Abstract

The Washington State Achiever (WSA) program was a large-scale educational intervention of scholarships, mentoring, and school redesign designed to encourage students from moderate and low income families to attend college in Washington State. Using a quasi-experimental design based on pre- and post-intervention surveys of high school seniors in program and non-program schools, we find a significant WSA effect on educational outcomes, net of the demographic and socioeconomic composition of students across schools. Across the three intervention high schools, the program is strongly significant in one school, significant after a lag in another school, and not significant in a third. We speculate about the potential reasons for the differential program effect across high schools.

INTRODUCTION

Educational attainment, and a college degree in particular, is the surest path for socioeconomic advancement in American society. In 2007, the median earnings for a college graduate ($47,000) was 74% higher than that of a high school graduate ($27,000), while median earnings for a worker with an advanced degree ($60,000) was 31% higher than that of a worker with a bachelor’s degree (Crissey 2009, also see Cheeseman and Newburger 2002). However, the doors to higher education are not equally open to all. Students from poorer families and those with less educated parents are less likely to finish high school and enter college (Kauffman, Alt and Chapman 2004, Rumberger 1987). The gap in high school completion between black and white students has narrowed in recent years, but black students are still less likely to attend and graduate from college (Aud et al. 2011, Snyder et al. 2004). Latino and American Indian students are disadvantaged at all levels of schooling (Aud et al. 2011, Freeman and Fox 2005).

Breaking the association between ascribed characteristics and educational attainment has been a national priority since the days of the Great Society and the War on Poverty in the 1960s. Head Start, Title I programs, and a host of other federal, state, and local efforts aimed to strengthen the quality of K-12 public education for children from disadvantaged origins. Federal and state scholarship programs as well as subsidized loans were designed to directly assist low income students in entering college. Affirmative action programs and similar initiatives were targeted to encourage and assist students in groups that had been left behind in expansion of higher education in the post-World War II era. Although there is evidence that these programs have made a difference, there has been a policy drift on how to expand college opportunity for disadvantaged students in recent years (Fitzgerald 2004).

The assumption that direct aid to disadvantaged students and schools has not been effective or cost efficient has sparked new policies with an emphasis on market competition between public, private, and charter schools. These programs assume that school reorganization and reform will lead to improvements in the quality of secondary schooling and they will inspire and prepare disadvantaged high school students to attend college. School reform programs often stress local autonomy in order to reward innovative teachers and programs (Lee and Smith 2001, Mehan et al. 1996, National Research Council 2004).

There is considerable research, however, indicating that the costs of higher education remain a major obstacle for many students from low income families (St. John 2003, Deming and Dynarski 2009). In this study, we provide a preliminary evaluation of a major educational policy intervention designed to increase the numbers of disadvantaged students attending college—the “Washington State Achievers” (WSA) program. The WSA program, supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, addresses both the traditional concern of insufficient resources to attend college with the provision of scholarships and the new emphasis on school reform to better prepare disadvantaged students for higher education (O’Brien 2007). The WSA program operated in 16 high schools in Washington State from 2001 to 2010. In this study, we use data from the University of Washington Beyond High School Project, which includes three WSA high schools and two non-program (control) high schools, to offer an early evaluation of the impact of the program in one school. We find a strong impact of the WSA program on educational outcomes, but with considerable variation between high schools. The findings suggest that successful program interventions require not only good ideas and financial investments, but also effective implementation.

EDUCATIONAL STRATIFICATION AND POLICY INTERVENTIONS

One of the major trends of the twentieth century has been a dramatic increase in the levels of educational attainment across successive generations (Mare 1995, Fischer and Hout 2006). These gains have been recorded for all segments of the American population, but with few exceptions, there has been very little narrowing of educational stratification by class and race (Kao and Thompson 2003, Mare 1995). Although Asian students have reached educational parity with whites, other race and ethnic minorities (African American, Hispanic, and Native American) and economically disadvantaged students continue to display lower levels of success at all levels of schooling (Kao and Thompson 2003, Lareau 2003, Perriera et al. 2006, KewalRamani et al. 2007).

Massey and colleagues (2003) have recently synthesized theories of educational stratification in terms of a “capital deficiency” framework. This framework consists of four broad types of capital—financial, human, social, and cultural—that affect the likelihood that youth will succeed in school. Financial capital consists of the assets that constitute a family’s economic resources (e.g. income, wealth, property). Human capital is the sum of knowledge and skills, generally indexed by educational attainment that is rewarded in the labor market (Becker 1964). College educated parents are more likely to know the value (economic and non-economic) of a college degree and they can provide encouragement and advice to their children during the college selection, preparation, and application process (Kim and Schneider 2005, Perriera et al. 2006).

Social capital refers to the benefits and advantages accrued from participation in social networks and organizations (Bourdieu and Passeron 1977). Membership in a community with high levels of social capital allows for the reinforcement of collective norms and values, and it can play a crucial role in sponsoring the educational attainment of the community’s younger members (Kao 2004, Zhou and Bankston 1998). Cultural capital is the values and attitudes that reinforce high ambitions, hard work, perseverance, and deferred gratification (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977). The four forms of capital are independent but are often highly correlated among families. For example, middle class parents can afford to buy homes in wealthy neighborhoods, which offer access to better schools as well as better social connections, including high status neighbors and high achieving peer networks for their children (Ainsworth-Darnell 2002).

Policies and programs designed to increase educational opportunities for disadvantaged youth attempt to mitigate financial, human, social, or cultural capital deficits in isolation or in combination. The most widespread programs have addressed financial capital deficits through the provision of scholarships, grants, and loans. There are also programs designed to compensate for the lack of human, social, and cultural capital resources by using teachers, counselors, and mentors to encourage students’ educational ambitions, to improve study skills, and to provide knowledge about the college application process.

Not every study finds consistent support for financial capital interventions, but several federal programs designed to increase post-secondary access with generous financial assistance to students have been successful. For example, the GI Bill for returning veterans after World War II and the Social Security benefits for surviving dependents significantly increased levels of college enrollment and attainment (Bound and Turner 2002, Katznelson 2005, Dynarski 2003). Pell grants, which are much less generous, do not appear to have markedly increased college attendance among low-income recent high school graduates, but they have increased college enrollment among older (‘non-traditional’) students (Hansen 1983, Kane 1994, 1995, Leslie and Brinkman 1988, Seftor and Turner 2002).

In recent years, several state governments have created innovative scholarship programs to increase college attendance. There is considerable evidence that merit based programs increase overall levels of college enrollment and completion (Abraham and Clark, 2006, Cornwell et al. 2006, Dynarski, 2004, 2008, Leslie and Brinkman 1988, Kane 2007, St John et al. 2004, 2010), but it has been much more difficult to reduce race and socioeconomic differentials (Dynarski 2002, Binder et al. 2002, Cornwell and Mustard 2002). Merit based programs in Georgia and New Mexico have disproportionately benefited students from advantaged social origins (Dynarski 2002, Binder et al. 2002, Cornwell and Mustard 2002). However, the “Twenty First Century Scholars” program in Indiana, which integrates both a merit and need based component, has increased rates of college attendance among students from less advantaged social origins (St. John et al. 2003, 2004, also see Dynarski 2004).

There is widespread recognition that programs to expand educational opportunities also need to address other capital deficits of disadvantaged families, including the information gap about the college application process and the social and cultural supports necessary to increase educational ambitions and persistence. Federal and state governments often sponsor outreach programs, such as GEAR UP and Upward Bound that include academic counseling, supplemental tutoring, and college visits with the objective of increasing levels of awareness and interest in college among low income middle and high school aged students (US Department of Education 2004, 2008). There is much less research on these programs, but there is tentative evidence of a positive program impact on college attendance for low income students (ACT 2007, Domina 2009, Meyers et al. 2004).

Given the deeply rooted and multi-faceted nature of unequal access to higher education, successful interventions may need to address all of the ‘capital’ barriers faced by low income students. The Washington State Achiever Program (WSA) is a holistic program that incorporates the promise of scholarships, efforts to expand college awareness, and mentoring, as well as school restructuring.

