Abstract

Triclosan (TCS) is a commonly used antimicrobial agent that enters wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) and the environment. An estimated 1.1 × 105 to 4.2 × 105 kg of TCS are discharged from these WWTPs per year in the United States. The abundance of TCS along with its antimicrobial properties have given rise to concern regarding its impact on antibiotic resistance in the environment. The objective of this review is to assess the state of knowledge regarding the impact of TCS on multidrug resistance in environmental settings, including engineered environments such as anaerobic digesters. Pure culture studies are reviewed in this paper to gain insight into the substantially smaller body of research surrounding the impacts of TCS on environmental microbial communities. Pure culture studies, mainly on pathogenic strains of bacteria, demonstrate that TCS is often associated with multidrug resistance. Research is lacking to quantify the current impacts of TCS discharge to the environment, but it is known that resistance to TCS and multidrug resistance can increase in environmental microbial communities exposed to TCS. Research plans are proposed to quantitatively define the conditions under which TCS selects for multidrug resistance in the environment.

Keywords: triclosan, antimicrobial resistance, antibiotic resistance, biosolids, wastewater

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization warns that we may enter a post-antibiotic era in the twenty-first century due to the spread of antibiotic resistance (World Health Organization [WHO], 2014). Antibiotic resistance is defined as the ability of bacteria to survive a concentration of antibiotics that typically inhibits growth of the majority of other bacteria (Russell, 2000). Antibiotics are extensively used in medicine to treat bacterial infections in humans and animals, and are widely used in agriculture to promote animal growth (Khachatourians, 1998; Kümmerer, 2004). Each year, in the United States (U.S.) alone, over two million people are infected by antibiotic resistant bacteria, leading to more than 25,000 deaths, and $50 billion spent managing antibiotic resistance (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], U.S. Department of Health, and Human Services, 2013). The associated cost continues to increase as bacteria acquire mechanisms to fight against the antibiotics that are typically employed (Levy and Marshall, 2004).

In addition to antibiotics, synthetic antimicrobial agents are also pervasive in households and hospitals, mainly for disinfection and sanitation purposes. The term “antimicrobial” has been used to describe a broad range of compounds, including antibiotics that destroy or inhibit microorganisms (McDonnell and Russell, 1999; Kümmerer, 2004). For this paper, triclosan (TCS), which is not derived naturally, is referred to as an antimicrobial. Compounds produced or derived from microorganisms used in vivo to treat bacterial infections in eukaryotes (e.g., erythromycin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, etc.) will be referred to as antibiotics (even though antibiotics are a subset of antimicrobials).

Triclosan is widely used for personal hygiene and disinfection purposes; in fact, 350 tons were produced for commercial use in the European Union in 2002. Based on 1998 records from the Environmental Protection Agency, approximately 500–5000 tons were produced in the U.S., and the industry has reported growth (Singer et al., 2002; Heidler and Halden, 2007; Fang et al., 2010; Venkatesan and Halden, 2014). With these approximations, it is estimated that 1 kg of TCS is produced for every 3 kg of antibiotics produced (Food and Drug Administration [FDA], 2011; Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2012). TCS is found in a wide range of consumer products including hand soap, toothpaste, deodorant, surgical scrubs, shower gel, hand lotion, hand cream, and mouthwash (Bhargava and Leonard, 1996; Jones et al., 2000).

Because of its wide use, TCS is found in many natural and engineered environments, including surface water, wastewater, soil, drinking water, wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), biosolids, landfills, and sediments (Singer et al., 2002; Miller and Heidler, 2008; Benotti et al., 2009; Kumar et al., 2010; Xia et al., 2010; Welsch and Gillock, 2011; Bedoux et al., 2012; Mavri et al., 2012). As TCS is commonly used in oral consumer products, it is widely found in human urine. In a survey of 181 pregnant women in an urban multiethnic population in Brooklyn, NY, TCS was found in 100% of urine samples (Pycke et al., 2014). In a geographically broader U.S. survey, 75% of people were found to have TCS in their urine (Calafat et al., 2008).

At application concentrations (0.1–0.3 w/v% or approximately 1,000–3,000 mg/L in hand soaps), TCS induces cell damage that causes cell contents to physically leak out of the membrane (Villalaín et al., 2001). At concentrations lower than 1 mg/L, TCS serves as an external pressure to select for TCS resistance as well as antibiotic resistance in many types of bacteria (Russell, 2000; Schweizer, 2001; Poole, 2002; Chapman, 2003; Yazdankhah et al., 2006; Birosová and Mikulásová, 2009; Saleh et al., 2011; Halden, 2014). At low concentrations, TCS interacts with physiological targets, and these interactions lead to numerous resistance mechanisms that are reviewed below (Chuanchuen et al., 2001; Bailey et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2010; Condell et al., 2012). In some cases, the mechanisms that convey resistance to TCS simultaneously confer resistance to more than one class of antibiotics (Poole, 2002; Alanis, 2005).

The wide use of TCS leads to concern about its potential to aid in the spread of antibiotic resistance (Russell, 2000; Kümmerer, 2004; Saleh et al., 2011). TCS exposure that leads to TCS resistance and antibiotic resistance has been widely reported, but the majority of these studies pertain to pure cultures of specific bacterial strains, and in most cases, pathogenic strains. This line of research is logical because antibiotic resistant pathogens are of greatest concern to public health. TCS might also impact the spread of resistance in environmental microbial communities as approximately 1.1 × 105 to 4.2 × 105 kg of TCS are distributed to the environment annually through WWTPs in the U.S. (Heidler and Halden, 2007). Studies on pure culture isolates provide insight into the potential impacts of TCS on antibiotic resistance in environmental bacterial communities. The important question then becomes: does TCS select for antibiotic resistance in these complex microbial communities?

Many engineered and natural processes are driven by microbes, and TCS is designed to impact microbes in homes and hospitals. Following discharge to the environment, the antimicrobial properties of TCS can impact complex microbial communities found in engineered and environmental systems. TCS has been linked to altering microbial community structure or function in wastewater operations, such as activated sludge and anaerobic digestion (Stasinakis et al., 2008; McNamara et al., 2014). Likewise, TCS can alter diversity and biofilm development in freshwater biofilms in receiving streams (Johnson et al., 2009; Proia et al., 2011; Lubarsky et al., 2012). In soils, TCS impacts respiration rates and denitrification, and enriches for species capable of dehalogenation (Butler et al., 2011; McNamara and Krzmarzick, 2013; Holzem et al., 2014). TCS induces responses in microbial communities, but the TCS concentrations that inhibit function are not often found in these complex microbial communities. At environmental concentrations, TCS is more likely to exert a stress that propagates resistance than to exert a stress that functionally inhibits complex microbial communities.

The purpose of this manuscript is to review the state of knowledge regarding the impact of TCS on antibiotic resistance in environmental systems and identify critical research questions that need to be addressed to better understand the impact of TCS-derived resistance in the environment on public health. This review describes TCS resistance and cross-resistance in pure cultures, and then considers the comparatively smaller amount of literature that addresses how TCS impacts antibiotic resistance in engineered environments containing complex microbial communities. Engineered environments are of prime interest because they contain TCS, bacteria, and resistance genes that can be subsequently dispersed to terrestrial soils and surface waters with the possibility of negative public health consequences (Pruden et al., 2006, 2012; Baquero et al., 2008; Cha and Cupples, 2009; Ghosh et al., 2009; Munir et al., 2010; LaPara et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2011; Burch et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2014).

