Abstract

BACKGROUND

The prognosis of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) after decitabine failure is not known.

METHODS

Data from 87 patients with MDS (n = 67) and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (n = .20) after failure of decitabine regimens were reviewed.

RESULTS

After a median follow-up of 21 months from decitabine failure, 13 (15%) patients remained alive; the median survival was 4.3 months, and the estimated 12-month survival rate was 28%. The estimated 12-month survival rates were 27%, 33%, and 33%, respectively, for patients with high-risk, intermediate-2-risk, and intermediate-1-risk disease (P = .99) by the International Prognostic Scoring System. The estimated 12-month survival rates were 100%, 54%, 41%, and 18%, respectively, for patients with low-risk, intermediate-1-risk, intermediate-2-risk, and high-risk disease according to The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center risk model (P = .01).

CONCLUSIONS

The outcome of patients after decitabine failure is poor and appears to be predictable after decitabine failure.

Keywords: myelodysplastic syndrome, failure, decitabine, prognosis

Epigenetic therapy with hypomethylating drugs is now the standard of care for patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML).1–4 Therapy with decitabine and 5-azacytidine have resulted in complete response (CR) rates of 7% to 35%, median response durations of 9 to 10 months, and median survivals of 20 to 24 months.1–5 Both agents have received the approval of the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of MDS and CMML.

Prognosis in patients with MDS after decitabine failure is believed to be poor, but to the best of our knowledge, there are no literature data pertaining to their outcome. This is important in relation to patients who might benefit from specific strategies such as allogeneic stem cell transplantation (ASCT) or investigational agents. This report summarizes our institutional experience in patients with MDS and CMML after failure of decitabine therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data from all patients with a diagnosis of MDS and CMML who received decitabine therapy from November 2003 until June 2006 were analyzed. Patients had been treated on decitabine protocols after providing informed consent approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC).3–5 Eligibility criteria included 1) age ≥16 years; 2) a diagnosis of International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) intermediate-risk or high-risk MDS or a diagnosis of CMML; and 3) normal organ function, including creatinine ≤2 mg/dL and bilirubin ≤2 mg/dL. Detailed eligibility criteria were previously reported.3–5 Patients were treated with decitabine at the dose of 20 mg/m2 given intravenously daily for 5 days (n = 70), 10 mg/m2 given intravenously daily for 10 days (n = 6), or 20 mg/m2 given subcutaneously daily for 5 days (n = 11); courses were delivered every 4 weeks. Patients who were taken off study were analyzed for the reason decitabine was discontinued, as well as their characteristics at the time they received decitabine and at the time decitabine was discontinued. All patients (n = 87) included in the study were considered to have failed decitabine due to no response, lost response, and/or progression to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Patients who were considered to have failed due to toxicity were not included in the study. Subsequent therapy was also coded as to whether the patient underwent ASCT or received an investigational agent.

Responses to decitabine and subsequent therapies were coded according to the modified international Working Group Criteria.6 Bone marrow aspirations and biopsies (including cytogenetics if abnormal before therapy) were performed before every course to decide whether to deliver the courses every 4 weeks, until CR or for the first 3 courses (whichever was first), and then every 2 to 3 courses. Blood work was performed concomitantly with the bone marrow aspirations. Patients were categorized for MDS risk at the initiation of decitabine therapy and at the time of failure of decitabine according to the IPSS7 and to the MDACC risk model.8 The latter allows risk assessment of any patient with MDS or CMML, regardless of prior therapy, at different time points in the course of the disease. Adverse prognostic factors in the MDACC risk model are as follows: poor performance, older age, thrombocytopenia, anemia, increased bone marrow blasts, leukocytosis, chromosome 7 or complex (≥3) abnormalities, and prior transfusions. The MDACC risk model divides patients into 4 risk categories: low risk (score 0–4) with a median survival of 54 months and a 3-year survival rate of 63%; intermediate-1 risk (score, 5–6) with the median survival of 25 months and a 3-year survival rate of 34%; intermediate-2 risk (score, 7–8) with a median survival of 14 months and a 3-year survival rate of 16%; and high risk (score, ≥9) with a median survival of 6 months and a 3-year survival rate of 4% (Table 1). Survival probabilities were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Comparison of survivals used the log-rank test.9

Table 1.

The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Scoring Systema

| Prognostic Factor | Points |

|---|---|

| ECOG Performance status ≥2 | 2 |

| Age, y | |

| 60–64 | 1 |

| ≥65 | 2 |

| Platelets, ×109/L | |

| <30 | 3 |

| 30–49 | 2 |

| 50–199 | 1 |

| Hemoglobin, <12 g/dL | 2 |

| Bone marrow blasts, % | |

| 5–10 | 1 |

| 11–29 | 2 |

| WBC, >20 × 109/L | 2 |

| Karyotype: chromosome 7 abnormality or complex ≥3 abnormalities | 3 |

| Prior transfusion, yes | 1 |

ECOG indicates Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; WBC, white blood cell count.

