Abstract

Background

Primary palliative care consists of the palliative care competencies required of all primary care clinicians. Included in these competencies is the ability to assist patients and their families in establishing appropriate goals of care. Goals of care help patients and their families understand the patient's illness and its trajectory and facilitate medical care decisions consistent with the patient's values and goals. General internists and family medicine physicians in primary care are central to getting patients to articulate their goals of care and to have these documented in the medical record.

Case Report

Here we present the case of a 71-year-old male patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, congestive heart failure, and newly diagnosed Alzheimer dementia to model pertinent end-of-life care communication and discuss practical tips on how to incorporate it into practice.

Conclusion

General internists and family medicine practitioners in primary care are central to eliciting patients' goals of care and achieving optimal end-of-life outcomes for their patients.

Keywords: Advance care planning, advance directives, palliative care, patient care planning, primary care physicians

INTRODUCTION

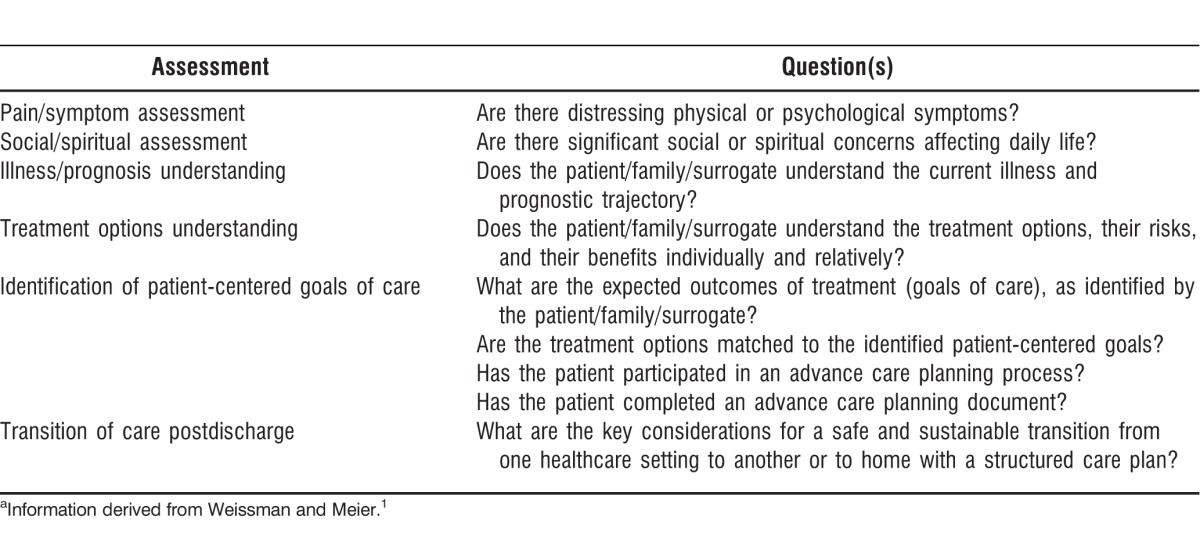

Patient-centered primary care should include basic palliative care, and all primary care clinicians should demonstrate competency in primary palliative medicine skills. Basic components of assessing primary palliative care needs include assessing the patient's physical and nonphysical symptoms, ensuring the patient understands his/her illness and prognosis, and establishing the goals of medical care (Table 1).1 Discussions regarding goals of care help patients and their families understand the nature of the patient's illness and its trajectory and to make decisions on parameters of medical care that are consistent with the patient's values and goals.2 Such discussions should be ongoing and develop over time from continuity of care.3 General internists and family medicine practitioners working in primary care are ideally suited to begin this discussion and to sustain it.4 Primary care focuses on seeing and treating the patient as a whole person, including the psychological and social aspects, with an emphasis on continuity of care.5

Table 1.

Primary Palliative Care Assessment Componentsa

Although barriers in the primary care environment prevent these discussions from occurring as often as is optimal, these barriers can and should be ameliorated. Ethically, goals of care discussions help formulate advance care decisions that are congruent with patient values, ensure respect for patient autonomy,6,7 increase quality of life, and decrease depression near death.8,9 Furthermore, advance care discussions improve patient satisfaction with his/her primary care visit.10 The value of goals articulated while relaxed and thoughtful in consultation with family members, as well as while conscious and competent, is probably immeasurable in the quality of care given.

