Abstract

The case definitions for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) and chronic fatigue syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis stipulate that the experience of lifelong fatigue is an exclusionary criterion (Fukuda et al., 1994; Carruthers et al., 2003). This article examines the lifelong fatigue construct and identifies potential validity and reliability issues in using lifelong fatigue as an exclusionary condition. Participants in the current study completed the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire (Jason et al., 2010), and responses were examined to determine if they had experienced lifelong fatigue. This article discusses the extensive process that was needed to confidently discern which participants had or did not have lifelong fatigue. Using the most rigorous standards, few individuals were classified as having lifelong fatigue. In addition, those with and without lifelong fatigue had few significant differences in symptoms and functional areas. This article concludes with a recommendation that lifelong fatigue should no longer be used as an exclusionary criterion for CFS or ME/CFS.

Keywords: chronic fatigue syndrome, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, case definitions, exclusionary criteria, lifelong fatigue

Before a patient can be diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) or Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME), clinicians and researchers must rule out certain exclusionary conditions. For example, the Fukuda et al. (1994) criteria, which is the most widely used CFS case definition, excludes those with lifelong fatigue from a CFS diagnosis. Specifically, to meet the Fukuda et al. criteria, a participant must have “persistent or relapsing chronic fatigue that is of new or definite onset (has not been lifelong).” Since the creation of the Fukuda et al. (1994) case definition, several additional case definitions have been released, all of which vary regarding the use of lifelong fatigue as an exclusionary criterion. The Canadian clinical ME/CFS (Carruthers et al., 2003) case definition is similar to the Fukuda et al. (1994) case definition in that it also requires a “significant degree of new onset” of fatigue. Alternatively, the recently published Myalgic Encephalomyelitis International Consensus Criteria case definition (Carruthers et al., 2011) does not specify that participants who report lifelong fatigue should be excluded. Finally, although a revised Myalgic Encephalomyelitis case definition (Jason et al., 2012) requires an acute onset of the illness (due to a virus, infection, or other factors), it does not deem lifelong fatigue to be exclusionary.

Although neither the Fukuda et al. (1994) CFS case definition nor the Canadian clinical ME/CFS case definition (Carruthers et al., 2003) states the purpose of excluding those who have experienced lifelong fatigue, an article by Reeves et al. (2003) provides a partial explanation for this exclusionary criteria. The authors state that lifelong fatigue was noted as an exclusionary condition in order to exclude those with personality or somatization disorders. There are two problems with this explanation. First, these psychiatric disorders can be diagnosed directly, instead of relying on the presence of lifelong fatigue, a more indirect method. Second, there is no evidence that has been published to show that individuals with lifelong fatigue have more psychiatric problems.

If researchers are to use lifelong fatigue as an exclusionary criterion, there remain difficulties operationalizing the criteria. Neither the Fukuda et al. (1994) nor the Canadian clinical case definition (Carruthers et al., 2003) clearly specifies how lifelong fatigue should be defined or measured. Identifying true lifelong fatigue is possibly a subjective exercise that may be confounded by the limitations of a patient’s memory. It is difficult to determine whether patients have not experienced a time without fatigue or they simply cannot remember a time without fatigue. This confound is especially apparent for older individuals, those who have suffered from CFS or ME/CFS for a prolonged period of time, or individuals with a childhood onset of CFS or ME/CFS. Furthermore, the Fukuda et al. (1994) case definition seems to equate having fatigue of new or definite onset with fatigue that is not lifelong. The Fukuda et al. (1994) case definition does not indicate which is most important in identifying lifelong fatigue: having a definite illness onset or not remembering a time without fatigue problems.

Published empirical evidence is not available regarding this exclusion, therefore, research needs to be conducted to empirically determine if lifelong fatigue should be used as an exclusionary criterion. This article explores the process that is needed to determine if participants in a research sample have lifelong fatigue and reviews the challenges and reliability issues involved in operationalizing this construct. This article also reports for the first time on possible differences in functional health or symptoms between participants who report lifelong fatigue versus those who do not.