GENETIC TARGETS OF TRICLOSAN

In 1998, TCS was first described by McMurry et al. (1998b) to have a specific target in Escherichia coli. At 1 mg/L, approximately 1000-fold lower than the application concentration, TCS inhibits FabI, an enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase (ENR). The FabI protein catalyzes the elongation cycle in the synthesis of fatty acids, an essential process for cell viability (Bergler et al., 1996; Massengo-Tiassé and Cronan, 2008, 2009). Prior to McMurry et al.’s (1998b) report, low concentrations of TCS were assumed to have minimal effects on cell viability.

Up-regulation of fabI is a response mechanism which may overcome the effects of intracellular TCS (Condell et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2012; Sheridan et al., 2013). Bacteria can up-regulate and down-regulate many more genes in response to TCS, although it can be difficult to determine which expression changes are casual. No universal response has been observed; however, many bacteria respond to some degree with the up-regulation of transport proteins and membrane bound proteins (Bailey et al., 2008; Chuanchuen and Schweizer, 2012).

TCS RESISTANCE IN PURE CULTURES

The most common resistance mechanisms based on pure culture studies are target site modification, membrane resistance, and efflux. The following sections briefly review resistance mechanisms to TCS and describe their impact on cross-resistance; a comprehensive review of TCS resistance mechanisms can be found by Schweizer (2001).

FABI MODIFICATION OR REPLACEMENT

Target site modification is a resistance mechanism that involves a genetic alteration to the target site that reduces the effect of an inhibitory chemical (Hooper, 2005). Modification of TCS target site FabI is a common resistance mechanism observed in pure cultures. Mutation occurs whereby single or multiple amino acids are changed in the fabI gene, resulting in TCS-resistant FabI proteins (Brenwald and Fraise, 2003; Yu et al., 2010). Ciusa et al. (2012) suggested a resistance mechanism whereby an allele of a fabI gene is located on a mobile genetic element and transposed into Staphylococcus aureus. The presence of the fabI allele together with the intrinsic fabI gene increased the concentration of the FabI protein through heterologous duplication and increased bacterial tolerance to TCS. Alternatively, ENR isoenzymes, which perform similar functions to FabI, including FabL, FabK, and FabV, have been identified in TCS-resistant bacteria (Massengo-Tiassé and Cronan, 2009). These isoenzymes are naturally found in some strains of bacteria. In fact, FabV has been found to functionally replace FabI, rendering Pseudomonas aeruginosa 2,000 times more resistant to TCS as seen by an increase in minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC; Zhu et al., 2010). Similarly, FabK replaces function for FabI in Streptococcus pneumonia, leading to increased tolerance to TCS (Heath et al., 2000), and FabL expression leads to increased resistance to TCS in Bacillus subtilis (Heath et al., 2000).

With respect to multidrug resistance, FabI alteration or replacement may specifically produce resistance to isoniazid, an important agent for the treatment of tuberculosis, which also targets FabI (Ciusa et al., 2012). However, FabI alterations are not generally known to cause resistance to other antibiotics. This type of resistance in environmental communities would not likely pose a threat to public health through increased multidrug resistance.

MEMBRANE ALTERATION

Modifications through changes to the outer membrane is a less-studied TCS resistance mechanism in bacteria. Champlin et al. (2005) concluded that outer membrane properties were responsible for low-level resistance to hydrophobic antimicrobials and antibiotics. The researchers compared P. aeruginosa strains that possessed highly refractory outer cell envelopes to strains that had highly permeable outer cell envelopes and discovered that the outer membrane properties conferred intrinsic resistance to TCS up to 256 mg/L. Tkachenko et al. (2007) suggested that TCS exposure could induce a genetic response which increases the concentration of branched chain fatty acids in the cell membrane in S. aureus; the membrane thereby sequesters the chemical agent and stops it from passing into the cell, preventing physiological disruption inside of the cell.

Outer membrane impermeability is a potential mechanism for cross-resistance to antibiotics. Particularly, non-specific rejection of hydrophobic chemicals could be a mechanism for resistance to TCS and other antibiotics that may be found in the environment.

EFFLUX PUMPS

Efflux pumps are often associated with multidrug resistance, which is a public health concern. Active efflux, whereby a bacterium physically removes a constituent from its intracellular space by pumping the constituent across the membrane and back into the environment, is an effective mechanism against a wide range of antimicrobials and antibiotics, including TCS (Kern et al., 2000; Levy, 2002). The AcrAB efflux pump is responsible for efflux of TCS in E. coli and Salmonella enterica (McMurry et al., 1998a; Webber et al., 2008). Non-specific multidrug efflux pumps (e.g., mex proteins) confer resistance to TCS as well as other antibiotics in P. aeruginosa and Rhodospirillum rubrum (Chuanchuen et al., 2001; Pycke et al., 2010a,b). Most non-specific efflux pumps are capable of expulsing antibiotics. Thus, in cases where bacteria acquire non-specific efflux pumps through horizontal gene transfer after exposure to TCS, the bacteria would likely acquire resistance to antibiotics as well. In some cases specific efflux pumps confer resistance to TCS. TriABC-OpmH is a TCS-specific efflux pump in P. aeruginosa that is not known to expel other compounds such as antibiotics (Mima et al., 2007).

TRICLOSAN AND CROSS-RESISTANCE TO ANTIBIOTICS

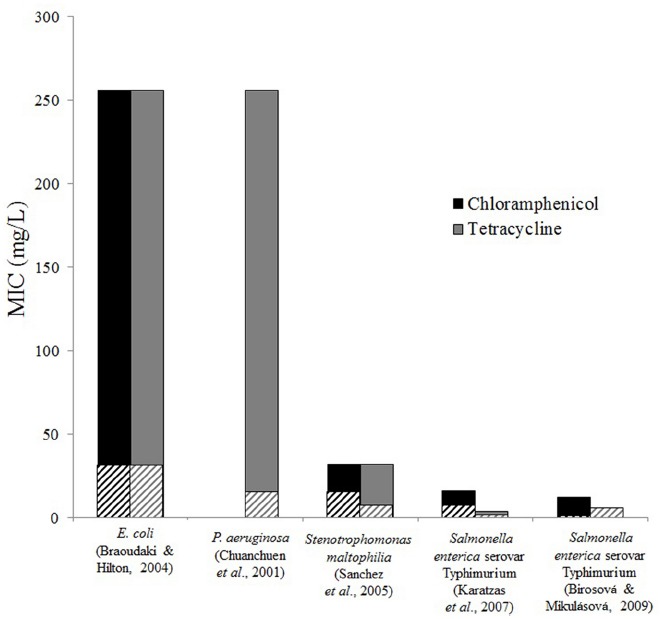

Resistance to TCS, incurred by exposure to TCS, can directly affect resistance to antibiotics. Cross-resistance has been tested for a wide range of antibiotics following exposure to TCS. Chloramphenicol and tetracycline are two antibiotics commonly included in antibiotic cross-resistance experiments. In studies done on E. coli and P. aeruginosa, resistance to chloramphenicol and tetracycline increased 10-fold following TCS exposure (Figure 1). Increased antibiotic resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium following TCS exposure was also observed, but the increase was less severe. Cross resistance in P. aeruginosa (Chuanchuen et al., 2001), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (Sanchez et al., 2005), and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (Karatzas et al., 2007) were attributed to efflux systems. Resistance mechanisms were not directly investigated in the studies on E. coli (Braoudaki and Hilton, 2004) and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (Birosová and Mikulásová, 2009), however acrAB genes, which encode for efflux, are known to confer resistance to TCS, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline in both of these species (Karatzas et al., 2007). These findings highlight a main concern regarding the widespread dissemination of TCS, i.e., that TCS exposure can spread multidrug resistance.