In the following case report, we model pertinent end-of-life care communication and discuss practical tips to incorporate goals of care and advance care planning into a primary care practice. Barriers to implementation are discussed, as well as evidence-based limitations and future direction.

CASE REPORT

A 71-year-old male patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder on a 40-pack/year smoking history and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III congestive heart failure presents with his daughter who is concerned about his memory loss, increasing shortness of breath, and fatigue. She states that she has noticed her father sometimes seems very confused and cannot remember where he is. Five months ago, the manager of a local store called her because her father was found confused, wandering the parking lot. At the time, she discounted the incident, but she is now increasingly worried about it. The patient complains of feeling tired even though he stays in the house most days. The daughter noticed that he has given up watering his plants and gardening, a lifelong passion. He has lived with her, her husband, and their 2 children since her mother died 4 years ago of breast cancer.

Daughter: I am really worried about Dad. He has not been himself lately and it has come about so suddenly.

MD: I sense that this has been difficult for you to witness.

Daughter: Yes. (pause) When Mama was sick, she went downhill so suddenly. It seemed like one day we were out having lunch together, then the next week she was in the hospital, and a day later she was gone. Since Dad moved in, he is such a big part of my life, and I don't know if I could handle losing him too like that.

MD: Losing your Mom seems to have been very hard on you, and I see it's now hard to imagine life without your father. I can see how close you are to him.

Patient: Doc, are you worried about me like Catherine here?

MD: Catherine seems very worried about you, and I am too. It seems like you may have some problems remembering things, feeling short of breath, and feeling tired.

Patient: I have.

MD: When was the last time you saw your cardiologist and your pulmonologist?

When the patient's daughter expressed feelings of worry, the simple reflective statement by the physician acknowledged her emotions and invited her to elaborate, uncovering what seemed to be anticipatory grief complicated by possibly unresolved issues from her mother's death. Although the evidence base is not robust, data suggest that patient and caregiver distress are concordant. Attending to the distress of the caregiver may alleviate the distress of the patient.11 A practical approach is to mention to the daughter that she seems to be having difficulty with her father's decline and that her mother's death seems to have been a traumatic loss. Patients with terminal chronic illnesses rate emotional support as the skill they most prize in physicians.12 An important step in being emotionally supportive is acknowledging emotion, as was done with the patient's daughter. Emotional support will increase in importance to the patient and his family as he nears death.

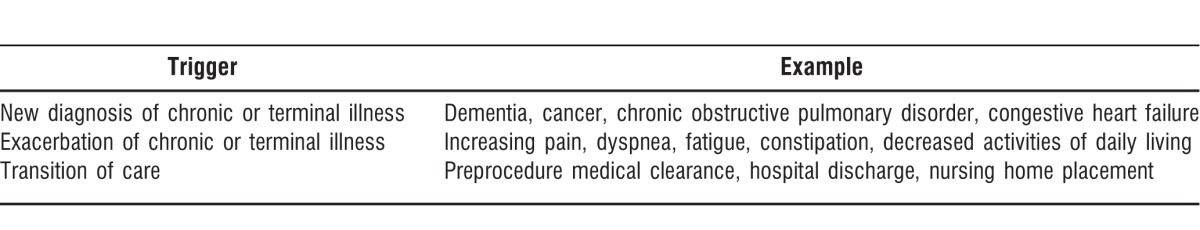

After the specialist visits, a follow-up appointment should be made to focus on reviewing and synthesizing their opinions and to establish the patient's goals of care. Goals of care discussions should ideally occur whenever a new diagnosis of chronic or terminal illness is made, when an exacerbation of a chronic illness occurs, or when a transition of care such as discharge from hospital occurs (Table 2).3,13 Extended time of up to 60 minutes should be reserved for this visit to allow a comprehensive discussion to take place. Time-based billing for counseling and care coordination should be considered, provided that face-to-face time comprises more than 50% of the total time.4,14 Documentation should include the patient's stated values and beliefs, the patient's preferences for care, and the patient's personal goals of care, including a code status discussion and a copy of any advance directives.

Table 2.

