Abstract

Background

Hospital medicine is a growing field with an increasing demand for additional healthcare providers, especially in the face of an aging population. Reductions in resident duty hours, coupled with a continued deficit of medical school graduates to appropriately meet the demand, require an additional workforce to counter the shortage. A major dilemma of incorporating nonphysician providers such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants (NPPAs) into a hospital medicine practice is their varying academic backgrounds and inpatient care experiences. Medical institutions seeking to add NPPAs to their hospital medicine practice need a structured orientation program and ongoing NPPA educational support.

Methods

This article outlines an NPPA orientation and training program within the Division of Hospital Internal Medicine (HIM) at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN.

Results

In addition to a practical orientation program that other institutions can model and implement, the division of HIM also developed supplemental learning modalities to maintain ongoing NPPA competencies and fill learning gaps, including a formal NPPA hospital medicine continuing medical education (CME) course, an NPPA simulation-based boot camp, and the first hospital-based NPPA grand rounds offering CME credit. Since the NPPA orientation and training program was implemented, NPPAs within the division of HIM have gained a reputation for possessing a strong clinical skill set coupled with a depth of knowledge in hospital medicine.

Conclusion

The NPPA-physician model serves as an alternative care practice, and we believe that with the institution of modalities, including a structured orientation program, didactic support, hands-on learning, and professional growth opportunities, NPPAs are capable of fulfilling the gap created by provider shortages and resident duty hour restrictions. Additionally, the use of NPPAs in hospital medicine allows for patient care continuity that is otherwise missing with resident practice models.

Keywords: Assistant–physician, hospital medicine, hospitalist, inservice training, nurse practitioner

INTRODUCTION

In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) enforced additional resident duty hour restrictions for all accredited programs.1 In 2010, the ACGME further limited resident hours while emphasizing resident supervision customized to the resident's competency level, teaching environment, and transfer of patient care. These additional restrictions stemmed from the Institute of Medicine 2008 article, “Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision and Safety.”2 These changes further limited resident hours, thereby forcing a practice model change to support resident learning and patient safety. Reductions in resident hours coupled with a continued deficit of graduates from medical school to appropriately meet demands require an additional workforce to fulfill the shortage.1,3

Nurse practitioners and physician assistants (NPPAs) are trained allied health professionals who could be capable of fulfilling this workforce gap. Some discussions of this proposal make the assumption that NPPAs do not possess the required education, training, and autonomy needed to care for a heterogeneous hospitalized patient population.4,5 Parekh and Roy suggested that NPPAs would be more successful in protocol-driven settings or focus shops, such as specialty inpatient areas (ie, cardiology or oncology) with less patient complexity.6 We recognized that new resident duty hour restrictions created the opportunity for an alternative practice model utilizing NPPAs in hospital medicine. Therefore, the Division of Hospital Internal Medicine (HIM) at the Mayo Clinic developed an orientation program structured according to the core competencies proposed by the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) in 2006.7,8 The program was designed with the goal of directing all newly hired NPPAs, regardless of their backgrounds and experience levels, through a standardized orientation and training program. Since instituting the training program in 2006, 37 NPPAs have completed orientation, thereby expanding the Division of HIM from 12 NPPAs in 2006 to more than 36 in 2013.

The expectation for NPPAs within HIM is to provide 24-hour/7-day-per-week direct patient care. From 7:00 am to 7:00 pm, an NPPA in conjunction with a hospitalist physician oversees the care of 12-14 patients and shares equal responsibility for dismissals, service transfers, day-to-day complex care plans, and daily admissions. NPPAs cross-cover patient care between 7:00 pm and 7:00 am. NPPAs oversee the nighttime care of 30-35 patients.

This article outlines an effective, well-executed postgraduate NPPA orientation and training program in hospital medicine at the Mayo Clinic. To maintain ongoing NPPA competencies and educational support, we also developed unique supplemental learning modalities, including a formal NPPA hospital medicine continuing medical education (CME) course, an NPPA simulation-based boot camp, preceptorships, and the first hospital-based NPPA grand rounds. If implemented singly, these modalities would be ineffective, but as a whole, we have shown them to be an effective tool in training NPPAs for the rigors of hospital medicine.

