Abstract

Restoration of lost alveolar bone support remains as one of the main objectives of periodontal surgery. Amongst the various types of bone grafts available for grafting procedures, autogenous bone grafts are considered to be the gold standard in alveolar defect reconstruction. Although there are various sources for autogenous grafts including the mandibular symphysis and ramus, they are almost invariably not contiguous with the area to be augmented. An alternative mandibular donor site that is continuous with the recipient area and would eliminate the need for an extra surgical site is the tori/exostoses. Bone grafting was planned for this patient as there were angular bone loss present between 35-36 and 36-37. As the volume of bone required was less and bilateral tori were present on the lingual side above the mylohyoid line, the tori was removed and used as a source of autogenous bone graft, which were unnecessary bony extensions present on the mandible and continuous with the recipient area. Post-operative radiographs taken at 6 and 12 month intervals showed good bone fill and also areas of previous pockets, which did not probe after treatment indicates the success of the treatment. The use of mandibular tori as a source of autogenous bone graft should be considered whenever a patient requires bone grafting procedure to be done and presents with a tori.

Keywords: Autogenous bone grafts, bone defects, mandibular tori

INTRODUCTION

One of the important objectives of periodontal surgery is restoration of alveolar bone. Over the years, it has been demonstrated that this objective can be achieved by the insertion of a variety of materials in the bony defect (bone grafts). There are basically four different types of bone graft materials (viz: Autograft, allografts, xenografts and alloplast) that can be used in periodontal regeneration. Among these, autogenous bone grafts originate from the patient and are considered to be the optimal choice for augmentation.[1] Various anatomic locations have been utilized as donor sites, and the techniques are well described in the literature.

Bone has been harvested successfully from the local areas of the mandible and maxilla and distant sites, such as the ilium, tibia, scapula, clavicle and calvarium. Due to the location and complexity of the harvesting procedure, most of these techniques require a comprehensive surgical protocol. Grafts from the local sites provide advantages that may include an in-office outpatient procedure, reduced operative period and decreased morbidity for the patient.

Intra-orally mandibular donor bone is preferred over maxillary bone.[2] Mandibular symphysis and ramus have been utilized successfully for various augmentation procedures. One region that has not been previously described as a potential donor site is the mandibular torus.

REVIEW: THE TORI

It is defined as a congenital bony protuberance with benign characteristics, leading to the overworking of osteoblasts and bone to be deposited along the line of fusion of the palate or on the hemi-mandibular bodies.[3] Mandibular tori are usually symmetrical and bilateral, but can also be unilateral, located on the lingual side of the mandible, above the mylohyoid line, and at the level of premolars, but it may extend distally to the third molar and mesially to the lateral incisor.[4] The etiology of the mandibular torus has not been determined clearly, though both genetic factors and environmental factors such as diet, presence of teeth and occlusal load are thought to be involved.[5] Some studies have suggested that genetic predisposition to mandibular torus may be inherited in a dominant manner.[6] In relation to the role of environmental factors, one study suggested a correlation between the number of existing teeth and incidence of mandibular torus, as the number of existing teeth was significantly higher in patients with mandibular torus than in those without mandibular torus.[7] Further occlusal stress such as bruxism and teeth clenching have been noted to be involved in the development of the condition.

The following reasons have been attributed for the occurrence of tori[3,8]

Genetics

Environmental factors related to occlusal stress.

Parafunctional habits

Temporomandibular joint disorders

Eating habits, states of vitamin deficiency or supplements rich in calcium and also diet.

The prevalence of the appearance of the mandibular tori ranges from 12.3% to 14.6%;[9] the average age when experiencing the onset of tori is 34 years. The appearance of mandibular tori is rare before the first decade of life. The appearance of tori is more common in certain ethnic groups and countries (Eskimos, Japanese and in the United States). A great predisposition towards the appearance of mandibular tori has been observed among Mongols. The populations in which elevated occurrence of tori were among North Americans (Caucasians and African Americans) 11%, Norwegians 14.22% and Thais 3.5%. Six to seven percent occurrence was observed in Asian populations and it is more common in males than in females.

The size of the tori may vary from few mm to few cm in diameter. The size of the tori may fluctuate throughout life, and in some cases the tori can be large enough to touch each other in the midline of mouth. As a result of this, it is believed that mandibular tori are the result of local stresses and not solely of genetic influences. Two classification systems are followed based on the size of the tori

Haguen et al.[10]

Small <2 mm

Medium 2-4 mm

Large >4 mm

Reichart et al.[11]

Grade 1 – small up to 3 mm

Grade 2 – moderate up to 6 mm

Grade 3 – marked above 6 mm

Mandibular tori are usually nodular, unilateral or bilateral single or multiple. Various studies have shown that among the cases of occurrence, mandibular tori the most was nodular in 61% of the cases and bilateral in 87% of the cases.[12]

Mandibular tori are usually a clinical finding with no treatment necessary until there is complaint of pain, speech defect. Ulcers can form on the area of the tori due to trauma. The tori may also complicate the fabrication of dentures. Removal of the tori can be considered during the following conditions.[13]

When it interferes with the patients oral hygiene performance

Prosthodontic reconstruction

Interference with tongue positioning

Traumatic ulceration from mastication

Speech interference

Cancerphobia.

