Abstract

The most common models of sequence evolution used to make inferences about adaptation rely on the assumption that selective pressures at a site remain constant through time. Instead, one might plausibly imagine that a change in the environment renders an allele beneficial and that when it fixes, the site is now constrained – until another change in the environment occurs that affects the selective pressures at that site. With this view in mind, we introduce a simple dynamic model for the evolution of coding regions, in which non-synonymous sites alternate between being fixed for the favored allele and being neutral with respect to other alleles. We use the pruning algorithm to derive closed forms for observable patterns of polymorphism and divergence in terms of the model parameters. Using our model, estimates of the fraction of beneficial substitutions α would remain similar to those obtained from existing approaches. In this framework, however, it becomes natural to ask how often adaptive substitutions originate from previously constrained or previously neutral sites, i.e., about the source of adaptive substitutions. We show that counts of coding sites that are both polymorphic in a sample from one species and divergent between two others carry information about this parameter. We also extend the basic model to include the effects of weakly deleterious mutations and discuss the importance of assumptions about the distribution of deleterious mutations among constrained non-synonymous sites. Finally, we derive a likelihood function for the parameters and apply it to a toy example, variation data for coding regions from chromosome 2 of the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup. This modeling work underscores how restrictive assumptions about adaptation have been to date, and how further work in this area will help to reveal unexplored and yet basic characteristics of adaptation.

Keywords: McDonald-Kreitman test, MKprf, Drosophila, selection, polymorphism, divergence

1. Introduction

A central goal of evolutionary genetics is to understand the dynamics of natural selection. Since patterns of genetic variation data within and between species carry information about these dynamics, a widely used approach has been to infer selection parameters (such as the strength or rate of adaptation) from polymorphism and divergence. This approach requires the development of models that capture the essential features of natural selection and can serve as a foundation for inference. Naturally, this endeavor is shaped by the available data. In this respect, the field had changed dramatically: whereas until now we had single genomes from many taxa and much more limited polymorphism data, we are starting to have large genome-wide polymorphism data in many species (e.g., Durbin et al. 2010; Liti et al. 2009). This deluge of data presents an unprecedented opportunity to learn about the dynamics of natural selection, but naturally raises questions about how best to take advantage of the information - in particular, what new insights could be gained from looking at polymorphism and divergence data from multiple species jointly and how to construct useful models.

To date, researchers have taken one of two main modeling approaches. The first is based on Markov models that describe changes to a single sequence, representing substitutions, without relying on an explicit model for the population genetics. This approach has been widely employed in the analysis of DNA and amino acid sequences from multiple species in order to estimate the rate of evolution and species divergence times, reconstruct ancestral sequences, as well as for many other applications (Li and Graur 1990; Whelan et al. 2001; Yang 1997), with the models tweaked in myriad ways in order to incorporate different mutation processes and the effects of variation in selective pressures. For protein-coding regions, these models often describe the effects of natural selection in terms of the non-synonymous (replacement) to synonymous (silent) substitution ratio ω = dn/ds (Goldman and Yang 1994; Muse and Gaut 1994), allowing this measure to vary among codons (e.g., Yang et al. 2000). A ratio of ω > 1 is interpreted as indicating that positive directional selection has occurred; in turn, ω < 1 is interpreted as reflecting negative or purifying selection on amino acid mutations. As a test for positive selection, however, these approaches are underpowered, because many codons with ω < 1 might in fact experience a mixture of positive and negative selection, and even a single codon with ω < 1 might intermittently experience the two.

Joint consideration of divergence and polymorphism data helps to overcome this limitation. Notably, McDonald and Kreitman introduced a statistical test of the neutral hypothesis, intended to detect positive selection in proteins (McDonald and Kreitman 1991). The test consists in comparing the number of synonymous and non-synonymous changes between and within species, and is based on two simplifying assumptions: that synonymous mutations are selectively neutral and that non-synonymous mutations can be either neutral, strongly deleterious, or strongly advantageous (McDonald and Kreitman 1991; Smith and Eyre-Walker 2002). The underlying idea is that neutral mutations can fix by chance in one of the lineages, resulting in divergence with respect to another species, and may also be present at intermediate frequencies within a species, resulting in polymorphism. In contrast, strongly deleterious mutations are not expected to reach substantial frequencies, let alone fix in a population, and hence should contribute negligibly to polymorphism and not at all to divergence. Finally, strongly advantageous mutations may fix in one lineage, resulting in divergence, but their rarity and the fact that, once they reach a substantial number of copies, they rapidly fix in the population, implies that they will rarely be sampled as polymorphisms. Thus, assuming that all the divergence is neutral (and the two species under consideration are close enough to ignore multiple hits), the ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous divergence, Dn/Ds, should equal the ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous polymorphism, Pn/Ps. In turn, if Dn includes both adaptive substitutions, a, and neutral substitutions, we expect that (Dn − a)/Ds = Pn/Ps, or equivalently that a = Dn − DsPn/Ps. (For brevity, we describe this approach treating observed values and expectations interchangeably). Under these assumptions, the fraction of amino acid substitutions that are adaptive can be estimated as α = a/Dn = 1 − DsPn/ DnPs (Smith and Eyre-Walker 2002). While this approach has yielded important insights, its lack of an underlying dynamic model limits its application to data from two species, and does not allow one to answer questions regarding intermittent changes in the selective pressures.

Extensions of the McDonald-Kreitman approach incorporate explicit models for the population dynamic of mutant alleles at a site (e.g., Bustamante et al. 2002; Wilson et al. 2011). When using the allelic frequency spectrum as well as divergence levels, some implementations further account for a distribution of selection coefficients and for recent demographic history (e.g., Boyko et al. 2008; Keightley and Eyre-Walker 2007). To the best of our knowledge, however, all these approaches rely on the Poisson Random Field (PRF), which models newly arising alleles as drawn from a stationary distribution of selection coefficients (Sawyer and Hartl 1992). (Similar assumptions are also implicit in models based on the first approach (Nielsen and Yang 2003).) While this modeling choice makes many calculations more tractable, it relies on a highly specific assumption about beneficial substitutions (Gillespie 1994), namely that once a beneficial substitution of an allele occurs, the allele immediately becomes deleterious relative to the next beneficial allele to fix at the same site (see Nielsen and Yang 2003).

Instead, one might plausibly imagine that a change in the environment renders an allele beneficial and that when it fixes, the site is now constrained - until another change in the environment occurs that affects the selective pressures at that site. In particular, non-synonymous changes at a site can alternate between being neutral, deleterious or beneficial depending on changes in the environment. Under this view, it is natural to ask how often a beneficial mutation arises at a site that was previously constrained versus neutral (i.e., unconstrained) (see also Bazykin and Kondrashov 2011). The answer to this question is fundamental to our understanding of molecular adaptation, and can also inform us about what signatures adaptive substitutions are expected to leave in polymorphism data (Pennings and Hermisson 2006; Przeworski et al. 2005).

