Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are widely used in clinical settings to treat tissue injuries and autoimmune disorders due to their multipotentiality and immunomodulation. Long-term observations reveal several complications after MSCs infusion, especially herpesviral infection. However, the mechanism of host defense against herpesviruses in MSCs remains largely unknown. Here we showed that murine gammaherpesvirus-68 (MHV-68), which is genetically and biologically related to human gammaherpesviruses, efficiently infected MSCs both in vitro and in vivo. Cytosolic DNA sensor cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) was identified as the sensor of MHV-68 in MSCs for the first time. Moreover, the cytosolic DNA sensing pathway mediated a potent anti-herpesviral effect through the adaptor STING and downstream kinase TBK1. Furthermore, blockade of IFN signaling suggested that cytosolic DNA sensing triggered both IFN-dependent and -independent anti-herpesviral responses. Our findings demonstrate that cGAS-STING mediates innate immunity to gammaherpesvirus infection in MSCs, which may provide a clue to develop therapeutic strategy.

Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a heterogeneous population of stromal cells that exist in almost all adult tissues1. They can be readily isolated from several tissues, such as bone marrow, adipose tissue and umbilical cord. Due to their tissue regenerative capacity and immunoregulatory property, MSCs recently have attracted considerable attention for potential clinical applications. They have been successfully used to enhance the efficiency of hematopoietic stem cell engraftment2, and to treat acute graft-versus-host disease (GvHD)3 as well as autoimmune disorders4.

Although MSCs are widely used clinically, long-term observations reveal several complications after MSCs infusion, especially infectious complications5. Herpesviral infection is a major cause of morbidity and mortality after stem cell transplantation6. Recently, increasing experimental evidence shows that MSCs are highly susceptible to herpesviruses. Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) can infect MSCs and induce obvious cytopathic effect (CPE)7. A recent study shows that placenta-derived MSCs are fully permissive to infection with HSV-1, HSV-2, Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and CMV8. In addition, human fetal MSCs are susceptible to Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) in culture, and the infection persists within half of the cells for up to six weeks9. Thus, it is possible that MSCs carrying herpesviruses lead to horizontal transmission of pathogens to recipients after cells infusion. Moreover, KSHV efficiently infects and transforms MSCs to induce tumors10. These observations raise a safety concern with ex vitro expansion and subsequent clinical transplantation of MSCs. Besides, CMV-infected MSCs show impaired immunosuppressive and antimicrobial functions, which may undermine the clinical efficacy of MSC-based therapies11. Therefore, it is important to investigate the mechanism by which MSCs recognize and defend against invading herpesviruses to develop a novel strategy to eliminate viruses in MSCs.

As a large family of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses, herpesviruses can cause lytic infection in permissive cells, and establish life-long latency in specific cell types. These viruses cause diseases during both primary infection (e.g. infectious mononucleosis, chickenpox) and reactivation from a latent infection (e.g. shingles). Moreover, gammaherpesviral latency proteins could drive virus-associated carcinogenesis in genetically predisposed individuals, and result in several cancers, such as Kaposi's sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma12, Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma13. The innate immune system is an important arm in control of herpesviruses infection. Distinct classes of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) detect invading pathogens on the cell surface or in cytosolic compartments14. Genomic DNA is the most potent immune-stimulating component of herpesviruses. Substantial evidence suggests that human herpesviruses can be recognized by Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9 located in endosomes in plasmacytoid dendritic cells or primary monocytes15,16,17, while other studies demonstrate the existence of TLR9-independent recognition of herpesviruses18. Most recently, several cytosolic receptors have been proposed for recognition of foreign DNA in the cytosol19,20, which may also contribute to innate immune response to herpesviruses21,22.

To date, several cytosolic DNA sensors have been identified, including DNA-dependent activator of IFN-regulatory factors (DAI)23, absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2)24, IFN-γ-inducible protein 16 (IFI16, also called p204 in the mouse)25 and DEAD box polypeptide 41 (DDX41)26. Recent studies report that cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) also functions as a cytosolic DNA sensor to induce IFN by producing the second messenger cyclic GMP-AMP27,28. Although cytosolic DNA can be detected by distinct sensors, STING is a central adaptor protein shared by these cytosolic DNA sensing pathways29. In the presence of cytosolic dsDNA or cyclic dinucleotides, STING recruits and phosphorylates TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1). The activated TBK1 phosphorylates IFN-regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), which is a key transcription factor required for the expression of type I IFNs30. Subsequently, type I IFNs induce various interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) via the Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway to mount an efficient antiviral response31. Therefore, the cytosolic DNA sensing pathway is critical for host defense against cytosolic bacteria and DNA viruses in innate immune cells32. Several studies reveal that MSCs express some PRRs, including TLRs (TLR3 and TLR4)33, nucleotide binding and oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs)34 and retinoic acid inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs)35, which regulate differentiation, immunomodulation and survival of MSCs. Nonetheless, little is known regarding the expression and function of cytosolic DNA sensors in MSCs.

The present study explores a novel mechanism by which murine MSCs recognize and defend against invading herpesviruses. Our results indicate that the cytosolic cGAS-STING pathway but not endosomal TLR9 is responsible for sensing murine gammaherpesvirus-68 (MHV-68). Activation of the cytosolic DNA sensing pathway triggers a robust antiviral response via STING-TBK1 signaling axis, and restricts the replication of MHV-68 in both IFN-dependent and -independent manners. Our findings provide insight into both the mechanism of innate immunity against herpesviruses in MSCs and the antiviral function of the cytosolic DNA sensing pathway.

