Abstract

Post-Exertional Malaise (PEM) is a cardinal symptom of the illnesses referred to as Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME), Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). PEM is reported to occur in many of these patients, and with several criteria (e.g., ME and ME/CFS), this symptom is mandatory (Carruthers et al., 2003, 2011). In the present study, 32 participants diagnosed with CFS (Fukuda et al., 1994) were examined on their responses to self-report items that were developed to capture the characteristics and patterns of PEM. As shown in the results, the slight differences in wording for various items may affect whether one is determined to have PEM according to currently used self-report criteria to assess CFS. Better understanding of how this symptom is assessed might help improve the diagnostic reliability and validity of ME, ME/CFS, and CFS.

Keywords: post-exertional malaise, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, chronic fatigue syndrome, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome

Post-Exertional Malaise (PEM) is a key symptom of the illness commonly referred to as Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) (Carruthers et al., 2003), Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) (Carruthers et al., 2011), and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) (Fukuda et al., 1994). PEM has been described as a cluster of symptoms following mental or physical exertion, often involving a loss of physical or mental stamina, rapid muscle or cognitive fatigability, and sometimes lasting 24 hours or more (Carruthers et al., 2003). PEM has been found to elicit a worsening of ME/CFS, ME and CFS symptoms including fatigue, headaches, muscle aches, cognitive deficits, insomnia, and swollen lymph nodes. It can occur after even the simplest everyday tasks, such as walking, showering, or having a conversation (Spotila, 2010). Unlike generalized fatigue, PEM is much more profound and reduces daily functioning. This symptom is characterized by a delay in the recovery of muscle strength after exertion, so it can cause patients to be bedridden for multiple consecutive days. Many patients attempt to cope with PEM by pacing themselves and limiting their activity (Jason, Muldowney, & Torres-Harding, 2008). PEM has been used to help differentiate CFS from other illnesses such as major depressive disorder (Hawk, Jason, & Torres-Harding, 2006).

The Fukuda et al. (1994) criteria as well as the empiric criteria (Reeves et al., 2005) for CFS do not require PEM in all patients. According to Fukuda et al. (1994) and Reeves et al. (2005), PEM is considered one of eight minor symptoms, of which a patient needs to meet four to receive a diagnosis. However, many other definitions for the illness do recognize PEM as a cardinal symptom. According to a recent review article by Jason et al. (2012), Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) case definitions, including Ramsay’s case criteria (1988), the London criteria (National Task Force Report on CFS/PVFS/ME, 1994), the Nightingale criteria (Hyde, 2007) and the Goudsmit et al. criteria (2009) require PEM as an essential feature of this illness, but there are slight differences in these definitions. Ramsay (1988) describes PEM as muscle fatigability that results from a minor degree of physical exercise and may last three or more days before full muscle power is restored. The London criteria (National Task Force Report on CFS/PVFS/ME, 1994) defines PEM as being precipitated by physical exertion as well as mental exertion. The London criteria also suggests that exercise-induced fatigue should be relative to the patient’s previous exercise tolerance, but a specific time period for which full muscle power should be restored was not provided (National Task Force Report on CFS/PVFS/ME, 1994). Similarly, the Nightingale criteria states that PEM can be precipitated by both mental and physical activity and describes PEM as pain with a rapid loss of muscle strength after moderate physical or mental activity (Hyde, 2007). Goudsmit et al. (2009) describe PEM as a new onset of abnormal levels of muscle fatigability that is elicited by minor levels of activity with symptoms getting worse during the next 24 to 48 hours.