NPPA HOSPITALIST ORIENTATION PROGRAM

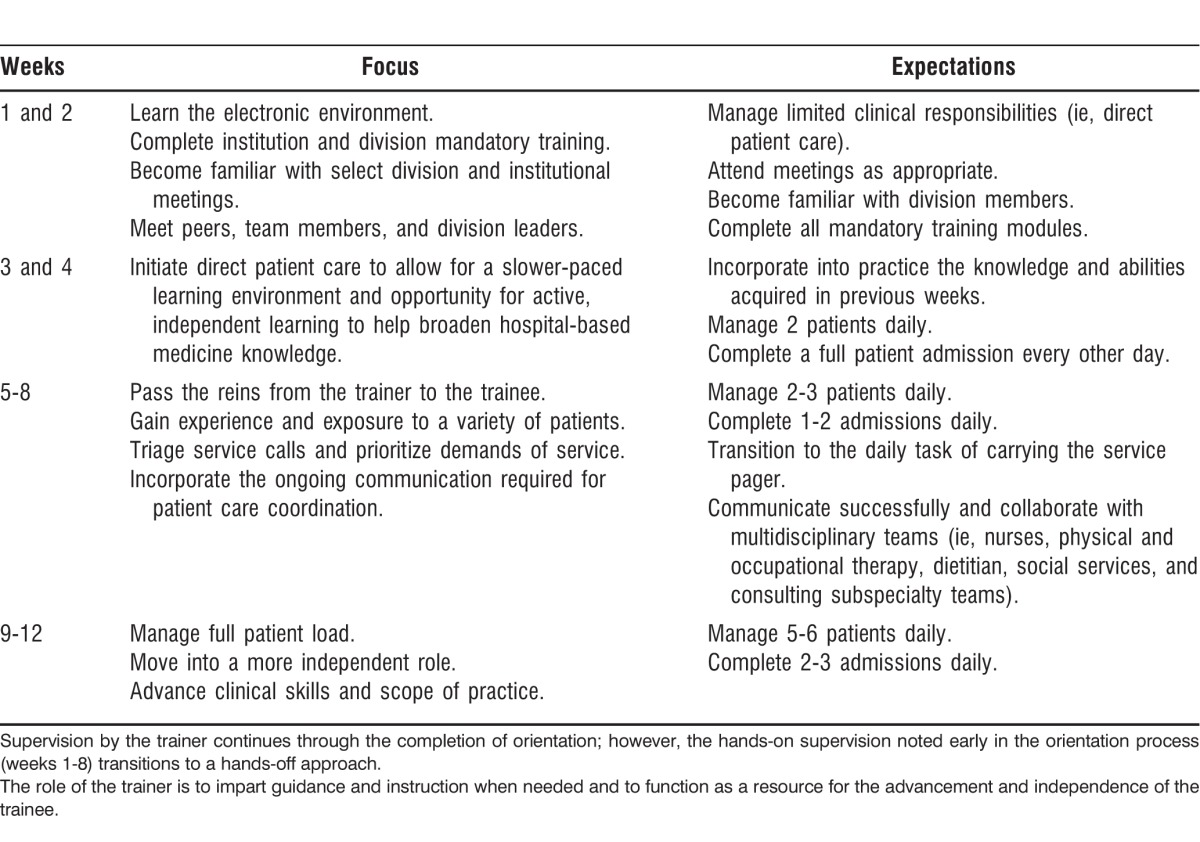

The orientation program takes a structured approach to training while incorporating modification flexibility for newly hired NPPAs. The duration of orientation ranges from 6-12 weeks and focuses on patient care, clinical duties, systems-based learning tools, ongoing needs assessment, and clinical curriculum. The orientation program is the foundation of the clinical skills and knowledge necessary to function as a hospital medicine NPPA who cares for a heterogeneous patient population, including specialty services such as cardiac telemetry, geriatrics, hematology, oncology, perioperative medicine consultation, and general medicine.

The orientation program allows for a graduated stepwise approach, starting with systems-based learning (electronic environment) and progressing to the clinical curriculum necessary to provide direct patient care. As the orientee becomes acquainted with the electronic environment early in orientation, training transitions to a focus on strengthening patient care skills, as well as recognizing systems-based nuances. The 2-part, electronic, standardized orientation and training tool ensures a comprehensive and consistent module specific to hospital medicine. The content is based on a needs assessment derived from the SHM core competencies,7,8 feedback from physicians and NPPAs, and school curricula. The tool provides access to websites, policies and procedures, and clinical resources to be utilized by the orientee during training.