Here, we explore some implications of this alternative view. We formulate a dynamic evolutionary model in which non-synonymous sites alternate between being fixed for the favored allele (and thus constrained) and being neutral with respect to other alleles, and experience beneficial substitutions or a relaxation of constraint following a change in the environment. The model describes substitutions along a phylogeny as well as the state of a site at a given time (i.e., whether it is constrained or not). Using this model, we show that the source of adaptive substitutions (i.e., whether they occur at previously constrained or unconstrained sites) could in principle be inferred from the proportion of sites that are divergent between two species and polymorphic in another – an aspect of the data not used by current approaches. We note that while population genetic models of fluctuating selection have been studied in some depth (e.g., Gillespie 1991; Huerta-Sanchez et al. 2008; Takahata et al. 1975), they have focused on the effects of rapid changes in selection pressures on the trajectory of alleles in a population and thus on patterns of polymorphism, rather than on much slower changes that affect substitution patterns or on the joint patterns of polymorphism and divergence on a phylogeny, as we do here.

2. Theory

2.1. The Model

We model sequence evolution as a continuous-time Markov process (Taylor and Karlin 1994), where we assume that each site evolves independently (cf. Li and Graur 1990). Because the probability of observing polymorphism at a site depends on the selective effect of possible mutations, we want the state of a site in the model to include this information as well. We therefore extend the conventional classification of sites in coding regions as either completely synonymous – where all possible mutations do not change the translated amino acid – or completely non-synonymous (Li and Graur 1990), and we assume for simplicity that each non-synonymous site is either completely unconstrained or completely constrained. At a (completely-) unconstrained site, none of the possible mutations change the fitness of the organism, whereas at a constrained site, there is only one favored nucleotide and every mutation from this nucleotide has a strong deleterious effect (we will revisit this assumption later). The state of a site is thus defined by its type (synonymous, unconstrained or constrained) and its fixed nucleotide (A, C, T or G). We denote the fraction of unconstrained sites, out of all the non-synonymous sites, by f (which, under these assumptions, accords with the notation of Smith and Eyre-Walker (Smith and Eyre-Walker 2002)). Table 1 presents a summary of the notation.

Table 1.

Summary of notation.

| f | The fraction of unconstrained non-synonymous sites |

| S | The probability that a neutral site segregates in our sample |

| μ | The neutral fixation (and mutation) rate per site |

| ν | The rate of adaptation at non-synonymous sites |

| g | The fraction of adaptations that are unconstrained |

| νu, νc | The rate of unconstrained and constrained adaptations |

| ξ | The rate of relaxation at constrained non-synonymous sites |

| α | The fraction of non-synonymous substitutions that are beneficial |

| pn, Pn | The probability that a non-synonymous site is polymorphic and the number of non-synonymous polymorphic sites |

| dn, Dn | The probability that a non-synonymous sites is divergent and the number of nonsynonymous divergent sites |

| bn, Bn | The probability that a non-synonymous is both polymorphic and divergent and the number of such sites |

| Sc | The probability that a constrained non-synonymous site segregates in our sample |

| δ | Sc/S |

As will be justified later, we assume that the fixed nucleotide in a constrained site is the unique favored one, so there is no need to further classify the constrained type. Moreover, since we assume equal mutation and substitution rates among nucleotides, we do not care about the specific nucleotide in a site, only whether it changed in a lineage or not. Thus, it suffices to identify it as either A or not-A, that is, to denote either one of the three other options – C, T or G – by Ã. Two “not-A sites” are therefore expected to differ in their fixed nucleotide in two thirds of the cases.

The dynamics at synonymous and non-synonymous sites are treated as two separate Markov processes, with state spaces {sA,sÃ} and {uA,uÃ,cA,cÃ}respectively. Here sA stands for `synonymous, A fixed', sà for `synonymous, not-A fixed', and the non-synonymous types – unconstrained and constrained – are defined similarly.

To define the transition rules, we consider the possible events that each type of site might undergo. We begin with synonymous sites (see Figure 1A), where mutations reach neutral fixation (through genetic drift) with an average rate μ, equal to the mutation rate (cf. Gillespie 1994). Consequently, the transition rate from state sA to state sà is μ, and from to sà is μ/3, because a site sà in state has three possible changes (mutational opportunities), only one of which is A. So far, this is equivalent to the Jukes-Cantor model (Jukes and Cantor 1969). In addition, given our assumption of equal mutation rates, the probability of observing a polymorphism at a synonymous site is independent of the fixed nucleotide, that is the state sA or sÃ. Assuming a fixed sample size of k alleles, we denote the probability that a site is segregating in our sample by S (short for Sk).

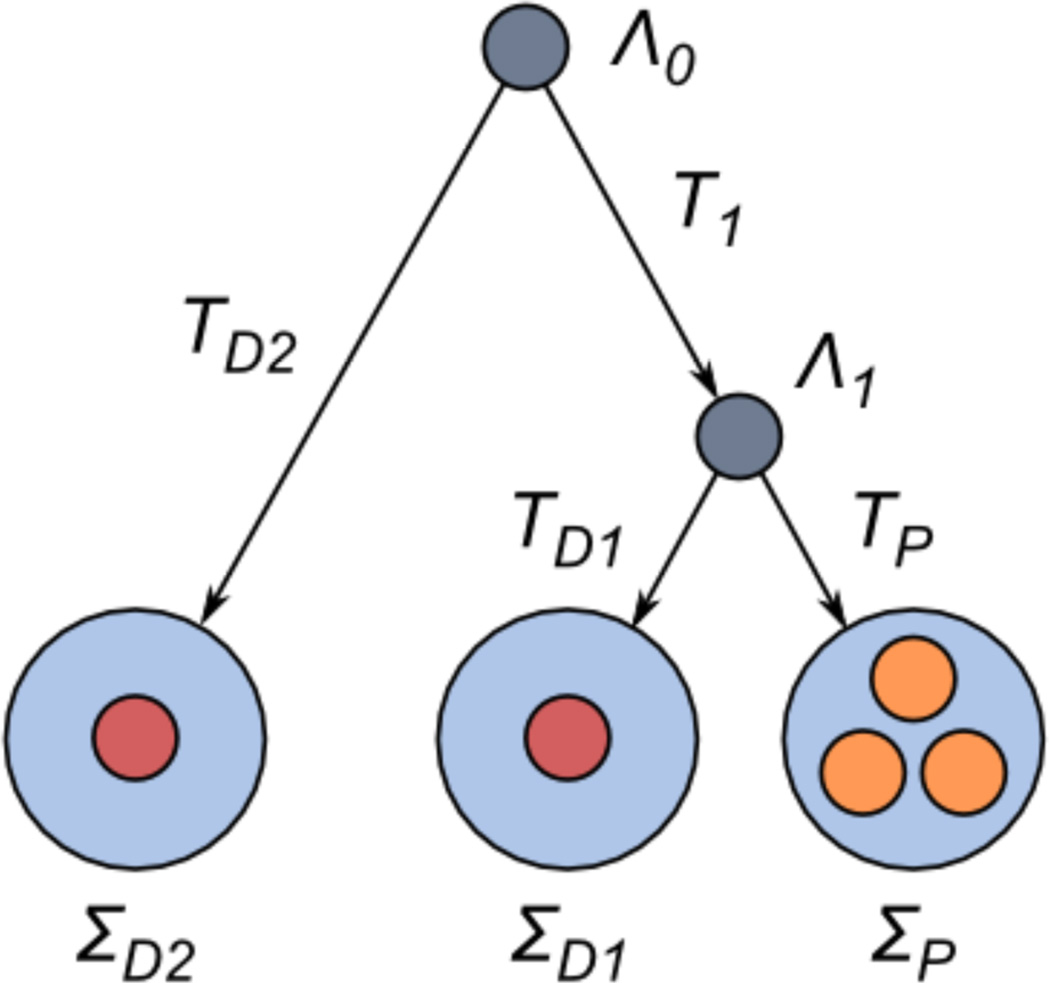

Figure 1.

