Abstract

Background:

The purpose of this study was to assess the efficacy of hyaluronic acid (HA) in root coverage procedures as an adjunct to coronally advanced flap (CAF) procedure.

Materials and Methods:

This was a randomized clinical trial with split mouth design, where 10 patients with 20 sites of Millers Class I recession were treated and followed-up for a period of 6 months. CAF procedure was performed, HA was applied onto the experimental sites before suturing the flap. Recession depth (RD) was measured regularly at baseline 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 weeks postoperatively. Probing pocket depth (PPD) and clinical attachment level (CAL) were also measured along with RD at baseline and 12 and 24 weeks.

Results:

There was a significant change in RD, PPD, CAL, and percentage of root coverage in both groups when compared to the baseline values. There was no statistically significant difference between experimental and control group in terms of RD (P = 0.917), PPD (P = 0.917) and CAL (P = 0.761). RD was 3.2 mm ± 0.78 mm in experimental site and control sites 2.9 mm ± 0.73 mm reduced to 1.1 mm ± 0.99 mm in experimental sites and 1.0 mm ± 0.66 mm in control sites. Though, there is no statistically significant difference root coverage in the experimental group appeared to be clinically more stable compared with the control group after 24 weeks.

Conclusions:

This study suggests that use of HA may improve the clinical outcome of root coverage with CAF procedure.

Keywords: Gingival recession, hyaluronic acid, wound healing

INTRODUCTION

Recession is a very common condition and its extent and prevalence increases with age. It is estimated that around 50% of the population has one or more sites with 1 mm or more of such root exposure. This prevalence rate increases to > 88% in individuals who are 65 years or older.[1]

Patients often have esthetic concerns due to increased clinical crown height. In some instances, they may experience dental hypersensitivity. Biological and functional issues associated with mucogingival problems also dictate the need for treatment. Key factors in the treatment of gingival recession are to prevent the progressive marginal tissue recession and to facilitate plaque control in the affected area.[2]

Various treatment modalities have been put forth for the correction of gingival recession. These include free gingival autograft, sub-epithelial connective tissue graft (SCTG), coronally advanced flap (CAF). It is seen that the incidence of adverse effects, such as discomfort with or without pain, was directly related to the donor sites of SCTG. Hence despite SCTG being the gold standard for root coverage research is always aimed at finding a suitable alternative to this procedure to reduce patient morbidity.[3]

Coronally advanced flap first described by Norberg in 1926. This procedure has been modified by many others with an intention to improve the stability and predictability of this technique. In a recent 14 year follow-up study Pini Prato et al. has shown a 39% of recurrence in patients treated with CAF.[4] Hence this procedure is now generally employed with adjuncts such as guided tissue regeneration membrane, emdogain, acellular dermal matrix and platelet rich plasma to enhance its long term stability. However, evidence regarding the beneficial impact of these procedures on the stability of root coverage is inconclusive.[3]

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a linear polysaccharide found in extracellular matrices of skin. Hyaluronan has many structural and physiological functions within tissues, including extracellular and cellular interactions, growth factor interaction and the regulation of osmotic pressure and tissue lubrication, which helps in the maintenance of the structural and homeostatic integrity of tissues.[5]

Hyaluronic acid is one of the most hygroscopic molecules known in nature. One gram of HA can bind up to 6 L of water. As a physical background material, it has functions in space filling, lubrication, shock absorption, and protein exclusion.[6]

According to various clinical studies hyaluronan undergoes degradation in chronically inflamed gingival tissues, whereas the proteoglycan associated sulfated glycosaminoglycans, such as chondroitin 4-sulphate and dermatan sulfate, remain relatively intact. HA is a potent anti-inflammatory agent and modulates wound healing due to its ability to scavenge the inflammatory cells-derived reactive oxygen species.[7]

This study is aimed at testing the efficacy of hyaluronan gel as an adjunct to CAF in root coverage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a randomized clinical trial with split mouth study design, carried out in the postgraduate clinic of Department of Periodontics, Coorg Institute of Dental Sciences, Virajpet. The study sample included 10 subjects of which seven are male, and three female (at least 20 sites) having Miller's Class I gingival recession on the canine and premolar region were recruited from Department of Periodontics, Coorg Institute of Dental Sciences. The sample size was calculated adjusting the minimum acceptable power of study at 80% and maximum allowable alpha error at 5%. The recession defects were designated as experimental and control sites randomly prior to surgery by spin of a coin.