Method

Participants

The sample collected was an international convenience sample of 217 adults between the ages of 18 and 65 who self-identified as having CFS, ME/CFS, or ME. Of these participants, 21 were excluded due to morbid obesity or other exclusionary medical or psychiatric conditions, as specified by the Fukuda et al. (1994) case definition. Participants were required to be capable of reading and writing English and were recruited through sources such as internet forums and support groups, as well as re-contacting individuals who had previously expressed interest in participating in future DePaul University studies. Participants were given the option to complete questionnaires electronically, by hard-copy, over the phone, or in person at DePaul University’s Center for Community Research. They were not given a deadline to complete the questionnaire due to the unpredictability of illness symptoms, but the first 100 participants to complete the questionnaire received a $5.00 Amazon.com gift certificate.

The sample was 83.6% female and 16.4% male, and the mean age of participants was 51.6 (SD = 11.1). Of this sample, 97.4% identified as white, 0.5% as Asian, and 2.1% as “Other.” The majority of the sample was not working, with 54.9% reporting that they were on disability and 13.3% working part- or full-time. Regarding education, 40.0% of participants had a graduate or professional degree; 35.4% had a college degree; 17.9% had completed at least one year of college; and 6.7% had a high school degree or equivalent.

Materials

The DePaul Symptom Questionnaire (DSQ)

Participants completed the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire (DSQ) (Jason et al., 2010), a self-report measure consisting of items related to core symptoms, illness onset, and other relevant information needed to determine whether participants met case definition criteria. The development of the DSQ was based upon the CFS Questionnaire (Jason et al., 1997), which evidences good inter-rater and test-retest reliability and sensitively distinguishes among individuals with CFS, individuals with Major Depressive Disorder, and healthy controls (Hawk, Jason, & Torres-Harding, 2006). For the DSQ, participants used 5-point Likert scales to rate each symptom’s frequency and severity over the past six months. Frequency was rated on the following scale: 0=none of the time, 1=a little of the time, 2=about half the time, 3=most of the time, and 4=all of the time; and severity was rated on the following scale: 0=symptom not present, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe, 4=very severe. Frequency and severity scores were converted to a 100-point scale by multiplying the score by 25, and the frequency and severity scores were averaged to create a composite score for each symptom.

Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36 or RAND Questionnaire)

Participants also completed the SF-36, a 36-item questionnaire related to functional health (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992). Higher subscale scores indicate less impairment in functioning due to health. The SF-36 evidences internal consistency, significant discriminant validity among subscales, and can differentiate between patient and non-patient populations (McHorney, Ware, Lu, & Sherbourne, 1994).

