Abstract

Using data from Malawi, this study situates the discourse on migration, entrepreneurship, and development within the context of Africa’s social realities. It examines self-employment differences among three groups of migrants and corresponding group differences in agricultural and non-agricultural self-employment. International migrants are found to be more engaged in self-employment than internal-migrants. However, our results suggest that previous findings on the development-related contributions of returning migrants from the West need to be appropriately contextualized. When returnees from the West invest in self-employment, they typically shy away from Africa’s largest economic sector - agriculture. In contrast, levels of self-employment, especially in agricultural self-employment, are highest among returning migrants and immigrants from other African countries, especially from those nearby. We also underscore the gendered dimensions of migrants’ contribution to African development by demonstrating that female migrants are more likely to be self-employed in agriculture than male migrants. Furthermore, as human-capital increases, migrants are more likely to concentrate their self-employment activities in non-agricultural activities and not in the agricultural sector. The study concludes by using these findings to discuss key implications for policy and future research.

Introduction

Progress in the study of migration and development has resulted in a growing number of studies identifying critical issues around which policies can be developed. Previous research indicates, for example, that migrant remittances (Durand, Parrado and Massey 1996; Glytsos 2002; Russell 1992), investments from Diaspora communities (Gillespie et al 1999), and returning skilled professionals (Vertovec 2002) all contribute towards improved development outcomes. Also noted in prior research are the contributions of migrant entrepreneurs fully engaged in small-scale businesses playing a critical role in Africa’s development (Ammassari 2004; Black and Castaldo 2009). Within the continent, the expansion of such businesses has become more rapid in recent years. Moreover, increases in the number of small-scale businesses have been accompanied by the creation of new jobs. For example, estimates indicate that small-scale enterprises in Africa now employ about twice the number of employees found in the public sector (Mead and Liedholm 1998). Migrant entrepreneurs can therefore contribute to economic development by reducing unemployment rates along with investing needed resources into sectors with considerable future growth potentials (Kloosterman 2003). Among African countries, however, there is limited research on the dynamics of migration and self-employment and an even more limited understanding of self-employment differences across migrant types. Similarly, despite the well-known contributions of the agricultural sector to African development (de Janvry and Sadoulet 2010; Diao, Hazell, and Thurlow 2010), the nexus between migration and agricultural self-employment has not been sufficiently articulated in the existing literature.

Meaningful improvements in the discourse on African migration and self-employment can however be achieved by increasing scholarly attention to several issues. For example, the well-known tendency for African migrants to migrate within sub-regional systems (Agadjanian; 2008; de Haas 2007) needs to be incorporated into this scholarly discourse. Equally important is the need for spatial differences in entrepreneurial outcomes among migrants from nearby migration sub-systems and their counterparts from other regions need to be clarified. To the extent that migrants’ entrepreneurial activities extend beyond the outcomes of returning migrants, research also needs to systematically articulate variations in the dynamics of self-employment among other migrant groups (e.g. immigrants in Africa). Finally, research on migration and entrepreneurship needs to be contextualized to Africa’s social realities. In particular, migration discourses need to distinguish between the entrepreneurial activities of African migrants involved in the agricultural sector and those of their counterparts in non-agricultural sectors.

As a first step towards bridging these gaps in the literature, this study describes the relationship between migration and self-employment among individuals migrating in Africa’s largest migration system - the Southern African Migration Systems (SAMS). It uses recently released data from the Malawi 2008 census to examine three specific issues. First, following previous studies using self-employment as a measure of entrepreneurship (e.g. Hamilton 2000; Portes and Zhou 1996), it examines self-employment differences between individuals migrating to and from countries in the SAMS and their counterparts from other regions (e.g. Europe and North America). Second, the study links the scholarly discourse on migration and self-employment to Africa’s largest economic sector; agriculture. In the process, it clarifies migrants’ contributions to development by distinguishing between the contributions of immigrants, returning migrants, and internal migrants to agricultural self-employment. Finally, the study highlights the role of other social and demographic factors in contributing to self-employment differences by documenting the mediating influence of factors such as gender and levels of human-capital.

Background: The Malawian context

Malawi has many of the social and economic characteristics prevalent in Africa’s many developing countries. Given its sub-optimal economic performance, it is classified along with more than twenty other African countries, as a low-income economy by the World Bank (World Development Indicators 2013). It is also one of thirty-six African states with the lowest levels of human-development in the world (UNDP 2011). Indeed, more than half of its population lives on less than two dollars a day (World Development Indicators 2013)1. Like many of its African counterparts, however, Malawi’s economy is heavily dependent on agriculture (Lea and Hammer 2009), with overall production being driven by the activities of smallholder agriculturalists (Doward 1999; Orr 2000). While improvements in agriculture are expected to contribute towards development, the productivity of smallholders is routinely challenged by their limited access to credit, small plot sizes, and their high transportation costs (Chirwa 2009; Hazarika and Alwang 2003; Zant 2012). However, these costs are not insurmountable. As noted in previous research (Taylor et al. 2002), migration processes can provide a critical mechanism through which resources can be found to overcome these constraints.

Surprisingly, however, few systematic studies on migration in Malawi are found in the literature. Yet, the significance of internal and international migration in the country suggests that it can provide a useful context within which the dynamics of African migration and self-employment can be explored. As a result of its location in Southern Africa, Malawi’s international migration processes are better understood within the context of the Southern African Migration System (SAMS). At the core of the SAMS are Malawi and fourteen other countries forming the Southern African Development Community (Zuberi and Sibanda 2004). This system is Africa’s largest migration system (Agadjanian 2008) and principally revolves around the dynamism of the South African economy.

Malawi however serves as a major source of migrant labor within the SAMS. This is partly as a result of its comparatively low level of development and the corresponding attraction of its nationals to income earning opportunities within the region (Bryceson 2006; Kalipeni 1992; Wilson 1976). Bryceson (2006), for example, traces the origins of migration from Malawi to two of its prosperous neighbors, South Africa and Southern Rhodesia, to the first decade of the previous century. Botswana also emerged as a major destination for Malawian nationals migrating within SAMS in the post-independence period (van Dijk 2002; Oucho 2011). Since the start of the previous century, however, labor migration from Malawi to other countries within the SAMS has been on the increase. Between 1900 and 1972, for example, the percentage of Malawian nationals living abroad increased almost ten-fold (Kydd and Christiansen 1982). Estimates further indicate that between 1981 and 1991, the number of Malawian immigrants in Botswana increased by more than three hundred percent (Oucho 2011).

More recent international migration movements from Malawi involve movements to more distant destinations, including those in Europe and North America. Migrants to these western countries are typically skilled professionals such as doctors and nurses (Oderth 2002), making them occupationally distinct from their counterparts who mainly migrate to destinations within the SAMS. Malawian immigrants in South Africa, for example, are typically unskilled mine workers and agricultural laborers (Adepoju 2003). Moreover, some studies suggest that the majority of Malawian migrants to countries within SAMS originate from rural areas (Bryceson 2006).