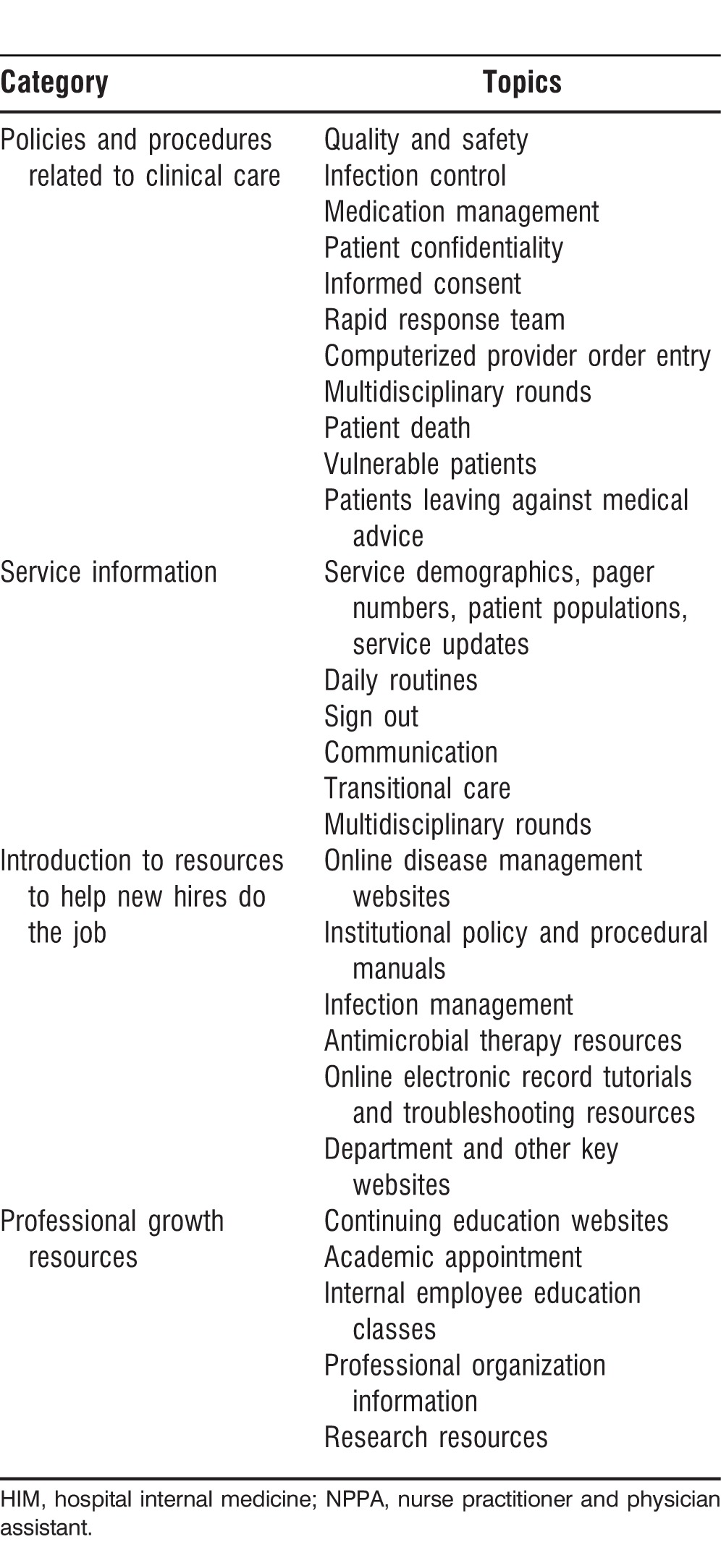

Part 1 of the electronic tool (Table 1) focuses on systems-based learning of departmental and institutional policies and procedures, service model information, and resources for professional growth and clinical care. Each orientee is required to become familiar with these online resources during weeks 1 and 2 of orientation.

Table 1.