Procedure

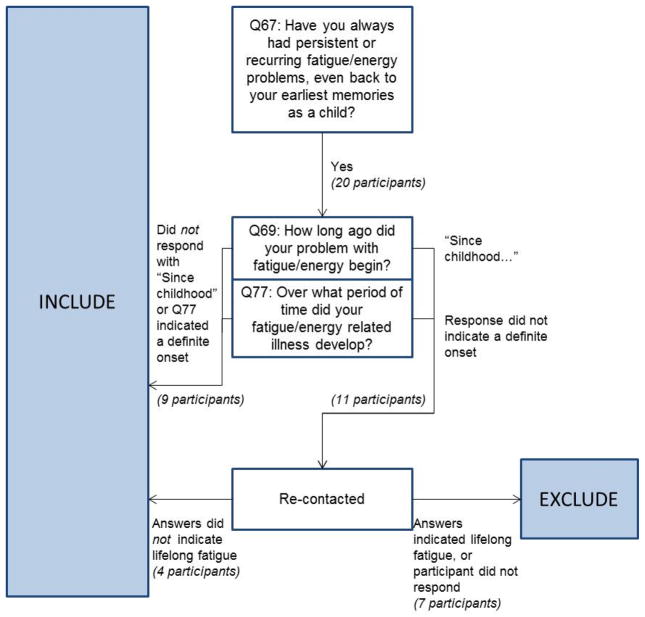

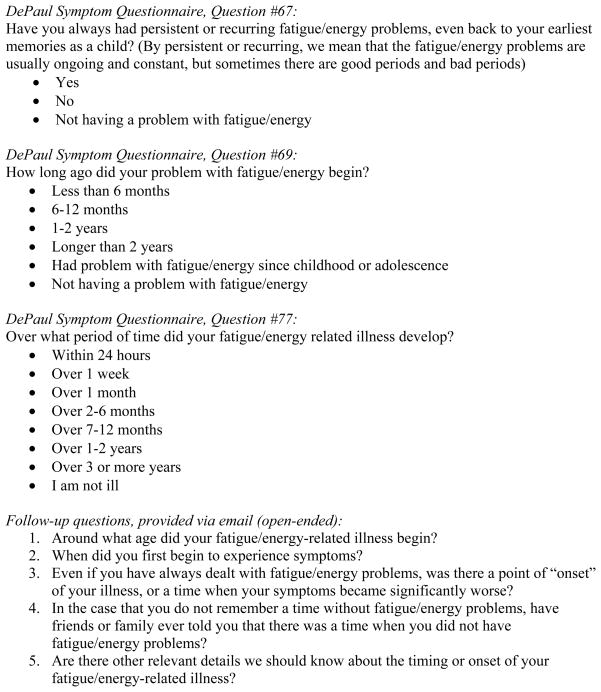

Figure 1 illustrates the process that was needed to determine whether participants should be excluded due to experiencing lifelong fatigue, and Figure 2 lists the questions used and specific responses participants could select for each question. Initially, participants’ responses to the question, “Have you always had persistent or recurring fatigue/energy problems, even back to your earliest memories as a child?” (Question 67 in the DSQ) were noted. Of the participants who answered “Yes” to this question, responses to two additional questions related to lifelong fatigue were considered. The question “How long ago did your fatigue/energy problem begin?” indicated whether participants remembered a time prior to their illness, and the question “Over what period of time did your fatigue/energy related illness develop?” indicated whether their illness had a new or definite onset (Questions 69 and 77 in the DSQ). Based on responses to these two questions, participants with suspected lifelong fatigue were re-contacted and asked five additional questions about the onset of their illness: (1) Around what age did your fatigue/energy-related illness begin? (2) When did you first begin to experience symptoms? (3) Even if you have always dealt with fatigue/energy problems, was there a point of “onset” of your illness, or a time when your symptoms became significantly worse? (4) In the case that you do not remember a time without fatigue/energy problems, have friends or family ever told you that there was a time when you did not have fatigue/energy problems? (5) Are there other relevant details we should know about the timing or onset of your fatigue/energy-related illness? Responses to these open-ended questions provided the information needed to determine which participants truly had lifelong fatigue.

Figure 1.

Illustration of process used to determine if participants should be excluded due to lifelong fatigue

Figure 2.

Questions and possible responses used to determine if participants should be excluded due to lifelong fatigue

Results

Of the 196 participants who did not report medical or psychiatric exclusionary conditions, 20 participants answered “Yes” to the initial screening question (Question 67), indicating they had always experienced fatigue or energy problems. However, of these 20 participants with suspected lifelong fatigue, 9 participants’ responses to the second set of questions (Questions 69 and 77) indicated that they could remember a time prior to their illness or that they had new or definite onset. The remaining 11 participants were re-contacted to request responses to the five open-ended questions, and 9 of these participants responded. Based on their responses, it was clear that 4 did not have lifelong fatigue, as they could identify an age when their problems with fatigue and energy began. The remaining 5 participants who responded to the follow-up questions did appear to have lifelong fatigue. For the 2 participants who did not respond, we counted them as lifelong fatigued, as we did not have sufficient evidence to indicate that they had a new or definite onset of their fatiguing illness. In summary, of the 20 participants who initially seemed as if they might have experienced lifelong fatigue (and had no other medical or psychiatric exclusionary conditions), only 7 truly needed to be excluded as having lifelong fatigue after examining more detailed descriptions of the onset of their illness.

The group of 7 participants with lifelong fatigue (henceforth referred to as the Lifelonga group) was compared to the group of participants who met the Fukuda et al. (1994) case definition criteria. Because of the small sample size of the Lifelonga group, the larger group of 20 participants who expressed always having had fatigue problems (hereupon referred to as the Lifelongb group) was also compared to the participants who met the Fukuda et al. (1994) criteria. This second comparison allows us to determine if significant differences would be found had only one question been used to determine the presence of lifelong fatigue.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of each group, as well as the presence of psychiatric illness; no significant demographic or psychiatric differences were found between the Lifelonga group and the Fukuda group or between the Lifelongb group and the Fukuda group.

