Abstract

Several studies have demonstrated that human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells can promote neural regeneration following brain injury. However, the therapeutic effects of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in guiding peripheral nerve regeneration remain poorly understood. This study was designed to investigate the effects of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells on neural regeneration using a rat sciatic nerve crush injury model. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells (1 × 106) or a PBS control were injected into the crush-injured segment of the sciatic nerve. Four weeks after cell injection, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and tyrosine kinase receptor B mRNA expression at the lesion site was increased in comparison to control. Furthermore, sciatic function index, Fluoro Gold-labeled neuron counts and axon density were also significantly increased when compared with control. Our results indicate that human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote the functional recovery of crush-injured sciatic nerves.

Keywords: human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells, sciatic nerve, crush injury, Fluoro Gold, stem cells, peripheral nerve regeneration, regeneration, neural regeneration

Research Highlights

-

(1)

Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells transplanted into sciatic nerve lesion sites following crush injury, migrated toward surrounding areas and promoted functional recovery of the sciatic nerve and axonal regeneration.

-

(2)

After transplantation of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells into sciatic nerve lesion sites, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and tyrosine kinase receptor B mRNA expression increased in the sciatic nerve and dorsal root ganglions compared with control.

Abbreviations

BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; TrkB, tyrosine kinase receptor B; SFI, sciatic function index; DRG, dorsal root ganglion

INTRODUCTION

In clinical dentistry, peripheral nerves, such as the lingual, inferior alveolar or facial nerve, are often damaged by tumor, surgery or trauma. Injured peripheral nerves may gradually regenerate without treatment. However, complete regeneration takes a long time and function rarely returns to the pre-injury level because of endogenous and exogenous factors in the nervous system[1].

Clinical approaches to promote functional recovery in peripheral nervous injury include cell therapy[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10], neuromodulation (e.g., electrical stimulation)[11,12] and application of neurotrophic factors[13]. In peripheral axonal regeneration, neural cells and neural supporting cells, such as Schwann cells, may have positive effects[2,4,5]. In our previous cellular therapy study, Schwann cells promoted axonal regeneration and remyelination in adult rats[3]. However, collecting and expanding a therapeutically viable number of cells for Schwann cell therapy is technically complex, time-consuming and can result in donor site morbidity. The use of allogeneic Schwann cells could overcome these problems, however these cells could evoke an unwanted immune response[5].

Mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, skin, adipose tissue, or dental pulp, have been used as an alternative to Schwann cells to promote peripheral nerve regeneration[6,7,8,9,10]. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult tissues are often collected by invasive procedures and their potential for proliferation and differentiation is reported to decrease with age[14,15].

Umbilical cord blood is reported to contain mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells and a large number of endothelial cell precursors, as well as many immature hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells[16,17]. Umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells have been successfully isolated by non-invasive procedures and readily expanded ex vivo to a concentration sufficient for cell replacement therapy. These cells express mesenchymal stem cell markers in a similar profile to those obtained from bone marrow, and differentiate into various cell types[15,18,19,20]. Umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells offer a number of unique advantages, including: a higher proliferative potential and longer lifespan than stem cells isolated from bone marrow and adipose tissue[15,16]; lower risk of acute or chronic graft versus host disease and latent virus transmission due to fetal origin; and anti-inflammatory effects[21,22,23,24]. In addition, undifferentiated human umbilical cord blood- mesenchymal stem cells express several neural phenotypes, including nerve growth factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), p75 neurotrophin receptor, neurotrophin-3, neurotrophin-5, neurofilament and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor[25]. With these properties, the therapeutic effects of umbilical cord blood-derived cells or stem cells have been noted in various animal models of brain injury and neurological disorders[22,26,27,28,29,30]. However, the therapeutic potential of human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells as a regenerative medicine for neurological diseases and injury in the peripheral nervous system is not well documented. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cell injection on neural regeneration following crush injury in rats.

RESULTS

Quantitative analysis of animals

A total of 36 Sprague-Dawley rats were included in the study and final analysis. Rats were divided into two groups (n = 18 each): Group 1: human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells injection (experimental); Group 2: PBS injection (control). Cells or PBS were injected into the crush-injury site of the sciatic nerve in the experimental and control groups respectively.

Survival of transplanted cells

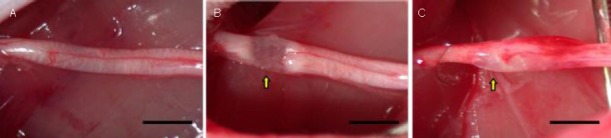

The sciatic nerve crush injury model showed definite discontinuity of axons with preservation of the epineurium compared with uninjured normal sciatic nerves. Human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells were successfully injected into the crush-injury site (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A rat model of sciatic nerve crush injury.