Studies on return migration flows to Malawi are particularly limited in the literature. Yet, this limited body of work indicates that such movements have historically involved migrants returning from wealthier SADC countries to Malawi’s poor rural areas (Wilson 1976). More recent analysis underscores the fact that the composition of contemporary returning migrants now includes returnees from more distant countries, extending even to the European region (Avato, Koettl, and Sabates-Wheeler 2010). In general, however, the extent to which these returning migrants enhance their economic well-being is not well documented in the literature. One exception to this is a recent study that shows that returning migrants from South Africa experience greater improvements in their pre-migration economic status compared to their counterparts returning from Europe (Avato, Koettl, and Sabates-Wheeler 2011).

Both as a result of its relative poverty and its restrictive immigration policy (Oucho 2011), Malawi does not attract large numbers of immigrants from other countries. In fact, recent estimates indicate that immigrants account for only 2% of its total population (World Bank 2013). Its limited immigration flows are dominated by cross-border movements from neighboring countries such as Zambia, Tanzania, and Mozambique (Andersson 2006), and by regional immigrants from Zimbabwe (Zinyama 1990). Despite its limited economic opportunities, however, Malawi served as a major destination for refugees during the Mozambican civil war between 1977 and 1992; however, some of these refugees have since returned (Koser 1997). Although the employment dynamics associated with these movements have not been examined, former refugees living in Malawi are likely to have benefitted from the work of aid agencies promoting the need for them to become more self-sufficient and less dependent on their hosts (Oda 2011).

Internal migration movements are yet another dimension of the migration context of Malawi. These migration flows have historically been driven by structural changes in the country’s economy and the ways in which these changes create spatial differences in poverty and economic opportunity (Christiansen 1984). One such change involved the promotion of agriculture as a cornerstone of Malawi’s development strategy after independence, which created an increasing demand for internal migrant labor to meet the needs of its agricultural estates (Bryceson 2006). These ensuing migration movements were characterized by circular migration flows driven by traditional social norms discouraging the migration of families (Bryceson 2006; Mtika 2007). In more recent years, internal migration movements have been associated with the dissolution of marital relationships and the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Anglewicz 2011). Still, prevailing regional inequalities continue to drive economically motivated internal migration as migrants move in search of urban employment opportunities that have declined precipitously in recent years (Lewin, Fisher, and Bruce 2012).

Theoretical perspectives

In general, there are several theoretical explanations useful for examining the dynamics of migration in Malawi. Yet, for the purpose of this analysis three are of particular importance. First, neoclassical economic theory suggests that given Malawi’s high levels of poverty, international migration to comparatively wealthier countries is mainly driven by the pursuit of higher earnings (Massey et al. 1993). Under the neoclassical framework, however, returning migrants are considered to be failed migrants. In other words, they returned because they were unable to meet their original migration objectives (Adelman, Morett, and Tolnay 2001; Cassarino 2004; Reichert 2002). A second theoretical perspective is the New Economics of Labor Migration (NELM) theory. It argues, among other things, that migration is motivated by household strategies for accumulating resources elsewhere, driven by the absence of credit markets (Massey et al. 1994). From this perspective, Malawi’s internal and international migrants are assumed to be motivated by the need to accrue resources in more lucrative destinations. Moreover, returning migrants are considered to be successful migrants who are expected to use their savings to promote development (Constant and Massey 2002). A third theoretical approach, that of cumulative causation, predicts among other things that in poor communities, migration is sustained by its role in helping families experience economic mobility (Massey et al. 1993). In the case of Malawi, this perspective underscores the potential of migration for providing a channel for increasing productivity and overall standards of living.

Beyond these theoretical perspectives, specific insights into the relationship between migration and entrepreneurship are found in research on the outcomes of immigrants (Joona 2010; Kanas, van Tubergen, and van der Lippe 2009; Sanders and Nee 1996) and returning migrants (Vertovec 2002; Ammassari 2004; Black and Castaldo 2009). Complementary analyses are also provided by findings from recent studies examining the dynamics of entrepreneurship among internal migrants (Frtjers, et. al, 2011; Liu, 2011). In general, the apparent consensus in literature is that compared to their non-migrant counterparts, individuals from migrant groups are more likely to be self-employed. Rarely, however, are there comparisons among various types of migrants in the literature. Notwithstanding the lack of such comparisons, existing studies provide enough evidence to identify several theoretical determinants of self-employment differences among migrants.

The first of these is human-capital. Le (1999), for example, underscores the positive influence of human-capital on self-employment, which among other things is driven by the positive impact of education on individuals’ managerial abilities. Similar impacts are now noted in the migration literature. For example, King (2000) suggests that accumulated human capital in the form of education and training influences the self-employment outcomes of returning migrants. Piracha and Vadean (2010) however, distinguish between the self-employment outcomes of returning migrants performing own account work and those supporting paid employees and argue that the former have lower education levels than the latter. The human-capital nexus is also found in research on self-employment among immigrants and internal migrants. In their study of immigrant self-employment in the US, however, Sanders and Nee (1996) argue that foreign-educated immigrants have higher rates of self-employment, possibly because domestic employers consider foreign schooling inferior to domestic schooling. Among internal migrants, self-employment in the informal economy is also negatively associated with levels of schooling (Akrofi 2006; Todaro 1997). However, highly educated Africans, especially females, are now increasingly becoming engaged in self-employment in the informal sector of the economy (Wamuthenya 2010).

Human-capital perspectives have notable theoretical implications relevant to the objectives of this analysis. First, evidence showing higher levels of schooling among immigrants than returning migrants in Africa (Thomas, 2008), has implications for self-employment differences that are yet to be empirically investigated. Second, while previous studies discount the importance of schooling obtained abroad, it is not clear whether this consideration is equally relevant in the African context. Since education obtained abroad, especially in the West, tends to be more valued than that obtained locally (Alberts and Hazen, 2005), educated migrants from the West may be more desired by salaried employers, effectively decreasing their likelihood of being self-employed.

Accumulated financial resources are another set of determinants relevant to the relationship between migration and self-employment. Savings affect migrants’ ability to invest in property or spur the opening of a business, especially among migrants returning from abroad. Galor and Stark (1991), for example, note that impending return migration can spur higher productivity and greater savings, although they do not make the connection between accumulated savings and entrepreneurship upon return. Mesnard’s (2004) study, however, makes this connection by showing a positive effect of higher accumulated savings on the decision to become an entrepreneur. In addition, in Ilahi’s (1999) analysis of return migrants in Pakistani, accumulated savings were also found to be a critical determinant of occupational choice while higher savings were positively associated with the probability of self-employment.

The main implication of this tendency for returning migrants to use accumulated savings for self-employment is that, other things being equal, migrants returning from high-income countries in Europe and North America will have more resources than returnees from African countries. Furthermore, if returning migrants arrive with accumulated capital while immigrants and internal migrants are still in the process of accumulating capital, the latter two groups will have fewer resources to start their own businesses compared to migrants returning from abroad.