Table 1.

Demographics and Psychiatric Characteristics

| Age | Lifelonga | Fukuda | Sig. | Lifelongb | Fukuda | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| 49.4 (9.5) | 51.6 (11.3) | 55.6 (10.1) | 51.1 (11.3) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Other Demographic Information: | N (%) | N (%) | Sig. | N (%) | N (%) | Sig. |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1 (14) | 30 (17) | 2 (10) | 29 (17) | ||

| Female | 6 (86) | 151 (83) | 18 (90) | 137 (83) | ||

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 6 (86) | 177 (98) | 19 (95) | 163 (98) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Other | 1 (14) | 3 (2) | 1 (5) | 3 (2) | ||

| Work status | ||||||

| On disability | 3 (43) | 101 (56) | 9 (45) | 93 (56) | ||

| Student | 0 (0) | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | 6 (4) | ||

| Homemaker | 0 (0) | 9 (5) | 2 (10) | 7 (4) | ||

| Retired | 1 (14) | 22 (12) | 4 (20) | 19 (11) | ||

| Unemployed | 1 (14) | 22 (12) | 3 (15) | 20 (12) | ||

| Working part-time | 1 (14) | 14 (8) | 1 (5) | 14 (8) | ||

| Working full-time | 1 (14) | 7 (4) | 1 (5) | 7 (4) | ||

| Educational level | ||||||

| High school | 0 (0) | 13 (7) | 1 (5) | 12 (7) | ||

| Partial college | 2 (29) | 32 (18) | 4 (20) | 30 (18) | ||

| Standard college degree | 2 (29) | 64 (35) | 8 (40) | 57 (34) | ||

| Graduate/Professional degree | 3 (43) | 72 (40) | 7 (35) | 67 (40) | ||

| Lifetime psychiatric diagnosis | ||||||

| Yes | 3 (43) | 77 (42) | 9 (45) | 71 (43) | ||

| No | 4 (57) | 105 (58) | 11 (55) | 96 (57) | ||

Table 2 displays the results of ANOVAs that compared the eight SF-36 subscale scores of the groups. One significant difference was found between the Lifelonga group and the Fukuda group. The Lifelonga group had significantly higher Role Emotional scores than the Fukuda group [F(1, 187) = 7.85, p = 0.02]. No significant differences were found between the Lifelongb group and the Fukuda group.

Table 2.

SF-36 Subscales (Higher score indicates less impairment)

| Lifelonga | Fukuda | Sig. | Lifelongb | Fukuda | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Physical Functioning | 35.7 (16.2) | 29.6 (18.3) | 33.6 (18.4) | 29.4 (18.3) | ||

| Role Physical | 0.0 (0.0) | 4.8 (15.1) | 1.3 (5.6) | 4.9 (15.6) | ||

| Bodily Pain | 50.6 (20.7) | 41.4 (22.5) | 41.9 (27.0) | 41.7 (21.9) | ||

| General Health | 20.0 (15.5) | 25.1 (14.3) | 23.1 (18.2) | 25.3 (13.9) | ||

| Social Functioning | 28.6 (24.7) | 20.3 (20.3) | 26.9 (23.7) | 19.8 (19.9) | ||

| Mental Health | 66.9 (22.8) | 71.7 (16.7) | 70.2 (18.6) | 71.7 (16.9) | ||

| Role Emotional | 95.2 (12.6) | 79.9 (36.9) | * | 75.0 (41.7) | 80.8 (35.9) | |

| Vitality | 12.1 (11.1) | 12.9 (13.0) | 10.3 (11.1) | 13.4 (13.1) |

p < 0.05

Table 3 displays the results of ANOVAs that compared the groups’ symptom scores. Of the 54 symptoms, only 1 symptom was significantly different between the Lifelonga group and the Fukuda group. The Lifelonga group had significantly worse scores related to needing to nap daily [F(1,181) = 38.61, p < 0.001]. When comparing the Lifelongb group to the Fukuda group, only 4 symptoms showed significant differences: Needing to nap daily [F(1,179) = 6.23, p = 0.01], bladder problems [F(1,185) = 4.72, p = 0.03], irritable bowel problems [F(1,184) = 13.23, p < 0.001], and having no appetite [F(1, 184) = 6.02, p = 0.02]. For each of these symptoms, the Lifelongb group reported worse symptom scores than the Fukuda group. Given the large number of comparisons and inflated risk of Type I error (a Bonferroni adjustment indicates that only symptoms that are significant at the p < 0.001 level should be interpreted as significant), several of the significant findings above may solely be due to chance.