(A) The normal sciatic nerve; (B) crush-injured sciatic nerve, nerve fibers were discontinuous with preservation of the epineurium; and (C) crush injured sciatic nerve after human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation.

Arrows indicate the lesion. Bars: 5 mm.

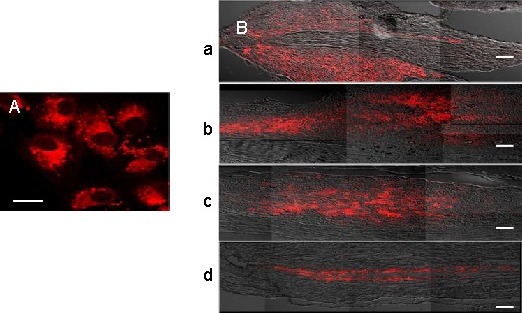

Human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells were labeled with PKH26 before injection and visualized 2 hours after seeding on a glass slide (Figure 2A). Transplanted PKH26-labeled human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells were observed in the lesion site, indicating that cells migrated from the lesion periphery to the nerve center from 2 weeks postoperation and with localization along the axon by the end of week 4 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Confocal photomicrographs of PKH26-labeled (red fluorescence) human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUCB-MSCs) before and after transplantation.

(A) PKH26-labeled hUCB-MSCs before transplantation, captured 2 hours after seeding on a glass slide. Bar: 20 μm.

(B) PKH26-labeled hUCB-MSCs in the lesion site at 1 week (a), 2 weeks (b), 3 weeks (c), and 4 weeks after transplantation (d). Bars: 200 μm.

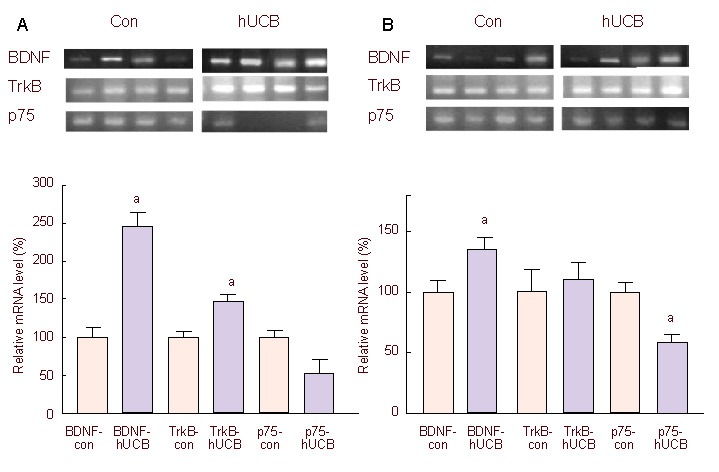

Expression of BDNF, tyrosine kinase receptor B (TrkB) and p75 mRNA

Five days after injection of human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells or PBS, BDNF, TrkB and p75 mRNA expression, in the sciatic nerve segments and L4-6 dorsal root ganglions (DRGs), were analyzed by RT-PCR. In the human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells group, BDNF and TrkB mRNA expression were significantly higher than that in the control group, increased by 2.48 and 1.43 times respectively (Figure 3A). Conversely, p75 mRNA expression appeared to decrease, but no significant difference was recorded. In DRGs, BDNF mRNA expression increased, while p75 mRNA expression decreased significantly compared with the control group (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Relative mRNA expression of BDNF, TrkB and p75 in the sciatic nerve (A) and L4-6 DRGs (B), 5 days after injection of hUCB-MSCs (hUCB-MSCs group: hUCB) or PBS (control group: con).

All mRNA was normalized to GAPDH. mRNA expression levels of BDNF, TrkB and p75 in the hUCB-MSCs group were relative to that of the control group.

aP < 0.05, vs. control group. Statistical significance was tested by analysis of variance. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; n = 6.

hUCB-MSCs: Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells; TrkB: tyrosine kinase receptor B; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor.

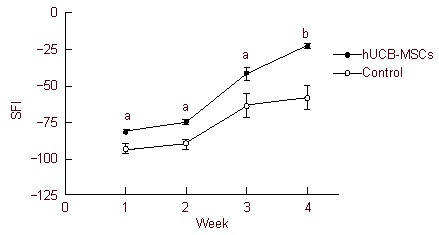

Neural functional regeneration: gait analysis with sciatic function index (SFI)

The SFI was compared between groups to assess functional recovery of the injured sciatic nerve. The SFI of both groups gradually increased by 3 weeks and dramatically improved at 4 weeks. Although the SFI of the control group increased, rats continued to walk with a rolling and unsteady gait over the follow-up period. In contrast, rats in the human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells group walked with a steady gait similar to pre-injury level at 4 weeks. At all time points, the SFI of human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells group was significantly higher than that of the control group (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

SFI value in rats with sciatic nerve injury.