Experimental group includes hyaluronan gel (gengigel 0.2% gel which is 0.2% hyaluronan gel marketed by Ricerfarma pharmaceuticals, Milan, Italy) with CAF and control group with CAF alone.

This self-funded study was approved by institutional ethical committee, and the procedure and the procedure was explained to all the subjects who provided signed informed consent before participation. Medical and dental examination was obtained from all the individuals who were followed by complete periodontal examination. Subjects were excluded if they were smokers, pregnant women or medically compromised. Patients with malaligned teeth, teeth in trauma from occlusion, cervical abrasion and restorations were also excluded. Subjects were included who are systemically healthy with two or more sites of Miller's Class I recession and those who can understand and follow oral hygiene instructions properly.

At baseline the following clinical parameters were measured using UNC 15 probe.

Recession depth (RD)

Probing depth (PD)

Clinical attachment level (CAL).

Clinical examination, group allocation and sampling site selection were performed by one examiner moogala srinivas (MS) with a UNC 15 probe and rounded off to the nearest 0.5 mm. The RD was assessed at baseline, 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 weeks, and the PD and CAL were recorded at 12 and 24 weeks with the patients consent.

Treatment protocol

The patients who were selected and gave their approval for the surgical intervention were educated and motivated with more emphasis on proper oral hygiene maintenance. All the patients underwent the initial phase of treatment of thorough scaling and root planning.

Surgical technique

All the surgical procedures were carried out by one operator. The sites were randomly assigned to the control group or the test group using a flip coin technique immediately before surgery.

The surgical area was prepared with adequate anesthesia using 2% lignocaine HCL containing 1:80,000 epinephrine. After local anesthesia and before the elevation of the flap, both the exposed root surfaces were gently planned with a sharp Gracey no. 1–2 curettes to reduce root convexity. Immediately after, the root surface was washed for 60 s with water spray. Intrasulcular incisions were then made with a blade (no. 15) on the buccal aspect of the involved tooth. This incision was horizontally extended to the adjacent papillae avoiding the gingival margin of the adjacent teeth. Two oblique releasing incisions were carried out from the mesial, and distal extremities of the horizontal incision beyond the mucogingival junction [Figure 1a]. A trapezoidal full-thickness flap was raised with a periosteal elevator, until the mucogingival junction. Then a partial-thickness dissection was carried out apically leaving the underlying periosteum in place. In addition a mesiodistal and apical dissection parallel to the vestibular lining mucosa was performed with a blade to release residual muscle tension and to facilitate the passive coronal displacement of the flap. The papillae adjacent to the involved tooth were de-epithelized. The flap was then advanced coronally and adapted to cover the cementoenamel junction.[8]

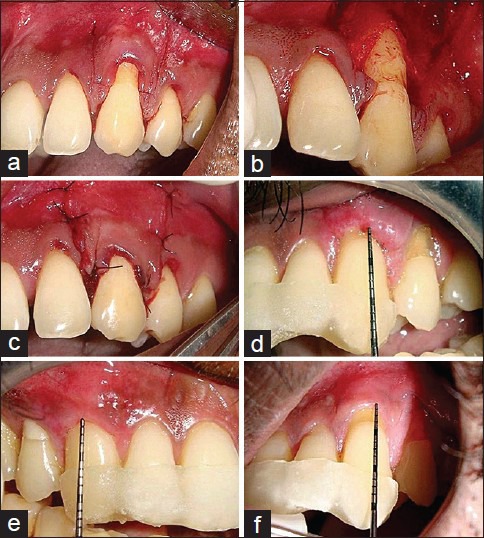

Figure 1.