Triggers for Initiating or Revisiting a Goals of Care Discussion in an Outpatient Visit

Returning to our case study, 2 weeks later the patient and his daughter returned for his follow-up visit. They had appointments with his cardiologist, pulmonologist, and behavioral neurologist to assess his memory loss. The cardiologist found progressive diastolic dysfunction. The patient's symptoms were now NYHA class IV. The pulmonologist found a PaCO2 of 40 with normal PaO2 at rest and an FEV1 48% of predicted. Pharmacologic therapy was maximized. The neurologist diagnosed the patient with Alzheimer disease with the possibility of vascular dementia.

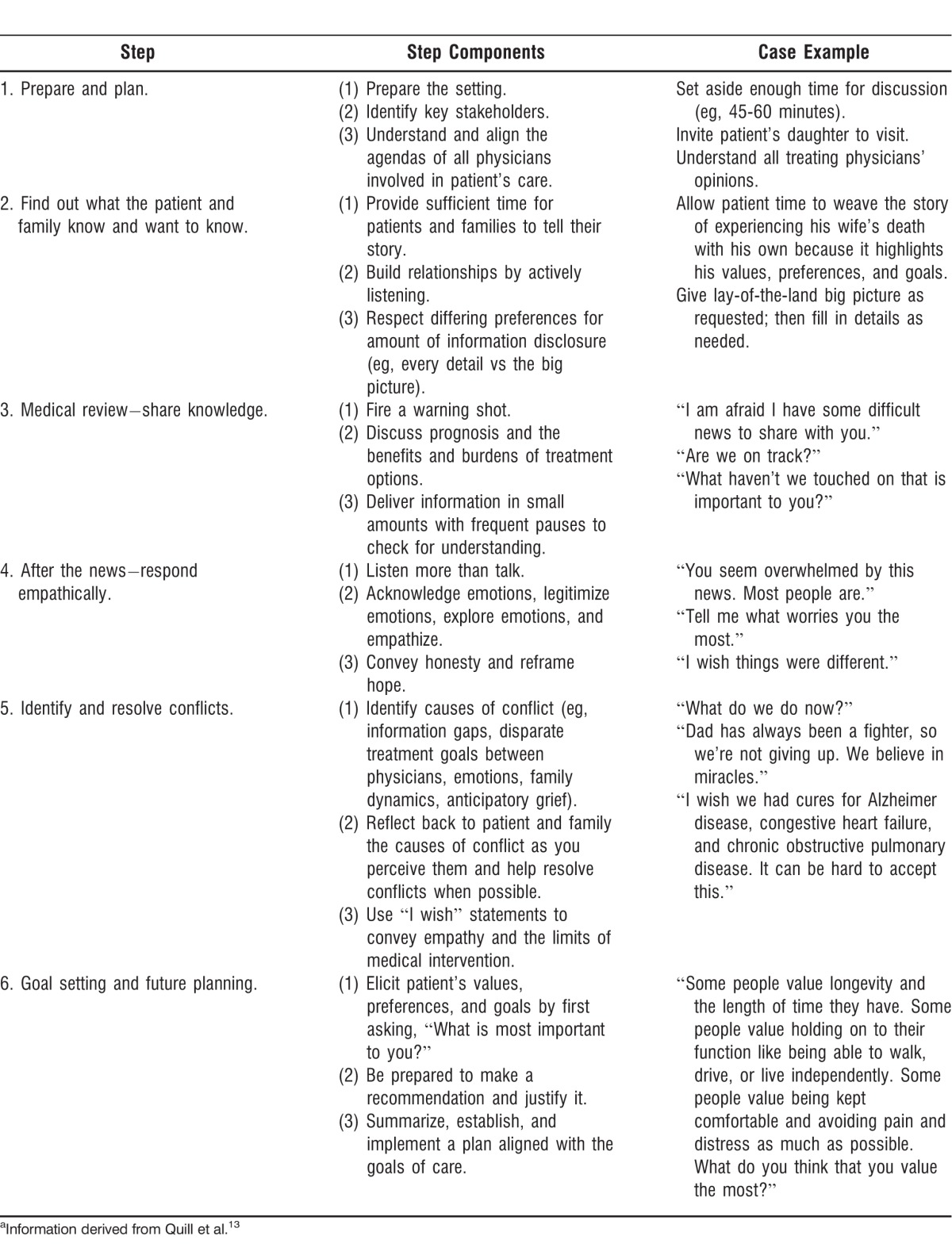

In approaching the follow-up patient visit, it is useful to follow the 6-step approach to establish the goals of care (Table 3).13 The first step is preparing for the visit by ensuring that enough time has been reserved for the discussion. Understand the medical situation (ie, the big picture) and, preferably, communicate with each physician actively involved in the patient's care. It is important to have the key stakeholders, including the patient and his/her caregivers, present. During the visit, first ask what the patient and the patient's family understand about the illness and what and how much information they want to be told. After sharing the pertinent information, allow adequate time for them to process the information and to respond empathically. If conflicts arise, identify them, resolve them if possible, and be prepared to make recommendations. If the patient or family members manifest grief, recognize that it may take time to resolve. Using “I wish” statements at this time may be useful to convey the limits of medical intervention in an empathic manner.

