Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study was to analyze the retrospective experience related to the indication, complication and outcome of Therapeutic Plasma Exchange (TPE) in Myasthenia gravis (MG). It is a well known autoimmune disease characterized by antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor (anti-ACHR) on the post synaptic surface of the motor end plate. Plasma exchange is the therapeutic modality well established in MG with a positive recommendation based on strong consensus of class III evidence.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 35 patients of MG were submitted to a total of 41 cycles and 171 session of TPE. It was performed using a single volume plasma exchange with intermittent cell separator (Hemonetics) by Femoral or central line access and schedule preferably on alternate day interval. Immediate outcome was assessed shortly after each session and overall outcome at discharge.

Results:

Total of 110 patients of MG who were admitted to our hospital during the study period of two years. 35 (31.8%) patients had TPE performed with mean age of 32 years (M:F = 2:1). The mean number of TPE session was 4.2 (SD±1.2), volume exchange was 2215 ml (SD±435); overall incidence of adverse reaction was 21.7%. All patients had immediate benefits of each TPE cycle. Good acceptance of procedure was observed in 78.3% of patients.

Conclusion:

TPE may be considered as one of the treatment options especially in developing countries like ours as it is relatively less costly but as effective for myasthenic crisis as other modalities.

Keywords: Adverse reaction, auto antibodies, myasthenia gravis, therapeutic plasma exchange

Introduction

Therapeutic apheresis encompasses a variety of blood processing techniques, which improve the outcome of susceptible clinical disorders. These techniques include, in part, therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE), therapeutic cytoreduction, in line cellular immunomodulation and plasma treatment. Some of these applications are the primary therapy for certain disease processes, and many others are considered to be secondary or adjunctive therapy, but both categories of apheresis treatments are considered to be effective and beneficial.[1]

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a well-known autoimmune disease characterized by antibodies against postsynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and fluctuating weakness, sometimes life-threatening. MG has annual incidence of approximately 30 new cases per million, approximately 15–20% of these patients will go into myasthenia gravis crisis (MGC) and 3–8% of all patients who go into MGC will die from this condition.[2] TPE is a therapeutic modality well established in MG with a positive recommendation based on strong consensus of class III evidence and in the category I of American society for apheresis.[3,4,5] The two most common indications for acute exchange are myasthenic crisis and myasthenia exacerbation.[4] There are no adequate randomized control trial, but many cases report short-term benefit from plasma exchange in MG especially MGC.[6]

Therapeutic plasma exchange is an extracorporeal blood purification technique in which the plasma is separated from the blood, discarded in total, and replaced with a substitution fluid such as an albumin or with plasma collected from healthy donors. This is generally performed to remove high-molecular-weight substances such as pathogenic autoantibodies, immune complexes, cryoglobulins and toxins that have accumulated in the plasma.[7] Its efficiency in MG is due to removal of proteins of autoimmune biological activity, mainly antibodies to acetylcholine receptor, leading to short-term improvement of neuromuscular junction transmission, muscular strength and motor performance.[8] Rapidly reducing the autoantibodies may sometimes lead to a rebound overproduction of same antibodies. This rebound production of antibodies is thought to make the replicating pathogenic cells more vulnerable to cytotoxic drugs, for this reason, it is often performed to enhance the effectiveness of cytotoxic drugs. Usually, TPE is combined with immunosuppressive treatments, such as intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), prednisone and azathioprine, to avoid rebound effect and to maintain the improvement.[9] Both IVIG and TPE have been found to be effective disease stabilizing therapies for patients with MGC.[10] Until date, neither IVIG nor TPE has established clear clinical dominance over the other for the treatment of MGC. As the societal cost of health care has increased, it is imperative to both optimize patient care and identify areas where costs can be reduced. Although the cost should never to be the primary reason for selecting a therapy, it is reasonable to consider this aspect in select cases where one beneficial therapy is not clearly superior to another.[11,12] In comparison to IVIG, plasma exchange is considered equally effective and is comparatively a cheaper mode of immunomodulatory treatment in for myasthenia crisis.