Transition rate diagrams. (A) Synonymous site; (B) Non-synonymous site. Double circles indicate states that could be polymorphic.

Next, we consider non-synonymous sites (see Figure 1B). Unconstrained non-synonymous sites are similar to synonymous sites in both their rate μ of neutral fixations and their probability S of segregating in our sample (Figure 1B, states uA and uÃ). On the other hand, all the mutations at constrained sites are deleterious and therefore they are not subject to neutral fixations and have a negligible probability of segregating in our sample. In addition, non-synonymous sites can be affected by changes in the environment that impose new selective pressures, turning sites from unconstrained to constrained and vice versa.

We distinguish between two kinds of events in this class: adaptations and relaxations. An adaptation (in the context of this model) is a process by which a change in the environment favors a particular amino acid – and thus a specific nucleotide at a non-synonymous site – and this nucleotide eventually fixes at the site (see Figure 2). After an adaptation, a site is always constrained, because once the beneficial allele has fixed, all the possible mutations at the site are deleterious.

Figure 2.

Types of adaptations in the model. Each row depicts a process at a site, represented by a quadruplet; the fixed nucleotide is marked with a frame, light shaded nucleotides are neutral or equally beneficial, and dark shaded nucleotides are deleterious. (A) An unconstrained adaptation with a fixation event: A change in the environment affects an unconstrained site where A is fixed, and now favors only C. The intermediate state is short-lived, as eventually, through mutation and selection, C fixes at the site, which is now constrained. (B) An unconstrained adaptation without a fixation event: By chance, C is the fixed nucleotide before the environmental change. The change again favors C, turning the site into a constrained one, such that selection will keep C fixed. (C) A constrained adaptation: A change in the environment affects a constrained site with A fixed, favoring only C. Again, through mutation and selection, C eventually fixes at the site.

There are two kinds of adaptations in the model, which differ in the selective state that preceded them. If the site was originally unconstrained, we term the event an unconstrained adaptation (Figure 2A and B). In a quarter of these cases, the newly favored nucleotide is expected to be the one already fixed, since the change in the environment is independent of the arbitrarily fixed nucleotide in an unconstrained site (Figure 2B). Here, although the type of the site changes from unconstrained to constrained, there is no substitution of the fixed nucleotide, so that an adaptation does not always result in a substitution. We denote the fraction of unconstrained adaptations out of all the adaptations by g, a parameter that we consider later in more detail. If the total rate of adaptations is ν, and unconstrained sites are subject to unconstrained adaptations with rate νu, this means that gν = fνu, so . Similarly, if the site was originally constrained, we term the event a constrained adaptation. In this case, both the preferred and the fixed nucleotide change, but the site remains constrained (Figure 2C). If constrained sites are subject to constrained adaptations with rate νc, then a similar argument yields .

We further assume that the proportion of unconstrained and constrained non-synonymous sites is at steady state (see Fay et al. 2002; Smith and Eyre-Walker 2002). Thus, given that unconstrained adaptations turn unconstrained sites into constrained ones, an opposite process must exist to maintain the balance: a relaxation is when a change in the environment loosens the constraints on a particular amino acid, turning a constrained non-synonymous site into an unconstrained one. This process does not involve a mutation and thus, it does not result in a change of the fixed nucleotide. If we denote by ξ the rate of relaxation at constrained sites, then the total rate of relaxation is (1 − f)ξ, and in order to maintain f at steady state, it must equal the total rate of unconstrained adaptations, giving .

The complete transition rate diagram of a non-synonymous site is presented in Figure 1B. We note that this process is not time-reversible, as can be seen from the fact that the transition rate from uA to cà is , but the opposite transition is null (since relaxations do not involve mutation). The described transition rates for synonymous and non-synonymous sites can be written in two matrices, the generator matrices of the respective Markov processes (Taylor and Karlin 1994):

and

where the ijth element, i ≠ j, is the transition rate from state i to state j, and the order of the states is (sA,sÃ) and (uA,uÃ,cA,cÃ), respectively. Now pi→j(t) = Pr(X(t) = j| X(0) = i), that is, the transition probability from state i to state j after a time t is given by the ijth element of the matrix exponential etM, where M is the relevant generator matrix.

The main difference between this model and common stochastic models of sequence evolution now becomes clear: here, the transition probabilities allow one not only to calculate the probability of substitution, but also the probability that a site is segregating in a sample. The latter is the probability the site is unconstrained multiplied by the probability that an unconstrained site is segregating, that is S.

Because we are interested in the implications of relaxing the assumption of stationary selective pressures at a site, we make several simplifying assumptions about other factors, most of which are widespread. First, we assume that the species trees are known and ignore possible differences between gene trees and species trees or shared ancestral polymorphism; this assumption is shared by most methods (e.g., McDonald and Kreitman 1991; Yang 1997) and would hold, for example, if the species split is relatively old and there has been no gene flow since the split. Second, we neglect linkage disequilibrium between sites and assume that the probability of observing a polymorphism at neutral sites (with a constant sample size) is uniform along the genome, i.e., we do not model variation in mutation rates and the possible effects of selection at linked sites along the genome (e.g., Charlesworth et al. 1993; Maynard Smith and Haigh 1974). We further assume that the sample sizes used to measure polymorphism are not extremely large or that low frequency alleles are discarded, as is customary in applications of the McDonald-Kreitman based methods (which assume that strongly deleterious alleles can be ignored). Fourth, we assume that nucleotides in coding regions can be classified into synonymous and non-synonymous, ignoring the fact that some positions can have both synonymous and non-synonymous mutations (Li and Graur 1990). Having made these simplifying assumptions, we explore the importance of the two that are likely to have the strongest effects on patterns of polymorphism and divergence under our model.

2.2. Relating model parameters to polymorphism and divergence

Given the parameters of the model (f, S, μ, ν and g) that define the transition probabilities, and assuming that these parameters are stationary throughout a phylogeny, we can use Felsenstein's pruning algorithm (Felsenstein 1981) to calculate the probabilities of observing divergence between nodes of a phylogenetic tree at a non-synonymous site, dn, or of polymorphism at a non-synonymous site at a given node, pn, as well as the corresponding probabilities at synonymous sites. We can also calculate the probability bn that a non-synonymous site is divergent between two species and polymorphic in a third. Sites that satisfy this condition belong to the “intersection set”, and the number of such sites will prove instrumental for inferring the source of beneficial substitutions (see section 3.2). These calculations are illustrated for a given phylogenetic configuration in the Appendix.

2.3. Incorporating the effects of weakly deleterious mutations

Our model ignores the potential effects of weak purifying selection. Yet weak purifying selection is known to bias standard McDonald-Kreitman based inference, and studies in Drosophila indicate that they comprise a substantial portion of segregating non-synonymous mutations (Andolfatto et al. 2011; Keightley and Eyre-Walker 2007). It is therefore natural to consider how these effects could be incorporated into the model. To this end, we make the sensible assumption that the main effect of weakly deleterious mutations would be to add to observed polymorphisms but not to divergence. In terms of the model, this can be incorporated by assuming that constrained sites could also contribute to polymorphism; we denote the probability that a constrained site segregates in our sample by Sc and denote the ratio of this probability to the probability that a neutral site segregates by 0 ≤ δ ≤ 1.

