Abstract

We review experiments supporting the hypothesis that the vertebrate motor system produces movements by combining a small number of units of motor output. Using a variety of approaches such as microstimulation of the spinal cord, NMDA iontophoresis, and an examination of natural behaviors in intact and deafferented animals we have provided evidence for a modular organization of the spinal cord. A module is a functional unit in the spinal cord that generates a specific motor output by imposing a specific pattern of muscle activation. Such an organization might help to simplify the production of movements by reducing the degrees of freedom that need to be specified.

Keywords: modular organization, spinal cord, muscle synergies, factorization algorithms

Introduction

In the natural world some complex systems are discrete combinatorial systems -- they utilize a finite number of discrete elements to create larger structures. The genetic code, language and perceptual phenomena are examples of systems in which discrete elements and a set of rules can generate a large number of meaningful entities that are quite distinct from those of their elements. A question of considerable importance is whether this fundamental characteristic of language and genetics is also a feature of other biological systems. In particular, whether the activity of the vertebrate motor system, with its impressive capacity to find original motor solutions to an infinite set of ever changing circumstances, results from the combinations of discrete elements.

The ease with which we move hides the complexity inherent in the execution of even the simplest tasks. Even movements we make effortlessly, such as reaching for an object, involve the activation of many thousands of motor units in numerous muscles. Given this large number of degrees of freedom of the motor system we, as well as a number of investigators, have put forward the hypothesis that the CNS handles this large space with a hierarchical architecture based upon the utilization of discrete building blocks whose combinations result in the construction of a variety of different movements (Arbib 1981, Tsetlin 1973). In particular, investigators influenced by the AI perspective on the control of complex systems have argued for a hierarchical decomposition with modules, or building blocks, as the most effective way to select a control signal from a large search space (Russell – Norvig Artificial Intelligence 1995).

In the last few years, my colleagues and I have asked a specific question: are there simple units that can be flexibly combined to accomplish a variety of motor tasks? We have addressed this fundamental and long-standing question in experiments that utilize spinalized frogs (Bizzi et al 1991; Giszter et al 1993), freely moving frogs (d’Avella et al.,2003) and rats (Tresch and Bizzi 1999). With an array of approaches such as microstimulation of the spinal cord, NMDA iontophoresis, and an examination of natural behaviors in intact and deafferented animals we have provided evidence for a modular organization of the frog’s and rat’s spinal cord. A “module” is a functional unit in the spinal cord that generates a specific motor output by imposing a specific pattern of muscle activation. Such patterns, in which a group of muscles are activated in a fixed balance, have previously been considered as muscle synergies”. Other investigators have generated corroborative evidence in cats (Lemay et al, 2001; Ting and Macpherson, 2005; Krouchev et al 2006). A clear-cut example of a recombination of synergies is from locomotion with the different limb CPGs. Each CPG can operate independently, but the four limb CPG can also be combined in different patterns as in a walk, a trot or a gallop (Grillner 1981, Handbook chapter). Based on extensive indirect evidence, Grillner suggested that each limb CPG can be further subdivided into unit CPGs controlling synergist muscles acting at each joint. (Grillner 1981, 1985). It has also been proposed that these different unit CPGs – synergies can be the independent target for the supraspinal commands used to design different volitional movements involving a limited set of joints (Grillner 1985 Grillner 2006).

The output of a module can be characterized as a force-field. A force-field is a mapping that associates each position of the frog’s hindlimb with a corresponding force generated by the neuromuscular system. Force-fields have been measured by placing the frog’s ankle in different locations in the leg’s workspace and recording at each location the response to microstimulation of the same site in the spinal cord. The majority of force fields generated by stimulation of different areas of the lumbar gray were found to converge toward an equilibrium point. In addition, the force fields could be grouped into a few classes. (Bizzi et al, 1991; Giszter, et al 1993).

Our results have shown that not only the electrical, but also chemical stimulation (NMDA) of the premotor neuronal circuitry of the spinal cord imposes a specific balance of muscle activation leading to a convergent force field (CFF). In addition, in a series of control experiments we have shown that this pattern of forces is not the result of current spread or random activation of the motor neurons. Neither can it result from activating the fibers of passage of the descending fibers and those of the sensory systems. On the basis of these results, (Giszter et al, 1993 and Saltiel et al 2001) we have concluded that distinct interneuronal networks of the spinal cord must be the source of specific types of CFFs..