PEM has been objectively demonstrated, as exercise lowers pain thresholds in patients with ME/CFS, ME and CFS while raising it in healthy controls. Furthermore, patients take longer to recover from muscle exertion and show both increased effort and lower performance on cognitive tests after exertion compared to control groups (Spotila, 2010). Both maximal and sub-maximal cardio-pulmonary exercise tests have been used to physiologically assess PEM. As discussed by Jason and Evans (2012), to measure maximum oxygen consumption or aerobic fitness with the maximal exercise tests, participants are instructed to pedal on a stationary bicycle at a prescribed rate against a gradually increasing resistance until volitional exhaustion or until the participant is unable to pedal at the prescribed rate (VanNess, Stevens, Bateman, Stiles, & Snell, 2010). For submaximal tests, participants are asked to sustain a lower level of effort for 25-30 minutes as compared to 5-9 minutes of more intensive effort for maximal tests (Light, White, Hughen, & Light, 2009). However, it is important to note that the PEM construct can also include the patients’ self-reported symptoms (Jason & Evans, 2012). Due to high costs and specific equipment needed, maximal and sub-maximal exercise tests are not always feasible. Therefore, self-report data are frequently used to document PEM (Jason, King, et al., 1999) or other symptoms. Lewis, Pairman, Spickett, and Newton (2012) conducted a study on a subgroup of patients with CFS who have postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). POTS can be objectively measured by autonomic function analysis or hemodynamic responses upon standing. This study revealed that a combined clinical assessment tool with the Epworth sleepiness scale and the orthostatic grading scale was able to accurately identify those with CFS and POTS with 100% positive and negative predictive values (Lewis et al., 2012). Likewise, there is a need to develop valid and reliable self-report methods for capturing the frequency, severity, and duration of PEM, a cardinal symptom of ME/CFS and ME.

Jason, King, and colleagues (1999) found that in a group of individuals with CFS, the number of individuals endorsing PEM ranged from 40.6-93.8% depending on how the question was assessing this symptom. This lack of uniformity in the way PEM is measured represents a significant problem for the scientific community. Due to vague wording, some individuals with ME/CFS, ME and CFS might not be identified as having PEM when they may actually be experiencing it. Accordingly, the purpose of the current study is to examine self-report items used to assess the experience of PEM and to evaluate the ways in which subtle changes in question wording can influence participant ratings of PEM. It is hoped that the examination of responses to different PEM questions will provide meaningful information about how to improve the way in which PEM is assessed; thus, ultimately helping to improve the diagnostic accuracy and reliability of ME/CFS, ME and CFS.

Methods

Participants

The adults in the current sample were previously evaluated in a larger community-based study for CFS (for more details on this study see Jason, Jordan, et al., 1999). There were 213 individuals who were medically and psychiatrically evaluated from 1995-1997 in three stages. Stage 1 involved the administration of an initial telephone screening questionnaire in order to assess for symptoms of CFS, Stage 2 involved administration of a semi-structured psychiatric interview, and Stage 3 involved the administration of a complete physical examination. Following complete evaluation, an independent group of physicians reached diagnostic consensus on all cases. Among the 32 individuals who were diagnosed with CFS, the focus of the current study is on eight individuals who were determined not to have PEM using the Fukuda et al. (1994) criteria. Self-report items and physician notes were utilized to analyze PEM symptomology.

Measures

Items in the current study were identified as self-report questions that inquired about PEM symptoms and were selected from the CFS Screening Questionnaire (Jason et al., 1997) and the Medical Questionnaire (Komaroff & Buchwald, 1991) used in the larger study. From the CFS Screening Questionnaire, participants rated yes or no to the question, ‘Do you feel generally worse than usual or fatigued for 24 hours or more after you have exercised?’ which was the main item used to determine the presence of PEM among the eight minor symptoms according to the Fukuda et al. (1994) criteria. Two other items that assessed aspects of PEM included answering yes or no to the following questions: ‘Do you experience high levels of fatigue or weakness following normal daily activity?’ and ‘Has your fatigue been present for more than 50% of the time?’ Duration and onset were also assessed with the items: ‘How long does the fatigue last after physical or mental exertion?’ (with possible responses including one hour, from one to three hours, or more than three hours, please specify) and ‘How long does it take the fatigue to begin after physical or mental exertion?’ (with possible responses including immediately, about one hour, from one to three hours, or more than three hours).