THE WASHINGTON STATE ACHIEVERS PROGRAM

Program Overview

In 2001, the College Success Foundation, with financial support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, launched the Washington State Achievers Program (WSA) in sixteen predominantly low to modest income high schools in Washington State. The program was designed to: 1) encourage school redesign that facilitates high academic achievement and increased college enrollment among all students at the selected high schools, 2) identify and reduce financial barriers to college for motivated and talented low-income students, 3) provide mentoring and academic support to WSA scholars (program participants) once they are enrolled in college, and 4) develop a diverse cadre of college-educated citizens and leaders in Washington State (O’Brien 2007)1.

Students in the 16 WSA program schools were eligible to apply to be a WSA scholar (and receive a college scholarship for up to five years) if their family income was in the lowest one-third of the Washington State income distribution (O’Brien 2007). Less than half of all eligible (low income) students in the 16 WSA high schools submitted an application for a scholarship. After a two stage process of evaluation of applications, 500 students were selected to receive WSA college scholarships (across all 16 high schools) each year from 2001 to 2010. The scholarships were designed to cover all college expenses (tuition, room, board, books, etc.) after considering support from other sources (O’Brien 2007).

The first stage of the WSA scholar selection process was based on written materials from the applicants and teacher recommendations. In addition to academic potential, applicants were judged on their “non-cognitive skills,” as evidenced by positive self-concept, realistic self-appraisal, community service, and leadership potential (Sedlacek 2004, O’Brien 2007). The second stage of evaluation was a one day interactive workshop, at which students are again evaluated based on non-cognitive skills using an evaluation system of observer ratings developed by Deborah Bial, founder of the Posse Foundation (O’Brien 2007). Each stage of the evaluation reduced the applicant pool by about one-third. Finally, about 500 applicants were designated WSA scholars in the winter of their junior year. WSA scholars receive a college scholarship and they are paired with a ‘hometown’ mentor, whose primary task is to assist with the college selection and application process.

A Holistic Intervention Strategy

The WSA program also included a holistic model of school reform that aimed to create smaller more personalized learning communities that emphasized higher standards and expectations of all students. The program of school reform was directed at all students in the WSA schools. However, the centerpiece of the WSA program was the award of the 500 five-year college scholarships every year for a 10 year period from 2001 to 2010. While the scholarships are meant to alleviate the financial constraints that accompany college attendance, the other features of the WSA program, such as mentoring, expanding college preparation courses, and the creation of small learning communities, are available to all students in the WSA schools and are meant to compensate for the deficits of human, social, and cultural capital in low income families.

However, since the implementation of the WSA program was rolled out over several years, our assessment cannot capture the long-term impact of the various program components on students and schools. The process of school reform and the development of small learning communities were developed from local planning committees in each participating school over the course of the first four years of the program. Moreover, additional feature were added over time (e.g. a middle school early college awareness curriculum). Given the early timing of our evaluation, the results are most likely to reflect the scholarship component of the WSA program, as the school and curricular reform were not fully implemented across program schools by 2005.

The most comprehensive evaluation of the WSA program has been undertaken by St. John, Hu and colleagues (2006, 2007, 2010) who estimate the impact of a WSA scholarship on educational ambitions and college attendance. They find the scholarship recipients, relative to non-recipients, have more positive educational outcomes net of controls on individual-level demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. At the individual level, it is quite difficult to estimate the direct effect of the program (such as the scholarship) from selectivity into the program. For example, WSA scholars were motivated to apply to the program and were then selected as the most promising candidates. The characteristics of successful WSA scholars are almost certainly predictive of college ambition and achievement even in the absence of the WSA program.

In this study, we examine the effect of the presence of the WSA program on the likelihood of students attending college. In the language of program evaluation research, our research measures the impact of the “intent to treat” not the effect of the “treatment on the treated.” The latter approach conflates the impact of the program with the selection of students in the program (receiving a scholarship). With micro level data, individual students are the units of observation, but we consider the school as the unit of evaluation of the program effect. Our analytical focus is the comparison of the change in the rate of college going (before and after implementation) in WSA schools relative to the temporal change in nonWSA schools, controlling for between school differences in student composition.

THE UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON BEYOND HIGH SCHOOL PROJECT

The analysis reported here is based on survey data from a study of the transition from high school to college—the University of Washington Beyond High School Project (UW-BHS). The UW-BHS includes five cohorts of high school seniors in several West Coast metropolitan school districts in 2000 and from 2002 to 2005. The first baseline survey of high school seniors was conducted in 2000 before the WSA program began, and there were four additional baseline senior surveys conducted post program implementation (2002 to 2005). In addition to the baseline surveys of high school seniors, there was a one-year follow-up survey to measure college attendance one year after high school graduation.

The analysis presented here is based on a merged data set of over 5,000 students from these five cohorts of high school seniors in one large urban public school district. This school district is one of the largest in the state with more than 25,000 students enrolled in K-12 grades. The major differences among the 5 high schools are in the socioeconomic composition of students. Three high schools are more “working class,” with somewhat higher proportions of low income and minority students relative to the two “middle class” high schools (student composition is described more fully below in Table 1). Although the UW-BHS project was organized without any prior knowledge of the WSA program, the selection of 3 high schools with the program and 2 high schools without the program yielded a quasi-experimental research design.

Table 1.

Percent Distribution of Educational Outcomes and Social and Economic Characteristics of High School Seniors in 2000 (Pre Program) and 2002 to 2005 (Post Program).

| Educational Outcomes | Pre-Program | Post Program | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 2000 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | |

| COLLEGE PLANS: | |||||

| Four Year College Plans for Year Post-HS | 35.8 | 37.8 | 39.2 | 45.0 | 41.7 |

|

| |||||

| COLLEGE PREPARATION: | |||||

| Taken SAT/ACT by spring of senior year | 54.7 | 56.1 | 56.7 | 60.4 | 61.7 |

|

| |||||

| COLLEGE ATTENDANCE: | |||||

| Attended a 4-Year Degree College | 31.3 | 31.9 | 31.6 | 35.3 | 34.3 |

| Attended a 4 or 2-Year Degree College | 65.8 | 67.6 | 65.7 | 67.8 | 65.4 |

|

| |||||

| Social and Economic Characteristics | |||||

| GENDER: | |||||

| Male | 46.1 | 45.5 | 45.5 | 46.0 | 42.5 |

| Female | 53.9 | 54.5 | 54.5 | 54.0 | 57.5 |

|

| |||||

| RACE/ETHNICITY:a | |||||

| Hispanic | 7.6 | 9.7 | 10.4 | 7.7 | 6.5 |

| African American | 17.8 | 17.3 | 16.7 | 15.1 | 19.0 |

| East Asian | 5.0 | 6.8 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 6.5 |

| Cambodian | 4.7 | 3.6 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| Vietnamese | 4.7 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 3.3 |

| Filipino | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 1.5 |

| Other Asian | 2.2 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| American Indian | 3.1 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 3.9 | 4.3 |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.6 |

| White and others NEC | 50.6 | 50.4 | 54.3 | 55.9 | 52.6 |

|

| |||||

| PARENTAL EDUCATION: | |||||

| Neither with college | 29.8 | 27.9 | 27.7 | 27.8 | 28.8 |

| One or both with some college | 37.7 | 40.0 | 39.5 | 41.3 | 39.4 |

| One or both college graduate | 32.5 | 32.1 | 32.8 | 30.9 | 31.8 |

|

| |||||

| HOME OWNERSHIP | |||||

| Rents | 33.9 | 33.3 | 30.4 | 31.9 | 30.5 |

| Owns home | 66.1 | 66.7 | 69.7 | 68.1 | 69.5 |

|

| |||||

| FAMILY STRUCTURE:b | |||||

| Lives with both birth/adoptive parents | 55.3 | 56.2 | 56.0 | 54.6 | 53.8 |

| Disrupted family, has father & mother figures | 31.7 | 34.4 | 35.4 | 36.5 | 36.8 |

| Missing a father figure or mother figure | 13.1 | 9.5 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 9.5 |

