Abstract

Background

Patients with bipolar disorder are exceptionally challenging to manage because of the dynamic, chronic, and fluctuating nature of their disease. Typically, the symptoms of bipolar disorder first appear in adolescence or early adulthood, and are repeated over the patient's lifetime, expressed as unpredictable recurrences of hypomanic/manic or depressive episodes. The lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder in adults is reported to be approximately 4%, and its management was estimated to cost the US healthcare system in 2009 $150 billion in combined direct and indirect costs.

Objective

To review the published literature and describe the personal and societal burdens associated with bipolar disorder, the impact of delays in accurate diagnosis, and the evidence for the clinical effectiveness of available pharmacologic therapies.

Methods

The studies in this comprehensive review were selected for inclusion based on clinical relevance, importance, and robustness of data related to diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder. The search terms that were initially used on MEDLINE/PubMed and Google Scholar were restricted to 1994 through 2014 and included “bipolar disorder,” “mania,” “bipolar depression,” “mood stabilizer,” “atypical antipsychotics,” and “antidepressants.” High-quality, recent reviews of major relevant topics were included to supplement the primary studies.

Discussion

Substantial challenges facing patients with bipolar disorder, in addition to their severe mood symptoms, include frequent incidence of psychiatric (eg, anxiety disorders, alcohol or drug dependence) and general medical comorbidities (eg, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, migraine, and hepatitis C virus infection). It has been reported that more than 75% of patients take their medication less than 75% of the time, and the rate of suicide (0.4%) among patients with bipolar disorder is more than 20 times greater than in the general US population. Mood stabilizers are the cornerstone of treatment of bipolar disorder, but atypical antipsychotics are broadly as effective; however, differences in efficacy exist between individual agents in the treatment of the various phases of bipolar disorder, including treatment of acute mania or acute depression symptoms, and in the prevention of relapse.

Conclusion

The challenges involved in managing bipolar disorder over a patient's lifetime are the result of the dynamic, chronic, and fluctuating nature of this disease. Diligent selection of a treatment that takes into account its efficacy in the various phases of the disorder, along with the safety profile identified in clinical trials and in the real world can help ameliorate the impact of this devastating condition.

Bipolar disorder is a chronic, relapsing illness characterized by recurrent episodes of manic or depressive symptoms, with intervening periods that are relatively (but not fully) symptom-free. Onset occurs usually in adolescence or in early adulthood, although onset later in life is also possible.1 Bipolar disorder has a lifelong impact on patients’ overall health status, quality of life, and functioning.2

This disorder has 2 major types—bipolar disorder I and bipolar disorder II.3 Bipolar disorder I is defined by episodes of depression and the presence of mania, whereas bipolar disorder II is characterized by episodes of depression and hypomania. Therefore, the main distinction between the 2 types is the severity of manic symptoms: full mania causes severe functional impairment, can include symptoms of psychosis, and often requires hospitalization; hypomania, by contrast, is not severe enough to cause marked impairment in social or occupational functioning, or to necessitate hospitalization.3

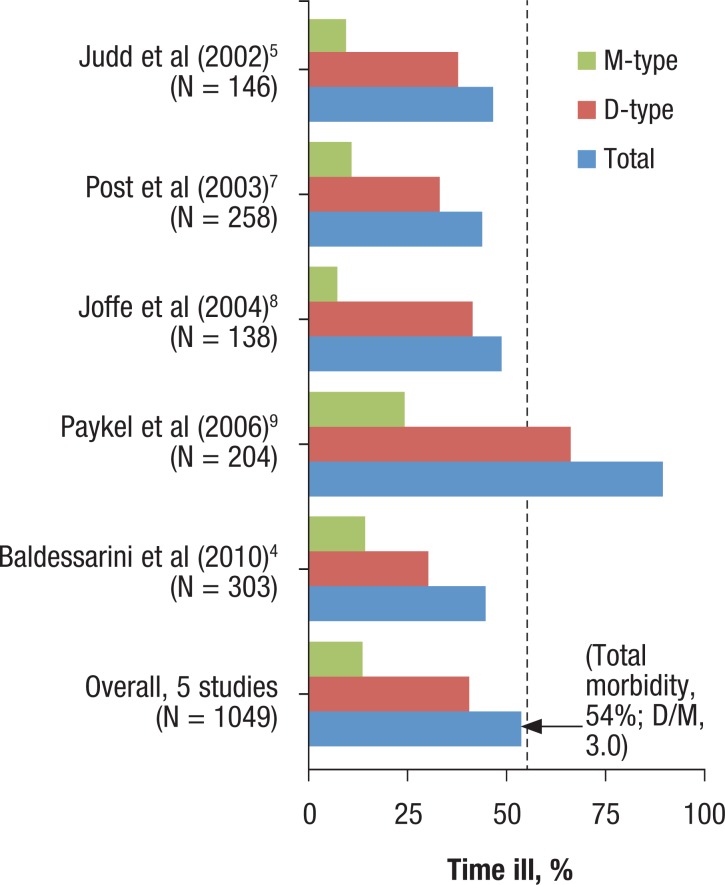

Longitudinal studies show that patients with bipolar disorder of either type experience symptomatic depression at least 3 times more frequently than symptomatic mania or hypomania (Figure 1).4–9 The lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder in adults in the United States is reported to be 3.9%.10

Figure 1. Total Time Ill in First 2 Years After the Index Episode.