Results

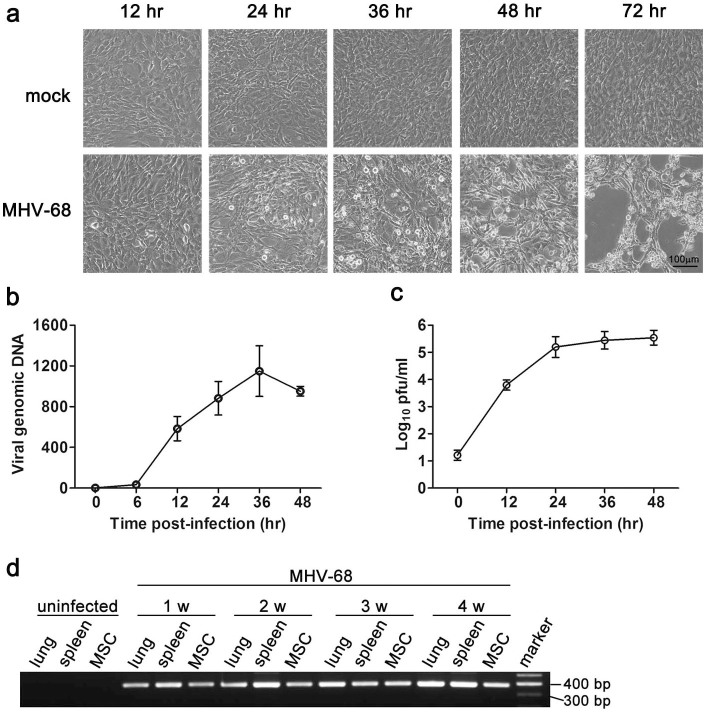

MHV-68 infects MSCs both in vitro and in vivo

To explore the mechanism of innate recognition and host defense against herpesviruses in MSCs, we established a cellular infection model of murine gammaherpesvirus MHV-68, which is genetically and biologically similar to human gammaherpesviruses. We challenged MSCs with MHV-68 at an MOI 0.1, and typical CPE was detected at 24 hr post-infection (Fig. 1a). Most of MSCs lysed or detached from the culture dish at 72 hr after exposure to MHV-68 (Fig. 1a). We further detected viral DNA in MSCs by real-time PCR, and found that MHV-68 DNA copies increased in a time-dependent manner, peaking at 36 hr post-infection (Fig. 1b). Extracellular virion yield of infected MSCs was examined by plaque assay. As shown in Fig. 1c, virus titers in the supernatant of MSCs increased markedly post-infection, indicating that cultured MSCs were permissive to MHV-68 infection. To further investigate whether MHV-68 infects MSCs in vivo, MSCs were isolated from mice intranasally infected with MHV-68, and the existence of viral DNA was detected by using nested PCR. At all the indicated times (from 1 to 4 weeks) post-infection, viral DNA was detected in primary isolated MSCs, as well as in lung and spleen, which are well-characterized sites of acute infection and latency of MHV-68 (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1. MHV-68 infects MSCs both in vitro and in vivo.

MSCs were infected with MHV-68 (MOI 0.1) for the indicated time, and the cytopathic effect was examined microscopically (a). The replication of viral DNA was detected by real-time PCR (b). The virus titers in the supernatant were determined by plaque assay (c). Data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (d) C57BL/6 mice were intranasally inoculated with MHV-68. Viral DNA in lung, spleen or bone-marrow-derived MSCs was detected with nested PCR of ORF50 gene at the indicated time post-infection. Data are representative of three experiments with similar results.

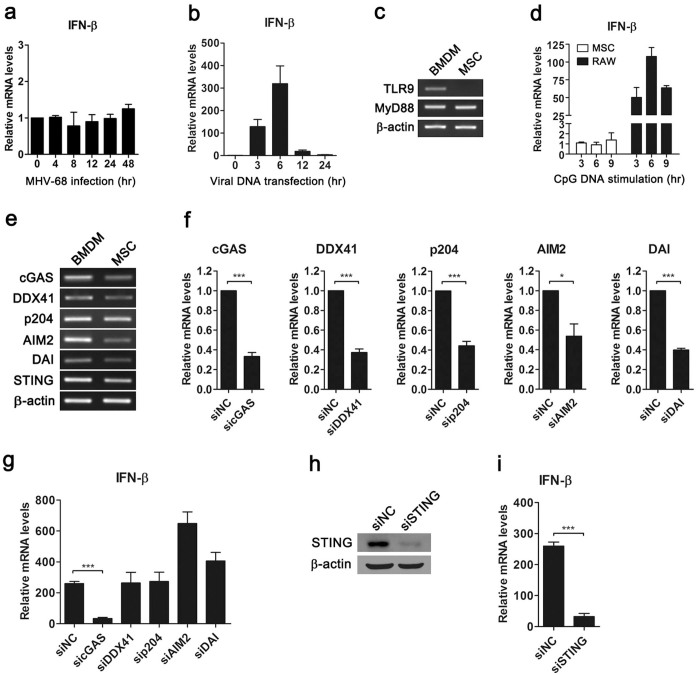

The cGAS-STING cytosolic DNA sensing pathway mediates recognition of MHV-68 in MSCs

