Abstract

Despite the increasing ACT teams in Japan, no research exists on the need of ACT within the Japanese mental health system. The aim of this study was to describe the needs and feasibility of ACT teams. Furthermore, we estimated the number of po-tential ACT users and ACT teams needed in Japan. This study consists of two cross-sectional surveys in Sendai city. The primary survey was a self-completed questionnaire on the need and feasibility of ACT. In the secondary survey, the number of patients eligible for ACT was estimated based on primary physicians’ evaluations. In the primary survey, 17 of the 57 in-stitutions responded (response rate 29.8%). All respondents answered that ACT teams are needed in the city of Sendai and “Crisis response” was as the most needed role of ACT. Based on the results of the secondary survey, approximately 900 to 3,600 patients in Sendai are estimated to be eligible for ACT. This finding indicates that the estimated number of ACT teams needed for 100,000 populations is from 0.9 to 3.5 in Japan, a result that is in general agreement with data from other coun-tries.

Keywords: Assertive community treatment, community psychiatry, Japan, needs, population, schizophrenia.

INTRODUCTION

ACT (Assertive Community Treatment) is a community mental health care program developed in the United States around 1970 [1-3]. The program is considered one of the densest and most comprehensive models of care management to support community living for people with mental disorders. Each team member makes use of his or her professional expertise while providing basic daily living support and a series of care practices, including relationship-building, assessment, care planning, monitoring, and evaluation. Currently, ACT programs have been introduced and implemented in many countries worldwide [4-7]. Numerous studies have shown ACT to be effective in reducing hospitalization duration, stabilizing residential circumstances, and improving client satisfaction with services. Among non-drug therapy psychiatric treatment programs, ACT had the clearest scientific evidence [8-1].

In 2003, the first experimental adoption of ACT was initiated in Chiba, Japan. The series of studies showed that ACT had a positive influence, as evidenced by a reduction of in-patient days, lower depressive symptoms, higher client satisfaction, and reduction of families’ anxieties toward the future [12-15]. Assertive Community Treatment practices are implemented in more than 20 locations nationwide, including Kyoto, Okayama, Shizuoka, and Ibaraki, and movements to develop programs are seen in all parts of the country. Moreover, conferences have been held since 2005among ACT practitioners nationwide, and various types of training workshops are held annually.

Despite the increasing ACT teams in Japan, no research exists on the need of ACT within the Japanese mental health system. The aim of this study was to describe the needs and feasibility of ACT teams. Furthermore, we estimated the number of potential ACT users and ACT teams needed in Japan.

METHODS

Setting

This study consists of two cross-sectional surveys in Sendai city, which is the capital of Miyagi prefecture. Sendai has a population of one million, located 300 km north from Tokyo, and neighbor to suburbs such as Natori city, which has a population of 70 thousand.

The primary survey was a self-completed questionnaire on the need and feasibility of ACT. Subjects were psychiatric hospital directors (in the case of general hospitals, the head of the psychiatry department) and psychiatric clinic directors (clinic directors) located within the city of Sendai and surrounding areas. The primary survey confirmed whether respondents would cooperate in secondary and subsequent surveys. In the secondary survey, the number of patients eligible for ACT was estimated based on primary physicians’ evaluations.

Primary Survey

The researcher selected 17 inpatient institutions including the 14 institutions in the “Sendai Survey,” a survey of all psychiatric inpatient hospitals in the city of Sendai reported in 2005, and three psychiatric inpatient institutions belonging to municipalities neighboring Sendai.

Thirty-four outpatient only psychiatric institutions were surveyed, including all 32 institutions located within the city listed as member institutions on the Miyagi Prefecture Psychiatric Clinic Association website as of the end of December 2007 and two psychiatric clinics in neighboring municipalities. The list of outpatient medical facilities published in the 2007 Sendai Mental Health and Welfare Guidebook was checked to find clinics or general hospital psychiatry departments without inpatient beds within the city that were not members of the Miyagi Prefecture Psychiatric Clinic Association. Five clinics and one institution that provided outpatient care to mainly adults with mental disorders in a government facility were added, for a total of 40 institutions. Requests for cooperation in the survey, self-completed questionnaire forms, explanations of ACT, and other relevant materials were sent to a total of 57 institutions on January 24, 2008 and returned materials were to be postmarked by February 1, 2008.