M-type: mania, hypomania, psychosis; D-type: depression, dysthymia, dysphoric mixed states.

Reprinted with permission from Baldessarini RJ, Salvatore P, Khalsa H-M, et al. Morbidity in 303 first-episode bipolar I disorder patients. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:264–270.

KEY POINTS

-

▸

Bipolar disorder is a dynamic and serious condition that can have a lifelong impact on a patient's overall health status, quality of life, and functioning.

-

▸

The treatment of bipolar disorder is challenging and costs the US healthcare system an estimated >$30 billion in direct expenditures and >$120 billion in indirect costs annually.

-

▸

Delayed diagnosis can result in worsening clinical outcomes and increased costs; early recognition of this condition can reduce the total per-patient costs by as much as $2316 annually.

-

▸

Considering the possibility of bipolar disorder in patients with depressive disorders is critical to improving outcomes and reducing costs of treatment.

-

▸

Despite the introduction of new therapies for bipolar disorder, treatment outcomes remain less successful than for major depressive disorder; the use of antidepressants for this condition remains controversial.

-

▸

Medication nonadherence is perhaps the most significant contributor to poor outcomes in this patient population; monotherapy may help improve adherence in some patients.

-

▸

The selection of an appropriate treatment that takes into account efficacy as well as safety can help to ameliorate the devastating impact of bipolar disorder.

Bipolar disorder has an enormous economic impact on the US healthcare system.11,12 The estimated total direct cost of bipolar disorder (including inpatient costs, outpatient costs, pharmaceuticals, and community care) in the United States in 2009 was $30.7 billion.11 In addition, the adverse impact of bipolar disorder on functioning and quality of life translates to a substantial total indirect healthcare cost resulting from the loss of employment, loss of productivity, sick leave,13 and uncompensated care that is estimated at more than $120 billion annually.11

From a managed care perspective, bipolar disorder is among the most costly of all mental health conditions. In a major study of commercial insurance claims data from 1996 of almost 1.7 million individuals, although only 3% of patients with a mental health claim were identified with bipolar disorder, these patients accounted for 12.4% of the total plan expenditures.14 High cost was driven largely by a disproportionate rate of inpatient admissions for bipolar disorder versus all other behavioral health claimants (39.1% vs 4.5%, respectively), resulting in a cost of $1.80 for inpatient care per every dollar of outpatient treatment cost.14

Another large study of healthcare utilization and costs from 2004 to 2007 compared 122 patients with bipolar disorder with patients with other psychiatric conditions, including 1290 patients with depression, 2770 with asthma, 1759 with coronary artery disease, and 1418 with diabetes.12 The patients with bipolar disorder had higher adjusted mean costs per member per month (approximately $1700) than all other groups, including depression (approximately $1300), with the exception of patients who had both diabetes and coronary artery disease (with approximately $2000 per member per month).12

Despite the advent of lithium therapy more than 60 years ago,15 the introduction of other pharmacotherapies and the development of disease-specific behavioral approaches,16 and a generally greater awareness of bipolar disorder, treatment outcomes remain less satisfactory than the outcomes for major depressive disorder (MDD) in all sectors of the US healthcare system, including managed care.2 This represents a challenge and an opportunity for managed care to focus on this disorder to improve outcomes and to reduce healthcare costs.

This review article presents the clinical evidence supporting best practice for the diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder. The review highlights what little is known about the most effective ways to address specific clinical challenges in caring for patients with bipolar disorder and identifies recent research that documents innovative approaches to improving the effectiveness of care in this setting.

Study Selection Methodology

Studies were selected for inclusion in this review based on a comprehensive literature search initially using MEDLINE/PubMed and Google Scholar, and was restricted to the years 1994 to the present. The search terms included “bipolar disorder,” “mania,” “bipolar depression,” “mood stabilizer,” “atypical antipsychotics,” and “antidepressants.” For the sections on diagnosis, treatment, and key challenges, articles were selected for inclusion from the extensive literature based on the clinical judgment of the author, using the conventional criteria of relevance, importance, and robustness of data. In selecting studies for inclusion, a broad representation of topics was sought, while limiting the total number of references on any given topic; high-quality, recent reviews of major topics were included to supplement the primary studies.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of bipolar disorder is obvious when a patient presents with florid mania but is challenging when the initial presentation includes depressive symptoms; studies generally report that 50% or more of patients initially present with depression.3,17–20 Primarily because unipolar depression (ie, MDD) is more common than bipolar depression, and because bipolar depression lacks pathognomonic features, bipolar disorder is often incorrectly identified as MDD.21 Among patients who are eventually diagnosed with bipolar disorder, approximately 70% reportedly had an initial misdiagnosis and more than 33% remained misdiagnosed for 10 years or more.22 Delay in diagnosis is a particular problem in women with bipolar disorder type II, because the symptoms of hypomania may not be very apparent.23 Moreover, misdiagnosis during the postpartum period is common; in a study of 56 women referred for postpartum depression, 54% were later rediagnosed with bipolar disorder.24

The delayed recognition of bipolar disorder has adverse clinical and healthcare cost consequences.21,25,26 From a clinical perspective, patients with bipolar disorder who are treated with antidepressants alone (the standard of care for MDD) are less likely to have an appropriate response and are at risk for manic switch or cycle acceleration (ie, increased frequency of mood episodes over time).27,28