|

| |||||

| GENERATIONAL STATUS: | |||||

| First (foreign born) | 15.4 | 16.6 | 14.3 | 12.7 | 10.8 |

| Second (child of immigrants) | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.3 | 13.8 | 17.8 |

| Third or higher (or unknown) | 69.0 | 67.8 | 70.5 | 73.5 | 71.4 |

|

| |||||

| High School Attended: | |||||

| High School #1 (WSA program present) | 20.7 | 23.1 | 19.0 | 18.5 | 19.4 |

| High School #2 (WSA program present) | 15.7 | 16.5 | 14.4 | 16.1 | 16.9 |

| High School #3 (WSA program present) | 14.8 | 12.9 | 14.9 | 13.3 | 16.1 |

| High School #4 (Non-program school) | 24.8 | 23.2 | 25.5 | 21.6 | 23.8 |

| High School #5 (Non-program school) | 24.0 | 24.3 | 26.2 | 30.5 | 23.7 |

|

| |||||

| N of high school seniors on official roster | 1,450 | 1,559 | 1,617 | 1,450 | 1,565 |

| N of high school seniors surveyed | 1,140 | 1,173 | 1,219 | 1,020 | 1,066 |

| Senior Survey response rate | 78.6% | 75.2% | 75.4% | 70.3% | 68.1% |

| N of follow up respondents | 1,005 | 1,046 | 1,102 | 916 | 1,004 |

| Follow up response rate | 88.2% | 89.2% | 90.4% | 89.8% | 94.2% |

Notes:

Race/Ethnicity is constructed from two variables (Q158 and Q159). About 10 percent of students reported 2 or more races and about 5 percent did not report any race or ethnicity. No responses were coded according to the race/ethnicity listed in school records, and multiple race respondents were coded

Family structure is based on Q186, which asks if the respondent lives with both your mother and your father (biological or adoptive). The second category includes respondents who answered “no” to Q186 (not living with both mother and father), but did report a mother and father figure (Q123 and Q131). The third category includes respondents not living with both mother and father (Q186) and report not having a father figure or mother figure (Q123 and Q131).

The target sample for the UW-BHS survey was all enrolled seniors in April or May in the selected high schools. In spite of our best efforts to interview all seniors in the school district; we estimate that roughly a quarter all of high school seniors were missed in the baseline survey. The problem of under-coverage was acute for students enrolled in alternative programs for students with academic, behavioral, or disciplinary problems and for students with high rates of absenteeism. For seniors who attended the five major comprehensive high schools and attended school on a regular basis, the coverage rate was close to 80%. A one-year follow-up survey to measure college attendance in the following year was also conducted; 92% of baseline survey respondents completed the follow-up. This leaves an effective sample of 5,618 seniors and 5,073 students who completed both the senior survey and the one-year follow-up survey.

Generally, the level of student non-response to survey questions was very low. In the instances that data were missing we used random single imputation regression methods. This method, under the assumption that the data are missing at random, samples from the error distributions to maintain the natural variance of each variable and provides a predicted value for the missing data points (Allison 2002).

MEASUREMENT

The dependent variables are educational outcomes that were central WSA program objectives: 1) planning to attend 4-year college, 2) taking a college entrance exam (i.e. SAT, ACT), 3) enrollment in any college (2 or 4 year), and 4) enrollment at a 4 year college These measures, which tap subjective and behavioral aspects of the transition from high school to college, are shown in Table 1 for the entire sample of high school seniors at the five comprehensive high schools in the pre-program year of 2000 and in the post-program years of 2002 to 2005. This descriptive table also presents the distributions of the demographic, socioeconomic, and other background variables of students in the UW-BHS sample of high school seniors. Although these background variables are not the primary focus of attention in this analysis of the impact of a policy intervention, the socioeconomic and demographic composition of students shapes the context of this study, and are also used as “controls” to estimate the net effect of the WSA intervention.

The dependent variables include one subjective measure of educational ambitions and three behavioral measures of college preparation and enrollment. The indicator of college plans, the subjective measure, is based upon the students’ responses to “Do you plan to go on to college or other additional schooling right after high school? That is, do you plan to continue your education THIS FALL?” For students who report college plans, a follow-up question asked: “What is the name and location of the college, professional, or technical school that you will most likely attend in the fall? The students list, in preferential order, three schools which they plan to attend. The ‘college plans’ indicator used in our analysis is captured by examining whether the students’ first choice college is a four year college or not1. Roughly four-fifths of students reported some post-secondary college plan, but only about two-fifths of surveyed students reported that the institution which they planned to attend post-high school is a four year college or university.

Student preparation for college is indexed by measuring whether a student had taken a college-board examinations; either the SAT (Scholastic Assessment Test) or the ACT (American College Test). This variable is coded as a dichotomy with yes meaning that the student had taken the SAT or ACT. Although the SAT/ACT is required for application to most four-year colleges, there is not a requirement for admission to community colleges, which enroll more post-secondary students than four year colleges and universities.

In 2000, a little more than half of students have taken the SAT or ACT—almost 55%. This figure rose by a point or so in 2002 and 2003, but then jumped to 62% in 2004. Small variations from year to year may be due to random variation or because of slight variations in the completeness of coverage (and perhaps some differences in selectivity of response) of the annual surveys, but the similarity of the trends suggests that there has been a modest increase in college ambitions and in college preparation in 2004 and 2005 relative to prior years.

We consider two measures of college enrollment: attendance at either a two-year or four-year college2 and attendance only at a four-year college3. The figures reported here are for the sub-sample of respondents interviewed in the follow-up survey (see Ns at the bottom of each column). The results show that the proportion of seniors going on to college (of any type) rose slightly from 65% to 68% over the period, and from 31% to 34% enrolled in four year institutions.

In contrast to the trend of rising (albeit modest) educational outcomes reported in Table 1, the variables measuring the demographic and socioeconomic composition of students show a very stable portrait of students in a West Coast metropolitan school district. There are fluctuations from year to year, but with one or two exceptions, there is little evidence of major changes in student composition (or in the composition of respondents to the UW-BHS questionnaire) over the years. The stability of student characteristics over time suggests the increasing levels of student educational achievement are not an artifact of changes in student composition.

A little more than half of the sample of seniors is female (males are somewhat more likely to be high school dropouts). In the first two years of the UW-BHS surveys, about half of seniors were white (a bit more in later years) and the balance was composed students from various racial and ethnic categories—about 15–17 percent black, 7–10 percent Hispanic, with small fractions of East Asians (Chinese, Japanese, Koreans), Vietnamese, Cambodians, Filipinos, American Indians, and Pacific Islanders.

Family background is measured by parental education, home ownership, and family structure. Parental education, an indicator of familial socio-economic status, is summarized with the highest education of either parent (absent parents were included only to the extent that the student could report on their educational attainment). Home ownership (rent versus own) is another measure of socioeconomic status or net wealth. Family structure is represented with three categories: 1) Co-residence with birth/adoptive parents, 2) Disrupted family (by divorce or death), but the student reports having both a father and mother figure in their lives4, and 3) Student reports not living with both parents and not having a father figure and/or mother figure. Generational status measures nativity as: foreign born students, the second generation (children of immigrants), and everyone else (third and higher generations).

The modal “highest educated parent” is a mother or father (or mother-figure or father-figure) with some college—about 37 to 41 percent of students were in this category. A little more than one quarter of students have parents whose highest educational experience was high school graduation or less, while almost one-third of students report that at least one parent was a college graduate. The other measure of socioeconomic status—homeownership—shows about one-third of students live in rental housing. In general, families that live in rental housing are poorer (both in wealth and income) than families that own their homes.

Somewhat more than half of the seniors in our sample, about 55%, are living with both of their birth (or adoptive) parents. At the other end of the spectrum, about 10% of the students report that they do not have either a mother and/or father figure in their lives. In between, constituting about one-third of the sample of students, are students who have experienced some fissure of their natal family, but have parenting relationships with step-parents, non-resident parents, or other relatives. Roughly 12 to 14 percent of students were born outside the United States and another 14 to 17 percent are the children of immigrants. The balance are 3rd and higher generation American residents (or students for whom nativity status is unknown).