Individual-level factors such as duration of residence, and demographic factors such as age, are also important for understanding differences in self-employment. Recently arrived immigrants have lower levels of self-employment than long-term immigrants because, compared to the latter, the former typically have fewer start-up funds and a more limited knowledge of the local economy (Sanders and Nee 1996). At the same time, the impacts of duration of residence on self-employment among other migrants (e.g. returnees) are not well understood. In terms of age, self-employment among returning migrants has been shown to decrease with increasing age as older adults move towards retirement (Dustmann and Kirchkamp 2002).

Contextual predictors of migrant self-employment identified in prior research include factors such as overall economic conditions, household contexts, and place of residence (Black and Castaldo 2009; Cassarino 2004; Johanson and Adams 2004). For example, Black and Castaldo (2009) suggest that the economic climate within countries can affect the success of businesses set up by returning migrants. Household-level factors such as the receipt of remittances generally have a positive association with migrant self-employment (Taylor, Rozelle, and de Brauw 2003). Residence in urban or rural areas is, however, associated with contextual differences that affect both self-employment and type of self-employment activity. Accordingly, urban residence is typically associated with greater access to jobs in the formal sector of the economy, although increasing unemployment in African cities suggests that this urban advantage may be declining. Rural areas, in contrast, typically have a larger number of self-employment opportunities in small-scale agricultural enterprises (Johanson and Adams 2004). In rural areas, returning migrants have also been known to have significantly more investments in agricultural enterprises while their counterparts from urban areas typically invest in non-farm enterprises (McCormick and Wahba 2003). Although these differences have implications for self-employment across sectors, these implications have not been systematically examined across various types of migrants in African societies.

Hypotheses

The current study attempts to move the scholarly discourse on African migration and self-employment by systematically examining three hypotheses. First, it hypothesizes that native-born migrants returning from other countries will be more likely to be involved in self-employment compared to immigrants and internal migrants. These differences are expected because previous research indicates that returning international migrants arrive with accumulated resources and have higher levels of human capital than other migrants (Galor and Stark 1991; Thomas 2008). Internal migrant natives, however, are expected to have higher levels of self-employment than immigrants because, as natives, they are better positioned to exploit the local contextual factors known to positively affect self-employment (Cassarino 2004; Johanson and Adams 2004). The second hypothesis is that migrants (i.e., immigrants and returning migrants) from western countries will be more likely to be in waged/salaried employment than in self-employment. As suggested by Alberts and Hazen (2005), in African countries, education acquired abroad is more valued than education obtained locally. Therefore, migrants from the west are expected to have more opportunities for waged employment, and as such, compared to other migrants, they will have fewer incentives to be engaged in self-employment. Finally, the third hypothesis is that international migrants (returnees and immigrants) from countries closer to Malawi (SADC countries) will be more likely to be employed in the agricultural than non-agricultural sectors. In part, this expectation is based on the fact that international migration over shorter distances is expected to be less costly than long-distance migration (Ghatak, Mulhern, and Watson 2008). Given these cost differentials, low human-capital groups from rural areas are thus expected to be the most likely to use short-distance migration to nearby countries for purposes of capital accumulation in support of agricultural self-employment.

Data and Methods

The analysis uses data from a 10% sample of the Malawi 2008 census, available in the IPUMS-international database (Minnesota Population Center 2011). These data are especially suited for our study because they contain information on a range of measures, including data on demographic characteristics (e.g. age and sex), measures of human-capital (e.g. education), as well as migration (e.g. place of birth) and contextual indicators (e.g. place of residence). The final sample consists of adults between ages 25 and 65 who are currently employed. Focusing on this age-range increases the chances of including individuals who have completed their educational careers and are part of the working age population. Individuals directly observed to be enrolled in school are also dropped from the analysis.

The Malawi 2008 census also contains migration information such as respondents’ previous country or district of residence and years of residence in their current locations. Moreover, it contains other migration-related information such as place of birth and current place of residence. Altogether these data are used to identify three mutually exclusive migrant-groups. Immigrants are defined as foreign-born individuals; returning migrants as native-born individuals who previously lived in a country other than Malawi; and native-born internal migrants as native-born persons who previously lived in a different administrative unit of residence2. The latter group also excludes returning migrants. For the two broad groups of international migrants (i.e., returning migrants and immigrants), spatial differences in international migration are defined using information on country of origin (immigrants) and previous country of residence (returning migrants). Accordingly, the study distinguishes between the outcomes of international migrants from (1) Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries; (2) non-SADC African countries; (3) Europe and North America; and (4) a residual category of “other” regions.

Analytically, self-employment differences are examined in two stages using various types of multiple regression models. The first stage involves the examination of broad differences in self-employment among migrant groups. By restricting the analysis only to migrants we minimize the possible influences of selectivity differences that could bias the results when non-migrants are included in our comparisons. Information on whether individuals are involved in waged or self-employment is then used to construct a binary dependent variable (self-employed = 1; employed in waged/salaried jobs = 0). This dependent variable is used in logistic regression models in the form of:

| (1) |

where, logit S, the dependent variable, is the logit of the probability of self-employment versus waged/salaried employment; M a vector of migration status groups, and X, a vector of individual-level covariates such as human-capital (i.e., education, English proficiency), age, and gender. C captures two types of contextual influences. The first is place of residence (urban versus rural). The second includes measures of household contexts known to be associated with employment outcomes; these include household size and whether or not households receive remittances. Estimated coefficients for M are used to compare differences in self-employment across migrant types while those for X and C are used to examine the association between self-employment and factors such as education and place of residence.

In the second stage, the analysis focuses on differences in sectors of employment among migrants, especially in relation to the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors. Multinomial logistic regression models are thus used to examine these differences as;

| (2) |

where SE is a trichotomous dependent variable that takes the value of 0, if migrants are involved in waged/salaried employment; 1, if self-employed in the non-agricultural sector; and 2, if self-employed in agriculture. M, X, and C, represent the same values they represented in equation 1. Estimates from Model 2 are thus used to examine differences in self-employment in the agricultural or non-agricultural sectors relative to waged/salaried employment across migrant groups. All models are estimated using robust standard errors that adjust for clustering because individuals are nested within households.