Two items from the Medical Questionnaire asked about other PEM symptoms during the last month and participants used the following rating scale: never suffer from it, suffered from it previously, mild or rare symptoms, moderate or frequent symptoms, or severe or very frequent symptoms for the following two items: ‘Prolonged feelings of fatigue after physical activity’ and ‘Excessive muscle fatigue with minor activity.’ Participants were also asked about their level of agreement with the statement, ‘Exercise brings on my fatigue’ by indicating one of the following ratings: strongly disagree, disagree, slightly disagree, unsure, slightly agree, agree, or strongly agree. A final question from the Medical Questionnaire asked participants to answer yes or no to the following question, ‘Has your fatigue impaired your daily life activities?’

Results

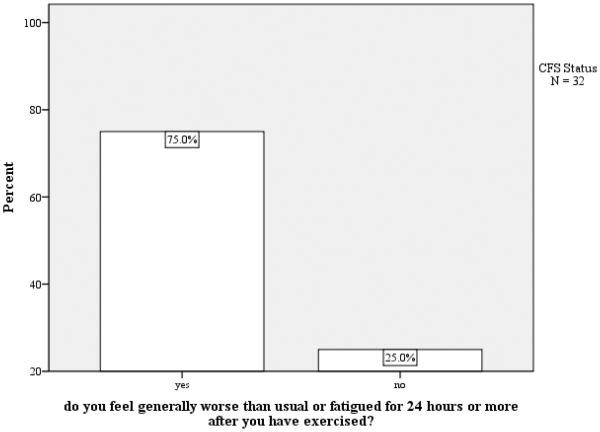

Figure 1 illustrates participant responses to the criterion Fukuda et al. (1994) question: ‘Do you feel generally worse than usual or fatigued for 24 hours or more after you have exercised?’ Although the majority (75%) of participants with diagnosed ME/CFS endorsed this item, a notable percentage (25%) responded ‘no,’ which could signify that these participants did not have PEM or they may have PEM but the defining item did not adequately capture this symptom. Hence, we examined the eight individuals who did not endorse this particular item and their responses to other PEM items to explore possible reasons for why PEM was not indicated as a symptom of these eight participants.

Figure 1.

Do you feel generally worse than usual or fatigued for 24 hours or more after you have exercised?

We had asked these eight participants a more general question: ‘Do you experience high levels of fatigue or weakness following normal daily activity?’ with no specific duration indicated. Interestingly, all eight participants experienced high levels of fatigue after ‘normal daily activity’. Furthermore, seven participants (with one missing response) responded ‘yes’ to the following two questions: ‘Has your fatigue been present for more than 50% of the time?’ and ‘Has your fatigue impaired your daily life activities?’

However, none of these eight indicated that they felt worse than usual for 24 hours or more after exercise. This indicates that a primary reason that these eight did not get counted as having a PEM symptom involved the issue of having less than 24 hours of feeling worse after exertion. We also asked two follow-up questions involving more details about the duration and onset of fatigue: ‘How long does the fatigue last after physical or mental exertion?’ and ‘How long does it take the fatigue to begin after physical or mental exertion?’ Five individuals indicated that their fatigue lasted less than 24 hours after physical or mental exertion. Only one individual specified fatigue that lasted exactly 24 hours and two participants indicated that they experience ‘more than three hours’ of fatigue with no time frame specified. Additionally, variations in onset of fatigue were found among these eight individuals. Three participants reported fatigue that is elicited ‘immediately,’ but the others all reported a delayed onset. For two participants, it took ‘about one hour,’ for two others, it took ‘from one to three hours,’ and for one participant, it took ‘more than three hours.’