The SFI value of both groups was increased, however, SFI in the hUCB-MSCs group was significantly higher than the control group at all time points, indicating functional recovery level was increased by hUCB-MSCs transplantation.

aP < 0.005, bP < 0.001, vs. control group. Statistical significance was tested by analysis of variance. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 6–11. SFI: Sciatic function index; hUCB-MSCs: human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells.

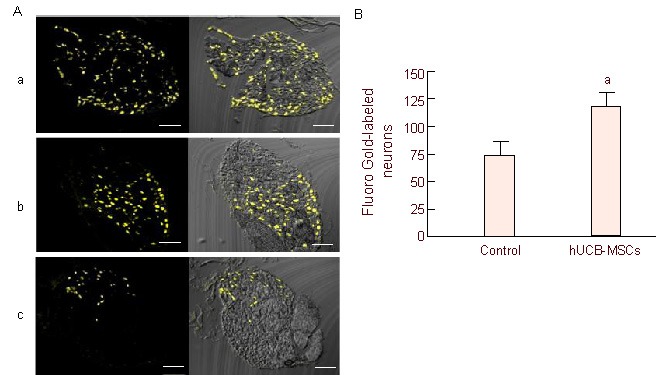

Retrograde axonal transport: retrograde labeling

Fluoro Gold-labeled neuron counts were obtained from the cellular profile (three equatorial sections per DRG). In the human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells group, the count was 118.96 ± 12.13, which was significantly higher than that of the control group at 73.19 ± 12.84 (Figure 5). For reference, the count in uninjured rats was 188.75.

Figure 5.

Fluoro Gold-labeled neuron counts in the DRG.

(A) Retrograde tracing with Fluoro Gold. Fluoro Gold-labeled neurons appear as gold/yellow fluorescence. Normal DRG (a), hUCB-MSCs (b) and control (c) groups. Bars: 200 μm.

(B) Comparison of Fluoro Gold-labeled neuron mean counts. Mean counts were obtained from one representative equatorial profile per DRG, not indicating total number of DRG neurons. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 5. aP < 0.05, vs. control group. Statistical significance was tested by the Mann-Whitney test. DRG: Dorsal root ganglion; hUCB-MSCs: human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells.

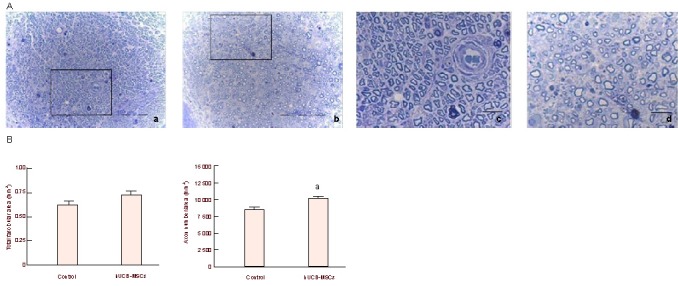

Axonal regeneration: histomorphometric analysis

Axonal regeneration is a critical indicator of peripheral nerve regeneration. The total ascicular area was similar in both groups. Axon density in the human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells group was significantly higher than that in the control group (P < 0.005).

We found myelinated axons were distributed densely in the human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells group, while the control group included more degenerated axons. This suggests that axonal regeneration in the human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells group was enhanced compared with the control group (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Axonal regeneration after human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hUCB-MSCs) transplantation.

(A) Histological photographs of axons in hUCB-MSCs (a) and control (b) groups 4 weeks postoperatively; (c) and (d) are enlarged images of (a) and (b) respectively. Axons were distributed more densely in the hUCB-MSCs group. Bar is 100 μm in (a–b) and 20 μm in (c–d).

(B) Graphs of total fascicular area and axon density. aP < 0.005, vs. control group. Statistical significance was tested by analysis of variance. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 6.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies support that umbilical cord blood-derived cells modulate the immune response due to low immunogenicity and survive in xenogenic hosts with positive effects in absence of immunosuppressive drugs[22,26,30,31]. In addition, umbilical cord blood-derived stem cells are reported to suppress xenogeneic T-cell proliferation in vitro[21,24] and decrease expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain of a pre-clinical stroke model[23].

These studies emphasize that human umbilical cord blood-derived stem cells most likely inhibit the apoptotic cascade and modulate the immune/inflammatory response to injury due to their unique properties[21,22,23,24].