While introducing weakly deleterious mutations does not change the transition probabilities for non-synonymous sites, it does affect what we expect to observe. Because constrained non-synonymous sites can also segregate now, the expected ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous polymorphisms becomes

By the same token, the probability of observing a non-synonymous site that is both segregating in one species and divergent between two others will include a contribution not only from sites that are unconstrained in the first species but also from sites that are constrained. We denote by the probability that an unconstrained site in the first species is divergent between the other two; is defined similarly for a site that is constrained. In these terms, the probability of observing a non-synonymous site in the intersection set becomes

The other observed quantities remain unchanged.

3. Results

3.1. The fraction of beneficial substitutions α

With the expressions for polymorphism and divergence in hand, we can ask how conclusions about adaptive parameters would differ under the model we introduce compared to previous ones. We begin by considering the simpler model without weakly deleterious mutations (incorporating them in section 3.3). First, we examine how assuming our model would affect inferences about α, the proportion of amino acid substitutions driven by positive selection. Usually, α is derived from an extension of the McDonald-Kreitman approach (as described in the Introduction).

The expectation of this proportion α can also be expressed in terms of the parameters of our model, as the ratio of the rate of adaptive substitutions to the total rate of non-synonymous substitutions. The numerator is equal to (see Figure 1B) and the denominator is obtained by adding the contribution of neutral substitutions fμ, giving:

Unlike in previous approaches, here, α depends on both the rate of adaptation at non-synonymous sites, ν, and on the fraction of adaptations that are unconstrained, g. We therefore examine how estimates of ν/μ and α change when we vary g between 0 and 1 and hold constant other parameters and values of divergence dn and polymorphism pn (Figure 3). To choose plausible values for the parameters and observables, we use estimates from the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup (see caption and Supplementary Information for further detail). Then we generate the graphs by solving for the adaptive parameters for different values of g.

Figure 3.

Estimates of the rate of adaptation. (A) Estimates of the total rate of adaptive events ν given the parameter g (obtained using the function FindRoot in Mathematica 8). Note that the rate is presented as its proportion with respect to the (constant) neutral mutation rate μ; assuming the value μ =0.058 mutations per Myr in Drosophia (Haag-Liautard et al. 2007), the estimate of ν varies between 1.83·10−3 and 3.14·10−3 adaptations per Myr. The shaded regions denote the approximate 95% confidence interval (see section 3.6). (B) Estimates of α for a given value of g (we note that, at this scale, the confidence region is barely perceptible). For comparison, we also estimate α according to the method of Smith and Eyre-Walker (2002) using the same parameters, shown here as a red dashed line.

The estimated rate of adaptation ν strongly increases with g (Figure 3b): because a quarter of the unconstrained adaptations do not involve substitutions, as the fraction g increases, a greater rate ν is required to produce the observed levels of non-synonymous divergence. Because, by definition, α involves only substitutions, it is less sensitive to the value of g (Figure 3B). The rather minor change in α results from second order effects such as multiple hits. Interestingly, this suggests that as long as the divergence between the species considered is not too high, estimates of α based on our model should be similar to those based on previous methodologies. Using the Smith and Eyre-Walker’s (2002) approach yields a similar estimate of α to ours, conforming with this expectation (Figure 3B).

3.2. The fraction of unconstrained adaptations g

Next we consider the fraction of unconstrained adaptations. As illustrated in Figure 4A, g and ν are not identifiable from the counts of polymorphism and divergence used in the McDonald-Kreitman test and its existing extensions. Different pairs of g and ν lead to the same rate of non-synonymous divergence per site, whereas the rest of the counts – synonymous divergence and polymorphism, and non-synonymous polymorphism – are not affected by those parameters, and thus do not carry information about them.

Figure 4.

Non-synonymous divergence. (A) Simulated curves of equal non-synonymous divergence between D. simulans and D. yakuba, given values of g and ν (darker shades represent lower divergence values). The measured value is shown as a dashed orange line. (B) The same graph with superimposed curves of equal intersection set size (that is, non-synonymous sites that are divergent between the two species and polymorphic in their ancestor).

It turns out however that, under our model, g (and ν) can be estimated by adding a third count, consisting of those non-synonymous sites that are both divergent between two species and polymorphic in a third (see Figure 4B). Imagine for simplicity an unrealistic setting, in which we have divergence data between two species and polymorphism data from the common ancestor (topology 0 in Figure 5A). We further assume that these species are close enough that we can neglect multiple hits. To understand how the size of the intersection set informs us about g, we partition the possible events at a nonsynonymous site into four cases (see Figure 6). First, we consider sites that were unconstrained in the ancestor and remained unconstrained along the branches (Figure 6A). Being unconstrained, some of these sites were polymorphic in the ancestral sample (the orange ellipse); also, independently of whether they were polymorphic (and neglecting the fixation of alleles that segregated in the ancestor), some of these sites might have fixed along one of the branches, leading to divergence between the extant species (the red ellipse). The intersection of the two ellipses represents the sites that would display both divergence and polymorphism. In contrast, sites that were constrained in the ancestor and did not experience a selective change along the branches are expected to show neither divergence nor polymorphism (hence the empty frame in Figure 6B).

Figure 5.

Tree topologies. (A) Topology 0 shows a hypothetical data set, in which divergence is measured between two species and polymorphism is measured in their ancestral population. (B) Topologies 1 and Topology 2 (shown in C) represent more realistic data sets, in which divergence is measured between the species with red circles and polymorphism is measured in the one with orange circles.

Figure 6.

The intersection sets in four cases. See text for details.

Second, we consider the cases in which an adaptation occurred along one of the branches (green arrow in Figure 5A). In three quarters of the cases in originally unconstrained sites and all cases in originally constrained sites, this adaptation will imply the substitution of the fixed nucleotide in the left branch, causing divergence between the extant species (the big red ellipse in Figures 6C and D). However, only if the site was originally unconstrained could it have been polymorphic in the ancestor (hence the orange ellipse in Figure 8C and its absence in Figure 6D). Therefore, the difference between adaptations that occur at unconstrained or constrained sites is manifest in the size of the intersection set. For example, if all adaptations occur at constrained sites (g = 0), the cases represented by Figure 6C are missing and the only sites with both divergence and polymorphism are the (constantly) unconstrained ones. In contrast, if there exist adaptations that originate from unconstrained sites (g = 0), these cases would contribute to both counts and enlarge the intersection set. Thus, a higher g induces a larger intersection set.

Figure 8. The effects of weakly deleterious mutations on estimates of adaptive parameters.

We plotted the estimates of model parameters as a function of δ, the ratio of the probability of observing a segregating site at unconstrained versus a constrained site (obtained using the function FindRoot in Mathematica 8). The graphs focus on the range of δ where the model would fit the data. The blue curves correspond to topology 1 and the red to topology 2. (A) f as a function of δ. (B) ν/μ as a function of δ. (C) g as a function of δ. (D) α as a function of δ.

