Abstract

Complex performance diagnostics in sports medicine should contain maximal aerobic and maximal anaerobic performance. The requirements on appropriate stress protocols are high. To validate a test protocol quality criteria like objectivity and reliability are necessary. Therefore, the present study was performed in intention to analyze the reliability of maximal lactate production rate (Lamax) by using a sprint test, maximum oxygen consumption (O2max) by using a ramp test and, based on these data, resulting power in calculated maximum lactate-steady-state (PMLSS) especially for amateur cyclists. All subjects (n = 23, age 26 ± 4 years) were leisure cyclists. At three different days they completed first a sprint test to approximate Lamax. After 60 min of recreation time a ramp test to assess O2max was performed. The results of Lamax-test and O2max-test and the body weight were used to calculate PMLSS for all subjects. The intra class correlation (ICC) for Lamax and O2max was 0.904 and 0.987, respectively, coefficient of variation (CV) was 6.3% and 2.1%, respectively. Between the measurements the reliable change index of 0.11 mmol·l -1s -1 for Lamax and 3.3 mlkg -1min -1 for O2max achieved significance. The mean of the calculated PMLSS was 237 ± 72 W with an RCI of 9 W and reached with ICC = 0.985 a very high reliability. Both metabolic performance tests and the calculated PMLSS are reliable for leisure cyclists.

Keywords: maximum oxygen consumption, maximal lactate production rate, maximal lactate steady state

INTRODUCTION

To assess anaerobic threshold (AT) exist multiple methods, that are discussed controversially [1–3]. Usually lactate threshold concepts use the blood lactate concentration as the only parameter to approximate power in maximal lactate steady state (PMLSS). The maximal lactate steady state (MLSS) is defined as the highest endurance work load that can be maintained with stable blood lactate without further increase of more than 0.05 mmol·l−1min−1 within the last 20 min of a 30 min constant load test [2]. However, Hauser et al. [3] showed that the individual differences of power assessed using different lactate threshold concepts and power measured at MLSS was up to 56 W. This might be relevant in defining optimal training plans. Furthermore, Bleicher et al. [4] demonstrated that equal lactate curves and their corresponding permanent exercise levels may result from different combinations of maximal oxygen uptake (O2max) and maximal lactate production rate ( Lamax) proving that two persons with equal AT have different metabolic parameters. Therefore the individual approximation of MLSS using only one single parameter seems to be problematic because MLSS is mainly influenced by O2max and Lamax.

To explain the metabolic background of MLSS, Mader and Heck [5] and Mader [6] published a mathematical description of the metabolic response based on measured values, exemplarily for a single muscle cell. Hauser [7] compared this calculated model with experimental assessed PMLSS during cycling. Despite significant correlation of both values they found differences. To further diminish these differences and to increase the reliability of the calculated PMLSS there is a need of reliable measurements of O2max and Lamax.

The reliability of O2max alone is already known for several tests, but not in the context of calculated PMLSS. Bleicher et al. [4] approximate Lamax according to Heck and Schulz [8] while using a 15 seconds sprint test. However, the approximation of Lamax is not established within sports medical performance analysis, that provokes a lack of data concerning the reliability of Lamax.

Therefore, the present study was performed in intention to analyze the reliability of Lamax by using a sprint test, O2max by using a ramp test and, based on these data, resulting calculated PMLSS especially for amateur cyclists.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

All subjects were amateur cyclists (sport students): 17 men, 6 women, age 26 ± 4 years (range 22 – 35 years), weight 71.6 ± 8.8 kg, body mass index 22.7 ± 1.8 kg -2. They were informed about the aims of the study and subsequently provided written consent in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki [9]. The trial is a proof-of-concept study. The experiments comply with the current laws of the country and the study was proved by Ethics Commission.

Procedures

The subjects were tested in a sports medical laboratory on a Lode cycle ergometer (Lode Excalibur Sport, Lode, Groningen, NL) with programmed test batteries. The subjects completed at three different test days first a sprint test with measurement of lactate levels as described below and calculation of Lamax. After 60 min of recreation time a ramp test to assess O2max was performed. A period of three to six days separated any two consecutive test days. The results of Lamax-test, O2max-test and the body weight were used to calculate PMLSS for all subjects. The participants did not participate in any other training sessions during the study. Furthermore they were asked to maintain their common nutrition.