Jablonska et al[31] reported that inflammatory cells appeared within 24 hours after transplantation of human umbilical cord blood-derived neural-like stem cells into adult and newborn rats and an acute local inflammatory reaction persisted for a few days in adult and even newborn rats. This suggests that the inflammatory reaction might have occurred due to surgical injury or other unclear reasons without regard to the xenotransplantation. For this reason, immunosuppressants were not used in this study. PKH26-labeled human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells appeared at the lesion site where they might participate in the construction of the neural network, however, their numbers gradually decreased over the follow-up period. We determined differentiation of human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells by colocalization of PKH26 with several neuronal or non-neuronal phenotypes in transplanted cells in the lesion site. Several studies related to human cell survival in rats, have demonstrated that transplanted human cells in newborn rats survive no more than 5 weeks and their survival was not enhanced after immunosuppressant (such as cyclosporine A) treatment[31]. Survival of human cells implanted in animals is therefore not guaranteed. This may be due to reasons beyond immune-mediated cell destruction, for example, mismatches in the requirements for and availability of trophic support, leading to apoptosis of stem cells and their progeny[31,32]. During regeneration, neurotrophins and their receptors are reported to be essential at the lesion site and differentially expressed in tissue-specific and time-dependent patterns. In motor axon regeneration after injury, BDNF, TrkB and p75 play distinct modulatory roles, facilitating development of a regenerative preferential environment[33,34,35,36,37]. BDNF promotes motor function recovery and motor neuron survival after injury and participates in neuronal activities through the TrkB receptor. Regarding receptors, TrkB and p75 generate distinct signals during peripheral nerve regeneration. TrkB is an essential factor for neuron survival and reinnervation after injury, whereas p75 receptor is important during development, but negatively regulates neurite outgrowth and axonal sprouting in motor axonal regeneration[33,34].

After sciatic nerve crush injury, expression of BDNF mRNA increased, peaked at day 3 and remained for 1 week. Meanwhile, p75 mRNA levels transiently decreased in the DRGs during the first several days but returned to normal within 1 week. TrkB mRNA was expressed in the normal sciatic nerve and the level was not altered following sciatic nerve crush injury[37]. Therefore, 4 weeks after transplantation, mRNA expression of BDNF, TrkB and p75 can presumably return to normal levels. Sciatic nerve crush injury increases retrograde transport along the axon from target tissue to the cell body and converts a signal transduction mode to a regenerative mode. Therefore, retrograde axonal transport of neurotrophins is essential for damaged nerves or neurons to survive and regenerate. Many neuronal tracers (i.e., Fast Blue, Fluoro Ruby, Fluoro Gold and Diamidino Yellow) for retrograde labeling analysis have been used and Fluoro Gold is known to be effectively transported and used for short-term study among them[38,39,40]. Retrograde neuronal labeling can be achieved by applying tracers to the cut ends of nerves or injecting tracers into nerves. Injection of tracers may be less effective than neuronal labeling and may produce unacceptable variation in numbers of neurons labeled[38,40]. Therefore, the method of tracer application to the cut ends of nerves was used in our study.

The first time point for gait analysis with SFI in this study was 1 week after injection of human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells or PBS following crush injury, not from preoperative SFI. If foot print was recorded and SFI analyzed at pre-injury level, SFI would have been identical in both groups. Moreover, in our previous study, the SFI of crush injury group alone was –53.17 ± 2.4 at 3 weeks postoperatively[12]. The value is lower than the SFI for the human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells group (–41.38 ± 4.54) and control group (–63.80 ± 7.92) in this study at the same time point. This result shows a definite improvement in gait function by transplantation of human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells into the crush-injury site.

To obtain Fluoro Gold-labeled neuron counts from three equatorial sections per DRG, we obtained the pattern of retrograde axonal transport by Fluoro Gold using non-quantitative analysis. To obtain unbiased and quantitative Fluoro Gold-labeled neuron counts, stereological analysis is recommended, but this is difficult to analyze. Coggeshall[41] reported that the dissector method can be considered as an alternative. Previous studies have reported rat sciatic nerve is composed predominantly of elements originating at levels L4-6. However, similar reports have shown that L4 and L5 are the major components, while the contribution of L6 nerves to the sciatic nerve is low[42,43]. In future studies using the sciatic nerve model, L4 and L5, rather than L6, should be harvested.

In the uninjured normal rat, axon density is approximately 14 109.002 ± 312.782/mm2 (data not shown in this study). Despite improvements in nerve repair, axonal regeneration of the human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells group did not reach normal level. Histomorphometric analysis was performed with regard to the total sciatic nerve fascicular area and axonal number. However, myelin thickness before and after human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells transplantation following sciatic nerve injury might provide a better understanding of the potentiality of human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells transplantation.