To investigate the innate immune response to MHV-68 in MSCs, cells were infected with MHV-68, and induction of the downstream gene IFN-β was examined. We found that IFN-β was not induced in MSCs after infection (Fig. 2a), suggesting that MHV-68 may inhibit the IFN response. To explore how MSCs detected foreign nucleic acid of invading MHV-68, we stimulated cells with viral DNA by transfection. Real-time PCR data showed that viral DNA induced the expression of IFN-β (Fig. 2b), indicating activation of the innate immune response. Next, we examined which receptors detected viral DNA in MSCs. Since MHV-68 is a dsDNA virus, we first tested whether TLR9 was involved in detection of MHV-68. The expression of TLR9 was examined by RT-PCR in MSCs. While BMDM expressed TLR9, mRNA of TLR9 was not detectable in MSCs (Fig. 2c). We further stimulated MSCs with TLR9 ligand CpG DNA, and examined the expression of the downstream gene IFN-β. While CpG DNA induced the expression of IFN-β in murine macrophage-like RAW264.7 cells, MSCs failed to respond to CpG DNA (Fig. 2d). These results indicated that mouse MSCs did not express functional TLR9, thus ruling out the possibility of TLR9-mediated recognition of MHV-68 in MSCs. In addition to endosomal TLR9, foreign dsDNA can also be detected by cytosolic DNA sensors. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that cytosolic DNA sensors may recognize MHV-68 in MSCs. The expressions of well-characterized cytosolic DNA sensors including cGAS, DDX41, p204, AIM2, DAI and the adaptor STING were detected with RT-PCR. BMDM were used as positive control, which expressed the receptors above (Fig. 2e). Similarly, all of the receptors were expressed in MSCs, though at different levels (Fig. 2e). Furthermore, we knocked down each DNA sensor with a small interfering RNA (siRNA) to determine which sensor was responsible for detection of MHV-68 (Fig. 2f). Notably, MHV-68 DNA-induced IFN-β expression in MSCs was impaired by cGAS-specific siRNA, whereas siRNAs targeting other DNA sensors did not reduce IFN-β expression (Fig. 2g). During cytosolic DNA sensing, STING is a central adaptor protein. Thus, we knocked down STING to examine whether STING mediated recognition of MHV-68 in MSC. The knockdown efficacy was confirmed by Western blot (Fig. 2h). Real-time data showed that knockdown of STING attenuated the expression of IFN-β in MSCs stimulated with viral DNA (Fig. 2i). These results suggest that the cGAS-STING cytosolic DNA sensing pathway recognized MHV-68 in MSCs.

Figure 2. The cGAS-STING cytosolic DNA sensing pathway mediates recognition of MHV-68 in MSCs.

MSCs were infected with MHV-68 (MOI 0.1) (a) or transfected with MHV-68 DNA (0.5 μg/ml) (b) for the indicated time, and then analyzed for IFN-β expression by real-time PCR. The expressions of TLR9 and MyD88 in MSCs or BMDM were detected with RT-PCR (c). MSCs and RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with CpG DNA (2 μM) for the indicated time, and then analyzed for IFN-β mRNA expression (d). The expressions of cytosolic DNA sensors and adaptor STING in MSCs or BMDM were detected with RT-PCR (e). MSCs were transfected with indicated siRNA for 48 hr, and then stimulated with MHV-68 DNA (0.5 μg/ml) for 6 hr (f)–(i). The knockdown efficacy was confirmed by real-time PCR (f) or Western blot (h), and the expressions of IFN-β were detected by real-time PCR (g), (i). RT-PCR and Western blot data are representative of three experiments with similar results. Real-time PCR data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001.

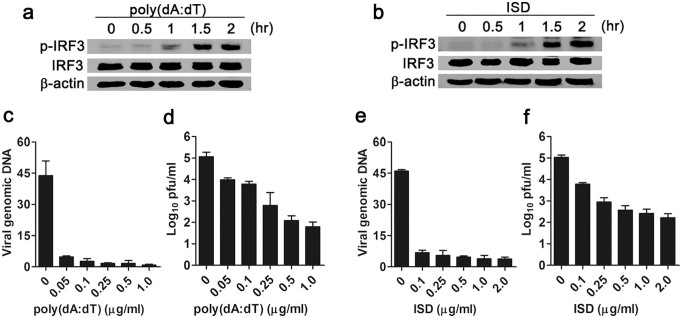

Activation of the cytosolic DNA sensing pathway restricts the replication of MHV-68 in MSCs

To further explore whether the cytosolic DNA sensing pathway mediated anti-herpesviral response in MSCs, we stimulated MSCs with synthetic dsDNA poly(dA:dT) or interferon stimulatory DNA (ISD, a synthetic 45 bp dsDNA) to activate the cytosolic DNA sensing pathway. Western blot data showed that both poly(dA:dT) (Fig. 3a) and ISD (Fig. 3b) induced phosphorylation of IRF3 in a time-dependent manner in MSCs, suggesting activation of the cytosolic DNA sensing pathway. Next, we examined the replication of MHV-68 in MSCs after dsDNA stimulation. Pretreatment with poly(dA:dT) dramatically inhibited the replication of viral DNA (Fig. 3c). Plaque assay also showed a marked decrease in infectious viral particle yield of poly(dA:dT)-pretreated MSCs (Fig. 3d). Similarly, ISD stimulation led to inhibition of MHV-68 DNA replication (Fig. 3e) and viral particle yield (Fig. 3f). These observations suggest an anti-herpesviral response upon activation of cytosolic DNA sensing pathway.

Figure 3. Activation of the cytosolic DNA sensing pathway restricts the replication of MHV-68 in MSCs.

MSCs were transfected with poly (dA:dT) (a) or ISD (b) (0.5 μg/ml), and phosphorylation of IRF3 was detected by Western blot. Data are representative of three experiments with similar results. MSCs were transfected with poly (dA:dT) (c), (d) or ISD (e), (f) at the indicated concentration for 6 hr, then infected with MHV-68 (MOI 0.1). The replication of viral DNA was detected by real-time PCR at 6 hr post-infection (c and e). The virus titers in the supernatant were determined by plaque assay at 24 hr post-infection (d), (f). Data are shown as mean ± SD. of three independent experiments.

