Abstract

Background:

Stress-related mucosal disease occurs in many critically ill-patients within 24 h of admission. Proton pump inhibitor therapy has been documented to produce more potent inhibition of gastric acid secretion than histamine 2 receptor antagonists. This study aimed to compare extemporaneous preparations of omeprazole, pantoprazole oral suspension and intravenous (IV) pantoprazole on the gastric pH in intensive care unit patients.

Materials and Methods:

This was a randomized single-blind-study. Patients of ≥ 16 years of age with a nasogastric tube, who required mechanical ventilation for ≥ 48 h, were eligible for inclusion. The excluded patients were those with active gastrointestinal bleeding, known allergy to omeprazole and pantoprazole and those intolerant to the nasogastric tube. Fifty-six patients were randomized to treatment with omeprazole suspension 2 mg/ml (40 mg every day), pantoprazole suspension 2 mg/ml (40 mg every day) and IV pantoprazole (40 mg every day) for up to 14 days. Gastric aspirates were sampled before and 1-2.5 h after the drug administration for the pH measurement using an external pH meter. Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 21.0).

Results:

In this study, 56 critically ill-patients (39 male, 17 female, mean age: 61.5 ± 15.65 years) were followed for the control of the gastric pH. On each of the 14 trial days the mean of the gastric pH alteration was significantly higher in omeprazole and pantoprazole suspension-treated patients than in IV pantoprazole-treated patients (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Omeprazole and pantoprazole oral suspension are more effective than IV pantoprazole in increasing the gastric pH.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal bleeding, omeprazole, pantoprazole, stress-related mucosal disease, suspension

Introduction

Stress-related mucosal damage can be turned up in almost 100% of the patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) and may be developed within 24 h after admission.[1,2] The incidence of clinically important gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, indicated as overt bleeding complicated by hemodynamic instability, low hemoglobin, and/or need for blood transfusion from stress-related mucosal disease (SRMD) is 3.5% in the ICU patients who are mechanically ventilated for ≥ 48 h.[3] In addition, this type of ulceration is accompanied by increasing the risk of mortality. Moreover, it prolongs the length of stay in the ICU.[3]

Although ischemia of the gastric mucosa leads to SRMD, the significant role of gastric acid in the development of mucosal damage and bleeding could not be ignored.[4,5,6] Thus, early preventive prophylaxis of the probable GI bleeding, by means of acid-reducing agents, in these patients is rational.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the most potent and long-lasting medications used for this purpose. It is now generally believed that the aim of acid suppression as the prophylaxis of SRMD is to maintain gastric pH above 4.[7] Omeprazole, which is the first member of the PPI class, is commercially available as a delayed-release capsule and is formulated as enteric-coated granules to be protected against acid degradation. This formulation of oral PPIs put constraints on their usage in critically ill-patients who are NPO and unable to swallow the solid forms of drugs and those who experience an alteration in GI function after major surgery.[8] An alternative method of delivery that allows an aqueous administration, while protecting the intact drug from acid degradation, is omeprazole suspension. Omeprazole suspension, which is administered to critically ill-patients on mechanical ventilation, has been shown to prevent upper GI bleeding as well as maintaining gastric pH above 5.5.[1] The anti-secretory effect of intravenous (IV) pantoprazole, another drug of this family, has been shown in several studies.[9,10,11] Pantoprazole is chemically more stable than other PPIs in higher pH conditions. It also provides earlier healing and superior pain relief in peptic ulcer and gastroesophageal reflux disease compared with omeprazole or histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs).[12,13]

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of an extemporaneously formulated pantoprazole suspension, omeprazole suspension and commercially available IV pantoprazole on the gastric pH of critically ill-patients. The secondary objective was to assess the incidence of upper GI bleeding and ventilator-associated pneumonia in the ICU patients.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The inclusion criteria were as follow: Patients older than 16 years old who were admitted to medical and surgical ICUs of National Research Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (NRITLD) with an anticipated stay of longer than 72 h. In addition, those who required mechanical ventilation for more than 48 h, had an Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) score of bigger than 11 at baseline,[14] and had a nasogastric or orogastric tube in place. Participants were eligible for GI prophylaxis based on up to date defined risk factors.[15] Other acid-reducing agents, including H2RAs and antacids, which may alter the gastric pH, were removed from the patient's medications before the trial. Patients were excluded from the study if any of the following criteria were met: (1) A status of “no cardiopulmonary resuscitation;” (2) delay longer than 48 h from the time of initial eligibility; (3) known hypersensitivity to PPIs including omeprazole or pantoprazole; (4) history of gastric surgery; (5) active GI bleeding; (6) significant risk of swallowing blood; (7) admission for upper GI surgery; (8) inability to take a suspension by nasogastric tube; and (9) end-stage liver disease.