Inspecting the form of the probability that a non-synonymous site is both divergent and polymorphic in the ancestor, bn, confirms this intuitive explanation. Indeed, this probability increases with g for various values of the adaptation rate ν (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Probability that a site is polymorphic or divergent. The probability that a non-synonymous site is both divergent and polymorphic (bn, left) and the probability that it is divergent (dn, right), for a given value of g and for ν = 0.03μ, 0.04μ, 0.05μ, 0.06μ (darker to lighter lines, respectively); the rest of the parameters are taken from our estimates for the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup (see Supplementary Information). (A) For the hypothetical case (corresponding to topology 0 in Figure 5) in which divergence is measured between D. simulans and D. yakuba and polymorphism measured in their ancestral population (with parameters for the ancestral population taken from D. simulans). (B) Using divergence between D. yakuba and D. melanogaster and polymorphism in D. simulans (topology 1 in Figure 5) (C) Using divergence between D. yakuba and D. erecta, polymorphism in D. simulans (topology 2 in Figure 5).

Since in practice, we do not have polymorphism data from the ancestral population, we would need to use extant species in order to infer g from real data. If we use the same species to calculate polymorphism and divergence, however, the intersection set might be incorrectly estimated because of errors in the identification of ancestral alleles at polymorphic sites. Estimates of g could be especially sensitive to such ancestral misidentifications, because the intersection set is very small to begin with and can be substantially inflated by this error. Specifically, since polymorphic sites that are not divergent are much more frequent at short phylogenetic distances, such misidentifications would substantially increase the intersection count (see for example Table S3). A commonly used solution to the problem of ancestral misidentification is to estimate its effects based on a population genetic model (e.g., Williamson et al. 2005). The problem is that such a model would necessarily rely on assumptions about processes we know little about in reality, such as the population’s demographic history, and the size of the intersection set and hence the estimates of g could be extremely sensitive to these assumptions. One way around this, which differs from existing implementations of McDonald-Kreitman methods, is to measure polymorphism in a third, separate species. There are two options for choosing the species in which polymorphism is measured, corresponding to different tree topologies: the first, where it is closer to one of the species between which divergence is measured (topology 1 in Figure 5B), and the second, where it is equally distant from both (topology 2 in Figure 5C). We therefore consider these two topologies in what follows.

3.3. Inference under the model with weakly deleterious mutations

To assess how incorporating weakly deleterious mutations could affect conclusions about adaptive parameters, we examine how estimates of ν/μ, g, and α change when we vary the contribution of constrained sites to polymorphism, parameterized by δ (Figure 8). As we have done in our analysis thus far, other parameters and the observed divergence dn, polymorphism pn, and intersection bn are held constant and their values are chosen based on estimates from the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup (Table S3). To generate the graphs, we solved for the adaptive parameters for different values of δ.

The presence of deleterious mutations affects estimates of f, v/μ, and α in our model in ways that reflect the same biases that they introduce in McDonald-Krietman based methodologies (cf. Sella et al. 2009). Notably, estimates of f decreases with δ because, given a fixed number of segregating non-synonymous sites, a greater contribution of constrained sites implies a smaller fraction of unconstrained sites. At lower values of v/μ and g, the contribution of neutral substitutions at non-synonymous sites decreases with the fraction of unconstrained sites f, implying that a greater rate of adaptation v/μ is required to explain the observed non-synonymous divergence (Figure 8B, lower branches). The same reasoning explains why α increases with δ (Figure 8D, lower branches).

Interestingly, the analysis shows that solutions for the adaptive parameters exist only for a limited range of δ; when 0.0274 ≤ δ ≤ 0.0388 for topology 1 and 0.0292 ≤ δ ≤ 0.0393 for topology 2. The lower bound is explained by considering the expected probability of observing an intersection, i.e., sites that exhibits both polymorphism and divergence. All else being equal, this probability in minimized when g = 0, i.e., when there are no unconstrained adaptations, and thus the probability of intersection is primarily generated by neutral substitutions at unconstrained sites. As δ increases, the expected number of these neutral substitutions decreases with f, until it eventually equals the observed value. This explains why there is a minimal value of δ where a solution exists and g = 0. A further increase in δ is compensated for by a higher number of unconstrained adaptations, leading to the increase in g (Figure 8C, lower branches). Explaining the relationships at low values of f and high values of v/μ and g is less intuitive and requires considering the countervailing effects of turning unconstrained sites into constrained ones on the lineage on which we measure polymorphism (the effect is therefore more pronounced in topology 2). Most importantly, these considerations explain why estimates of g could be extremely sensitive to the effects of weakly deleterious mutations (Figure 8C).

3.4. Sensitivity to assumptions about the way in which sites are constrained

Another important assumption of our model is the dichotomy that we make between completely unconstrained and completely constrained sites. In reality, some changes (that is, mutational opportunities) at a site may be neutral while others are deleterious. In order to evaluate the sensitivity of our model to this assumption, we consider two extreme cases under the over-simplified scenario in which polymorphism is measured in the ancestral population (Figure 5: topology 0).

First, we allow only completely unconstrained and completely constrained non-synonymous sites, with the following parameters: a fraction of unconstrained sites, f, a neutral mutation rate, μ, a total rate of adaptive events, ν, and g = 1, meaning that all the adaptations originate in unconstrained sites. After one step forward in time, a substitution in a non-synonymous site is expected with probability , because only three quarters of adaptations would cause a substitution. In turn, the probability of observing a polymorphism at a non-synonymous site in the ancestral population is Sf. Since sites that were constrained in the ancestral population will not change their nucleotide (because g = 1), the probability of observing both a substitution and polymorphism in the ancestral population is simply .

Next we assume that non-synonymous sites either have one neutral mutational opportunity and two deleterious ones or are completely constrained. To maintain the same fraction of neutral mutational opportunities as in the first case, we require 3f of the sites to have one neutral mutational opportunity and the rest to be constrained; the other parameters remain as above. Now, after one step forward in time, a substitution in a non-synonymous site is expected with probability , because in this configuration the rate of neutral fixations is only (since here only one out of the three possible mutations at a partially constrained site is neutral). The same reasoning implies that the probability of observing a polymorphism in the ancestral population is . Again, since g = 1, completely constrained sites are not expected to change their nucleotide, and therefore the probability of observing both a substitution and a polymorphism in the ancestral population is .

These two cases have the same neutral mutation rate, total adaptation rate and g, and differ only in the way that neutral mutational opportunities are distributed among sites. Accordingly, the expected divergence (ignoring multiple hits) and polymorphism levels are also equal. However, we see that the probability that a site is in the intersection set is expected to be three times larger in the first case. Therefore, if we used our model to estimate the parameters in each of the two cases, we would expect the estimate of g to be lower in the second one, even though the underlying parameter is the same for both. In turn, Figure 7 reveals that a three-fold difference in the size of the intersection set can change the estimate of g drastically. This example illustrates that estimates of g could be highly sensitive to distribution of neutral non-synonymous mutational opportunities among sites (see Bierne and Eyre-Walker 2003).