We retrospectively analyzed experience related to the indications, complications and outcome of TPE in the treatment of MG patients, and several aspects of the procedure itself were also reviewed.

Materials and Methods

Study design

Patients of MG and MGC admitted in the Neurology Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and on mechanical ventilation during the period January 2011 to December 2013 (3 years study) were included in the study TPE (average cost is 12,000/cycle) was initiated and monitored by the Department of Immunohematology and blood transfusion in a tertiary care hospital.

Patient study

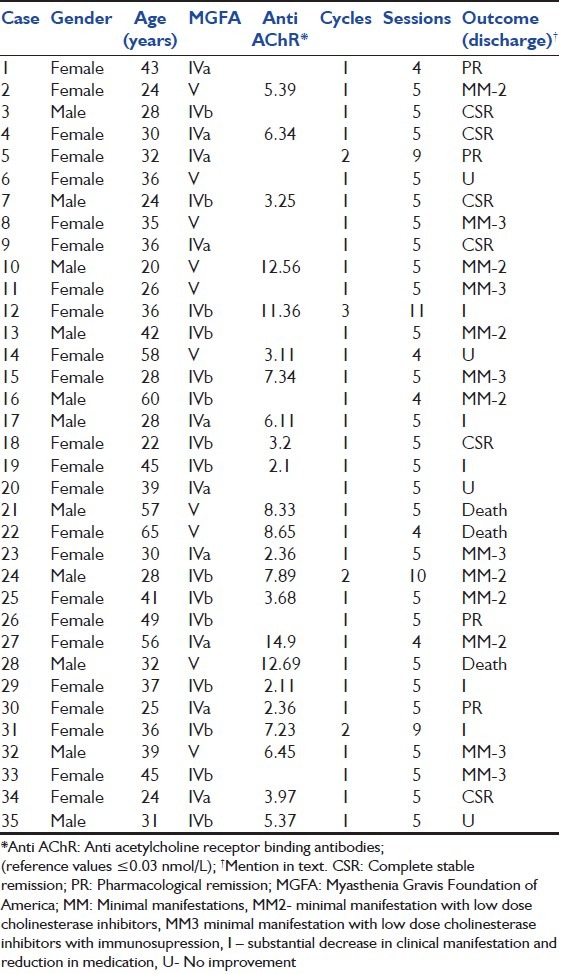

From January 2011 to December 2013, there were total 110 patients of MG who were admitted to our hospital. 35 (31.8%) of them received TPE. We reviewed TPE protocols of these consecutive series of 35 patients of MG in ICU. They were submitted to a total of 41 cycles and 171 sessions of TPE during this period. Clinical diagnosis of MG was complemented by laboratory exams, such as repetitive nerve stimulation tests, antiacetylcholine receptor (Anti AChR) antibodies and neostigmine test. Patients were classified according to the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA) scales expressing the clinical deficit before TPE. Gender, age-onset of MG, level of serum Anti AChR binding antibodies, and the disease status at discharge were analyzed as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristic detail of patients, procedure and outcome