It is possible that the term “exercise” was a critical word that differentiated those meeting Fukuda criteria for PEM versus not having PEM. To assess this, we asked participants’ level of agreement to the following statement: ‘Exercise brings on my fatigue.’ Aside from one participant who ‘strongly agreed’ that exercise brings on fatigue, most of these participants (five) did not agree with this item. Additionally, one participant was unsure, and one did not respond to this item. This suggests that fatigue among these eight participants was not caused by physical exercise as these individuals may not engage in exercise at all or it might be that mental exertion or other types of activity rather than exercise brings on their PEM.

We therefore asked these eight participants two additional items about symptoms that did not explicitly involve exercise but rather physical activity. Only two participants had ‘moderate or frequent symptoms’ of prolonged fatigue after physical activity. However, when asked about excessive muscle fatigue with minor activity, four participants indicated that they have ‘moderate or frequent symptoms,’ and one participant indicated ‘severe or very frequent symptoms.’ Evidently, referring to minor activity or physical activity might make a difference as does exercise versus excessive muscle fatigue.

In addition to the self-report items, the primary diagnosing physician’s notes were examined to see whether there was any additional information provided about PEM among these eight participants. Four of the participants were noted to have PEM symptoms during the medical interview. For another participant, it was noted that this individual “does not exercise much anymore.” Thus, because this individual had reduced levels of activity, it was unclear whether exercise would actually elicit PEM. It is uncertain from the medical notes whether or not the others might have had PEM, but at least 50% of the eight participants had this critical symptom based on these medical notes.

Discussion

Among the 32 participants with CFS, eight indicated that they did not feel worse than usual or fatigued for 24 hours or more after exercise. Thus, they were determined not to experience PEM according to the Fukuda et al. (1994) CFS criteria. However, we found that the words ‘exercise,’ ‘normal daily activity,’ ‘physical or mental exertion,’ ‘physical activity,’ ‘minor activity,’ ‘24 hours or more’ and ‘daily life activities’ connote important differences regarding whether or not PEM symptoms were endorsed among our sample. All eight participants who did not endorse the Fukuda et al. (1994) PEM questions did indicate that they experienced high levels of fatigue after normal daily activity. In addition, seven (with one missing response) stated that their fatigue is present more than 50% of the time and this fatigue had impaired their daily life activities.

These data suggest that there is a problem with the criterion item used to determine the presence of PEM. First of all, not all individuals may consistently exercise. Patients with ME/CFS, CFS, and ME may not exercise in order to avoid feelings of fatigue or they may be trying to stay within their energy envelope (Jason et al., 2008) as a means of functioning on a day to day basis. Thus, it is unclear whether participants were answering this criterion question based on the fact that they do not exercise or how they believe that they may feel if they were to exercise. Secondly, if participants have fatigue that is present for more than 50% of the time, fatigue that may arise after exercise might not make them feel any more fatigued than usual. Furthermore, while it is useful to ask about a range of activities, it could be problematic for some questions to have a time frame for the duration or onset of fatigue while other questions may not have this additional label. Therefore, there is a problem with the number of domains or constructs being tapped by the items that attempt to assess PEM.

In order to gauge PEM among the participants with CFS in our sample, several items revolved around fatigue were used in the self-report questionnaires. However, it is important to note that many individuals with these illnesses often feel that that the focus on fatigue trivializes the illness. Fatigue is usually experienced by healthy individuals in the general population, but the type of fatigue faced by patients is much more debilitating. In a study done by Jason et al. (2009), an instrument was developed to better measure different types of fatigue. The ME/CFS Fatigue Types Questionnaire (MFTQ) categorizes five hypothesized dimensions of fatigue with high internal consistency: post-exertional, wired, brain fog, energy, and flu-like fatigue. In the study by Jason et al. (2009), these five factors of fatigue emerged in patients, but only one factor of general fatigue was found for healthy controls. Within their control group, a significant and greater correlation was found between post-exertional fatigue and emotional distress; whereas, this relationship was not found in the patients. Moreover, a stronger relationship was found between post-exertional fatigue and the impact on one’s functional ability in the patients compared to the control group. Therefore, this study indicated that fatigue is actually viewed in a different manner by patients versus a healthy control sample.