Low risk (score 0–4): the median survival is 54 months and the 3-year survival rate is 63%; intermediate-1 risk (score 5–6): the median survival is 25 months and the 3-year survival rate is 34%; intermediate-2 risk (score 7–8): the median survival is 14 months and the 3-year survival rate is 16%; high risk (score ≥9): the median survival is 6 months and the 3-year survival rate is 4%.

RESULTS

Data from a total of 87 patients with MDS and CMML after failure of decitabine therapy, from 2003 until June 2006, were analyzed. These included 67 patients with MDS and 20 patients with CMML. Twenty-five patients (29%) had secondary MDS. Among 49 patients evaluable for IPSS at the initiation of decitabine therapy, 13 (26%) had high-risk, 23 (48%) had intermediate-2-risk, and 13 (26%) had intermediate-1-risk disease. According to the MDACC risk model, 32 (37%) had high-risk, 31 (36%) had intermediate-2-risk, 17 (19%) had intermediate-1-risk, and 7 (8%) had low-risk disease. Cytogenetics analyses were diploid in 34 patients (39%); 39 patients (45%) had ≥10% bone marrow blasts. Thirty-seven patients (43%) had primary resistance to decitabine, and 50 (57%) developed disease recurrence. The best response to decitabine was CR in 21 patients (24%), partial response in 2 (2%) patients, bone marrow CR in 6 (7%) patients, and hematologic improvement in 21 (24%) patients. The median number of cycles of decitabine administered was 7 (range, 1–20 cycles). The characteristics of the study group are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics (N=87)

| Parameter | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Disease type | |

| MDS | 67 (77) |

| CMML | 20 (23) |

| Secondary MDS | 25 (29) |

| Karyotype | 35 (40) |

| Diploid | 34 (39) |

| Chromosome 7 and/or 5 abnormalities | 31 (36) |

| Other | 22 (25) |

| Bone marrow blasts ≥10% | 39 (45) |

| French-American-British Classification | |

| RA | 4 (5) |

| RARS | 3 (3) |

| RAEB | 55 (63) |

| RAEBT | 5 (6) |

| CMML | 20 (23) |

| WBC >12 × 109/L | 15 (17) |

| WBC <12 × 109/L | 5 (6) |

| IPSS (49 evaluable patients) | |

| Intermediate-1 | 13 (26) |

| Intermediate-2 | 23 (48) |

| High | 13 (48) |

| MDACC risk modela at initiation of decitabine | |

| Low | 7 (8) |

| Intermediate-1 | 17 (19) |

| Intermediate-2 | 31 (36) |

| High | 32 (37) |

| MDACC risk model at decitabine failure (58 evaluable patients) | |

| Low | 2 (4) |

| Intermediate-1 | 7 (12) |

| Intermediate-2 | 17 (29) |

| High | 32 (55) |

MDS indicates myelodysplastic syndrome; CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; RA, refractory anemia; RARS, refractory anemia with ringed side-roblasts; RAEB, refractory anemia with excess blasts; RAEBT, refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation; WBC, white blood cell count; IPSS, International Prognostic Scoring System; MDACC, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Low risk (score 0–4): the median survival is 54 months and the 3-year survival rate is 63%; intermediate-1 risk (score 5–6): the median survival is 25 months and the 3-year survival rate is 34%; intermediate-2 risk (score 7–8): the median survival is 14 months and the 3-year survival rate is 16%; high risk (score ≥9): the median survival is 6 months and the 3-year survival rate is 4%.

