Abstract

Background and Purpose

In malignant infarction, brain edema leads to secondary neurological deterioration and poor outcome. We sought to determine whether swelling is associated with outcome in smaller volume strokes.

Methods

Two research cohorts of acute stroke subjects with serial brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were analyzed. The categorical presence of swelling and/or infarct growth was assessed on diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) by comparing baseline and follow-up scans. The increase in stroke volume (ΔDWI) was then subdivided into swelling and infarct growth volumes using region-of-interest analysis. The relationship of these imaging markers with outcome was evaluated in univariable and multivariable regression.

Results

The presence of swelling independently predicted worse outcome after adjustment for age, NIH stroke scale, admission glucose, and baseline DWI volume(OR4.55, 95%CI1.21-18.9, p < 0.02). Volumetric analysis confirmed ΔDWI was associated with outcome (OR4.29, 95%CI 2.00-11.5, p < 0.001). After partitioning ΔDWI into swelling and infarct growth volumetrically, swelling remained an independent predictor of poor outcome (OR1.09, 95%CI 1.03-1.17, p < 0.005). Larger infarct growth was also associated with poor outcome (OR7.05, 95%CI 1.04-143, p < 0.045), although small infarct growth was not. The severity of cytotoxic injury measured on apparent diffusion coefficient maps was associated with swelling, whereas the perfusion deficit volume was associated with infarct growth.

Conclusions

Swelling and infarct growth each contribute to total stroke lesion growth in the days following stroke. Swelling is an independent predictor of poor outcome, with abrain swelling volume of ≥11mL identified as the threshold with greatest sensitivity and specificity for predicting poor outcome.

Keywords: stroke, outcome, brain edema, swelling, magnetic resonance imaging, apparent diffusion coefficient

Introduction

Neurological deterioration is a well-described complication of large hemispheric stroke, principally caused by the formation of cerebral edema.1, 2 The disease is associated with high morbidity and mortality,3–5 with limited medical and surgical treatment options available.6–8 Edema typically peaks3-5 days after stroke onset, 9 although a malignant form can present within 24 hours and leads to precipitous decline.3, 10

In this study, we sought to characterize the extent to which swelling or infarct growth contributed to neurological outcome in a broader range of stroke severity. Imaging markers of swelling were established in two cohorts with serial research MRI during the first 2-5 days following stroke. We also investigated the relationship of swelling to lesional tissue properties that characterize brain injury and swelling,11, 12including apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values representing early cytotoxic injury,13, 14and hyper intensity on T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging, a putative tissue clock for ischemia 15that may also reflect the degree of blood-brain barrier disruption.12, 16 We hypothesized that brain edema is relevant to outcome in a broad stroke population, potentially making it an attractive therapeutic target.

Methods

Patient Characteristics

Brain MRI scans were retrospectively analyzed in two cohorts of acute stroke subjects: the placebo arm of the Normobaric Oxygen Therapy in Acute Ischemic Stroke trial cohort (NBO, NCT00414726) and the Echoplanar Imaging Thromobolysis Evaluation Trial cohort (EPITHET, NCT00238537). The NBO study enrolled patients from 2007-2009 who were treated with room air, and acquired brain MRI within the first 9 hours of stroke symptom onset, and again 4 hours, 24 hours, and 48 hours later. Subjects with baseline DWI volumes of < 10mL were excluded in this study to avoid the risk of classifying volume averaging artifacts. 12Imaging markers were also investigated in the EPITHET cohort in order to perform association testing with clinical outcome. The full details of the EPITHET cohort are described elsewhere.17 Briefly, the EPITHET study enrolled patients from 2001-2007 with baseline MRI within 3-6 hours of stroke on set and follow-up MRI3-5 days later.

For both cohorts, subjects were included in the present study if they had baseline and at least one follow-up DWI scan available along with clinical data. Subjects without clinical data, DWI at either baseline or follow-up, or DWI of insufficient quality (due to excessive motion) were excluded from the study. Clinical outcome data were obtained via standard assessment 90 days after stroke using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score. A good outcome was defined as a mRS of 0-2 and a poor outcome as mRS of 3-6. No subjects in either cohort had a lacunar stroke sub-type or were treated with endovascular therapy. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and all subjects or their legally authorized representative originally provided informed consent prior to participation in each study.