From a health economic perspective, care is likely to be more costly in patients with delayed diagnosis of bipolar disorder than in those diagnosed early. In an analysis from the California Medicaid program, 2 groups of patients with bipolar disorder were compared: those who were diagnosed with bipolar disorder at initial presentation and those who had a delayed diagnosis during a 6-year follow-up.26 Patients with a delayed diagnosis of bipolar disorder represented almost twice as many cases as those with initially recognized bipolar disorder (28.2% vs 14.5%, respectively), and the annualized total cost per patient in the delayed group was $2316 higher in the sixth year compared with the cost for patients whose disease was initially recognized as bipolar disorder (P <.001). Moreover, costs for patients with bipolar disorder and a delayed diagnosis increased by $10 monthly before the correct diagnosis (P <.001) and decreased by $1 afterward (P = .006 for the change in slope).26 Thus, the consideration of the possibility of bipolar disorder in patients with depressive disorders is critical to improving outcomes and reducing the costs of care of patients with bipolar disorder.

Screening each patient for a history of mania and hypomania on their initial presentation of depressive symptoms is an early step toward the recognition of bipolar disorder.29 Validated instruments that can be used include the Mood Disorder Questionnaire,30 the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 3.0,31 and the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders Patient Health Questionnaire.32 Clinical screening can be supplemented with electronic health record (EHR)-based case findings, in which information collected by self-report or a healthcare assistant is entered into the EHR and is screened for possible indicators of bipolar disorder.33

These tools help to ensure that the clinician recognizes patients who are more likely to have bipolar disorder, help assist in directing the clinical interview, and can encourage active follow-up for any emerging symptoms of bipolar disorder. In a study modeling the clinical outcome and cost-effectiveness over 5 years of administering the Mood Disorder Questionnaire to all patients first presenting with symptoms of MDD, screening resulted in an increase in diagnostic accuracy for bipolar disorder, with an additional 38 cases identified per 1000 patients screened and a per-patient savings of $1937, for a total annual budgetary savings of more than $1.9 million.34

Pharmacologic Treatment

Pharmacologic treatments for bipolar disorder include the conventional mood stabilizers (eg, lithium, valproate, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine) and most of the currently marketed atypical antipsychotics.2,21 A detailed review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies for every agent in the treatment of each of the phases of bipolar disorder is beyond the scope of this review; rather, a summary of the most important findings of the aggregated evidence is presented from systematic reviews and meta-analyses,15,35 as well as the results of recent studies that address previous gaps in the literature.36,37

It is relevant to note that the level of trial evidence varies for the different pharmacotherapies that are approved for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Some of these agents have evidence of efficacy in acute mania, others in acute bipolar depression, and a limited number of therapies have efficacy at both poles of the disease spectrum. Some therapies demonstrate efficacy only in acute episodes, whereas others show efficacy as maintenance therapy.

Mood Stabilizers

Lithium has been the foundation of treatment of bipolar disorder for over 60 years,2,15,38 but its efficacy in the prevention and treatment of bipolar depression is limited, and it is not rapidly effective for acute mania.15 In a systematic review of RCTs with a lithium arm that were published between 1970 and 2006, lithium had a significant prophylactic effect for all relapses (random effects relative risk [RR], 0.65; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.50–0.84) and manic relapses (RR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.40–0.95) but not for depressive relapses (RR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.49–1.07).15 Notably, lithium remains the only agent proved to reduce the risk for suicide in patients with bipolar disorder.39

Sodium valproate is the most frequently used antiepileptic mood stabilizer for patients with bipolar disorder. In the BALANCE trial, a 2-year active controlled trial, 330 patients were receiving maintenance therapy with lithium or valproate, or the combination of both; the primary outcome was time to first mood episode.40 Although the combination performed best, lithium was more effective than valproate alone (hazard ratio [HR] for the primary outcome, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.51–1.00; P = .047).40

A nationwide observational study conducted in Denmark from 1995 to 2006 of 4268 patients who received lithium or valproate for the treatment of bipolar disorder found a higher rate of adding medications or switching to another drug among patients receiving valproate compared with lithium (HR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.59–2.16) and a higher rate of hospitalization (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.18–1.48).41

Lamotrigine is the mood stabilizer with the best evidence for bipolar depression prophylaxis.28 Published data on the use of lamotrigine for acute depression in patients with bipolar disorder are inconsistent, but a meta-analysis did find significant efficacy for a higher dose of 200 mg/day.28,42

Each of the mood stabilizers presents significant safety issues. Lithium has a narrow therapeutic window that leads to the requirement for regular monitoring of serum concentrations; it can be fatal in overdose, and is associated with progressive renal insufficiency and hypothyroidism.21,43 Valproate is associated with hepatotoxicity, whereas lamotrigine is linked with rash and Stevens-Johnson–like syndrome.21,44,45 Valproate and lithium are both teratogenic.46

Atypical Antipsychotics

A vast body of evidence supports the use of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of bipolar disorder.35 The most established role for this class is in the treatment of acute mania. All approved atypical antipsychotics (with the exception of lurasidone) have been shown to be effective in the treatment of manic episodes of bipolar disorder I.35 In contrast, only quetiapine (immediate-release and extended-release formulations) has the highest level (level 1) of evidence for efficacy as monotherapy for bipolar I or II depression.35 More recently, quetiapine was also shown to reduce the symptoms of depression in acute mixed episodes of bipolar II hypomania.36 One single trial of the combination agent of olanzapine and fluoxetine shows the efficacy of this agent in bipolar I depression28; lurasidone was approved in 2013 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of adults with bipolar I depression.47 Other atypical antipsychotics, including aripiprazole, have not shown efficacy in trials of patients with bipolar depression.48