FIGURE 1.

Triclosan exposure increases resistance to antibiotics. Minimum inhibitory concentrations of chloramphenicol and tetracycline for control strains (striped bars) and TCS adapted strains (solid bars) are shown from various studies and bacteria. Differences were observed in most cases, however, no difference was found for tetracycline resistance for Salmonella enterica in the study by Birosová and Mikulásová (2009). Chloramphenicol resistance was not tested in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Chuanchuen et al., 2001).

Triclosan resistance and antibiotic resistance have been found together in clinical isolates. In a survey of 732 clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii from hospitals, 3% of isolates were found to have reduced susceptibility to TCS (MIC > 1 mg/L; Chen et al., 2009). Those isolates which could tolerate higher than 4 mg/L also had increased tolerance to amikacin, tetracycline, levofloxacin and imipenem. Clinical isolates of S. aureus, which had MICs to TCS between 0.025 and 1 mg/L, were resistant to multiple antibiotics (Suller and Russell, 2000). Some, but not all, of the strains showed increased resistance to gentamicin, erythromycin, penicillin, rifampicin, fusidic acid, tetracycline, methicillin, mupirocin, and streptomycin. In some strains TCS resistance was stable when sub-culturing was performed in a TCS-free medium. In other strains TCS resistance was lost when the strain was propagated for 10 days in TCS-free media, indicating that the presence of TCS can select for resistance that is not regularly expressed. This finding implies that removing TCS from environmental systems through improved treatment processes or reduced consumer usage could lead to a decrease in TCS resistance. Research should be conducted to specifically test the impacts of removing TCS on TCS-derived resistance in complex microbial communities.

Conditions that perpetuate resistance to TCS frequently result in cross-resistance to antibiotics. TCS resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains were selected by daily sub-culturing of TCS-exposed cultures and increasing TCS concentrations in media from 0.05 to 15 mg/L over 15 days (Karatzas et al., 2007). The TCS MIC in the resulting strains increased from 0.06 mg/L to as high as 128 mg/L, and the strains were also more resistant to ampicillin, tetracycline, and kanamycin. The authors concluded that the overexpression of the acrAB efflux pump was likely involved in the increased tolerance to TCS and antibiotics. In another study, TCS selected for ciprofloxacin resistant mutants in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium when exposed to 0.5 mg/L of TCS (Birosová and Mikulásová, 2009). These studies, along with the concentrations of TCS found in the environment, imply that TCS could select for bacteria in environmental communities that have efflux pumps.

Efflux is a common method of resistance, but the specific efflux system used and the resulting cross-resistance profile can vary between species. In P. aeruginosa, MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexEF-OprN, contribute to TCS resistance (Chuanchuen et al., 2001). Exposure to TCS selected for up-regulation of these efflux systems due to mutations in the regulatory gene, nfxB, which increased the tolerance to tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim, erythromycin, and gentamicin. In some cases the TCS resistant strains could tolerate up to 500-fold higher antibiotic concentrations than the non-TCS resistant strains. Strains which lacked these efflux systems showed increased sensitivity to antibiotics. In the opportunistic pathogen Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, TCS binds to the repressor SmeT, allowing expression of an efflux pump, SmeDEF (Hernández et al., 2011). Expression of this efflux pump following exposure to TCS resulted in increased resistance to the antibiotics ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, nalidixic, and ofloxacin. Sanchez et al. (2005) also found that TCS-resistant mutants of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (tolerant up to 64 μg/L of TCS) overexpress SmeDEF. These mutants had an increased tolerance to tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and ciprofloxacin. Even though SmeDEF is intrinsically contained in the genome of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, TCS exposure selected for up-regulation of this efflux pump which increased antibiotic resistance.

In addition to variances between genera, cross-resistance varies within genera. TCS-adapted E. coli O157:H7 exhibited increased resistance to chloramphenicol, tetracycline, amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, trimethoprim, benzalkonium chloride, and chlorhexidine, while TCS-adapted E. coli O55 exhibited resistance to only trimethoprim (Braoudaki and Hilton, 2004).

Although most evidence supports the notion that TCS increases resistance to antibiotics, this is not necessarily true for all classes of antibiotics. In one case, TCS-resistant mutants of Salmonella enterica were more (or no less) susceptible to antibiotics (Rensch et al., 2013). Salmonella enterica that were selected to have overexpression of fabI or a fabI mutation had increased susceptibility to the aminoglycoside antibiotics kanamycin and gentamicin.

The cross-resistance profiles vary among the bacteria surveyed in this review, and other types of bacteria yet to be studied are likely to have unique cross-resistance profiles. While resistance profiles vary, the overarching theme is the same: resistance to TCS can yield cross-resistance to multiple antibiotics. Given that TCS is not an antibiotic, resistance to TCS alone is not a public health threat. TCS-derived proliferation of multidrug resistant bacteria, however, could be a severe threat to public health. These pure culture studies indicate that TCS is likely to select for multidrug resistant bacteria above a critical concentration. In environmental communities, such as anaerobic digesters or sediments, TCS is found at 2- to 1000-fold higher concentrations than any given antibiotic (McClellan and Halden, 2010). Is TCS selecting for resistant bacteria in the environment? The role of TCS on the selection of antibiotic resistance genes and multidrug resistance genes in the environment needs to be quantified to determine what steps, if any, are necessary for protecting public health.

TRICLOSAN-DERIVED RESISTANCE IN COMPLEX ENVIRONMENTAL COMMUNITIES

Environmental systems, including WWTPs and sediments, represent the most likely sites for TCS resistance to develop because of the high abundance of TCS and high density of bacteria. Wastewater treatment systems should be given special focus because they contain and discharge TCS and resistance genes to the environment. To understand the role of TCS and the remaining research gaps, the fate of TCS in the environment is summarized to highlight locations of prime interest, and the state of knowledge regarding TCS and resistance in complex microbial communities is assessed.

FATE OF TRICLOSAN

Triclosan is discharged into the environment with treated liquid and solid effluents from WWTPs. In the U.S. alone, WWTPs are estimated to receive approximately 100 tons of TCS each year, but the prevalence of TCS in treated effluent is not restricted to U.S. facilities. A survey of WWTPs in Germany found TCS in treated effluents at concentrations ranging from 1 × 10–5 to 6 × 10–4 mg/L (Bester, 2005). The concentrations of TCS and its aerobic degradation products in receiving waters were less than 3 × 10–6 mg/L. A study of eight WWTPs in Switzerland revealed that, on average, 6% of the influent TCS was found to discharge with the effluent water at concentrations of 4.2 × 10–5 to 2.13 × 10–4 mg/L (Singer et al., 2002); these receiving streams had concentrations at 1.1 × 10–5 to 9.8 × 10–5 mg/L. A more recent study found TCS in WWTP effluents at 9.7 × 10–5 mg/L, and in nearby sediments at 0.018 mg/kg (Blair et al., 2013). Several other studies have found TCS in surface water in concentrations ranging from <2 × 10–7 mg/L up to 0.022 mg/L (Bedoux et al., 2012).