In cases were the tori excision is indicated, surgery can be done to reduce the amount of bone, but chances of recurrence is more in cases where adjacent teeth still receive local stresses. When excision is planned, the tori may be either removed with a chisel or via bone bur by smoothening through the base of the bony tori.

Common complications of surgery include lingual nerve damage in cases of distally extended tori, infection and floor of mouth hemorrhage. Though hemorrhage occurs in rare cases it can be life threatening and must be managed immediately to prevent airway obstruction.[14]

CASE REPORT

A 44-year-old male reported with a chief complaint of food impaction and bleeding while brushing in relation to his right lower back teeth for the past three months. On clinical examination, there were clinical signs of gingival inflammation with generalized bleeding on probing. Periodontal pockets were detected using a William's periodontal probe; pocket depth of 7 mm and clinical loss of attachment of 5 mm was noticed on the mesial aspect of 36 the loss of attachment was calculated by using the crown margin as a fixed reference point, and furcation involvement Gr-II in 17 and Gr-I in 47 were noticed and the oral hygiene status was fair. A provisional diagnosis of chronic generalized periodontitis (mild) was made. Nodular bilateral tori was seen on the lingual side of the mandible, above mylohyoid line at the level of premolars. Excision of the tori was planned, to be used as autogenous bone graft in relation to 36.

Surgical technique

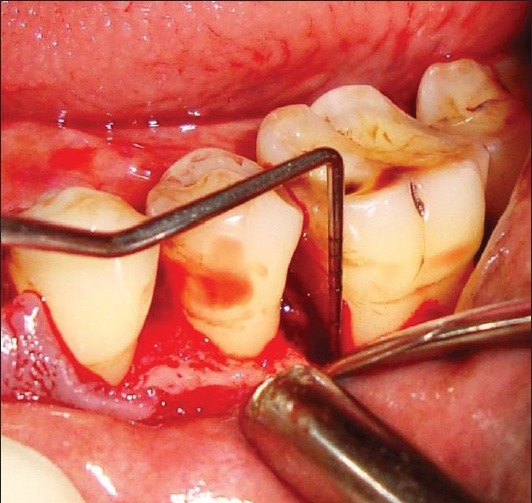

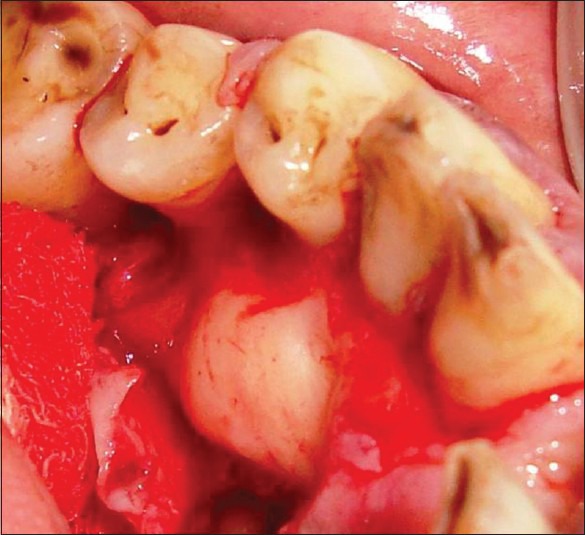

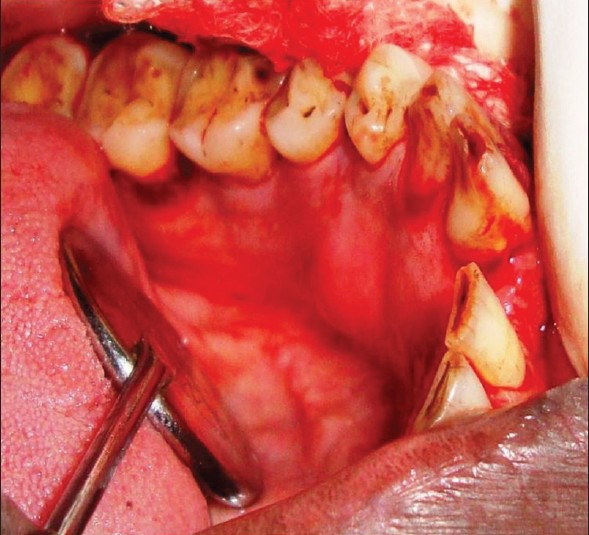

Conservative incisions were done to provide soft tissue cover over the graft material at the end of the procedure. The soft tissue cover prevents the material from being washed away. Full thickness flap reflection was done to expose the recipient area. A relatively thick flap was preferred over a thin flap to prevent tissue necrosis and possible washing away of the graft material. Full thickness flap was reflected on the lingual side to expose the mandibular tori which extended from distal aspect of the canine to the mesial aspect of second premolar [Figures 1–4].