Secondary Survey

The inpatient survey reference date was February 1, 2008. The number of patients that would be covered by ACT was ascertained from primary physicians’ inpatient evaluations. In the five psychiatric hospitals that consented to the request for this survey (four in Sendai and one in Natori which is suburb of Sendai), there were 852 inpatients in the psychiatric wards, of whom 509 patients resided in the city of Sendai. Consent was obtained from 423 of these 509 patients.

The outpatient survey reference date was February 22, 2008. Survey forms were sent to general hospital psychiatry departments, single department psychiatric hospitals, and psychiatric clinics within the city of Sendai that, in the primary survey, had expressed intention to cooperate further. The number of patients eligible for ACT was ascertained from primary physicians’ evaluations of outpatients who visited the hospital or clinic on the survey date. 945 patients underwent psychiatric outpatient examinations on the day of the survey; consent for the survey was obtained from 779 patients.

Collected Data

In the primary survey, collected data included the need for ACT, necessary roles for ACT, plan to establish an ACT team, and financial profitability of ATC. In the secondary survey, collected data included each client’s basic characteristics and variables related ACT eligibility such as diagnosis, severity of disability, and psychiatric symptoms.

Disability was assessed as a single item scored on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating a more severe disability (1: Mental disorder is seen, but patient can function normally in daily life and life in the community; 2: Mental disorder is seen, and patient has certain restrictions in daily life or life in the community; 3: Mental disorder is seen, and patient has marked restrictions in daily life or life in the community, and assistance is needed at certain times; 4: Mental disorder is seen, patient has marked restrictions in daily life or life in the community, and constant assistance is needed; 5: Mental disorder is seen, and patient is almost fully unable to care for him or herself).

Symptoms were assessed as a single item scored on a 6-point Likert, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms (1: No symptoms; 2: Psychiatric symptoms are seen, but are stable; 3: Several deficits are seen in communication and recognition; 4: Behavior is substantially affected by hallucinations or delusions; 5: There is a gross deficit in communication and constant attention is needed; 6: Marked deviant behaviors seen).

To estimate the number of potential ACT users in Japan, we used the data from government statistics, including the hospital survey by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare [16] and Census by the statistics bureau of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications [17].

Estimate of the Number of ACT-Eligible Clients

In addition to descriptive analyses, we estimated the number of potential ACT users in Japan based on the number of eligible clients for ACT in this survey. Eligibility for ACT was assessed using the screening criteria based on the inclusion criteria of the ACT-J team, which was established in the first adoption study of ACT in Japan [12].

The screening criteria of this study were as follows:

Residence: Sendai city

Age: 18-59 years old

Primary diagnosis: F2 (schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders), F3 (mood disorders), and other mental disorders, as defined by the ICD-10 [18] (excluding primary diagnosis of intellectual impairment, dementia, drug or alcohol abuse, and personality disorder)

Substantial psychiatric service use in the past 2 years (two or more hospitalizations, 100 or more in-patient days, three or more psychiatric emergency department visits, or 3 months or more of no-show to out-patient clinic appointments)

Low level of social functioning when at best in the previous year, defined as a disability evaluation of 4 points or higher.

Based on these evaluations, we supposed three levels of criteria from criteria 1 to 3 described below:

Criteria 1: Included those diagnosed as F2 or F3 if the patient met the criteria for either (iv) OR (v).

Criteria 2: Included those diagnosed as F2 if the patient met the criteria for either (iv) OR (v) and those diagnosed as F3 were included if clients met criteria for both (iv) AND (v).

Criteria 3: Included those diagnosed as F2 or F3 if the patient met the criteria for either (iv) AND (v).

RESULTS

In the primary survey, 17 of the 57 institutions responded (response rate 29.8%). The questions and response percentage distribution are shown in Table 1. All respondents answered that ACT teams are needed in the city of Sendai and

Table 1.