(a) Horizontal and vertical incisions given in relation to 23; (b) Hyaluronan gel applied on the root surface of experimental site; (c) Suturing done. (d) Postoperative 1-week in the control site; (e) Postoperative 24 weeks in the experimental site; (f) Postoperative 24 weeks in the control site

In the experimental group, hyaluronan gel (gengigel 0.2%) applied on the root surface using a sterile instrument prior to flap advancement and suturing [Figure 1b] whereas in the control group the flap was advanced coronally without application of HA gel. Suturing of oblique releasing incisions was performed, with 5-0 ethicon nonresorbable sutures, while the coronal mesial and distal extremities of the flap were secured by two single sutures placed in the interdental areas [Figure 1c].[9] Additional interrupted sutures were applied, when necessary, to close the oblique releasing incisions in the alveolar mucosa.

Postsurgical care

Immediately following surgery, use of ice packs was recommended for 3 h. All patients were instructed to discontinue tooth brushing, avoid trauma around the surgical site. In the event of pain, the use of ibuprophen + paracetamol (thrice daily) was recommended. A 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate solution rinse was prescribed 2 times (60 s) daily for the first 10 days. The sutures were removed after 7 days [Figure 1d]. The patients were instructed to clean the surgical sites with a cotton pellet soaked in a 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate solution twice daily for 10 days. Three weeks after surgery, the patients were instructed to resume mechanical tooth cleaning of the treated areas using a soft toothbrush with a careful roll technique. Adverse effects such as inflammation, bleeding on probing, pain and abscess formation were assessed postsurgically by first examiner (MS).

Data collection

The patients were recalled for collection of data at 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 weeks using prefabricated acrylic stent. Both experimental group and control group sites were evaluated postoperatively at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 weeks after surgery [Figure 1e and f]. Stent made of acrylic was used to standardize the direction and position of the probe. On each visit, the area was checked for meticulous plaque control, but no subgingival instrumentation was performed until the 6th week.

Statistical analysis

A total of 20 buccal gingival recession sites in 10 patients were considered for the study. The values obtained were tabulated and statistically analyzed using Student's t-test and repeated measure ANOVA tests. All the statistical methods were carried out through the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) for Windows (version 16.0).

The descriptive procedure displays univariate summary statistics for several variables in a single table and calculates standardized values (z scores). Using the general linear model procedure, null hypotheses about the effects of both within and between the subject factors is tested. In addition, the effects of constant covariates and covariate interactions between-subjects factors can be included.