Imaging Analysis

Region-of-interest (ROI) analysis was conducted using a semi-automated method in Analyze 11.0 (Biomedical Imaging Resource, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA),based on our prior methods. 11 Briefly, the stroke lesion and normal contra lateral hemisphere ROIs were initially defined on DWI, transferred to the ADC map for removal of cerebrospinal fluid and calculation of ADCr, and then applied to a co-registered FLAIR sequence when available to calculate FLAIRr (please see Figure I at http://stroke.ahajournals.org). Stroke volume and intensity ratios were calculated on baseline and follow-up MRI for all subjects. Imaging analyses were performed by trained readers (T.W.K.B., M.K.) blinded to clinical and outcome data and separately reviewed by another blinded reader (W.T.K.). For additional quality control, stroke volumes generated in this study were compared with prior values obtained as part of the original trial analyses. Similar to our prior experience, the intra class correlation coefficient was 0.97.11

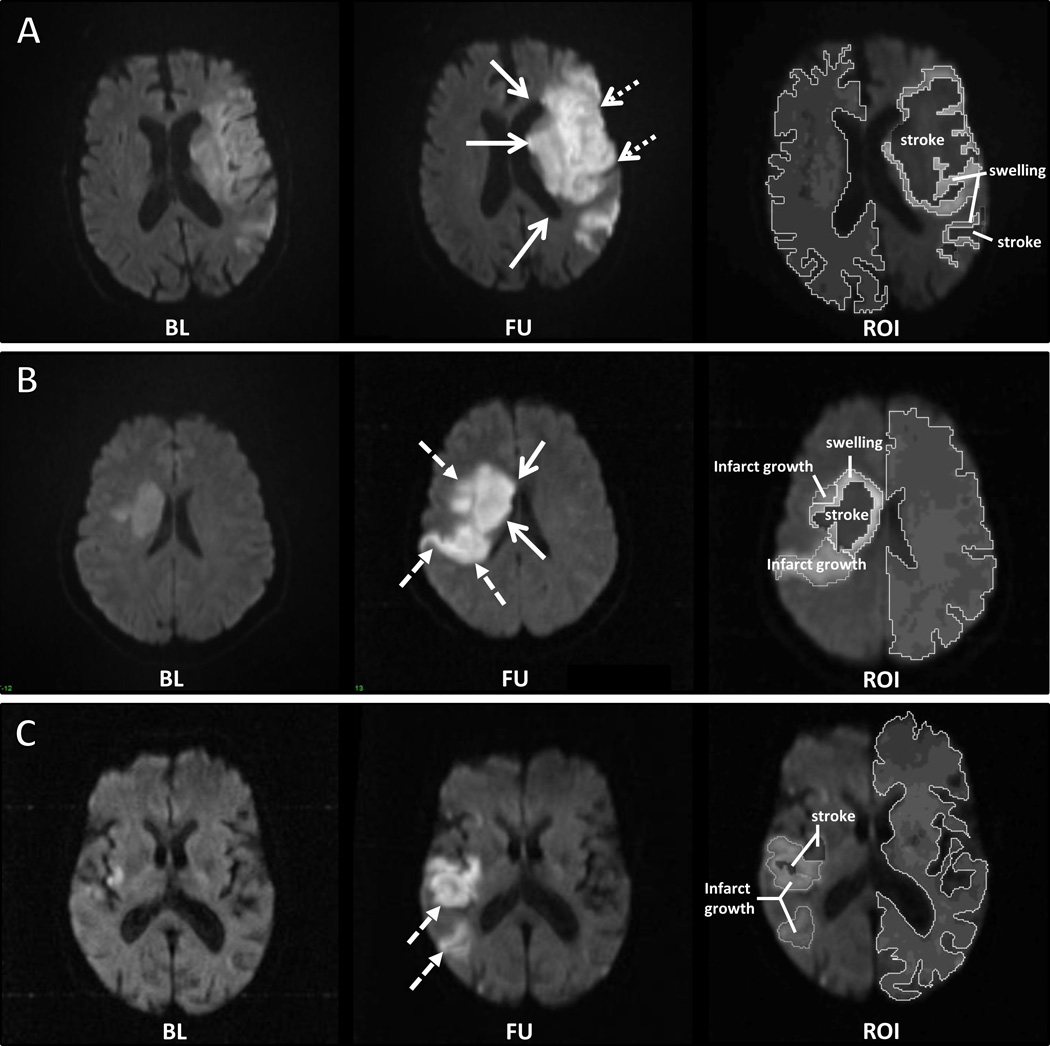

Stroke lesion expansion (ΔDWI) was defined as the change in lesion volume between baseline and follow-up DWI. 17–20The presence or absence of swelling and infarct growth was assessed by two readers (T.W.K.B., W.T.K.) blinded to clinical and outcome data. Designations were made by comparing baseline and follow-up MRI scans side-by-side simultaneously in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes using the Analyze 11.0 3D Voxel Registration module. Swelling was determined to be present if two or more of the following criteria were met on two or more axial DWI slices: 1) direct evidence of mass effect of affected gyri, or 2) indirect evidence based on new distortion of adjacent tissue, new midline shift, or new effacement of sulci or lateral ventricle (see Figure 1). This two-by-two method was employed to reduce the chance of misclassifying infarct growth as swelling. The inter rater agreement of this method had a κ of 0.41 (“fair agreement”), which is similar to hemorrhagic transformation designation, 21–23 and the final assignment was determined by consensus.