Table 3.

Symptoms (Higher score indicates more impairment)

| Lifelonga | Fukuda | Sig. | Lifelongb | Fukuda | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Fatigue | 79.2 (10.2) | 79.4 (16.0) | 83.6 (11.8) | 78.9 (16.3) | ||

| Post-exertional malaise | ||||||

| Dead, heavy feeling after starting to exercise | 76.8 (27.4) | 68.0 (29.0) | 73.8 (24.3) | 67.3 (29.4) | ||

| Next-day soreness after non-strenuous activities | 76.8 (22.2) | 74.4 (20.7) | 78.8 (19.9) | 74.0 (20.6) | ||

| Mentally tired after slightest effort | 71.4 (20.0) | 62.7 (24.9) | 68.8 (23.8) | 62.0 (24.8) | ||

| Minimum exercise makes you tired | 75.0 (16.1) | 75.8 (23.5) | 70.6 (23.7) | 76.4 (23.3) | ||

| Physically drained/sick after mild activity | 76.8 (16.8) | 72.1 (24.0) | 75.0 (18.6) | 71.6 (24.2) | ||

| Sleep | ||||||

| Unrefreshing sleep | 75.0 (10.2) | 78.7 (21.6) | 79.4 (23.0) | 78.3 (21.2) | ||

| Need to nap daily | 85.7 (13.4) | 51.3 (30.3) | *** | 69.1 (30.2) | 50.9 (30.0) | * |

| Problems falling asleep | 64.3 (36.4) | 60.6 (31.4) | 67.1 (36.4) | 60.0 (31.1) | ||

| Problems staying asleep | 64.6 (24.3) | 62.3 (30.2) | 70.8 (25.7) | 61.6 (30.3) | ||

| Waking up early in the morning | 53.6 (32.0) | 49.0 (33.0) | 58.1 (31.7) | 48.2 (32.9) | ||

| Sleeping all day/staying awake all night | 12.5 (23.9) | 17.5 (28.0) | 23.8 (33.4) | 16.5 (27.2) | ||

| Pain | ||||||

| Muscle pain | 57.1 (26.9) | 62.2 (26.0) | 61.8 (30.8) | 62.0 (25.6) | ||

| Pain in multiple joints | 35.7 (32.6) | 51.1 (33.0) | 50.0 (36.7) | 50.5 (32.8) | ||

| Eye pain | 39.3 (28.3) | 32.4 (28.4) | 35.6 (27.9) | 32.2 (28.6) | ||

| Chest pain | 16.1 (23.6) | 25.4 (24.5) | 18.8 (23.8) | 25.6 (24.5) | ||

| Bloating | 53.6 (18.7) | 44.8 (27.8) | 53.8 (24.4) | 44.3 (27.7) | ||

| Abdomen/stomach pain | 51.8 (21.0) | 37.4 (25.6) | 45.4 (26.1) | 37.0 (25.4) | ||

| Headaches | 48.2 (23.3) | 48.8 (25.1) | 48.8 (26.9) | 48.9 (24.9) | ||

| Neurocognitive | ||||||

| Muscle twitches | 37.5 (22.8) | 31.6 (25.6) | 38.8 (22.2) | 30.9 (25.8) | ||

| Muscle weakness | 64.3 (16.8) | 60.2 (27.8) | 61.9 (32.8) | 60.0 (27.0) | ||

| Sensitivity to noise | 64.3 (24.4) | 60.9 (27.6) | 59.7 (29.3) | 60.8 (27.3) | ||

| Sensitivity to bright lights | 60.7 (23.3) | 57.0 (29.0) | 63.8 (27.0) | 56.0 (28.9) | ||

| Problems remembering things | 53.6 (25.7) | 66.2 (22.5) | 68.1 (24.7) | 65.4 (22.6) | ||

| Difficulty paying attention for long periods of time | 55.4 (32.2) | 72.0 (25.1) | 69.4 (26.4) | 71.5 (25.5) | ||