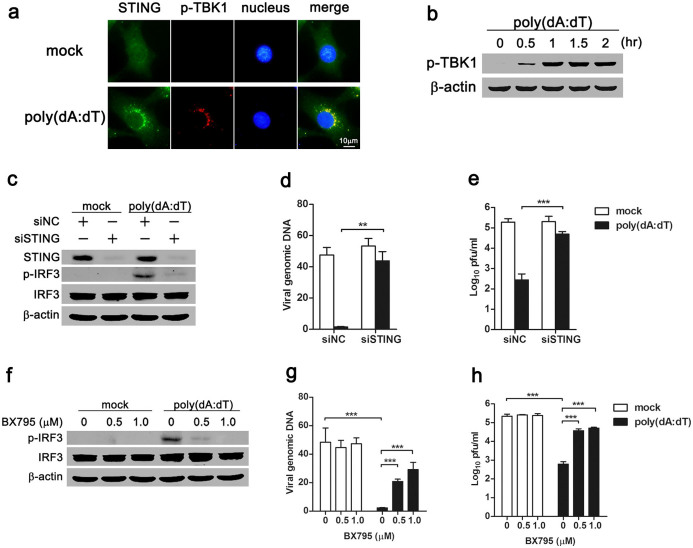

STING-TBK1 signaling axis is required for the anti-herpesviral response of cytosolic DNA sensing

During cytosolic DNA sensing, the adaptor STING recruits and phosphorylates TBK1 kinase to activate downstream signaling. To examine STING-TBK1 signaling, MSCs were stimulated with poly(dA:dT), and the subcellular distribution of STING and phosphorylated TBK1 was visualized with immunofluorescence microscopy. In mock-treated MSCs, STING distributed diffusely in the cytosol, and phosphorylation of TBK1 was not observed (Fig. 4a). However, in response to dsDNA transfection, STING aggregated perinuclearly, and phosphorylated TBK1 was found to co-localize with STING (Fig. 4a). Moreover, Western blot showed that phosphorylation of TBK1 in MSCs after poly(dA:dT) transfection was time-dependent (Fig. 4b). These observations indicated activation of the STING-TBK1 signaling in dsDNA-stimulated MSCs. To elucidate whether the adaptor STING mediated the cytosolic DNA sensing-induced antiviral response, we silenced endogenous STING with siRNA in MSCs, and stimulated the cells with poly(dA:dT). Western blot showed that phosphorylation of downstream transcription factor IRF3 was dramatically attenuated in poly(dA:dT)-stimulated MSCs in which STING was knocked down (Fig. 4c), suggesting a critical role of STING in cytosolic DNA sensing. Furthermore, viral DNA replication and virion yield were examined in STING-silenced MSCs. Both real-time PCR (Fig. 4d) and plaque assay (Fig. 4e) data showed that dsDNA stimulation decreased viral replication in siNC-treated MSCs, while the antiviral effect was abolished in STING-silenced MSCs (Fig. 4d, 4e). These results indicated that the adaptor STING mediated the antiviral response of cytosolic DNA sensing pathway.

Figure 4. STING adaptor and TBK1 kinase are required for the antiviral response of cytosolic DNA sensing pathway.

MSCs were transfected with poly(dA:dT) (0.5 μg/ml) for 1 hr, and the subcellular distribution of STING and phosphorylated TBK1 were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy (a). Phosphorylation of TBK1 kinase was detected by Western blot (b). MSCs were transfected with siSTING for 48 hr (c)-(e) or pretreated with BX795 for 1 hr (f)-(h), and then transfected with poly(dA:dT) (0.5 μg/ml), followed by MHV-68 infection (MOI 0.1). Protein levels of STING and phosphorylated IRF3 were analyzed by Western blot (c), (f). Data are representative of three experiments with similar results. The replication of viral DNA was detected by real-time PCR at 6 hr post-infection (d), (g). The virus titers in the supernatant were determined by plaque assay at 24 hr post-infection (e), (h). Real-time PCR data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

To further test the involvement of TBK1 in the cytosolic DNA sensing-mediated antiviral response, small molecule kinase inhibitor BX795 was used to inhibit TBK1 activity. When stimulated with poly(dA:dT), TBK1-inhibited MSCs showed less phosphorylation of IRF3 (Fig. 4f). When TBK1 kinase was inhibited, poly(dA:dT)-treated MSCs showed increased viral DNA replication (Fig. 4g) and virion production (Fig. 4h). Thus, TBK1 kinase was required for the cytosolic DNA sensing-mediated antiviral effect.

Cytosolic DNA sensing mediates both IFN-dependent and -independent antiviral effects