Table 3.

Six-Step Approach to Setting Goals of Carea

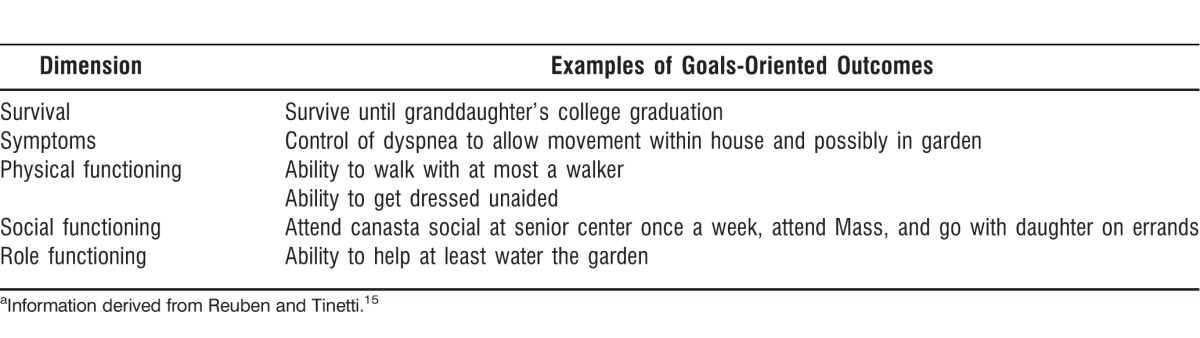

For setting goals of care, align the patient's values and preferences with the medical team's goals. A goals-oriented outcome matrix can be used to set appropriate goals of care (Table 4).15 This type of approach simplifies decision-making for patients with multiple comorbidities and decouples the idea that a symptom is tied to only one condition when instead it may be because of an interaction of disease processes. Additionally, this approach allows patients to better prioritize what is important for them because patients generally think in terms of symptoms, which may carry more meaning for them, and not simply in terms of pathophysiology.

Table 4.

Goals-Oriented Patient Care Matrixa

Knowing what patients value permits better alignment of their preferences for medical care depending on whether their preferences appear stable, shallow, or incoherent.16 If their preferences are shallow, encourage them to explain their rationale and guide them to align their preferences with their stated values and beliefs. An example of a shallow preference is the often-heard statement that the patient wants “everything done” or wants the physician to decide. A patient expressing incoherent preferences should raise a red flag to question his/her capacity to make medical decisions or to reexamine the goals of care with the patient. Structured assessment tools like the Aid to Capacity Evaluation may be helpful to determine capacity.17

Discussing patient prognosis can be difficult because many disease-specific models are not designed for individual decision-making.13 Use of the models may be inconvenient for primary care physicians because they usually require specialized test results. They may also not capture the complexity of patients with multiple comorbidities. In the United Kingdom, general practitioners use what is known as the surprise question to determine the initiation of palliative care consultation for all patients.18 The question is, “Would I be surprised if the patient died in the next year?” A negative answer for patients with cancer is associated with a lower likelihood of survival, suggesting that this question may act as a powerful sorting device for prognosis.19 The use of a functional status scale such as the Palliative Performance Scale can help to further refine prognostication within the year. The scale depends on simple observation and questions about ambulation, daily activity, self-care ability, intake, and consciousness.20

Returning to our case, the physician started the conversation by finding out what the patient knew:

MD: I know that you have seen your heart doctor and your lung doctor. You have also seen a neurologist because we have been concerned about your memory.

Patient: Yes, I did. I've been to a lot of doctors.

MD: If you don't mind, can you tell me what the doctors have told you?

Patient: Well, the heart doctor said my heart is bad. The lung doctor said my lungs are bad, but they are just as bad as before. And the neurologist said I might have Alzheimer's.