Figure 1.

Pre-op probing

Figure 4.

Defect probing

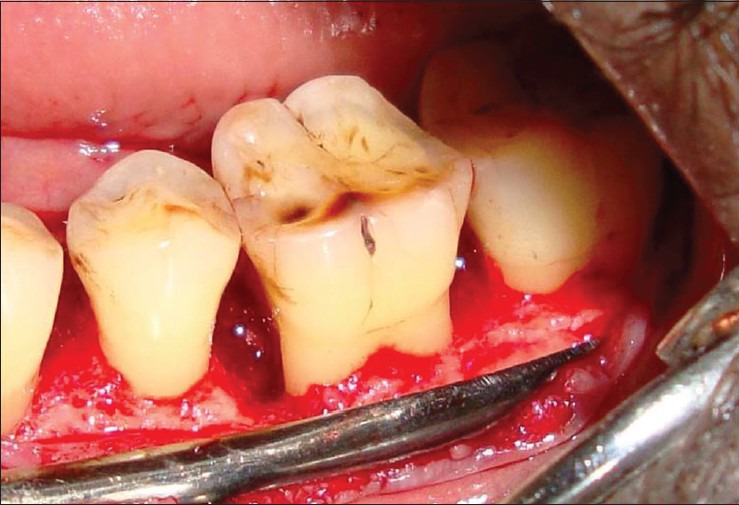

The defect between 35-36 and 36-37 were prepared by soft tissue debridement by using a combination of hand curettes and ultrasonic scalers. Root conditioning was done with tetracycline hydrochloride to decontaminate the root surface and increase the compatibility of the root surface with cell attachment. As the defect was lined by a cortical wall of bone, which can limit blood flow to the graft area, intra marrow penetrations were done using a micromotor hand piece with a round bur to encourage blood supply from the underlying cancellous bone, and provide graft with sufficient nutrients for survival.

The tori from the lingual side was excised with rotary instruments and chisel and mallet and placed in a sterile dappen dish with saline. The graft material was condensed in the defect area tightly. Care was taken for grafts not to be overfilled to avoid exposure due to soft tissue shortage [Figures 5–10]. The flap margins were coapted and sutured. Figures 11 and 12 show the radiograph of the bone defect taken before and after the placement of the graft and Figure 13 shows the radiograph of the bone fill in the defect area taken one year post-operatively. The long-cone paralleling technique was used to take all the radiographs. Note the bone fill between 35-36 and 36-37 were angular defects were present. Clinically the treated lesions were evaluated in terms of pocket depth and clinical attachment levels. Post-operative clinical measurements taken one year after the treatment revealed a significant reduction in probing pocket depth to 3 mm from 7 mm at baseline and reduction in loss of attachment to 2 mm from 5 mm at baseline. A previous pocket which does not probe after treatment and the bone fill seen in the radiograph indicates the success of the treatment.

Figure 5.

Lingual tori

Figure 10.

Post-op healing of the site of tori after one year

Figure 11.

Pre-op iopa x-ray showing the defect area

Figure 12.

Post-op iopa x-ray taken immediately after the placement of the graft

Figure 13.

Post-op iopa x-ray taken one year after the placement of graft

Figure 2.

Pre-op lingual

Figure 3.

Flap reflection

Figure 6.

Excised tori

Figure 7.

Defect fill

Figure 8.

Suturing

Figure 9.

Post-op probing after one year

Postoperative care

All efforts to minimize bacterial build-up in the grafted area were emphasized. This included 0.2% chlorhexidine rinses 2-3 times per day for 2-3 weeks. Systemic antibiotic and analgesics were given (amoxicillin 500 mg 3 times daily and aceclofenac 100 mg 2 times daily were prescribed).

Suture removal was done. After one week the patient was instructed to initiate oral hygiene in the area and was examined every 15 days for the next 3 months. During these examination, light debridement of the area was performed. No probing or vigorous scaling of the grafted area were performed for 3 months following surgery. Radiographs were taken at periodic intervals to assess regeneration.