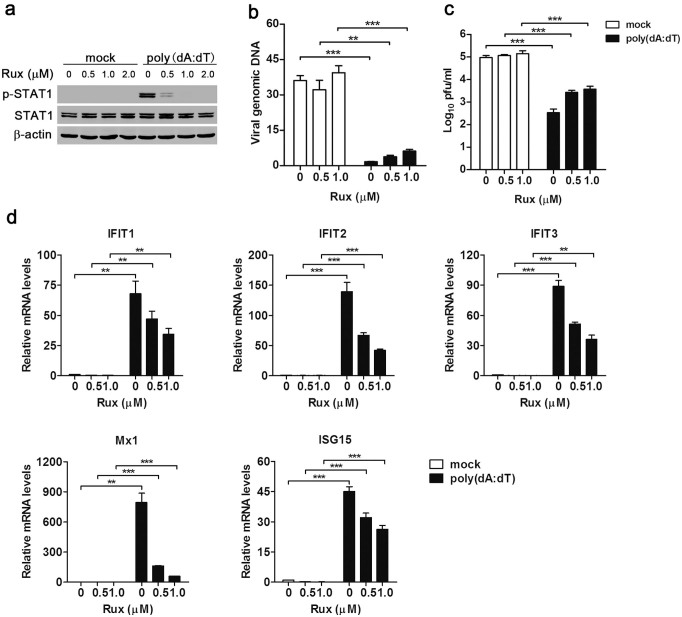

Activation of STING-TBK1 signaling axis after cytosolic dsDNA stimulation leads to the production of type I IFNs, which initiate an innate antiviral response by inducing hundreds of ISGs through the JAK-STAT pathway. To determine whether cytosolic DNA sensing-mediated antiviral effect depended on an autocrine effect of type I IFNs, JAK inhibitor Ruxolitinib was used to block IFN-JAK-STAT signaling in dsDNA-stimulated MSCs. Western blot showed that at the concentration of 1.0 μM, Ruxolitinib almost completely blocked dsDNA-induced phosphorylation of STAT1 downstream of IFN-JAK-STAT pathway (Fig. 5a). Furthermore, we found that blocking of the JAK-STAT pathway partially reduced the DNA sensing-mediated antiviral activity, as indicated by both viral DNA (Fig. 5b) and plaque assay data (Fig. 5c). These results suggest that the DNA-sensing pathway could mediate antiviral effects in the absence of canonical IFN-JAK-STAT signaling. Moreover, we examined whether the DNA-sensing pathway can mediate antiviral ISGs expression independently of IFN signaling. Real-time PCR data showed that when IFN-JAK-STAT pathway was blocked by Ruxolitinib, transfection with poly(dA:dT) still induced expressions of ISGs, including IFIT1-3, ISG15 and Mx1, though the expression levels were lower than that in MSCs without Ruxolitinib treatment (Fig. 5d). Together, these data imply that cytosolic DNA sensing mediated both IFN-dependent and -independent antiviral effects.

Figure 5. Cytosolic DNA sensing pathway mediates both IFN-dependent and -independent antiviral responses.

MSCs were pretreated with JAK inhibitor Ruxolitinib (Rux) for 1 hr, then transfected with poly(dA:dT) (0.5 μg/ml), followed by MHV-68 infection (MOI 0.1). The phosphorylation of STAT1 was examined by Western blot at 2 hr post-tranfection (a). The replication of viral DNA was detected by real-time PCR at 6 hr post-infection (b). The virus titers in supernatant were determined by plaque assay at 24 hr post-infection (c). The mRNA expressions of selected ISGs were analyzed by real-time PCR at 6 hr post-tranfection (d). Data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Discussion

Recently, MSCs infusion is a plausible strategy in clinical treatment of tissue injury and immune-related disorders36,37, due to the multipotentiality and immunomodulatory properties of MSCs. Nevertheless, increasing clinical reports reveal that allogeneic stem cell transplantation is often complicated by herpesviral infection38,39,40, thus raising the safety concerns41. However, the mechanism of host defense against herpesviruses in MSCs remains elusive. In this study, for the first time, we identify functional cytosolic DNA sensors in MSCs, and demonstrate that the cGAS-STING cytosolic DNA sensing pathway is responsible for detecting murine gammaherpesvirus MHV-68, and mediates both IFN-dependent and independent anti-herpesviral responses in MSCs.

Previous studies suggest that human MSCs are highly susceptible to several herpesviruses, including HSV, CMV7 and KSHV9. In the present study, we find that cultured MSCs are lytically infected by murine gammaherpesvirus MHV-68. Moreover, viral DNA is detected in MSCs from MHV-68-infected mice, suggesting that MSCs may be latently infected with gammaherpesvirus in vivo and serve as viral reservoirs. This observation supports a general belief that horizontal transmission of herpesviruses from grafts to recipients results in serious complication in patients receiving allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Herpesviruses can be sensed via both TLR-dependent and -independent pathways18,42. In plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), endosomal TLR9 mediates recognition of HSV and KSHV43,44,45. Here, we find that murine MSCs do not express functional TLR9, which is consistent with a previous report33. Other studies reveal that cytosolic DNA sensors are also responsible for recognition of herpesviruses, such as IFI16 detecting KSHV DNA in endothelial cells22, DAI sensing human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) in fibroblasts, as well as DAI23, IFI1625, DDX4126 and AIM232 all of which recognize HSV-1 in macrophages. These studies reveal redundant cytosolic DNA sensors, and cell type-specific DNA sensing pathways. However, a recent study demonstrates a non-redundant role of newly-discovered cytosolic sensor cGAS for DNA sensing in macrophages, dendritic cells and fibroblasts46. These cytosolic DNA sensors have not been reported in MSCs before. We show here that all of the sensors above are expressed in MSCs, and cGAS is indispensible for recognition of MHV-68 in MSCs. Previous studies show that AIM2 recognizes cytosolic DNA and assembles the inflammasome to mediate an inflammatory response24. Nevertheless, upon binding to dsDNA, AIM2 does not induce an IFN response, and rather serves as a negative regulator24,32. Here, we also observe enhanced IFN-β expression in AIM2-knocked down MSCs after viral DNA stimulation. Whether AIM2 triggers the inflammasome in MSCs after MHV-68 infection may be possible, but needs further investigation.

Upon detection of viral dsDNA, cytosolic DNA sensing pathway plays a critical role in host antiviral response. For example, AIM2-knockout mice have a higher viral load in spleens after exposure to mouse cytomegalovirus than wild-type mice32. A recent study reveals that cGAS is essential for immune defense against HSV-1 infection in vivo46. IFI16 acts as a restriction factor against HCMV replication in human embryonic lung fibroblasts47. We find that activation of cytosolic DNA sensing pathway restricts the replication of MHV-68. In addition, previous studies show that the deficiency of adaptor STING renders mice more susceptible to lethal infection with HSV-129, and that downstream TBK1 kinase is required for host defense against DNA viruses infection, including MHV-6848. Consistently, we demonstrate that cytosolic DNA sensing mediates an anti-herpesviral effect, and that this requires the STING-TBK1 signaling axis. Previous studies demonstrate that MHV-68 develops several strategies to evade host antiviral defense at multiple stages, such as TBK149, IRF339 and IFNAR50. Here, we find that MHV-68 infection does not induce an IFN response. It is possible that MHV-68 antagonizes the cytosolic DNA sensing-mediated IFN response in MSCs after infection. It may explain why knockdown of STING or inhibition of TBK1 in MSCs without exogenous dsDNA stimulation does not affect MHV-68 replication. Therefore, activation of the cytosolic DNA sensing pathway with synthetic dsDNA may provide a novel strategy to elicit host antiviral response to inhibit MHV-68 replication.