MD: What do you think about what they said?

Patient: Well … (pause) They said a lot. You know, I know my heart is bad. The pistons in the motor are getting clogged or maybe the transmission is giving out. Time to trade her in. (chuckles) My lungs are my fault for smoking. But my head… I still think I've got something going on up there. I'm still playing cards, I go down and play canasta at the senior center, and I win. And I still know the prayers at Mass and say the rosary. It doesn't seem right. But the doctor is the doctor and he says Alzheimer's, so what do I know?

Daughter: Yes, they had a lot to say. It was quite a lot.

MD: I am hearing that you might be unsure about what was said or a tad confused. Would it help if I tried explaining the situation as far as I was made aware by all of the specialists?

Daughter: Yes.

MD: Alright, how much information do you want to know?

Patient: Just lay it on the table, Doc. Give me the lay of the land.

MD: I am afraid I have some difficult news to share with you.

The physician then disclosed the pertinent medical information, including prognosis estimates. Between disclosing packets of information, the physician paused to allow the information to be processed and left an opening for spontaneous questions. After finishing the medical information disclosure, the physician probed for understanding:

MD: Did that make things clearer?

Patient: Yes.

Daughter: Yes, it's helpful.

MD: Okay, what haven't we touched on that is important to you?

(long pause)

Daughter: What does this all mean? Where do we go from here?

With those questions, the patient's daughter opened the door for the physician to elicit values and preferences and to establish goals of care:

MD: That is a great question. Like with road trips, it depends on where we want to go and how we are going to get there. I find that the best way to determine this is to first determine what you value and what you believe.

Patient: I believe in God and I believe in heaven. When my time has come, my time has come.

Daughter: No, Dad is a fighter. He has always been a fighter. When Dad fights, Dad wins. If he goes down, it's not going to be without a fight.

Patient: (chuckles) I'm no Rocky Balboa.

MD: (smiles) It sounds like your father has always been a fighter, but this time what I hear is that he's not so eager to fight in that way.

Patient: I'm not saying I want to just lay down and die today, but I know everyone has their time.

A family conflict about acceptance of death is noted. As discussed earlier, the patient's daughter in this scenario may benefit from grief therapy, and this option should be offered to her in this visit. In this case, the daughter's distress may have impacted the father's distress. The physician allowed for more expression of values and beliefs before guiding the discussion:

MD: I find that some people value longevity and the length of time they have. Some people value holding on to their function like being able to walk or drive or live independently. Some people value being kept comfortable and avoiding pain and distress as much as possible. What do you think that you value the most?

Patient: I want to stay independent. I want to be as independent as I can.

MD: What I hear is that you most value holding on to your ability to function independently and you value this over longevity or comfort.

Patient: Yes.

MD: Okay, with that in mind, I find it helpful to think of these things as personal goals that you have. For instance, you were saying earlier that you like playing canasta and you regularly attend Mass. Is your ability to continue these activities an important goal for you to stay independent?

Patient: Yes, absolutely. And I like to be able to go with my daughter on errands sometimes. I have problems with all of this because I can't walk as far as I used to. I get winded.

MD: Okay, I hear that being able to walk and not get winded is important to you.

Patient: Yes, and I love my daughter's help, but sometimes I wish I could get dressed without her helping me. I wish I could do simple things like that.

MD: Okay, being able to dress yourself. Is there anything that you wish you could do, or that you do currently, that you feel is part of your role or responsibility in your family?

Patient: I wish I could water the yard. I've always been proud of keeping my yard nice. And I like being out there, when I can make it there.

MD: Alright, watering your yard. What about longevity? Do you have any goals to survive to an important occasion or event?

Patient: Yes, my granddaughter is graduating from college in May. She is the first one in our family to go to college, and I am really proud of her. You know, when she was small, I was the one who taught her the multiplication tables. Now she's gotten beyond that, too smart for me to teach her anything. Now, she's teaching me.

MD: That is very special. So you want to be here in 7 months to see her graduate. This is very important to you.

Patient: Yes, I'd like to be here. If God allows.