Triclosan that is discharged with liquid effluent often partitions to sediments. Miller and Heidler (2008) found that TCS accumulated in sediments near WWTP outfalls for approximately 50 years, and similar results were found by other researchers (Buth et al., 2010; Anger et al., 2013). Sediment concentrations have been found at 53 mg/kg (Chalew and Halden, 2009). TCS is prevalent in liquid effluents and abundant in sediments, but this discharge route does not account for the majority of TCS that enters the environment. One study estimated that 0.24 kg/day of TCS are released with liquid effluent, but 5.37 kg/day are released with the treated residual solids from a midsized WWTP (Lozano et al., 2013).

Indeed, nearly half (or even higher) of the influent TCS load to WWTPs is captured by solids following sorption (Heidler and Halden, 2007; Lozano et al., 2013). The concentration of TCS in biosolids is often much higher than in aqueous systems because of the hydrophobic nature of TCS (Heidler and Halden, 2008). A nationwide U.S. survey of TCS in biosolids found the median concentration in treated biosolids to be 3.9 mg/kg and the maximum level was 133 mg/kg (United States Environmental Protection Agency [USEPA], 2009). The high levels found in biosolids can lead to high levels in soils when biosolids are land applied. TCS was found in biosolids-amended soils which had been receiving biosolids for 33 years (Xia et al., 2010). The concentrations in the soil ranged from approximately 1 mg/kg in the first 15 cm of soil to less than 0.1 mg/kg at a depth of 60–120 cm. The half-life of TCS in soil under aerobic conditions was 104 days, and TCS is even more persistent under anaerobic conditions (McAvoy et al., 2002; Ying et al., 2007). These fate data, along with the hydrophobic nature of TCS, indicate that TCS is most likely to impact microbial communities that contain high concentrations of organic matter, including anaerobic digesters, sediments, and soils, and these communities should receive special focus when investigating TCS-derived resistance in the environment.

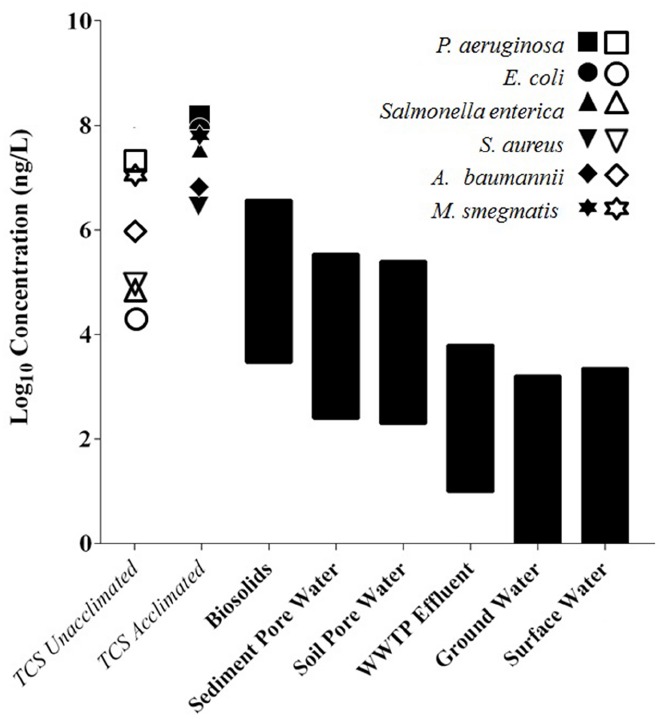

The range of TCS concentrations found in the environment is depicted in Figure 2 along with the MIC of TCS-acclimated and TCS-unacclimated pathogenic strains of bacteria. The concentrations in the biosolids and sediments are higher than the MICs of TCS-sensitive strains, indicating that TCS-sensitive strains would not thrive in these environments and TCS-resistant strains may be present. The MICs of TCS-acclimated strains, however, are higher than the current environmental TCS concentrations and could tolerate an increase in TCS concentrations. A future increase in TCS concentrations may select for resistance rather than functionally inhibit complex microbial communities. This figure indicates that biosolids and sediment environments with high TCS concentrations likely have TCS-resistant bacteria, but this figure does not indicate the level of TCS required to select or enrich for resistance in the environments with lower TCS concentrations. What happens when TCS is below the MIC? Certainly environments with very high levels of TCS will have TCS-resistant strains, but do environments with TCS concentrations below the MIC of acclimated strains select for resistance? What concentration of TCS is required to select for resistance in various environmental communities? These questions represent critical research gaps. By answering these questions with further research we can determine if and where TCS is selecting for resistance. Research plans are outlined in the final section to address these questions.

FIGURE 2.

The MIC of TCS-acclimated and TCS-unacclimated strains relative to environmental TCS concentrations. Open symbols represent the MIC for TCS sensitive strains, while closed symbols represent the MIC for TCS adapted strains. Black bars are ranges of TCS concentrations found in each environmental setting. Biosolids concentrations were converted from mg/kg to mg/L by assuming 3% total solids in reactors that produce biosolids (McMurry et al., 1998a, 1999; Chuanchuen et al., 2001; Slater-Radosti et al., 2001; Fan et al., 2002; Yazdankhah et al., 2006; Karatzas et al., 2007; Mima et al., 2007; Tkachenko et al., 2007; Bailey et al., 2008; Webber et al., 2008; Chalew and Halden, 2009; Chen et al., 2009; McClellan and Halden, 2010; Yu et al., 2010; Saleh et al., 2011; Bedoux et al., 2012).

TRICLOSAN RESISTANCE IN COMPLEX MICROBIAL COMMUNITIES

Bacteria with resistance to TCS are found in the environment, and experiments have been performed to determine whether TCS could be the cause for resistance. Drury et al. (2013) constructed artificial streams to control for other selective pressures such as antibiotics. The artificial streams were inoculated with approximately 8 mg/L of TCS. Over 34 days, the relative abundance of benthic bacteria which were able to be cultivated in 16 mg/L of TCS in agar climbed from 0 to 14%. In a similar study, TCS was added to artificial stream mesocosms at 1 × 10–4, 5 × 10–4, 1 × 10–3, 5 × 10–3, and 1 × 10–2 mg/L, and resistance to TCS significantly increased in bacterial populations exposed to TCS concentrations over 5 × 10–4 mg/L (Nietch and Quinlan, 2013). This study was conducted at environmentally relevant concentrations, and suggested that TCS exposure leads to TCS-resistance. Middleton and Salierno (2013) discovered that TCS resistance was detected in 78.8% of fecal coliform samples from streams receiving wastewater, and 89.6% of these samples were resistant to four classes of antibiotics. Escherichia, Enterobacter, Serratia, and Citrobacter were also found in the stream with resistance to TCS and multiple antibiotics. This study investigated real-world surface water samples which are implicitly associated with many uncontrolled variables. Accordingly, it infers, but does not prove, that TCS may be an external stressor that results in increased abundance of resistance genes.

Studies on the impacts of TCS on anaerobic digesters, where TCS is of highest abundance, are lacking. Lab-scale studies revealed that TCS can affect multidrug resistance genes in anaerobic bioreactors. McNamara et al. (2014) found that TCS at 500 mg/kg selected for mexB in lab-scale anaerobic digesters inoculated with cow manure. In anaerobic digesters that were seeded with municipal biosolids, 500 mg/kg did not select for mexB, but methane production was inhibited. It is not yet known if anaerobic communities need to carry resistance genes in order to maintain function at these high TCS levels. The findings indicated that the microbial community structure, in addition to the concentration of TCS, influences the selection of resistance genes. Also, this research demonstrated that TCS can select for resistance, but does selection happen at environmental concentrations of TCS? Similarly, in activated sludge mesocosms, TCS selected for tetQ at 0.3 mg/L of TCS (Son et al., 2010). These two wastewater studies found a correlation between the presence of a resistance gene and TCS, but each study only investigated a single gene. A much more thorough research effort is required to determine the breadth of genes, with a special emphasis on multidrug resistance genes, that are selected for when environmental concentrations of TCS are applied to the complex microbial communities found in WWTPs.