Figure 1. Examples of swelling, infarct growth, and both.

Baseline DWI was compared to the co-registered follow-up DWI to assess the presence of swelling or infarct growth. (A) A patient who developed swelling between baseline and follow-up scan, demonstrating ventricular effacement and expansion of the caudate head (solid arrows) and loss of sulci (dotted arrows). (B) An example of both swelling (solid arrows) and infarct growth (dashed arrows). (C) An example of infarct growth (dashed arrows).The right hand most images in each panel demonstrate the volumes attributed to either swelling or infarct growth. BL=baseline; FU=follow-up; ROI=region of interest on the follow-up scan.

Infarct growth was defined as involvement of new anatomical territory either adjacent to or distinct from the baseline lesion, using the Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS).24The ASPECTS was used because it is a validated and reproducible method of quantifying the neuroanatomic territories involved in a stroke lesion. Infarct growth was defined as an increase in affected ASPECTS regions ≥1 from baseline to follow-up imaging. In an exploratory analysis, we reasoned that infarct growth defined by a change in ASPECTS regions ≥1 may include subjects with small amounts of infarct growth of limited clinical significance. Therefore, we assessed different cutoff points for the change in ASPECTS regions (changes in ASPECTS ≥2, ≥3).

The volumes of swelling and infarct growth were then determined for each subject on co-registered images using the Analyze 11.0 Volume Edit and ROI modules. New neuroanatomic areas of infarction not present on the baseline MRI were first identified on the follow-up MRI in the axial, sagittal and coronal planes and then outlined in the Volume Edit module (see Figure 1 for examples). Hemorrhage was excluded, although its exclusion did not alter the final analysis. The final volumes were determined based on the relationship: ΔDWI = infarct growth + swelling.

Statistical Analysis

Outcome testing with swelling and infarct growth was conducted in the EPITHET cohort and analysis of lesional tissue properties was conducted in the NBO cohort. Descriptive statistics of baseline variables and outcomes are reported as mean±standard deviation (for normally distributed continuous data), median with inter quartile range ([IQR]; for non-normal or ordinal data), and proportions (for binary data). Inter-rater agreement was assessed for stroke volume using intra class correlation coefficient and Bland–Altman analyses. The relationships between imaging and clinical covariates were assessed using Pearson or Spearman correlation testing, as appropriate. Univariate logistic regression was performed to investigate the association of clinical and imaging variables with outcome. Multivariate logistic regression models were developed to test for independent effects. All tests were two-sided, with the threshold of significance set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro 11.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Clinical Characteristics

The clinical characteristics of the two study populations are shown in Table 1. The cohorts were similar in age and comorbidities. Of 20 subjects from the placebo arm of the NBO cohort, 1 was excluded because there was no follow-up MRI. Of 101original subjects in the EPITHET cohort, 12 did not have DWI of sufficient quality for interpretation, 10 had no follow-up MRI, and 1 subject had no available scans. 19 NBO subjects and 78 EPITHET subjects constituted the final study populations. Based on the exclusion criteria of the original trial, the NBO cohort did not include patients treated with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (IV tPA). In the NBO cohort, the admission MRI was obtained on average 3 hours later than in EPITHET, and the median admission infarct volume was larger by 12 mL. Both cohorts consisted of patients with moderate to severe strokes, with a median admission NIH stroke scale (NIHSS) score between 13 and 14, and a median 90-day mRS score of 3.

Table 1.

Clinical and imaging characteristics of the patients

| NBO | EPITHET | |

|---|---|---|

| n=19 | n=78 | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 73±13 | 72±13 |

| Sex, male, N (%) | 15(78%) | 42(53%) |

| Comorbidities, N (%) | ||

| Diabetes | 4(21%) | 19(24%) |

| Hypertension | 14(74%) | 55(71%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 13(63%) | 33(42%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 10(53%) | 33(42%) |