The safety and tolerability of atypical antipsychotics are well characterized in the literature.49,50 The adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics differ between individual agents. In a meta-analysis of 48 RCTs in which at least 2 atypical antipsychotics were compared and risperidone served as the index medication, weight gain was significantly increased with olanzapine (odds ratio [OR], 2.139; 95% CI, 1.764–2.626) and was decreased with ziprasidone (OR, 0.466; 95% CI, 0.317–0.657); extrapyramidal symptoms were decreased with quetiapine (OR, 0.441; 95% CI, 0.129–0.910).50

Atypical antipsychotics as a class have a propensity to contribute to metabolic risk in patients with bipolar disorder, and monitoring strategies have been proposed to prevent, minimize, or detect symptoms early so that appropriate measures can be taken.49

Antidepressants

The use of antidepressants as pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder is the area of greatest controversy related to this disease.27,51 In a random-effects meta-analysis of 10 studies that included 2226 patients with unipolar depression and 863 patients with bipolar disorder, antidepressant responses did not differ between the 2 groups (pooled RR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.96–1.15; P = .34).51 However, the risk rate for a switch to mania was 2.5% weekly in patients with bipolar depression compared with 0.28% in patients with unipolar depression.

Antidepressants are not FDA-approved for the treatment of bipolar disorder, with the exception of fluoxetine in combination with olanzapine, although antidepressants are frequently prescribed in clinical practice for the depressive symptoms of bipolar disorder.

The current guidelines21,38,52 are generally consistent in making the recommendations listed in the Table regarding antidepressant use in bipolar depression, indicating that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (other than paroxetine) and bupropion may be used as first-line treatments in patients with bipolar disorder with no history of rapid cycling and without concomitant manic symptoms, but always in conjunction with a mood stabilizer or an atypical antipsychotic. Antidepressants should be tapered and discontinued after full remission of depression; the role of antidepressants in maintenance treatment is unclear.27,28

Table.

Guideline Recommendations for the First-Line Treatment of Bipolar Disorder

| Guideline | Acute treatment | Maintenance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mania | Bipolar depression | Mixed states | Mania | Depression | |||

| VAD/DoD (2010)54 | Lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone | Quetiapine, lamotrigine, lithium | Valproate, carbamazepine, olanzapine, aripiprazole, risperidone, ziprasidone | Agent effective in acute phase; monotherapy advised Lithium, olanzapine; lithium/valproate + quetiapine |

Agent effective in acute phase; monotherapy advised Lithium, lamotrigine; lithium/valproate + quetiapine |

||

| WFSBP (2009, 2010, 2013)55–57 | Aripiprazole, risperidone, valproate, ziprasidone | Bipolar I depression | Bipolar II depression | No specific recommendations | Mania | Depression | Any episode |

| Quetiapine | Quetiapine, lithium/valproate + pramipexole, valproate, antidepressants | Aripiprazole, lithium, quetiapine | Lamotrigine, quetiapine | Aripiprazole, lamotrigine, lithium, quetiapine | |||

| CANMAT (2013)38 | Lithium, valproate, aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, quetiapine XR, risperidone, ziprasidone, asenapine, paliperidone XR, lithium/valproate + aripiprazole, lithium/valproate + olanzapine, lithium/valproate + quetiapine, lithium/valproate + risperidone, lithium/valproate + asenapine | Bipolar I depression | Bipolar II depression | No specific recommendations | Bipolar I disorder | Bipolar II disorder | |

| Lithium, lamotrigine, quetiapine, quetiapine XR, lithium/valproate + SSRI, olanzapine + SSRI, lithium + valproate, lithium/valproate + bupropion | Quetiapine, quetiapine XR | Lithium, lamotrigine (limited efficacy in preventing mania), quetiapine, risperidone LAI, aripiprazole, lithium/valproate + quetiapine, lithium/valproate + risperidone, LAI lithium/valproate + aripiprazole or lithium/valproate + ziprasidone | Lithium, lamotrigine, quetiapine | ||||

| BAP (2009)52 | Mild: lithium, carbamazepine Severe: antipsychotic, valproate |

Bipolar depression | Mild: lithium, carbamazepine Severe: antipsychotic, valproate | Mania | Depression | ||

| Quetiapine, lamotrigine, SSRI or other antidepressant (not TCA) | Lithium, aripiprazole, quetiapine, valproate, olanzapine | Quetiapine, lamotrigine | |||||

| APA (2002)21 | Severely ill: lithium/valproate + antipsychotic Less severely ill: lithium, valproate, antipsychotic | Severely ill: lithium/valproate + antipsychotic Less severely ill: lithium, valproate, antipsychotic | Lithium, lamotrigine | Severely ill: lithium/valproate + antipsychotic Less severely ill: lithium, valproate, antipsychotic | Lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine | ||

LAI indicates long-acting injection; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; XR, extended release.