This problem can be addressed by extending our model to incorporate additional types of sites – with one or two possible neutral changes, for example – thereby allowing the distribution of neutral mutational opportunities to be inferred rather than assumed. This extension would entail adding states and parameters to the model, which would require a more general definition of g (see Figure 9). In turn, to allow for the estimation of additional parameters, one might consider using further information in the data: for example, incorporating a count of the number of sites in the intersection set that also share the same two alleles in polymorphism and divergence. Intuitively, the relative size of this subset of the intersection set will be larger when there are fewer neutral mutational opportunities concentrated at any given site, which suggests that adding such counts would provide information about the way in which neutral non-synonymous mutational opportunities are distributed.

Figure 9.

Generalized definition of g. We define for each site the set F of (equally) beneficial nucleotides; mutations within F are neutral and mutations outside F are deleterious, such that the fixed nucleotide is always expected to be in F. Selective changes (adaptations and relaxations) are precisely those that alter this set. For example, in our model, we allow only #F = 1 or 4 (where #F denotes the number of nucleotides in the set): #F=1 for constrained sites, where there is only one preferred nucleotide, and #F=4 for unconstrained sites, where all nucleotides are equally favorable and thus all mutations are neutral. Here, unconstrained adaptations reduce the set F, constrained adaptations change its contents, and relaxations expand it. A general definition can be made in a similar fashion: let F0 and F1 denote the favorable set of a site before and after a selective event, respectively, so (A) if F0 ⊂ F1 (i.e., the set was expanded), the event is a relaxation; (B) if F0 ⊃ F1 (the set was reduced), the event is an unconstrained adaptation; and otherwise, (C) this event is a constrained adaptation. Now, g is defined like before as the fraction of unconstrained adaptations (B) out of all adaptive events (B and C). This definition accords with the notion of novelties and modifications (see Discussion).

3.5. Using the model as a basis for inference

Our substitution model, either in its basic form or its extensions incorporating the effects of weakly deleterious mutations or more elaborate models of constrained sites, can also be used as a basis for inference. If we assume linkage equilibrium, the probability of observing a specific triplet of counts (Pn*, Dn*, Bn) of polymorphic (but not divergent), divergent (but not polymorphic), and intersection sites follows a multinomial distribution with parameters Ln (the total number of nonsynonymous sites), pn*, dn*, bn, and 1 − pn* − dn* − bn. In turn, for the basic model probabilities pn*, dn*, and bn can be calculated from the parameters of the model Π, i.e. f, S, μ, ν, g and branch lengths, using a pruning algorithm (Appendix), and these probabilities can then be further modified to incorporate weak selection (section 2.3).

Hence the log-likelihood of Π given a specific count is

where C is the logarithm of the multinomial coefficient . More generally, the same principles can be applied to calculate the probabilities and likelihood function associated with any configuration of divergence and polymorphism data from multiple species. Adaptive parameters can be inferred by maximizing the likelihood function.

Such inference is limited by the number of sites that are polymorphic in one species and divergent between two others. For example, using current polymorphism data in D. simulans and divergence between D. simulans and D. yakuba, only about one in a thousand sites fall in this category (Table S3). Since the average gene in eukaryotes is only a few thousands base pairs long (Lynch 2007), obtaining reasonable intersection set counts requires the use of relatively large data sets. To evaluate whether genome-wide data would in principle allow for such an inference, we pick different combinations of the adaptive parameters v/μ and g, and calculate the region in which their inferred values would fall in 95% of cases (see Supplementary Information for details). The sample sizes (~3·106 non-synonymous sites) and other parameters were chosen based on data from Drosophila (Table S3). The results (Figure 10) suggest that it should be feasible to obtain reasonable estimates of g with genome-wide polymorphism data sets, several of which have been published in recent years (e.g., Begun et al. 2007; Durbin et al. 2010; Liti et al. 2009) and many more of which are forthcoming.

Figure 10.

Performance of inference of adaptive parameters with genome-wide data. We picked 24 combinations of adaptive parameters, ν/μ = 0.03, 0.04, 0.05, 0.06 and g = 0, 0.2, 0.4,…, 1, and calculated the region in which their inferred values would fall in 95% of cases (see details in Supplementary Information). The sample sizes (~3·106 non-synonymous sites) and other parameters were chosen based on the Drosophila data from chromosome 2 (see Table 4). The resulting regions are shown in terms of ν/μ and g (A and C) and of α and g (B and D) for topologies 1 and 2, correspondingly.

3.6 Application to data from the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup

To demonstrate how inference based on our model would work, we estimate α for coding regions of the second chromosome of D. simulans and D. yakuba. This application is illustrative, since we do so for the simplest version of our model, which lacks the extensions that may be important in reaching a robust biological conclusion.

Estimating α

We rely on genome-wide polymorphism data from six inbred lines of D. simulans (Begun et al. 2007) and their alignments to homologous sequences from D. yakuba (Clark et al. 2007) (approximately 1.3 million codons were sampled; see Supplementary Information for details). To make our estimates comparable to previous studies, we begin by using only counts of polymorphic and divergent sites but do not use the counts of the intersection. We then infer ν and α while holding g constant, repeating this estimation for the range of g values between 0 and 1 (see Figure 5A). Doing so allows us to investigate the sensitivity of the estimates of ν and α with respect to g. We find that the estimate of α ranges between 37% and 44% (the functional relationship is shown in Figure 3B), depending on the assumed value of g. This result is consistent with the estimation of α by the usual approach (Smith and Eyre-Walker 2002), as well as with previous estimates of α (e.g., 45% (Smith and Eyre-Walker 2002), 25%±20% (Bierne and Eyre-Walker 2004) and 40%±10% (Welch 2006)). Moreover, as discussed in section 3.1, the estimates of α in our model are reasonably robust with respect to the value of g.

Estimating g

We estimate g using the two phylogenetic configurations considered above. Namely, in addition to the genome-wide polymorphism data available in D. simulans (Begun et al. 2007), we use divergence data between D. melanogaster and D. yakuba (topology 1), and between D. erecta and D. yakuba (topology 2) (Clark et al. 2007) (Figure 11). We estimate that g is 0 in both topologies, and that ν/μ is 2.79·10−2 and 3.81·10−2 in topologies 1 and 2, respectively. If valid, these estimates would imply that all adaptations occurred at constrained sites. A closer examination, however, reveals that the observed intersection set is smaller than we would expect from the model. Specifically, we found 1,290 and 882 sites in the intersection set of chromosome 2, in topologies 1 and 2 respectively (see Table S3), while the expected minimum counts according to the model are about twice as many, 2,437 and 1,779 sites in topologies 1 and 2 respectively. These values are significantly different (p < 10−100 in both cases, using a binomial distribution), indicating a poor fit of the model.

Figure 11.

Phylogenetic tree of the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup. See Methods for details.

Our analysis of the model suggests two plausible explanations. The first is a contribution of weakly deleterious mutations to the observed non-synonymous polymorphism. In section 3.3, we solved for the adaptive parameters given such a contribution. When a solution exists, it can easily be shown to be the maximum-likelihood estimate, and given the size of sample for the Drosophila data, the confidence intervals should be very small. Thus, if the maximum likelihood estimate predicts a much larger intersection set than observed, as is the case here for δ=0, it implies that a solution does not exist. In contrast, a solution exists for greater values of δ, indicating that a model with a sufficiently large contribution from weakly deleterious mutations would fit the data well. Whether such a large contribution is realistic for D. simulans, however, awaits future investigation. Using forthcoming polymorphism datasets with larger sample sizes will allow δ to be estimated by fitting models for the distribution of selection coefficients to the site frequency spectrum. Such approaches have been applied in the context of McDonald-Kreitman based inference (Boyko et al. 2008; Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2007; Fay et al. 2001), and could incorporated into future inference based on our model.