Table 1 also lists the five high schools analyzed in this study (identified as schools 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5.) Schools 1 through 3 are the WSA high schools and schools 4 and 5 are the nonWSA schools. The two nonWSA high schools are somewhat larger and enroll about ½ of the the UW-BHS sample, while the three smaller WSA schools enrolled the other half of the seniors in the district. There are fluctuations in the relative size of schools from year to year without a systematic trend. The relative stability in the overall demographic and socioeconomic composition of students across years indicates that temporal shifts are unlikely to be explained by differential coverage of students in the annual senior surveys.

GENERAL ANALYTIC STRATEGY

To address the effect of the WSA program’s restructuring of schools and direct scholarship program on educational outcomes, we utilize a treatment-comparison research design (e.g. Dynarski 2002, 2003, 2008, Mustard and Cornwell, 2002, Turner and Bound, 2002). The UW-BHS data allow us compare one cohort of seniors prior to program implementation (seniors in 2000) with four cohorts (seniors in 2002, 2003, 2004, and 2005) following program implementation. The data also allow for the comparison of treatment (WSA program) schools with control (nonWSA) schools. As noted above, the dependent variables represent key program objectives: college plans, preparation, and enrollment.

The major difference between a classical experimental design and quasi-experimental treatment-comparison design is that the WSA program (scholarships and school reform) was not assigned randomly to students and schools. Indeed the program was designed for low income schools and for students below an income threshold in each school. For this reason, we estimate the program effect after adjusting for socioeconomic status, family structure, race and ethnicity, and other measures of family background that may have affected inclusion in a WSA school and selection as a WSA scholar. We consider these factors to be exogenous to the WSA program. We have not included current behavioral and social psychological orientations (measured in the spring of the senior year) as control variables, because these might well be endogenous to selection of students as WSA scholars.

Our strategy is to use Year 2000 (pre-program) as indicative of the initial differences in the rates of educational outcomes across the schools. We expect, given the school selection criteria, that WSA schools will have lower initial educational values on the four educational outcomes compared to the nonWSA program schools in year 2000, and the lower levels of achievement in the WSA schools will only be partially attenuated with controls for differences in the composition of the student body. We pool the data from all schools (WSA and nonWSA) for all five years, and then estimate the temporal trend (year to year changes) in the educational outcomes. Program effects are estimated by WSA program school by year interactions, net of control variables. If the pre-intervention gap in educational achievement between WSA and nonWSA schools is narrowed following the program intervention, then we conclude the program is having an impact net of the differences in student composition.

Since there are normal temporal variations, program effects could be confounded with other secular changes and random fluctuations. By including covariates for each year and school, our models “control” for disturbances that are linked to a specific time or school context. Moreover, our focus is on substantively large and statistically significant changes in the outcome variables.

The baseline model, before considering program effects, includes dummy variables for each school and year. Since program implementation varied between schools, we consider each school as a different treatment. This is a simple additive model that estimates the observed differences between each of the three WSA schools relative to the nonWSA schools, and for each year.

| (1) |

In equation (1), Y is the predicted educational outcome (e.g. college plans, ACT/SAT taking, and college attendance), the intercept β0 represents the pooled mean outcome for non-program schools in Year 2000; β1, β2, and β3 are the pooled constant differences between non-program and the specific WSA high schools; and β4, β5 β6, and β7 represent the additive effects of each year relative to 2000. This equation captures the pooled difference between the WSA and nonWSA schools and the secular trend. Because the program schools were not selected randomly, it is necessary to add student background variables as covariates to measure the effect of the WSA program. This model is represented in equation 2.

| (2) |

In Model 2, Xn represents a broad range of background variables that differ by student and are highly correlated with educational outcomes (i.e. race/ethnicity, socioeconomic origins, and family structure); these characteristics may also differ between schools. Thus, the model provides estimates of school (and temporal) effects net of the demographic and socioeconomic composition of students in the senior class at each school. Measuring the observed effects of schools (model 1) and the effects of schools net of composition (model 2) is a necessary prelude to the estimation of program effects. Prior to the WSA intervention, schools with more disadvantaged students would be less likely to send students to college. But these same schools were targeted for the WSA program, which is designed to raise college awareness, preparation, and attendance among students. To provide a clear estimate of the program effect, we set the stage by measuring “normal” school differences (without the program) and by estimating how much of these differences are due to student composition.

The next equation specifically captures the school specific WSA program effect by adding interactions between the WSA designated schools and the presence of WSA in the years 2002, 2003, 2004, and 2005.

| (3) |

In this equation βk represents each WSA school by the expected program effects for each of the WSA and nonWSA program schools for years 2002 to 2005, respectively, relative to the baseline year of 2000. We expect the βk coefficients (12 coefficients total) to have positive signs suggesting positive outcomes for the presence of the program, perhaps increasing over time as the program matures and becomes more effective. Although there were scholarships and mentoring in all the years, the WSA program of school reform began only in the 2003–04 year, when the members of the Class of 2004 were seniors. Seeing these positive coefficients for the interaction terms is indicative of a reduction in the differences initially observed between the WSA schools and nonWSA schools and can be seen as effects due to the WSA initiative in these schools.

We do not include a measure of whether a student received a WSA scholarship as an indicator of program effect (St. John et al. 2006, 2007, 2010). As discussed above, receiving a WSA scholarship is an outcome of the WSA program and is certain to be correlated with a number of other endogenous factors, including the motivation to apply for the scholarship and the non-cognitive skills that were used to select recipients among the applicants. Since these unmeasured factors are likely to be predictive of motivations for college, many of the WSA scholars may have found some other means to attend college even if the program had not existed. The counterfactual of the WSA program is not students who did not receive a scholarship, but the absence of the program (measured by the Year 2000 data).

EFFECT OF WSA PROGRAM ON COLLEGE PLANS, PREPARATION & ENROLLMENT DESCRIPTIVE PATTERNS

Table 2 shows the temporal shift in educational outcomes for the four dependent variables—plans to attend a four year college, took the SAT/ACT, attended any college, and attended a four year college—for the five cohorts of seniors in WSA and nonWSA schools from 2000 to 2005. In the first panel of Table 2, the values of the three WSA schools are shown individually (labeled as schools 1, 2, and 3) and the two nonWSA schools (schools 4 and 5) are grouped together to represent “control” schools without an educational intervention. There are modest differences in student composition between the two nonWSA schools, but not in any of the key outcome variables in 2000.

Table 2.

Distribution of College Plans Preparation, and Attendance in WSA & Non-WSA schools: 2000, 2002, 2003, 2004, and 2005.

| Percent distribution by year for WSA and Non-WSA schools | Percent point difference between WSA schools by year and non-WSA schools in 2000d | 2000 to 2005 change in % differencee | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Educational Outcomes | 2000f | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2000 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Four Year College Plansa: | |||||||||||

| High School #1c | 38.0 | 44.8 | 46.7 | 54.9 | 54.7 | −2.4% | 4.4% | 6.3% | 14.5% | 14.3% | 16.7% |

| High School #2 | 33.0† | 30.2 | 40.7 | 36.6 | 25.3 | −7.5% | −10.3% | 0.3% | −3.8% | −15.2% | −7.7% |

| High School #3 | 20.2 * | 24.0 | 19.2 | 41.0 | 33.7 | −20.2% | −16.4% | −21.2% | 0.6% | −6.7% | 13.5% |

| High School #4 and 5 | 40.4 | 40.7 | 41.6 | 44.9 | 44.9 | -- | (0.3%) | (1.2%) | (4.5%) | (4.5%) | (4.5%) |

|

| |||||||||||

| College Preparationb: | |||||||||||

| High School #1 | 53.5 * | 61.2 | 64.0 | 70.2 | 72.2 | −9.5% | −1.8% | 1.0% | 7.3% | 9.3% | 18.7% |

| High School #2 | 48.6 *** | 48.0 | 54.3 | 49.3 | 54.1 | −14.3% | −14.9% | −8.7% | −13.6% | −8.9% | 5.5% |