RESULTS

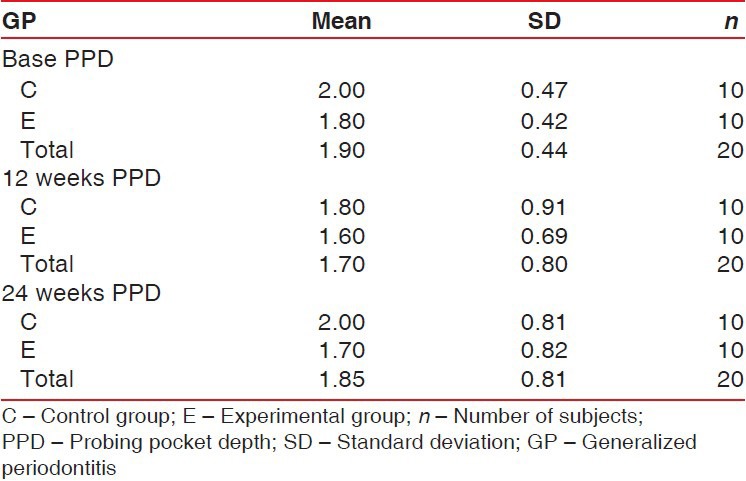

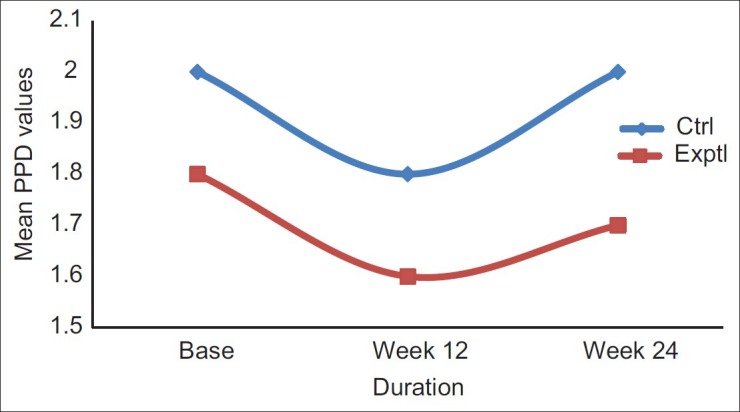

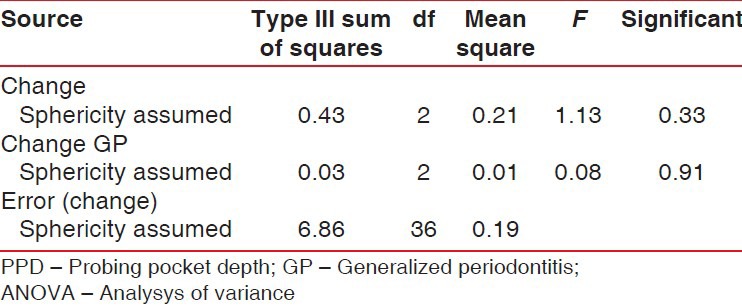

Throughout the study period the patients maintained a good standard of supragingival plaque control. No adverse events were recorded during the postoperative period. Mean probing pocket depth (PPD) in experimental sites at baseline was 1.8 ± 0.42 mm, and in control sites it was 2.0 ± 0.47 mm. At the end of 24 weeks, mean PD was 1.7 mm ± 0.82 in experimental sites and 2.0 mm ± 0.81 mm in control sites [Table 1 and Figure 2]. The overall comparisons between the two groups were not statistically significant (P = 0.917) [Table 2].

Table 1.

Mean PPD in mm. Descriptive analysis of two groups

Figure 2.

Mean probing pocket depth values plotted against time for experimental and control groups

Table 2.

Results of repeated measure ANOVA for PPD for between experimental and control groups

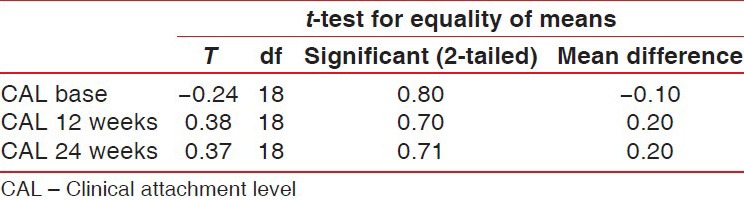

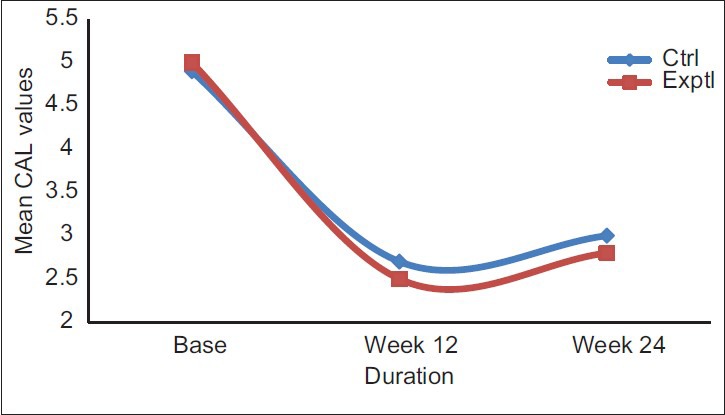

Clinical attachment level had a significant gain and stability, at 24 weeks follow-up both groups. CAL gain was significant for both groups, but no intergroup difference was reported at 12 months [Table 3 and Figure 3].