A second explanation relates to the dichotomy we assumed between constrained and unconstrained sites. Under this assumption, we found that the observed intersection set is approximately twofold smaller than expected given the estimated parameters. Under the extreme alternative, where each constrained site has only one deleterious mutation, the expected size of the intersection set could be threefold smaller (see section 3.4). Taken together, this suggests that an intermediate model could fit the data well. Even if a more realistic model of constraint would not account entirely for observed size of the intersection set, it is likely to contribute to a better fit.

In summary, to use the kind of substitution model that we outlined as a basis for inference will require some extensions to the model – notably a generalized model for constrained sites, and perhaps also standard extensions such as introducing variation in selection and mutation rates (reflective of base composition) among sites. In terms of the data, it would be helpful to have genome-wide divergence data between two species (or more) and polymorphism data in a third (or more), with a large enough sample size to precisely quantify the contribution of weakly selected mutations.

4. Discussion

In this study, we make a first step towards a model of protein evolution that accounts for changes in the selective pressures on non-synonymous sites due to shifts in the environment and the fixation of beneficial alleles. The model that we study is probably the simplest stochastic model of sequence evolution that also incorporates information about polymorphism. A nice feature is that it exploits aspects of the data that are informative about parameters of adaptation but were not used by previous models (namely sites that are polymorphic in one species and divergent between two other species). Although it may be too simple to apply to data without extensions, the model helps to highlight two important considerations salient to models that seek to combine polymorphism and divergence: the selective effect of adaptive mutations before they became beneficial and the way in which neutral non-synonymous mutational opportunities are distributed among sites.

Indeed, in models that use the standard approach to inferring α, it is implicitly assumed that g = 1 (e.g., Bierne and Eyre-Walker 2004; Welch 2006). To show that, we write the usual expression for α in terms of divergence and polymorphism probabilities per site: , where a denotes the probability of observing an adaptive substitution in a non-synonymous site. Since it is assumed that the probability of observing a polymorphism is equal at synonymous and unconstrained non-synonymous sites, the ratio is an estimate of f, the fraction of non-synonymous sites that are unconstrained, so we can write . Now, we consider two genes with the same value of α as a parameter. The probability of synonymous divergence per site, ds, depends only on the divergence time and mutation rate, assumed to be constant, so we can assume it is the same for the two genes. The equality α1 = α2 (where the index is for the gene) then gives ; after substituting dn by a + fds we obtain . This result implies that (viewed as a parameter) the chance of observing an adaptive substitution at a non-synonymous site, a, is proportional to the fraction of neutral nonsynonymous sites, f, which is equivalent to assuming that g = 1. This derivation therefore shows that in order to interpret the results obtained by existing approaches to estimate α, we need a reliable estimate of g.

The parameter g has also a bearing on the central question of how many beneficial substitutions originate from standing genetic variation, as opposed to newly arising mutations (Barrett and Schluter 2008; Hermisson and Pennings 2005; Orr and Betancourt 2001). Indeed, unconstrained adaptations are more likely to emerge from standing genetic variation than constrained adaptations, because if the newly favored allele was originally neutral, it may have already been present in substantial frequency within the population before the change in the environment. Therefore, a higher value of g increases the expected number of adaptations originating from standing genetic variation. This also has implications for the signatures of selective sweeps (Maynard Smith and Haigh 1974): adaptive alleles that take over the population starting from higher initial frequencies tend to be on more than one genetic background, and thus might show weak, or none, of the signatures of classic selective sweeps (Hermisson and Pennings 2005; Innan and Kim 2004; Przeworski et al. 2005).

Finally, g is a measure of interest in its own right, providing insight into the question of whether most adaptations are novelties or modifications. If we interpret novelty as the origination of a new function, then unconstrained adaptations – in which the identity of an amino acid that was previously unimportant for function becomes important – can be seen as the molecular version of novelties. (Although an amino acid may also be important to function by, for example, being a spacer between parts of the protein.) Similarly, constrained adaptations might be viewed as modifications of existing functions, because they change the preferred identity of an amino acid that was already important for function, and thus constrained. A higher value of g implies, therefore, a higher proportion of novelties among adaptations.

Conclusion

Forthcoming genome-wide polymorphism and divergence data open new opportunities in the study of the genetic basis of adaptation. Taking advantage of these opportunities requires developing and basing our inferences on more realistic models of molecular evolution. Central to this undertaking is to move beyond “shift models” (cf. Gillespie 1994), the simplicity of which comes at the expense of strong and unrealistic assumptions about selection (i.e., that the distribution of the selective effects of mutations at a site remains stationary through evolutionary time). Here, we take a first step in this direction to learn about an unexplored facet of adaptations, whether they originate from previously constrained or unconstrained sites, and find that the number of sites that are polymorphic in one species and divergent between others, a previously unused feature of the data, carries information about it. Further development of `non-shift’ models promises to reveal other unexplored and yet fundamental characteristics of adaptation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dmitri Petrov and members of his lab for helpful discussions and their hospitality when this work was started; Mike Macpherson and Shmuel Sattath for help with data analysis; Yosef Rinott and Danny Wilson for helpful discussions; Peter Andolfatto for comments on the manuscript; Molly Przeworski for many helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript; and Uzi Motro for allowing us to work in his wadi.

Appendix

Using the pruning algorithm to derive the probabilities of observing polymorphic, divergent and intersection sites

As an illustration, we present a detailed derivation of the probabilities for a polymorphic, divergent and intersection non-synonymous sites in the configuration depicted in Figure A1 (topology 1 in Figure 5). The derivation for the synonymous case, as well as for other phylogenetic configurations, is similar.

Figure A1.

Nodes and branches in a topology 1 tree.

First, we assign names to the nodes of the tree, corresponding to species and ancestral populations: ΣP is the species where polymorphism is measured, divergence is measured between ΣD1 and ΣD2, the first being closer to ΣP; Λ1 is the most recent common ancestor of ΣP and ΣD1, and Λ0 is the most recent common ancestor of all three species (see Figure 10). The times from Λ0 to Λ1 and ΣD2 are T1 and TD2, respectively, and the times from Λ1 to ΣD1 and ΣP are TD1 and TP, respectively. Second, we denote the state at a non-synonymous site by X = 1, …,4 corresponding to uA, u Ã, cA, c Ã. The main assumption is that evolution in every pair of branches that diverge from the same node is conditionally independent, given the state at their common root.

Assume, without loss of generality, that in Λ1 the fixed nucleotide in the site was A. Now, the probability that the site is polymorphic in ΣP, given that it was unconstrained in Λ1, is the conditional probability of being unconstrained in ΣP, multiplied by S, which is the probability that an unconstrained site segregates in our sample: Pr(poly | X(Λ1) = 1) = S Σj=1,2 p1→j(TP). Similarly, the probability that the site is polymorphic, given that it was constrained in Λ1, is Pr(poly | X(Λ1) = 3) = S Σj=1,2 p3→j(TP).

The probability of having the same nucleotide fixed in two different nodes is the sum of the probability of having à fixed in both, and one third of the probability of having fixed in both (as we assume equal mutation and substitution rates among nucleotides).