In conclusion, transplantation of human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells into the rat sciatic nerve following crush injury promoted functional recovery of the injured sciatic nerve and axonal regeneration compared with the control group. Our results show the potential of human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells therapy in peripheral nerve regeneration. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanism by which human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells transplantation promotes peripheral nerve regeneration remains poorly understood.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

A randomized, controlled, animal experiment.

Time and setting

This study was performed at the Department of Craniofacial Structure & Functional Biology, School of Dentistry, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea from January 2009 to May 2010.

Materials

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Seong Nam, Gyeong gido, Korea) aged 6 weeks, weighing 250–300 g, were included in this study. All rats were raised in accordance with the guidelines of the Laboratory Animal Resources at Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea.

Keratinocyte-serum-free medium, fetal bovine serum, human recombinant epidermal growth factor, bovine pituitary extract and PBS were obtained from Gibco (New York, NY, USA). N-acetyl-L-cysteine, hydrocortisone, insulin, ascorbic acid, PKH26 dye kit (red fluorescence), agarose, glutaraldehyde, toluidine blue and osmium tetroxide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). TRIzol® LS Reagent was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA) and Total RNA Extraction Kit was purchased from iNtRON Biotechnology Inc., (Beverly, MA, USA). Fluoro Gold was purchased from Fluorochrome Inc. (Denver, CO, USA).

Methods

Cell preparation for transplantation

hUCB-mesenchymal stem cells were isolated and culture-expanded according to the published protocol[18], kindly donated by Prof. Kang's team (Department of Stem Cells and Tumor Biology, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea). UCB samples were obtained from the umbilical vein immediately after delivery, with the mother's informed consent. This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University and Seoul National University Boramae Hospital. The UCB samples were mixed with Hetasep solution (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) at a ratio of 5:1 and incubated at room temperature to deplete erythrocytes.

The supernatant was carefully collected and mononuclear cells were obtained by Ficoll density-gradient centrifugation at 2 500 r/min for 20 minutes. Cells were washed once or twice in PBS and seeded at a density of 2 × 105 to 2 × 106 cells/cm2 under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. After 3 days, non-adherent cells were removed and media were changed. Adherent cells formed colonies about 10–14 days after seeding and then rapidly grew with a spindle-shaped morphology. The cells possessed the capacity to differentiate into at least three lineages, including adipocytes, chondrocytes and osteocytes. A survey of cell surface antigens on these cells revealed the presence of several antigens characteristic of mesenchymal stem cells. These mononuclear cells were therefore named human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells[18,44]. Prof. Kang's team previously demonstrated that culture-expanded human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells retain their multipotency and express OCT4A, which is known to be an essential factor for stemness[44] and have shown therapeutic benefits on Buerger's disease and ischemic limb disease pre-clinically[26].

Human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells were maintained and expanded in keratinocyte-serum-free medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 5 ng/mL human recombinant epidermal growth factor, 50 μg/mL bovine pituitary extract, 2 mM N-acetyl-L-cystein, 74 ng/mL hydrocortisone, 5 μg/mL insulin, and 0.2 mM L-ascorbic acid, and were incubated at 37°C in 95 % humidity and 5% CO2. Culture medium was replaced every 3 days. Passage 5 human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells were used for transplantation into rats. Transplanted cells for each rat were taken from individual, non-pooled donors.

To track the transplanted human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells, cells were labeled with PKH26 fluorescent cell linker dye according to the manufacturer's protocol and then injected into rats in the human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells group (n = 4). At 1, 2, 3 and 4 weeks after injection of PKH26-labeled human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells, the nerve was harvested, sectioned longitudinally and red fluorescence was observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus, FV-300, Japan). Crush-injury sites were marked with a stay suture using 9‒0 nylon (Ethicon, Livingston, UK) to identify the injury site at a later time.

Animal surgery procedure

Rats were intraperitoneally anesthetized with a cocktail of pentobarbital (45 mg/kg) and chloral hydrate (3 mL/kg). The right sciatic nerve was exposed and crushed with a 3 mm-wide hemostat at 5 mm distal to the sciatic notch for 1 minute. Immediately after creation of the 3 mm-wide crush injury, human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells group rats were immediately injected at a density of 1 × 106 cells/15 μL of PBS into the lesion using a 30-gauge needle attached to a Hamilton syringe. Control group rats received 15 μL of PBS without cells. The application dose of human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells in this study was based on the dose-dependence of stem cell-mediated functional recovery in a stroke rat model. These findings suggested that behavioral performance significantly recovered at 4 weeks when 106 or more human umbilical cord blood-derived cells were delivered[29].