Results

Descriptive findings

Summary characteristics of the three major migrant groups are presented in Table 1 and reveal important differences in the profiles of immigrants, returning migrants, and internal migrants. As expected, the majority of the immigration and return migration flows are from African countries. Regardless of the direction of international migration flows, however, shorter distance movements to SADC countries are the most dominant. For example, immigrants (83%) and returning migrants (64%) from SADC countries located within the SAMS accounted for the majority of migrants in the first two groups. In contrast, returning migrants (8%) and immigrants (3%) from Europe and North America account for a considerably smaller proportion of all migrants. Migrants in all three groups are however similar in terms of age and the number of years they have spent at their current places of residence. However, they also have notable differences in their gender distributions. In particular, although each group is male-dominated, males represent a much higher proportion of workers among returning migrants and internal migrants compared to immigrants.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of returning migrant, immigrant, and internal-migrant workers in the sample

| Immigrants | Native-born returnees | Native-born internal migrants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Region of origin (%) | |||

| SADC region | 82.5 | 63.9 | - |

| Non-SADC African countries | 5.1 | 5.5 | - |

| North America or Europe | 2.9 | 8.04 | - |

| Other world regions | 9.5 | 22.6 | - |

| Duration of residence in years (Mean) | 20 | 17.4 | 21.8 |

| Age (Mean) | 40.5 | 40.1 | 37.6 |

| Males (%) | 55.7 | 64.1 | 60.3 |

| Place of residence | |||

| Urban (%) | 26 | 18.9 | 25.2 |

| Household characteristics | |||

| Family size (Mean) | 5.7 | 5.6 | 5.3 |

| Households with remittances (%) | 4.4 | 7.8 | 0.02 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 5.22 | 3.72 | 5.5 |

| Married | 81 | 86.5 | 83.1 |

| Other | 13.78 | 9.78 | 11.4 |

| Educational attainment | |||

| No school | 22.6 | 19.42 | 20.8 |

| Primary | 46.6 | 55.9 | 50.8 |

| Secondary | 23.8 | 20.92 | 24.6 |

| Post-secondary | 7 | 3.76 | 3.8 |

| English proficient (%) | 49.8 | 49.3 | 46.5 |

| N | 7,338 | 2,476 | 111,015 |

Data source: 10% sample of the Malawi 2008 census

Apart from these demographic differences, the groups also differ in terms of their contextual indicators. Returning migrants, for example, are distinctively less likely to live in urban areas compared to immigrants or internal migrants. However, the overall percentages living in urban areas are generally low across groups underscoring the fact that contemporary Malawian society is still predominantly rural. Another contextual difference among the groups has to do with the percentage of households receiving remittances from migrants abroad. Clearly, returning migrants live in such households in greater proportions than do other migrants. If household remittances are used more for investments than for consumption, these differences will have important ramifications for differences in the availability of the resources needed to invest in self-employment activities.

In terms of human-capital profiles, Table 1 shows that immigrants are the most likely to have secondary and post-secondary education. On average, native returning migrants have the lowest levels of education with about 72% of workers having only primary schooling or no schooling at all. Previous studies underscore the significance of another human-capital attribute – language ability - for immigrants’ labor market outcomes (Dustmann and Fabri 2003). In this regard, however, the census does not contain information on local languages in Malawi but only information on its official language, English. As the results indicate, all three migrant groups are broadly similar with regard to their levels of English proficiency, suggesting that schooling differences will possibly be the major human-capital influence driving differences in self-employment outcomes.

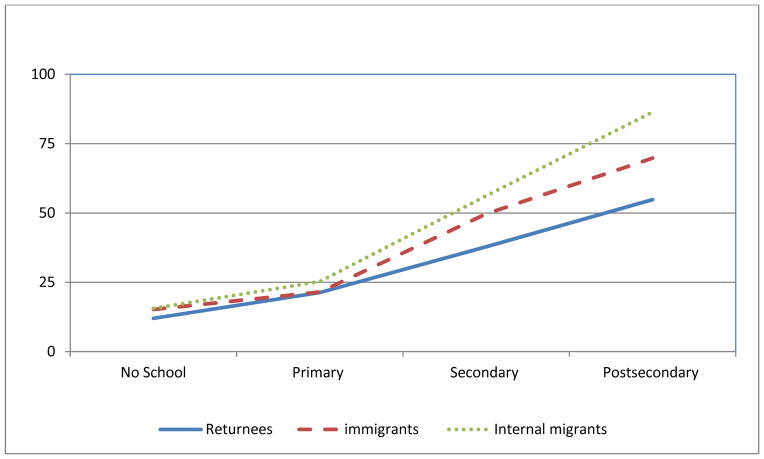

To assess schooling differences across various spatial migration movements, Figure 1 presents educational distributions of returning migrants and immigrants originating from various regions of the world. Focusing on the highest (post-secondary) and lowest (no schooling) points in the educational distribution, it shows that schooling levels are clearly the least favorable among returning migrants from SADC and non-SADC African countries. In comparison, immigrants from Europe and North America, and their counterparts from non-SADC African countries, and other world regions, have some of the highest levels of educational attainment. As far as educational credentials are concerned, therefore, returning migrants, especially those returning from African countries, are likely to face the greatest constraints to securing employment in the formal waged sector.

Figure 1.

Educational differences among migrant workers in the sample

Figure 2 provides a first estimation of the implications of human-capital differences for migrants’ employment patterns. For analytical simplicity, these estimates focus on the three broad migrant groups and do not incorporate spatial differences. Consistent with expectations, the prevalence of waged/salaried employment rather than self-employment is consistently greater among workers with higher than lower levels of schooling. Irrespective of educational attainment, however, returning migrants are generally the least likely to have jobs in the wage/salary sector. Another observation shown in the figure is that the educational gradient in waged-employment differs across groups. Accordingly, returning migrants experience the lowest increases in proportions in waged employment as schooling increases compared to immigrants and internal migrants.

Figure 2.

Distribution of migrant workers involved in waged employment by educational attainment

Consistent with research showing that many returning migrants encounter difficulties reintegrating into the labor force (Arowolo 2000), returning migrants in the sample appear to have the greatest incentive to pursue employment opportunities outside the formal waged sector. In fact, on average, the percentage of waged/salaried workers is lowest among returning migrants (24.2%) than among immigrants (30.2%) and internal migrants (33.2%). Separate analysis of the data (not shown) indicates that all three groups had higher proportions in waged rather than self-employment compared to non-migrants (16.8%) and were at or above the national average (24.4%).

Multiple regression results

Coefficients from logistic regression models examining the determinants of self-employment compared to waged employment are presented in Table 2. Model 1, the baseline model, presents results accounting for differences in migration status as well as differences in demographic characteristics. Again, the dependent variable is a binary outcome equal to 1 for individuals involved in self-employment and 0 for those in waged/salary employment. Several observations can be made from these estimates. For example, they demonstrate that returning migrants arriving from nearby countries (i.e., those in the SADC), have the highest likelihood of being self-employed rather than in waged employment. Furthermore, groups of international migrants (i.e. immigrants and returning migrants) originating from African countries are significantly more likely to be self-employed than native-born internal migrants, the reference group. For example, returning migrants and immigrants from non-SADC Africa are still more likely to be self-employed than internal migrants, despite the fact that they have a lower likelihood of self-employment than returnees from SADC countries. Migrants moving between African countries, are thus more likely to be self-employed than migrants moving within Malawi. At the same time, the results indicate that in terms of self-employment internal migrants are not significantly different from immigrants and returning migrants from Europe and North America. Model 1 further indicates that self-employment ventures are mainly driven by the activities of female migrants. This suggests that the increasing feminization of African migration flows discussed in prior studies (Adepoju 2004), may be accompanied by higher levels of entrepreneurship among females compared to male migrants.

Table 2.