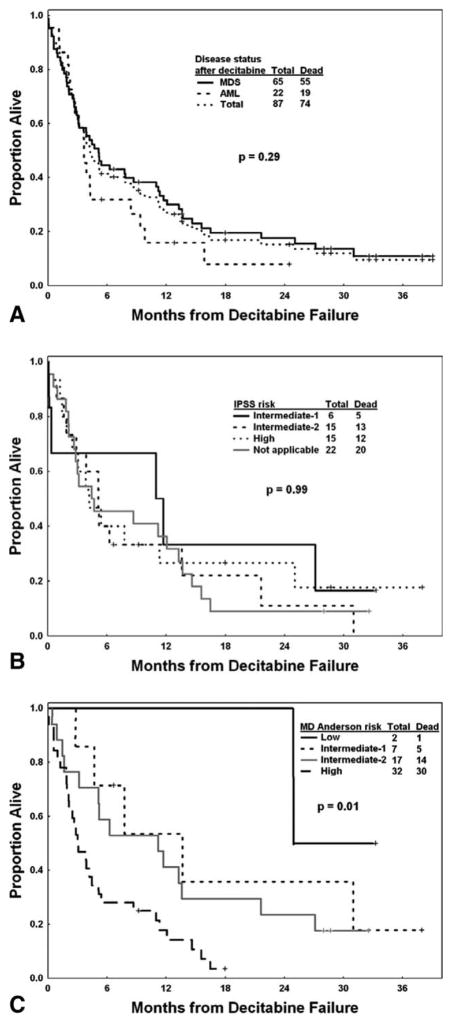

After a median follow-up of 21 months (range, 6 to 39 months) from decitabine failure, 13 patients (15%) remained alive. The median survival afterdecitabine failure was 4.3 months and the estimated 12-month survival rate was 28% (Fig. 1A); this was similar to the median survival (16 weeks) observed after idarubicin and high-dose cytarabine (IA) failure in 36 matched-cohort patients (patients were matched based on treatment era, blasts percentage, and chromosomal abnormalities). At the time of treatment failure, 22 patients (25%) already had disease evolve into AML; only 3 were alive at the time of last follow-up. Sixty-five patients (75%) had disease failure on decitabine and still as MDS. The estimated 12-month survival rates for patients with MDS and AML after decitabine failure were 32% and 16%, respectively (P = .29). Among 36 patients assessed by the IPSS, 15 (42%) had high-risk, 15 (42%) had intermediate-2-risk, and 6 (8%) had intermediate-1-risk disease. Their estimated 12-month survival rates were 27%, 33%, and 33%, respectively (P = .99) (Fig. 1B). Fifty-eight patients with decitabine failure in MDS or CMML stage were assessed by the MDACC risk model: 32 (55%) had high-risk, 17 (29%) had intermediate-2-risk, 7 (12%) had intermediate-1-risk, and 2 (4%) had low-risk disease. Their 12-month survival rates were 18%, 41%, 54%, and 100%, respectively (P = .01) (Fig. 1C). Considering survival from the time of the initiation of decitabine therapy, the estimated 12-month survival rates were 44%, 58%, 76%, and 86%, respectively, for patients with high-risk, intermediate-2-risk, intermediate-1-risk, and low-risk disease according to the MDACC risk model (P <.001) (Table 3). Previous response to decitabine appeared to have no impact on survival after failure (P = .74).

Figure 1.

Overall survival after decitabine failure is shown (A) overall, (B) by the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS), and (C) by The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center risk model. MDS indicates myelodysplastic syndrome; AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

Table 3.

Survival After Decitabine Failure

| Risk Group | No. of Patients | 12-Month Survival Rate, % | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At initiation of decitabine therapy | MDACCa-Low | 7 | 86 | <.001 |

| MDACC-Int-1 | 17 | 76 | ||

| MDACC-Int-2 | 31 | 58 | ||

| MDACC-High | 32 | 44 | ||

| At decitabine failure | MDACC-Low | 2 | 100 | .01 |

| MDACC-Int-1 | 7 | 54 | ||

| MDACC-Int-2 | 17 | 41 | ||

| MDACC-High | 32 | 18 | ||

| IPSS-Int-1 | 6 | 33 | .99 | |

| IPSS-Int-2 | 15 | 33 | ||

| IPSS-High | 15 | 27 | ||

| IPSS-NA | 22 | 36 | ||

| Failure as MDS/CMML | 65 | 32 | .29 | |

| Failure as AML | 22 | 16 |

MDACC indicates The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center risk model; Int, intermediate; IPSS, International Prognostic Scoring System; NA, not applicable; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; CMML, chronic myeloid leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

Low risk (score 0–4): the median survival is 54 months and the 3-year survival rate is 63%; intermediate-1 risk (score 5–6): the median survival is 25 months and the 3-year survival rate is 34%; intermediate-2 risk (score 7–8): the median survival is 14 months and the 3-year survival rate is 16%; high risk (score ≥9): the median survival is 6 months and the 3-year survival rate is 4%.