| High School #3 | 35.5 *** | 41.1 | 38.6 | 56.8 | 50.6 | −27.4% | −21.8% | −24.3% | −6.1% | −12.3% | 15.1% |

| High School #4 and 5 | 62.9 | 60.4 | 59.8 | 61.2 | 63.9 | -- | −(2.5%) | −(3.1%) | −(1.7%) | (0.9%) | (0.9%) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Attended Any College: | |||||||||||

| High School #1 | 71.1 | 69.7 | 73.8 | 77.9 | 80.4 | 0.7% | −0.7% | 3.4% | 7.5% | 10.0% | 9.3% |

| High School #2 | 62.7† | 58.9 | 55.5 | 52.6 | 49.7 | −7.7% | −11.5% | −14.9% | −17.8% | −20.7% | −13.0% |

| High School #3 | 45.9 *** | 54.5 | 52.7 | 64.3 | 49.1 | −24.5% | −15.9% | −17.7% | −6.1% | −21.3% | 3.2% |

| High School #4 and 5 | 70.4 | 73.0 | 69.2 | 69.3 | 70.5 | -- | (2.6%) | −(1.2%) | −(1.1%) | (0.1%) | (0.1%) |

|

| |||||||||||

| Attended Four Year College: | |||||||||||

| High School #1 | 32.3 | 38.2 | 41.9 | 49.4 | 46.4 | −3.9% | 2.0% | 5.7% | 13.2% | 10.2% | 14.1% |

| High School #2 | 27.2 * | 25.0 | 29.0 | 26.3 | 20.1 | −9.0% | −11.2% | −7.2% | −9.9% | −16.1% | −7.1% |

| High School #3 | 17.8 *** | 17.9 | 14.6 | 32.6 | 27.6 | −18.4% | −18.3% | −21.7% | −3.6% | −8.6% | 9.8% |

| High School #4 and 5 | 36.2 | 35.0 | 33.4 | 33.4 | 36.6 | -- | −(1.2%) | −(2.8%) | −(2.8%) | (0.4%) | (0.4%) |

Note:

Four year college plans is measured by whether the student listed a four year college as the first school choice which they planned to attended the following year.

College preparation is measured by whether the student has taken the SAT or ACT college placement exam by spring of their senior year.

High schools #1, #2, and #3 are part of the WSA program. High schools #4 and #5 are not part of the WSA program

In comparing the WSA and non-WSA schools there are two potential referent categories: non-WSA schools in 2000 or non-WSA schools in each year. The use of either referent category yields nearly identical results. Thus, we use non-WSA schools in 2000 as a referent as it allows for continuity with the rest of our analysis.

The difference between WSA schools and non-WSA schools between 2000 and 2005.

Indicated levels of significance are for the logistic regression models of each outcome regressed on the three WSA school dummy variables using non-WSA schools as the referent category.

Significant at the .10 level with a two tailed test

Significant at the .05 level with a two tailed test

Significant at the .01 level with a two tailed test

Significant at the .001 level with a two tailed test

The middle panel shows the absolute differences (in percentage points) in educational outcomes for each WSA school relative to the nonWSA schools in 2000—the benchmark to judge both temporal and school effects in the subsequent multivariate analysis. The last panel shows the summary change (in percentage points) from 2000 to 2005 for each WSA school.

With only one exception, educational outcomes (college plans, test taking, and college attendance) were lower in the 3 program schools relative to the nonWSA (control) schools in 2000, prior to the initiation of the WSA program. This is not surprising since low income schools were selected for inclusion in the WSA program. For the more “middle class” nonWSA high schools, about 40% of seniors in 2000 reported that they were planning to attend a 4 year college and many more (62%) were preparing for college by taking the SAT or ACT. The plans reported by high school seniors were predictive of actual behavior one year later. More than one third (36%) of students from nonWSA schools were enrolled in a four year college one year later and twice this number (70%) were enrolled in some type of college (2 year or 4 year). In 2000, students at one of the WSA high schools (#1) had educational plans and enrollment levels that were only slightly below those of the nonWSA schools. Seniors at the other two nonWSA schools, especially #3, were much less likely to plan or prepare for college and were also much less likely to attend college. As indicated in Table 2 (Column 1) these differences compared to the nonWSA schools—based on a logistic regression of outcomes on the 3 dummy variables representing the separate WSA schools—were typically significant for WSA High Schools #2 and #3 while for High School #1 only the college preparation outcome (taking the SAT or ACT) was significant.

In the subsequent years, there is a moderate amount of “noise” as the annual percentages bounce around within a small margin of error with no clear direction, as well as some systematic patterns. For the nonWSA high schools, most of the variations do not have a consistent trend. In contrast, two of the three WSA schools registered systematic and significant gains in college planning, preparation, and attendance, while one WSA high school had a mixed record.

The most successful WSA high school (#1), which was only slightly, but significantly, below the nonWSA schools in 2000, caught up with and then surpassed the nonWSA schools. Students from high school #1 have much higher rates of college planning, preparation, and attendance than their peers in the nonWSA schools. These differences in 2005 are all significant. The poorest performing WSA high school (#3) in 2000 increased its levels of college planning, preparation and attendance from 2002 to 2004, but then slipped a bit in 2005. Although school #3 had not caught up with the nonWSA high schools, it has reached parity with (or surpassed) school #2. Since numbers can bounce around from year to year for a variety of reasons, we do not interpret single year changes (such as the decline in college outcomes of seniors in school #3 from 2004 to 2005), but look for underlying trends and patterns. In contrast to the progress of schools #1 and #3, WSA high school #2 made relatively few gains from 2002 to 2005. There were gains in college preparation for school #2, but no sustained change in college attendance.

These descriptive results offer prima facie evidence that the WSA program has had the intended effect of improving college ambitions, preparation, and performance of students in the program schools—at least for schools #1 and #3. These figures are, however, preliminary because these patterns are confounded with the characteristics of students. In the subsequent multivariate analysis, we examine school effects net of composition of students.

MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS

Based on the analytic strategy described above, Tables 3 and 4 present the results of our analysis of the impact of the WSA program on the transition to college. Table 3 includes the two dependent variables that were measured in high school—whether the student has four year college plans and whether the student has taken the SAT or ACT. Table 4 presents the results of similar models for college attendance (any college and for a 4-year college, respectively). There are three models for each dependent variable in Tables 3 and 4 that correspond to the three equations outlined in the General Analytic Strategy. Note, however, that as our focus is on the WSA program effect, we do not present the effects of the “control” variables in the tables.

Table 3.

Coefficients from Logistic Regression of WSA Program and Socioeconomic Background on Four Year College Plans and College Preparation of High School Seniors with robust standard errors

| Four year College Plans | Took SAT/ACT | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| β | Std Error | β | Std Error | β | Std Error | β | Std Error | β | Std Error | β | Std Error | |

| 2002 | .07 | .09 | .05 | .09 | −.02 | .13 | .04 | .09 | .02 | .09 | −.14 | .13 |

| 2003 | .14† | .09 | .13 | .09 | .04 | .12 | .08 | .08 | .06 | .09 | −.15 | .13 |

| 2004 | .39 *** | .09 | .42 *** | .09 | .21† | .13 | .23 ** | .09 | .26 ** | .09 | −.06 | .13 |

| 2005 | .27 ** | .09 | .24 * | .09 | .15 | .13 | .31 *** | .09 | .29 ** | .09 | .00 | .13 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| High School #1 | .21 ** | .07 | .26 *** | .08 | −.08 | .16 | .09 | .07 | .17 * | .08 | −.37 * | .16 |

| HS #1 2002 (HS #1 x 2002) | .31 | .23 | .48 * | .23 | ||||||||

| HS #1 2003 (HS #1 x 2003) | .35 | .23 | .64 ** | .23 | ||||||||

| HS #1 2004 (HS #1 x 2004) | .57 * | .24 | .88 *** | .25 | ||||||||

| HS #1 2005 (HS #1 x 2005) | .52 * | .24 | .83 *** | .25 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| High School #2 | −.40 *** | .08 | −.13 | .09 | −.03 | .19 | −.44 *** | .08 | −.13 | .09 | −.27 | .18 |