| Difficulty expressing thoughts | 60.7 (21.0) | 62.4 (23.8) | 68.8 (22.0) | 61.3 (23.7) | ||

| Difficulty understanding things | 50.0 (19.1) | 47.4 (23.7) | 51.3 (22.8) | 46.8 (23.7) | ||

| Can only focus on one thing at a time | 69.6 (18.9) | 68.9 (27.7) | 71.9 (27.8) | 68.4 (27.5) | ||

| Unable to focus vision/attention | 48.2 (29.3) | 49.1 (24.6) | 56.9 (27.6) | 47.8 (24.2) | ||

| Loss of depth perception | 16.1 (23.6) | 26.3 (31.5) | 30.3 (40.7) | 25.0 (30.0) | ||

| Slowness of thought | 62.5 (14.4) | 58.3 (24.2) | 61.3 (26.3) | 58.1 (23.8) | ||

| Absent-mindedness | 60.7 (21.0) | 60.3 (26.9) | 64.4 (27.0) | 59.8 (26.8) | ||

| Autonomic | ||||||

| Bladder problems | 37.5 (33.1) | 29.7 (32.2) | 44.4 (35.0) | 28.1 (31.3) | * | |

| Irritable bowel problems | 64.3 (23.3) | 45.2 (31.4) | 69.4 (27.3) | 43.1 (30.7) | *** | |

| Nausea | 25.0 (21.7) | 32.0 (23.9) | 28.8 (20.3) | 31.8 (24.1) | ||

| Feeling unsteady on feet | 51.8 (18.3) | 41.5 (26.3) | 50.6 (28.8) | 40.3 (25.4) | ||

| Shortness of breath | 28.6 (23.6) | 38.2 (26.3) | 42.5 (29.6) | 36.9 (25.7) | ||

| Dizziness/fainting | 45.8 (23.3) | 38.2 (25.3) | 42.1 (26.1) | 37.8 (25.2) | ||

| Irregular heart beats | 35.4 (9.4) | 31.6 (27.1) | 37.5 (31.2) | 30.6 (26.0) | ||

| Neuroendocrine | ||||||

| Losing/gaining weight without trying | 39.3 (21.0) | 37.8 (34.5) | 51.3 (32.9) | 36.0 (34.0) | ||

| No appetite | 19.6 (24.9) | 22.2 (23.6) | 33.8 (24.7) | 20.3 (22.9) | * | |

| Sweating hands | 25.0 (36.1) | 11.3 (20.6) | 17.5 (30.7) | 11.0 (20.0) | ||

| Night sweats | 50.0 (19.1) | 33.9 (30.4) | 41.3 (31.2) | 33.5 (30.1) | ||

| Cold limbs | 53.6 (25.7) | 52.1 (30.4) | 58.1 (28.2) | 51.2 (30.4) | ||

| Chills/shivers | 21.4 (17.3) | 35.2 (27.9) | 33.8 (26.9) | 34.3 (27.7) | ||

| Feeling hot/cold for no reason | 51.8 (33.4) | 51.0 (28.8) | 56.3 (29.1) | 50.2 (29.0) | ||

| Feeling like you have a high temperature | 37.5 (34.6) | 31.4 (29.3) | 40.0 (36.2) | 30.7 (28.5) | ||

| Feeling like you have a low temperature | 30.4 (23.8) | 28.1 (29.4) | 30.0 (33.5) | 27.5 (28.6) | ||

| Alcohol intolerance | 64.3 (45.3) | 47.9 (39.7) | 52.5 (45.1) | 48.0 (39.2) | ||

| Immune | ||||||

| Sore throat | 35.7 (28.3) | 35.6 (23.3) | 35.5 (27.1) | 35.7 (23.2) | ||

| Tender lymph nodes | 51.8 (31.0) | 42.2 (28.5) | 52.5 (28.6) | 41.2 (28.5) | ||

| Fever | 10.7 (13.4) | 14.8 (20.6) | 24.4 (25.5) | 13.4 (19.5) | ||

| Flu-like symptoms | 60.4 (30.0) | 52.5 (26.6) | 58.6 (30.9) | 52.0 (26.3) | ||

| Sensitivity to smells/foods/medications/chemicals | 69.6 (35.2) | 54.5 (35.8) | 63.8 (33.4) | 53.5 (35.9) |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.001