Table 3.

Student's t-test showing the CAL difference between control and experimental groups

Figure 3.

Comparison of mean clinical attachment level values between experimental and control groups

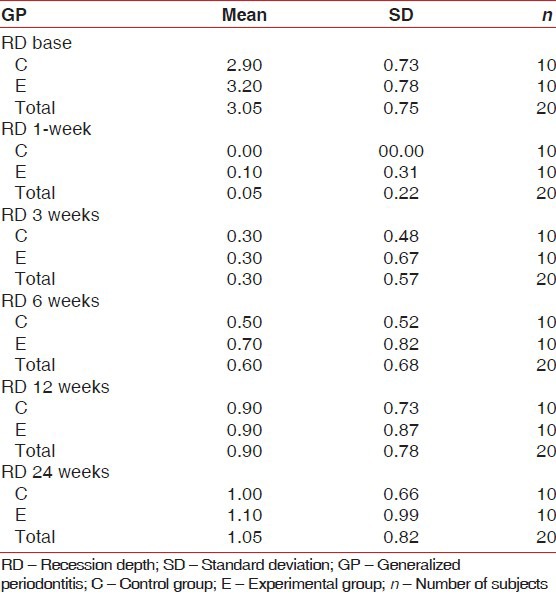

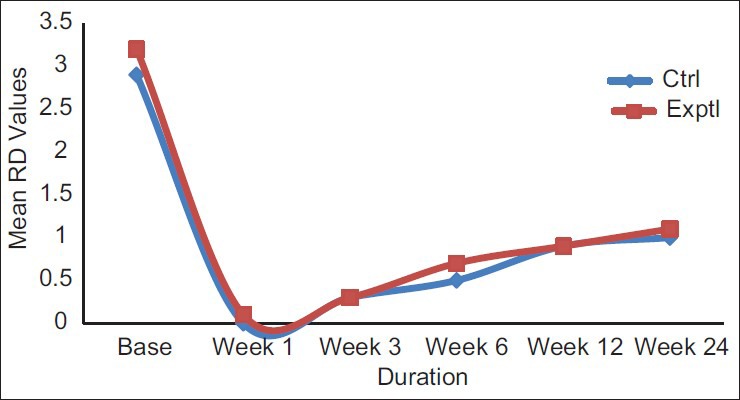

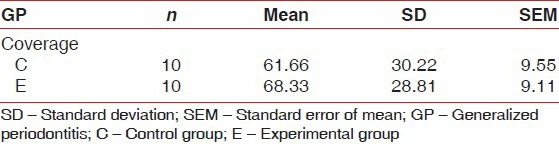

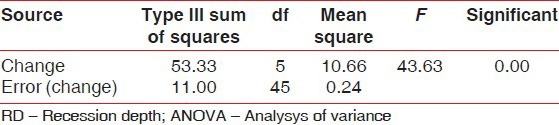

On an average, experimental site showed initial RD of approximately 3.2 mm ± 0.78 mm and control sites 2.9 mm ± 0.73 mm. After 24 weeks, mean RD was 1.1 mm ± 0.99 mm in experimental sites and 1.0 mm ± 0.66 mm in control sites [Table 4 and Figure 4]. The percentage of root coverage for experimental and control group was 68.33% ±28% and 61.67% ±30.22%, respectively [Table 5 and Figure 5].

Table 4.

Mean RD in mm. Descriptive analysis of two groups

Figure 4.

Mean recession depth values plotted against time for experimental and control groups

Table 5.

Percentage of root coverage

Figure 5.