| IV tPA, N (%)a | 0(0%) | 36(46%) |

| Admission NIHSS, median[IQR] | 14[7, 19] | 13[8, 17] |

| Time from LSWto MRI (hrs), mean±SDa | 7.0±3.0 | 4.1±0.9 |

| Admission DWI volume (mL), median[IQR]b | 33[14, 77] | 21[9, 51] |

| Admission PWI volume (mL), median[IQR] | 140[85, 189] | 157[95, 239] |

| Admission FLAIR ratio, mean±SD | 1.21±0.12 | - |

| Admission ADC ratio, mean±SD | 0.693±0.067 | 0.685±0.075 |

| Delta DWI volume (mL), median[IQR] | 25[10, 51] | 14[5, 66] |

| Swelling, N(%) | 13(68%) | 53(67%) |

| Infarct growth, N(%) | 7(39%) | 34(43%) |

| modified Rankin Scale score, median[IQR] | 3[2, 6] | 3[1,4] |

p<0.001;

p<0.05

Swelling Predicts Outcome after Stroke

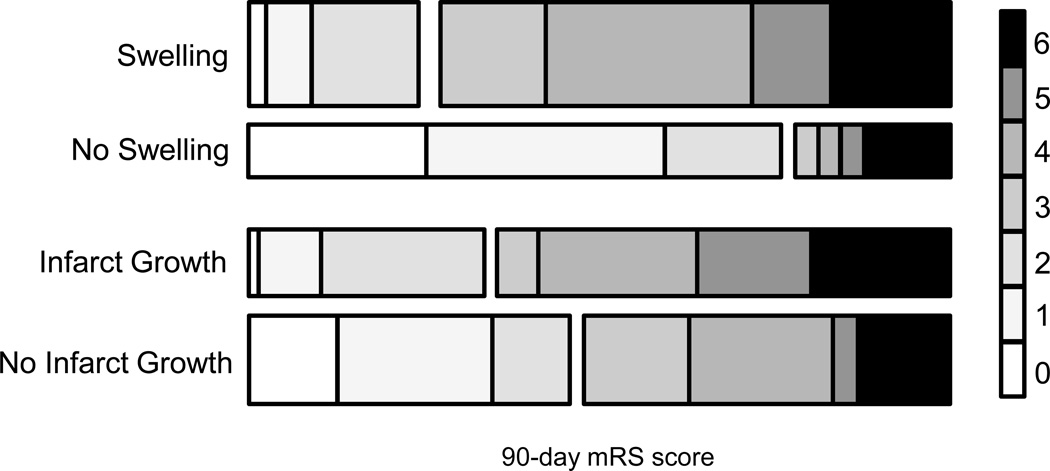

The EPITHET cohort had a baseline MRI and follow-up MRI obtained during the period of peak swelling 3-5 days after stroke onset. Evidence of swelling was present in 67% of subjects, with infarct growth present in 43% (Table 1). The distribution of mRS scores for subjects dichotomized into the presence or absence of swelling (univariate p < 0.002) and infarct growth (univariate p=0.33) is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Distribution of 90-day modified Rankin Scale scores for subjects with and without swelling or infarct growth.

The distribution of outcomes for swelling and infarct growth are shown, with the right hand key representing each category of mRS as labeled. The height of each bar represents the percentage of the cohort with each score.

Next, we performed univariate regression to identify additional predictors of poor 90-day functional outcome. Baseline NIHSS, admission glucose level, swelling, and admission DWI volume were all associated with poor outcome (Table 2). After adjustment, the presence of swelling remained an independent predictor of poor 90-day outcome (p=0.02), whereas infarct growth did not (p=0.64). The inclusion of sex in the model did not alter the independent association of swelling with poor outcome.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate predictors of poor outcome after stroke

| mRS 0-2 | mRS 0-2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% Cl | P value | Adjusted OR | 95% Cl | P value | |

| Age | 1.02 | (0.99 to 1.06) | 0.13 | 1.07 | (1.02 to 1.14) | 0.01 |

| Sex (female) | 0.80 | (0.36 to 1.79) | 0.59 | -- | -- | -- |

| Admission glucose | 4.09 | (1.15to 17.6) | 0.029 | 3.88 | (0.55 to 36.9) | 0.20 |

| Admission NIHSS | 1.17 | (1.08 to 1.28) | <0.001 | 1.18 | (1.03 to 1.39) | 0.02 |

| Admission DWI volume | 5.79 | (2.25 to 17.3) | <0.001 | 4.67 | (1.13 to 24.0) | 0.03 |

| Swelling | 7.18 | (2.48 to 23.3) | <0.002 | 4.55 | (1.21 to 18.9) | 0.02 |

| Infarct growth (Δ ASPECTS ≥1) | 1.59 | (0.63 to 4.16) | 0.33 | 1.35 | (0.38 to 4.82) | 0.64 |

Admission glucose and DWI volume were log-transformed prior to inclusion in the regression model. Data are from the EPITHET cohort.

Evaluation of incremental changes in the magnitude of infarct growth demonstrated that large infarct growth was associated with outcome both in univariate and multivariate analyses (please see Table I at http://stroke.ahajournals.org). Importantly, swelling remained an independent predictor of poor outcome in each of the models tested.