Cytosolic DNA sensing activates STING-TBK1-IRF3 signaling axis that triggers the expression of type I IFNs20. It is generally thought that PRRs induce the expression of type I IFNs that act in an autocrine manner to amplify ISGs expression and direct a multifaceted antiviral response. However, ISGs can also be induced directly without need for canonical IFN signaling. For example, RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) adaptor protein IPS-I located on the peroxisome induces rapid IFN-independent expression of ISGs upon RNA virus infection, and provides short-term protection51. Knockout of cytosolic exonuclease Trex1 induces high expression of antiviral ISGs genes in type I IFN receptor deficient cells52. The IFN-independent activation of antiviral genes in Trex1−/− cells requires the adaptor STING, the kinase TBK1 and the transcription factors IRF352. Most recently, Schoggins et al. report that ectopic expression of cGAS in STAT1−/− fibroblasts which are deficient in IFN signaling, induces many ISGs via the STING-IRF3 pathway53. This study indicates that cytosolic DNA sensing can also mediate an antiviral program independent of canonical IFN signaling. In this study, we find that cytosolic DNA sensing mediates an antiviral response in MSCs via STING-TBK1 signaling axis, and blockade of IFN signaling with JAK inhibitor can only partially reduce cytosolic DNA sensing-mediated antiviral activity. The result implies an IFN/JAK/STAT-independent antiviral response. However, further investigation using MSCs isolated from STAT1−/− mice is needed to provide convincing evidence to demonstrate the IFN-independent mechanism.

In summary, we demonstrate that MSCs recognize gammaherpesvirus MHV-68 via cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS. Activation of the cytosolic DNA sensing pathway by dsDNA limits the replication of MHV-68 via STING-TBK1 signaling axis. Furthermore, our data suggest that the cytosolic DNA sensing pathway mediates antiviral defense in both IFN-dependent and -independent manners. These findings give a better understanding of not only host defense against gammaherpesvirus infection in MSCs but also the antiviral function of the cGAS-STING pathway. Therefore, our study may provide a novel strategy for clinical treatment of gammaherpesvirus infections.

Methods

Ethics statement

The methods used were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. All experimental protocols were approved by Sun Yat-sen University. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University and performed in accordance with the guidelines of Animal Care and Use of Sun Yat-sen University.

Reagents

Poly(dA:dT) was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG DNA, TLR9 ligand) and BX795 (TBK1 inhibitor) were from Invivogen (San Diego, CA). Ruxolitinib (JAK inhibitor) was obtained from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX). Anti-STING (3337S), anti-phosphorylated IRF3 (4947S), anti-phosphorylated TBK1 (5483S), anti-phosphorylated STAT1 (Tyr701) (9171S) and (for Western blot) antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Anti-IRF3 (sc-9082), anti-STAT1 (sc-346) and anti-STING antibody (sc-241049) (for immunofluorescence microscopy) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-β-actin antibody (A1978) was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Cell culture

MSCs were obtained from bone marrow of tibia and femur of 6- to 8-week-old female C57BL/6 mice as described previously35,54. Cells were maintained in DMEM low glucose medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (all from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The isolated MSCs were immunophenotyped by flow cytometry as reported previously54. MSCs from passage 5 to 20 were used in all experiments. Macrophage-like RAW264.7 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS as reported previously55. Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were isolated and cultured as described previously56. All experiments involving animals were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University.

Nucleic acids transfection

To activate cytosolic DNA sensing pathway or stimulate MSCs with viral DNA, poly(dA:dT), interferon stimulatory DNA (ISD, a synthetic 45 bp dsDNA) or MHV-68 DNA was transfected into the cytosol of MSCs by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Virus and plaque assay

MHV-68 was kindly provided by Prof. Yan Yuan (University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine, Philadelphia), and propagated in Vero cells. Viral titer was determined by plaque assay and viral stocks were stored at −80°C. For plaque assay, ten-fold serial dilutions of each cell-free supernatant were incubated on a monolayer of Vero cells for 1 hr with occasional rocking. The infected cells were then overlaid with culture medium containing 0.5% agarose. After one week incubation, plaques were visualized with 0.03% neutral red staining and counted at the optimum dilution to calculate virus titer.

Mice infection and organ harvesting

C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized and intranasally inoculated with 5 000 PFU of MHV-68. The infected mice were sacrificed at indicated time post-infection, and lung and spleen tissues were harvested and homogenized for DNA isolation. MSCs were isolated as described above. All mice procedures here were performed according to the Animal Ethics Committee guides of Sun Yat-sen University. MHV68 DNA was determined by using nested PCR of viral ORF50 gene sequence as described previously57.

Western blot

Western blot was performed as described previously56. Briefly, the whole-cell extract was resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin and then incubated with diluted primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Western blot detection was performed with IRDye 800 CW conjugated anti-rabbit IgG or IRDye 680 CW conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies according to the manufacturer's protocols (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). The blots were visualized using an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

siRNA knockdown

siRNAs were chemically synthesized by Invitrogen, and scrambled siRNA (siNC) was used as negative control. The target sequences of siRNAs used were as following: STING, 5′-GAGCTTGACTCCAGCGGAA-3′27,28; cGAS, 5′-GGATTGAGCTACAAGAATA-3′27; DDX41, 5′-TGACATGCCTGAAGAGATA-3′27; p204, 5′-AGAAAACAGTGAACCGAAA-3′27; AIM2, 5′-ACATAGACACTGAGGGTAT-3′58; DAI, 5′-GGTCAAAGGGTGAAGTCAT-3′23; For knockdown experiments, cells were transfected with siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol.

