiple sites in the traditional, top-down manner. For this reason especially, additional research is needed to determine whether these locally designed programs achieve desired outcomes and whether they offer benefits over more traditional, top-down approaches. Our impression is that several of these local programs have the potential to be sustained over time, which could be one benefit of this partnership approach.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Carrie Edlund for support in editing and preparation of the manuscript. This project was supported by the VA Office of Rural Health, the South Central VA Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tanielian T, Jaycox L, editors. Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Santa Monica (CA): RAND; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Office of Rural Health. [updated 2012; cited 2012 Jul 10]; Available from: http://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/

- 3.Seal KH, Metzler TJ, Gima KS, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, Marmar CR. Trends and risk factors for mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using Department of Veterans Affairs health care, 2002–2008. Am J Public Health. 2009 Sep;99(9):1651–1658. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.150284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Make the connection: Shared experiences and support for Veterans. [updated 2012; cited 2012 Jul 10]; Available from: http://maketheconnection.net. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems and barriers to care. US Army Med Dep J. 2008 Jul-Sep;:7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang HK, Bullman TA. Risk of suicide among US veterans after returning from the Iraq or Afghanistan war zones. JAMA. 2008 Aug 13;300(6):652–653. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuehn BM. Soldier suicide rates continue to rise: Military, scientists work to stem the tide. JAMA. 2009 Mar 18;301(11):1111–1113. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zivin K, Kim HM, McCarthy JF, Austin KL, Hoggatt KJ, Walters H, et al. Suicide mortality among individuals receiving treatment for depression in the Veterans Affairs health system: Associations with patient and treatment setting characteristics. Am J Public Health. 2007 Dec;97(12):2193–2198. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox J, Merwin E, Blank M. De facto mental health services in the rural south. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1995;6(4):434–468. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang PS, Berglund PA, Kessler RC. Patterns and correlates of contacting clergy for mental disorders in the United States. Health Serv Res. 2003 Apr;38(2):647–673. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chalfant HP, Heller PL, Roberts A, Briones D, Aguirre-Hochbaum S, Farr W. The clergy as a resource for those encountering psychological distress. Review of Religious Research. 1990;31(3):305–313. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blank MB, Mahmood M, Fox JC, Guterbock T. Alternative mental health services: The role of the black church in the South. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(10):1668–1672. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milstein G. Clergy and psychiatrists: Opportunities for expert dialogue. Psychiatric Times. 2003;XX(3):36–39. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sexton RL, Carlson RG, Siegal H, Leukefeld CG, Booth B. The role of African-American clergy in providing informal services to drug users in the rural South: Preliminary ethnographic findings. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2006;5(1):1–21. doi: 10.1300/J233v05n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrell JL, Goebert DA. Collaboration between psychiatrists and clergy in recognizing and treating serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2008 Apr;59(4):437–440. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weaver AJ. Has there been a failure to prepare and support parish-based clergy in their role as frontline community mental health workers: A review. J Pastoral Care. 1995;49(2):129–147. doi: 10.1177/002234099504900203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramer TL, Blevins D, Miller TL, Phillips MM, Davis V, Burris B. Ministers’ perceptions of depression: A model to understand and improve care. Journal of Religion and Health. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mannon JD, Crawford RL. Clergy confidence to counsel and their willingness to refer to mental health professionals. Family Therapy. 1996;23(3):213–231. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Openshaw L, Harr C. Exploring the relationship between clergy and mental health professionals. Social Work & Christianity. 2009;36(3):301–325. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Health Administration. 2010 Survey of Veteran Enrollees’ Health and Reliance Upon VA. [updated 2011; cited 2012 Jul 24]; Available from: http://www.va.gov/HEALTHPOLICYPLANNING/Soe2010/SoE_2010_Final.pdf.

- 21.Turbott J. Religion, spirituality and psychiatry: Steps towards rapprochement. Australas Psychiatry. 2004 Jun;12(2):145–147. doi: 10.1080/j.1039-8562.2004.02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leavey G, King M. The devil is in the detail: Partnerships between psychiatry and faith-based organisations. Br J Psychiatry. 2007 Aug;191:97–98. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.034686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. U.S. religious landscape survey. [updated 2012; cited 2012 Jul 20]; Available from: http://religions.pewforum.org/maps. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mattox R, McSweeney J, Ivory J, Sullivan G. A qualitative analysis of Christian clergy portrayal of anxiety disturbances in televised sermons. In: Miller AN, Rubin D, editors. Health communication and faith communities. New York: Hampton Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mattox R, Sullivan G. Treatment:“Just what the preacher ordered”. Psychiatric Services. 2008 Apr;59(4):349. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naylor PJ, Wharf-Higgins J, Blair L, Green L, O’Connor B. Evaluating the participatory process in a community-based heart health project. Soc Sci Med. 2002 Oct;55(7):1173–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christopher S, Watts V, McCormick AK, Young S. Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. Am J Public Health. 2008 Aug;98(8):1398–1406. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shelton D. Establishing the public’s trust through communitybased participatory research: A case example to improve health care for a rural Hispanic community. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2008;26:237–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]