Needs, attitudes, and plan regarding ACT adoption.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Do you feel that ACT teams are needed in the city of Sendai? | 35.3% | |

| Strongly feel the need | 6 | 64.7% |

| Somewhat strongly feel the need | 11 | 0.0% |

| Cannot say | 0 | 0.0% |

| Do not feel much need | 0 | 0.0% |

| Feel no need | 0 | 0.0% |

| No response | 0 | 0.0% |

| Total | 17 | 100.0% |

| What kind of roles d you thick would be necessary for ACT? | ||

| Facilitate hospital discharge | 8 | 10.3% |

| Crisis response | 14 | 17.9% |

| Child and adolescent measures | 7 | 9.0% |

| Job assistance | 6 | 7.7% |

| Measures for psychiatric patients with criminal records | 6 | 7.7% |

| Early intervention | 10 | 12.8% |

| Hikikomori (social withdrawal) measures | 10 | 12.8% |

| Alcohol and drug dependence measures | 6 | 7.7% |

| Measures for personality disorders | 8 | 10.3% |

| Other | 3 | 3.8% |

| No response | 0 | 0.0% |

| Total | 78 | 100.0% |

| Are you considering establishing an ACT team at your hospital? | ||

| Currently considering it is concrete terms and moving forward with preparations | 1 | 5.9% |

| Would like to consider it when we have a better understanding of the procedures | 2 | 11.8% |

| Not currently considering it | 14 | 82.4% |

| No response | 0 | 0.0% |

| Total | 17 | 100.0% |

| Would you consider establishing an ACT team if the medical insurance system were revised so that such work would be profitable? | ||

| Yes | 4 | 23.5% |

| No | 9 | 52.9% |

| No response | 4 | 23.5% |

| Total | 17 | 100.0% |

| Would you consider establishing an ACT team if a subsidy were available? | ||

| Yes | 2 | 11.8% |

| No | 10 | 58.8% |

| No response | 5 | 29.4% |

| Total | 17 | 100.0% |

multiple answers allowed

“Crisis response” was as the most needed role of ACT. On the other hand, 82.4% of respondents were not considering establishing an ACT team at their hospitals.

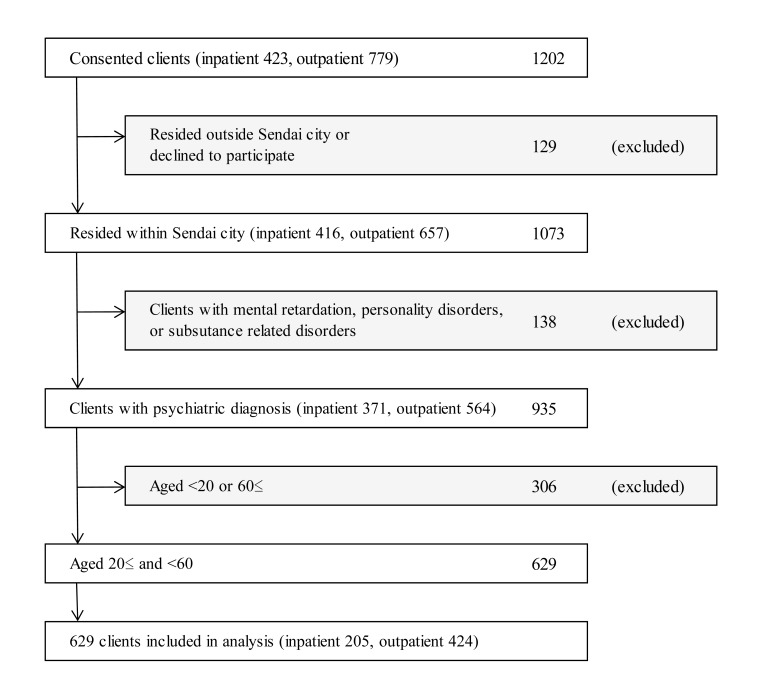

In the secondary survey, of the 1202 clients who consent to participate the study, 129 (Resided outside Sendai city), 138 (Clients with mental retardation, personality disorders, or substance related disorders), and 306 (Aged less than 20 or over 60) were excluded from the analysis (see Fig. 1). The distribution of sex, diagnosis, psychiatric service use, ability, symptoms, and ACT eligibility for each inpatient and outpatient are shown in Table 2.

Fig. (1).

Flow of clients included in analysis of secondary survey.

Table 2.