While some items in our study specified the type of activity causing fatigue, only one question explicitly asked about muscle fatigue instead of using ‘fatigue’ in general. Because fatigue can be experienced by everyone, when measuring PEM, using the general term fatigue will not accurately differentiate patients from healthy controls. Therefore it is critical when using self-report surveys to contain questions that ask about both the ill-feelings of fatigue and the physical loss of muscle strength after mental or physical activity. By doing so, specific characteristics of PEM can be better identified with patients. Thus, as shown in the results of the current study, the word ‘fatigue’ is complex and means different things to different people, and items that use this term often do not capture the symptoms of PEM among patients.

Most participants with CFS endorsed the presence of fatigue in their lives, but there is much more variability in the duration or onset of fatigue after physical or mental activity. This may show evidence for subtypes of ME, ME/CFS, and CFS that range in the severity of PEM. Some individuals may experience PEM for 24 hours or longer, whereas others may only experience it for one hour. Some individuals experience PEM immediately after mental or physical exertion, but others develop PEM hours after the initial activity of cause. In a study conducted by Jason, Boulton et al. (2010), a sample of participants with CFS was broken into clusters using a five-cluster solution based on a composite score of the onset, frequency, and severity of fatigue. Significant group differences were found for each fatigue dimension (post-exertional, wired, brain fog, energy, and flu-like) on the MFTQ. Evidently, there are differentiable levels of severity for PEM, among other fatigue symptoms. Hence, it would be more effective for self-report items to have scales that contain a wider set of time frames rather than solely ‘24 hours or longer.’

With the aim of developing better self-report items to assess the presence and experience of PEM, careful attention needs to be paid towards subtle differences in wording. It is apparent that some of the existing self-report items based on the current U.S. definition of CFS are too vague. As a result, those with CFS may not be diagnosed and those without CFS could be misdiagnosed with this illness. As in the current sample, since PEM is only one of eight minor symptoms in the Fukuda et al. (1994) criteria, participants diagnosed with CFS may not even endorse PEM as a symptom. This is of importance, as a study conducted by Maes et al. (2012) found that self-reported PEM was significantly related to inflammatory and cell-mediated immune biomarkers. Furthermore, PEM was actually used to make a distinction among ME, CFS, and chronic fatigue; notably, patients with ME showed more severe clinical symptoms and immune abnormalities compared to patients with CFS; whereas, both ME and CFS displayed more severe symptoms and immune disorders than patients with chronic fatigue. Above all, this shows evidence for the usage of biological measures and self-report items to help differentiate ME from chronic fatigue.

Recently, a new case definition for ME has been introduced by the Myalgic Encephalopmyelitis International Consensus Panel (ME-ICC) (2012). Within their primer, PEM is referred to as post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion (PENE). The authors indicate that PENE can be assessed with a two consecutive day exercise test involving expired gas exchange, but as indicated above, cardiopulmonary devices are expensive and not always available in clinic and research settings, so self-report questionnaires will need to be used in most settings to assess this symptom cluster. For the self-report questionnaire that is included in the primer, PENE is characterized by 1) marked, rapid physical or cognitive fatigability in response to exertion, 2) symptoms that worsen with exertion, 3) post-exertional exhaustion that may be immediate or delayed, 4) exhaustion is not relieved by rest, and 5) substantial reduction in pre-illness activity level due to low threshold physical and mental fatigability. There are a number of problems with this level of specification. First, it is unclear whether all five characteristics must be present for PENE to occur. If a person meets all but one characteristic, it is unclear whether they would be counted as having this symptom. For example, in a separate dataset utilized by Jason, Sunnquist, Brown, & Evans (2013), it was found that out of 122 participants who met the Canadian ME criteria (Carruthers, 2011), only 77 participants would have met five differently worded statements that are characteristics of PENE. Therefore, whether all characteristics or just some are required for the ME-ICC case definition of PENE is of considerable importance.