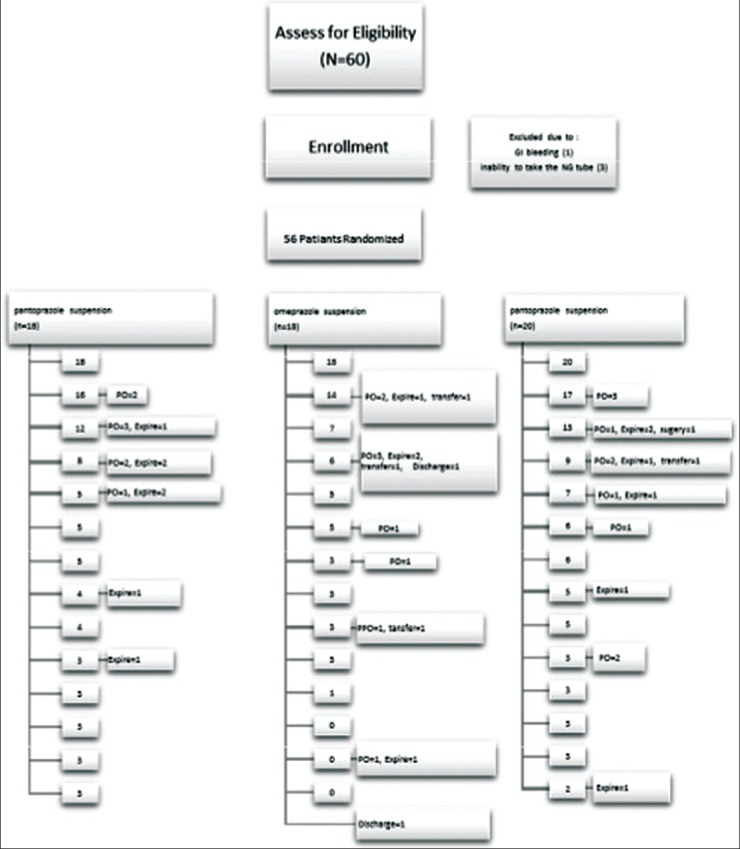

If any of the following events were the case, the trial would stop: (1) Removal of a nasogastric tube (2) death; and (3) discharge from the unit [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Reasons of discontinuation in treatment groups

Study design

The study was approved by the NRITLD Ethics Committee. Fifty-six patients were enrolled into this study. The study was a randomized, single-blind, uni-center study between October 2012 and September 2013.

Patients were randomly placed in three groups based on a random number table. Group A received immediate-release omeprazole oral suspension 2 mg/ml (40 mg daily), Group B received immediate-release pantoprazole oral suspension 2 mg/ml (40 mg daily) and Group C received IV pantoprazole (40 mg daily) for at least 24 h and up to 14 days depending on their survival, length of stay and removal of nasogastric tube. Omeprazole and pantoprazole suspension were administered via a nasogastric tube.

Extemporaneously preparation of the suspension

A 20 mg omeprazole capsule was opened, and the granules were added to 10 ml of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate to achieve a final concentration of 2 mg/ml. The enteric-coated omeprazole granules were allowed to disintegrate with gentle agitation, suspending the omeprazole in the sodium bicarbonate solution.[16] For the preparation of pantoprazole suspension, a similar procedure was followed. A 40 mg pantoprazole enteric-coated tablet triturated into a homogeny powder. The powder added to 20 ml of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate solution resulting in a concentration of 2 mg/ml.[16]

Gastric pH assay

Monitoring of gastric acidity (pH) began immediately before and 1-2.5 h after the drug administration in every trial day by means of an external pH meter (AZ 86502).[17] Due to the intermittent enteral feeding via the NG tube, enteral feeding was held for 2 h before the drug was given. If gastric aspirate contained “coffee-grounds” material, the sample was tested with gastroccult.

The primary end point included the mean gastric pH on each trial day. Additional end points were assessment of the incidence of upper GI bleeding and nosocomial pneumonia. For the diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia, we used Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score (CPIS) described by Pugin et al.[18] CPIS consists of six easily obtainable clinical and laboratory variables: (1) Body temperature, (2) blood leukocyte count and number of band forms, (3) character of tracheal secretions (purulent or not) and quantity of tracheal aspirates, (4) microscopic examination (Gram-stain) and semi-quantitative culture results of the bronchial secretions, (5) ratio of arterial oxygen tension and inspiratory fraction of oxygen (PaO2 /FiO2), (6) interpretations of chest X-ray, and the use of antibiotics. According to Pugin et al., a CPIS score ≥ 6 is considered as an excellent diagnostic tool for nosocomial pneumonia.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, raw data acquired of 56 patients (18 patients per omeprazole suspension and IV pantoprazole and 20 patients per pantoprazole suspension group) was entered into SPSS (version 21.0). Comparisons of categorical data were done using the Chi-square test, and parametric numerical data were analyzed by the ANOVA test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Gastric pH was compared in all three groups utilizing mean difference of gastric pH alteration before and after treatment by Generalized Linear Model.