To test the maximum glycolytic rate a sprint test with 15 seconds duration was performed according to literature [7]. Subjects were sitting on the cycle ergometer and had a warming up of 12 minutes pedaling at a power of 1.5 fold of body weight. In the middle of that time a short sprint attempt of five seconds was interposed. The warm-up was followed by 10 min cycling at 50 W. Directly after finishing warm-up, two blood samples were obtained from the earlobe in order to measure lactate concentration before the test (LaPre).

Thereafter the sprint test started from the rest and the subjects had to accelerate as fast as possible to a speed of 130 revolutions per minute (rpm). At this speed the automatic breaking power of the cycle ergometer holded the rpm constant resulting in an isokinetic modus. After 15 seconds (ttest) of maximum sprint the automatic braking power reduced speed to 40 rpm and therefore the test was stopped immediately. Athletes were motivated during the 15 seconds at their limit by loud encouragement shouts. At the end of the sprint and at every minute until the end of the 9th minute a blood sample was taken to assess the maximum blood lactate concentration after maximum exertion (LamaxPost).

The maximal lactate production rate was calculated from LaPre, LamaxPost, alactic time interval (talac), and ttest using the following equation 1:

| 1 |

equation 1: Calculation of maximal glycolytic rate (according to [7, 8, 10])

Abbreviations are as follows: LamaxPost = maximal post exercise bloodlactate, LaPre = bloodlactate before test, ttest = test duration (15 s), talac = alactic time interval

The talac was defined as the time from the beginning of the sprint (0 s) to when the maximum power (PW) decreases by 3.5%.

To access O2max a ramp test was performed using a modified protocol published by Craig et al. [11]. Oxygen consumption (O2) and carbon dioxide production ( CO2) were measured breath-by-breath using an Oxycon PRO (Erich Jäger, Höchberg, Germany). After 10 minutes warming up at a constant power of 1.5 fold of the participant's body-weight, followed by a period of 2 minutes at constant load of 50 W. The workload at the beginning of the test was set to 50 W for 2 min and was increased by 25 W every 30 s. The test was finished when subjects reached physically exhaustion, complaints of shortness of breath, dizziness or other physical complaints that unabled them proceeding the test [12].

If exertion could be confirmed, the maximum oxygen consumption was averaged from the highest 30 seconds [13].

Calculated power of maximal lactate steady state

According to Mader and Heck [5, 10] as well Mader [6] and Hauser et al. [7] the results of Lamax-test, O2max-test and the body weight were used to calculate the MLSS for all subjects. The ten equations used for PMLSS are explained in detail in reference [7].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) Version 17.0. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Furthermore minimum (min) and maximum (max) values are shown.