Another observation derived from microstimulation of the frog’s and the rat’s spinal cord is that the fields induced by the focal activation of the cord follow the principle of vector summation. Bizzi et al. (1991), Mussa-Ivaldi et al. (1994), and more recently, Lemay et al. (2001) have shown that the simultaneous stimulation of two sites, each generating a different force field, results in the vector sum of the two fields in most instances. When the pattern of forces recorded at the ankle following co-stimulation were compared with those computed by summation of the two individual fields, Mussa-Ivaldi et al (1994) found that the “co-stimulation fields” and the “summation fields” were equivalent in more than 87% of cases. Similar results have been obtained by Tresch and Bizzi, (1999) by stimulating the spinal cord of the rat. Recently, Kargo and Giszter, (2000) showed that force field summation underlies the control of limb trajectories in the frog.

Vector summation of force fields implies that the complex non-linearities that characterize the interactions both among neurons and between neurons and muscles are in some way eliminated. More importantly, this result has lead to a novel hypothesis for explaining movement and posture based on combinations of few modules. These modules may be viewed as representing an elementary alphabet from which, through superimposition, a vast number of actions could be fashioned by impulses conveyed by supraspinal pathways, and/or by the reflex pathways. Through computational analysis, Mussa-Ivaldi & Giszter, (1992) and Mussa-Ivaldi, (1997) verified that this view of generation of movement and posture has the competence for controlling a wide repertoire of movements.

Recently, our laboratory has developed a novel method to identify muscle synergies with help of a computational analysis. This approach was first used by Tresch et al (1999) who described the muscle activation patterns evoked from cutaneous stimulation of the hind limb in spinalized frogs.

Tresch et al. (1999) showed that the motor response evoked from cutaneous stimulation of a particular site on the hindlimb resulted from the weighted combination of a few muscle synergies. By changing the relative weighting of each of the synergies depending on the site of cutaneous stimulation, the nervous system could produce a range of different motor responses.

Also of particular interest is the fact that Tresch et al. (1999) compared the distinct muscle synergies derived from cutaneous stimulation with the patterns of muscle activation evoked by microstimulation of the frog spinal cord (the force fields identified by our previous research). Tresch found that the two sets of EMG responses were very similar to one another. In addition, the synergies evoked by NMDA were found by (Saltiel et al 2001) to be qualitatively similar to those described by Tresch.

The construction of movements with muscle synergies

For a long time, investigators have recognized that one of the basic questions in motor performance is whether the cortical motor areas control individual muscles or make use of synergistically linked group of muscles. (Lee,1984; Macpherson, J.M.1991). Given that no natural movement involves just one muscle, any motor act, a fortiori, involves a “muscle synergy”, the question then has been whether the synergistic activation of muscles derives from a fixed common neural drive or is merely a phenomenological event of a given motor coordination.

Despite the history of this issue, the vast literature on this question indicates little consensus either for fixed synergies or for individual control of muscles. For instance, Howard et al. (1986) showed that the synergists around the elbow joint do not co-vary under all conditions because the relationship between the muscles varies with the nature of the task. Buchanan et al. (1986) reached the same conclusion in experiments in which subjects moved their arm in different directions. Along similar lines (Hepp-Reymond et al. 1996) in an investigation of isometric precision grip in the monkey found that muscles that appeared correlated at one level of force were not necessarily so at higher force levels. This observation was interpreted as a lack of amplitude scaling and not in keeping with idea of synergies.

The studies mentioned above as well as many others (see Macpherson, 1991) are not in agreement with other reports claiming that human postural responses are indeed organized synergistically (Nashner (1977), Crenna et al. (1987), Mc Collum et al.(1984) Nashner and McCollum (1985)). However, the synergies described by these investigators were present only in restricted set of movements such as postural sways in the sagittal plane, and further examination by others of more complex postural responses showed different and richer combinations of muscle activations.