Treatment Guidelines

Treatment guidelines are a critical source for the rational pharmacotherapy of bipolar disorder.21,52 The American Psychiatric Association guidelines for bipolar disorder have not been updated since 2002, and therefore do not include data that became available more recently.21 In a systematic overview of the current international guidelines for bipolar disorder conducted in 2011, the recommendations with the greatest degree of consensus and best evidence for first-line treatment were the use of (1) lithium, divalproex, or an atypical antipsychotic, for acute mania; (2) divalproex or an atypical antipsychotic, for mixed episodes (ie, manic and depressed symptoms together); (3) quetiapine, olanzapine/fluoxetine combination, or lamotrigine, for bipolar depression; and (4) group or individual psychological education should be offered to all patients with bipolar disorder.53

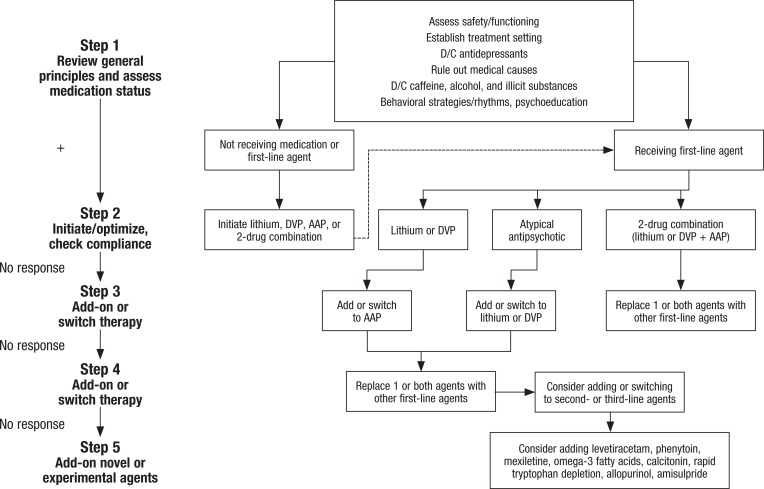

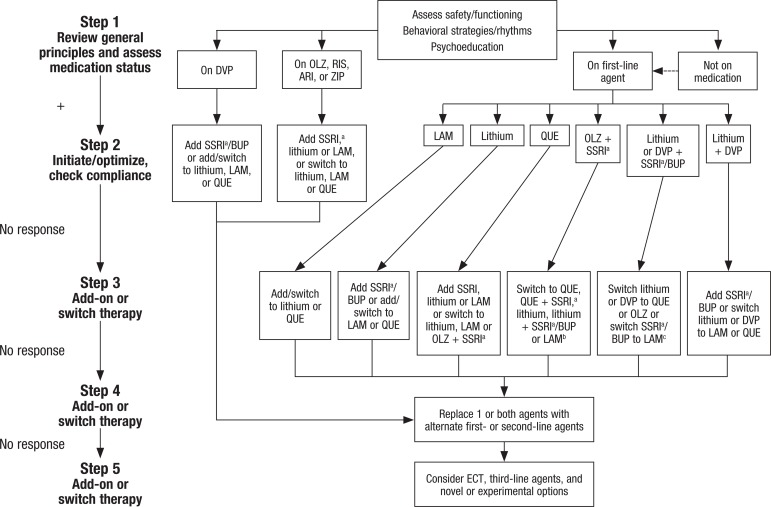

The Table provides a summary of first-line pharmacotherapy recommendations from a selected set of comprehensive guidelines.21,38,52,54–57 However, implementation of the guidance in any treatment algorithm for bipolar disorder is challenging, because of the multiple factors involved in drug selection, drug interactions, adverse side effects, and patient adherence (Figure 2A and Figure 2B).38

Figure 2A. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments Mania Algorithm.

AAP indicates atypical antipsychotic; D/C, discontinue; DVP, divalproex.

Reprinted with permission from Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:1–44.

Figure 2B. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments Bipolar Depression Algorithm.

aExcept paroxetine.

bOr switch the SSRI to another SSRI.

cOr switch the SSRI or BUP to another SSRI or BUP.

ARI indicates aripiprazole; BUP, bupropion; DVP, divalproex; ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; LAM, lamotrigine; OLZ, olanzapine; QUE, quetiapine; RIS, risperidone; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; ZIP, ziprasidone.

Reprinted with permission from Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:1–44.

Major Challenges in the Treatment of Bipolar Disorder

In addition to the importance of implementing an expeditious diagnosis, evidence-based prescribing, and cost-effective therapies, other challenges must be recognized and addressed in the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder to improve treatment outcome.

Treatment Nonadherence

Nonadherence to treatment is perhaps the most significant contributing factor to poor outcome in patients with bipolar disorder.58,59 Medication possession ratio (MPR) has been used to assess treatment adherence. MPR is the ratio of the number of days that an antipsychotic medication, for example, was filled compared with the total number of days during the follow-up period. An MPR of 1 indicates that for a medication prescribed for a patient over a given time, prescriptions were filled 100% of that period. A priori MPR percentage thresholds of 70% to 80% have been set to define adherence versus nonadherence; a threshold of 75% or 80% represents a level of adherence that is associated with better outcomes in patients with bipolar disorder.58–61

In one study with 1973 commercially insured patients, the mean MPR was only 0.46 (SD, ±0.32); patients whose MPR was ≥0.75 had a lower risk for all-cause rehospitalization (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.58–0.92) and mental health–related rehospitalization (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.60–0.96).58 Similarly, among 1399 commercially insured patients, reduced adherence (<80%) to traditional mood-stabilizing therapy was associated with a greater risk for emergency department visits (OR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.38–2.84) and inpatient hospitalizations (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.27–2.32).59