Coefficients from logistic regression models examining the predictors of self-employment versus waged employment

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Migration status and origins | |||

| Native-born returning migrants | |||

| From SADC countries | 0.61*** | 0.71*** | 0.55*** |

| From non-SADC African countries | 0.40* | 0.57** | 0.57** |

| From North America and Europe | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.40* |

| From other world regions | 0.24* | 0.53*** | 0.60*** |

| Immigrants | |||

| From SADC countries | 0.11*** | 0.24*** | 0.21*** |

| From non-SADC African countries | 0.54*** | 1.32*** | 1.36*** |

| From North America and Europe | −0.15 | 0.38* | 0.37* |

| From other world regions | −0.30** | 0.28** | 0.33** |

| Native-born internal migrants (Reference) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) |

| Age | 0.01*** | −0.02*** | −0.02*** |

| Females (Yes=1) | 0.92*** | −0.67*** | 0.72*** |

| Duration of residence | 0.02*** | 0.01*** | |

| Educational attainment | |||

| Post-secondary | −2.63*** | −2.40*** | |

| Secondary | −1.23*** | −1.07*** | |

| Primary | −0.23*** | −0.21*** | |

| No Schooling (Reference) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| English proficient (Yes =1) | −0.40*** | −0.35*** | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | −0.01 | ||

| Married | 0.24*** | ||

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated (Reference) | (0.00) | ||

| Urban residence (Yes=1) | −0.60*** | ||

| Family size | 0.01** | ||

| Households with remittances | 0.09 | ||

| Constant | 0.17*** | 1.54*** | 1.37*** |

| Log pseudo likelihood | −73834 | −65218 | −64431 |

| N | 120,829 | 120,829 | 120,829 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

In Model 2, we examine the extent to which self-employment differences in the baseline model are mediated by differences in human-capital endowments. Accordingly, after controlling for education and English proficiency, substantial comparative increases are observed in the likelihood of self-employment among immigrants from non-SADC African countries. One interpretation of this finding is that immigrants from non-SADC Africa had lower self-employment rates than returnees from SADC countries in Model 1 because of the former’s comparatively higher levels of schooling. In other words, this schooling advantage allows immigrants from non-SADC African countries to compete more favorably for jobs in the formal waged sector resulting in their lower levels of self-employment in Model 1. Additionally, when human-capital differences are accounted for in Model 2, immigrants from Europe and North America become slightly more likely to be self-employed than internal-migrants, but not in comparison to returning migrants from African countries. More generally, Model 2 confirms that the likelihood of self-employment is negatively associated with increasing levels of human-capital. Thus, the likelihood of self-employment declines with increasing levels of educational attainment and English proficiency.

Additional indicators capturing differences in marital status and contextual measures are accounted for in Model 3. Nevertheless, few notable changes are observed among migrant groups. One of these is that among returning migrants, those from SADC countries become about as likely to be self-employed as their counterparts from non-SADC African countries and countries in other world regions. This suggests that contextual factors, such as the distribution of migrants across urban and rural areas, partly account for some of the initial differences observed in Model 1. As expected, urban residents are less likely to be engaged in self-employment compared to rural residents. Furthermore, no significant differences in self-employment are found between workers from households receiving remittances compared to those from households that don’t.

In Table 3, results from multinomial regression models are used to examine the larger question of whether self-employed migrants are differentially engaged in the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors. These differences are important because they provide one way to assess migrants’ engagement in the economic sector most crucial to Africa’s development prospects. Model 1 shows comparisons between groups net of age and sex differences. Accordingly, this baseline model indicates that returning migrants from SADC countries are the most likely to be self-employed in the agricultural sector compared to other migrants. Furthermore, these returnees from nearby countries are more likely to be self-employed in agriculture than in the non-agricultural sector, relative to the baseline indicator of waged-employment. Immigrants from non-SADC African countries are likewise more likely to be self-employed in the agricultural than non-agricultural sectors. In sum, these baseline patterns show that agricultural self-employment has a strong positive association with return migration from Southern African countries and immigration from non-SADC African countries.

Table 3.

Coefficients from multinomial regression models examining the predictors of agricultural self-employment versus non-agricultural self-employment, compared to waged employment

| Self-employed in Agriculture vs. Waged Employment | Self-employed in the non-Agricultural sector vs. Waged Employment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Migration status and origins | ||||||

| Native-born returning migrants | ||||||

| From SADC countries | 0.62*** | 0.78*** | 0.53*** | 0.59*** | 0.64*** | 0.59*** |

| From non-SADC African countries | 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.57** | 0.68** | 0.68** |

| From North America and Europe | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.39* | 0.51* | 0.52* |

| From other world regions | 0.53*** | 0.91*** | 1.15*** | −0.17 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Immigrants | ||||||

| From SADC countries | 0.05 | 0.21*** | 0..16*** | 0.18*** | 0.27*** | 0.26*** |

| From non-SADC African countries | 0.57*** | 1.54*** | 1.64*** | 0.50** | 1.17*** | 1.18*** |

| From North America and Europe | −0.26 | 0.32 | 0.25 | −0.03 | 0.42* | 0.44* |

| From other world regions | −0.37*** | 0.30* | 0.36** | −0.22* | 0.27* | 0.29* |

| Native-born internal migrants (Reference) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) |

| Age | 0.01*** | −0.02*** | −0.01*** | 0.00 | −0.02*** | −0.02*** |

| Females (Yes=1) | 1.22*** | 0.94*** | 1.05*** | 0.54*** | 0.39*** | 0.42*** |

| Duration of residence | 0.02*** | 0.01*** | 0.01*** | 0.01*** | ||

| Educational attainment | ||||||

| Post-secondary | −3.42*** | −2.91*** | −2.07*** | −2.05*** | ||

| Secondary | −1.59*** | −1.26*** | −0.86*** | 0.85*** | ||

| Primary | −0.32*** | −0.26*** | −0.07** | 0.08** | ||

| No Schooling (Reference) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||

| English proficient (Yes =1) | −0.50*** | −0.40*** | −0.30*** | −0.30*** | ||

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Single | 0.11* | −0.12** | ||||

| Married | 0.37*** | 0.12*** | ||||

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated (Reference) | (0.00) | (0.00) | ||||

| Urban residence (Yes=1) | −1.59*** | −0.04 | ||||

| Family size | 0.03*** | 0.00 | ||||

| Households with remittances | −0.07 | 0.20*** | ||||

| Constant | −0.79*** | 0.86*** | 0.53*** | −0.23*** | 0.76**** | 0.69*** |

| Log likelihood | −128430 | −118605 | −115299 | −128430 | −118605 | −115299 |

| N | 120829 | 120829 | 120829 | 120829 | 120829 | 120829 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Unlike migrants from these groups, however, most other international migrants concentrate the bulk of their self-employment activities away from the agricultural sector. Returning migrants from Europe and North America, for example, are almost four times more likely to be self-employed in the non-agricultural sector than in agriculture. Furthermore, no significant association is found between agricultural self-employment and immigration from North America and Europe. International migrants from more prosperous economies in western countries, where better opportunities for resource accumulation are available, are apparently among the least likely to be engaged in agricultural self-employment.