It is also possible that TCS-resistant bacteria are formed in premise plumbing which can feed into municipal WWTPs. In a sink drain biofilm, TCS was shown to affect the bacterial population structure when a 0.2% (∼2000 mg/L) solution of soap containing TCS was pumped over the biofilm (Mcbain et al., 2003). Overall bacterial diversity was reduced and several TCS-resistant bacteria related to Achromobacter xylosoxidans increased in abundance, while other species including aeromonads, bacilli, chryseobacteria, klebsiellae, stenotrophomonads, and Microbacterium phyllosphaerae were reduced. TCS in a drain following consumer usage may result in resistant bacteria which are then sent to WWTPs. Research is needed to determine if these bacteria survive in the sewer system and whether these resistant bacteria influence the resistance profile in WWTPs.

These studies show that TCS in the environment could select for resistance genes. It seems likely that TCS resistance coincides with TCS-derived cross-resistance to antibiotics in the environment, but further studies are required to validate this point.

RESEARCH GAPS AND CONCLUSIONS

It is noted that pathogenic bacteria, such as S. epidermidis, are less susceptible to TCS today than they were in the past (Skovgaard et al., 2013). Although resistance to TCS alone is not a threat to human health, antibiotic resistance is a major public health concern. TCS is widespread throughout the environment, but the direct role of TCS on antibiotic resistance in environmental systems is not yet defined. Four specific research questions, which are outlined below, need to be answered to identify the role of TCS on antibiotic resistance in environmental systems and ultimately determine the impact on human health.

IDENTIFY THE ROLE OF TRICLOSAN ON ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE IN ENVIRONMENTAL SYSTEMS

What is the threshold concentration of TCS that triggers resistance?

Triclosan is found at a wide range of concentrations in a wide range of environments (see Figure 2), and previous work found that TCS can select for a resistance gene in a complex microbial community (Son et al., 2010; McNamara et al., 2014). Moving forward it is important to determine the concentrations of TCS that trigger an increase in antibiotic resistance genes. Answering this question will also help address the question framed by the lack of data in Figure 2, i.e., what is the effect of TCS concentrations below the MIC? Do low levels of TCS select for resistance? Chronic exposure experiments using lab mesocosms should be performed at a range of steady-state TCS concentrations. In most real world cases, TCS levels will slowly increase, and lab experiments should be designed to reflect this slow loading rate. TCS levels should be slowly increased over time and held constant during steady-state operation of the mesocosm to determine the concentration of TCS that sustains changes in antibiotic resistance profiles. Metagenomics can be used with the Antibiotic Resistance Genes Database (Liu and Pop, 2009) to determine how the concentration of TCS impacts the relative abundance of antibiotic resistance genes. Additionally, qPCR can be employed to quantify changes in resistance gene abundance. After completion of these experiments we will have a better understanding about the concentrations of TCS that trigger increases in antibiotic resistance genes.

What is the role of the microbial community composition on TCS-derived antibiotic resistance?

Previous work revealed that the same concentration of TCS can lead to different impacts on the abundance of a resistant gene depending on the microbial community (McNamara et al., 2014). Experiments outlined in the question above should be performed on several different microbial communities. For example, communities found in river sediments, soils, and anaerobic digesters, should be investigated, and experiments should also be performed on several different communities from each type of environment. Wastewater communities can vary widely in their structure and so could the impact of TCS on resistance in these communities. Mesocosms should be inoculated with biosolids from several different cities to quantify how the same TCS concentrations impact the antibiotic resistance profiles of different communities. Is there a universal TCS concentration that is of concern in anaerobic digester communities, in sediments, or in soils? Illumina sequencing on 16S rRNA genes should be performed as well to determine if a link exists between certain microbes in a community and the TCS-impacted resistance profile.

What is the impact of TCS on resistance profiles in environments that are also perturbed by antibiotics?

Some resistance mechanisms, mainly efflux pumps, which are triggered by TCS are also triggered by antibiotics. In environments perturbed by TCS, antibiotics are also present (e.g., McClellan and Halden, 2010). Does the presence of TCS impact the acquisition of antibiotic resistance genes through horizontal gene transfer when antibiotics are already present? In other words, if TCS were not in these environments would the resistance profile look the same? To help answer this question, mesocosms could be inoculated with complex microbial communities from environments that are not heavily impacted by antibiotics or TCS. One set of mesocosms could be amended with antibiotics and another set would be amended with antibiotics and TCS. It is important to add TCS and antibiotics at ratios typically found in the environment. Granted, this question is difficult to answer because complex microbial communities from pristine environments will have inherent differences from the communities that are typically exposed to TCS and antibiotics. Another possibility would be to use a microbial community that has been widely exposed to antibiotics but not exposed to TCS; this type of community might be readily found in countries that have not adopted wide-spread use of TCS. Molecular techniques described above could be employed to determine the added impact of TCS on antibiotic resistance gene profiles.

Will the abundance of resistance genes decrease if TCS concentrations decrease?

It is important to know the concentrations of TCS that select for resistance and the communities that are most vulnerable to resistance caused by TCS, but it is equally important to know if resistance caused by TCS is reversible. Mitigated use of TCS has been proposed in the U.S. in part because of the potential concerns over antibiotic resistance (Landau and Young, 2014). If there were to be a sudden decline in consumer usage, would TCS-resistance and associated multidrug resistance decrease? Experiments should be performed where TCS is slowly increased to encourage TCS-resistance and the mesocosms should be operated at steady-state with a constant supply of TCS. After the resistance profiled is determined, TCS should be removed from the system while the mesocosms are maintained under TCS-free conditions. The resistance profile can then be quantified after TCS is washed out of the mesocosms to determine if TCS-derived resistance will decrease as TCS levels decrease. This set of experiments would help to determine the potential impacts of reducing TCS from environmental systems.

IDENTIFY THE IMPACT OF TRICLOSAN-DERIVED RESISTANCE IN THE ENVIRONMENT ON PUBLIC HEALTH

Complex microbial environments can be highly conducive for the transfer of resistance genes (Baquero et al., 2008). Locations with high densities of bacteria, such as WWTPs, produce conditions which are suitable for proliferation and exchange of resistance genes, and TCS may be serving as a selective pressure to increase the abundance of resistance genes in these communities. In a study focusing on plasmid genes found in activated sludge, a wide array of resistance genes, including genes that confer resistance to TCS in pure cultures (mexB, and other efflux pump homologues including acrB and smeE) were found on plasmids (Zhang et al., 2011). Research is needed to address the fate of environmentally derived resistance genes to understand how they impact human health.

The fate and transport of these resistance genes in the environment following discharge from WWTPs is not well defined. Transport of genes can occur through direct uptake of DNA (transformation), by viral infection (transduction), or by transfer of plasmids and other mobile genetic elements (conjugation); the resulting pathways for genetic transport are complicated to constrain for modeling (Baquero et al., 2008). Genetic tracking of resistance in the environment would require vast resources; using established models of viruses or bacteria may be an appropriate place to begin modeling resistance gene transport.