Even though most investigators doubt the existence of fixed synergies, they are nevertheless reluctant to accept the idea that a separate control signal must be computed for each muscle to achieve the appropriate movement. Various, alternative mechanisms have been suggested such as hierarchical control (Saltzman 1979, Bullock and Grossberg 1988, and Das and McCollum, 1988). According to these investigators there is a hierarchy of parameters or strategies that are controlled in any motor act. Once the strategy is chosen a coordinated pattern of muscle activity is selected, but the muscle groupings are not considered to be fixed -- they are formed and reformed each time.

Summing up, there is little doubt that the issue of muscle synergies has remained unsettled. However, there is a reason for this predicament --- the approaches that have been used to investigate this issue have been based on correlation methods, which in this case are less than ideal for settling the muscle synergy question. The recent introduction of novel computational procedures has opened a different way to approach the issue of synergies. In 1999, Tresch and collaborators developed a variety of essentially similar computational methods to extract synergies from the recorded muscle activations. In general, these methods try to decompose the observed muscle patterns as simultaneous combinations of a number of synergies. This decomposition is obtained using iterative algorithms that are initialized with a set of arbitrary synergies. The non-negative weighting coefficients of these arbitrary synergies that best predict each response are then found. The synergies are then updated by minimizing the error between the observed response and the predicted response. This process is then iterated until the algorithm converges on a particular set of synergies. The algorithm extracts both a set of synergies and the weighting coefficients of each synergy used to reconstruct the EMG responses.

To explain why the computational method provides a different perspective from the one afforded by the correlation method, let us assume that a given muscle belongs to more than one synergy. According to the correlation method, two muscles, say, X and Y, are considered part of a same synergy, A, if they both scale in amplitude when more force output is required during a task. A potential problem with this approach may surface if, for example, muscle Y is also found in synergy, B. Then, when synergies A and B are recruited together in different contexts, the amplitude scaling for X and Y might be different, and then the false conclusion could be reached that no synergy between X and Y exist.

Note that there are a number of factorization algorithms to assess the hypothesis that motor behavior might be produced through a combination of a small number of synergies. Tresch et al (2006) have compared different algorithms and found that in general, most of the algorithms used to identify muscle synergies perform comparably. In particular, non-negative matrix factorization, independent component analysis, and factor analysis performed at similar levels to one another. When Tresch et al (2006) applied these methods to experimentally obtained data set, the best performing algorithms identified synergies very similar to one another. These results suggest that the muscle synergies found by a particular algorithm are not an artifact of that algorithm, but reflect basic aspects of muscle activation.

Finally, the synergistic link in a group of muscles might be more general than the specific amplitude ratios among the instantaneous activations of the muscles expressed by the components extracted by factorization algorithms such FA, ICA, and NMF. The coordination among muscle recruitments expressed by a synergy might also be extended to the temporal domain. This idea has led to the introduction of a novel factorization algorithm (d’Avella & Tresch, 2002) to extract time-varying synergies, i.e. the coordinated activations of groups of muscles with specific time-varying profiles. Time-varying synergies can naturally capture specific asynchronous activations of groups of muscles and provide a parsimonious model for the generation of muscle patterns. In fact, once the synergies are specified, one amplitude scaling coefficient and one time delay coefficient per synergies are sufficient for generating a muscle pattern. In contrast, the entire time-course of the weighting coefficients is required with synchronous synergies.

Muscle synergies extracted from intact, freely moving frogs

The above experiments suggest that motor behavior might be produced through the flexible combination of muscle synergies. However, to more directly assess the utility of this hypothesis, it is necessary to test its applicability to natural behaviors. In recent experiments we have evaluated this issue by examining several motor behaviors in intact, freely moving frogs. We recorded simultaneously from a large number of hindlimb muscles during locomotion, swimming, jumping and defensive reflexes (d’Avella, Saltiel & Bizzi, 2003; d’Avella & Bizzi 2005).