Volumetric Lesion Analysis

The change in stroke lesion volume between baseline and follow-up scans (ΔDWI) has previously been reported as a marker for lesion growth.18–20 We confirmed that ΔDWI represents a composite measure that encompasses both infarct growth into new anatomic territory and space-occupying brain edema by testing the association of the binary variables for swelling and infarct growth with ΔDWI. Both were independently associated with ΔDWI, confirming that each contributed to lesion expansion (both p < 0.0001). Moreover, when ΔDWI was substituted for swelling and infarct growth in the multivariate regression model, it was independently associated with poor 90-day (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable modeling of the volume of swelling and infarct growth with poor outcome

| mRS 0-2 | mRS 0-2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR | 95% Cl | P value | Adjusted OR | 95% Cl | P value | |

| Age | 1.07 | (1.02 to 1.13) | 0.01 | 1.10 | (1.03 to 1.18) | 0.001 |

| Sex (female) | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Admission glucose | 4.47 | (0.57 to 49.4) | 0.18 | 6.58 | (0.64 to 103) | 0.12 |

| Admission NIHSS | 1.13 | (0.99 to 1.30) | 0.07 | 1.18 | (1.02 to 1.39) | 0.03 |

| Admission DWI volume | 2.41 | (0.56 to 11.3) | 0.24 | 1.46 | (0.26 to 9.33) | 0.67 |

| ΔDWI volume | 4.29 | (2.00 to 11.5) | <0.001 | -- | -- | |

| Volume of swelling | -- | -- | 1.09 | (1.03 to 1.17) | 0.003 | |

| Volume of infarct growth | -- | -- | 1.08 | (0.68 to 1.78) | 0.74 | |

Admission glucose, DWI volume, ΔDWI volume and infarct growth volume were log-transformed prior to inclusion in the regression model, in the EPITHET cohort.

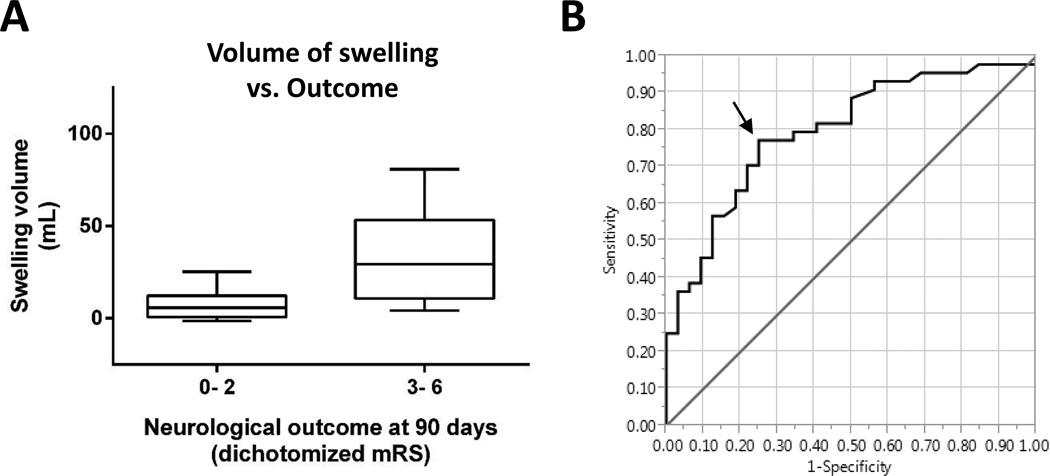

Next, we tested the relationship between the volumetric contributions of swelling and infarct growth and outcome. In univariate analysis, the volume of swelling was associated with poor outcome (Figure 3A, p < 0.001), whereas infarct growth volume demonstrated a trend (p=0.11). In multivariable regression analysis, replacement of ΔDWI volume with swelling and infarct growth volumes confirmed that swelling was an independent predictor of outcome (p=0.003; Table 3). Importantly, since the baseline DWI lesion volume predicted the development of swelling (p < 0.01), the inclusion (or removal) of the baseline DWI volume in the multivariable model did not alter the independent association between swelling and outcome. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis showed that 11mL of swelling volume had the highest sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing good versus poor outcome (Figure 3B; sensitivity 77%, specificity 75%, AUC=0.798). A similar ROC curve analysis for the prediction of swelling from the baseline DWI scan revealed that a volume ≥13mL had the greatest sensitivity (81%) and specificity (67%) for identifying subjects who later developed swelling (area under the curve 0.790).

Figure 3. Greater swelling is associated with poor neurological outcome.