Furthermore, the precise operationalization of each of these characteristics is still ambiguous. For example, the requirements for the onset and duration of PENE are vague and therefore reliability problems might occur. Additionally, physical and mental fatigability is supposed to result in a substantial reduction in activity level that can be mild, moderate, severe, or very severe. However, the meaning of substantial reduction or significantly reduced activity level is not clearly defined. As an example, one characteristic of PENE involves having a “Low threshold of physical and mental fatigability (lack of stamina) results in a substantial (approximately 50%) reduction in pre-illness activity level.” Directions are then provided in the primer indicating that symptom severity must result in a significant reduction in a patient’s premorbid status, which can be rated as mild, moderate or severe. Moderate is defined as an approximate 50% reduction in pre-illness activity level, but there is also an option for mild, which “meets criteria” and involves a significant reduction; but as moderate is defined as a 50% reduction, mild must be less, and this contradicts the prior statement regarding the need to have a 50% reduction. Similar issues arise with the other required symptoms, thus, there will likely be reliability problems with this new case definition.

All in all, different items need to be utilized to address the type of fatigue, form of activity, onset of PEM, duration of PEM, and reductions in functionality as a result of PEM. More importantly, instead of focusing on one question to determine the presence of PEM, perhaps several questions should be used to gauge how symptoms change after mental or physical activity. In a study conducted by Jason et al. (2011), five composite PEM items were confirmed to have the best diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. The following items were part of this composite: Dead, heavy feeling that occurs quickly after starting to exercise; Next day soreness or fatigue after non-strenuous, everyday activities; Mentally tired after the slightest effort; Physically drained or sick after mild activity; and Minimum exercise makes you physically tired. These descriptors highlight that PEM goes beyond general fatigue and may include pain, mood disturbances, and malaise among other symptoms. To better assess PEM, these five items have been included in the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire (DSQ) (Jason, Evans, et al., 2010), so individuals who may be eschewing exercise or excessive activity in order to avoid eliciting PEM would still be recognized under criteria to establish ME, ME/CFS, and CFS. Hence, there would be less of a focus on common fatigue, but more of an emphasis on the usage of reliable items that would reflect the actual debilitating nature of PEM for these individuals.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by NIAID (grant numbers AI 49720 and AI 055735).

References

- Carruthers BM, Jain AK, DeMeirleir KL, Peterson DL, Klimas NG, et al. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Clinical working case definition, diagnostic and treatments protocols. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 2003;11:7–115. doi: 10.1300/J092v11n01_01. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, Klimas NG, Broderick G, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2011;270:327–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1994;121:953–959. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. Available at: http://www.ncf-net.org/patents/pdf/Fukuda_Definition.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudsmit E, Shepherd C, Dancey CP, Howes S. ME: Chronic fatigue syndrome or a distinct clinical entity? Health Psychology Update. 2009;18:26–31. PMID: 19576714. [Google Scholar]

- Hawk C, Jason L, Torres-Harding S. Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Major Depressive Disorder. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;13(3):244–251. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1303_8. PMID: 17078775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde BM. The Nightingale Definition of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (M.E.) The Nightingale Research Foundation; Ottawa, Canada: 2007. Retrieved from http://www.nightingale.ca/documents/Nightingale_ME_Definition_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- International Consensus Panel . Myalgic encephalomyelitis – Adult & Paediatric: International Consensus Primer for Medical Practitioners. Carruthers & van de Sande; Vancouver, BC: 2012. Available at http://www.hetalternatief.org/ICC%20primer%202012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Boulton A, Porter NS, Jessen T, Njoku MG, et al. Classification of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome by types of fatigue. Behavioral Medicine. 2010;36:24–31. doi: 10.1080/08964280903521370. PMID: 20185398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Damrongvachiraphan D, Hunnell J, Bartgis L, Brown A, Evans M, Brown M. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: Case definitions. Autonomic Control of Physiological State and Function. 2012;1:1–14. doi:10.4303/acpsf/K11060. [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Evans M. To PEM or not to PEM? That is the question for case definition. Research1st Blog. 2012 Apr 27; [Web log post]. Retrieved May 31, 2012, from http://www.research1st.com/2012/04/27/pem-case-def/