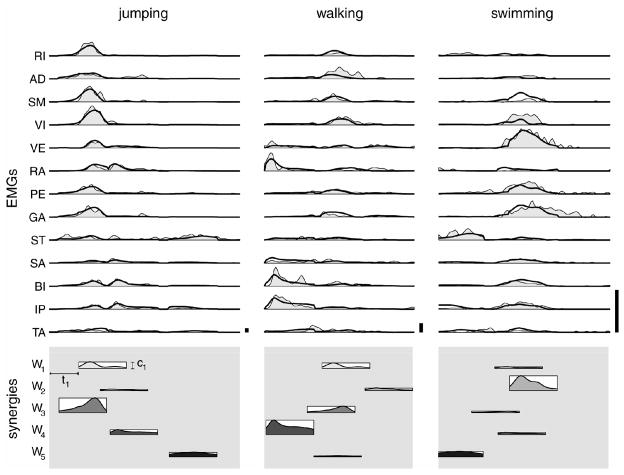

We extracted synergies from the pooled, rectified and integrated EMGs records of thirteen leg muscles in 3 intact frogs during swimming, jumping, and walking using a computational analysis. An iterative algorithm was used to decompose the muscle patterns as combination of time-varying muscle synergies independently scaled in amplitude and shifted in time. This iterative algorithm finds a set of muscle synergies and, for each muscle pattern, the amplitude and delay of each synergy that minimize the reconstruction error for the entire dataset.

In fig. 1 we show the five time-varying synergies extracted from all the rectified, low-pass filtered, and integrated (10 ms) EMGs recorded during a total of 2174 jumps, walking cycles, and swimming cycles in 3 frogs. The five extracted synergies include all 13 muscles. The first 3 synergies (W1, W2, and W3) recruit mainly extensors while W4 and W5 recruit mainly flexors. The most active muscles of synergy W1 are the hip extensors rectus internus (RI), adductor magnus (AD), and semimembranosus (SM), the knee extensor vastus internus (VI), and the ankle extensors peroneus (PE) and gastrocnemius (GA). The most active muscles of the synergy W2 are SM, vastus externus (VE), and GA. In W3 RI, SM, and VI are the most active. The flexors dominate synergy W4 with rectus anterior (RA), biceps (BI) and ilio-psoas (IP). Synergy W5 mainly semitendinosus (ST) and IP. Note that some of the muscles are present in more than one synergy--- lack of recognition of this fact has affected the interpretation of amplitude scaling.(Hepp-Reymond et al. 1966)

Figure 1.

Time-varying muscle synergies extracted from jumping, swimming, and walking muscle patterns in three frogs. Each synergy (columns W1 to W5) represents the activation time-course (in color code) of 13 muscles over 30 samples (300 ms total duration) normalized to the maximum sample of each muscle.

(RI = rectus internus, AD = adductor magnus SM = semimembranosus, VI = the knee extensor vastus internus, VE = vastus externus, RA = rectus anterior, PE = the ankle extensors peroneus, GA = gastrocnemius, ST = mainly semitendinosus, SA = semi tendinosus, BI = biceps, IP = ilio-psoas, TA = tibialis anterior).

The R2 for the five synergies extracted from the entire data set was 0.78. Thus a large fraction of the total variation of the data was described by a model that has just 10 parameters (5 amplitude and 5 timing coefficients) once the synergies are determined.

Fig. 2 shows the reconstruction of muscle patterns (rectified, filtered, and integrated EMGs, thin line and shaded area) for a jump, a cycle of walking, and one of swimming as combinations of the five synergies of fig. 1 (thick line). The synergy’s amplitude is shown as the height of the rectangles below the EMGs, and the delay coefficients by their horizontal position. The essential features of the three patterns are well captured by scaling in amplitude and shifting in time the five time-varying synergies. In jumping (first column) two of the three extension synergies are active (W1 and W3) together with the two flexion synergies (W4 and W5). In walking (second column) synergies one, three, and four appear again but their amplitude balance and recruitment order are radically different from jumping ---W4 dominates in amplitude, while W1 and W3 are relatively small, and the timing between W3 and W4 is reversed. Swimming (third column), in contrast, is dominated by W2 and to a lesser extent by W5.

Figure 2.

Examples of reconstruction of EMG patterns as combinations of time-varying muscle synergies. The three columns are examples of a jump, a walking cycle, and a swimming cycle. Upper section (EMGs): the thick line shows the reconstruction of muscle patterns and the shaded area represents the rectified, filtered and integrated EMGs. The lower section (synergies) shows the coefficients of the five synergies as the horizontal position (onset delay, ti) and the height (amplitude, ci) of a rectangle whose width corresponds to the synergy duration. The shaded profile in each rectangle illustrates the averaged time-course of the muscle activation waveforms of the corresponding synergy. Note the different amplitude scaling used in the three columns

The examples illustrated by fig. 2 demonstrate two important points: 1) that the same synergies are found in different behaviors and; 2) that different behaviors may be constructed by combining the same synergies with different timing and amplitude.