Effect of cell transplantation on BDNF, TrkB and p75 mRNA expression

At 5 days post-surgery, rats in both groups (n = 6 each) were intraperitoneally anesthetized with a pentobarbital (45 mg/kg) and chloral hydrate (3 mL/kg) cocktail. A 5 mm segment of sciatic nerve, including the lesion and DRGs from the forth lumbar vertebra (L4) through to sixth lumbar vertebra (L6), were harvested from each rat. Tissues were stored at –70°C until further processing. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol® LS Reagent and RT-PCR was performed using the Total RNA Extraction Kit. PCR was conducted for 30 to 35 cycles with the following conditions and primers: BDNF for 30 seconds at 56°C (5’-AGC CTC CTC TAC TCT TTC TG-3’ and 5’-TCC ACT ATC TTC CCC TTT TA-3’), TrkB receptor (full length) for 1 minute at 54°C (5’-CTC AGC AAA TCG CAG CAG G-3’ and 5’-AGT AGT CGG TGC TGT ATA-3’), p75 for 90 seconds at 60°C (5’-GTG TTC TCC TGC CAG GAC AA-3’ and 5’-GCA GCT GTT CCA CCT CTT GA-3’) and GAPDH for 90 seconds at 60°C (5’-GGC ATT GCT CTC AAT GAC AA-3’ and 5’-TGT GAG GGA GAT GCT CAG TG-3’). PCR products were run on a 1.2% agarose gel and normalized to GAPDH mRNA level. Relative quantitative analysis was performed using the Multi Gauge 3.0 program (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

Gait analysis with SFI

Gait analysis using a walking track has been widely used to assess the functional recovery of motor axons after sciatic nerve injury[45,46]. Rats in each group had their hindpaws painted with blank ink and were applied to the paper-covered walking track. Footprints were recorded at 1, 2, 3 and 4 weeks after injection of human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells or PBS (n = 6–11 rats/group). The following factors regarding each footprint of the normal (N) and experimental (E) paws were measured: print length (PL, the longitudinal distance between the tip of the longest toe and the heel), toe spread (TS, the distance between the first and fifth toes) and intermediary toe spread (IT, the distance between the second and fourth toes). The SFI was calculated using the following equation:

SFI = –38.3 × (EPL – NPL)/NPL + 109.5 × (ETS – NTS)/NTS + 13.3 × (EIT – NIT)/NIT– 8.8.

The SFI value can range from 0 (normal function) to –100 (dysfunction)[45].

Retrograde labeling

Retrograde axonal tracing with fluorescent markers is one of several methods to evaluate functional recovery in peripheral nerve regeneration[38,39,40]. At 4 weeks post-surgery, the sciatic nerve was sharply cut 10 mm distal to the crush-injury site. The proximal nerve end was then soaked for 1 hour in 20 μL 4% Fluoro Gold diluted in distilled water, prior to irrigation with saline. The wound was then closed (n = 5 rats per group). As a negative control, 20 μL of distilled water only was used to soak the proximal nerve end (n = 1 rat per group). As a positive control, the uninjured sciatic nerve (n = 1 rat per group) was soaked in 4% Fluoro Gold. Retrograde transport of Fluoro Gold from the cut end of nerve to the DRGs was permitted for 5 days. Transcardial perfusion was then performed with 4% neutral buffered formalin solution following a heparinized phosphate buffer rinse. The L4-6 DRGs were harvested from each rat and post-fixed with 4% neutral buffered formalin. Each DRG was embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound and serially sliced to 20 μm-thick sections at 40 μm intervals using a cryotome (CM3050, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). In total, 30 to 40 serial sections per DRG were obtained on silane-coated slides (MUTO, Tokyo, Japan) and each section was captured with a confocal laser scanning microscope (Fluoroview FV300, Olympus, Nagano, Japan). To compare Fluoro Gold-labeled DRG neuron counts between groups, three equatorial sections per DRG were selected and neurons intensely expressing gold/yellow fluorescence were counted and averaged.

Histomorphometric analysis

At 4 weeks post-injection of human umbilical cord blood-mesenchymal stem cells or PBS, rats were sacrificed and a 10 mm segment of sciatic nerve, including the crush-injury site, was excised (n = 6 each group). Samples were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4), cut transversely at the center of the lesion and post-fixed with 2% osmium tetroxide solution. The fixed nerve was embedded in Epon 812 (Nisshin EM, Tokyo, Japan), sectioned to 1 μm thickness and stained with toluidine blue. To evaluate axonal regeneration between groups, we measured the total fascicular area and counted the number of axons in three randomly selected fields per fascicle using an image analyzing system (Optimas 6.5 software, CyberMetrics, Scottsdale, USA). Axon density and total axon number were calculated directly by the software[12].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by analysis of variance and the Mann-Whitney test using STATVIEW 5.0.1 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05. The results are presented using GraphPad PRISM (version 3.02, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Prof. Kang’s laboratory members (Department of Stem Cells and Tumor Biology, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea) for their technical help and comments on this work. We would also like to thank Mr. Jin Young Kim for his help with animal care.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a grant of the Seoul National University Dental Hospital, Republic of Korea, No. 03-2010-0020.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Ethical approval: Care and treatment of the animals were conducted in accordance with guidelines established by Seoul National University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Approval No. SNU-090623-5).