Topics Covered in Part 1 of the NPPA Division of HIM Orientation

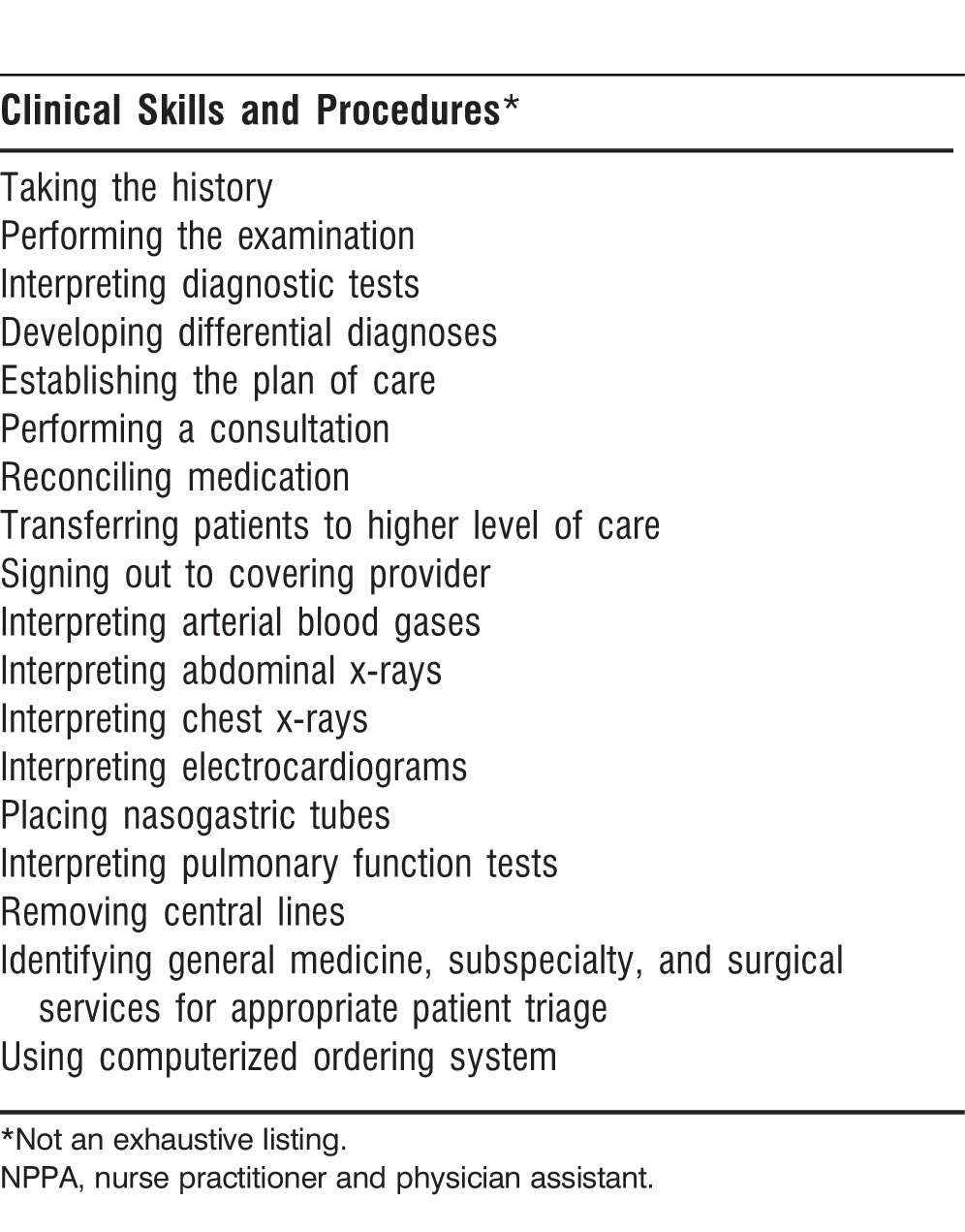

The second part of the electronic tool, structured in accordance with the SHM's core competencies continuum, specifically focuses on clinical skills and procedures (Table 2). This section serves as the needs assessment and as the clinical curriculum documentation used to accurately assess and identify the abilities and knowledge base of the orientee. This training tool is designed as a formal checklist to categorize both ability and comprehension, progressing from basic understanding to the greater complexity of applying and synthesizing diagnoses. Table 3 outlines the clinical conditions and procedures expected to be reviewed or performed by the orientee prior to the completion of orientation. Competency is granted by the NPPA trainer when the orientee is able to demonstrate topic knowledge and safely perform procedural skills during the orientation program. Formal documentation by the NPPA trainer is provided, along with ongoing face-to-face feedback.