Fig. 3 (upper row, a, b, and c) illustrates the coefficient of synergies displayed in Fig. 1. In C note jumps of different amplitude and the amplitude modulation of synergy W1. In the second row, walking over a flat (d) surface is shown. In e, f, and g, walking on a progressively steeper surface is displayed (20%, 30%, and 40 % incline). This figure demonstrates amplitude scaling of the synergies W, W2, W3, and W4. The third row (h and i) demonstrates two examples of swimming at different speeds. In i, the higher speed is reached by adding synergies W and W3 to fortify extension and W4 for flexion.

Figure 3.

Scaling of synergy recruitment in different frog behaviors. Each panel represents the recrutment of the five synergies of fig. 1 to generate either a jump (a, b, and c), or a walking cycle (d to g), or a swimming cycle (h and i).

The examples illustrated in figures 2 and 3 address the important question of whether the synergies extracted by our computational procedure have biological standing. Clearly, a certain number of criteria must be satisfied in order to validate the extracted synergies. Chief among them, is the evidence of amplitude scaling of a given synergy which is illustrated in fig. 3 by the frog’s walk on a progressively inclined surface (e, f, and g) and the jumps in b and c. Along the same lines, deletion of a given synergy (i.e. coefficient equal to zero) like in the example (h) in which W1 is absent during low power swimming makes the same point. Another compelling criterion is the presence of the same synergy, with its own internal temporal structure, in different behaviors as illustrated several times in figures 2 and 3.

In conclusion, the examples shown here indicate that combining muscle synergies is a strategy that the CNS utilizes for the construction of movements in the frog. Recent results from the study of the muscle patterns during reaching in humans (d’Avella et al 2006) suggest that this is a general strategy used by all vertebrates for simplifying the control of limb movements.

Muscle synergies extracted from deafferented frogs

The results described in the previous section suggest that the CNS generates diverse motor outputs by combining a small number of muscle synergies. But the precise role of sensory feedback in organizing and activating these synergies has remained an open question. It is possible that each synergy is completely specified by spinal and/or supraspinal networks. Alternatively, synergies might arise as emergent properties of the entire neuronal network comprising both central circuits and feedback loops.

We have recently attempted to address the above question by simultaneously recording EMGs from 13 hindlimb muscles of the frog during locomotor behaviors before and after ipsilateral deafferentation, the procedure of removing sensory inflow into the CNS by severing dorsal roots (Cheung et al., 2005). In this study, as an initial assessment of afferent roles in synergy organization, we extracted synchronous muscle synergies from the intact and deafferented data sets. Moreover, to rigorously compare intact and deafferented synergies, we developed a novel NMF-based procedure that searches for synergies by minimizing the reconstruction error for the data set pooling both the intact and deafferented data, and at the same time, indicates whether a synergy is shared between the two data sets, or specific to either of the data sets.

Fig. 4A shows five synchronous synergies extracted from the intact and deafferented data of one frog during jumping. Four of the five synergies (Sh1-Sh4) were synergies shared between the intact and deafferented data sets, and one (Desp), as a deafferented-specific synergy (i.e., it contributes to the reconstruction of only the deafferented data). These synergies together describe the intact and deafferented jumping data with R2 values of 90.6% and 90%, respectively. The fact that in both data sets, a similarly large amount of data variation is captured by these synergies indicates that the finding of shared synergies is not the result of one data set being described better than the other, or of both data sets being described poorly.

Figure 4.

Muscle synergies underlying intact and deafferented locomotor behaviors. A, Synchronous muscle synergies extracted from the pooled intact and deafferented jumping data of one frog. Four of the five synergies (Sh1-Sh4) were found to be shared between the intact and deafferented data sets, and one (Desp), specific to the deafferented data set. The fact that most of the synergies were extracted as shared synergies suggest that, many locomotor synergies are centrally organized. Modified from Cheung et al. (2005). B, C, Reconstructing intact and deafferented jumping EMGs with synergies and their corresponding activation coefficients. The original EMG data (rectified, filtered, and integrated) are shown in black lines, and the time-varying coefficients activating the synchronous synergies are shown below the EMGs. The reconstruction of the motor pattern is superimposed onto the original EMGs. The colors composing the reconstruction match the colors of the coefficients such that the colors reflect the respective contribution of each synergy to the reconstruction at each time point. Modified from Cheung et al. (2005).