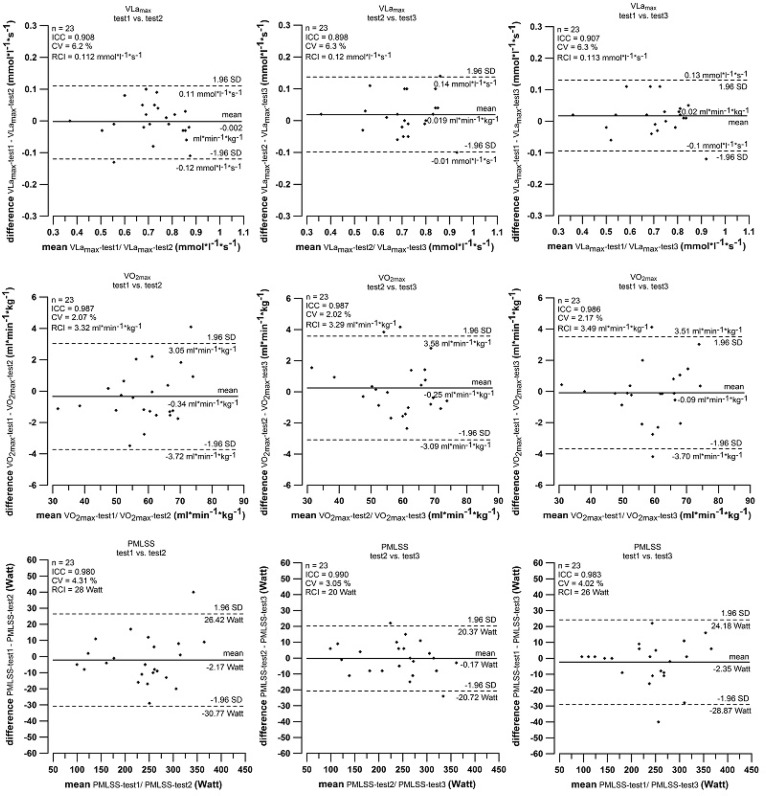

For the analysis of reliability we used the absolute values [root mean square error (RMSE) of an ANOVA [14]], coefficient of variation (CV) calculated based on the RMSE [14–16] and reliable change index (RCI) [17]. An unadjusted two-way random intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC 2.1) [18] was calculated, if values showed a normal distribution, variance homogenicity and additivity. An ICC close to 1 indicates ‘excellent’ reliability. The Bland and Altman Plots of Lamax, O2max and PMLSS were depicted with the graphing program Grapher (Golden Software, Golden, USA, version 7).

RESULTS

All measured parameters of Lamax, the O2max and the PMLSS of all subjects at the first, second and third test day are presented in Table 1. All parameters used to calculate Lamax (LaPre, LamaxPost, the difference of LamaxPost and LaPre (Ladiff), talac and PW showed a reasonable reliability according to an ICC between 0.804 and 0.891 (Table 2), resulting in an ICC of Lamax of 0.904. With an RMSE of 0.045 mmol·l -1s -1 the mean value of Lamax of the study group is 0.71 ± 0.088 mmol·l -1s -1. The RCI for inter- and intraindividual measurements of Lamax is 0.11 mmol·l -1s -1 assumed a significant difference between two measurements with an expected CV of 6.3%. Looking for intraindividual changes seven of our 23 subjects showed significant differences (difference ≥ 0.11 mmol·l -1s -1) of Lamax within the three test days (Figure 1).

TABLE 1.

Results of maximum metabolic performance tests.

| n = 23 | test1 | test2 | Test3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± sd | min – max | mean ± sd | min – max | mean ± sd | min – max | |

| Lamax[mmol·l−1s−1] | 0.72 ± 0.13 | 0.37 - 0.87 | 0.72 ± 0.14 | 0.37 - 0.87 | 0.70 ± 0.14 | 0.35 - 0.98 |

| LaPre[mmol·l−1s−1] | 1.05 ± 0.41 | 0.51 - 2.18 | 1.09 ± 0.50 | 0.51 - 2.83 | 1.01 ± 0.41 | 0.61 - 2.58 |

| LamaxPost[mmol·l−1s−1] | 8.8 ± 1.54 | 4.55 - 10.98 | 8.54 ± 1.54 | 4.63 - 11.02 | 8.47 ± 1.68 | 4.37 - 12.38 |

| Ladiff[mmol·l−1] | 7.54 ± 1.49 | 4.04 - 9.94 | 7.45 ± 1.58 | 4.03 - 10.15 | 7.46 ± 1.63 | 3.76 - 11.12 |

| talac[s] | 4.53 ± 0.84 | 3.25 - 6.25 | 4.40 ± 0.75 | 3.25 - 6.53 | 4.35 ± 0.72 | 3.25 - 6.16 |

| PW[W] | 848 ± 202 | 461 - 1144 | 865 ± 207 | 471 - 1279 | 870 ± 207 | 527 - 1212 |

| O2max[ml·kg−1min−1] | 58.7 ± 10.9 | 31.0 - 75.4 | 59.0 ± 10.4 | 32.2 - 73.5 | 58.8 ± 10.7 | 30.6 - 74.1 |

| PMLSS[W] | 236 ± 74 | 97 - 369 | 238 ± 72 | 102 - 360 | 238 ± 74 | 96 - 363 |

Note: Ladiff - LamaxPost minus LaPre, LamaxPost - maximal post exercise bloodlactate, LaPre - bloodlactate before test, max - maximum, min - minimum, PMLSS - power in maximal lactate steady state, PW - maximum physical power, SD - standard deviation, talac - alactic time interval, Lamax - maximum glycolytic metabolic performance, O2max - maximum oxygen consumption at maximum load

TABLE 2.