The rate of transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in the environment to humans is also under investigation (Viau et al., 2011; Ashbolt et al., 2013). Better understanding the threat of environmentally derived antibiotic resistance genes on human health is required to determine the role of TCS on public health. Employing quantitative microbial risk assessment for antibiotic resistance genes in environmental systems may be a useful avenue for pursuing this topic.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Daniel E. Carey was supported by the Joseph A. and Dorothy C. Rutkauskas Scholarship. We would like to thank Tucker Burch and two anonymous reviewers for their comments on this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Alanis A. J. (2005). Resistance to antibiotics: are we in the post-antibiotic era? Arch. Med. Res. 36, 697–705. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anger C. T., Sueper C., Blumentritt D. J., McNeill K., Engstrom D. R., Arnold W. A. (2013). Quantification of triclosan, chlorinated triclosan derivatives, and their dioxin photoproducts in lacustrine sediment cores. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 1833–1843. 10.1021/es3045289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashbolt N. J., Amézquita A., Backhaus T., Borriello P., Brandt K. K., Collignon P., et al. (2013). Human health risk assessment (HHRA) for environmental development and transfer of antibiotic resistance. Environ. Health Perspect. 121, 993–1001. 10.1289/ehp.1206316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A. M., Paulsen I. T., Piddock L. J. V. (2008). RamA confers multidrug resistance in Salmonella enterica via increased expression of acrB, which is inhibited by chlorpromazine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 3604–3611. 10.1128/AAC.00661-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baquero F., Martínez J. L., Cantón R. (2008). Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in water environments. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 19, 260–265. 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedoux G., Roig B., Thomas O., Dupont V., Le Bot B. (2012). Occurrence and toxicity of antimicrobial triclosan and by-products in the environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 19, 1044–1065. 10.1007/s11356-011-0632-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benotti M. J., Trenholm R. A., Vanderford B. J., Holady J. C., Stanford B. D., Snyder S. A. (2009). Pharmaceuticals and endocrine disrupting compounds in U.S. drinking water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 597–603. 10.1021/es801845a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergler H., Fuchsbichler S., Hogenauer G., Turnowsky F. (1996). The enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase (FabI) of Escherichia coli, which catalyzes a key regulatory step in fatty acid biosynthesis, accepts NADH and NADPH as cofactors and is inhibited by palmitoyl-CoA. Eur. J. Biochem. 242, 689–694. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0689r.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bester K. (2005). Fate of triclosan and triclosan-methyl in sewage treatment plants and surface waters. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 49, 9–17. 10.1007/s00244-004-0155-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava H., Leonard P. (1996). Triclosan: applications and safety. Am. J. Infect. Control 24, 209–218 10.1016/S0196-6553(96)90017-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birosová L., Mikulásová M. (2009). Development of triclosan and antibiotic resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Med. Microbiol. 58, 436–441. 10.1099/jmm.0.003657-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair B. D., Crago J. P., Hedman C. J., Treguer R. J. F., Magruder C., Royer L. S., et al. (2013). Evaluation of a model for the removal of pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and hormones from wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 444, 515–521. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.11.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braoudaki M., Hilton A. C. (2004). Low level of cross-resistance between triclosan and antibiotics in Escherichia coli K-12 and E. coli O55 compared to E. coli O157. FEMS microbiology letters. 235, 305–309. 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.04.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenwald N., Fraise A. (2003). Triclosan resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). J Hosp. Infect. 55, 141–144 10.1016/S0195-6701(03)00222-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch T. R., Sadowsky M. J., Lapara T. M. (2014). Fate of antibiotic resistance genes and class 1 integrons in soil microcosms following the application of treated residual municipal wastewater solids. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 5620–5627. 10.1021/es501098g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buth J. M., Steen P. O., Sueper C., Blumentritt D., Vikesland P. J., Arnold W. A., et al. (2010). Dioxin photoproducts of triclosan and its chlorinated derivatives in sediment cores. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 4545–4551. 10.1021/es1001105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler E., Whelan M. J., Ritz K., Sakrabani R., van Egmond R. (2011). Effects of triclosan on soil microbial respiration. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 30, 360–366. 10.1002/etc.405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calafat A. M., Ye X., Wong L. Y., Reidy J. A., Needham L. L. (2008). Urinary concentrations of triclosan in the U.S. population: 2003–2004. Environ. Health Perspect. 116, 303–307. 10.1289/ehp.10768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health, and Human Services. (2013). REPORT—Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1–114. [Google Scholar]

- Cha J., Cupples A. M. (2009). Detection of the antimicrobials triclocarban and triclosan in agricultural soils following land application of municipal biosolids. Water Res. 43, 2522–2530. 10.1016/j.watres.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalew T. E., Halden R. U. (2009). Environmental exposure of aquatic and terrestrial biota to triclosan and triclocarban. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 45, 4–13. 10.1111/j.1752-1688.2008.00284.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champlin F. R., Ellison M. L., Bullard J. W., Conrad R. S. (2005). Effect of outer membrane permeabilisation on intrinsic resistance to low triclosan levels in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 26, 159–164. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman J. S. (2003). Biocide resistance mechanisms. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 51, 133–138 10.1016/S0964-8305(02)00097-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Pi B., Zhou H., Yu Y., Li L. (2009). Triclosan resistance in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Med. Microbiol. 58, 1086–1091. 10.1099/jmm.0.008524-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuanchuen R., Beinlich K., Hoang T. T., Becher A., Karkhoff-Schweizer R. R., Schweizer H. P. (2001). Cross-Resistance between triclosan and antibiotics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is mediated by multidrug efflux pumps: exposure of a susceptible mutant strain to triclosan selects nfxB mutants overexpressing MexCD-OprJ. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 428–432. 10.1128/AAC.45.2.428-432.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuanchuen R., Schweizer H. P. (2012). Global transcriptional responses to triclosan exposure in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 40, 114–122. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciusa M. L., Furi L., Knight D., Decorosi F., Fondi M., Raggi C., et al. (2012). A novel resistance mechanism to triclosan that suggests horizontal gene transfer and demonstrates a potential selective pressure for reduced biocide susceptibility in clinical strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 40, 210–220. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condell O., Sheridan Á., Power K. A., Bonilla-Santiago R., Sergeant K., Renaut J., et al. (2012). Comparative proteomic analysis of Salmonella tolerance to the biocide active agent triclosan. J. Proteom. 75, 4505–4519. 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.04.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). (2012). Drug Use Review Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/UCM319435.pdf [accessed October 8, 2014].

- Drury B., Scott J., Rosi-Marshall E. J., Kelly J. J. (2013). Triclosan exposure increases triclosan resistance and influences taxonomic composition of benthic bacterial communities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 8923–8930. 10.1021/es401919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan F., Yan K., Wallis N. (2002). Defining and combating the mechanisms of triclosan resistance in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 3343–3347. 10.1128/AAC.46.11.3343-3347.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J. L., Stingley R. L., Beland F. A., Harrouk W., Lumpkins D. L., Howard P. (2010). Occurrence, efficacy, metabolism, and toxicity of triclosan. J. Environ. Sci. Health C Environ. Carcinog. Ecotoxicol. Rev. 28, 147–171. 10.1080/10590501.2010.504978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2011). Summary Report On Antimicrobials Sold or Distributed for Use in Food-Producing Animals Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ForIndustry/UserFees/AnimalDrugUserFeeActADUFA/UCM338170.pdf [accessed October 8, 2014].