Model 2 includes additional controls for differences in human-capital. Consequently, immigrants from non-SADC African countries experience an increased likelihood of self-employment compared to returning immigrants from SADC countries, but only in the agricultural sector. Notably, however, accounting for human-capital differences does not reverse the lack of statistically significant findings concerning agricultural self-employment among immigrants and returning migrants from Europe and North America. Accordingly, the higher levels of human-capital of these migrants do not explain their lack of any meaningful engagement in entrepreneurship in the agricultural sector. Instructively, Model 2 shows an interesting relationship between educational attainment and sector of employment. As levels of schooling increase, migrant workers are especially more likely to shy away from agricultural than non-agricultural forms of self-employment. Similarly, being proficient in English is associated with a lower likelihood of self-employment in the agricultural than non-agricultural sectors.

A salient finding shown in all three models is that female migrants are more likely to be self-employed in agriculture than male migrants. Moreover, female migrants are also more likely to be concentrated in agricultural than non-agricultural self-employment. This observation is consistent with previous research underscoring the role of females in the agricultural development in African societies (Gawaya 2008; Linares 2009). Contextual indicators accounted for in Model 3 provide added insight into the determinants of sector of self-employment. Living in urban areas is associated with significantly less focus on agricultural than non-agricultural self-employment. In addition, workers from larger households are more likely to be self-employed in agriculture than in other sectors, consistent with the positive association between large family sizes and the provision of household labor in agricultural societies (White 2002). In terms of households’ receipt of remittances, the results surprisingly suggest that these receipts are associated with a greater likelihood of self-employment in the non-agricultural sector, and not in agriculture. This suggests that when households use remittances for investments rather than consumption, these investments contribute more towards entrepreneurship outside the agriculture sector than to the promotion of small-holder agricultural self-employment.

Discussion and Conclusions

Population mobility between poor African countries such as Malawi and their wealthier neighbors underlie the fundamental dynamics of migration within Africa’s major migration systems. These dynamics however can be examined in ways that inform policies designed to help African countries exploit the contributions of migration processes to development. Despite increasing research on migration and development, there are limited studies on the self-employment outcomes of migrants in key sectors fundamental to Africa’s quest for development. Using these limitations as essential points of entry, our analysis moves the discourse on migration and development in several directions. For example, it demonstrates the need to move beyond the traditional focus on returning migrants in the literature on migrants’ contribution to development. Furthermore, it shows that the consideration of migration as a multidimensional process encompassing immigrants, internal migrants, and returning migrants is essential for a more comprehensive understanding of these contributions. By using self-employment as its outcome of interest, the study has directly interrogated the material contributions of migrants to the reduction of unemployment and the creation of migrant-owned businesses. Both processes can directly affect economic productivity and poverty-reduction processes in poor African countries. In the process of addressing these and other issues in the analysis, our results have produced specific insights that make critical contributions to the existing literature.

First, they suggest that the potential entrepreneurial contributions of African migrants from western countries lauded in prior studies needs to be interpreted with caution. While these migrants have the financial wherewithal to invest in entrepreneurship, they are not as engaged in self-employment activities as their counterparts from African countries. Critical concerns are also raised about their contributions to Africa’s largest economic sector. As the results show, migrants from the west are particularly less likely to be engaged in agricultural self-employment. Our results also make the case for a greater incorporation of immigrant outcomes into research on migrant self-employment in Africa. They demonstrate that the immigrants who contribute the most to agricultural self-employment were themselves prior residents of African societies where agricultural economies are predominant. In contrast to the abundance of studies on self-employment among immigrants in the west, however, the literature on immigrant entrepreneurship in Africa is comparatively weaker.

Significantly, the analysis indicates that among immigrants and returnees from western countries, the possession of human-capital attributes desirable by employers in the formal waged sector does not explain their comparatively limited engagement in self-employment. Returning migrants and immigrants from these countries are also not limiting their contributions to agricultural self-employment because their human-capital is needed elsewhere. Several explanations can still account for these observations. For example, migrants from western countries may have limited access to information on land acquisition or on the availability of opportunities for agricultural self-employment. Additionally, they may not want to return to the status quo but may have strong intentions of returning back to the west. Consequently these migrants may be diffident towards making tangible investments in the creation of jobs for themselves. Irrespective of what the limiting factors are, policy makers will need to develop better strategies to increase the interest of these migrants in self-employment activities.

A third insight stemming from these analyses is that spatial differences in migration flows need to be better integrated into theoretical discourses on the economic outcomes of migrants. Observed self-employment differences in the analysis fall along a spatial continuum; this is exemplified by the differential outcomes of individuals migrating within national borders (i.e., internal migrants), international migrants from nearby countries (i.e. SADC countries), and international migrants from more distant regions. For example, although returning migrants generally had high probabilities of self-employment, these probabilities were even higher among migrants returning from SADC countries, followed by returnees from other African countries. A less defined pattern is also found among immigrants; individuals immigrating from non-SADC African countries were more likely to be self-employed compared to immigrants originating from outside Africa.

Several possible factors can account for these spatial differences. Lower levels of self-employment among internal-migrants compared to international migrants, for example, could reflect the fact that resources needed for starting owner-operated businesses are less available within the boundaries of poor countries such as Malawi. In fact, the results suggest that it is among groups with the lowest levels of human-capital that individuals are more likely to use international migration as a poverty mitigating strategy to overcome the financial constraints to self-employment. Specifically, migrants who are more likely to be self-employed (i.e., returning migrants) are particularly more likely to live in rural areas (Table 1) or have limited or no schooling (Figure 1), which makes them uncompetitive in the market for waged/salaried labor. Instructively, internal migrants also have similar educational characteristics, at least in comparison to returning migrants from SADC and non-SADC African countries (Figure 1). Despite these similarities, however, internal-migrants are less likely to be self-employed than these returning migrants, underscoring the role of international migration and subsequent return in the provision of better self-employment outcomes.

Our results also have a number of implications for policy and future research. At least with regard to policies on agricultural development, our results are useful for identifying key stake-holders to be targeted by strategies designed to improve outcomes. Obviously, the first of these include returning migrants from nearby countries in the SAMS (i.e., SADC countries) and those from the rest of Africa. Policy makers should nevertheless avoid discounting the contributions of returning migrants and immigrants from the west. Since these migrants theoretically have access to higher wage-earning opportunities abroad, improving their access to information on self-employment opportunities in the agricultural sector may also help to improve outcomes. Female migrants constitute another group of stake holders emerging from our results. As the analysis shows, they are collectively more likely to be self-employed in agriculture than male migrants.

More broadly, the relevance of these implications extends beyond Africa to other developing regions. For example, despite rapid industrialization in Asia, agriculture still makes a major contribution to the region’s economy, while the demographic landscape is increasingly characterized by high levels of migration (Deshingkar 2006; Fields 1994). Our results thus raise the possibility that return migration from vibrant Asian economies can be harnessed to create positive impacts on entrepreneurship to facilitate development. So far, evidence for such influences has mainly been found in China (Démurger and Xu, 2011). However, our results suggest that there is a need for examining the potential of these impacts in other countries as well. Furthermore, they underscore the need for research on the ways in which female migrants influence local entrepreneurship in the region.