Discussion

The current study found that when comparing the group of participants who reported always having had lifelong fatigue versus the others who did not have lifelong fatigue, few significant differences were found in SF-36 subscale scores or in the majority of symptom composite scores. An extensive process was required to determine which participants in this study had truly experienced lifelong fatigue and therefore should be excluded according to the Fukuda et al. (1994) and Canadian clinical (Carruthers et al., 2003) case definitions. Asking participants if they could not remember a time without fatigue was not sufficient to accurately determine the presence of lifelong fatigue. The primary difficulty involved parsing the participants who had true lifelong fatigue from those who had simply suffered from fatigue for a long time. Several participants reported not remembering a time without fatigue problems but could still identify a point of sudden, definite onset when their symptoms became disabling or significantly worse. For example, some participants who reported always having fatigue problems actually had sudden, infectious onsets (after contracting mononucleosis) during early adolescence. Therefore, this study suggest that some participants using the Fukuda et al. (1994) criteria and the Carruthers et al. (2003) criteria are being inappropriately excluded from a CFS or ME/CFS diagnosis due to lifelong fatigue, as their responses to several questions related to lifelong fatigue indicated that they did not have lifelong fatigue.

To confidently discern which participants in this sample truly had experienced lifelong fatigue, the original three discrete-answer questions that were used had to be supplemented with five open-ended questions, as detailed descriptions of illness onset were needed to confidently exclude participants based on this criterion. The large number of questions required could introduce validity and reliability issues when researchers try to operationalize this criterion. If researchers cannot accurately and consistently identify participants with lifelong fatigue, then participants may be arbitrarily excluded. The need for open-ended questions also increases the chance of reliability issues, as most investigators will not use questionnaires that include all the needed questions.

This study needs to be replicated with other studies to determine if similar findings emerge. The low numbers of individuals in the lifelong fatigue group surely reduced power in a number of comparisons. However, this study found that an extensive effort was required to identify only a few cases of lifelong fatigue and accompanying risk of reliability issues. There was also a lack of significant differences in psychiatric comorbidity, functional status, or symptom scores between the two groups. In summary, the current study suggests that lifelong fatigue should no longer be used as an exclusionary criterion for CFS or ME/CFS case definitions.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by NIAID (grant numbers AI 49720 and AI 055735).

References

- Buchwald D, Pearlman T, Umali J, Schmaling K, Katon W. Functional status in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, other fatiguing illnesses, and healthy individuals. American Journal of Medicine. 1996;101:364–370. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(96)00234-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers BM, Jain AK, De Meirleir KL, Peterson DL, Klimas NG, Lerner AM, van de Sande MI. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Clinical working case definition, diagnostic and treatments protocols. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 2003;11:7–115. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, Klimas NG, Broderick G, Mitchell T, Stevens S. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: international consensus criteria. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2011;270(4):327–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawk C, Jason LA, Torres-Harding S. Reliability of a chronic fatigue syndrome questionnaire. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 2006;13(4):41–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A. The chronic fatigue syndrome: A comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1994;121:953–959. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Damrongvachiraphan D, Hunnell J, Bartgis L, Brown A, Evans M, Brown M. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: Case definitions. Autonomic Control of Physiological State and Function. 2012;1:1–14. doi: 10.4303/acpsf/K11060. Available at: http://www.ashdin.com/journals/ACPSF/K110601.pdf. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Evans M, Porter N, Brown M, Brown A, Hunnell J, Friedberg F. The development of a revised Canadian myalgic encephalomyelitis chronic fatigue syndrome case definition. American Journal of Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 2010;6(2):120–135. [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Ropacki MT, Santoro NB, Richman JA, Heatherly W, Taylor R, Plioplys S. A Screening Instrument for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Journal of chronic fatigue syndrome. 1997;3(1):39–59. [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA, Ware JE, Lu RL, Sherbourne D. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Medical Care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves WC, Lloyd A, Vernon SD, Klimas N, Jason LA, Bleijenberg G, Unger ER. Identification of ambiguities in the 1994 chronic fatigue syndrome research case definition and recommendations for resolution. BMC Health Services Research. 2003;3(1):25. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form health survey (SF-36): Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]