| HS #2 2002 (HS #2 x 2002) | −.12 | .27 | .12 | .26 | ||||||||

| HS #2 2003 (HS #2 x 2003) | .20 | .27 | .26 | .26 | ||||||||

| HS #2 2004 (HS #2 x 2004) | .04 | .27 | .15 | .27 | ||||||||

| HS #2 2005 (HS #2 x 2005) | −.62 * | .28 | .17 | .26 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| High School #3 | −.69 *** | .09 | −.47 *** | .09 | −.75 *** | .22 | −.72 *** | .08 | −.47 *** | .09 | −.87 *** | .20 |

| HS #3 2002 (HS #3 x 2002) | .19 | .30 | .32 | .28 | ||||||||

| HS #3 2003 (HS #3 x 2003) | −.13 | .31 | .28 | .28 | ||||||||

| HS #3 2004 (HS #3 x 2004) | .68 * | .30 | .82 ** | .28 | ||||||||

| HS #3 2005 (HS #3 x 2005) | .58 * | .29 | .66 * | .27 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| N of Model | 5,523 | 5,523 | 5,523 | 5,374 | 5,374 | 5,374 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Pseudo R-squared | .02 | .07 | .07 | .02 | .07 | .08 | ||||||

Note: Covariates included in Models 2 and 3, but not shown, are gender, race/ethnicity generational status, parental education, familial home ownership, and family structure.

Significant at the .10 level with a two tailed test

Significant at the .05 level with a two tailed test

Significant at the .01 level with a two tailed test

Significant at the .001 level with a two tailed test

Table 4.

Coefficients from a Logistic Regression of WSA Program and Socioeconomic Background on Any and Four year College Attendance of High School Seniors Expectations of Completing College with robust standard errors

| Attended any college (2 or 4 year) | 4 year College Attendance | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| β | Std Error | β | Std Error | β | Std Error | β | Std Error | β | Std Error | β | Std Error | |

| 2002 | .07 | .10 | .06 | .10 | .13 | .15 | .01 | .10 | .00 | .10 | −.07 | .14 |

| 2003 | −.01 | .09 | .00 | .10 | −.06 | .14 | .01 | .09 | .00 | .10 | −.14 | .13 |

| 2004 | .08 | .10 | .12 | .10 | .00 | .14 | .18† | .10 | .21 * | .10 | −.10 | .14 |

| 2005 | .01 | .09 | .01 | .10 | .02 | .15 | .15 | .10 | .13 | .10 | −.01 | .14 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| High School #1 | .19 * | .08 | .23 * | .09 | .04 | .19 | .27 *** | .08 | .37 *** | .08 | −.14 | .18 |

| HS #1 2002 (HS #1 x 2002) | −.19 | .26 | .37 | .25 | ||||||||

| HS #1 2003 (HS #1 x 2003) | .25 | .26 | .62 ** | .25 | ||||||||

| HS #1 2004 (HS #1 x 2004) | .46 | .28 | .93 *** | .26 | ||||||||

| HS #1 2005 (HS #1 x 2005) | .54† | .29 | .62 * | .25 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| High School #2 | −.63 *** | .08 | −.33 *** | .09 | −.01 | .21 | −.45 *** | .09 | −.09 | .10 | −.03 | .22 |

| HS #2 2002 (HS #2 x 2002) | −.31 | .28 | −.04 | .30 | ||||||||

| HS #2 2003 (HS #2 x 2003) | −.29 | .29 | .12 | .31 | ||||||||

| HS #2 2004 (HS #2 x 2004) | −.37 | .29 | .12 | .32 | ||||||||

| HS #2 2005 (HS #2 x 2005) | −.66 * | .28 | −.49 | .32 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| High School #3 | −.75 *** | .09 | −.50 *** | .09 | −.76 *** | .20 | −.65 *** | .10 | −.35 *** | .10 | −.62 ** | .25 |

| HS #3 2002 (HS #3 x 2002) | .20 | .29 | .01 | .35 | ||||||||

| HS #3 2003 (HS #3 x 2003) | .37 | .28 | −.14 | .35 | ||||||||

| HS #3 2004 (HS #3 x 2004) | .66 * | .29 | .76 * | .33 | ||||||||

| HS #3 2005 (HS #3 x 2005) | .13 | .28 | .58† | .32 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| N of Model | 5,073 | 5,073 | 5,073 | 5,073 | 5,073 | 5,073 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Pseudo R-squared | .02 | .08 | .08 | .02 | .08 | .08 | ||||||

Note: Covariates included in Models 2 and 3, but not shown, are gender, race/ethnicity, generational status, parental education, familial home ownership, and family structure.

Significant at the .10 level with a two tailed test

Significant at the .05 level with a two tailed test

Significant at the .01 level with a two tailed test

Significant at the .001 level with a two tailed test

As discussed above, Year 2000 is the benchmark for pre-existing differences (prior to WSA program implementation). Our analysis of Table 2 shows there were consistently lower outcomes across the three WSA schools relative to the nonWSA schools although WSA High School #1 was not always significantly different. The Model 2 multivariate analysis restricted to Year 2000 (controlling for student composition) shows that these school differences can be largely accounted for by student characteristics except for WSA School #3 which continued to show significantly lower levels relative to the nonWSA schools across all outcomes (results not shown). It is notable that in Year 2000 all three schools, net of student composition, had negative coefficients and a consistent pattern of lower performance for all outcomes; for college preparation High Schools #1 and #3 were significantly lower than the nonWSA schools. These results broadly suggest that differences in academic outcomes prior to WSA for schools #1 and #2 were due to differences in study body composition, while the educational outcomes of students in WSA #3 were even lower than would be predicted from the composition of the student body.

Model 1 shows that, net of a general temporal trend, students at one WSA high school (#1) are on average more likely to plan to attend college relative to the nonWSA high schools and to have comparable rates of college preparation (SAT/ACT test taking). The other two WSA high schools, however, have much lower levels of college plans and preparation, especially high school #3. As WSA high schools disproportionately enroll a large share of disadvantaged students, Model 2 includes measures of school composition (gender, race/ethnicity, immigrant generation, parental education, home ownership, and family structure) as covariates. The adjusted school effects in this model show that the educational deficit of students at high school #2 can be entirely explained by demographic and socioeconomic composition. Net of composition, students at high school #1 are doing better than students at the nonWSA high schools. School #3 still on average lags behind even after holding student composition constant, but the observed gap is reduced by one-third or more.

Model 3 tests the hypothesis of program effectiveness. The interactions of WSA and year (in 2002, 2003, 2004, and 2005) tap the impact of the WSA program, net of demographic and socioeconomic composition, relative to the nonWSA schools in 2000. These results show that the WSA program was effective in WSA schools #1 and #3, but not in #2. The WSA effect was statistically significant in 2004 and 2005 for both four year college plans and having taken the SAT/ACT. In 2002 and 2003 the program had an effect only for SAT/ACT test taking and only for high school #1.

The highly negative value for the dummy variable representing school #3, net of temporal effects, indicates that there were many fewer students taking the SAT/ACT in 2000 in this school relative to the nonWSA program schools in 2000. This is consistent with the descriptive patterns in Table 2. The negative effect of high school #3 is reduced a bit when socioeconomic composition is held constant in Model 2. But, then it sinks to a much lower level when school and year are allowed to interact in Model 3, revealing the effect of the WSA program. The impact of the WSA program on high school #3 was lagged, but it did have a positive impact in 2004 and 2005 and basically acts to remove the difference between school #3 and the nonWSA schools initially observed in 2000 (prior to the program).

There are two important conclusions from Table 3. First, the WSA program appears to have had a more immediate and stronger impact on college preparation (SAT/ACT test taking) than on college plans. The differences in these effects may be due, in part, to an inflated sense of expectations to attend college as a socially desirable outcome. Behavior may be more tied to reality than attitudes, and college test taking behavior may be also influenced, and even managed, by school administrators and teachers. With the expectations of change created by the WSA program, there may have been encouragement or pressure on students take the SAT or ACT. The second conclusion is that the impact of the WSA program is evident for only two of the three program high schools. We discuss this unexpected pattern after considering the evidence of the WSA program on college attendance one year after high school graduation.