(A) The volume of swelling in subjects with mRS of 3-6 was higher than those with a 90 day mRS of 0-2 (p < 0.001). (B) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis shows that swelling of 11mL predicts poor outcome with a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 75%, identified by the arrow. The area under the curve was 0.798.

Tissue Properties Associated with Swelling

Next, we investigated whether tissue properties of the stroke lesion assessed by MRI were associated with swelling or infarct growth. First, we confirmed that admission perfusion deficit volume was associated with infarct growth (p < 0.001). Next we hypothesized that the degree of cytotoxic injury or blood-brain barrier (BBB) breakdown may predict subsequent swelling.13, 25 In addition to analyzing MRI scans in the EPITHET cohort, we extended our analysis to include the NBO cohort which had the added advantage of increased frequency, timing and type of sequences available for analysis. This permitted detailed analysis of the time course of the lesional tissue characteristics (please see Figure II at http://stroke.ahajournals.org).

We first evaluated the relative signal intensity of ADC (ADCr), which is considered a marker for cytotoxic injury.13, 14 In the EPITHET cohort, a lower baseline ADCr was associated with swelling volume (r= -0.31, p=0.006). Similarly, in the NBO cohort, ADCr was associated with the presence of swelling (p=0.04). On the other hand, and in both cohorts, ADCr was not associated with outcome (p=0.32 and 0.25 for NBO and EPITHET cohorts, respectively).

Next we evaluated the signal intensity ratio of T2 FLAIR (FLAIRr), which is hypothesized to reflect the degree of BBB breakdown12, 16potentially leading to extravasation of fluid into the infarct. 25 FLAIR sequences were only available in the NBO cohort, and consistent with prior reports, 11 FLAIRr increased progressively over the first two days. In addition, the baseline FLAIRr was associated with the 48 hour FLAIRr (r=0.54, p=0.03), suggesting intra-subject differences that persist over time. Nevertheless, FLAIRr was not predictive of swelling (p=0.51) nor was it associated with outcome (p=0.76).

Discussion

Brain edema is a well-recognized secondary complication of stroke, yet the deleterious effect of swelling is only recognized incases of malignant infarction. The main treatment option for malignant edema is surgical decompression,7, 8 and existing evidence supports the conclusion that swelling is causally related to outcome, at least in large hemispheric stroke. In this study, we investigated the relationship between imaging markers of cerebral edema and clinical outcome in patients with a wider range of stroke severity. Our data provide evidence for an association between swelling and poor functional outcome in moderately sized stroke, highlighting the broader clinical relevance of brain edema in stroke populations. Although our data do not address causality of edema in this patient population, its well-defined role in malignant edema suggests that it may be causally relevant in stroke patients across the spectrum of stroke severity.

Our analysis also demonstrated that lesional volume measures such as ΔDWI appear to represent a composite imaging measure comprised of infarct growth and edema. Although each was independently associated with ΔDWI, infarct growth had a more nuanced association with outcome. This some what unexpected finding might be due to the fact that the mRS scoring system may not discriminate differences in patients with smaller amounts of infarct growth, or that our power for detection was limited by sample size. Notably, a recent study evaluated changes in ASPECTS in an endovascular population, and also found that large changes were predictive of poor outcome. 26 Future work on ΔDWI may yield further insight into the relationships of infarct growth and swelling to ΔDWI, and particularly whether there is a time-dependent effect of each. Validation in additional cohorts as well as prospective study will aid in more precisely defining their respective roles.

Our analysis also explored imaging determinants of swelling, and found that baseline DWI volume and ADCr predicted swelling. The finding that larger strokes are associated with greater swelling is not surprising and is consistent with the malignant course that accompanies many large strokes.27 On the other hand, it is interesting that ADC signal intensity is associated with swelling, since the ADC is sensitive to the early cytotoxic ischemia that develops minutes after stroke onset.13, 14 Preclinical studies have demonstrated that the severity of the initial cytotoxic injury influences the volume of subsequent brain swelling in the days thereafter,28–30 a finding which is recapitulated here. Taking preclinical and clinical studies together, this raises the possibility that osmotic forces may be a primary contributor to brain swelling. 31 We also explored the relationship with a marker of blood-brain barrier breakdown, FLAIRr.12, 16 Our rationale for doing so was that physical leakage of fluid through degraded BBB may contribute to brain swelling, a process sometimes termed hydrostatic edema.25 Although we cannot exclude a small association, we did not find any correlation with swelling in our study. As such, FLAIRr may serve as a risk marker for hemorrhagic transformation12, 32 or to estimate the onset of hyper acute infarction,15 rather than risk of swelling.