(Edited by Lee JE, Wang PJ,Johri A/Song LP)

REFERENCES

- [1].Chen ZL, Yu WM, Strickland S. Peripheral regeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:209–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Guénard V, Kleitman N, Morrissey TK, et al. Syngeneic Schwann cells derived from adult nerves seeded in semipermeable guidance channels enhance peripheral nerve regeneration. J Neurosci. 1992;12(9):3310–3320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-09-03310.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kim SM, Lee SK, Lee JH. Peripheral nerve regeneration using a three dimensionally cultured schwann cell conduit. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18(3):475–488. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000249362.41170.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mosahebi A, Woodward B, Wiberg M, et al. Retroviral labeling of Schwann cells: in vitro characterization and in vivo transplantation to improve peripheral nerve regeneration. Glia. 2001;34(1):8–17. doi: 10.1002/glia.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mosahebi A, Fuller P, Wiberg M, et al. Effect of allogeneic Schwann cell transplantation on peripheral nerve regeneration. Exp Neurol. 2002;173(2):213–223. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dezawa M, Takahashi I, Esaki M, et al. Sciatic nerve regeneration in rats induced by transplantation of in vitro differentiated bone-marrow stromal cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14(11):1771–1776. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].di Summa PG, Kingham PJ, Raffoul W, et al. Adipose-derived stem cells enhance peripheral nerve regeneration. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(9):1544–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Marchesi C, Pluderi M, Colleoni F, et al. Skin-derived stem cells transplanted into resorbable guides provide functional nerve regeneration after sciatic nerve resection. Glia. 2007;55(4):425–438. doi: 10.1002/glia.20470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sasaki R, Aoki S, Yamato M, et al. Tubulation with dental pulp cells promotes facial nerve regeneration in rats. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14(7):1141–1147. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tohill M, Mantovani C, Wiberg M, et al. Rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells express glial markers and stimulate nerve regeneration. Neurosci Lett. 2004;362(3):200–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Al-Majed AA, Neumann CM, Brushart TM, et al. Brief electrical stimulationpromotes the speed and accuracy of motor axonal regeneration. J Neurosci. 2000;20(7):2602–2608. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-07-02602.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Alrashdan MS, Park JC, Sung MA, et al. Thirty minutes of low intensity electrical stimulation promotes nerve regeneration after sciatic nerve crush injury in a rat model. Acta Neurol Belg. 2010;110(2):168–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Madduri S, di Summa P, Papaloïzos M, et al. Effect ofcontrolled co-delivery of synergistic neurotrophic factors on early nerve regeneration in rats. Biomaterials. 2010;31(32):8402–8409. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].D’Ippolito G, Schiller PC, Ricordi C, et al. Age-related osteogenic potential of mesenchymal stromal stem cells from human vertebral bone marrow. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(7):1115–1122. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.7.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kern S, Eichler H, Stoeve J, et al. Comparative analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, or adipose tissue. Stem Cells. 2006;24(5):1294–1301. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Harris DT. Cord blood stem cells: a review of potential neurological applications. Stem Cell Rev. 2008;4(4):269–274. doi: 10.1007/s12015-008-9039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hirata Y, Sata M, Motomura N, et al. Human umbilical cord blood cells improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;327(2):609–614. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sun B, Roh KH, Park JR, et al. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stromal cells in a mouse breast cancer metastasis model. Cytotherapy. 2009;11(3):289–298. doi: 10.1080/14653240902807026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Goodwin HS, Bicknese AR, Chien SN, et al. Multilineage differentiation activity by cells isolated from umbilical cord blood: expression of bone, fat, and neural markers. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;7(11):581–588. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11760145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].van de Ven C, Collins D, Bradley MB, et al. The potential of umbilical cord blood multipotent stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissue and cell regeneration. Exp Hematol. 2007;35(12):1753–1765. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hao L, Zhang C, Chen XH, et al. Human umbilical cord blood-derived stromal cells suppress xenogeneic immune cell response in vitro. Croat Med J. 2009;50(4):351–360. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2009.50.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Liao W, Zhong J, Yu J, et al. Therapeutic benefit of human umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stromal cells in intracerebral hemorrhage rat: implications of anti-inflammation and angiogenesis. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2009;24(3-4):307–316. doi: 10.1159/000233255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Vendrame M, Gemma C, de Mesquita D, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of human cord blood cells in a rat model of stroke. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14(5):595–604. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wang M, Yang Y, Yang D, et al. The immunomodulatory activity of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Immunology. 