The logistic regression models in Table 4, which employ the same estimation strategy as Table 3, show the impact of school, year, and school by year interactions (program) on attending any college (left hand panel) and on attending a 4-year college in the year after high school graduation. At first glance the results of Table 4 appear very similar to those for college planning—a lagged effect after a couple years for WSA schools #1 and #3, but not for school #2. But a closer look notes that the results are more complex. Model 3 shows that high school #1 was comparable to the nonWSA schools in terms of sending students to college before the WSA program was implemented. WSA high school #1 had a positive effect on sending students to 4 year colleges in 2002 (relative to 2000), but the impact only becomes statistically significant in 2003, 2004, and 2005. The stronger and more consistent effects of the WSA on program on “attending a 4 year college” than on “any college” undoubtedly reflects the WSA policy to direct scholarship recipients to 4 year colleges.

In 2000, high school #3 was in a deep hole—only 17 percent of seniors went to a 4 year college—only about ½ the rate of the nonWSA high schools (see Table 2). The multivariate results in Table 4 show that there was little progress in sending students to college in WSA school #3 in 2002 and 2003, but then there was a sizable jump in the WSA program’s impact in 2004 and 2005. This lagged effect of the program is very similar to the results for SAT/ACT test taking as reported in Table 3.

The general lack of a WSA program effect on “attending any college” reflects the very modest barriers to attending a two year college prior to the WSA program. Community college tuition costs are low and many students continue to live at home. There are few prerequisites to entry and registration can be done at any time prior to entry. Indeed the goal of the WSA program was to encourage attendance at a four year college. Given the affordability and ease of access to community colleges, it is not too surprising the WSA program was more consequential for attending a 4 year college than any college.

The emergence of a significant WSA program effect in 2004 might be explained in several ways. One possibility is simply the maturation of the WSA program and the delayed general impact on specific forms of capital (e.g. cultural capital). All intervention programs take some time to “settle down” and to begin to change behavior. Habits and customs, which are governed by inertia as much as objective forces, are slow to change. Another reason might be that some aspects of the WSA program were phased in over time and have a differential effect on cohorts of students (i.e. seniors and juniors have less exposure to changes than sophomores and freshman).

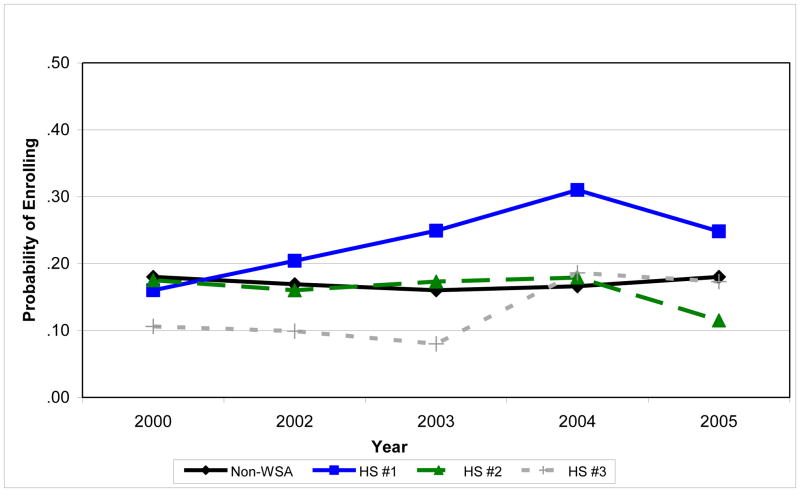

Figures 1 and 2 “translate” the logistic regression coefficients into predicted probabilities for an illustrative case of a typical student that the WSA program was designed to assist. These figures show the probabilities that a native born African American male student (living in an owner occupied home, from a non-intact family, and without a parent who had attended college) had taken the SAT/ACT (shown in Figure 1) and had attended a 4 year college (shown in Figure 2) for each year from 2000 to 2005 by high school attended. In 2000, African American male students (with all the attributes noted above) in the nonWSA high schools had a modest advantage over black males in the WSA high school, especially high school #3. Over the years following the implementation of the WSA program, black students in high school #1 were more likely to take the SAT/ACT and to attend a 4 year college than comparable students in the nonWSA schools. There was essentially no change in the probability in either outcome for comparable black students in high school #2. Black students in WSA high school #3, who were furthest behind in 2000, narrowed the gaps with their peers in nonWSA schools in 2004 and 2005, but remained behind. These predicted probabilities are broadly consistent with the overall between-school patterns shown in Tables 3 and 4. The WSA did make a difference in two of the three WSA schools, although the effect was not immediate but rather developed over the period.

Figure 1. Probability of Taking a College Placement Exam (SAT or ACT) by High School Attended.

Note: The predicted probabilities are for a third generation, African-American Male, from a non-intact family. The parent did not attend college but the family owns the home in which they live.

Figure 2. Probability of Attending a Four Year College by High School Attended.

Note: The predicted probabilities are for a third generation, African-American Male, from a non-intact family. The parent did not attend college but the family owns the home in which they live.

Why should the effect of the WSA program vary across high schools and why was there no measurable impact of the WSA scholarships in high school #2? These questions are not empirically addressed here, but informed speculation is possible. As indicated in our prior discussion, features of the program implementation while standardized in character (i.e. all WSA schools required an early mentoring structure), were organized and implemented by the teaching staff and administration in each high school. These local variations in implementation and style may have led to differential impacts in educational outcomes. There were also school differences before the WSA program was implemented. For example, the “normal” rate of college attendance for each high school may reflect the demographic and socioeconomic composition of students, the available educational opportunities, and specific school practices (such as curriculum, counseling, etc.) and culture of each institution. The rate of college going will vary with changes in any of these antecedent conditions as well as with economic circumstances and other period influences (availability of community colleges, subsidized loan programs).

In surveying the descriptive data for each WSA high school, we observed that high school #1 had an unusually high in-transfer rate of students (compared to high schools #2 and #3). This pattern is long standing and is not simply a response to the WSA program. Students may be more likely to transfer to school #1, which has a reputation for sending more students to college than other low income high schools. These transfers may even be selective of highly motivated students from more ambitious families. Also, the school had a special curricular program for college bound students.

As observed earlier, the below average rate of college going (relative to the nonWSA high schools) of high school #2 in the year 2000 is entirely due to demographic and socioeconomic composition (compare models 1 and 2 in the multivariate analysis). However, the even lower rate of college going of high school #3 is only partially explained by demographic and socioeconomic composition of the student body. Perhaps, other idiosyncratic factors of school #3 or selective out-transfers of college bound students contributed to a culture of “non-college going.” There is, however, a “bump” in the educational outcomes of students in high school #3 after a 2 year lag following the implementation of the WSA program. There is no bump for high school #2 for the years observed here. This difference is not due to fewer WSA scholarships in high school #2 relative to high school # 3; relatively equal numbers are given out across schools.

One possible clue is revealed by a decline in the number of non-eligible scholars (those not selected as scholarship recipients) going to college over time in high school #2. This pattern would be consistent with an interpretation that WSA scholarships were awarded to students in high school #2 who would have gone to college anyway (by access to other scholarships, borrowing funds, working extra jobs, etc.) and did not represent an expansion or a successful outreach to a previously non-college oriented group. Since the selection of scholars was centralized and consistent across the 3 WSA schools, we suspect that somewhat differential application patterns across high schools might explain variations in program effects. Differential application or differential recruitment of previously less encouraged students might result from school specific features of WSA implementation (mentoring, curriculum change, counseling, culture of college preparation, etc.).

Additional Analyses

Sometimes intervention projects are more successful with a subset of the population, perhaps because the nature of the program directly addresses the needs of some people. For example, the WSA program provides college scholarships to motivated students from low income households. We might expect that the program would be particularly effective for students from poor families. To examine this possibility and other differential effects of the WSA program, we estimated additional logistic regressions predicting educational outcomes with “interactions” of the program (WSA x Year) by each of the individual level covariates. The one consistently significant interaction of the WSA program was for students from disrupted families. Seniors from intact families have a marked advantage for all educational outcomes relative to other students. This difference was substantially reduced in WSA schools, where the program appeared to have been very effective in assisting students from disrupted families, (especially the 10 percent of students who report not having a mother or father figure in their lives) to make it to a four year college. It is unclear if this effect is due to financial reasons (the scholarship) or that the program was particularly effective in targeting students from less stable families.