ACT eligibility of inpatient and outpatient clients.

| Inpatients (N=205) | Outpatients (N=424) | Total (N=629) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 105 | 51.2% | 210 | 49.5% | 315 | 50.1% |

| Female | 100 | 48.8% | 212 | 50.0% | 312 | 49.6% |

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.5% | 2 | 0.3% |

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| F0 (organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders) | 6 | 2.9% | 4 | 0.9% | 10 | 1.6% |

| F2 (schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders) | 163 | 79.5% | 193 | 45.5% | 356 | 56.6% |

| F3 (mood disorders) | 27 | 13.2% | 137 | 32.3% | 164 | 26.1% |

| F4 (neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders) | 8 | 3.9% | 73 | 17.2% | 81 | 12.9% |

| F5 (physiological disorders, disorders associated with physical factors) | 1 | 0.5% | 17 | 4.0% | 18 | 2.9% |

| Hospitalized 2 or more times in the past 2 years | 56 | 27.3% | 25 | 5.9% | 81 | 12.9% |

| 100 or more days of hospitalization in the past 2 years | 183 | 89.3% | 33 | 7.8% | 216 | 34.3% |

| 3 or more emergencies uses | 11 | 5.4% | 2 | 0.5% | 13 | 2.1% |

| 3 months or more of no-show to out-patient clinic appointments | 26 | 12.7% | 9 | 2.1% | 35 | 5.6% |

| Ability | ||||||

| 1: Client can function normally in daily life in the community | 20 | 9.8% | 131 | 30.9% | 151 | 24.0% |

| 2: Client has certain restrictions in daily life in the community | 40 | 19.5% | 153 | 36.1% | 193 | 30.7% |

| 3: Client has marked restrictions and assistance is needed at certain times | 73 | 35.6% | 113 | 26.7% | 186 | 29.6% |

| 4: Client has marked restrictions and constant assistance is needed | 59 | 28.8% | 25 | 5.9% | 84 | 13.4% |

| 5: Client is almost fully unable to care for him- or herself | 12 | 5.9% | 2 | 0.5% | 14 | 2.2% |

| Symptom | ||||||

| 1: No symptoms. | 17 | 8.3% | 127 | 30.0% | 144 | 22.9% |

| 2: Psychiatric symptoms are seen, but they are stable | 39 | 19.0% | 133 | 31.4% | 172 | 27.3% |

| 3: Several deficits are seen in communication and recognition | 45 | 22.0% | 110 | 25.9% | 155 | 24.6% |

| 4: Behavior is substantially affected by hallucinations or delusions | 60 | 29.3% | 41 | 9.7% | 101 | 16.1% |

| 5: There is a gross deficit in communication and constant attention are needed | 39 | 19.0% | 12 | 2.8% | 51 | 8.1% |

| 6: Marked deviant behavior (suicidal ideation, violent behavior) is seen | 2 | 1.0% | 1 | 0.2% | 3 | 0.5% |

| ACT eligibility | ||||||

| Eligible for criteria 1 | 175 | 85.4% | 83 | 19.6% | 258 | 41.0% |

| Eligible for criteria 2 | 161 | 78.5% | 67 | 15.8% | 228 | 36.2% |

| Eligible for criteria 3 | 99 | 48.3% | 10 | 2.4% | 109 | 17.3% |

Estimate of the Number of ACT-Eligible Patients

According to the 2012 hospital survey by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare [16], the number of psychiatric inpatients per 100,000 people in Miyagi prefecture was 234.7. Here, using the population of Sendai and Natori (1,098,232 people), the number of psychiatric inpatients in these cities was estimated to be 2577.6. The number of psychiatric inpatients as of the survey reference date at the five institutions in this study was 416, which is equivalent to 16.1% of the total number of psychiatric inpatients in the entire city. Hence, assuming that this survey is representative, the number of psychiatric inpatients eligible for ACT in Sendai was approximately 1084.9, 998.1, and, 613.8 for Criteria 1, 2, and, 3 respectively (see C in Table 3).

Table 3.

Estimate of number of ACT-eligible patients and ACT teams.

| Criteria 1 | Criteria 2 | Criteria 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | Total population in Sendai as of 2010 = 1,025,098 | |||

| A | The number of eligible inpatient clients in this survey | 175 | 161 | 99 |

| B | The number of eligible outpatient clients in this survey | 83 | 67 | 10 |

| C | Estimated number of eligible inpatient clients in Sendai [A / 0.1613] | 1084.9 | 998.1 | 613.8 |

| D | Estimated number of eligible outpatient clients in Sendai [(B / 0.459 ) * 14] | 2531.6 | 2043.6 | 305.0 |

| E | Estimated number of eligible clients in Sendai [C + D] | 3616.5 | 3041.7 | 918.8 |

| F | Estimated number of eligible clients for 100,000 population [(E / P) *100,000] | 352.8 | 296.7 | 89.6 |

| G | Estimated number of ACT team needed for 100,000 population [F / 100] | 3.5 | 3.0 | 0.9 |