In one of the largest studies of its type, using claims data from the 2000–2006 PharMetrics database (a large US database of commercial health plans), 78.7% of the 7769 patients with bipolar disorder had an MPR <0.75. An MPR ≥0.80 was associated with a reduction in risk for mental health–related hospitalization (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70–0.95), and an MPR ≥0.90 was also associated with a reduction in the risk for a mental health–related emergency department visit (OR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.54–0.91).60 Similar findings have been reported in Medicaid-insured populations.61

Because adherence tends to worsen with the addition of each medication to a pharmacotherapeutic regimen, monotherapy may be considered a practical option in patients with poor adherence.62,63

Psychiatric Comorbidities

Patients with bipolar disorder are predisposed to other comorbid psychiatric disorders at higher rates than patients with other psychiatric disorders.64,65 Anxiety disorders and alcohol or drug dependence are particularly common comorbidities, with major consequences for treatment outcome and increased cost.64,66 Comorbidity is the rule rather than the exception in bipolar disorder,64,65 with approximately 66% of patients having 1 comorbid mental health diagnosis and approximately 66% having 2 other conditions.66

These comorbid psychiatric conditions are associated with longer episodes of bipolar illness64,66; shorter time in remission (ie, euthymia)64,66; polypharmacy, with the potential for drug interactions67; and an increase in related problems, such as poor treatment compliance and suicidality.65

General Medical Comorbidities

Patients with bipolar disorder also have a high rate of other medical comorbidities, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, migraine, and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.66,68 In a Veterans Administration (VA) study, patients with bipolar disorder had a higher prevalence of diabetes than patients in a national VA cohort (17.2% vs 15.6%, respectively; P = .0035) and of HCV (5.9% vs 1.1%, respectively; P <.001).68 Several reasons can potentially account for this increased burden of medical illness, including shared biologic predisposition (eg, migraine), comorbid substance misuse (HCV), as well as adverse effects of treatment (obesity and diabetes).69 Not surprisingly, medical comorbidities are associated with a significant increase in the total cost of care.70,71

Suicide

Suicide is more frequent among patients with bipolar disorder than among patients with any other psychiatric or general medical disorder.72,73 Suicide among patients with bipolar disorder is estimated to occur at an annual rate of 0.4% (1 for every 250 individuals with bipolar disorder), which is more than 20 times than in the general US population.73 In the Epidemiologic Catchment Area database, which is still one of the best US databases regarding the epidemiology of psychiatric disorders, the lifetime rate of suicide attempts for persons with bipolar disorder was 29.2%—almost twice the rates of MDD (15.9%) and other Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition–defined Axis I disorder (4.2%).72

Suicide attempts are very costly.74 In a study using data from the PharMetrics Integrated Outcomes Database (1995–2005), the total costs for 352 patients with bipolar disorder who attempted suicide were compared between the years after and before the first suicide attempt. The mean healthcare cost for the 1 year after the suicide attempt was $25,012 versus $11,476 for the 1 year before (P <.001). During the month after the suicide attempt, a large increase was reported in inpatient and emergency services, followed by enduring long-term increases in medication and outpatient costs.74

Women of Childbearing Age

Women of childbearing age comprise a special population requiring vigilance by caregivers and healthcare providers.75 In a prospective observational study of 89 pregnant women with bipolar disorder who were euthymic at the time of conception, 71% had at least 1 recurrence of a bipolar episode during pregnancy; depression was the most common type of recurrence (38%), followed by mixed states (29%), hypomania (17%), and mania (7%). Those who discontinued pharmacotherapies were at twice the risk for a recurrence as those who continued therapy, had a recurrence earlier, and their illness was almost 5 times as long; abrupt treatment withdrawal posed the greatest risk.75

Given the demonstrated teratogenic risk associated with antiepileptic drugs and with lithium, atypical antipsychotics are an essential treatment option in this vulnerable population.76 Close coordination between obstetric, psychiatric, and primary medical care providers during pregnancy is critical.

Conclusion

The lifetime management of patients with bipolar disorder is challenging, because of the dynamic, chronic, and fluctuating nature of this disease. The healthcare costs for patients and their caregivers are enormous from psychosocial and economic perspectives. It is incumbent on healthcare professionals to reduce the burden of bipolar disorder. Pharmacologic treatment is the mainstay of treatment for patients with bipolar disorder. Although mood stabilizers have been the cornerstone of therapy, the availability of atypical antipsychotics has significantly modified the approach to care. Individual atypical antipsychotic medications have been shown to be effective for acute mania/hypomania, for acute depression, and for maintenance treatment (of mania and depression), and have been incorporated into many treatment guidelines. The diligent selection of a specific agent that takes into account its efficacy in the various phases of bipolar disorder, along with its safety profile, can help to ameliorate the impact of this devastating condition.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support for the preparation of the manuscript was provided by Bill Wolvey of PAREXEL.