Results

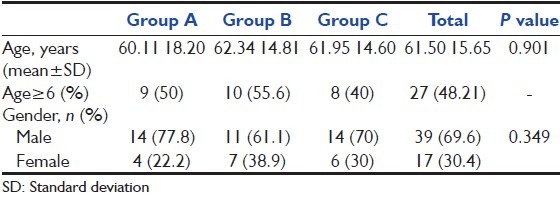

The “baseline demographics” and the “baseline clinical characteristics” of 56 participants represented in Tables 1 and 2 respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics

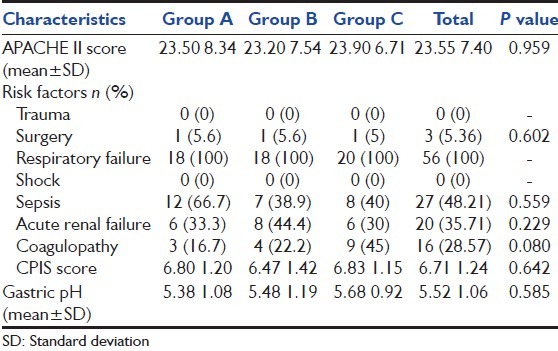

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics at baseline

There was no statistically significant difference in the baseline demographics and clinical characteristics among the groups. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) age for a total population was 61.50 (15.65) years, which 48.21% were older than 65 years. For the whole population, baseline mean (SD) APACHE II score was 23.55 (7.40). All the participants had acute respiratory failure as a risk factor whereas none of them met trauma and shock. The majority of patients (48.21%) had sepsis as a presenting risk factor. Other risk factors included acute renal failure (35.71%), coagulopathy (28.57%), and surgery (5.36%). The baseline gastric pH had no statistically difference between the treatment groups with a mean (SD) pH for the total population of 5.52 (1.06).

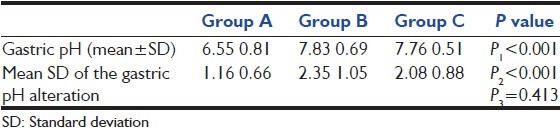

Table 3 presents the results of our primary end point-mean gastric pH after drug administration-on each trial day. Due to the important effect of the baseline pH on the gastric pH after the drug administration, we also calculated the mean of the gastric pH alteration.

Table 3.

Mean gastric pH after the drug administration

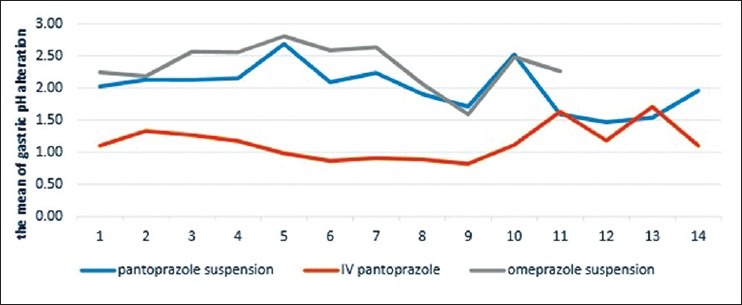

On every 14 days, the mean gastric pH alteration values were significantly higher in omeprazole and pantoprazole suspension group after prophylaxis with each of the medications compared to IV pantoprazole-treated patients (P < 0.001, all days) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Mean of pH

Average time to achieve the target pH

We considered mean of gastric pH alteration ≥ 1 as a target. Average time to get this pH for the total population was 1.24 ± 0.61 days (1.35 ± 0.79 days in Group A, 1.17 ± 0.51 days in Group B and 1.2 ± 0.52 days in Group C). In addition, 83.6% of patients achieved the target pH after the first dose administration (76.5% in pantoprazole suspension group, 88.9% in omeprazole suspension group and 85% who received pantoprazole suspension). There was no statistically significant difference between three groups.

Incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Protocol defined upper GI bleeding occurred in 3 (5.6%) patients from the total population. Two patients (11.1%) were in the IV pantoprazole-treated patients, and one of them (5.6%) was in the omeprazole suspension group. No patient in pantoprazole suspension-treated group was identified with upper GI bleeding.