From this conversation, the physician learned the patient's personal goals in life and what he values the most in his overall medical care. The patient's medical care should focus on maintaining independent physical and social functioning. Although he values this more than longevity, he wants to see his granddaughter graduate from college. He is also religious and seems to be more comfortable with the idea of death than his daughter. The physician then transitioned to discussing end-of-life goals such as code status:

MD: Now as with hurricane season here in New Orleans, we need to hope for the best but prepare for the worst. Have you thought about what you want done if your heart stops or if you stop breathing?

Daughter: I am sure we would want everything done.

MD: Can you tell me what you mean by everything?

Daughter: The whole thing. CPR, the ICU.

MD: Okay, thank you for helping me understand. Can you elaborate for me what you think we can achieve from CPR and the ICU?

Daughter: We are not going to stand by and let Dad die. We are going to do everything we can for him when that happens.

MD: It can be hard to even think about this, and I sense that you are having a hard time right now.

Daughter: Yes, this is very hard.

MD: I want to let you know that even if CPR is not done, it does not mean that anyone is abandoning your father. In many cases, CPR does not help the person, and if we are able to help him, many people with the illnesses that your father has do not survive to go home from the hospital.

Patient: If my heart stops or I stop breathing, I know it's my time.

MD: What I hear you saying is that if that happens, you want us to allow you to die naturally?

Patient: Yes, to die in peace.

MD: Your father wants us to allow him to die naturally when his heart stops or he stops breathing. Are you okay with that?

Daughter: This is so hard for me (tears welling in her eyes). But if that is what Dad wants, I only want to do what's best for him.

MD: This is very hard. I trust that you will always do what is best for your father.

The physician then introduced the patient and his daughter to the Louisiana Physician Orders for Scope of Treatment (LaPOST) form, a type of advance directive known as physician orders for life-sustaining treatment.21 The LaPOST form requires the physician's signature as well as the patient's signature or that of his/her healthcare representative. The physician checked the box for “DNR/Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (Allow Natural Death)” and recommended limited additional interventions at this time in light of the patient's wish to see his granddaughter graduate from college, while refraining from a full code resuscitation attempt. Limited additional interventions include hospitalization, intravenous fluids, and cardiac monitoring but do not include intubations, advanced airways, and mechanical ventilation. The patient and his daughter both agreed with this plan. In closing, the physician probed for understanding and ensured future planning and continuity of care:

MD: This has been a long and hard but productive conversation.

Patient: It has been good.

MD: Now we know what is important to you, and that knowledge will help us guide your medical care. We will work through this together.

Patient: Good. I'm happy we got to talk.

MD: And I think it would be very good for the two of you to talk more about what we have discussed today. It will help you to understand each other and be there for each other. This is very important.

Daughter: Yes, okay. We will.

MD: I would like to see you and check up on how you are doing next month, if you don't mind. I want to make sure we keep close tabs on you. If you feel like you are getting worse suddenly, don't hesitate to call me, and I will fit you in. Is there anything else we haven't touched on or any questions or comments you have?

Daughter: Is there anything I can read to help me understand what is ahead?

MD: Do you mean you want something specific to your father's situation or something in general about what is involved at the end of life?

Daughter: Something in general.

MD: Sure, do you have access to the internet?

Daughter: Yes, at home.

MD: Great. Nowadays there is a website for everything, and that includes this. The Regents of the University of California have a website called PREPARE about planning for end-of-life issues. The address is www.prepareforyourcare.org.22

DISCUSSION

In the outpatient setting, 2 major barriers to implementing goals of care discussions are a lack of physician expertise and a lack of time.23 Perhaps the most important palliative care skill for primary care physicians to master is empathic communication when conducting goals of care discussions. We believe that all primary care physicians can develop competency and can improve their ability to conduct such discussions through self-reflection and training. Clinicians may find it useful to schedule longer follow-up appointments for goals of care discussions following the diagnosis of any terminal or chronic illness, before or after any transition of care for procedures, upon hospital discharge, or on patient transfer to a nursing home.

Demographic differences may result in additional barriers that physicians should recognize. Men and African American or Hispanic patients are less likely to have advance directives.24,25 Care should be taken in exploring their goals and in encouraging their articulation. Moreover, it is important to recognize that while not a peculiarly American issue, barriers to offering palliative care to patients with terminal illnesses other than cancer exist in our health system.26

CONCLUSION

Primary care clinicians are central to providing competent primary palliative care and to eliciting patient goals of care. Patient-centered care and continuity of care facilitate discussions resulting in the congruence of patient and healthcare provider goals for future care and for improved end-of-life outcomes. The integration of goals of care discussions into the outpatient setting is an important step in optimizing the goals of medical care, particularly near the end of life.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the subject matter of this article.