CONCLUSIONS

In 2000, before the WSA program began, there were significant differences in the college going patterns among the 3 high schools in the UW-BHS sample that were designated as “low income” by the WSA program and the two middle-class nonWSA high schools in the school district. These differences were largely, but not entirely due to demographic and socioeconomic composition of students.

After 4 years of the WSA program, there is strong evidence of a program effect in two of the three WSA high schools. One low income high school (#1), which was just barely behind the middle class nonWSA high schools at the outset, now has college going rates that exceed those of the non-program high schools. In the last two years, about 45 percent of students in high school #1 enrolled in a four year college compared to about one-third of their peers in the nonWSA high schools. In the most disadvantaged school (#3), there was not an immediate WSA effect, but after three years, there was a noticeable uptick in all educational outcomes. This lagged response has not erased the gap in college going with middle income schools, but there is a clear program effect. In high school #2, there is no evidence of any change in educational outcomes in response to the WSA program. Students in high school #2 apply for and receive WSA scholarships, but the overall rate of college going has not risen (and the gap with the nonWSA schools remains). There are two questions to address. First, what aspect of the WSA program was most consequential, and, second, why are there such wide variations among the three targeted high schools?

The WSA program represents a holistic attempt to address all of the capital deficits (financial, human, social, and cultural) that constrain the postsecondary schooling of low income students. In addition to scholarships for about 20% of students in the targeted high schools, there were also curricular and mentoring programs that were designed to universally raise educational ambitions and provide assistance in selecting and applying to college. Students from impoverished homes rarely have a family member who can provide advice on college planning and application. Without the encouragement and support of family and friends, many talented low income students may set their ambitions too low by postponing college or attending a nearby community college rather than going away to a four year college. By engaging hometown mentors and teachers in the process, the WSA program was designed to fill the deficits in human, social, and cultural capital experienced by many students in low income high schools.

Based on timing alone, we conclude that the scholarship component is the major reason for the positive WSA effect reported here. The scholarship program was announced immediately and has been the most visible element of the WSA program. WSA scholarships are also widespread—about a fifth of all seniors at the WSA high schools receive a four year college scholarship. Since the WSA scholars are identified midway through their junior year, the presence of so many scholarship recipients among the student body is a major change in the school culture.

The program of school reform and establishment of small schools (“academies” with their own identity and focus) in the traditional high school was only implemented after two or more years of planning by each high school’s administration and teachers. With the lag in implementation, the graduating seniors in 2004 and 2005 were only exposed to the school reforms for one year and two years, respectively. Moreover, any program of school reform probably takes time to mature. During the first year or two, teachers and students may not be as familiar and comfortable with the new organization and processes as they will eventually be.

One modest test of the relative impact of the scholarships and school reform is to see if there was a “spillover effect” of WSA program on non-scholarship students in WSA schools. We ran additional models beyond those reported in tables 3 and 4, with an individual-level dummy variable for WSA scholars as an additional covariate (detailed results not presented here). The positive impact of a WSA school on postsecondary educational outcomes was entirely mediated by this covariate. So, there is no immediate evidence of a spillover effect on students who did not receive scholarships in WSA schools, but this cultural change may require a longer time horizon to take hold.

The impact of any major school reform is likely to vary with school level characteristics, including school composition, leadership and implementation of the program, and other idiosyncratic features of school structure and culture. A key feature of the WSA program that could be manipulated by the local school was the number and caliber of students who were encouraged to apply for WSA scholarships. The selection of WSA scholars among applicants was conducted externally (and thus not ‘manipulatable’ by the local school staff). However, the opportunity to apply for a WSA scholarship was an open process among eligible students. It is easy to imagine that school staff varied in their efforts to promote student applications.

The lack of any WSA effect at high school #2 suggests that WSA scholars (and applicants) were primarily among students who would have gone on to college even in the absence of a WSA program. Prior to the program, low income students may have had to work at extra jobs (before or after college entry), take more student loans, and apply for need based scholarships. The WSA program may have provided a substitute for these activities at high school #2. And perhaps, the WSA program will have a positive long term impact on college continuation and graduation for students from high school #2.

The immediate program impact at high school #1 indicates that this high school was waiting for the additional resources provided by the WSA program. Even in 2000, before the WSA program started, high school #1 sent as many high school students to college as the middle class control high schools did and almost as many to four year colleges. Once student composition was held constant, high school #1 was more likely to send students to college (Model 2 in Table 4). With the WSA program resources, high school #1 sent a much higher proportion of its students to college than the higher-income (non-program) schools. There are probably some intangible characteristics that explain the success of high school #1. High School #1 attracts a disproportionate share of in-transfer students relative to the two other (WSA) high schools. We suspect that the positive attributes that contribute to the above average in-transfer rate in high school #1 are also reflected in the very proportion of students who go on to college. High school #1 was ready to go, and the WSA program was the catalyst.

High school #3 probably represents a more likely scenario for most low income high schools. The WSA program had an impact, but it took a few years for the new opportunities to be realized. Work by Kanter (1983), Rogers (1995), and Oldenburg and colleagues (1997) lends insight to this process and suggests why there might be delays and variation in adoption of proposed structural and cultural changes in schools that eventually lead to successful outcomes. For such programmatic interventions as WSA expectations of immediate effects are probably not realistic and lags in effects should be expected in the evaluation of success; structural/cultural changes in organizations require adoption and adaption that may delay immediate and full implementation. Conversely, relying partly on internal agents for change holds the possibility of failure. In this sense high school #2 requires more detailed exploration to understand the factors that inhibited the success, even lagged success, observed in the other two schools.

Our results indicate that organizational change is slower and sometimes more hesitant than many would like. Perhaps if it were possible to easily to raise educational ambitions and performance, there would be less debate over how to do it. But it is important to realize concentrated efforts to change public schooling, especially if tied to generous programs of financial aid, can make a significant difference in raising college attendance.

Highlights.

We examine whether the Washington State Achiever program increases college plans and attainment.

We use a quasi-experimental design based on pre- and post-intervention surveys of high school seniors.

We find a (significant) net positive program effect on four year college attendance.

The magnitude of the program effect is uneven across school contexts.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The authors thank Rosanna Lee for her research assistance and Anil Deolalikar, Edward St. John, and William Sedlacek for their comments on earlier versions of this paper. The authors are responsible for any remaining errors.

Footnotes

To delineate between two and four year colleges we use the 2005 Carnegie classification of institutions.

The institutional classification was based upon the highest degree offered by the institution (Associates or Baccalaureate). For the few schools which offered both Associates and Baccalaureate degrees, we coded these schools based upon which type of degree was more prevalent amongst all degree recipients. Lastly, we coded the small number of schools without any form of accreditation and all special focus institutions as other post-secondary educational programs.

The 2005 Carnegie classification of institutions of higher education were used to code the institutions by the respondents. Information on the Carnegie classification of higher education institutions can be found at: http://www.carnegiefoundation.org/classifications/

Father or mother figures could be a step parent, an absentee parent, or another person, such as a grandparent, who plays the role of a mother or father

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abraham Katharine, Clark Melissa. Financial Aid and Students’ College Decisions: Evidence from the District of Columbia Tuition Assistance Grant Program. Journal of Human Resources. 2006 Summer;:576–610. [Google Scholar]

- ACT. Using EXPLORE And PLAN Data to Evaluate GEAR UP Programs. Washington, DC: National Council for Community and Education Partnerships; 2007. [Accessed on May 31, 2011]. from http://www.act.org/research/policymakers/pdf/gearup_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth-Darnell James W. Why Does It Take a Village? The Mediation of Neighborhood Effects on Educational Achievement. Social Forces. 2002;81:117–152. [Google Scholar]