Parameters of reliability.

| n = 23 | ICC | RCI | RMSE | CV [%] | -1.96* RMSE | < mean ≤ | +1.96* RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamax[mmol·l−1s−1] | 0.904 | 0.11 | 0.045 | 6.3 | 0.62 | 0.71 | 0.80 |

| LaPre[mmol·l−1s−1] | 0.804 | 0.54 | 0.20 | 18.8 | 0.66 | 1.05 | 1.44 |

| LamaxPost[mmol·l−1s−1] | 0.856 | 1.64 | 0.58 | 6.8 | 7.41 | 8.54 | 9.67 |

| Ladiff[mmol·l−1] | 0.891 | 1.41 | 0.52 | 7.0 | 6.45 | 7.48 | 8.51 |

| talac[s] | 0.881 | 0.73 | 0.25 | 5.8 | 3.93 | 4.43 | 4.93 |

| PW [W] | 0.963 | 108 | 39 | 4.5 | 785 | 861 | 937 |

| O2max[ml·kg−1min−1] | 0.987 | 3.32 | 1.25 | 2.1 | 56.37 | 58.81 | 61.25 |

| PMLSS [W] | 0.985 | 24 | 9 | 3.9 | 219 | 237 | 255 |

Note: CV - coefficient of variation, ICC - intraclass correlation coefficient, Ladiff - LamaxPost minus LaPre, LamaxPost - maximal post exercise bloodlactate, LaPre - bloodlactate before test, PMLSS - power in maximum lactate steady state, PW - maximum physical power, RCI - reliable change index, RMSE - root mean square error, talac - alactic time interval, Lamax - maximum glycolytic metabolic performance, O2max - maximum oxygen consumption at maximum load

FIG. 1.

Bland-Altman plots

CV - coefficient of variation, ICC - Intraclass correlation coefficient, PMLSS - power in maximal lactate steady state, RCI - reliable change index, Lamax - maximum glycolytic metabolic performance, O2max - maximum oxygen consumption at maximum load

In an analogous manner the O2max were analyzed. The mean of all measurements was 58.81 ± 10.5 mlkg -1min -1 with a RMSE of 1.25 mlkg -1min -1. The ICC of O2max was 0.987. Looking for intraindividual changes three of our 23 subjects showed significant differences of O2max within the three test days (Figure 1). The RCI for inter- and intraindividual measurements was 3.3 mlkg -1min -1 with a CV of 2.1%

For all subjects at all test days the aerobic endurance physical performance was calculated, at which the PMLSS was expected (Table 1 and Table 2) using the results of Lamax, O2max and body weight, that was in mean 237 ± 72 W. The simulated performance was with an ICC of 0.985 highly reliable. A RMSE of 9 W was calculated resulting in a confidence interval of 237 ± 18 W. Therefore the mean variance is 3.9%. A significant difference between two measurements develops from RCI of 24 W. Two of our 23 subjects showed significant differences of PMLSS within the three test days (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

The maximal lactate production rate represents the highest performance of the glycolysis. It can be approximated by the quotient of blood lactate difference (LamaxPost minus LaPre) and test duration minus alactic time interval based on a sprint test lasting 15 s [4, 8]. The approximation of Lamax is not established within sports medicine performance analysis. To our knowledge the current study is the first to concerning the reliability of Lamax.

All parameters used to calculate Lamax had a reasonable reliability according to an ICC ranged from 0.804 to 0.891, resulting in an ICC of Lamax of 0.904. These data indicate a high reliability of Lamax. LaPre undulated most but was still reliable. Causes for undulating lactate values are e.g. differences in food and training habits or adaption to physical stress [19]. Carbon hydrate rich diet facilitates the production of energy from carbon hydrates and results in an elevated blood lactate concentration in rest as well as in exertion [20, 21]. The uptake of carbon hydrates two hours before a test also results in a higher maximal lactate production rate in competitive and amateur athletes and could therefore influence the reliability of Lamax [22]. Therefore all subjects were asked to eat a balanced diet and to avoid additional hard training sessions one day prior the test. Although eating habits and activities before the test days were not standardized and remained under each individuals care the high reliability of Lamax is impressive. This may underscore the usefulness of Lamax assessment under common daily circumstances.