According to the Survey of Medical Care Activities in Public Health Insurance (Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare), the number of cases in which medical treatment of outpatient psychiatric therapy (first visit), outpatient psychiatric therapy 2 (hospital), and outpatient psychiatric therapy 2 (clinic) was done in the single month of August 2006 was 4,216,910 [16]. This findings is a summation of medical acts in all of Japan. Using the populations of the city of Sendai and all of Japan, cases in which psychiatric outpatient care was given for patients residing in Sendai can be estimated as 34,329.2 per month. Assuming that this outpatient treatment was over 24 weekdays, the number of psychiatric outpatient visits per day would be about 1,430. The number of outpatients included in this study was 657; therefore, this study was equivalent to 45.9% of the total number of psychiatric outpatients care in all Sendai. Moreover, the total number of outpatients in Sendai would be 14 times more than the those in this study because the average interval of psychiatric outpatient care in Japan is 14.0 days [19]. Accordingly, the number of psychiatric outpatients eligible for ACT in Sendai would be approximately 2531.6, 2043.6, and, 305.0 for Criteria 1, 2, and, 3 respectively (see D in Table 3).

Therefore, the estimated numbers of eligible clients in Sendai were 3616.5, 3041.7, and, 918.8 respectively. Assuming that one ACT team provides services for 100 clients, the estimated number of ACT teams needed for 100,000 population are 3.5, 3.0, and, 0.9 for Criteria 1, 2, and, 3 respectively (see F and G in Table 3).

DISCUSSIONS

All medical institutions that responded answered “Strongly feel the need” or “Somewhat strongly feel the need” for ACT. The opinion was that it is necessary to prevent clinic visits and medication discontinuation of people with

severe mental disorders and help them live in society. Regarding the desires of ACT activities within the city of Sendai, many respondents looked forward to “emergency measures,” “early intervention,” and “hikikomori (social withdrawal) measures.” One institution responded, “We are currently considering it in concrete terms and moving forward with preparations.” Two others responded, “We would like to consider it when we have a better understanding of the procedures.”

Medical institutions that were not currently considering introducing ACT accounted for the remaining 80%. There will probably be more room to consider implementation of ACT when the economic foundation has been developed, which will include revising the medical care insurance payments to obtain profitability; however, currently the image seems to be of difficulty in terms of manpower and 24-hour handling. Thus, many institutions view it as impossible at present.

Together with greater dissemination and education of ACT, its introduction should be considered through the functional differentiation of psychiatric institutions.

When screening was done using the ACT enrollment criteria for the 423 psychiatric hospital inpatients who lived in Sendai and consented, 99 to 175 were eligible. Using the same enrollment criteria for the 657 psychiatric outpatients who lived in Sendai, 10 to 83 were eligible. Based on these figures, approximately 900 to 3,600 patients in Sendai are estimated to be eligible for ACT. This finding indicates that the estimated number of ACT teams needed for 100,000 population is from 0.9 to 3.5, a result that is in general agreement with data from other countries [20, 21]. More than 15% of clients were excluded because of place of residence, as medical care use is not sectorized based on a place of residence in the Japanese health care insurance system (anyone can access medical care from anyplace). It is not rare that clients use hospitals or clinics in neighboring cities because of convenience or sometimes because they fear being stigmatized.

Using the criteria of this study, all clients with severe symptoms or disabilities were included. It is possible to say that extremely severe cases, such as clients with symptom scores of 6 or disability scores of 5 cannot maintain living in community even with support from an ACT team. If these severe cases were excluded from the data of this study, the estimated number of eligible clients for 100,000 population would be from 68.7 to 320.7, which is 2% less than original estimates.

The difference of reference date of data collection was a limitation of this study. The reference date was February 1, 2008 for the inpatient survey and February 22, 2008 for the outpatient survey. Moreover, the reference dates of the government statistics varied from 2010 to 2012. However, this limitation would not affect the general findings of this study because the variables we used had not drastically changed in the past few years. Also, low response rate of the primary survey and no data for non-response analysis was another limitation. The possible reason of the low response rate would be that lots of hospitals were not interested in outreach services such as ACT in the situation of mental health systems in Japan where the psychiatric rehabilitation has not been deinstitutionalized. Therefore, the respondents would have been biased toward those who had positive attitude about ACT adoption.