Funding Source

Funding for writing this review article was provided by AstraZeneca.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Jann is on the Speaker's Bureau for Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007; 64: 543– 552, Erratum in: Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007; 64: 1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geddes JR, Miklowitz DJ. Treatment of bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2013; 381: 1672– 1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. DSM-5. 5th ed.Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldessarini RJ, Salvatore P, Khalsa H-M, et al. Morbidity in 303 first-episode bipolar I disorder patients. Bipolar Disord. 2010; 12: 264– 270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002; 59: 530– 537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003; 60: 261– 269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Post RM, Denicoff KD, Leverich GS, et al. Morbidity in 258 bipolar outpatients followed for 1 year with daily prospective ratings on the NIMH life chart method. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003; 64: 680– 690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joffe RT, MacQueen GM, Marriott M, Trevor Young L. A prospective, longitutinal study of percentage of time spent ill in patients with bipolar I or bipolar II disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2004; 6: 62– 66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paykel ES, Abbott R, Morriss R, et al. Sub-syndromal and syndromal symptoms in the longitudinal course of bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2006; 189: 118– 123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institutes of Health. National Institute of Mental Health. Statistics. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/bipolar-disorder-among-adults.shtml. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- 11.Dilsaver SC. An estimate of the minimum economic burden of bipolar I and II disorders in the United States: 2009. J Affect Disord. 2011; 129: 79– 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams MD, Shah ND, Wagie AE, et al. Direct costs of bipolar disorder versus other chronic conditions: an employer-based health plan analysis. Psychiatr Serv. 2011; 62: 1073– 1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Chelminski I, et al. Sustained unemployment in psychiatric outpatients with bipolar disorder: frequency and association with demographic variables and comorbid disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2010; 12: 720– 726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peele PB, Xu Y, Kupfer DJ. Insurance expenditures on bipolar disorder: clinical and parity implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2003; 160: 1286– 1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geddes JR, Burgess S, Hawton K, et al. Long-term lithium therapy for bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2004; 161: 217– 222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott J, Colom F. Psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005; 28: 371– 384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Visioli C. First-episode types in bipolar disorder: predictive associations with later illness. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014; 129: 383– 392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daban C, Colom F, Sanchez-Moreno J, et al. Clinical correlates of first-episode polarity in bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2006; 47: 433– 437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perugi G, Micheli C, Akiskal HS, et al. Polarity of the first episode, clinical characteristics, and course of manic depressive illness: a systematic retrospective investigation of 320 bipolar I patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2000; 41: 13– 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suppes T, Leverich GS, Keck PE, Jr, et al. The Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network: II. Demographics and illness characteristics of the first 261 patients. J Affect Disord. 2001; 67: 45– 59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirschfeld RM, Bowden CL, Gitlin MJ, et al. for the work group on bipolar disorder; American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. Second edition April 2002. http://dbsanca.org/docs/APA_Bipolar_Guidelines.1783155.pdf. Accessed April 23, 2013.

- 22.Hirschfeld RMA, Lewis L, Vornik LA. Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we come? Results of a national depressive and manic-depressive association 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003; 64: 161– 174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott J, Leboyer M. Consequences of delayed diagnosis of bipolar disorders. Encephale. 2011; 37 (suppl 3):S173–S175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma V, Khan M, Corpse C, Sharma P. Missed bipolarity and psychiatric comorbidity in women with postpartum depression. Bipolar Disord. 2008; 10: 742– 747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamat SA, Rajagopalan K, Pethick N, et al. Prevalence and humanistic impact of potential misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder among patients with major depressive disorder in a commercially insured population. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008; 14: 632– 642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCombs JS, Ahn J, Tencer T, Shi L. The impact of unrecognized bipolar disorders among patients treated for depression with antidepressants in the fee-for-services California Medicaid (Medi-Cal) program: a 6-year retrospective analysis. J Affect Disord. 2007; 97: 171– 179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghaemi SN, Ostacher MM, El-Mallakh RS, et al. Antidepressant discontinuation in bipolar depression: a Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) randomized clinical trial of long-term effectiveness and safety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010; 71: 372– 380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vieta E, Locklear J, Günther O, et al. Treatment options for bipolar depression: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010; 30: 579– 590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirschfeld RMA. Screening for bipolar disorder. Am J Manag Care. 2007; 13 (7 suppl):S164–S169. Erratum in: Am J Manag Care. 2008; 14: 76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirschfeld RMA. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire: a simple, patient-rated screening instrument for bipolar disorder. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002; 4: 9– 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004; 13: 93– 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB; for the Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study Group. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999; 282: 1737– 1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gill JM, Chen YX, Grimes A, Klinkman MS. Using electronic health record–based tools to screen for bipolar disorder in primary care patients with depression. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012; 25: 283– 290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menzin J, Sussman M, Tafesse E, et al. A model of the economic impact of a bipolar disorder screening program in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009; 70: 1230– 1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Derry S, Moore RA. Atypical antipsychotics in bipolar disorder: systematic review of randomised trials. BMC Psychiatry. 2007; 7: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suppes T, Ketter TA, Gwizdowski IS, et al. First controlled treatment trial of bipolar II hypomania with mixed symptoms: quetiapine versus placebo. J Affect Disord. 2013; 150: 37– 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356: 1711– 1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013; 15: 1– 44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Davis P, et al. Decreased risk of suicides and attempts during long-term lithium treatment: a meta-analytic review. Bipolar Disord. 2006; 8 (5 pt 2):625–639. Erratum in: Bipolar Disord. 2007; 9: 314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geddes JR, Goodwin GM, Rendell J, et al. for the BALANCE investigators and collaborators. Lithium plus valproate combination therapy versus monotherapy for relapse prevention in bipolar I disorder (BALANCE): a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010; 375: 385– 395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kessing LV, Hellmund G, Geddes JR, et al. Valproate v. lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder in clinical practice: observational nationwide register-based cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011; 199: 57– 63, Erratum in: Br J Psychiatry. 2011; 199: 343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geddes JR, Calabrese JR, Goodwin GM. Lamotrigine for treatment of bipolar depression: independent meta-analysis and meta-regression of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2009; 194: 4– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grandjean EM, Aubry J-M. Lithium: updated human knowledge using an evidence-based approach: part III: clinical safety. CNS Drugs. 2009; 23: 397– 418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Powell-Jackson PR, Tredger JM, Williams R. Hepatotoxicity to sodium valproate: a review. Gut. 1984; 25: 673– 681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seo H-J, Chiesa A, Lee S-J, et al. Safety and tolerability of lamotrigine: results from 12 placebo-controlled clinical trials and clinical implications. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011; 34: 39– 47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iqbal MM, Sohhan T, Mahmud SZ. The effects of lithium, valproic acid, and carbamazepine during pregnancy and lactation. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2001; 39: 381– 392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014; 171: 160– 168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thase ME, Jonas A, Khan A, et al. Aripiprazole monotherapy in nonpsychotic bipolar I depression: results of 2 randomized, placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008; 28: 13– 20, Erratum in: J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009; 29: 38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. 2005; 19 (suppl 1):1–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edwards SJ, Smith CJ. Tolerability of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of adults with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: a mixed treatment comparison of randomized controlled trials. Clin Ther. 2009; 31 (pt 1):1345–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vázquez G, Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ. Comparison of antidepressant responses in patients with bipolar vs. unipolar depression: a meta-analytic review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011; 44: 21– 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goodwin GM; for the Consensus Group of the British Association for Pyschopharmacology. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised second edition—recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2009; 23: 346– 388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Connolly KR, Thase ME. The clinical management of bipolar disorder: a review of evidence-based guidelines. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Department of Veterans Affairs; Department of Defense; the Management of Bipolar Disorder Working Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Bipolar Disorder in Adults. May 2010. www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/bd/bd_305_full.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2014.