- Jason LA, Evans M, Brown M, Porter N, Brown A, Hunnell J, Anderson V, Lerch A. Fatigue scales and chronic fatigue syndrome: Issues of sensitivity and specificity. Disability Studies Quarterly. 2011:31. Retrieved from http://www.dsq-sds.org/article/view/1375/1540. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jason LA, Evans M, Porter N, Brown M, Brown A, Hunnell J, et al. The development of a revised Canadian myalgic encephalomyelitis-chronic fatigue syndrome case definition. American Journal of Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 2010;6:120–135. [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Jessen T, Porter N, Boulton A, Njoku MG, Friedberg F. Examining types of fatigue among individuals with ME/CFS. Disability Studies Quarterly. 2009:29. Available at: http://www.dsq-sds.org/article/view/938/1113.

- Jason LA, Jordan KM, Richman JA, Rademaker AW, Huang C, McCready W, et al. A community-based study of prolonged and chronic fatigue. Journal of Health Psychology. 1999;4:9–26. doi: 10.1177/135910539900400103. doi: 10.1177/135910539900400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, King CP, Richman JA, Taylor RR, Torres SR, Song S. US case definition of chronic fatigue syndrome: Diagnostic and theoretical issues. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 1999;5:3–33. doi: 10.1300/J092v05n03_02. [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Muldowney K, Torres-Harding S. The energy envelope theory and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. AAOHN Journal. 2008;56:189–195. doi: 10.3928/08910162-20080501-06. PMID: 18578185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Ropacki MT, Santoro NB, et al. A screening scale for chronic fatigue syndrome: reliability and validity. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 1997;3:39–59. doi: 10.1300/J092v03n01_04. [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Sunnquist M, Brown A, Evans M. Are ME and CFS different Illnesses? 2013 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Komaroff AL, Buchwald D. Symptoms and signs of chronic fatigue syndrome. Review of Infectious Diseases. 1991;13:S8–S11. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.supplement_1.s8. PMID: 2020806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light AR, White AT, Hughen RW, Light KC. Moderate exercise increases expression for sensory, adrenergic, and immune genes in chronic fatigue syndrome patients but not in normal subjects. The Journal of Pain. 2009;10(10):1099–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis I, Pairman J, Spickett G, Newton JL. Clinical characteristics of a novel subgroup of chronic fatigue syndrome patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1111/joim.12022. doi: 10.1111/joim.12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M, Twisk FNM, Johnson C. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME), Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), and Chronic Fatigue (CF) are distinguished accurately: Results of supervised learning techniques applied on clinical and inflammatory data. Psychiatry Research. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.03.031. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay AM. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Postviral Fatigue States: The Saga of Royal Free Disease. 2nd Gower Publishing Corporation; London, England: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves WC, Wagner D, Nisenbaum R, Jones JF, Gurbaxani B, Solomon L, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome – A clinical empirical approach to its definition and study. BMC Medicine. 2005;3(19) doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-3-19. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Report from National Task Force on Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) Post Viral Fatigue Syndrome (PVFS) Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) September 1994 p15.

- Spotila JM. Unraveling Post-exertional Malaise. Research1st Blog. 2010 Aug 7; [Web log post]. Retrieved May 31, 2012, from http://www.research1st.com/2012/05/21/unraveling-pem/

- VanNess JM, Stevens SR, Bateman L, Stiles TL, Snell CR. Postexertional malaise in women with chronic with chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Women’s Health. 2010;19(2):239–244. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1507. PMID: 20095909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]