Traditional ACT is designed to serve only a small portion of the population, and other programs are needed to ensure a comprehensive system of community care. Other types of ACT and case management programs that provide direct services and coordination of services are necessary for the broader population of individuals with mental illness [22]. In future research, the estimates should include other diverse aspects of the community mental health system and social resources.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was part of a project supported by grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (2007 Implementation projects of health and welfare related services for persons with disabilities H19-39). The authors declare no competing interests. MN planned the research, acquired data, analyzed data, and managed the research project. TS analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stein LI, Test MA. Alternative to mental hospital treatment. I.; Conceptual odeltreatment program, and clinical evaluation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980; 37(4):392–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780170034003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weisbrod BA, Test MA, Stein LI. Alternative to mental hospital treatment. II.; Economic benefit-cost analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37(4):400–5. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780170042004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Test MA, Stein LI. Alternative to mental hospital treatment.III. Social cost. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37(4):409–12. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780170051005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Test MA, Stein LI. Practical guidelines for the community treatment of markedly impaired patients. Community Ment Health J. 1976;12(1):72–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01435740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGrew JH, Bond GR. Critical ingredients of assertive community treatment judgments of the experts. J Ment Health Adm. 1995;22(2):113–25. doi: 10.1007/BF02518752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns T, Fioritti A, Holloway F, Malm U, Rossler W. Case management and assertive community treatment in Europe. Psych Serv. 2001;52(5):631–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.5.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordén T, Eriksson A, Kjellgren A, Norlander T. Involving clients and their relatives and friends in psychiatric care Case managers' experiences of training in resource group assertive community treatment. PsyCh J. 2012;1(1):15–27. doi: 10.1002/pchj.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueser KT, Torrey WC, Lynde D, Singer P, Drake RE. Implementing evidence-based practices for people with severe mental illness. Behav Modif. 2003;27(3):387–411. doi: 10.1177/0145445503027003007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olfson M. Assertive community treatment an evaluation of the experimental evidence. Hosp Community Psych. 1990;41(6):634–41. doi: 10.1176/ps.41.6.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziguras SJ, Stuart GW. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mental health case management over 20 years. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(11):1410–21. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.11.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norden T, Malm U, Norlander T. Resource Group Assertive Community Treatment (RACT) as a Tool of Empowerment for Clients with Severe Mental Illness A Meta-Analysis. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2012;8:144–51. doi: 10.2174/1745017901208010144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito J, Oshima I, Nishio M , et al. The effect of Assertive Community Treatment in Japan. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2011;123 (5):398–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horiuchi K, Nisihio M, Oshima I, Ito J, Matsuoka H, Tsukada K. The quality of life among persons with severe mental illness enrolled in an assertive community treatment program in Japan 1-year follow-up and analyses. Clin Pract Epidemol Ment Health. 2006;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishio M, Ito J, Oshima I , et al. Preliminary outcome study on assertive community treatment in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;66(5):383–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2012.02348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sono T, Oshima I, Ito J , et al. Family support in assertive community treatment an analysis of client outcomes. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48(4):463–70. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9444-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Survey of Medical Institutions, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Tokyo Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2012. Available from http: //www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/79-1a.html.

- 17.Census by the statistics bureau of Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications 2010. Available from http //www.stat.go.jp/data/kokusei/2010/.

- 18.The International Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems Tenth Revision. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 19.The patient survey, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare 2011. Available from http: //www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/kanja/11/. [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Leer G, Musgrave I, Somers J, Samra J, Querée M. British Columbia Program Standards for assertive community treatment (ACT) teams British Columbia Ministry of Health Services Mental Health and Addictions. 2008 Available from http: //www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2008/BC_Standards_for_ACT_Teams.pdf.

- 21.Williams N, Hradek B. Getting our ACT Together Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) for the Seriously Mentally Ill in Iowa Technical Assistance Center for Assertive Community Treatment 2010. Available from http: //www.healthcare.uiowa.edu/icmh/act/.

- 22.Ito J, Oshima I, Nishio M, Kuno E. Initiative to build a community-based mental health system including Assertive Community Treatment for people with severe mental illness in Japan. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. 2009;12:247–60. [Google Scholar]