Incidence of pneumonia

Sixteen (88.9%) patients from IV pantoprazole treated group, 14 (77.8%) patients from omeprazole suspension-treated group and 17 (85%) patients who had received pantoprazole suspension were diagnosed as having nosocomial pneumonia.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that extemporaneously prepared omeprazole and pantoprazole oral suspension produced higher mean gastric pH values than IV pantoprazole. There was statistically significant difference between omeprazole and pantoprazole oral suspension and IV pantoprazole (P < 0.001) [Table 3].

Phillips et al. studied a 20 ml dose of 2 mg/ml omeprazole suspension (containing 40 mg of omeprazole) initially, followed by 20 ml dose administered 6-8 h later, then 10 ml (20 mg) dose for stress-related mucosal damage in 75 patients undergoing mechanical ventilation who had at least one additional risk factor for upper GI bleeding. They observed that the omeprazole suspension increased gastric pH more than 7.1, maintained gastric pH > 5.5 and prevented clinically significant upper GI bleeding without increasing the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia.[8] These findings are completely in line with Lasky et al. study on 60 participants who assessed the effect of omeprazole suspension in preventing clinically significant upper GI bleeding and in preventing stress ulcers in mechanically ventilated trauma patients.[19]

In a randomized, double-blind trial, Conrad et al. found that immediate-release omeprazole oral suspension is more effective than a continuous infusion of cimetidine in increasing gastric pH and in preventing upper GI bleeding of critically ill patients.[17] In a smaller, un-blinded, randomized trial Levy et al. compared omeprazole with ranitidine in 67 patients who had risk factors for stress ulcer-related bleeding. Results showed significantly more clinically important upper GI bleeding in the ranitidine group than in the omeprazole group due to the inadequate pH control in the ranitidine-treated patients.

This satisfying control of gastric pH by omeprazole and pantoprazole oral suspension, without facing increased rate of pneumonia; which was previously reported by other studies,[20,21] could be due to the presence of sodium bicarbonate in the extemporaneous formulation. Although enteric-coating is dissolved by bicarbonate, the alkaline properties of omeprazole suspension appear to protect omeprazole by passing through the stomach and actually aid in the initial control of gastric pH by acting as an antacid. The sodium bicarbonate with pH of 8.4 may stimulate the activation of parietal cells. Such stimulation may improve the pharmacodynamics of the drug by synchronizing the contact time of omeprazole with parietal cells activation.[8]

We used nonsterile hospital pharmacy manufacturing service at Pharmaceutical Care Department, NRITLD in order to prepare a prescribed medication (omeprazole or pantoprazole as their commercially available dosage form) for individualized patients who are NPO. Thus, they are unable to swallow the solid forms of the drugs.

An interesting finding of the current study is the control of gastric pH after the first dose of the administered drug in the majority (83.6%) of patients. Average time to achieve mean pH alteration bigger than 1 was 1.24 ± 0.61 days for the total population. It can be concluded from the recent data that there might be no need to pH monitoring after the day 1.

The current study used an expanded definition for upper GI bleeding. Despite broadening the range of the definition application, which includes even minor self-limited bleeding and bleeding-related to a nasogastric tube trauma, only three patients (5.36%) experienced protocol-defined upper GI bleeding. Two of those who met our secondary end point of upper GI bleeding were among IV pantoprazole-treated patients, and the other one was among the omeprazole suspension group. No significant difference in preventive upper GI bleeding has been indicated between three groups.

It has been noted that raising gastric pH ≥ 4 could be a risk factor for the development of nosocomial pneumonia. Increasing intragastric pH may allow bacterial (especially Gram-negative bacilli) proliferation in the duodenum and subsequently endotracheal colonization.[21] However, the clinical trials do not seem to support this hypothesis. A double-blind multi-center study that assessed the effect of sucralfate and ranitidine in 1200 critically ill-patients revealed no significant increase in nosocomial pneumonia with ranitidine although it showed a significant decrease in upper GI bleeding with the H2RA.[22] Despite higher mean gastric pH values in omeprazole and pantoprazole suspension group in comparison with IV pantoprazole-treated patients, we found no significant difference in the rate of nosocomial pneumonia among three treatment groups. Our results are in accord with the finding: As yet, no relation between the type of acid-reducing agent and the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia has been found.

Limitations of the study

(1) Due to several inclusion criteria to meet, we were not able to expand the sample size. (2) Restricted enteral feeding protocol for critically ill patients limited us to hold the enteral feeding for more than 2 h before and 1 h after the sampling. (3) Inefficient method of gastric acid measurement (aspiration technique) used in the study put constraints on sampling, especially in patients with low gastric secretions. (4) High mortality rate of patients at ICUs that was the second important reason causes the patients to stop the trial before the day 14.