This article meets the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification competencies for Patient Care, Medical Knowledge, and Interpersonal and Communication Skills.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: a consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med. 2011 Jan;14(1):17–23. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rome RB, Luminais HH, Bourgeois DA, Blais CM. The role of palliative care at the end of life. Ochsner J. 2011 Winter;11(4):348–352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwak J, Allen JY, Haley WE. Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making. In: Dilworth-Anderson P, Palmer MH, editors. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics: Pathways through the Transitions of Care for Older Adults. Vol. 31. New York, NY: Springer;; 2011. pp. 143–165. In. eds. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCormick E, Chai E, Meier DE. Integrating palliative care into primary care. Mt Sinai J Med. 2012 Sep-Oct;79(5):579–585. doi: 10.1002/msj.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donaldson MS, Yordy KD, Lohr KN, Vanselow NA, editors. Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1996. eds. Committee on the Future of Primary Care, Institute of Medicine. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK232643/. Accessed September 19, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berlinger N, Jennings B, Wolf SM. The Hastings Center Guidelines for Decisions on Life-sustaining Treatment and Care near the End of Life. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press;; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Field MJ, Cassel CK. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1997. Committee on Care at the End of Life, Institute of Medicine. http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=5801. Accessed September 19, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Mar 1;28(7):1203–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 19;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tierney WM, Dexter PR, Gramelspacher GP, Perkins AJ, Zhou XH, Wolinsky FD. The effect of discussions about advance directives on patients' satisfaction with primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Jan;16(1):32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabkin JG, Wagner GJ, Del Bene M. Resilience and distress among amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients and caregivers. Psychosom Med. 2000 Mar-Apr;62(2):271–279. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200003000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Understanding physicians' skills at providing end-of-life care: perspectives of patients, families, and health care workers. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Jan;16(1):41–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00333.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quill TE, Holloway RG, Shah MS, Caprio TV, Olden AM, Storey P., Jr . Primer of Palliative Care. 5th ed. Glenview, IL: American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine;; 2010. Goal setting, prognosticating, and self-care; pp. 109–138. In. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sophocles A. Time is of the essence: coding on the basis of time for physician services. Fam Pract Manag. 2003 Jun;10(6):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reuben DB, Tinetti ME. Goal-oriented patient care—an alternative health outcomes paradigm. N Engl J Med. 2012 Mar 1;366(9):777–779. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1113631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein RM, Peters E. Beyond information: exploring patients' preferences. JAMA. 2009 Jul 8;302(2):195–197. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blais CM. Bioethics in practice: a quarterly column about medical ethics - assessment of patients' capacity to make medical decisions. Ochsner J. 2012 Summer;12(2):92–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Gold Standards Framework (GSF) Centre Community Interest Company. The Gold Standards Framework website. http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/home. Published 2002. Updated August 22, 2014. Accessed September 19, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S, et al. Prognostic significance of the “surprise” question in cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2010 Jul;13(7):837–840. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau F, Maida V, Downing M, Lesperance M, Karlson N, Kuziemsky C. Use of the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) for end-of-life prognostication in a palliative medicine consultative service. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009 Jun;37(6):965–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Louisiana Health Care Quality Forum (LHCQF) Louisiana Physician Orders for Scope of Treatment (LaPOST) website. http://lhcqf.org/lapost-home. Published 2002. Updated September 18, 2014. Accessed June 9, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sudore R. The PREPARE website. University of California San Francisco; https://www.prepareforyourcare.org. Published 2013. Updated February 21, 2013. Accessed September 19, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winzelberg GS, Hanson LC, Tulsky JA. Beyond autonomy: diversifying end-of-life decision-making approaches to serve patients and families. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005 Jun;53(6):1046–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammes BJ, Rooney BL. Death and end-of-life planning in one Midwestern community. Arch Intern Med. 1998 Feb 23;158(4):383–390. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blackhall LJ, Murphy ST, Frank G, Michel V, Azen S. Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. JAMA. 1995 Sep 13;274(10):820–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell GK, Johnson CE, Thomas K, Murray SA. Palliative care beyond that for cancer in Australia. Med J Aust. 2010 Jul 19;193(2):124–126. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]