Table 2.

NPPA Needs Assessment

Table 3.

Clinical Conditions and Procedures

In an effort to assess and continually improve the HIM orientation program, the 10 orientees who completed the orientation process between 2010 and 2012 were given a postorientation survey. Survey results suggested that orientees desired daily performance feedback.

Consequently, feedback and evaluation are given throughout the orientation program. Weekly, each orientee receives written and verbal feedback from NPPA trainers regarding strengths and weaknesses, in addition to areas that require improvement prior to progressing to the next step of the orientation process. The NPPA supervisor meets with the orientee at week 6 and at the completion of the orientation program to assess competency. This formal review process encompasses all accumulated written feedback from NPPA trainers and documentation of the completion of the 2-part electronic tool consisting of expected competencies in clinical skills, procedures, and systems-based knowledge. The orientee is then formally granted completion of orientation or given guidance for section-specific remediation, if needed. Upon completion of orientation, each NPPA is required to participate in the NPPA CME course and the simulation-based boot camp within the first year of hire.

NPPA HOSPITALIST CME COURSE

As the demand for NPPAs in hospital medicine continues to grow, so will the need for CME opportunities focused on hospital medicine. In 2009, the Mayo Clinic successfully developed, implemented, and expanded a hospital medicine CME course for NPPAs. The course functions as an additional building block for a firm foundation of knowledge in hospital medicine.

The CME course meets the ongoing need for regular formal didactic education and provides access to current evidence-based medicine. CME credits are required for NPPAs to maintain current medical certification, and, at present, only a handful of CME courses in the United States are specifically directed toward hospitalist NPPAs. We utilized 2 sources to construct a course with lecture topics applicable to the practicing hospitalist NPPA. First, we carefully reviewed the SHM's 2006 core competencies,7,8 paying specific attention to the section on clinical conditions. Second, we conducted an informal survey of practicing NPPAs within the Division of HIM to obtain information about frequently encountered medical conditions, medical ethics, and topics of interest in patient care and safety. Presentation topics are updated annually based on participant evaluations.

In 2013, we expanded the CME course to include a second course, thereby answering the demand for more intensive training and education. The new course includes additional specialty tracks in administration, intensive care, and hospital medicine. Precourses are also offered in the areas of infectious disease, palliative care, and ultrasound training, allowing more focused education and hands-on learning. Additionally, to meet new American Nurses Credentialing Center requirements for NP recertification, a pharmacology credit was added to the 2014 CME courses.

NPPA HOSPITALIST BOOT CAMP

The NPPA simulated boot camp was developed to be a supportive and supplemental modality for newly hired NPPAs in hospital medicine. The 2-day boot camp, expected to be completed within the first year of hire, focuses on the application of medical knowledge, decision-making, problem-solving, and communication skills.