Conclusion

These findings indicate that extemporaneous preparations of omeprazole and pantoprazole oral suspension are more effective than IV pantoprazole in increasing gastric pH in critically ill-patients without no significant difference in the rate of nosocomial pneumonia between the three treatment groups.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Metz DC. Potential uses of intravenous proton pump inhibitors to control gastric acid secretion. Digestion. 2000;62:73–81. doi: 10.1159/000007798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fennerty MB. Pathophysiology of the upper gastrointestinal tract in the critically ill patient: Rationale for the therapeutic benefits of acid suppression. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S351–5. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200206001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook DJ, Griffith LE, Walter SD, Guyatt GH, Meade MO, Heyland DK, et al. The attributable mortality and length of intensive care unit stay of clinically important gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2001;5:368–75. doi: 10.1186/cc1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinberg KP. Stress-related mucosal disease in the critically ill patient: Risk factors and strategies to prevent stress-related bleeding in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S362–4. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200206001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasue N, Guth PH. Role of exogenous acid and retransfusion in hemorrhagic shock-induced gastric lesions in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:1135–43. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamada T, Sato N, Kawano S, Fusamoto H, Abe H. Gastric mucosal hemodynamics after thermal or head injury. A clinical application of reflectance spectrophotometry. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:535–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tryba M, Cook D. Current guidelines on stress ulcer prophylaxis. Drugs. 1997;54:581–96. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199754040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips JO, Metzler MH, Palmieri MT, Huckfeldt RE, Dahl NG. A prospective study of simplified omeprazole suspension for the prophylaxis of stress-related mucosal damage. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1793–800. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199611000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wurzer H, Schutze K, Bethke T, Fischer R, Luhmann R, Riesenhuber C. Efficacy and safety of pantoprazole in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease using an intravenous-oral regimen. Austrian Intravenous Pantoprazole Study Group. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:1809–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metz DC, Pratha V, Martin P, Paul J, Maton PN, Lew E, et al. Oral and intravenous dosage forms of pantoprazole are equivalent in their ability to suppress gastric acid secretion in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:626–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lew EA, Pisegna JR, Starr JA, Soffer EF, Forsmark C, Modlin IM, et al. Intravenous pantoprazole rapidly controls gastric acid hypersecretion in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:696–704. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70139-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bardhan KD. Pantoprazole: A new proton pump inhibitor in the management of upper gastrointestinal disease. Drugs Today (Barc) 1999;35:773–808. doi: 10.1358/dot.1999.35.10.561696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitton A, Wiseman L. Pantoprazole. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use in acid-related disorders. Drugs. 1996;51:460–82. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199651030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velayati AA, Mehrabi Y, Radmand G, Maboudi AA, Jamaati HR, Shahbazi A, et al. Modification of Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score through recalibration of risk prediction model in critical care patients of a respiratory disease referral center. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2013;3:40–5. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.109419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman M. Pharmacology of untiulcer medications. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 8]. Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/clinicians/content/topic.doptopickey=Ym-odubHEMPOk .

- 16.Jew RK, editor. Extemporaneous Formulations for Pediatric, Geriatric, and Special Needs Patients. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conrad SA, Gabrielli A, Margolis B, Quartin A, Hata JS, Frank WO, et al. Randomized, double-blind comparison of immediate-release omeprazole oral suspension versus intravenous cimetidine for the prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:760–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000157751.92249.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pugin J, Auckenthaler R, Mili N, Janssens JP, Lew PD, Suter PM. Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia by bacteriologic analysis of bronchoscopic and nonbronchoscopic “blind” bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:1121–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.5_Pt_1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lasky MR, Metzler MH, Phillips JO. A prospective study of omeprazole suspension to prevent clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding from stress ulcers in mechanically ventilated trauma patients. J Trauma. 1998;44:527–33. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199803000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernández C, el-Ebiary M, Gonzalez J, de la Bellacasa JP, Montón C, Torres A. Relationship between ventilator-associated pneumonia and intramucosal gastric pHi: A case-control study. J Crit Care. 1996;11:122–8. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9441(96)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li HY, He LX, Hu BJ, Wang BQ, Zhang XY, Chen XH, et al. The impact of gastric colonization on the pathogenesis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2004;43:112–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook D, Guyatt G, Marshall J, Leasa D, Fuller H, Hall R, et al. A comparison of sucralfate and ranitidine for the prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:791–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803193381203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]