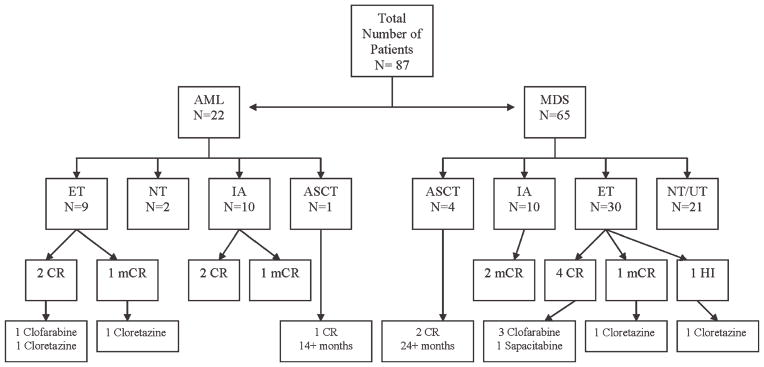

After decitabine failure (Fig. 2), of the 22 patients with AML, 10 received IA chemotherapy, 2 of whom achieved a CR of a median duration of 6 months and 1 a bone marrow CR of ≥5 months; 9 patients received investigational agents, 2 of whom achieved a CR of 3 months and 11 months, after clofarabine and cloretazine, respectively, and 1 achieved a bone marrow CR of 8 months after cloretazine; 1 patient received an ASCT that resulted in a sustained CR of ≥14 months; and 2 patients elected not to receive any further therapies.

Figure 2.

Outcome after decitabine failure is shown (n = .87). AML indicates acute myeloid leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; ET, experimental therapies; NT, no therapy; IA, idarubicin and cytarabine; ASCT, allogeneic stem cell transplantation; UT, unknown therapy; CR, complete remission; mCR, (bone) marrow complete remission; HI, hematologic improvement.

Of the 65 patients who remained in MDS, 10 received IA, 2 of whom achieved a bone marrow CR of a median duration of 7 months; 30 patients received investigational agents, 3 of whom achieved a CR of a median duration of 5 months after clofarabine, 1 a CR of 4 months after sapacitabine, and 2 a bone marrow CR of 3 months and a hematologic improvement of 2 months after clofarabine, respectively; 4 patients received an ASCT, 2 of whom achieved a sustained CR of ≥24 months; 6 patients received unknown therapies; and 15 patients elected not to receive any further therapies.

At the time of last follow-up, 13 patients were alive, 4 of whom in CR (2 after ASCT, 1 after clofarabine, and 1 after IA). One patient remained in bone marrow CR ≥5 months after IA chemotherapy.

DISCUSSION

The prognosis of patients with MDS and CMML after failure of hypomethylating agent therapy has been suspected to be poor, but to the best of our knowledge, there are no published data regarding their prognosis. This is important for patient and physician decision-making, as well as to establish individual patient expectations and to assess the benefit of newer therapies.

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first to provide survival estimates after decitabine failure.

As expected, prognosis after decitabine failure was poor, with a median survival of 4.3 months. There was no difference in outcome noted between patients whose disease transformed into AML and those in whom it did not.

The MDACC risk model predicted outcome at the initiation of decitabine therapy8 as well as after decitabine failure, whereas the IPSS did not predict survival after decitabine failure.7 IPSS was designed for patients with de novo MDS and excluded patients who had previous therapies, secondary MDS, or CMML with a white blood cell count >12 × 109/L. The MDACC risk model could thus be used to advise patients of their prognosis and treatment options, and to evaluate the benefit of newer therapies after the failure of hypomethylating agent therapy.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have received financial support from the Betty Foster Leukemia Research Fund. These funds were used to help defray the cost for research nurses.

References

- 1.Silverman LR, Demakos EP, Peterson BL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of azacitidine in patients with the myelodys-plastic syndrome: a study of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2429–2440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fenaux P, Mufti G, Santini V, et al. Azacitidine (AZA) treatment prolongs overall survival (OS) in higher-risk MDS patients compared with conventional cure regimens (CCR): results of the AZA-001 phase III study [abstract] Blood. 2007;110:250a. Abstract 817. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kantarjian H, Issa JP, Rosenfeld CS, et al. Decitabine improves patient outcomes in myelodysplastic syndromes: results of a phase III randomized study. Cancer. 2006;106:1794–1803. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantarjian H, Oki Y, Garcia-Manero G, et al. Results of a randomized study of 3 schedules of low-dose decitabine in higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:52–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kantarjian HM, O’Brien S, Huang X, et al. Survival advantage with decitabine versus intensive chemotherapy in patients with higher risk myelodysplastic syndrome: comparison with historical experience. Cancer. 2007;109:1133–1137. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheson BD, Greenberg PL, Bennett JM, et al. Clinical application and proposal for modification of the International Working Group (IWG) response criteria in myelodysplasia. Blood. 2006;108:419–425. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, et al. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 1997;89:2079–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, Ravandi F, et al. Proposal for a new risk model in myelodysplastic syndrome that accounts for events not considered in the original International Prognostic Scoring System. Cancer. 2008;113:1351–1361. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;60:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]