- Ghosh S., Ramsden S. J., LaPara T. M. (2009). The role of anaerobic digestion in controlling the release of tetracycline resistance genes and class 1 integrons from municipal wastewater treatment plants. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 84, 791–796. 10.1007/s00253-009-2125-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halden R. U. (2014). On the need and speed of regulating triclosan and triclocarban in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 3603–3611 10.1021/es500495p [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath R. J., Rock C. O. (2000). A triclosan-resistant bacterial enzyme. Nature 406, 145–146. 10.1038/35018162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath R. J., Su N., Murphy C. K., Rock C. O. (2000). The enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductases FabI and FabL from Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 40128–40133. 10.1074/jbc.M005611200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidler J., Halden R. U. (2007). Mass balance assessment of triclosan removal during conventional sewage treatment. Chemosphere 66, 362–369. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.04.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidler J., Halden R. U. (2008). Meta-analysis of mass balances examining chemical fate during wastewater treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 6324–6332. 10.1021/es703008y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández A., Ruiz F. M., Romero A., Martínez J. L. (2011). The binding of triclosan to SmeT, the repressor of the multidrug efflux pump SmeDEF, induces antibiotic resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002103. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzem R., Stapleton H., Gunsch C. K. (2014). Determining the ecological impacts of organic contaminants in biosolids using a high-throughput colorimetric denitrification assay: a case study with antimicrobial agents. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 1646–1655 10.1021/es404431k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper D. C. (2005). Efflux pumps and nosocomial antibiotic resistance: a primer for hospital epidemiologists. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40, 1811–1817. 10.1086/430381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. R., Czechowska K., Chèvre N., van der Meer J. R. (2009). Toxicity of triclosan, penconazole and metalaxyl on Caulobacter crescentus and a freshwater microbial community as assessed by flow cytometry. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 1682–1691. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01893.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. D., Jampani H. B., Newman J. L., Lee A. S. (2000). Triclosan: a review of effectiveness and safety in health care settings. Am. J. Infect. Control 28, 184–196. 10.1067/mic.2000.102378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatzas K. A. G., Webber M. A., Jorgensen F., Woodward M. J., Piddock L. J. V., Humphrey T. J. (2007). Prolonged treatment of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium with commercial disinfectants selects for multiple antibiotic resistance, increased efflux and reduced invasiveness. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60, 947–955. 10.1093/jac/dkm314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern W. V., Oethinger M., Jellen-Ritter A., Levy S. B. (2000). Non-target gene mutations in the development of fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 814–820. 10.1128/AAC.44.4.814-820.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khachatourians G. G. (1998). Agricultural use of antibiotics and the evolution and transfer of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 159, 1129–1136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar K. S., Priya S. M., Peck A. M., Sajwan K. S. (2010). Mass loadings of triclosan and triclocarban from four wastewater treatment plants to three rivers and landfill in Savannah, Georgia, USA. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 58, 275–285. 10.1007/s00244-009-9383-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kümmerer K. (2004). Resistance in the environment. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54, 311–320. 10.1093/jac/dkh325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau E., Young S. (2014). Minnesota issues ban on antibacterial ingredient. CNN (online) Available at: http://www.cnn.com/2014/05/21/health/triclosan-ban-antibacterial/

- LaPara T. M., Burch T. R., McNamara P. J., Tan D. T., Yan M., Eichmiller J. J. (2011). Tertiary-treated municipal wastewater is a significant point source of antibiotic resistance genes into Duluth-Superior Harbor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 9543–9549. 10.1021/es202775r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S. B. (2002). Active efflux, a common mechanism for biocide and antibiotic resistance. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92, 65S–71S. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.92.5s1.4.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S. B., Marshall B. (2004). Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nat. Med. 10, S122–S129. 10.1038/nm1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Pop M. (2009). ARDB—Antibiotic Resistance Genes Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D443–D447. 10.1093/nar/gkn656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano N., Rice C. P., Ramirez M., Torrents A. (2013). Fate of Triclocarban, Triclosan and Methyltriclosan during wastewater and biosolids treatment processes. Water Res. 47, 4519–4527. 10.1016/j.watres.2013.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubarsky H. V., Gerbersdorf S. U., Hubas C., Behrens S., Ricciardi F., Paterson D. M. (2012). Impairment of the bacterial biofilm stability by triclosan. PLoS ONE 7:e31183. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Wilson C., Novak J. T., Riffat R., Aynur S., Murthy S., et al. (2011). Effect of various sludge digestion conditions on sulfonamide, macrolide, and tetracycline resistance genes and class I integrons. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 7855–7861. 10.1021/es200827t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massengo-Tiassé R. P., Cronan J. E. (2008). Vibrio cholerae FabV defines a new class of enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1308–1316. 10.1074/jbc.M708171200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massengo-Tiassé R. P., Cronan J. E. (2009). Diversity in enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 1507–1517. 10.1007/s00018-009-8704-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavri A., Kurin M., Smole S. (2012). The prevalence of antibiotic and biocide resistance among Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni from different sources. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 50, 371–376. [Google Scholar]