Patient's blood counts, electrolytes, serum proteins, coagulation profile, and vitals were checked, and appropriate steps were taken to correct the deranged parameters. The consent for the procedure was taken from the patient/patients relatives before the procedure. TPE was performed using a single volume plasma exchange with intermittent cell separator (Hemonetics MCS plus, kit 980/790) machines by femoral or central line access using 12 French double lumen dialysis catheter. It was scheduled preferably on alternate-day intervals for 8–10 days. Anticoagulation with citrate (ACD) was systematically used. Replacement of plasma removed during the session was done with isotonic sterile saline, to makeup one-half of the volume and with 4% purified human albumin and fresh frozen plasma to complete it. A careful monitoring of hemodynamic parameters was done and complications during or following TPE were rapidly recognized and reverted by rationale interventions of medical staff that assisted the procedure. Indications for TPE, number of cycles and sessions, duration of each session, volume of plasma exchanged and patient tolerance to the procedure were systematically recorded. Calcium replacement with 10 ml of 10% calcium gluconate was infused over 15 min approximately halfway through the procedure to avoid citrate toxicity. Hemogram, serum electrolytes, total protein, and albumin were monitored daily. Immediate outcome was assessed shortly after each session, and overall outcome was assessed at the time of discharge. The amount of plasma to be exchanged must be determined in relation to the estimated plasma volume (EPV). A simple means of estimating, the EPV can be calculated from the patient's weight and hematocrit using the formula. EPV = (0.65 × wt [kg]) × (1 − Hcv).[13]

Results

A total of 35 (31.8%) patients of MG or MGC, out of which 23 who were on mechanical ventilation received plasma exchange during the period of 2 years from January 2011 to December 2013. A total of 41 cycles and 175 sessions of TPE were done. It included 24 females and 11 male with age group ranging from 18 to 62 years. The mean age of onset was 32 years, using MGFA clinical classification, cases were classified as class IV a (12 cases), class IV b (15 cases) and class V (8 cases). All patients responded transiently favorable to each cycle of TPE, but none had been exclusively under this therapy. Prednisone and or azathioprine were the most frequent immunosuppressors used. TPE was indicated due to myasthenic crisis in 23 (65.7%) with severe motor dysfunction, especially related to bulbar palsy and rest 12 (34.3%) were offered TPE as there was progressive exacerbation of myasthenic symptoms in spite of optimal treatment. The mean number of TPE sessions was 4.2 (standard deviation [SD] ±1.2). The mean volume of plasma exchanged was 2215 ml (SD ± 435) and mean time duration of each session was 207 min (SD ± 25). Side effects were mild such as citrate toxicity in 12 (6.8%), hypotension in 2 (1.14%), catheter-related problems in 8 (4.6%) and anaphylactoid reactions to FFP in 16 (9.14%) procedures. No infection was observed, and no death occurred in consequence of TPE. Good TPE acceptance occurred in 74.2% of cases.

Each sessions of TPE resulted in immediate improvement of clinical status in every patient. However, at discharge clinical status was recorded as complete stable remission in six patients; pharmacological remission in four, minimal manifestations (MM), taking low-dose of cholinesterase inhibitors (MM2) in seven, MM, with low-dose cholinesterase inhibitors and some immunosuppressor (MM3) in six; substantial decrease in clinical manifestations and reduction in medication (I) in five; no substantial change in pretreatment clinical manifestations (U) in four. Death was registered in three patients, but it was not directly related to TPE.

Discussion

Myasthenia gravis was the second most common indication for TPE in 1997 and was first described as a form of treatment for MG in 1976 by Pinching and Peter. They performed plasma exchange in 3 patients and found partial improvement in muscle weakness and fatigue, suggesting that a humoral factor in the plasma was causing the disorder of neuromuscular transmission.[14] A close correlation with clinical, functional improvement and a reduction in acetylcholine receptor antibody levels was found. There were a few randomized control trials in MG; a trial of 87 patients showed the same efficacy after 2 weeks of TPE for the treatment of MG exacerbation as compared to IVIG.[15] Gajdos et al. in their meta-analysis on TPE in MG concluded that TPE provides short term benefits in patients with MG especially myasthenic crisis.[6] A multicenter study from Taiwan showed that 34.9% of TPE was indicated for MG patient.[16]

In our study, the proportion female:male ratio was 2:1. TPE was indicated due to myasthenic crisis in 23 (65.7%) patients and progressive worsening despite treatment in 12 (34.3%). Similarly Carandina-Maffeis et al.[17] performed plasma exchange in 7 (26.9%) patients with myasthenic crisis. Werneck et al.[18] used plasma exchange as a specific modality of treatment in 24 (16.6%) patients with worsening myasthenic symptoms.