Across international contexts, the analysis points to critical issues relevant to more extensive research on the effects of migration on development. For example, transnational business activities are likely to be easier to navigate across shorter than longer distances. As such, they may explain the high levels of entrepreneurship we find among international migrants returning from shorter distances. Such effects are generally understudied in the migration literature; yet they need to be examined more extensively across world regions. More precise channels through which migrant self-employment among affects development also need to be identified. Although our finding on the positive association between return migration and self-employment is instructive, more nuanced studies are needed for assessing how specific pathways (e.g., increased investment in land, labor, or transportation) facilitate returning migrants’ contribution to self-employment.

Other possibilities for future research are associated with the need to increase the knowledge base for understanding the link between migration and self-employment in developing contexts. In particular, the absence of data on whether internal migrants originated from rural or urban areas limited our ability to link self-employment outcomes with specific types of internal migration flows. Our current understanding of how self-employment affects migrant wages is similarly compromised by the lack of reliable data on migrant wages in African countries. Apart from these data needs, future research also needs to incorporate diverse methodological approaches to better understand the broader dynamics of migrant self-employment. Qualitative methods, for example, could provide more insight into the motivations, processes, and contexts in which self-employment occurs. Furthermore, longitudinal methods will be more able to enhance our understanding of how local economic trends influence self-employment operations. With these developments, future studies will be able to more thoroughly expand our understanding of the implications of migrant self-employment in Africa. In doing so, they will provide new insights that will expand knowledge on the relationship between migration, self-employment, and development in sub-Saharan Africa.

Footnotes

The extent to which Malawi’s high levels of poverty are associated with its unemployment situation is unclear. The country is reported as having an unemployment rate of only 3%. However, this estimate is very strongly contested by experts who argue that it is inaccurate (Nyasa Times 2012).

The census does not contain information on whether or not internal migrants were moving from rural or urban areas.

Contributor Information

Kevin J. A. Thomas, Email: kjt11@psu.edu, Department of Sociology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16801

Christopher Inkpen, Email: csi105@psu.edu, Department of Sociology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16801.

References

- Adelman RM, Morett C, Tolnay SE. Homeward bound: the return migration of southern-born black women, 1940 to 1990. Sociological Spectrum. 2000;20(4):433–463. [Google Scholar]

- Adepoju A. Continuity and changing configurations of migration to and from the Republic of South Africa. International Migration. 2003;41(1):3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Adepoju A. Trends in international migration in and from Africa. In: Massey DS, Taylor JE, editors. International Migration: Prospects and Policies in a Global Market. Oxford University Press; New York: 2004. pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian V. Research on international migration within sub-Saharan Africa: Foci, approaches, and challenges. The Sociological Quarterly. 2008;49(3):407–421. [Google Scholar]

- Akrofi EO. Urbanization and the Urban Poor in Africa. presented at the 5th FIG Regional Conference; Accra, Ghana. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alberts H, Hazen HD. There are always two voices:International Students’ Intentions to Stay in the United States or Return to their Home Countries. International Migration. 2005;43 (3):131–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ammassari S. From nation-building to entrepreneurship: the impact of élite return migrants in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. Population, Place, and Space. 2004;10(2):133–154. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson JA. Informal moves, informal markets: International migrants and traders from Mzimba district, Malawi. African Affairs. 2006;105(420):375–397. [Google Scholar]

- Anglewicz P. Migration, marital change, and HIV infection in Malawi. Demography. 2011;49(1):239–265. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0072-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arowolo OO. Return Migration and the Problem of Reintegration. International Migration. 2000;38(5):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Avato J, Koettl J, Sabates-Wheeler R. Social security regimes, global estimates, and good practices: the status of social protection for international migrants. World Development. 2010;38(4):455–466. [Google Scholar]

- Black R, Castaldo A. Return Migration and Entrepreneurship in Ghana and Cote D’Ivoire: The Role of Capital Transfers. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie. 2009;100:44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bryceson DF. Ganyu casual labor, famine and HIV/AIDS in rural Malawi: causality and casualty. Journal of Modern African Studies. 2006;44(2):173–202. [Google Scholar]

- Jean-Pierre Cassarino. Theorising Return Migration: the Conceptual Approach to Return Migrants Revisited. International Journal on Multicultural Societies. 2004;6(2):253–279. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Chirwa Ephraim W. Access to land, growth and poverty reduction in Malawi. The Intergovernmental Group of Twenty-Four on International Monetary Affairs and Development (G-24) 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen R. The Pattern of Internal Migration in Response to Structural Change in the Economy of Malawi 1966–77. Development and Change. 1984;15(1):125–151. [Google Scholar]

- Amelie Constant, Massey Douglas S. Return Migration by German Guestworkers: Neoclassical versus New Economic Theories. International Migration. 2002;40(4):5–38. [Google Scholar]

- De Janvry A, Sadoulet E. Agriculture for Development in Africa: Business-as-Usual or New Departures. African Economies. 2010;19(Suppl 2):ii7–ii39. [Google Scholar]

- de Haas H. Working paper 6. International Migration Institute, University of Oxford; 2007. North African migration systems: evolution, transformations and development linkages. [Google Scholar]

- Deshingkar Priya. Internal migration, poverty and development in Asia: including the excluded. IDS Bulletin. 2006;37(3):88–100. [Google Scholar]

- Diao X, Hazell P, Thurlow J. The Role of Agriculture in African Development. World Development. 2010;38(10):1375–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Dorward Andrew. Farm size and productivity in Malawian smallholder agriculture. The Journal of Development Studies. 1999;35(5):141–161. [Google Scholar]

- Durand J, Parrado EA, Massey DS. Migradollars and Development: A Reconsideration of the Mexican Case. International Migration Review. 1996;30(2):423–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dustmann C, Fabbri F. Language proficiency and labour market performance of immigrants in the UK. The Economic Journal. 2003;113(489):695–717. [Google Scholar]

- Dustmann C, Kirchkamp O. The optimal migration duration and activity choice after re-migration. Journal of Development Economics. 2002;67(2):351–372. [Google Scholar]

- Fields GS. The migration transition in Asia. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal. 1994;3(1):7–30. doi: 10.1177/011719689400300102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frijters P, Kong T, Meng X. IZA Discussion Paper No. 5967. 2011. Migrant Entrepreneurs and Credit Constraints Under Labour Market Discrimination. [Google Scholar]

- Galor O, Stark O. The Probability of Return Migration, Migrants’ Work Effort and Migrants’ Performance. Journal of Development Economics. 1991;35(2):399–405. doi: 10.1016/0304-3878(91)90058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawaya R. Investing in women farmers to eliminate food insecurity in southern Africa: policy-related research from Mozambique. Gender and Development. 2008;16(1):147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie K, Riddle L, Sayre E, Sturges D. Diaspora Interest in Homeland Investment. Journal of International Business Studies. 1999;30(3):623–634. [Google Scholar]