Quantitative nucleic acid analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells with TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and reverse transcribed into cDNA by RevertAid™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). For RT-PCR, the expression of various transcripts was assessed by PCR amplification using a standard protocol. Amplified products were fractionated by 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of transcripts was performed on Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time detection system using SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequences of primer pairs used were listed in Table 1. Other primers used in the present study were described previously35. For cytosolic MHV-68 DNA quantification, DNA was isolated from MHV-68-infected MSCs using TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) per manufacturer's protocol. Viral DNA (ORF56) and cellular β-actin were quantified by real-time PCR59. Viral genomic DNA in infected cells was calculated as compared to internal control β-actin.

Table 1. Sequence of primers used in PCR amplification.

| Gene | Primer Sequence (5′ - 3′) |

|---|---|

| cGAS | Fwd:ACCGGACAAGCTAAAGAAGGTGCT |

| Rev: GCAGCAGGCGTTCCACAACTTTAT | |

| DDX41 | Fwd: TGAAGCTGACCGCATGATTGAC |

| Rev: TCCAGCACGACCCACATTGA | |

| p204 | Fwd: ACCAAGAGCAATACACCACG |

| Rev: TCTCGCCTCTTTCAGATGCT | |

| AIM2 | Fwd: GTTATTAAGACTGCCCAACCTG |

| Rev: CATCCAATAGATGACTGTGAGC | |

| DAI | Fwd: AATCAAGTCCTTTACCGCCTG |

| Rev: TTTCATCAAGGCTAGGCTGG | |

| STING | Fwd: ATTCCAACAGCGTCTACGAG |

| Rev: GCAGAAGAGTTTAGCCTGCT | |

| Mx1 | Fwd: ACAGGACACCAGTAAGTGCAGC |

| Rev: AGCGACCAGGAAAGCCACATAG | |

| ISG15 | Fwd: ACTAACTCCATGACGGTGTCAG |

| Rev: GTTCCTCACCAGGATGCTCAG | |

| IFIT1 | Fwd: CGCGTAGACAAAGCTCTTCATC |

| Rev: ATGGCCTGTTGTGCCAATTC | |

| IFIT2 | Fwd: ATGAGTTTCAGAACAGTGAGTTTAA |

| Rev: AACTGGCCCATGTGATAGTAGACCC | |

| IFIT3 | Fwd: TGGCCTACATAAAGCACCTAGATGG |

| Rev: CGCAAACTTTTGGCAAACTTGTCT |

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were grown on glass coverslips and treated as indicated, and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 and blocked with 5% BSA. Samples were incubated with primary antibody at 4°C overnight, and then with secondary antibody for 1 hr at room temperature. Nuclei were labeled with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. Coverslips were mounted with ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen) and visualized using Olympus BX53 fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed for at least three times independently. GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for statistical analysis. Differences between two groups were compared by using an unpaired Student's t-test. Differences between three groups or more were compared by using a one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's post-test. Differences were considered statistically significant with a p value less than 0.05.

Author Contributions

X.H. conceived and supervised the project; X.H., M.W. and K.Y. designed the experiments; K.Y. performed most of the experiments; J.W. performed Western blot analysis; Y.W. performed some plaque-forming assays; M.L. provided key reagents; X.H., K.Y. and M.W. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants National Natural Science Foundation of China (31470877, 81261160323, 81172811, 30972763, U0832006, 31200662), Guangdong Innovative Research Team Program (No. 2009010058), Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (10251008901000013, S2012040006680), Guangdong Province Universities and Colleges Pearl River Scholar Funded Scheme (No. 2009), National Science and Technology Key Projects for Major Infectious Diseases (2013ZX10003001), The 111 Project (No. B13037). The authors wish to thank Dr. Linda D. Hazlett from Wayne State University School of Medicine for her useful comments and in-depth language editing.