TPE was indicated in patients having severe motor deficit, especially bulbar dysfunction or due to exacerbation of deficit induced by immunosuppressive as it is a drug of first choice in the therapy of MG. TPE was repeated in four cases because other therapies failed to achieve the necessary sustained motor performance for daily life activities. Case no 12 had 3 cycles, in a monthly schedule of four consecutive alternate day sessions and case no 5, 24 and 31 had 2 cycles, in a two monthly schedule of five consecutive alternate day sessions of TPE respectively. It was observed that chronic TPE is an effective therapy in case of generalized MG refractory to other treatments. Rodnitzky and Bosch described two cases of intermittent plasma exchange (PE) therapy prescribed up to 5 years without significant side-effects.[19]

The perception that TPE is a benign procedure has undoubtedly contributed to its widespread use for unproven indications. The overall incidence of adverse reaction reported in the literature range from 1.6% to 25% with severe reaction occurring in 0.5-3.1%,[20] but in our study overall incidence of adverse reactions was 21.7%. The most common frequent complications were related to either vascular access or the composition of replacement fluids. Hematomas, infections, catheter blockage and pneumothorax are the most frequent complication of vascular access complicating 0.02–4%, citrate toxicity approximately 1.5–9%, hypotension or vasovagal reaction occurs in roughly 0.4–4% of procedures due to preexisting hemodynamic instability[21] and anaphylactoid reactions to FFP are common and have been reported to occur with an incidence of up to 21%.[22] In our study, we encountered catheter blockage in eight procedures (4.6%) but culture of catheter tips were all negative, citrate toxicity occurred in twelve (6.8%), hypotension in two (1.14%), was reversed by fluid replacement and anaphylactic reaction occurred in 16 (9.14%) and was managed with intravenous hydrocortisone and diphenhydramine. Korach et al.[23] observed that Complication of anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution were responsible for 3% of side effects in all procedures, like perioral tingling, trembling, dizziness and hypotension. Seggia et al.[24] also presented a list of side effects in their patients who were all easily managed such as 10.4% of paresthesias, 2% of hypotension and 10.4% of allergic reactions. Three patients were on chronic ventilator-dependent state with diaphragmatic paralysis and had prolonged hospitalization, evolving to death from sepsis that occurred 3 and 4 months after TPE, but there no direct relatiionship could be established. Kiprov et al.[21] found a mortality rate of 0.006% from two large mobile apheresis services and mortality rate was 0.2% in a survey of 7 years in Mexico.[25,26]