- 55.Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, et al. for the WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorders. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of bipolar disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013; 14: 154– 219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, et al. for the WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorders. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2010 on the treatment of acute bipolar depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010; 11: 81– 109.20148751 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grunze H, Vieta E, Goodwin GM, et al. for the WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorders. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of bipolar disorders: update 2009 on the treatment of acute mania. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009; 10: 85– 116. Erratum in: World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10:255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hassan M, Lage MJ. Risk of rehospitalization among bipolar disorder patients who are nonadherent to antipsychotic therapy after hospital discharge. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009; 66: 358– 365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lew KH, Chang EY, Rajagopalan K, Knoth RL. The effect of medication adherence on health care utilization in bipolar disorder. Manag Care Interface. 2006; 19: 41– 46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lage MJ, Hassan MK. The relationship between antipsychotic medication adherence and patient outcomes among individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder: a retrospective study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2009; 8: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rascati KL, Richards KM, Ott CA, et al. Adherence, persistence of use, and costs associated with second-generation antipsychotics for bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2011; 62: 1032– 1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burton SC. Strategies for improving adherence to second-generation antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia by increasing ease of use. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005; 11: 369– 378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thase ME. Quetiapine monotherapy for bipolar depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008; 4: 21– 31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of bipolar I disorder and axis I and II disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005; 66: 1205– 1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baldassano CF. Illness course, comorbidity, gender, and suicidality in patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006; 67 (suppl 11):8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, et al. The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1996; 66: 17– 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ, Yatham LN. Comorbidity in bipolar disorder: a framework for rational treatment selection. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004; 19: 369– 386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kilbourne AM, Cornelius JR, Han X, et al. Burden of general medical conditions among individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2004; 6: 368– 373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weber NS, Fisher JA, Cowan DN, Niebuhr DW. Psychiatric and general medical conditions comorbid with bipolar disorder in the National Hospital Discharge Survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2011; 62: 1152– 1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guo JJ, Keck PE, Jr, Li H, et al. Treatment costs and health care utilization for patients with bipolar disorder in a large managed care population. Value Health. 2008; 11: 416– 423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kasteng F, Eriksson J, Sennfält K, Lindgren P. Metabolic effects and cost-effectiveness of aripiprazole versus olanzapine in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011; 124: 214– 225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen Y-W, Dilsaver SC. Lifetime rates of suicide attempts among subjects with bipolar and unipolar disorders relative to subjects with other axis I disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1996; 39: 896– 899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tondo L, Isacsson G, Baldessarini RJ. Suicidal behaviour in bipolar disorder: risk and prevention. CNS Drugs. 2003; 17: 491– 511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stensland MD, Zhu B, Ascher-Svanum H, Ball DE. Costs associated with attempted suicide among individuals with bipolar disorder. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2010; 13: 87– 92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Viguera AC, Whitfield T, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Risk of recurrence in women with bipolar disorder during pregnancy: prospective study of mood stabilizer discontinuation. Am J Psychiatry. 2007; 164: 1817– 1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McKenna K, Koren G, Tetelbaum M, et al. Pregnancy outcome of women using atypical antipsychotic drugs: a prospective comparative study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005; 66: 444– 449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]