To illustrate how the synergies shown in Fig. 4A can be used to reconstruct the EMG data, we show two examples of EMG reconstruction for two jumps recorded before (Fig. 4B) and after (Fig. 4C) deafferentation, respectively. Each jump is divided into three phases – a, b, and c – for ease of inspection. We see that, the EMG patterns of these two jumps are different. In particular, the burst duration of the flexor muscles IP, TA, BI, and SA during phases b and c were prolonged after deafferentation. But these differences are nicely captured by the prolonged activations of synergies Sh3 (light blue) and Sh4 (green), both of which are shared between the intact and deafferented data sets.

The examples in Fig. 4 together demonstrate two important points: 1) Many synergies underlying natural locomotor behaviors are robust neural structures encoded within spinal and/or supraspinal networks. This is suggested by the result that most of the synergies were found to be shared between the intact and deafferented data sets (Fig. 4A). 2) Sensory afferent modulates the activation patterns of a set of centrally organized synergies. This is illustrated in Fig. 4B–C, which show how EMG changes observed after deafferentation can be characterized as alterations in the activation pattern of shared synergies.

In conclusion, in the above sections we have provided both experimental and analytical results suggesting that linear combinations of a small number of muscle synergies may be a strategy utilized by the CNS to generate diverse motor outputs. Furthermore, most of the synergies used for generating locomotor behaviors are centrally organized, but their activations might be modulated by sensory feedback so that the final motor outputs can be adapted to the external environment.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arbib MA. Perceptual structures and distributed motor control. In: Brooks VB, editor. Handbook of physiology, Section 2: the nervous system, Vol. II, Motor Control, Part 1. American Physiological Society; 1981. pp. 1449–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Bizzi E, Mussa-Ivaldi FA, Giszter SF. Computations underlying the execution of movement: a biological perspective. Science. 1991;253:287–291. doi: 10.1126/science.1857964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TS, Almdale DPJ, Lewis JL, Rymer WZ. Characteristics of synergic relations during isometric contractions of human elbow muscles. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56:1225–1241. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.5.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock D, Grosssberg S. Neural dynamics of planned arm movements: emergent invariants and speed-accuracy properties during trajectory formation. Psychol Rev. 1988;95:46–90. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.95.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung VC, d’Avella A, Tresch MC, Bizzi E. Central and sensory contributions to the activation and organization of muscle synergies during natural motor behaviors. J Neurosci. 2005;25(27):6419–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4904-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenna P, Frigo C, Massion J, Pedotti A. Forward and backward axial synergies in man. Exp Brain Res. 1987;65:538–548. doi: 10.1007/BF00235977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P, McCollum G. Invariant structure in locomotion. Neuroscience. 1988;25:1023–1034. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Avella A, Bizzi E. Low dimensionality of supraspinally induced force fields. PNAS. 1998;95:7711–7714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Avella A, Tresch MC. Modularity in the motor system: decomposition of muscle patterns as combinations of time-varying synergies. In: Dietterich TG, Becker S, Ghahramani Z, editors. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 14. MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- d’Avella A, Saltiel P, Bizzi E. Combinations of muscle synergies in the construction of a natural motor behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(3):300–8. doi: 10.1038/nn1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Avella A, Bizzi E. Shared and specific muscle synergies in natural motor behaviors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(8):3076–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500199102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Avella A, Portone A, Fernandez L, Lacquaniti F. Control of fast-reaching movements by muscle synergy combinations. J Neurosci. 2006;26(30):7791–810. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0830-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giszter SF, Mussa-Ivaldi FA, Bizzi E. Convergent force fields organized in the frog’s spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1993;13:467–491. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00467.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S. Control of locomotion in bipeds, tetrapods, and fish. In: Brooks VB, editor. Handbook of Physiology. Vol. 2. American hysiological Society; Bethesda, MD: 1981. pp. 1179–1236. Section I. [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S. Neurobiological bases of rhythmic motor acts in vertebrates. Science. 1985;228:143–149. doi: 10.1126/science.3975635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S, Zangger P. On the central generation of locomotion in the low spinal cat. Exp Brain Res. 1979;34:241–261. doi: 10.1007/BF00235671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepp-Reymond MC, Diener R. Neural coding of force and rate of force change in the precentral finger region of the monkey. Exp Brain Res (supp) 1983;7:315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Howard JD, Hoit JD, Enoka RM, Hasan Z. Relative activation of 2 human elbow flexors under isometric conditions – a cautionary note concerning flexor equivalence. Exp Brain Res. 1986;62:199–202. doi: 10.1007/BF00237416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kargo WJ, Giszter SF. Rapid correction of aimed movements by summation of force-field primitives. J Neuorosci. 2000;20:409–426. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00409.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouchev N, Kalaska JF, Drew T. Sequential activation of muscle synergies during locomotion in the intact cat as revealed by cluster analysis and direct decomposition. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96(4):1991–2010. doi: 10.1152/jn.00241.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WA. Neuromotor Synergies as a Basis for Coordinated Intentional Action. J Motor Behav. 1984;16:135–170. doi: 10.1080/00222895.1984.10735316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemay MA, Galagan JE, Hogan N, Bizzi E. Modulation and Vectorial Summation of the Spinalized Frog’s Hindlimb End-Point Force Produced by Intraspinal Electrical Stimulation of the Cord. IEEE Transactions of Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering. 2001;9(1) doi: 10.1109/7333.918272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson JM. How Flexible Are Muscle Synergies? In: Humphryey DR, Freund HJ, editors. Motor Control: Concepts and Issues. John Wiley & Sons Ltd: 1991. pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- McCollum G, Horak FB, Nashner LM. Parsimony in neural calculations for postural movements. In: Bloedel J, Dichgans J, Precht W, editors. Cerebellar Functions. Berlin: Springer; 1984. pp. 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mussa-Ivaldi F, Giszter S. Vector field approximation: a computational paradigm for motor control and learning. Biol Cybernet. 1992;67:491–500. doi: 10.1007/BF00198756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussa-Ivaldi FA, Giszter SF, Bizzi E. Motor learning through the combination of primitives. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7534–7538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussa-Ivaldi FA. Proc of the 1997 IEEE International Symposium on Computation Intelligence in Robotics and Automation. Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE Computer Society Press; 1997. Nonlinear force fields: a distributed system of control primitives for representing and learning movements; pp. 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Nashner LM. Fixed patterns of rapid postural responses among leg muscles during stance. Exp Brain Res. 1977;30:13–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00237855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashner LM, McCollum G. The organization of human postural movements: a formal basis and experimental synthesis. Beh Brain Sci. 1985;8:135–172. [Google Scholar]