References

- Uccelli A., Moretta L. & Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 726–736 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou S. H. et al. Mesenchymal stem cell insights: prospects in hematological transplantation. Cell Transplant. 22, 711–721 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc K. et al. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet 363, 1439–1441 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo M. E. & Fibbe W. E. Safety and efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in autoimmune disorders. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1266, 107–117 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bahr L. et al. Long-term complications, immunologic effects, and role of passage for outcome in mesenchymal stromal cell therapy. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 18, 557–564 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forslow U. et al. Treatment with mesenchymal stromal cells is a risk factor for pneumonia-related death after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Eur. J. Haematol. 89, 220–227 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundin M. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells are susceptible to human herpesviruses, but viral DNA cannot be detected in the healthy seropositive individual. Bone Marrow Transplant. 37, 1051–1059 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avanzi S. et al. Susceptibility of human placenta derived mesenchymal stromal/stem cells to human herpesviruses infection. PLoS One 8, e71412 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons C. H., Szomju B. & Kedes D. H. Susceptibility of human fetal mesenchymal stem cells to Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Blood 104, 2736–2738 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. et al. Direct and efficient cellular transformation of primary rat mesenchymal precursor cells by KSHV. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 1076–1081 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel R. et al. Cytomegalovirus infection impairs immunosuppressive and antimicrobial effector functions of human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2014, 898630 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesri E. A., Cesarman E. & Boshoff C. Kaposi's sarcoma and its associated herpesvirus. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 707–719 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M. P. & Kurzrock R. Epstein-Barr virus and cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 803–821 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S., Uematsu S. & Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124, 783–801 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund J., Sato A., Akira S., Medzhitov R. & Iwasaki A. Toll-like receptor 9-mediated recognition of Herpes simplex virus-2 by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 198, 513–520 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varani S. et al. Human cytomegalovirus differentially controls B cell and T cell responses through effects on plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 179, 7767–7776 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiola S., Gosselin D., Takada K. & Gosselin J. TLR9 contributes to the recognition of EBV by primary monocytes and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 185, 3620–3631 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochrein H. et al. Herpes simplex virus type-1 induces IFN-alpha production via Toll-like receptor 9-dependent and -independent pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 11416–11421 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V. & Latz E. Intracellular DNA recognition. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 123–130 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paludan S. R. & Bowie A. G. Immune sensing of DNA. Immunity 38, 870–880 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFilippis V. R., Alvarado D., Sali T., Rothenburg S. & Fruh K. Human cytomegalovirus induces the interferon response via the DNA sensor ZBP1. J. Virol. 84, 585–598 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerur N. et al. IFI16 acts as a nuclear pathogen sensor to induce the inflammasome in response to Kaposi Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection. Cell Host Microbe 9, 363–375 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka A. et al. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature 448, 501–505 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V. et al. AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase-1-activating inflammasome with ASC. Nature 458, 514–518 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterholzner L. et al. IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nat. Immunol. 11, 997–1004 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. et al. The helicase DDX41 senses intracellular DNA mediated by the adaptor STING in dendritic cells. Nat. Immunol. 12, 959–965 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Wu J., Du F., Chen X. & Chen Z. J. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science 339, 786–791 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science 339, 826–830 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H., Ma Z. & Barber G. N. STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity. Nature 461, 788–792 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y. & Chen Z. J. STING specifies IRF3 phosphorylation by TBK1 in the cytosolic DNA signaling pathway. Sci. Signal. 5, ra20 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W. M., Chevillotte M. D. & Rice C. M. Interferon-stimulated genes: a complex web of host defenses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 32, 513–545 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinam V. A. et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is essential for host defense against cytosolic bacteria and DNA viruses. Nat. Immunol. 11, 395–402 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pevsner-Fischer M. et al. Toll-like receptors and their ligands control mesenchymal stem cell functions. Blood 109, 1422–1432 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. S. et al. Implication of NOD1 and NOD2 for the differentiation of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells derived from human umbilical cord blood. PLoS One 5, e15369 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K. et al. Functional RIG-I-like receptors control the survival of mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 4, e967 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marigo I. & Dazzi F. The immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cells. Semin. Immunopathol. 33, 593–602 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo M. E., Pagliara D. & Locatelli F. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy: a revolution in Regenerative Medicine? Bone Marrow Transplant. 47, 164–171 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allain J. P. Emerging viral infections relevant to transfusion medicine. Blood Rev. 14, 173–181 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppi M. et al. Bone marrow failure associated with human herpesvirus 8 infection after transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 343, 1378–1385 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulery R. et al. Early human herpesvirus type 6 reactivation after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a large-scale clinical study. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 18, 1080–1089 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behzad-Behbahani A. et al. Risk of viral transmission via bone marrow progenitor cells versus umbilical cord blood hematopoietic stem cells in bone marrow transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 37, 3211–3212 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmgaard L., Melchjorsen J., Bowie A. G., Mogensen S. C. & Paludan S. R. Viral activation of macrophages through TLR-dependent and -independent pathways. J. Immunol. 173, 6890–6898 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug A. et al. Herpes simplex virus type 1 activates murine natural interferon-producing cells through toll-like receptor 9. Blood 103, 1433–1437 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J. A., Gregory S. M., Sivaraman V., Su L. & Damania B. Activation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 85, 895–904 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guggemoos S. et al. TLR9 contributes to antiviral immunity during gammaherpesvirus infection. J. Immunol. 180, 438–443 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. D. et al. Pivotal roles of cGAS-cGAMP signaling in antiviral defense and immune adjuvant effects. Science 341, 1390–1394 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gariano G. R. et al. The intracellular DNA sensor IFI16 gene acts as restriction factor for human cytomegalovirus replication. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002498 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyahira A. K., Shahangian A., Hwang S., Sun R. & Cheng G. TANK-binding kinase-1 plays an important role during in vitro and in vivo type I IFN responses to DNA virus infections. J. Immunol. 182, 2248–2257 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H. R. et al. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 encoding open reading frame 11 targets TANK binding kinase 1 to negatively regulate the host type I interferon response. J. Virol. 88, 6832–6846 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leang R. S. et al. The anti-interferon activity of conserved viral dUTPase ORF54 is essential for an effective MHV-68 infection. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002292 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit E. et al. Peroxisomes are signaling platforms for antiviral innate immunity. Cell 141, 668–681 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan M. et al. Trex1 regulates lysosomal biogenesis and interferon-independent activation of antiviral genes. Nat. Immunol. 14, 61–71 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoggins J. W. et al. Pan-viral specificity of IFN-induced genes reveals new roles for cGAS in innate immunity. Nature 505, 691–695 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei J. et al. Ligation of TLR2 and TLR4 on murine bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells triggers differential effects on their immunosuppressive activity. Cell. Immunol. 271, 147–156 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. MicroRNA-155 promotes autophagy to eliminate intracellular mycobacteria by targeting Rheb. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003697 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K. et al. miR-155 suppresses bacterial clearance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced keratitis by targeting Rheb. J. Infect. Dis. 210, 89–98 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargano L. M., Forrest J. C. & Speck S. H. Signaling through Toll-like receptors induces murine gammaherpesvirus 68 reactivation in vivo. J. Virol. 83, 1474–1482 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Alnemri T., Yu J. W., Datta P., Wu J. & Alnemri E. S. AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature 458, 509–513 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S. et al. Conserved herpesviral kinase promotes viral persistence by inhibiting the IRF-3-mediated type I interferon response. Cell Host Microbe 5, 166–178 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]