- McAvoy D. C., Schatowitz B., Jacob M., Hauk A., Eckhoff W. S. (2002). Environmental Chemistry Measurement of triclosan in wastewater treatment systems. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 21, 1323–1329. 10.1002/etc.5620210701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcbain A. J., Bartolo R. G., Catrenich C. E., Charbonneau D., Ledder R. G., Price B. B., et al. (2003). Exposure of sink drain microcosms to triclosan: population dynamics and antimicrobial susceptibility. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 5433–5442. 10.1128/AEM.69.9.5433-5442.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan K., Halden R. U. (2010). Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in archived U.S. biosolids from the 2001 EPA National Sewage Sludge Survey. Water Res. 44, 658–668. 10.1016/j.watres.2009.12.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell G., Russell D. A. (1999). Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action, and resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12, 147–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurry L. M., Mcdermott P. F., Levy S. B. (1999). Genetic evidence that InhA of Mycobacterium smegmatis is a target for triclosan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43, 711–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurry L. M., Oethinger M., Levy S. B. (1998a). Overexpression of marA, soxS, or acrAB produces resistance to triclosan in laboratory and clinical strains of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 166, 305–309. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13905.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurry L. M., Oethinger M., Levy S. B. (1998b). Triclosan targets lipid synthesis. Nature 394, 531–532. 10.1038/28970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara P. J., Krzmarzick M. J. (2013). Triclosan enriches for Dehalococcoides-like Chloroflexi in anaerobic soil at environmentally relevant concentrations. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 344, 48–52. 10.1111/1574-6968.12153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara P. J., Lapara T. M., Novak P. J. (2014). The impacts of triclosan on anaerobic community structures, function, and antimicrobial resistance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 7393–7400. 10.1021/es501388v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton J. H., Salierno J. D. (2013). Antibiotic resistance in triclosan tolerant fecal coliforms isolated from surface waters near wastewater treatment plant outflows (Morris County, NJ, USA). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 88, 79–88. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2012.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller T., Heidler J. (2008). Fate of triclosan and evidence for reductive dechlorination of triclocarban in estuarine sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 4570–4576. 10.1021/es702882g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mima T., Joshi S., Gomez-Escalada M., Schweizer H. P. (2007). Identification and characterization of TriABC-OpmH, a triclosan efflux pump of Pseudomonas aeruginosa requiring two membrane fusion proteins. J. Bacteriol. 189, 7600–7609. 10.1128/JB.00850-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munir M., Wong K., Xagoraraki I. (2010). Release of antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes in the effluent and biosolids of five wastewater utilities in Michigan. Water Res. 45, 681–693. 10.1016/j.watres.2010.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nietch C., Quinlan E. (2013). Effects of a chronic lower range of triclosan exposure on a stream mesocosm community. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 32, 2874–2887. 10.1002/etc.2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K. (2002). Mechanisms of bacterial biocide and antibiotic resistance. J. Appl. Microbiol. Symp. Suppl. 92, 55S–64S 10.1046/j.1365-2672.92.5s1.8.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proia L., Morin S., Peipoch M., Romaní A. M., Sabater S. (2011). Resistance and recovery of river biofilms receiving short pulses of Triclosan and Diuron. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 3129–3137. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruden A., Arabi M., Storteboom H. N. (2012). Correlation between upstream human activities and riverine antibiotic resistance genes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 11541–11549. 10.1021/es302657r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruden A., Pei R., Storteboom H., Carlson K. H. (2006). Antibiotic resistance genes as emerging contaminants: studies in northern Colorado. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 7445–7450. 10.1021/es060413l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pycke B. F. G., Crabbé A., Verstraete W., Leys N. (2010a). Characterization of triclosan-resistant mutants reveals multiple antimicrobial resistance mechanisms in Rhodospirillum rubrum S1H. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 3116–3123. 10.1128/AEM.02757-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pycke B. F. G., Vanermen G., Monsieurs P., De Wever H., Mergeay M., Verstraete W., et al. (2010b). Toxicogenomic response of Rhodospirillum rubrum S1H to the micropollutant triclosan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 3503–3513. 10.1128/AEM.01254-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pycke B. F. G., Geer L. A., Dalloul M., Abulafia O., Jenck A. M., Halden R. U. (2014). Human fetal exposure to triclosan and triclocarban in an urban population from Brooklyn, New York. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 8831–8838. 10.1021/es501100w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensch U., Klein G., Kehrenberg C. (2013). Analysis of triclosan-selected Salmonella enterica mutants of eight serovars revealed increased aminoglycoside susceptibility and reduced growth rates. PLoS ONE 8:e78310. 10.1371/journal.pone.0078310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell A. D. (2000). Do biocides select for antibiotic resistance? J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 52, 227–233 10.1211/0022357001773742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh S., Haddadin R. N. S., Baillie S., Collier P. J. (2011). Triclosan—an update. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 52, 87–95. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02976.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez P., Moreno E., Martinez J. L. (2005). The biocide triclosan selects Stenotrophomonas maltophilia mutants that overproduce the SmeDEF multidrug efflux pump. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 781–783. 10.1128/AAC.49.2.781-782.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer H. P. (2001). Triclosan: a widely used biocide and its link to antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 202, 1–7. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10772.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan A., Lenahan M., Condell O., Bonilla-Santiago R., Sergeant K., Renaut J., et al. (2013). Proteomic and phenotypic analysis of triclosan tolerant verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli O157:H19. J. Proteom. 80, 78–90. 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer H., Müller S., Tixier C., Pillonel L. (2002). Triclosan: occurrence and fate of a widely used biocide in the aquatic environment: field measurements in wastewater treatment plants, surface waters, and lake sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 4998–5004. 10.1021/es025750i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovgaard S., Nielsen L. N., Larsen M. H., Skov R. L., Ingmer H., Westh H. (2013). Staphylococcus epidermidis isolated in 1965 are more susceptible to triclosan than current isolates. PLoS ONE 8: e62197. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater-Radosti C., Aller G. V., Greenwood R., Nicholas R., Keller P. M., DeWolf W. E. Jr., et al. (2001). Biochemical and genetic characterization of the action of triclosan on Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48, 1–6. 10.1093/jac/48.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son A., Kennedy I. M., Scow K. M., Hristova K. R. (2010). Quantitative gene monitoring of microbial tetracycline resistance using magnetic luminescent nanoparticles. J. Environ. Monit. 12, 1362–1367. 10.1039/c001974g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasinakis A. S., Mamais D., Thomaidis N. S., Danika E., Gatidou G., Lekkas T. D. (2008). Inhibitory effect of triclosan and nonylphenol on respiration rates and ammonia removal in activated sludge systems. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 70, 199–206. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2007.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suller M. T. E., Russell A. D. (2000). Triclosan and antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 46, 11–18. 10.1093/jac/46.1.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkachenko O., Shepard J., Aris V. M., Joy A., Bello A., Londono I., et al. (2007). A triclosan-ciprofloxacin cross-resistant mutant strain of Staphylococcus aureus displays an alteration in the expression of several cell membrane structural and functional genes. Res. Microbiol. 158, 651–658. 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). (2009). Targeted National Sewage Sludge Survey Statistical Analysis Report. Report EPA-822-R-08-018. Washington, DC: USEPA. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan A. K., Halden R. U. (2014). Wastewater treatment plants as chemical observatories to forecast ecological and human health risks of manmade chemicals. Sci. Rep. 4, 1–11. 10.1038/srep03731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viau E., Bibby K., Paez-Rubio T., Peccia J. (2011). Toward a consensus view on the infectious risks associated with land application of sewage sludge. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 5459–5469. 10.1021/es200566f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalaín J., Mateo C. R., Aranda F. J., Shapiro S., Micol V. (2001). Membranotropic effects of the antibacterial agent Triclosan. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 390, 128–136. 10.1006/abbi.2001.2356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber M. A., Randall L. P., Cooles S., Woodward M. J., Piddock L. J. V. (2008). Triclosan resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62, 83–91. 10.1093/jac/dkn137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsch T., Gillock E. (2011). Triclosan-resistant bacteria isolated from feedlot and residential soils. J. Environ. Sci. Health A Tox. Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 46, 436–440. 10.1080/10934529.2011.549407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2014). Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance. Geneva: WHO; Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112642/1/9789241564748_eng.pdf?ua=1 [accessed September 15, 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- Xia K., Hundal L. S., Kumar K., Armbrust K., Cox A. E., Granato T. C. (2010). Triclocarban, triclosan, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and 4-nonylphenol in biosolids and in soil receiving 33-year biosolids application. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 29, 597–605. 10.1002/etc.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Li B., Zou S., Fang H. H. P., Zhang T. (2014). Fate of antibiotic resistance genes in sewage treatment plant revealed by metagenomic approach. Water Res. 62C, 97–106 10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdankhah S. P., Scheie A. A., Høiby E. A., Lunestad B.-T., Heir E., Fotland T. Ø., et al. (2006). Triclosan and antimicrobial resistance in bacteria: an overview. Microb. Drug Resist. 12, 83–90. 10.1089/mdr.2006.12.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying G.-G., Yu X.-Y., Kookana R. S. (2007). Biological degradation of triclocarban and triclosan in a soil under aerobic and anaerobic conditions and comparison with environmental fate modelling. Environ. Pollut. 150, 300–305. 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B. J., Kim J. A., Ju H. M., Choi S.-K., Hwang S. J., Park S., et al. (2012). Genome-wide enrichment screening reveals multiple targets and resistance genes for triclosan in Escherichia coli. J. Microbiol. 50, 785–791. 10.1007/s12275-012-2439-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B. J., Kim J. A., Pan J.-G. (2010). Signature gene expression profile of triclosan-resistant Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65, 1171–1177. 10.1093/jac/dkq114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Zhang X.-X., Ye L. (2011). Plasmid metagenome reveals high levels of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements in activated sludge. PLoS ONE 6:e26041. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Lin J., Ma J., Cronan J. E., Wang H. (2010). Triclosan resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 is due to FabV, a triclosan-resistant enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 689–698. 10.1128/AAC.01152-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]