Conclusion

We found TPE improves short-term outcome in patients with myasthenic crisis or those who experience exacerbations in spite of treatment with steroids and oral immunosuppressives. Improvements in apheresis machines have made it a very safe treatment as well and clinical effect can be apparent within a day to a week.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Gilcher RO, Smith JW. Apheresis: Principles and technology of hemapheresis. In: Simon TI, Synder EL, Solheim C, Stowell P, Strauss G, Petrides M, editors. Rossi's Principles of Transfusion Medicine. USA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. pp. 617–28. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGrogan A, Sneddon S, de Vries CS. The incidence of myasthenia gravis: A systematic literature review. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;34:171–83. doi: 10.1159/000279334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strauss RG, Ciavarella D, Gilcher RO, Kasprisin DO, Kiprov DD, Klein HG, et al. An overview of current management. J Clin Apher. 1993;8:189–94. doi: 10.1002/jca.2920080402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assessment of plasmapheresis. Report of the therapeutics and technology assessment subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 1996;47:840–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JW, Weinstein R, Hillyer KL. AABB Hemapheresis Committee. American Society for Apheresis. Therapeutic apheresis: A summary of current indication categories endorsed by the AABB and the American Society for Apheresis. Transfusion. 2003;43:820–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gajdos P, Chevret S, Toyka K. Plasma exchange for myasthenia gravis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002:CD002275. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lockwood CM, Worlledge S, Nicholas A, Cotton C, Peters DK. Reversal of impaired splenic function in patients with nephritis or vasculitis (or both) by plasma exchange. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:524–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197903083001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newsom-Davis J, Wilson SG, Vincent A, Ward CD. Long-term effects of repeated plasma exchange in myasthenia gravis. Lancet. 1979;1:464–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90823-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heatwole C, Johnson N, Holloway R, Noyes K. Plasma exchange versus intravenous immunoglobulin for myasthenia gravis crisis: An acute hospital cost comparison study. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2011;13:85–94. doi: 10.1097/CND.0b013e31822c34dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zinman L, Ng E, Bril V. IV immunoglobulin in patients with myasthenia gravis: A randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;68:837–41. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256698.69121.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murthy JM, Meena AK, Chowdary GV, Naryanan JT. Myasthenic crisis: Clinical features, complications and mortality. Neurol India. 2005;53:37–40. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.15050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gajdos P, Chevret S, Clair B, Tranchant C, Chastang C. Clinical trial of plasma exchange and high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin in myasthenia gravis. Myasthenia Gravis Clinical Study Group. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:789–96. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplan AA. A simple and accurate method for prescribing plasma exchange. ASAIO Trans. 1990;36:M597–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinching AJ, Peters DK. Remission of myasthenia gravis following plasma-exchange. Lancet. 1976;2:1373–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)91917-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gajdos P, Chevret S, Toyka KV. Intravenous immunoglobulin for myasthenia gravis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD002277. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002277.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeh JH, Chiu HC. Therapeutic Apheresis Registry Group in Taiwan. Therapeutic apheresis in Taiwan. Ther Apher. 2001;5:513–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carandina-Maffeis R, Nucci A, Marques JF, Jr, Roveri EG, Pfeilsticker BH, Garibaldi SG, et al. Plasmapheresis in the treatment of myasthenia gravis: Retrospective study of 26 patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2004;62:391–5. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2004000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Werneck LC, Scola RH, Germiniani FM, Comerlato EA, Cunha FM. Myasthenic crisis: Report of 24 cases. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2002;60:519–26. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2002000400001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodnitzky RL, Bosch EP. Chronic long-interval plasma exchange in myasthenia gravis. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:715–7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1984.04050180037013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madore F. Plasmapheresis. Technical aspects and indications. Crit Care Clin. 2002;18:375–92. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(01)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiprov DD, Golden P, Rohe R, Smith S, Hofmann J, Hunnicutt J. Adverse reactions associated with mobile therapeutic apheresis: Analysis of 17,940 procedures. J Clin Apher. 2001;16:130–3. doi: 10.1002/jca.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan AA. Therapeutic plasma exchange: A technical and operational review. J Clin Apher. 2013;28:3–10. doi: 10.1002/jca.21257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korach JM, Petitpas D, Paris B, Bourgeade F, Passerat V, Berger P, et al. Plasma exchange in France: Epidemiology 2001. Transfus Apher Sci. 2003;29:153–7. doi: 10.1016/S1473-0502(03)00120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seggia JC, Abreu P, Takatani M. Plasmapheresis as preparatory method for thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1995;53:411–5. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1995000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazo-Langner A, Espinosa-Poblano I, Tirado-Cárdenas N, Ramírez-Arvizu P, López-Salmorán J, Peñaloza-Ramírez P, et al. Therapeutic plasma exchange in Mexico: Experience from a single institution. Am J Hematol. 2002;70:16–21. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz J, Winters JL, Padmanabhan A, Balogun RA, Delaney M, Linenberger ML, et al. Guidelines on the use of therapeutic apheresis in clinical practice-evidence-based approach from the Writing Committee of the American Society for Apheresis: The sixth special issue. J Clin Apher. 2013;28:145–284. doi: 10.1002/jca.21276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]