Comparison of mean percentage of root coverage between control (C) and experimental (E) group

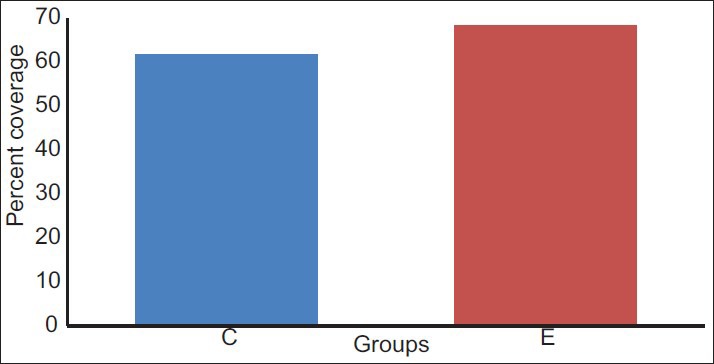

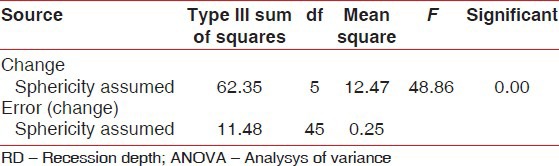

At 24 weeks, the change in RD was statistically significant (P = 0.00) in both groups [Tables 6 and 7]. The intergroup analysis however failed to show statistical significance.

Table 6.

Results of repeated measure ANOVA for RD for experimental group

Table 7.

Results of repeated measure ANOVA for RD for control group

DISCUSSION

There are many factors that determine success of root coverage procedures namely, gingival biotype, amount of keratinized tissue, location of the tooth in the arch, prominence of the root, RD and width.[10] Other than these local factors there are other factors like patient compliance, brushing technique,[11] use of tobacco,[12] etc., that determine success and long term stability of root coverage procedures.

Hyaluronan has shown promise in the field of regenerative therapy. It is a linear polysaccharide and one of the principle components of the extracellular matrix, which is biodegradable, biocompatible and nontoxic. HA is a macromolecule of several million Daltons, consisting of repeating units of D-glucoronic acid (1-β-3) N-Acetyl –D- glucosamine (1-β4) n.[13] Exogenous application of hyaluronan has shown to have anti edema, anti-inflammatory and good wound healing properties.[13] It has been used extensively in the field of dentistry for its various beneficial applications. In periodontics it has been used to treat gingivitis[14] and periodontitis[15] and more recently in the treatment of periodontal intra bony defects.[16] The present study was conceived in an effort to merge two simple and cost effective techniques to achieve better root coverage. A split mouth study design was considered appropriate to minimize the bias that would arise due to variations in healing pattern among individuals.

Complete root coverage was achieved immediately following the surgical procedures in all cases except one in the experimental group. During the study, all patients were recalled after 3 months for oral prophylaxis regimen. After 24 weeks, 100% root coverage was seen in six sites out of which only two were control sites. That is, at the end of 24 weeks, 40% of experimental sites demonstrated 100% root coverage [Figure 1e], whereas only 20% of the control sites showed complete root coverage [Figure 1f]. This suggests that clinically the root coverage achieved with the use of hyaluronan gel is more predictable at the end of 24 weeks. Percentage of root coverage in the experimental sites was 68.3% and control sites were 61.6%. This is in accordance with the systematic review by Chambrone et al.[3] which said that that the mean root coverage for CAF alone was ranging from 55.9% to 86.7%.[3]

The biological properties of hyaluronan as reported by studies by Ballini et al.[16] suggests that it promotes regeneration. The clinical stability of the root coverage achieved after 24 weeks in this study supports this aspect of previous studies. It has been suggested from previous animal studies[17] that there is an increase in hard tissue component of the periodontium following treatment with hyaluronan. It promotes wound healing by cell migration and proliferation, facilitating white blood cell infiltration and improving tissue hydration.[13] This could contribute to better stability of the root coverage procedures that is seen with the use of hyaluronan.