2009;126(2):220–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02891.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fan CG, Zhang QJ, Tang FW, et al. Human umbilical cord blood cells express neurotrophic factors. Neurosci Lett. 2005;380(3):322–325. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kim SW, Han H, Chae GT, et al. Successful stem cell therapy using umbilical cord blood-derived multipotent stem cells for Buerger's disease and ischemic limb disease animal model. Stem Cells. 2006;24(6):1620–1626. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Newman MB, Davis CD, Borlongan CV, et al. Transplantation of human umbilical cord blood cells in the repair of CNS diseases. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4(2):121–130. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Newman MB, Willing AE, Manresa JJ, et al. Stroke-inducedmigration of human umbilical cord blood cells: time course and cytokines. StemCells Dev. 2005;14(5):576–586. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Vendrame Vendrame M, Cassady J, Newcomb J, et al. Infusion of human umbilical cord blood cells in a rat model of stroke dose-dependently rescues behavioral deficits and reduces infarct volume. Stroke. 2004;35(10):2390–2395. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000141681.06735.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zigova T, Song S, Willing AE, et al. Human umbilical cord blood cells express neural antigens after transplantation into the developing rat brain. Cell Transplant. 2002;11(3):265–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jablonska A, Kozlowska H, Markiewicz I, et al. Transplantation of neural stem cells derived from human cord blood to the brain of adult and neonatal rats. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2010;70(4):337–350. doi: 10.55782/ane-2010-1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Glover JC, Boulland JL, Halasi G, et al. Chimeric animal models in human stem cell biology. ILAR J. 2009;51(1):62–73. doi: 10.1093/ilar.51.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Boyd JG, Gordon T. The neurotrophin receptors, trkB and p75, differentially regulate motor axonal regeneration. J Neurobiol. 2001;49(4):314–325. doi: 10.1002/neu.10013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Boyd JG, Gordon T. Neurotrophic factors and their receptors in axonal regeneration and functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury. Mol Neurobiol. 2003;27(3):277–324. doi: 10.1385/MN:27:3:277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fu SY, Gordon T. The cellular and molecular basis of peripheral nerve regeneration. Mol Neurobiol. 1997;14(1-2):67–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02740621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Meyer M, Matsuoka I, Wetmore C, et al. Enhanced synthesis of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the lesioned peripheral nerve: different mechanisms are responsible for the regulation of BDNF and NGF mRNA. J Cell Biol. 1992;119(1):45–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sebert ME, Shooter EM. Expression of mRNA for neurotrophic factors and their receptors in the rat dorsal root ganglion and sciatic nerve following nerve injury. J Neurosci Res. 1993;36(4):357–367. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490360402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Choi D, Li D, Raisman G. Fluorescent retrograde neuronal tracers that label the rat facial nucleus: a comparison of Fast Blue, Fluoro-ruby, Fluoro-emerald, Fluoro-Gold and DiI. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;117(2):167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Novikova L, Novikov L, Kellerth JO. Persistent neuronal labeling by retrogradefluorescent tracers: a comparison between Fast Blue, Fluoro-Gold and various dextran conjugates. J Neurosci Methods. 1997;74(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)02227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Richmond FJ, Gladdy R, Creasy JL, et al. Efficacy ofseven retrograde tracers, compared in multiple-labelling studies of felinemotoneurones. J Neurosci Methods. 1994 Jul;53(1):35–46. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90142-2. Erratum in: J Neurosci Methods. 1995; 58(1-2):221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Coggeshall RE. A consideration of neural counting methods. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15(1):9–13. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90339-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Asato F, Butler M, Blomberg H, et al. Variation in rat sciatic nerve anatomy: implications for a rat model of neuropathic pain. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2000;5(1):19–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8027.2000.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Rigaud M, Gemes G, Barabas ME, et al. Species and strain differences in rodent sciatic nerve anatomy: implications for studies of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2008;136(1-2):188–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Seo KW, Lee SR, Bhandari DR, et al. OCT4A contributes to the stemness and multi-potency of human umbilical cord blood-derived multipotent stem cells (hUCB-MSCs) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;384(1):120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Bain JR, Mackinnon SE, Hunter DA. Functional evaluation of complete sciatic, peroneal, and posterior tibial nerve lesions in the rat. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83(1):129–138. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198901000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sarikcioglu L, Demirel BM, Utuk A. Walking track analysis: an assessment method for functional recovery after sciatic nerve injury in the rat. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 2009;68(1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]