An important variable for the calculation of the Lamax is the test duration [8, 23]. Reduction of test duration might lead to a higher maximal lactate production rate [8]. However, this was not be empirically confirmed yet. It must be mentioned that the alactic time interval has an influence on Lamax, too. De Marées [24] and Heck and Schulz [8] postulated that during a test duration of 10 s the alactic time interval lasts about 3 s and during a test duration of 20 s it increases to 4 s. In the equation to calculate Lamax the talac becomes only important in very short load periods. The test duration in the present study was 15 s and therefore long enough to minimize effects of talac.

Measurement of O2max showed with 2.1% variance a higher reproducibility than in earlier studies where reliability was 4% to 10% [25–28]. Comparable to the maximal lactate production rate the O2max is dependent on food habits and fitness level. Furthermore motivation for maximum exertion is not always stable and depends on the psycho-physical well-being and other influencing factors [29]. For the three subjects with significant differences of O2max between the tests these factors have to be discussed. However as only three of 23 showed significant intra-individual differences, the ICC of 0.987 is highly reliable.

The reliability of the predicted performance level at the maximum lactate steady state is dependent on the reproducibility of the predicting variables. The calculated PMLSS was with 0.985 highly reliable. The intra-individual shifts of MLSS are especially dependent on Lamax, O2max and body weight. Hauser et al. [7] tested the mathematical model and the experimental power in maximal lactate steady state during cycling. They described a difference of 12 ± 24 W between calculated prediction and empiric measurement. The calculated endurance performance limit was stringently higher. The authors supposed that lactate production rate and constants in the model were the main influencing factors. In our study we were able to show that Lamax has the lowest reliability of all parameters.

Therefore we conclude that the used sprint test method should be optimized in future especially for amateur sportsmen to minimize influences of lactate e.g. by decreasing work load in the warming-up period, prolonging this period or shortening sprint time to 10 seconds. This should be investigated in further studies.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the results of the present investigation the assessment of LAmax and O2max via a sprint and a ramp test, and the PMLSS calculated from these two parameters and the body weight are highly reliable in amateur cyclists. The method proves suitable for determine training schedules. The transfer to practice has to be evaluated in further studies.

Acknowledgements

Funding: The publication costs of this article were founded by the German Research Foundation/DFG (Geschäftszeichen INST 270/219-1) and the Chemnitz University of Technology in the funding programme Open Access Publishing.