Hyaluronan as previously mentioned has been extensively studied in the field of dentistry, but to the best of our knowledge, there is no published data on the usage of HA in the treatment of root coverage procedures. Hence, it is premature at this point to make a comparison of the results of this study with previous studies. The cases were followed for a period of 6 months. A longer follow-up is required to know the long-term stability of the treatment procedures.

However, this study has some limitations. It is entirely based on clinical parameters, where in the exact nature of periodontal regeneration achieved could be made only by histological evaluation, studies with large sample size and higher statistical power are needed in the future to explore and establish use of hyaluronan as an adjunct in periodontal surgeries.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that hyaluronan affects treatment outcome when used as an adjunct to CAF procedure. Although results are not statistically significant, clinically experimental group shows better results as compared to the control group. Though CAF gives 100% coverage immediately following the surgery only 61-64% can be expected 24 weeks after surgery. Hyaluronan can be easily combined with CAF procedure in compromised cases and situations where more stable results are desired.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kassab MM, Cohen RE. The etiology and prevalence of gingival recession. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:220–5. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith RG. Gingival recession. Reappraisal of an enigmatic condition and a new index for monitoring. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:201–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambrone L, Sukekava F, Araújo MG, Pustiglioni FE, Chambrone LA, Lima LA. Root-coverage procedures for the treatment of localized recession-type defects: A Cochrane systematic review. J Periodontol. 2010;81:452–78. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pini Prato G, Rotundo R, Franceschi D, Cairo F, Cortellini P, Nieri M. Fourteen-year outcomes of coronally advanced flap for root coverage: Follow-up from a randomized trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:715–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laurent TC, Fraser JR. Hyaluronan. FASEB J. 1992;6:2397–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bansal J, Kedige SD, Anand S. Hyaluronic acid: A promising mediator for periodontal regeneration. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21:575–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.74232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moseley R, Waddington RJ, Embery G. Hyaluronan and its potential role in periodontal healing. Dent Update. 2002;29:144–8. doi: 10.12968/denu.2002.29.3.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldi C, Pini-Prato G, Pagliaro U, Nieri M, Saletta D, Muzzi L, et al. Coronally advanced flap procedure for root coverage. Is flap thickness a relevant predictor to achieve root coverage? A 19-case series. J Periodontol. 1999;70:1077–84. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.9.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen EP, Miller PD., Jr Coronal positioning of existing gingiva: Short term results in the treatment of shallow marginal tissue recession. J Periodontol. 1989;60:316–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1989.60.6.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang LH, Neiva RE, Wang HL. Factors affecting the outcomes of coronally advanced flap root coverage procedure. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1729–34. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.10.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zucchelli G, De Sanctis M. Long-term outcome following treatment of multiple Miller class I and II recession defects in esthetic areas of the mouth. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2286–92. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.12.2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva CO, Sallum AW, de Lima AF, Tatakis DN. Coronally positioned flap for root coverage: Poorer outcomes in smokers. J Periodontol. 2006;77:81–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.77.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferguson EL, Roberts JL, Moseley R, Griffiths PC, Thomas DW. Evaluation of the physical and biological properties of hyaluronan and hyaluronan fragments. Int J Pharm. 2011;420:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jentsch H, Pomowski R, Kundt G, Göcke R. Treatment of gingivitis with hyaluronan. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:159–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.300203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johannsen A, Tellefsen M, Wikesjö U, Johannsen G. Local delivery of hyaluronan as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1493–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ballini A, Cantore S, Capodiferro S, Grassi FR. Esterified hyaluronic acid and autologous bone in the surgical correction of the infra-bone defects. Int J Med Sci. 2009;6:65–71. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aslan M, Simsek G, Dayi E. The effect of hyaluronic acid-supplemented bone graft in bone healing: Experimental study in rabbits. J Biomater Appl. 2006;20:209–20. doi: 10.1177/0885328206051047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]