- Russell S, Norvig P. Artificial Intelligence; A Modern Approach. Prentice Hall, N.J.: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Saltiel P, Wyler-Duda K, d’Avella A, Tresch MC, Bizzi E. Muscle Synergies Encoded Within the Spinal Cord: Evidence From Focal Intraspinal NMDA Iontophoresis in the Frog. J of Neurophysiol. 2001;85(2):605–619. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.2.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman E. Levels of sensorimotor representation. J Math Psychol. 1979;20:91–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ting LH, Macpherson JM. A Limited Set of Muscle Synergies for Force Control During a Postural Task. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:609–613. doi: 10.1152/jn.00681.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresch MC, Bizzi E. (a) Responses to spinal microstimulation in the chronically spinalized rat and their relationship to spinal systems activated by low threshold cutaneous stimulation. Exp Brain Res. 1999;129:401–416. doi: 10.1007/s002210050908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresch MC, Saltiel P, Bizzi E. The construction of movement by the spinal cord. Nature Neuroscience. 1999b;2(2):162–167. doi: 10.1038/5721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresch MC, Cheung VCK, d’Avella A. Matrix Factorization Algorithms for the Identification of Muscle Synergies: Evaluation on Simulated and Experimental Data Sets. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:2199–2122. doi: 10.1152/jn.00222.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsetlin ML. Automation Theory and Modeling of Biological Systems. Academic Press; N.Y.: 1973. pp. 160–196. [Google Scholar]