- Glytsos NP. The Role of Migrant Remittances in Development: Evidence from Mediterranean Countries. International Migration. 2002;40(1):5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ghatak S, Mulhern A, Watson J. Inter-Regional Migration in Transition Economies: The Case of Poland. Review of Development Economics. 2008;12(1):209–222. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BH. Does Entrepreneurship Pay? An Empirical Analysis of the Returns to Self-Employment. Journal of Political Economy. 2000;108(3):604–631. [Google Scholar]

- Hazarika Gautam, Jeffrey Alwang. Access to credit, plot size and cost inefficiency among smallholder tobacco cultivators in Malawi. Agricultural Economics. 2003;29(1):99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ilahi N. Return Migration and Occupational Change. Review of Development Economics. 1999;3(2):170–186. [Google Scholar]

- Johanson RK, Adams AV. Skills Development in sub-Saharan Africa. Regional and Sectoral studies, the World Bank; Washington, D.C: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Joona PA. Exits from Self-Employment: Is There a Native-Immigrant Difference in Sweden? International Migration Review. 2010;44(3):539–559. [Google Scholar]

- Kalipeni E. Population redistribution in Malawi since 1964. Geographical Review. 1992;82(1):13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kanas A, van Tubergen F, van der Lippe T. Immigrant Self-Employment Testing Hypotheses about the Role of Origin- and Host-Country Human Capital and Bonding and Bridging Social Capital. Work and Occupations. 2009;36(3):181–208. [Google Scholar]

- King R. Generalizations from the History of Return Migration. In: B, editor. Return Migration: Journey of Hope or Despair? United Nations, New York: 2000. pp. 7–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman R. Creating opportunities: Policies aimed at increasing openings for immigrant entrepreneurs in the Netherlands. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development: An International Journal. 2003;15(2):167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Koser K. Information and repatriation: the case of Mozambican refugees in Malawi. Journal of Refugee Studies. 1997;10(1):1–17. doi: 10.1093/jrs/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kydd J, Christiansen R. Structural Change in Malawi since Independence: Consequences of a Development Strategy Based on Large-scale Agriculture. World Development. 1982;10(5):355–375. [Google Scholar]

- Le AT. Empirical studies on self-employment. Journal of Economic Surveys. 1999;13(4):381–416. [Google Scholar]

- Lea N, Hammer L. Constraints to Growth in Malawi. The World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 5097 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Lewin P, Fisher M, Weber B. Do rainfall conditions push or pull rural migrants: evidence from Malawi. Agricultural Economics. 2012;43(2):191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Linares OF. From past to future agricultural expertise in Africa: Jola women of Senegal expand market-gardening. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(50):21074–21079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910773106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. Human capital, migration and rural entrepreneurship in China. Indian Growth and Development Review. 2011;4(2):100–122. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Arango Joaquin, Hugo Graeme, Kouaquci Ali, Pellegrino Adela. Theories in International Migration: A Review and Appraisal. Population and Development Review. 1993;19(3):431–466. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Arango Joaquin, Hugo Graeme, Kouaouci Ali, Pellegrino Adela. An Evaluation of International Migration Theory: The North American Case. Population and Development Review. 1994;20(4):699–752. [Google Scholar]

- Mead DC, Liedholm C. The dynamics of micro and small enterprises in developing countries. World Development. 1998;26(1):61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mesnard A. Temporary migration and capital market imperfections. Oxford Economic Papers. 2004;56(2):242–262. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick B, Wahba J. Return International Migration and Geographical Inequality: The Case of Egypt. Journal of African Economies. 2003;12(4):500–532. [Google Scholar]

- Minnesota Population Center. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 6.1 [Machine-readable database] Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mtika MM. Political economy, labor migration, and the AIDS epidemic in rural Malawi. Social Science and Medicine. 2007;64(12):2454–2463. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyasa Times. Experts dispute Malawi’s 3% unemployment rate-report. [Accessed, February 2, 2013];Nyasa Times. 2012 http://www.nyasatimes.com/2012/08/08/experts-dispute-malawis-3-per-cent-unemployment-rate-report/

- Oda Y. Speed and sustainability: Reviewing the long-term outcomes of UNHCR’s Quick Impact Projects in Mozambique. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Policy Development and Evaluation Services; October 2011.2011. [Google Scholar]

- Oderth R. Migration and Brain Drain: The Case of Malawi. Writers Club Press; Lincoln, Nebraska: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Orr Alastair. ‘Green Gold’?: Burley Tobacco, Smallholder Agriculture, and Poverty Alleviation in Malawi. World Development. 2000;28(2):347–363. [Google Scholar]

- Oucho JO. Institute for Security Studies, Paper 157. 2007. Migration in Southern Africa: Migration management initiatives for SADC member states. [Google Scholar]

- Piracha M, Vadean F. Return Migration and Occupational Choice: Evidence from Albania. World Development. 2010;38(8):1141–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Zhou M. Self-Employment and the Earnings of Immigrants. American Sociological Review. 1996;61(2):219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Reichert CV. Returning and New Montana Migrants: Socio-economic and Motivational Differences. Growth and Change. 2002;33(1):133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Russell S. Migrant remittances and development. International Migration. 1992;30(3–4):267–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders JM, Nee V. Immigrant Self-Employment: The Family as Social Capital and the Value of Human Capital. American Sociological Review. 1996;61(2):231–39. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JE, de Brauw Rozelle S. Migration and Incomes in Source Communities: A New Economics of Migration Perspective from China. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 2003;52(1):75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KJ. Return Migration in Africa and the relationship between educational attainment and labor market success: Evidence from Uganda. International Migration Review. 2008;43(3):652–674. [Google Scholar]

- Todaro MP. Urbanization, Unemployment, and Migration in Africa: Theory and Policy. Population Council, Working paper no. 104 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk R. ASC Working paper. Leiden, the Netherlands: 2002. Localising anxieties: Ghanian and Malawian immigrants, rising xenophobia, and social capital in Botswana. [Google Scholar]

- Vertovec S. Transnational Networks and Skilled Labour Migration. WPTC-02-02 presented at the Ladenburger Diskurs “Migration” conference; February 2002.2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wamuthenya WR. Determinants of Employment in the Formal and Informal Sectors of the Urban Areas of Kenya. African Economic Research Consortium, Research Paper 194; Nairobi, Kenya. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- White H. Combining Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in Poverty Analysis. World Development. 2002;30(3):511–522. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson F. International Migration in Southern Africa. International Migration Review. 1976;10(4):451–488. [Google Scholar]

- Zant W. How does Market Access affect Smallholder Behavior? The Case of Tobacco Marketing in Malawi. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper 12-088/V 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Zinyama LM. International Migrations to and from Zimbabwe and the Influence of Political Changes on Population Movements, 1965–1987. International Migration Review. 1990;24(4):748–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuberi T, Sibanda A. How do Migrants Fare in a Post-Apartheid South African Labor Market? International Migration Review. 2004;38(4):1642–1491. [Google Scholar]