DISCUSSION

Intraoral autogenous bone graft material are ideal for periodontal regeneration. The choice of autogenous donor site is markedly influenced by two important considerations namely, the quantity of bone required at the recipient site and the biologic qualities of the donor bone.[15] Additionally, successful augmentation of the recipient site is influenced by the technical, intraoperative surgical manipulations employed. The quantity of bone required is a major factor in donor site selection. The particular embryologic origin of donor bone is one of the important factors in the success of bone transplantation procedures. Intramembranous grafts tend to maintain their volume whereas endochondral grafts undergo variable degrees of resorption over variable periods of time.[16] The bones of the craniofacial complex with limited exception form via intramembranous ossification. The calvaria, maxillary bones, mandibular body and mandibular ramus in particular are intramembranous. The mandibular condyles are exceptions because they are of endochondral origin. Hence intramembranous rather than endochondral bone autograft is preferred in head and neck and intraoral applications. From the above discussion, the relative attractiveness of intraoral sites for the harvesting of donor bone can be appreciated.

The mandibular symphysis, which is an excellent donor site is almost invariably not contiguous with the area to be augmented. An alternative mandibular donor sites that are continuous with the recipient area and would eliminate the need for an extra surgical site are the tori and exostoses, which are common intraoral exophytic findings,[17] and are suitable alternative bone sources.

In this patient there was an angular defect between 35-36 and 36-37, which required bone grafting to be done. As bilateral mandibular tori were present on the lingual side above the mylohyoid line in relation to the premolars, we decided to remove the tori and use it as a source of autogenous bone grafts as autograft is considered the gold standard when compared to other sources of bone grafts. Moreover the volume of bone required was less, hence bone was taken from the lingual tori which were unnecessary bony extensions present on the mandible contiguous with the recipient area which obviated the need for an extra surgical site and also the volume would be well maintained as it is of intramembranous origin. In conclusion it can be said that whenever a patient has a mandibular tori and requires bone grafting procedures, utilization of these anatomic exostoses as donor sites should be considered.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hammack BL, Enneking WF. Comparative vascularization of autogenous and homogenous bone transplants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1960;42:811–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brugnami F, Caiazzo A, Leone C. Local intraoral autologous bone harvesting for dental implant treatment: Alternative sources and criteria of choice. Keio J Med. 2009;58:24–8. doi: 10.2302/kjm.58.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castro Reino O, Perez Galera J, Perez Cosio Martin J, Urbon Caballero J. Surgery of palatal and mandibular torus. (53-6).Rev Actual Odontoestomatol Esp. 1990;50:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pynn BR, Kurys-Kos NS, Walker DA, Mayhall JT. Tori mandibularis: A case report and review of the literature. (1063-6).J Can Dent Assoc. 1995;61:1057–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki M, Sakai T. A familial study of torus palatinus and torus mandibularis. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1960;18:263–72. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eggen S, Natvig B. Relationship between torus mandibularis and number of teeth present. Scand J Dent Res. 1986;94:233–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1986.tb01758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerdpon D, Sirirungrojying S. A clinical study of oral tori in southern Thailand: Prevalence and the relation to parafunctional activity. Eur J Oral Sci. 1999;107:9–13. doi: 10.1046/j.0909-8836.1999.eos107103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonnier KE, Horning GM, Cohen ME. Palatal tubercles, palatal tori and mandibular tori: Prevalence and anatomical features in a U.S. population. J Periodontol. 1999;70:329–36. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruce I, Ndanu TA, Addo ME. Epidemiological aspects of oral tori in a Ghanaian community. Int Dent J. 2004;54:78–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haugen LK. Palatine and mandibular tori.A morphologic study in the current Norwegian population. Acta Odontol Scand. 1992;50:65–77. doi: 10.3109/00016359209012748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reichart PA, Neuhaus F, Sookasem M. Prevalence of torus palatinus and torus mandibularis in Germans and Thai. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;16:61–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1988.tb00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Bayty HF, Murti PR, Matthews R, Gupta PC. An epidemiological study of tori among 667 dental outpatients in Trinidad and Tobago, West Indies. Int Dent J. 2001;51:300–4. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2001.tb00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jainkittivong A, Robert P. Langlais, San Antonio.Buccal and palatal exostoses: Prevalence and concurrence with Tori. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:48–53. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.105905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hull M. Life-threatening swelling after mandibular vestibuloplasty. J Oral Surg. 1977;35:511–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ten Cate AR., editor. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1994. Oral Histology: Development, Structure, and Function; pp. 389–431. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith JD, Abramson M. Membranous vs endochondral bone autografts. Arch Otolaryngol. 1974;99:203–5. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1974.00780030211011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buser D, Dula K, Belser UC, Hirt HP, Berthold H. Localized ridge augmentation using guided bone regeneration. 1. Surgical procedure in the maxilla. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1993;13:29–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]