The authors would like to thank Steffi Hallbauer for their assistance in the laboratory and Scott Bowen for his help on the preparing manuscript.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beneke R. Anaerobic threshold, individual anaerobic threshold, and maximal lactate steady state in rowing. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(6):863–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heck H, Mader A, Hess G, Mücke S, Müller R, Hollmann W. Justification of the 4-mmol/l lactate threshold. Int J Sports Med. 1985;6(3):117–130. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1025824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hauser T, Adam J, Schulz H. Comparison of selected lactate threshold parameters with maximal lactate steady state in cycling. Int J Sports Med. 2014;35(6):517–521. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1353176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleicher A, Mader A, Mester J. Zur Interpretation von Laktatleistungskurven-experimentelle Ergebnisse mit computergestützten Nachberechnungen. Spectrum der Sportwissenschaft. 1998;1:92–104. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mader A, Heck H. A Theory of the Metabolic Origin of ”Anaerobic Threshold”. Int J Sports Med. 1986;07(1):45–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mader A. Glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation as a function of cytosolic phosphorylation state and power output of the muscle cell. Eur J App Physiol. 2003;88(4-5):317–338. doi: 10.1007/s00421-002-0676-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauser T, Adam J, Schulz H. Comparison of calculated and experimental power in maximal lactate-steady state during cycling. Theor Biol Med Model. 2014;11(1):25. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-11-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heck H, Schulz H. Diagnostics of anaerobic power and capacity. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 2002;53(7-8):202–212. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harriss DJ, Atkinson G. Ethical standards in sport and exercise science research: 2014 update. Int J Sports Med. 2013;34(12):1025–1028. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1358756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mader A, Heck H. Energiestoffwechselregulation, Erweiterungen des theoretischen Konzepts und seiner Begründungen. Nachweis der praktischen Nützlichkeit der Simulation des Energiestoffwechsels. In: Mader A, editor. Brennpunktthema Computersimulation: Möglichkeiten zur Theoriebildung und Ergebnisinterpretation. Sankt Augustin: Academia Verlag Richarz; 1996. pp. 124–162. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craig N, Walsh C, Martin DT, Woolford S, Bourdon P, Stanef T, Barnes P, Savage B. Protocols for the Physiological Assesment of High-Performance Track, Road and Mountain Bike Cyclist. In: Gore CJ, editor. Physiological tests for elite athletes. Champaign III: Human Kinetics; 2000. pp. 258–277. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mader A, Liesen H, Heck H, Phillipi H, Rost R, Schürch P, Hollmann W. Zur Beurteilung der sportartspezifischen Ausdauerleistungsfähigkeit im Labor. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 1976;27:109–112. 80-88. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robergs RA, Roberts SO. Exercise physiology. Exercise performance and clinical applications. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atkinson G, Nevill AM. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med. 1998;26(4):217–238. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199826040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bland JM, Altman DG. Measurement error proportional to the mean. BMJ. 1996;313(7049):106. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7049.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quan H, Shih WJ. Assessing repro-ducibility by the within-subject coefficient of variation with random effects models. Biometrics. 1996;52(4):1195–1203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59(1):12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajaratnam N. Reliability formulas for independent decision data when reliability data are matched. Psychometrika. 1960;25:261–271. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofmann P, Wonisch M, Pokan R. Laktatleistungsdiagnostik-Durchführung und Interpretation. In: Pokan R, editor. Kompendium der Sportmedizin. Physiologie Innere Medizin und Pädiatrie. Wien: Springer; 2004. pp. 103–132. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Havemann L, West SJ, Goedecke JH, Macdonald IA, St Clair Gibson A, Noakes TD, Lambert EV. Fat adaptation followed by carbohydrate loading compromises high-intensity sprint performance. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100(1):194–202. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00813.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmann P, Lamprecht M, Schwaberger G, Pokan R, Duvillard SP. Einfluss unterschiedlicher Diätformen auf die Laktatleistungskurve im Stufentest und das Laktatverhalten bei Dauerbelastung auf dem Fahrradergometer. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 1998;59(3):82–87. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mikulski T, Ziemba A, Nazar K. Influence of body carbohydrate store modification on catecholamine and lactate responses to graded exercise in sedentary and physically active subjects. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59(3):603–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hauser T. Einfluss der Belastungsdauer bei Sprintbelastungen auf die Laktatbildungsrate. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 2009;60(7-8):177. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marées H. 9th ed. Köln: Sport und Buch Strauß; 2002. Sportphysiologie. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Figueroa-Colon R, Hunter GR, Mayo MS, Aldridge RA, Goran MI, Weinsier RL. Reliability of treadmill measures and criteria to determine VO2max in prepubertal girls. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(4):865–869. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200004000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shephard RJ, Rankinen T, Bouchard C. Test-retest errors and the apparent heterogeneity of training response. Eur J App Physiol. 2004;91(2-3):199–203. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-0990-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skinner JS, Wilmore KM, Jaskolska A, Daw EW, Rice T, Gagnon J, Leon AS, Wilmore JH, Rao DC, Bouchard C. Reproducibility of maximal exercise test data in the HERITAGE family study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(11):1623–1628. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199911000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welsman J, Bywater K, Farr C, Welford D, Armstrong N. Reliability of peak VO(2) and maximal cardiac output assessed using thoracic bioimpedance in children. Eur J App Physiol. 2005;94(3):228–234. doi: 10.1007/s00421-004-1300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kindermann W. Anaerobe Schwelle. Dtsch Z Sportmed. 2004;55(6):161–162. [Google Scholar]