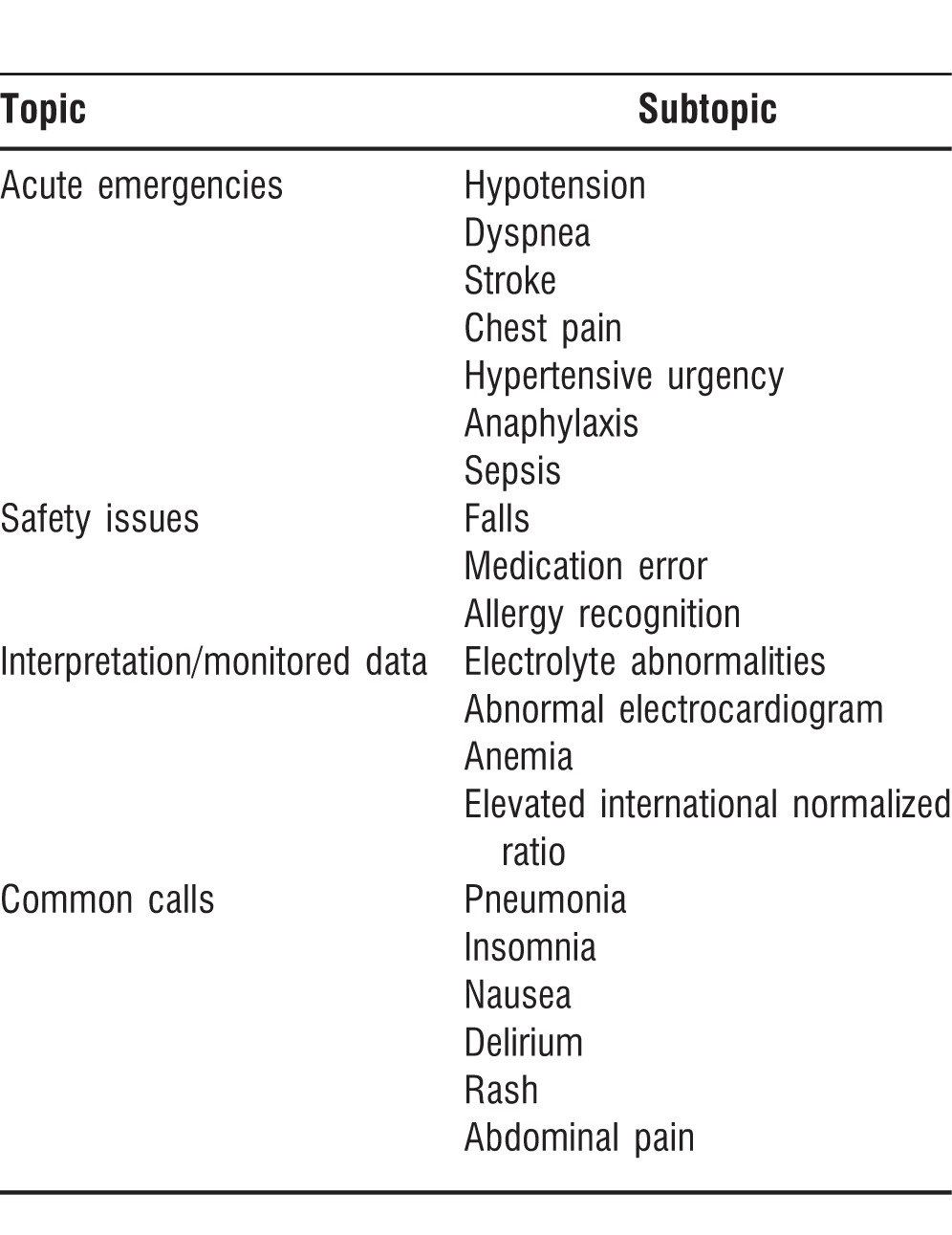

The boot camp was modeled after a week-long simulation-based boot camp for fourth-year medical students transitioning into their intern year.9 Each day is 8 hours long and divided into 20- to 45-minute sections focusing on specific patient care scenarios (Table 4). The scenarios use standardized patients, simulation mannequins, and lecture-based learning. A major focus of the boot camp is symptom management; therefore, after each scenario, a debriefing session is held to establish learning points and highlight topics for discussion.

Table 4.

Sample of Topics Covered in Hospital Medicine Boot Camp

The boot camp structure focuses on the development of a patient care action plan based on a patient's symptomatology rather than focusing on a specific diagnosis-directed treatment modality. In contrast to real-life patient care, the simulation boot camp is a risk-free environment, permitting mistakes without a patient-related adverse outcome.

The objectives of the boot camp are as follows:

-

1.

Identify the severity of a patient-related problem and develop a framework or approach for coordinating a solution based on patient assessment and medical knowledge

-

2.

Demonstrate basic resuscitation skills

-

3.

Illustrate basic knowledge of common safety issues that arise in hospitalized patients and strategies for solving these issues

-

4.

Recognize barriers in self, colleagues, and surroundings that can impact patient care

To assess the impact of the simulated boot camp on an NPPA's acquisition of knowledge and overall decision-making capacity, attendees completed 12-question multiple choice preparticipation and postparticipation tests covering the aforementioned objectives. In addition, a survey utilizing a Likert scale was created to measure the impact on decision-making, problem-solving, and communication skills. Preparticipation and postparticipation test scores showed an improvement in each participant by an average of 15.3% in hospital medicine (n=24). The simulation boot camp became a CME-accredited course because of its success and expansion outside of hospital medicine.

NPPA HOSPITALIST PRECEPTORSHIP

Acting as a preceptor supports the professional growth and educational knowledge of practicing NPPAs in hospital medicine. Educational growth of NPPAs in hospital medicine starts during their initial training as students. Newly hired NPPAs are encouraged to begin serving as a preceptor after completing 1 year of hospital medicine practice within the Division of HIM. This protected time period helps to ensure sufficient training and allows time for the new hire to become comfortable balancing complex patient care plans with job requirements before taking on the added responsibility of preceptorship.