Finally, the imaging biomarkers described here may prove useful for clinical application. First, ADCr may be used to identify patients at risk for clinically meaningful swelling. Not only may patients with lower ADCr warrant closer observation for secondary neurological decline, but also careful avoidance of factors which may exacerbate swelling, such as administration of hypotonic solutions. Secondly, ADCr could be used to select patients for inclusion in clinical trials targeting novel anti-edema therapies. Although prospective study would be necessary, it may also be of interest to determine whether ADCr could be used to select patients for osmotherapy treatment.

However, our data also highlight the potential challenges associated with the use of surrogate imaging markers in clinical trial design. Although strongly associated with 90-day neurological outcome, we show that ΔDWI is a composite marker for both swelling and infarct growth. Apportioning the total ΔDWI into swelling and infarct growth volumes may provide a more precise approach and provide greater utility as surrogate imaging markers. Our study has limitations. This was a retrospective analysis. However, it was performed in two cohorts with serial research brain MRIs and showed similar results. Nevertheless, the sample size was relatively small and included only moderate to severe infarction. It is not certain whether these data can be generalized to mild strokes with infarct volumes < 10mL or an NIHSS < 4. It is also possible that misclassification bias may exist in separating infarct growth and swelling, although we used conservative definitions to minimize this potential risk. The study’s strengths include the timing and frequency of brain MRI in two separate and well-defined study cohorts.

Summary

Taken together, these data demonstrate that brain edema measured on MRI is associated with poor outcome after moderate to severe stroke. Future prospective study is warranted to assess the potential causative role of edema in influencing outcome in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

The original funding for the NBO trial was from the NIH/NINDSR01NS051412 (A.B.S.). The analysis performed for this study was funded in part by the NIH/NINDS K23NS076597 (W.T.K.).

Footnotes

Disclosures

T.W.K. Battey: None; M. Karki: None; O. Wu: Research grants from NIH/NINDS R01NS059775, P50 NS051343, R01 NS051412; S. Sadaghiani: None; A.B. Singhal: Research grants from NIH/NINDS R01NS051412, P50NS051343, and R21NS077442. B.C.V. Campbell: None; S.M. Davis: Honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS Pfizer, Allergan, Covidien and EVER Neuropharma; Consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim. G.A. Donnan: None; K.N. Sheth: Research grant from Remedy Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; W.T. Kimberly: Research grants from NIH/NINDS K23NS076597 and Remedy Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