Define

so the probability that the site is divergent between the two species, given that the state in Λ1 was i ∈ {1, 3} (that is, A), is

The first argument of Δ is the probability of having A fixed in ΣD1 given that the state in Λ1 was i, which is simply Pr(X(ΣD1) ∈ {1, 3} | X(Λ1) = i) = Σk=1,3 pi→k(TD1). The second argument is more difficult to compute because the process is not reversible – here we must consider the possible states in Λ0 – so:

where is the stationary distribution vector of the non-synonymous process (hence Pr(X = l) = λl) (Taylor and Karlin 1994), and the equality at * is justified due to the conditional independence of the states in Λ1 and ΣD2, given the state in Λ0.

The probability of a polymorphism in ΣP and the probability of divergence between ΣD1 and ΣD2 are conditionally independent, given the state in Λ1. Therefore, the total probability of both divergence and polymorphism is

| (A1) |

The probabilities of only divergence (that is, without polymorphism; denoted dn*) and only polymorphism (pn*) are computed in the same way:

| (A2) |

| (A3) |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andolfatto P, Wong KM, Bachtrog D. Effective population size and the efficacy of selection on the X chromosomes of two closely related Drosophila species. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:114–128. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett RD, Schluter D. Adaptation from standing genetic variation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2008;23:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazykin GA, Kondrashov AS. Detecting past positive selection through ongoing negative selection. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:1006–1013. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begun DJ, Holloway AK, Stevens K, Hillier LW, Poh YP, et al. Population genomics: whole-genome analysis of polymorphism and divergence in Drosophila simulans. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierne N, Eyre-Walker A. The problem of counting sites in the estimation of the synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates: implications for the correlation between the synonymous substitution rate and codon usage bias. Genetics. 2003;165:1587–1597. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.3.1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierne N, Eyre-Walker A. The genomic rate of adaptive amino acid substitution in Drosophila. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1350–1360. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyko AR, Williamson SH, Indap AR, Degenhardt JD, Hernandez RD, et al. Assessing the evolutionary impact of amino acid mutations in the human genome. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante CD, Nielsen R, Sawyer SA, Olsen KM, Purugganan MD, et al. The cost of inbreeding in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2002;416:531–534. doi: 10.1038/416531a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B, Morgan MT, Charlesworth D. The effect of deleterious mutations on neutral molecular variation. Genetics. 1993;134:1289–1303. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.4.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AG, Eisen MB, Smith DR, Bergman CM, Oliver B, et al. Evolution of genes and genomes on the Drosophila phylogeny. Nature. 2007;450:203–218. doi: 10.1038/nature06341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Altshuler DL, Auton A, Brooks LD, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker A, Keightley PD. The distribution of fitness effects of new mutations. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:610–618. doi: 10.1038/nrg2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker A, Keightley PD. Estimating the rate of adaptive molecular evolution in the presence of slightly deleterious mutations and population size change. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:2097–2108. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay JC, Wyckoff GJ, Wu CI. Positive and negative selection on the human genome. Genetics. 2001;158:1227–1234. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.3.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay JC, Wyckoff GJ, Wu CI. Testing the neutral theory of molecular evolution with genomic data from Drosophila. Nature. 2002;415:1024–1026. doi: 10.1038/4151024a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum likelihood approach. J Mol Evol. 1981;17:368–376. doi: 10.1007/BF01734359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JH. The causes of molecular evolution. Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JH. Substitution processes in molecular evolution. III. Deleterious alleles. Genetics. 1994;138:943–952. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.3.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman N, Yang Z. A codon-based model of nucleotide substitution for protein-coding DNA sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 1994;11:725–736. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag-Liautard C, Dorris M, Maside X, Macaskill S, Halligan DL, et al. Direct estimation of per nucleotide and genomic deleterious mutation rates in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;445:82–85. doi: 10.1038/nature05388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermisson J, Pennings PS. Soft sweeps: molecular population genetics of adaptation from standing genetic variation. Genetics. 2005;169:2335–2352. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.036947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Sanchez E, Durrett R, Bustamante CD. Population genetics of polymorphism and divergence under fluctuating selection. Genetics. 2008;178:325–337. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.073361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innan H, Kim Y. Pattern of polymorphism after strong artificial selection in a domestication event. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10667–10672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401720101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukes TH, Cantor CR. Evolution of protein molecules. In: Munro HN, editor. Mammalian protein metabolism. New York: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 21–123. [Google Scholar]

- Keightley PD, Eyre-Walker A. Joint inference of the distribution of fitness effects of deleterious mutations and population demography based on nucleotide polymorphism frequencies. Genetics. 2007;177:2251–2261. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.080663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WH, Graur D. Fundamentals of Molecular Evolution. Sinauer Associates; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Liti G, Carter DM, Moses AM, Warringer J, Parts L, et al. Population genomics of domestic and wild yeasts. Nature. 2009;458:337–341. doi: 10.1038/nature07743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M. The Origins of Genome Architecture. Sinaeuer Associates; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard Smith JM, Haigh J. The hitch-hiking effect of a favourable gene. Genet Res. 1974;23:23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JH, Kreitman M. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature. 1991;351:652–654. doi: 10.1038/351652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muse SV, Gaut BS. A likelihood approach for comparing synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitution rates, with application to the chloroplast genome. Mol Biol Evol. 1994;11:715–724. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R, Yang Z. Estimating the distribution of selection coefficients from phylogenetic data with applications to mitochondrial and viral DNA. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:1231–1239. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr HA, Betancourt AJ. Haldane's sieve and adaptation from the standing genetic variation. Genetics. 2001;157:875–884. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.2.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennings PS, Hermisson J. Soft sweeps III: the signature of positive selection from recurrent mutation. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przeworski M, Coop G, Wall JD. The signature of positive selection on standing genetic variation. Evolution Int J Org Evolution. 2005;59:2312–2323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer SA, Hartl DL. Population genetics of polymorphism and divergence. Genetics. 1992;132:1161–1176. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.4.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sella G, Petrov DA, Przeworski M, Andolfatto P. Pervasive natural selection in the Drosophila genome? PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith NG, Eyre-Walker A. Adaptive protein evolution in Drosophila. Nature. 2002;415:1022–1024. doi: 10.1038/4151022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahata N, Ishii K, Matsuda H. Effect of temporal fluctuation of selection coefficient on gene frequency in a population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:4541–4545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.11.4541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor HM, Karlin S. An introduction to stochastic modeling. Boston: Academic Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Welch JJ. Estimating the genomewide rate of adaptive protein evolution in Drosophila. Genetics. 2006;173:821–837. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.056911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan S, Lio P, Goldman N. Molecular phylogenetics: state-of-the-art methods for looking into the past. Trends Genet. 2001;17:262–272. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson SH, Hernandez R, Fledel-Alon A, Zhu L, Nielsen R, et al. Simultaneous inference of selection and population growth from patterns of variation in the human genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7882–7887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502300102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DJ, Hernandez RD, Andolfatto P, Przeworski M. A population genetics-phylogenetics approach to inferring natural selection in coding sequences. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13:555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Nielsen R, Goldman N, Pedersen AM. Codon-substitution models for heterogeneous selection pressure at amino acid sites. Genetics. 2000;155:431–449. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.