The Division of HIM serves as a rotational site for both NP and PA students. We have partnered with 2 separate training programs for both NP and PA students to complete a hospital medicine rotation. Additionally, students from outside institutions are selected on a case-by-case basis. The HIM rotation site has grown from 2 students per year to more than 20 students annually.

Serving as a primary rotation site for NP and PA students provides HIM staff the opportunity to evaluate and recruit qualified NPPA candidates for hospital medicine. The Division of HIM continues to support the motto “train your own” in an effort to recruit NPPA staff from qualified NP and PA graduate institutions.

NPPA HOSPITALIST GRAND ROUNDS

In an effort to improve upon the lack of recurring accessible educational material directed specifically at the hospital-based NPPA, a grand rounds was instituted at the Mayo Clinic in 2010. NPPA grand rounds was modeled after the Mayo Clinic internal medicine grand rounds and emphasizes patient care, including treatment plans, diagnostic testing, and retrospective learning from morbidity-mortality discussions. Each lecture begins with a vignette presented by an NPPA for the purpose of teaching and expanding on a larger learning topic for discussion. The vignette offers the opportunity for NPPA faculty to develop their presentation skills and encourages academic growth. Attendees include NPPAs in hospital medicine, cardiology, infectious disease, general surgery, and surgical subspecialties. The monthly lecture series became an official CME accrediting event in 2012.

CONCLUSION

Healthcare reform, physician shortages, and resident duty hour restrictions have created the need and opportunity for the incorporation of NPPAs into hospital medicine. The Division of HIM orientation program was created with an emphasis on directing all newly hired NPPAs, regardless of background or experience level, through a standardized orientation and training process. The addition of hands-on learning through boot camp simulation training, didactic support in the form of a CME course and grand rounds, modification flexibility, and professional growth opportunities through preceptorships facilitate the addition of NPPAs to our hospital medicine practice. NPPAs within the Division of HIM at the Mayo Clinic have gained a reputation for possessing a strong clinical skill set coupled with a depth of medical knowledge in hospital medicine. Additionally, the use of NPPAs in hospital medicine allows for patient care continuity that is otherwise missing with resident practice models. The NPPA-physician model serves as an alternative care practice, and we believe that with the institution of modalities, including a structured orientation program, educational didactic support, hands-on learning, and professional growth opportunities, NPPAs are capable of fulfilling the gap created by healthcare provider shortages and resident duty hour restrictions.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the subject matter of this article.

This article meets the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification competencies for Patient Care, Medical Knowledge, and Interpersonal and Communication Skills.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nasca TJ, Day SH, Amis ES, Jr; ACGME. Duty Hour Task Force. The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 8;363(2):e3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1005800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=12508&page=R1. Accessed August 21, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Hospital Association. Teaching hospitals: their impact on patients and the future health care workforce. TrendWatch. 2009 Sep; http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/twsept2009teaching.pdf. Accessed September 16, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Will KK, Budavari AI, Wilkens JA, Mishark K, Hartsell ZC. A hospitalist postgraduate training program for physician assistants. J Hosp Med. 2010 Feb;5(2):94–98. doi: 10.1002/jhm.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roy CL, Liang CL, Lund M, et al. Implementation of a physician assistant/hospitalist service in an academic medical center: impact on efficiency and patient outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2008 Sep;3(5):361–368. doi: 10.1002/jhm.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parekh VI, Roy CL. Nonphysician providers in hospital medicine: not so fast. J Hosp Med. 2010 Feb;5(2):103–106. doi: 10.1002/jhm.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dressler DD, Pistoria MJ, Budnitz TL, McKean SC, Amin AN. Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(Suppl 1):48–56. doi: 10.1002/jhm.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKean SC, Budnitz TL, Dressler DD, Amin AN, Pistoria MJ. How to use the core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(Suppl 1):57–67. doi: 10.1002/jhm.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laack TA, Newman JS, Goyal DG, Torsher LC. A. 1-week simulated internship course helps prepare medical students for transition to residency. Simul Healthc. 2010 Jun;5(3):127–132. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3181cd0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]