References

- 1.Wijdicks EF, Diringer MN. Middle cerebral artery territory infarction and early brain swelling: Progression and effect of age on outcome. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1998;73:829–836. doi: 10.4065/73.9.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wijdicks EF, Sheth KN, Carter BS, Greer DM, Kasner SE, Kimberly WT, et al. Recommendations for the management of cerebral and cerebellar infarction with swelling: A statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2014;45:1222–1238. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000441965.15164.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hacke W, Schwab S, Horn M, Spranger M, De Georgia M, von Kummer R. 'Malignant' middle cerebral artery territory infarction: Clinical course and prognostic signs. Archives of neurology. 1996;53:309–315. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550040037012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berrouschot J, Sterker M, Bettin S, Koster J, Schneider D. Mortality of space-occupying ('malignant') middle cerebral artery infarction under conservative intensive care. Intensive care medicine. 1998;24:620–623. doi: 10.1007/s001340050625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimberly WT, Sheth KN. Approach to severe hemispheric stroke. Neurology. 2011;76:S50–S56. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820c35f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofmeijer J, van der Worp HB, Kappelle LJ. Treatment of space-occupying cerebral infarction. Critical care medicine. 2003;31:617–625. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050446.16158.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vahedi K, Hofmeijer J, Juettler E, Vicaut E, George B, Algra A, et al. Early decompressive surgery in malignant infarction of the middle cerebral artery: A pooled analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Lancet neurology. 2007;6:215–222. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juttler E, Unterberg A, Woitzik J, Bosel J, Amiri H, Sakowitz OW, et al. Hemicraniectomy in older patients with extensive middle-cerebral-artery stroke. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;370:1091–1100. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaw CM, Alvord EC, Jr, Berry RG. Swelling of the brain following ischemic infarction with arterial occlusion. Archives of neurology. 1959;1:161–177. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1959.03840020035006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qureshi AI, Suarez JI, Yahia AM, Mohammad Y, Uzun G, Suri MF, et al. Timing of neurologic deterioration in massive middle cerebral artery infarction: A multicenter review. Critical care medicine. 2003;31:272–277. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimberly WT, Battey TW, Pham L, Wu O, Yoo AJ, Furie KL, et al. Glyburide is associated with attenuated vasogenic edema in stroke patients. Neurocritical care. 2014;20:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s12028-013-9917-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jha R, Battey TW, Pham L, Lorenzano S, Furie KL, Sheth KN, et al. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensity correlates with matrix metalloproteinase-9 level and hemorrhagic transformation in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2014;45:1040–1045. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayata C, Ropper AH. Ischaemic brain oedema. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2002;9:113–124. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2001.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann-Haefelin T, Moseley ME, Albers GW. New magnetic resonance imaging methods for cerebrovascular disease: Emerging clinical applications. Annals of neurology. 2000;47:559–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomalla G, Rossbach P, Rosenkranz M, Siemonsen S, Krutzelmann A, Fiehler J, et al. Negative fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging identifies acute ischemic stroke at 3 hours or less. Annals of neurology. 2009;65:724–732. doi: 10.1002/ana.21651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ostwaldt AC, Rozanski M, Schmidt WU, Nolte CH, Hotter B, Jungehuelsing GJ, et al. Early time course of flair signal intensity differs between acute ischemic stroke patients with and without hyperintense acute reperfusion marker. Cerebrovascular diseases. 2014;37:141–146. doi: 10.1159/000357422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis SM, Donnan GA, Parsons MW, Levi C, Butcher KS, Peeters A, et al. Effects of alteplase beyond 3 h after stroke in the echoplanar imaging thrombolytic evaluation trial (epithet): A placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet neurology. 2008;7:299–309. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrett KM, Ding YH, Wagner DP, Kallmes DF, Johnston KC, Investigators A. Change in diffusion-weighted imaging infarct volume predicts neurologic outcome at 90 days: Results of the acute stroke accurate prediction (asap) trial serial imaging substudy. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2009;40:2422–2427. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.548933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura K, Sakamoto Y, Iguchi Y, Shibazaki K. Serial changes in ischemic lesion volume and neurological recovery after t-pa therapy. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2011;304:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho KH, Kwon SU, Lee DH, Shim W, Choi C, Kim SJ, et al. Early infarct growth predicts long-term clinical outcome after thrombolysis. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2012;316:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wardlaw JM, Sellar R. A simple practical classification of cerebral infarcts on ct and its interobserver reliability. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 1994;15:1933–1939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motto C, Aritzu E, Boccardi E, De Grandi C, Piana A, Candelise L. Reliability of hemorrhagic transformation diagnosis in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1997;28:302–306. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnould MC, Grandin CB, Peeters A, Cosnard G, Duprez TP. Comparison of ct and three mr sequences for detecting and categorizing early (48 hours) hemorrhagic transformation in hyperacute ischemic stroke. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2004;25:939–944. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barber PA, Demchuk AM, Zhang J, Buchan AM. Validity and reliability of a quantitative computed tomography score in predicting outcome of hyperacute stroke before thrombolytic therapy. Aspects study group. Alberta stroke programme early ct score. Lancet. 2000;355:1670–1674. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simard JM, Kent TA, Chen M, Tarasov KV, Gerzanich V. Brain oedema in focal ischaemia: Molecular pathophysiology and theoretical implications. Lancet neurology. 2007;6:258–268. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70055-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liebeskind DS, Jahan R, Nogueira RG, Jovin TG, Lutsep HL, Saver JL, et al. Serial alberta stroke program early ct score from baseline to 24 hours in solitaire flow restoration with the intention for thrombectomy study: A novel surrogate end point for revascularization in acute stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2014;45:723–727. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomalla G, Hartmann F, Juettler E, Singer OC, Lehnhardt FG, Kohrmann M, et al. Prediction of malignant middle cerebral artery infarction by magnetic resonance imaging within 6 hours of symptom onset: A prospective multicenter observational study. Annals of neurology. 2010;68:435–445. doi: 10.1002/ana.22125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Todd NV, Picozzi P, Crockard A, Russell RW. Duration of ischemia influences the development and resolution of ischemic brain edema. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1986;17:466–471. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.3.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell BA, Symon L, Branston NM. Cbf and time thresholds for the formation of ischemic cerebral edema, and effect of reperfusion in baboons. Journal of neurosurgery. 1985;62:31–41. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.1.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crockard A, Iannotti F, Hunstock AT, Smith RD, Harris RJ, Symon L. Cerebral blood flow and edema following carotid occlusion in the gerbil. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1980;11:494–498. doi: 10.1161/01.str.11.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mintorovitch J, Yang GY, Shimizu H, Kucharczyk J, Chan PH, Weinstein PR. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of acute focal cerebral ischemia: Comparison of signal intensity with changes in brain water and na+, k(+)-atpase activity. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1994;14:332–336. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kufner A, Galinovic I, Brunecker P, Cheng B, Thomalla G, Gerloff C, et al. Early infarct flair hyperintensity is associated with increased hemorrhagic transformation after thrombolysis. Eur J Neurol. 2013;20:281–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.